Abstract

Background & objective

Psychologically informed care has been proposed to improve treatment outcomes for chronic pain and aligns with a person-centered approach. Yet implementation lags behind, and studies suggest that a lack of competency leads to poor results. It is unclear what training clinicians require to deliver this care.

We examine how we might improve psychologically informed care guided by the needs of the patient and in congruence with the scientific literature with a particular focus on how competencies might be upgraded and implementation enhanced.

Methods

We selectively review the literature for psychologically informed care for pain. The patient’s view on what is needed is contrasted with the competencies necessary to meet these needs and how treatment should be evaluated.

Results

Patient needs and corresponding competencies are delineated. A number of multi-professional skills and competencies are required to provide psychologically informed care. Single-subject methodologies can determine whether the care has the desired effect for the individual patient and facilitate effectiveness. We argue that becoming a competent “pain clinician” requires a new approach to education that transcends current professional boundaries.

Conclusions

Providing person-centered care guided by the needs of the patient and in line with the scientific literature shows great potential but requires multiple competencies. We propose that training the pain clinician of the future should focus on psychologically informed care and the competencies required to meet the individual’s needs. Single-subject methodology allows for continual evaluation of this care.

Despite decennia of clinical research, the efficacy of current treatments for people with disabling pain remains limited. Individualized psychologically informed care has been proposed as an avenue to improve treatment outcomes. However, questions concerning who might be best equipped to provide such psychologically informed treatment and the competencies required have hampered its implementation. Some studies suggest that it is a lack of competency that leads to poor results [1,2]. Yet, clinicians may be faced with either attempting to incorporate aspects of psychologically informed care into their treatment without formal training or omitting them. We argue that a focus on the patient’s needs and the competencies required to appropriately meet them with evidence-based techniques is needed. Rather than enhancing professional silos, we argue that a new education for pain clinicians is urgently needed.

Treating disabling pain is a challenge, and at the center is the patient him/herself. To effectively treat chronic disabling pain requires that the patient learns new, often very different, conceptions and behaviors and then implement them into everyday life. This in turn requires that the pain clinician has the knowledge and skills to enable the patient to succeed. Consequently, attention has shifted from a focus on which treatments may be effective for a group of people toward new ways of implementing care individualized for a person. This is appealing because best-practice guidelines are based on RCTs of large numbers of patients reporting the averaged outcomes, whereas person-centered care embraces the unique needs and characteristics of each individual patient. Person-centered care incorporates each individual’s context, knowledge, needs, values, goals, and preferences into shared decision-making about management [3]. This is in line with patient calls for care that is individualized to their concerns, needs and preferences [4]. In this article, we review the background of disabling pain problems and explore the patient’s view of what best care should consist of. Subsequently, we explore what competencies are needed to provide evidence based person-centered pain care. While focusing on pain problems, the approach could be transferrable to other chronic health conditions.

1 Best practice care for people with disabling pain

Best practice care for people with disabling pain is always based on triaging, which includes screening for red flags and serious pathology. We take the perspective of the patient, and his/her needs once serious pathology is excluded. The focus of this article is on known factors that drive or maintain chronic pain, often musculoskeletal pain, and its associated disability. The development of disabling pain is a process over time where many of the psychological and social factors driving chronification are present early on [5,6]. Therefore, identifying and dealing with these factors on the individual level is critical from the first healthcare visit onwards. Once triaging has been achieved, the primary treatment for disabling pain will most often be based on a form of pain rehabilitation where behavior change is central.

As the pain problem becomes disabling, the cornerstone of treatment is creating the opportunity to learn self-management skills to address pain, distress, and functional problems. This typically includes helping patients to develop a clear understanding of the personally relevant underlying factors and processes linked to their condition; skills to deal with functional limitations (e.g., exercise, scheduling, pacing), avoidance of movements and activity (e.g., exposure and graded activity), pain intensity (e.g., relaxation, acceptance, mindfulness, physical activation), and emotional reactions (e.g., emotion regulation skills). Addressing relevant lifestyle aspects such as physical activity, sleep, work, social stressors, diet, and smoking may also be indicated.

These self-management skills all involve behavior change and are based on the principles of learning such as expounded in William Fordyce’s pioneering book [7], and their further development [8,9]. While behavior change via self-management is a key to the biopsychosocial approach, it is not always achieved in practice [10].

1.1 Current treatment approaches are failing

Patients currently receive a wide array of examinations, advice, and treatments following an algorithm that reinforces referrals where each provider works from their own “silo” view [11–13]. If the treatment fails, then the patient may move on to other examinations or treatments provided by other health care professionals – often encompassing yet another set of explanations, advice, and information for the patient, which could be harmful if it induces, for example, confusion or pain-related fear [14]. As an illustration, while screening for psychosocial yellow flags is recommended at the first visit, it is infrequently employed [15,16]. When screening occurs, it often has little impact on the choice or delivery of treatment [16]. Consequently, although a biopsychosocial approach is recommended to prevent, treat, or enhance self-management of the disabling pain, patients instead usually receive single modal biomedically orientated treatments [11].

1.2 Individualized psychologically informed care

Psychologically informed care has been proposed to bridge the gap between recommendation and implementation of the biopsychosocial approach. Psychologically informed care refers to the integration of psychological principles into health care in line with the person’s goals, thus individualized. It involves understanding the content and mechanisms of psychological interventions as well as efficiency in delivering the interventions appropriately in a healthcare setting, while enabling other care, e.g., pain management or lifestyle changes. While psychologically informed care thus fully aligns with a person-centered approach, it highlights psychological factors. Some interventions for disabling pain such as increasing physical activity can be understood and motivated from both a psychological and a physiological perspective. Indeed, several techniques that are described as psychological in the field of pain management may fall into the domain of various professions (including physical therapists, psychologists, occupational therapists, nurses, and doctors).

When working with people suffering disabling pain, psychologically informed treatment involves employing some form of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) (including its variations, e.g., acceptance and commitment therapy, dialectical behavior therapy, cognitive functional therapy), but there is no clear consensus for establishing professional competency in delivering this. Because individualized psychologically informed treatment might be provided by a variety of professionals, understanding the competencies necessary to provide this effectively is important [1,17,18]. While enhancing understanding and skills from a psychological perspective is important across professions, psychologists bring a long education, and considerable experience with practical application of psychological techniques. At the same time, other professionals offer skills in the field of pain and rehabilitation that are not core training for psychologists. The key question is what competencies and training may be required across professions to address the care priorities of people with pain, and their individual barriers to recovery.

1.3 Competency-based training is needed

The aspiration to improve outcomes for people living with pain is progressing slowly. Psychologically informed treatment is recommended, and research continues to accumulate exponentially. Nonetheless, clinicians in clinical trials may not be trained to competency, and the group-based effect sizes are said to be small and have not increased significantly over time [1,19,20]. For example, the implementation of one psychologically informed method, risk-based stratified care, showed no significant benefit in recent RCTs [16,21–23]. To improve, we need to reconsider how advances might be accomplished.

One approach is to include a patient perspective to bridge the needs of patients with the scientific evidence for treatment, while ensuring that treating clinicians are trained to competently deliver this care. Today, the best-practice recommendations are based on large, group-based, randomized controlled trials of various treatment methods. Since results are based on group averages, we know little about what works for whom or the requirements of an individual patient [24]. To date, there have been challenges in incorporating the patient’s perspective into clinical practice. For example, attempts have often inadvertently put the responsibility for the clinician’s agenda on the patient, e.g., by providing psychoeducation suggesting behavior change rather than listening to the patient’s needs and coaching skills. Yet, we know that patient preferences, beliefs, and needs vary and are central to treatment outcome and satisfaction [25].

2 What kind of care do patients want?

2.1 Making sense of pain

Several studies, mainly of a qualitative nature, have explored the needs and expectations of patients suffering pain. One part of this research has focused on “diagnostic uncertainty” since then complexity of many pain conditions may be difficult for providers to grasp [26]. This uncertainty is related to dissatisfaction and searching for alternative explanations – but is not reduced simply by conducting additional testing [27]. In contrast, patients expect to receive a clear diagnosis based on imaging technology and control over their pain when seeking care [28]. Since an accurate diagnosis cannot be made for most people with chronic pain, reductionistic, single-modal diagnoses (often linked to anatomical structure) are frequently made, which may overlook the complexity of the patient’s presentation [29]. Consequently, when their pain is perceived as unpredictable, uncontrollable, and intense, patients may view it as a threat [30]. The major message to clinicians from patients, however, is to be taken seriously so that the clinician pays as much attention to them as they do to a specific intervention [31,32].

