Improving general practice management of patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain: Interdisciplinarity, coherence, and concerns

-

Jesper Bie Larsen

, Pernille Borregaard

Abstract

Objectives

Management of patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain (CMP) remains a challenge in general practice. The general practitioner (GP) often experiences diagnostic uncertainty despite frequently referring patients with CMP to specialized departments. Therefore, it remains imperative to gain insights on how to optimize and reframe the current setup for the management of patients with CMP. The objective was to explore GP's perspectives on the challenges, needs, and visions for improving the management of patients with CMP.

Methods

A qualitative study with co-design using the future workshop approach. Eight GPs participated in the future workshop (five females). Insights and visions emerged from the GP's discussions and sharing of their experiences in managing patients with CMP. The audio-recorded data were subjected to thematic text analysis.

Results

The thematic analysis revealed four main themes, including (1) challenges with current pain management, (2) barriers to pain management, (3) the need for a biopsychosocial perspective, and (4) solutions and visions. All challenges are related to the complexity and diagnostic uncertainty for this patient population. GPs experienced that the patients' biomedical understanding of their pain was a barrier for management and underlined the need for a biopsychosocial approach when managing the patients. The GPs described taking on the role of coordinators for their patients with CMP but could feel ill-equipped to handle diagnostic uncertainty. An interdisciplinary unit was recommended as a possible solution to introduce a biopsychosocial approach for the examination, diagnosis, and management of the patient's CMP.

Conclusions

The complexity and diagnostic uncertainty of patients with CMP warrants a revision of the current setup. Establishing an interdisciplinary unit using a biopsychosocial approach was recommended as an option to improve the current management for patients with CMP.

1 Introduction

Chronic musculoskeletal pain (CMP) is a worldwide health problem and affects one in four individuals [1,2]. Chronic pain can be defined as a pain experience lasting for more than 3 months [3]. CMP is one of the main drivers of years lived with disability, and the overall cost for society is 2% of the gross national product [4]. Low back pain, neck pain, and shoulder pain are common pain sites, but patients often report multi-site pain [1,5,6]. Long-standing pain is often associated with significant concurrent psychological and social impact [7,8]. This is especially prevalent in a subgroup of complex patients with CMP. This subgroup is characterized by high healthcare utilization, with an average of 25 individual contacts per year [9,10]. They make up 8% of the total population of care-seeking patients with CMP [9].

In most healthcare systems, the general practitioner (GP) is the first point of contact for the patient experiencing CMP. The GP will oversee the management of the patient's CMP and will be able to refer the patient toward additional diagnostic examination or treatment in the specialized, secondary sector [11]. This traditional model of care may be challenged due to a lack of a specific pathoanatomical diagnosis in most patients with CMP [12]. This diagnostic uncertainty challenges the management of patients with complex CMP and frequently leads to time-consuming referrals back-and-forth between the GP and the specialized departments without the patient getting closer to a diagnosis or initiation of sufficient management of their CMP. This can leave the patients frustrated and discouraged [13,14].

Recent studies have shown that patients with CMP ask for an early interdisciplinary assessment, including a concrete plan with clear and uniform messages from all stakeholders [14,15]. However, GPs often feel ill-equipped to diagnose and manage patients with complex CMP [16,17]. This is evidenced by our recently conducted audit in Danish general practice (unpublished material). The audit showed that the GPs frequently referred patients to various specialized examinations and tried various treatments, including pain medication, and still, the GPs experienced diagnostic uncertainty in one-third of the patients.

The current unsatisfactory setup highlights the impending need to reframe our clinical management and care pathways for patients with complex CMP. It has been proposed that the management of patients with CMP should include interdisciplinary involvement [18]. However, before designing new care pathways, it is imperative to establish what the GPs consider crucial when developing examination and management options. Therefore, the objective of the study was to (1) investigate GP perspectives concerning challenges, needs, and solutions for the current management of patients with CMP and (2) provide feedback on the potential and concerns of developing an interdisciplinary unit to examine patients with complex CMP.

2 Methods

2.1 Design

We used Action Research methodology to guide the design of our workshop interventions and data analysis [19,20]. We planned and conducted a future workshop with GPs to obtain their input and visions of the challenges, needs, and possible solutions for patients with CMP [21]. A case vignette and inspiration card exercises were developed prior to the intervention, user-tested, and included to support dialogue and co-construction of knowledge during the future workshop [22,23]. Participant discussions were documented via audio recordings, transcribed ad verbatim, and analyzed through thematic text analysis [24] to identify individual, social, or systemic management challenges relevant to the design of a care pathway. A study protocol was submitted and reviewed by the North Denmark Region Committee on Health Research Ethics, which ruled the project was exempt from registration.

2.2 Setting and participants

GPs were included through the clinician networks of the Center for General Practice and Nord-Kap, the quality unit for General Practice in Northern Jutland, via emails, cold-calling, newsletters, and social media posts. All GPs in the North Denmark Region were eligible to participate in the study. Potential participants who responded positively to our inclusion efforts were contacted via telephone at the time of their choosing, screened, and provided with verbal and written information in accordance with the stipulations in the European General Data Protection Regulations. All participants signed a consent form as part of participating in the workshops.

2.3 Future workshop

We used the future workshop approach as described by Apel [21] and Vidal [25] to design our data collection component. Future workshops use a three-step design, which focuses on critique, social fantasy, and implementation to support dialogue and co-construction of knowledge during workshop interventions (Figure 1). Overall, the methodology is based upon an initial critique of the present situation, expanding into a creative brainstorming phase where solutions are generated by the workshop participants, ending up in establishing the visions for the future. During this project, the critique phase was oriented toward critically reviewing the current care pathways for patients with CMP and establishing an understanding of the experienced issues and challenges. Next, the fantasy phase created a space for exploring future possibilities for solutions without restrictions or other barriers. This was done to stimulate “out-of-box thinking” and enhance the possibility of finding unconventional solutions. Finally, the implementation phase adopted a more realistic view of the proposed solutions from the fantasy phase, as participants' suggestions were evaluated, discussed, and modified into solutions that were novel, valuable, and implementable [25].

![Figure 1

Overview of the phases, including the future workshop methodology (adapted from Vidal [25]).](/document/doi/10.1515/sjpain-2023-0070/asset/graphic/j_sjpain-2023-0070_fig_001.jpg)

Overview of the phases, including the future workshop methodology (adapted from Vidal [25]).

Through these generative activities and plenary discussions, future workshops aim to produce general shared visions for resolving real-world problems, which are novel, implementable, and lead to desirable futures [21].

The theme of the future workshop was defined as exploring visions for optimizing the management for adults with CMP conditions. A case vignette and inspiration card exercises were included as workshop activities to encourage participant dialogues and guide their discussions through the three workshop phases [22,23].

2.3.1 Case vignette

The case vignette was designed by the members of the research group (JBL, SKJ, JLT, and MSR) and reflected our understanding of the biopsychosocial challenges that could be present for a patient with CMP (Appendix S1, case). The case was designed to be recognizable to GPs and included a background story, plus relevant and irrelevant information presented as a narrative [23]. The case vignette was tested for comprehension and relevancy with two GPs with experience in treating CMP in general practice.

