Abstract

Objectives

Chronic abdominal pain is occasionally caused by an abdominal wall entity such as anterior cutaneous nerve entrapment syndrome (ACNES). This syndrome is thought to occur due to intercostal nerve branches (T7–12) that are entrapped in the rectus abdominis muscles. The diagnosis is largely based on subjective clues in patient history and physical examination. A test referred to as the scratch collapse test (SCT) is used as an additional diagnostic tool in peripheral nerve entrapment syndromes such as the carpal tunnel syndrome. The aim of the present study is to investigate whether an SCT was positive in patients with suspected ACNES. If so, this finding may support its hypothesized neuropathic character.

Methods

A prospective, case–control study was performed among patients with ACNES (n = 20) and two control groups without ACNES (acute intra-abdominal pathology n = 20; healthy n = 20), all were consecutively included. ACNES was diagnosed based on previously published criteria. The SCT test was executed at the painful abdominal area in both patient groups and at a corresponding area in healthy controls. Predictive values, sensitivity, and specificity were calculated. Videos of tests were evaluated by blinded observers.

Results

SCT was judged positive in 19 of 20 ACNES patients but not in any of the 40 controls. A 95% sensitivity (confidence interval [CI]: 75–99) and optimal specificity (100%; CI: 83–100) were calculated.

Conclusions

The positive SCT supports the hypothesis that ACNES is an entrapment neuropathy. A positive SCT should be considered a major diagnostic criterion for ACNES.

1 Introduction

Chronic abdominal pain is occasionally caused by an abdominal wall entity such as anterior cutaneous nerve entrapment syndrome (ACNES) [1,2]. In 1926, Carnett was the first to identify intercostal neuralgia as a cause of severe neuropathic abdominal pain [3]. Applegate coined the acronym ACNES [1,4]. ACNES is hypothesized to be due to entrapped terminal branches of the lower thoracic intercostal nerves (T7–12) at the level of the rectus abdominis muscle [1,5]. Over the past two decades, knowledge regarding this condition has increased [6,7]. ACNES is characterized by a debilitating sharp pain at a predictable spot in the abdominal area. The pain is often intensified during a change in body position or exercise as abdominal musculature is challenged. At physical examination, a small area of intense anterior abdominal pain is indicated by the patient. Altered skin sensations such as hypoesthesia, hyperesthesia, and changed cool perception are often present. Pinching the skin overlying the painful spot may be exceedingly painful. A positive Carnett sign is indicated by the presence of increased pain when simultaneously tensing the rectus abdominis muscle and palpating the painful area. However, all of these symptoms and signs are rather subjective [2]. Objective diagnostics such as imaging and functional tests demonstrating ACNES are lacking.

The presence of a peripheral nerve entrapment such as carpal tunnel syndrome can be suggested by a simple bedside test termed the scratch collapse test (SCT). Originally developed by Mackinnon, this test is based on the theory that stimulation of the skin (scratching) covering an entrapped nerve is perceived by the body as a noxious stimulus [8]. As a consequence, a short-term inhibition of voluntary muscle activity occurs, which may be caused by the cutaneous silent period. This inhibition is reflected by a paresis of the shoulder exorotator muscles [8,9,10]. The use of the SCT has been described in several other peripheral entrapment neuropathies involving the ulnar, peroneal, and long thoracic nerve [11,12,13].

Most authors would argue that ACNES should be considered as a peripheral intercostal nerve entrapment, but evidence is currently lacking. Recently, a positive SCT was described in three ACNES patients [14]. The aim of the present study is to investigate whether an SCT was positive in patients with suspected ACNES. If so, this finding may support its hypothesized neuropathic character.

2 Methods

2.1 Study design

This prospective, case–control study was conducted between April and September 2021 at the Máxima Medical Centre (MMC), Eindhoven, the Netherlands. The Medical Ethics Committee of MMC approved the study design, protocol, and informed consent procedure (N21.026). All participants provided informed consent before enrollment. The present article was written according to the standards for reporting diagnostic accuracy studies guidelines [15].

2.2 Participants

All participants were 18 years or older. Overall exclusion criteria were related to inability to perform the SCT such as cognitive impairment (i.e. unable to follow instructions), insufficient muscle strength to offer resistance to examiner (rotator cuff insufficiency, upper extremity muscle/nervous disease), or a language barrier.

2.2.1 ACNES

ACNES patients were recruited at SolviMáx, a center of excellence for abdominal wall and groin pain, a thematic specialized outpatient surgery department of MMC. During a nine-week period, consecutive patients who were evaluated for possible ACNES were included if the clinical suggestion of unilateral ACNES was confirmed. The diagnosis was based on suggestive history and physical examination as previously published major and minor criteria (Table 1) [2].

Major and minor criteria for ACNES [2]

| ACNES criteria | ||

|---|---|---|

| Major | Minor | |

| History |

|

|

| Physical examination |

|

|

| Additional information |

|

|

CAPW = chronic abdominal wall pain.

Exclusion criteria were earlier ACNES treatment, two or more ACNES tender points, other abdominal wall pathology such as a tumor, hernia, endometriosis, or nerve entrapment due to scar tissue, or previous surgical nerve injury. MJ and LS included ACNES patients and performed the SCT.

2.2.2 Acute abdomen controls

Consecutive participants diagnosed at the MMC with acute appendicitis, acute cholecystitis, or complicated diverticulitis were recruited after admission just prior to surgery. The intra-abdominal pathology diagnosis was confirmed by blood analysis and ultrasound or computed tomography. The exclusion criterion was a history of abdominal wall pathology including ACNES. MJ and two surgical residents skilled in the management of ACNES included these participants and performed the SCT.

2.2.3 Healthy controls

Healthy adults were randomly recruited using a flyer at the MMC surgical outpatient department. Exclusion criteria were recent intra-abdominal pathology and abdominal wall pathology including ACNES. Inclusion and SCT were performed by MJ and LS.

