Abstract

Objectives

Fatigue is common in patients with chronic pain. Still, there is a lack of studies examining objectively measurable cognitive aspects of fatigue: cognitive fatigability (CF). We aimed to investigate the presence of CF in patients with chronic pain and its relation to self-rated fatigue, attention, pain characteristics, sleep disturbance, depression, and anxiety.

Methods

Two hundred patients with chronic pain and a reference group of 36 healthy subjects underwent a comprehensive neuropsychological test battery, including measurement of CF with the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-III Coding subtest, and self-assessment of trait and state fatigue.

Results

The patients with chronic pain did not show more CF as compared to the reference group. There was an association between CF and processing speed on a test of sustained and selective attention in the chronic pain group, while self-rated fatigue measures and pain characteristics were not associated with CF. Self-rated fatigue measures were highly correlated with self-rated pain intensity, spreading of pain, depression, anxiety, and sleep disturbance.

Conclusions

The findings highlight the distinction between objective and subjective aspects of fatigue in chronic pain, and that the underlying causes of these different aspects of fatigue need to be studied further.

1 Introduction

Fatigue is common among patients with chronic pain and is considered one of the most disabling symptoms [1,2]. Besides fatigue, patients with chronic pain often report cognitive symptoms and previous studies confirm that pain is associated with impaired attention, memory, processing speed, and executive function [3–5].

Fatigue and cognitive dysfunction might share underlying mechanisms. One model used to explain cognitive deficits in chronic pain is the limited resource theory, which postulates that attention is a limited capacity and that pain signals compete for attentional space, disturbing normal cognitive processing [6,7]. A slightly different perspective comes with the theory of neurocognitive decline [8], proposing that cognitive deficits in patients with chronic pain might be a consequence of pain-related structural alterations in the brain. Those alterations seem to be more pronounced with longer duration of pain [9], higher pain intensity [10], and increasing age [8].

Neurocognitive changes and limited attentional resources as a model of fatigue in patients with chronic pain are insufficiently studied. Though, in neurological conditions, such as traumatic brain injury (TBI), explanatory models for fatigue have been formulated, whereof one explains fatigue by the extra mental energy it costs to compensate for brain injury-related disturbance of the brain’s attentional networks [11].

Fatigue, like pain itself, is most often looked upon as an inherently subjective experience [12] and measured with various self-assessment scales. Those can be designed to capture either momentary “state” fatigue, which is variable and situation-dependent, or “trait” fatigue, i.e., fatigue over a longer period, mirroring a more stable characteristic of a person [13]. While state fatigue is captured using visual analog scales, trait fatigue is measured using uni- or multidimensional self-assessment scales [13]. A common feature of those latter is that they tend to be associated with and sensitive to emotional disorders such as anxiety and depression [14,15] and sleep disorders [16], conditions that are common in patients with chronic pain [17–19].

An alternative way to an objective assessment of cognitive aspects of fatigue is to focus on cognitive fatigability (CF), defined as performance decline on tasks requiring sustained mental effort [20,21], and captured as decreased task accuracy [22,23], increased response time [24], or as an increased intraindividual performance variability [25]. Studies on patients with neurological conditions have shown that CF can be induced during a short task if sufficiently cognitively demanding [26,27].

It is acknowledged that there tends to be low accordance between subjective, self-assessed (trait) fatigue and objectively measured CF. CF, as opposed to subjective fatigue, seems to be unrelated to emotional factors such as depression [26], and it has been proposed that the conditions might even be independent of each other [28,29].

CF has hitherto mainly been investigated in patients with multiple sclerosis and TBI, and patients with those conditions do overall show more CF than healthy controls [30]. Whether patients with chronic pain are also afflicted by objectively measurable CF has, to our knowledge, not been studied.

1.1 Aims

The primary aim of this study was to investigate the presence of CF in patients with chronic pain and its relation to attention functions and self-rated fatigue.

A secondary, explorative aim was to examine the impact of intensity, duration, and spreading of pain, along with depression, anxiety, and sleep disturbance, on the different fatigue measures.

Based on previous research in neurological populations, we hypothesized a higher degree of CF in patients with chronic pain than in a reference group without pain. Further, we expected an association between attention functions and CF. Trait fatigue, but not CF nor state fatigue, was expected to be associated with depression, anxiety, and sleep disturbances.

2 Materials and methods

All data were collected from a large clinical trial (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT05452915). Detailed information on the measures can be obtained from the study protocol [31].

2.1 Participants

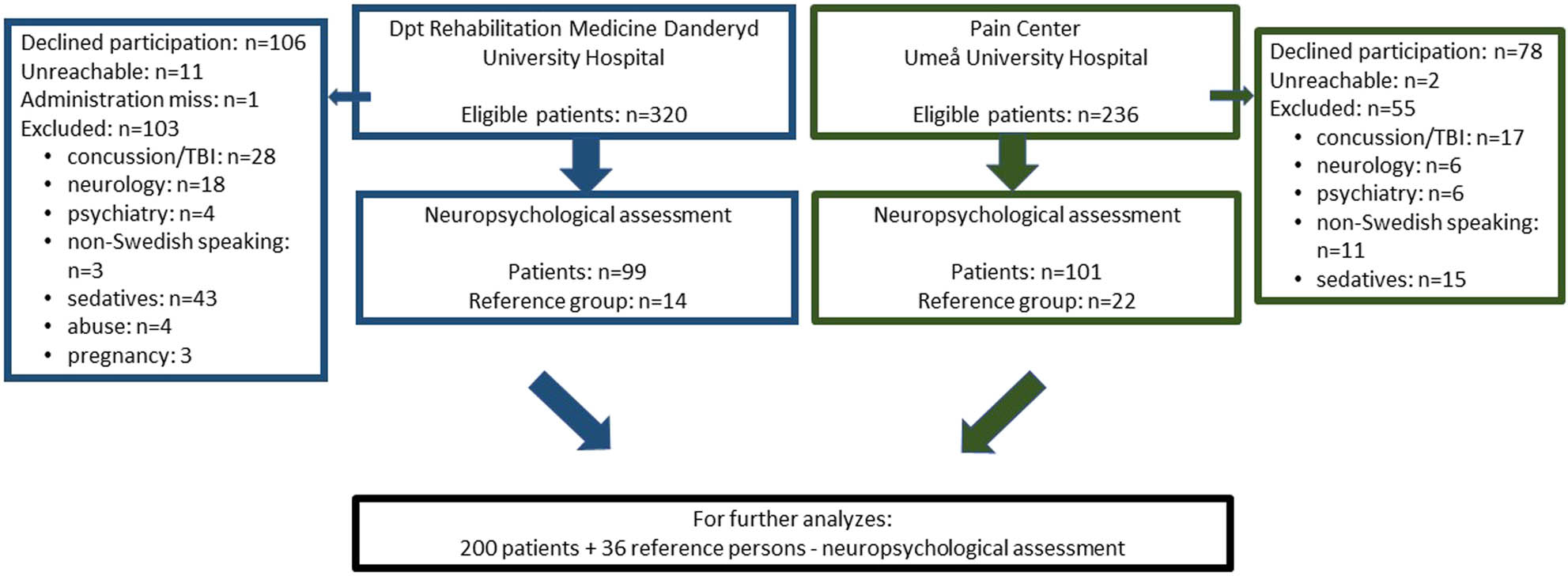

Two hundred consecutively enrolled patients between 18 and 50 years, 30 men and 170 women, with chronic pain were compared with a reference group of 36 healthy persons (Figure 1).

Flow chart of the study.

