A preliminary examination of the effects of childhood abuse and resilience on pain and physical functioning in patients with knee osteoarthritis

-

JiHee Yoon

, Ayeong (Jenny) Kim

Abstract

Objectives

We examined associations of a self-reported history of childhood abuse with pain and physical functioning in patients with knee osteoarthritis (KOA) awaiting total knee arthroplasty (TKA). We also explored the potential moderating effects of positive childhood experiences (PCEs), an index of resilience, on these associations.

Methods

Prior to TKA, participants with KOA awaiting surgery (N = 239) completed self-report measures of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), PCEs, pain, and physical functioning. We evaluated associations of pain and physical functioning (Brief Pain Inventory [BPI] and Western Ontario and McMaster University of Osteoarthritis Index [WOMAC]) based on the experience of ACEs (childhood abuse), with PCEs (childhood happiness and supportive parental care) as potential moderators.

Results

Greater exposure to childhood abuse was positively correlated with BPI pain interference as well as WOMAC pain and functioning scores. Additionally, childhood happiness and supportive parental care moderated the positive associations of childhood abuse with pain and physical functioning; though, surprisingly, the adverse effects of childhood abuse on these outcomes were more pronounced among participants with high levels of childhood happiness and supportive parental care.

Conclusion

Overall, results show an association between a self-reported history of childhood abuse and pain and functioning in patients with KOA awaiting TKA. However, PCEs did not protect against the negative consequences of childhood abuse in our cohort. Further research is needed to validate these associations and gain a more comprehensive understanding of the complex interplay between childhood abuse and PCEs and their potential influences on pain experiences in adults with chronic pain conditions, including KOA.

1 Introduction

Knee osteoarthritis (KOA), affecting nearly 365 million individuals worldwide [1,2], is characterized by pain and functional impairment [3]. Identifying factors that contribute to these symptoms is crucial for improving KOA management.

Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), particularly childhood abuse, are linked to poorer pain and functioning outcomes. Chronic pain sufferers are more likely to report exposures to childhood abuse [4,5], and there is evidence of a prospective link between childhood abuse and the development of chronic pain conditions in adulthood [6,7]. Childhood abuse is also associated with more severe pain symptoms, with numerous studies demonstrating this significant relationship across various populations [8–13]. However, in the context of KOA, the evidence is limited, with only one study exploring this relationship, revealing a connection between childhood abuse and heightened centralized pain (e.g., widespread pain) [12].

Conversely, positive childhood experiences (PCEs) refer to nurturing social interactions and environmental factors encountered during formative years (e.g., supportive parental care) [14]. Importantly, studies have demonstrated a dose-dependent effect of PCEs on various adult health outcomes (e.g., depression) even after accounting for ACEs, indicating a resiliency-promoting role of PCEs [15–18]. Despite this, only a few studies have explored this relationship in the context of chronic pain. In a recent trial, Pugh et al. found that greater exposure to PCEs, particularly those related to social support and networks, was correlated with lower rates of pediatric chronic pain [16]. Furthermore, PCEs moderated the association between ACEs and pain, such that among children exposed to ≤2 ACEs, those who reported ≤5 PCEs were less likely to endorse chronic pain compared to those who reported ≥2 PCEs [16]. In adults with chronic pain, some studies indicate that childhood happiness is associated with higher quality of life and healthier responses to illness, factors linked to better pain outcomes [19,20].

Collectively, these findings align with the Mutual Maintenance Model, which posits that ACEs may create biopsychosocial vulnerabilities that negatively impact physical health, elevating the risk or intensity of chronic conditions like KOA [21]. Conversely, the presence of a chronic condition and its related symptoms can reinforce and aggravate these vulnerabilities, perpetuating the cycle. Importantly, PCEs may serve a protective role, interrupting this cycle of mutual maintenance between the two conditions [22]. This suggests that childhood happiness and supportive parental care could function as safeguards, mitigating the negative consequences of childhood abuse on pain and functioning. However, this has not yet been explored in older adults with chronic pain such as KOA.

This secondary analysis examined associations of a self-reported history of childhood abuse with pain and physical functioning in participants with KOA awaiting total knee arthroplasty (TKA). We hypothesized that greater exposure to childhood abuse would be associated with worse pain and functioning. Exploratory analyses were also conducted to assess the potential moderating effects of childhood happiness and supportive parental care on these associations. We hypothesized that the adverse effects of exposure to childhood abuse on pain and functioning would be attenuated among participants with higher levels of PCEs.

2 Methods

2.1 Participants

This was a secondary analysis of a parent study assessing biopsychosocial risk factors linked to post-surgical pain after TKA [23]. Participants were recruited from Brigham and Women’s Hospital (BWH, Boston, MA) and Johns Hopkins University (JHU, Baltimore, MD) through various modalities (e.g., flyers) from 2012 to 2018. Inclusion criteria encompassed age ≥45 years, meeting the American College of Rheumatology’s KOA criteria, and proficiency in English. Exclusion criteria included cognitive impairment hindering study completion and a history of specific conditions such as recent myocardial infarction, Raynaud’s disease, severe neuropathy, and severe peripheral vascular disease. A total of 248 participants completed the study. Of these, nine did not complete the questionnaire assessing childhood abuse, thus 239 participants were included in the final analyses.

2.2 Measures

Approximately 2 weeks before surgery, participants attended an in-person initial visit and completed self-report questionnaires on demographics, childhood abuse, PCEs, pain, and physical functioning.

2.2.1 Childhood abuse

Exposure to childhood abuse was assessed using a modified version of the standardized ACE questionnaire, which consisted of four items asking about specific types of abuse experienced during the first 18 years of life (i.e., verbal, emotional, physical, and severe physical abuse) on a Likert scale (0 [never] to 4 [very often]) [24]. The total score was averaged (range: 0–4), with higher scores indicating a greater degree of exposure to childhood abuse.

2.2.2 PCEs

A single question, “Overall, how happy was your childhood?” was asked to measure childhood happiness on a Likert scale (0 [not at all happy] to 10 [very happy]) [25]. For supportive parental care, one question was asked, “Overall, how well did your parents take care of you and provide for you during your childhood?” using a scale (0 [not well at all] to 10 [very well]).

2.2.3 Pain and physical functioning

Pain and pain-related interference related to daily activities (e.g., general activity, mood) were assessed using the Brief Pain Inventory (BPI) [26,27], while knee-specific pain and functioning were evaluated using the Western Ontario and McMaster University of Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) [28]. The total score for each subscale was averaged (range: 0–10 and 0–100 for the BPI and the WOMAC, respectively), with higher scores indicating worse pain and functioning.

