Abstract

Objectives

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a chronic, gastrointestinal tract condition, in which pain is one of the most widespread and debilitating symptoms, yet research about how individuals make sense of their IBD pain is lacking. The current study aimed to explore how individuals with IBD understand their pain.

Methods

Twenty participants, recruited via the Crohn’s & Colitis UK charity, were interviewed about their understanding of their IBD pain using the Grid Elaboration Method that elicits free associations on which it invites elaboration. Thematic analysis was used to organise transcribed verbatim data.

Results

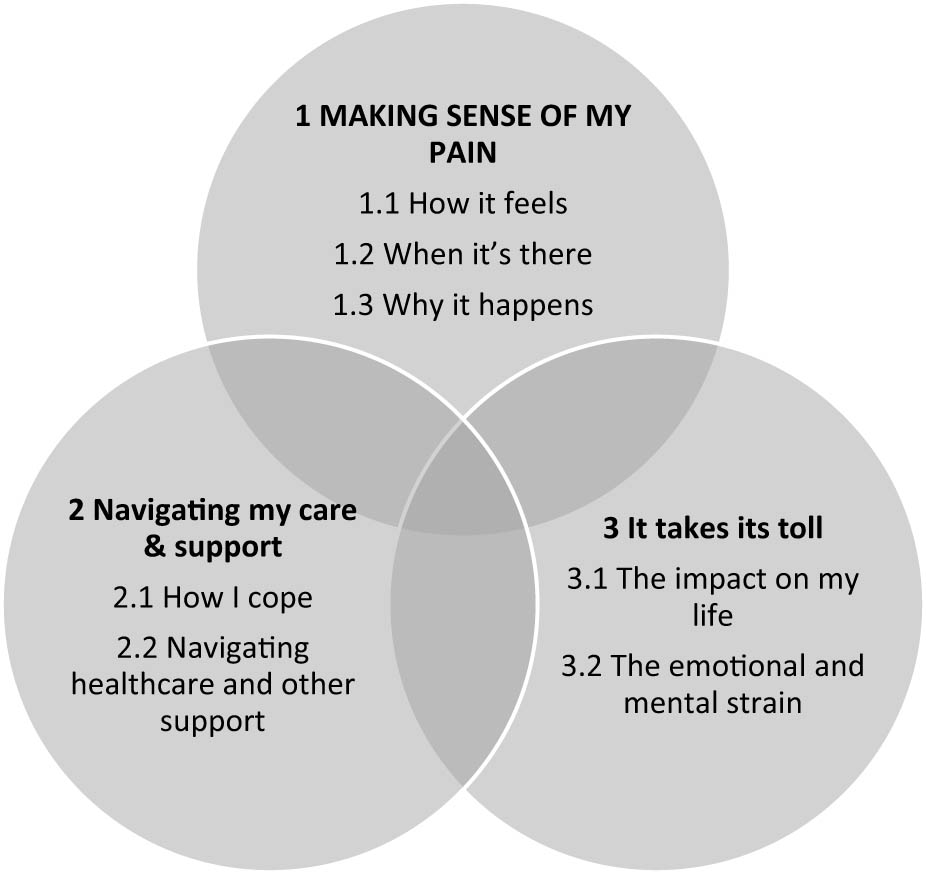

Three related themes – making sense of my pain, navigating my care and support and it takes its toll – comprising seven sub-themes, illustrated the ways in which participants made sense of pain experientially, multi-dimensionally, and in the broader context of IBD and its symptoms. The psychological impact of pain was evident across all interviews.

Conclusions

The findings are consistent with other research in IBD pain, demonstrating the importance of pain in IBD. Sense-making underpins both emotional and practical responses to pain and ideally is constructed as an integral part of clinical care of IBD.

1 Introduction

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a chronic, inflammatory, gastrointestinal disease, comprising two main conditions: Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. As well as pain, both have a range of debilitating symptoms, such as bloating, fatigue, diarrhoea, and weight loss [1]. Symptoms fluctuate, and individuals with IBD often experience flare-ups between which are periods of remission, but while around 70% of people with IBD experience pain during active disease periods, at least 20% of individuals continue to experience pain during disease remission [2]. It has become clear that inflammation is not the only cause of pain [3]; acute flares can indicate disease deterioration [4], but central nervous system dysregulation and increased visceral sensitivity may play a part [2,5].

Both IBD pain and other unpredictable symptoms reduce the quality of life [6,7] and psychological wellbeing [8]. Effective management approaches are lacking [5]. Work on the brain–gut axis in IBD [9,10] emphasises the importance of considering psychosocial factors in an integrated way [11,12]. However, we know little of how people with IBD understand their pain, particularly when it cannot be simply attributed to the current state of the disease [13].

The dominant psychosocial models emphasise fear (of pain or injury), behavioural avoidance of feared physical demands, and subsequent loss of valued activities and roles [14]. Two qualitative studies have explored this area [15,16]. The inpatient IBD population [15] provided healthcare-related themes in addition to misunderstanding, frustration with constant pain, and stigma, whereas the outpatient IBD population [16] described cycles of anxiety about symptoms, attempts to manage pain based on trial and error, and an overall stance from defeat to acceptance of IBD. Both emphasised the need for further research into IBD, its assessment, and management of its physical and emotional components.

The current study therefore aimed to explore how individuals understand their IBD-related pain. Given the likely focus in medical appointments around IBD on disease markers rather than illness experience [17,18], understanding of pain may be very diverse [19]. The study aimed to elicit rich and uninhibited data on how individuals make sense of their visceral discomfort and pain, what meanings they assign to it, and what they may have learned about their pain from varied sources.

2 Methods

2.1 Design and setting

The study had ethical approval (UCL: 19517/001). Recruitment was carried out through a large UK charity (Crohn’s & Colitis UK: https://crohnsandcolitis.org.uk/) which advertised for volunteer participants on its website. Given the COVID pandemic and the vulnerability of many people with IBD, interviews were conducted online, allowing participation without travelling.

2.2 Participants

The advertisement carried a link to a Qualtrics webpage with the participant information sheet and consent form. Once a consent form was submitted, the researcher scheduled an interview using the participant’s preferred method of contact (phone or email). The study planned to recruit 15–20 participants. Inclusion criteria, self-declared on the consent form, were that participants were adults (18 years or over), had a diagnosis of Crohn’s or ulcerative colitis for at least 6 months, and could speak English; the exclusion criterion was any significant cognitive impairment.

2.3 Interview

The study used a novel qualitative method, the Grid Elaboration Method (GEM), developed mainly in social psychology research, drawing on existing interview methods [20,21] but aiming to avoid as far as possible bias introduced by the interviewer or by prepared questions. Rather, the method builds on free association methods [21], capturing participants’ spontaneous thoughts or images on what is most pertinent to them. The researcher refined her use of GEM with the help of two volunteers with IBD who completed the task and provided feedback.