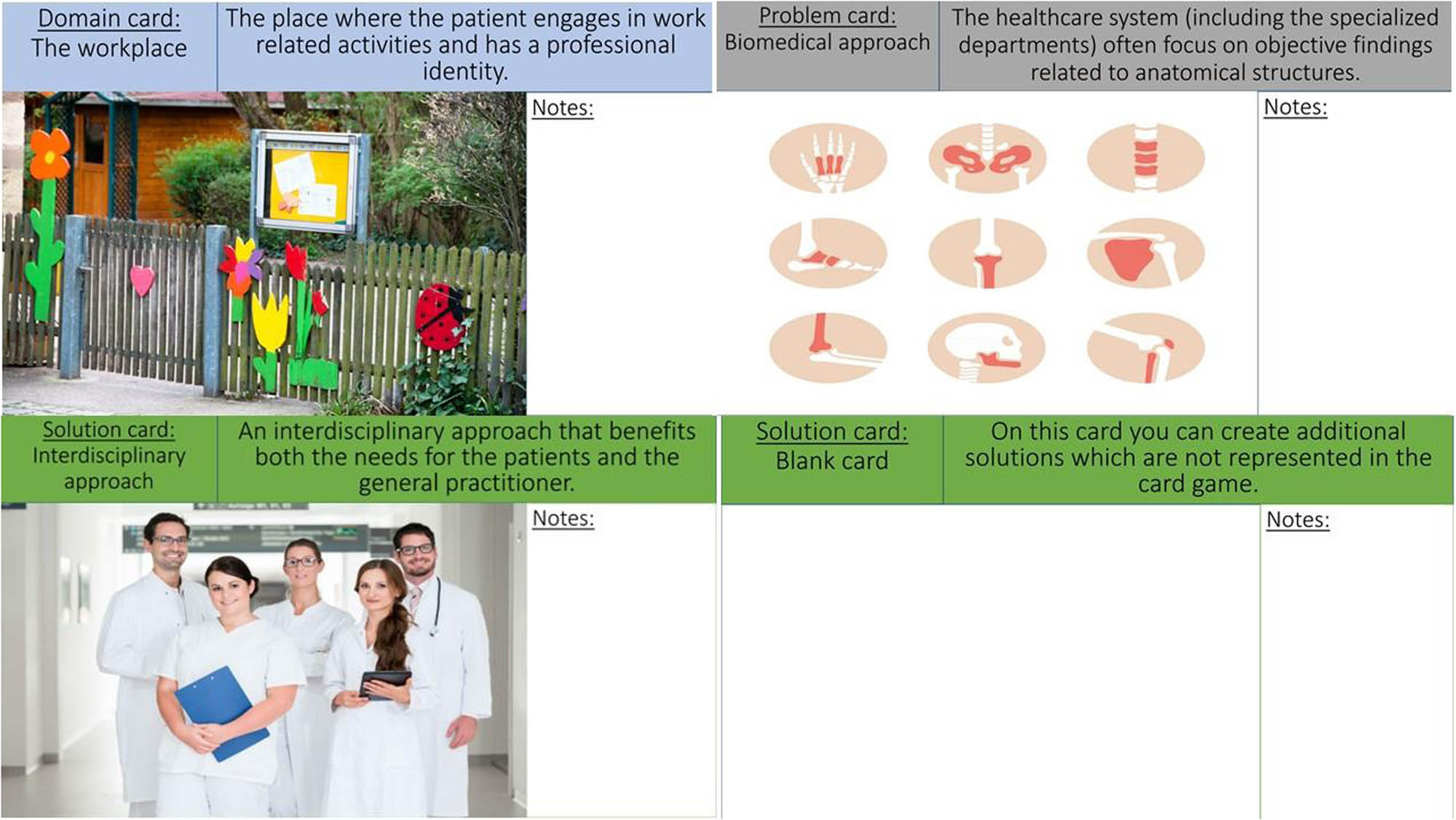

2.3.2 Inspiration cards

The inspiration card game (Appendix S2, Inspiration cards) was developed to stimulate conversations during workshops and help participants progress through the three workshop phases [22]. The cards featured themes related to three conceptual domains, including (1) patient domains, e.g., the home, workplace, and municipality; (2) problems, e.g., pain, uncertainty, comorbidities; and (3) solutions, e.g., interdisciplinary, patient-centered approaches, communication, defined by the research group (JBL, SKJ, JLT, and MSR). The inspiration cards were developed based on previous findings from an audit held in general practice (unpublished material) and designed to illustrate the research group's understanding of management challenges experienced by patients and GPs when treating CMP. Finally, the case vignette and inspiration cards were tested for comprehension and relevancy with two GPs and two patients with CMP.

2.3.3 Procedure

The workshop was held in March 2022 at the facilities of the Center for General Practice in Aalborg East, Denmark. The workshop lasted approximately 3 h. Upon arrival, participants were divided into two workgroups of four people. The workshop activities were led by a workshop coordinator and external facilitator (SKJ), who presented the exercises, guided participants through the collaborative activities of the critique, fantasy, and implementation phases, and answered questions that arose during the workshop (Figure 1). During the first phase of critiquing, the facilitator presented the case and inspiration cards, which were available to assist the critique phase, and provided instructions on how to complete these workshop exercises. For the second phase of fantasying, the facilitator presented the inspiration cards available to assist this phase. During the third phase, participants were asked to continue to work with the available inspiration cards but change their focus to explore the implementation of their proposed solutions. Each workshop phase was concluded with a plenary discussion where the two groups would present the topics; they discussed with each other and received feedback. During the final phase of implementation, each group presented their visions for optimizing management for patients with CMP and received feedback from the facilitators and other participants.

2.3.4 Data collection

Participants' discussions were captured on audio recorders during the future workshop. The audio recordings from each workgroup were converted into two datasets using Express Scribe transcription software, while the NVivo 11 application was included to support the analysis of the data. The transcriptions were conducted with a focus on retaining the participants' meaning [26].

2.3.5 Data analysis

The data collected during the GP workshop were analyzed via Braun and Clarke’s [27] Reflective Thematic Analysis Approach by a research assistant (PB) as a lead analyzer in collaboration with two members of the research group (JBL and SKJ). The analysis followed a stepwise process, which included familiarization, coding, identification of semantic themes, generation of latent themes, and narrative production, guided by reflection and inductive reasoning [27]. The lead analyzer (PB) familiarized herself with the data during the transcription before briefing the other researchers (SKJ and JBL) on preliminary insights. The coding of the data was conducted using NVivo 11 coding software to organize the identified codes and relationships across datasets. A mind map and coding list were created and used to conduct stakeholder checks (SKJ) to ensure coding integrity through discussions of the generated codes. Semantic themes were developed iteratively through circles of coding, merging of codes, and inductive reasoning. Thematic overlaps and uncertainties were discussed between researchers (PB, JBL, and SKJ) in a collaborative and reflexive approach to ensure a nuanced interpretation of the data. The generated themes were organized, named, and renamed as the analysis progressed to generate latent themes. The analysis was finalized by the lead coder (PB), and the research group members identified four content summary themes that formed the narrative presented in Section 3.

3 Results

The future workshop consisted of eight participating GPs (five females). Four GPs worked in urban areas, and four GPs worked in rural areas. GPs have been working in general practice for an average of 16 years (individuals range from 1 to 32 years). The thematic analysis identified a system of four main themes titled: (1) challenges with current pain management, (2) barriers for pain management, (3) the need for a biopsychosocial perspective, and (4) solutions and visions, and 13 sub-themes concerning the challenges, needs, and possible solutions for optimizing the management of patients with CMP in general practice (Figure 2).

The themes and sub-themes identified during the analysis, and how these related to optimizing the care-pathway for CMP patients, which was a starting point for the thematic analysis.

4 Theme 1: Challenges with current pain management

The main theme 1 comprised of four sub-themes (Table 1). The GPs described the lack of time for a biopsychosocial approach and dialogue about the understanding and explanation of pain as a challenge. Still, the GPs agreed that receiving an understandable explanation for the pain was important to patients. All GPs described having experienced a need for assistance to support patients, regardless of whether they had a diagnosis or faced diagnostic uncertainty. Overall, diagnostic uncertainty was mentioned as a challenge and thought to reflect the complexity of the patients with CMP. Despite referrals to specialized departments, patients often return without a specific anatomical diagnosis. While several GPs described how they interpreted this as a sign that a shift toward a biopsychosocial approach was merited, patients would often keep asking for a biomedical reason for their pain, challenging the communication and support. Further, GPs generally agreed they lacked a “second opinion,” when specialized departments could not specify a diagnosis and diagnostic uncertainty arose. The GPs described having experienced patients being referred between specialists without regular GP follow-ups, leading to a lack of coherence in the examination of the patients. Consequently, several GPs highlighted how the patient and GP might not share the same understanding of the next steps necessary. This further challenged the support-based dialogue between the patient and the GP.