2.3 Statistical analyses

Descriptive data are presented as mean values and standard deviations for continuous variables and as percentages for categorical variables (Table 1). Spearman correlations were performed to examine associations of childhood abuse with PCEs and self-reported pain and functioning. To explore the potential protective roles of PCEs on the associations of childhood abuse with pain and physical functioning, moderation analyses were conducted using the PROCESS macros for SPSS [29]. In each model, exposure to childhood abuse was entered as the independent variable, with childhood happiness or supportive parental care as the moderator variable, and pain or physical functioning as the outcome variable. Prior research has shown significant relationships of childhood abuse with gender and race, thus these factors were included as covariates in all moderation analyses [30–32]. All data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics Version 28.

Patient characteristics

| Full sample (N = 239) | |

|---|---|

| Age | 65.0 ± 8.2 |

| Gender | |

| Female | 59.4% |

| Race | |

| White | 88.2% |

| Black | 8.9% |

| Asian | 1.7% |

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 0.4% |

| More than one race | 0.8% |

| Ethnicity | |

| Hispanic/Latino | 99.6% |

| Non-Hispanic | 0.4% |

| Childhood abuse | 0.6 ± 0.8 |

| PCEs | |

| Childhood happiness | 7.7 ± 2.5 |

| Supportive parental care | 8.8 ± 1.9 |

| BPI | |

| Pain severity | 4.3 ± 2.2 |

| Pain interference | 4.3 ± 2.5 |

| WOMAC | |

| Pain | 45.3 ± 22.6 |

| Physical functioning | 46.3 ± 23.2 |

PCEs = positive childhood experiences; BPI = Brief Pain Inventory; WOMAC = Western Ontario and McMaster University of Osteoarthritis Index.

3 Results

3.1 Participant characteristics

The sample included 239 participants (M = 65 years, SD = 8 years; range: 48–87 years). Over half of the participants were female (59.9%) and non-Hispanic White (88.2%). There were no significant associations between childhood abuse and any of the demographic variables. The average score for exposure to childhood abuse was 0.60 (SD = 0.81; range: 0–4), with most participants endorsing generally high levels of childhood happiness (M = 7.7, SD = 2.5; range: 0–10) and supportive parental care (M = 8.8, SD = 1.9; range: 0–10). Descriptive data for demographics, childhood abuse, PCEs, and pain and functioning outcomes are further depicted in Table 1.

3.2 Associations of childhood abuse with PCEs, pain, and physical functioning

Results of spearman correlations showed that greater exposure to childhood abuse was associated with lower childhood happiness (p < 0.01) and supportive parental care (p < 0.01). Furthermore, BPI Pain Severity, but not Pain Interference scores, were positively correlated with childhood abuse (p = 0.03). Both WOMAC Pain (p = 0.01) and Physical Functioning scores (p = 0.01) were positively associated with childhood abuse. Neither childhood happiness nor supportive parental care were significantly correlated with pain or physical functioning outcomes (PS > 0.05; Table 2).

Correlations of childhood abuse with PCEs, pain, and physical functioning

| Childhood abuse | Childhood happiness | Supportive parental care | BPI severity | BPI interference | WOMAC-pain | WOMAC-PF | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Childhood abuse | — | ||||||

| Childhood happiness | −0.54** | — | |||||

| Supportive parental care | −0.46** | 0.71** | — | ||||

| BPI severity | 0.12 | −0.04 | −0.05 | — | |||

| BPI interference | 0.15* | −0.03 | −0.03 | 0.68** | — | ||

| WOMAC-pain | 0.16* | 0.00 | −0.05 | 0.73** | 0.71** | — | |

| WOMAC-PF | 0.17** | 0.02 | −0.11 | 0.70** | 0.68** | 0.81** | — |

*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; PCEs = positive childhood experiences, BPI = Brief Pain Inventory; WOMAC = Western Ontario and McMaster University of Osteoarthritis Index; PF = physical functioning.

3.3 Moderation analyses

Childhood happiness and supportive parental care were assessed as two potential resiliency-promoting factors against exposure to childhood abuse. Specifically, we explored whether these PCEs moderated the associations of childhood abuse with pain and physical functioning while controlling for sex and race.

3.3.1 Childhood happiness

Childhood happiness significantly moderated the association between childhood abuse and BPI Pain Interference scores (b = 0.15, 95% CI [0.02, 0.27], p = 0.02), while controlling for sex and race (Figure 1b). Unexpectedly, we found that among participants who endorsed high levels of childhood happiness (i.e., score ≥6.62), greater exposure to childhood abuse was associated with higher BPI Pain Interference scores (p ≤ 0.05). In contrast, among those who endorsed low levels of childhood happiness (i.e., score ≤6.50), exposure to childhood abuse and BPI Pain Interference scores were not significantly associated (p > 0.05). Childhood happiness did not significantly moderate the associations between exposure to childhood abuse and BPI Pain Severity (p = 0.06; Figure 1a), WOMAC Pain (p = 0.33; Figure 1c), or WOMAC Physical Functioning scores (p = 0.24; Figure 1d).

Moderating effects of childhood happiness on the association of childhood abuse with pain and physical functioning, while controlling for sex and race. Childhood happiness as a moderator of (a) the association between childhood abuse and BPI pain severity (higher score = worse pain), (b) the association between childhood abuse and BPI pain interference (higher score = greater interference), (c) the association between childhood abuse and WOMAC pain (higher score = worse pain), and (d) the association between childhood abuse and WOMAC physical functioning (higher score = poorer functioning). CA = childhood abuse; BPI = Brief Pain Inventory; WOMAC = Western Ontario and McMaster University of Osteoarthritis Index; PF = physical functioning.

