Experimental study on mechanical properties and microstructures of steel fiber-reinforced fly ash-metakaolin geopolymer-recycled concrete

-

Zhong Xu

, Zhenpu Huang

, Xiaowei Deng

, David Hui

, Yuting Deng

Abstract

Geopolymer cementitious materials and recycled aggregate are typical representatives of material innovation research in the engineering field. In this study, we experimentally investigated a method to improve the performance of geopolymer-recycled aggregate concrete (GRAC). The recycled concrete aggregates and steel fiber (SF), fly ash (FA), metakaolin (MK), and sodium silicate solution were used as the main raw materials to prepare fiber-reinforced geopolymer-recycled aggregate concrete (FRGRAC). First, the orthogonal test was carried out to study the GRAC, and the optimal mix proportion was found. Second, building on the optimal mix proportion, the effects of the SF content on the slump, 7 and 28 days compressive strength, tensile strength, and flexural strength of FRGRAC were further studied. Finally, the microscopic mechanism of FRGRAC was studied by scanning electron microscopy (SEM). The study results indicate that the slump continues to decrease as the fiber content increases, but the compressive strength, tensile strength, and flexural strength increase to a certain extent. Through SEM analysis, it is found that SF restrains the development of cracks and improves the strength of concrete.

1 Introduction

With the growth of the global population and the acceleration of urbanization, the development of the construction industry has been greatly promoted, but this has also exacerbated the problem of environmental pollution. Statistics shows that the annual output of global cement production will increase to 6.1 billion tons in 2050, which means extremely high CO2 emissions (7% of global carbon emissions) [1,2]. On the other hand, urbanization needs to demolish old buildings, which will undoubtedly generate a lot of construction waste. The stacking of construction waste will consume a lot of land resources, and if not handled properly, it will cause harm to soil and water [3,4].

The emergence of GRAC can be one of the promising solutions for the above problems. Geopolymers are mainly derived from industrial production wastes. Combining these raw materials rich in silicon and aluminum compounds, such as FA, MK, etc., with an alkali solution will cause polymerization. After polymerization, geopolymer concrete (GPC) can be formed with a higher strength than that of ordinary Portland concrete (OPC) [5]. Therefore, replacing cement with a geopolymer can be an ideal choice, which can greatly reduce the emission of CO2 [6]. On the other hand, recycled aggregate concrete (RAC) can also solve the problem of construction waste disposal. The test blocks of waste concrete are usually crushed, cleaned, graded, and mixed according to a certain proportion to prepare recycled concrete aggregate (RCA). The concrete made by RCA is called RAC [7,8]. A combination of GPC and RAC can greatly solve the pollution problem in civil engineering construction.

However, due to the high porosity of the residual mortar in RCA, the strength of RCA is generally low, which affects the strength of GRAC [9,10]. GRAC also exhibits brittleness similar to OPC [11,12]. These limit the application of GRAC. The addition of fiber can reduce the brittleness of concrete and effectively improve the strength of concrete. At present, the study on using fiber to improve GPC [13,14,15,16,17,18] and RAC [19,20,21,22] has matured. But, most of the current research in the field of GRAC focuses on improving its strength, crack resistance [23,24,25,26,27], etc., and the use of fiber to improve GRAC is still lacking.

This article presents using steel fiber (SF) and FA–MK matrix geopolymer cementing material to prepare fiber-reinforced geopolymer recycled aggregate concrete (FRGRAC). Based on the orthogonal test considering three factors and three levels and considering the 7 days compressive strength as the index, the influence factors of GRAC compressive strength are studied and the optimal mix proportion is found. Based on this, the effects of the SF content on the slump of FRGRAC, compressive strength, tensile strength, and flexural strength of 28 days were investigated. Furthermore, its microscopic mechanism was analyzed by SEM. It is expected that the results from this study can help establish a foundation for the FRGRAC application in engineering practice in the future.

2 Materials and methodology

2.1 Experimental materials

Class II FA was provided by Chuanxing Mineral Powder Factory. MK calcined at 900°C was produced by Henan Jinao Refractory Co., Ltd. Concentrated sodium silicate solution with a modulus of 2.2 was 40%, and the purity of flake NaOH was greater than 99%. RCA was selected from the laboratory waste concrete block. SF with a tensile strength of 577 MPa and a density of 7,650 kg·m−3 was supplied by Changzhou Bochao Engineering Material Co. Ltd. The materials are shown in Figure 1, the fly ash (FA) and metakaolin (MK) are shown in Table 1, and the properties of coarse aggregates are shown in Table 2.

Photographs of materials.

Chemical composition table of FA and MK

| Materials | SiO2 | Al2O3 | CaO | Fe2O3 | TiO2 | SO3 | MgO | K2O | Na2O | Ignition loss |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FA | 50.80 | 28.10 | 3.70 | 6.20 | 0.00 | 1.80 | 1.20 | 0.60 | 1.20 | 7.90 |

| MK | 55.06 | 44.12 | 0.17 | 0.76 | 0.24 | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.55 | 0.06 | 0.62 |

Performance indicators of recycled coarse aggregate

| Particle size (mm) | Water absorption (%) | Crushing index (%) | Apparent density (kg·m−3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5–19 | 4.97 | 14.78 | 2,490 |

2.2 Orthogonal test and mix proportion design

The orthogonal test is a scientific method that can deal with multifactor and multilevel tests. Under the premise of ensuring accuracy, it can greatly reduce the number of tests [28,29]. For GPC and RAC, the modulus of alkali activator [30], the aggregate cementitious material ratio [31], and the sand ratio [32,33] have significant effects on their strength. Therefore, in this experiment, we use these three factors as variables and select three levels for each factor. With 7 days compressive strength as an indicator, the ratio of the fixed water cementitious material is 0.30 and the ratio of FA/MK is 1:1 [34], The orthogonal test is carried out, and L9 (33) table is selected to arrange the test. At the same time, in order to avoid accidental errors, a range analysis was carried out on the test results. The orthogonal table is shown in Table 3, and the mix proportion is shown in Table 4.

Orthogonal test table

| Level | Factors | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sand ratio | Aggregate cement material ratio | Modulus | |

| 1 | 0.40 | 3.00 | 1.20 |

| 2 | 0.35 | 3.50 | 1.10 |

| 3 | 0.30 | 4.00 | 1.00 |

Design table of GRAC mix proportion (kg·m−3)

| Test group | MK | FA | Sodium silicate | NaOH | Sand | Recycled aggregate | Sand ratio | Aggregate cement material ratio | Modulus |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | 295.33 | 295.33 | 301.32 | 36.15 | 708.79 | 1063.18 | 0.40 | 3.00 | 1.20 |

| P2 | 265.49 | 265.49 | 270.80 | 39.81 | 743.36 | 1115.04 | 0.40 | 3.50 | 1.10 |

| P3 | 241.07 | 241.07 | 245.89 | 43.28 | 771.43 | 1157.14 | 0.40 | 4.00 | 1.00 |

| P4 | 294.44 | 294.44 | 300.33 | 44.15 | 618.32 | 1148.31 | 0.35 | 3.00 | 1.10 |

| P5 | 264.71 | 264.71 | 270.00 | 47.52 | 648.53 | 1204.41 | 0.35 | 3.50 | 1.00 |

| P6 | 242.32 | 242.32 | 247.16 | 29.66 | 678.49 | 1260.05 | 0.35 | 4.00 | 1.20 |

| P7 | 293.48 | 293.48 | 299.35 | 52.69 | 528.26 | 1232.61 | 0.30 | 3.00 | 1.00 |

| P8 | 266.21 | 266.21 | 271.53 | 32.58 | 559.04 | 1304.43 | 0.30 | 3.50 | 1.20 |

| P9 | 241.72 | 241.72 | 246.53 | 36.24 | 580.13 | 1353.63 | 0.30 | 4.00 | 1.10 |

Note: The ratio of aggregate cementitious material is mass of (RCA + sand)/mass of (MK + FA); the ratio of water cementitious material is mass of sodium silicate solution solvent/mass of (MK + FA); sand ratio is the mass of sand/quality of (sand + RCA).