2.2 Individualized whole-person care

When boiled down, three main areas of need emerge [4]. First, patients desire clear and empathetic communication [31–34]. Their desire is a clinician who takes his/her time and listens deeply. This entails communication skills where validation is central to exploring their pain experience, concerns, and fears as well as their expectations and goals [34]. Second, is an understanding of the problem, that is, the impact of the pain on their life. This might be expressed as getting a diagnosis or as understanding the multidimensional factors relevant to the patient’s condition [32–34]. This might be construed as developing a mutual understanding or model of the problem. Patients value a strong therapeutic relationship with their clinician where they work in partnership. Third, is the content of the care. Patients desire to receive the most effective treatment for pain relief, functional restoration, and improved quality of life in an individualized intervention that is understandable based on the conceptualized model of the problem [31–34] (Table 1). Incorporating the patient view into care appears to have great potential as all three might be addressed to upgrade care. Similarly, all three areas involve behavior change and the use of psychological techniques, e.g., in communication and the development of goals.

A summary of the care people with disabling chronic pain desire and how it might be delivered

| Care wanted | How to deliver | Comment | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Empathetic, validating, and caring communication | Individualized psychologically informed care | Communication skills training is warranted |

| 2 | Make sense of the pain | Explain pain in a clear, interactive, and personalized way adapted to the patient's level of health literacy | Do not scare or invalidate “the pain is in your brain” |

| 3 | Understand prognosis | Clear and honest information, including consequences for patient's daily life | Even if prognosis is variable and cure is not likely |

| 4 | Address individual concerns and goals | Behavior change through cognitive behavioral treatment. | Evidence-based individualized care, adapted to the patients cultural context |

| 5 | Understand the risks and costs of proposed interventions | Clear information about risks, costs, and evidence for interventions | Shared decision making |

| 6 | Learn self-management skills | Clear information and coaching of selected skills | Behavior change techniques and skills are required |

| 7 | Resume daily life activities and life-valued goals | Early discussion of valued life goals that is balanced in treatment planning | Personally relevant short and long SMART goals |

2.3 Illustrative cases

Patients bring to the clinic a unique mix of needs, desires, multidimensional contributing factors, and conditions. To illustrate this, we present two real cases in Table 2. The cases differ in their diagnosis (spinal stenosis vs disc degeneration) and life situation (63 single vs 48 undergoing a divorce). Both are distressed by the threat associated with their structural diagnosis; they lack a clear understanding regarding the fluctuating nature of their pain and are frustrated at not being able to control the pain and resume their normal life. Let us see how this plays out in our understanding of the cases and an approach to their treatment with an eye on what competencies are needed to meet the needs of Jannick and Susan.

Two cases of disabling chronic pain

|

|

|---|---|

| Description | Description |

| Jannick is a 65-year-old single man with a 3-year history of back and left leg pain. His pain began at a stressful time of his life related to the COVID lockdown. He had seen two physiotherapists who had given him hands-on treatment with only short-term relief. He was referred to an Orthopaedic specialist who referred him for an MRI scan, which showed severe spinal stenosis at L5S1. He was advised that he required spinal decompression surgery; otherwise, he was at risk of neurological compromise. Jannick reported that he was “terrified” by spinal surgery as his brother had undergone similar surgery and has not recovered well from it. | Susan is a 48-year-old single mother with two teenage children who reported an insidious onset of low back pain 2 years earlier. She reported her low back pain to be severe and disabling; she was unable to exercise and struggling to do basic activities such as shopping and housework. She also reported that her sleep was very disrupted, and she felt fatigued and depressed. Her pain started at a very stressful time in her life when her husband left her, and she was left to care for her two children with little financial support. Susan was engaged in a legal dispute over the divorce. Her MRI showed a degenerative disc at L5S1 with modic changes at the end-plate. She had undergone various treatments including physiotherapy, massage, spine injections, pharmacology but with little long-term benefit. She was advised that her only option was a spinal fusion. She was taking opioid, anti-inflammatory, and sleeping medications. She was seeing a clinical psychologist to help her deal with the stress of the marriage breakup. |

| Jannick reported that pain restricted most aspects of his life including his ability to stand, walk, bend, lift and garden. He was working part time as a receptionist. He had stopped all forms of physical activity, gardening due to the ‘fear of paralysis’. He spent most of his non-work time resting in bed. The pain had impacted all aspects of his life and he was fearful for his future. He wanted a 2nd opinion to see if there were any non-surgical options. He was taking anti-inflammatory and sleeping medications. | She was seeking a second opinion as she was worried how she would cope with her children undergoing major surgery. |

| Multidimensional profile | Multidimensional profile |

| Pathoanatomical factors: | Pathoanatomical factors: |

|

|

Physical factors:

|

Physical factors:

|

Lifestyle factors:

|

Lifestyle factors:

|

Cognitive factors:

|

Cognitive factors:

|

Emotional factors:

|

Emotional factors:

|

Social factors:

|

Social factors:

|

Sensory factors:

|

Sensory factors:

|

Health factors:

|

Health factors:

|

| Jannick’s perspective and needs | Susan’s perspective and needs |

| Jannick says he is terrified of becoming paralyzed and also of undergoing spinal surgery. He feels like his life has ended, and he cannot see a way out | Susan is confused about her options since she has been recommended surgery but is skeptical that it will help. She is struggling with her life situation and wants support and guidance |

| His goals are to increase his functional capacity and quality of life (walk in nature, garden, play with grandchildren) without spine surgery – and without “damaging the nerves” | Her goals are to develop pain control strategies, functional enhancement, and quality of life (housework, lift, and exercise in the gym) without undergoing spine surgery |

| Joint treatment plan | Joint treatment plan |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

3 Core factors, patient needs, and competencies

While acknowledging the essential role of biological and social factors, there is also a good understanding of how chronic pain develops and is maintained from a psychological perspective [6]. In this section, we review the fear-avoidance (FA) model since it incorporates core psychological factors that drive or maintain disabling chronic pain problems and demonstrates how behavioral change occurs over time [35]. We subsequently relate these factors, which are targets in treatment, to the needs of the patient, underscoring the need for behavior change. Finally, we describe the competencies professionals need to provide such interventions.

3.1 Core factors

Chronic pain is understood as the result of the dynamic interaction among physiological, psychological, and social factors, which perpetuate and may even worsen the pain experience and disability [36,37]. For example, multiple neurobiological mechanisms are involved in the development of pain chronicity [37–39], where psychological and social factors are understood to interact with physical pathology, e.g., when physical factors may interact with protective guarding and avoidance. Indeed, pain, emotional distress, and disturbances in function are to a large degree influenced by psychological factors.

Based on knowledge of the close relationship between pain and fear, the FA model proposes that fear-related protective behaviors can drive a vicious cycle with subsequent activity limitations, disability, negative affect, and pain [35]. Negative beliefs about the cause of the pain, fear of pain, and avoidance behaviors have been found to be associated with pain chronicity and pain-related disability [40–44] and are often enhanced by interactions with clinicians who provide scary diagnoses as is illustrated in the two cases. Jannick, for example, received information that he had a condition that could lead to paralysis whereby he avoided his ordinary activities and spent a lot of time resting to “protect” his back.

The FA model also describes a recovery pathway. When pain is perceived as having a low threat value, the benefits of engaging in activities of daily life may outweigh the threat of pain. Consequently, the individual engages in valued activities, which is associated with recovery and decreased disability, instead of avoidance or other protective behaviors [45]. This is an essential part of the model illustrating a healthy response. We might assume that if Susan and Jannick had received an understanding of their pain, which supported that ordinary movements and activities were safe, the threat value of their pain (fear) would have been minor, and they would have given priority to engaging in daily activities that promote recovery.

The FA model also offers insight into treatments such as exposure therapy. This treatment systematically “exposes” the patient to feared movements and situations that are expected to increase pain and harm. In essence, the goal is to challenge these expectations and acquire new and non-threatening knowledge about the pain–harm relationship. As a result, valued life goals are approached despite being painful, rather than avoided. Exposure treatment has been shown to be effective for various pain conditions and in varying settings [46–49]. A particular form of exposure is cognitive functional therapy, where the exposure element is combined and incorporated into a physical therapy setting [50,51]. Another variation is the hybrid treatment, where exposure to movements is combined with emotion regulation [52,53]. Both also include empathetic dialog and components to help patients make sense of their pain.

The FA model is useful in the clinic when identifying core factors to target in treatment, e.g., negative beliefs and expectations, pain-related fear, and avoidance. These are addressed by exposure-based CBT interventions and should, according to the model, result in improvements in pain and function over time. Note that interventions entail forms of behavior change, e.g., in increasing activities for Jannick. Reduction in pain-related fears, as well as improvements in pain self-efficacy, pain acceptance, and psychological flexibility, have also been found to mediate the effects of CBT on pain disability [54–56]. Indeed, a transdiagnostic approach supports the importance of cognitive and behavioral processes across pain problems and emotional problems [57,58]. Susan may, for example, benefit from an intervention like exposure that reduces her emotional distress while also increasing her ability to participate in activities despite pain.

