Healthcare experiences of fibromyalgia patients and their associations with satisfaction and pain relief. A patient survey

-

Sigrid Hørven Wigers

, Marit B. Veierød

Abstract

Objectives

The etiology of fibromyalgia (FM) is disputed, and there is no established cure. Quantitative data on how this may affect patients’ healthcare experiences are scarce. The present study aims to investigate FM patients’ pain-related healthcare experiences and explore factors associated with high satisfaction and pain relief.

Methods

An anonymous, online, and patient-administered survey was developed and distributed to members of the Norwegian Fibromyalgia Association. It addressed their pain-related healthcare experiences from both primary and specialist care. Odds ratios for healthcare satisfaction and pain relief were estimated by binary logistic regression. Directed acyclic graphs guided the multivariable analyses.

Results

The patients (n = 1,626, mean age: 51 years) were primarily women (95%) with a 21.8-year mean pain duration and 12.7 years in pain before diagnosis. One-third did not understand why they had pain, and 56.6% did not know how to get better. More than half had not received satisfactory information on their pain cause from a physician, and guidance on how to improve was reported below medium. Patients regretted a lack of medical specialized competence on muscle pain and reported many unmet needs, including regular follow-up and pain assessment. Physician-mediated pain relief was low, and guideline adherence was deficient. Only 14.8% were satisfied with non-physician health providers evaluating and treating their pain, and 21.5% were satisfied (46.9% dissatisfied) with their global pain-related healthcare. Patients’ knowledge of their condition, physicians’ pain competence and provision of information and guidance, agreement in explanations and advice, and the absence of unmet needs significantly increased the odds of both healthcare satisfaction and pain relief.

Conclusions

Our survey describes deficiencies in FM patients’ pain-related healthcare and suggests areas for improvement to increase healthcare satisfaction and pain relief. (REC# 2019/845, 09.05.19).

1 Introduction

Chronic musculoskeletal pain is the primary cause of years lived with disability and reduced quality of life [1]. Around 10% of the world’s population suffers from chronic widespread pain, with fibromyalgia (FM) as the most common diagnosis [2–4]. The etiology of FM is disputed; its underlying pain mechanisms are insufficiently uncovered, and there is presently no established cure. FM also implies other accompanying symptoms like fatigue, disturbed sleep, cognitive disturbances, and emotional distress [5,6]. The patients’ burden of illness and disability is profound, their healthcare use is extensive, and societal costs are substantial [7,8].

FM does not impose pathological findings on conventional medical investigations, and the diagnosis rests on a diagnostic questionnaire [6]. Many physicians are unfamiliar with the diagnostics and handling of FM [9,10]. They tend to place FM at the bottom of the hierarchy of diseases [11], and many find dealing with FM patients challenging [10–13]. Given its high prevalence and impact, chronic pain has little focus in their medical education [14–16], and neither has muscle pain, which often initiates and perpetuates FM [17–20]. No medical specialty has been assigned or has adopted the main responsibility for muscle pain competence and research. “Invisible” pain tends to evoke less patient-centeredness and empathic behavior than pain with an obvious cause [21].

There are scarce quantitative data on how this may affect FM patients’ healthcare experiences. Doebl et al. found fewer positive healthcare experiences among diagnosed FM patients compared to other chronic pain patients [22]. Their previous review, comprising mostly of qualitative studies, concludes that FM healthcare is inconsistent and poorly coordinated, with difficult encounters, patients experiencing not being believed or listened to, and diagnostic delays [23]. Patients struggle to receive proper examination, information, and follow-up [24]. This discords with the international guidelines for FM management, which stress the importance of prompt diagnostics, sufficient patient information, thorough pain assessment, and regular follow-up [25–27].

In Norway, FM patients are assigned to primary healthcare and often treated by other health providers (OHPs) without physician-based education [28]. There are no national guidelines. To supply present knowledge quantitatively, our survey aims to assess how Norwegian FM patients experience their pain-related healthcare in both primary and specialist settings. It focuses on perceived physician competence, information, guidance, unmet needs, outcomes, and satisfaction. To indicate areas for future improvement, we also explored factors associated with high patient satisfaction and pain relief.

2 Methods

2.1 Setting

The present survey was developed and performed in 2018–2019. It represents the patient part of the MyShips project, a project that includes separate but comparable surveys among patients and physicians on how they experience FM and chronic myofascial pain healthcare.

2.2 Questionnaire development

A survey questionnaire was created as we found no existing validated questionnaires covering our aim. It was developed by an expert group comprising specialists in physical medicine and rehabilitation (SHW), general practice, public health, rheumatology, and an FM-patient representative. They aspired to develop a short, anonymous, patient-administered questionnaire that was precise and easy for patients to understand. After several revisions in the group, a 25-item questionnaire was converted to an electronic format using SurveyMonkey® software (Copyright © 1999–2021 SurveyMonkey). Thereafter, it was tested by patient representatives from the Norwegian Fibromyalgia Association (NFA) staff. Each test subject was asked to report on clearness, relevance, and user-friendliness and offer suggestions for improvement. This was done to assess face validity and completion time and to avoid unrecognized flaws.

2.3 Questionnaire content

The questionnaire had no person-identifiable questions. It covered the following. 1) Survey information and consent to participation. 2) Characteristics of the participants, which also included diagnostic time (years in pain before diagnosis), patients’ lack of knowledge on their pain cause and how to get better, and healthcare professionals consulted. 3) Perceived physician pain competence. 4) Information quality and sources. 5) Unmet needs. 6) Physician-mediated pain relief. 7) Satisfaction with OHP services. 8) Patients’ global satisfaction (PGS) with their overall received pain-related healthcare. Response categories were exact numbers, yes/no, multiple choice, 5-point Likert scales with verbal descriptors tailored to each question (1 = very little, 5 = very great), or open-ended comments with textual responses. An English translation of the questionnaire is given in Appendix S1.

2.4 Questionnaire distribution

In June 2019, the NFA distributed the survey by e-mail to 4,926 patient members and published identical survey information in the July issue of their membership journal. Respondents completed and submitted the survey electronically through SurveyMonkey® software, which automatically deleted the respondents’ IP addresses to ensure respondent anonymity before forwarding responses to the project leader (SHW).

3 Statistical analyses

Descriptive results are presented as frequencies (%) and mean values (with range and standard deviations, SDs). Open-ended comments were categorized and/or counted and presented as frequencies. The chi-square test was used to compare patients’ experiences with general practitioners (GPs) and medical specialists (MSs). Odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated by binary logistic regression for the associations between characteristics of the participants and PGS or physician-mediated pain relief, for associations between information sources and patients’ lack of knowledge, and for associations between healthcare experiences and PGS or physician-mediated pain relief. As we were interested in estimating factors associated with great satisfaction or pain relief, dependent variables were either PGS dichotomized as “satisfied/very satisfied” versus “very dissatisfied/dissatisfied/neither-nor,” or physician-mediated pain relief dichotomized as “great/very great” versus “very little/little/medium.” Directed acyclic graphs guided the multivariable analyses. All tests were two-sided with a 5% significance level, using IBM SPSS version 27.

4 Results

We received 1,629 responses (33%). Three respondents were excluded from the analyses. They had not marked whether or not they consented to participate and only answered a few questions. The survey thus included 1,626 patients. Missing responses were ≤6% for each question.

4.1 Characteristics of the participants

Patients were mainly middle-aged women with widespread pain. The mean pain duration was 21.8 years, and the mean diagnostic time was 12.7 years (Table 1). One in three did not understand why they had pain, and more than half did not know how to get better. Nearly all had consulted GPs and OHPs for their pain problems, and the majority had also encountered MSs. Open-ended comments revealed that the patients had consulted physicians of 12 different medical specialties and OHPs with 39 different professional backgrounds, including alternative medicine practitioners.

Characteristics of the survey participants, n = 1,626

| Patient characteristics | All patients |

|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (range, SD) | 51.4 (13–85, 10.9) |

| Gender (women) | 1528 (94.9)a |

| Pain duration (years), mean (range, SD) | 21.8 (1–70, 11.6) |

| Pain localization (widespreadb) | 1532 (94.5) |

| Diagnostic timec (years), mean (range, SD) | 12.7 (1–55, 9.4) |

| Lack of knowledge (marked) | |

| I do not understand why I am in pain | 550 (33.9) |

| I do not know what I can do to get better | 917 (56.6) |

| Consulted because of pain (yes) | |

| GP | 1587 (98.1) |

| MS | 1247 (78.9) |

| OHPs | 1421 (92.7) |

Values are n (%) for all categorical variables. a16 patients did not report their gender, and 82 patients (5.1%) were men. bPain in the whole or large part of the body. cYears in pain before a diagnosis. GP = general practitioner, MS = medical specialist, OHPs = other health providers. Missing was ≤2.8%, except for OHPs (5.7% missing).

