Abstract

Objectives

Pain management is critical for nurses; therefore, knowledge assessment is also critical. The Knowledge and Attitudes Survey Regarding Pain (KASRP), designed for testing pain management knowledge among nurses, finds widespread use internationally; yet, key validity evidence according to American Psychological Association standards is missing. Therefore, this study aimed to translate and test the psychometric traits of KASRP based on an item response theory model.

Methods

Cronbach’s α was included to assess internal consistency, and the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was included to assess the total score normal distribution goodness of fit. KASRP was tested using the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) test for sphericity to examine its suitability for factor analysis and exploratory factor analysis to examine construct evidence. The Kruskal–Wallis H test was used to assess discriminant evidence. The correlation between KASRP and the Brockopp–Warden Pain Knowledge Questionnaire (BWPKQ) was included as a measure of convergent validity evidence, and correlation with self-assessed knowledge was tested as a divergent validity measure.

Results

The questionnaire was translated using back-forth and parallel translation. The KMO test for sphericity was 0.49 for all items and 0.53 for the adjusted scale without items 30, 33, and 36, with factor analysis explaining 70.42% of the variation suggesting unacceptable construct validity evidence. Cronbach’s α was 0.75, suggesting acceptable reliability evidence; the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test revealed an insignificant skewness of −0.195 and a kurtosis of 0.001, while the Kruskal–Wallis H test revealed a significance of p < 0.001. The correlation between KASRP and the BWPKQ was 0.69 (p = 0.0001), suggesting acceptable convergent validity evidence. A correlation between KASRP and self-assessed knowledge of −0.59 was also found, which suggests acceptable divergent validity evidence.

Conclusions

The translated KASRP passed six out of seven tests based on the given sample.

1 Introduction

According to previous studies, post-operative complications in surgery [1], prolonged physical recovery after orthopedic surgery [2], poor treatment outcomes in patients with shoulder pain [3], poor sleep in primary care patients [4], disturbed appetite and weight loss [5], cognitive impairment [6], anxiety and stress in surgical patients [7], depression [7,8], treatment dropout in chronic pain patients [9], suicide risk [10], and mortality [11,12] are associated with pain.

As reported by Ung et al., pain is the main reason people seek medical attention [13]. Pain treatment is considered a major challenge for healthcare professionals [14,15], and almost 19% of the European adult population have suffered an episode of low-to-medium-intensity pain where the management was not administered correctly [16]. Adequate pain management is related to the medical staff’s level of knowledge regarding pain management [17,18]. It has been suggested that inadequate pain management could be a consequence of the low educational level of pain across health disciplines [19]. Therefore, nurses’ knowledge regarding effective pain management is highly relevant.

Existing studies report a lack of knowledge about pain management among nurses [20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27]. A systematic review and meta-study based on the Knowledge and Attitudes Survey Regarding Pain (KASRP) found that the level of knowledge is lower than 80% [13]. In a Danish survey of health professionals, 90% agreed “somewhat” or “highly” that there was a need for improved knowledge about pain and pain treatment in their department [28]. According to previous investigations, nurses tend to overestimate their knowledge about the topic and underestimate patient pain [29,30]. This is in accordance with research showing that respondents’ assessment of their knowledge is not in line with an objective measure of knowledge [31,32]. Hence, there is a need for assessment of registered nurse (RN) pain management knowledge.

The KASRP was chosen for validation because it was deemed the most promising scale based on existing evidence. The KASRP is derived from general international pain management standards in accordance with the American Pain Society, the World Health Organization, and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network Pain Guidelines [33]. It has 41 items, four of these based on cases, and is based on a varied pool of questions about the pharmacokinetics of analgesic agents, pain assessment, and pain management in general. It is designed for use among students, postgraduates, and experts, and a passing score of 80% has been suggested [34]. The KASRP questionnaire exists in Chinese, Colombian, Greek, Icelandic, Irish, Italian, Jordanian, Norwegian, Spanish, Swedish, and Turkish versions [34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43]. Developers Ferrell and McCaffery refer to KASRP’s ability to discriminate between levels of expertise and to test–retest reliability of >0.80 and CA > 0.70 [33]. Zuazua-Rico et al. reported CA of 0.78, Pearson’s r of 0.88, and test–retest score of 0.88. Bernardi et al. reported CA of 0.69 and test–retest of 0.97 [36]. Chia et al. did not identify significant differences in mean scores by years of working experience, area of discipline of work, educational background, job grades, and whether they attended a pain management course [38]. Tafas et al. found CA of 0.88 and test–retest reliability of 0.68 [40]. Tse and Ho found a significant increase in KASRP scores from 7.9 to 19.2 after an 8-week RN pain-management program [41]. Moceri and Drevdahl found no significant differences in mean total scores by age, educational level, years of nursing experience, or years of experience [24]. Tests of multidimensionality could not be identified for KASRP. According to American Psychological Association (APA) standards, a scale must be tested for multidimensionality as a key aspect of validity evidence. Translations must consider national pharmaceutical standards regarding preparation and dosage as well as national culture. According to APA standards, a scale should be tested locally on validity aspects and cannot be considered valid as is [44].

The purpose of this study was to translate and test the psychometric traits of KASRP based on an Item Response Theory (IRT) model to permit the usage of KASRP in a Danish setting. Within the paradigm of IRT, the aim is to explain the observed item scores by invoking an unobservable latent trait underneath these item scores [45]. By testing psychometric aspects, the KASRP would allow for future testing of this knowledge among RNs.

2 Methods

2.1 Translation

This study was completed with the approval of a hospital review board and by the guidelines set down by the Danish Data Protection Agency (Datatilsynet) under the following reference: CHR-2016-001, with I-Suite No. 05135. Permission to translate KASRP was obtained from its developer by email on September 13, 2023.

Translation of the KASRP (see Appendix S1) and the Brockopp–Warden Pain Knowledge Questionnaire (BWPKQ, see Appendix S2) included for convergent validity testing was based on the combination of techniques recommended by Brislin [46]. The original American English version was used as the benchmark and then translated into Danish based on three parallel translations that were compared: one by a Danish-English translation expert; one by Jens Ulrik Grevstad, MD, PhD, associate professor specialized in anesthetics; and one by Kirsten Erck, RN, head nurse. The meaning of each translation was discussed along with possible difficulties in understanding the items to form one single Danish translation. The preliminary Danish version was then translated back into American English by a fourth translator.

Regarding items 8, 38, and 39 of KASRP, the suggested dosage of morphine was adjusted to fit the recommendations in Denmark. Regarding items 5, 16, 18, 25, and 30, the names of preparations used in a US setting were changed to those of similar Danish preparations. Vicodin, referred to in items 16, 25, and 30, does not exist in the Danish medicine market, so it was substituted. Items concerning prejudices of the cultural background of a patient were transposed into similar cultural prejudices in Denmark. The item “How likely is it that patients who develop pain already have an alcohol and/or drug abuse problem?” (item 33 in the original version) was removed due to ambiguity.

2.2 Sample

The questionnaire was completed by 39 nursing students at the first and third years of study and 52 RNs working in intensive care and anesthetics using electronic forms.

RNs were contacted through an agreement with local management in three intensive care and anesthetics clinics. Classes were pointed out through the administrative office of a nurse education institution, and students were given an hour to take the test. No respondents expressed a need for this. RNs filled out their questionnaire one at a time, and each person was allowed to take whatever time they needed. Both RNs and students were told that the correct answers would be available after the test, as an incentive to achieve a higher response rate.

2.3 Data collection

The full questionnaire consisted of the adapted KASRP followed by a BWPKQ, a field for an email address to facilitate a background variable analysis, an item asking respondents to rate competence as “1: low”, “2: medium” or “3: high” on a discrete slider scale, and an open-ended item allowing for remarks about the questionnaire. The participants’ assessment of their knowledge levels was placed after KASRP and BWPKQ to make sure it would not affect these tests. The participant’s assessment was expected to be more in line with actual knowledge than if they had not filled out a test beforehand.

The BWPKQ is a 24-item questionnaire with true or false responses designed to assess nurses’ knowledge of pain control and biases toward patient groups regarding the management of their pain. In that sense, the questionnaire resembles the KASRP. Themes include post-operative pain, patient indicators related to pain, preventive care, analgesics, opioids, addiction, administration of preparations, and patients’ statements of pain. Most themes overlap with the KASRP themes. The BWPKQ was previously tested with a test–retest value of 0.86 [47], internal consistency of 0.66–0.73, and an intraclass correlation coefficient of 0.50–0.58 [48]. The authors of this article were not able to identify previous tests based on factor analysis of the BWPKQ.

With the use of an online questionnaire form, items were presented one at a time to reduce inter-item influence, also known as the halo effect [49].

2.4 Procedure and analysis

Assessment of Cronbach’s α allowed for comparison with previous research. The main purposes of the analytic procedure were to see whether a latent construct could be identified and to see whether the test would be able to discriminate between a group of participants expected to have a low level of knowledge (students) and a group expected to have a higher level of knowledge about pain management (RNs in intensive care and anesthetics). These are tests of construct validity and discriminant validity evidence. We identified a single prior study [46] that completed discriminant validity tests, which made it relevant to include this test for comparison since discriminant validity is considered a key aspect of validity evidence. Multidimensionality was tested with factor analysis. Because no prior analysis of the factor construct exists, the test was based on exploratory factor analysis instead of confirmatory factor analysis. Although internal consistency was tested in previous studies, it has not been covered in any previous Danish studies.

