Abstract

The effects of polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) fiber content on mechanical and fracture properties of geopolymer concrete (GPC) were investigated in the present study. Mechanical properties include cubic compressive, prism compressive, tensile and flexural strengths, and elastic modulus. The evaluation indices in fracture properties were measured by using the three-point bending test. Geopolymer was prepared by fly ash, metakaolin, and alkali activator, which was obtained by mixing sodium hydroxide and sodium silicate solutions. The volume fractions of PVA fiber (length 12 mm and diameter 40 μm) were 0, 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, and 1.0%. The results indicate that the effects of the PVA fiber on the cubic and prism compressive strengths and elastic modulus are similar. A tendency of first increasing and then decreasing with the increase in the PVA fiber content was observed in these properties. They all reached a maximum at 0.2% PVA fiber content. There was also a similar tendency of first increase and then decrease for tensile and flexural strengths, peak load, critical effective crack lengths, fracture toughness, and fracture energy of GPC, which were significantly improved by the PVA fiber. They reached a maximum at 0.8% PVA fiber content, except the tensile strength whose maximum was at 1.0% PVA fiber volume fraction. Considering the parameters analyzed, it seems that the 0.8% PVA fiber content provides optimal reinforcement of the mechanical properties of GPC.

1 Introduction

Concrete is widely used in the world because ordinary Portland cement (OPC) as the main binder material has wide sources, simple preparation, and superior mechanical properties. However, the growing demand for concrete results in increased energy consumption and emissions of carbon dioxide to produce a large amount of OPC [1]. The extensive use of OPC is considered one of the main causes of global warming [2], and hence, numerous attempts have been made to find greener alternatives to this material. Professor Davidovits prepared the geopolymer to replace OPC by activating active aluminosilicate materials with high alkali solution. Geopolymer can be produced from industrial wastes and geological sources including fly ash (FA), blast furnace slag, bottom ash, metakaolin (MK), and so on [3,4]. FA-based geopolymer composites have been widely studied because thermal power generation discharges a large amount of FA [5,6,7]. In addition, MK has attracted considerable attention because of its abundant raw materials and satisfactory activity [8]. Although the early strength of the geopolymer with low calcium FA is lower than that of the MK-based geopolymer, the MK-based geopolymer exhibits worse resistance to elevated temperature than FA-based geopolymer [9,10,11,12]. Therefore, to overcome these shortcomings, some researchers have prepared geopolymers by blending MK and FA. Research results showed that MK–FA-based geopolymer exhibited higher compressive and bending strengths and better high-temperature resistance than MK-based or FA-based geopolymer [13,14,15].

Geopolymer concrete (GPC) is environmentally friendly, is energy saving, and also has similar or better mechanical properties than OPC concrete (OPCC) [16]. Compared to OPCC, GPC has better bond strength under similar compressive strength, higher early strength, and faster speed of strength development [17]. Besides, the fire resistance of GPC is much better than the traditional concrete. As a result, GPC can be used in repairing and strengthening of existing structures, such as bridge structures, pavement structures, building structures, and so on, and rapid repaired strength can be obtained. Furthermore, GPC will exhibit better application prospects at some structures in high temperature. Hassan also believes that compared to OPCC, GPC has higher early strength and better durability [18]. The durability of GPC includes freeze–thaw cycle and heat, fire, chloride, sulfate, acid, and efflorescence resistances, which are mainly due to the dense microstructure and migration behavior of GPC [19,20,21]. Bakri et al. reported that the durability of FA-based GPC was better than that of OPC when exposed to acid [22]. GPC can be used as a high-temperature-resistant material because it can still maintain better mechanical properties than OPC at high temperatures [23]. In addition, the drying shrinkage of GPC is much less than that of OPC, so GPC is more suitable for thick concrete layers or concrete members with heavy constraints [18,24]. Although GPC has better durability and mechanical properties, its tensile and flexural properties were similar or even lower than those of OPC [25,26]. Furthermore, the crack resistance and toughness of the GPC are low. As a result, cracks and brittle fracture easily occur in GPC [27,28]. Therefore, to further improve the applicability of GPC, several studies have been conducted to improve its flexural strength and fracture toughness.

The addition of fibers can significantly improve the tensile properties and toughness of concrete. Several researchers have conducted studies on fiber-reinforced concrete, including variations in metal, synthetic, and natural fibers. With the addition of fibers, the tensile strength of concrete can be improved and the length of cracks in concrete can be reduced. As a result, fiber-reinforced concrete exhibits higher ductility and toughness than OPC without fibers [29,30,31,32,33]. Owing to the good mechanical properties, durability, and environmental protective performance of GPC, which is expected to replace silicate cement concrete, several studies evaluated the performance of fiber-reinforced GPC. Diverse types of fibers have been used in geopolymer composites such as carbon, steel, glass, polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), polypropylene, cotton, and natural fibers [34,35,36,37,38,39,40]. From these, PVA fibers have attracted increasing attention in recent years because of their high tensile strength, similar Young’s modulus to concrete, and low price [41,42]. Furthermore, PVA fiber has good resistance to acidity and alkalinity, which are also characteristics of geopolymer [43]. As PVA fibers have a positive effect on the durability of GPC [44], they can be considered suitable for GPC [40]. As reported in the previous studies, PVA fiber also improves the mechanical properties and toughness of geopolymer composites. Ohno and Li investigated the mechanical properties of PVA fiber (length 12 mm and diameter 39 μm) reinforced GPC by cubic compressive and dog-bone tensile testing. The tensile ductility of specimens could be increased by 4%, which is several hundred times that of GPC or OPC without fibers [45]. Nematollahi et al. reported that short PVA fibers with 2% volume content significantly improved the flexural strength of GPC [46]. Xu et al. [47] added two different PVA fiber lengths (12 and 8 mm) into geopolymer composite. The two types of fibers enhanced the compressive, tensile, and flexural strengths of the samples. The toughening effect of the geopolymer composite was remarkable, and the long fiber provided a better performance [47].

Fracture performance is an important aspect of evaluating structural safety [48]. Compared with plastic and brittle materials, it is more difficult to analyze the fracture properties of concrete due to the existence of the fracture process zone in concrete [49]. Various fracture calculation modes were established to evaluate fracture performance of concrete, including fictitious crack model, Griffith model, size effect model, and double-K fracture model. The double-K fracture model is widely used because it accurately describes the process of concrete crack propagation, and its calculation is simpler than other models [50,51]. Fracture toughness and fracture energy as indices of fracture performance are utilized to assess the ability of structures to prevent crack propagation. However, previous researches on PVA fiber-reinforced GPC mainly focused on the basic mechanical properties. There have been few systematic investigations on mechanical properties, including fracture performance. In this study, five groups with different fiber contents and a control group were formed to systematically study the influence of PVA fibers on the mechanical properties including the fracture performance of GPC. The cubic compressive, prism compressive, tensile and flexural strengths, elastic modulus, and fracture performance of GPC were evaluated in this investigation. Besides, the fracture performance was assessed by double-K fracture parameters and fracture energy based on the double-K fracture model, which were measured by the three-point bending method.

2 Experimental investigation

2.1 Materials

In accordance with the specification of FA used for cement and concrete (GB T 1596-2017), grade-one FA procured from Luoyang Power Plant in China was utilized in this study. The chemical composition of the FA is presented in Table 1. MK was provided by Chenxing Industrial Co. Ltd., Shijiazhuang, Hebei Province, China. The main chemical components are SiO2 and Al2O3 (Table 2). Sodium hydroxide (Jinhai Xinwu Fine Chemical Co. Ltd., 99% purity) and sodium silicate (Longxiang Ceramics Co. Ltd., SiO2/Na2O = 3.2) were used as alkaline activators. The molar ratio of silicon oxide to sodium oxide of the activator was 1.3, and the weight ratio of sodium oxide was 16.8%. The liquid polycarboxylic acid superplasticizer (Zhongyi Chemical Co., Ltd., 6–8 of pH, 25–40% of water-reducing rate, and 1.08 of specific gravity) produced by Zhongyi Chemical Co., Ltd. was used to reduce the amount of water and to improve the strength of concrete.

Chemical composition of FA

| Chemical | SiO2 | Al2O3 | Fe2O3 | CaO | MgO | f-CaO | SO3 | Others |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Component (wt%) | 60.98 | 24.47 | 6.70 | 4.90 | 0.68 | 0.58 | 0.52 | 1.17 |

Chemical composition of MK

| Chemical | SiO2 | Al2O3 | Fe2O3 | CaO + MgO | K2O + Na2O |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Component (wt%) | 54 ± 2 | 43 ± 2 | ≤1.3 | ≤0.8 | ≤0.7 |

Coarse aggregates with particle sizes between 5 and 20 mm and river sand with a fineness modulus of 2.7 were used in this study. The properties of the PVA fibers furnished by Kuraray Co. Ltd., Japan, are presented in Table 3.

Properties of PVA fiber

| Diameter (μm) | Length (mm) | Young’s modulus (GPa) | Elongation (%) | Nominal strength (MPa) | Density (kg/m3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 40 | 12 | ≥42 | 6.5 | ≥1,560 | 910 |

2.2 Mix proportions and admixture synthesis

In this study, the mix proportion design of GPC was in accordance with the specification for the mix proportion design of ordinary concrete (JGJ 55-2011). The aim of this article is to study the mechanical properties of GPC with different PVA fiber contents. The control variate method was used, and the dosage of PVA fiber was the only change. Table 4 presents the mix proportions of the PVA fiber-reinforced GPC in this study. As shown in Table 4, the fiber volume fractions were 0, 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, and 1.0%. The usage of PVA fibers in traditional concrete is very popular. However, there is few related research conducted on GPC reinforced with PVA fibers. Referring to the commonly used PVA fiber contents in traditional concrete, the PVA fiber contents of 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, and 1.0% were used in this study. A water/binder ratio of 0.4, an aggregate/binder ratio of 3.0, and a sand/aggregate ratio of 0.35 by weight were used for all specimens. Forty percent of the binder material was FA and 60% was MK because the previous research reported that the addition of MK made FA-based GPC more uniform and compact, and 60% MK content brought the best improvement effect [52].

Mix proportions of fiber-reinforced GPC

| Mixture ID | Fly ash (kg/m3) | Metakaolin (kg/m3) | Alkali activator | River sand (kg/m3) | Coarse aggregate (kg/m3) | PVA fiber (%) | Water reducing admixture (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sodium silicate (kg/m3) | NaOH (kg/m3) | Water (kg/m3) | |||||||

| M | 195.0 | 274.8 | 286.3 | 53.2 | 66.5 | 577.4 | 1072.4 | 0 | 2.00 |

| P1 | 195.0 | 274.8 | 286.3 | 53.2 | 66.5 | 577.4 | 1072.4 | 0.2 | 2.00 |

| P2 | 195.0 | 274.8 | 286.3 | 53.2 | 66.5 | 577.4 | 1072.4 | 0.4 | 2.25 |

| P3 | 195.0 | 274.8 | 286.3 | 53.2 | 66.5 | 577.4 | 1072.4 | 0.6 | 2.50 |

| P4 | 195.0 | 274.8 | 286.3 | 53.2 | 66.5 | 577.4 | 1072.4 | 0.8 | 2.75 |

| P5 | 195.0 | 274.8 | 286.3 | 53.2 | 66.5 | 577.4 | 1072.4 | 1.0 | 3.00 |

Flaky sodium hydroxide was added to the sodium silicate solution to produce an alkali activator solution. The solution was used to activate the aluminosilicate source materials (FA and MK). The mixing process of the PVA fiber-reinforced GPC is shown in Figure 1. Whether the fibers were distributed evenly in the mixture has a significant effect on the properties of hardened GPC. Before the fibers were added, all the fibers were dispersed by hand in advance. During the first stage of mixing, PVA fibers were added into FA and MK in three batches. After the next batch of fibers was added, the stirring direction of the mixer was changed. The added PVA fibers were mixed about 2 min together with FA and MK. From the prepared fresh mixture, it can be found that the fibers were evenly distributed. The mixture was placed into test molds after being evenly stirred. Then, the test molds with the mixtures were vibrated to eliminate air voids and gaps. The specimens were removed after 24 h staying at ambient temperature because the GPC quickly hardened and reached a high compressive value in a short time. Appropriate reduction of curing humidity is beneficial to polymerization [53]. Deng reported that 70–80% humidity was the optimal curing humidity in her experiment [54]. Therefore, samples were placed at ambient temperature and low humidity for 3 days after being cured in a standard curing room for 28 days. In general, GPC can obtain higher strength with high-temperature curing than ambient temperature curing based on the current research results. Considering that the curing temperature of the concrete specimens in the actual construction site is always room temperature, the curing temperature of the specimens in this study was chosen as the standard room temperature to make it consistent with the construction practice.

Preparation process of GPC.

2.3 Cubic compressive strength test

Standard cubic specimens with dimensions of 150 mm × 150 mm × 150 mm were tested following GB/T50081-2002. Three specimens were prepared for each group to ensure the accuracy of the test.

2.4 Prism compressive strength test

The prism size for the prism compressive test was 150 mm × 150 mm × 300 mm. The test was conducted in accordance with GB/T50081-2002. The prism compressive strength is closer to actual engineering practice than the cubic compressive strength. The values measured in this experiment were exploited in the elastic modulus testing.

