Agronomic and economic benefits of rice–sweetpotato rotation in lowland rice cropping systems in Uganda

-

Gerald Kyalo

, Simon Alibu

Abstract

A crop rotation study was conducted in the Agoro Rice scheme from mid-2015 to 2017 to determine the effect of sweetpotato–rice rotation in the lowlands on financial returns and sweetpotato root, sweetpotato vine, and rice yields compared to monocropping. Treatments included crop rotations of sweetpotato–rice–sweetpotato, rice–sweetpotato–rice, rice–rice–rice (control), and sweetpotato–sweetpotato–sweetpotato (control). The study used the sweetpotato varieties NASPOT 11 (cream-fleshed), NASPOT 10 O, and Ejumula (both orange-fleshed) and the rice varieties Wita 9, Agoro, and Komboka. The results showed that mean sweetpotato root yields in the rotation treatment were significantly higher (28 t ha−1) than the control (19.8 t ha−1), representing a 47% gain in yield. Generally, the percentage gain in yield across years due to rotation ranged from 3 to 132%, depending on the variety. The total number of vine cuttings was significantly different between treatments and seasons (P < 0.001). Mean rice paddy yields in rotation were 8–35% higher than the control. The higher yields of sweetpotato in the rotation can be attributed to the rotation crop benefitting from residual fertilizers applied in rice in the previous season, while rice in the rotation crop could have benefited from the land preparation and establishment of the sweetpotato fields. The benefit of rotation for both crops varied by variety while the revenue-to-cost ratio varied by season and crop variety. Revenue-to-cost ratios for rotation and control treatments were greater than 1, indicating net profits were positive for both. The rotation generated 0.43 times more revenue than rice monocropping. Both rotation and monocropping systems generated profits, but rotation was 43% more profitable. In other words, if monocropping generates 1 dollar, rotation generates 1.43 dollars. The study concludes that rotation of sweetpotato with rice led to (1) increased yields of both rice and sweetpotatoes, (2) more profitable utilization of land, (3) enhanced availability of sweetpotato planting material at the beginning of the upland growing season, and (4) reduced the cost of land preparation for the main rice crop. Findings from this study show that there is great potential for diversification of rice-based cropping systems in Uganda, which will contribute to building sustainable food systems.

1 Introduction

Sweetpotato (Ipomoea batatas L.) is a primary staple in the East and Central African region, with per capita consumption ranging from 35 kg per year to more than 80 kg per year [1]. In Uganda, sweetpotato is grown country-wide for its storage roots, which are used for household consumption and small-scale trading [2]. Sweetpotato is widely grown in Uganda because it is highly adaptable and tolerates high temperatures, low soil fertility, and drought [3]. Annual sweetpotato production in 2022 stood at 1,543,000 MT produced on 309,000 ha of land [4]. The Eastern region leads in annual sweetpotato production with 847,140 metric tons (MT) produced in 2018, followed by the western, central, and northern regions, with 366,295, 312,402, and 292,932 MT, respectively. The average sweetpotato production area per household in Uganda ranges from 0.53 to 0.81 acres [5,6].

Increased production and productivity of sweetpotato in SSA faces a number of constraints, both abiotic and biotic. Abiotic constraints include drought or weather extremes and low soil fertility, while serious biotic constraints include viruses, mainly sweetpotato virus disease (SPVD), fungal diseases, mainly Alternaria bataticola blight, and sweetpotato weevils [7]. Other constraints to sweetpotato production include poor access to quality seed-vines of suitable varieties and poor agronomic management practices by farmers that, in turn, affect yield, food availability, and income for households. Improving sweetpotato production requires a supply of and access to good quality seed-vines, accompanied by improvements in plant nutrition and disease and post-harvest management [8].

Despite the lower overall production of sweetpotato in northern Uganda where the rainfall pattern is unimodal, it is a key food-security crop in this region. The key limitation for increasing sweetpotato production in the region is the lack of sufficient quality planting material at the beginning of the first season’s rain in March, caused by the long dry season from December through February, during which vines (the planting material for this vegetatively propagated crop) have desiccated [9]. As a result, farmers are left with no option but to borrow from neighbours, who have planting materials or buy vine cuttings from commercial vine multipliers/suppliers at a higher price. For example, vine suppliers in the Gulu district are reported to provide vine cuttings to smallholders in the surrounding districts of Nwoya, Amuru, Lamwo, Pader, Lira, and Oyam.