3.3.2 Supportive parental care

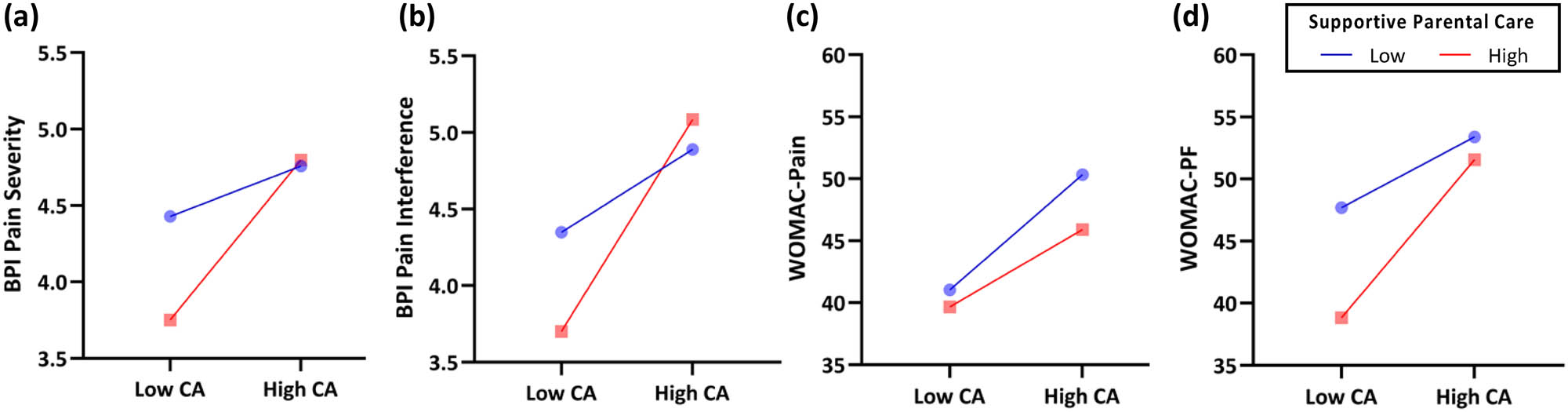

Supportive parental care significantly moderated the associations of childhood abuse with both BPI Pain Severity (b = 0.14, 95% CI [0.02, 0.26], p = 0.02; Figure 2a) and BPI Pain Interference scores (b = 0.17, 95% CI [0.03, 0.31], p = 0.02; Figure 2b), as well as WOMAC Physical Functioning scores (b = 1.44, 95% CI [0.24, 2.65], p = 0.02; Figure 2d), while controlling for sex and race. Similar to the finding observed with childhood happiness as a moderator, we found that among participants who reported higher levels of supportive parental care during childhood (i.e., score ≥8.69, ≥7.89, ≥7.52, respectively), greater exposure to childhood abuse was associated with higher BPI Pain Severity and Pain Interference as well as worse WOMAC Physical Functioning scores (PS ≤ 0.05). Contrastingly, among those who reported low levels of supportive parental care (i.e., score ≤8.50, ≤7.50, ≤7.50, respectively), the associations of childhood abuse with these BPI and WOMAC outcomes were not significant (PS > 0.05). Supportive parental care did not significantly moderate the association between childhood abuse and WOMAC Pain scores (p = 0.28; Figure 2c).

Moderating effects of supportive parental care on the association of childhood abuse with pain and physical functioning, while controlling for sex and race. Childhood happiness as a moderator of (a) the association between childhood abuse and BPI pain severity (higher score = worse pain), (b) the association between childhood abuse and BPI pain interference (higher score = greater interference), (c) the association between childhood abuse and WOMAC pain (higher score = worse pain), and (d) the association between childhood abuse and WOMAC physical functioning (higher score = poorer functioning). CA = childhood abuse; BPI = Brief Pain Inventory; WOMAC = Western Ontario and McMaster University of Osteoarthritis Index; PF = physical functioning.

4 Discussion

In this study, we identified positive correlations between childhood abuse and pain and functioning outcomes in participants with KOA. Our findings align with prior literature that has shown significant links between childhood abuse and more severe pain in individuals with KOA [12] and other chronic pain conditions [10,13,33,34]. For example, Pierce et al. Found significant relationships between childhood abuse and centralized pain, including heightened sensory sensitivity and widespread pain, in participants with KOA [12]. Our results complement and expand upon these by offering preliminary evidence that childhood abuse may also be associated with knee-specific pain in addition to centralized pain. Given that enhanced functioning is a crucial goal in the management of KOA, our result of significant correlations between childhood abuse and functional outcomes further emphasizes the importance of evaluating this relationship in people with KOA. Nonetheless, due to the paucity of existing research on this topic, further investigation is needed.

Previous research has shown that PCEs can serve as a resiliency-promoting factor, mitigating negative effects of ACEs on health outcomes among adults [15–17,35]. A recent study focused on pediatric chronic pain also yielded similar results [16]. In contrast, we found that the adverse effects of childhood abuse on pain and physical functioning were more pronounced among participants with high levels of childhood happiness and supportive parental care. One possible explanation for this discrepancy is the differences in the study design. Specifically, Pugh et al. examined the cumulative effects of neglect and family dysfunction [16,36] whereas we assessed those of childhood abuse only. Consequently, the inconsistent findings may suggest that different ACE categories may have varying effects on pain outcomes in the context of PCEs. However, due to the lack of research in this area, it is challenging to ascertain the extent to which these divergent effects may have contributed to observed inconsistencies. Thus, additional research is needed to examine these relationships more closely.

Nevertheless, our preliminary findings highlight the complexity of the relationships between childhood abuse and PCEs and suggest considering the broader context in which childhood abuse occurs may be important when working with patients with pain. For instance, in the present study, it may seem paradoxical that participants who reported high levels of childhood abuse also reported higher degrees of PCEs. Yet, a more nuanced evaluation of this finding by considering contextual factors may offer clarity. For example, in two-parent households, an individual may be recalling abuse by one parent while receiving support from another. Alternatively, an abusive parent may intermittently display loving and supportive behavior while remaining emotionally or physically abusive. Noteworthy is the latter scenario, as evidence suggests that liability in the parent’s behaviors, even when accompanied with positive parenting practices, may be damaging especially among those exposed to childhood abuse [37]. Thus, future research that employs assessments capturing the nuanced details of these experiences is necessary to fully understand the relationships between childhood abuse, PCEs, and pain outcomes in adulthood.

Several important limitations should be acknowledged. Given the cross-sectional nature of the present study, we are unable to establish causality. Although we recruited participants from two large academic medical centers in distinct geographic regions, our sample was largely homogenous (i.e., White female). Given the well-documented racial and ethnic disparities in childhood abuse and KOA [32], future studies should investigate these relationships using a more diverse and encompassing sample. Moreover, our study focused on older adults aged 45 and above with a specific chronic pain condition, limiting generalizability of our findings to younger populations or those with other types of chronic pain.