Correlation between KASRP and the BWPKQ as a similar construct was included to test convergent validity aspects.

The item that tested participants’ assessments of their knowledge levels after being tested with KASRP was included as a test of divergent validity evidence and to see whether knowledge would be over- or under-estimated because previous research shows overestimation [31,32].

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS Statistics 25 (IBM, New York, USA). Efforts were made to adhere to APA standards, including recommendations regarding translation, validity, and reliability measures [44]. Internal consistency was tested with Cronbach’s α. Normality distribution and discriminant validity were measured using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov and Kruskal–Wallis H tests, respectively. Factor analysis feasibility was assessed using the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) test for sphericity, while construct validity evidence was tested using exploratory factor analysis. Evidence of convergent validity was tested by correlating KASRP and BWPKQ. The association between KASRP and self-assessed knowledge was tested through a correlation.

3 Results

A total of 91 respondents, including 39 nursing students and 52 RNs, completed the questionnaire. Two incomplete questionnaires were left out of the analysis. Participants did not comment on the questionnaire via open-ended questions. The RNs and students had an expected difference in mean age, but previous research did not find a link between age and KASRP scores [46]. A difference in gender distribution was identified (Table 1). No sources of bias affecting the sample data were identified.

Participant statistics on age, gender, employment time, and KASRP score

| Count (n) | Age; IQR | Gender | Years of employment time | KASRP mean score (0–40 points) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RNs | 52 | 48 years; IQR: 22 | 43 females/9 males | 8.45 years (0–22 years) | 27.04; IQR: 6 |

| Nursing students | 37 | 28 years; IQR: 1 | 35 females/2 males | 0 years | 20.69; IQR: 4 |

| Total | 89 | 40 years; IQR: 31 | 78 females/11 males | 24.32; IQR: 7 |

IQR = Interquartile range.

The highest number of correct answers per item was 88 out of 89, and the lowest number was 9. Between the easiest and hardest questions, difficulty increased smoothly, as illustrated in Figure 1. The highest number of correct answers per participant was 33 out of 40, while the lowest number was 10. On average, the number of correct answers amounted to 60.7% for each participant. Seven respondents achieved a score above the suggested 80% passing score. The lowest half of the sample (n = 45) had a mean score of 20.67 with an interquartile range (IQR) of 3, whereas the highest half had a mean score of 27.89 with an IQR of 5.

Students and RN percentage of correct answers for each item in KASRP. RN: registered nurses.

When arranged by the number of correct answers, an even distribution was found for items with both the lowest number and the highest number of correct answers, which means there is an even distribution of difficulty (Figure 1). The KASRP questionnaire is available in Appendix S1. RNs had an average score of 27.04 (73.08% correct), whereas nursing students had an average score of 20.69 (55.92% correct). The distribution showed differences between nursing students and RNs.

3.1 Reliability evidence

Initial pairwise comparisons by correlation matrix revealed an overall positive manifold; however, there was a low correlation for items 30, 33, and 36 (Table 2), suggesting that these should be excluded from the scale. Reliability was tested for internal consistency with Cronbach’s α. A Cronbach’s α value of 0.75 was found.

Minimum and maximum correlation values for items 30, 33, and 36

| Min | Max | |

|---|---|---|

| i30 | −0.20(i23) | 0.17(i16) |

| i33 | −0.17(i16) | 0.14(i27) |

| i36 | −0.21(i34) | 0.16(i22) |

3.1.1 Construct validity evidence

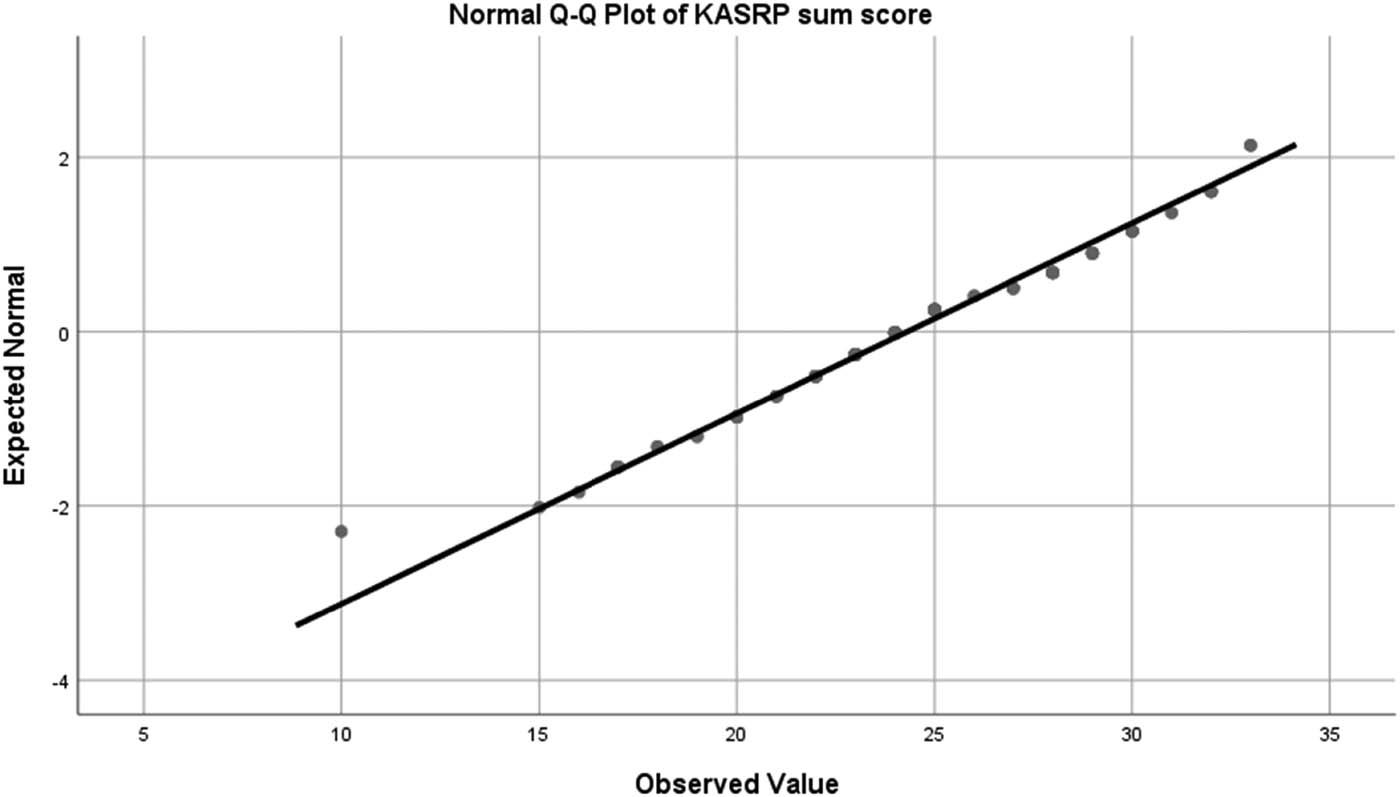

The KMO test for sphericity was 0.49 for all items and 0.53 without items 30, 33, and 36 (the critical value was 0.6). Therefore, the following tests were reported without items 30, 33, and 36. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test revealed a skewness of −0.2 and a kurtosis of −0.001 with a significance of 0.07. The values of skewness and kurtosis were, therefore well within the critical values of −2 and 2, and the significance was well within the critical value of 0.05. The normality is illustrated in the Q–Q plot in Figure 2.

Q–Q plot of the KASRP Sum Score. KASRP: knowledge and attitudes survey regarding pain; Q: quantiles.

KASRP was tested using exploratory oblique rotation factor analysis because a theoretical model for confirmatory factor analysis could not be identified. The determinant was of 0.000017, which is above the critical value of 0.00001. No correlations between 0.80 and 1 were found. The low determinant is unsurprising, considering the low value for sphericity. With a reduced model, KMO had a value of 0.53, which is below the critical level of 0.60 under the significance level of p < 0.001, meaning that the adapted model was significant. The reduced model explains 70.42% of the variation, which is considered moderate and is based on 14 factors at an eigenvalue cutoff = 1. There is no clear, significant cut level on the scree plot, as illustrated in Figure 3, and therefore, an exclusion of factors is not suggested. Previous research covering factor analysis was not identified. The factors were, therefore, not based on a theoretical model, and items contributing to each factor were not within the same topic. A principal component analysis was completed, and item correlation for each component had no clear overarching theme (see Appendix S3). For instance, the first component had correlations above 0.4 with items 2, 3, 6, 9, 11, 15, 17, 20, 24, 26, 27, 28, 31, and 40, which cover varying topics. Overall, the analysis shows acceptable construct validity evidence.

Scree plot of KASRP eigenvalues and components.

3.2 Discriminant validity evidence

Scores for each subgroup revealed a higher score for RNs (27.04) than for nursing students (20.69), p < 0.0001. This supports the view that KASRP can discriminate between low and high levels of knowledge. The difference in distribution was tested using Kruskal–Wallis H with a significance of p < 0.001, which is well below the critical level of 0.05, suggesting acceptable discriminant validity evidence. The difference in distribution is illustrated in Figure 4.