3.2 What competencies are required to meet patients’ needs?

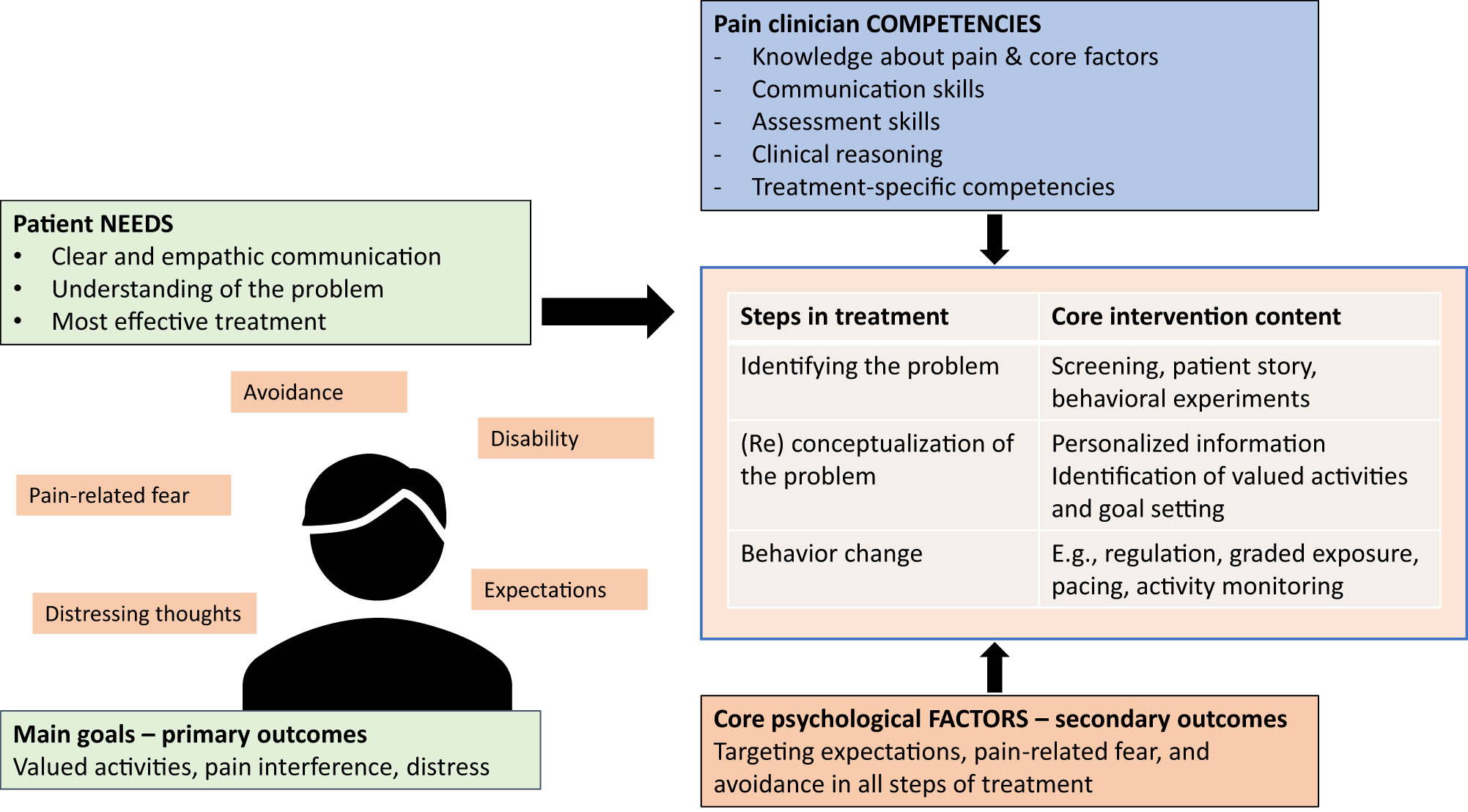

To deliver care that addresses and is uniquely matched to the patient’s needs and prerequisites requires a number of skills. In this section, we summarize competencies that are suggested to be necessary based on earlier work by Roth and Pilling [59]. Some of these skills are important for any clinician and transferrable to other health conditions (e.g., communication skills), while others are specific to a pain clinician (e.g., exposure). These skills span multiple domains: person-centered communication and care; contemporary knowledge about pain, underlying pain processes, and behavioral change; clinical assessment including conducting behavioral experiments; clinical reasoning processes and treatment planning and implementation. All need to be tailored to the individual, e.g., based on preferences, health literacy, and needs. Table 3 provides a more detailed list of psychologically informed competencies required to provide person-centered care. They highlight the importance of the pain clinician being able to incorporate different skills and core content throughout the steps of treatment, e.g., emphatic communication, knowledge about pain and maladaptive psychological mechanisms, and guidance in behavior change and making sense of the pain problem.

Core competencies required by clinicians in order to provide person-centered care for people with pain

| Communication |

|

| Knowledge |

|

| Assessment |

|

| Clinical reasoning |

|

| Treatment |

|

| Meta-competencies |

|

4 Testing the value of the intervention

Once targets have been identified and a treatment method for behavior change has been implemented, determining whether the treatment is, in fact, having the desired effect is essential since it guides further decision-making and adaptation.

In the evaluation of the effectiveness of a particular intervention, there are several aspects to be considered: First, what are the primary (ultimate goals of the treatment) and secondary outcomes (means by which the target can be reached)? Second, how to establish whether the secondary variables have changed, and if so whether they also affected the improvement of the primary outcome as well? Third, what are the implications for the continued care of the individual with chronic pain?

4.1 Identifying and measuring relevant primary and secondary outcome variables

As previously outlined, concerns regarding pain can provoke fear and protective behaviors such as guarding and avoidance, that paradoxically worsen the situation and may increase pain and disability. There are various measurement tools that have been developed to assess these concerns [60], as well as the level of disability [61]. Most of these are generic questionnaires that measure a latent construct (such as pain anxiety, catastrophizing, disability etc), measured via items representing different expressions of that particular construct. Despite the panoply of self-report measures, one of the challenges is to find the right measure that aligns with the individual’s idiosyncratic concerns and goals. For example, if a person’s specific belief is that their persistent low back is a sign that the nerves are being compressed with the threat of continence and paralysis, it will be impossible to find an existing questionnaire that exactly measures this belief.

This has led to calls for the use of idiographic measures rather than group-based questionnaires [62]. Most often, personally relevant treatment targets are derived from a thorough interview and functional analysis, which includes a description of the problem with its history, the identification of the antecedent stimuli or events and the consequences of the problem, as well as the analysis of the meaning of the behavior [63]. Relevant targets can be the person’s main complaint, which can be a bodily symptom (pain, fatigue, etc.), a set of behaviors (“I am lying in bed several times a day because of the pain and fear of damaging the nerves”), distressing thoughts (“I imagine myself ending up in a wheelchair soon”), and negative feelings (“I feel frustrated not being able to do the things I ought to do”). In addition to these concerns, the pain may also interfere with reaching specific valued goals (“I want to be able to play soccer with my grandson,” “I want to get back to full time work”). To assess these, existing questionnaires will not do the job, and an idiographic approach is more appropriate. One possibility is to translate the findings of a behavioral analysis into a diary that can be used to monitor the extent to which the problem behavior fluctuates over time.

It may be helpful to distinguish between primary and secondary targets (outcomes). The primary ones are those that represent the main concern or goals of the individual, whereas the secondary outcomes represent the changes that are deemed necessary to reach the primary ones. For example, if Susan’s goal of getting back to keyboard work (primary outcomes), the secondary target may be modifying the disturbing belief that sitting with a painful back will lead to tissue damage, which in turn is associated with avoidance of sitting activities (secondary outcomes).

4.2 Testing the target achievement

There are several ways to test whether the personally relevant targets have been achieved. However, in healthcare settings with time pressure, the evaluation is often limited to a post-treatment verbal evaluation of the treatment effects. This is a crude and imprecise measurement, of which the knowledge is likely to be influenced by memory bias and the willingness to please the clinician. A more reliable approach is when baseline measures are taken at the start of the treatment. This provides the possibility to at least observe a difference between both the pre- and the post-measure. An even better option is to monitor target behavior repeatedly over time in the same individual using a diary given that people’s behavior is notoriously dynamic and varies according to learning and changes in context. Although such a method nicely visualizes the dynamics of the changes occurring during the treatment, it cannot establish any causality. A solution to this problem is the single-case experimental design (SCED), which considers these threats to the internal and external validity of the observed changes.

SCEDs are defined as “designs that are applied to experiments in which one entity is observed repeatedly during a certain period of time under different levels of at least one independent variable” [64]. The typical features of SCEDs are that the focus is on one individual, the repeated measurements or observations, and the start of an intervention after a no-treatment baseline. It is beyond the scope of the present contribution to give a complete overview of all viable techniques for the analysis of SCED data, but there are three different kinds of analysis that can be applied in order to reach a conclusion about the value of the treatment: visual analysis, effect size calculation, and inferential statistics [65].