Sub-themes and illustrative quotes for the main theme “Challenges with current pain management”

| Sub-themes | Quotes |

|---|---|

| Complexity of the patient | D3: […] We know that you (the patient) have pain in your shoulder, and it is important that we remember that you do! But I also want to look at the other things (the association between pain and general living) and then piece it all together. |

| Communication and support | D7: […] I think it would be good to talk from the beginning with this patient group about how they are feeling on an entirely general level. I think this is being neglected in this patient group. And you also must think, that if you neglect it to begin with, well, then when you refer the patient, then the uncertainty just keeps growing. |

| Risk of non-coherent care pathways | D7: She (the patient) is just like a body that is simply transported from one department to another, but the patient also contains feelings, worries, and fears. She (the patient) probably contains fear too, it's just not something we know anything about. |

| Diagnostic uncertainty and the consequences | D4: […] The one thing that we need is someone acknowledged as an expert to tell her (the patient) or maybe help say that it's not like this, it's not biomechanically… There could be many other things. That is the one thing that we need! To get some validation and get help to become confident in our diagnostics. Because that's also what it's all about so that we don't have any doubts as to whether it could have been something else. |

5 Theme 2: Barriers to pain management

The main theme 2 identified four sub-themes (Table 2). The GPs explained how the patients often anticipated the GP to provide a biomedical explanation for their pain and how these expectations acted as a barrier toward educating patients on the psychological and social aspects of CMP management. Based on this observation, some GPs expressed concerns about whether an increased focus on psychosocial factors would make patients feel that their pain condition was not taken seriously or that the GP was incapable of resolving the patients' issues.

Sub-themes and illustrative quotes for the main theme “Barriers for pain management”

| Sub-themes | Quotes |

|---|---|

| Biomedical understanding of pain | D4: The healthcare system typically focuses on objective findings in anatomical structures… |

| D3: Yes, that is also particularly the patients focus. | |

| The patients working environment | D4: […] return to the origin for her pain, namely her workplace, her stress… It would be good if there was an opportunity to do something at her workplace and see if we could avoid her pain. |

| The GP in the midst of sectors and stakeholders | D2: […] but what we get from the hospital departments, there is often a lack of a prognosis or assessment of the prognosis, for the patient that you get back, about what they can and what they can't. And how long estimated time, based on your (hospital department) experience, will it take before the patient can get back (to work). |

| Lack of access to treatment | D5: […] Hospital departments have the advantage that they can refer the patient to (free-of-charge) rehabilitation at the municipality and we GPs cannot. |

The GPs agreed that the patients' working environment and stress-related pain could be a contextual barrier to the management of their CMP. The patient's perspective on their job situation was highlighted as a contributing factor in maintaining their CMP. If the patients' work-related challenges were not addressed and adjusted to their CMP, maintaining employment could become a barrier to their pain management. However, some GPs stated that it was difficult for them to influence the patients' working conditions, as some patients acted without consulting their GP, while others refrained from expressing their need for work adjustments with employers because of fear of being fired. The GPs highlighted that the fear of engaging in a workplace dialogue was a barrier, as patients, therefore, perceived sick leave as the only solution to overcoming their CMP.

Several GPs described being asked to estimate return-to-work time frames regardless of whether patients had a diagnosis or experienced diagnostic uncertainty. The GPs experienced that they often had to do so without support from the specialized departments. This was described as a challenge and a potential barrier for managing patient's chronic pain as the GPs felt caught in the middle of all stakeholders.

The GPs acknowledged how patients with diagnostic uncertainty had similar needs for support and treatment as patients with a specific diagnosis and a clear care pathway. However, some GPs highlighted how access to limited free-of-charge treatment options like physiotherapy- or municipality-based treatments was restricted for patients without a clear diagnosis. Some patients lacked the financial opportunities to prioritize physiotherapy, medicine, and, e.g., psychological treatment. Therefore, the financial burden was described as another potential barrier to adequate pain management.

6 Theme 3: The need for a biopsychosocial perspective

The main theme 3 comprised two sub-themes (Table 3). The GPs envisioned a need for an early focus on biopsychosocial factors. Since the GPs generally considered the patient's complex CMP as being influenced by psychosocial factors to some extent, they believed it would enhance the management to bring attention to such factors from an early point. However, several GPs underlined that they should continue to screen for somatic causes of pain. This could include a focus on the patient's domestic and family conditions as well as the situation at work.

Sub-themes and illustrative quotes for the main theme “The need for a biopsychosocial perspective”

| Sub-themes | Quotes |

|---|---|

| Early focus required | D5: […] The GP must focus on two tracks for the examination of the pain condition, both on the somatic and the psychosocial aspects. |

| The importance of psychological and social factors | D6: […] What else is going on in her (the patient) life and who helps her manage the symptoms that arises. |

The GPs highlighted how contextual circumstances in the patient's environment and life should be considered, e.g., how stress at home or work could influence patients' pain experience. The GPs described patients' fear of losing their work due to pain-related limitations or balancing family matters while managing their pain as sources of psychological stress experienced by patients with CMP. Furthermore, several GPs highlighted how they perceived the lack of understanding and acceptance of the patient's pain and limitations from their relatives as something that could influence pain management.

7 Theme 4: Solutions and visions

The main theme 4 identified three sub-themes (Table 4). The GPs agreed that there exists a need for an interdisciplinary approach when managing patients with complex CMP. They described that a more explicit collaboration between the GPs and an interdisciplinary unit could facilitate a cohesive examination and management. Additionally, GPs envisioned that an interdisciplinary unit should consist of specialists from both the biomedical and psychosocial fields, e.g., orthopedic surgeons, rheumatologists, occupational medicine, physiotherapists, psychologists, or social workers. This was stressed as important for targeting the individual needs and challenges of the patients.

Sub-themes and illustrative quotes for the main theme “Solutions and visions”

| Sub-themes | Quotes |

|---|---|

| Interdisciplinary approach | D4: […] We dream of some interdisciplinary place where we can refer patients in such a situation (diagnostic uncertainty), because that is what we are saying we need. |

| Coherence | D3: But sometimes it would be good if we don't first send to the X-ray, then to the orthopedic surgeon and then to the physiotherapist, but if we could unify. We could refer to a comprehensive examination if we (the GPs) consider this to be a long-term problem. |

| Concerns | D2: If I were to get worried about something … It could be if it (the interdisciplinary approach) ends up in changing medication (for the patient) and I then have to take over … I would just be afraid that if you had such a (interdisciplinary) department that the patient would come back with prescription for Contalgin or even worse, yes. |

The GPs emphasized how the interdisciplinary unit should focus on a biopsychosocial approach and make sure adequate time was allocated to consider these elements of the patient's pain. Further, they highlighted that an interdisciplinary unit could enhance the focus on pain management instead of the patients' focus on pain manifestations. The GPs suggested that improved coherence in the management of patients with CMP should be a priority. They believed that initiating several examinations at the same time could contribute to a more efficient process for this patient group, again highlighting the value of an interdisciplinary approach, where multiple examinations and factors could be considered simultaneously. The GPs stressed that they should still be coordinating the patients' treatments and pain management, thereby making coordination and communication between the GP and the specialized sector important. To improve and enhance coherence, the GPs suggested that teleconferences could be used to establish a dialogue between an interdisciplinary unit and the GP.