Independent samples’ Kruskal–Wallis H test of KASRP RN vs students. KASRP: Knowledge and Attitudes Survey Regarding Pain, RN: registered nurses.

3.3 Convergent validity evidence

A high positive Spearman correlation was found between KASRP and BWPKQ sum scores of 0.69 (p < 0.0001), which supports convergent validity evidence. BWPKQ had a lower IQR than KASRP (4 versus 7).

3.4 Divergent validity evidence

The mean score for self-assessment was 2.75 (IQR 1). There was a negative Spearman correlation (−0.63) between self-assessed knowledge and the KASRP sum score. A negative correlation indicates that participants with high confidence in their knowledge about pain management had low test scores on the KASRP test. The negative correlation suggests acceptable divergent validity evidence.

4 Discussion

The KASRP was translated successfully into Danish, and the psychometric properties of KASRP showed ambiguous test values based on acceptable internal consistency evidence, unacceptable sphericity, acceptable normal distribution, acceptable construct validity evidence, acceptable discriminant validity evidence, acceptable convergent validity evidence, and acceptable divergent validity evidence. It is possible that other changes would have been suggested if the questionnaire translation had been validated by a larger board of experts. As mentioned earlier, respondents were given the opportunity to share their thoughts with an open-ended question at the end of the questionnaire, but no comments were made. The item “How likely is it that patients who develop pain already have an alcohol and/or drug abuse problem?” (item 33 in the original version) was removed. It was considered ambiguous because the likelihood of alcohol and drug abuse changes over time and across cultures.

Cronbach’s α has been reported in the range of 0.69 to 0.88, intra-class of 0.88, and test–retest of 0.68 to 0.97 [33,36,37, and 40]. A Cronbach’s α of 0.75 was identified in line with previous research. The low skewness and kurtosis values support the conclusion that the sample was fit for psychometric testing. Test–retest was not included as a reliability aspect. It has a value when the test value is expected to be the same over time. With cognitive tests, the test value is not expected to remain the same over time because people learn, not least when they are exposed to questions about the topic and talk to colleagues about the topic. Hence, examination of test–retest would be considered of limited value in the current study.

The present study tests key validity evidence aspects, including construct validity as a key psychometric trait. Latent traits have not been tested previously with methods such as factor analysis, principal component analysis, or Rasch models. Based on the KMO sphericity test before the factor analysis and the factor analysis itself, an underlying factor structure is not supported. The factor structure is also not theoretically supported, and items within each factor are not placed within clearly defined themes, which calls for further item development. With the highly significant Kruskal–Wallis test, the KASRP can discriminate between respondents who are expected to have low levels of knowledge and respondents with higher expected levels of knowledge. The positive correlation with the BWPKQ supports the hypothesis that KASRP can be used to measure pain management knowledge. A high correlation was not expected because no evidence considering BWPKQ construct validity aspects could be identified. Therefore, there is less certainty about what the BWPKQ measures. When the correlation between KASRP and self-assessment is negative, it confirms divergent validity evidence. The correlation may have been affected by the fact that self-assessment was tested after the KASRP test. The sample was based on convenience sampling. It is small in relation to recommendations of sample size between 100 and 1,000 [50] and should, therefore, be considered a limitation.

Discriminant validity has been tested on nursing students and critical care, palliative care, and oncology nurses and had the highest score among palliative care nurses [36]. In line with existing research, KASRP discriminated well between nursing students and RNs. In the Icelandic, Norwegian, and Swedish studies, the mean levels of correct answers, which were lower than those found in this study, were 60.7%, even though 80% was suggested as a cutoff level. This may indicate that boosting knowledge or adjusting the cutoff score should be considered.

Samples in previous tests of KASRP psychometric properties were based on emergency and intensive care nurses [25,34,38], general medicine and nursing students [37], internal medicine, pediatrics, outpatient clinics [38], surgery [38,43], primary medical centers [35], cancer care [40,42], tertiary-level hospitals [39], nursing homes [41], and teaching hospitals [43]. Across nationalities, the samples are too diverse to reach comparative conclusions about KASRP scores. Nationality, locality, years of experience, field of practice, differences between studies, and other factors may influence the differences in scores.

Adjusting the cutoff may set a more realistic standard. Setting a cutoff based on statistical tests is suggested. Since the KASRP is designed for assessment in several levels of expertise cutoffs for beginner, intermediate, and advanced levels may also be useful. Because of differences in samples between existing research studies, there is still limited knowledge regarding the representative level of knowledge among nurses within and across countries. This is a challenge regarding suggestions for cutoff. Prior research suggests setting the cutoff at a lower level because of the low mean scores observed. However, more generalizable information about the level of knowledge is needed to determine a meaningful cutoff.

Existing research [29,30] shows that some RNs tend to underestimate patient pain; this underestimation is sometimes described as desensitization [51]. Relevant to this phenomenon identified in previous research, it is interesting that both under- and overestimations are found with the KASRP. This study found a mean score of 0.55 (SD 0.5) in i37 and 0.75 (SD 0.44) in i39, although 8 was the correct answer in both cases. In other words, in this sample, patient pain was both under- and overrated, depending on the case.

None of the participants reported any knowledge of KASRP before participation. Because no prior Danish translations exist, the participants were unlikely to have encountered the KASRP questions beforehand.

Since no previous studies have tested construct validity, no previous studies have suggested deleting or changing items. New topics and variations of questions based on the themes from the items that we suggest deleting (30, 33, and 36) could be included. Evidence could be based on a Delphi study among experts and the latest research, with a reassessment of face validity evidence of the KASRP scale. The topics for excluded items are cancer pain treatment, the time until the peak effect of morphine, and opioid-induced respiratory depression. These aspects are not covered in other items. Those who develop new versions should consider if these topics could be included with other items, for instance, by asking easier questions about the topics. New tests of construct validity should follow any item adaptations. Those who wish to translate this test into other languages should consider guidelines, including considerations regarding preparations, dosage, and culture. For item 32 about cultural considerations, participants might have been able to see through the purpose of testing for cultural bias. Therefore, even if a person answered the question correctly, they might still have been culturally biased in their assessment of a patient.

Adding new items in accordance with the latest research might be considered. Although good test values were found for KASRP overall, future adaptations may improve the test values.

5 Conclusion

The KASRP questionnaire was translated successfully with adaptations related to preparations and culture, and one item was initially excluded. The psychometric properties of KASRP without the four items (about the likelihood of developing pain due to alcohol or drug abuse and items 30, 33, and 36) that were ultimately excluded showed ambiguous test values. This conclusion was reached based on the following test aspects: acceptable internal consistency, unacceptable sphericity, acceptable normal distribution, acceptable construct validity evidence, acceptable discriminant validity evidence, acceptable convergent validity evidence, and acceptable divergent validity evidence.

Acknowledgements

Jens Ulrik Grevstad, MD, PhD, associate professor specialized in anesthetics, and Kirsten Erck, RN, head nurse.

-

Research ethics: Research involving human subjects complied with all relevant national regulations and institutional policies and is in accordance with the tenets of the Helsinki Declaration (as amended in 2013) and has been approved by The Danish Data Protection Agency (Datatilsynet) under the reference CHR-2016-001, with I-Suite No.: 05135.

-

Informed consent: Informed consent has been obtained from all individuals included in this study.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and have approved its submission. Jacob Brauner: inception and design of the study, drafting the protocol, data acquisition, data analyses, data interpretation, and drafting of the manuscript. Sanne Lund Clement: inception and design of the study and drafting of the manuscript.

-

Competing interests: The authors state there was no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: The authors state no funding was involved.

-

Data availability: The raw data can be obtained on request from the corresponding author.

Appendix S1: English back-translation of the Danish translation of the Knowledge and Attitudes Survey Regarding Pain

Vital signs are always reliable indicators of the intensity of a patient’s pain. [true/false]

Because their nervous system is underdeveloped, children under 2 years of age have decreased pain sensitivity and limited memory of painful experiences. [true/false]

Patients who can be distracted from pain usually do not have severe pain. [true/false]

Patients may sleep in spite of severe pain. [true/false]

Ibuprofen and other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents are NOT effective analgesics for painful bone metastases. [true/false] (Ibuprofen changed from aspirin)

Respiratory depression rarely occurs in patients who have been receiving stable dosages of opioids over a period of months. [true/false]

Combining analgesics that work by different mechanisms (e.g., combining an NSAID with an opioid) may result in better pain control with fewer side effects than using a single analgesic agent. [true/false]

The usual duration of analgesia with pain relief after 2.5–5 mg intravenous morphine is 4–5 h. [true/false] (dosage changed)

Opioids should not be used in patients with a history of substance abuse. [true/false]

Elderly patients cannot tolerate opioids for pain relief. [true/false]

Patients should be encouraged to endure as much pain as possible before using an opioid. [true/false]

Children less than 11 years old cannot reliably report pain, so clinicians should rely solely on the parent’s assessment of the child’s pain intensity. [true/false] (change regarding age)

Patients’ spiritual beliefs may lead them to think pain and suffering are necessary. [true/false]

After an initial dosage of opioid analgesic is given, subsequent dosages should be adjusted in accordance with the individual patient’s response. [true/false]

Giving patients sterile water by injection (placebo) is a useful test to determine if the pain is real. [true/false]

Tramadol 50 mg peroral is approximately equal to 10 mg morphine. [true/false] (changed from ‘Vicodin (hydrocodone 5 mg + acetaminophen 300 mg) and 5–10 mg morphine)’)

If the source of the patient’s pain is unknown, opioids should not be used during the pain evaluation period, as this could mask the ability to correctly diagnose the cause of pain. [true/false]

Anticonvulsant drugs such as gabapentin produce optimal pain relief after a single dosage. [true/false] (changed, Neurontin removed)

Benzodiazepines are not effective pain relievers and are rarely recommended as part of an analgesic regiment. [true/false]

Narcotic/opioid addiction is defined as a chronic neurobiologic disease, characterized by behaviors that include one or more of the following: impaired control over drug use, compulsive use, continued use despite harm, and craving. [true/false]

The term “equianalgesia” means approximately equal dosages of analgesia and is used when referring to the dosages of various analgesics that provide approximately the same amount of pain relief. [true/false]

Sedation assessment is recommended during opioid pain management because excessive sedation precedes opioid-induced respiratory depression. [true/false]

The recommended route of administration of opioid analgesics for patients with persistent cancer-related pain is: [intravenous, intramuscular, subcutaneous, oral, rectal].

