Abstract

In this analysis, the baffling method is used to increase the efficiency of channel heat exchangers (CHEs). The present CFD (computational fluid dynamics)-based work aims to analyze the constant property, steady, turbulent, Newtonian, and incompressible fluid flow (air), in the presence of transverse-section, arc-shaped vortex generators (VGs) with two various geometrical models, i.e., arc towards the inlet section (called arc-upstream) and arc towards the outlet section (called arc-downstream), attached to the hot lower wall, in an in-line situation, through a horizontal duct. For the investigated range of Reynolds number (from 12,000 to 32,000), the order of the thermal exchange and pressure loss went from 1.599–3.309 to 3.667–21.103 times, respectively, over the values obtained with the unbaffled exchanger. The arc-downstream configuration proved its superiority in terms of thermal exchange rate by about 14% than the other shape of baffle. Due to ability to produce strong flows, the arc-downstream baffle has given the highest outlet bulk temperature.

1 Introduction

The enhancement of the efficiency of heat exchangers (HEs) by the deflector insertion technique in the fluid flow domain has many engineering and industrial applications. By using numerical simulations, Pirouz et al. [1] used the Lattice Boltzmann Method (LBM) to explore the thermal behavior in a channel heat exchanger (CHE) equipped by upper and lower wall-inserted baffles. The influence of several geometrical variables of helical baffles on the overall performances of HEs was explored by Du et al. [2]. Based on the concepts of permeability and porosity, You et al. [3] introduced a numerical approach for shell-and-tube heat exchangers (STHXs). They used the distribution of turbulence kinetic energy, dissipation rate of energy, and heat source to estimate the effect of tubes on fluid. Eiamsa-ard and Promvonge [4] explored the efficiency of a CHE having grooves on the lower wall. Also, Afrianto et al. [5] predicted the hydrothermal characteristics of liquid natural gas (LNG) in a HE. Additionally, for several Reynolds numbers (from 4,475 to 43,725), Ozceyhan et al. [6] explored the influence of the presence of rings near the wall and their clearance on the overall performances of a CHE. Furthermore, the improvements in heat transfer rates that are yielded by the baffling technique in a pipe heat exchanger (PHE) have been reported by Nasiruddin and Siddiqui [7]. Moreover, via the CFD software FLUENT, Zhang et al. [8] provided details on a PHE with overlapped helical baffles. Also, under laminar flow conditions and with the help of CFD software, Sripattanapipat and Promvonge [9] analyzed the hydrothermal characteristics through a 2D CHE. They used baffles with diamond shape and inserted in a staggered arrangement. Additionally, Santos and de Lemos [10] were interested in a channel having baffles constructed from porous and impermeable materials. Via numerical analysis and for a tube heat exchanger (THE), Xiao et al. [11] used different values of Prandtl number and helical tilt angles for helical baffles. Mohsenzadeh et al. [12] analyzed the forced convective thermal transfer through a horizontal CHE. They explored the influence of baffle clearance and Reynolds number. Under turbulent flow conditions, Valencia and Cid [13] used the CFD method to study the hydrothermal details in a CHE provided with square bars in the streamwise direction of flow. In another study, Promvonge et al. [14] determined the hydrothermal fields in a 3D CHE-inclined V-shaped discrete thin VGs (vortex generators).

By experiments, Zhang et al. [15] explored the hydrothermal fields of STHEs equipped by helical baffles. Also, Wang et al. [16] were interested in the flow through a channel provided with pin fins. Additionally, Dutta and Hossain [17] were interested in a CHE having perforated baffles under various inclination angles. In another study, Ali et al. [18] studied the thermal transfer phenomenon from the outer surface of horizontal cylinders. Furthermore, Wang et al. [19] characterized the hydrothermal fields through a channel having periodic ribs on one wall. Moreover, Rivir et al. [20] achieved measurements of the flow details in a CHE equipped with transverse ribs on the sidewalls. They explored the effect of three geometrical cases: single rib, staggered multiple ribs, and in-line multiple ribs.

Other interesting studies are available in the literature for various fluid flow situations and different numerical solutions, for example, see Kazem et al. [21], Rashidi et al. [22], Kumar et al. [23,24,25], Ghanbari et al. [26], Goufo et al. [27], Shafiq et al. [28], Ilhan et al. [29], Basha et al. [30], Baskonus [31], Guedda and Hammouch [32], Ahmad et al. [33,34,35,36], and Menni et al. [37,38,39,40,41,42]. Most of the studies carried out focused on the HE in order to improve its performance. Enhancing heat transfer is the goal of most researches in both numerical and experimental studies. So, the topic is very interesting, which led us to search a technique to increase the effectiveness of the exchanger. This work is a numerical analysis of a constant property, steady, turbulent, Newtonian, and incompressible fluid flow (air) inside a rectangular duct heat exchanger. Two types of transverse, solid-type, and arc-shaped obstacles are attached on the lower hot wall in in-line arrays, namely, an arc towards the inlet section (called arc-upstream) and an arc towards the outlet section (called arc-downstream). Both obstacle forms give a different structure to the flow, which enhances heat transfer in different amounts. The study compares the best performance which identifies the effective model.

2 Physical model under analysis

A numerical simulation was reported on the turbulent flow and forced-convection of an incompressible Newtonian fluid (air) with constant thermal physical properties and flowing inside a channel (Figure 1). Two transverse, solid, in-line obstacles having various geometrical configurations, i.e., arc towards the inlet section of the channel, called arc-upstream (Figure 1a), and arc towards the exit section of the channel, called arc-downstream (Figure 1b), were fitted into the duct and attached on the bottom wall to lengthen the trajectory of the fluid and increase the heat exchange surface.

![Figure 1

Baffled ducts under inspection (a) duct with in-line arc-upstream, (b) duct with in-line arc-downstream baffles. The dimensions (L, H, L

in, a, b, and c) are selected from [43].](/document/doi/10.1515/phys-2021-0005/asset/graphic/j_phys-2021-0005_fig_001.jpg)

Baffled ducts under inspection (a) duct with in-line arc-upstream, (b) duct with in-line arc-downstream baffles. The dimensions (L, H, L in, a, b, and c) are selected from [43].