The GPs suggested that it could be of value to involve the municipality about possible assistance and treatment from, e.g., the rehabilitation centers, the center for mental health, or social workers. Thereby, the patient would be supported by their GP and other stakeholders.

Despite a general enthusiasm about the possible solutions, the GPs also voiced some concerns. The GPs were concerned that an interdisciplinary unit would include too much focus on pain medication and deprioritize other examinations or focus areas. The GPs agreed that it would be a barrier for them to refer patients to an interdisciplinary unit that focused on the patient's medication. Furthermore, GPs expressed that they should be coordinating the patient's medication, and an interdisciplinary unit should assist with a greater focus on biopsychosocial elements and other perspectives in the examination. A concern was raised regarding the need for a “second opinion” as a matter of routine. The GPs feared that their assessment, therefore, would not be considered sufficient by the patient and a need for a specialist team was required. Conversely, other GPs highlighted how it might be necessary to include a “second opinion” to meet the patients' expectation of a biomedical examination and ensure that possible diagnostic uncertainty is not because the patients have not been thoroughly examined.

8 Discussion

The study aimed to investigate GPs' perspectives on the challenges, needs, and solutions when managing patients with CMP to inform the improvement of the care pathway. The findings from the future workshop revealed that the diagnostic uncertainty related to this patient population was considered a challenge and frequently led to multiple referrals from the GP to the specialized secondary sector. The GPs perceived that the patients often sought a biomedical explanation for their CMP, which was considered a challenge for addressing the possible psychological and social factors related to managing the patients' CMP. The GPs highlighted how patients with CMP would ask specific questions on, e.g., return-to-work time frame, which they felt ill-equipped to answer, and how adapting an early focus on psychological and social factors contributing to the CMP experience could help address such issues during consultations. Finally, our participants envisioned how having the option of referring patients to an interdisciplinary unit, which could explore an interdisciplinary and biopsychosocial approach, provide GPs with a "second opinion" to alleviate diagnostic uncertainty and reduce unnecessary referrals back-and-forth.

Diagnostic uncertainty has been proposed as a challenge for providing adequate management and often results in delayed treatment of the patient's condition [16,28]. Similarly, our findings reflect that the GPs experience diagnostic uncertainty as a challenge for both the GP and the patient. The GPs request the possibility of getting a “second opinion” if in doubt about the diagnosis or when facing diagnostic uncertainty. First, such a setup could possibly diminish the diagnostic uncertainty and ensure that the patient feels adequately examined and that a correct diagnosis has been identified. Second, it could be part of the initial steps toward the patients’ recognizing that other factors besides the biomedical aspects are involved in the complex CMP experience. As such, research studies have recommended a biopsychosocial management approach to fully encompass the entire experience of CMP [18,29,30]. Our findings align with this and highlight that GPs consider an early focus on biopsychosocial factors important. However, the GPs refer to the challenge of patients often having a biomedical view of their CMP and expecting an anatomical explanation for their pain. This could create a mismatch between the patient's expectations and the GPs' broader insight that enables them to consider a biopsychosocial approach. The GPs mention that patients, apart from the biomedical view, can lack the understanding of how, e.g., their working conditions can influence their CMP. The GPs perceive that a thorough, interdisciplinary examination could be the turning point where the patient starts to feel adequately diagnosed to consider other contributing factors and engage in management options. Thereby, an interdisciplinary unit could become the catalyst for improved dialogue and support between the patient and the GP.

GPs state that an interdisciplinary unit should consist of orthopedic surgeons, rheumatologists, occupational medicine, physiotherapists, psychologists, and social workers. Their suggestions include healthcare practitioners who can consider the biomedical and psychological factors, as well as social workers, to assist with social factors. There are some discrepancies compared to suggestions from the literature that highlight the inclusion of a pain psychologist, pain physician, psychiatrist, nutritionist, physiotherapist, and pain nurse, enabling more focus on pain medication skills [30,31]. The discrepancy could be explained by the statements from the GPs, describing how they prefer to coordinate the patients' pain medication and using the interdisciplinary unit to focus on the psychosocial factors contributing to the complex CMP. Overall, both GPs in the present study and the literature underline that the interdisciplinary unit of healthcare practitioners should be specific to the individual patient's needs.

The challenges and gaps in the current care pathways for patients with CMP have been recognized, both nationally and internationally [11,12,18]. The current setup relies on the GPs singlehandedly managing the patients with complex CMP or referring the patients to different specialized departments in the quest for an anatomical cause for the pain. This leads to an overuse of imaging, usage of opioids and surgery, and a lack of patient education concerning the management of CMP [29,31]. This underlines the urgent need to revise the current setup, a statement that has been backed by patients [14]. The GPs suggest reframing the current setup and moving on to propose possible solutions. They want to be in charge of coordinating the management of the patients with complex CMP, but they request coherent inputs from the healthcare system to improve the management of this complex patient population. Therefore, the GPs envision an interdisciplinary unit that could fight the diagnostic uncertainty they face in general practice and simultaneously be a focal point for introducing a biopsychosocial approach for examination and management of the patient's pain. To bridge the knowledge between an interdisciplinary unit and the coordinating GP and enhance the care pathway for the patient, it is imperative to ensure coherence and communication between these sectors. The GPs propose teleconferences as a tool to enhance the communication between an interdisciplinary unit and the GP.

To fulfill the ambitions of providing an interdisciplinary unit of healthcare practitioners that will embark upon a biopsychosocial examination, several things need to be considered to provide a setup that will improve the management of patients with complex CMP. This includes deciding which healthcare practitioners should be included in an interdisciplinary unit so that the competencies match the patient's needs. It should also be considered how an interdisciplinary unit should implement the biopsychosocial approach, including how to prioritize psychosocial factors equally to the biomedical factors but still taking the patients' judgment of an anatomical structure as the explanation for their complex CMP into account.

The main solution derived from the workshop was the proposal of a multidisciplinary unit to examine patients with complex CMP. However, such a solution is not without challenges. A multidisciplinary unit would require that various specialized healthcare professionals (e.g., orthopedic surgeons, rheumatologists, and physiotherapists) would be interested in a mutual examination of the patient and merging the clinical findings into a conclusion. Given the high specialization of the individual healthcare professions, it could be challenging to combine these competencies into a comprehensive and inclusive setup. Yet, the possible benefits of establishing a coherent examination in one session compared to frequent referrals back-and-forth are appealing. Similarly, a multidisciplinary setup would come with increased costs compared to the patient seeing only one healthcare professional. However, compared to patients being referred to various healthcare professionals one at a time, the multidisciplinary setup could prove to be cost-effective. Initiation of a multidisciplinary unit would introduce the challenge of establishing which patients should be referred for a more comprehensive care pathway. Within low back pain, stratified care models have been used in general practice to guide treatment direction based on a prediction of which patients need a more comprehensive approach [32]. The stratified care approach to determine treatment decisions has been shown to provide improved treatment efficiency and patient satisfaction, and be cost-effective in patients with low back pain compared to a usual care approach [33]. However, when using a stratified care model for patients with common musculoskeletal (i.e., back, neck, knee, shoulder, and multi-site) pain, no differences in pain or function were observed between the stratified care and the usual care [34]. This could illustrate that it might be a challenge to be able to select patients with general musculoskeletal pain for the more comprehensive care pathway. However, it should be noted that the aforementioned studies focus on stratified treatment and not examination, as suggested by our workshop participants.