2.2 Inclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria are as follows: Chronic pain, duration >3 months, according to the International Association for the Study of Pain definition [32]; age 18–50 years; referral for team assessment due to chronic pain.

2.3 Exclusion criteria

Exclusion criteria are as follows: Acquired brain injury (including concussion), severe psychiatric disorder, intellectual disability, medication potentially affecting cognitive functions (e.g., sedatives, opioids), pregnancy, and non-fluency in the Swedish language. Regarding the healthy controls, chronic or present pain was also an exclusion criterion.

3 Procedure

3.1 Recruitment

All patients who underwent team assessment at the Unit of Pain Rehabilitation at the Department of Rehabilitation Medicine, Danderyd University Hospital, or at the Unit of Pain Rehabilitation, Pain Center at Umeå University Hospital from September 2018 to May 2022 were eligible for inclusion and received written and verbal information about the study. The reference group was a convenience sample, recruited among hospital staff or their friends.

3.2 Neuropsychological assessment

Patients and controls underwent a neuropsychological testing session in an outpatient setting, in which ratings of fatigue and pain-level and demographical questions were included. A neuropsychologist not involved in the patients’ rehabilitation administered the tests in a fixed order. All assessments were performed during office hours.

Background information concerning pain (Table 1), Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), and Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) data were obtained from the Swedish Quality Register for Pain Rehabilitation (http://www.ucr.uu.se/nrs/). The reference group completed the scales during the testing session.

Clinical and demographic data for patients and the reference group

| Patients n = 200 | Reference group n = 36 | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 33.3 (8.5) | 33.0 (9.2) | 0.823 |

| Female, n (%) | 170 (91.7%) | 33 (85%) | 0.215 |

| Education years | 13.2 (2.3) | 14.6 (2.0) | 0.001 |

| Matrix reasoning | 18.9 (4.4) | 19.2 (3.2) | 0.593 |

| Scaled score = 9 | Scaled score = 9 | ||

| Pain duration years* | 9.0 (7.1) | N/A | |

| Spreading of pain** | 16.3 (8.1) | N/A |

*n = 164, **n = 184. Data are mean values (standard deviations) and counts (percentages). The normative scores were obtained on a group level from the Wechsler et al. [33] test manual.

4 Measurements

4.1 Primary outcome measure

4.1.1 Digit symbol coding test – fatigability (Coding-f)

The Digit-Symbol-Coding (Coding) test from WAIS-III [33] measures psychomotor processing speed, attention, and working memory. The task has executive components and demands coordination of several cognitive modalities [34] and has, as such, been proposed to be used as a CF measurement [35]. Short duration tasks such as Coding, the Symbol digits modalities test [36], and the Paced Auditory Serial Addition Test (PASAT) [37] have all been used for this purpose in patients with brain injury and neurological conditions [26,30,38,39]. The task is to pair symbols with numbers for 120 s. The production of symbols is supposed to increase over time as an effect of learning [35]. CF was measured both as a dichotomized variable, defined as a non-ascending score (<0) when the produced numbers during the last 30 s of the task are subtracted from the number produced during the first 30 s, and as a continuous variable. The continuous variable was reported as the percentage of produced numbers during the first 30 s (number of symbols in the first 30 s/total number of symbols × 100) subtracted from the percentage of completed numbers in the last 30 s of the task (number of correct answers in the last 30 s/total number of symbols × 100) [26].

Incidental memory of the symbols was assessed after the task.

4.2 Secondary outcome measures

4.2.1 Ruff 2 & 7 selective attention test (Ruff 2 & 7)

Ruff 2 & 7 [40] is a visual attention test assessing sustained and selective attention while also evaluating processing speed. The task is to identify and cancel the target digits (2 and 7) among distractors: either letters (automatic sustained attention) or numbers (controlled selective attention), in random order. Higher scores mean better performance. Performance was evaluated according to the test manual.

4.2.2 Digit span

Verbal attention span was assessed with Digit span forward (Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale) [41]. The higher the value obtained, the better the result.

4.2.3 Matrix reasoning

Matrix reasoning [41] measures non-verbal logical reasoning and is considered robust to cognitive decline [42]. Higher scores indicate better performance. The test was used to compare potential differences in premorbid level between patients and the reference group.

For all neuropsychological measurements, raw data were primarily used for comparison. In addition, normative scores were used to describe the level of performance. Scaled scores have a mean of 10 and a standard deviation of 3, and T-scores have a mean of 50 and a standard deviation of 10.

4.2.4 Multidimensional fatigue inventory-20, general fatigue subscale (MFI-20-GF)

The MFI-20 [43] is a multidimensional questionnaire consisting of five subscales: “General fatigue,” “Physical fatigue,” “Reduced activities,” “Reduced motivation,” and “Mental fatigue.” Each scale consists of four items that are rated on a 5-point Likert scale. The higher the value, the more the fatigue. Since the scale does not provide a total score, in this study the General fatigue (GF) subscale, encompassing both physical and psychological aspects of fatigue, and which has been suggested to be used as a short form of the questionnaire [43], was applied to measure trait fatigue.

4.2.5 Visual analog scale of fatigue (VAS-f)

State fatigue was measured using a 100 mm VAS-f, ranging from 0 (no fatigue) to 100 (worst fatigue imaginable). VAS-f was administered before and after the neuropsychological assessment. The value before the assessment was used as a measurement of state fatigue. Subjective fatigability (VAS-f d-value) was measured by subtracting the VAS-f value obtained before assessment from the value obtained after assessment, higher value indicates more subjective fatigability.

4.2.6 ISI

Symptoms of disturbed sleep were assessed with ISI [44], which is a well-validated, comprehensive unidimensional self-report scale on a 5-point Likert scale. The maximal score is 28. Higher values reflect more symptoms, and a cutoff score of 10 is optimal in balancing specificity and sensitivity [45].

4.2.7 HADS

HADS [46] consists of two subscales, depression (HADS-D) and anxiety (HADS-A). Both subscales range from 0 to 21, with scores >10 indicating a high risk of depression and anxiety, respectively.

4.2.8 Pain intensity scoring (PIS)

Pain intensity throughout the assessment was verbally rated on a Numeric Rating Scale from 0 (no pain) to 10 (worst pain imaginable) at the end of the testing session.

4.2.9 Spreading of pain

The spreading of pain was measured as the number of painful sites on the body, based on 36 predefined anatomical areas, covering the four quadrants of the body, 18 on the front and 18 on the back [47].

4.2.10 Statistics/data analysis

Parametric methods were used for normally distributed data on a ratio level. Independent samples t-test was used to compare groups, while paired samples t-test was used for comparison within groups. ANCOVA was applied to adjust for confounding variables. To investigate pattern differences during the Coding test, the number of digits for each quartile was analyzed with repeated measures. Pearson correlation was used for the analysis of the association between variables. Non-parametric methods were used for variables on the interval level. Mann–Whitney U test was used for comparison between groups on continuous non-parametric data. Chi2 was applied for categorical data. For analysis of associations between variables on the interval level, Spearman’s rank was used. Due to the relatively small size of the reference group correlations between variables were only calculated for the chronic pain group. The significance level for all analyses was set to p < 0.05 (2-tailed). Data were analyzed in IBM SPSS, version 22.

5 Results

5.1 Demographics

There were no differences in gender, age, or estimated premorbid intellectual level (matrix reasoning) between the chronic pain group and the reference group. The reference group, though, had a significantly higher educational level (Table 1). The chronic pain group had a mean duration of pain of 9 years and a mean number of pain locations of 16 out of 36 (Table 1). The mean current pain rating was 5 out of 10 at the time of the neuropsychological assessment (Table 2).