At the start of the interview, the researcher (AK) introduced herself and checked the participant’s consent; she explained that there were no right or wrong answers and that she was interested in participants’ opinions as experts in their condition. She then shared her screen to show a numbered two-by-two grid that the participant copied onto a piece of paper. The instructions were then read and shown on the screen: We are interested in your understanding of your IBD pain. Please express what you associate with this, by way of images and/or words. Please elaborate one image/word per box. Sometimes a simple drawing or word can be a good way of portraying your thoughts or feelings. Using four separate boxes allowed participants not to feel obliged to create a coherent narrative; ideas could be varied and even contradictory.

Once completed, participants held the grid to the camera of their device, and the researcher took a screenshot. The researcher explored each box in turn, using prompts such as “tell me about X” and “you mentioned X…(pause)” to encourage further detail until the participant had nothing else to add. When participants described distressing topics, the researcher responded with brief validation and empathic statements to ensure that participants felt comfortable to continue.

At the end of the interview, participants were asked for basic information to contextualise their contributions: age, gender, ethnicity, occupation, type of illness (Crohn’s disease/ulcerative colitis), years affected, and any other conditions/disabilities. They were also asked brief questions about their pain, for example, to rate their pain over the past week. If participants spontaneously elaborated further detail relevant to their grid at this point, they were asked if it should be included in the analysis. Following this, the researcher thanked participants, answered any questions, and re-iterated where to find the study outcomes.

Interviews were transcribed by the researcher using a transcription key [22]; audio files were deleted; transcripts were anonymised; and potentially identifying information was removed. To aid reflexivity in analysis, the researcher made notes following interviews [23], including how the interview felt and initial ideas about potential patterns.

2.4 Researcher perspective

It is important for researchers to state and reflect on the position from which they approach their research [24]. The researcher was a White, Eastern-European/British, middle-class female in her early 30s, completing the project as part of her Clinical Psychology Doctorate and professional qualification. She had clinical experience with chronic pain and fatigue, but not IBD. She had personal experience of gastrointestinal problems and IBS, a condition that is less severe but that symptomatically overlaps with IBD. She also developed long-COVID muscle and joint pain during this research that influenced her perception of chronic pain. During the research, she kept a reflective journal and was supervised by the second author, a Consultant Clinical Psychologist with extensive experience in pain. As a result of exploring beliefs and assumptions about the research in greater depth [25], she conducted a GEM on herself in relation to her IBS pain and reflected on it. The researcher approached the interviews with a belief that visceral pain has been seriously neglected in psychological research on pain and wished to amplify participants’ voices.

2.5 Data analysis

Thematic analysis is a flexible method of finding themes within a data set [26], and the method of choice with GEM [20]. Analysis was inductive, with no specific theory imposed on analytical stages, although researcher biases and assumptions inevitably affected analysis [22]. Analysis followed the well-documented, six-step method in the thematic analysis [26]: familiarisation with the data through transcription (see Table S1, Supplementary Material) and multiple readings; data-driven coding using NVivo software [27]; refinement of codes; continued immersion in the data to review and revise developing themes, while mapping potential overarching themes, themes, and sub-themes [22]; defining and naming the final themes and sub-themes; selecting extracts; and constructing the narrative.

Credibility and validation of the study were ensured through regular supervision, discussion with researchers more familiar with GEM, and following the 15-point quality criteria for thematic analyses [26]. The researcher supervisor and a postgraduate colleague with GEM experience reviewed codes and mapping of themes and sub-themes, but without formal reliability checks, as this belongs to deductive, rather than inductive or reflexive epistemologies [28].

3 Results

Twenty participants took part (Table S2, Supplementary Material), 13 self-identified females and seven males, 20–66 years old (mean 36). Sixteen participants identified as White British, one as White Irish, one as White, and two as Mixed White/Asian. Eleven had Crohn’s disease, seven had ulcerative colitis, and two stated that they had both. Interview length was a median of 53 (range 39–72) minutes.

3.1 Thematic analysis

3.1.1 GEM grids

Most grid boxes contained a single word or idea; only 12 of the 80 grid boxes (4 per participant) used images. Nearly half (37/80) described pain or its qualities; a quarter referred to impact of IBD pain; 13 described feelings; others described comorbid difficulties, management, or were not easily categorised (Figures S1–S3, Supplementary Material).

Thematic analysis provided three themes with seven sub-themes (Figure 1; Table S3, Supplementary Material). Overall, participants made sense of their pain in the context of their healthcare, personal support, and management approaches, all intersecting with how they felt about their pain and about IBD, and how both affected their lives. Quotations below are followed by the participant number (P1–20), self-reported gender (M, F), age bracket, and diagnosis (CD for Crohn’s disease, UC for ulcerative colitis, UC/CD when participants reported both, recognising that they are most unlikely to have been given both diagnoses formally).

Diagrammatic representation of the three themes and seven subthemes; bold, capitalised text indicates central theme.

Theme 1: Making sense of my pain was an overarching theme, encompassing participants’ efforts to understand their pain; how it feels, when it’s there, and why it happens.

Subtheme 1.1: How it feels. Many participants found explaining their pain difficult, because it was unpredictable, and language seemed inadequate.

“It’s a sensation, but I cannot describe it. It’s not pain, it’s like a dull ache, it’s not numb, it’s not hot, it’s not cold, it’s not tingling… there’s no word to describe that specific thing” [P5, M, 25–35, CD]

Descriptions using sensory qualities, location, and comparisons were common:

“like a blender in your stomach or in your colon” [P11, F, 25–35, UC]

“Oh my gosh, it’s awful. It really burns your bottom and it’s explosive, and the pain literally takes… just… it’s awful. It’s even worse than having a child” [P3, F, 55–65, UC/CD]

Non-gastrointestinal pain (e.g. joint pain) linked to IBD or medication was common, as were symptoms such as bloating, nausea, diarrhoea, brain fog, and fatigue:

“Often the pain correlates with the fatigue and it feeds into the fatigue and the fatigue feeds into the pain and then it becomes a bit of a cycle.” [P16, F, 25–35, CD]

Pain shaped individuals’ sense of self and normality:

“You almost don’t know what normal is anymore. And it’s only when you actually feel better that you’re like ‘oh yeah, that’s how it’s supposed to be’.” [P18, F, 45–55, CD]

Subtheme 1.2: When it’s there was important for understanding flares and disease state, choosing management approaches, and reducing impact. Two types of pain were described: a low-level, dull, aching pain, or brief, intense bursts of incapacitating pain:

“For me, there’s that sort of gnawing everyday pain, which moves slowly and then sometimes you have a really big peak within a few seconds.” [P16, F, 25–35, CD]

Pain, particularly in flares, was unpredictable and unrelated to disease state, although some participants reported triggers, most often overactivity, food, stress, or medication.