Lastly, we acknowledge that the self-report measure used to assess the degree of exposure to childhood abuse in our study may not have been sensitive enough to fully capture the nuanced understanding of how childhood abuse is related to pain, physical functioning, and PCEs. Additionally, definitions and norms related to childhood abuse have shifted over time, which may further impact self-reporting prevalence and the most accurate reports of childhood abuse [38]. Future longitudinal studies and those employing mixed methodology are needed to better understand how older adults conceptualize childhood abuse. Such methods would allow for a more nuanced understanding of the ages, frequency, and situations around which exposure to childhood abuse occurred, allowing for a more comprehensive understanding of how these experiences influence the pain experience.

5 Implications

Given the relationship between exposure to childhood abuse and pain, clinical providers should consider adopting trauma-informed and trauma-focused approaches. These include screening for a history of childhood abuse in patients presenting with painful conditions like KOA and referring those with such a history to appropriate psychosocial interventions such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) [39]. CBT aims to modify negative thought patterns and behaviors [40]. Meanwhile, ACT encourages an open, non-judgmental acceptance of experiences, emphasizing psychological flexibility, mindfulness, and actions aligned with personal values [41]. Evidence supports the efficacy of these interventions in reducing pain, enhancing functionality, and improving well-being across various chronic pain conditions [42,43]. Notably, these interventions target common psychological underpinnings resulting from childhood abuse and pain, such as negative affect and catastrophizing, making them valuable tools in pain management for individuals with a history of childhood abuse [43,44]. Furthermore, incorporating trauma-specific therapies like prolonged exposure (PE) and cognitive processing therapy (CPT) can offer additional benefits. PE helps patients gradually confront trauma-related memories [45], while CPT assists in the cognitive restructuring of trauma-related thoughts [46]. Integrating these interventions with standard pain management offers a comprehensive, multimodal strategy that effectively addresses the complex relationship between KOA and childhood abuse, significantly enhancing pain management outcomes.

6 Conclusion

We found that a self-reported history of childhood abuse was associated with worse pain and poorer physical functioning among older adults with KOA, and that the relationships between childhood abuse and worse outcomes were strongest among those with high levels of childhood happiness and parental care. These results suggest that childhood abuse and PCEs may impact the pain experience in adulthood and highlight important opportunities to optimize the treatment for KOA.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the patients who participated in this study as well as the study coordinators who collected data and conducted study visits.

-

Research ethics: Research involving human subjects complied with all relevant national regulations, institutional policies and in accordance with the tenets of the Helsinki Declarations (as amended in 2013). The present study was conducted in two teaching hospitals located in the Boston (BWH) and Baltimore (JHU) metropolitan regions. All study-related procedures were approved by the BWH and the JHU Institutional Review Boards (IRB#: 2010P000978) [23].

-

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individuals included in this study, or their legal guardians or wards.

-

Author contributions: The authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Competing interests: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: This research was supported by US National Institutes for Health (NIH) National Institutes for Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS; R01-AG034982) to R.R.E., C.M.C., M.T.S., J.A.H., and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS; R35GM142676) to C.B.S.

-

Data availability: The raw data can be obtained on request from the corresponding author.

-

Trial registration: The study is registered as NCT01370421.

-

Artificial intelligence/Machine learning tools: Not applicable.

References

[1] Cui A, Li H, Wang D, Zhong J, Chen Y, Lu H. Global, regional prevalence, incidence and risk factors of knee osteoarthritis in population-based studies. eClinicalMedicine. 2020 Dec;29:100587. 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100587.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[2] Deshpande BR, Katz JN, Solomon DH, Yelin EH, Hunter DJ, Messier SP, et al. Number of persons with symptomatic knee osteoarthritis in the us: impact of race and ethnicity, age, sex, and obesity. Arthritis Care Res. 2016;68(12):1743–50.10.1002/acr.22897Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[3] Neogi T. The epidemiology and impact of pain in osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2013 Sep;21(9):1145–53.10.1016/j.joca.2013.03.018Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[4] Craner JR, Lake ES, Barr AC, Kirby KE, O’Neill M. Childhood adversity among adults with chronic pain: prevalence and association with pain-related outcomes. Clin J Pain. 2022 Sep;38(9):551–61.10.1097/AJP.0000000000001054Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[5] Fuller-Thomson E, Stefanyk M, Brennenstuhl S. The robust association between childhood physical abuse and osteoarthritis in adulthood: findings from a representative community sample. Arthritis Care Res. 2009;61(11):1554–62.10.1002/art.24871Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] Meints SM, Edwards RR. Evaluating psychosocial contributions to chronic pain outcomes. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2018 Dec;87(Pt B):168–82.10.1016/j.pnpbp.2018.01.017Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[7] Edwards RR, Dworkin RH, Sullivan MD, Turk DC, Wasan AD. The role of psychosocial processes in the development and maintenance of chronic pain. J Pain. 2016 Sep;17(9 Suppl):T70–92.10.1016/j.jpain.2016.01.001Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[8] Fillingim RB, Edwards RR. Is self-reported childhood abuse history associated with pain perception among healthy young women and men? Clin J Pain. 2005 Oct;21(5):387–97.10.1097/01.ajp.0000149801.46864.39Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] Fillingim RB, Wilkinson CS, Powell T. Self-reported abuse history and pain complaints among young adults. Clin J Pain. 1999 Jun;15(2):85–91.10.1097/00002508-199906000-00004Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[10] Green CR, Flowe-Valencia H, Rosenblum L, Tait AR. The role of childhood and adulthood abuse among women presenting for chronic pain management. Clin J Pain. 2001 Dec;17(4):359.10.1097/00002508-200112000-00011Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] Brown RC, Plener PL, Braehler E, Fegert JM, Huber-Lang M. Associations of adverse childhood experiences and bullying on physical pain in the general population of Germany. J Pain Res. 2018 Dec;11:3099–108.10.2147/JPR.S169135Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[12] Pierce J, Hassett AL, Brummett CM, McAfee J, Sieberg C, Schrepf A, et al. Characterizing pain and generalized sensory sensitivity according to trauma history among patients with knee osteoarthritis. Ann Behav Med. 2021 Sep;55(9):853–69.10.1093/abm/kaaa105Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[13] Bohn D, Bernardy K, Wolfe F, Häuser W. The association among childhood maltreatment, somatic symptom intensity, depression, and somatoform dissociative symptoms in patients with fibromyalgia syndrome: a single-center cohort study. J Trauma Dissociation. 2013 May;14(3):342–58.10.1080/15299732.2012.736930Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[14] Risk and Protective Factors |Violence Prevention|Injury Center|CDC; 2023. [cited 2023 Sep 11] https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/aces/riskprotectivefactors.html.Search in Google Scholar