Rice (Oryza sativa L.), on the other hand, has emerged as a critical food staple and a major source of income for many Ugandans [10]. About 80% of the rice farmers in Uganda are small-scale, farming less than 2 ha of land using basic labour-intensive tools and techniques, with limited access to irrigation, struggling with poor water management [10], and hardly using any fertilizers. Domestic paddy production is expected to rise from 320,000 tons in 2020 to 700,000 tons in 2026. It is now the second most-produced cereal after maize and is increasingly favoured over traditional staples such as bananas and millet by Ugandans, particularly among the youth, who make up 78% of the population because it is easier to cook and eat. More than 90% of the national rice output of Uganda is produced by smallholder farmers in Eastern and Northern Uganda under rainfed and irrigated rice systems [11]. In Northern Uganda, irrigated and rainfed lowland rice is planted only once a year during the first season, from March to June. The lowland is then left to fallow until the next year’s planting season (Figure 1), as there is insufficient water to irrigate a high-yielding, water-intensive rice crop.

Typical lowland rice field develops hard pans under fallow after harvesting first season rice crop. Source: G. Kyalo.

During the fallow period, the fields are used for grazing animals. The resultant hardpans make land preparation for the next rice-crop an arduous task. The fallow period in the lowland rice fields coincides, in part, with the long dry season when sweetpotato vines desiccate in upland fields.

In this study, we postulate that the use of lowland rice fields could be optimized by utilizing the fallow period following the main rice season to grow sweetpotato. Sweetpotato is known for being able to produce a good crop with residual moisture that is insufficient for rice, pulses, and oil seed crops [12]. Moreover, vines from the post-rotation between rice and sweetpotato crops could potentially serve as a source of planting material for farmers in Northern Uganda, other regions of the country, and even southern Sudan, hence mitigating the typical shortage of planting material after the long dry season [13], with vine sales potentially providing a source of income. In addition, sweetpotato root and leaf production from a dry season crop could also serve as much-needed nutritional food sources at the end of the dry season when household food stocks are typically depleted.

Although crop rotations of sweetpotato with crops other than rice are common in upland farming systems of Uganda, rotation of sweetpotato in lowland rice systems is not frequently practiced by farmers. However, results from Vietnam indicated that rotation of lowland rice with sweetpotato increased rice yield and nitrogen-use efficiency of rice [14]. When rice followed sweetpotato in the rotation, the nutrient-use efficiency (NUE) of rice increased from 19% (NUE of rice following rice) to 29%. Moreover, the cultivation of sweetpotato improved the physical, chemical, and biological properties of soil, which benefited the rice crop that followed.

The potential advantages of rotating sweetpotato and rice have not been adequately explored and documented in Uganda. The major objective of this study was to explore the potential of growing sweetpotato as an alternative to leaving lowland rice fields fallow. The study was specifically designed to (a) assess the influence of crop rotation on yields of paddy rice and sweetpotato vines and roots; (b) evaluate the revenue-to-cost ratio for the rotation (sweetpotato–rice) versus monocropping options (rice–rice and sweetpotato–sweetpotato), and (c) explore whether rotation would enable the timely supply of basic sweetpotato “seed” (cuttings) to decentralized multipliers, root producers, and improve access of farmers in or near the rice scheme to the seed of newly released rice varieties.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Study sites

The experiment was set up in the Agoro irrigation scheme located in Pobar Parish, Agoro Subcounty, Lamwo district, northern Uganda, in collaboration with the Tutte Laco Laco (TULA) Youth group participating in the scheme (Figure 2).

Experimental plot of rice–sweetpotato rotation. Source: S. Rajendran.

The scheme is located at latitude 3°48′0.7415″N3.800206, longitude 33°1′3.7488″E.017708, and 1,130 m above sea level [15]. Covering a total area of 745 ha, the soils in the scheme are dominated by gleysols. Gleysols are wetland soils known for being continuously water‐saturated for long periods, with the water table being 50 cm below the soil surface. This leads to reduced iron and manganese content, causing the predominantly greyish hues in the profile below the water table. Agoro receives unimodal rains, averaging 1,300 mm annually, stretching from mid-March to October, with a peak in April. Average temperatures range from 17 to 30°C. Soils from the experimental area were sampled and analysed at the National Agricultural Research Organization (NARO)-National Agriculture Research Laboratory, Kawanda, Uganda, for acidity (pH), total carbon, total nitrogen, available phosphorus (P), and exchangeable calcium (Ca), magnesium (Mg), and potassium (K) according to Okalebo et al. [16]. Soil pH was measured in a soil–water solution in a ratio of 1:2.5; the organic matter was determined via potassium dichromate wet acid oxidation (Walkley and Black method). Total N was determined by Kjeldahl digestion; extractable P by the Bray P1 method; K+ and Na+ from an ammonium acetate extract by flame photometry and Ca2+ and Mg2+ by atomic absorption spectrophotometry. Particle size distribution (texture) was determined using the Bouyoucos (hydrometer) method [16].