Two new models of VGs are suggested in the present study, namely, arc-upstream and arc-downstream baffles. The values of height (H) and length (L) of the channel are 0.146 and 0.554 m, respectively. The first arc-shaped baffle is attached on the lower wall at L in = 0.218 m from the entrance section of the channel, while the 2nd arc-shaped obstacle is inserted at c = 0.142 m from the first obstacle. The baffles height (a), thickness (b), and attack (θ) are 0.08 m, 0.01 m, and 45°, respectively. Air is used as a working fluid and Reynolds numbers are changed from 12,000 to 32,000.

3 Modelling and simulation

For the steady state with neglected radiation thermal exchange mode, the equations of mass, momentum, and energy are expressed as [7]

where,

where, μ t is the fluid turbulent viscosity (kg m−1 s−1); and C μ , C 1ε , C 2ε , σ k , and σ ε are the model constants. The present thermal and hydrodynamic limit conditions are expressed as [45]:

At x = 0

At y = ±H/2

At x = L

where, ϕ stands for the dependent variables u, v, k, T, and ε. The calculations are achieved with the finite volume technique [46], SIMPLE algorithm [46], and the Quick scheme [47]. The Nu0 and f 0 values of the unbaffled channel were verified [38] by comparing them with the correlations of Dittus–Boelter [48] and Petukhov [49], respectively. The comparison demonstrated that there is a quantitative agreement between the CFD data and the experimental relationships results [48,49].

4 Results and discussion

4.1 Stream-function field

Figure 2 illustrates the streamlines for the different arc-baffle configurations, i.e., arc-upstream and arc-downstream. For the two studied geometrical models, the flow is uniform until reaching the 1st arc-baffle. Then, recirculating flows are formed at the baffled region, referenced here as ‘zone A.’ The size of these vortices is significant in the case of arc-upstream type baffles. The sharp edge of the baffle presents a point of detachment, the so referenced here as ‘zone B.’ The flow is then detached from the arc-baffle, resulting thus in a depression behind baffles. Furthermore, recirculation areas (zones ‘C’ and ‘D’) are formed behind baffles, where the widest recirculation zone is observed with the arc-downstream baffle. It is surrounded by iso-surfaces that take elliptical shapes.

Stream-function fields (Ψ) for both cases under investigation: (a) arc-upstream baffled channel, (b) arc-downstream baffled channel, Re = 12,000 (Ψ values in kg s−1).

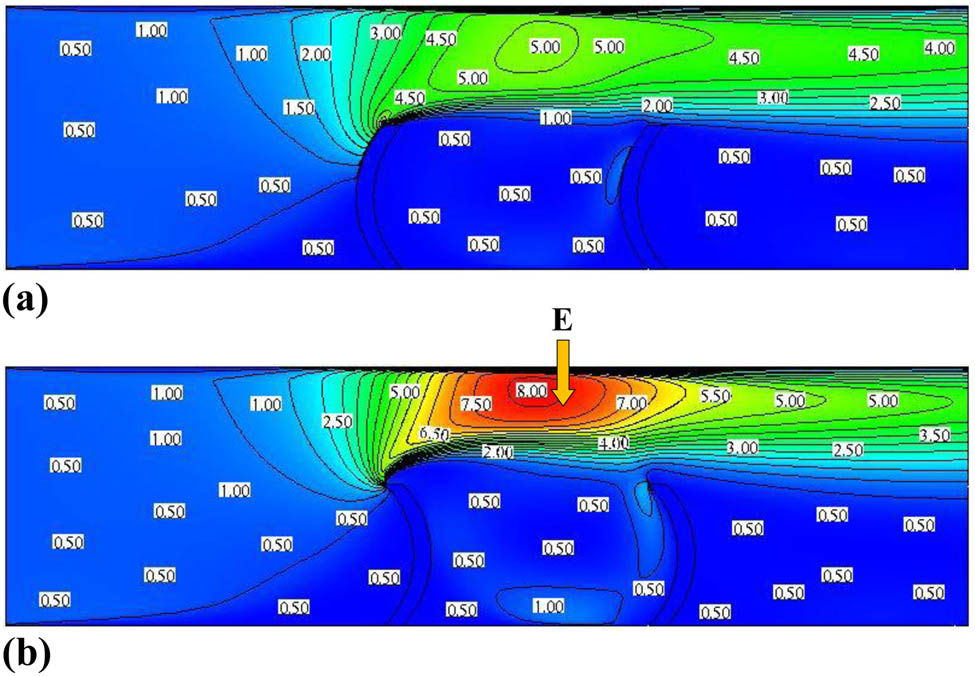

4.2 Mean velocity field

Figure 3 reports the mean velocity fields for different configurations of arc-baffles, i.e., arc-upstream and arc-downstream. The velocities are weak next to the left side of the first arc-baffle, region ‘A,’ for both models of arc-obstacles studied. The velocity magnitudes are also low behind the second arc-VG. The velocity is important at the edge of the first and the second arc-shaped baffles, zone ‘E.’ In this same region, the fluid velocity for the second obstacle type (arc-downstream baffle) reaches up to 3.64 m/s, followed by that of the first type (arc-upstream baffle), 3.28 m/s. In the regions between both the first and the second arc-baffles, zone ‘C,’ the airflow velocity is significant in the arc-downstream model than that of the other model.

Mean velocity fields (V) for both cases under investigation: (a) arc-upstream baffled channel, (b) arc-downstream baffled channel, Re = 12,000 (V values in m s−1).

4.3 Axial velocity field

Figure 4 illustrates the impact of the variation of the arc-VG geometry on the axial velocity field. For both kinds of baffles, the streamlines are parallel in the unbaffled areas of the duct. However, the velocity magnitudes are almost negligible in the downstream areas of arc-baffles, zones ‘C’ and ‘D,’ which is caused by the presence of recirculating flows. An increase in the velocity is observed in the space between the tip of arc-VG to the upper wall of the exchanger, referenced here as ‘zone E.’ This is due to the presence of the arc-shaped VG and the abrupt modification in the flow direction.

Axial velocity (u) for various arc-baffle configurations: (a) arc-upstream, (b) arc-downstream, Re = 12,000 (u values in m s−1).

The fluid flow is accelerated just after the first arc-VG until reaching 274–346% of the inlet velocity, depending on the shape of VGs. It should be noted that the VG configuration has a significant influence in the zones ‘C,’ ‘D,’ and E,’ which is mainly caused by the modification in the streamlines. The arc-upstream baffle increased the axial velocity by about 2.747 times over the inlet velocity U in (Figure 4).