The recommended route administration of opioid analgesics for patients with brief, severe pain of sudden onset such as trauma or post-operative pain is: [intravenous, intramuscular, subcutaneous, oral, rectal].

Which of the following analgesics/pain relief medications is considered the drug of choice for the treatment of prolonged moderate to severe pain for cancer patients? [codeine, morphine, pethidine, tramadol] (meperidine changed to pethidine, text underlined)

A 30 mg dosage of oral morphine is approximately equivalent to: [morphine 5 mg IV, morphine 10 mg IV, morphine 30 mg IV, morphine 60 mg IV].

Analgesics for post-operative pain should initially be given: [around the clock on a fixed schedule, only when the patient asks for the medication, only when the nurse determines that the patient has moderate or great discomfort].

A patient with persistent cancer pain has been receiving daily opioid analgesics for 2 months. Yesterday, the patient was receiving morphine 200 mg/h intravenously. Today, he has been receiving 250 mg/h intravenously. The likelihood of the patient developing clinically significant respiratory depression in the absence of new comorbidity is: [less than 1, 1–10, 11–20 and 21–40%, higher than 40%].

The most likely reason a patient with pain would request increased dosages of pain medication is: [a: the patient is experiencing increased pain; b. the patient is experiencing increased anxiety or depression; c. the patient is requesting more staff attention; d. the patient’s requests are related to addiction].

Which of the following is useful for the treatment of cancer pain? [ibuprofen, morphine, gabapentin, all of the above] (hydromorphone (Dilaudid) changed to morphine)

The most accurate judgment of the intensity of the patient’s pain is: [a. the treating physician, b. the patient’s primary nurse, c. the patient, d. the pharmacist, e. the patient’s spouse or family].

Which of the following describes the best approach for cultural considerations in caring for patients in pain? [a. there are no longer cultural influences in Denmark due to the diversity of the population; b. cultural influences can be determined by an individual’s ethnicity (e.g., Greenland indigenous people are stoic, people from the Middle East are expressive, etc.; c. patients should be individually assessed to determine cultural influences; d. cultural influences can be determined by an individual’s socioeconomic status (e.g., blue-collar workers report more pain than white collar workers]. (answer b changed from Asians are stoic, Italians are expressive)

The time to peak effect for morphine given via IV is: [15 and 30 min, 1 and 2 h].

The time to peak effect for morphine given orally is: [5 and 30 min, 1–2 and 3 h].

Following the abrupt discontinuation of an opioid, physical dependence is manifested by the following:

[a: sweating, yawning, diarrhea, and agitation; b: impaired control over drug use, compulsive use, and craving; c: the need for higher dosages to achieve the same effect; d: a and b]

Which statement is true regarding opioid-induced respiratory depression? [a. more common several nights after surgery due to accumulation of opioids], b. obstructive sleep apnea is an important risk factor, c. occurs more frequently in those already on higher dosages of opioids before surgery, d. can be easily assessed using intermittent pulse oximetry]

Patient A: Anders is 25 years old, and this is his first day following abdominal surgery. As you enter his room, he smiles at you and continues talking and joking with his visitor. Your assessment reveals the following information: BP = 120/80; HR = 80; R = 18; on a scale of 0 to 10 (0 = no pain/discomfort, 10 = worst pain/discomfort), he rates his pain as 8.

On the patient’s record, you must mark his pain on the scale below. Circle the number that represents your assessment of Anders’ pain: [0 no pain/discomfort, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 worst pain/discomfort].

Your assessment as per above is made 2 h after he received morphine 5 mg IV. Half-hourly pain ratings following the injection ranged from 6 to 8, and he had no clinically significant respiratory depression, sedation, or other untoward side effects. He has identified 2/10 as an acceptable level of pain relief. His physician’s order for analgesia is “morphine IV 2.5–10 mg pn.” Check the action you will take at this time: [1. administer no morphine at this time, 2. administer morphine 2.5 mg, 3. administer morphine 5 mg, 4. administer morphine 10 mg] (dosage changed).

Patient B: Robert is 25 years old, and this is his first day following abdominal surgery. As you enter his room, he is lying quietly and grimaces as he turns in bed. Your assessment reveals the following information: BP = 120/80; p = 80; RF = 18; on a scale of 0 to 10 (0 = no pain/discomfort, 10 = worst pain/discomfort), he rates his pain as 8.

On the patient’s record, you must mark his pain on the scale below. Circle the number that represents your assessment of Robert’s pain: [0 no pain/discomfort, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 worst pain/discomfort].

Your assessment as per above is made 2 h after he received morphine 5 mg IV. Half-hourly pain ratings following the injection ranged from 6 to 8, and he had no clinically significant respiratory depression, sedation, or other untoward side effects. He has identified 2/10 as an acceptable level of pain relief. His physician’s order for analgesia is “morphine IV 2.5–10 mg pn.” Check the action you will take at this time: [1. administer no morphine at this time, 2. administer morphine 2.5 mg, 3. administer morphine 5 mg, 4. administer morphine 10 mg] (dosage changed).

Appendix S2: English back-translation of the Danish translation of BWPKQ

A painful state is unhealthy and often dangerous.

Post-operative pain cannot be relieved in most cases.

Pain is associated with shallow breathing and cough suppression.

Sleeplessness and fatigue are linked with post-operative pain.

An elderly patient’s perception of pain is generally precise.

Assessment of pain should include the patient’s response to a visual analog scale or some other objective measure.

Among confused patients, pain assessment has a low value.

A patient using patient-controlled analgesia is likely to have better pain control.

Pain can be more easily prevented than controlled once it is established.

A patient receiving intraoperative nerve blocks is likely to ask for pain medication earlier than if they had received general anesthesia.

Opioid analgesics are the cornerstone of postoperative pain management.

Opioid addiction is extremely low.

There is a wide interindividual variance in the response to opioid analgesics.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) augment opioid analgesia.

If pain medication is administered every 4th hour, you should guide a patient with a pain breakthrough to wait until the next planned intake before taking pain relief medication.

NSAIDs, such as ibuprofen, control moderate to severe pain.

Administering opioids based on patient height and weight is more precise than dosing based on patient-reported pain.

Unless a patient is cognitively impaired, the usual approach to pain relief should be used.

The use of a placebo can prove that a patient is pretending to be in pain.

Respiration depression is a rare complication with opioids.

If patients receiving opioids experience abstinence, they have an addiction.

The assessment of pain should be conducted upon patient arrival, after any occurrence that could cause pain, after each reporting of or signs of pain, and every 4th hour.

Reevaluation of pain should be conducted within 60 min after administration of pain relief medicine.