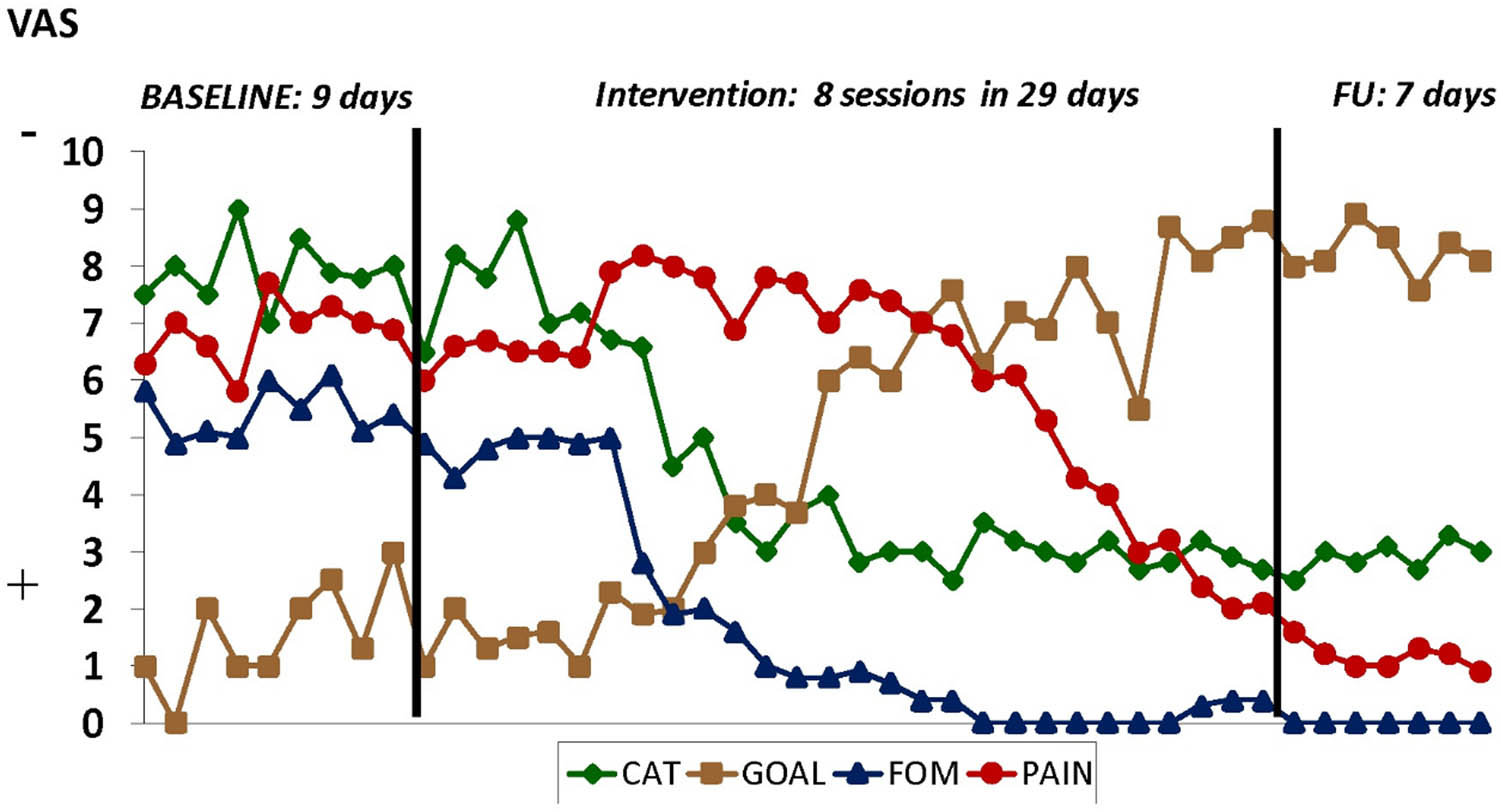

A graphical presentation of the data provides rich information about how much variability there was in the baseline, if any visible change occurs, when the change occurs, and how stable the change is over time. Tools to assist the clinician in evaluating the visual analysis of single-case data exist [66]. Figure 1 graphically displays Jannick’s diary data using numerical rating scales before, during, and after the personalized exposure treatment. It shows how Jannick’s pain beliefs (his surgeon told her the pain is due to squashed nerves), fear, and pain intensity change over time, as well as his goal achievement. In SCED, the visual analysis can be complemented with an effect size calculation, which quantifies the magnitude of change between the baseline and treatment phases. This metric also allows for comparisons within and across individuals and for the aggregation of effects across individuals. In the long run, this contributes to the knowledge base and the inferences that can be made about the external validity of a particular treatment. Finally inferential statistics help us decide with which certainty we can make inferences about the observed changes between the baseline and the treatment phase. An interesting option is the randomization test, which assumes a random assignment procedure (e.g., random determination of the moments of phase change) and does not rely on specific distributions of the data [67].

Fictive results of the exposure treatment of Jannick using a single-subject experimental design. CAT = catastrophizing; specifically “pain is due to “squashed nerves,” FOM = fear of movement, GOAL ATTAINMENT = “bicycling,” PAIN = pain intensity.

4.3 Implications for clinical practice

Given that the clinical reasoning process and patient formulation provide the elements for a (preliminary) clinical hypothesis of how the person’s complaints may have been caused or maintained, the intervention can be considered a test of that theory. If no change in the primary target outcome is observed, we need to understand why. One is insufficient treatment fidelity, which means that the treatment has not taken place as intended. A second reason may be the lack of changes in the secondary variables. If Susan and Jannicks’ beliefs about the threat of certain movements have not changed, it is unlikely that their avoidance behavior will decrease, or by extension, their disability. There might also be multiple causes of disability. New information calls for a revision of our theory, and a new treatment can be initiated. For example, in the case of interpersonal conflicts at work or home, a problem-solving training might be introduced. The new intervention again can best be evaluated using a SCED. This iterative process can be repeated until the needs of the person have been met, and the goals reached.

5 Implementation into practice

The exploration of an approach to the care of patients with disabling pain that is guided by the needs of the patient and in congruence with the scientific literature has considerable potential. We believe that this is a pathway for improving patient care. It also underscores that healthcare providers of the future will need a unique competency-based training program as pain clinicians.

This review suggests that the pain clinician of the future should focus on meeting the patient’s needs with evidence-based treatment content, which requires certain competencies, as illustrated in the overview of the treatment process in Figure 2. Importantly, some of these competencies are important for any clinician (e.g., person-centered communication), while others are specific to treating people with pain (e.g., exposure therapy). Patient needs are central to developing the intervention, as are the core factors affecting the pain and disability. We believe that educational programs should incorporate this model and that a new professional category be instituted, the pain clinician. Since a major stumbling block is reaching all players and ensuring full competency [1], a unique professional education for pain clinicians that transcends current professional boundaries could provide training to competency in the skills we have described, which in turn should improve care for patients suffering disabling pain. Certainly, Jannick and Susan would appreciate and deserve care from such a well-trained pain clinician.

Overview of the process of incorporating patient needs and scientific evidence into all three steps of developing an individualized treatment for reaching the best long-term results. Note that the competencies required override all steps in the treatment.

5.1 Evidence for this approach

Developing a program based on this model can benefit from existing examples that already encompass many of its ideas of being person-centered and evidence-based. Emotion-focused exposure for patients with disabling back pain and distress, for example, has shown to be significantly better than an I-CBT pain rehabilitation program [52]. Further, the RESTORE trial based on cognitive functional therapy showed sustained improvements superior to usual care in primary care settings for people with disabling low back pain [50]. Both trials employ procedures to ensure empathetic communication, making sense of pain, development of personalized goals, as well as evidence-based treatments to overcome distress and avoidance, e.g., exposure. Importantly, both trials provided training to enhance competencies to provide such treatments.

When integrating treatment programs in the clinic, we suggest utilizing SCEDs. These offer a clinically relevant way of evaluating outcomes continually and provide valuable information for engaging the patient [68]. Exposure, for example, was evaluated early-on using single-subject methodology [69,70], which led to the further development of the intervention [47,71]. Emotion-focused exposure was also developed with this design [53]. Generalization is tested by replication with further SCED studies, and data from multiple SCEDs can be aggregated and meta-analytic techniques provide information about effectiveness on the group level [52]. A particular feature of SCED is repeated measurement, often using diaries. This allows for vital feedback and communication with the patient during the treatment. It also permits testing our hypotheses about important variables, e.g., the order of change during treatment. An illustration is a SCED study focusing on how improvements unfold in people with disabling low back pain undergoing cognitive functional therapy [72]. The pattern of change was unique to the individual and suspected mediators (fear and pain control) were associated with levels of pain disability. Importantly these changed concomitantly and not before pain and disability improved. There are challenges with SCEDs in the clinic, as it may not always be feasible to have long baseline periods. Still, SCEDs are incredibly flexible and being developed to provide reliable and valid results in both clinical and research settings [62,68,73,74].

6 Conclusion

We content that to improve the care of patients suffering disabling pain, training pain clinicians in core skills, where treatment is tailored to the patient’s individual needs, is required. This approach should increase patients’ understanding of the nature of the problem, participation in the choice of treatment methods, adherence, satisfaction, and ultimately outcomes, e.g., function and the experience of the pain itself. Patient-centered outcome measures allow for monitoring and adaptation of care.