“You do look back through what you’ve done to try and figure out how you can stop it happening again.” [P15, M, 18–25, UC]

Subtheme 1.3: Why it happens. Participants felt that their efforts to understand IBD pain were often ignored, even dismissed, in healthcare.

“I guess whenever you talk to them [clinicians] about the pain… it’s kind of like, ‘Oh yeah, that’s just part of it.’ For example, … what is it inside me that’s actually hurting? And what is, what’s aggravating it? What can I do to alleviate it?’” [P2, F, 25–35, UC]

More participants expressed confusion about the meaning of pain and wanting to understand it better than had confidence in knowing what pain meant. Pain was attributed to various causes, including passage of food, inflammation, ulcers, obstructions, and strictures. Some interpreted it as a warning sign of possible complications or flare onset:

“… the dull, achy pain I get, I’ve got a stricture, so it’s probably just from food passing through” [P20, M, 18–25, CD]

Reflections on meanings of pain were usually followed by comments about managing it.

“I think [pain is] because that’s where I’ve got a bit of a stricture… that I just need whatever it is to move past that part of my bowel and then things are going to go OK again” [P14, F, 45–55, CD]

Theme 2: Navigating my care and support described a changing landscape over time of complex healthcare and management.

Subtheme 2.1: How I cope. Participants recounted specific ways that they managed pain, including diet, activity pacing, medication or other treatment, and stress management (see subtheme 3), with noticeable differences in the effectiveness of strategies.

More than half of the participants hoped for control, but varied from “it’s uncontrollable” [P1, F, 45–55, CD] to “I feel quite on top of it right now” [P10, F, 18–25, CD]. Difficulties with control were associated with distress and not knowing whether to seek help. Most were disappointed with the treatment for IBD pain and wished for more integrated approaches, and better communication across health teams.

“There’s lots of options like, um, things like alternative therapies or even counselling therapies … ways of helping you manage pain. that they just don’t really offer.” [P8, F, 25–35, CD]

Subtheme 2.2: Navigating healthcare and other support was described in detail, reflecting its importance, but experiences were mixed. Some were resigned to unsatisfactory help, but others were pleased with the support offered.

“My consultant - I’ve got his direct line number at the hospital. If there is a problem, give him a call, you know, I can do that. So, I’m alright.” [P6, M, 45–55, UC]

Support outside healthcare, from family, friends, and wider support systems, was explored and underpinned feeling understood by others. Challenges included difficulty in disclosing symptoms, the invisibility of IBD pain, and confusion with IBS, commonly misrepresented as a trivial or predominantly psychological problem.

Theme 3: It takes its toll described the impacts of IBD, pain, other symptoms, management, and healthcare navigation on participants’ lives.

Subtheme 3.1: Impact on my life. Participants’ ways of managing pain mediated the impact on their lives.

“I can feel that whenever I’m doing something I enjoy very much, the pain goes away a little bit.” [P13, F, 35–45, UC]

Subtheme 3.2: Emotional and mental strain from pain were widely and powerfully described.

“When I’m feeling that pain – when I’ve got the inflammation in my gut – it’s scarring. And as those scars build up, more problems build up. But I also think psychologically, it leaves a mark.” [P14, F, 45–55, CD]

Anxiety and stress, both as triggers and outcomes of pain, were associated with the unpredictability of IBD pain.

“I’ve had other consultations where I’ve been told that my pain is due to stress, but then been offered no way of dealing with that stress or the pain associated.” [P8, F, 25–35, CD]

Feeling sad about missing valued activities was, for some, associated with guilt and fear of being a burden, but nearly half of the participants also spoke about hope, and most compared themselves positively to others:

“Some people’s conditions are way worse than mine.” [P18, F, 45–55, CD]

4 Discussion

This study aimed to deepen understanding of how individuals with IBD make sense of their pain; GEM methodology allowed participants to address and discuss what felt most important to them about understanding their IBD pain. Consistent with other research on the impact of pain and IBD-related symptoms [1,13,29], we found that people make sense of their pain experientially, within the context of IBD: participants’ elaborations moved fluidly between disease, pain, and associated symptoms across the whole body that further lowered quality of life [30].

The study, unconstrained by researcher questions, provided three intersecting themes from participants’ varied accounts. How individuals made sense of their pain was connected with their reflections around navigating care and management, as well as the impact of pain. Most participants contextualised their explanation of current impact of pain in a narrative of their condition and encounters with health care, emotional and practical. The majority of interviews included a marked social component concerning being heard and supported, within and outside healthcare (subtheme 2.2), and various largely negative interpersonal consequences of pain (subtheme 3.2). Frustrations about not being heard were shared with other IBD research [15] and represent the challenges that chronic pain presents for interpersonal needs, such as the need to belong, and for autonomy [31,32], concerns rarely addressed in health care.

Absent from the grids and elaborations were standard explanations of IBD pain in relation to inflammation, although inflammation was implicated in many elaborations: in describing different types of pain, flares, presumed or established triggers, and medical management. Some participants stated that they would like more information and were unsure why they experienced pain or what it signalled. Across the sample, pain was assigned many meanings, ranging from food passing through inflamed areas to serious concerns such as an obstruction or bowel perforation. Many participants found the term ‘remission’ of limited utility, given that pain often persisted in remission [2].

Visceral sensations, including pain, were often expressed in analogies or metaphors, with mixed accounts of interpreting the intensity of pain as likelihood of a serious complication. However, some participants inferred from particular pains (and other sensations) that particular processes were underway, with specific anxieties and responses (including seeking health care) associated with those pains. This is highly consistent with the common-sense model of self-regulation [33] that describes a health threat prompting meaning-making, with affective components and decisions about appropriate action. Illness representations [34], how individuals understand their illness, are central parts of the commonsense model of self-regulation and inform coping strategies.

Participants’ accounts were less consistent with the standard fear and avoidance psychological model of chronic pain [14,35], or the mutually reinforcing but not interlinked cycles of fear and avoidance in IBD pain described by Sweeney et al. [16]. Some participants’ accounts did fit the model, with vigilance to even minor symptoms or sensations as threat cues, and anxiety about IBD-related medical emergencies undermining coping and generating avoidance of planned activities, despite the longer-term negative impact on quality of life [36]. No grid entries explicitly specified inflammation, perforation, or other medical complications, and while there was considerable variation in the extent to which participants worried about risks of strictures and perforation, to describe it as catastrophic thinking [37] implies a judgement of ‘excessive’ worry. Some participants described monitoring their symptoms without accompanying anxiety or overwhelming impact on their lives, while others avoided activity in the context of resignation, fatigue, or hopelessness about the pain and pain control. Continued meaningful activity, despite pain, helped to alleviate suffering and improve mood for some participants, although this was often situation-specific and dependent on the severity of pain.