2.2 Crop materials

The study used three released sweetpotato varieties, two being orange-fleshed (Ejumula and NASPOT 10 O (Kabode)) and NASPOT 11 (cream-fleshed); and three rice varieties, viz., Wita 9, Komboka, and Agoro (Table 1).

Plant materials used in the study

| Crop | Variety | Attributes |

|---|---|---|

| Sweetpotato | Ejumula (orange-fleshed sweetpotato (OFSP)) |

|

| NASPOT 10 O/Kabode (OFSP) |

|

|

| NASPOT 11 (cream-fleshed sweetpotato) |

|

|

| Rice | Wita 9 |

|

| Komboka |

|

|

| Agoro |

|

O refers to orange fleshed.

The initial pre-basic sweetpotato planting material was sourced from the BioCrops private tissue culture laboratory located in Uganda, whereas rice seed was provided by the rice breeder at the National Crops Resource Research Institute, Uganda. Sweetpotato seed, cuttings (pieces of vine 20–30 cm long), and planting material are used interchangeably in this article. There are four categories of seed recognized internationally, viz., breeder’s seed, pre-basic, basic, and quality declared seed (QDS). Both pre-basic (also referred to as foundation) and basic seed are part of early generation seed. Pre-basic seed is grown in screen houses and comprises cuttings from plants sourced from tissue culture plantlets tested for pathogens, and basic seed is sourced from pre-basic cuttings and produced in open multiplication fields [21]. However, in Uganda, pre-basic seed is designated as basic seed, and basic seed is referred to as certified 1 (C1), and further multiplication of C1 produces certified 2 (C2) seed. Both C1 and C2 are sold or provided to root producers for root production. They can also be further multiplied as QDS and then sold or provided to other root producers.