Appendix S3: Principal component analysis

| Component matrix | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item | Component | |||||||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | |

| 1 | 0.247 | 0.094 | 0.353 | 0.464 | 0.059 | 0.149 | 0.116 | 0.331 | 0.068 | 0.069 | 0.020 | 0.312 | 0.043 | 0.003 |

| 2 | 0.513 | 0.211 | 0.197 | 0.287 | 0.062 | 0.083 | 0.180 | 0.357 | 0.061 | 0.207 | 0.088 | 0.124 | 0.110 | 0.055 |

| 3 | 0.406 | 0.004 | 0.016 | 0.009 | 0.017 | 0.625 | 0.111 | 0.130 | 0.147 | 0.350 | 0.064 | 0.055 | 0.095 | 0.067 |

| 4 | 0.377 | 0.214 | 0.009 | 0.268 | 0.063 | 0.491 | 0.160 | 0.030 | 0.028 | 0.196 | 0.255 | 0.129 | 0.159 | 0.035 |

| 5 | 0.276 | 0.011 | 0.096 | 0.423 | 0.008 | 0.153 | 0.019 | 0.066 | 0.360 | 0.289 | 0.319 | 0.039 | 0.093 | 0.101 |

| 6 | 0.458 | 0.369 | 0.114 | 0.343 | 0.166 | 0.097 | 0.012 | 0.181 | 0.104 | 0.051 | 0.012 | 0.168 | 0.137 | 0.119 |

| 7 | 0.324 | 0.153 | 0.281 | 0.499 | 0.187 | 0.193 | 0.233 | 0.125 | 0.110 | 0.055 | 0.148 | 0.030 | 0.009 | 0.207 |

| 8 | 0.193 | 0.587 | 0.324 | 0.054 | 0.076 | 0.188 | 0.137 | 0.068 | 0.188 | 0.062 | 0.072 | 0.091 | 0.162 | 0.161 |

| 9 | 0.641 | 0.036 | 0.236 | 0.151 | 0.066 | 0.058 | 0.204 | 0.089 | 0.008 | 0.096 | 0.179 | 0.127 | 0.117 | 0.214 |

| 10 | 0.217 | 0.046 | 0.435 | 0.386 | 0.251 | 0.151 | 0.078 | 0.163 | 0.105 | 0.362 | 0.046 | 0.053 | 0.005 | 0.022 |

| 11 | 0.579 | 0.261 | 0.327 | 0.185 | 0.098 | 0.083 | 0.094 | 0.011 | 0.022 | 0.051 | 0.037 | 0.319 | 0.095 | 0.247 |

| 12 | 0.037 | 0.121 | 0.053 | 0.068 | 0.134 | 0.286 | 0.352 | 0.142 | 0.202 | 0.133 | 0.386 | 0.237 | 0.126 | 0.375 |

| 13 | 0.052 | 0.616 | 0.046 | 0.086 | 0.255 | 0.129 | 0.137 | 0.302 | 0.057 | 0.261 | 0.127 | 0.217 | 0.006 | 0.256 |

| 14 | 0.060 | 0.225 | 0.192 | 0.275 | 0.436 | 0.215 | 0.076 | 0.516 | 0.151 | 0.065 | 0.190 | 0.050 | 0.030 | 0.064 |

| 15 | 0.472 | 0.296 | 0.161 | 0.266 | 0.331 | 0.143 | 0.274 | 0.039 | 0.014 | 0.009 | 0.193 | 0.110 | 0.047 | 0.061 |

| 16 | 0.156 | 0.090 | 0.142 | 0.366 | 0.012 | 0.103 | 0.265 | 0.119 | 0.507 | 0.147 | 0.286 | 0.250 | 0.213 | 0.105 |

| 17 | 0.471 | 0.212 | 0.441 | 0.105 | 0.028 | 0.092 | 0.101 | 0.020 | 0.035 | 0.059 | 0.179 | 0.257 | 0.119 | 0.091 |

| 18 | 0.261 | 0.238 | 0.175 | 0.073 | 0.275 | 0.255 | 0.051 | 0.163 | 0.128 | 0.421 | 0.300 | 0.100 | 0.150 | 0.073 |

| 19 | 0.069 | 0.316 | 0.068 | 0.133 | 0.034 | 0.170 | 0.495 | 0.290 | 0.135 | 0.112 | 0.415 | 0.002 | 0.191 | 0.040 |

| 20 | 0.437 | 0.363 | 0.244 | 0.178 | 0.222 | 0.097 | 0.175 | 0.124 | 0.027 | 0.008 | 0.106 | 0.156 | 0.297 | 0.365 |

| 21 | 0.334 | 0.006 | 0.331 | 0.274 | 0.209 | 0.400 | 0.181 | 0.254 | 0.239 | 0.191 | 0.118 | 0.017 | 0.116 | 0.173 |

| 22 | 0.332 | 0.083 | 0.112 | 0.066 | 0.309 | 0.103 | 0.080 | 0.190 | 0.127 | 0.215 | 0.278 | 0.010 | 0.422 | 0.399 |

| 23 | 0.150 | 0.265 | 0.038 | 0.013 | 0.405 | 0.267 | 0.158 | 0.166 | 0.133 | 0.314 | 0.090 | 0.322 | 0.213 | 0.162 |

| 24 | 0.433 | 0.057 | 0.374 | 0.128 | 0.290 | 0.153 | 0.288 | 0.310 | 0.167 | 0.007 | 0.097 | 0.001 | 0.058 | 0.238 |

| 25 | 0.123 | 0.245 | 0.018 | 0.148 | 0.078 | 0.121 | 0.648 | 0.224 | 0.026 | 0.357 | 0.183 | 0.075 | 0.050 | 0.051 |

| 26 | 0.491 | 0.404 | 0.035 | 0.052 | 0.193 | 0.253 | 0.056 | 0.047 | 0.124 | 0.011 | 0.105 | 0.089 | 0.072 | 0.017 |

| 27 | 0.428 | 0.225 | 0.076 | 0.012 | 0.148 | 0.234 | 0.118 | 0.214 | 0.214 | 0.217 | 0.184 | 0.337 | 0.140 | 0.199 |

| 28 | 0.592 | 0.093 | 0.411 | 0.184 | 0.181 | 0.009 | 0.233 | 0.091 | 0.068 | 0.093 | 0.100 | 0.033 | 0.188 | 0.071 |

| 29 | 0.375 | 0.246 | 0.093 | 0.026 | 0.188 | 0.083 | 0.312 | 0.198 | 0.220 | 0.200 | 0.158 | 0.161 | 0.402 | 0.226 |

| 31 | 0.444 | 0.279 | 0.559 | 0.024 | 0.125 | 0.093 | 0.128 | 0.217 | 0.001 | 0.050 | 0.019 | 0.111 | 0.023 | 0.180 |

| 32 | 0.002 | 0.068 | 0.294 | 0.174 | 0.339 | 0.045 | 0.031 | 0.373 | 0.235 | 0.190 | 0.116 | 0.254 | 0.323 | 0.097 |

| 34 | 0.321 | 0.031 | 0.113 | 0.160 | 0.006 | 0.167 | 0.148 | 0.170 | 0.626 | 0.062 | 0.195 | 0.136 | 0.177 | 0.010 |

| 35 | 0.173 | 0.348 | 0.072 | 0.017 | 0.488 | 0.295 | 0.004 | 0.024 | 0.018 | 0.113 | 0.012 | 0.160 | 0.361 | 0.131 |

| 37 | 0.147 | 0.511 | 0.171 | 0.100 | 0.407 | 0.209 | 0.045 | 0.147 | 0.184 | 0.309 | 0.105 | 0.068 | 0.026 | 0.035 |

| 38 | 0.364 | 0.161 | 0.512 | 0.424 | 0.105 | 0.084 | 0.152 | 0.057 | 0.243 | 0.018 | 0.107 | 0.280 | 0.015 | 0.005 |

| 39 | 0.182 | 0.644 | 0.051 | 0.050 | 0.356 | 0.163 | 0.122 | 0.098 | 0.028 | 0.162 | 0.083 | 0.199 | 0.156 | 0.081 |

| 40 | 0.457 | 0.085 | 0.450 | 0.386 | 0.080 | 0.117 | 0.072 | 0.104 | 0.077 | 0.027 | 0.285 | 0.352 | 0.122 | 0.092 |