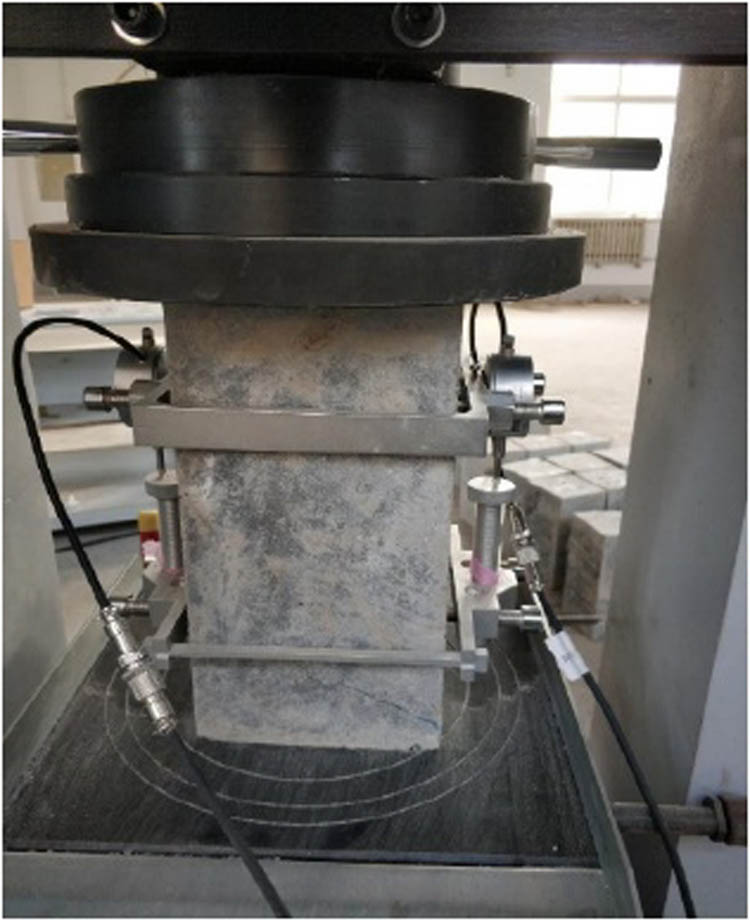

2.5 Elastic modulus test

The size of the specimens used in the elastic modulus test was the same as that in the prism compressive strength test. The test was performed by following GB/T50081-2002, and the test device is shown in Figure 2. Six prisms were prepared for each group to obtain accurate values.

Testing apparatus of elastic modulus test.

2.6 Splitting tensile strength test

The splitting tensile strength of the GPC was measured under the guidance of GB/T50081-2002. Three cubes with a side length of 150 mm were cast for each mix proportion.

2.7 Flexural strength test

Three-point and four-point loading are the main methods of the flexural test, and the schematic diagram of these two loading modes is shown in Figure 3. In the three-point loading test, the failure surface of the specimen usually appears in the middle of the specimen directly below the loading point. While in the four-point loading test, the failure surface of the specimen is located at the weakest position between the two loading points. Since the fibers may not be completely evenly dispersed and the weakest surface of the specimen may not be at the midpoint, the four-point flexural test used in this study can better reflect the flexural resistance of PVA fiber-reinforced GPC compared with the three-point flexural test. Three 100 mm × 100 mm × 400 mm prisms for each mix proportion were cast to test.

Loading diagram of flexural test: (a) three-point flexural test and (b) four-point flexural test.

When the crack on the lower surface is between the two concentrated load action lines, the flexural strength can be calculated by equation (1).

where,

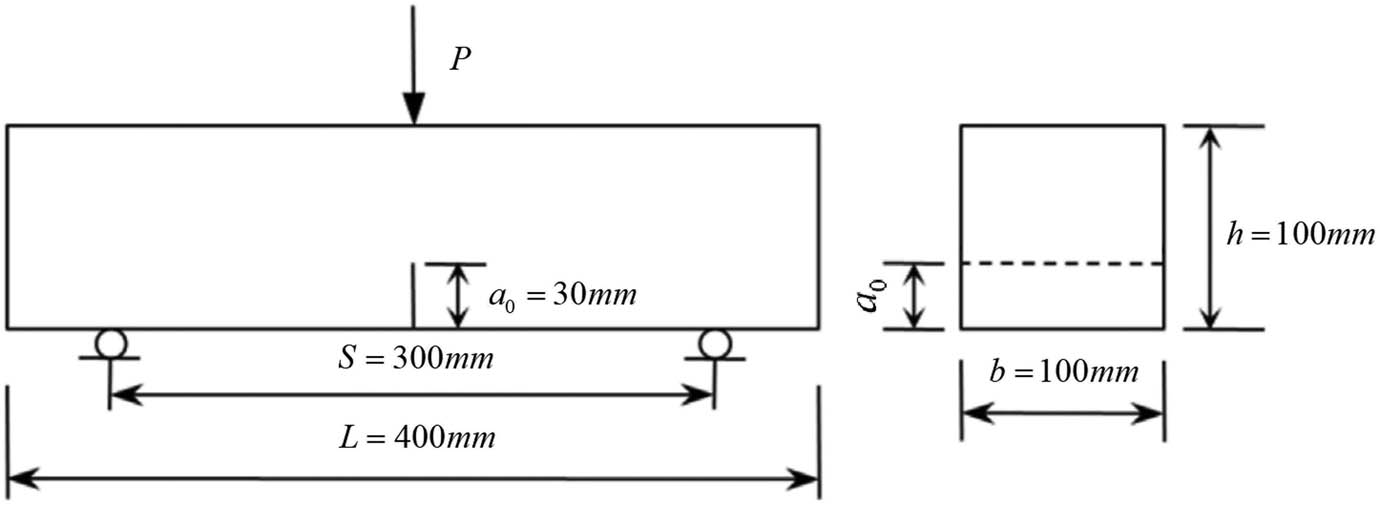

2.8 Fracture properties test

The wedge splitting, direct stretching, compact stretching, and three-point bending methods have been used to measure fracture performance. The three-point bending method is the most commonly used method because of its simple operation and stable test results [39,55,56,57]. Five specimens with dimensions of 100 mm × 100 mm × 400 mm with an initial notch of 30 mm were used according to the current research results for traditional concrete, and the shape of the specimen is shown in Figure 4. The loading device was the same as that in the flexural test. A schematic diagram of the overall test device is presented in Figure 5. The loading pad is a steel plate with a section size of 5 mm × 10 mm × 130 mm. The load acquisition device is a load sensor with the measuring range of 30 kN and an accuracy of 1 N produced by Bengbu Sensor System Engineering Co., LTD. The crack mouth opening displacement (CMOD) of the crack nozzle was measured by a clip gauge with a range of 10 mm and an accuracy of 0.5 mm produced by Beijing Steel Sodium Gram Co., Ltd. The clip gauge is a kind of sensor to measure the developing distance of a crack or the tensile elongation of a specimen, which is based on that the two clamping pieces of the clip gauge can move freely with the change of the distance of a crack or the tensile elongation of a specimen during the test. The changed distance and tensile elongation can be recorded automatically. Two aluminum sheets with a sharp spout were symmetrically sticked close to the edge of the initial crack on the bottom surface of the specimen. The two sharp spouts were direct to the middle of the initial crack. The lamped extender was fixed between the two sharp spouts with the two measuring sheets of the lamped extender contacting the two sharp spouts, respectively. In this study, a DH3818Y static strain tester (Jiangsu Donghua Testing Technology Co., LTD) was adopted. The static strain tester was connected to a load sensor and a clip gage and is used to record data of load and crack opening displacement.

Shape of the specimen.

Loading diagram.

The double-K model was used to analyze the fracture performance of PVA fiber-reinforced GPC, and fracture parameters were calculated by equations (2)–(9) [58]. The load–displacement curve method was utilized to determine the initiation load. The load corresponding to the turning point of the load–displacement curve (Figure 6) from the linear elastic to the nonlinear section is the crack initiation load

where

where

Load–crack opening displacement.

When the external load of the specimen reaches

where

When structural failure occurs, the concrete material is in a state of viscoelastic stress. However, according to the assumption of asymptotic linear elasticity, the fracture toughness of unstability

where

The size effect exists in this study as nonstandard specimens were used. Based on the Weibull brittle failure statistical theory, the approximate conversion between the fracture toughness of standard and nonstandard specimens was conducted using equation (8).

where

The fracture energy can be calculated by equation (9) from the curve of load–CMOD [59].

where

3 Results and discussion

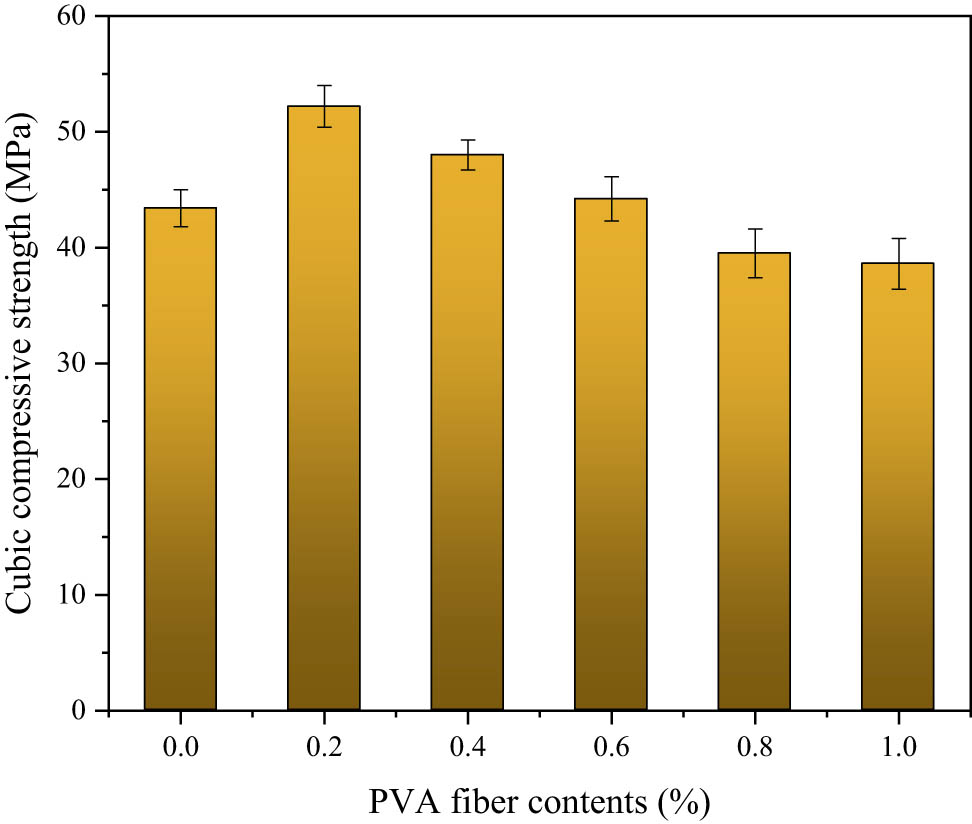

3.1 Compressive strength

As shown in Figure 7, the cubic compressive strength of the GPC was improved by adding PVA fibers from 0.2 to 0.6%, but was reduced with higher volume fractions. The cubic compressive strength of GPC without the PVA fiber was 43.4 MPa, and that of the fiber-reinforced GPC at 0.2% PVA fiber content reached the maximum value of 52.2 MPa. The cubic compressive strength continuously decreased for PVA fiber volume fractions above 0.2%. The strength of the mixture with 0.6% PVA fiber was almost the same as the benchmark strength. When the content of PVA fiber reached its maximum, the cubic compressive strength of GPC reached the minimum value. Previous researches also reported that the cubic compressive strength increased first and then decreased with the increasing PVA fiber content [60,61]. In the study by Yuan et al., 0.3% PVA fiber content achieved the best enhancement of cubic compressive strength of GPC [62]. As for OPC, the maximum cubic compressive strength mostly appeared between 2 and 3% PVA fiber volume fraction [63,64,65,66]. Figure 7 exhibits that the growth rate is higher than the deceleration; thus, the best content for the maximum cubic compressive strength may be a little less than 2% in this study.

Cubic compressive strength versus PVA fiber contents.