-

Research ethics and informed consent: This paper is exempt from ethical approval as no participants were recruited, nor was any data analyzed.

-

Author contributions: Each author has worked actively in the conception, writing, and editing of this paper. All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire paper and approved its submission.

-

Competing interests: The authors have no direct conflicts of interest with this paper. To be transparent, the authors declare the following: Steven J. Linton: received an educational honorarium from Haleon, Peter B. O’Sullivan: received speaking fees and grants concerning psychologically informed care, Hedvig E. Zetterberg: None, Johan W.S. Vlaeyen: supported by the research program “From Acute Aversive Sensations to Chronic Bodily Symptoms,” a long-term structural Methusalem funding (METH/15/011) by the Flemish government, Belgium, and by the NWO gravitation program “New Science of Mental Disorders”: www.nsmd.eu (grant number 024.004.016) by the Dutch Research Council, Netherlands. Steven Linton and Johan Vlaeyen are editors of Scandinavian Journal of Pain (Psychology of Pain and Pain Management).

-

Research funding: None declared.

-

Data availability: Not applicable.

-

Artificial intelligence/Machine learning tools: Not applicable.

References

[1] Simpson P, Holopainen R, Schütze R, O’Sullivan P, Smith A, Linton SJ, et al. Training of physical therapists to deliver individualized biopsychosocial interventions to treat musculoskeletal pain conditions: a scoping review. Phys Ther. 2021 Oct;101(10):pzab188. 10.1093/ptj/pzab188.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[2] Henrich D, Glombiewski JA, Scholten S. Systematic review of training in cognitive-behavioral therapy: Summarizing effects, costs and techniques. Clin Psychol Rev. 2023 Apr;101:102266. 10.1016/j.cpr.2023.102266.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[3] Lin I, Wiles L, Waller R, Caneiro J, Nagree Y, Straker L, et al. Patient-centred care: the cornerstone for high-value musculoskeletal pain management. Br J Sports Med. 2020 Nov;54(21):1240–2. 10.1136/bjsports-2019-101918.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[4] Slater H, Jordan JE, O’Sullivan PB, Schütze R, Goucke R, Chua J, et al. “Listen to me, learn from me”: a priority setting partnership for shaping interdisciplinary pain training to strengthen chronic pain care. Pain. 2022 Nov;163(11):e1145–63. 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000002647.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[5] Blyth FM, Macfarlane GJ, Nicholas MK. The contribution of psychosocial factors to the development of chronic pain: The key to better outcomes for patients. Pain. 2007 May;129(1):8–11. 10.1016/j.pain.2007.03.009.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] Linton SJ, Flink IK, Vlaeyen JWS. Understanding the etiology of chronic pain from a psychological perspective. Phys Ther. 2018 May;98(5):315–24. 10.1093/ptj/pzy027.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[7] Main CJ, Keefe FJ, Jensen MP, Vlaeyen JWS, Vowles KE, Fordyce WE, et al. Fordyce’s behavioral methods for chronic pain and illness: republished with invited commentaries. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health; 2014.Suche in Google Scholar

[8] Turk DC, Gatchel RJ, editors. Psychological approaches to pain management: a practitioner’s handbook. 3rd edn. New York: The Guilford Press; 2018.Suche in Google Scholar