Several strengths and weaknesses were identified during this study, which should be considered when interpreting the results. One strength is related to the focus on GPs' experience of management of patients with CMP, rather than pain localized in specific bodily regions, e.g., low back pain or neck pain, resulting in a clearer picture of the challenges and barriers related to treating CMP in general practice. We included GPs working in clinical practice, and our findings are expected to be rooted in clinical practice and reflect the experiences of general practice in this region of Denmark. There may be different referral pathways in other countries, which limits the generalization of our findings to other healthcare systems than Denmark. We included GPs based on an open call. Thus, we anticipate that GPs who signed up for the workshop have a higher interest in CMP compared to other GPs [35], leading to more novel and relevant insights. Future workshops utilize participants' experiences and co-construction of knowledge as a driver for extracting future visions, which makes the workshop process vulnerable to say-do and social desirability bias [36]. Furthermore, by including insights gained during our previous audit and inspiration cards with themes identified by the author group, we risked imposing our ideas on participants, resulting in alternative topics that might have been missed during discussions. To address this limitation, special care was taken to ensure that inspiration card themes were open, participants were encouraged to add new cards, and workshop facilitators asked open questions during plenary discussions to alleviate this issue. Finally, since only one workshop was held, it remains unclear if all aspects of the topic have been uncovered, which should be viewed as a limitation when reviewing the findings.

9 Conclusions

Patients with complex CMP are a challenge for the current healthcare setup. GPs, frequently being the first point-of-contact for the patients, experience diagnostic uncertainty, and a patient preference for considering an anatomical explanation for their CMP remains a challenge in general practice. The GPs want to be the coordinators for this patient population but request a more coherent setup than the current possibilities of referring patients back-and-forth between specialized departments for examinations, often focusing on biomedical aspects of the CMP.

To improve the management of patients with complex CMP, the GPs recommend introducing an interdisciplinary unit to combat diagnostic uncertainty and to take the biopsychosocial factors into account. A thorough communication between the GP and an interdisciplinary unit should be enabled, possible by using teleconferences, to ensure coherence between sectors. Future studies should address the feasibility and effectiveness of an interdisciplinary unit and the coherent collaboration between the patient and the GP.

Acknowledgments

The Center for General Practice is acknowledged for its administrative and logistic support before the future workshop. All participating GPs are thanked for their contributions during the future workshop. Morten Ohrt is thanked for his input and assistance in the recruitment of GPs. Camilla Ulfkjær Østergaard is acknowledged and thanked for her contributions and facilitation during the future workshop. JBL acknowledges to have received an educational program grant by the Association of Danish Physiotherapists.

-

Research ethics: The study was submitted to the North Denmark Region Committee on Health Research Ethics, which ruled the project was exempt from registration.

-

Informed consent: All participants signed an informed consent as part of participating in the workshops.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Competing interests: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: The study received funding from Nord-KAP for the expenses related to hosting the workshop. The study funder was not involved in interpreting the data or publishing the results.

-

Data availability: Not applicable.

Appendix S1 Case for future workshops concerning patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain

Jonna is 59 years old and lives in the North Region of Denmark. She is married and lives with her husband. She is overweight and has a BMI of 28.5. She walks the dog a few times a day but has started to take shorter walks as she often feels tired and does not have the energy to walk. She is employed as a kindergarten teacher but is now absent owing to illness and has been on sick leave for 8 weeks. She has worked in the kindergarten for the past 8 years and is happy with her work, although she thinks that more children have arrived despite there being fewer personnel in the institution.

This has sometimes resulted in stressful working days, and she has regularly had headaches when she got off work. About a year and a half ago, she started having pain in her neck and left shoulder. The pain came without any specific trigger. She experienced that her neck was “stiff” and “ached” when she moved her head. Her left shoulder caused pain when she had to lift heavy things or children. In the following months, the pain got worse. On the worst days, she had to call in sick or go home earlier from work, but she tried to “hang in there” as she did not want to put her colleagues in a situation where they had to cover for her absence. Eventually, she could not cope with it anymore and saw no other option than to go on sick leave from her job. The 8 weeks of sick leave have not led to an improvement in her condition. She continues to experience pain in the neck and shoulder, and sometimes, the right shoulder also hurts. She has difficulty putting into words what triggers her pain and does not know “what’s up and down” of the pain. She has consulted her general practitioner (GP) several times during the 6 months she has had the pain. The doctor believed that it was “neck–shoulder tension,” and she was given weak painkillers, which briefly “took the edge off the pain.” When the pain continued, she was referred to an orthopedic surgeon. The X-ray showed subtle signs of degenerative changes in the shoulder and neck, but there was no indication of surgical intervention. Instead, Jonna was prescribed NSAID and referred to the hospital's physiotherapy department. Here, she was instructed on some exercises for the neck and shoulder. She tried to do the exercises at home but experienced that the exercises often made her pain worse. She continued training “to the best of her ability” but fears that she is doing more harm than good. Once again, Jonna now turns to her GP for help with her situation. She is nervous about whether she risks being fired and the job center in the municipality has summoned her to a follow-up interview due to her sick leave. She is insecure about what this entails and fears being forced back into work. She is afraid that the pain will worsen if she resumes her job, and she does not think she can “keep up with the demands” she is exposed to at work.

S2 Examples of inspiration cards used during the future workshop

The images are from Colourbox and are brought with permission.

The images are from Colourbox and are brought with permission.

References

[1] Borchgrevink PC, Glette M, Woodhouse A, Butler S, Landmark T, Romundstad P, et al. A clinical description of chronic pain in a general population using ICD-10 and ICD-11 (The HUNT pain examination study). J Pain. 2022;23:337–48.10.1016/j.jpain.2021.08.007Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[2] Aili K, Campbell P, Michaleff ZA, Zoe AM, Vicky TS, Kelvin PJ, Bremander A, et al. Long-term trajectories of chronic musculoskeletal pain: a 21-year prospective cohort latent class analysis. Pain. 2021;162:1511–20.10.1097/j.pain.0000000000002137Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[3] Treede RD, Rief W, Barke A, Aziz Q, Bennett M, Benoliel R, et al. Chronic pain as a symptom or a disease: the IASP classification of chronic pain for the international classification of diseases (ICD-11). Pain. 2019;160:19–27.10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001384Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[4] GBD. Disease and Injury Incidence and PC. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 328 diseases and injuries for 195 countries, 1990-2016: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet. 2016;390:1211–59.Search in Google Scholar

[5] Hartvigsen J, Davidsen M, Hestbaek L, Sogaard K, Roos EM. Patterns of musculoskeletal pain in the population: A latent class analysis using a nationally representative interviewer-based survey of 4817 Danes. Eur J Pain. 2013;17:452–60.10.1002/j.1532-2149.2012.00225.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] Artus M, Campbell P, Mallen CD, Dunn K, van der Windt D. Generic prognostic factors for musculoskeletal pain in primary care: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e012901.10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012901Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[7] Turk DC, Fillingim RB, Ohrbach R, Patel K. Assessment of Psychosocial and Functional Impact of Chronic Pain. J Pain. 2016;17:T21–49.10.1016/j.jpain.2016.02.006Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[8] Jensen HI, Plesner K, Kvorning N, Krogh B, Kimper-Karl A. Associations between demographics and health-related quality of life for chronic non-malignant pain patients treated at a multidisciplinary pain centre: a cohort study. Int J Qual Health Care. 2016;28:86–91.10.1093/intqhc/mzv108Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] Mose S, Kent P, Smith A, Andersen J, Christiansen D. Trajectories of Musculoskeletal Healthcare Utilization of People with Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain – A Population-Based Cohort Study. Clin Epidemiol. 2021;13:825–43.10.2147/CLEP.S323903Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[10] Mose S, Kent P, Smith A, Christiansen D. Number of musculoskeletal pain sites leads to increased long-term healthcare contacts and healthcare related costs – a Danish population-based cohort study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21:980.10.1186/s12913-021-06994-0Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[11] Danish Health Authority. National klinisk retningslinje for udredning og behandling samt rehabilitering af patienter med generaliserede smerter i bevægeapparatet. København: Sundhedsstyrelsen, 2018.Search in Google Scholar