4.4 Transverse velocity field

The distribution of y-transverse velocity is plotted in Figure 5a and b for the arc-upstream and arc-downstream baffles, respectively. Positive and negative velocity gradients are remarked at the tip of the 1st arc-baffle (zones ‘B’) and 2nd arc-baffle (zone ‘F’), respectively.

Fields of the transverse velocity (v) for various arc-baffle models: (a) arc-upstream, (b) arc-downstream, Re = 12,000 (v values in m s−1).

4.5 Dynamic-pressure field

The dynamic-pressure fields for both arc-obstacle configurations are plotted in Figure 6. As illustrated in this figure, the values of the dynamic-pressure coefficient are weak near the VGs due to the presence of vortices.

Fields of the dynamic pressure (P d) for various arc-baffle types: (a) arc-upstream, and (b) arc-downstream, Re = 12,000 (P d values in Pa).

However, the dynamic-pressure augments in the regions between the baffles tip and the upper wall of the exchanger, where the maximum values are located between the 1st and 2nd arc-baffles (zone ‘E’), which is resulted from the high airflow velocities. In addition, the highest amount of P d depends on the shape of arc-VG, where it is lower by about 18% for the arc-upstream baffle than that for the other case.

4.6 Dimensionless axial velocity profiles

The curves of the dimensionless axial velocity (U/U in) just after the two baffles are plotted in Figure 7. As observed, the reattachment length for the arc-downstream baffle is greater than that for the arc-upstream-baffle, regardless of the value of Re.

Influence of arc-baffle orientation on the length of recirculation cells vs Re. (a) at x = 0.315 m (downstream of the 1st VG) (b) at x = 0.435 m (downstream of the 2nd VG).

4.7 Thermal fields

The thermal fields illustrated in Figure 8 show that the baffled region is the most heated. The temperature drops in the areas between the tip of arc-obstacle and the surfaces of the duct, which is due to the high fluid velocity and interaction between the fluid particles in these regions.

Temperature contours (T) for (a) arc-upstream, (b) arc-downstream baffles at Re = 12,000 (T values in K).

A comparison of the outlet fluid temperature is provided in Figure 9, where the most considerable values of the temperature are reached with the arc-downstream baffle. Because of its ability to produce strong flows, the arc-downstream-shaped VG is more advantageous than the other model.

Outlet fluid temperature profiles for (a) arc-upstream, (b) arc-downstream VGs, at Re = 12,000.

4.8 Heat transfer

The results of the ratio (Nu x /Nu0) are summarized in Figure 10 for both arc-shaped baffles. Both the arc-deflectors push the flow towards the upper part of the duct, which allows further absorption of the thermal energy from the heated surface. The lowest value of the Nu x /Nu0 is observed on the upstream side of the first arc-baffle, while the highest amount is remarked on the opposite side of the 2nd arc-baffle. This figure shows also that the Nu x /Nu0 is considerable in the downstream area of the 1st arc-VG. This augmentation is yielded from the efficient mixing by vortices, which corresponds to high rates of the local thermal exchange. For both shapes of baffles, the values of (Nu x /Nu0) are similar at the positions between (0 m) and (0.2 m). However, there is an important increase in the (Nu x /Nu0) in the case of arc-downstream type baffle from the position (0.2 m) until the outlet of the duct.

Normalized local Nusselt number on upper wall of the channel for various arc-baffles, Re = 12,000.

Figure 11 presents the change of the average ratio (Nu/Nu0), where a proportional increase is observed according to Re. The maximum Nu/Nu0 is reached with the arc-downstream case. Compared to the unbaffled exchanger and for Re = 12,000–32,000, the average Nu gains for the arc-upstream and arc-downstream baffles are 159–284% and 187–331%, respectively. In addition, and at the highest Re, the arc-downstream baffle overcomes the other shape of baffles by about 14% in terms of thermal exchange rates (Nu/Nu0) than that reached with the arc-upstream (Figure 11).

Normalized average Nusselt number with Re for various arc-baffles.

4.9 Friction loss

The variation of the normalized skin friction coefficient (C f /f 0) on the top wall of the duct is provided in Figure 12. From this figure, both shapes of the baffles give the same trends of C f /f 0. Also, an increased C f /f 0 is observed in the region between the arc-baffles (0.228 m < x < 0.37 m). The arc-upstream and arc-downstream baffles provided, respectively, an increase in C f by about 73 and 117 times over the unbaffled exchanger. Furthermore, the use of arc-downstream baffles gives higher thermal exchange than that of the other model by about 37%.

Variation of Normalized skin friction coefficient along upper channel wall for various arc-baffles, Re = 12,000.

The changes of the friction factor ratio (f/f 0) vs Re are shown in Figure 13. A proportional increase is observed in the values of Re (f/f 0). In addition, and compared to the smooth duct, the arc-upstream and arc-downstream baffles provided, respectively, an increase in (f/f 0) by about 3–16 and 4–21 times when Re has been changed from 12,000 to 32,000. This means that the arc-downstream baffle generates greater friction loss than the arc-upstream baffle by around 23.266%, at the highest Re.

Variation of Normalized friction factor with Re for various arc-baffles.

4.10 Effect of the arc-shaped baffle

Finally, the results of the thermal performance factor (TEF) are summarized in Figure 14. As observed, the TEF tends to augment with the rise of Re for both shapes of VGs under inspection. At Re = 32,000, the optimum value of the TEF is about 1.138 and 1.212 for the arc-upstream and arc-downstream-shaped baffles, respectively. Accordingly, the highest TEF is found with arc-downstream baffle, which is estimated to be higher than that of the arc-upstream baffles by about 6%. The effect of arc-downstream baffles can also be highlighted based on literature data. In the presence of the following conditions: L = 0.554 m, L in = 0.218 m, H = 0.146 m, D h = 0.167 m, a = 0.08 m, b = 0.01 m, and Re = 32,000, their performance has been compared with many previously realized baffles [42]. The relative difference of results shows a remarkable improvement in the presence of an in-line downstream arc-baffle pair by about 7.019, 3.958, 3.130, 3.580, 6.572, 10.815, 7.536, 1.715, 11.485, 10.971, and 8.221% over the upstream-arc, rectangular (simple), triangular, trapezoidal, corrugated, plus, S, V, W, T, and Γ-shaped one-baffle channel, respectively (Figure 15).

Changes in the thermal enhancement factor vs Re.