Self-rated measurements of fatigue, pain, sleep disturbance, anxiety, and depression

| Patients n = 200 | Reference group n = 36 | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MFI-20 GF | 18.0 (8–20) | 8.0 (4–16) | <0.001 |

| VAS-fatigue pre-assessment | 50.4 (21.6) | 24.0 (15.9) | <0.001 |

| VAS-fatigue post-assessment | 67.4 (20.5) | 33.5 (23.9) | <0.001 |

| VAS-fatigue d-value | 17.0 (17.0) | 9.6 (20.1) | 0.020 |

| PIS | 5.0 (0–9) | N/A | |

| HADS D* | 8.0 (0–19) | 1.0 (0–6) | <0.001 |

| HADS A* | 9.0 (0–21) | 5.0 (0–15) | <0.001 |

| ISI** | 15.0 (0–28) | 4.5 (0–14) | <0.001 |

*n = 189, **n = 185. MFI, multidimensional fatigue inventory-20 general fatigue; VAS, visual analog scale; PIS, pain intensity scoring; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; ISI, Insomnia Severity Index.

Mean and standard deviations for ratio data, median, and range for interval data.

5.2 Group differences

There was no significant difference in CF between the chronic pain group and the reference group (Table 3). The result did not change when the effect of higher education in the reference group was adjusted for. To investigate if there was a difference in response pattern, we also recorded the number of symbols produced in each time unit (quartile), but we found no response difference between the groups. However, a significant difference in self-rated fatigability during the neuropsychological assessment (VAS-f-d-value) emerged, with patients being more fatigued than the reference group (Table 2).

Measurements of CF and attention

| Patients n = 200 | Reference group n = 36 | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coding % fatigability* | 0.63 (4.0) | 0.61 (6.1) | 0.977 |

| Coding % fatigability 1 outlier removed | 0.63 (4.0) | 1.40 (3.8) | 0.288 |

| Coding total | 68.2 (15.3) | 75.1 (13.0) | 0.011 |

| Scaled score = 8 | Scaled score = 10 | ||

| Coding incidental memory (pairing)** | 5.8 (2.6) | 6.3 (1.8) | 0.140 |

| Cum% = 26–50 | Cum% = 26–50 | ||

| Ruff 2 & 7 ADS*** | 132.7 (31.4) | 131.3 (29.0) | 0.803 |

| T-score = 41 | T-score = 40 | ||

| Ruff 2 & 7 CSS*** | 110.7 (22.8) | 110.1 (20.4) | 0.893 |

| T-score = 37 | T-score = 36 | ||

| Digit span (forward digits) | 5.7 (1.0) | 6.0 (0.8) | 0.163 |

| Cum% = 71.4 | Cum% = 71.4 |

There were no significant correlations between demographic factors, i.e., educational level and age, on CF in the chronic pain group.

The chronic pain group reported significantly higher rates of fatigue than the reference group, both trait fatigue (MFI-20 GF) and state fatigue (VAS-f), before the neuropsychological examination. The chronic pain group did also report significantly higher rates of anxiety (HADS-A) and depression (HADS-D) than the reference group (Table 2).

No significant differences between the groups were found in the measurements of attention (Ruff ADS, Ruff CSS, Digit span) or memory (Coding Incidental memory). Compared to the test norms, both groups performed in the lower normal range on Ruff ADS and slightly below the normal range on Ruff CSS. The result of Coding incidental memory was within the normal range for both groups (Table 3).

5.3 Association between CF and different attention measurements within the chronic pain group

There was a significant but weak correlation between CF and automatic processing speed (Ruff 2 & 7 ADS) (r = 0.158, p = 0.029) and controlled processing speed (Ruff 2 & 7 CSS) (r = 0.213, p = 0.003) within the patient group. Also, when CF was dichotomized, there was a significant difference in processing speed between fatigued and non-fatigued subjects (Table 4). There was no significant correlation between CF and attention span (Digit span) nor between trait (MFI-20) or state (VAS-f) fatigue and attention as measured with Ruff ADS and CSS, Digit span, and Coding total.

Attention in fatigued/non-fatigued subjects, Coding-f being dichotomized

| Patients fatigued n = 89 | Patients non-fatigued n = 106 | p-value | Reference group fatigued n = 16 | Reference group non-fatigued n = 20 | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ruff 2 & 7 ADS | 126.9 (32.1) | 136.2 (29.1) | 038 | 128.6 (23.2) | 133.5 (33.4) | 0.627 |

| Ruff 2 & 7 CSS | 105.4 (23.2) | 113.9 (20.4) | 007 | 106.6 (14.1) | 113.0 (24.3) | 0.363 |

| Digit span (forward digits) | 5.7 (1.0) | 5.8 (1.1) | 541 | 6.0 (0.6) | 6.0 (1.0) | 0.856 |

The data are mean (standard deviation). ADS, automatic detection speed; CSS controlled search speed.

5.4 Association between CF and self-rated measurements within the chronic pain group

There was no significant correlation between CF and subjective fatigability (VAS-f-d value) nor between CF and measures of trait fatigue (MFI-20 GF), state fatigue (VAS-f), or pain duration. Neither were there any significant correlations between CF and pain intensity (PIS), spreading of pain, or sleep disturbance (ISI), nor between CF and anxiety (HADS A) or depression (HADS D).

5.5 Intercorrelations of self-rated measurements within the chronic pain group

There were significant intercorrelations between anxiety (HADS-A), depression (HADS-D), sleep disturbance (ISI), current pain intensity (PIS), trait (MFI-20 GF), and state (VAS-f) fatigue in the chronic pain group (Table 5). Spreading of pain correlated significantly with all the variables except for anxiety (HADS-A). Pain duration was neither related to state fatigue nor trait fatigue.

Correlations (Spearman) of subjective measurements within the chronic pain group

| VAS-f | MFI-GF | PIS | HADS D | HADS A | ISI | Spreading of pain | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VAS-f | r = 0.46*** | r = 0.34*** | r = 0.18* | r = 0.27*** | r = 0.21** | r = 0.21** | |

| MFI-GF | r = 0.46*** | r = 0.21** | r = 0.37*** | r = 0.27*** | r = 0.38*** | r = 0.25** | |

| PIS | r = 0.34*** | r = 0.21** | r = 0.21** | r = 0.16* | r = 0.30*** | r = 0.20* | |

| HADS D | r = 0.18* | r = 0.37*** | r = 0.21** | r = 0.53*** | r = 0.33*** | r = 0.20* | |

| HADS A | r = 0.27*** | r = 0.27*** | r = 0.16* | r = 0.53*** | r = 0.27*** | ns | |

| ISI | r = 0.21** | r = 0.38*** | r = 0.30*** | r = 0.33*** | r = 0.27*** | r = 0.30** | |

| Spreading of pain | r = 0.21** | r = 0.25** | r = 0.20* | r = 0.20* | ns | r = 0.30** |

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. VAS-f, visual analog scale of fatigue; MFI-GF, multidimensional fatigue inventory-20, general fatigue; PIS, pain intensity scoring; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; ISI, Insomnia Severity Index.

6 Discussion

This study primarily aimed at investigating CF in patients with chronic pain and its relation to self-rated fatigue and attention functions. We also aimed to explore the impact of pain characteristics, sleep disturbance, and emotional factors on the results.