2.3 Treatments, trial design, and field layout

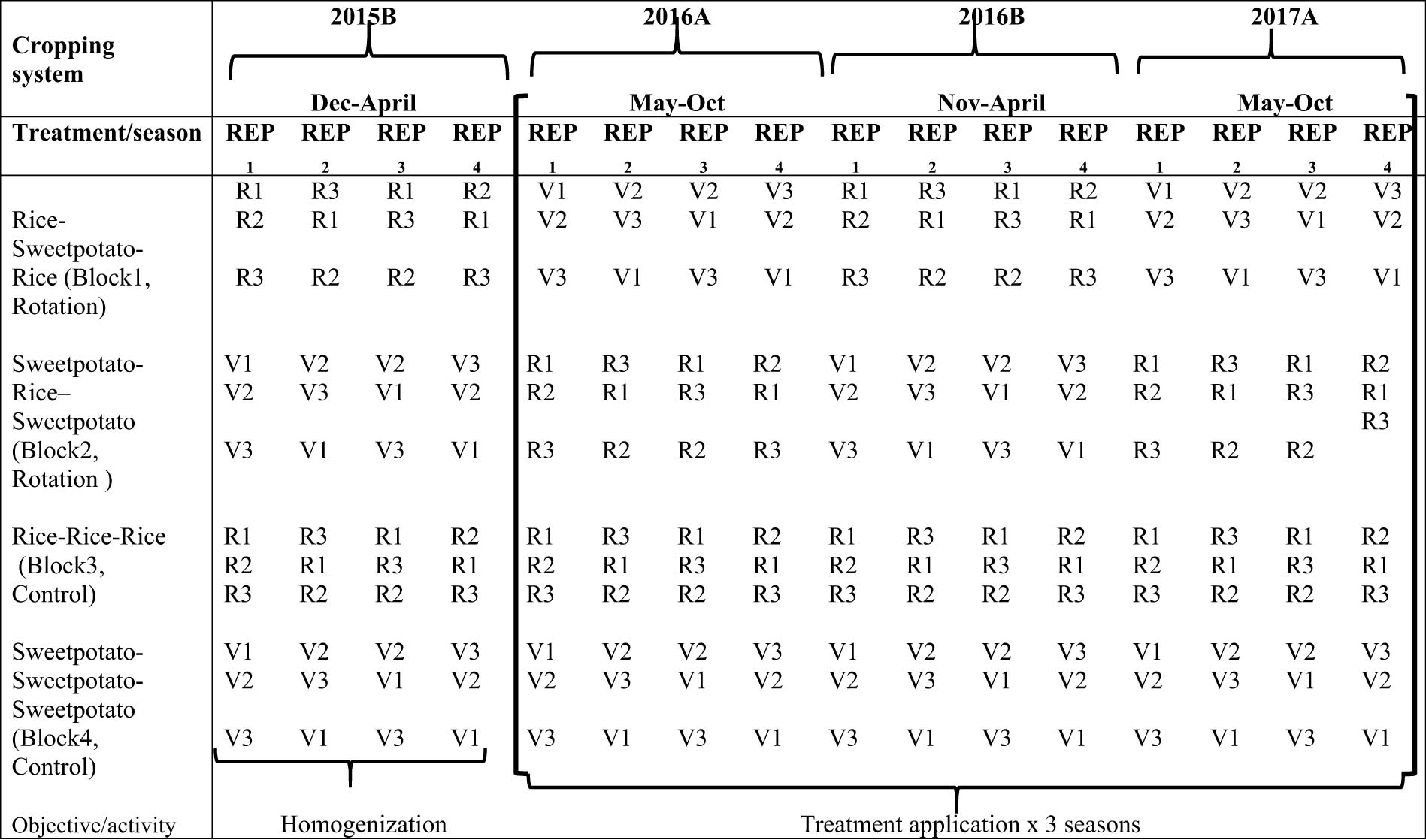

The field experiment was initiated at the onset of the long dry season in December 2015, and rotation trials were conducted for the next three seasons: 2016A, 2016B, and 2017A (A refers to first and B refers to the second rainy season). The experiment was set-up as a split-plot design, and cropping sequences were assigned randomly to main plots and crop varieties to sub-plots within the main plots. The treatments were replicated four times (Table 2).

Experimental layout of the rotation treatments in each season, 2015–2017

|

V: sweetpotato, R: rice.

Data source: experiment, 2015–2017.

The size of the main plots was 20 m × 23 m, separated by 2 m alleyways, whereas the sub-plots measured 6 m × 5 m, which were separated by 1 m alleyways. The land was prepared using a tractor, and fields levelled manually using hand hoes. Disease-free sweetpotato cuttings, each 30-cm long, were planted on mounds spaced 1 m × 1 m and three vine cuttings per mound. Rice seedlings were raised in a nursery and transplanted after 3 weeks into the plots. Three seedlings were transplanted per hill at a spacing of 25 cm × 25 cm. The experiment was irrigated every 2 weeks for 30–60 min during dry spells using water from the irrigation scheme. Efforts were made to ensure that each plot received water during the time of irrigation. The rotation crop was planted each time after the harvest of the previous crop. Weeds were controlled manually by weeding 3–4 times at 3-week intervals during the growing season. Fertilizer was applied to the rice crop both in the rotation and control sub-plots at a rate of 30:30:30 kg nitrogen–phosphorus–potassium (NPK) ha−1 at planting and then 30:0:0 kg NPK ha−1 at panicle initiation. No fertilizer was applied in the sweetpotato crop. Two persons were hired to scare away birds from the rice plots from the time of heading (the panicle is fully visible) until harvest.

2.4 Data collection and analysis

Data were collected on the incidence and severity of SPVD (Figure 3a) and Alternaria stem blight (ASB) (Figure 3b), weevil infestation, and root and vine weight at harvest in sweetpotato. Data on SPVD and ASB were collected 1 month after planting and 1 month before harvesting. Disease incidence was recorded using a scale of 1–9, where 1 = no disease symptoms and 9 = severe symptoms on all plants. Weevil infestation was also recorded at harvest on a scale of 1–9, where 1 = no infestation and 9 = most severe infestation [18]. Root and vine yields were assessed from a 10 m2 net sub-plot, which was randomly determined and expressed as tons per hectare. The number of 30 cm vine cuttings harvested per plot was also recorded.

(a) Sweetpotato plant showing symptoms of SPVD. (b) Sweetpotato plant showing symptoms of ASB. Source: G. Kyalo.

Data were collected on rice yield at harvest and the percent grain moisture content was determined with a moisture meter. Rice grain obtained from a central 5 m2 harvested area in each plot was then adjusted to a 14% moisture content. Data were checked for normality and homoscedasticity and transformed as needed to meet the assumptions of analysis of variance (ANOVA). Data were analysed as a split-plot design in a randomized complete block design using a general linear model for ANOVA in the Genstat 12th edition software. During analysis, the rotations were randomly assigned to the main/whole plots, while the varieties were assigned to the small/sub-plots. Separate randomization of subplot levels (varieties) was done within each main plot.

For economic analysis, STATA version 17.0 was used to determine predictive margins for revenue-to-cost ratios through a linear regression function. Factors considered in the model were treatment (rotation or control), crop variety, and season. Interactions between treatment and variety, treatment and season, season and variety, and season × variety × treatment were included in the analysis. Mean values were separated by use of Fisher’s least significant difference (LSD) at α = 0.05. LSD values are used in statistical analysis to determine whether the difference between two mean values is statistically significant. In the context of our tables, an LSD value provides a threshold: if the difference between the mean values of two treatments exceeds this threshold, the difference is considered statistically significant at the specified confidence level (usually 95%).