4.2 Patients’ pain-related healthcare experiences

A general tendency of discontentment was shown, as 9 of 11 Likert scales had mean scores below 3 (medium) (Table 2). Patients perceived GPs’ pain competence to be lower than MSs’ (GP: 25.9% vs MS: 48.8% “great/very great,” p < 0.001), and 35.5% reported GPs to have “very little/little” ability to meet their pain-related needs. Many stated deficient physician-provided information on their pain cause (GP: 63.8% vs MS: 51.6%, p < 0.001) and insufficient guidance on what they could do themselves to get better (GP: 47.3% vs MS: 37.8% “very little/little,” p < 0.001). Around 20% reported having received satisfactory information on the pain cause and how to get better from physicians, 56.3% from OHPs (39% from OHPs alone), and 26.6% had not received this from anyone. The agreement in explanations and advice from different health providers was around medium, with 28.7% stating a “high/very high” agreement. Patients reported several unmet needs from their GPs, the most prevalent being “regular follow-up and support,” “comprehensible pain explanation and guidance,” “clinical examination and pain assessment,” and “referral to a MS.” The most frequent open-ended specifications were “to be believed, taken seriously and met with understanding and empathy” and “more knowledge about FM among physicians” (Table S1 shows a complete list, Supplementary Material). Nearly all found the lack of established medical-specialized competence on muscle pain “very unfortunate/unfortunate.” Physician-mediated pain relief was low and lowest for MSs (GP: 54.2% vs MS: 70.2% “very little/little,” p < 0.001), and 47.8% were “very dissatisfied/dissatisfied” with OHPs often being the ones to evaluate and treat their pain (14.8% were “satisfied/very satisfied”). PGS, with their overall received pain-related healthcare, showed that 21.5% were “satisfied/very satisfied” and 46.9% were “very dissatisfied/dissatisfied.”

Patients’ pain-related healthcare experiences, n = 1,626

| Questions | n (%) | Very little | Little | Medium | Great | Very great | Mean |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 n (%) | 2 n (%) | 3 n (%) | 4 n (%) | 5 n (%) | |||

| Perceived physician pain competence | |||||||

| To what extent are your pain-related needs covered by the GP? | 203 (13.0) | 350 (22.5) | 598 (38.4) | 329 (21.2) | 78 (4.8) | 2.83 | |

| How great competence do you perceive the GP has on your pain? | 165 (10.7) | 328 (21.2) | 654 (42.2) | 329 (21.2) | 73 (4.7) | 2.88 | |

| How great competence do you perceive MSs you have consulted have on your pain? | 63 (5.1) | 138 (11.2) | 430 (34.9) | 422 (34.3) | 178 (14.5) | 3.42 | |

| Information quality and sources | |||||||

| Has the GP given you satisfactory (comprehensible and meaningful) information on the pain cause? (yes/no) | 558/985 (36.2/63.8) | ||||||

| Have MS/s given you satisfactory (comprehensible and meaningful) information on the pain cause? (yes/no) | 593/632 (48.4/51.6) | ||||||

| Has the GP given you specific and efficient guidance on what you can do yourself to get better? | 222 (14.3) | 512 (33.0) | 569 (36.7) | 214 (13.8) | 35 (2.3) | 2.57 | |

| Have MS/s given you specific and efficient guidance on what you can do yourself to get better? | 134 (10.9) | 330 (26.9) | 487 (39.7) | 228 (18.6) | 48 (3.9) | 2.78 | |

| Who have given you satisfactory guidance on the pain cause and what you can do yourself to get better? (several markings allowed) | |||||||

| GP | 342 (22.2) | ||||||

| MS | 325 (20.9) | ||||||

| OHP | 806 (56.3) | ||||||

| Nobody | 413 (26.6) | ||||||

| Do the explanations and advice different professionals have given you agree? | 128 (8.4%)a | 61 (4.0) | 261 (17.1) | 635 (41.7) | 342 (22.5) | 95 (6.2) | 3.11b |

| Unmet needs c | |||||||

| Are there any of the following services you miss having covered by your GP? (several markings allowed) | |||||||

| – Regular follow-up and support | 725 (46.5) | ||||||

| – Good and comprehensible pain explanation and guidance on what you can do yourself to get better | 693 (44.4) | ||||||

| – Clinical examination and pain assessment | 543 (34.8) | ||||||

| – Further referral to an MS | 535 (34.3) | ||||||

| How do you regard that no medical specialty has established specialized competence in muscle pain?d | 850 (70.6) | 292 (24.3) | 47 (3.9) | 11 (0.9) | 4 (0.3) | 1.36 | |

| Physician-mediated pain relief | |||||||

| To what extent has the GP service contributed to your pain relief? | 316 (20.5) | 520 (33.7) | 525 (34.0) | 163 (10.6) | 19 (1.2) | 2.38 | |

| To what extent has the MS service contributed to your pain relief? | 401 (32.8) | 458 (37.4) | 279 (22.8) | 73 (6.0) | 12 (1.0) | 2.05 | |

| Satisfaction with OHP services | |||||||

| How satisfied are you with OHPs without a physician-based medical education to often be the ones who evaluate and treat your pain?e | 273 (18.1) | 447 (29.7) | 565 (37.5) | 191 (12.7) | 31 (2.1) | 2.51 | |

| PGS | |||||||

| All in all, how satisfied are you with the healthcare system’s handling your pain problems?ef | 203 (13.3) | 512 (33.6) | 483 (31.7) | 301 (19.7) | 27 (1.8) | 2.63 |

GP = general practitioner, MS = medical specialist, OHP = other health provider. aNot received any explanation. bFor those who have received an explanation. cThe four most frequently mentioned. For a complete list, see Table S1. dLikert scale categories 1–5 are “very unfortunate/unfortunate/neither nor/good/very good.” eLikert scale categories 1–5 are “very dissatisfied/dissatisfied/neither nor/satisfied/very satisfied.” fThe “health care system” includes both primary, specialist, and OHP services seen as a whole. Missing was ≤6%.

4.3 Associations between characteristics of the participants and PGS and physician-mediated pain relief

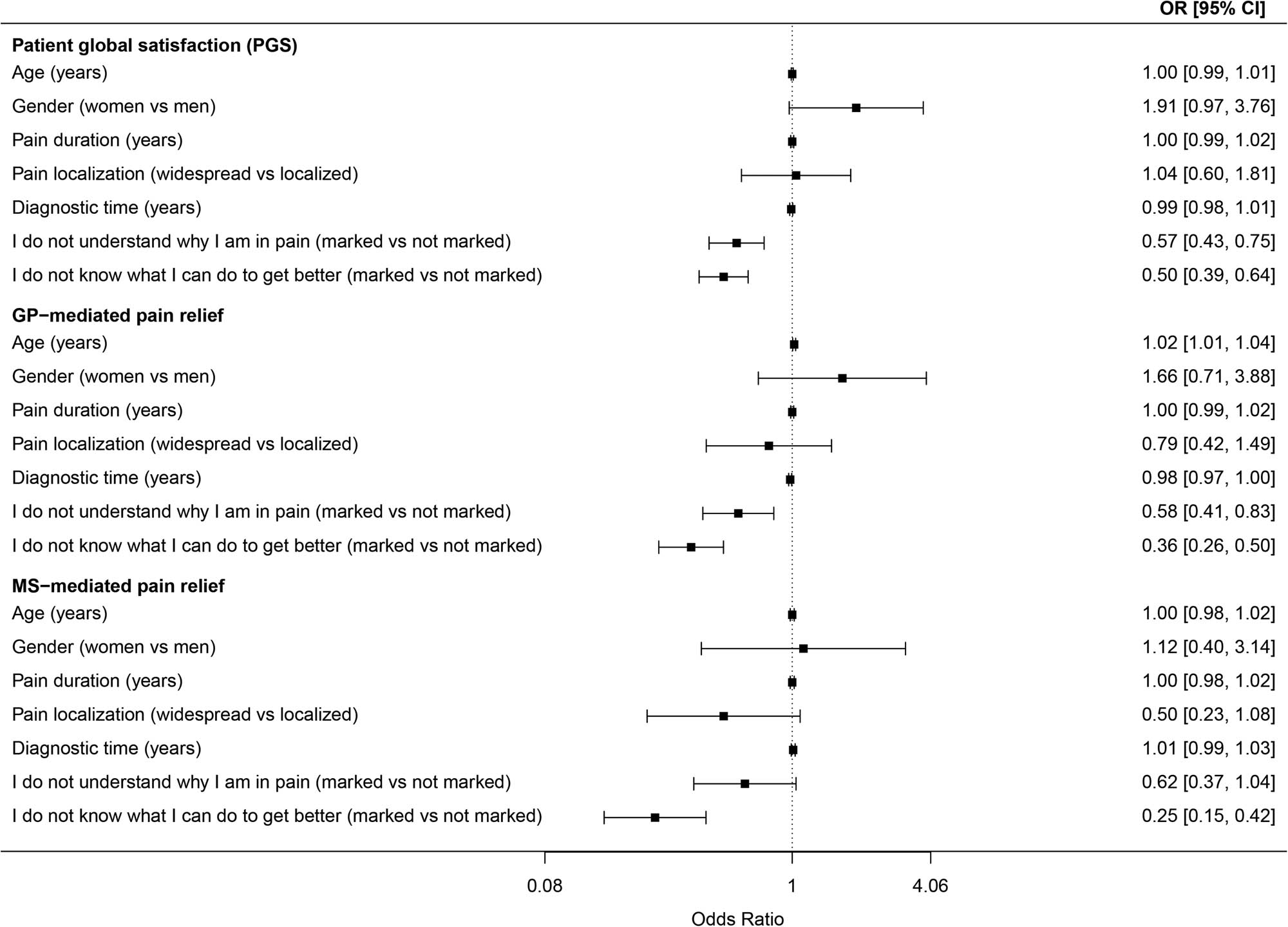

Age, gender, pain duration, pain localization, and diagnostic time were not significantly associated with PGS or physician-mediated pain relief (Figure 1). However, not understanding why they had pain significantly reduced patients’ odds of both PGS and GP-mediated pain relief. Not knowing what they could do to get better significantly reduced the odds of both PGS and physician-mediated pain relief.