There was, at odds with our hypothesis, no significant difference in CF between patients with chronic pain and the reference group without pain. However, in line with our assumption, we found an association between CF and measurements of processing speed and sustained and selective attention (Ruff 2 & 7) within the chronic pain group. The association between CF and the more executively demanding selective attention task condition was stronger as compared to the sustained, automatic condition, in line with the notion that CF is particularly triggered by tasks demanding higher-order cognitive control [26,48]. This also holds as an explanation for the lack of association between CF and attention span, the latter not requiring executive processing nor sustained attention, thus not fulfilling the prerequisites for tasks prone to induce CF.

Noteworthy, when the CF measure, Coding-f, was dichotomized, based on ascending versus non-ascending scores, a great portion (46%) of the chronic pain patients showed non-ascending scores, indicating CF, and one might speculate that this mirrors the existence of subgroups of chronic pain patients more prone to CF than others. However, almost the same percentage of fatigued subjects was found in the reference group (44%). This is indeed a significantly higher amount than the 19% cognitively fatigued healthy controls found in a previous study with Coding-f as measurement [26], and further evaluation of the instrument is needed to elucidate the pattern of results in healthy subjects.

A broader question concerns whether the use of Coding-f is the most suitable way to assess CF in chronic pain. Particularly the PASAT, in which the task is to sum new numbers with previous presented ones in a series, has been successful in capturing CF in patients with MS. One distinguishing factor between Coding and PASAT is that the tempo cannot be altered in the PASAT. The numbers are presented at a fixed speed, whereas in Coding, the patients can adjust the pace of their performance according to their needs. This characteristic of the PASAT might make it more susceptible to CF than the Coding task. It is worth noting that the patients demonstrated significantly slower performance compared to the reference persons, further supporting the potential advantages of utilizing a test where the patients cannot compensate for a lack of attention by lowering the processing speed, which can mask fatigue in otherwise more demanding contexts. However, Holtzer et al. [49] have shown that 35 min of executively demanding work is warranted to induce CF in healthy older adults, and it cannot be ruled out that a task of longer duration would have been needed to elicit CF in patients with chronic pain.

While the chronic pain group reported more fatigue than the reference group on both trait and state measures, including subjective fatigability during the neuropsychological examination, cognitive measurements did not differ between the chronic pain group and the reference group, except for Coding, total score. However, compared to normative test scores, both groups performed in the lower normal range on Ruff ADS and slightly below the normal range on Ruff CSS. Those tasks have in common their dependency on processing speed, which appears to be particularly vulnerable to chronic pain. The results are in line with the young age of the subjects, the majority being in their early thirties, since other cognitive domains appear to be more resistant, with deficits uncommonly seen before middle age, possibly due to compensatory mechanisms in the young [8]. This is consistent with the theory of neurocognitive decline, as MRI data show that structural pain-related changes in the brain are more pronounced in older ages [9], reducing compensatory capacity. This phenomenon might be further elucidated using task-fMRI. If patients with chronic pain compensate with increased cerebral effort, they would show altered connectivity compared to healthy controls, even if they perform on a normal level. Note, there was no significant correlation between age and CF in this study, which could be explained by the narrow age-span of the sample.

No pain-related factors correlated with CF and no association was found between subjective state or trait fatigue and CF. In fact, no subjective measure correlated with CF in the chronic pain group. Instead, the results clearly showed that measures of subjective fatigue, be it trait fatigue, fatigue at the moment, or fatigability during the neuropsychological examination, strongly correlated with each other as well as with ratings of intensity and spreading of pain, sleep disturbance, anxiety, and depression. The hypothesis that state fatigue, being situational, transient, and effort-dependent [50], as opposed to trait fatigue, would be free-standing from emotional states, as indicated by Möller et al. [51], was thus not confirmed in this study. However, in Möller et al.’s study the patients were newly injured (within 7 days) mild TBI patients, and state fatigue was measured with the Rivermead Post Concussion Questionnaire, where the present level of fatigue was compared with fatigue level before injury. Different conditions and different time perspectives make comparisons problematic, and the results from this study are in accordance with those of Manierre et al. [52], demonstrating a strong association between trait and state fatigue in a sample of healthy subjects.

High correlations in the subjective measurements could also mirror a response style, i.e., a tendency to be a high or low rater in self-assessment forms, hypothetically overshadowing nuances in experience. Nevertheless, the results point, consistently with previous findings in neurological populations [28], to a clear dissociation between subjective and objective measures of fatigue in patients with chronic pain, subjective fatigue being highly associated with emotional factors as opposed to CF and other cognitive measures.

6.1 Strengths and limitations

A strength of the study is that it was a multicenter study based on pain centers at two university clinics with experienced staff. Other strengths are the exclusion of patients taking analgesics with cognitive side effects, which might have confounded the results, the use of well-validated measures and scales, and the inclusion of a reference group.

A limitation of the study was the small size of the reference group, making it underpowered and vulnerable to outliers as compared to the patient group. To compensate for this, normative test scores were included when available. Also, the reference group had slightly higher education, but this was controlled for in the statistical analysis.

There was a clear gender imbalance among the participants in the study, with about 90% being women, which mirrors that most patients admitted to pain rehabilitation indeed are women. The low number of men limited the possibility to analyze gender differences in the study, and the generalization of the results to the male population should be done with caution.

Another limitation was the restricted age span of the participants. The upper limit was purposely set at 50 years to avoid confounding effects of age-associated cognitive decline, though, at the cost of generalizability to older ages.

It warrants to be commented that the correlational design of the study prevents conclusions about causality, i.e., whether pain causes fatigue or vice versa, to be drawn from the data. Previous studies giving evidence in both directions though suggest a bidirectional association [53–55].

6.2 Clinical implications

The results of the present study reveal a subgroup of patients suffering from attention deficits and CF, and who might benefit from attention training or other tailored interventions. To identify those patients at an early stage of the rehabilitation, the implementation of a cognitive screening as a standard diagnostical tool in the team assessment could be an option.

7 Conclusion

In conclusion, this study did not give support for CF as a prominent feature of patients with chronic pain. There was, though, an association between CF and processing speed in attention-demanding tests, most salient in an executively demanding condition, indicating an association between processing speed and CF in chronic pain. The patients with chronic pain showed elevated rates of trait as well as state fatigue compared to a reference group. Those measurements were strongly correlated with other subjective measures, but not with CF nor cognition, clearly pointing to a distinction between objective and subjective measures of fatigue. Still, the underlying mechanisms behind CF in this subgroup remain unclear. Future studies should elucidate whether factors associated with attention deficits might be explanatory. Future studies should also investigate the possible impact of the type of pain on CF and fatigue.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the patients and the reference persons for their participation in the study, and the clinical staff for assisting in the recruitment of patients.

-

Research ethics: The study was approved by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority (2018/424-31; 2018/1235-32; 2018/2395-32; 2019-66148; 2022-02838-02) and performed according to the declaration of Helsinki.

-

Informed consent: Informed consent has been obtained from all individuals included in this study.

-

Author contributions: Conceptualization and design, all authors; acquisition of data, A.H. and N.B.; analysis and interpretation of data; A.H. in collaboration with M.C.M. A.H. wrote the manuscript draft. All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Competing interests: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

-

Research funding: This study was funded by Stiftelsen Promobilia (no. A22056), the Department of Clinical Sciences, Karolinska Institutet, and through a regional agreement between Umeå University and Västerbotten County Council on cooperation in the field of Medicine, Odontology, and Health.

-

Ethical committee number: Swedish Ethical Review Authority (Dnr 2018/424-31; 2018/1235–32; 2018/2395–32; 2019–66148; 2022-02838-02). Trial registry number: ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT05452915.

-

Data availability: The raw data can be obtained on request from the corresponding author.