[12] Lewis J, O’Sullivan P. Is it time to reframe how we care for people with non-traumatic musculoskeletal pain? Br J Sports Med. 2018;52:1543–4.10.1136/bjsports-2018-099198Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[13] Ryan S, Hassell A, Thwaites C, Manley K, Home D. Developing a new model of care for patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain. J Nurs Manag. 2007;15:825–9.10.1111/j.1365-2934.2007.00761.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[14] Gleadhill C, Kamper SJ, Lee H, Williams C. Exploring integrated care for musculoskeletal and chronic health conditions. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2021;51:264–8.10.2519/jospt.2021.10428Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[15] Lyng KD, Larsen JB, Birnie KA, Stinson J, Hoegh M, Pallson T, et al. Participatory research: a Priority Setting Partnership for chronic musculoskeletal pain in Denmark. Scand J Pain. 2022;23:402–15.10.1515/sjpain-2022-0019Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[16] Dahm MR, Cattanach W, Williams M, Basseal J, Gleason K, Crock C. Communication of Diagnostic Uncertainty in Primary Care and Its Impact on Patient Experience: an Integrative Systematic Review. J Gen Intern Med. 2023;38:738–54.10.1007/s11606-022-07768-ySearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[17] Cox CL, Miller BM, Kuhn I, Fritz Z. Diagnostic uncertainty in primary care: what is known about its communication, and what are the associated ethical issues? Fam Pract. 2021;38:654–68.10.1093/fampra/cmab023Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[18] Caneiro JP, Roos EM, Barton CJ, O‘Sullivan K, Kent P, Lin I, et al. It is time to move beyond ‘body region silos’ to manage musculoskeletal pain: five actions to change clinical practice. Br J Sports Med. 2020;54:438–9.10.1136/bjsports-2018-100488Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[19] Baskerville R, Wood-Harper AT. Diversity in information systems action research methods. Eur J Inf Syst. 1998;7:90–107.10.1038/sj.ejis.3000298Search in Google Scholar

[20] Hearn G, Foth M, Gray H. Applications and implementations of new media in corporate communications: An action research approach. Corp Commun. 2009;14:49–61.10.1108/13563280910931072Search in Google Scholar

[21] Apel H. The Future Workshop, https://www.die-bonn.de/id/1001/about/html (2004, accessed 13 March 2023).Search in Google Scholar

[22] Halskov K, Dalsgård P. Inspiration card workshops. Proceedings of the Conference on Designing Interactive Systems: Processes, Practices, Methods, and Techniques, DIS. 2006; 2006. p. 2–11.10.1145/1142405.1142409Search in Google Scholar

[23] Kathiresan J, Patro BK. Case vignette: a promising complement to clinical case presentations in teaching. Educ Health. 2013;26:21–4.10.4103/1357-6283.112796Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[24] Braun V, Clarke V. Thematic analysis. APA handbook of research methods in psychology. Research designs: Quantitative, qualitative, neuropsychological, and biological. Vol. 2. Washington: American Psychological Association; 2012. p. 57–71.10.1037/13620-004Search in Google Scholar

[25] Vidal RVV. The Future Workshop: Democratic problem solving. Econ Anal Work Pap. 2006;5:1–25.Search in Google Scholar

[26] Kvale S, Brinkmann S. Interviews: Learning the craft of qualitative research interviewing. Sage Publications Inc; 2009.Search in Google Scholar

[27] Braun V, Clarke V. Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qual Res Sport Exerc Health. 2019;11:589–97.10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806Search in Google Scholar

[28] McKoane A, Sherman DK. Diagnostic uncertainty in patients, parents, and physicians: a compensatory control theory perspective. Health Psychol Rev. 2023;17:439–55.10.1080/17437199.2022.2086899Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[29] Lin I, Wiles L, Waller R, Goucke R, Nagree Y, Gibberd M, et al. What does best practice care for musculoskeletal pain look like? Eleven consistent recommendations from high-quality clinical practice guidelines: systematic review. Br J Sports Med. 2020;54:79–86.10.1136/bjsports-2018-099878Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[30] Mallick-Searle T, Sharma K, Toal P, Gutman A. Pain and function in chronic musculoskeletal pain-treating the whole person. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2021;14:335–47.10.2147/JMDH.S288401Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[31] El-Tallawy SN, Nalamasu R, Salem GI, LeGuang J, Pergolizzi J, Christo P. Management of musculoskeletal pain: an update with emphasis on chronic musculoskeletal pain. Pain Ther. 2021;10:181.10.1007/s40122-021-00235-2Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[32] Kongsted A, Kent P, Quicke JG, Skou S, Hill J. Risk-stratified and stepped models of care for back pain and osteoarthritis: are we heading towards a common model? Pain Rep. 2020;5:e843.10.1097/PR9.0000000000000843Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[33] Hill JC, Whitehurst DGT, Lewis M, Bryan S, Dunn K, Foster N, et al. Comparison of stratified primary care management for low back pain with current best practice (STarT Back): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2011;378:1560.10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60937-9Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[34] Hill JC, Garvin S, Bromley K, Saunders B, Kigozi J, Cooper V, et al. Risk-based stratified primary care for common musculoskeletal pain presentations (STarT MSK): a cluster-randomised, controlled trial. Lancet Rheumatol. 2022;4:e591–e602.10.1016/S2665-9913(22)00159-XSearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[35] von Hippel E. Lead Users: A Source of Novel Product Concepts. Manage Sci. 1986;32:791–805.10.1287/mnsc.32.7.791Search in Google Scholar

[36] Bergen N, Labonté R. ‘Everything Is Perfect, and We Have No Problems’: Detecting and Limiting Social Desirability Bias in Qualitative Research. Qual Health Res. 2020;30:783–92.10.1177/1049732319889354Search in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Editorial Comment

- From pain to relief: Exploring the consistency of exercise-induced hypoalgesia

- Christmas greetings 2024 from the Editor-in-Chief

- Original Articles

- The Scandinavian Society for the Study of Pain 2022 Postgraduate Course and Annual Scientific (SASP 2022) Meeting 12th to 14th October at Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen

- Comparison of ultrasound-guided continuous erector spinae plane block versus continuous paravertebral block for postoperative analgesia in patients undergoing proximal femur surgeries

- Clinical Pain Researches

- The effect of tourniquet use on postoperative opioid consumption after ankle fracture surgery – a retrospective cohort study

- Changes in pain, daily occupations, lifestyle, and health following an occupational therapy lifestyle intervention: a secondary analysis from a feasibility study in patients with chronic high-impact pain

- Tonic cuff pressure pain sensitivity in chronic pain patients and its relation to self-reported physical activity

- Reliability, construct validity, and factorial structure of a Swedish version of the medical outcomes study social support survey (MOS-SSS) in patients with chronic pain

- Hurdles and potentials when implementing internet-delivered Acceptance and commitment therapy for chronic pain: a retrospective appraisal using the Quality implementation framework

- Exploring the outcome “days with bothersome pain” and its association with pain intensity, disability, and quality of life

- Fatigue and cognitive fatigability in patients with chronic pain

- The Swedish version of the pain self-efficacy questionnaire short form, PSEQ-2SV: Cultural adaptation and psychometric evaluation in a population of patients with musculoskeletal disorders

- Pain coping and catastrophizing in youth with and without cerebral palsy

- Neuropathic pain after surgery – A clinical validation study and assessment of accuracy measures of the 5-item NeuPPS scale

- Translation, contextual adaptation, and reliability of the Danish Concept of Pain Inventory (COPI-Adult (DK)) – A self-reported outcome measure

- Cosmetic surgery and associated chronic postsurgical pain: A cross-sectional study from Norway

- The association of hemodynamic parameters and clinical demographic variables with acute postoperative pain in female oncological breast surgery patients: A retrospective cohort study

- Healthcare professionals’ experiences of interdisciplinary collaboration in pain centres – A qualitative study

- Effects of deep brain stimulation and verbal suggestions on pain in Parkinson’s disease

- Painful differences between different pain scale assessments: The outcome of assessed pain is a matter of the choices of scale and statistics

- Prevalence and characteristics of fibromyalgia according to three fibromyalgia diagnostic criteria: A secondary analysis study

- Sex moderates the association between quantitative sensory testing and acute and chronic pain after total knee/hip arthroplasty

- Tramadol-paracetamol for postoperative pain after spine surgery – A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study

- Cancer-related pain experienced in daily life is difficult to communicate and to manage – for patients and for professionals

- Making sense of pain in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD): A qualitative study

- Patient-reported pain, satisfaction, adverse effects, and deviations from ambulatory surgery pain medication

- Does pain influence cognitive performance in patients with mild traumatic brain injury?