2.3 SCT

Prior to patient enrollment, video material from earlier studies on the SCT and instructions from the pioneering publication were carefully analyzed by the study team and two surgical residents. The technique was subsequently optimized and practiced using different positions (standing, lying, sitting) and scratching techniques (one finger, three fingers, a plastic fork, a cotton swab) during five 30-min sessions by LS [8,10,12,16]. The most reliable version of the SCT was found with a patient in a standing position using a three-finger scratch from lateral to medial, according to the course of the intercostal nerve. Both sides of the abdomen were scratched simultaneously. By doing so, any collapse of the ipsilateral arm was not interpreted as a shock effect. After modifying the SCT for ACNES, LS has provided expert training to all examiners.

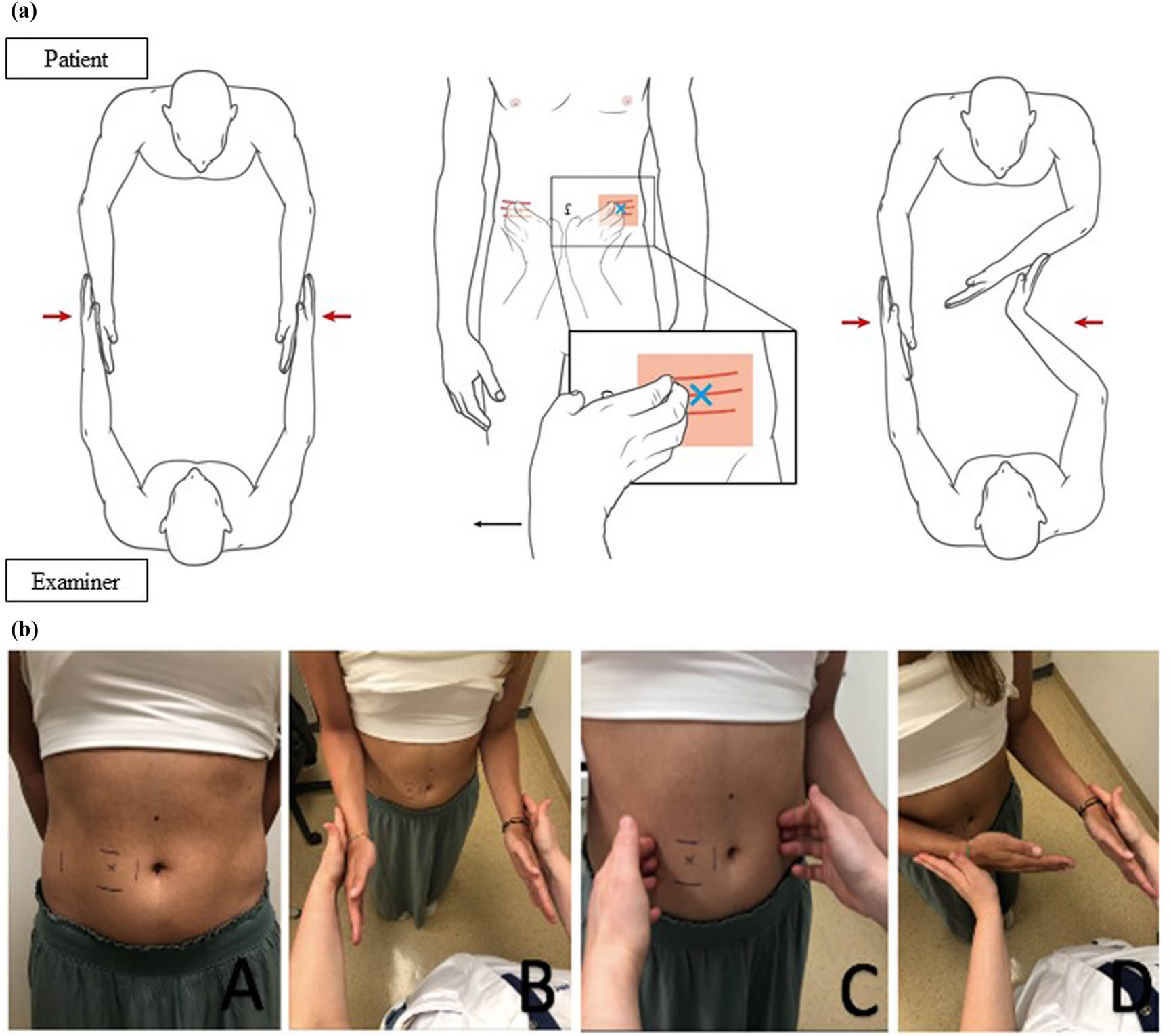

The SCT was performed as depicted in Figure 1 and Video S1, Supplementary material. Prior to testing, the area of interest for the scratch was marked with a pen. The test was positive if the ipsilateral arm collapsed inwards (Figure 1: 1d). The test was considered negative in the case where the patient was able to resist the examiner without a collapse, or when the result was doubtful. To avoid bias, the SCT was performed only once and participants were not informed of the possible test outcomes [8].

SCT for abdominal wall nerve entrapment (a) graphic; (b) picture representation. (A) Abdominal wall of a patient diagnosed with ACNES with tender point (x) corresponding with right 10th thoracic intercostal nerve. (B) Patient standing in front of the examiner with elbows in 90° flexion and hands outstretched with wrists in the neutral position. Equal pressure to the forearms is given by the examiner while the patient resists by rotating the shoulders external. (C) Examiner “scratches” the right 10th thoracic dermatome and corresponding contralateral dermatome. (D) Step B is repeated immediately thereafter. The test is positive if an internal collapse of the ipsilateral arm occurs as depicted.

Patients with an acute abdomen were scratched over the dermatome covering the area of maximal tenderness as well as the contralateral dermatome. Healthy controls underwent the SCT over dermatomes matching those of ACNES patients. All performed SCTs in the ACNES and healthy control group were filmed in such a way that the patient was unrecognizable and could not be linked to any of the study groups. The acute abdomen controls were excluded from filming because they were wearing surgical clothes.