Associations between characteristics of the participants and PGS and physician-mediated pain relief. OR = odds ratio, CI = confidence interval, vs = versus, GP = general practitioner, MS = medical specialist. Binary logistic regression, all analyses are age- and gender-adjusted. Dependent variable PGS is dichotomized “satisfied/very satisfied” vs “very dissatisfied/dissatisfied/neither nor.” Dependent variables GP- and MS-mediated pain relief are dichotomized “great/very great” vs “very little/little/medium.”

4.4 Associations between patients’ lack of knowledge and information quality and sources

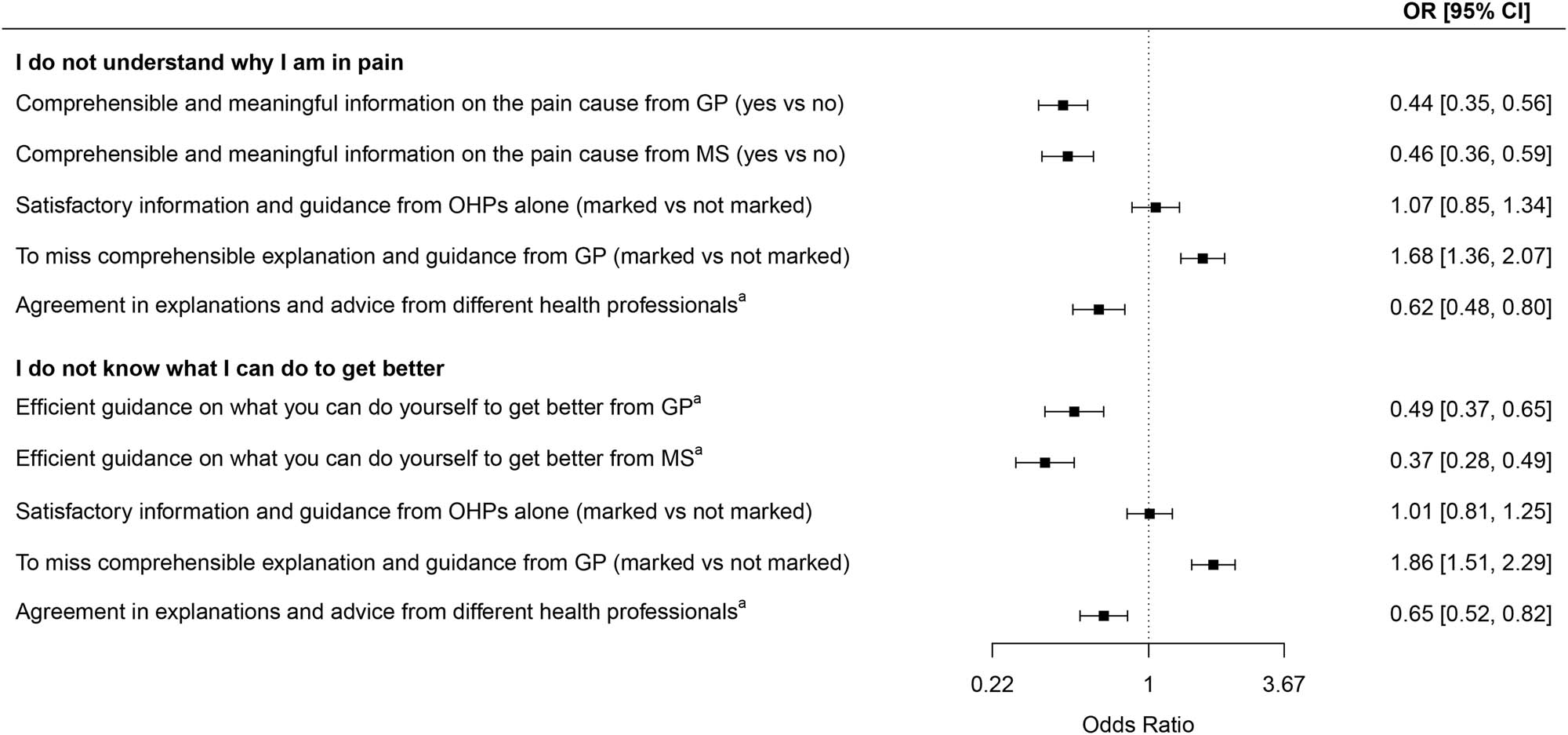

Patients’ lack of understanding of why they had pain, and knowledge of what they could do to get better were significantly and negatively associated with physician-provided information and guidance on these matters as well as with the extent of agreement in explanations and advice from different professionals (Figure 2).

Associations between patients’ lack of knowledge and information quality and sources. OR = odds ratio, CI = confidence interval, vs = versus, GP = general practitioner, MS = medical specialist. Dependent variables (marked vs not marked) are “I do not understand why I am in pain” and “I do not know what I can do to get better.” Binary logistic regression, all analyses are age- and gender-adjusted. aLikert scale dichotomized as “great/very great” vs “very little/little/medium.”

4.5 Associations between healthcare experiences and PGS

Factors significantly and positively associated with PGS were perceived physician pain competence, physician-provided information and guidance, agreement in explanations and advice, physician-mediated pain relief, and satisfaction with OHP services (Table 3). However, receiving satisfactory information and guidance from OHPs alone and having needs not being met by their GP significantly reduced the odds of PGS.

Associations between healthcare experiences and PGS, n = 1,626

| Variable no. | Explanatory variables | OR (95% CI) Age- and gender-adjusted | OR (95% CI) Multivariable |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived physician pain competence | |||

| 1 | Perceived GP competence on your paina | 7.8 (6.0–10.3) | 2.1 (1.4–3.1)b |

| 2 | Perceived MS competence on your paina | 4.3 (3.1–5.8) | 2.0 (1.4–2.9)c |

| Information quality and sources | |||

| 3 | Comprehensible and meaningful information from GP on the pain cause (yes/no) | 7.6 (5.7–10.0) | 6.3 (4.8–8.4)d |

| 4 | Comprehensible and meaningful information from MS on the pain cause (yes/no) | 5.2 (3.8–7.1) | |

| 5 | Efficient guidance from GP on what you can do yourself to get better | 9.4 (6.9–12.8) | 2.9 (2.0–4.2)e |

| 6 | Efficient guidance from MS on what you can do yourself to get better | 5.6 (4.2–7.6) | 2.5 (1.8–3.6)f |

| 7 | Satisfactory information and guidance from OHPs alone (n = 558) (marked vs not marked) | 0.6 (0.5–0.8) | 0.6 (0.4–0.8)g |

| 8 | Agreement in explanations and advicea | 5.5 (4.2–7.2) | |

| Unmet needs from GP (marked vs not marked) | |||

| 9 | To miss regular follow-up and support | 0.4 (0.3–0.5) | |

| 10 | To miss good and comprehensible pain explanation and guidance | 0.4 (0.3–0.5) | |

| 11 | To miss clinical examination and pain assessment | 0.3 (0.2–0.4) | |

| 12 | To miss further referral to a MS | 0.3 (0.2–0.4) | |

| Physician-mediated pain relief | |||

| 13 | GP’s contribution to your pain reliefa | 9.0 (6.4–12.7) | 3.8 (2.5–5.7)h |

| 14 | MS’s contribution to your pain reliefa | 6.1 (3.8–9.6) | 2.1 (1.2–3.5)i |

| Satisfaction with OHP services | |||

| 15 | Satisfaction with OHPs to evaluate and treat your pain j | 4.8 (3.5–6.5) | 4.3 (3.0–6.1)k |

OR = odds ratio, CI = confidence interval, vs = versus. Binary logistic regression with dependent variable PGS dichotomized as “satisfied/very satisfied” vs “very dissatisfied/dissatisfied/neither nor. GP = general practitioner, MS = medical specialist, OHP = other health provider, vs = versus. aLikert scales dichotomized as “great/very great” vs “very little/little/medium.” bAdjusted for age, gender, and variables 3, 5, 11, and 13. cAdjusted for age, gender, and variables 4, 6, and 14. dAdjusted for age, gender, and variable 11. eAdjusted for age, gender, and variables 3, 9, 11, and 13. fAdjusted for age, gender, and variables 4 and 14. gAdjusted for age, gender, and 8. hAdjusted for age, gender, and variables 3, 5, and 9. iAdjusted for age, gender, and variables 4 and 6. jThe Likert scale middle value is “neither-nor.” kAdjusted for age, gender, and variables 7 and 8.