References

[1] Van Boekel RLM, Warlé MC, Nielsen RGC, Vissers KCP, van der Sande R, Bronkhorst EM. Relationship between post-operative pain and overall 30-day complications in a broad surgical population. Ann Surg. 2019 May;269(5):856–65. 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002583.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[2] Eriksson K, Wikström L, Fridlund B, Årestedt K, Broström A. Association of pain ratings with the prediction of early physical recovery after general and orthopaedic surgery-A quantitative study with repeated measures. J Adv Nurs. 2017 Nov;73(11):2664–75. 10.1111/jan.13331.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[3] Kooijman MK, Barten DJA, Swinkels ICS, Kuijpers T, de Bakker D, Koes BW, et al. Pain intensity, neck pain and longer duration of complaints predict poorer outcome in patients with shoulder pain – a systematic review. BMC Muscoskel Dis. 2015;16:1–9.10.1186/s12891-015-0738-4Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[4] Jank R, Gallee A, Boeckle M, Fiegl S, Pieh C. Chronic pain and sleep disorders in primary care. Pain Res Treat. 2017 Dec;1–9. 10.1155/2017/9081802.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[5] Masheb RM, Lutes LD, Hyungjin MK, Holleman RG, Goodrich DE, Janney CA, et al. Weight loss outcomes in patients with pain. Obesity. 2015;23:1778–84. 10.1002/oby.21160.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] Nahin RL, DeKosky ST. Comorbid pain and cognitive impairment in a nationally representative adult population. Clin J Pain. 2020 Oct;36(10):725–39. 10.1097/AJP.0000000000000863.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[7] Hinrichs-Rocker A, Schulz K, Järvinen I, Lefering R, Simanski C, Neugebauer EAM. Psychosocial predictors and correlates for chronic post-surgical pain (CPSP) – A systematic review. Eur J Pain. 2009;13:719–30. 10.1016/j.ejpain.2008.07.015.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[8] Lerman SF, Shahar G, Rudich Z. Self-criticism interacts with the affective component of pain to predict depressive symptoms in female patients. Eur J Pain. 2012;16:115–22.10.1016/j.ejpain.2011.05.007Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] Oosterhaven J, Wittink H, Dekker J, Kruitwaagen C, Devillé W. Pain catastrophizing predicts dropout of patients from an interdisciplinary chronic pain management programme: A prospective cohort study. Rehabil Med. 2019;51:761–9. 10.2340/16501977-2609.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[10] Ilgen MA, Zivin K, Austin KL, Bohnert ASB, Czyz EK, Valenstein M, et al. Severe pain predicts greater likelihood of subsequent suicide. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2010 Dec;40(6):597–608.10.1521/suli.2010.40.6.597Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] Feeny D, Huguet N, McFarland BH, Kaplan MS, Orpana H, Eckstrom E. Hearing, mobility, and pain predict mortality: a longitudinal population-based study. J Clin Epidemiol. 2012 Jul;65(7):764–77. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2012.01.003.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[12] Zylla D, Steele G, Gupta P. A systematic review of the impact of pain on overall survival in patients with cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2017;25:1687–98. 10.1007/s00520-017-3614-y.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[13] Ung A, Salamonson Y, Hu W, Gallego G. Assessing knowledge, perceptions and attitudes to pain management among medical and nursing students: a review of the literature. Br J Pain. 2016 Feb;10(1):8–21. 10.1177/2049463715583142.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[14] Raja SN, Carr DB, Cohen M, Finnerup NB, Flor H, Gibson S. The revised international association for the study of pain definition of pain: concepts, challenges and compromises. Pain. 2020 Sep;161(9):1976–82. 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001939.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[15] Breivik H, Eisenberg E, O’Brien T. The individual and societal burden of chronic pain in Europe: the case for strategic prioritisation and action to improve knowledge and availability of appropriate care. BMC Public Health. 2013 Dec;13:1229. 10.1186/1471-2458-13-1229.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[16] Breivik H, Collet B, Ventafridda V, Cohen R, Gallacher D. Survey of chronic pain in Europe: prevalence, impact on daily life and treatment. Eur J Pain. 2006 May;10(4):287–333. 10.1016/j.ejpain.2005.06.009.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[17] Adams SM, Varaei S, Jalalinia F. Nurses’ knowledge and attitude towards post-operative pain management in Ghana. Pain Res Manag. 2020;7. 10.1155/2020/4893707.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[18] Wall SL, Clarke DL, Nauhaus H, Allorto NL. Barriers to adequate analgesia in paediatric burns patients. S Afr Med J. 2020;110(10):1032–5. 10.7196/SAMJ.2020.v110i10.14519.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[19] Ortiz MI, Cuevas-Suárez CE, Cariño-Cortés R, Navarrete-Hernández JJ, González-Montiel CA. Nurses knowledge and attitude regarding pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nurse Educ Pract. 2022;63:103390. 10.1016/j.nepr.2022.103390.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[20] Al Qadire M, Al Khalaileh M. Jordanian nurses’ knowledge and attitude regarding pain management. Pain Manag Nurs. 2014 Mar;15(1):220–8. 10.1016/j.pmn.2012.08.006.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[21] Alqahtani M, Jones L. Quantitative study of oncology nurses’ knowledge and attitudes towards pain management in Saudi Arabian hospitals. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2015 Feb;19(1):44–9. 10.1016/j.ejon.2014.07.013.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[22] Aziato L, Adejumo O. The Ghanaian surgical nurse and post-operative pain management: a clinical ethnographic insight. Pain Manag Nurs. 2014 Mar;15(1):265–72. 10.1016/j.pmn.2012.10.002.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[23] Duke G, Haas B, Yarbrough S, Northam S. Pain management knowledge and attitudes of baccalaureate nursing students and faculty. Pain Manag Nurs. 2013 Mar;14:11–9.10.1016/j.pmn.2010.03.006Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[24] Moceri J, Drevdahl D. Nurses’ knowledge and attitudes toward pain in the emergency department. J Emerg Nurs. 2014 Jan;40:6–12. 10.1016/j.jen.2012.04.014.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[25] Mohammed N. Knowledge and attitudes of pain management by nurses in Saudi Arabian emergency departments: a mixed methods investigation [Internet]. Sydney, Australia: Western Sydney University; 2015. http://researchdirect.westernsydney.edu.au/islandora/object/uws%3A34184.Search in Google Scholar

[26] Tsai F, Tsai Y, Chien C, Lin C. Emergency nurses’ knowledge of perceived barriers in pain management in Taiwan. J Clin Nurs. 2007 Nov;16:2088–95. 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01646.x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[27] Ucuzal M, Doğan R. Emergency nurses’ knowledge, attitude and clinical decision making skills about pain. Int Emerg Nurs. 2015 Apr;23:75–80. 10.1016/j.ienj.2014.11.006.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[28] Zachodnik J, Andersen JH, Geisler A. Barriers in pain treatment in the emergency and surgical department. Dan Med J. 2019;66:A5529.Search in Google Scholar

[29] Bernardi M, Catania G, Lambert A, Tridello G, Luzzani M. Knowledge and attitudes about cancer pain management: a national survey of Italian oncology nurses. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2007 Jul;11:272–9. 10.1016/j.ejon.2006.09.003.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[30] Wang H, Tsai Y. Nurses’ knowledge and barriers regarding pain management in intensive care units. J Clin Nurs. 2010 Nov;19:3188–96. 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2010.03226.x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[31] Davis D, Mazmanian P, Fordis M, Harrison R, Thorpe K, Perrier L. Accuracy of physician self-assessment compared with observed measures of competence – a systematic review. JAMA. 2006 Sep;296:1094–102. 10.1001/jama.296.9.1094.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[32] Mahmood K. Do people overestimate their information literacy skills? a systematic review of empirical evidence on the Dunning-Kruger effect. Commun Inf Lit. 2016 Jan;2:199–213. 10.15760/comminfolit.2016.10.2.24.Search in Google Scholar

[33] Ferrell B, McCaffery M. The Knowledge and Attitudes Survey Regarding Pain (KASRP) [Internet]. MIDSS. 2012 https://prc.coh.org/Knowldege%20%20&%20Attitude%20Survey%207-14%20(1).pdf.Search in Google Scholar

[34] Fager O, Jonsdottir R Knowledge and attitudes towards pain and pain management among emergency nurses – a descriptive study conducted in emergency departments in southern Sweden. [Thesis]. Lund University; 2019. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/338791999_Knowledge_and_attitudes_towards_pain_and_pain_management_among_emergency_nurses_Swedish.Search in Google Scholar

[35] Alkhatib G, Qadire M, Alshraideh J. Pain management knowledge and attitudes of healthcare professionals in primary medical centers. Pain Manag Nurs. 2020 Jun;21:265–70. 10.1016/j.pmn.2019.08.008.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[36] Zuazua-Rico D, Maestro-González A, Mosteioro-Diaz M, Julio Fernández-Garrido J. Spanish version of the Knowledge and Attitudes Survey Regarding Pain. Pain Manag Nurs. 2019 Oct;20(5):497–502. 10.1016/j.pmn.2018.12.007.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[37] Catania G, Costantini M, Lambert A, Luzzani M, Marceca F, Tridello G, et al. Testing an instrument measuring Italian nurses’ knowledge and attitudes regarding pain. Assist Inferm Ric. 2006 Jul;25:149–56.Search in Google Scholar

[38] Chia G, Yap J, Wong Y. Knowledge and attitude towards pain management among nurses in Singapore. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2018 Dec;56:e116–e116. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2018.10.381.Search in Google Scholar

[39] Fernández-Castro M, Martín-Gil B, López M, María Jiménez J, Liébana-Presa C, Fernández-Martínez E. Factors relating to nurses’ knowledge and attitudes regarding pain management in inpatients. Pain Manag Nurs. 2021 Aug;22:478–84.10.1016/j.pmn.2020.12.012Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[40] Tafas C, Patiraki E, McDonald D, Lemonidou C. Testing an instrument measuring Greek nurses’ knowledge and attitudes regarding pain. Cancer Nurs. 2002 Feb;25:8–12. 10.1097/00002820-200202000-00003.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[41] Tse M, Ho S. Enhancing knowledge and attitudes in pain management: a pain management education program for nursing home staff. Pain Manag Nurs. 2014 Mar;15:2–11. 10.1016/j.pmn.2012.03.009.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[42] Utne I, Småstuen M, Nyblin U. Pain knowledge and attitudes among nurses in cancer care in Norway. J Cancer Educ. 2019 Aug;34:677–84. 10.1007/s13187-018-1355-3.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[43] Vickers N, Wright S, Staines A. Surgical nurses in teaching hospitals in Ireland: understanding pain. Br J Nurs. 2014;23:924–9. 10.12968/bjon.2014.23.17.924.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[44] American Educational Research Association. Standards for educational and psychological testing. Washington DC, United States of America: American Educational Research Association; 2014.Search in Google Scholar

[45] Embretson SE, Reise SP. Item response theory for psychologists. 2nd edn. New York, United States of America: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2009.Search in Google Scholar

[46] Brislin RW. Back-translation for cross-cultural research. J Cross-Cult Psychol. 2016;1:185–216. 10.1177/135910457000100301.Search in Google Scholar