Grid entries and elaborations used many emotion terms, perhaps as a function of being self-selected volunteers speaking to a psychologist researcher. While emotions were usually described as reactions to pain, some reflections alluded to the bi-directional nature of emotions, stress in particular, and other narratives showed implicit awareness of emotional effects on the gut [9]. Although not focused on IBD pain, Keen et al. [19] also found a strong experiential component in GEM interviews that explored how individuals with various chronic pains understood their pain; the open-ended format may elicit more wholistic accounts.

5 Strengths and limitations

This is the first study to focus specifically on how individuals with IBD understand their pain. More people volunteered to take part than could be accommodated, and there were many positive comments about the need for more research on IBD pain. The GEM methodology is relatively novel [20], and little used in pain [but see 19]. Its application here yielded rich and detailed data unconstrained by researcher interview focus, and was positively received by participants. The lack of researcher shaping of the content is also a disadvantage, in that it prevented deeper questioning on meanings of pain.

Although all participants had repeatedly received health care for investigation, diagnosis and treatment, it may be that they differed from clinical populations of people with chronic pain, including visceral pain, and that this underlies differences in psychological findings from those in mixed chronic pain populations [38]. An alternative explanation is that the standard fear and avoidance model, arising as it did mainly from studies of people with chronic musculoskeletal pain, may best fit a minority of people with chronic visceral pain, perhaps represented in greater proportions in clinical samples. Participants’ difficulties accessing healthcare during the COVID-19 pandemic may also have made them more inclined to take an opportunity to convey their distress.

Twelve participants referred to the pandemic and its challenges, such as obtaining health care. For some, pain had increased with stresses or fewer distractions, while others reported being less stressed and tired, making IBD more manageable. There were also reflections on how the pandemic facilitated societal recognition of living in fear of infections or illness and highlighted discrimination against people with long-term conditions or disabilities.

The context of the COVID-19 pandemic also imposed limitations in terms of the study design. All interviews were conducted online, which may have excluded some participants, although it allowed others to take part who would not have travelled to meet the researcher, and technological problems affected a few interviews. Online conversation can have comparable levels of rapport and openness in therapy to face-to-face format [39]. Given the underrepresentation of ethnic minority groups in medical research [40], the sample would have benefitted from greater diversity; although IBD presents similarly in Black and White populations, impact and healthcare use can differ [41], as may health care in pain [42]. One of the two mixed-race participants in this study spoke of how her ethnicity and culture shaped her experiences with pain and navigating healthcare. In the context of social graces [43], three participants commented on gendered differences in managing the emotional burden of pain. Comments on age were mainly about the difficulties for young patients, not least those whose IBD had started in adolescence, in being diagnosed correctly.

6 Implications

The purpose of qualitative research is not generalisation, but common themes can usefully be considered in a wider context [22]. First, pain appears to be under-addressed in clinical consultations for IBD [44,45], and although pain is included in the clinical severity scale for Crohn’s disease [46], it is not present in the four-item scale for ulcerative colitis [46]. Pain assessment has been recommended as an inherent part of IBD consultations [44,46], and discussing patients’ beliefs about causes and appropriate actions can enhance self-management.

Second, our study demonstrates the difficulties that individuals with IBD face in constructing a coherent narrative of their pain and knowing how best to manage it; trial and error produced mixed results. Better information could inform patients’ internal models of pain [34] and thereby foster more effective self-management of pain [30], although pain education has rather small effects [47,48] and we need to understand more about what information individuals retain and how they process it. Personalised information, tailored by the clinician to the patient’s account, is likely to be rather more effectively implemented than generic education [49]. Attention to psychological components that could influence pain in IBD [10] also seems desirable [49], particularly for those individuals who tend towards worries about medical emergencies that they manage by withdrawal from safe and rewarding activities, possibly with overuse of emergency health care.

Third, pain clinicians may have a useful contribution to make in care of people with IBD, offering a wider range of approaches than typically offered in primary or IBD-specialist care. It could include a discussion of patients’ understanding of pain, with the provision of information about pain mechanisms as necessary [49], and support in determining effective management and regaining abandoned but valued activities.

Further research could build on this study in various ways; comparing understanding of pain in different visceral pain conditions with larger samples and clinical populations, where anxieties about serious complications may be more prominent; and evaluating attempts to incorporate pain and its impact in clinical gastroenterological consultations.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Crohn’s & Colitis UK for support with recruitment, and Professor Christine Norton for her advice and ideas, which were invaluable during the data analysis stage. We would also like to thank the DClinPsy examiners, Dr Kathy White (University College London), and Dr Andrew Hunter (National University of Ireland), for their thoughtful reflections that helped to shape the final article.

-

Research ethics: Research involving human subjects complied with all relevant national regulations, institutional policies and is in accordance with the tenets of the Helsinki Declaration (as amended in 2013), and has been approved by the authors’ Institutional review board (UCL: 19517/001).

-

Informed consent: Informed consent has been obtained from all individuals included in this study.

-

Author contributions: Both authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission. AK and AW jointly designed the study; AK conducted the interviews, transcribed them, and analysed the results, with AW conducting checks on application of codes to sections of transcript; AK wrote an extended account of the research for her doctoral thesis; AW drafted the paper from this extended account; both authors repeatedly edited the paper. AK created the figures and tables.

-

Competing interests: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: None declared.

-

Data availability: Full codes mapped to themes are available with exemplar sections of transcript from the corresponding author.

-

Supplementary Material: This article contains supplementary material (followed by the link to the article online).