2.4 Measurements and outcomes

Baseline data such as length, weight, and pain numeric rating scale (score 0 = no pain, 10 = worst possible pain) were obtained from questionnaires and electronic patient files. The Chronic Abdominal Wall Pain scale (CAWP: 18-item score, ranging from 0 to 18 points) was obtained for ACNES patients and healthy controls. Earlier studies suggested that a CAWP score of 10 or more was associated with pain due to ACNES [17]. The Douleur Neuropathique en 4 Questions questionnaire for neuropathic pain (a score of four or more suggests neuropathic pain) was completed by all study participants. As the gold standard, all participants had a physical examination based on the previously mentioned ACNES criteria [2].

The primary outcome was the percentage of positive SCTs in the three study groups. Secondary outcomes were sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values of the SCT. The inter-observer reliability of videos of ACNES patients and healthy controls was assessed in random order by a team of four independent observers (first author, videographer, two independent, and blinded surgeons). To avoid bias, the acute abdomen group was not assessed as they were in a hospital room wearing surgical gowns. The final secondary outcome was the percentage of negative SCTs after a tender point injection in the ACNES group. The injection was administered by a freehand subfascial tender point injection using 5–10 mL of 1% lidocaine that was injected just beneath the anterior rectus sheath. The SCT was repeated 15 min after the injection [18].

2.5 Sample size and analysis

The sample size was based on a pilot study design with each group having 20 participants. For the sample size analysis, an effect size of 0.5 was chosen, expecting a large difference in effect between the groups. The p-value was set at ≤0.05 and the degree of freedom at 1, considering the results were displayed in a 2 × 2 table. A power of 0.89 was achieved with a cohort of 40 participants.

Baseline characteristics of continuous variables were depicted as mean and standard deviation if parametric or median and range if non-parametric. Group differences were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance or Kruskal–Wallis test depending on Levene’s test for equality of variance. Categorical variables were presented as counts and differences were analyzed by Chi-square or Fisher’s exact test as appropriate. The difference in CAWP score was analyzed using the Mann–Whitney U test. Primary outcome analysis was done by the Chi-square test. Predictive values were calculated based on the combined results of two 2 × 2 tables. Confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated using an online tool for binomial proportion CI [19]. Fleiss’ kappa for multirater agreement was used for the video-inter-observer reliability. Analysis of the SCT 15 min after injection treatment was done using the McNemar test. A p-value of ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data analysis was performed using SPSS version 28 for Windows.

3 Results

Participants were consecutively recruited between April and September 2021, starting with the ACNES patients (n = 20), followed by the matched healthy controls (n = 20), and finally the acute abdomen patients (n = 20). No participant was excluded or terminated the study prematurely. In both the ACNES and healthy control group, one participant was pregnant in the second trimester. Tender points among ACNES patients were accordingly distributed at the right upper quadrant (Th7-9; n = 7), left upper quadrant (n = 1), right lower quadrant (Th10-12; n = 4), and left lower quadrant (n = 8). The majority of participants in the intra-abdominal pathology group had acute appendicitis (n = 15), whereas acute cholecystitis and complicated diverticulitis were diagnosed in two and three participants, respectively. Baseline study group characteristics are presented in Tables 2 and 3. The BMI was significantly different as healthy controls had the lowest BMI. All ACNES patients had a minimal 10-point CAWP-18 score (median 13; range 10–17 points). In contrast, scores in healthy controls were, except for one, below this cut-off score. This healthy participant was pregnant and had a CAWP18 score of 10 points. Interestingly, she was also the only healthy participant experiencing altered skin sensation, cq. hypoesthesia. A positive response to both pinching and Carnett’s test was only present in ACNES patients.

Baseline characteristics

| ACNES (n = 20) | Acute abdomen (n = 20) | Healthy control (n = 20) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age* | 37 (19–75) | 46 (19–76) | 30 (20–75) | 0.180 |

| Female§ | 16 (80%) | 12 (60%) | 16 (80%) | 0.256 |

| Height (cm) | 170 (11) | 171 (9) | 175 (9) | 0.139 |

| Weight (kg) | 75 (18) | 76 (14) | 68 (10) | 0.162 |

| BMI (kg/m²) | 26 (5) | 26 (4) | 22 (3) | 0.012 |

Data are represented as number (%) § , median (range)*, mean (standard deviation), or p values. ACNES = anterior cutaneous nerve entrapment syndrome; BMI = body mass index. Bold indicates statistically significant.

Baseline questionnaires and physical examination

| ACNES (n = 20) | Acute abdomen (n = 20) | Healthy control (n = 20) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Presence of visceral complaints | 13 | 13 | 1 |

| NRS* | 7 (4–10) | 6 (1–10) | 0 (0–2) |

| 18-Item CAWP score* | 13 (10–17) | — | 7 (3–10) |

| DN4* | 4 (1–7) | 0 (0–5) | 0 (0–3) |

| Skin sensation | |||

| Normal | 2 | 13 | 19 |

| Hypoesthesia | 15 | 3 | 1 |

| Hyperesthesia | 3 | 4 | 0 |

| Cold perception | |||

| Normal | 3 | 12 | 20 |

| Less | 16 | 8 | 0 |

| More | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Positive pinch | 19 | 0 | 0 |

| Positive Carnett’s test | 20 | 0 | 0 |

Data are represented as number of cases (%) or median (range)*. ACNES = anterior cutaneous nerve entrapment syndrome; NRS = numerical rating scale; CAPW = chronic abdominal wall pain; DN4 = Douleur Neuropathique en 4 Question.

3.1 SCT

The SCT was positive in all but one ACNES patients. During physical examination, local hypoesthesia, less cold perception, positive pinching, and a positive Carnett’s test at the tender point were present in this one patient. Conversely, the SCT was negative in all 40 controls (p = 0.001).

3.2 Diagnostic values of the SCT for ACNES

A 95% test sensitivity and a 100% specificity for the diagnosis of ACNES were calculated. Predictive values and CIs are presented in Table 4.

Diagnostic values of the SCT for ACNES

| Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | NPV | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACNES vs acute abdomen (n = 40) | 95 (75.13–99.87) | 100 (83.16–100) | 100 (82.35–100) | 95 (76.18–99.88) |

| ACNES vs all controls (n = 60) | 95 (75.13–99.87) | 100 (91.19–100) | 100 (82.35–100) | 98 (87.14–99.94) |

Data are represented as percentage with 95% CI. ACNES = anterior cutaneous nerve entrapment syndrome; PPV = positive predictive value; NPV = negative predictive value.