Performance comparison with numerical data for various baffles at Re = 32,000.

5 Conclusion

A numerical inspection has been conducted on the characteristics of the turbulent convection of air flowing in a baffled rectangular exchanger. Two shapes of arc-baffles were considered, namely, the arc-upstream and arc-downstream shapes. These obstacles were inserted on bottom wall of the exchanger in in-line arrays. The result analysis shows a reinforcement in fluid dynamics with a considerable enhancement in heat exchange in the case of the arc-downstream second obstacle due to the secretion of very strong cells on their back sides, which also caused a significant increase in skin friction coefficients, especially at high flow rates. This second configuration of the arc-baffle (arc-downstream) proved its superiority in terms of thermal exchange rate by about 14% than the other shape of baffle. At Re = 32,000, this optimal model of the arc-baffle showed an increase in the enhancement factor by about 7.019, 3.958, 3.130, 3.580, 6.572, 10.815, 7.536, 1.715, 11.485, 10.971, and 8.221% compared to the cases of one baffle, i.e., upstream-arc, rectangular (simple), triangular, trapezoidal, corrugated, plus, S, V, W, T, and Γ, respectively.

-

Funding: This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 71601072) and Key Scientific Research Project of Higher Education Institutions in Henan Province of China (No. 20B110006).

References

[1] Pirouz MM, Farhadi M, Sedighi K, Nemati H, Fattahi E. Lattice Boltzmann simulation of conjugate heat transfer in a rectangular channel with wall-mounted obstacles. Sci Iran B. 2011;18(2):213–21.10.1016/j.scient.2011.03.016Search in Google Scholar

[2] Du T, Du W, Che K, Cheng L. Parametric optimization of overlapped helical baffled heat exchangers by Taguchi method. Appl Therm Eng. 2015;85:334–9.10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2015.02.058Search in Google Scholar

[3] You Y, Fan A, Huang S, Liu W. Numerical modeling and experimental validation of heat transfer and flow resistance on the shell side of a shell-and-tube heat exchanger with flower baffles. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 2012;55:7561–9.10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2012.07.058Search in Google Scholar

[4] Eiamsa-ard S, Promvonge P. Numerical study on heat transfer of turbulent channel flow over periodic grooves. Int Commun Heat Mass Transf. 2008;35:844–52.10.1016/j.icheatmasstransfer.2008.03.008Search in Google Scholar

[5] Afrianto H, Tanshen MdR, Munkhbayar B, Suryo UT, Chung H, Jeong H. A numerical investigation on LNG flow and heat transfer characteristic in heat exchanger. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 2014;68:110–8.10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2013.09.036Search in Google Scholar

[6] Ozceyhan V, Gunes S, Buyukalaca O, Altuntop N. Heat transfer enhancement in a tube using circular cross sectional rings separated from wall. Appl Energy. 2008;85:988–1001.10.1016/j.apenergy.2008.02.007Search in Google Scholar

[7] Nasiruddin MH, Siddiqui K. Heat transfer augmentation in a heat exchanger tube using a baffle. Int J Heat Fluid Flow. 2007;28:318–28.10.1016/j.ijheatfluidflow.2006.03.020Search in Google Scholar

[8] Zhang JF, He YL, Tao WQ. 3D numerical simulation on shell-and-tube heat exchangers with middle-overlapped helical baffles and continuous baffles – Part I: numerical model and results of whole heat exchanger with middle-overlapped helical baffles. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 2009;52:5371–80.10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2009.07.006Search in Google Scholar

[9] Sripattanapipat S, Promvonge P. Numerical analysis of laminar heat transfer in a channel with diamond-shaped baffles. Int Commun Heat Mass Transf. 2009;36:32–8.10.1016/j.icheatmasstransfer.2008.09.008Search in Google Scholar

[10] Santos NB, de Lemos MJS. Flow and heat transfer in a parallel-plate channel with porous and solid baffles. Numer Heat Transfer Part A. 2006;49:1–24.10.1080/10407780500325001Search in Google Scholar

[11] Xiao X, Zhang L, Li X, Jiang B, Yang X, Xia Y. Numerical investigation of helical baffles heat exchanger with different Prandtl number fluids. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 2013;63:434–44.10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2013.04.001Search in Google Scholar

[12] Mohsenzadeh A, Farhadi M, Sedighi K. Convective cooling of tandem heated triangular cylinders confirm in a channel. Therm Sci. 2010;14(1):183–97.10.2298/TSCI1001183MSearch in Google Scholar

[13] Valencia A, Cid M. Turbulent unsteady flow and heat transfer in channels with periodically mounted square bars. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 2002;45:1661–73.10.1016/S0017-9310(01)00267-8Search in Google Scholar

[14] Promvonge P, Changcharoen W, Kwankaomeng S, Thianpong C. Numerical heat transfer study of turbulent square-duct flow through inline V-shaped discrete ribs. Int Commun Heat Mass Transf. 2011;38:1392–9.10.1016/j.icheatmasstransfer.2011.07.014Search in Google Scholar

[15] Zhang JF, Li B, Huang WJ, Lei YG, He YL, Tao WQ. Experimental performance comparison of shell-side heat transfer for shell-and-tube heat exchangers with middle-overlapped helical baffles and segmental baffles. Chem Eng Sci. 2009;64:1643–53.10.1016/j.ces.2008.12.018Search in Google Scholar

[16] Wang F, Zhang J, Wang S. Investigation on flow and heat transfer characteristics in rectangular channel with drop-shaped pin fins. Propuls Power Res. 2012;1(1):64–70.10.1016/j.jppr.2012.10.003Search in Google Scholar

[17] Dutta P, Hossain A. Internal cooling augmentation in rectangular channel using two inclined baffles. Int J Heat Fluid Flow. 2005;26:223–32.10.1016/j.ijheatfluidflow.2004.08.001Search in Google Scholar

[18] Ali M, Zeitoun O, Nuhait A. Forced convection heat transfer over horizontal triangular cylinder in cross flow. Int J Therm Sci. 2011;50:106–14.10.1016/j.ijthermalsci.2010.09.007Search in Google Scholar

[19] Wang L, Salewski M, Sundén B. Turbulent flow in a ribbed channel: flow structures in the vicinity of a rib. Exp Therm Fluid Sci. 2010;34(2):165–76.10.1016/j.expthermflusci.2009.10.005Search in Google Scholar