[15] Bethell C, Jones J, Gombojav N, Linkenbach J, Sege R. Positive childhood experiences and adult mental and relational health in a statewide sample: associations across adverse childhood experiences levels. JAMA Pediatr. 2019 Nov;173(11):e193007.10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.3007Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[16] Pugh SJ, Murray C, Groenewald CB. Positive childhood experiences and chronic pain among children and adolescents in the United States. J Pain. 2023;24(7):1193–202.10.1016/j.jpain.2023.02.001Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[17] Qu G, Ma S, Liu H, Han T, Zhang H, Ding X, et al. Positive childhood experiences can moderate the impact of adverse childhood experiences on adolescent depression and anxiety: results from a cross-sectional survey. Child Abuse Negl. 2022 Mar;125:105511.10.1016/j.chiabu.2022.105511Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[18] Huang ZY, Huang Q, Wang LY, Lei YT, Xu H, Shen B, et al. Normal trajectory of interleukin-6 and C-reactive protein in the perioperative period of total knee arthroplasty under an enhanced recovery after surgery scenario. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2020 Apr;21:264.10.1186/s12891-020-03283-5Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[19] Macfarlane TV, Kincey J, Worthington HV. The association between psychological factors and oro-facial pain: a community-based study. Eur J Pain Lond Engl. 2002;6(6):427–34.10.1016/S1090-3801(02)00045-9Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[20] Nagarajappa AK, Bhasin N, Reddy S. The association between psychological factors and orofacial pain and its effect on quality of life: a hospital based study. J Clin Diagn Res JCDR. 2015 May;9(5):43.Search in Google Scholar

[21] Sharp TJ, Harvey AG. Chronic pain and posttraumatic stress disorder: mutual maintenance? Clin Psychol Rev. 2001 Aug;21(6):857–77.10.1016/S0272-7358(00)00071-4Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[22] Kind S, Otis JD. The interaction between chronic pain and PTSD. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2019 Nov;23(12):91.10.1007/s11916-019-0828-3Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[23] Edwards RR, Campbell C, Schreiber KL, Meints S, Lazaridou A, Martel MO, et al. Multimodal prediction of pain and functional outcomes 6 months following total knee replacement: a prospective cohort study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2022 Mar 29;23(1):302.10.1186/s12891-022-05239-3Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[24] Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, Williamson DF, Spitz AM, Edwards V, et al. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am J Prev Med. 1998 May;14(4):245–58.10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00017-8Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[25] Bellis MA, Hughes K, Jones A, Perkins C, McHale P. Childhood happiness and violence: a retrospective study of their impacts on adult well-being. BMJ Open. 2013 Sep;3(9):e003427.10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003427Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[26] Tan G, Jensen MP, Thornby JI, Shanti BF. Validation of the brief pain inventory for chronic nonmalignant pain. J Pain. 2004 Mar;5(2):133–7.10.1016/j.jpain.2003.12.005Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[27] Cleeland CS, Ryan KM. Pain assessment: global use of the brief pain inventory. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 1994 Mar;23(2):129–38.Search in Google Scholar

[28] Lingard EA, Katz JN, Wright RJ, Wright EA, Sledge CB, Kinemax Outcomes Group. Validity and responsiveness of the Knee Society Clinical Rating System in comparison with the SF-36 and WOMAC. J Bone Jt Surg Am. 2001 Dec;83(12):1856–64.10.2106/00004623-200112000-00014Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[29] Hayes AF. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression-based approach. 2nd edn. New York: Guilford Press; 2018. p. 692. (Methodology in the social sciences).Search in Google Scholar

[30] Glass N, Segal NA, Sluka KA, Torner JC, Nevitt MC, Felson DT, et al. Examining sex differences in knee pain: the multicenter osteoarthritis study. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2014 Aug;22(8):1100–6.10.1016/j.joca.2014.06.030Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[31] Haahr-Pedersen I, Perera C, Hyland P, Vallières F, Murphy D, Hansen M, et al. Females have more complex patterns of childhood adversity: implications for mental, social, and emotional outcomes in adulthood. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2020;11(1):1708618.10.1080/20008198.2019.1708618Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[32] Mersky JP, Choi C, Plummer Lee C, Janczewski CE. Disparities in adverse childhood experiences by race/ethnicity, gender, and economic status: Intersectional analysis of a nationally representative sample. Child Abuse Negl. 2021 Jul;117:105066.10.1016/j.chiabu.2021.105066Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[33] Gardoki-Souto I, Redolar-Ripoll D, Fontana M, Hogg B, Castro MJ, Blanch JM, et al. Prevalence and characterization of psychological trauma in patients with fibromyalgia: a cross-sectional study. Pain Res Manag. 2022 Nov;2022:1–16.10.1155/2022/2114451Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[34] Tietjen GE, Peterlin BL. Childhood abuse and migraine: epidemiology, sex differences, and potential mechanisms. Headache. 2011 Jun;51(6):869–79.10.1111/j.1526-4610.2011.01906.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[35] Huang CX, Halfon N, Sastry N, Chung PJ, Schickedanz A. Positive childhood experiences and adult health outcomes. Pediatrics. 2023 Jul;152(1):e2022060951.10.1542/peds.2022-060951Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[36] Crouch E, Radcliff E, Kelly K, Merrell MA, Bennett KJ. Examining the influence of positive childhood experiences on childhood overweight and obesity using a national sample. Prev Med. 2022 Jan;154:106907.10.1016/j.ypmed.2021.106907Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[37] Yoon S, Bellamy JL, Kim W, Yoon D. Father involvement and behavior problems among preadolescents at risk of maltreatment. J Child Fam Stud. 2018 Feb;27(2):494–504.10.1007/s10826-017-0890-6Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[38] Board on Children Y, Medicine I of, Council NR. Social trends and child maltreatment trends. Child maltreatment research, policy, and practice for the next decade: Workshop summary. US: National Academies Press; 2012. [cited 2023 May 14] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK201120/.Search in Google Scholar