2.3 Specimen preparation and curing

The alkali activator solution (NaOH, mixed sodium silicate solution) was prepared in advance and was left to cool to room temperature for 12 h, as shown in Figure 2. FA and MK were mixed for 60 s; soon after, the alkali activator solution was added and the mixture was stirred for 90 s. Then, SF was added to the mixture and it was stirred at a constant speed until the fibers were evenly distributed without coagulation and agglomeration, as shown in Figure 3. Finally, the aggregate was added and it was stirred for 120 s. After the mixture was stirred with all materials, it was poured into the mold and shook; soon after, it was placed with the film in an oven at 80°C and dried for 20 h [35,36] to demold, as shown in Figure 4. Later, it was dried in the open air (25°C) and was cured to the specified age [37,38], as shown in Figure 5. The whole production process is shown in Figure 6.

Alkali activator solution.

The process of casting concrete samples: (a) mixing concrete and (b) filling in the mold.

Maintenance of the cover film.

Concrete curing.

Production flow chart.

2.4 Test methods

2.4.1 Slump test

After the concrete was mixed, the slump cylinder was used to test the slump of different test groups within 5 min. The concrete needs to be filled three times. After each filling, a vibrating rod must be used to strike the barrel wall 25 times from the inside to the outside. After three fillings, the concrete on the surface of the slump is smoothed and then the slump is quickly lifted to measure its slump. The test process is shown in Figure 7.

Slump test.

2.4.2 Compressive strength test

Figure 8 shows the compressive strength test apparatus with the measuring accuracy of ±1%. Based on the previous experience and research results [39], the loading speed is set at 0.5 MPa·s−1, and the average compressive strength of each test group is taken from three specimens. As the concrete specimens in this test are 100 mm

where F is the compressive failure load and A is the bearing area of the specimen.

Compressive strength test apparatus.

2.4.3 Splitting tensile strength test

Figure 9 shows the tensile strength test apparatus. Wood chips are placed on the bottom of the fixture to ensure the stability of the specimen during testing. The specimen is put into the fixture and another piece of wood is placed on the top surface of the specimen to ensure stability and uniform force. The loading speed is set at 0.5 MPa·s−1. As the concrete specimens in this test are 100 mm

where F is the splitting failure load (N) and A is the bearing area of the splitting (mm2).

Tensile strength test apparatus.

2.4.4 Flexural strength test

Figure 10 shows the flexural strength test apparatus. The positions of the two supports are adjusted according to the length of the test piece. The final distance between the two supports is 300 mm, and the distance between the two supports and the two sides of the concrete is approximately the same. The loading speed is set at 0.08 MPa·s−1. As the concrete specimens in this test are 100 mm × 100 mm × 400 mm nonstandard specimens, the compressive strength is calculated according to the following formula:

where F is the flexural failure load (N), l is the support span (mm), b is the width of the specimen (mm). and h is the height of the test piece (mm).

Flexural strength test apparatus.

2.5 SEM analysis

A scanning electron microscope is a type of electron microscope that generates sample images by scanning the surface with a focused electron beam, which is used to observe and test the surface microscopic morphology of the sample. The instrument used in this experiment is Prisma-E SEM equipment, as shown in Figure 11. The magnification of Prisma-E scanning electron microscope is 5–300,000 times, the subelectron resolution is 30 nm, the acceleration voltage is 0.3–30 kV (adjustable fixed bias), and the moving range of the sample is 100 mm inward, towards inner 50 mm, and 5.35 mm inward. The rotation angle is 360° and the temperature range is 20 + 90°.

SEM observation apparatus.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Orthogonal test results

The orthogonal test results are shown in Table 5, and the histogram is shown in Figure 12. It can be found from the figure that the 7 days compressive strength of the P5 group is the highest at 34.4 MPa, and the P1 group is the lowest at 18.2 MPa. The range analysis was performed on these results and the average value

Orthogonal test results

| Test group | Sand ratio | Aggregate cement material ratio | Modulus | 7 days compressive strength (MPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | 0.40 | 3.00 | 1.20 | 18.2 |

| P2 | 0.40 | 3.50 | 1.10 | 24.1 |

| P3 | 0.40 | 4.00 | 1.00 | 26.8 |

| P4 | 0.35 | 3.00 | 1.10 | 20.3 |

| P5 | 0.35 | 3.50 | 1.00 | 34.4 |

| P6 | 0.35 | 4.00 | 1.20 | 20.9 |

| P7 | 0.30 | 3.00 | 1.00 | 27.8 |

| P8 | 0.30 | 3.50 | 1.20 | 16.4 |

| P9 | 0.30 | 4.00 | 1.10 | 24.4 |

Orthogonal test results.

Range analysis table

| Factors | 7 days compressive strength (MPa) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

R | |||

| Sand ratio | 23.03 | 25.20 | 22.87 | 2.33 |

| Aggregate cement material ratio | 22.10 | 24.97 | 24.03 | 2.87 |

| Modulus | 18.50 | 22.93 | 29.67 | 11.17 |

Trend chart of each factor level.

3.2 FRGRAC research results

On the basis of the P5 test group, SF was added to analyze the slump, compressive strength, tensile strength, and flexural strength of FRGRAC when the fiber content was 0.00, 0.50, 1.00, 1.50, 2.00, and 2.50%, respectively, The mix proportion of FRGRAC is shown in Table 7.

FRGRAC mix proportion (kg·m−3)

| Test group | MK | FA | Sodium silicate | NaOH | Sand | Recycled aggregate | SF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | 264.71 | 264.71 | 270.00 | 47.52 | 648.53 | 1204.41 | 0.00 |

| SF-0.50 | 264.71 | 264.71 | 270.00 | 47.52 | 648.53 | 1204.41 | 38.25 |

| SF-1.00 | 264.71 | 264.71 | 270.00 | 47.52 | 648.53 | 1204.41 | 76.50 |

| SF-1.50 | 264.71 | 264.71 | 270.00 | 47.52 | 648.53 | 1204.41 | 114.75 |

| SF-2.00 | 264.71 | 264.71 | 270.00 | 47.52 | 648.53 | 1204.41 | 153.00 |

| SF-2.50 | 264.71 | 264.71 | 270.00 | 47.52 | 648.53 | 1204.41 | 191.25 |

3.2.1 FRGRAC slump

No bleeding phenomenon was observed throughout the experiment. The FRGRAC slump results are shown in Figure 14. It can be observed from the figure that the slump of FRGRAC decreases continuously with the increase of fiber content. As the fiber content increases, the friction in the material continues to increase, which inhibits the flow of the material, and the fiber itself can also act as a bridge to prevent the material from slipping. On further observation, it was found that the slump difference between the M standard group and the SF-0.50 test group is the largest (31 mm), which is greater than the slump difference of the different fiber content test groups.