- Hypocapnia in women with fibromyalgia

- Application of ultrasound-guided thoracic paravertebral block or intercostal nerve block for acute herpes zoster and prevention of post-herpetic neuralgia: A case–control retrospective trial

- Translation and examination of construct validity of the Danish version of the Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia

- A positive scratch collapse test in anterior cutaneous nerve entrapment syndrome indicates its neuropathic character

- ADHD-pain: Characteristics of chronic pain and association with muscular dysregulation in adults with ADHD

- The relationship between changes in pain intensity and functional disability in persistent disabling low back pain during a course of cognitive functional therapy

- Intrathecal pain treatment for severe pain in patients with terminal cancer: A retrospective analysis of treatment-related complications and side effects

- Psychometric evaluation of the Danish version of the Pain Self-Efficacy Questionnaire in patients with subacute and chronic low back pain

- Dimensionality, reliability, and validity of the Finnish version of the pain catastrophizing scale in chronic low back pain

- To speak or not to speak? A secondary data analysis to further explore the context-insensitive avoidance scale

- Pain catastrophizing levels differentiate between common diseases with pain: HIV, fibromyalgia, complex regional pain syndrome, and breast cancer survivors

- Prevalence of substance use disorder diagnoses in patients with chronic pain receiving reimbursed opioids: An epidemiological study of four Norwegian health registries

- Pain perception while listening to thrash heavy metal vs relaxing music at a heavy metal festival – the CoPainHell study – a factorial randomized non-blinded crossover trial

- Observational Studies

- Cutaneous nerve biopsy in patients with symptoms of small fiber neuropathy: a retrospective study

- The incidence of post cholecystectomy pain (PCP) syndrome at 12 months following laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a prospective evaluation in 200 patients

- Associations between psychological flexibility and daily functioning in endometriosis-related pain

- Relationship between perfectionism, overactivity, pain severity, and pain interference in individuals with chronic pain: A cross-lagged panel model analysis

- Access to psychological treatment for chronic cancer-related pain in Sweden

- Validation of the Danish version of the knowledge and attitudes survey regarding pain

- Associations between cognitive test scores and pain tolerance: The Tromsø study

- Healthcare experiences of fibromyalgia patients and their associations with satisfaction and pain relief. A patient survey

- Video interpretation in a medical spine clinic: A descriptive study of a diverse population and intervention

- Role of history of traumatic life experiences in current psychosomatic manifestations

- Social determinants of health in adults with whiplash associated disorders

- Which patients with chronic low back pain respond favorably to multidisciplinary rehabilitation? A secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial

- A preliminary examination of the effects of childhood abuse and resilience on pain and physical functioning in patients with knee osteoarthritis

- Differences in risk factors for flare-ups in patients with lumbar radicular pain may depend on the definition of flare

- Real-world evidence evaluation on consumer experience and prescription journey of diclofenac gel in Sweden

- Patient characteristics in relation to opioid exposure in a chronic non-cancer pain population

- Topical Reviews

- Bridging the translational gap: adenosine as a modulator of neuropathic pain in preclinical models and humans

- What do we know about Indigenous Peoples with low back pain around the world? A topical review

- The “future” pain clinician: Competencies needed to provide psychologically informed care

- Systematic Reviews

- Pain management for persistent pain post radiotherapy in head and neck cancers: systematic review

- High-frequency, high-intensity transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation compared with opioids for pain relief after gynecological surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis

- Reliability and measurement error of exercise-induced hypoalgesia in pain-free adults and adults with musculoskeletal pain: A systematic review

- Noninvasive transcranial brain stimulation in central post-stroke pain: A systematic review

- Short Communications

- Are we missing the opioid consumption in low- and middle-income countries?

- Association between self-reported pain severity and characteristics of United States adults (age ≥50 years) who used opioids

- Could generative artificial intelligence replace fieldwork in pain research?

- Skin conductance algesimeter is unreliable during sudden perioperative temperature increases

- Original Experimental

- Confirmatory study of the usefulness of quantum molecular resonance and microdissectomy for the treatment of lumbar radiculopathy in a prospective cohort at 6 months follow-up

- Pain catastrophizing in the elderly: An experimental pain study

- Improving general practice management of patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain: Interdisciplinarity, coherence, and concerns

- Concurrent validity of dynamic bedside quantitative sensory testing paradigms in breast cancer survivors with persistent pain

- Transcranial direct current stimulation is more effective than pregabalin in controlling nociceptive and anxiety-like behaviors in a rat fibromyalgia-like model

- Paradox pain sensitivity using cuff pressure or algometer testing in patients with hemophilia

- Physical activity with person-centered guidance supported by a digital platform or with telephone follow-up for persons with chronic widespread pain: Health economic considerations along a randomized controlled trial

- Measuring pain intensity through physical interaction in an experimental model of cold-induced pain: A method comparison study

- Pharmacological treatment of pain in Swedish nursing homes: Prevalence and associations with cognitive impairment and depressive mood

- Neck and shoulder pain and inflammatory biomarkers in plasma among forklift truck operators – A case–control study

- The effect of social exclusion on pain perception and heart rate variability in healthy controls and somatoform pain patients

- Revisiting opioid toxicity: Cellular effects of six commonly used opioids

- Letter to the Editor

- Post cholecystectomy pain syndrome: Letter to Editor

- Response to the Letter by Prof Bordoni

- Response – Reliability and measurement error of exercise-induced hypoalgesia

- Is the skin conductance algesimeter index influenced by temperature?

- Skin conductance algesimeter is unreliable during sudden perioperative temperature increase

- Corrigendum

- Corrigendum to “Chronic post-thoracotomy pain after lung cancer surgery: a prospective study of preoperative risk factors”

- Obituary

- A Significant Voice in Pain Research Björn Gerdle in Memoriam (1953–2024)

Articles in the same Issue

- Editorial Comment

- From pain to relief: Exploring the consistency of exercise-induced hypoalgesia

- Christmas greetings 2024 from the Editor-in-Chief

- Original Articles

- The Scandinavian Society for the Study of Pain 2022 Postgraduate Course and Annual Scientific (SASP 2022) Meeting 12th to 14th October at Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen

- Comparison of ultrasound-guided continuous erector spinae plane block versus continuous paravertebral block for postoperative analgesia in patients undergoing proximal femur surgeries

- Clinical Pain Researches

- The effect of tourniquet use on postoperative opioid consumption after ankle fracture surgery – a retrospective cohort study

- Changes in pain, daily occupations, lifestyle, and health following an occupational therapy lifestyle intervention: a secondary analysis from a feasibility study in patients with chronic high-impact pain

- Tonic cuff pressure pain sensitivity in chronic pain patients and its relation to self-reported physical activity

- Reliability, construct validity, and factorial structure of a Swedish version of the medical outcomes study social support survey (MOS-SSS) in patients with chronic pain