3.3 Video inter-observer reliability

Fleiss’ kappa for the video-inter-observer reliability among the four observers was 0.951 (95% CI: 0.829–1.073; p < 0.001) indicating a high agreement.

3.4 The SCT after tender point injection

Immediately after the diagnosis of ACNES was attained, 14 of 20 patients received a freehand 5–10 mL 1% lidocaine subfascial injection at the tender point. The remaining six patients did not undergo a tender point injection after a shared decision between surgeon and patient. Prior to injection, the SCT was positive in all 14 patients. 15 min after the injection, the SCT became negative in 11 patients (79%, p = 0.001).

4 Discussion

This study shows high values of sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values of the SCT in patients suspected of having ACNES. It is therefore believed that the SCT may serve as a valuable additional tool supporting the diagnosis of ACNES. The only other available literature on the SCT in ACNES is limited to a recent report also describing a positive SCT in three patients with ACNES [14]. The present controlled study is the first and unique as it compared the outcome of an SCT in ACNES patients with patients having acute intra-abdominal pathology as well as with healthy controls.

It is unclear to most physicians whether ACNES should be considered as a neuropathy. In a number of other peripheral neuropathies such as cubital tunnel syndrome and peroneal nerve entrapment, the SCT was often positive and was advised as an adjunct diagnostic tool [8,10,11,12]. The results of the present study are striking as the SCT was positive in 95% of patients with ACNES. These findings indicate that ACNES should be considered as a peripheral neuropathy. Interestingly, some study patients with acute intra-abdominal pathology such as acute appendicitis also exhibited altered skin sensation and/or cold perception. However, regardless of physical examination findings which indicate some form of cutaneous nerve involvement, the SCT appeared negative in these patients. It may well be that their cutaneous nerves are sensitized based on viscero-somatic convergence, while the nerve itself is neither entrapped nor directly involved in causing the abdominal pain [20,21]. This hypothesis is in contrast to the cause of pain observed in patients with ACNES, in which the nerve is believed to be “anatomically” entrapped in the rectus abdominis muscle. Interestingly, SCTs turned negative in most ACNES patients (79%) following a subfascial lidocaine tender point injection. This phenomenon was also reported after successful surgery for tarsal tunnel syndrome and long thoracic nerve entrapment [13,22].

To date, the diagnosis of ACNES is the summation of a number of highly subjective symptoms and signs. A confirmatory gold standard test is currently not available. Clues in history, a high CAWP scale score, and signs during physical examination constitute sets of major and minor criteria (Table 1) [2]. There is no minimal number of criteria to be met. However, as ACNES is an alleged neuropathic pain entrapment syndrome, related characteristics must be present. The present study strongly suggests that the results of the SCT should also be considered a major criterion, as it is an adjunct test with high diagnostic values. Future studies will determine the role of a positive SCT in the sets of current ACNES criteria.

As stipulated earlier, an SCT may serve as an adjunct diagnostic tool for various peripheral (mono) neuropathies [8]. The test is non-invasive and can be performed in virtually any setting. However, the pathophysiological mechanism is not well understood and overall accuracy is variable. One review showed that sensitivities ranged from 0.24 to 0.77, whereas specificity was between 0.60 and 0.99 [23]. A profound knowledge of nerve anatomy and extensive practice are crucial for obtaining optimal test characteristics [10]. The lowest test validity was reported in a study with inexperienced physicians who were also blinded for patient history and physical examination results [24]. In contrast, another study showed a high sensitivity if tests were executed by a hands-on trained surgeon compared to surgeons who were just instructed by video [25]. To be useful as a confirmatory diagnostic tool, a high specificity is necessary. The findings of the present study are in line with two prospective studies of the SCT pioneer having the highest diagnostic values [8,12]. Optimal test characteristics in the current study are likely explained by the author’s extensive practice time and intensive training. A high inter-observer reliability confirms an appropriate test execution. One study found a substantial (κ = 0.63) agreement in SCT interpretation between a treating surgeon and blinded observers [26]. In the present study, an exceedingly high agreement (κ = 0.95) was found in the judgment of videos. Video inter-observer reliability testing was required to avoid confirmation bias. It is possible that repeated SCT by multiple blinded physicians might lead to bias due to the progressive knowledge of the patient and the extinction of the silent period.

The results of the present study may generate a plethora of novel study aims. It may be worthwhile to quantify SCT outcomes by developing a device that measures the administered force both by the physician and the loss of strength in the collapsing arm. Subsequently, the optimal force for the most accurate SCT may be unveiled. Future studies could also focus on the identification of additional methods contributing to the ACNES diagnosis, for example, electromyographical data associated with an SCT. More insight may be gained into SCT results and ACNES management efficacy. For instance, it may be hypothesized that SCT test results predict ACNES treatment outcome. In addition, the role of SCT in recurrent ACNES is not studied yet.

The present study has limitations. The investigator was aware of the tender point location and thus side of the potential arm collapse. This knowledge might have influenced the force that was exerted on the patient’s arms. However, patients were neither familiar with the details of the SCT nor with potential test outcomes. Many of them were astonished or even frightened after the temporary paresis and communicated these emotions with the investigator.

5 Conclusion

The present study in patients who were diagnosed with ACNES indicates that the SCT has a high sensitivity (95%; CI: 75–99) and specificity (100%; CI: 83–100) for the diagnosis. Conversely, a positive test result was not attained once in healthy controls and groups of patients with acute intra-abdominal pathology. A positive SCT is a more objective diagnostic tool that may be added to the set of major criteria for ACNES. This report is the first to support the hypothesis that ACNES is a pain syndrome that is caused by a peripheral neuropathy.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. B. Corten and Dr. W. Zwaans, for their support on data collection, and Dr. L. Janssen, for her assistance with the statistical analyses.