[20] Rivir RB. Turbulence and scale measurements in a square channel with transverse square ribs. Int J Rotating Mach. 1996;2:756352.10.1155/S1023621X96000085Search in Google Scholar

[21] Kazem S, Abbasbandy S, Kumar S. Fractional-order legendre functions for solving fractional-order differential equations. Appl Math Model. 2013;37(7):5498–510.10.1016/j.apm.2012.10.026Search in Google Scholar

[22] Rashidi MM, Hosseini A, Pop I, Kumar S, Freidoonimehr N. Comparative numerical study of single and two-phase models of nanofluid heat transfer in wavy channel. Appl Math Mech. 2014;35(7):831–48.10.1007/s10483-014-1839-9Search in Google Scholar

[23] Kumar S. A new analytical modelling for fractional telegraph equation via laplace transform. Appl Math Model. 2014;38(13):3154–63.10.1016/j.apm.2013.11.035Search in Google Scholar

[24] Kumar S, Rashidi MM. New analytical method for gas dynamics equation arising in shock fronts. Comput Phys Commun. 2014;185(7):1947–54.10.1016/j.cpc.2014.03.025Search in Google Scholar

[25] Kumar S, Kumar A, Baleanu D. Two analytical methods for time-fractional nonlinear coupled Boussinesq–Burger’s equations arise in propagation of shallow water waves. Nonlinear Dyn. 2016;85(2):699–715.10.1007/s11071-016-2716-2Search in Google Scholar

[26] Ghanbari B, Kumar S, Kumar R. A study of behaviour for immune and tumor cells in immunogenetic tumour model with non-singular fractional derivative. Chaos Solitons Fractals. 2020;133:109619.10.1016/j.chaos.2020.109619Search in Google Scholar

[27] Goufo EFD, Kumar S, Mugisha SB. Similarities in a fifth-order evolution equation with and with no singular kernel. Chaos Solitons Fractals. 2020;130:109467.10.1016/j.chaos.2019.109467Search in Google Scholar

[28] Shafiq A, Hammouch Z, Sindhu TN. Bioconvective MHD flow of tangent hyperbolic nanofluid with newtonian heating. Int J Mech Sci. 2017;133:759–66.10.1016/j.ijmecsci.2017.07.048Search in Google Scholar

[29] Ilhan OA, Manafian J, Alizadeh AA, Baskonus HM. New exact solutions for nematicons in liquid crystals by the (ϕ/2)-expansion method arising in fluid mechanics. Eur Phys J Plus. 2020;135(3):1–19.10.1140/epjp/s13360-020-00296-wSearch in Google Scholar

[30] Basha HT, Sivaraj R, Reddy AS, Chamkha AJ, Baskonus HM. A numerical study of the ferromagnetic flow of Carreau nanofluid over a wedge, plate and stagnation point with a magnetic dipole. AIMS Math. 2020;5(5):4197.10.3934/math.2020268Search in Google Scholar

[31] Baskonus HM. New acoustic wave behaviors to the Davey-Stewartson equation with power-law nonlinearity arising in fluid dynamics. Nonlinear Dyn. 2016;86(1):177–83.10.1007/s11071-016-2880-4Search in Google Scholar

[32] Guedda M, Hammouch Z. Similarity flow solutions of a non-Newtonian power-law fluid. arXiv Prepr arXiv. 2009;904:315.Search in Google Scholar

[33] Ahmad H, Khan TA, Ahmad I, Stanimirović PS, Chu Y-M. A new analyzing technique for nonlinear time fractional Cauchy reaction-diffusion model equations. Results Phys. 2020;19:103462. 10.1016/j.rinp.2020.103462.Search in Google Scholar

[34] Ahmad H, Akgül A, Khan TA, Stanimirović PS, Chu Y-M. New perspective on the conventional solutions of the nonlinear time-fractional partial differential equations. Complexity. 2020;2020:8829017. 10.1155/2020/8829017.Search in Google Scholar

[35] Ahmad H, Khan TA, Stanimirović PS, Chu Y-M, Ahmad I. Modified variational iteration algorithm-II: convergence and applications to diffusion models. Complexity. 2020;2020:8841718. 10.1155/2020/8841718.Search in Google Scholar

[36] Ahmad H, Seadawy AR, Khan TA, Thounthong P. Analytic approximate solutions for some nonlinear parabolic dynamical wave equations. J Taibah Univ Sci. 2020;14(1):346–58.10.1080/16583655.2020.1741943Search in Google Scholar

[37] Menni Y, Azzi A, Zidani C. Numerical study of heat transfer and fluid flow in a channel with staggered arc-shaped baffles. Commun Sci Technol. 2017;18:43–57.Search in Google Scholar

[38] Menni Y, Azzi Y. Design and performance evaluation of air solar channels with diverse baffle structures. Comput Therm Sci. 2018;10(3):225–49.10.1615/ComputThermalScien.2018025026Search in Google Scholar

[39] Menni Y, Chamkha AJ, Azzi A, Zidani C, Benyoucef B. Study of air flow around flat and arc-shaped baffles in shell-and-tube heat exchangers. Math Model Eng Probl. 2019;6(1):77–84.10.18280/mmep.060110Search in Google Scholar

[40] Menni Y, Azzi A, Chamkha AJ. Developing heat transfer in a solar air channel with arc-shaped baffles: effect of baffle attack angle. J New Technol Mater. 2018;8(1):58–67.10.12816/0048925Search in Google Scholar

[41] Menni Y, Azzi A, Chamkha AJ. The solar air channels: comparative analysis, introduction of arc-shaped fins to improve the thermal transfer. J Appl Comput Mech. 2019;5(4):616–26.Search in Google Scholar

[42] Menni Y, Azzi A, Chamkha A. Modeling and analysis of solar air channels with attachments of different shapes. Int J Numer Methods Heat Fluid Flow. 2018;29:1815. 10.1108/HFF-08-2018-0435.Search in Google Scholar

[43] Demartini LC, Vielmo HA, Möller SV. Numeric and experimental analysis of the turbulent flow through a channel with baffle plates. J Braz Soc Mech Sci Eng. 2004;26(2):153–9.10.1590/S1678-58782004000200006Search in Google Scholar

[44] Launder BE, Spalding DB. The numerical computation of turbulent flows. Comput Methods Appl Mech Eng. 1974;3:269–89.10.1016/B978-0-08-030937-8.50016-7Search in Google Scholar