4.6 Associations between healthcare experiences and physician-mediated pain relief

The odds of GP-mediated pain relief were significantly increased by GPs covering the patients’ pain-related needs, GP’s competence and provision of information and guidance, and agreement in explanations and advice (Table 4). Unmet needs failed to be covered by their GP, like regular follow-up and support, and clinical examination and pain assessment, significantly reduced the odds of GP-mediated pain relief. Perceived MS competence (not significant in the multivariable analysis), MS-provided information and guidance, and agreement in explanations and advice significantly increased the odds of MS-mediated pain relief.

Associations between healthcare experiences and physician-mediated pain relief, n = 1,626

| Variable no. | Explanatory variables | OR (95% CI) Age- and gender-adjusted | OR (95% CI) Multivariable |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived GP pain competence a | |||

| 1 | The extent of having your pain-related needs covered by the GPb | 15.5 (10.6–22.7) | 6.5 (4.1–10.2)c |

| 2 | Perceived GP pain competenceb | 12.1 (8.4–17.4) | 4.5 (2.8–7.2)d |

| Information quality a | |||

| 3 | Comprehensible and meaningful information from GP on the pain cause (yes vs no) | 7.2 (5.0–10.3) | 5.9 (4.1–8.6)e |

| 4 | Efficient guidance from GP on what you can do yourself to get better | 11.5 (8.1–16.3) | 5.7 (3.8–8.5)f |

| 5 | The extent of agreement in explanations and adviceb | 4.0 (2.8–5.6) | |

| Unmet needs from GP (marked vs not marked)a | |||

| 6 | To miss regular follow-up and support | 0.4 (0.3–0.6) | |

| 7 | To miss good and understandable explanation and guidance | 0.3 (0.2–0.4) | |

| 8 | To miss clinical examination and pain assessment | 0.2 (0.2–0.4) | |

| 9 | To miss further referral to a MS | 0.2 (0.2–0.4) | |

| Perceived MS pain competence g | |||

| 10 | Perceived MS pain competenceb | 9.1 (4.7–17.8) | 2.1 (0.9–4.8)h |

| Information quality g | |||

| 11 | Comprehensible and meaningful information from MS on the pain cause (yes vs no) | 13.3 (6.1–29.2) | |

| 12 | Efficient guidance from MS on what you can do yourself to get better | 23.3 (12.8–42.2) | 14.8 (7.5–29.4)i |

| 5 | The extent of agreement in explanations and adviceb | 4.0 (2.6–6.4) |

OR = odds ratio, CI = confidence interval. GP = general practitioner, MS = medical specialist, OHPs = other health providers, vs = versus. Binary logistic regression. aDependent variable: GP-mediated pain relief dichotomized as “great/very great” vs “very little/little/medium.” bExplanatory variable dichotomized as “great/very great” vs “very little/little/medium.” cAdjusted for age, gender, and variables 3, 4, 6, 8, and 9. dAdjusted for age, gender, and variables 3, 4, and 8. eAdjusted for age, gender, and variable 8. fAdjusted for age, gender, and variables 3, 6, and 8. gDependent variable: MS-mediated pain relief dichotomized as “great/very great” vs “very little/little/medium.” hAdjusted for age, gender, and variables 11 and 12. iAdjusted for age, gender, and variable 11.

5 Discussion

The survey participants reported long diagnostic times and insufficient information on and understanding of, their condition. They were generally discontent with their pain-related healthcare. However, some expressed high healthcare satisfaction and great physician-mediated pain relief. Factors significantly associated with satisfaction and pain relief were patients’ knowledge of their condition, physicians’ pain competence, provision of comprehensible information on the pain cause, efficient guidance on how to get better, agreement in explanations, and having their needs met.

Due to the complexity of FM, the diagnostic process is often time-consuming, involving several physicians [20,22,23,29,30]. Our patients’ average diagnostic time of 12.7 years was considerably longer than the 2.3, 3, and 6.4 years reported elsewhere [22,29,31]. These variations may have many causes, among others, differing bases for calculating diagnostic time. Other studies have conveyed a mean of 10 and 14.2 years in widespread pain before being diagnosed [32,33] and considerably higher healthcare use among FM patients at least 10 years prior to diagnosis [34]. A prolonged diagnostic time might increase patients’ insecurity, hypervigilance, healthcare-seeking, and pain. Having chronic pain patients wait more than 6 months for treatment is considered medically unacceptable, as it reduces their health-related quality of life and psychological well-being significantly [35]. International guidelines for FM management stress the importance of a prompt diagnosis [25]. FM patients’ healthcare use may decrease the first 2–3 years after diagnosis and promote a 4-year post-diagnostic reduction in healthcare costs [34,36]. The diagnosis seems to have a positive but temporarily limited effect, as FM patients’ initial satisfaction with being diagnosed often diminishes when they realize it neither removes their uncertainty nor implies curative treatment [20,30]. This may explain why diagnostic time did not influence our survey patients’ satisfaction and pain relief so many years after their diagnosis.

Our patients’ healthcare experiences are in agreement with the results of previous studies and suggest a substantial need for FM healthcare improvement [20,22–24,30,32,37]. The PACFiND national surveys found the UK’s greatest unmet FM healthcare need to be the lack of available services [37]. Furthermore, a proposed care pathway was insufficiently followed [22]. Quantifying the healthcare experiences of chronic pain patients with and without an FM diagnosis, they showed that FM-diagnosed patients reported the poorest experiences [22]. Compared to our patients, UK FM patients seemed to be somewhat more satisfied, especially regarding information and outcomes. The negative effects on PGS and pain relief from patients’ lack of knowledge of their condition and from insufficient provision of information and guidance give reason for concern. The importance of agreement in health professional explanations should also be noted. Patients’ coping abilities and sense of control depend on them understanding their pain and how to improve. If not, they will remain insecure and distressed, which may influence central pain modulation mechanisms to perpetuate and augment their pain [38]. The currently incomplete scientific knowledge and dissidence in the understanding of FM-pain mechanisms disable health professionals in this respect. It also increases the risk of starting patients on a course of empirical therapies that usually ends in a series of hopefulness, followed by disappointments and hopelessness [39]. Considering the high prevalence and impact of chronic musculoskeletal pain, one may wonder why no medical specialty has adopted muscle pain, as a biomedical part of the biopsychosocial paradigm, into their area of competence to systematically explore this field further [40]. With unresolved FM etiology, diverging explanations will persist, and patients continue to suffer.

MSs’ pain competence got the questionnaire’s highest mean score of 3.42. From specialists in the field, one could expect a higher score than just above medium and a pain-reducing ability greater than 2.05. Plausible reasons may be the insufficient knowledge of FM pain mechanisms and the role of MSs in handling FM patients in Norway. Our MSs mainly rule out underlying diseases and participate in the diagnostic process, while GPs follow patients over time and stand responsible for their care. It is, therefore, natural that patients report GP-mediated pain relief as greater than MSs’ albeit GPs pain-relieving ability was also low.

Receiving satisfactory information from OHPs alone diminished the PGS odds. This may indicate that patients prefer physician expertise. Their disappointment with the lack of specialized medical muscle pain competence and the fact that only 14.8% were satisfied with OHP care support this notion. However, those being satisfied with OHP services had increased PGS odds.

Our findings may be condensed to three important areas for patient satisfaction and pain relief: physicians knowledgeable of FM, satisfactory, agreeing information and guidance, and follow-up and support. This concurs with existing FM management guidelines. They stress the importance of thorough pain assessment, prompt diagnostics, sufficient information, and mainly non-pharmacological treatments tailored to each patient’s needs and responses through regular follow-up [25–27]. For many of our patients, these recommendations were not met. Poor guideline adherence has been reported in 70% of diagnosed FM patients [27]. Physicians’ and OHPs’ restricted time schedules, unfamiliarity with international guidelines, and limited access to non-pharmacological treatments are suggested reasons [27,41]. Our findings support the guideline recommendations by demonstrating that physician competence and provision of comprehensible and agreeing information greatly increased patients’ odds of PGS and pain relief while missing pain assessment and follow-up significantly reduced the odds.

5.1 Strength and limitations

Our study provides important quantitative information on FM patients’ healthcare experiences and factors associated with satisfaction and pain relief, indicating areas for FM healthcare improvement. To optimize our questionnaire's validity, Likert scale verbal descriptors were tailored to each question. An expert group ensured content validity, and preliminary testing confirmed face validity.