[9] Vlaeyen JWS, Maher CG, Wiech K, Van Zundert J, Meloto CB, Diatchenko L, et al. Low back pain. Nat Rev Dis Primer. 2018 Dec;4(1):52. 10.1038/s41572-018-0052-1.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[10] Nicholas MK. The biopsychosocial model of pain 40 years on: time for a reappraisal? Pain. 2022 Nov;163(S1):S3–14. 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000002654.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] Dekker J, Sears SF, Åsenlöf P, Berry K. Psychologically informed health care. Transl Behav Med. 2023 May;13(5):289–96. 10.1093/tbm/ibac105.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[12] Fullen B, Morlion B, Linton SJ, Roomes D, van Griensven J, Abraham L, et al. Management of chronic low back pain and the impact on patients’ personal and professional lives: Results from an international patient survey. Pain Pract. 2022 Apr;22(4):463–77. 10.1111/papr.13103.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[13] Rasu RS, Sohraby R, Cunningham L, Knell ME. Assessing chronic pain treatment practices and evaluating adherence to chronic pain clinical guidelines in outpatient practices in the United States. J Pain. 2013 Jun;14(6):568–78. 10.1016/j.jpain.2013.01.425.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[14] Bunzli S, Smith A, Schütze R, Lin I, O’Sullivan P. Making sense of low back pain and pain-related fear. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2017 Sep;47(9):628–36. 10.2519/jospt.2017.7434.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[15] Bier JD, Sandee-Geurts JJW, Ostelo RWJG, Koes BW, Verhagen AP. Can primary care for back and/or neck pain in the Netherlands benefit from stratification for risk groups according to the start back tool classification? Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2018 Jan;99(1):65–71. 10.1016/j.apmr.2017.06.011.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[16] Cherkin D, Balderson B, Wellman R, Hsu C, Sherman KJ, Evers SC, et al. Effect of low back pain risk-stratification strategy on patient outcomes and care processes: the MATCH randomized trial in primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2018 Aug;33(8):1324–36. 10.1007/s11606-018-4468-9.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[17] Denneny D, Frijdal (nee Klapper) A, Bianchi-Berthouze N, Greenwood J, McLoughlin R, Petersen K, et al. The application of psychologically informed practice: observations of experienced physiotherapists working with people with chronic pain. Physiotherapy. 2020 Mar;106:163–73. 10.1016/j.physio.2019.01.014.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[18] McDaniel SH, Grus CL, Cubic BA, Hunter CL, Kearney LK, Schuman CC, et al. Competencies for psychology practice in primary care. Am Psychol. 2014 May;69(4):409–29. 10.1037/a0036072.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[19] McCracken LM. Personalized pain management: Is it time for process‐based therapy for particular people with chronic pain? Eur J Pain. 2023;27:1044–55. 10.1002/ejp.2091.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[20] Williams AC, de C, Fisher E, Hearn L, Eccleston C. Psychological therapies for the management of chronic pain (excluding headache) in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012 Nov;11(11):CD007407. 10.1002/14651858.CD007407.pub4.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[21] Delitto A, Patterson CG, Stevans JM, Freburger JK, Khoja SS, Schneider MJ, et al. Stratified care to prevent chronic low back pain in high-risk patients: The TARGET trial. A multi-site pragmatic cluster randomized trial. EClinicalMedicine. 2021 Apr;34:100795. 10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.100795.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[22] Hill JC, Garvin S, Bromley K, Saunders B, Kigozi J, Cooper V, et al. Risk-based stratified primary care for common musculoskeletal pain presentations (STarT MSK): a cluster-randomised, controlled trial. Lancet Rheumatol. 2022 Sep;4(9):e591–602. 10.1016/S2665-9913(22)00159-X.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[23] Morsø L, Olsen Rose K, Schiøttz‐Christensen B, Sowden G, Søndergaard J, Christiansen DH. Effectiveness of stratified treatment for back pain in Danish primary care: A randomized controlled trial. Eur J Pain. 2021 Oct;25(9):2020–38. 10.1002/ejp.1818.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[24] Vlaeyen JWS, Morley S. Cognitive-behavioral treatments for chronic pain: What Works for Whom? Clin J Pain. 2005 Jan;21(1):1–8. 10.1097/00002508-200501000-00001.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[25] Cowell I, McGregor A, O’Sullivan P, O’Sullivan K, Poyton R, Murtagh G. Physiotherapists’ perceptions on using a multidimensional clinical reasoning form during psychologically informed training for low back pain. Musculoskelet Sci Pract. 2023 Aug;66:102797. 10.1016/j.msksp.2023.102797.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[26] Pincus T, Noel M, Jordan A, Serbic D. Perceived diagnostic uncertainty in pediatric chronic pain. Pain. 2018 Jul;159(7):1198–201. 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001180.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[27] Neville A, Jordan A, Beveridge JK, Pincus T, Noel M. Diagnostic Uncertainty in Youth With Chronic Pain and Their Parents. J Pain. 2019 Sep;20(9):1080–90. 10.1016/j.jpain.2019.03.004.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[28] Chou L, Ranger TA, Peiris W, Cicuttini FM, Urquhart DM, Sullivan K, et al. Patients’ perceived needs for medical services for non-specific low back pain: A systematic scoping review. Laws MB, editor. Plos One. 2018 Nov. 13(11):e0204885. 10.1371/journal.pone.0204885.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[29] Maher C, Underwood M, Buchbinder R. Non-specific low back pain. Lancet. 2017 Feb;389(10070):736–47. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30970-9.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[30] Bunzli S, Smith A, Schütze R, O’Sullivan P. Beliefs underlying pain-related fear and how they evolve: a qualitative investigation in people with chronic back pain and high pain-related fear. BMJ Open. 2015 Oct;5(10):e008847. 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008847.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[31] Holopainen R, Piirainen A, Heinonen A, Karppinen J, O’Sullivan P. From “Non‐encounters” to autonomic agency. Conceptions of patients with low back pain about their encounters in the health care system. Musculoskelet Care. 2018 Jun;16(2):269–77. 10.1002/msc.1230.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[32] Hopayian K, Notley C. A systematic review of low back pain and sciatica patients’ expectations and experiences of health care. Spine J. 2014 Aug;14(8):1769–80. 10.1016/j.spinee.2014.02.029.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[33] Chi-Lun-Chiao A, Chehata M, Broeker K, Gates B, Ledbetter L, Cook C, et al. Patients’ perceptions with musculoskeletal disorders regarding their experience with healthcare providers and health services: an overview of reviews. Arch Physiother. 2020 Dec;10(1):17. 10.1186/s40945-020-00088-6.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[34] Toye F, Belton J, Hannink E, Seers K, Barker K. A healing journey with chronic pain: a meta-ethnography synthesizing 195 qualitative studies. Pain Med. 2021 Jun;22(6):1333–44. 10.1093/pm/pnaa373.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[35] Vlaeyen JWS, Crombez G, Linton SJ. The fear-avoidance model of pain. Pain. 2016 Aug;157(8):1588–9. 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000574.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[36] Cohen SP, Vase L, Hooten WM. Chronic pain: an update on burden, best practices, and new advances. Lancet. 2021 May;397(10289):2082–97. 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00393-7.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[37] Gatchel RJ, Peng YB, Peters ML, Fuchs PN, Turk DC. The biopsychosocial approach to chronic pain: Scientific advances and future directions. Psychol Bull. 2007;133(4):581–624. 10.1037/0033-2909.133.4.581.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[38] Kosek E, Cohen M, Baron R, Gebhart GF, Mico JA, Rice ASC, et al. Do we need a third mechanistic descriptor for chronic pain states? Pain. 2016 Jul;157(7):1382–6. 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000507.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[39] Voscopoulos C, Lema M. When does acute pain become chronic? Br J Anaesth. 2010 Dec;105:i69–85. 10.1093/bja/aeq323.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[40] Edwards RR, Dworkin RH, Sullivan MD, Turk DC, Wasan AD. The role of psychosocial processes in the development and maintenance of chronic pain. J Pain. 2016 Sep;17(9):T70–92. 10.1016/j.jpain.2016.01.001.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[41] Lee H, Hübscher M, Moseley GL, Kamper SJ, Traeger AC, Mansell G, et al. How does pain lead to disability? A systematic review and meta-analysis of mediation studies in people with back and neck pain. Pain. 2015 Jun;156(6):988–97. 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000146.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[42] Nicholas MK, Linton SJ, Watson PJ, Main CJ. Early identification and management of psychological risk factors (“Yellow Flags”) in patients with low back pain: a reappraisal. Phys Ther. 2011 May;91(5):737–53. 10.2522/ptj.20100224.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[43] Wertli MM, Rasmussen-Barr E, Weiser S, Bachmann LM, Brunner F. The role of fear avoidance beliefs as a prognostic factor for outcome in patients with nonspecific low back pain: a systematic review. Spine J. 2014 May;14(5):816–36.e4. 10.1016/j.spinee.2013.09.036.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[44] Martinez-Calderon J, Flores-Cortes M, Morales-Asencio JM, Luque-Suarez A. Pain-related fear, pain intensity and function in individuals with chronic musculoskeletal pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pain. 2019 Dec;20(12):1394–415. 10.1016/j.jpain.2019.04.009.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[45] Crombez G, Eccleston C, Van Damme S, Vlaeyen JWS, Karoly P. Fear-avoidance model of chronic pain: the next generation. Clin J Pain. 2012 Jul;28(6):475–83. 10.1097/AJP.0b013e3182385392.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[46] den Hollander M, Goossens M, de Jong J, Ruijgrok J, Oosterhof J, Onghena P, et al. Expose or protect? A randomized controlled trial of exposure in vivo vs pain-contingent treatment as usual in patients with complex regional pain syndrome type 1. Pain. 2016 Oct;157(10):2318–29. 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000651.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[47] Glombiewski JA, Holzapfel S, Riecke J, Vlaeyen JWS, de Jong J, Lemmer G, et al. Exposure and CBT for chronic back pain: An RCT on differential efficacy and optimal length of treatment. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2018 Jun;86(6):533–45. 10.1037/ccp0000298.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[48] Linton SJ, Boersma K, Jansson M, Overmeer T, Lindblom K, Vlaeyen JWS. A randomized controlled trial of exposure in vivo for patients with spinal pain reporting fear of work-related activities. Eur J Pain. 2008 Aug;12(6):722–30. 10.1016/j.ejpain.2007.11.001.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[49] Simons LE, Vlaeyen JWS, Declercq L, Smith AM, Beebe J, Hogan M, et al. Avoid or engage? Outcomes of graded exposure in youth with chronic pain using a sequential replicated single-case randomized design. Pain. 2020 Mar;161(3):520–31. 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001735.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[50] Kent P, Haines T, O’Sullivan P, Smith A, Campbell A, Schutze R, et al. Cognitive functional therapy with or without movement sensor biofeedback versus usual care for chronic, disabling low back pain (RESTORE): a randomised, controlled, three-arm, parallel group, phase 3, clinical trial. Lancet. 2023 Jun;401(10391):1866–77. 10.1016/S0140-6736(23)00441-5.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[51] O’Sullivan PB, Caneiro JP, O’Keeffe M, Smith A, Dankaerts W, Fersum K, et al. Cognitive Functional therapy: an integrated behavioral approach for the targeted management of disabling low back pain. Phys Ther. 2018 May;98(5):408–23. 10.1093/ptj/pzy022.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[52] Boersma K, Södermark M, Hesser H, Flink IK, Gerdle B, Linton SJ. Efficacy of a transdiagnostic emotion–focused exposure treatment for chronic pain patients with comorbid anxiety and depression: a randomized controlled trial. Pain. 2019 Aug;160(8):1708–18. 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001575.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[53] Linton SJ, Fruzzetti AE. A hybrid emotion-focused exposure treatment for chronic pain: A feasibility study. Scand J Pain. 2014 Jul 1;5(3):151–8. 10.1016/j.sjpain.2014.05.008.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[54] Mansell G, Kamper SJ, Kent P. Why and how back pain interventions work: What can we do to find out. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2013 Oct;27(5):685–97. 10.1016/j.berh.2013.10.001.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[55] Murillo C, Vo TT, Vansteelandt S, Harrison LE, Cagnie B, Coppieters I, et al. How do psychologically based interventions for chronic musculoskeletal pain work? A systematic review and meta-analysis of specific moderators and mediators of treatment. Clin Psychol Rev. 2022 Jun;94:102160. 10.1016/j.cpr.2022.102160.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[56] Södermark M, Linton SJ, Hesser H, Flink I, Gerdle B, Boersma K. What Works? processes of change in a transdiagnostic exposure treatment for patients with chronic pain and emotional problems. Clin J Pain. 2020 Sep;36(9):648–57. 10.1097/AJP.0000000000000851.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[57] Linton SJ. A transdiagnostic approach to pain and emotion. J Appl Biobehav Res. 2013 Jun;18(2):82–103. 10.1111/jabr.12007.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[58] Sharp TJ, Harvey AG. Chronic pain and posttraumatic stress disorder: mutual maintenance? Clin Psychol Rev. 2001 Aug;21(6):857–77. 10.1016/S0272-7358(00)00071-4.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[59] Roth AD, Pilling S. Using an evidence-based methodology to identify the competences required to deliver effective cognitive and behavioural therapy for depression and anxiety disorders. Behav Cogn Psychother. 2008 Mar;36(2):129–47. 10.1017/S1352465808004141.Suche in Google Scholar

[60] Sullivan MJL, Bishop SR, Pivik J. The pain catastrophizing scale: development and validation. Psychol Assess. 1995;7(4):524–32. 10.1037/1040-3590.7.4.524.Suche in Google Scholar

[61] Reneman MF, Jorritsma W, Schellekens JMH, Göeken LNH. Concurrent validity of questionnaire and performance-based disability measurements in patients with chronic nonspecific low back pain. J Occup Rehabil. 2002;12(3):119–29. 10.1023/A:1016834409773.Suche in Google Scholar

[62] Morley S, Masterson C, Main CJ. Single-case methods in clinical psychology: a practical guide. Abingdon, Oxon; New York, NY: Routledge; 2018.10.4324/9781315412931Suche in Google Scholar

[63] Haynes SN, O’Brien WH. Functional analysis in behavior therapy. Clin Psychol Rev. 1990 Jan;10(6):649–68. 10.1016/0272-7358(90)90074-K.Suche in Google Scholar

[64] Onghena P, Edgington ES. Customization of pain treatments: single-case design and analysis. Clin J Pain. 2005 Jan;21(1):56–68. 10.1097/00002508-200501000-00007.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[65] Vlaeyen JWS, Onghena P, Vannest KJ, Kratochwill TR. 3.01 – single-case experimental designs: clinical research and practice. In: Asmundson GJG, editor. Comprehensive Clinical Psychology. 2nd edn. Oxford: Elsevier; 2022. p. 1–28.10.1016/B978-0-12-818697-8.00191-6Suche in Google Scholar