The economic benefits of crop rotation between rice and sweetpotato were determined using financial cost–benefit analysis based on data collected from the field and local market prices during the two crop rotations. The cost of production was estimated for each rotation and control block. Further, the study measured the revenue-to-cost ratio by variety, block, and season. The revenue-to-cost ratio was estimated by dividing the total revenue by the total production costs.

In addition to the experimental data, the economic analysis was carried out with the following field data; it was assumed that the potential vine yield per block (i.e., area size: 360 m2) was 18 bags. The weight per bag of vine cuttings was, on average, 35 kg and, hence, total production per block would be 630 kg of vine cuttings per block. A bag of sweetpotato roots weighing 120 kg was assumed to cost 55,000 UGX (USD 16; exchange rate 1 USD = 3437.5 Ugandan Shillings (UGX)) for the year 2016. For estimating revenue, we valued the production of both vine cuttings and roots based on current market prices. For example, a 35 kg bag of vine cuttings was valued at 15,000 UGX (USD 4.4) in 2016. The market price for roots increased in the second season of 2016 to 70,000 UGX (USD 20.4) per 120 kg bag of roots and increased further to 80,000 UGX (USD 23.3) in the first season of 2017 (third rotation). Similarly, the price of vine cuttings also increased to 20,000 UGX (USD 5.5) per bag. The price of planting material used in the calculations was slightly higher than the market price, as these materials were free from SPVD because they were sourced from Biocrops, a Ugandan private tissue-culture company that employs quality control measures. The revenue-to-cost ratio was estimated in two contexts: (1) assuming that the unit of the outcome of sweetpotato was estimated in kilograms for both roots and vines and (2) assuming that the outcome of vine production was a number of vine cuttings (30 cm cuttings) and roots in kilograms. Rice seed was estimated in kg using a market price of 5,000 UGX (USD 1.4) across three seasons. The market price for rice seed remained fairly constant during the experimental period. Data on the cost of labour for all field activities and inputs were recorded during the experiment on a real-time basis. This was combined with data on sweetpotato root and vine yield as well as rice yield per plot, which was used to compute the revenue-to-cost ratio. Paddy was harvested from the net plot and converted to tons ha−1, adjusted to a 14% moisture content.

3 Results

3.1 Soil chemical properties of the experimental site

The soils at the experimental site were loamy, with an average pH of 6.0 (range: 5.3–6.8). They were high in organic matter (4%) and available nitrogen (0.25%) but overall low in phosphorus (average: 3.2 mg/kg) and moderate in potassium (average: 55.1 mg/kg). Levels of calcium and magnesium were both high. The average levels of calcium and magnesium were 2234.6 and 567.0 ppm, respectively. A detailed analysis report, including the typical soil nutrient requirements of sweetpotato, is presented in Table A1.

3.2 Effect of rotation on rice yields

In the treatment plot, the paddy yield of rice grown after sweetpotato was significantly higher than that for the control (P = 0.001), where rice followed rice. There was also a significant difference (P < 0.001) in yield performance of the different rice varieties (Table 3).

Mean value of paddy yield of three rice varieties rotated with sweetpotato after three seasons

| Treatment | Variety | Paddy yield (t ha−1) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2016A | 2016B | 2017A | Overall mean per variety | Standard deviation | ||

| Control | Agoro | 2.60 | 3.73 | 4.80 | 3.71 | 1.10 |

| Komboka | 3.68 | 4.90 | 4.50 | 4.36 | 0.62 | |

| Wita-9 | 2.68 | 4.20 | 4.73 | 3.87 | 1.06 | |

| Rotation | Agoro | 2.83 | 4.00 | 5.20 | 4.01 | 1.19 |

| Komboka | 4.88 | 6.13 | 6.35 | 5.79 | 0.79 | |

| Wita-9 | 3.60 | 5.78 | 5.57 | 4.98 | 1.20 | |

| Mean | 3.38 | 4.79 | 5.19 | |||

| CV (%) | 15.33 | 15.89 | 19.40 | |||

| LSD0.05 rotation (R) | 0.45 | 0.66 | 0.88 | |||

| LSD0.05 variety (V) | 0.55 | 0.81 | n.s. | |||

| LSD0.05 rotation × variety | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | |||

n.s. - not significant.

The rotation produced yield gains in the three rice varieties tested when compared to the average yield during the baseline season of 2015 (average yield in control plots = 2.66 t ha−1, average yield in rotation plots = 2.63 t ha−1). The highest percent yield gain (35%) was attributable to the rotation compared to the control for the variety Wita 9, followed by Komboka (29%), whereas the Agoro variety had the lowest yield gain (8%).