However, being an anonymous, patient-administered survey, our assumption that respondents had FM rests solely upon their reporting of being diagnosed, 95% having chronic widespread pain, and their NFA membership. Concerning content validity, our main focus was on physician-based services. Other important elements that might have influenced our findings could unintentionally have been left out. Furthermore, our study sample may not be fully representative due to patients’ NFA membership and a 33% response. This may limit the generalizability of our findings. Knowledge of how FM patient organization members may differ from non-members is scarce. Members are generally held to be more illness- and symptom-focused, representing a negative bias, but the only study we found on the topic contradicted this notion [33]. There, members reported less distress and greater usage of active self-management strategies, which were attributed to the support and education from their organization. It is difficult to say to what extent and in which direction NFA membership has biased our findings. However, their agreement with previous studies supports the validity of our results.

6 Conclusions

Many FM patients described negative healthcare experiences. Understanding their own condition was significantly associated with both patients’ healthcare satisfaction and pain relief, as was physician competence, provision of meaningful and non-conflicting information and guidance, pain assessment, and regular follow-up. Our findings indicate essential areas for FM healthcare improvement and suggest a need for further research on FM-pain mechanisms to increase professional knowledge and consensus.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Tove Morstad, Anne Kristine Nitter, Stein Jarle Pedersen, and Sella Aarrestad Provan for participating in the expert group designing the survey questionnaire, the Norwegian Fibromyalgia Association for distributing the survey to their members, Ibrahimu Mbdala for statistical advice and assistance with creating the forest plots, and Hein Stigum for advice concerning DAGs.

-

Research ethics: The present study is in accordance with the tenets of the Helsinki Declaration (as amended in 2013), and its protocol and survey questionnaires are reviewed by the Regional Ethical Committee of South-Eastern Norway (REC# 2019/845, 09.05.19), which found no necessity for further application for ethical approval.

-

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individuals included in this study.

-

Author contributions: SHW planned and designed the MyShips project, drafted the protocol, participated in the expert group designing the survey questionnaire, received, analyzed, and interpreted the patient data, and drafted the manuscript. MBV supervised the statistical analyses, contributed to data interpretation, and critically revised the manuscript. AMM, KØF, MPD, NGJ, and BN contributed to data interpretation and critically revised the manuscript. All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Competing interests: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: The Research Council of the Norwegian Fibromyalgia Association provided partial funding for the MyShips project.

-

Data availability: The raw data can be obtained on request from the corresponding author.

-

Supplementary Material: This article contains supplementary material (followed by the link to the article online).

Appendix S1 Handling of muscle pain and fibromyalgia in the primary- and specialist healthcare

S1.1 Welcome to a survey on the healthcare system’s handling of your pain

Thank you for participating in our survey. Your feedback matters!

The survey seeks to map patients’ and physicians’ experience with the healthcare system’s handling of chronic muscle- and soft tissue pain (for example, pain in the neck, shoulder, back, hips, arms or legs, and fibromyalgia). It comprises 25 questions and takes 5–10 min to complete.

The survey is anonymous, it contains no person-identifiable questions, and the IP address of your response is automatically deleted as soon as the answer is delivered. It will, therefore, not be possible for us to track the response back to you. (The IP address will be in The SurveyMonkey server for 13 months before it is deleted for good.) Your contribution will represent one of many patient responses, and it is the joint results that will be published.

The aim of the study is to focus on patients’ and physicians’ experiences and needs and to take the initiative to improvement if unfortunate conditions should be uncovered.

With best regards,

Consultant, Dr. med. Sigrid Hørven Wigers

Project responsible

Specialist in Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation

R&D manager/Academic Director, Unicare Jeløy.

I consent to participate in this study: ○ Yes ○ No

A bit about you

This page is about you and your pain. We also wish to know a little about your comprehension of the pain cause and to which extent you feel you can control it. Answer each question to the best of your ability. Your answers are saved when you click “Next” at the bottom of the page. If you wish to go back to check or change what you already have answered, click “Previous”.

Gender: ○ Woman ○ Man

Age (in years) __________

How long have you been in pain? (Think back and enter the number of years at your best discretion) ____

Where do you have pain?

○ In the whole or large parts of the body

○ In one or few parts of the body

How long were you in pain before you received a diagnosis? (Estimate the number of years to the best of your ability) ____________

Mark that which is true for you. (Several markings are allowed. Let statements where the opposite is the case remain unanswered)

○ I do not understand why I am in pain

○ I do not know what I can do myself to get better from or get rid of, the pain

General practitioner services

On this page, we want your evaluation of the general practitioner’s competence in, and handling of, your pain problems, and to what extent the general practitioner's service has contributed to you getting better. Please answer all the questions to the best of your ability, it is your impression that we are seeking.

Have you consulted a general practitioner for your pain problems? ○ Yes ○ No

To what extent are your pain-related needs covered by the general practitioner? ○ To a very little extent ○ To a little extent ○ To a medium extent ○ To a great extent ○ To a very great extent

How great competence do you perceive the general practitioner has on your pain?

○ Very little○ Little○ Medium○ Great ○ Very great

Has the general practitioner given you satisfactory (comprehensible and meaningful) information on the pain cause? ○ Yes ○ No

Has the general practitioner given you specific and efficient guidance on what you can do yourself to get better? ○ To a very little extent ○ To a little extent ○ To a medium extent ○ To a great extent ○ To a very great extent

Are there any of the following services you miss having covered by your GP? (Mark the ones you may be missing. Several markings are allowed. Issues that are satisfactorily covered, or that you do not need, shall remain unmarked)

Clinical examination and pain assessment

Good and comprehensible pain explanation and guidance on what you can do yourself to get better

Regular follow-up and support

Further referral to a medical specialist

Further referral to other healthcare providers (i.e. physiotherapist, chiropractor, psychologist, etc.)

Analgesic medication

Application for benefits from the Norwegian Occupational and Welfare System (sick leave, work clearance money, disability pension, etc.)

Possibly other issues you miss to receive from your general practitioner (Please specify): ________________________

To what extent has the general practice service contributed to your pain relief? ○ To a very little extent, ○ To a little extent ○ To a medium extent ○ To a great extent ○ To a very great extent

Medical specialist services

It is common for pain patients to be further referred to medical specialists in various fields (rheumatology, physical medicine and rehabilitation, orthopedics, neurology, pain medicine, etc.). We seek your experience with the medical specialist service. If you have consulted several different specialists, we want your overall impression. Should someone stand out positively, you can specify how, and in which field, under “Other”. Avoid mentioning physician names.

Have you consulted a medical specialist? ○ Yes ○ No

How great competence do you perceive the medical specialists you have consulted have on your pain? ○ Very little○ Little○ Medium ○ Great ○ Very great

Has the medical specialist/s given you satisfactory (comprehensible and meaningful) information on the pain cause? ○ Yes ○ No

If ‘Yes’, indicate which specialty the specialist/s had: ___________________________________________________

Has the medical specialist/s given you specific and efficient guidance on what you can do yourself to get better? ○ To a very little extent ○ To a little extent ○ To a medium extent ○ To a great extent ○ To a very great extent

Other: (Specify, for example, if any specialty has stood out positively – do not give the physician’s name)

________________________________________________________

How do you regard that no medical specialty has specialized competence in muscle pain?

○ Very unfortunate○ Unfortunate ○ Neither nor ○ Good ○ Very good

To what extent has the medical specialist service contributed to your pain relief? ○ To a very little extent ○ To a little extent ○ To a medium extent ○ To a great extent ○ To a very great extent Other: (You may, for example, elaborate in what way some specialties have stood out - do not give the physician’s name) _______________________________________________________

Other health providers

This page is about your experience with other health providers without a physician-based medical education (physiotherapist, naprapath, osteopath, chiropractor, acupuncturist, psychologist, etc.). Once you have filled out the page, click “Finished”, and your completed response will be submitted automatically.

Have you consulted other health providers? (e.g. physiotherapist, naprapath, osteopath, chiropractor, acupuncturist, psychologist, etc.) ○ Yes ○ No

Who have given you satisfactory guidance on the pain cause and what you can do yourself to improve? (several markings allowed)

○ The general practitioner

○ Medical specialist

○ Other health providers

○ Nobody

If you have marked “Other health providers”, please specify what kind of health providers here: ___________

Do the explanations and advice different professionals have given you agree?

○ To a very little extent ○ To a little extent ○ To a medium extent ○ To a great extent ○ To a very great extent ○ Not received any explanation

How satisfied are you with the current scheme that other health providers without a physician-based medical education often are those who evaluate and treat your pain?

○ Very dissatisfied ○ Dissatisfied ○ Neither nor ○ Satisfied ○ Very satisfied

All in all, how satisfied are you with the healthcare system’s handling of your pain problems? (With the health care system, we mean both the primary- and specialist healthcare services plus other health providers seen as a whole.)

○ Very dissatisfied ○ Dissatisfied ○ Neither nor ○ Satisfied ○ Very satisfied

Thank you very much for your contribution! Your response is now complete.