References

[1] Norton C, Syred J, Kerry S, Artom M, Sweeney L, Hart A, et al. Supported online self-management versus care as usual for symptoms of fatigue, pain and urgency/incontinence in adults with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD-BOOST): study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2021;22:516. 10.1186/s13063-021-05466-4.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[2] Bielefeldt K, Davis B, Binion DG. Pain and inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:778–88. 10.1002/ibd.20848.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[3] Srinath A, Young E, Szigethy E. Pain management in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: translational approaches from bench to bedside. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20:2433–49. 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000170.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[4] Zeitz J, Ak M, Muller-Mottet S, Scharl S, Biedermann L, Fournier N, et al. Pain in IBD Patients: Very frequent and frequently insufficiently taken into account. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0156666. 10.1371/journal.pone.0156666.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[5] Norton C, Czuber-Dochan W, Artom M, Sweeney L, Hart A. Systematic review: Interventions for abdominal pain management in inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;46:115–25. 10.1111/apt.14108.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] Coates MD, Seth N, Clarke K, Abdul-Baki H, Mahoney N, Walter V, et al. Opioid analgesics do not improve abdominal pain or quality of life in Crohn’s disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2020;65:2379–87. 10.1007/s10620-019-05968-x.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[7] Knowles SR, Graff LA, Wilding H, Hewitt C, Keefer L, Mikocka-Walus A. Quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease: A systematic review and meta-analyses - Part I. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2018;24:742–51. 10.1093/ibd/izx100.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[8] Mikocka-Walus AA, Turnbull DA, Moulding NT, Wilson IG, Andrews JM, Holtmann GJ. Controversies surrounding the comorbidity of depression and anxiety in inflammatory bowel disease patients: A literature review. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007;13:225–34. 10.1002/ibd.20062.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] Barbara G, Cremon C, Stanghellini V. Inflammatory bowel disease and irritable bowel syndrome: similarities and differences. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2014;30:352–8. 10.1097/MOG.0000000000000070.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[10] Bonaz BL, Bernstein CN. Brain-gut interactions in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:36–49. 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.10.003.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] Drossman DA. Gastrointestinal illness and the biopsychosocial model [Literature Review]. Psychosom Med. 1998;60:258–67. 10.1097/00006842-199805000-00007.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[12] Turk DC, Wilson H, Swanson KS. The biopsychosocial model of pain and pain management. In: Ebert M, Kerns R, editors. Behavioral and psychopharmacologic pain management. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2011. p. 16–43.10.1017/CBO9780511781445.003Suche in Google Scholar

[13] Trivedi I, Darguzas E, Balbale SN, Bedell A, Reddy S, Rosh JR, et al. Patient understanding of “Flare” and “Remission” of inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2019;42:375–85. 10.1097/SGA.0000000000000373.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[14] Vlaeyen JW, Crombez G, Linton SJ. The fear-avoidance model of pain. Pain. 2016;157:1588–9. 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000574.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[15] Bernhofer EI, Masina VM, Sorrell J, Modic MB. The pain experience of patients hospitalized with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2017;40:200–7. 10.1097/SGA.0000000000000137.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[16] Sweeney L, Moss-Morris R, Czuber-Dochan W, Belotti L, Kabeli Z, Norton C. ‘It’s about willpower in the end. You’ve got to keep going’: A qualitative study exploring the experience of pain in inflammatory bowel disease. Br J Pain. 2019;13:201–13. 10.1177/2049463719844539.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[17] Czuber-Dochan W, Norton C, Bredin F, Darvell M, Nathan I, Terry H. Healthcare professionals’ perceptions of fatigue experienced by people with IBD. J Crohns Colitis. 2014;8:835–44. 10.1016/j.crohns.2014.01.004.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[18] Dibley L, Norton C. Experiences of fecal incontinence in people with inflammatory bowel disease: self-reported experiences among a community sample. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19:1450–62. 10.1097/MIB.0b013e318281327f.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[19] Keen S, Lomeli-Rodriguez M, Williams ACdeC. Exploring how people with chronic pain understand their pain: A qualitative study. Scand J Pain. 2021;21:743–53. 10.1515/sjpain-2021-0060.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[20] Joffe H, Elsey JW. Free association in psychology and the grid elaboration method. Rev Gen Psychol. 2014;18:173–85. 10.1037/gpr0000014.Suche in Google Scholar

[21] Hollway W, Jefferson T. Doing qualitative research differently: A psychosocial approach. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2012.10.4135/9781526402233Suche in Google Scholar

[22] Braun V, Clarke V. Successful qualitative research: A practical guide for beginners. London, UK: SAGE; 2013.Suche in Google Scholar

[23] Phillippi J, Lauderdale J. A guide to field notes for qualitative research: Context and conversation. Qual Health Res. 2018;28:381–8. 10.1177/1049732317697102.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[24] Barker C, Pistrang N. Quality criteria under methodological pluralism: implications for conducting and evaluating research. Am J Community Psychol. 2005;35:201–12. 10.1007/s10464-005-3398-y.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[25] Hill CE, Knox S, Thompson BJ, Williams EN, Hess SA, Ladany N. Consensual qualitative research: An update. J Couns Psychol. 2005;52:196–205. 10.1037/0022-0167.52.2.196.Suche in Google Scholar

[26] Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3:77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.Suche in Google Scholar

[27] Lumivero, NVivo (Version 13, R1); 2020. www.lumivero.com, Accessed 25.01.24Suche in Google Scholar

[28] Braun V, Clarke V. One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis. Qual Res Psychol. 2021;18(3):328–52. 10.1080/14780887.2020.1769238.Suche in Google Scholar

[29] Huisman D, Sweeney L, Bannister K, Moss-Morris R. Irritable bowel syndrome in inflammatory bowel disease: distinct, intertwined, or unhelpful? Views and experiences of patients. Cogent Psychol. 2022;9:2050063. 10.1080/23311908.2022.2050063.Suche in Google Scholar

[30] Palm O, Bernklev T, Moum B, Gran JT. Non-inflammatory joint pain in patients with inflammatory bowel disease is prevalent and has a significant impact on health related quality of life. J Rheumatol. 2005;32:1755–9.Suche in Google Scholar

[31] Karos K, Williams ACdeC, Meulders A, Vlaeyen JW. Pain as a threat to the social self: A motivational account. Pain. 2018;159:1690–5. 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001257.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[32] Williams ACdeC, Craig KD. Updating the definition of pain. Pain. 2016;157:2420–3. 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000613.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[33] Leventhal H, Phillips LA, Burns E. The common-sense model of self-regulation (CSM): A dynamic framework for understanding illness self-management. J Behav Med. 2016;39:935–46. 10.1007/s10865-016-9782-2.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[34] Leventhal H, Benyamini Y, Brownlee S, Diefenbach M, Leventhal EA, Patrick-Miller L, et al. Illness representations: Theoretical foundations, Chapter 1. In: Weinman J, Petrie K, editors. Perceptions of health and illness. London, UK: Harwood Publishers; 1997. p. 19–46.Suche in Google Scholar