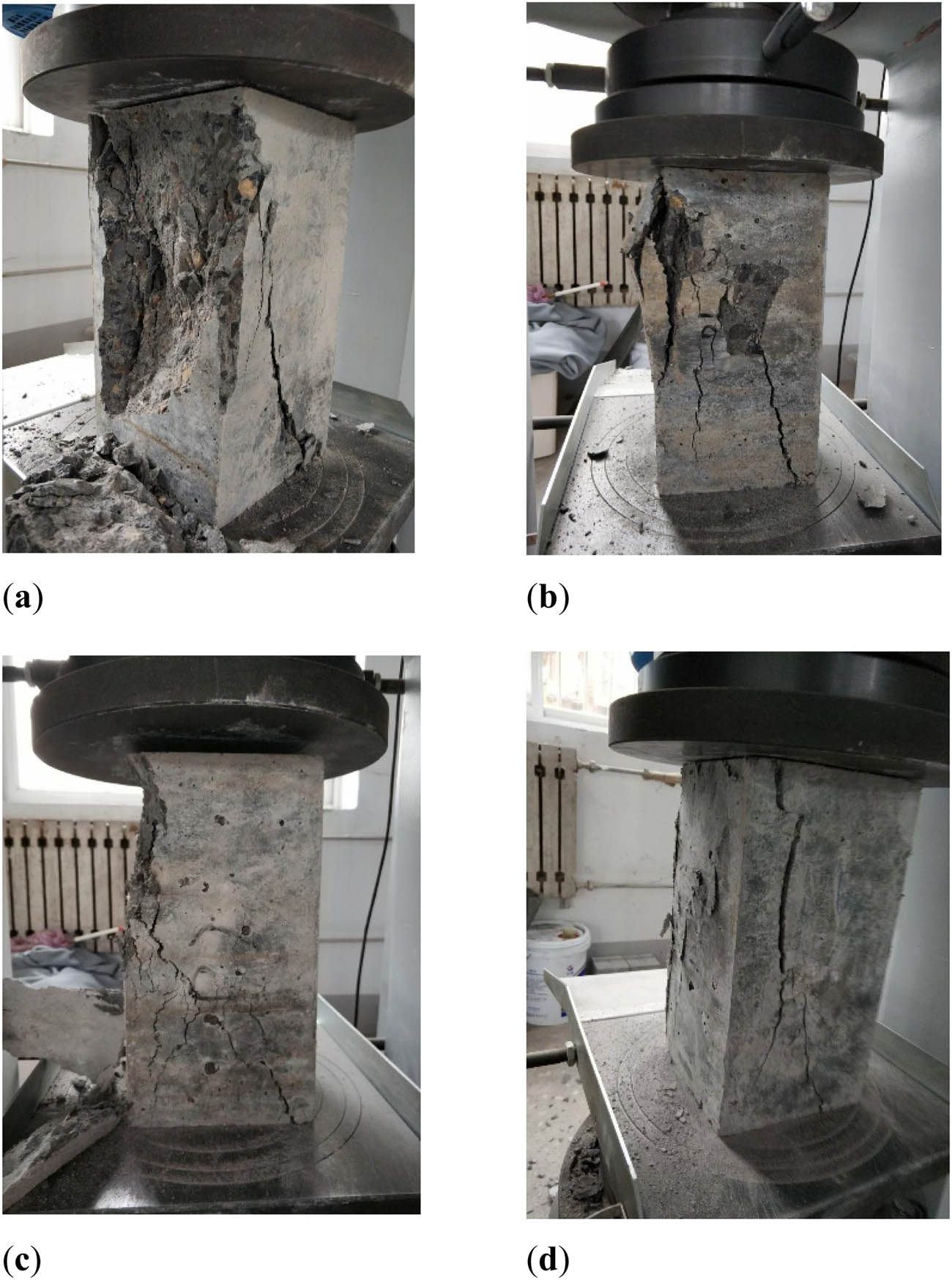

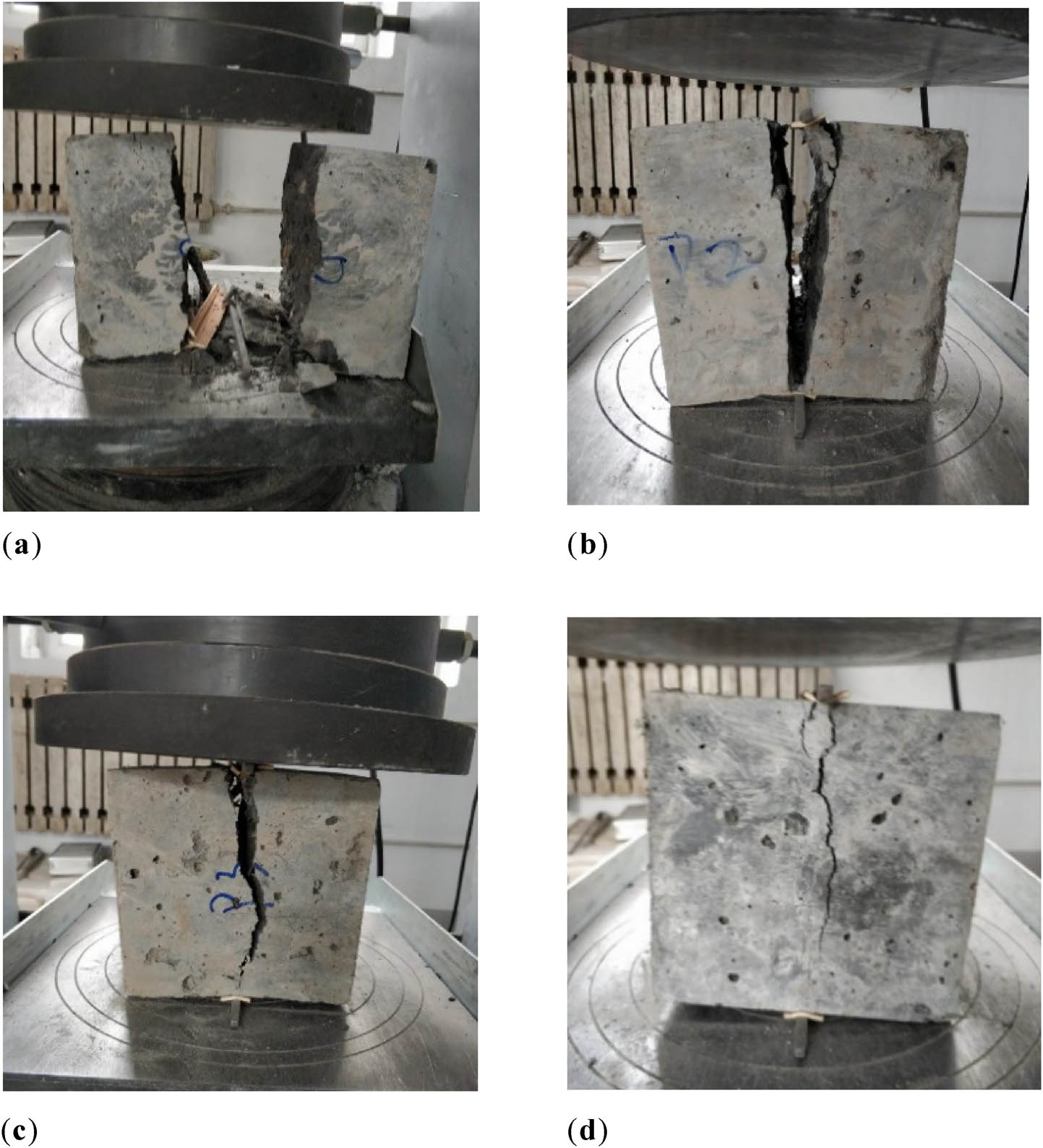

Concrete was improved by adding slight PVA fibers as fibers could bridge cracks, hinder crack propagation, and support loads in the matrix and the microstructure determines the concrete performance. However, excessive fibers were difficult to disperse and tended to agglomerate. Superfluous fibers also caused more voids and flaws into the matrix, which resulted in the stress concentration of the mixture under pressure load and the reduction in the cubic compressive strength [67]. As shown in Figure 7, there is a decreasing tendency from 0.2 to 0.6% fiber contents, but the cubic compressive strength is still higher than the benchmark strength; thus, the influence of fibers on this characteristic of the GPC was positive. However, the improvement provided by fibers cannot compensate for the damage to the matrix when excessive fibers are added. Therefore, in this study, the cubic compressive strength at 0.8 and 1.0% PVA fiber content was lower than that of GPC without PVA fibers. As presented in Figure 8, the addition of PVA fibers significantly delayed the expansion of cracks in the matrix, improved the deformation ability of the mixture, and changed brittle failure to plastic failure. A previous study also showed that fibers did not perform well in improving the strength of concrete. The main function of fibers is to increase the toughness of concrete, control cracks, and absorb energy [68].

Cubic compression failure patterns of specimens. (a) Without PVA fiber, (b) 0.2% PVA fiber, (c) 0.4% PVA fiber, and (d) 1.0% PVA fiber.

As shown in Figure 9, similar to the cubic compressive strength, the prism compressive strength also increased first and then decreases with the increase in the PVA fiber content. The optimal content of PVA fiber for the prism compressive strength was 0.2%. Different failure patterns of specimens with diverse volume fractions are shown in Figure 10. Specimens with fibers at 0, 0.2, and 0.4% exhibited brittle failure and were severely damaged. With high contents of PVA fiber, the specimens exhibited several cracks and one main crack running through the top and bottom. As shown in Figure 8(d), the middle of the specimen was raised, but no peeling phenomenon occurred because the PVA fiber provided a good bridging in the matrix, enabling it to bear some tensile stress around the specimen such that the specimens still had good integrity after failure [69]. Some researchers believe that there are chemical interactions between PVA fibers and the matrix. The formation of hydrogen bonds among molecules due to PVA fibers containing hydroxyl (OH) results in significant changes in the surface bond strength between PVA fibers and the matrix [70]. This is beneficial for highly elastic fibers to bridge matrix materials. However, excessive fibers reduced the prism compressive strength of the GPC due to agglomeration and the introduction of air voids.

Prism compressive strength versus PVA fiber contents.

Prism compression failure patterns of specimens: (a) without PVA fiber, (b) 0.2% PVA fiber content, (c) 0.4% PVA fiber content, and (d) 1.0% PVA fiber content.

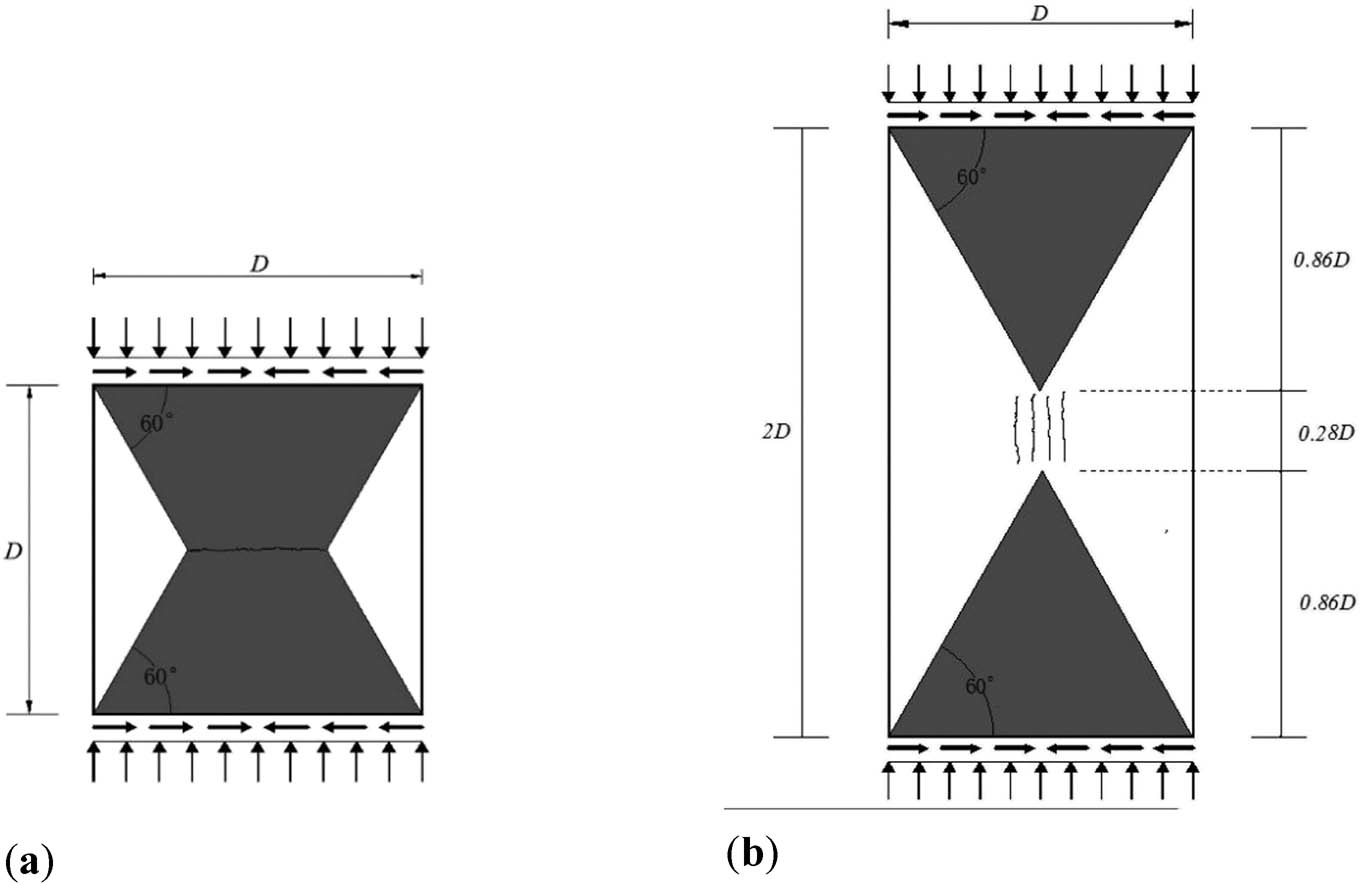

As shown in Figure 11, the prism compressive strength is lower than the cubic compressive strength under the same mix proportion. Under uniaxial compression, the test block was compressed longitudinally and expanded laterally. However, the upper and lower surfaces of the specimen would produce shear force because of the friction between the surfaces of the specimen and the press plate. The shear stress acted as a binding band to prevent lateral displacement [71]. Fotouhi et al. reported that shear stress propagated inward from the surface at 60° [72]. There is no shear stress in some areas in the middle of the specimen, where spalling failure occurred, and it is confirmed in Figure 12. Previous researches have shown that as the height–width ratio of the specimen increased, the influence of shear stress on the middle part of the specimen decreased and then the compressive strength decreased [73]. Therefore, the prism compressive strength in this test is less than the cubic compressive strength.

Cubic and prism compressive strength with different PVA fiber contents.

Stress distribution: (a) cubical specimen and (b) prism specimen.