Click ≪Finish≫, and your response will be delivered.

References

[1] Abd-Allah F, Abdulle AM, Abera SF, Abu-Raddad LJ, Adetokunboh O, Afshin A, et al. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 328 diseases and injuries for 195 countries, 1990–2016: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet. 2017;390:1211–59.Search in Google Scholar

[2] Andrews P, Steultjens M, Riskowski J. Chronic widespread pain prevalence in the general population: A systematic review. Eur J Pain. 2018;22:5–18.Search in Google Scholar

[3] Wolfe F. The history of the idea of widespread pain and its relation to fibromyalgia. Scand J Pain. 2020;20:647–50.Search in Google Scholar

[4] Nicholas M, Vlaeyen JWS, Rief W, Barke A, Aziz Q, Benoliel R, et al. The IASP classification of chronic pain for ICD-11: Chronic primary pain. Pain. 2019;160:28–37.Search in Google Scholar

[5] Yunus M, Masi AT, Calabro JJ, Miller KA, Feigenbaum SL. Primary fibromyalgia (fibrositis): Clinical study of 50 patients with matched normal controls. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1981;11:151–71.Search in Google Scholar

[6] Wolfe F, Clauw DJ, Fitzcharles MA, Goldenberg DL, Häuser W, Katz RL, et al. 2016 Revisions to the 2010/2011 fibromyalgia diagnostic criteria. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2016;46:319–29.Search in Google Scholar

[7] Gaskin DJ, Richard P. The economic costs of pain in the United States. J Pain. 2012;13:715–24.Search in Google Scholar

[8] Morales-Espinoza EM, Kostov B, Salami DC, Perez ZH, Rosalen AP, Molina JO, et al. Complexity, comorbidity, and health care costs associated with chronic widespread pain in primary care. Pain. 2016;157:818–26.Search in Google Scholar

[9] Kumbhare D, Ahmed S, Sander T, Grosman-Rimon L, Srbely J. A survey of physicians’ knowledge and adherence to the diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia. Pain Med. 2018;19:1254–64.Search in Google Scholar

[10] Perrot S, Choy E, Petersel D, Ginovker A, Kramer E. Survey of physician experiences and perceptions about the diagnosis and treatment of fibromyalgia. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:356.Search in Google Scholar

[11] Album D, Johannessen LEF, Rasmussen EB. Stability and change in disease prestige: A comparative analysis of three surveys spanning a quarter of a century. Soc Sci Med. 2017;180:45–51.Search in Google Scholar

[12] Briones-Vozmediano E, Vives-Cases C, Ronda-Pérez E, Gil-González D. Patients’ and professionals’ views on managing fibromyalgia. Pain Res Manag. 2013;18:19–24.Search in Google Scholar

[13] Brauer SG, Yoon JD, Curlin FA. Physician satisfaction in treating medically unexplained symptoms. South Med J. 2017;110:386–91.Search in Google Scholar

[14] Loeser JD, Schatman ME. Chronic pain management in medical education: a disastrous omission. Postgrad Med. 2017;129:332–5.Search in Google Scholar

[15] Silverwood V, Chew-Graham CA, Raybould I, Thomas B, Peters S. ‘If it’s a medical issue I would have covered it by now’: Learning about fibromyalgia through the hidden curriculum: a qualitative study. BMC Med Educ. 2017;17:160.Search in Google Scholar

[16] Sessle B. Unrelieved pain: A crisis. Pain Res Manag. 2011;16:416–20.Search in Google Scholar

[17] Staud R. Peripheral pain mechanisms in chronic widespread pain. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2011;25:155–64.Search in Google Scholar

[18] Henriksson KG. Is fibromyalgia a distinct clinical entity? Pain mechanisms in fibromyalgia syndrome. A myologist’s view. Baillieres Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 1999;13:455–61.Search in Google Scholar

[19] Affaitati G, Costantini R, Tana C, Cipollone F, Giamberardino MA. Co-occurrence of pain syndromes. J Neural Transm (Vienna). 2020;127:625–46.Search in Google Scholar

[20] Mengshoel AM. A long, winding trajectory of suffering with no definite start and uncertain future prospects - narratives of individuals recently diagnosed with fibromyalgia. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-Being. 2022;17:2056956. 10.1080/17482631.2022.2056956.Search in Google Scholar

[21] Paul-Savoie E, Bourgault P, Potvin S, Gosselin E, Lafrenaye S. The impact of pain invisibility on patient-centered care and empathetic attitude in chronic pain management. Pain Res Manag. 2018;2018:6375713. 10.1155/2018/6375713.Search in Google Scholar

[22] Doebl S, Hollick RJ, Beasley M, Choy E, Macfarlane GJ. Comparing the impact of symptoms and health care experiences of people who have and have not received a diagnosis of fibromyalgia: A cross-sectional survey within the PACFiND study. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2022;74:1894–902.Search in Google Scholar

[23] Doebl S, Macfarlane GJ, Hollick RJ. “No one wants to look after the fibro patient”. Understanding models, and patient perspectives, of care for fibromyalgia: reviews of current evidence. Pain. 2020;161:1716–25.Search in Google Scholar

[24] Gjengedal E, Sviland R, Moi AL, Ellingsen S, Flinterud SI, Sekse RJT, et al. Patients’ quest for recognition and continuity in health care: Time for a new research agenda? Scand J Caring Sci. 2019;33:978–85.Search in Google Scholar

[25] Macfarlane GJ, Kronisch C, Dean LE, Atzeni F, Häuser W, Fluß E, et al. EULAR revised recommendations for the management of fibromyalgia. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76:318–28.Search in Google Scholar

[26] Fitzcharles MA, Ste-Marie PA, Goldenberg DL, Pereira JX, Abbey S, Choinière M, et al. 2012 Canadian Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of fibromyalgia syndrome: executive summary. Pain Res Manag. 2013;18(3):119–26.Search in Google Scholar

[27] Arnold LM, Clauw DJ. Challenges of implementing fibromyalgia treatment guidelines in current clinical practice. Postgrad Med. 2017;129:709–14.Search in Google Scholar

[28] Nost TH, Stedenfeldt M, Steinsbekk A. “No one wants you” - a qualitative study on the experiences of receiving rejection from tertiary care pain centres. Scand J Pain. 2020;20:525–32.Search in Google Scholar

[29] Choy E, Perrot S, Leon T, Kaplan J, Petersel D, Ginovker A, et al. A patient survey of the impact of fibromyalgia and the journey to diagnosis. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10:102. 10.1186/1472-6963-10-102.Search in Google Scholar

[30] Mengshoel AM, Sim J, Ahlsen B, Madden S. Diagnostic experience of patients with fibromyalgia - A meta-ethnography. Chronic Illn. 2018;14:194–211.Search in Google Scholar

[31] Gendelman O, Amital H, Bar-On Y, Ben-Ami Shor D, Amital D, Tiosano S, et al. Time to diagnosis of fibromyalgia and factors associated with delayed diagnosis in primary care. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2018;32:489–99.Search in Google Scholar

[32] Lauche R, Häuser W, Jung E, Erbslöh-Möller B, Gesmann M, Kühn-Becker H, et al. Patient-related predictors of treatment satisfaction of patients with fibromyalgia syndrome: results of a cross-sectional survey. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2013;31(Suppl 79):S34–40.Search in Google Scholar

[33] Jung E, Erbslöh-Möller B, Gesmann M, Kühn-Becker H, Petermann F, Langhorst J, et al. Are members of fibromyalgia syndrome self-help groups “different”? Demographic and clinical characteristics of members and non-members of fibromyalgia syndrome self-help groups. Z Rheumatol. 2013;72:474–81.Search in Google Scholar

[34] Hughes G, Martinez C, Myon E, Taïeb C, Wessely S. The impact of a diagnosis of fibromyalgia on health care resource use by primary care patients in the UK: An observational study based on clinical practice. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:177–83.Search in Google Scholar

[35] Lynch ME, Campbell F, Clark AJ, Dunbar MJ, Goldstein D, Peng P, et al. A systematic review of the effect of waiting for treatment for chronic pain. Pain. 2008;136:97–116.Search in Google Scholar

[36] Annemans L, Wessely S, Spaepen E, Caekelbergh K, Caubère JP, Le Lay K, et al. Health economic consequences related to the diagnosis of fibromyalgia syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:895–902.Search in Google Scholar

[37] Wilson N, Beasley MJ, Pope C, Dulake D, Moir LJ, Hollick RJ, et al. UK healthcare services for people with fibromyalgia: Results from two web-based national surveys (the PACFiND study). BMC Health Serv Res. 2022;22:989. 10.1186/s12913-022-08324-4.Search in Google Scholar

[38] Peters ML. Emotional and cognitive influences on pain experience. Mod Trends Pharmacopsychiatry. 2015;30:138–52.Search in Google Scholar