[35] Crombez G, Eccleston C, Van Damme S, Vlaeyen JW, Karoly P. Fear-avoidance model of chronic pain: the next generation. Clin J Pain. 2012;28:475–83. 10.1097/AJP.0b013e3182385392.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[36] Zale EL, Ditre JW. Pain-related fear, disability, and the fear-avoidance model of chronic pain. Curr Opin Psychol. 2015;5:24–30. 10.1016/j.copsyc.2015.03.014.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[37] Sullivan MJL, Thorn B, Haythornthwaite JA, Keefe F, Martin M, Bradley LA, et al. Theoretical perspectives on the relation between catastrophizing and pain. Clin J Pain. 2001;17:53–61. 10.1097/00002508-200103000-00008.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[38] Morley S, Eccleston C, Williams A. Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of cognitive behaviour therapy and behaviour therapy for chronic pain in adults, excluding headache. Pain. 1999;80:1–13. 10.1016/s0304-3959(98)00255-3.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[39] Andersson G. Internet-delivered psychological treatments. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2016;12:157–79. 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-021815-093006.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[40] Smart A, Harrison E. The under-representation of minority ethnic groups in UK medical research. Ethn Health. 2017;22:65–82. 10.1080/13557858.2016.1182126.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[41] Straus WL, Eisen GM, Sandler RS, Murray SC, Sessions JT. Crohn’s Disease: Does race matter? Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:479–83. 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.t01-1-01531.x.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[42] Peacock S, Patel S. Cultural influences on pain. Rev Pain. 2008;1:6–9. 10.1177/204946370800100203.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[43] Burnham J. Developments in Social GRRRAAACCEEESSS: Visible–invisible and voiced–unvoiced 1. In Culture and reflexivity in systemic psychotherapy. Abingdon, UK: Routledge; 2018. p. 139–60.10.4324/9780429473463-7Suche in Google Scholar

[44] Bakshi N, Berry S, Aziz Q, Glatter J. The challenge of treating chronic pain in inflammatory bowel disease. Br J Healthc Manag. 2021;27:182–4. 10.12968/BJHC.2021.0086.Suche in Google Scholar

[45] Kemp K, Dibley L, Chauhan U, Greveson K, Jaghult S, Ashton K, et al. Second N-ECCO consensus statements on the European nursing roles in caring for patients with Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis. J Crohns Colitis. 2018;12:760–76. 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjy020.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[46] Torres J, Mehandru S, Colombel JF, Peyrin-Biroulet L. Crohn’s disease. Lancet. 2017;389:1741–55. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31711-1.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[47] IBD UK. IBD standards core statements; 2019. https://s3.eu-west-2.amazonaws.com/files.ibduk.org/documents/IBD-Standards-Core-Statements.pdf?mtime=20190708142622&focal=none. Accessed 25.01.24. Watson JA, Ryan CG, Cooper L, Ellington D, Whittle R, Lavender M, et al. Pain neuroscience education for adults with chronic musculoskeletal pain: A mixed-methods systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pain. 2019;20:1140.e1–e22. 10.1016/j.jpain.2019.02.011.10.1016/j.jpain.2019.02.011Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[48] Tegner H, Frederiksen P, Esbensen BA, Juhl C. Neurophysiological pain education for patients with chronic low back pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin J Pain. 2018;34:778–86. 10.1097/AJP.0000000000000594.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[49] Mikocka-Walus AA, Andrews JM, Bernstein CN, Graff LA, Walker JR, Spinelli A, et al. Integrated models of care in managing inflammatory bowel disease: A discussion. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:1582–7. 10.1002/ibd.22877.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Editorial Comment

- From pain to relief: Exploring the consistency of exercise-induced hypoalgesia

- Christmas greetings 2024 from the Editor-in-Chief

- Original Articles

- The Scandinavian Society for the Study of Pain 2022 Postgraduate Course and Annual Scientific (SASP 2022) Meeting 12th to 14th October at Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen

- Comparison of ultrasound-guided continuous erector spinae plane block versus continuous paravertebral block for postoperative analgesia in patients undergoing proximal femur surgeries

- Clinical Pain Researches

- The effect of tourniquet use on postoperative opioid consumption after ankle fracture surgery – a retrospective cohort study

- Changes in pain, daily occupations, lifestyle, and health following an occupational therapy lifestyle intervention: a secondary analysis from a feasibility study in patients with chronic high-impact pain

- Tonic cuff pressure pain sensitivity in chronic pain patients and its relation to self-reported physical activity

- Reliability, construct validity, and factorial structure of a Swedish version of the medical outcomes study social support survey (MOS-SSS) in patients with chronic pain

- Hurdles and potentials when implementing internet-delivered Acceptance and commitment therapy for chronic pain: a retrospective appraisal using the Quality implementation framework

- Exploring the outcome “days with bothersome pain” and its association with pain intensity, disability, and quality of life

- Fatigue and cognitive fatigability in patients with chronic pain

- The Swedish version of the pain self-efficacy questionnaire short form, PSEQ-2SV: Cultural adaptation and psychometric evaluation in a population of patients with musculoskeletal disorders

- Pain coping and catastrophizing in youth with and without cerebral palsy

- Neuropathic pain after surgery – A clinical validation study and assessment of accuracy measures of the 5-item NeuPPS scale

- Translation, contextual adaptation, and reliability of the Danish Concept of Pain Inventory (COPI-Adult (DK)) – A self-reported outcome measure

- Cosmetic surgery and associated chronic postsurgical pain: A cross-sectional study from Norway

- The association of hemodynamic parameters and clinical demographic variables with acute postoperative pain in female oncological breast surgery patients: A retrospective cohort study

- Healthcare professionals’ experiences of interdisciplinary collaboration in pain centres – A qualitative study

- Effects of deep brain stimulation and verbal suggestions on pain in Parkinson’s disease

- Painful differences between different pain scale assessments: The outcome of assessed pain is a matter of the choices of scale and statistics

- Prevalence and characteristics of fibromyalgia according to three fibromyalgia diagnostic criteria: A secondary analysis study

- Sex moderates the association between quantitative sensory testing and acute and chronic pain after total knee/hip arthroplasty

- Tramadol-paracetamol for postoperative pain after spine surgery – A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study

- Cancer-related pain experienced in daily life is difficult to communicate and to manage – for patients and for professionals

- Making sense of pain in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD): A qualitative study

- Patient-reported pain, satisfaction, adverse effects, and deviations from ambulatory surgery pain medication

- Does pain influence cognitive performance in patients with mild traumatic brain injury?

- Hypocapnia in women with fibromyalgia

- Application of ultrasound-guided thoracic paravertebral block or intercostal nerve block for acute herpes zoster and prevention of post-herpetic neuralgia: A case–control retrospective trial

- Translation and examination of construct validity of the Danish version of the Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia

- A positive scratch collapse test in anterior cutaneous nerve entrapment syndrome indicates its neuropathic character

- ADHD-pain: Characteristics of chronic pain and association with muscular dysregulation in adults with ADHD

- The relationship between changes in pain intensity and functional disability in persistent disabling low back pain during a course of cognitive functional therapy

- Intrathecal pain treatment for severe pain in patients with terminal cancer: A retrospective analysis of treatment-related complications and side effects

- Psychometric evaluation of the Danish version of the Pain Self-Efficacy Questionnaire in patients with subacute and chronic low back pain

- Dimensionality, reliability, and validity of the Finnish version of the pain catastrophizing scale in chronic low back pain

- To speak or not to speak? A secondary data analysis to further explore the context-insensitive avoidance scale