3.3 Effect of rotation on sweetpotato vine and root yields

Rotating sweetpotato and rice across three seasons also had a significant effect on sweetpotato root yield (P = 0.03) but not on vine yield (Tables 3 and 4). The average root yield in the rotation treatment was significantly higher (mean yield = 28.0 t ha−1) than in the control (mean yield = 19.8 t ha−1) when compared to the baseline average yield in 2015 (mean control yield = 14.6 t ha−1, mean rotation yield = 20.2 t ha−1) (baseline yields in 2015 is presented in Table A2). The root yields of the three varieties were significantly different (P = 0.021), and the interaction between treatment and variety was also significant (P = 0.034). The variety Ejumula had the highest mean yield (29 t ha−1), followed by NASPOT 10 O and NASPOT 11. All varieties performed better in the rotation than the control (Table 4).

Overall mean root yield for three sweetpotato varieties planted during three seasons in rotation with rice in the Agoro rice scheme, northern Uganda

| Treatment | Variety | Yield (t ha−1) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2016A | 2016B | 2017A | Overall mean per variety | Standard deviation | ||

| Control | Ejumula | 23.7 | 6.6 | 31.2 | 20.5 | 5.2 |

| NASPOT 10 O | 25.2 | 4.2 | 37.1 | 22.2 | 10.6 | |

| NASPOT11 | 19.0 | 8.6 | 20.2 | 15.9 | 4.0 | |

| Rotation | Ejumula | 32.4 | 9.8 | 72.6 | 38.3 | 2.6 |

| NASPOT 10 O | 24.5 | 6.0 | 38.3 | 22.9 | 5.2 | |

| NASPOT11 | 31.0 | 7.8 | 36.5 | 25.1 | 4.3 | |

| Mean | 26.0 | 7.1 | 39.3 | |||

| CV (%) | 14.7 | |||||

| LSD0.05 rotation | 7.6 | |||||

| LSD0.05 variety | 6.1 | |||||

| LSD0.05 season | 6.7 | |||||

| LSD0.05 rotation × variety | 8.7 | |||||

| LSD0.05 rotation × season | 9.2 | |||||

| LSD0.05 season × variety | NS | |||||

| LSD0.05 rotation × variety × season | NS | |||||

NS – not significant.

Table 5 shows that vine yields were not significantly different across treatments and varieties but were significantly different across seasons (P = 0.001). The highest vine yield was observed in 2017A (27.4 t ha−1), whereas the lowest vine yield was in 2016B (14.6 4 t ha−1). The low vine and root yields in 2016B can be attributed to the prolonged dry season experienced in 2016B. In that season, the water supply in the scheme was not adequate for occasional irrigation. Even though total vine yields were not significantly different across treatments, the total number of 30 cm vine cuttings was significantly different between treatments and seasons (P < 0.001) when measured, and the interaction between season and variety was significant (P < 0.001) (Tables 4 and 5). It is important to note that data on the number of cuttings per plot were not taken in 2016A. Irrespective of season, the rotation treatment produced more vine cuttings than the control – mean of 1,017 and 3,510 cuttings per plot in 2016B and 2017A, respectively, compared to the 679 and 1,253 cuttings produced in the same years in the control plots. This could be the effect of residual fertilizers applied to rice in the preceding season of the rotation.

Overall mean vine yield and number of 30 cm vine cuttings for three sweetpotato varieties planted during three seasons in rotation with rice in Agoro rice scheme, northern Uganda

| Treatment | Variety | Vines yield (tons ha−1) | No. vine cuttings (30 cm) (per 30 m2) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2016A | 2016B | 2017A | Overall mean per variety | Standard deviation | 2016B | 2017A | ||