[39] Bonica JJ. The management of pain. In John J. Bonica, John D. Loeser, C. Richard Chapman, Wilbert E. Fordyce, editors. 2nd edn. Philadelphia London: Lea & Febiger; 1990.Search in Google Scholar

[40] Bäckryd E. What do we mean by “biopsychosocial” in pain medicine? Scand J Pain. 2023;23:621–2.Search in Google Scholar

[41] Johansson M, Guyatt G, Montori V. Guidelines should consider clinicians’ time needed to treat. BMJ. 2023;380:e072953. 10.1136/bmj-2022-072953.Search in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Editorial Comment

- From pain to relief: Exploring the consistency of exercise-induced hypoalgesia

- Christmas greetings 2024 from the Editor-in-Chief

- Original Articles

- The Scandinavian Society for the Study of Pain 2022 Postgraduate Course and Annual Scientific (SASP 2022) Meeting 12th to 14th October at Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen

- Comparison of ultrasound-guided continuous erector spinae plane block versus continuous paravertebral block for postoperative analgesia in patients undergoing proximal femur surgeries

- Clinical Pain Researches

- The effect of tourniquet use on postoperative opioid consumption after ankle fracture surgery – a retrospective cohort study

- Changes in pain, daily occupations, lifestyle, and health following an occupational therapy lifestyle intervention: a secondary analysis from a feasibility study in patients with chronic high-impact pain

- Tonic cuff pressure pain sensitivity in chronic pain patients and its relation to self-reported physical activity

- Reliability, construct validity, and factorial structure of a Swedish version of the medical outcomes study social support survey (MOS-SSS) in patients with chronic pain

- Hurdles and potentials when implementing internet-delivered Acceptance and commitment therapy for chronic pain: a retrospective appraisal using the Quality implementation framework

- Exploring the outcome “days with bothersome pain” and its association with pain intensity, disability, and quality of life

- Fatigue and cognitive fatigability in patients with chronic pain

- The Swedish version of the pain self-efficacy questionnaire short form, PSEQ-2SV: Cultural adaptation and psychometric evaluation in a population of patients with musculoskeletal disorders

- Pain coping and catastrophizing in youth with and without cerebral palsy

- Neuropathic pain after surgery – A clinical validation study and assessment of accuracy measures of the 5-item NeuPPS scale

- Translation, contextual adaptation, and reliability of the Danish Concept of Pain Inventory (COPI-Adult (DK)) – A self-reported outcome measure

- Cosmetic surgery and associated chronic postsurgical pain: A cross-sectional study from Norway

- The association of hemodynamic parameters and clinical demographic variables with acute postoperative pain in female oncological breast surgery patients: A retrospective cohort study

- Healthcare professionals’ experiences of interdisciplinary collaboration in pain centres – A qualitative study

- Effects of deep brain stimulation and verbal suggestions on pain in Parkinson’s disease

- Painful differences between different pain scale assessments: The outcome of assessed pain is a matter of the choices of scale and statistics

- Prevalence and characteristics of fibromyalgia according to three fibromyalgia diagnostic criteria: A secondary analysis study

- Sex moderates the association between quantitative sensory testing and acute and chronic pain after total knee/hip arthroplasty

- Tramadol-paracetamol for postoperative pain after spine surgery – A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study

- Cancer-related pain experienced in daily life is difficult to communicate and to manage – for patients and for professionals

- Making sense of pain in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD): A qualitative study

- Patient-reported pain, satisfaction, adverse effects, and deviations from ambulatory surgery pain medication

- Does pain influence cognitive performance in patients with mild traumatic brain injury?

- Hypocapnia in women with fibromyalgia

- Application of ultrasound-guided thoracic paravertebral block or intercostal nerve block for acute herpes zoster and prevention of post-herpetic neuralgia: A case–control retrospective trial

- Translation and examination of construct validity of the Danish version of the Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia

- A positive scratch collapse test in anterior cutaneous nerve entrapment syndrome indicates its neuropathic character

- ADHD-pain: Characteristics of chronic pain and association with muscular dysregulation in adults with ADHD

- The relationship between changes in pain intensity and functional disability in persistent disabling low back pain during a course of cognitive functional therapy

- Intrathecal pain treatment for severe pain in patients with terminal cancer: A retrospective analysis of treatment-related complications and side effects

- Psychometric evaluation of the Danish version of the Pain Self-Efficacy Questionnaire in patients with subacute and chronic low back pain

- Dimensionality, reliability, and validity of the Finnish version of the pain catastrophizing scale in chronic low back pain

- To speak or not to speak? A secondary data analysis to further explore the context-insensitive avoidance scale

- Pain catastrophizing levels differentiate between common diseases with pain: HIV, fibromyalgia, complex regional pain syndrome, and breast cancer survivors

- Prevalence of substance use disorder diagnoses in patients with chronic pain receiving reimbursed opioids: An epidemiological study of four Norwegian health registries

- Pain perception while listening to thrash heavy metal vs relaxing music at a heavy metal festival – the CoPainHell study – a factorial randomized non-blinded crossover trial

- Observational Studies

- Cutaneous nerve biopsy in patients with symptoms of small fiber neuropathy: a retrospective study

- The incidence of post cholecystectomy pain (PCP) syndrome at 12 months following laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a prospective evaluation in 200 patients

- Associations between psychological flexibility and daily functioning in endometriosis-related pain

- Relationship between perfectionism, overactivity, pain severity, and pain interference in individuals with chronic pain: A cross-lagged panel model analysis

- Access to psychological treatment for chronic cancer-related pain in Sweden

- Validation of the Danish version of the knowledge and attitudes survey regarding pain

- Associations between cognitive test scores and pain tolerance: The Tromsø study

- Healthcare experiences of fibromyalgia patients and their associations with satisfaction and pain relief. A patient survey

- Video interpretation in a medical spine clinic: A descriptive study of a diverse population and intervention

- Role of history of traumatic life experiences in current psychosomatic manifestations

- Social determinants of health in adults with whiplash associated disorders

- Which patients with chronic low back pain respond favorably to multidisciplinary rehabilitation? A secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial

- A preliminary examination of the effects of childhood abuse and resilience on pain and physical functioning in patients with knee osteoarthritis

- Differences in risk factors for flare-ups in patients with lumbar radicular pain may depend on the definition of flare

- Real-world evidence evaluation on consumer experience and prescription journey of diclofenac gel in Sweden

- Patient characteristics in relation to opioid exposure in a chronic non-cancer pain population

- Topical Reviews

- Bridging the translational gap: adenosine as a modulator of neuropathic pain in preclinical models and humans

- What do we know about Indigenous Peoples with low back pain around the world? A topical review

- The “future” pain clinician: Competencies needed to provide psychologically informed care

- Systematic Reviews

- Pain management for persistent pain post radiotherapy in head and neck cancers: systematic review

- High-frequency, high-intensity transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation compared with opioids for pain relief after gynecological surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis

- Reliability and measurement error of exercise-induced hypoalgesia in pain-free adults and adults with musculoskeletal pain: A systematic review

- Noninvasive transcranial brain stimulation in central post-stroke pain: A systematic review

- Short Communications

- Are we missing the opioid consumption in low- and middle-income countries?

- Association between self-reported pain severity and characteristics of United States adults (age ≥50 years) who used opioids

- Could generative artificial intelligence replace fieldwork in pain research?

- Skin conductance algesimeter is unreliable during sudden perioperative temperature increases

- Original Experimental

- Confirmatory study of the usefulness of quantum molecular resonance and microdissectomy for the treatment of lumbar radiculopathy in a prospective cohort at 6 months follow-up

- Pain catastrophizing in the elderly: An experimental pain study

- Improving general practice management of patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain: Interdisciplinarity, coherence, and concerns

- Concurrent validity of dynamic bedside quantitative sensory testing paradigms in breast cancer survivors with persistent pain

- Transcranial direct current stimulation is more effective than pregabalin in controlling nociceptive and anxiety-like behaviors in a rat fibromyalgia-like model

- Paradox pain sensitivity using cuff pressure or algometer testing in patients with hemophilia

- Physical activity with person-centered guidance supported by a digital platform or with telephone follow-up for persons with chronic widespread pain: Health economic considerations along a randomized controlled trial

- Measuring pain intensity through physical interaction in an experimental model of cold-induced pain: A method comparison study

- Pharmacological treatment of pain in Swedish nursing homes: Prevalence and associations with cognitive impairment and depressive mood

- Neck and shoulder pain and inflammatory biomarkers in plasma among forklift truck operators – A case–control study

- The effect of social exclusion on pain perception and heart rate variability in healthy controls and somatoform pain patients

- Revisiting opioid toxicity: Cellular effects of six commonly used opioids

- Letter to the Editor

- Post cholecystectomy pain syndrome: Letter to Editor

- Response to the Letter by Prof Bordoni

- Response – Reliability and measurement error of exercise-induced hypoalgesia

- Is the skin conductance algesimeter index influenced by temperature?