[39] Yamin JB, Meints SM, Edwards RR. Beyond pain catastrophizing: rationale and recommendations for targeting trauma in the assessment and treatment of chronic pain. Expert Rev Neurother. 2024 Mar;24(3):231–4.10.1080/14737175.2024.2311275Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[40] Driscoll MA, Edwards RR, Becker WC, Kaptchuk TJ, Kerns RD. Psychological interventions for the treatment of chronic pain in adults. Psychol Sci Public Interest J Am Psychol Soc. 2021 Sep;22(2):52–95.10.1177/15291006211008157Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[41] Hayes SC, Levin ME, Plumb-Vilardaga J, Villatte JL, Pistorello J. Acceptance and commitment therapy and contextual behavioral science: examining the progress of a distinctive model of behavioral and cognitive therapy. Behav Ther. 2013 Jun;44(2):180–98.10.1016/j.beth.2009.08.002Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[42] de C Williams AC, Fisher E, Hearn L, Eccleston C. Psychological therapies for the management of chronic pain (excluding headache) in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;8(11):CD007407. 10.1002/14651858.CD007407.pub4.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[43] Hughes LS, Clark J, Colclough JA, Dale E, McMillan D. Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) for chronic pain: a systematic review and meta-analyses. Clin J Pain. 2017 Jun;33(6):552–68.10.1097/AJP.0000000000000425Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[44] Schütze R, Rees C, Smith A, Slater H, Campbell JM, O’Sullivan P. How can we best reduce pain catastrophizing in adults with chronic noncancer pain? A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pain. 2018 Mar;19(3):233–56.10.1016/j.jpain.2017.09.010Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[45] Foa EB. Prolonged exposure therapy: past, present, and future. Depress Anxiety. 2011;28(12):1043–7.10.1002/da.20907Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[46] Resick PA, Schnicke MK. Cognitive processing therapy for sexual assault victims. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1992 Oct;60(5):748–56.10.1037//0022-006X.60.5.748Search in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Editorial Comment

- From pain to relief: Exploring the consistency of exercise-induced hypoalgesia

- Christmas greetings 2024 from the Editor-in-Chief

- Original Articles

- The Scandinavian Society for the Study of Pain 2022 Postgraduate Course and Annual Scientific (SASP 2022) Meeting 12th to 14th October at Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen

- Comparison of ultrasound-guided continuous erector spinae plane block versus continuous paravertebral block for postoperative analgesia in patients undergoing proximal femur surgeries

- Clinical Pain Researches

- The effect of tourniquet use on postoperative opioid consumption after ankle fracture surgery – a retrospective cohort study

- Changes in pain, daily occupations, lifestyle, and health following an occupational therapy lifestyle intervention: a secondary analysis from a feasibility study in patients with chronic high-impact pain

- Tonic cuff pressure pain sensitivity in chronic pain patients and its relation to self-reported physical activity

- Reliability, construct validity, and factorial structure of a Swedish version of the medical outcomes study social support survey (MOS-SSS) in patients with chronic pain

- Hurdles and potentials when implementing internet-delivered Acceptance and commitment therapy for chronic pain: a retrospective appraisal using the Quality implementation framework

- Exploring the outcome “days with bothersome pain” and its association with pain intensity, disability, and quality of life

- Fatigue and cognitive fatigability in patients with chronic pain

- The Swedish version of the pain self-efficacy questionnaire short form, PSEQ-2SV: Cultural adaptation and psychometric evaluation in a population of patients with musculoskeletal disorders

- Pain coping and catastrophizing in youth with and without cerebral palsy

- Neuropathic pain after surgery – A clinical validation study and assessment of accuracy measures of the 5-item NeuPPS scale

- Translation, contextual adaptation, and reliability of the Danish Concept of Pain Inventory (COPI-Adult (DK)) – A self-reported outcome measure

- Cosmetic surgery and associated chronic postsurgical pain: A cross-sectional study from Norway

- The association of hemodynamic parameters and clinical demographic variables with acute postoperative pain in female oncological breast surgery patients: A retrospective cohort study

- Healthcare professionals’ experiences of interdisciplinary collaboration in pain centres – A qualitative study

- Effects of deep brain stimulation and verbal suggestions on pain in Parkinson’s disease

- Painful differences between different pain scale assessments: The outcome of assessed pain is a matter of the choices of scale and statistics

- Prevalence and characteristics of fibromyalgia according to three fibromyalgia diagnostic criteria: A secondary analysis study

- Sex moderates the association between quantitative sensory testing and acute and chronic pain after total knee/hip arthroplasty

- Tramadol-paracetamol for postoperative pain after spine surgery – A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study

- Cancer-related pain experienced in daily life is difficult to communicate and to manage – for patients and for professionals

- Making sense of pain in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD): A qualitative study

- Patient-reported pain, satisfaction, adverse effects, and deviations from ambulatory surgery pain medication

- Does pain influence cognitive performance in patients with mild traumatic brain injury?

- Hypocapnia in women with fibromyalgia

- Application of ultrasound-guided thoracic paravertebral block or intercostal nerve block for acute herpes zoster and prevention of post-herpetic neuralgia: A case–control retrospective trial

- Translation and examination of construct validity of the Danish version of the Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia

- A positive scratch collapse test in anterior cutaneous nerve entrapment syndrome indicates its neuropathic character

- ADHD-pain: Characteristics of chronic pain and association with muscular dysregulation in adults with ADHD

- The relationship between changes in pain intensity and functional disability in persistent disabling low back pain during a course of cognitive functional therapy

- Intrathecal pain treatment for severe pain in patients with terminal cancer: A retrospective analysis of treatment-related complications and side effects

- Psychometric evaluation of the Danish version of the Pain Self-Efficacy Questionnaire in patients with subacute and chronic low back pain

- Dimensionality, reliability, and validity of the Finnish version of the pain catastrophizing scale in chronic low back pain

- To speak or not to speak? A secondary data analysis to further explore the context-insensitive avoidance scale

- Pain catastrophizing levels differentiate between common diseases with pain: HIV, fibromyalgia, complex regional pain syndrome, and breast cancer survivors

- Prevalence of substance use disorder diagnoses in patients with chronic pain receiving reimbursed opioids: An epidemiological study of four Norwegian health registries

- Pain perception while listening to thrash heavy metal vs relaxing music at a heavy metal festival – the CoPainHell study – a factorial randomized non-blinded crossover trial

- Observational Studies

- Cutaneous nerve biopsy in patients with symptoms of small fiber neuropathy: a retrospective study

- The incidence of post cholecystectomy pain (PCP) syndrome at 12 months following laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a prospective evaluation in 200 patients