Previous researches reported that the compressive strength decreased rapidly when the height–width ratio increased from 1 to 2, while changed little from 2 to 4 [74]. Therefore, the prism compressive strength of prisms was closer to the actual strength of compressed structures in practical engineering. Several researchers have found that the cubic compressive strength and prism compression are linear. For OPC, the average of

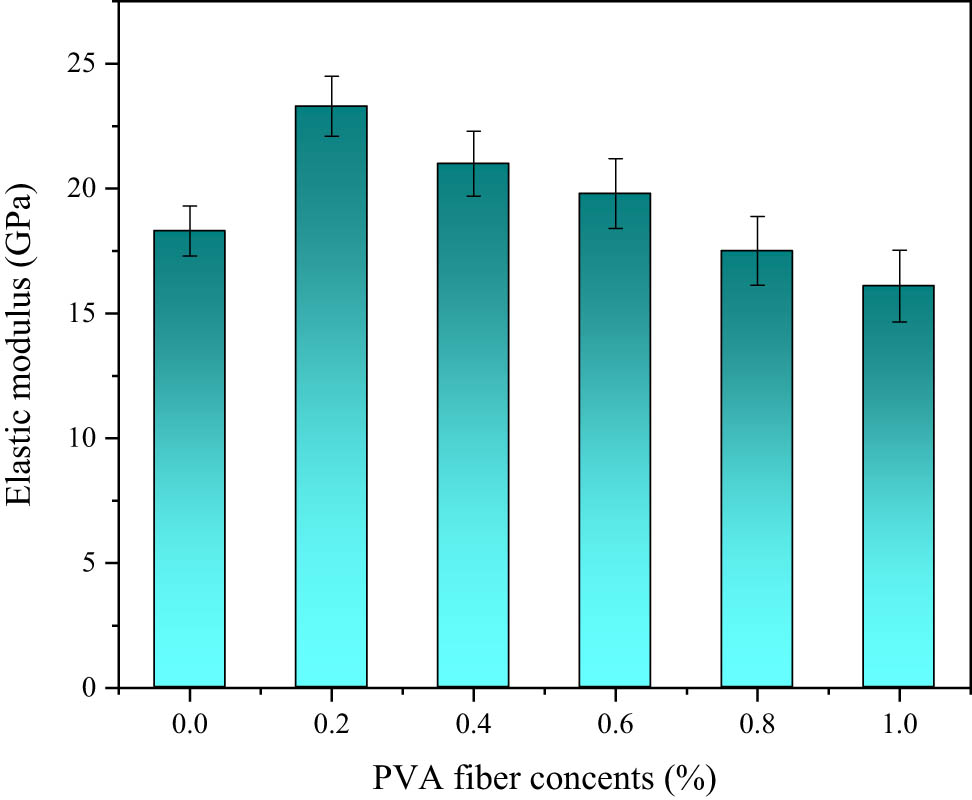

3.2 Elastic modulus

Figure 13 depicts the elastic modulus of PVA fiber-reinforced GPC with different volume fractions. With the increase of PVA fiber content, a tendency of first increase and then decrease of the elastic modulus of GPC can be observed. According to the composite material theory, each component can affect concrete. The PVA fiber has a high elastic modulus and can reduce microcracks in the mixture during hydration. A suitable volume of PVA fiber had a positive influence on the elastic modulus. The relation of elastic modulus and compactness of concrete has been reported [75]. However, PVA fibers also caused tiny air voids into the matrix [76]. In addition, excessively clumping fibers caused an uneven distribution of stress in the GPC. As a result, the PVA fibers had little improvement in the elastic modulus, and high contents had a negative impact. A similar result was also reported for PVA fiber-reinforced high-strength concrete by Nuruddin et al. [77]. The main reason why PVA fiber decreased the elastic modulus of GPC is that the fiber can support much higher compressive and tensile deformation than brittle GPC, and the addition of PVA fibers makes the GPC stressed as a whole. Namely, after incorporated PVA fiber with low elastic modulus, the rigidity of the GPC decreased and the ductility increased, which can keep GPC from damages under large deformation.

Elastic modulus versus PVA fiber contents.

Comparing with OPC, it can be found that when the compressive strength is similar, the elastic modulus of GPC is smaller than that of OPC. The elastic modulus corresponding to the compressive strength of 52.2 is 23.3. Olivia and Nikraz reported that when compressive was from 54.04 to 59.08, the elastic modulus of GPC was from 25.33 to 29.05, which was 14.9–28.8% lower than that of OPC [78]. Moreover, the elastic modulus of geopolymer mortar is lower than that of the ordinary cement mortar. Therefore, the low elastic modulus of geopolymer may be the main reason for the low elastic modulus of GPC [79]. In addition, high-temperature curing is also beneficial to the development of elastic modulus of GPC, so the ambient curing in this study is also a reason for the low elastic modulus [78].

For concrete, there is a relationship between the elastic modulus and the cubic compressive strength. Empirical relationships between these two quantities for OPC have been established by different countries. In the present study, based on the regression analysis, the elastic modulus model of fiber-reinforced GPC is proposed as shown in equation (11). As shown in Figure 14, the correlation between the fitted curve and the test data is good,

where

Elastic modulus versus cubic compressive strength.

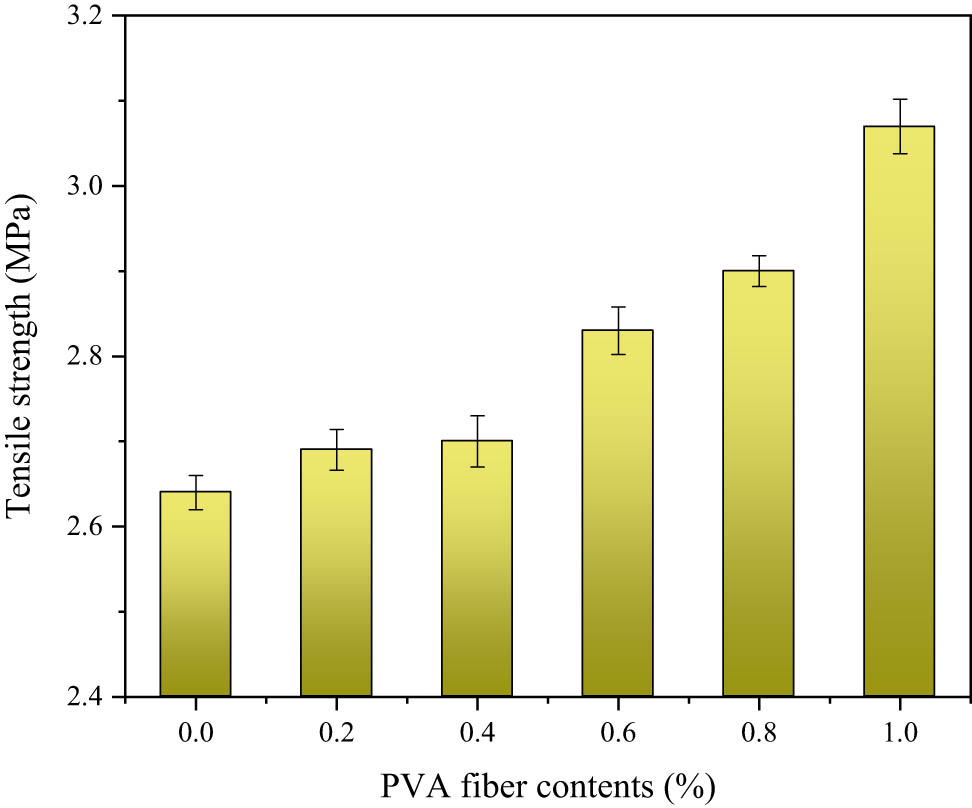

3.3 Tensile strength

As shown in Figure 15, the tensile strength of GPC increases with an increase in the PVA fiber content from 0 to 1.0%. The tensile strength of GPC is 2.64 MPa with no fiber and 3.11 MPa at 1.0% PVA fiber content, which is the maximum value at the highest volume fraction. The increasing tendency of GPC with PVA fibers from 0 to 0.4% is not evident. A similar observation has been reported, in which lower volume fractions of PVA fiber can only produce a slight improvement in the tensile stress resistance of the matrix [77]. Li et al. reported that the bridging effect was more obvious under tension [81]. In this study, it was also confirmed that the tensile performance of PVA fiber-reinforced GPC improved much more than the compression performance. With regard to OPC, PVA fibers also significantly improved the tensile performance of concrete, and the negative effect of fibers will be perceived when the PVA fiber content is high. Wei et al. found that the tensile strength of OPC increased with the PVA fiber content from 0.9 to 1.5% [82]. Khan and Ayub reported that the tensile strength of PVA fiber-reinforced OPC achieved the maximum between 2 and 3% PVA fiber content [83]. Therefore, it is suggested that future studies on the tensile strength of GPC should be carried out in the range of high PVA fiber content, so as to find the optimal PVA fiber volume fraction.

Tensile strength versus PVA fiber contents.

From the tendency shown in Figure 15, it can be predicted that there is a threshold between 0.4 and 0.6%. When the fiber content is less than this dosage, it is difficult to affect the tensile resistance because only a few fibers played a bridging role, which could only limit a small amount of crack expansion. When the fiber content exceeds this dosage, there were more cracks that been limited, which was enough to significantly improve the tensile performance of GPC.

As shown in Figure 16, specimens with PVA fiber contents of less than 0.6% exhibited brittle failure, which could be explained by the fact that only a few nondirectional fibers were distributed in the tensile direction to restrict the development of cracks. When a crack occurred in the matrix, the tensile stress at the crack was completely borne by PVA fibers, and the crack continued to grow where there was no fiber. As the PVA fiber content increases, more fibers are pulled out or broken. Most of the fibers were pulled out because of the high elastic modulus and tensile strength of PVA fibers [84,85]. Moreover, with the increase of PVA fiber content, more fibers played a bridging role, and fibers that were not pulled out or destroyed became more and more. So, the specimen with 1% volume fraction of PVA fiber still maintained good integrity after being destroyed.

Splitting tensile failure patterns of specimens: (a) without PVA fiber, (b) 0.4% PVA fiber content, (c) 0.6% PVA fiber content, and (d) 1.0% PVA fiber content.

3.4 Flexural strength

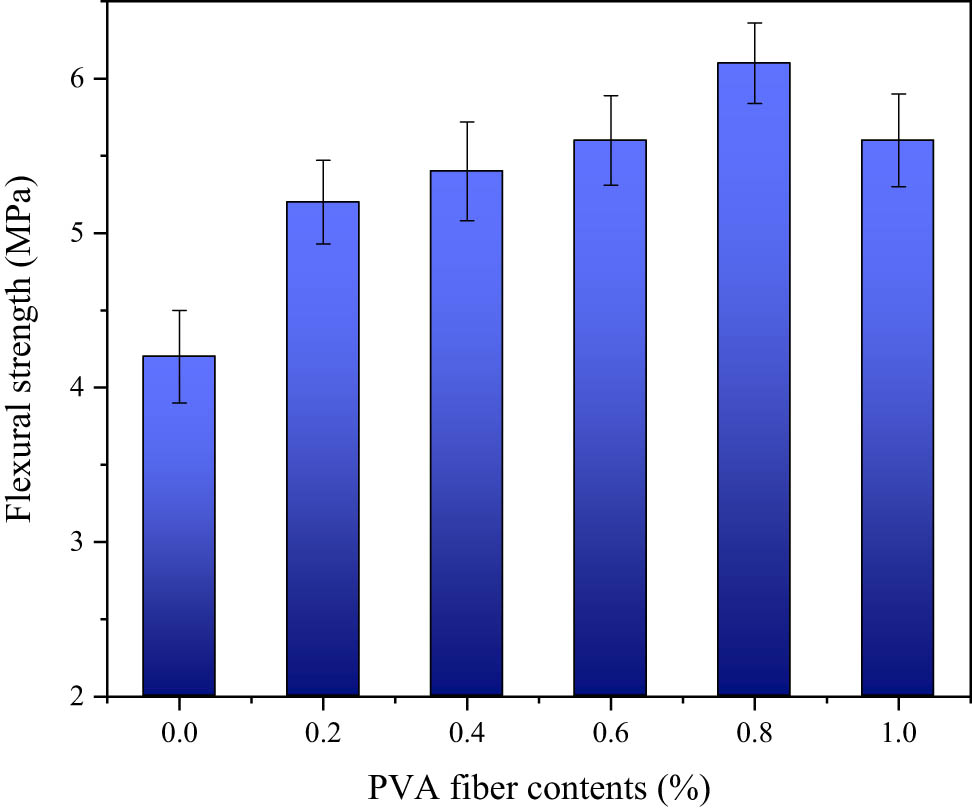

The flexural strengths with different PVA fiber contents are presented in Figure 17. The flexural strengths of GPC at 0 and 0.8% PVA fiber are the minimum and maximum, respectively. The addition of 0.8% PVA fiber content improved the flexural strength of GPC, which was 45% higher than the benchmark flexural strength. The same tendency was reported by Hossain et al. utilizing PVA fibers to reinforce self-consolidating concrete [39]. Due to the different mix ratio and fiber aspect ratio used in this study and in the study by Hossain et al., the optimal mixing amount is different. The flexural strength of the mixture decreases at 1.0% PVA fiber because unevenly dispersed fibers had insufficient bonding with the matrix and could not form an effective bridge. By comparing Figures 15 and 17, it can be found that the optimal PVA fiber contents corresponding to the tensile strength and flexural strength are different. In the tensile test, all the PVA fibers across the damaged section of the specimen are in tension. However, in the flexural test, only the PVA fibers in the tensile region of the beam specimen are in tension, and other fibers are in compression. As shown in Figure 17, 0.2% PVA fiber content significantly improved the resistance to flexure of GPC compared to no fiber added. However, there is basically no promotion in the tensile strength at 0.2% PVA fiber content. A reason speculated is that a high elastic modulus led to a low deflection of the prism [86]. When the PVA fiber content exceeds 0.2% and is less than 0.8%, the flexural strength of the GPC continues to increase while the elastic modulus and cubic compressive strength of the mixtures decrease. Therefore, the flexural strength depends on the tensile strength of the tensile zone located at the lower part of the specimen. With the increase in fiber volume fractions, the bonding and friction between fibers and the matrix bore more tensile stress and restrained more cracks in the concrete [84]. As a result, the flexural strength continued to increase from 0.2 to 0.8% fiber content. The flexural strength of GPC with 1% content PVA fiber is lower than that with 0.8% content, but the tensile strength of GPC with 1% volume fraction of PVA fiber is higher. This indicates that 1% PVA fiber causes agglomeration and introduces defects into the matrix. It also indexes that the flexural resistance of GPC is more sensitive to defects than the tensile resistance, that is, the existence of defects in the matrix has a greater impact on the flexural resistance.