References

[1] Hart RP, Martelli MF, Zasler ND. Chronic pain and neuropsychological functioning. Neuropsychol Rev. 2000;10(3):131–49.10.1023/A:1009020914358Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[2] Creavin ST, Dunn KM, Mallen CD, Nijrolder I, van der Windt DA. Co-occurrence and associations of pain and fatigue in a community sample of Dutch adults. Eur J Pain. 2010;14(3):327–34.10.1016/j.ejpain.2009.05.010Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[3] Higgins DM, Martin AM, Baker DG, Vasterling JJ, Risbrough V. The relationship between chronic pain and neurocognitive function: a systematic review. Clin J Pain. 2018;34(3):262–75.10.1097/AJP.0000000000000536Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[4] Karp JF, Reynolds CF, 3rd Butters MA, Dew MA, Mazumdar S, Begley AE, et al. The relationship between pain and mental flexibility in older adult pain clinic patients. Pain Med. 2006;7(5):444–52.10.1111/j.1526-4637.2006.00212.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[5] Berryman C, Stanton TR, Bowering KJ, Tabor A, McFarlane A, Moseley GL. Do people with chronic pain have impaired executive function? A meta-analytical review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2014;34(7):563–79.10.1016/j.cpr.2014.08.003Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] Grisart J, Van der Linden M, Masquelier E. Controlled processes and automaticity in memory functioning in fibromyalgia patients: relation with emotional distress and hypervigilance. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2002;24(8):994–1009.10.1076/jcen.24.8.994.8380Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[7] Legrain V, Damme SV, Eccleston C, Davis KD, Seminowicz DA, Crombez G. A neurocognitive model of attention to pain: behavioral and neuroimaging evidence. Pain. 2009;144(3):230–2.10.1016/j.pain.2009.03.020Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[8] Oosterman JM, Veldhuijzen DS. On the interplay between chronic pain and age with regard to neurocognitive integrity: two interacting conditions? Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2016;69:174–92.10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.07.009Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] Baliki MN, Schnitzer TJ, Bauer WR, Apkarian AV. Brain morphological signatures for chronic pain. PLoS One. 2011;6(10):e26010.10.1371/journal.pone.0026010Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[10] Apkarian AV, Sosa Y, Sonty S, Levy RM, Harden RN, Parrish TB, et al. Chronic back pain is associated with decreased prefrontal and thalamic gray matter density. J Neurosci. 2004;24(46):10410–5.10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2541-04.2004Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[11] McAllister TW, Sparling MB, Flashman LA, Guerin SJ, Mamourian AC, Saykin AJ. Differential working memory load effects after mild traumatic brain injury. Neuroimage. 2001;14(5):1004–12.10.1006/nimg.2001.0899Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[12] Dittner AJ, Wessely SC, Brown RG. The assessment of fatigue: a practical guide for clinicians and researchers. J Psychosom Res. 2004;56(2):157–70.10.1016/S0022-3999(03)00371-4Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[13] Genova HM, Rajagopalan V, Deluca J, Das A, Binder A, Arjunan A, et al. Examination of cognitive fatigue in multiple sclerosis using functional magnetic resonance imaging and diffusion tensor imaging. PLoS One. 2013;8(11):e78811.10.1371/journal.pone.0078811Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[14] Arnold LM. Understanding fatigue in major depressive disorder and other medical disorders. Psychosomatics. 2008;49(3):185–90.10.1176/appi.psy.49.3.185Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[15] Manning K, Kauffman BY, Rogers AH, Garey L, Zvolensky MJ. Fatigue severity and fatigue sensitivity: relations to anxiety, depression, pain catastrophizing, and pain severity among adults with severe fatigue and chronic low back pain. Behav Med. 2022;48(3):181–9.10.1080/08964289.2020.1796572Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[16] Akerstedt T, Knutsson A, Westerholm P, Theorell T, Alfredsson L, Kecklund G. Mental fatigue, work and sleep. J Psychosom Res. 2004;57(5):427–33.10.1016/j.jpsychores.2003.12.001Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[17] Mease P, Arnold LM, Bennett R, Boonen A, Buskila D, Carville S, et al. Fibromyalgia syndrome. J Rheumatol. 2007;34(6):1415–25.Search in Google Scholar

[18] Moriarty O, McGuire BE, Finn DP. The effect of pain on cognitive function: a review of clinical and preclinical research. Prog Neurobiol. 2011;93(3):385–404.10.1016/j.pneurobio.2011.01.002Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[19] Fishbain DA, Cole B, Cutler RB, Lewis J, Rosomoff HL, Fosomoff RS. Is pain fatiguing? A structured evidence-based review. Pain Med. 2003;4(1):51–62.10.1046/j.1526-4637.2003.03008.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[20] Schwid SR, Tyler CM, Scheid EA, Weinstein A, Goodman AD, McDermott MP. Cognitive fatigue during a test requiring sustained attention: a pilot study. Mult Scler. 2003;9(5):503–8.10.1191/1352458503ms946oaSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[21] Bryant D, Chiaravalloti ND, DeLuca J. Objective measurement of cognitive fatigue in multiple sclerosis. Rehabil Psychol. 2004;49(2):114.10.1037/0090-5550.49.2.114Search in Google Scholar

[22] Morrow SA, Rosehart H, Johnson AM. Diagnosis and quantification of cognitive fatigue in multiple sclerosis. Cogn Behav Neurol. 2015;28(1):27–32.10.1097/WNN.0000000000000050Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[23] Walker LA, Berard JA, Berrigan LI, Rees LM, Freedman MS. Detecting cognitive fatigue in multiple sclerosis: method matters. J Neurol Sci. 2012;316(1–2):86–92.10.1016/j.jns.2012.01.021Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[24] Berard JA, Fang Z, Walker LAS, Lindsay-Brown A, Osman L, Cameron I, et al. Imaging cognitive fatigability in multiple sclerosis: objective quantification of cerebral blood flow during a task of sustained attention using ASL perfusion fMRI. Brain Imaging Behav. 2020;14(6):2417–28.10.1007/s11682-019-00192-7Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[25] Wang C, Ding M, Kluger BM. Change in intraindividual variability over time as a key metric for defining performance-based cognitive fatigability. Brain Cogn. 2014;85:251–8.10.1016/j.bandc.2014.01.004Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[26] Moller MC, Nygren de Boussard C, Oldenburg C, Bartfai A. An investigation of attention, executive, and psychomotor aspects of cognitive fatigability. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2014;36(7):716–29.10.1080/13803395.2014.933779Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[27] De Luca J. Fatigue, cognition and mental effort. Fatigue as a window to the brain. Cambridge: MA. MIT Press; 2005. p. 33–57.10.7551/mitpress/2967.003.0006Search in Google Scholar

[28] Kluger BM, Krupp LB, Enoka RM. Fatigue and fatigability in neurologic illnesses: proposal for a unified taxonomy. Neurology. 2013;80(4):409–16.10.1212/WNL.0b013e31827f07beSearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[29] Tommasin S, De Luca F, Ferrante I, Gurreri F, Castelli L, Ruggieri S, et al. Cognitive fatigability is a quantifiable distinct phenomenon in multiple sclerosis. J Neuropsychol. 2020;14(3):370–83.10.1111/jnp.12197Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[30] Walker LAS, Lindsay-Brown AP, Berard JA. Cognitive fatigability interventions in neurological conditions: a systematic review. Neurol Ther. 2019;8(2):251–71.10.1007/s40120-019-00158-3Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[31] Möller MC, Berginström N, Ghafouri B, Holmqvist A, Löfgren M, Nordin L, et al. Cognitive and mental fatigue in chronic pain: cognitive functions, emotional aspects, biomarkers and neuronal correlates-protocol for a descriptive cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2023;13(3):e068011.10.1136/bmjopen-2022-068011Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[32] Treede RD, Rief W, Barke A, Aziz Q, Bennett MI, Benoliel R, et al. Chronic pain as a symptom or a disease: the IASP Classification of Chronic Pain for the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11). Pain. 2019;160(1):19–27.10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001384Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[33] Wechsler D. WAIS-III Svensk version (M.Hagelthorn, Trans.). Stockholm: Psykologiförlaget AB.; 2003.Search in Google Scholar