[45] Menni Y, Ghazvini M, Ameur H, Kim M, Ahmadi MH, Sharifpur M. Combination of baffling technique and high-thermal conductivity fluids to enhance the overall performances of solar channels. Eng Comput. 2020. 10.1007/s00366-020-01165-x Search in Google Scholar

[46] Patankar SV. Numerical heat transfer and fluid flow. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 1980.Search in Google Scholar

[47] Leonard BP, Mokhtari S. Ultra-sharp nonoscillatory convection schemes for high-speed steady multidimensional flow. Cleveland, OH: NASA Lewis Research Center; 1990. NASA TM 1-2568.Search in Google Scholar

[48] Dittus FW, Boelter LMK. Heat transfer in automobile radiators of tubular type. Univ Calif Berkeley Publ Eng. 1930;1(13):755–8.10.1016/0735-1933(85)90003-XSearch in Google Scholar

[49] Petukhov BS. Heat transfer in turbulent pipe flow with variable physical properties. In: Harnett JP, ed., Advances in heat transfer, vol. 6. New York: Academic Press; 1970. p. 504–64.10.1016/S0065-2717(08)70153-9Search in Google Scholar

© 2021 Younes Menni et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- Circular Rydberg states of helium atoms or helium-like ions in a high-frequency laser field

- Closed-form solutions and conservation laws of a generalized Hirota–Satsuma coupled KdV system of fluid mechanics

- W-Chirped optical solitons and modulation instability analysis of Chen–Lee–Liu equation in optical monomode fibres

- The problem of a hydrogen atom in a cavity: Oscillator representation solution versus analytic solution

- An analytical model for the Maxwell radiation field in an axially symmetric galaxy

- Utilization of updated version of heat flux model for the radiative flow of a non-Newtonian material under Joule heating: OHAM application

- Verification of the accommodative responses in viewing an on-axis analog reflection hologram

- Irreversibility as thermodynamic time

- A self-adaptive prescription dose optimization algorithm for radiotherapy

- Algebraic computational methods for solving three nonlinear vital models fractional in mathematical physics

- The diffusion mechanism of the application of intelligent manufacturing in SMEs model based on cellular automata

- Numerical analysis of free convection from a spinning cone with variable wall temperature and pressure work effect using MD-BSQLM

- Numerical simulation of hydrodynamic oscillation of side-by-side double-floating-system with a narrow gap in waves

- Closed-form solutions for the Schrödinger wave equation with non-solvable potentials: A perturbation approach

- Study of dynamic pressure on the packer for deep-water perforation

- Ultrafast dephasing in hydrogen-bonded pyridine–water mixtures

- Crystallization law of karst water in tunnel drainage system based on DBL theory

- Position-dependent finite symmetric mass harmonic like oscillator: Classical and quantum mechanical study

- Application of Fibonacci heap to fast marching method

- An analytical investigation of the mixed convective Casson fluid flow past a yawed cylinder with heat transfer analysis

- Considering the effect of optical attenuation on photon-enhanced thermionic emission converter of the practical structure

- Fractal calculation method of friction parameters: Surface morphology and load of galvanized sheet

- Charge identification of fragments with the emulsion spectrometer of the FOOT experiment

- Quantization of fractional harmonic oscillator using creation and annihilation operators

- Scaling law for velocity of domino toppling motion in curved paths

- Frequency synchronization detection method based on adaptive frequency standard tracking

- Application of common reflection surface (CRS) to velocity variation with azimuth (VVAz) inversion of the relatively narrow azimuth 3D seismic land data

- Study on the adaptability of binary flooding in a certain oil field

- CompVision: An open-source five-compartmental software for biokinetic simulations

- An electrically switchable wideband metamaterial absorber based on graphene at P band

- Effect of annealing temperature on the interface state density of n-ZnO nanorod/p-Si heterojunction diodes

- A facile fabrication of superhydrophobic and superoleophilic adsorption material 5A zeolite for oil–water separation with potential use in floating oil

- Shannon entropy for Feinberg–Horodecki equation and thermal properties of improved Wei potential model

- Hopf bifurcation analysis for liquid-filled Gyrostat chaotic system and design of a novel technique to control slosh in spacecrafts

- Optical properties of two-dimensional two-electron quantum dot in parabolic confinement

- Optical solitons via the collective variable method for the classical and perturbed Chen–Lee–Liu equations

- Stratified heat transfer of magneto-tangent hyperbolic bio-nanofluid flow with gyrotactic microorganisms: Keller-Box solution technique

- Analysis of the structure and properties of triangular composite light-screen targets

- Magnetic charged particles of optical spherical antiferromagnetic model with fractional system

- Study on acoustic radiation response characteristics of sound barriers

- The tribological properties of single-layer hybrid PTFE/Nomex fabric/phenolic resin composites underwater

- Research on maintenance spare parts requirement prediction based on LSTM recurrent neural network

- Quantum computing simulation of the hydrogen molecular ground-state energies with limited resources

- A DFT study on the molecular properties of synthetic ester under the electric field

- Construction of abundant novel analytical solutions of the space–time fractional nonlinear generalized equal width model via Riemann–Liouville derivative with application of mathematical methods

- Some common and dynamic properties of logarithmic Pareto distribution with applications

- Soliton structures in optical fiber communications with Kundu–Mukherjee–Naskar model

- Fractional modeling of COVID-19 epidemic model with harmonic mean type incidence rate

- Liquid metal-based metamaterial with high-temperature sensitivity: Design and computational study

- Biosynthesis and characterization of Saudi propolis-mediated silver nanoparticles and their biological properties

- New trigonometric B-spline approximation for numerical investigation of the regularized long-wave equation

- Modal characteristics of harmonic gear transmission flexspline based on orthogonal design method

- Revisiting the Reynolds-averaged Navier–Stokes equations

- Time-periodic pulse electroosmotic flow of Jeffreys fluids through a microannulus

- Exact wave solutions of the nonlinear Rosenau equation using an analytical method

- Computational examination of Jeffrey nanofluid through a stretchable surface employing Tiwari and Das model

- Numerical analysis of a single-mode microring resonator on a YAG-on-insulator

- Review Articles

- Double-layer coating using MHD flow of third-grade fluid with Hall current and heat source/sink

- Analysis of aeromagnetic filtering techniques in locating the primary target in sedimentary terrain: A review

- Rapid Communications

- Nonlinear fitting of multi-compartmental data using Hooke and Jeeves direct search method