| Control | Ejumula | 17.4 | 10.0 | 33.1 | 20.2 | 9.7 | 867.0 | 1219.0 |

| NASPOT 10 O | 27.8 | 11.0 | 24.2 | 21.0 | 7.8 | 595.0 | 1304.0 | |

| NASPOT11 | 24.0 | 24.8 | 24.6 | 24.5 | 1.5 | 577.0 | 1238.0 | |

| Mean | 23.1 | 15.3 | 27.3 | 21.9 | 6.1 | 679.0 | 1253.0 | |

| Rotation | Ejumula | 20.0 | 11.2 | 22.6 | 17.9 | 5.9 | 1041.0 | 3653.0 |

| NASPOT 10 O | 19.8 | 11.2 | 28.7 | 19.9 | 8.8 | 794.0 | 3413.0 | |

| NASPOT11 | 27.6 | 19.7 | 31.2 | 26.2 | 5.9 | 1218.0 | 3466.0 | |

| Mean | 22.5 | 14.0 | 27.5 | 21.3 | 6.8 | 1017.0 | 3510.0 | |

| Overall mean | 22.8 | 14.6 | 27.4 | 849.0 | 2382.0 | |||

| CV (%) | 8.4 | 32.3 | ||||||

| LSD0.05 rotation | NS | 205.0 | ||||||

| LSD0.05 variety | NS | NS | ||||||

| LSD0.05 season | 6.4 | 355.1 | ||||||

| LSD0.05 rotation × variety | NS | NS | ||||||

| LSD0.05 rotation × season | NS | NA | ||||||

| LSD0.05 season × variety | NS | NA | ||||||

| LSD0.05 rotation × variety × season | NS | NA | ||||||

Average vine cuttings (tons ha−1): control = 21.9, treatment = 21.3.

NS – not significant, NA – not available.

3.4 Cost and benefit analysis of the rotation

The breakdown costs of producing sweetpotato and rice in rotation and control treatments are presented in Table 6.

Actual cost of producing sweetpotato roots (US$), vine cuttings, and paddy rice in rotation vs control plots in the Agoro rice scheme 2016 to 2017

| Cost category | Rotation | Control | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total cost (2016A) | Total cost (2016B) | Total cost (2017A) | Total cost (2016A) | Total cost (2016B) | Total cost (2017A) | |

| Input cost | 55.4 | 47.7 | 48.2 | 55.4 | 53.0 | 51.2 |

| Labour cost | 147.6 | 132.8 | 138.6 | 137.2 | 127.0 | 128.1 |

| Fixed cost | 28.7 | 30.4 | 31.6 | 28.7 | 32.1 | 31.6 |

| Wastage cost | 9.2 | 9.9 | 10.4 | 10.5 | 12.3 | 16.0 |

| Total cost | 240.9 | 220.8 | 228.9 | 231.8 | 224.5 | 227.0 |

| Total revenue | 482.2 | 446.4 | 553.5 | 395.6 | 326.3 | 450.5 |

| Net profit | 241.3 | 225.6 | 324.6 | 163.9 | 101.9 | 223.5 |

| Share of input costs to the total costs (%) | ||||||

| Input cost | 23 | 22 | 21 | 24 | 24 | 23 |

| Labour cost | 61 | 60 | 61 | 59 | 57 | 56 |

| Fixed cost | 12 | 14 | 14 | 12 | 14 | 14 |

| Wastage cost | 3.8 | 4.5 | 4.6 | 5 | 5 | 7 |

Exchange rate 1 USD = 3437.5 Ugandan Shillings (UGX) as of 2016.

The total cost of production was broken down into four categories: inputs used, labour, and fixed and wastage costs. The input costs consisted of costs of seed and sweetpotato planting materials, fertilizer, pesticides, and irrigation (i.e. paid user fee to the cooperative). The labour costs focused on wages paid to the labourers for various input applications such as land preparation, planting, weeding, irrigation, fertilizer applications, bird management, threshing, drying, winnowing, packing, and harvesting costs. The fixed costs included the cost of equipment such as irrigation materials (i.e. water tank, water can, and bucket), planting rakes that are used for making rows or lines, sickles, knapsack, protective gears, spade, hand trowel, spraying suite, special nose masks, seed trays, bird deterrent net, weighing scale, fencing, cutlers, slashers, rice weeders, and hand hoes. The fixed cost depreciated based on the life cycle of the product and usage. Costs were also estimated per block and per crop. Labour costs constituted the major share of the total costs in both rotation and control plots, but in the rotation plots, the share of input cost declined slightly as the number of rotations increased (Table 6). This trend was not observed for the control plots. Furthermore, Table 6 presents data on net profit according to crop rotation and season. The results show that rotation generates more net profit compared to monocropping, emphasizing the opportunity cost of foregoing a rice crop to grow sweetpotato in a rotational system. The descriptive statistics for the revenue-to-cost ratio by variety and rotation in all seasons are presented in Table 7.