-

Research ethics: Research involving human subjects complied with all relevant national regulations and institutional policies and is in accordance with the tenets of the Helsinki Declaration (as amended in 2013). The Medical Ethics Committee of MMC approved the study design, protocol, and informed consent procedure (N21.026).

-

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individuals included in this study.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this article and approved its submission.

-

Competing interests: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: None declared.

-

Data availability: The authors will consider data and video sharing requests on a case-by-case basis. Requests should be sent to the corresponding author for further information.

-

Artificial intelligence/Machine learning tools: Not applicable.

-

Trial registration: The Local Medical Ethics Committee of Máxima Medical Centre number N21.026.

-

Supplementary Material: This article contains supplementary material (followed by the link to the article online).

References

[1] Applegate WV. Abdominal cutaneous nerve entrapment syndrome (ACNES): A commonly overlooked cause of abdominal pain. Perm J. 2002;6(3):20–7.Search in Google Scholar

[2] Scheltinga M, Roumen R. Anterior cutaneous nerve entrapment syndrome (ACNES). Hernia. 2018 Jun;22(3):507–16.10.1007/s10029-017-1710-zSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[3] Carnett JB. Intercostal neuralgia as a cause of abdominal pain and tenderness. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1926;42:625–32.Search in Google Scholar

[4] Applegate WV. Abdominal cutaneous nerve entrapment syndrome. Surgery. 1972;71:118–24.Search in Google Scholar

[5] Applegate WV, Buckwalter NR. Microanatomy of the structures contributing to abdominal cutaneous nerve entrapment syndrome. J Am Board Fam Pract. 1997;10(5):329–32.Search in Google Scholar

[6] Boelens OB, Scheltinga MR, Houterman S, Roumen RM. Randomized clinical trial of trigger point infiltration with lidocaine to diagnose anterior cutaneous nerve entrapment syndrome. Br J Surg. 2013;100(2):217–21.10.1002/bjs.8958Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[7] Boelens OB, van Assen T, Houterman S, Scheltinga MR, Roumen RM. A double-blind, randomized, controlled trial on surgery for chronic abdominal pain due to anterior cutaneous nerve entrapment syndrome. Ann Surg. 2013;257(5):845–9.10.1097/SLA.0b013e318285f930Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[8] Cheng CJ, Mackinnon-Patterson B, Beck JL, Mackinnon SE. Scratch collapse test for evaluation of carpal and cubital tunnel syndrome. J Hand Surg. 2008;33(9):1518–24.10.1016/j.jhsa.2008.05.022Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] Floeter MK. Cutaneous silent periods. Muscle Nerve. 2003;28:391–401.10.1002/mus.10447Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[10] Kahn L, Yee A, Mackinnon S. Important details in performing and interpreting the scratch collapse test. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2018;141(2):399–407.10.1097/PRS.0000000000004082Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] Davidge KM, Gontre G, Tang D, Boyd KU, Yee A, Damiano MS, et al. The “hierarchical” scratch collapse test for identifying multilevel ulnar nerve compression. Hand (N Y). 2015;10(3):388–95.10.1007/s11552-014-9721-zSearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[12] Gillenwater J, Cheng J, Mackinnon S. Evaluation of the scratch collapse test in peroneal nerve compression. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;128(4):933–9.10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181f95c36Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[13] Pinder E, Yew C. Scratch collapse test is a useful clinical sign in assessing long thoracic nerve entrapment. J Hand Microsurg. 2016;8(2):122–4.10.1055/s-0036-1585429Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[14] Schaap L, Jacobs MLYE, Scheltinga MRM, Roumen RMH. The scratch collapse test in patients diagnosed with anterior cutaneous nerve entrapment syndrome (ACNES): A report of three cases. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2023;105:108099.10.1016/j.ijscr.2023.108099Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[15] Bossuyt PM, Reitsma JB, Bruns DE, Gatsonis CA, Glasziou PP, Irwig L, et al. For the STARD group. STARD 2015: An updated list of essential items for reporting diagnostic accuracy studies. BMJ. 2015;351:h5527.10.1136/bmj.h5527Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[16] Huynh M, Karir A, Bennett A. Scratch collapse test for carpal tunnel syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2018;6(9):1–7.10.1097/GOX.0000000000001933Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[17] Van Assen T, De Jager-Kievit J, Scheltinga M, Roumen RM. Chronic abdominal wall pain misdiagnosed as function abdominal pain. J Am Board Fam Med. 2013;26(6):738–44.10.3122/jabfm.2013.06.130115Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[18] Jacobs MLYE, van den Dungen-Roelofsen R, Heemskerk J, Scheltinga MRM, Roumen RMH. Ultrasound-guided abdominal wall infiltration versus freehand technique in anterior cutaneous nerve entrapment syndrome (ACNES): randomized clinical trial. BJS Open. 2021;5(6):zrab124. 10.1093/bjsopen/zrab124.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[19] MedCalc Software Ltd. Diagnostic test evaluation calculator. https://www.medcalc.org/calc/diagnostic_test.php (Version 20.218; accessed April 12, 2023).Search in Google Scholar

[20] Head H. On disturbances of sensation with especial reference to the pain of visceral disease, Part I. Brain. 1893;16(1–2):1–133.10.1093/brain/16.1-2.1Search in Google Scholar

[21] Roumen RMH, Vening W, Wouda R, Scheltinga M. Acute appendicitis, somatosensory disturbances (“Head Zones”), and the differential diagnosis of anterior cutaneous nerve entrapment syndrome (ACNES). J Gastrointest Surg. 2017;21(6):1055–61.10.1007/s11605-017-3417-ySearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[22] Turan I, Hagert E, Jakobsson J. The scratch collapse test supported the diagnosis and showed successful treatment of tarsal tunnel syndrome. J Med Cases. 2013;4(11):746–7.10.4021/jmc1453wSearch in Google Scholar