Slump test result.

3.2.2 Compressive strength of FRGRAC

Figure 15 shows the FRGRAC 7 and 28 days compressive strength test results of each test group. It can be found that the 7 days compressive strength is 84.52% of the 28 days compressive strength of the M test group. At the same time, except for the 28 days SF-2.00 test group, the compressive strengths of the other groups increase with the increase of fiber content. When the fiber content was 2.50%, the compressive strength at 7 and 28 days were 38.97 and 47.1 MPa, respectively, which were 13.25 and 15.72% higher than that of the M group. The main reason for the above phenomenon is that the fiber can play a bridging role, helping to transfer and bear the stress, thereby increasing the compressive strength. At the same time, the fiber can also play the role of a hoop inside the concrete and can also improve the compressive strength under three-direction stress. But, on the other hand, due to the low crushing index of FRGRAC’s recycled aggregate in this experiment, it has certain instability and the pouring process is not completed at one time. Therefore, some test groups may have higher aggregate residual mortar content, resulting in a decrease in the overall strength, such as the 28 days SF-2.00 test group. However, on the whole, the effect of fiber on the compressive strength of FRGRAC is more obvious and the optimal fiber content has not been found. In this respect, it is significantly different from GPC and RAC. Under normal circumstances, the optimal content of fiber-reinforced GPC and RAC is between 1.0 and 1.5% [17,18,19]. This is due to the high ratio of water cementitious material. It can produce a large number of C–S–H gels. Even if the fiber content is increased, the C–S–H gel can still wrap the fibers tightly and not increase the porosity rate like in other types of concrete, thereby reducing the strength. On the other hand, because the strength of RCA in this test is low, the strength of FRGRAC made of recycled aggregate is affected by RCA, which does not show the strength of cementitious material itself. Therefore, even if a large amount of SF is added, it still does not reach the upper limit of the material strength and so the optimal content is not found.

Compressive strength test results.

Figure 16 shows the uniaxial compression test of the test block. It can be found that the damage of FRGRAC after the fiber addition is a failure with a certain amount of plastic deformation, indicating that the fiber strengthens the integrity of the test block and inhibits the generation of cracks.

Test conditions of test block: (a) no added fiber specimen and (b) fiber-reinforced specimen.

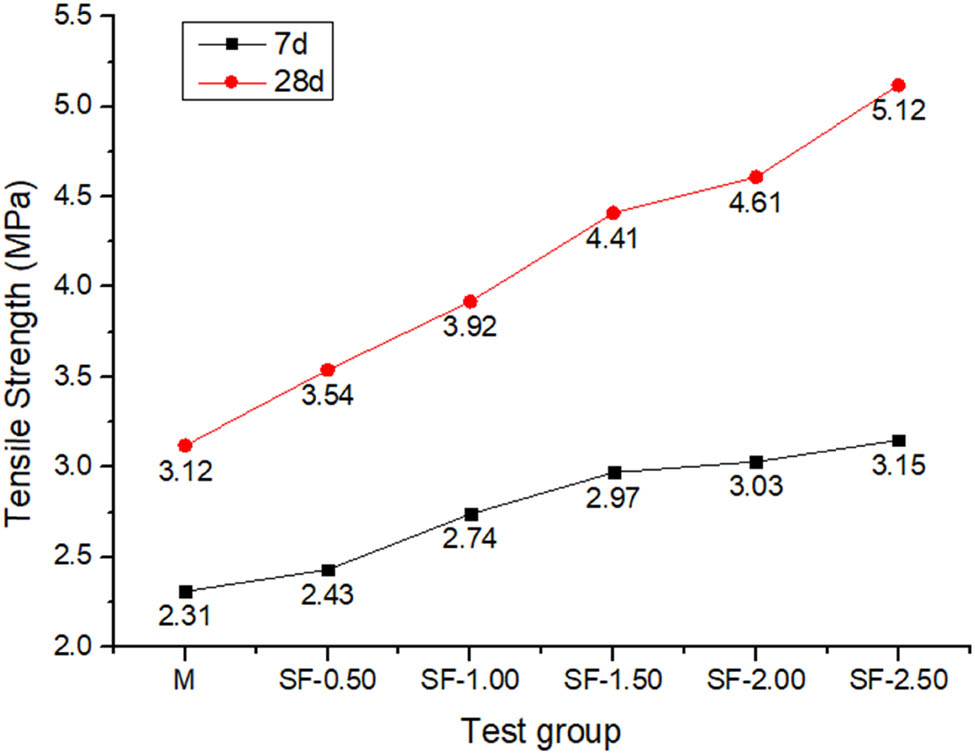

3.2.3 Tensile and flexural strength results of FRGRAC

Figures 17 and 18, respectively, show the tensile strength and flexural strength results of FRGRAC. It can be seen from Figure 17 that the tensile strength of FRGRAC increases continuously with the increase of fiber content and there is no inflection point. It shows that the incorporation of the fiber has a relatively continuous and stable improvement effect on the tensile strength of FRGRAC. When the fiber content is 2.5%, the tensile strengths of 7 and 28 days are 3.15 and 5.12 MPa, respectively, which are 36.36 and 64.10% higher than that of the M test group. This aspect is due to the high tensile strength of SF itself, which forms a stable three-dimensional grid system in the concrete, which improves the distribution, transmission, and bearing of stress, thereby enhancing the tensile strength.

Tensile strength test results.

Flexural strength test results.

On the other hand, it is also because of the good bonding performance between the SF and mortar. When the concrete cracks under tension, the fibers bear the main tensile stress. At this time, the fiber and the mortar are required to have good bonding properties. Further study can find that the improvement of the tensile strength of different test groups has a significant decrease in the 28 days SF-2.00 group, which is similar to the mechanism of the decrease of compressive strength. It also shows that the improvement of the tensile strength of FRGRAC by SF is better than that of compressive strength.

It can be found from Figure 18 that the flexural strength is the same as the tensile strength and both are steadily improved. When the fiber content is 2.5%, the flexural strength of 7 days and 28 days is 6.22 and 7.79 MPa, respectively, which are 67.2 and 60.95% higher than that of the M test group, and the degree of shaping is improved. The damage of the test block is shown in Figure 19. The modification mechanism is similar to the tensile strength and therefore it is not explained here.

Flexural failure of test blocks with different fiber contents: (a) 1.00% fiber-reinforced specimen and (b) 2.50% fiber-reinforced specimen.