[66] Bulté I, Onghena P. When the truth hits you between the eyes: a software tool for the visual analysis of single-case experimental data. Methodology. 2012 Aug;8(3):104–14. 10.1027/1614-2241/a000042.Suche in Google Scholar

[67] Michiels B, Onghena P. Randomized single-case AB phase designs: Prospects and pitfalls. Behav Res Methods. 2019 Dec;51(6):2454–76. 10.3758/s13428-018-1084-x.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[68] Scholten S, Schemer L, Herzog P, Haas JW, Heider J, Winter D, et al. Leveraging single-case experimental designs to promote personalized psychological treatment: Step-by-step implementation protocol with stakeholder involvement for a single-case outpatient clinic [Internet]. OSF Preprint. 2023;1–23. 10.31219/osf.io/uaznr.Suche in Google Scholar

[69] Boersma K, Linton S, Overmeer T, Jansson M, Vlaeyen J, de Jong J. Lowering fear-avoidance and enhancing function through exposure in vivo: A multiple baseline study across six patients with back pain. Pain. 2004 Mar;108(1):8–16. 10.1016/j.pain.2003.03.001.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[70] Vlaeyen JWS, de Jong J, Geilen M, Heuts PHTG, van Breukelen G. Graded exposure in vivo in the treatment of pain-related fear: a replicated single-case experimental design in four patients with chronic low back pain. Behav Res Ther. 2001 Feb;39(2):151–66. 10.1016/S0005-7967(99)00174-6.Suche in Google Scholar

[71] Hollander M, den, de Jong J, Onghena P, Vlaeyen JWS. Generalization of exposure in vivo in complex regional pain syndrome type I. Behav Res Ther. 2020 Jan;124:103511. 10.1016/j.brat.2019.103511.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[72] Caneiro JP, Smith A, Linton SJ, Moseley GL, O’Sullivan P. How does change unfold? an evaluation of the process of change in four people with chronic low back pain and high pain-related fear managed with Cognitive Functional Therapy: A replicated single-case experimental design study. Behav Res Ther. 2019 Jun;117:28–39. 10.1016/j.brat.2019.02.007.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[73] Lavefjord A, Sundström FTA, Buhrman M, McCracken LM. Assessment methods in single case design studies of psychological treatments for chronic pain: A scoping review. J Context Behav Sci. 2021 Jul;21:121–35. 10.1016/j.jcbs.2021.05.005.Suche in Google Scholar

[74] Shaffer JA, Kronish IM, Falzon L, Cheung YK, Davidson KW. N-of-1 Randomized intervention trials in health psychology: a systematic review and methodology critique. Ann Behav Med. 2018 Aug 16;52(9):731–42. 10.1093/abm/kax026.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Editorial Comment

- From pain to relief: Exploring the consistency of exercise-induced hypoalgesia

- Christmas greetings 2024 from the Editor-in-Chief

- Original Articles

- The Scandinavian Society for the Study of Pain 2022 Postgraduate Course and Annual Scientific (SASP 2022) Meeting 12th to 14th October at Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen

- Comparison of ultrasound-guided continuous erector spinae plane block versus continuous paravertebral block for postoperative analgesia in patients undergoing proximal femur surgeries

- Clinical Pain Researches

- The effect of tourniquet use on postoperative opioid consumption after ankle fracture surgery – a retrospective cohort study

- Changes in pain, daily occupations, lifestyle, and health following an occupational therapy lifestyle intervention: a secondary analysis from a feasibility study in patients with chronic high-impact pain

- Tonic cuff pressure pain sensitivity in chronic pain patients and its relation to self-reported physical activity

- Reliability, construct validity, and factorial structure of a Swedish version of the medical outcomes study social support survey (MOS-SSS) in patients with chronic pain

- Hurdles and potentials when implementing internet-delivered Acceptance and commitment therapy for chronic pain: a retrospective appraisal using the Quality implementation framework

- Exploring the outcome “days with bothersome pain” and its association with pain intensity, disability, and quality of life

- Fatigue and cognitive fatigability in patients with chronic pain

- The Swedish version of the pain self-efficacy questionnaire short form, PSEQ-2SV: Cultural adaptation and psychometric evaluation in a population of patients with musculoskeletal disorders

- Pain coping and catastrophizing in youth with and without cerebral palsy

- Neuropathic pain after surgery – A clinical validation study and assessment of accuracy measures of the 5-item NeuPPS scale

- Translation, contextual adaptation, and reliability of the Danish Concept of Pain Inventory (COPI-Adult (DK)) – A self-reported outcome measure

- Cosmetic surgery and associated chronic postsurgical pain: A cross-sectional study from Norway

- The association of hemodynamic parameters and clinical demographic variables with acute postoperative pain in female oncological breast surgery patients: A retrospective cohort study

- Healthcare professionals’ experiences of interdisciplinary collaboration in pain centres – A qualitative study

- Effects of deep brain stimulation and verbal suggestions on pain in Parkinson’s disease

- Painful differences between different pain scale assessments: The outcome of assessed pain is a matter of the choices of scale and statistics

- Prevalence and characteristics of fibromyalgia according to three fibromyalgia diagnostic criteria: A secondary analysis study

- Sex moderates the association between quantitative sensory testing and acute and chronic pain after total knee/hip arthroplasty

- Tramadol-paracetamol for postoperative pain after spine surgery – A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study

- Cancer-related pain experienced in daily life is difficult to communicate and to manage – for patients and for professionals

- Making sense of pain in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD): A qualitative study

- Patient-reported pain, satisfaction, adverse effects, and deviations from ambulatory surgery pain medication

- Does pain influence cognitive performance in patients with mild traumatic brain injury?

- Hypocapnia in women with fibromyalgia

- Application of ultrasound-guided thoracic paravertebral block or intercostal nerve block for acute herpes zoster and prevention of post-herpetic neuralgia: A case–control retrospective trial

- Translation and examination of construct validity of the Danish version of the Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia

- A positive scratch collapse test in anterior cutaneous nerve entrapment syndrome indicates its neuropathic character

- ADHD-pain: Characteristics of chronic pain and association with muscular dysregulation in adults with ADHD

- The relationship between changes in pain intensity and functional disability in persistent disabling low back pain during a course of cognitive functional therapy

- Intrathecal pain treatment for severe pain in patients with terminal cancer: A retrospective analysis of treatment-related complications and side effects

- Psychometric evaluation of the Danish version of the Pain Self-Efficacy Questionnaire in patients with subacute and chronic low back pain

- Dimensionality, reliability, and validity of the Finnish version of the pain catastrophizing scale in chronic low back pain

- To speak or not to speak? A secondary data analysis to further explore the context-insensitive avoidance scale

- Pain catastrophizing levels differentiate between common diseases with pain: HIV, fibromyalgia, complex regional pain syndrome, and breast cancer survivors

- Prevalence of substance use disorder diagnoses in patients with chronic pain receiving reimbursed opioids: An epidemiological study of four Norwegian health registries

- Pain perception while listening to thrash heavy metal vs relaxing music at a heavy metal festival – the CoPainHell study – a factorial randomized non-blinded crossover trial

- Observational Studies

- Cutaneous nerve biopsy in patients with symptoms of small fiber neuropathy: a retrospective study

- The incidence of post cholecystectomy pain (PCP) syndrome at 12 months following laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a prospective evaluation in 200 patients

- Associations between psychological flexibility and daily functioning in endometriosis-related pain

- Relationship between perfectionism, overactivity, pain severity, and pain interference in individuals with chronic pain: A cross-lagged panel model analysis

- Access to psychological treatment for chronic cancer-related pain in Sweden

- Validation of the Danish version of the knowledge and attitudes survey regarding pain

- Associations between cognitive test scores and pain tolerance: The Tromsø study

- Healthcare experiences of fibromyalgia patients and their associations with satisfaction and pain relief. A patient survey

- Video interpretation in a medical spine clinic: A descriptive study of a diverse population and intervention

- Role of history of traumatic life experiences in current psychosomatic manifestations

- Social determinants of health in adults with whiplash associated disorders

- Which patients with chronic low back pain respond favorably to multidisciplinary rehabilitation? A secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial

- A preliminary examination of the effects of childhood abuse and resilience on pain and physical functioning in patients with knee osteoarthritis

- Differences in risk factors for flare-ups in patients with lumbar radicular pain may depend on the definition of flare

- Real-world evidence evaluation on consumer experience and prescription journey of diclofenac gel in Sweden

- Patient characteristics in relation to opioid exposure in a chronic non-cancer pain population

- Topical Reviews

- Bridging the translational gap: adenosine as a modulator of neuropathic pain in preclinical models and humans

- What do we know about Indigenous Peoples with low back pain around the world? A topical review

- The “future” pain clinician: Competencies needed to provide psychologically informed care

- Systematic Reviews

- Pain management for persistent pain post radiotherapy in head and neck cancers: systematic review

- High-frequency, high-intensity transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation compared with opioids for pain relief after gynecological surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis

- Reliability and measurement error of exercise-induced hypoalgesia in pain-free adults and adults with musculoskeletal pain: A systematic review

- Noninvasive transcranial brain stimulation in central post-stroke pain: A systematic review

- Short Communications

- Are we missing the opioid consumption in low- and middle-income countries?