[23] Čebron U, Curtin CM. The scratch collapse test: A systematic review. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2018;71(12):1693–703.10.1016/j.bjps.2018.09.003Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[24] Simon J, Lutsky K, Maltenfort M, Beredjiklian PK. The accuracy of the scratch collapse test performed by blinded examiners on patients with suspected carpal tunnel syndrome assessed by electrodiagnostic studies. J Hand Surg Am. 2017;42(5):386.10.1016/j.jhsa.2017.01.031Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[25] Makanji H, Becker S, Mudgal C, Jupiter JB, Ring D. Evaluation of the scratch collapse test for the diagnosis of carpal tunnel syndrome. J Hand Surg Eur. 2014;39(2):181–6.10.1177/1753193413497191Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[26] Blok RD, Becker SJ, Ring DC. Diagnosis of carpal tunnel syndrome: interobserver reliability of the blinded scratch-collapse test. J Hand Microsurg. 2014;6(1):5–7.10.1007/s12593-013-0105-3Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Editorial Comment

- From pain to relief: Exploring the consistency of exercise-induced hypoalgesia

- Christmas greetings 2024 from the Editor-in-Chief

- Original Articles

- The Scandinavian Society for the Study of Pain 2022 Postgraduate Course and Annual Scientific (SASP 2022) Meeting 12th to 14th October at Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen

- Comparison of ultrasound-guided continuous erector spinae plane block versus continuous paravertebral block for postoperative analgesia in patients undergoing proximal femur surgeries

- Clinical Pain Researches

- The effect of tourniquet use on postoperative opioid consumption after ankle fracture surgery – a retrospective cohort study

- Changes in pain, daily occupations, lifestyle, and health following an occupational therapy lifestyle intervention: a secondary analysis from a feasibility study in patients with chronic high-impact pain

- Tonic cuff pressure pain sensitivity in chronic pain patients and its relation to self-reported physical activity

- Reliability, construct validity, and factorial structure of a Swedish version of the medical outcomes study social support survey (MOS-SSS) in patients with chronic pain

- Hurdles and potentials when implementing internet-delivered Acceptance and commitment therapy for chronic pain: a retrospective appraisal using the Quality implementation framework

- Exploring the outcome “days with bothersome pain” and its association with pain intensity, disability, and quality of life

- Fatigue and cognitive fatigability in patients with chronic pain

- The Swedish version of the pain self-efficacy questionnaire short form, PSEQ-2SV: Cultural adaptation and psychometric evaluation in a population of patients with musculoskeletal disorders

- Pain coping and catastrophizing in youth with and without cerebral palsy

- Neuropathic pain after surgery – A clinical validation study and assessment of accuracy measures of the 5-item NeuPPS scale

- Translation, contextual adaptation, and reliability of the Danish Concept of Pain Inventory (COPI-Adult (DK)) – A self-reported outcome measure

- Cosmetic surgery and associated chronic postsurgical pain: A cross-sectional study from Norway

- The association of hemodynamic parameters and clinical demographic variables with acute postoperative pain in female oncological breast surgery patients: A retrospective cohort study

- Healthcare professionals’ experiences of interdisciplinary collaboration in pain centres – A qualitative study

- Effects of deep brain stimulation and verbal suggestions on pain in Parkinson’s disease

- Painful differences between different pain scale assessments: The outcome of assessed pain is a matter of the choices of scale and statistics

- Prevalence and characteristics of fibromyalgia according to three fibromyalgia diagnostic criteria: A secondary analysis study

- Sex moderates the association between quantitative sensory testing and acute and chronic pain after total knee/hip arthroplasty

- Tramadol-paracetamol for postoperative pain after spine surgery – A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study

- Cancer-related pain experienced in daily life is difficult to communicate and to manage – for patients and for professionals

- Making sense of pain in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD): A qualitative study

- Patient-reported pain, satisfaction, adverse effects, and deviations from ambulatory surgery pain medication

- Does pain influence cognitive performance in patients with mild traumatic brain injury?

- Hypocapnia in women with fibromyalgia

- Application of ultrasound-guided thoracic paravertebral block or intercostal nerve block for acute herpes zoster and prevention of post-herpetic neuralgia: A case–control retrospective trial

- Translation and examination of construct validity of the Danish version of the Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia

- A positive scratch collapse test in anterior cutaneous nerve entrapment syndrome indicates its neuropathic character

- ADHD-pain: Characteristics of chronic pain and association with muscular dysregulation in adults with ADHD

- The relationship between changes in pain intensity and functional disability in persistent disabling low back pain during a course of cognitive functional therapy

- Intrathecal pain treatment for severe pain in patients with terminal cancer: A retrospective analysis of treatment-related complications and side effects

- Psychometric evaluation of the Danish version of the Pain Self-Efficacy Questionnaire in patients with subacute and chronic low back pain

- Dimensionality, reliability, and validity of the Finnish version of the pain catastrophizing scale in chronic low back pain

- To speak or not to speak? A secondary data analysis to further explore the context-insensitive avoidance scale

- Pain catastrophizing levels differentiate between common diseases with pain: HIV, fibromyalgia, complex regional pain syndrome, and breast cancer survivors

- Prevalence of substance use disorder diagnoses in patients with chronic pain receiving reimbursed opioids: An epidemiological study of four Norwegian health registries

- Pain perception while listening to thrash heavy metal vs relaxing music at a heavy metal festival – the CoPainHell study – a factorial randomized non-blinded crossover trial

- Observational Studies

- Cutaneous nerve biopsy in patients with symptoms of small fiber neuropathy: a retrospective study

- The incidence of post cholecystectomy pain (PCP) syndrome at 12 months following laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a prospective evaluation in 200 patients

- Associations between psychological flexibility and daily functioning in endometriosis-related pain

- Relationship between perfectionism, overactivity, pain severity, and pain interference in individuals with chronic pain: A cross-lagged panel model analysis

- Access to psychological treatment for chronic cancer-related pain in Sweden

- Validation of the Danish version of the knowledge and attitudes survey regarding pain

- Associations between cognitive test scores and pain tolerance: The Tromsø study

- Healthcare experiences of fibromyalgia patients and their associations with satisfaction and pain relief. A patient survey

- Video interpretation in a medical spine clinic: A descriptive study of a diverse population and intervention

- Role of history of traumatic life experiences in current psychosomatic manifestations