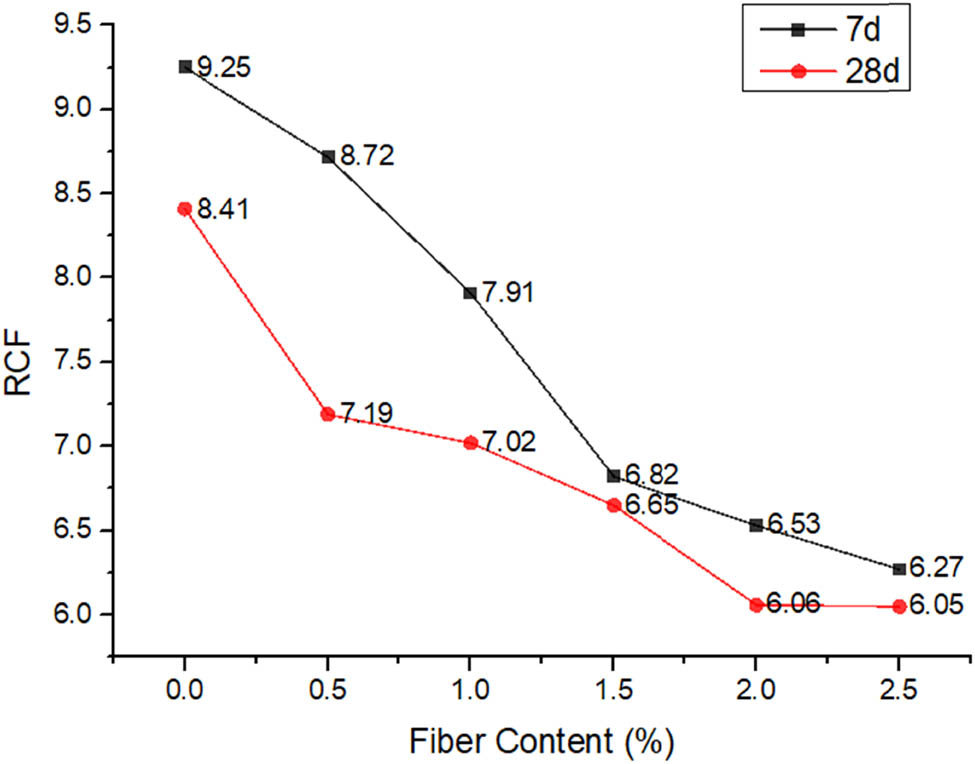

Figure 20 shows the ratio of compressive strength/flexural strength (RCF) at 7 and 28 days. It can be found from the figure that the 7 days RCF of each test group is greater than the 28 days RCF. It shows that the plasticity of 7 days block is lower than that of 28 days block. With the increase of fiber content, the RCF of 7 or 28 days test block decreases, which indicates that fiber can improve the toughness of concrete at all ages.

Effect of different fiber contents on RCF.

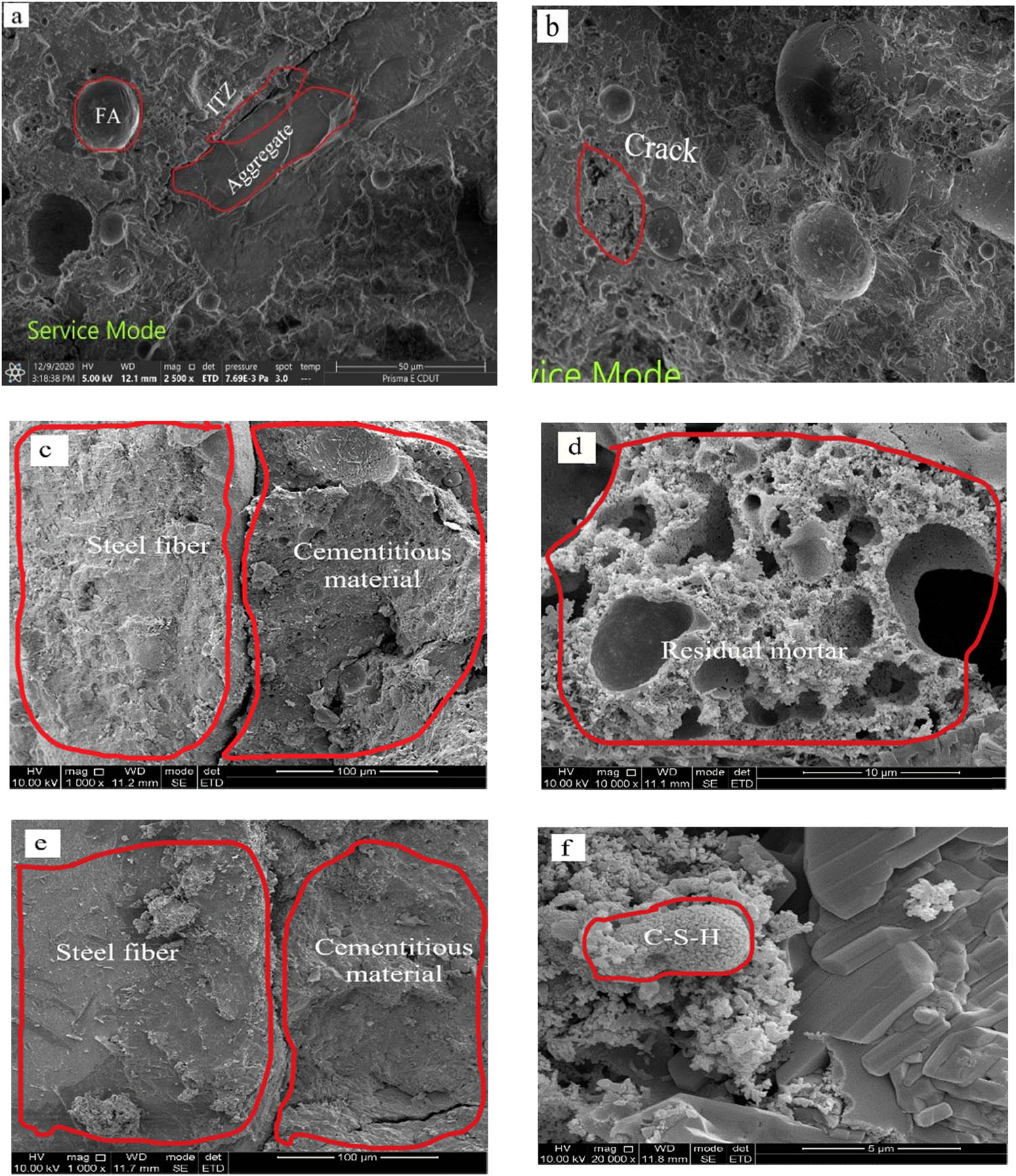

3.2.4 SEM analysis of FRGRAC

In order to facilitate the comparative analysis, test groups M, SF-2.00, and SF-2.50 of 28 days are selected, as shown in Figure 21. Figure 21a and b shows the situation of the M test group, and more unreacted FA particles can be found. This is mainly due to the insufficient polymerization reaction at room temperature during the curing process and many cracks and holes can also be found. Figure 21c and d shows the situation of the SF-2.00 test group. In the figure, it is found that SF is embedded in the matrix and can bear the stress together and play the role of a bridge. However, it is also found that there are gaps between the bonding surface and the cementitious material. At the same time, it can be seen that the residual mortar has a large number of holes and the texture is fluffy. If the content of the residual mortar is high, it will undoubtedly reduce the strength of FRGRAC. Figure 21e and f shows the SF-2.50 test group. It can be found that SF has a tighter bond with the cementitious material. The C–S–H gel is also tightly bound to the aggregate. The polymerization reaction is more complete than the other test groups. This is an intuitive reason for the higher intensity of the test group.