- Hurdles and potentials when implementing internet-delivered Acceptance and commitment therapy for chronic pain: a retrospective appraisal using the Quality implementation framework

- Exploring the outcome “days with bothersome pain” and its association with pain intensity, disability, and quality of life

- Fatigue and cognitive fatigability in patients with chronic pain

- The Swedish version of the pain self-efficacy questionnaire short form, PSEQ-2SV: Cultural adaptation and psychometric evaluation in a population of patients with musculoskeletal disorders

- Pain coping and catastrophizing in youth with and without cerebral palsy

- Neuropathic pain after surgery – A clinical validation study and assessment of accuracy measures of the 5-item NeuPPS scale

- Translation, contextual adaptation, and reliability of the Danish Concept of Pain Inventory (COPI-Adult (DK)) – A self-reported outcome measure

- Cosmetic surgery and associated chronic postsurgical pain: A cross-sectional study from Norway

- The association of hemodynamic parameters and clinical demographic variables with acute postoperative pain in female oncological breast surgery patients: A retrospective cohort study

- Healthcare professionals’ experiences of interdisciplinary collaboration in pain centres – A qualitative study

- Effects of deep brain stimulation and verbal suggestions on pain in Parkinson’s disease

- Painful differences between different pain scale assessments: The outcome of assessed pain is a matter of the choices of scale and statistics

- Prevalence and characteristics of fibromyalgia according to three fibromyalgia diagnostic criteria: A secondary analysis study

- Sex moderates the association between quantitative sensory testing and acute and chronic pain after total knee/hip arthroplasty

- Tramadol-paracetamol for postoperative pain after spine surgery – A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study

- Cancer-related pain experienced in daily life is difficult to communicate and to manage – for patients and for professionals

- Making sense of pain in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD): A qualitative study

- Patient-reported pain, satisfaction, adverse effects, and deviations from ambulatory surgery pain medication

- Does pain influence cognitive performance in patients with mild traumatic brain injury?

- Hypocapnia in women with fibromyalgia

- Application of ultrasound-guided thoracic paravertebral block or intercostal nerve block for acute herpes zoster and prevention of post-herpetic neuralgia: A case–control retrospective trial

- Translation and examination of construct validity of the Danish version of the Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia

- A positive scratch collapse test in anterior cutaneous nerve entrapment syndrome indicates its neuropathic character

- ADHD-pain: Characteristics of chronic pain and association with muscular dysregulation in adults with ADHD

- The relationship between changes in pain intensity and functional disability in persistent disabling low back pain during a course of cognitive functional therapy

- Intrathecal pain treatment for severe pain in patients with terminal cancer: A retrospective analysis of treatment-related complications and side effects

- Psychometric evaluation of the Danish version of the Pain Self-Efficacy Questionnaire in patients with subacute and chronic low back pain

- Dimensionality, reliability, and validity of the Finnish version of the pain catastrophizing scale in chronic low back pain

- To speak or not to speak? A secondary data analysis to further explore the context-insensitive avoidance scale

- Pain catastrophizing levels differentiate between common diseases with pain: HIV, fibromyalgia, complex regional pain syndrome, and breast cancer survivors

- Prevalence of substance use disorder diagnoses in patients with chronic pain receiving reimbursed opioids: An epidemiological study of four Norwegian health registries

- Pain perception while listening to thrash heavy metal vs relaxing music at a heavy metal festival – the CoPainHell study – a factorial randomized non-blinded crossover trial

- Observational Studies

- Cutaneous nerve biopsy in patients with symptoms of small fiber neuropathy: a retrospective study

- The incidence of post cholecystectomy pain (PCP) syndrome at 12 months following laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a prospective evaluation in 200 patients

- Associations between psychological flexibility and daily functioning in endometriosis-related pain

- Relationship between perfectionism, overactivity, pain severity, and pain interference in individuals with chronic pain: A cross-lagged panel model analysis

- Access to psychological treatment for chronic cancer-related pain in Sweden

- Validation of the Danish version of the knowledge and attitudes survey regarding pain

- Associations between cognitive test scores and pain tolerance: The Tromsø study

- Healthcare experiences of fibromyalgia patients and their associations with satisfaction and pain relief. A patient survey

- Video interpretation in a medical spine clinic: A descriptive study of a diverse population and intervention

- Role of history of traumatic life experiences in current psychosomatic manifestations

- Social determinants of health in adults with whiplash associated disorders

- Which patients with chronic low back pain respond favorably to multidisciplinary rehabilitation? A secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial

- A preliminary examination of the effects of childhood abuse and resilience on pain and physical functioning in patients with knee osteoarthritis

- Differences in risk factors for flare-ups in patients with lumbar radicular pain may depend on the definition of flare

- Real-world evidence evaluation on consumer experience and prescription journey of diclofenac gel in Sweden

- Patient characteristics in relation to opioid exposure in a chronic non-cancer pain population

- Topical Reviews

- Bridging the translational gap: adenosine as a modulator of neuropathic pain in preclinical models and humans

- What do we know about Indigenous Peoples with low back pain around the world? A topical review

- The “future” pain clinician: Competencies needed to provide psychologically informed care

- Systematic Reviews

- Pain management for persistent pain post radiotherapy in head and neck cancers: systematic review

- High-frequency, high-intensity transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation compared with opioids for pain relief after gynecological surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis

- Reliability and measurement error of exercise-induced hypoalgesia in pain-free adults and adults with musculoskeletal pain: A systematic review

- Noninvasive transcranial brain stimulation in central post-stroke pain: A systematic review

- Short Communications

- Are we missing the opioid consumption in low- and middle-income countries?

- Association between self-reported pain severity and characteristics of United States adults (age ≥50 years) who used opioids

- Could generative artificial intelligence replace fieldwork in pain research?

- Skin conductance algesimeter is unreliable during sudden perioperative temperature increases

- Original Experimental

- Confirmatory study of the usefulness of quantum molecular resonance and microdissectomy for the treatment of lumbar radiculopathy in a prospective cohort at 6 months follow-up

- Pain catastrophizing in the elderly: An experimental pain study

- Improving general practice management of patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain: Interdisciplinarity, coherence, and concerns

- Concurrent validity of dynamic bedside quantitative sensory testing paradigms in breast cancer survivors with persistent pain

- Transcranial direct current stimulation is more effective than pregabalin in controlling nociceptive and anxiety-like behaviors in a rat fibromyalgia-like model

- Paradox pain sensitivity using cuff pressure or algometer testing in patients with hemophilia

- Physical activity with person-centered guidance supported by a digital platform or with telephone follow-up for persons with chronic widespread pain: Health economic considerations along a randomized controlled trial

- Measuring pain intensity through physical interaction in an experimental model of cold-induced pain: A method comparison study

- Pharmacological treatment of pain in Swedish nursing homes: Prevalence and associations with cognitive impairment and depressive mood

- Neck and shoulder pain and inflammatory biomarkers in plasma among forklift truck operators – A case–control study

- The effect of social exclusion on pain perception and heart rate variability in healthy controls and somatoform pain patients

- Revisiting opioid toxicity: Cellular effects of six commonly used opioids

- Letter to the Editor

- Post cholecystectomy pain syndrome: Letter to Editor

- Response to the Letter by Prof Bordoni

- Response – Reliability and measurement error of exercise-induced hypoalgesia

- Is the skin conductance algesimeter index influenced by temperature?

- Skin conductance algesimeter is unreliable during sudden perioperative temperature increase

- Corrigendum

- Corrigendum to “Chronic post-thoracotomy pain after lung cancer surgery: a prospective study of preoperative risk factors”

- Obituary

- A Significant Voice in Pain Research Björn Gerdle in Memoriam (1953–2024)