- Pain catastrophizing levels differentiate between common diseases with pain: HIV, fibromyalgia, complex regional pain syndrome, and breast cancer survivors

- Prevalence of substance use disorder diagnoses in patients with chronic pain receiving reimbursed opioids: An epidemiological study of four Norwegian health registries

- Pain perception while listening to thrash heavy metal vs relaxing music at a heavy metal festival – the CoPainHell study – a factorial randomized non-blinded crossover trial

- Observational Studies

- Cutaneous nerve biopsy in patients with symptoms of small fiber neuropathy: a retrospective study

- The incidence of post cholecystectomy pain (PCP) syndrome at 12 months following laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a prospective evaluation in 200 patients

- Associations between psychological flexibility and daily functioning in endometriosis-related pain

- Relationship between perfectionism, overactivity, pain severity, and pain interference in individuals with chronic pain: A cross-lagged panel model analysis

- Access to psychological treatment for chronic cancer-related pain in Sweden

- Validation of the Danish version of the knowledge and attitudes survey regarding pain

- Associations between cognitive test scores and pain tolerance: The Tromsø study

- Healthcare experiences of fibromyalgia patients and their associations with satisfaction and pain relief. A patient survey

- Video interpretation in a medical spine clinic: A descriptive study of a diverse population and intervention

- Role of history of traumatic life experiences in current psychosomatic manifestations

- Social determinants of health in adults with whiplash associated disorders

- Which patients with chronic low back pain respond favorably to multidisciplinary rehabilitation? A secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial

- A preliminary examination of the effects of childhood abuse and resilience on pain and physical functioning in patients with knee osteoarthritis

- Differences in risk factors for flare-ups in patients with lumbar radicular pain may depend on the definition of flare

- Real-world evidence evaluation on consumer experience and prescription journey of diclofenac gel in Sweden

- Patient characteristics in relation to opioid exposure in a chronic non-cancer pain population

- Topical Reviews

- Bridging the translational gap: adenosine as a modulator of neuropathic pain in preclinical models and humans

- What do we know about Indigenous Peoples with low back pain around the world? A topical review

- The “future” pain clinician: Competencies needed to provide psychologically informed care

- Systematic Reviews

- Pain management for persistent pain post radiotherapy in head and neck cancers: systematic review

- High-frequency, high-intensity transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation compared with opioids for pain relief after gynecological surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis

- Reliability and measurement error of exercise-induced hypoalgesia in pain-free adults and adults with musculoskeletal pain: A systematic review

- Noninvasive transcranial brain stimulation in central post-stroke pain: A systematic review

- Short Communications

- Are we missing the opioid consumption in low- and middle-income countries?

- Association between self-reported pain severity and characteristics of United States adults (age ≥50 years) who used opioids

- Could generative artificial intelligence replace fieldwork in pain research?

- Skin conductance algesimeter is unreliable during sudden perioperative temperature increases

- Original Experimental

- Confirmatory study of the usefulness of quantum molecular resonance and microdissectomy for the treatment of lumbar radiculopathy in a prospective cohort at 6 months follow-up

- Pain catastrophizing in the elderly: An experimental pain study

- Improving general practice management of patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain: Interdisciplinarity, coherence, and concerns

- Concurrent validity of dynamic bedside quantitative sensory testing paradigms in breast cancer survivors with persistent pain

- Transcranial direct current stimulation is more effective than pregabalin in controlling nociceptive and anxiety-like behaviors in a rat fibromyalgia-like model

- Paradox pain sensitivity using cuff pressure or algometer testing in patients with hemophilia

- Physical activity with person-centered guidance supported by a digital platform or with telephone follow-up for persons with chronic widespread pain: Health economic considerations along a randomized controlled trial

- Measuring pain intensity through physical interaction in an experimental model of cold-induced pain: A method comparison study

- Pharmacological treatment of pain in Swedish nursing homes: Prevalence and associations with cognitive impairment and depressive mood

- Neck and shoulder pain and inflammatory biomarkers in plasma among forklift truck operators – A case–control study

- The effect of social exclusion on pain perception and heart rate variability in healthy controls and somatoform pain patients

- Revisiting opioid toxicity: Cellular effects of six commonly used opioids

- Letter to the Editor

- Post cholecystectomy pain syndrome: Letter to Editor

- Response to the Letter by Prof Bordoni

- Response – Reliability and measurement error of exercise-induced hypoalgesia

- Is the skin conductance algesimeter index influenced by temperature?

- Skin conductance algesimeter is unreliable during sudden perioperative temperature increase

- Corrigendum

- Corrigendum to “Chronic post-thoracotomy pain after lung cancer surgery: a prospective study of preoperative risk factors”

- Obituary

- A Significant Voice in Pain Research Björn Gerdle in Memoriam (1953–2024)

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Editorial Comment

- From pain to relief: Exploring the consistency of exercise-induced hypoalgesia

- Christmas greetings 2024 from the Editor-in-Chief

- Original Articles

- The Scandinavian Society for the Study of Pain 2022 Postgraduate Course and Annual Scientific (SASP 2022) Meeting 12th to 14th October at Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen

- Comparison of ultrasound-guided continuous erector spinae plane block versus continuous paravertebral block for postoperative analgesia in patients undergoing proximal femur surgeries

- Clinical Pain Researches

- The effect of tourniquet use on postoperative opioid consumption after ankle fracture surgery – a retrospective cohort study

- Changes in pain, daily occupations, lifestyle, and health following an occupational therapy lifestyle intervention: a secondary analysis from a feasibility study in patients with chronic high-impact pain

- Tonic cuff pressure pain sensitivity in chronic pain patients and its relation to self-reported physical activity

- Reliability, construct validity, and factorial structure of a Swedish version of the medical outcomes study social support survey (MOS-SSS) in patients with chronic pain

- Hurdles and potentials when implementing internet-delivered Acceptance and commitment therapy for chronic pain: a retrospective appraisal using the Quality implementation framework

- Exploring the outcome “days with bothersome pain” and its association with pain intensity, disability, and quality of life

- Fatigue and cognitive fatigability in patients with chronic pain

- The Swedish version of the pain self-efficacy questionnaire short form, PSEQ-2SV: Cultural adaptation and psychometric evaluation in a population of patients with musculoskeletal disorders

- Pain coping and catastrophizing in youth with and without cerebral palsy

- Neuropathic pain after surgery – A clinical validation study and assessment of accuracy measures of the 5-item NeuPPS scale

- Translation, contextual adaptation, and reliability of the Danish Concept of Pain Inventory (COPI-Adult (DK)) – A self-reported outcome measure

- Cosmetic surgery and associated chronic postsurgical pain: A cross-sectional study from Norway

- The association of hemodynamic parameters and clinical demographic variables with acute postoperative pain in female oncological breast surgery patients: A retrospective cohort study

- Healthcare professionals’ experiences of interdisciplinary collaboration in pain centres – A qualitative study

- Effects of deep brain stimulation and verbal suggestions on pain in Parkinson’s disease

- Painful differences between different pain scale assessments: The outcome of assessed pain is a matter of the choices of scale and statistics

- Prevalence and characteristics of fibromyalgia according to three fibromyalgia diagnostic criteria: A secondary analysis study

- Sex moderates the association between quantitative sensory testing and acute and chronic pain after total knee/hip arthroplasty

- Tramadol-paracetamol for postoperative pain after spine surgery – A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study

- Cancer-related pain experienced in daily life is difficult to communicate and to manage – for patients and for professionals

- Making sense of pain in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD): A qualitative study

- Patient-reported pain, satisfaction, adverse effects, and deviations from ambulatory surgery pain medication

- Does pain influence cognitive performance in patients with mild traumatic brain injury?