SEM analysis results: (a) M test group interface; (b) micro cracks; (c) bonding between steel fiber and cementitious material in SF-2.0 test group; (d) residual mortar; (e) bonding between steel fiber and cementitious material in SF-2.5 test group; (f) distribution of C–S–H gel.

4 Conclusion

This study has explored the optimum mix proportion of FA–MK geopolymer recycled concrete through orthogonal design. Building on this, the mechanical properties of fiber-reinforced geopolymer-recycled concrete with different SF contents were investigated. Followed by this, the specimens were analyzed by SEM. The main conclusions are as follows.

The mechanical properties of FRGRAC were studied by using SF with FA–MK-based GRAC. The results from the orthogonal test indicate that the order of the factors affecting the 7 days compressive strength of FA–MK-based GRAC is sand ratio < aggregate cementitious material ratio < modulus. When the ratio of water cementitious material is 0.30, the sand ratio is 0.35, and the aggregate cementitious material ratio is 3.50; the 7 days compressive strength of GRAC block with a modulus of 1.00 can reach 34.4 MPa.

As the content of SF increases, the slump continues to decrease and the compressive strength, tensile strength, and flexural strength of FRGRAC have all been improved to a certain extent, and no optimum dosage has been found. When the fiber content is 2.50%, the 7 days compressive strength, tensile strength, and flexural strength are increased by 13.25, 36.36, and 67.2%, respectively, compared with the M group. Compared with the performance of 7 days FRGRAC, SF improves the performance of 28 days FRGRAC more significantly. When the fiber content is 2.50%, the 28 days compressive strength, tensile strength, and flexural strength are increased by 15.72, 64.10, and 60.95%, respectively, compared with those of the M group.

It was found by SEM that the fibers resisted the formation of cracks. Some test groups contained more unreacted FA particles, which were mainly due to the limitation of the curing temperature. The residual mortar has a higher porosity. When the residual mortar content of the test group increased, the strength decreased significantly.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Open Project of Chongqing groundwater Resources Utilization and Environmental Protection Laboratory (DXS20191029), Sichuan Science and Technology Program (2020JDR0266, 2019YFG0460), Chongqing Innovation and Application Development Special General Project (cstc2020jscx-msxmX0084), Sichuan Mingyang Construction Engineering Management Co. Ltd. Special Research Project (MY2021-001).

-

Funding information: This study was supported by the Open Project of Chongqing groundwater Resources Utilization and Environmental Protection Laboratory (DXS20191029), Sichuan Science and Technology Program (2020JDR0266, 2019YFG0460), Chongqing Innovation and Application Development Special General Project (cstc2020jscx-msxmX0084), and Sichuan Mingyang Construction Engineering Management Co., Ltd. Specialized project(MY2021-001).

-

Author contributions: Zhong Xu, Zhenpu Huang, and Changjiang Liu wrote the article. Xiaowei Deng, David Hui, Yuting Deng, Min Zhao, and Libing Qin checked the manuscript.

-

Conflict of interest: One of the co-authors - Prof. David Hui - is an Editor in Chief of Reviews on Advanced Materials Science.

-

Data availability statement: All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article or are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] Navid, R. and M. Z. Zhang. Fiber-reinforced geopolymer composites: A review. Cement and Concrete Composites, Vol. 107, 2020, id. 103498.10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2019.103498Search in Google Scholar

[2] Sun, Y. F., Y. Y. Peng, T. S. Zhou, H. W. Liu, and P. W. Gao. Study of the mechanical-electrical-magnetic properties and the microstructure of three-layered cement-based absorbing boards. Reviews on Advanced Materials Science, Vol. 59, No. 1, 2020, pp. 160–169.10.1515/rams-2020-0014Search in Google Scholar

[3] Liu, C. J., X. C. Huang, Y. Y. Wu, X. W. Deng, and Z. L. Zheng. The effect of graphene oxide on the mechanical properties, impermeability and corrosion resistance of cement mortar containing mineral admixtures. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 288, 2021, id. 123059.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2021.123059Search in Google Scholar

[4] Reiterman, P., O. Holčapek, O. Zobal, and M. Keppert. Freeze-thaw resistance of cement screed with various supplementary cementitious materials. Reviews on Advanced Materials Science, Vol. 58, No. 1, 2019, pp. 66–74.10.1515/rams-2019-0006Search in Google Scholar

[5] Silva, D. P., K. S. Crenstil, and V. Sirivivatnanon. Kinetics of geopolymerization: Role of Al2O3 and SiO2. Cement and Concrete Composites, Vol. 37, No. 4, 2007, pp. 512–518.10.1016/j.cemconres.2007.01.003Search in Google Scholar

[6] He, J., Y. X. Jie, J. H. Zhang, and G. P. Zhang. Synthesis and characterization of red mud and rice husk ash-based geopolymer composites. Cement and Concrete Composites, Vol. 37, 2013, pp. 108–118.10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2012.11.010Search in Google Scholar

[7] Sevinc, A. H. and M. Y. Durgun. Properties of high-calcium fly ash-based geopolymer concretes improved with high-silica sources. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 261, 2020, id. 120014.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.120014Search in Google Scholar

[8] Liu, C. J., X. W. Deng, J. Liu, and D. Hui. Mechanical properties and microstructures of hypergolic and calcined coal gangue based geopolymer recycled concrete. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 221, 2019, pp. 691–708.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2019.06.048Search in Google Scholar

[9] Koushkbaghi, M., P. Alipour, B. Tahmouresi, E. Mohseni, A. Saradar, and P. K. Sarker. Influence of different monomer ratios and recycled concrete aggregate on mechanical properties and durability of geopolymer concretes. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 205, 2019, pp. 519–528.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2019.01.174Search in Google Scholar

[10] Zhu, P. H., M. Q. Hua, H. Liu, X. J. Wang, and C. H. Chen. Interfacial evaluation of geopolymer mortar prepared with recycled geopolymer fine aggregates. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 259, 2020, id. 119849.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.119849Search in Google Scholar

[11] Xu, Z., Z. P. Huang, C. J. Liu, X. W. Deng, and D. Hui. Research progress on mechanical properties of geopolymer recycled aggregate concrete. Reviews on Advanced Materials Science, Vol. 60, 2021, pp. 158–172.10.1515/rams-2021-0021Search in Google Scholar

[12] Tang, Z., W. G. Li, V. W. Y. Tam, and L. B. Yan. Mechanical performance of CFRP-confined sustainable geopolymeric recycled concrete under axial compression. Engineering Structures, Vol. 224, 2020, id. 111246.10.1016/j.engstruct.2020.111246Search in Google Scholar

[13] Khan, M. Z. N., Y. F. Hao, H. Hao, and F. U. A. Shaikh. Mechanical properties of ambient cured high strength hybrid steel and synthetic fibers reinforced geopolymer composites. Cement and Concrete Composites, Vol. 85, 2018, pp. 133–152.10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2017.10.011Search in Google Scholar