- Effect of buried depth on thermal performance of a vertical U-tube underground heat exchanger

- Knocking characteristics of a high pressure direct injection natural gas engine operating in stratified combustion mode

- What dominates heat transfer performance of a double-pipe heat exchanger

- Special Issue on Future challenges of advanced computational modeling on nonlinear physical phenomena - Part II

- Lump, lump-one stripe, multiwave and breather solutions for the Hunter–Saxton equation

- New quantum integral inequalities for some new classes of generalized ψ-convex functions and their scope in physical systems

- Computational fluid dynamic simulations and heat transfer characteristic comparisons of various arc-baffled channels

- Gaussian radial basis functions method for linear and nonlinear convection–diffusion models in physical phenomena

- Investigation of interactional phenomena and multi wave solutions of the quantum hydrodynamic Zakharov–Kuznetsov model

- On the optical solutions to nonlinear Schrödinger equation with second-order spatiotemporal dispersion

- Analysis of couple stress fluid flow with variable viscosity using two homotopy-based methods

- Quantum estimates in two variable forms for Simpson-type inequalities considering generalized Ψ-convex functions with applications

- Series solution to fractional contact problem using Caputo’s derivative

- Solitary wave solutions of the ionic currents along microtubule dynamical equations via analytical mathematical method

- Thermo-viscoelastic orthotropic constraint cylindrical cavity with variable thermal properties heated by laser pulse via the MGT thermoelasticity model

- Theoretical and experimental clues to a flux of Doppler transformation energies during processes with energy conservation

- On solitons: Propagation of shallow water waves for the fifth-order KdV hierarchy integrable equation

- Special Issue on Transport phenomena and thermal analysis in micro/nano-scale structure surfaces - Part II

- Numerical study on heat transfer and flow characteristics of nanofluids in a circular tube with trapezoid ribs

- Experimental and numerical study of heat transfer and flow characteristics with different placement of the multi-deck display cabinet in supermarket

- Thermal-hydraulic performance prediction of two new heat exchangers using RBF based on different DOE

- Diesel engine waste heat recovery system comprehensive optimization based on system and heat exchanger simulation

- Load forecasting of refrigerated display cabinet based on CEEMD–IPSO–LSTM combined model

- Investigation on subcooled flow boiling heat transfer characteristics in ICE-like conditions

- Research on materials of solar selective absorption coating based on the first principle

- Experimental study on enhancement characteristics of steam/nitrogen condensation inside horizontal multi-start helical channels

- Special Issue on Novel Numerical and Analytical Techniques for Fractional Nonlinear Schrodinger Type - Part I

- Numerical exploration of thin film flow of MHD pseudo-plastic fluid in fractional space: Utilization of fractional calculus approach

- A Haar wavelet-based scheme for finding the control parameter in nonlinear inverse heat conduction equation

- Stable novel and accurate solitary wave solutions of an integrable equation: Qiao model

- Novel soliton solutions to the Atangana–Baleanu fractional system of equations for the ISALWs

- On the oscillation of nonlinear delay differential equations and their applications

- Abundant stable novel solutions of fractional-order epidemic model along with saturated treatment and disease transmission

- Fully Legendre spectral collocation technique for stochastic heat equations

- Special Issue on 5th International Conference on Mechanics, Mathematics and Applied Physics (2021)

- Residual service life of erbium-modified AM50 magnesium alloy under corrosion and stress environment

- Special Issue on Advanced Topics on the Modelling and Assessment of Complicated Physical Phenomena - Part I

- Diverse wave propagation in shallow water waves with the Kadomtsev–Petviashvili–Benjamin–Bona–Mahony and Benney–Luke integrable models

- Intensification of thermal stratification on dissipative chemically heating fluid with cross-diffusion and magnetic field over a wedge

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- Circular Rydberg states of helium atoms or helium-like ions in a high-frequency laser field

- Closed-form solutions and conservation laws of a generalized Hirota–Satsuma coupled KdV system of fluid mechanics

- W-Chirped optical solitons and modulation instability analysis of Chen–Lee–Liu equation in optical monomode fibres

- The problem of a hydrogen atom in a cavity: Oscillator representation solution versus analytic solution

- An analytical model for the Maxwell radiation field in an axially symmetric galaxy

- Utilization of updated version of heat flux model for the radiative flow of a non-Newtonian material under Joule heating: OHAM application

- Verification of the accommodative responses in viewing an on-axis analog reflection hologram

- Irreversibility as thermodynamic time

- A self-adaptive prescription dose optimization algorithm for radiotherapy

- Algebraic computational methods for solving three nonlinear vital models fractional in mathematical physics

- The diffusion mechanism of the application of intelligent manufacturing in SMEs model based on cellular automata

- Numerical analysis of free convection from a spinning cone with variable wall temperature and pressure work effect using MD-BSQLM

- Numerical simulation of hydrodynamic oscillation of side-by-side double-floating-system with a narrow gap in waves

- Closed-form solutions for the Schrödinger wave equation with non-solvable potentials: A perturbation approach

- Study of dynamic pressure on the packer for deep-water perforation

- Ultrafast dephasing in hydrogen-bonded pyridine–water mixtures

- Crystallization law of karst water in tunnel drainage system based on DBL theory

- Position-dependent finite symmetric mass harmonic like oscillator: Classical and quantum mechanical study

- Application of Fibonacci heap to fast marching method

- An analytical investigation of the mixed convective Casson fluid flow past a yawed cylinder with heat transfer analysis

- Considering the effect of optical attenuation on photon-enhanced thermionic emission converter of the practical structure

- Fractal calculation method of friction parameters: Surface morphology and load of galvanized sheet

- Charge identification of fragments with the emulsion spectrometer of the FOOT experiment

- Quantization of fractional harmonic oscillator using creation and annihilation operators

- Scaling law for velocity of domino toppling motion in curved paths

- Frequency synchronization detection method based on adaptive frequency standard tracking

- Application of common reflection surface (CRS) to velocity variation with azimuth (VVAz) inversion of the relatively narrow azimuth 3D seismic land data

- Study on the adaptability of binary flooding in a certain oil field

- CompVision: An open-source five-compartmental software for biokinetic simulations

- An electrically switchable wideband metamaterial absorber based on graphene at P band

- Effect of annealing temperature on the interface state density of n-ZnO nanorod/p-Si heterojunction diodes