- Social determinants of health in adults with whiplash associated disorders

- Which patients with chronic low back pain respond favorably to multidisciplinary rehabilitation? A secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial

- A preliminary examination of the effects of childhood abuse and resilience on pain and physical functioning in patients with knee osteoarthritis

- Differences in risk factors for flare-ups in patients with lumbar radicular pain may depend on the definition of flare

- Real-world evidence evaluation on consumer experience and prescription journey of diclofenac gel in Sweden

- Patient characteristics in relation to opioid exposure in a chronic non-cancer pain population

- Topical Reviews

- Bridging the translational gap: adenosine as a modulator of neuropathic pain in preclinical models and humans

- What do we know about Indigenous Peoples with low back pain around the world? A topical review

- The “future” pain clinician: Competencies needed to provide psychologically informed care

- Systematic Reviews

- Pain management for persistent pain post radiotherapy in head and neck cancers: systematic review

- High-frequency, high-intensity transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation compared with opioids for pain relief after gynecological surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis

- Reliability and measurement error of exercise-induced hypoalgesia in pain-free adults and adults with musculoskeletal pain: A systematic review

- Noninvasive transcranial brain stimulation in central post-stroke pain: A systematic review

- Short Communications

- Are we missing the opioid consumption in low- and middle-income countries?

- Association between self-reported pain severity and characteristics of United States adults (age ≥50 years) who used opioids

- Could generative artificial intelligence replace fieldwork in pain research?

- Skin conductance algesimeter is unreliable during sudden perioperative temperature increases

- Original Experimental

- Confirmatory study of the usefulness of quantum molecular resonance and microdissectomy for the treatment of lumbar radiculopathy in a prospective cohort at 6 months follow-up

- Pain catastrophizing in the elderly: An experimental pain study

- Improving general practice management of patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain: Interdisciplinarity, coherence, and concerns

- Concurrent validity of dynamic bedside quantitative sensory testing paradigms in breast cancer survivors with persistent pain

- Transcranial direct current stimulation is more effective than pregabalin in controlling nociceptive and anxiety-like behaviors in a rat fibromyalgia-like model

- Paradox pain sensitivity using cuff pressure or algometer testing in patients with hemophilia

- Physical activity with person-centered guidance supported by a digital platform or with telephone follow-up for persons with chronic widespread pain: Health economic considerations along a randomized controlled trial

- Measuring pain intensity through physical interaction in an experimental model of cold-induced pain: A method comparison study

- Pharmacological treatment of pain in Swedish nursing homes: Prevalence and associations with cognitive impairment and depressive mood

- Neck and shoulder pain and inflammatory biomarkers in plasma among forklift truck operators – A case–control study

- The effect of social exclusion on pain perception and heart rate variability in healthy controls and somatoform pain patients

- Revisiting opioid toxicity: Cellular effects of six commonly used opioids

- Letter to the Editor

- Post cholecystectomy pain syndrome: Letter to Editor

- Response to the Letter by Prof Bordoni

- Response – Reliability and measurement error of exercise-induced hypoalgesia

- Is the skin conductance algesimeter index influenced by temperature?

- Skin conductance algesimeter is unreliable during sudden perioperative temperature increase

- Corrigendum

- Corrigendum to “Chronic post-thoracotomy pain after lung cancer surgery: a prospective study of preoperative risk factors”

- Obituary

- A Significant Voice in Pain Research Björn Gerdle in Memoriam (1953–2024)

Articles in the same Issue

- Editorial Comment

- From pain to relief: Exploring the consistency of exercise-induced hypoalgesia

- Christmas greetings 2024 from the Editor-in-Chief

- Original Articles

- The Scandinavian Society for the Study of Pain 2022 Postgraduate Course and Annual Scientific (SASP 2022) Meeting 12th to 14th October at Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen

- Comparison of ultrasound-guided continuous erector spinae plane block versus continuous paravertebral block for postoperative analgesia in patients undergoing proximal femur surgeries

- Clinical Pain Researches

- The effect of tourniquet use on postoperative opioid consumption after ankle fracture surgery – a retrospective cohort study

- Changes in pain, daily occupations, lifestyle, and health following an occupational therapy lifestyle intervention: a secondary analysis from a feasibility study in patients with chronic high-impact pain

- Tonic cuff pressure pain sensitivity in chronic pain patients and its relation to self-reported physical activity

- Reliability, construct validity, and factorial structure of a Swedish version of the medical outcomes study social support survey (MOS-SSS) in patients with chronic pain

- Hurdles and potentials when implementing internet-delivered Acceptance and commitment therapy for chronic pain: a retrospective appraisal using the Quality implementation framework

- Exploring the outcome “days with bothersome pain” and its association with pain intensity, disability, and quality of life

- Fatigue and cognitive fatigability in patients with chronic pain

- The Swedish version of the pain self-efficacy questionnaire short form, PSEQ-2SV: Cultural adaptation and psychometric evaluation in a population of patients with musculoskeletal disorders

- Pain coping and catastrophizing in youth with and without cerebral palsy

- Neuropathic pain after surgery – A clinical validation study and assessment of accuracy measures of the 5-item NeuPPS scale

- Translation, contextual adaptation, and reliability of the Danish Concept of Pain Inventory (COPI-Adult (DK)) – A self-reported outcome measure

- Cosmetic surgery and associated chronic postsurgical pain: A cross-sectional study from Norway

- The association of hemodynamic parameters and clinical demographic variables with acute postoperative pain in female oncological breast surgery patients: A retrospective cohort study

- Healthcare professionals’ experiences of interdisciplinary collaboration in pain centres – A qualitative study

- Effects of deep brain stimulation and verbal suggestions on pain in Parkinson’s disease

- Painful differences between different pain scale assessments: The outcome of assessed pain is a matter of the choices of scale and statistics

- Prevalence and characteristics of fibromyalgia according to three fibromyalgia diagnostic criteria: A secondary analysis study

- Sex moderates the association between quantitative sensory testing and acute and chronic pain after total knee/hip arthroplasty

- Tramadol-paracetamol for postoperative pain after spine surgery – A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study

- Cancer-related pain experienced in daily life is difficult to communicate and to manage – for patients and for professionals

- Making sense of pain in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD): A qualitative study

- Patient-reported pain, satisfaction, adverse effects, and deviations from ambulatory surgery pain medication

- Does pain influence cognitive performance in patients with mild traumatic brain injury?