[14] Liu, C. J., X. C. Huang, Y. Y. Wu, X. W. Deng, J. Liu, Z. L. Zheng, et al. Review on the research progress of cement-based and geopolymer materials modified by graphene and graphene oxide. Nanotechnology Reviews, Vol. 9, No. 1, 2020, pp. 155–169.10.1515/ntrev-2020-0014Search in Google Scholar

[15] Liu, C. J., X. C. Huang, Y. Y. Wu, X. W. Deng, Z. L. Zheng, Z. Xu, et al. Advance on the dispersion treatment of graphene oxide and the graphene oxide modified cement-based materials. Nanotechnology Reviews, Vol. 10, No. 1, 2021, pp. 34–49.10.1515/ntrev-2021-0003Search in Google Scholar

[16] Saloni, P. and T. M. Pham. Enhanced properties of high-silica rice husk ash-based geopolymer paste by incorporating basalt fibers. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 245, 2020, id. 118422.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.118422Search in Google Scholar

[17] Faris, M. A., M. M. Abdullah, R. Muniandy, M. F. Abu Hashim, K. Błoch, B. Jeż, et al. Comparison of hook and straight steel fibers addition on malaysian fly ash-based geopolymer concrete on the slump, density, water absorption and mechanical properties. Materials, Vol. 14, No. 5, 2021, id. 1310.10.3390/ma14051310Search in Google Scholar

[18] Yang, M. J., P. S. Raj, and Z. J. Gao. Snow-proof roadways using steel fiber-reinforced fly ash geopolymer mortar-concrete. Journal of Materials in Civil Engineering, Vol. 33, No. 2, 2021, id. 04020444.10.1061/(ASCE)MT.1943-5533.0003537Search in Google Scholar

[19] El-Sayed, T. A. and Y. B. I. Shaheen. Flexural performance of recycled wheat straw ash-based geopolymer Rc beams and containing recycled steel fiber. Structures, Vol. 28, 2020, pp. 1713–1728.10.1016/j.istruc.2020.10.013Search in Google Scholar

[20] Qureshi, L. A., B. Ali, and A. Ali. Combined effects of supplementary cementitious materials (silica fume, GGBS, fly ash and rice husk ash) and steel fiber on the hardened properties of recycled aggregate concrete. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 263, 2020, id. 120636.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.120636Search in Google Scholar

[21] Zong, S., Z. Liu, S. Li, Y. Lu, and A. Zheng. Stress-strain behavior of steel-fiber-reinforced recycled aggregate concrete under axial tension. Journal of Cleaner Production, Vol. 278, 2021, id. 123248.10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.123248Search in Google Scholar

[22] Huang, Y. J., J. Z. Xiao, L. Qin, and P. Li. Mechanical behaviors of GFRP tube confined recycled aggregate concrete with sea sand. Advances in Structural Engineering, Vol. 24, No. 6, 2021, pp. 1196–1207.10.1177/1369433220974779Search in Google Scholar

[23] Liu, C. J., X. He, X. W. Deng, Y. Y. Wu, Z. L. Zheng, J. Liu, et al. Application of nanomaterials in ultra-high performance concrete: a review. Nanotechnology Reviews, Vol. 9, No. 12, 2020, pp. 1427–1444.10.1515/ntrev-2020-0107Search in Google Scholar

[24] Etxeberria, M., E. Vazquez, A. Mari, and M. Barra. Influence of amount of recycled coarse aggregates and production process on properties of recycled aggregate concrete. Cement and Concrete Research, Vol. 37, No. 5, 2007, pp. 735–742.10.1016/j.cemconres.2007.02.002Search in Google Scholar

[25] Rao, A., K. Jha, and S. Misra. Use of aggregates from recycled construction and demolition waste in concrete. Resources Conservation and Recycling, Vol. 50, No. 1, 2007, pp. 71–81.10.1016/j.resconrec.2006.05.010Search in Google Scholar

[26] Lu, W. and H. Yuan. A framework for understanding waste management studies in construction. Waste Management, Vol. 31, No. 6, 2011, pp. 1252–1260.10.1016/j.wasman.2011.01.018Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[27] Le, H. B., Q. B. Bui, and L. P. Tang. Geopolymer recycled aggregate concrete: from experiments to empirical models. Materials, Vol. 14, No. 5, 2021, id. 1180.10.3390/ma14051180Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[28] Liang, C., Y. Q. Liu, and Y. Q. Liu. An orthogonal component method for steel girder-concrete abutment connections in integral abutment bridges. Journal of Constructional Steel Research, Vol. 180, 2021, id. 106604.10.1016/j.jcsr.2021.106604Search in Google Scholar

[29] Tang, Z. Experimental study on engineering characteristics of geopolymer recycled concrete road base, Southeast University, Nanjing, 2017 (in Chinese).Search in Google Scholar

[30] Chamila, G., A. Peter, L. Weena, L. David, and S. Sujeeva. Novel analytical method for mix design and performance prediction of high calcium fly ash geopolymer concrete. Polymers, Vol. 13, No. 6, 2021, id. 900.10.3390/polym13060900Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[31] Xie, H. L., H. Fang, W. Cai, L. Wan, and R. L. Huo. Development of an innovative composite sandwich matting with GFRP facesheets and wood core. Reviews on Advanced Materials Science, Vol. 60, No. 1, 2021, pp. 80–91.10.1515/rams-2021-0016Search in Google Scholar

[32] Katinas, E., R. Choteborsky, M. Linda, and J. Kure. Sensitivity analysis of the influence of particle dynamic friction, rolling resistance and volume/shear work ratio on wear loss and friction force using DEM model of dry sand rubber wheel test. Tribology International, Vol. 156, 2021, id. 106853.10.1016/j.triboint.2021.106853Search in Google Scholar

[33] Lian, S. S., T. Meng, H. Q. Song, Z. J. Wang, and J. B. Li. Relationship between percolation mechanism and pore characteristics of recycled permeable bricks based on X-ray computed tomography. Reviews on Advanced Materials Science, Vol. 60, No. 1, 2021, pp. 207–215.10.1515/rams-2021-0022Search in Google Scholar

[34] Zhang, H. Y., S. L. Qi, and L. Cao. Thermal behavior and mechanical properties of geopolymer mortar after exposure to elevated temperatures. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 109, 2015, pp. 17–24.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2016.01.043Search in Google Scholar

[35] Wang, J. J., J. H. Xie, C. H. Wang, J. B. Zhao, F. Liu, and C. Fang. Study on the optimum initial curing condition for fly ash and GGBS based geopolymer recycled aggregate concrete. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 247, 2020, id. 118540.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.118540Search in Google Scholar

[36] Jahangir, A., F. Malik, N. Muhammad, and R. Fayyaz. Reflection phenomena of waves through rotating elastic medium with micro-temperature effect. Reviews on Advanced Materials Science, Vol. 59, No. 1, 2020, pp. 455–463.10.1515/rams-2020-0036Search in Google Scholar