[34] Davis AS, Pierson EE. The relationship between the WAIS-III digit symbol Coding and executive functioning. Appl Neuropsychol Adult. 2012;19(3):192–7.10.1080/09084282.2011.643958Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[35] Kaplan E, WAIS-R NI. WAIS-R som neuropsykologiskt instrument. Manual. Stockholm: Psykologiförlaget; 1994.Search in Google Scholar

[36] Smith A. Symbol digit modalities test (SDMT). Manual (Revised). Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services; 1982.Search in Google Scholar

[37] Gronwall DM. Paced auditory serial-addition task: a measure of recovery from concussion. Percept Mot Skills. 1977;44(2):367–73.10.2466/pms.1977.44.2.367Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[38] Kohl AD, Wylie GR, Genova HM, Hillary FG, Deluca J. The neural correlates of cognitive fatigue in traumatic brain injury using functional MRI. Brain Inj. 2009;23(5):420–32.10.1080/02699050902788519Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[39] Gronwall D, Wrightson P. Memory and information processing capacity after closed head injury. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1981;44:889–95.10.1136/jnnp.44.10.889Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[40] Ruff RM, Allen CC. Ruff 2 & 7 Selective Attention Test. Lutz: Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc; 1996.Search in Google Scholar

[41] Wechsler D. Wechsler adult intelligence scale-Fourth Edition: Administration and scoring manual. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 2008.10.1037/t15169-000Search in Google Scholar

[42] Lezak MD. Neuropsychological assessment. New York: Oxford University Press; 2012.Search in Google Scholar

[43] Smets EMA, Garssen B, Bonke B, De Haes JCJM. The multidimensional fatigue inventory (MFI) psychometric qualities of an instrument to assess fatigue. J Psychosom Res. 1995;39(3):315–25.10.1016/0022-3999(94)00125-OSearch in Google Scholar

[44] Bastien CH, Vallières A, Morin CM. Validation of the Insomnia Severity Index as an outcome measure for insomnia research. Sleep Med. 2001;2(4):297–307.10.1016/S1389-9457(00)00065-4Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[45] Morin CM, Belleville G, Bélanger L, Ivers H. The Insomnia Severity Index: psychometric indicators to detect insomnia cases and evaluate treatment response. Sleep. 2011;34(5):601–8.10.1093/sleep/34.5.601Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[46] Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67(6):361–70.10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[47] Gerdle B, Rivano Fischer M, Cervin M, Ringqvist Å. Spreading of pain in patients with chronic pain is related to pain duration and clinical presentation and weakly associated with outcomes of interdisciplinary pain rehabilitation: a cohort study from the Swedish Quality Registry for Pain Rehabilitation (SQRP). J Pain Res. 2021;14:173–87.10.2147/JPR.S288638Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[48] Lorist MM, Boksem MA, Ridderinkhof KR. Impaired cognitive control and reduced cingulate activity during mental fatigue. Brain Res Cogn Brain Res. 2005;24(2):199–205.10.1016/j.cogbrainres.2005.01.018Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[49] Holtzer R, Shuman M, Mahoney JR, Lipton R, Verghese J. Cognitive fatigue defined in the context of attention networks. Neuropsychol Dev Cogn B Aging Neuropsychol Cogn. 2011;18(1):108–28.10.1080/13825585.2010.517826Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[50] Spiteri S, Hassa T, Claros-Salinas D, Dettmers C, Schoenfeld MA. Neural correlates of effort-dependent and effort-independent cognitive fatigue components in patients with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2019;25(2):256–66.10.1177/1352458517743090Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[51] Möller MC, Johansson J, Matuseviciene G, Pansell T, Deboussard CN. An observational study of trait and state fatigue, and their relation to cognitive fatigability and saccade performance. Concussion. 2019;4(2):Cnc62.10.2217/cnc-2019-0003Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[52] Manierre M, Jansen E, Boolani A. Sleep quality and sex modify the relationships between trait energy and fatigue on state energy and fatigue. PLoS One. 2020;15(1):e0227511.10.1371/journal.pone.0227511Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[53] Nicassio PM, Moxham EG, Schuman CE, Gevirtz RN. The contribution of pain, reported sleep quality, and depressive symptoms to fatigue in fibromyalgia. Pain. 2002;100(3):271–9.10.1016/S0304-3959(02)00300-7Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[54] Halder SL, McBeth J, Silman AJ, Thompson DG, Macfarlane GJ. Psychosocial risk factors for the onset of abdominal pain. Results from a large prospective population-based study. Int J Epidemiol. 2002;31(6):1219–25.10.1093/ije/31.6.1219Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[55] Meeus M, Nijs J, Huybrechts S, Truijen S. Evidence for generalized hyperalgesia in chronic fatigue syndrome: a case control study. Clin Rheumatol. 2010;29(4):393–8.10.1007/s10067-009-1339-0Search in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Editorial Comment

- From pain to relief: Exploring the consistency of exercise-induced hypoalgesia

- Christmas greetings 2024 from the Editor-in-Chief

- Original Articles

- The Scandinavian Society for the Study of Pain 2022 Postgraduate Course and Annual Scientific (SASP 2022) Meeting 12th to 14th October at Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen

- Comparison of ultrasound-guided continuous erector spinae plane block versus continuous paravertebral block for postoperative analgesia in patients undergoing proximal femur surgeries

- Clinical Pain Researches

- The effect of tourniquet use on postoperative opioid consumption after ankle fracture surgery – a retrospective cohort study

- Changes in pain, daily occupations, lifestyle, and health following an occupational therapy lifestyle intervention: a secondary analysis from a feasibility study in patients with chronic high-impact pain

- Tonic cuff pressure pain sensitivity in chronic pain patients and its relation to self-reported physical activity

- Reliability, construct validity, and factorial structure of a Swedish version of the medical outcomes study social support survey (MOS-SSS) in patients with chronic pain

- Hurdles and potentials when implementing internet-delivered Acceptance and commitment therapy for chronic pain: a retrospective appraisal using the Quality implementation framework

- Exploring the outcome “days with bothersome pain” and its association with pain intensity, disability, and quality of life

- Fatigue and cognitive fatigability in patients with chronic pain

- The Swedish version of the pain self-efficacy questionnaire short form, PSEQ-2SV: Cultural adaptation and psychometric evaluation in a population of patients with musculoskeletal disorders

- Pain coping and catastrophizing in youth with and without cerebral palsy

- Neuropathic pain after surgery – A clinical validation study and assessment of accuracy measures of the 5-item NeuPPS scale

- Translation, contextual adaptation, and reliability of the Danish Concept of Pain Inventory (COPI-Adult (DK)) – A self-reported outcome measure

- Cosmetic surgery and associated chronic postsurgical pain: A cross-sectional study from Norway

- The association of hemodynamic parameters and clinical demographic variables with acute postoperative pain in female oncological breast surgery patients: A retrospective cohort study

- Healthcare professionals’ experiences of interdisciplinary collaboration in pain centres – A qualitative study

- Effects of deep brain stimulation and verbal suggestions on pain in Parkinson’s disease

- Painful differences between different pain scale assessments: The outcome of assessed pain is a matter of the choices of scale and statistics

- Prevalence and characteristics of fibromyalgia according to three fibromyalgia diagnostic criteria: A secondary analysis study

- Sex moderates the association between quantitative sensory testing and acute and chronic pain after total knee/hip arthroplasty

- Tramadol-paracetamol for postoperative pain after spine surgery – A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study

- Cancer-related pain experienced in daily life is difficult to communicate and to manage – for patients and for professionals

- Making sense of pain in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD): A qualitative study

- Patient-reported pain, satisfaction, adverse effects, and deviations from ambulatory surgery pain medication

- Does pain influence cognitive performance in patients with mild traumatic brain injury?