Flexural strength versus PVA fiber contents.

The

Ratios versus PVA fiber contents.

3.5 Fracture properties

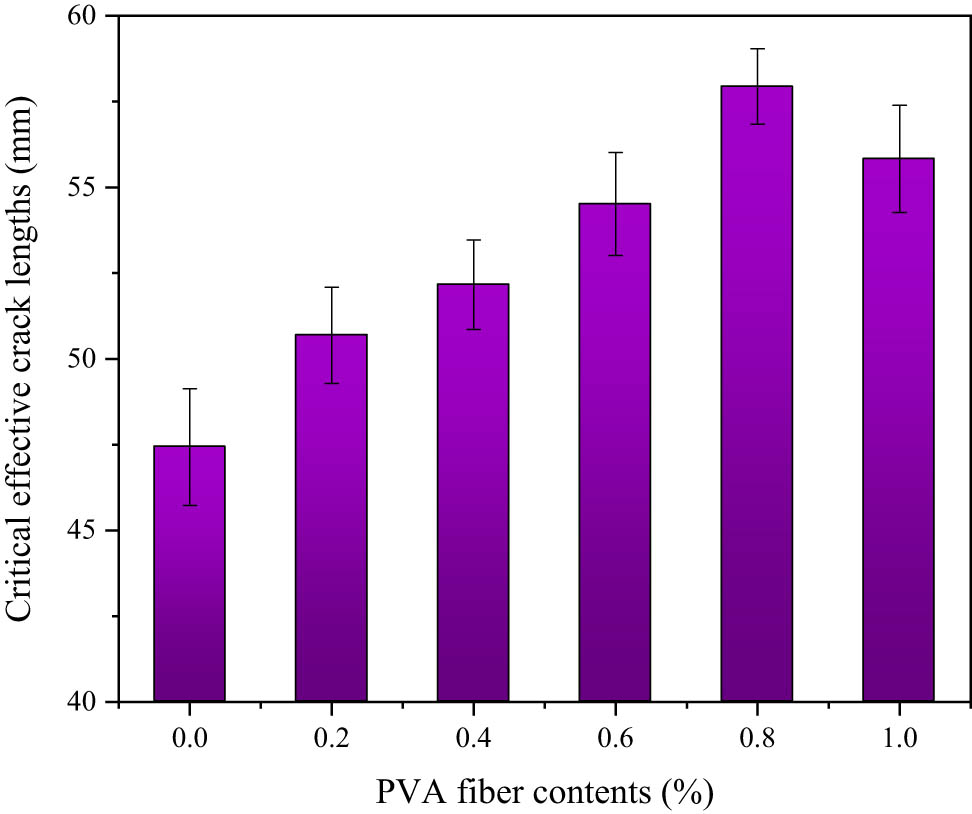

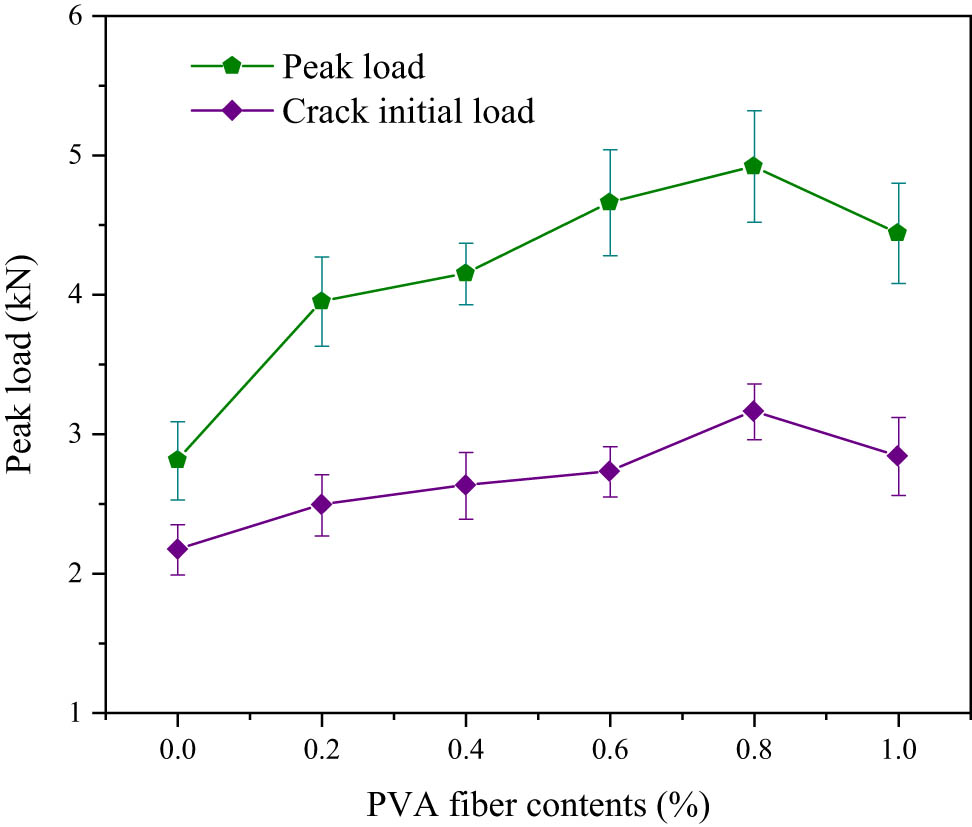

The critical effective crack lengths versus the PVA fiber contents of the GPC are shown in Figure 19, and the crack initial and peak loads of the specimens are presented in Figure 20. It is clear that the PVA fibers improved the crack resistance and load-bearing capacity of GPC. The critical effective crack length increased when the PVA fiber content increased and then slightly decreased at 1.0% PVA fiber volume fraction. As shown in Figure 20, the crack initial and peak loads also increased first and then decreased, but there was a significant decrease at 1.0% volume fraction. In addition, the difference between the peak and crack initial loads increases with the increasing PVA fiber content, which indicates that PVA fibers have a higher influence on the peak load than on the initial crack load of GPC. This indicates that fibers began to work after cracks appeared because the initial load was borne by the GPC matrix, and the load was gradually transferred to the bridged fiber as the deformation increased [87].

Critical effective crack lengths versus PVA fiber contents.

Crack initial and peak loads versus PVA fiber contents.

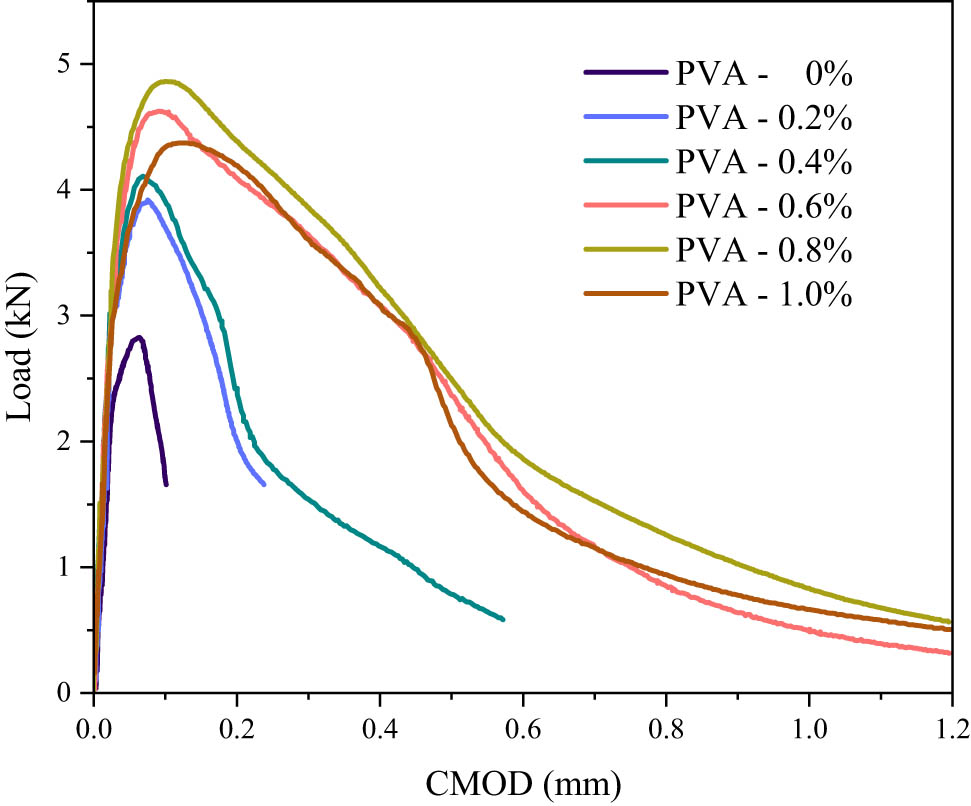

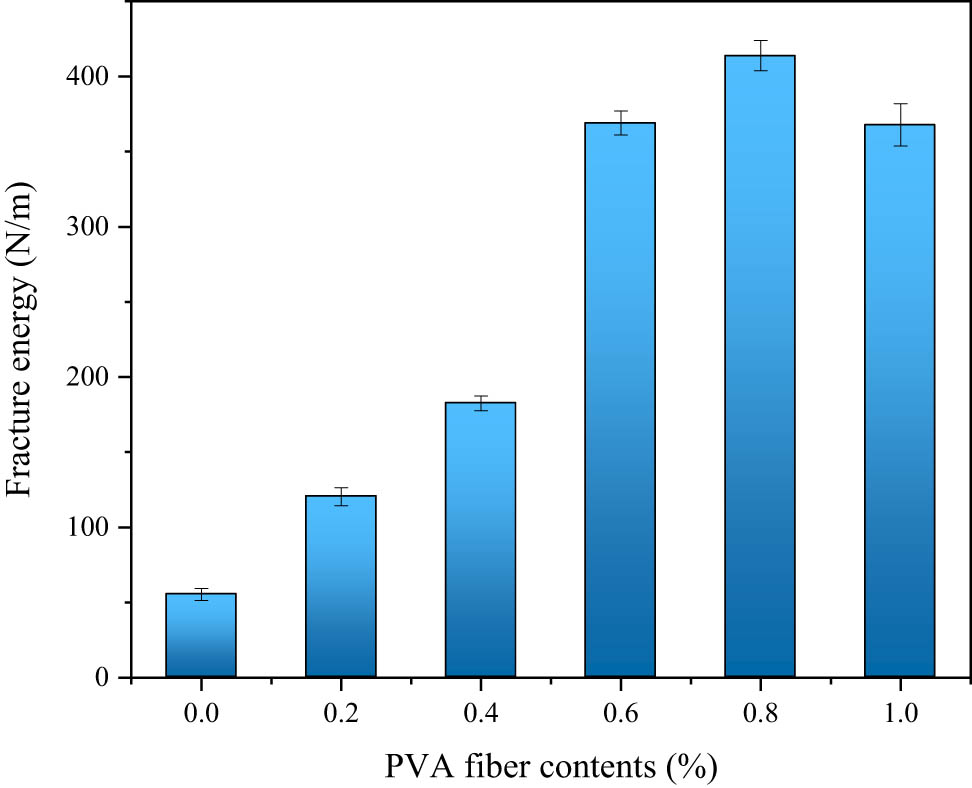

The curves of load–CMOD and fracture energy are presented in Figures 21 and 22, respectively. As shown in Figure 21, 0.6–1.0% fiber content effectively slowed down the post-peak curve and improved the toughness of GPC, but 0.2 and 0.4% PVA fiber content had little effect on the post-peak behavior of GPC. The curve did not continue from 0 to 0.4% PVA fiber contents because specimens ruptured in a brittle fracture. GPC could still bear certain tensile stress after tensile failure with PVA fiber volume fractions higher than or equal to 0.6%. The envelop area under the load–CMOD curve was larger with a higher content of PVA fiber, and with the increase of PVA fiber volume fraction, the fracture energy increased correspondingly, as shown in Figure 22. The fracture energy of the PVA fiber-reinforced GPC was considerably higher than that without the PVA fiber. In other studies, fibers also significantly improved the fracture energy of GPC by 5 to 10 times [88,89]. As shown in Figure 22, the fracture energy significantly increased when the PVA fiber content was 0.4 to 0.6%. This phenomenon also appeared in PVA fiber-reinforced OPC. However, in Hossain’s investigation, the fracture energy of OPC significantly increased with the PVA fiber content from 0.2 to 0.3% [90]. The changing trend of fracture energy with fiber contents is similar to the trends of tensile strength and flexure strength, which both reached the maximum at 0.8% content because the improvement of these properties was benefited from fiber bridging. It has been pointed out that there are mainly three kinds of interaction between fibers and matrix: bonding, friction, and mechanical occlusion [87]. As for the PVA fiber, there are mainly adhesion and friction between fibers and GPC. As the fibers were added, more energy was required to break the bond between fibers and the matrix and then pull the fibers out or to rupture fibers apart. However, when the PVA fiber content was too high, the negative effect brought by the fiber agglomeration and the stomata introduced by PVA fibers would be more obvious, so there was a decrease when the PVA fiber content is 1.0% [89].

Load–CMOD curve.

Fracture energy versus PVA fiber contents.