- Hypocapnia in women with fibromyalgia

- Application of ultrasound-guided thoracic paravertebral block or intercostal nerve block for acute herpes zoster and prevention of post-herpetic neuralgia: A case–control retrospective trial

- Translation and examination of construct validity of the Danish version of the Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia

- A positive scratch collapse test in anterior cutaneous nerve entrapment syndrome indicates its neuropathic character

- ADHD-pain: Characteristics of chronic pain and association with muscular dysregulation in adults with ADHD

- The relationship between changes in pain intensity and functional disability in persistent disabling low back pain during a course of cognitive functional therapy

- Intrathecal pain treatment for severe pain in patients with terminal cancer: A retrospective analysis of treatment-related complications and side effects

- Psychometric evaluation of the Danish version of the Pain Self-Efficacy Questionnaire in patients with subacute and chronic low back pain

- Dimensionality, reliability, and validity of the Finnish version of the pain catastrophizing scale in chronic low back pain

- To speak or not to speak? A secondary data analysis to further explore the context-insensitive avoidance scale

- Pain catastrophizing levels differentiate between common diseases with pain: HIV, fibromyalgia, complex regional pain syndrome, and breast cancer survivors

- Prevalence of substance use disorder diagnoses in patients with chronic pain receiving reimbursed opioids: An epidemiological study of four Norwegian health registries

- Pain perception while listening to thrash heavy metal vs relaxing music at a heavy metal festival – the CoPainHell study – a factorial randomized non-blinded crossover trial

- Observational Studies

- Cutaneous nerve biopsy in patients with symptoms of small fiber neuropathy: a retrospective study

- The incidence of post cholecystectomy pain (PCP) syndrome at 12 months following laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a prospective evaluation in 200 patients

- Associations between psychological flexibility and daily functioning in endometriosis-related pain

- Relationship between perfectionism, overactivity, pain severity, and pain interference in individuals with chronic pain: A cross-lagged panel model analysis

- Access to psychological treatment for chronic cancer-related pain in Sweden

- Validation of the Danish version of the knowledge and attitudes survey regarding pain

- Associations between cognitive test scores and pain tolerance: The Tromsø study

- Healthcare experiences of fibromyalgia patients and their associations with satisfaction and pain relief. A patient survey

- Video interpretation in a medical spine clinic: A descriptive study of a diverse population and intervention

- Role of history of traumatic life experiences in current psychosomatic manifestations

- Social determinants of health in adults with whiplash associated disorders

- Which patients with chronic low back pain respond favorably to multidisciplinary rehabilitation? A secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial

- A preliminary examination of the effects of childhood abuse and resilience on pain and physical functioning in patients with knee osteoarthritis

- Differences in risk factors for flare-ups in patients with lumbar radicular pain may depend on the definition of flare

- Real-world evidence evaluation on consumer experience and prescription journey of diclofenac gel in Sweden

- Patient characteristics in relation to opioid exposure in a chronic non-cancer pain population

- Topical Reviews

- Bridging the translational gap: adenosine as a modulator of neuropathic pain in preclinical models and humans

- What do we know about Indigenous Peoples with low back pain around the world? A topical review

- The “future” pain clinician: Competencies needed to provide psychologically informed care

- Systematic Reviews

- Pain management for persistent pain post radiotherapy in head and neck cancers: systematic review

- High-frequency, high-intensity transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation compared with opioids for pain relief after gynecological surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis

- Reliability and measurement error of exercise-induced hypoalgesia in pain-free adults and adults with musculoskeletal pain: A systematic review

- Noninvasive transcranial brain stimulation in central post-stroke pain: A systematic review

- Short Communications

- Are we missing the opioid consumption in low- and middle-income countries?

- Association between self-reported pain severity and characteristics of United States adults (age ≥50 years) who used opioids

- Could generative artificial intelligence replace fieldwork in pain research?

- Skin conductance algesimeter is unreliable during sudden perioperative temperature increases

- Original Experimental

- Confirmatory study of the usefulness of quantum molecular resonance and microdissectomy for the treatment of lumbar radiculopathy in a prospective cohort at 6 months follow-up

- Pain catastrophizing in the elderly: An experimental pain study

- Improving general practice management of patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain: Interdisciplinarity, coherence, and concerns

- Concurrent validity of dynamic bedside quantitative sensory testing paradigms in breast cancer survivors with persistent pain

- Transcranial direct current stimulation is more effective than pregabalin in controlling nociceptive and anxiety-like behaviors in a rat fibromyalgia-like model

- Paradox pain sensitivity using cuff pressure or algometer testing in patients with hemophilia

- Physical activity with person-centered guidance supported by a digital platform or with telephone follow-up for persons with chronic widespread pain: Health economic considerations along a randomized controlled trial

- Measuring pain intensity through physical interaction in an experimental model of cold-induced pain: A method comparison study

- Pharmacological treatment of pain in Swedish nursing homes: Prevalence and associations with cognitive impairment and depressive mood

- Neck and shoulder pain and inflammatory biomarkers in plasma among forklift truck operators – A case–control study

- The effect of social exclusion on pain perception and heart rate variability in healthy controls and somatoform pain patients

- Revisiting opioid toxicity: Cellular effects of six commonly used opioids

- Letter to the Editor

- Post cholecystectomy pain syndrome: Letter to Editor

- Response to the Letter by Prof Bordoni

- Response – Reliability and measurement error of exercise-induced hypoalgesia

- Is the skin conductance algesimeter index influenced by temperature?

- Skin conductance algesimeter is unreliable during sudden perioperative temperature increase

- Corrigendum

- Corrigendum to “Chronic post-thoracotomy pain after lung cancer surgery: a prospective study of preoperative risk factors”

- Obituary

- A Significant Voice in Pain Research Björn Gerdle in Memoriam (1953–2024)