- Hypocapnia in women with fibromyalgia

- Application of ultrasound-guided thoracic paravertebral block or intercostal nerve block for acute herpes zoster and prevention of post-herpetic neuralgia: A case–control retrospective trial

- Translation and examination of construct validity of the Danish version of the Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia

- A positive scratch collapse test in anterior cutaneous nerve entrapment syndrome indicates its neuropathic character

- ADHD-pain: Characteristics of chronic pain and association with muscular dysregulation in adults with ADHD

- The relationship between changes in pain intensity and functional disability in persistent disabling low back pain during a course of cognitive functional therapy

- Intrathecal pain treatment for severe pain in patients with terminal cancer: A retrospective analysis of treatment-related complications and side effects

- Psychometric evaluation of the Danish version of the Pain Self-Efficacy Questionnaire in patients with subacute and chronic low back pain

- Dimensionality, reliability, and validity of the Finnish version of the pain catastrophizing scale in chronic low back pain

- To speak or not to speak? A secondary data analysis to further explore the context-insensitive avoidance scale

- Pain catastrophizing levels differentiate between common diseases with pain: HIV, fibromyalgia, complex regional pain syndrome, and breast cancer survivors

- Prevalence of substance use disorder diagnoses in patients with chronic pain receiving reimbursed opioids: An epidemiological study of four Norwegian health registries

- Pain perception while listening to thrash heavy metal vs relaxing music at a heavy metal festival – the CoPainHell study – a factorial randomized non-blinded crossover trial

- Observational Studies

- Cutaneous nerve biopsy in patients with symptoms of small fiber neuropathy: a retrospective study

- The incidence of post cholecystectomy pain (PCP) syndrome at 12 months following laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a prospective evaluation in 200 patients

- Associations between psychological flexibility and daily functioning in endometriosis-related pain

- Relationship between perfectionism, overactivity, pain severity, and pain interference in individuals with chronic pain: A cross-lagged panel model analysis

- Access to psychological treatment for chronic cancer-related pain in Sweden

- Validation of the Danish version of the knowledge and attitudes survey regarding pain

- Associations between cognitive test scores and pain tolerance: The Tromsø study

- Healthcare experiences of fibromyalgia patients and their associations with satisfaction and pain relief. A patient survey

- Video interpretation in a medical spine clinic: A descriptive study of a diverse population and intervention

- Role of history of traumatic life experiences in current psychosomatic manifestations

- Social determinants of health in adults with whiplash associated disorders

- Which patients with chronic low back pain respond favorably to multidisciplinary rehabilitation? A secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial

- A preliminary examination of the effects of childhood abuse and resilience on pain and physical functioning in patients with knee osteoarthritis

- Differences in risk factors for flare-ups in patients with lumbar radicular pain may depend on the definition of flare

- Real-world evidence evaluation on consumer experience and prescription journey of diclofenac gel in Sweden

- Patient characteristics in relation to opioid exposure in a chronic non-cancer pain population

- Topical Reviews

- Bridging the translational gap: adenosine as a modulator of neuropathic pain in preclinical models and humans

- What do we know about Indigenous Peoples with low back pain around the world? A topical review

- The “future” pain clinician: Competencies needed to provide psychologically informed care

- Systematic Reviews

- Pain management for persistent pain post radiotherapy in head and neck cancers: systematic review

- High-frequency, high-intensity transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation compared with opioids for pain relief after gynecological surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis

- Reliability and measurement error of exercise-induced hypoalgesia in pain-free adults and adults with musculoskeletal pain: A systematic review

- Noninvasive transcranial brain stimulation in central post-stroke pain: A systematic review

- Short Communications

- Are we missing the opioid consumption in low- and middle-income countries?

- Association between self-reported pain severity and characteristics of United States adults (age ≥50 years) who used opioids

- Could generative artificial intelligence replace fieldwork in pain research?

- Skin conductance algesimeter is unreliable during sudden perioperative temperature increases

- Original Experimental

- Confirmatory study of the usefulness of quantum molecular resonance and microdissectomy for the treatment of lumbar radiculopathy in a prospective cohort at 6 months follow-up

- Pain catastrophizing in the elderly: An experimental pain study

- Improving general practice management of patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain: Interdisciplinarity, coherence, and concerns

- Concurrent validity of dynamic bedside quantitative sensory testing paradigms in breast cancer survivors with persistent pain

- Transcranial direct current stimulation is more effective than pregabalin in controlling nociceptive and anxiety-like behaviors in a rat fibromyalgia-like model

- Paradox pain sensitivity using cuff pressure or algometer testing in patients with hemophilia

- Physical activity with person-centered guidance supported by a digital platform or with telephone follow-up for persons with chronic widespread pain: Health economic considerations along a randomized controlled trial

- Measuring pain intensity through physical interaction in an experimental model of cold-induced pain: A method comparison study

- Pharmacological treatment of pain in Swedish nursing homes: Prevalence and associations with cognitive impairment and depressive mood

- Neck and shoulder pain and inflammatory biomarkers in plasma among forklift truck operators – A case–control study

- The effect of social exclusion on pain perception and heart rate variability in healthy controls and somatoform pain patients

- Revisiting opioid toxicity: Cellular effects of six commonly used opioids

- Letter to the Editor

- Post cholecystectomy pain syndrome: Letter to Editor

- Response to the Letter by Prof Bordoni

- Response – Reliability and measurement error of exercise-induced hypoalgesia

- Is the skin conductance algesimeter index influenced by temperature?

- Skin conductance algesimeter is unreliable during sudden perioperative temperature increase

- Corrigendum

- Corrigendum to “Chronic post-thoracotomy pain after lung cancer surgery: a prospective study of preoperative risk factors”

- Obituary

- A Significant Voice in Pain Research Björn Gerdle in Memoriam (1953–2024)

Articles in the same Issue

- Editorial Comment

- From pain to relief: Exploring the consistency of exercise-induced hypoalgesia

- Christmas greetings 2024 from the Editor-in-Chief

- Original Articles

- The Scandinavian Society for the Study of Pain 2022 Postgraduate Course and Annual Scientific (SASP 2022) Meeting 12th to 14th October at Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen

- Comparison of ultrasound-guided continuous erector spinae plane block versus continuous paravertebral block for postoperative analgesia in patients undergoing proximal femur surgeries

- Clinical Pain Researches

- The effect of tourniquet use on postoperative opioid consumption after ankle fracture surgery – a retrospective cohort study

- Changes in pain, daily occupations, lifestyle, and health following an occupational therapy lifestyle intervention: a secondary analysis from a feasibility study in patients with chronic high-impact pain

- Tonic cuff pressure pain sensitivity in chronic pain patients and its relation to self-reported physical activity

- Reliability, construct validity, and factorial structure of a Swedish version of the medical outcomes study social support survey (MOS-SSS) in patients with chronic pain

- Hurdles and potentials when implementing internet-delivered Acceptance and commitment therapy for chronic pain: a retrospective appraisal using the Quality implementation framework