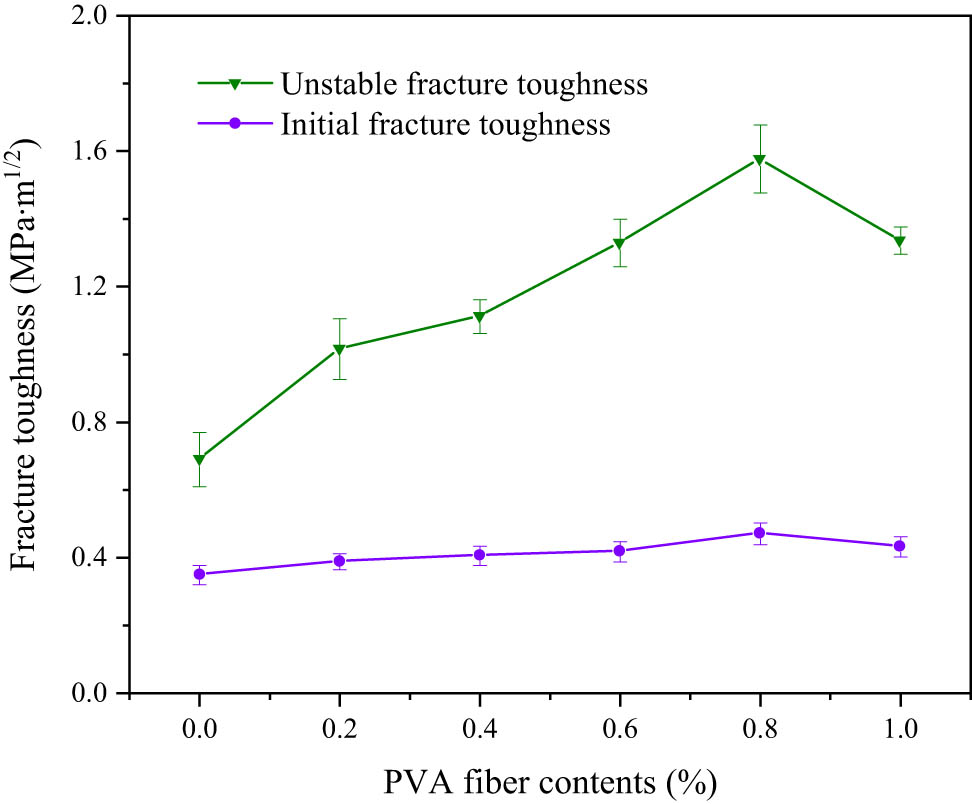

Figure 23 presents initial and unstable fracture toughness varied with different contents of PVA fiber. Although the two tendencies are similar, the increase and decrease range of unstable fracture toughness are considerably larger than that of the initial fracture toughness. The influence of PVA fiber on initial fracture toughness is not significant, but the improvement of unstable fracture toughness is significant. Previous studies by us and others have also shown that the influence of fibers on the instability fracture toughness of concrete is much greater than the fracture toughness of initiation, whether PVA fiber or basalt fiber [59,91,92]. As the initial crack load was quickly reached, peak load was reached with a small value of CMOD. Stress at the crack tip rapidly developed because of the initial damage inside the concrete. In contrast, although fibers reduced some cracks and enhanced internal adhesion, they also introduced small air voids into the GPC, which had a negative effect. When microcracks occurred, PVA fibers hardly reached the stress state and helped the matrix to resist tensile stress because they were erratically distributed. Therefore, the PVA fiber had little influence on initial fracture toughness of GPC. The bridging action of fibers clearly improved the toughness of concrete when the cracks stably expanded [91]. The adhesion and friction between fibers and matrix considerably improve the tolerance of tensile stress. As a result, with the increase of the PVA fiber content from 0 to 0.8%, the unstable fracture toughness of GPC continuously increased. The fracture toughness of initiation and instability of concrete decreased at 1.0% content of PVA fiber as presented in Figure 23. One of the reasons may be that excessive PVA fibers increased the amount of agglomerates and brought air voids, which decreased the compactness of specimens and increased the initial defect of concrete [93]. In addition, comparing the flexural resistance and fracture performance of GPC with different contents of PVA fiber, the same tendency can be found between them; thus, the flexural strength can also reflect the fracture performance.

Fracture toughness versus PVA fiber contents.

4 Conclusion

The effect of the PVA fiber on the cubic and prism compressive strengths, elastic modulus, tensile and flexural strengths, and fracture performance of GPC was investigated in this study. The following conclusions can be drawn:

A tendency of increasing first and then declining was found in the elastic modulus and cubic and prism compressive strengths. The addition of 0.2% PVA fiber content provided the best enhancement of the above properties, increasing the cubic and prism compressive strengths and elastic modulus by 20.3, 16.7, and 27.4%, respectively. Other contents of PVA fiber had little influence on GPC.

PVA fibers significantly enhanced the tensile and flexural strengths of GPC. With the increasing content of PVA fiber, there was a continuous increase in the tensile strength, whereas an initial increase and decrease later were observed in the flexural strength. The tensile strength of GPC was maximally improved by 17.8 at 1.0% PVA fiber content, and the flexural strength of the GPC was enhanced by 45% at a PVA fiber content of 0.8%.

The critical effective crack length, initial crack load, peak load, initial fracture toughness, unstable fracture toughness. and fracture energy of the PVA fiber-reinforced GPC first increased and then decreased with an increase in the PVA fiber volume fraction. These parameters reached maximum values at 0.8% PVA fiber content. The unstable fracture toughness and fracture energy were significantly improved. At 0.8% PVA fiber volume fraction, the fracture energy and unstable fracture toughness were enhanced by 1284.2 and 128.6%, respectively.

The volume fraction of 0.8% was suggested to get optimal tensile properties and toughness while ensuring the compressive performance of concrete.

-

Funding information: National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 51979251, U2040224), Natural Science Foundation of Henan (Grant No. 212300410018), and Program for Innovative Research Team (in Science and Technology) in University of Henan Province of China (Grant No. 20IRTSTHN009).

-

Author contributions: Peng Zhang: funding acquisition, investigation, formal analysis, data Cu-ratio, writing – original draft; Xu Han: methodology, resources, supervision, validation, writing – original draft; Yuanxun Zheng: conceptualization, investigation, supervision, resources, project administration, writing – review & editing; jinyi wan: validation, investigation, methodology; David Hui: writing – review & editing.

-

Conflict of interest: One of the co-authors (Prof. David Hui) is an Editor in Chief of Reviews on Advanced Materials Science.

References

[1] Kastiukas, G., X. Zhou, and J. Castro-Gomes. Preparation conditions for the synthesis of alkali-activated binders using tungsten mining waste. Journal of Materials in Civil Engineering, Vol. 29, No. 10, 2017, id. 04017181.10.1061/(ASCE)MT.1943-5533.0002029Search in Google Scholar

[2] Rodrigues, F. A. and I. Joekes. Cement industry: Sustainability, challenges and perspectives. Environmental Chemistry Letters, Vol. 9, No. 2, 2011, pp. 151–166.10.1007/s10311-010-0302-2Search in Google Scholar

[3] Davidovits, J. Geopolymers-and-geopolymeric-materials. Journal of Thermal Analysis, Vol. 35, No. 2, 1989, pp. 429–441.10.1007/BF01904446Search in Google Scholar

[4] Chu, Y. S., B. Davaabal, D. S. Kim, S. K. Seo, Y. Kim, C. Ruescher, et al. Reactivity of fly ashes milled in different milling devices. Reviews on Advanced Materials Science, Vol. 58, 2019, pp. 179–188.10.1515/rams-2019-0028Search in Google Scholar

[5] Wong, C. L., K. H. Mo, U. J. Alengaram, and S. P. Yap. Mechanical strength and permeation properties of high calcium fly ash-based geopolymer containing recycled brick powder. Journal of Building Engineering, Vol. 32, 2020, id. 101655.10.1016/j.jobe.2020.101655Search in Google Scholar

[6] Wang, L., M. M. Jin, F. X. Guo, Y. Wang, and S. W. Tang. Pore structural and fractal analysis of the influence of fly ash and silica fume on the mechanical property and abrasion resistance of concrete. Fractals, Vol. 22, No. 9, 2021, id. 2140003.10.1142/S0218348X2140003XSearch in Google Scholar

[7] Zhang, P., Z. Gao, J. Wang, J. Guo, S. Hu, and Y. Ling. Properties of fresh and hardened fly ash/slag based geopolymer concrete: A review. Journal of Cleaner Production, Vol. 270, 2020, id. 122389.10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.122389Search in Google Scholar

[8] Billong, N., J. Kinuthia, J. Oti, and U. C. Melo. Performance of sodium silicate free geopolymers from metakaolin (MK) and Rice Husk Ash (RHA): Effect on tensile strength and microstructure. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 189, 2018, pp. 307–313.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2018.09.001Search in Google Scholar

[9] Brown, T. J., K. K. Sagoe-Crentsil, and A. H. Taylor. Comparative assessment of medium-term properties and performance of fly ash and metakaolin geopolymer systems. Journal of the Australian Ceramic Society, Vol. 43, No. 2, 2007, pp. 131–137.Search in Google Scholar

[10] Rashad, A. M. and S. R. Zeedan. The effect of activator concentration on the residual strength of alkali-activated fly ash pastes subjected to thermal load. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 25, No. 7, 2011, pp. 3098–3107.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2010.12.044Search in Google Scholar

[11] Bernal, S. A., E. D. Rodríguez, R. Mejía de Gutiérrez, M. Gordillo, and J. L. Provis. Mechanical and thermal characterisation of geopolymers based on silicate-activated metakaolin/slag blends. Journal of Materials Science, Vol. 46, No. 16, 2011, pp. 5477–5486.10.1007/s10853-011-5490-zSearch in Google Scholar

[12] Golewski, G. L. The beneficial effect of the addition of fly ash on reduction of the size of microcracks in the ITZ of concrete composites under dynamic loading. Energies, Vol. 14, No. 3, 2021, id. 668.10.3390/en14030668Search in Google Scholar

[13] Zhang, H. Y., V. Kodur, B. Wu, L. Cao, and S. L. Qi. Comparative thermal and mechanical performance of geopolymers derived from metakaolin and fly ash. Journal of Materials in Civil Engineering, Vol. 28, No. 2, 2016, id. 04015092.10.1061/(ASCE)MT.1943-5533.0001359Search in Google Scholar

[14] Luan, C., X. Shi, K. Zhang, N. Utashev, F. Yang, J. X. Dai, et al. A mix design method of fly ash geopolymer concrete based on factors analysis. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 272, 2021, pp. 121–612.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.121612Search in Google Scholar

[15] Fernández-Jiménez, A., M. Monzó, M. Vicent, A. Barba, and A. Palomo. Alkaline activation of metakaolin–fly ash mixtures: Obtain of Zeoceramics and Zeocements. Microporous and Mesoporous Materials, Vol. 108, No. 1–3, 2008, pp. 41–49.10.1016/j.micromeso.2007.03.024Search in Google Scholar

[16] Ramujee, K. and M. PothaRaju. Mechanical properties of geopolymer concrete composites. Materials Today Proceedings, Vol. 4, No. 2, 2017, pp. 2937–2945.10.1016/j.matpr.2017.02.175Search in Google Scholar

[17] Castel, A. and S. J. Foster. Bond strength between blended slag and Class F fly ash geopolymer concrete with steel reinforcement. Cement and Concrete Research, Vol. 72, 2015, pp. 48–53.10.1016/j.cemconres.2015.02.016Search in Google Scholar

[18] Hassan, A., M. Arif, and M. Shariq. A review of properties and behaviour of reinforced geopolymer concrete structural elements – A clean technology option for sustainable development. Journal of Cleaner Production, Vol. 245, 2020, id. 118762.10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.118762Search in Google Scholar

[19] Zhuang, X. Y., L. Chen, S. Komarneni, C. H. Zhou, D. S. Tong, H. M. Yang, et al. Fly ash-based geopolymer: Clean production, properties and applications. Journal of Cleaner Production, Vol. 125, 2016, pp. 253–276.10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.03.019Search in Google Scholar

[20] Zhang, Z., X. Yao, and H. Zhu. Potential application of geopolymers as protection coatings for marine concreteII. Microstructure and anticorrosion mechanism. Applied Clay Science, Vol. 49, No. 1–2, 2010, pp. 7–12.10.1016/j.clay.2010.04.024Search in Google Scholar

[21] Reiterman, P., O. Holčapek, O. Zobal, and M. Keppert. Freeze-thaw resistance of cement screed with various supplementary cementitious materials. Reviews on Advanced Materials Science, Vol. 58, No. 2019, 2019, pp. 66–74.10.1515/rams-2019-0006Search in Google Scholar

[22] Bakri, A. M. M. A., H. Kamarudin, M. Bnhussain, I. K. Nizar, A. R. Rafiza, and Y. Zarina. The processing, characterization, and properties of fly ash based geopolymer concrete. Reviews on Advanced Materials Science, Vol. 30, 2012, pp. 90–97.Search in Google Scholar

[23] Hussin, M. W., M. A. R. Bhutta, M. Azreen, P. J. Ramadhansyah, and J. Mirza. Performance of blended ash geopolymer concrete at elevated temperatures. Materials and Structures, Vol. 48, No. 3, 2014, pp. 709–720.10.1617/s11527-014-0251-5Search in Google Scholar

[24] Aldred, J. and J. Day. Is geopolymer concrete a suitable Alternative to traditional concrete. 37th Conference on Our World in Concrete & Structures, Singapore Concrete Institute, Singapore, 2012.Search in Google Scholar

[25] Farhan, N. A., M. N. Sheikh, and M. N. S. Hadi. Investigation of engineering properties of normal and high strength fly ash based geopolymer and alkali-activated slag concrete compared to ordinary Portland cement concrete. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 196, 2019, pp. 26–42.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2018.11.083Search in Google Scholar

[26] Nath, P. and P. K. Sarker. Flexural strength and elastic modulus of ambient-cured blended low-calcium fly ash geopolymer concrete. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 130, 2017, pp. 22–31.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2016.11.034Search in Google Scholar

[27] Ding, Y., C. J. Shi, and N. Li. Fracture properties of slag/fly ash-based geopolymer concrete cured in ambient temperature. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 190, 2018, pp. 787–795.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2018.09.138Search in Google Scholar