[37] Luan, C. C., Q. Y. Wang, and F. H. Yang. Practical prediction models of tensile strength and reinforcement-concrete bond strength of low-calcium fly ash geopolymer concrete. Polymers, Vol. 13, 2021, id. 875.10.3390/polym13060875Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[38] Ahmad, S. I., H. Hamoudi, A. Abdala, and Z. K. Ghouri. Graphene-reinforced bulk metal matrix composites: synthesis, microstructure, and properties. Reviews on Advanced Materials Science, Vol. 59, No. 1, 2020, pp. 67–114.10.1515/rams-2020-0007Search in Google Scholar

[39] Ganesh, A. C. and M. Muthukannan. Development of high performance sustainable optimized fiber reinforced geopolymer concrete and prediction of compressive strength. Journal of Cleaner Production, Vol. 282, 2021, id. 124543.10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.124543Search in Google Scholar

© 2021 Zhong Xu et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Review Articles

- A review on filler materials for brazing of carbon-carbon composites

- Nanotechnology-based materials as emerging trends for dental applications

- A review on allotropes of carbon and natural filler-reinforced thermomechanical properties of upgraded epoxy hybrid composite

- High-temperature tribological properties of diamond-like carbon films: A review

- A review of current physical techniques for dispersion of cellulose nanomaterials in polymer matrices

- Review on structural damage rehabilitation and performance assessment of asphalt pavements

- Recent development in graphene-reinforced aluminium matrix composite: A review

- Mechanical behaviour of precast prestressed reinforced concrete beam–column joints in elevated station platforms subjected to vertical cyclic loading

- Effect of polythiophene thickness on hybrid sensor sensitivity

- Investigation on the relationship between CT numbers and marble failure under different confining pressures

- Finite element analysis on the bond behavior of steel bar in salt–frost-damaged recycled coarse aggregate concrete

- From passive to active sorting in microfluidics: A review

- Research Articles

- Revealing grain coarsening and detwinning in bimodal Cu under tension

- Mesoporous silica nanoparticles functionalized with folic acid for targeted release Cis-Pt to glioblastoma cells

- Magnetic behavior of Fe-doped of multicomponent bismuth niobate pyrochlore

- Study of surfaces, produced with the use of granite and titanium, for applications with solar thermal collectors

- Magnetic moment centers in titanium dioxide photocatalysts loaded on reduced graphene oxide flakes

- Mechanical model and contact properties of double row slewing ball bearing for wind turbine

- Sandwich panel with in-plane honeycombs in different Poisson's ratio under low to medium impact loads

- Effects of load types and critical molar ratios on strength properties and geopolymerization mechanism

- Nanoparticles in enhancing microwave imaging and microwave Hyperthermia effect for liver cancer treatment

- FEM micromechanical modeling of nanocomposites with carbon nanotubes

- Effect of fiber breakage position on the mechanical performance of unidirectional carbon fiber/epoxy composites

- Removal of cadmium and lead from aqueous solutions using iron phosphate-modified pollen microspheres as adsorbents

- Load identification and fatigue evaluation via wind-induced attitude decoupling of railway catenary

- Residual compression property and response of honeycomb sandwich structures subjected to single and repeated quasi-static indentation

- Experimental and modeling investigations of the behaviors of syntactic foam sandwich panels with lattice webs under crushing loads

- Effect of storage time and temperature on dissolved state of cellulose in TBAH-based solvents and mechanical property of regenerated films

- Thermal analysis of postcured aramid fiber/epoxy composites

- The energy absorption behavior of novel composite sandwich structures reinforced with trapezoidal latticed webs

- Experimental study on square hollow stainless steel tube trusses with three joint types and different brace widths under vertical loads

- Thermally stimulated artificial muscles: Bio-inspired approach to reduce thermal deformation of ball screws based on inner-embedded CFRP

- Abnormal structure and properties of copper–silver bar billet by cold casting

- Dynamic characteristics of tailings dam with geotextile tubes under seismic load

- Study on impact resistance of composite rocket launcher

- Effects of TVSR process on the dimensional stability and residual stress of 7075 aluminum alloy parts

- Dynamics of a rotating hollow FGM beam in the temperature field

- Development and characterization of bioglass incorporated plasma electrolytic oxidation layer on titanium substrate for biomedical application

- Effect of laser-assisted ultrasonic vibration dressing parameters of a cubic boron nitride grinding wheel on grinding force, surface quality, and particle morphology

- Vibration characteristics analysis of composite floating rafts for marine structure based on modal superposition theory

- Trajectory planning of the nursing robot based on the center of gravity for aluminum alloy structure

- Effect of scan speed on grain and microstructural morphology for laser additive manufacturing of 304 stainless steel

- Influence of coupling effects on analytical solutions of functionally graded (FG) spherical shells of revolution

- Improving the precision of micro-EDM for blind holes in titanium alloy by fixed reference axial compensation

- Electrolytic production and characterization of nickel–rhenium alloy coatings

- DC magnetization of titania supported on reduced graphene oxide flakes

- Analytical bond behavior of cold drawn SMA crimped fibers considering embedded length and fiber wave depth

- Structural and hydrogen storage characterization of nanocrystalline magnesium synthesized by ECAP and catalyzed by different nanotube additives

- Mechanical property of octahedron Ti6Al4V fabricated by selective laser melting

- Physical analysis of TiO2 and bentonite nanocomposite as adsorbent materials

- The optimization of friction disc gear-shaping process aiming at residual stress and machining deformation

- Optimization of EI961 steel spheroidization process for subsequent use in additive manufacturing: Effect of plasma treatment on the properties of EI961 powder

- Effect of ultrasonic field on the microstructure and mechanical properties of sand-casting AlSi7Mg0.3 alloy

- Influence of different material parameters on nonlinear vibration of the cylindrical skeleton supported prestressed fabric composite membrane

- Investigations of polyamide nano-composites containing bentonite and organo-modified clays: Mechanical, thermal, structural and processing performances

- Conductive thermoplastic vulcanizates based on carbon black-filled bromo-isobutylene-isoprene rubber (BIIR)/polypropylene (PP)

- Effect of bonding time on the microstructure and mechanical properties of graphite/Cu-bonded joints

- Study on underwater vibro-acoustic characteristics of carbon/glass hybrid composite laminates

- A numerical study on the low-velocity impact behavior of the Twaron® fabric subjected to oblique impact

- Erratum

- Erratum to “Effect of PVA fiber on mechanical properties of fly ash-based geopolymer concrete”

- Topical Issue on Advances in Infrastructure or Construction Materials – Recycled Materials, Wood, and Concrete

- Structural performance of textile reinforced concrete sandwich panels under axial and transverse load

- An overview of bond behavior of recycled coarse aggregate concrete with steel bar

- Development of an innovative composite sandwich matting with GFRP facesheets and wood core

- Relationship between percolation mechanism and pore characteristics of recycled permeable bricks based on X-ray computed tomography

- Feasibility study of cement-stabilized materials using 100% mixed recycled aggregates from perspectives of mechanical properties and microstructure

- Effect of PVA fiber on mechanical properties of fly ash-based geopolymer concrete

- Research on nano-concrete-filled steel tubular columns with end plates after lateral impact

- Dynamic analysis of multilayer-reinforced concrete frame structures based on NewMark-β method

- Experimental study on mechanical properties and microstructures of steel fiber-reinforced fly ash-metakaolin geopolymer-recycled concrete