[47] Brant JM, Mohr C, Coombs NC, Finn S, Wilmarth E. Nurses’ knowledge and attitudes about pain: personal and professional characteristics and patient reported pain satisfaction. Pain Manag Nurs. 2017;18:214–23. 10.1016/j.pmn.2017.04.003.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[48] Brockopp D, Ryan P, Warden S. Nurses’ willingness to manage the pain of specific groups of patients. Br J Nurs. 2003;12:409–15. 10.12968/bjon.2003.12.7.11261.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[49] Howell D, Butler L, Vincent L, Watt-Watson J, Stearns N. Influencing nurses’ knowledge, attitudes, and practice in cancer pain management. Cancer Nurs. 2000 Feb;23:55–63. 10.1097/00002820-200002000-00009.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[50] Gretarsdottir E, Zoëga S, Tomasson G, Sveinsdottir H, Gunnarsdottir S. Determinants of knowledge and attitudes regarding pain among nurses in a university hospital: a cross-sectional study. Pain Manag Nurs. 2017 Jun;18:144–52.10.1016/j.pmn.2017.02.200Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[51] Colom MN, Sendra-Lluis MA, Castillo-Masa AM, Robleda G. Intraobserver reliability and internal consistency of the Behavioral Pain Scale in mechanically-ventilated patients. Enferm Intensiva. 2015;26:24–31. 10.1016/j.enfi.2014.10.002.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Editorial Comment

- From pain to relief: Exploring the consistency of exercise-induced hypoalgesia

- Christmas greetings 2024 from the Editor-in-Chief

- Original Articles

- The Scandinavian Society for the Study of Pain 2022 Postgraduate Course and Annual Scientific (SASP 2022) Meeting 12th to 14th October at Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen

- Comparison of ultrasound-guided continuous erector spinae plane block versus continuous paravertebral block for postoperative analgesia in patients undergoing proximal femur surgeries

- Clinical Pain Researches

- The effect of tourniquet use on postoperative opioid consumption after ankle fracture surgery – a retrospective cohort study

- Changes in pain, daily occupations, lifestyle, and health following an occupational therapy lifestyle intervention: a secondary analysis from a feasibility study in patients with chronic high-impact pain

- Tonic cuff pressure pain sensitivity in chronic pain patients and its relation to self-reported physical activity

- Reliability, construct validity, and factorial structure of a Swedish version of the medical outcomes study social support survey (MOS-SSS) in patients with chronic pain

- Hurdles and potentials when implementing internet-delivered Acceptance and commitment therapy for chronic pain: a retrospective appraisal using the Quality implementation framework

- Exploring the outcome “days with bothersome pain” and its association with pain intensity, disability, and quality of life

- Fatigue and cognitive fatigability in patients with chronic pain

- The Swedish version of the pain self-efficacy questionnaire short form, PSEQ-2SV: Cultural adaptation and psychometric evaluation in a population of patients with musculoskeletal disorders

- Pain coping and catastrophizing in youth with and without cerebral palsy

- Neuropathic pain after surgery – A clinical validation study and assessment of accuracy measures of the 5-item NeuPPS scale

- Translation, contextual adaptation, and reliability of the Danish Concept of Pain Inventory (COPI-Adult (DK)) – A self-reported outcome measure

- Cosmetic surgery and associated chronic postsurgical pain: A cross-sectional study from Norway

- The association of hemodynamic parameters and clinical demographic variables with acute postoperative pain in female oncological breast surgery patients: A retrospective cohort study

- Healthcare professionals’ experiences of interdisciplinary collaboration in pain centres – A qualitative study

- Effects of deep brain stimulation and verbal suggestions on pain in Parkinson’s disease

- Painful differences between different pain scale assessments: The outcome of assessed pain is a matter of the choices of scale and statistics

- Prevalence and characteristics of fibromyalgia according to three fibromyalgia diagnostic criteria: A secondary analysis study

- Sex moderates the association between quantitative sensory testing and acute and chronic pain after total knee/hip arthroplasty

- Tramadol-paracetamol for postoperative pain after spine surgery – A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study

- Cancer-related pain experienced in daily life is difficult to communicate and to manage – for patients and for professionals

- Making sense of pain in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD): A qualitative study

- Patient-reported pain, satisfaction, adverse effects, and deviations from ambulatory surgery pain medication

- Does pain influence cognitive performance in patients with mild traumatic brain injury?

- Hypocapnia in women with fibromyalgia

- Application of ultrasound-guided thoracic paravertebral block or intercostal nerve block for acute herpes zoster and prevention of post-herpetic neuralgia: A case–control retrospective trial

- Translation and examination of construct validity of the Danish version of the Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia

- A positive scratch collapse test in anterior cutaneous nerve entrapment syndrome indicates its neuropathic character

- ADHD-pain: Characteristics of chronic pain and association with muscular dysregulation in adults with ADHD

- The relationship between changes in pain intensity and functional disability in persistent disabling low back pain during a course of cognitive functional therapy

- Intrathecal pain treatment for severe pain in patients with terminal cancer: A retrospective analysis of treatment-related complications and side effects

- Psychometric evaluation of the Danish version of the Pain Self-Efficacy Questionnaire in patients with subacute and chronic low back pain

- Dimensionality, reliability, and validity of the Finnish version of the pain catastrophizing scale in chronic low back pain

- To speak or not to speak? A secondary data analysis to further explore the context-insensitive avoidance scale

- Pain catastrophizing levels differentiate between common diseases with pain: HIV, fibromyalgia, complex regional pain syndrome, and breast cancer survivors

- Prevalence of substance use disorder diagnoses in patients with chronic pain receiving reimbursed opioids: An epidemiological study of four Norwegian health registries

- Pain perception while listening to thrash heavy metal vs relaxing music at a heavy metal festival – the CoPainHell study – a factorial randomized non-blinded crossover trial

- Observational Studies

- Cutaneous nerve biopsy in patients with symptoms of small fiber neuropathy: a retrospective study

- The incidence of post cholecystectomy pain (PCP) syndrome at 12 months following laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a prospective evaluation in 200 patients

- Associations between psychological flexibility and daily functioning in endometriosis-related pain

- Relationship between perfectionism, overactivity, pain severity, and pain interference in individuals with chronic pain: A cross-lagged panel model analysis

- Access to psychological treatment for chronic cancer-related pain in Sweden

- Validation of the Danish version of the knowledge and attitudes survey regarding pain

- Associations between cognitive test scores and pain tolerance: The Tromsø study

- Healthcare experiences of fibromyalgia patients and their associations with satisfaction and pain relief. A patient survey

- Video interpretation in a medical spine clinic: A descriptive study of a diverse population and intervention

- Role of history of traumatic life experiences in current psychosomatic manifestations

- Social determinants of health in adults with whiplash associated disorders

- Which patients with chronic low back pain respond favorably to multidisciplinary rehabilitation? A secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial

- A preliminary examination of the effects of childhood abuse and resilience on pain and physical functioning in patients with knee osteoarthritis

- Differences in risk factors for flare-ups in patients with lumbar radicular pain may depend on the definition of flare

- Real-world evidence evaluation on consumer experience and prescription journey of diclofenac gel in Sweden

- Patient characteristics in relation to opioid exposure in a chronic non-cancer pain population

- Topical Reviews

- Bridging the translational gap: adenosine as a modulator of neuropathic pain in preclinical models and humans

- What do we know about Indigenous Peoples with low back pain around the world? A topical review

- The “future” pain clinician: Competencies needed to provide psychologically informed care

- Systematic Reviews

- Pain management for persistent pain post radiotherapy in head and neck cancers: systematic review

- High-frequency, high-intensity transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation compared with opioids for pain relief after gynecological surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis

- Reliability and measurement error of exercise-induced hypoalgesia in pain-free adults and adults with musculoskeletal pain: A systematic review

- Noninvasive transcranial brain stimulation in central post-stroke pain: A systematic review

- Short Communications

- Are we missing the opioid consumption in low- and middle-income countries?

- Association between self-reported pain severity and characteristics of United States adults (age ≥50 years) who used opioids

- Could generative artificial intelligence replace fieldwork in pain research?

- Skin conductance algesimeter is unreliable during sudden perioperative temperature increases

- Original Experimental

- Confirmatory study of the usefulness of quantum molecular resonance and microdissectomy for the treatment of lumbar radiculopathy in a prospective cohort at 6 months follow-up

- Pain catastrophizing in the elderly: An experimental pain study

- Improving general practice management of patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain: Interdisciplinarity, coherence, and concerns

- Concurrent validity of dynamic bedside quantitative sensory testing paradigms in breast cancer survivors with persistent pain

- Transcranial direct current stimulation is more effective than pregabalin in controlling nociceptive and anxiety-like behaviors in a rat fibromyalgia-like model

- Paradox pain sensitivity using cuff pressure or algometer testing in patients with hemophilia

- Physical activity with person-centered guidance supported by a digital platform or with telephone follow-up for persons with chronic widespread pain: Health economic considerations along a randomized controlled trial

- Measuring pain intensity through physical interaction in an experimental model of cold-induced pain: A method comparison study

- Pharmacological treatment of pain in Swedish nursing homes: Prevalence and associations with cognitive impairment and depressive mood

- Neck and shoulder pain and inflammatory biomarkers in plasma among forklift truck operators – A case–control study

- The effect of social exclusion on pain perception and heart rate variability in healthy controls and somatoform pain patients

- Revisiting opioid toxicity: Cellular effects of six commonly used opioids

- Letter to the Editor

- Post cholecystectomy pain syndrome: Letter to Editor

- Response to the Letter by Prof Bordoni

- Response – Reliability and measurement error of exercise-induced hypoalgesia

- Is the skin conductance algesimeter index influenced by temperature?