- A facile fabrication of superhydrophobic and superoleophilic adsorption material 5A zeolite for oil–water separation with potential use in floating oil

- Shannon entropy for Feinberg–Horodecki equation and thermal properties of improved Wei potential model

- Hopf bifurcation analysis for liquid-filled Gyrostat chaotic system and design of a novel technique to control slosh in spacecrafts

- Optical properties of two-dimensional two-electron quantum dot in parabolic confinement

- Optical solitons via the collective variable method for the classical and perturbed Chen–Lee–Liu equations

- Stratified heat transfer of magneto-tangent hyperbolic bio-nanofluid flow with gyrotactic microorganisms: Keller-Box solution technique

- Analysis of the structure and properties of triangular composite light-screen targets

- Magnetic charged particles of optical spherical antiferromagnetic model with fractional system

- Study on acoustic radiation response characteristics of sound barriers

- The tribological properties of single-layer hybrid PTFE/Nomex fabric/phenolic resin composites underwater

- Research on maintenance spare parts requirement prediction based on LSTM recurrent neural network

- Quantum computing simulation of the hydrogen molecular ground-state energies with limited resources

- A DFT study on the molecular properties of synthetic ester under the electric field

- Construction of abundant novel analytical solutions of the space–time fractional nonlinear generalized equal width model via Riemann–Liouville derivative with application of mathematical methods

- Some common and dynamic properties of logarithmic Pareto distribution with applications

- Soliton structures in optical fiber communications with Kundu–Mukherjee–Naskar model

- Fractional modeling of COVID-19 epidemic model with harmonic mean type incidence rate

- Liquid metal-based metamaterial with high-temperature sensitivity: Design and computational study

- Biosynthesis and characterization of Saudi propolis-mediated silver nanoparticles and their biological properties

- New trigonometric B-spline approximation for numerical investigation of the regularized long-wave equation

- Modal characteristics of harmonic gear transmission flexspline based on orthogonal design method

- Revisiting the Reynolds-averaged Navier–Stokes equations

- Time-periodic pulse electroosmotic flow of Jeffreys fluids through a microannulus

- Exact wave solutions of the nonlinear Rosenau equation using an analytical method

- Computational examination of Jeffrey nanofluid through a stretchable surface employing Tiwari and Das model

- Numerical analysis of a single-mode microring resonator on a YAG-on-insulator

- Review Articles

- Double-layer coating using MHD flow of third-grade fluid with Hall current and heat source/sink

- Analysis of aeromagnetic filtering techniques in locating the primary target in sedimentary terrain: A review

- Rapid Communications

- Nonlinear fitting of multi-compartmental data using Hooke and Jeeves direct search method

- Effect of buried depth on thermal performance of a vertical U-tube underground heat exchanger

- Knocking characteristics of a high pressure direct injection natural gas engine operating in stratified combustion mode

- What dominates heat transfer performance of a double-pipe heat exchanger

- Special Issue on Future challenges of advanced computational modeling on nonlinear physical phenomena - Part II

- Lump, lump-one stripe, multiwave and breather solutions for the Hunter–Saxton equation

- New quantum integral inequalities for some new classes of generalized ψ-convex functions and their scope in physical systems

- Computational fluid dynamic simulations and heat transfer characteristic comparisons of various arc-baffled channels

- Gaussian radial basis functions method for linear and nonlinear convection–diffusion models in physical phenomena

- Investigation of interactional phenomena and multi wave solutions of the quantum hydrodynamic Zakharov–Kuznetsov model

- On the optical solutions to nonlinear Schrödinger equation with second-order spatiotemporal dispersion

- Analysis of couple stress fluid flow with variable viscosity using two homotopy-based methods

- Quantum estimates in two variable forms for Simpson-type inequalities considering generalized Ψ-convex functions with applications

- Series solution to fractional contact problem using Caputo’s derivative

- Solitary wave solutions of the ionic currents along microtubule dynamical equations via analytical mathematical method

- Thermo-viscoelastic orthotropic constraint cylindrical cavity with variable thermal properties heated by laser pulse via the MGT thermoelasticity model

- Theoretical and experimental clues to a flux of Doppler transformation energies during processes with energy conservation

- On solitons: Propagation of shallow water waves for the fifth-order KdV hierarchy integrable equation

- Special Issue on Transport phenomena and thermal analysis in micro/nano-scale structure surfaces - Part II

- Numerical study on heat transfer and flow characteristics of nanofluids in a circular tube with trapezoid ribs

- Experimental and numerical study of heat transfer and flow characteristics with different placement of the multi-deck display cabinet in supermarket

- Thermal-hydraulic performance prediction of two new heat exchangers using RBF based on different DOE

- Diesel engine waste heat recovery system comprehensive optimization based on system and heat exchanger simulation

- Load forecasting of refrigerated display cabinet based on CEEMD–IPSO–LSTM combined model

- Investigation on subcooled flow boiling heat transfer characteristics in ICE-like conditions

- Research on materials of solar selective absorption coating based on the first principle

- Experimental study on enhancement characteristics of steam/nitrogen condensation inside horizontal multi-start helical channels

- Special Issue on Novel Numerical and Analytical Techniques for Fractional Nonlinear Schrodinger Type - Part I

- Numerical exploration of thin film flow of MHD pseudo-plastic fluid in fractional space: Utilization of fractional calculus approach

- A Haar wavelet-based scheme for finding the control parameter in nonlinear inverse heat conduction equation

- Stable novel and accurate solitary wave solutions of an integrable equation: Qiao model

- Novel soliton solutions to the Atangana–Baleanu fractional system of equations for the ISALWs

- On the oscillation of nonlinear delay differential equations and their applications

- Abundant stable novel solutions of fractional-order epidemic model along with saturated treatment and disease transmission

- Fully Legendre spectral collocation technique for stochastic heat equations

- Special Issue on 5th International Conference on Mechanics, Mathematics and Applied Physics (2021)

- Residual service life of erbium-modified AM50 magnesium alloy under corrosion and stress environment

- Special Issue on Advanced Topics on the Modelling and Assessment of Complicated Physical Phenomena - Part I

- Diverse wave propagation in shallow water waves with the Kadomtsev–Petviashvili–Benjamin–Bona–Mahony and Benney–Luke integrable models

- Intensification of thermal stratification on dissipative chemically heating fluid with cross-diffusion and magnetic field over a wedge