[28] Hamidi, F., F. Aslani, and A. Valizadeh. Compressive and tensile strength fracture models for heavyweight geopolymer concrete. Engineering Fracture Mechanics, Vol. 231, 2020, id. 107023.10.1016/j.engfracmech.2020.107023Search in Google Scholar

[29] Wang, L., T. He, Y. Zhou, S. Tang, J. Tan, Z. T. Liu, et al. The influence of fiber type and length on the cracking resistance, durability and pore structure of face slab concrete. Construction and building materials, Vol. 282, 2021, id. 122706.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2021.122706Search in Google Scholar

[30] Qin, Y., X. W. Zhang, J. R. Chai, Z. G. Xu, and S. Y. Li. Experimental study of compressive behavior of polypropylene-fiber-reinforced and polypropylene-fiber-fabric-reinforced concrete. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 194, 2019, pp. 216–225.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2018.11.042Search in Google Scholar

[31] Wang, L., F. X. Guo, H. M. Yang, Y. Wang, and S. W. Tang. Comparison of fly ash, PVA fiber, MgO and shrinkage-reducing admixture on the frost resistance of face slab concrete via pore structural and fractal analysis. Fractals, Vol. 29, 2020, id. 2140002. 10.1142/S0218348X21400028.Search in Google Scholar

[32] Sun, Y., Y. Peng, T. Zhou, H. Liu, and P. Gao. Study of the mechanical-electrical-magnetic properties and the microstructure of three-layered cement-based absorbing boards. Reviews on Advanced Materials Science, Vol. 59, No. 1, 2020, pp. 160–169.10.1515/rams-2020-0014Search in Google Scholar

[33] Nakonieczny, D. S., M. Antonowicz, and Z. Paszenda. Surface modification methods of ceramic filler in ceramic-carbon fibre composites for bioengineering applications – a systematic review. Reviews on Advanced Materials Science, Vol. 59, 2020, pp. 1–19.10.1515/rams-2020-0024Search in Google Scholar

[34] Qin, Y., M. Li, Y. Li, W. Ma, Z. Xu, J. R. Chai, et al. Effects of nylon fiber and nylon fiber fabric on the permeability of cracked concrete. Construction and building materials, Vol. 274, 2021, id. 121786.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.121786Search in Google Scholar

[35] Lin, T., D. Jia, P. He, and M. Wang. In situ crack growth observation and fracture behavior of short carbon fiber reinforced geopolymer matrix composites. Materials Science and Engineering: A, Vol. 527, No. 9, 2010, pp. 2402–2407.10.1016/j.msea.2009.12.004Search in Google Scholar

[36] Krahl, P. A., G. D. S. Gidrao, R. B. Neto, and R. Carrazedo. Effect of curing age on pullout behavior of aligned and inclined steel fibers embedded in UHPFRC. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 266, 2021, id. 121188.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.121188Search in Google Scholar

[37] Das, S., M. Habibur Rahman Sobuz, V. W. Y. Tam, A. S. M. Akid, N. M. Sutan, and F. M. M. Rahman. Effects of incorporating hybrid fibres on rheological and mechanical properties of fibre reinforced concrete. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 262, 2020, id. 120561.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.120561Search in Google Scholar

[38] Qin, Y., X. W. Zhang, and J. R. Chai. Damage performance and compressive behavior of early-age green concrete with recycled nylon fiber fabric under an axial load. Construction and building materials, Vol. 209, 2019, pp. 105–114.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2019.03.094Search in Google Scholar

[39] Hossain, K. M. A., M. Lachemi, M. Sammour, and M. Sonebi. Strength and fracture energy characteristics of self-consolidating concrete incorporating polyvinyl alcohol, steel and hybrid fibres. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 45, 2013, pp. 20–29.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2013.03.054Search in Google Scholar

[40] Rashad, A. M. The effect of polypropylene, polyvinyl-alcohol, carbon and glass fibres on geopolymers properties. Materials Science & Technology, Vol. 35, No. 2, 2018, pp. 127–146.10.1080/02670836.2018.1514096Search in Google Scholar

[41] Li, V. C., S. Wang, and C. Wu. Tensile strain-hardening behavior or polyvinyl alcohol engineered cementitious composite (PVA-ECC). ACI Materials Journal, Vol. 98, 2001, pp. 483–492.10.14359/10851Search in Google Scholar

[42] Hu, W., X. Yang, J. Zhou, H. Xing, and J. Xiang. Experimental research on the mechanical properties of PVA fiber reinforced concrete. Research Journal of Applied Sciences, Engineering and Technology, Vol. 5, No. 18, 2013, pp. 4563–4567.10.19026/rjaset.5.4375Search in Google Scholar

[43] Sun, M., Y. Z. Chen, J. Q. Zhu, T. Sun, Z. H. Shui, G. Ling, et al. Effect of modified polyvinyl alcohol fibers on the mechanical behavior of engineered cementitious composites. Materials, Vol. 12, No. 1, 2019, id. 37.10.3390/ma12010037Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[44] Xu, S., M. A. Malik, Z. Qi, B. Huang, Q. Li, and M. Sarkar. Influence of the PVA fibers and SiO2 NPs on the structural properties of fly ash based sustainable geopolymer. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 164, 2018, pp. 238–245.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2017.12.227Search in Google Scholar

[45] Ohno, M. and V. C. Li. A feasibility study of strain hardening fiber reinforced fly ash-based geopolymer composites. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 57, 2014, pp. 163–168.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2014.02.005Search in Google Scholar

[46] Nematollahi, B., J. Sanjayan, and F. U. A. Shaikh. Comparative deflection hardening behavior of short fiber reinforced geopolymer composites. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 70, 2014, pp. 54–64.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2014.07.085Search in Google Scholar

[47] Xu, F., X. Deng, C. Peng, J. Zhu, and J. Chen. Mix design and flexural toughness of PVA fiber reinforced fly ash-geopolymer composites. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 150, 2017, pp. 179–189.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2017.05.172Search in Google Scholar

[48] Golewski, G. L. Changes in the fracture toughness under Mode II loading of low calcium fly ash (LCFA) concrete depending on ages. Materials, Vol. 13, No. 22, 2020, id. 5241.10.3390/ma13225241Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[49] Golewski, G. L. A new principles for implementation and operation of foundations for machines: A review of recent advances. Structural Engineering and Mechanics, Vol. 71, No. 3, 2019, pp. 317–327.Search in Google Scholar

[50] Khalilpour, S., E. Baniasad, and M. Dehestani. A review on concrete fracture energy and effective parameters. Cement and Concrete Research, Vol. 120, 2019, pp. 294–321.10.1016/j.cemconres.2019.03.013Search in Google Scholar

[51] Golewski, G. L. and D. M. Gil. Studies of fracture toughness in concretes containing fly ash and silica fume in the first 28 days of curing. Materials, Vol. 14, No. 2, 2021, id. 319.10.3390/ma14020319Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[52] Zhang, H. Y., V. Kodur, B. Wu, J. Yan, and Z. S. Yuan. Effect of temperature on bond characteristics of geopolymer concrete. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 163, No. FEB.28, 2018, pp. 277–285.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2017.12.043Search in Google Scholar

[53] Perera, D. S., O. Uchida, E. R. Vance, and K. S. Finnie. Influence of curing schedule on the integrity of geopolymers. Journal of Materials Science, Vol. 42, No. 9, 2006, pp. 3099–3106.10.1007/s10853-006-0533-6Search in Google Scholar

[54] Deng, Y. F. Study on water in fly ash-based geopolymer and its concrete interfacial transition zone (In Chinese), Changsha University of Science and Technology, China, 2017.Search in Google Scholar

[55] Guan, J. F., P. Yuan, L. L. Li, X. H. Yao, Y. L. Zhang, and W. Meng. Rock fracture with statistical determination of fictitious crack growth. Theoretical and Applied Fracture Mechanics, Vol. 112, 2021, id. 102859.10.1016/j.tafmec.2021.102895Search in Google Scholar

[56] Guan, J. F., P. Yuan, X. Z. Hu, L. B. Qing, and X. H. Yao. Statistical analysis of concrete fracture using normal distribution pertinent to maximum aggregate size. Theoretical and Applied Fracture Mechanics, Vol. 101, 2019, pp. 236–253.10.1016/j.tafmec.2019.03.004Search in Google Scholar

[57] Guan, J. F., C. M. Li, J. Wang, L. B. Qing, Z. K. Song, and Z. P. Liu. Effect of polypropylene fiber content on flexural strength of lightweight foamed concrete at ambient and elevated temperatures. Theoretical and Applied Fracture Mechanics, Vol. 100, 2019, pp. 114–127.10.1016/j.tafmec.2019.01.008Search in Google Scholar

[58] D.T. 5332-2005. Norm for Fracture Test of Hydraulic Concrete (In Chinese), China electric power press, Beijing, China, 2005.Search in Google Scholar

[59] Zhang, P., K. Wang, J. Wang, J. Guo, and Y. Ling. Mechanical properties and prediction of fracture parameters of geopolymer/alkali-activated mortar modified with pva fiber and nano-SiO2. Ceramics International, Vol. 46, No. 12, 2020, pp. 20027–20037.10.1016/j.ceramint.2020.05.074Search in Google Scholar

[60] Xu, S., M. A. Malik, Z. Qi, B. Huang, Q. Li, and M. Sarkar. Influence of the PVA fibers and SiO2 NPs on the structural properties of fly ash based sustainable geopolymer. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 164, 2018, pp. 238–245.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2017.12.227Search in Google Scholar

[61] Li, V. C. A simplified micromechanical model of compressive strength of fiber-reinforced cementitious composites. Cement and Concrete Composites, Vol. 14, No. 2, 1992, pp. 131–141.10.1016/0958-9465(92)90006-HSearch in Google Scholar

[62] Yuan, Y., R. Zhao, R. Li, Y. Wang, Z. Cheng, F. Li, et al. Frost resistance of fiber-reinforced blended slag and class f fly ash-based geopolymer concrete under the coupling effect of freeze-thaw cycling and axial compressive loading - sciencedirect. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 250, 2020, id. 118831.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.118831Search in Google Scholar

[63] Noushini, A., K. Vessalas, and B. Samali. Flexural and tensile characteristic of polyvinyl alcohol fiber reinforced concrete (PVA-FRC). In 13th East Asia-pacific Conference on Structural Engineering and Construction, Sapporo, Japan, 2013.Search in Google Scholar

[64] Noushini, A., K. Vessalas, and B. Samali. Static mechanical properties of polyvinyl alcohol fibre reinforced concrete (PVA-FRC). Magazine of Concrete Research, Vol. 66, 2014, pp. 465–483. 10.1680/macr.13.00320 Search in Google Scholar

[65] Nuruddin, M. F., S. U. Khan, N. Shafiq, and T. Ayub. Strength prediction models for pva fiber-reinforced high-strength concrete. Journal of Materials in Civil Engineering, Vol. 27, No. 2, 2015, id. 04015034.10.1061/(ASCE)MT.1943-5533.0001279Search in Google Scholar

[66] Noushini, A., B. Samali, and K. Vessalas. Effect of polyvinyl alcohol (pva) fibre on dynamic and material properties of fibre reinforced concrete. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 49, 2013, pp. 374–383.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2013.08.035Search in Google Scholar

[67] Soulioti, D. V., N. M. Barkoula, A. Paipetis, and T. E. Matikas. Effects of fibre geometry and volume fraction on the flexural behaviour of steel-fibre reinforced concrete. Strain, Vol. 47, No. 1, 2011, pp. E535–E541.10.1111/j.1475-1305.2009.00652.xSearch in Google Scholar

[68] Noushini, A., B. Samali, and K. Vessalas. Effect of polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) fibre on dynamic and material properties of fibre reinforced concrete. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 49, 2013, pp. 374–383.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2013.08.035Search in Google Scholar

[69] Le, L. A., G. D. Nguyen, H. H. Bui, A. H. Sheikh, and A. Kotousov. Incorporation of micro-cracking and fibre bridging mechanisms in constitutive modelling of fibre reinforced concrete. Journal of the Mechanics and Physics of Solids, Vol. 133, 2019, id. 103732.10.1016/j.jmps.2019.103732Search in Google Scholar

[70] Xu, B., H. A. Toutanji, and J. Gilbert. Impact resistance of poly(vinyl alcohol) fiber reinforced high-performance organic aggregate cementitious material. Cement and Concrete Research, Vol. 40, No. 2, 2010, pp. 347–351.10.1016/j.cemconres.2009.09.006Search in Google Scholar

[71] Abasi, A., R. Hassanli, T. Vincent, and A. Manalo. Influence of prism geometry on the compressive strength of concrete masonry. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 264, 2020, id. 120182.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.120182Search in Google Scholar

[72] Fotouhi, F., G. D. Ashkezari, and M. Razmara. Experimental relationships between steel fiber volume fraction and mechanical properties of ultra-high performance fiber-reinforced concrete. Journal of Building Engineering, Vol. 32, 2020, id. 101613.10.1016/j.jobe.2020.101613Search in Google Scholar

[73] Sahai, V. Reinforced concrete structures, Arkan Danesh, Esfahan, 1987.Search in Google Scholar

[74] Fehling, E., M. Schmidt, J. Walraven, T. Leutbecher, and S. Fröhlich. Ultra-high performance concrete UHPC: fundamentals, design, examples, John Wiley & Sons, New Jersey, America, 2015.10.1002/9783433604076Search in Google Scholar

[75] Shadafza, E. and R. Saleh Jalali. The elastic modulus of steel Fiber Reinforced Concrete (SFRC) with random distribution of aggregate and fiber. Civil Engineering Infrastructures Journal, Vol. 49, No. 1, 2016, pp. 21–23.Search in Google Scholar

[76] Li, V. C. A simplified micromechanical model of compressive strength of fiber-reinforced cementitious composites. Cement and Concrete Composites, Vol. 14, No. 2, 1992, pp. 131–141.10.1016/0958-9465(92)90006-HSearch in Google Scholar