- Associations between psychological flexibility and daily functioning in endometriosis-related pain

- Relationship between perfectionism, overactivity, pain severity, and pain interference in individuals with chronic pain: A cross-lagged panel model analysis

- Access to psychological treatment for chronic cancer-related pain in Sweden

- Validation of the Danish version of the knowledge and attitudes survey regarding pain

- Associations between cognitive test scores and pain tolerance: The Tromsø study

- Healthcare experiences of fibromyalgia patients and their associations with satisfaction and pain relief. A patient survey

- Video interpretation in a medical spine clinic: A descriptive study of a diverse population and intervention

- Role of history of traumatic life experiences in current psychosomatic manifestations

- Social determinants of health in adults with whiplash associated disorders

- Which patients with chronic low back pain respond favorably to multidisciplinary rehabilitation? A secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial

- A preliminary examination of the effects of childhood abuse and resilience on pain and physical functioning in patients with knee osteoarthritis

- Differences in risk factors for flare-ups in patients with lumbar radicular pain may depend on the definition of flare

- Real-world evidence evaluation on consumer experience and prescription journey of diclofenac gel in Sweden

- Patient characteristics in relation to opioid exposure in a chronic non-cancer pain population

- Topical Reviews

- Bridging the translational gap: adenosine as a modulator of neuropathic pain in preclinical models and humans

- What do we know about Indigenous Peoples with low back pain around the world? A topical review

- The “future” pain clinician: Competencies needed to provide psychologically informed care

- Systematic Reviews

- Pain management for persistent pain post radiotherapy in head and neck cancers: systematic review

- High-frequency, high-intensity transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation compared with opioids for pain relief after gynecological surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis

- Reliability and measurement error of exercise-induced hypoalgesia in pain-free adults and adults with musculoskeletal pain: A systematic review

- Noninvasive transcranial brain stimulation in central post-stroke pain: A systematic review

- Short Communications

- Are we missing the opioid consumption in low- and middle-income countries?

- Association between self-reported pain severity and characteristics of United States adults (age ≥50 years) who used opioids

- Could generative artificial intelligence replace fieldwork in pain research?

- Skin conductance algesimeter is unreliable during sudden perioperative temperature increases

- Original Experimental

- Confirmatory study of the usefulness of quantum molecular resonance and microdissectomy for the treatment of lumbar radiculopathy in a prospective cohort at 6 months follow-up

- Pain catastrophizing in the elderly: An experimental pain study

- Improving general practice management of patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain: Interdisciplinarity, coherence, and concerns

- Concurrent validity of dynamic bedside quantitative sensory testing paradigms in breast cancer survivors with persistent pain

- Transcranial direct current stimulation is more effective than pregabalin in controlling nociceptive and anxiety-like behaviors in a rat fibromyalgia-like model

- Paradox pain sensitivity using cuff pressure or algometer testing in patients with hemophilia

- Physical activity with person-centered guidance supported by a digital platform or with telephone follow-up for persons with chronic widespread pain: Health economic considerations along a randomized controlled trial

- Measuring pain intensity through physical interaction in an experimental model of cold-induced pain: A method comparison study

- Pharmacological treatment of pain in Swedish nursing homes: Prevalence and associations with cognitive impairment and depressive mood

- Neck and shoulder pain and inflammatory biomarkers in plasma among forklift truck operators – A case–control study

- The effect of social exclusion on pain perception and heart rate variability in healthy controls and somatoform pain patients

- Revisiting opioid toxicity: Cellular effects of six commonly used opioids

- Letter to the Editor

- Post cholecystectomy pain syndrome: Letter to Editor

- Response to the Letter by Prof Bordoni

- Response – Reliability and measurement error of exercise-induced hypoalgesia

- Is the skin conductance algesimeter index influenced by temperature?

- Skin conductance algesimeter is unreliable during sudden perioperative temperature increase

- Corrigendum

- Corrigendum to “Chronic post-thoracotomy pain after lung cancer surgery: a prospective study of preoperative risk factors”

- Obituary

- A Significant Voice in Pain Research Björn Gerdle in Memoriam (1953–2024)

Articles in the same Issue

- Editorial Comment

- From pain to relief: Exploring the consistency of exercise-induced hypoalgesia

- Christmas greetings 2024 from the Editor-in-Chief

- Original Articles

- The Scandinavian Society for the Study of Pain 2022 Postgraduate Course and Annual Scientific (SASP 2022) Meeting 12th to 14th October at Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen

- Comparison of ultrasound-guided continuous erector spinae plane block versus continuous paravertebral block for postoperative analgesia in patients undergoing proximal femur surgeries

- Clinical Pain Researches

- The effect of tourniquet use on postoperative opioid consumption after ankle fracture surgery – a retrospective cohort study

- Changes in pain, daily occupations, lifestyle, and health following an occupational therapy lifestyle intervention: a secondary analysis from a feasibility study in patients with chronic high-impact pain

- Tonic cuff pressure pain sensitivity in chronic pain patients and its relation to self-reported physical activity

- Reliability, construct validity, and factorial structure of a Swedish version of the medical outcomes study social support survey (MOS-SSS) in patients with chronic pain

- Hurdles and potentials when implementing internet-delivered Acceptance and commitment therapy for chronic pain: a retrospective appraisal using the Quality implementation framework

- Exploring the outcome “days with bothersome pain” and its association with pain intensity, disability, and quality of life

- Fatigue and cognitive fatigability in patients with chronic pain

- The Swedish version of the pain self-efficacy questionnaire short form, PSEQ-2SV: Cultural adaptation and psychometric evaluation in a population of patients with musculoskeletal disorders

- Pain coping and catastrophizing in youth with and without cerebral palsy

- Neuropathic pain after surgery – A clinical validation study and assessment of accuracy measures of the 5-item NeuPPS scale

- Translation, contextual adaptation, and reliability of the Danish Concept of Pain Inventory (COPI-Adult (DK)) – A self-reported outcome measure

- Cosmetic surgery and associated chronic postsurgical pain: A cross-sectional study from Norway

- The association of hemodynamic parameters and clinical demographic variables with acute postoperative pain in female oncological breast surgery patients: A retrospective cohort study

- Healthcare professionals’ experiences of interdisciplinary collaboration in pain centres – A qualitative study

- Effects of deep brain stimulation and verbal suggestions on pain in Parkinson’s disease

- Painful differences between different pain scale assessments: The outcome of assessed pain is a matter of the choices of scale and statistics

- Prevalence and characteristics of fibromyalgia according to three fibromyalgia diagnostic criteria: A secondary analysis study

- Sex moderates the association between quantitative sensory testing and acute and chronic pain after total knee/hip arthroplasty

- Tramadol-paracetamol for postoperative pain after spine surgery – A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study

- Cancer-related pain experienced in daily life is difficult to communicate and to manage – for patients and for professionals

- Making sense of pain in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD): A qualitative study

- Patient-reported pain, satisfaction, adverse effects, and deviations from ambulatory surgery pain medication

- Does pain influence cognitive performance in patients with mild traumatic brain injury?