- Skin conductance algesimeter is unreliable during sudden perioperative temperature increase

- Corrigendum

- Corrigendum to “Chronic post-thoracotomy pain after lung cancer surgery: a prospective study of preoperative risk factors”

- Obituary

- A Significant Voice in Pain Research Björn Gerdle in Memoriam (1953–2024)

Articles in the same Issue

- Editorial Comment

- From pain to relief: Exploring the consistency of exercise-induced hypoalgesia

- Christmas greetings 2024 from the Editor-in-Chief

- Original Articles

- The Scandinavian Society for the Study of Pain 2022 Postgraduate Course and Annual Scientific (SASP 2022) Meeting 12th to 14th October at Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen

- Comparison of ultrasound-guided continuous erector spinae plane block versus continuous paravertebral block for postoperative analgesia in patients undergoing proximal femur surgeries

- Clinical Pain Researches

- The effect of tourniquet use on postoperative opioid consumption after ankle fracture surgery – a retrospective cohort study

- Changes in pain, daily occupations, lifestyle, and health following an occupational therapy lifestyle intervention: a secondary analysis from a feasibility study in patients with chronic high-impact pain

- Tonic cuff pressure pain sensitivity in chronic pain patients and its relation to self-reported physical activity

- Reliability, construct validity, and factorial structure of a Swedish version of the medical outcomes study social support survey (MOS-SSS) in patients with chronic pain

- Hurdles and potentials when implementing internet-delivered Acceptance and commitment therapy for chronic pain: a retrospective appraisal using the Quality implementation framework

- Exploring the outcome “days with bothersome pain” and its association with pain intensity, disability, and quality of life

- Fatigue and cognitive fatigability in patients with chronic pain

- The Swedish version of the pain self-efficacy questionnaire short form, PSEQ-2SV: Cultural adaptation and psychometric evaluation in a population of patients with musculoskeletal disorders

- Pain coping and catastrophizing in youth with and without cerebral palsy

- Neuropathic pain after surgery – A clinical validation study and assessment of accuracy measures of the 5-item NeuPPS scale

- Translation, contextual adaptation, and reliability of the Danish Concept of Pain Inventory (COPI-Adult (DK)) – A self-reported outcome measure

- Cosmetic surgery and associated chronic postsurgical pain: A cross-sectional study from Norway

- The association of hemodynamic parameters and clinical demographic variables with acute postoperative pain in female oncological breast surgery patients: A retrospective cohort study

- Healthcare professionals’ experiences of interdisciplinary collaboration in pain centres – A qualitative study

- Effects of deep brain stimulation and verbal suggestions on pain in Parkinson’s disease

- Painful differences between different pain scale assessments: The outcome of assessed pain is a matter of the choices of scale and statistics

- Prevalence and characteristics of fibromyalgia according to three fibromyalgia diagnostic criteria: A secondary analysis study

- Sex moderates the association between quantitative sensory testing and acute and chronic pain after total knee/hip arthroplasty

- Tramadol-paracetamol for postoperative pain after spine surgery – A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study

- Cancer-related pain experienced in daily life is difficult to communicate and to manage – for patients and for professionals

- Making sense of pain in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD): A qualitative study

- Patient-reported pain, satisfaction, adverse effects, and deviations from ambulatory surgery pain medication

- Does pain influence cognitive performance in patients with mild traumatic brain injury?

- Hypocapnia in women with fibromyalgia

- Application of ultrasound-guided thoracic paravertebral block or intercostal nerve block for acute herpes zoster and prevention of post-herpetic neuralgia: A case–control retrospective trial

- Translation and examination of construct validity of the Danish version of the Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia

- A positive scratch collapse test in anterior cutaneous nerve entrapment syndrome indicates its neuropathic character

- ADHD-pain: Characteristics of chronic pain and association with muscular dysregulation in adults with ADHD

- The relationship between changes in pain intensity and functional disability in persistent disabling low back pain during a course of cognitive functional therapy

- Intrathecal pain treatment for severe pain in patients with terminal cancer: A retrospective analysis of treatment-related complications and side effects

- Psychometric evaluation of the Danish version of the Pain Self-Efficacy Questionnaire in patients with subacute and chronic low back pain

- Dimensionality, reliability, and validity of the Finnish version of the pain catastrophizing scale in chronic low back pain

- To speak or not to speak? A secondary data analysis to further explore the context-insensitive avoidance scale

- Pain catastrophizing levels differentiate between common diseases with pain: HIV, fibromyalgia, complex regional pain syndrome, and breast cancer survivors

- Prevalence of substance use disorder diagnoses in patients with chronic pain receiving reimbursed opioids: An epidemiological study of four Norwegian health registries

- Pain perception while listening to thrash heavy metal vs relaxing music at a heavy metal festival – the CoPainHell study – a factorial randomized non-blinded crossover trial

- Observational Studies

- Cutaneous nerve biopsy in patients with symptoms of small fiber neuropathy: a retrospective study

- The incidence of post cholecystectomy pain (PCP) syndrome at 12 months following laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a prospective evaluation in 200 patients

- Associations between psychological flexibility and daily functioning in endometriosis-related pain

- Relationship between perfectionism, overactivity, pain severity, and pain interference in individuals with chronic pain: A cross-lagged panel model analysis

- Access to psychological treatment for chronic cancer-related pain in Sweden

- Validation of the Danish version of the knowledge and attitudes survey regarding pain

- Associations between cognitive test scores and pain tolerance: The Tromsø study

- Healthcare experiences of fibromyalgia patients and their associations with satisfaction and pain relief. A patient survey

- Video interpretation in a medical spine clinic: A descriptive study of a diverse population and intervention

- Role of history of traumatic life experiences in current psychosomatic manifestations

- Social determinants of health in adults with whiplash associated disorders

- Which patients with chronic low back pain respond favorably to multidisciplinary rehabilitation? A secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial

- A preliminary examination of the effects of childhood abuse and resilience on pain and physical functioning in patients with knee osteoarthritis

- Differences in risk factors for flare-ups in patients with lumbar radicular pain may depend on the definition of flare

- Real-world evidence evaluation on consumer experience and prescription journey of diclofenac gel in Sweden

- Patient characteristics in relation to opioid exposure in a chronic non-cancer pain population

- Topical Reviews

- Bridging the translational gap: adenosine as a modulator of neuropathic pain in preclinical models and humans

- What do we know about Indigenous Peoples with low back pain around the world? A topical review

- The “future” pain clinician: Competencies needed to provide psychologically informed care

- Systematic Reviews

- Pain management for persistent pain post radiotherapy in head and neck cancers: systematic review

- High-frequency, high-intensity transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation compared with opioids for pain relief after gynecological surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis

- Reliability and measurement error of exercise-induced hypoalgesia in pain-free adults and adults with musculoskeletal pain: A systematic review

- Noninvasive transcranial brain stimulation in central post-stroke pain: A systematic review

- Short Communications

- Are we missing the opioid consumption in low- and middle-income countries?

- Association between self-reported pain severity and characteristics of United States adults (age ≥50 years) who used opioids

- Could generative artificial intelligence replace fieldwork in pain research?

- Skin conductance algesimeter is unreliable during sudden perioperative temperature increases

- Original Experimental

- Confirmatory study of the usefulness of quantum molecular resonance and microdissectomy for the treatment of lumbar radiculopathy in a prospective cohort at 6 months follow-up

- Pain catastrophizing in the elderly: An experimental pain study

- Improving general practice management of patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain: Interdisciplinarity, coherence, and concerns

- Concurrent validity of dynamic bedside quantitative sensory testing paradigms in breast cancer survivors with persistent pain

- Transcranial direct current stimulation is more effective than pregabalin in controlling nociceptive and anxiety-like behaviors in a rat fibromyalgia-like model

- Paradox pain sensitivity using cuff pressure or algometer testing in patients with hemophilia

- Physical activity with person-centered guidance supported by a digital platform or with telephone follow-up for persons with chronic widespread pain: Health economic considerations along a randomized controlled trial

- Measuring pain intensity through physical interaction in an experimental model of cold-induced pain: A method comparison study

- Pharmacological treatment of pain in Swedish nursing homes: Prevalence and associations with cognitive impairment and depressive mood

- Neck and shoulder pain and inflammatory biomarkers in plasma among forklift truck operators – A case–control study

- The effect of social exclusion on pain perception and heart rate variability in healthy controls and somatoform pain patients

- Revisiting opioid toxicity: Cellular effects of six commonly used opioids

- Letter to the Editor

- Post cholecystectomy pain syndrome: Letter to Editor

- Response to the Letter by Prof Bordoni

- Response – Reliability and measurement error of exercise-induced hypoalgesia

- Is the skin conductance algesimeter index influenced by temperature?

- Skin conductance algesimeter is unreliable during sudden perioperative temperature increase

- Corrigendum

- Corrigendum to “Chronic post-thoracotomy pain after lung cancer surgery: a prospective study of preoperative risk factors”

- Obituary

- A Significant Voice in Pain Research Björn Gerdle in Memoriam (1953–2024)