- Skin conductance algesimeter is unreliable during sudden perioperative temperature increase

- Corrigendum

- Corrigendum to “Chronic post-thoracotomy pain after lung cancer surgery: a prospective study of preoperative risk factors”

- Obituary

- A Significant Voice in Pain Research Björn Gerdle in Memoriam (1953–2024)

Articles in the same Issue

- Editorial Comment

- From pain to relief: Exploring the consistency of exercise-induced hypoalgesia

- Christmas greetings 2024 from the Editor-in-Chief

- Original Articles

- The Scandinavian Society for the Study of Pain 2022 Postgraduate Course and Annual Scientific (SASP 2022) Meeting 12th to 14th October at Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen

- Comparison of ultrasound-guided continuous erector spinae plane block versus continuous paravertebral block for postoperative analgesia in patients undergoing proximal femur surgeries

- Clinical Pain Researches

- The effect of tourniquet use on postoperative opioid consumption after ankle fracture surgery – a retrospective cohort study

- Changes in pain, daily occupations, lifestyle, and health following an occupational therapy lifestyle intervention: a secondary analysis from a feasibility study in patients with chronic high-impact pain

- Tonic cuff pressure pain sensitivity in chronic pain patients and its relation to self-reported physical activity

- Reliability, construct validity, and factorial structure of a Swedish version of the medical outcomes study social support survey (MOS-SSS) in patients with chronic pain

- Hurdles and potentials when implementing internet-delivered Acceptance and commitment therapy for chronic pain: a retrospective appraisal using the Quality implementation framework

- Exploring the outcome “days with bothersome pain” and its association with pain intensity, disability, and quality of life

- Fatigue and cognitive fatigability in patients with chronic pain

- The Swedish version of the pain self-efficacy questionnaire short form, PSEQ-2SV: Cultural adaptation and psychometric evaluation in a population of patients with musculoskeletal disorders

- Pain coping and catastrophizing in youth with and without cerebral palsy

- Neuropathic pain after surgery – A clinical validation study and assessment of accuracy measures of the 5-item NeuPPS scale

- Translation, contextual adaptation, and reliability of the Danish Concept of Pain Inventory (COPI-Adult (DK)) – A self-reported outcome measure

- Cosmetic surgery and associated chronic postsurgical pain: A cross-sectional study from Norway

- The association of hemodynamic parameters and clinical demographic variables with acute postoperative pain in female oncological breast surgery patients: A retrospective cohort study

- Healthcare professionals’ experiences of interdisciplinary collaboration in pain centres – A qualitative study

- Effects of deep brain stimulation and verbal suggestions on pain in Parkinson’s disease

- Painful differences between different pain scale assessments: The outcome of assessed pain is a matter of the choices of scale and statistics

- Prevalence and characteristics of fibromyalgia according to three fibromyalgia diagnostic criteria: A secondary analysis study

- Sex moderates the association between quantitative sensory testing and acute and chronic pain after total knee/hip arthroplasty

- Tramadol-paracetamol for postoperative pain after spine surgery – A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study

- Cancer-related pain experienced in daily life is difficult to communicate and to manage – for patients and for professionals

- Making sense of pain in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD): A qualitative study

- Patient-reported pain, satisfaction, adverse effects, and deviations from ambulatory surgery pain medication

- Does pain influence cognitive performance in patients with mild traumatic brain injury?

- Hypocapnia in women with fibromyalgia

- Application of ultrasound-guided thoracic paravertebral block or intercostal nerve block for acute herpes zoster and prevention of post-herpetic neuralgia: A case–control retrospective trial

- Translation and examination of construct validity of the Danish version of the Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia

- A positive scratch collapse test in anterior cutaneous nerve entrapment syndrome indicates its neuropathic character

- ADHD-pain: Characteristics of chronic pain and association with muscular dysregulation in adults with ADHD

- The relationship between changes in pain intensity and functional disability in persistent disabling low back pain during a course of cognitive functional therapy

- Intrathecal pain treatment for severe pain in patients with terminal cancer: A retrospective analysis of treatment-related complications and side effects

- Psychometric evaluation of the Danish version of the Pain Self-Efficacy Questionnaire in patients with subacute and chronic low back pain

- Dimensionality, reliability, and validity of the Finnish version of the pain catastrophizing scale in chronic low back pain

- To speak or not to speak? A secondary data analysis to further explore the context-insensitive avoidance scale

- Pain catastrophizing levels differentiate between common diseases with pain: HIV, fibromyalgia, complex regional pain syndrome, and breast cancer survivors

- Prevalence of substance use disorder diagnoses in patients with chronic pain receiving reimbursed opioids: An epidemiological study of four Norwegian health registries

- Pain perception while listening to thrash heavy metal vs relaxing music at a heavy metal festival – the CoPainHell study – a factorial randomized non-blinded crossover trial

- Observational Studies

- Cutaneous nerve biopsy in patients with symptoms of small fiber neuropathy: a retrospective study

- The incidence of post cholecystectomy pain (PCP) syndrome at 12 months following laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a prospective evaluation in 200 patients

- Associations between psychological flexibility and daily functioning in endometriosis-related pain

- Relationship between perfectionism, overactivity, pain severity, and pain interference in individuals with chronic pain: A cross-lagged panel model analysis

- Access to psychological treatment for chronic cancer-related pain in Sweden

- Validation of the Danish version of the knowledge and attitudes survey regarding pain

- Associations between cognitive test scores and pain tolerance: The Tromsø study

- Healthcare experiences of fibromyalgia patients and their associations with satisfaction and pain relief. A patient survey

- Video interpretation in a medical spine clinic: A descriptive study of a diverse population and intervention

- Role of history of traumatic life experiences in current psychosomatic manifestations

- Social determinants of health in adults with whiplash associated disorders

- Which patients with chronic low back pain respond favorably to multidisciplinary rehabilitation? A secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial

- A preliminary examination of the effects of childhood abuse and resilience on pain and physical functioning in patients with knee osteoarthritis

- Differences in risk factors for flare-ups in patients with lumbar radicular pain may depend on the definition of flare

- Real-world evidence evaluation on consumer experience and prescription journey of diclofenac gel in Sweden

- Patient characteristics in relation to opioid exposure in a chronic non-cancer pain population

- Topical Reviews

- Bridging the translational gap: adenosine as a modulator of neuropathic pain in preclinical models and humans

- What do we know about Indigenous Peoples with low back pain around the world? A topical review

- The “future” pain clinician: Competencies needed to provide psychologically informed care

- Systematic Reviews

- Pain management for persistent pain post radiotherapy in head and neck cancers: systematic review

- High-frequency, high-intensity transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation compared with opioids for pain relief after gynecological surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis

- Reliability and measurement error of exercise-induced hypoalgesia in pain-free adults and adults with musculoskeletal pain: A systematic review

- Noninvasive transcranial brain stimulation in central post-stroke pain: A systematic review

- Short Communications

- Are we missing the opioid consumption in low- and middle-income countries?

- Association between self-reported pain severity and characteristics of United States adults (age ≥50 years) who used opioids

- Could generative artificial intelligence replace fieldwork in pain research?

- Skin conductance algesimeter is unreliable during sudden perioperative temperature increases

- Original Experimental

- Confirmatory study of the usefulness of quantum molecular resonance and microdissectomy for the treatment of lumbar radiculopathy in a prospective cohort at 6 months follow-up

- Pain catastrophizing in the elderly: An experimental pain study

- Improving general practice management of patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain: Interdisciplinarity, coherence, and concerns

- Concurrent validity of dynamic bedside quantitative sensory testing paradigms in breast cancer survivors with persistent pain

- Transcranial direct current stimulation is more effective than pregabalin in controlling nociceptive and anxiety-like behaviors in a rat fibromyalgia-like model

- Paradox pain sensitivity using cuff pressure or algometer testing in patients with hemophilia

- Physical activity with person-centered guidance supported by a digital platform or with telephone follow-up for persons with chronic widespread pain: Health economic considerations along a randomized controlled trial

- Measuring pain intensity through physical interaction in an experimental model of cold-induced pain: A method comparison study

- Pharmacological treatment of pain in Swedish nursing homes: Prevalence and associations with cognitive impairment and depressive mood

- Neck and shoulder pain and inflammatory biomarkers in plasma among forklift truck operators – A case–control study

- The effect of social exclusion on pain perception and heart rate variability in healthy controls and somatoform pain patients

- Revisiting opioid toxicity: Cellular effects of six commonly used opioids

- Letter to the Editor

- Post cholecystectomy pain syndrome: Letter to Editor

- Response to the Letter by Prof Bordoni

- Response – Reliability and measurement error of exercise-induced hypoalgesia

- Is the skin conductance algesimeter index influenced by temperature?

- Skin conductance algesimeter is unreliable during sudden perioperative temperature increase

- Corrigendum

- Corrigendum to “Chronic post-thoracotomy pain after lung cancer surgery: a prospective study of preoperative risk factors”

- Obituary