- Hypocapnia in women with fibromyalgia

- Application of ultrasound-guided thoracic paravertebral block or intercostal nerve block for acute herpes zoster and prevention of post-herpetic neuralgia: A case–control retrospective trial

- Translation and examination of construct validity of the Danish version of the Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia

- A positive scratch collapse test in anterior cutaneous nerve entrapment syndrome indicates its neuropathic character

- ADHD-pain: Characteristics of chronic pain and association with muscular dysregulation in adults with ADHD

- The relationship between changes in pain intensity and functional disability in persistent disabling low back pain during a course of cognitive functional therapy

- Intrathecal pain treatment for severe pain in patients with terminal cancer: A retrospective analysis of treatment-related complications and side effects

- Psychometric evaluation of the Danish version of the Pain Self-Efficacy Questionnaire in patients with subacute and chronic low back pain

- Dimensionality, reliability, and validity of the Finnish version of the pain catastrophizing scale in chronic low back pain

- To speak or not to speak? A secondary data analysis to further explore the context-insensitive avoidance scale

- Pain catastrophizing levels differentiate between common diseases with pain: HIV, fibromyalgia, complex regional pain syndrome, and breast cancer survivors

- Prevalence of substance use disorder diagnoses in patients with chronic pain receiving reimbursed opioids: An epidemiological study of four Norwegian health registries

- Pain perception while listening to thrash heavy metal vs relaxing music at a heavy metal festival – the CoPainHell study – a factorial randomized non-blinded crossover trial

- Observational Studies

- Cutaneous nerve biopsy in patients with symptoms of small fiber neuropathy: a retrospective study

- The incidence of post cholecystectomy pain (PCP) syndrome at 12 months following laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a prospective evaluation in 200 patients

- Associations between psychological flexibility and daily functioning in endometriosis-related pain

- Relationship between perfectionism, overactivity, pain severity, and pain interference in individuals with chronic pain: A cross-lagged panel model analysis

- Access to psychological treatment for chronic cancer-related pain in Sweden

- Validation of the Danish version of the knowledge and attitudes survey regarding pain

- Associations between cognitive test scores and pain tolerance: The Tromsø study

- Healthcare experiences of fibromyalgia patients and their associations with satisfaction and pain relief. A patient survey

- Video interpretation in a medical spine clinic: A descriptive study of a diverse population and intervention

- Role of history of traumatic life experiences in current psychosomatic manifestations

- Social determinants of health in adults with whiplash associated disorders

- Which patients with chronic low back pain respond favorably to multidisciplinary rehabilitation? A secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial

- A preliminary examination of the effects of childhood abuse and resilience on pain and physical functioning in patients with knee osteoarthritis

- Differences in risk factors for flare-ups in patients with lumbar radicular pain may depend on the definition of flare

- Real-world evidence evaluation on consumer experience and prescription journey of diclofenac gel in Sweden

- Patient characteristics in relation to opioid exposure in a chronic non-cancer pain population

- Topical Reviews

- Bridging the translational gap: adenosine as a modulator of neuropathic pain in preclinical models and humans

- What do we know about Indigenous Peoples with low back pain around the world? A topical review

- The “future” pain clinician: Competencies needed to provide psychologically informed care

- Systematic Reviews

- Pain management for persistent pain post radiotherapy in head and neck cancers: systematic review

- High-frequency, high-intensity transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation compared with opioids for pain relief after gynecological surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis

- Reliability and measurement error of exercise-induced hypoalgesia in pain-free adults and adults with musculoskeletal pain: A systematic review

- Noninvasive transcranial brain stimulation in central post-stroke pain: A systematic review

- Short Communications

- Are we missing the opioid consumption in low- and middle-income countries?

- Association between self-reported pain severity and characteristics of United States adults (age ≥50 years) who used opioids

- Could generative artificial intelligence replace fieldwork in pain research?

- Skin conductance algesimeter is unreliable during sudden perioperative temperature increases

- Original Experimental

- Confirmatory study of the usefulness of quantum molecular resonance and microdissectomy for the treatment of lumbar radiculopathy in a prospective cohort at 6 months follow-up

- Pain catastrophizing in the elderly: An experimental pain study

- Improving general practice management of patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain: Interdisciplinarity, coherence, and concerns

- Concurrent validity of dynamic bedside quantitative sensory testing paradigms in breast cancer survivors with persistent pain

- Transcranial direct current stimulation is more effective than pregabalin in controlling nociceptive and anxiety-like behaviors in a rat fibromyalgia-like model

- Paradox pain sensitivity using cuff pressure or algometer testing in patients with hemophilia

- Physical activity with person-centered guidance supported by a digital platform or with telephone follow-up for persons with chronic widespread pain: Health economic considerations along a randomized controlled trial

- Measuring pain intensity through physical interaction in an experimental model of cold-induced pain: A method comparison study

- Pharmacological treatment of pain in Swedish nursing homes: Prevalence and associations with cognitive impairment and depressive mood

- Neck and shoulder pain and inflammatory biomarkers in plasma among forklift truck operators – A case–control study

- The effect of social exclusion on pain perception and heart rate variability in healthy controls and somatoform pain patients

- Revisiting opioid toxicity: Cellular effects of six commonly used opioids

- Letter to the Editor

- Post cholecystectomy pain syndrome: Letter to Editor

- Response to the Letter by Prof Bordoni

- Response – Reliability and measurement error of exercise-induced hypoalgesia

- Is the skin conductance algesimeter index influenced by temperature?

- Skin conductance algesimeter is unreliable during sudden perioperative temperature increase

- Corrigendum

- Corrigendum to “Chronic post-thoracotomy pain after lung cancer surgery: a prospective study of preoperative risk factors”

- Obituary

- A Significant Voice in Pain Research Björn Gerdle in Memoriam (1953–2024)