- Association between self-reported pain severity and characteristics of United States adults (age ≥50 years) who used opioids

- Could generative artificial intelligence replace fieldwork in pain research?

- Skin conductance algesimeter is unreliable during sudden perioperative temperature increases

- Original Experimental

- Confirmatory study of the usefulness of quantum molecular resonance and microdissectomy for the treatment of lumbar radiculopathy in a prospective cohort at 6 months follow-up

- Pain catastrophizing in the elderly: An experimental pain study

- Improving general practice management of patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain: Interdisciplinarity, coherence, and concerns

- Concurrent validity of dynamic bedside quantitative sensory testing paradigms in breast cancer survivors with persistent pain

- Transcranial direct current stimulation is more effective than pregabalin in controlling nociceptive and anxiety-like behaviors in a rat fibromyalgia-like model

- Paradox pain sensitivity using cuff pressure or algometer testing in patients with hemophilia

- Physical activity with person-centered guidance supported by a digital platform or with telephone follow-up for persons with chronic widespread pain: Health economic considerations along a randomized controlled trial

- Measuring pain intensity through physical interaction in an experimental model of cold-induced pain: A method comparison study

- Pharmacological treatment of pain in Swedish nursing homes: Prevalence and associations with cognitive impairment and depressive mood

- Neck and shoulder pain and inflammatory biomarkers in plasma among forklift truck operators – A case–control study

- The effect of social exclusion on pain perception and heart rate variability in healthy controls and somatoform pain patients

- Revisiting opioid toxicity: Cellular effects of six commonly used opioids

- Letter to the Editor

- Post cholecystectomy pain syndrome: Letter to Editor

- Response to the Letter by Prof Bordoni

- Response – Reliability and measurement error of exercise-induced hypoalgesia

- Is the skin conductance algesimeter index influenced by temperature?

- Skin conductance algesimeter is unreliable during sudden perioperative temperature increase

- Corrigendum

- Corrigendum to “Chronic post-thoracotomy pain after lung cancer surgery: a prospective study of preoperative risk factors”

- Obituary

- A Significant Voice in Pain Research Björn Gerdle in Memoriam (1953–2024)

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Editorial Comment

- From pain to relief: Exploring the consistency of exercise-induced hypoalgesia

- Christmas greetings 2024 from the Editor-in-Chief

- Original Articles

- The Scandinavian Society for the Study of Pain 2022 Postgraduate Course and Annual Scientific (SASP 2022) Meeting 12th to 14th October at Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen

- Comparison of ultrasound-guided continuous erector spinae plane block versus continuous paravertebral block for postoperative analgesia in patients undergoing proximal femur surgeries

- Clinical Pain Researches

- The effect of tourniquet use on postoperative opioid consumption after ankle fracture surgery – a retrospective cohort study

- Changes in pain, daily occupations, lifestyle, and health following an occupational therapy lifestyle intervention: a secondary analysis from a feasibility study in patients with chronic high-impact pain

- Tonic cuff pressure pain sensitivity in chronic pain patients and its relation to self-reported physical activity

- Reliability, construct validity, and factorial structure of a Swedish version of the medical outcomes study social support survey (MOS-SSS) in patients with chronic pain

- Hurdles and potentials when implementing internet-delivered Acceptance and commitment therapy for chronic pain: a retrospective appraisal using the Quality implementation framework

- Exploring the outcome “days with bothersome pain” and its association with pain intensity, disability, and quality of life

- Fatigue and cognitive fatigability in patients with chronic pain

- The Swedish version of the pain self-efficacy questionnaire short form, PSEQ-2SV: Cultural adaptation and psychometric evaluation in a population of patients with musculoskeletal disorders

- Pain coping and catastrophizing in youth with and without cerebral palsy

- Neuropathic pain after surgery – A clinical validation study and assessment of accuracy measures of the 5-item NeuPPS scale

- Translation, contextual adaptation, and reliability of the Danish Concept of Pain Inventory (COPI-Adult (DK)) – A self-reported outcome measure

- Cosmetic surgery and associated chronic postsurgical pain: A cross-sectional study from Norway

- The association of hemodynamic parameters and clinical demographic variables with acute postoperative pain in female oncological breast surgery patients: A retrospective cohort study

- Healthcare professionals’ experiences of interdisciplinary collaboration in pain centres – A qualitative study

- Effects of deep brain stimulation and verbal suggestions on pain in Parkinson’s disease

- Painful differences between different pain scale assessments: The outcome of assessed pain is a matter of the choices of scale and statistics

- Prevalence and characteristics of fibromyalgia according to three fibromyalgia diagnostic criteria: A secondary analysis study

- Sex moderates the association between quantitative sensory testing and acute and chronic pain after total knee/hip arthroplasty

- Tramadol-paracetamol for postoperative pain after spine surgery – A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study

- Cancer-related pain experienced in daily life is difficult to communicate and to manage – for patients and for professionals

- Making sense of pain in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD): A qualitative study

- Patient-reported pain, satisfaction, adverse effects, and deviations from ambulatory surgery pain medication

- Does pain influence cognitive performance in patients with mild traumatic brain injury?

- Hypocapnia in women with fibromyalgia

- Application of ultrasound-guided thoracic paravertebral block or intercostal nerve block for acute herpes zoster and prevention of post-herpetic neuralgia: A case–control retrospective trial

- Translation and examination of construct validity of the Danish version of the Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia

- A positive scratch collapse test in anterior cutaneous nerve entrapment syndrome indicates its neuropathic character

- ADHD-pain: Characteristics of chronic pain and association with muscular dysregulation in adults with ADHD

- The relationship between changes in pain intensity and functional disability in persistent disabling low back pain during a course of cognitive functional therapy

- Intrathecal pain treatment for severe pain in patients with terminal cancer: A retrospective analysis of treatment-related complications and side effects

- Psychometric evaluation of the Danish version of the Pain Self-Efficacy Questionnaire in patients with subacute and chronic low back pain

- Dimensionality, reliability, and validity of the Finnish version of the pain catastrophizing scale in chronic low back pain

- To speak or not to speak? A secondary data analysis to further explore the context-insensitive avoidance scale

- Pain catastrophizing levels differentiate between common diseases with pain: HIV, fibromyalgia, complex regional pain syndrome, and breast cancer survivors

- Prevalence of substance use disorder diagnoses in patients with chronic pain receiving reimbursed opioids: An epidemiological study of four Norwegian health registries

- Pain perception while listening to thrash heavy metal vs relaxing music at a heavy metal festival – the CoPainHell study – a factorial randomized non-blinded crossover trial

- Observational Studies

- Cutaneous nerve biopsy in patients with symptoms of small fiber neuropathy: a retrospective study

- The incidence of post cholecystectomy pain (PCP) syndrome at 12 months following laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a prospective evaluation in 200 patients

- Associations between psychological flexibility and daily functioning in endometriosis-related pain

- Relationship between perfectionism, overactivity, pain severity, and pain interference in individuals with chronic pain: A cross-lagged panel model analysis

- Access to psychological treatment for chronic cancer-related pain in Sweden

- Validation of the Danish version of the knowledge and attitudes survey regarding pain

- Associations between cognitive test scores and pain tolerance: The Tromsø study

- Healthcare experiences of fibromyalgia patients and their associations with satisfaction and pain relief. A patient survey

- Video interpretation in a medical spine clinic: A descriptive study of a diverse population and intervention

- Role of history of traumatic life experiences in current psychosomatic manifestations

- Social determinants of health in adults with whiplash associated disorders

- Which patients with chronic low back pain respond favorably to multidisciplinary rehabilitation? A secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial

- A preliminary examination of the effects of childhood abuse and resilience on pain and physical functioning in patients with knee osteoarthritis

- Differences in risk factors for flare-ups in patients with lumbar radicular pain may depend on the definition of flare

- Real-world evidence evaluation on consumer experience and prescription journey of diclofenac gel in Sweden

- Patient characteristics in relation to opioid exposure in a chronic non-cancer pain population

- Topical Reviews

- Bridging the translational gap: adenosine as a modulator of neuropathic pain in preclinical models and humans

- What do we know about Indigenous Peoples with low back pain around the world? A topical review

- The “future” pain clinician: Competencies needed to provide psychologically informed care

- Systematic Reviews

- Pain management for persistent pain post radiotherapy in head and neck cancers: systematic review

- High-frequency, high-intensity transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation compared with opioids for pain relief after gynecological surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis

- Reliability and measurement error of exercise-induced hypoalgesia in pain-free adults and adults with musculoskeletal pain: A systematic review