- Hypocapnia in women with fibromyalgia

- Application of ultrasound-guided thoracic paravertebral block or intercostal nerve block for acute herpes zoster and prevention of post-herpetic neuralgia: A case–control retrospective trial

- Translation and examination of construct validity of the Danish version of the Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia

- A positive scratch collapse test in anterior cutaneous nerve entrapment syndrome indicates its neuropathic character

- ADHD-pain: Characteristics of chronic pain and association with muscular dysregulation in adults with ADHD

- The relationship between changes in pain intensity and functional disability in persistent disabling low back pain during a course of cognitive functional therapy

- Intrathecal pain treatment for severe pain in patients with terminal cancer: A retrospective analysis of treatment-related complications and side effects

- Psychometric evaluation of the Danish version of the Pain Self-Efficacy Questionnaire in patients with subacute and chronic low back pain

- Dimensionality, reliability, and validity of the Finnish version of the pain catastrophizing scale in chronic low back pain

- To speak or not to speak? A secondary data analysis to further explore the context-insensitive avoidance scale

- Pain catastrophizing levels differentiate between common diseases with pain: HIV, fibromyalgia, complex regional pain syndrome, and breast cancer survivors

- Prevalence of substance use disorder diagnoses in patients with chronic pain receiving reimbursed opioids: An epidemiological study of four Norwegian health registries

- Pain perception while listening to thrash heavy metal vs relaxing music at a heavy metal festival – the CoPainHell study – a factorial randomized non-blinded crossover trial

- Observational Studies

- Cutaneous nerve biopsy in patients with symptoms of small fiber neuropathy: a retrospective study

- The incidence of post cholecystectomy pain (PCP) syndrome at 12 months following laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a prospective evaluation in 200 patients

- Associations between psychological flexibility and daily functioning in endometriosis-related pain

- Relationship between perfectionism, overactivity, pain severity, and pain interference in individuals with chronic pain: A cross-lagged panel model analysis

- Access to psychological treatment for chronic cancer-related pain in Sweden

- Validation of the Danish version of the knowledge and attitudes survey regarding pain

- Associations between cognitive test scores and pain tolerance: The Tromsø study

- Healthcare experiences of fibromyalgia patients and their associations with satisfaction and pain relief. A patient survey

- Video interpretation in a medical spine clinic: A descriptive study of a diverse population and intervention

- Role of history of traumatic life experiences in current psychosomatic manifestations

- Social determinants of health in adults with whiplash associated disorders

- Which patients with chronic low back pain respond favorably to multidisciplinary rehabilitation? A secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial

- A preliminary examination of the effects of childhood abuse and resilience on pain and physical functioning in patients with knee osteoarthritis

- Differences in risk factors for flare-ups in patients with lumbar radicular pain may depend on the definition of flare

- Real-world evidence evaluation on consumer experience and prescription journey of diclofenac gel in Sweden

- Patient characteristics in relation to opioid exposure in a chronic non-cancer pain population

- Topical Reviews

- Bridging the translational gap: adenosine as a modulator of neuropathic pain in preclinical models and humans

- What do we know about Indigenous Peoples with low back pain around the world? A topical review

- The “future” pain clinician: Competencies needed to provide psychologically informed care

- Systematic Reviews

- Pain management for persistent pain post radiotherapy in head and neck cancers: systematic review

- High-frequency, high-intensity transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation compared with opioids for pain relief after gynecological surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis

- Reliability and measurement error of exercise-induced hypoalgesia in pain-free adults and adults with musculoskeletal pain: A systematic review

- Noninvasive transcranial brain stimulation in central post-stroke pain: A systematic review

- Short Communications

- Are we missing the opioid consumption in low- and middle-income countries?

- Association between self-reported pain severity and characteristics of United States adults (age ≥50 years) who used opioids

- Could generative artificial intelligence replace fieldwork in pain research?

- Skin conductance algesimeter is unreliable during sudden perioperative temperature increases

- Original Experimental

- Confirmatory study of the usefulness of quantum molecular resonance and microdissectomy for the treatment of lumbar radiculopathy in a prospective cohort at 6 months follow-up

- Pain catastrophizing in the elderly: An experimental pain study

- Improving general practice management of patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain: Interdisciplinarity, coherence, and concerns

- Concurrent validity of dynamic bedside quantitative sensory testing paradigms in breast cancer survivors with persistent pain

- Transcranial direct current stimulation is more effective than pregabalin in controlling nociceptive and anxiety-like behaviors in a rat fibromyalgia-like model

- Paradox pain sensitivity using cuff pressure or algometer testing in patients with hemophilia

- Physical activity with person-centered guidance supported by a digital platform or with telephone follow-up for persons with chronic widespread pain: Health economic considerations along a randomized controlled trial

- Measuring pain intensity through physical interaction in an experimental model of cold-induced pain: A method comparison study

- Pharmacological treatment of pain in Swedish nursing homes: Prevalence and associations with cognitive impairment and depressive mood

- Neck and shoulder pain and inflammatory biomarkers in plasma among forklift truck operators – A case–control study

- The effect of social exclusion on pain perception and heart rate variability in healthy controls and somatoform pain patients

- Revisiting opioid toxicity: Cellular effects of six commonly used opioids

- Letter to the Editor

- Post cholecystectomy pain syndrome: Letter to Editor

- Response to the Letter by Prof Bordoni

- Response – Reliability and measurement error of exercise-induced hypoalgesia

- Is the skin conductance algesimeter index influenced by temperature?

- Skin conductance algesimeter is unreliable during sudden perioperative temperature increase

- Corrigendum

- Corrigendum to “Chronic post-thoracotomy pain after lung cancer surgery: a prospective study of preoperative risk factors”

- Obituary

- A Significant Voice in Pain Research Björn Gerdle in Memoriam (1953–2024)