- Exploring the outcome “days with bothersome pain” and its association with pain intensity, disability, and quality of life

- Fatigue and cognitive fatigability in patients with chronic pain

- The Swedish version of the pain self-efficacy questionnaire short form, PSEQ-2SV: Cultural adaptation and psychometric evaluation in a population of patients with musculoskeletal disorders

- Pain coping and catastrophizing in youth with and without cerebral palsy

- Neuropathic pain after surgery – A clinical validation study and assessment of accuracy measures of the 5-item NeuPPS scale

- Translation, contextual adaptation, and reliability of the Danish Concept of Pain Inventory (COPI-Adult (DK)) – A self-reported outcome measure

- Cosmetic surgery and associated chronic postsurgical pain: A cross-sectional study from Norway

- The association of hemodynamic parameters and clinical demographic variables with acute postoperative pain in female oncological breast surgery patients: A retrospective cohort study

- Healthcare professionals’ experiences of interdisciplinary collaboration in pain centres – A qualitative study

- Effects of deep brain stimulation and verbal suggestions on pain in Parkinson’s disease

- Painful differences between different pain scale assessments: The outcome of assessed pain is a matter of the choices of scale and statistics

- Prevalence and characteristics of fibromyalgia according to three fibromyalgia diagnostic criteria: A secondary analysis study

- Sex moderates the association between quantitative sensory testing and acute and chronic pain after total knee/hip arthroplasty

- Tramadol-paracetamol for postoperative pain after spine surgery – A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study

- Cancer-related pain experienced in daily life is difficult to communicate and to manage – for patients and for professionals

- Making sense of pain in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD): A qualitative study

- Patient-reported pain, satisfaction, adverse effects, and deviations from ambulatory surgery pain medication

- Does pain influence cognitive performance in patients with mild traumatic brain injury?

- Hypocapnia in women with fibromyalgia

- Application of ultrasound-guided thoracic paravertebral block or intercostal nerve block for acute herpes zoster and prevention of post-herpetic neuralgia: A case–control retrospective trial

- Translation and examination of construct validity of the Danish version of the Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia

- A positive scratch collapse test in anterior cutaneous nerve entrapment syndrome indicates its neuropathic character

- ADHD-pain: Characteristics of chronic pain and association with muscular dysregulation in adults with ADHD

- The relationship between changes in pain intensity and functional disability in persistent disabling low back pain during a course of cognitive functional therapy

- Intrathecal pain treatment for severe pain in patients with terminal cancer: A retrospective analysis of treatment-related complications and side effects

- Psychometric evaluation of the Danish version of the Pain Self-Efficacy Questionnaire in patients with subacute and chronic low back pain

- Dimensionality, reliability, and validity of the Finnish version of the pain catastrophizing scale in chronic low back pain

- To speak or not to speak? A secondary data analysis to further explore the context-insensitive avoidance scale

- Pain catastrophizing levels differentiate between common diseases with pain: HIV, fibromyalgia, complex regional pain syndrome, and breast cancer survivors

- Prevalence of substance use disorder diagnoses in patients with chronic pain receiving reimbursed opioids: An epidemiological study of four Norwegian health registries

- Pain perception while listening to thrash heavy metal vs relaxing music at a heavy metal festival – the CoPainHell study – a factorial randomized non-blinded crossover trial

- Observational Studies

- Cutaneous nerve biopsy in patients with symptoms of small fiber neuropathy: a retrospective study

- The incidence of post cholecystectomy pain (PCP) syndrome at 12 months following laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a prospective evaluation in 200 patients

- Associations between psychological flexibility and daily functioning in endometriosis-related pain

- Relationship between perfectionism, overactivity, pain severity, and pain interference in individuals with chronic pain: A cross-lagged panel model analysis

- Access to psychological treatment for chronic cancer-related pain in Sweden

- Validation of the Danish version of the knowledge and attitudes survey regarding pain

- Associations between cognitive test scores and pain tolerance: The Tromsø study

- Healthcare experiences of fibromyalgia patients and their associations with satisfaction and pain relief. A patient survey

- Video interpretation in a medical spine clinic: A descriptive study of a diverse population and intervention

- Role of history of traumatic life experiences in current psychosomatic manifestations

- Social determinants of health in adults with whiplash associated disorders

- Which patients with chronic low back pain respond favorably to multidisciplinary rehabilitation? A secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial

- A preliminary examination of the effects of childhood abuse and resilience on pain and physical functioning in patients with knee osteoarthritis

- Differences in risk factors for flare-ups in patients with lumbar radicular pain may depend on the definition of flare

- Real-world evidence evaluation on consumer experience and prescription journey of diclofenac gel in Sweden

- Patient characteristics in relation to opioid exposure in a chronic non-cancer pain population

- Topical Reviews

- Bridging the translational gap: adenosine as a modulator of neuropathic pain in preclinical models and humans

- What do we know about Indigenous Peoples with low back pain around the world? A topical review

- The “future” pain clinician: Competencies needed to provide psychologically informed care

- Systematic Reviews

- Pain management for persistent pain post radiotherapy in head and neck cancers: systematic review

- High-frequency, high-intensity transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation compared with opioids for pain relief after gynecological surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis

- Reliability and measurement error of exercise-induced hypoalgesia in pain-free adults and adults with musculoskeletal pain: A systematic review

- Noninvasive transcranial brain stimulation in central post-stroke pain: A systematic review

- Short Communications

- Are we missing the opioid consumption in low- and middle-income countries?

- Association between self-reported pain severity and characteristics of United States adults (age ≥50 years) who used opioids

- Could generative artificial intelligence replace fieldwork in pain research?

- Skin conductance algesimeter is unreliable during sudden perioperative temperature increases

- Original Experimental

- Confirmatory study of the usefulness of quantum molecular resonance and microdissectomy for the treatment of lumbar radiculopathy in a prospective cohort at 6 months follow-up

- Pain catastrophizing in the elderly: An experimental pain study

- Improving general practice management of patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain: Interdisciplinarity, coherence, and concerns

- Concurrent validity of dynamic bedside quantitative sensory testing paradigms in breast cancer survivors with persistent pain

- Transcranial direct current stimulation is more effective than pregabalin in controlling nociceptive and anxiety-like behaviors in a rat fibromyalgia-like model

- Paradox pain sensitivity using cuff pressure or algometer testing in patients with hemophilia

- Physical activity with person-centered guidance supported by a digital platform or with telephone follow-up for persons with chronic widespread pain: Health economic considerations along a randomized controlled trial

- Measuring pain intensity through physical interaction in an experimental model of cold-induced pain: A method comparison study

- Pharmacological treatment of pain in Swedish nursing homes: Prevalence and associations with cognitive impairment and depressive mood

- Neck and shoulder pain and inflammatory biomarkers in plasma among forklift truck operators – A case–control study

- The effect of social exclusion on pain perception and heart rate variability in healthy controls and somatoform pain patients

- Revisiting opioid toxicity: Cellular effects of six commonly used opioids

- Letter to the Editor

- Post cholecystectomy pain syndrome: Letter to Editor

- Response to the Letter by Prof Bordoni

- Response – Reliability and measurement error of exercise-induced hypoalgesia

- Is the skin conductance algesimeter index influenced by temperature?

- Skin conductance algesimeter is unreliable during sudden perioperative temperature increase

- Corrigendum

- Corrigendum to “Chronic post-thoracotomy pain after lung cancer surgery: a prospective study of preoperative risk factors”

- Obituary

- A Significant Voice in Pain Research Björn Gerdle in Memoriam (1953–2024)