- Fractal characteristic of recycled aggregate and its influence on physical property of recycled aggregate concrete

- Properties of wood-based composites manufactured from densified beech wood in viscoelastic and plastic region of the force-deflection diagram (FDD)

- Durability of geopolymers and geopolymer concretes: A review

- Research progress on mechanical properties of geopolymer recycled aggregate concrete

Articles in the same Issue

- Review Articles

- A review on filler materials for brazing of carbon-carbon composites

- Nanotechnology-based materials as emerging trends for dental applications

- A review on allotropes of carbon and natural filler-reinforced thermomechanical properties of upgraded epoxy hybrid composite

- High-temperature tribological properties of diamond-like carbon films: A review

- A review of current physical techniques for dispersion of cellulose nanomaterials in polymer matrices

- Review on structural damage rehabilitation and performance assessment of asphalt pavements

- Recent development in graphene-reinforced aluminium matrix composite: A review

- Mechanical behaviour of precast prestressed reinforced concrete beam–column joints in elevated station platforms subjected to vertical cyclic loading

- Effect of polythiophene thickness on hybrid sensor sensitivity

- Investigation on the relationship between CT numbers and marble failure under different confining pressures

- Finite element analysis on the bond behavior of steel bar in salt–frost-damaged recycled coarse aggregate concrete

- From passive to active sorting in microfluidics: A review

- Research Articles

- Revealing grain coarsening and detwinning in bimodal Cu under tension

- Mesoporous silica nanoparticles functionalized with folic acid for targeted release Cis-Pt to glioblastoma cells

- Magnetic behavior of Fe-doped of multicomponent bismuth niobate pyrochlore

- Study of surfaces, produced with the use of granite and titanium, for applications with solar thermal collectors

- Magnetic moment centers in titanium dioxide photocatalysts loaded on reduced graphene oxide flakes

- Mechanical model and contact properties of double row slewing ball bearing for wind turbine

- Sandwich panel with in-plane honeycombs in different Poisson's ratio under low to medium impact loads

- Effects of load types and critical molar ratios on strength properties and geopolymerization mechanism

- Nanoparticles in enhancing microwave imaging and microwave Hyperthermia effect for liver cancer treatment

- FEM micromechanical modeling of nanocomposites with carbon nanotubes

- Effect of fiber breakage position on the mechanical performance of unidirectional carbon fiber/epoxy composites

- Removal of cadmium and lead from aqueous solutions using iron phosphate-modified pollen microspheres as adsorbents

- Load identification and fatigue evaluation via wind-induced attitude decoupling of railway catenary

- Residual compression property and response of honeycomb sandwich structures subjected to single and repeated quasi-static indentation

- Experimental and modeling investigations of the behaviors of syntactic foam sandwich panels with lattice webs under crushing loads

- Effect of storage time and temperature on dissolved state of cellulose in TBAH-based solvents and mechanical property of regenerated films

- Thermal analysis of postcured aramid fiber/epoxy composites

- The energy absorption behavior of novel composite sandwich structures reinforced with trapezoidal latticed webs

- Experimental study on square hollow stainless steel tube trusses with three joint types and different brace widths under vertical loads

- Thermally stimulated artificial muscles: Bio-inspired approach to reduce thermal deformation of ball screws based on inner-embedded CFRP

- Abnormal structure and properties of copper–silver bar billet by cold casting

- Dynamic characteristics of tailings dam with geotextile tubes under seismic load

- Study on impact resistance of composite rocket launcher

- Effects of TVSR process on the dimensional stability and residual stress of 7075 aluminum alloy parts

- Dynamics of a rotating hollow FGM beam in the temperature field

- Development and characterization of bioglass incorporated plasma electrolytic oxidation layer on titanium substrate for biomedical application

- Effect of laser-assisted ultrasonic vibration dressing parameters of a cubic boron nitride grinding wheel on grinding force, surface quality, and particle morphology

- Vibration characteristics analysis of composite floating rafts for marine structure based on modal superposition theory

- Trajectory planning of the nursing robot based on the center of gravity for aluminum alloy structure

- Effect of scan speed on grain and microstructural morphology for laser additive manufacturing of 304 stainless steel

- Influence of coupling effects on analytical solutions of functionally graded (FG) spherical shells of revolution

- Improving the precision of micro-EDM for blind holes in titanium alloy by fixed reference axial compensation

- Electrolytic production and characterization of nickel–rhenium alloy coatings

- DC magnetization of titania supported on reduced graphene oxide flakes

- Analytical bond behavior of cold drawn SMA crimped fibers considering embedded length and fiber wave depth

- Structural and hydrogen storage characterization of nanocrystalline magnesium synthesized by ECAP and catalyzed by different nanotube additives

- Mechanical property of octahedron Ti6Al4V fabricated by selective laser melting

- Physical analysis of TiO2 and bentonite nanocomposite as adsorbent materials

- The optimization of friction disc gear-shaping process aiming at residual stress and machining deformation

- Optimization of EI961 steel spheroidization process for subsequent use in additive manufacturing: Effect of plasma treatment on the properties of EI961 powder

- Effect of ultrasonic field on the microstructure and mechanical properties of sand-casting AlSi7Mg0.3 alloy

- Influence of different material parameters on nonlinear vibration of the cylindrical skeleton supported prestressed fabric composite membrane

- Investigations of polyamide nano-composites containing bentonite and organo-modified clays: Mechanical, thermal, structural and processing performances

- Conductive thermoplastic vulcanizates based on carbon black-filled bromo-isobutylene-isoprene rubber (BIIR)/polypropylene (PP)

- Effect of bonding time on the microstructure and mechanical properties of graphite/Cu-bonded joints

- Study on underwater vibro-acoustic characteristics of carbon/glass hybrid composite laminates

- A numerical study on the low-velocity impact behavior of the Twaron® fabric subjected to oblique impact

- Erratum

- Erratum to “Effect of PVA fiber on mechanical properties of fly ash-based geopolymer concrete”

- Topical Issue on Advances in Infrastructure or Construction Materials – Recycled Materials, Wood, and Concrete

- Structural performance of textile reinforced concrete sandwich panels under axial and transverse load

- An overview of bond behavior of recycled coarse aggregate concrete with steel bar

- Development of an innovative composite sandwich matting with GFRP facesheets and wood core

- Relationship between percolation mechanism and pore characteristics of recycled permeable bricks based on X-ray computed tomography

- Feasibility study of cement-stabilized materials using 100% mixed recycled aggregates from perspectives of mechanical properties and microstructure

- Effect of PVA fiber on mechanical properties of fly ash-based geopolymer concrete

- Research on nano-concrete-filled steel tubular columns with end plates after lateral impact

- Dynamic analysis of multilayer-reinforced concrete frame structures based on NewMark-β method

- Experimental study on mechanical properties and microstructures of steel fiber-reinforced fly ash-metakaolin geopolymer-recycled concrete

- Fractal characteristic of recycled aggregate and its influence on physical property of recycled aggregate concrete

- Properties of wood-based composites manufactured from densified beech wood in viscoelastic and plastic region of the force-deflection diagram (FDD)

- Durability of geopolymers and geopolymer concretes: A review

- Research progress on mechanical properties of geopolymer recycled aggregate concrete