[77] Nuruddin, M. F., S. Ullah Khan, N. Shafiq, and T. Ayub. Strength prediction models for PVA fiber-reinforced high-strength concrete. Journal of Materials in Civil Engineering, Vol. 27, No. 12, 2015, id. 04015034.10.1061/(ASCE)MT.1943-5533.0001279Search in Google Scholar

[78] Olivia, M. and H. Nikraz. Properties of fly ash geopolymer concrete designed by Taguchi method. Materials and Design, Vol. 36, 2012, pp. 191–198.10.1016/j.matdes.2011.10.036Search in Google Scholar

[79] Yhmaa, B., A. Ra, A. Ha, and C. Ez. Clean production and properties of geopolymer concrete: A review. Journal of Cleaner Production, Vol. 251, 2020, id. 119679.10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.119679Search in Google Scholar

[80] Noushini, A., F. Aslani, A. Castel, R. I. Gilbert, B. Uy, and S. Foster. Compressive stress-strain model for low-calcium fly ash-based geopolymer and heat-cured Portland cement concrete. Cement and Concrete Composites, Vol. 73, 2016, pp. 136–146.10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2016.07.004Search in Google Scholar

[81] Li, K. F., C. Q. Yang, W. Huang, Y. B. Zhao, and F. Xu. Effects of hybrid fibers on workability, mechanical, and time-dependent properties of high strength fiber-reinforced self-consolidating concrete. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 277, No. 5, 2021, id. 122325.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2021.122325Search in Google Scholar

[82] Wei, H., X. Yang, J. Zhou, H. Xing, and J. Xiang. Experimental research on the mechanical properties of pva fiber reinforced concrete. Research Journal of Applied Sciences Engineering and Technology, Vol. 5, No. 18, 2013, pp. 4563–4567.10.19026/rjaset.5.4375Search in Google Scholar

[83] Khan, S. U. and T. Ayub. Modelling of the pre and post-cracking response of the pva fibre reinforced concrete subjected to direct tension. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 120, 2016, pp. 540–557.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2016.05.130Search in Google Scholar

[84] Noushini, A., M. Hastings, A. Castel, and F. Aslani. Mechanical and flexural performance of synthetic fibre reinforced geopolymer concrete. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 186, 2018, pp. 454–475.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2018.07.110Search in Google Scholar

[85] Toutanji, H., B. Xu, J. Gilbert, and T. Lavin. Properties of poly(vinyl alcohol) fiber reinforced high-performance organic aggregate cementitious material: Converting brittle to plastic. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 24, No. 1, 2010, pp. 1–10.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2009.08.023Search in Google Scholar

[86] Carrillo, J., J. Ramirez, and J. Lizarazo-Marriaga. Modulus of elasticity and Poisson’s ratio of fiber-reinforced concrete in Colombia from ultrasonic pulse velocities. Journal of Building Engineering, Vol. 23, 2019, pp. 18–26.10.1016/j.jobe.2019.01.016Search in Google Scholar

[87] Noushini, A., M. Hastings, A. Castel, and F. Aslani. Mechanical and flexural performance of synthetic fibre reinforced geopolymer concrete. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 186, 2018, pp. 454–475.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2018.07.110Search in Google Scholar

[88] Phoo-Ngernkham, T., V. Sata, S. Hanjitsuwan, C. Ridtirud, S. Hatanaka, and P. Chindaprasirt. Compressive strength, bending and fracture characteristics of high calcium fly ash geopolymer mortar containing portland cement cured at ambient temperature. Arabian Journal for Science and Engineering, Vol. 41, No. 4, 2016, pp. 1263–1271.10.1007/s13369-015-1906-4Search in Google Scholar

[89] Ding, Y. and Y. L. Bai. Fracture properties and softening curves of steel fiber-reinforced slag-based geopolymer mortar and concrete. Materials, Vol. 11, No. 8, 2018, id. 1445.10.3390/ma11081445Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[90] Hossain, K., M. Lachemi, M. Sammour, and M. Sonebi. Strength and fracture energy characteristics of self-consolidating concrete incorporating polyvinyl alcohol, steel and hybrid fibres. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 45, 2013, pp. 20–29.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2013.03.054Search in Google Scholar

[91] Ling, Y., P. Zhang, J. Wang, and Y. Chen. Effect of PVA fiber on mechanical properties of cementitious composite with and without nano-SiO2. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 229, 2019, id. 117068.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2019.117068Search in Google Scholar

[92] Ywa, B., C. Sh, and H. B. Zhen. Mechanical and fracture properties of geopolymer concrete with basalt fiber using digital image correlation - ScienceDirect. Theoretical and Applied Fracture Mechanics, Vol. 112, 2021, id. 102909.10.1016/j.tafmec.2021.102909Search in Google Scholar

[93] Li, V. C. and H. Stang. Interface property characterization and strengthening mechanisms in fiber reinforced cement based composites. Advanced Cement Based Materials, Vol. 6, 1997, pp. 1–20.10.1016/S1065-7355(97)90001-8Search in Google Scholar

© 2021 Peng Zhang et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Review Articles

- A review on filler materials for brazing of carbon-carbon composites

- Nanotechnology-based materials as emerging trends for dental applications

- A review on allotropes of carbon and natural filler-reinforced thermomechanical properties of upgraded epoxy hybrid composite

- High-temperature tribological properties of diamond-like carbon films: A review

- A review of current physical techniques for dispersion of cellulose nanomaterials in polymer matrices

- Review on structural damage rehabilitation and performance assessment of asphalt pavements

- Recent development in graphene-reinforced aluminium matrix composite: A review

- Mechanical behaviour of precast prestressed reinforced concrete beam–column joints in elevated station platforms subjected to vertical cyclic loading

- Effect of polythiophene thickness on hybrid sensor sensitivity

- Investigation on the relationship between CT numbers and marble failure under different confining pressures

- Finite element analysis on the bond behavior of steel bar in salt–frost-damaged recycled coarse aggregate concrete

- From passive to active sorting in microfluidics: A review

- Research Articles

- Revealing grain coarsening and detwinning in bimodal Cu under tension

- Mesoporous silica nanoparticles functionalized with folic acid for targeted release Cis-Pt to glioblastoma cells

- Magnetic behavior of Fe-doped of multicomponent bismuth niobate pyrochlore

- Study of surfaces, produced with the use of granite and titanium, for applications with solar thermal collectors

- Magnetic moment centers in titanium dioxide photocatalysts loaded on reduced graphene oxide flakes

- Mechanical model and contact properties of double row slewing ball bearing for wind turbine

- Sandwich panel with in-plane honeycombs in different Poisson's ratio under low to medium impact loads

- Effects of load types and critical molar ratios on strength properties and geopolymerization mechanism

- Nanoparticles in enhancing microwave imaging and microwave Hyperthermia effect for liver cancer treatment

- FEM micromechanical modeling of nanocomposites with carbon nanotubes

- Effect of fiber breakage position on the mechanical performance of unidirectional carbon fiber/epoxy composites

- Removal of cadmium and lead from aqueous solutions using iron phosphate-modified pollen microspheres as adsorbents

- Load identification and fatigue evaluation via wind-induced attitude decoupling of railway catenary

- Residual compression property and response of honeycomb sandwich structures subjected to single and repeated quasi-static indentation

- Experimental and modeling investigations of the behaviors of syntactic foam sandwich panels with lattice webs under crushing loads

- Effect of storage time and temperature on dissolved state of cellulose in TBAH-based solvents and mechanical property of regenerated films

- Thermal analysis of postcured aramid fiber/epoxy composites

- The energy absorption behavior of novel composite sandwich structures reinforced with trapezoidal latticed webs

- Experimental study on square hollow stainless steel tube trusses with three joint types and different brace widths under vertical loads

- Thermally stimulated artificial muscles: Bio-inspired approach to reduce thermal deformation of ball screws based on inner-embedded CFRP

- Abnormal structure and properties of copper–silver bar billet by cold casting

- Dynamic characteristics of tailings dam with geotextile tubes under seismic load

- Study on impact resistance of composite rocket launcher

- Effects of TVSR process on the dimensional stability and residual stress of 7075 aluminum alloy parts

- Dynamics of a rotating hollow FGM beam in the temperature field

- Development and characterization of bioglass incorporated plasma electrolytic oxidation layer on titanium substrate for biomedical application

- Effect of laser-assisted ultrasonic vibration dressing parameters of a cubic boron nitride grinding wheel on grinding force, surface quality, and particle morphology

- Vibration characteristics analysis of composite floating rafts for marine structure based on modal superposition theory

- Trajectory planning of the nursing robot based on the center of gravity for aluminum alloy structure

- Effect of scan speed on grain and microstructural morphology for laser additive manufacturing of 304 stainless steel

- Influence of coupling effects on analytical solutions of functionally graded (FG) spherical shells of revolution

- Improving the precision of micro-EDM for blind holes in titanium alloy by fixed reference axial compensation

- Electrolytic production and characterization of nickel–rhenium alloy coatings

- DC magnetization of titania supported on reduced graphene oxide flakes

- Analytical bond behavior of cold drawn SMA crimped fibers considering embedded length and fiber wave depth

- Structural and hydrogen storage characterization of nanocrystalline magnesium synthesized by ECAP and catalyzed by different nanotube additives

- Mechanical property of octahedron Ti6Al4V fabricated by selective laser melting

- Physical analysis of TiO2 and bentonite nanocomposite as adsorbent materials

- The optimization of friction disc gear-shaping process aiming at residual stress and machining deformation

- Optimization of EI961 steel spheroidization process for subsequent use in additive manufacturing: Effect of plasma treatment on the properties of EI961 powder

- Effect of ultrasonic field on the microstructure and mechanical properties of sand-casting AlSi7Mg0.3 alloy

- Influence of different material parameters on nonlinear vibration of the cylindrical skeleton supported prestressed fabric composite membrane

- Investigations of polyamide nano-composites containing bentonite and organo-modified clays: Mechanical, thermal, structural and processing performances

- Conductive thermoplastic vulcanizates based on carbon black-filled bromo-isobutylene-isoprene rubber (BIIR)/polypropylene (PP)

- Effect of bonding time on the microstructure and mechanical properties of graphite/Cu-bonded joints

- Study on underwater vibro-acoustic characteristics of carbon/glass hybrid composite laminates

- A numerical study on the low-velocity impact behavior of the Twaron® fabric subjected to oblique impact

- Erratum

- Erratum to “Effect of PVA fiber on mechanical properties of fly ash-based geopolymer concrete”

- Topical Issue on Advances in Infrastructure or Construction Materials – Recycled Materials, Wood, and Concrete

- Structural performance of textile reinforced concrete sandwich panels under axial and transverse load

- An overview of bond behavior of recycled coarse aggregate concrete with steel bar

- Development of an innovative composite sandwich matting with GFRP facesheets and wood core

- Relationship between percolation mechanism and pore characteristics of recycled permeable bricks based on X-ray computed tomography

- Feasibility study of cement-stabilized materials using 100% mixed recycled aggregates from perspectives of mechanical properties and microstructure

- Effect of PVA fiber on mechanical properties of fly ash-based geopolymer concrete

- Research on nano-concrete-filled steel tubular columns with end plates after lateral impact

- Dynamic analysis of multilayer-reinforced concrete frame structures based on NewMark-β method

- Experimental study on mechanical properties and microstructures of steel fiber-reinforced fly ash-metakaolin geopolymer-recycled concrete

- Fractal characteristic of recycled aggregate and its influence on physical property of recycled aggregate concrete

- Properties of wood-based composites manufactured from densified beech wood in viscoelastic and plastic region of the force-deflection diagram (FDD)

- Durability of geopolymers and geopolymer concretes: A review

- Research progress on mechanical properties of geopolymer recycled aggregate concrete

Articles in the same Issue

- Review Articles

- A review on filler materials for brazing of carbon-carbon composites

- Nanotechnology-based materials as emerging trends for dental applications

- A review on allotropes of carbon and natural filler-reinforced thermomechanical properties of upgraded epoxy hybrid composite

- High-temperature tribological properties of diamond-like carbon films: A review

- A review of current physical techniques for dispersion of cellulose nanomaterials in polymer matrices

- Review on structural damage rehabilitation and performance assessment of asphalt pavements

- Recent development in graphene-reinforced aluminium matrix composite: A review

- Mechanical behaviour of precast prestressed reinforced concrete beam–column joints in elevated station platforms subjected to vertical cyclic loading

- Effect of polythiophene thickness on hybrid sensor sensitivity

- Investigation on the relationship between CT numbers and marble failure under different confining pressures

- Finite element analysis on the bond behavior of steel bar in salt–frost-damaged recycled coarse aggregate concrete

- From passive to active sorting in microfluidics: A review

- Research Articles

- Revealing grain coarsening and detwinning in bimodal Cu under tension

- Mesoporous silica nanoparticles functionalized with folic acid for targeted release Cis-Pt to glioblastoma cells

- Magnetic behavior of Fe-doped of multicomponent bismuth niobate pyrochlore

- Study of surfaces, produced with the use of granite and titanium, for applications with solar thermal collectors

- Magnetic moment centers in titanium dioxide photocatalysts loaded on reduced graphene oxide flakes

- Mechanical model and contact properties of double row slewing ball bearing for wind turbine

- Sandwich panel with in-plane honeycombs in different Poisson's ratio under low to medium impact loads

- Effects of load types and critical molar ratios on strength properties and geopolymerization mechanism

- Nanoparticles in enhancing microwave imaging and microwave Hyperthermia effect for liver cancer treatment

- FEM micromechanical modeling of nanocomposites with carbon nanotubes

- Effect of fiber breakage position on the mechanical performance of unidirectional carbon fiber/epoxy composites

- Removal of cadmium and lead from aqueous solutions using iron phosphate-modified pollen microspheres as adsorbents