Descriptive statistics for mean revenue-to-cost ratio by variety and rotation in all seasons

| Variety | Treatment | Mean | Std deviation | N |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All varieties | Rotation | 2.15 | 0.33 | 18 |

| Control | 1.72 | 0.44 | 18 | |

| NASPOT 10 O | Rotation | 2.00 | 0.07 | 3 |

| Control | 1.56 | 0.20 | 3 | |

| NASPOT 11 | Rotation | 1.96 | 0.45 | 3 |

| Control | 1.62 | 0.12 | 3 | |

| EJUMULA | Rotation | 2.12 | 0.21 | 3 |

| Control | 1.64 | 0.17 | 3 | |

| WITA 9 | Rotation | 2.29 | 0.48 | 3 |

| Control | 1.76 | 0.53 | 3 | |

| KOMBOKA | Rotation | 2.68 | 0.35 | 3 |

| Control | 2.01 | 0.26 | 3 | |

| AGORO | Rotation | 1.85 | 0.59 | 3 |

| Control | 1.69 | 0.57 | 3 |

Though the total cost of production was almost the same for both rotation and control plots, the revenue generated from the production was higher for the rotation compared with the control, resulting in the higher revenue-to-cost ratio in rotation between rice and sweetpotato compared with the control. ANOVA results showed that there was a statistically significant difference in the net income between rotation and control (Table 8).

ANOVA summary for revenue to cost ratio for all seasons by interventions (rotation vs control)

| Source of variation | df | MS | F | P | Effect size (partial SS) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall significance test across rotation, variety, and seasons for both sweetpotato and rice | |||||

| Overall model | 8 | 0.59 | 7.45 | 0.0000* | 4.70 |

| Rotation | 1 | 1.68 | 21.34 | 0.0001* | 1.68 |

| Variety | 5 | 0.30 | 3.81 | 0.0097* | 1.50 |

| Seasons | 2 | 0.76 | 9.62 | 0.0007* | 1.52 |

| Residual | 27 | 0.08 | |||

| Total | 35 | 0.20 | 6.83 | ||

| Interaction effect between rotation and seasons for both sweetpotato and rice: All varieties | |||||

| Overall model | 5 | 0.67 | 5.63 | 0.000* | 3.31 |

| Rotation | 1 | 1.68 | 14.33 | 0.000* | 1.68 |

| Seasons | 2 | 0.76 | 6.46 | 0.004* | 1.52 |

| Rotation*seasons | 2 | 0.05 | 0.46 | 0.635 | 0.11 |

| Residual | 30 | 0.12 | 3.52 | ||

| Total | 35 | 0.20 | 6.83 | ||

MS = mean squares, effect size = η 2 or partial η 2.

p (significance level): *1% level; **5% level; ***10% level; and ****15% level.

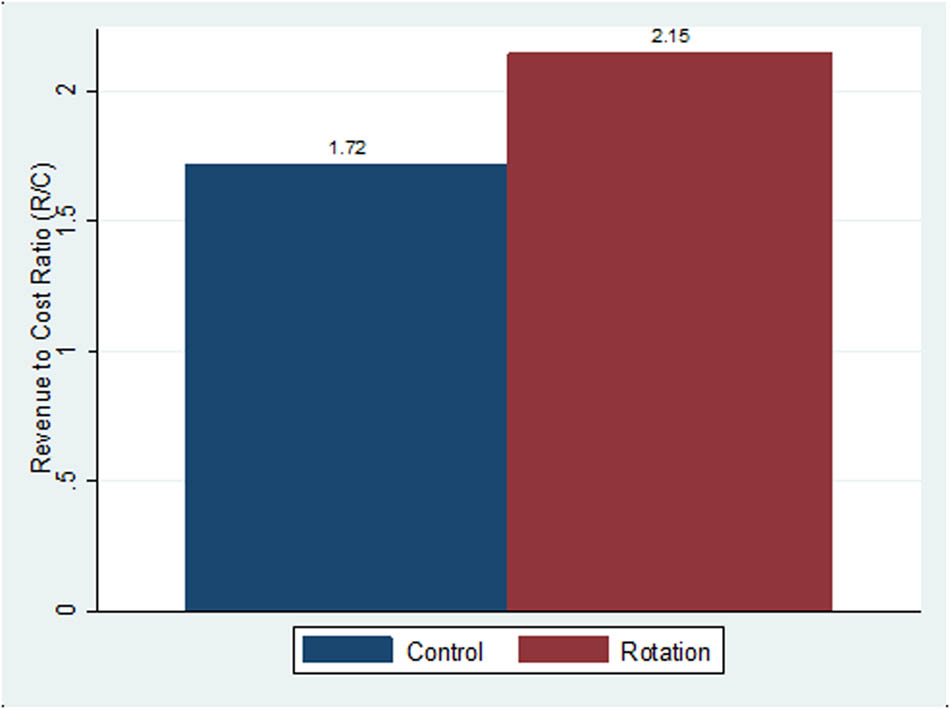

The revenue-to-cost ratio for both rotation and control was greater than 1 for rotation (2.15) and the control (1.72) (Figure 4), demonstrating that both approaches generated revenues exceeding the costs of production.

Revenue-to-cost ratio for rotation and control of sweetpotato and rice in Agoro rice scheme, northern Uganda.

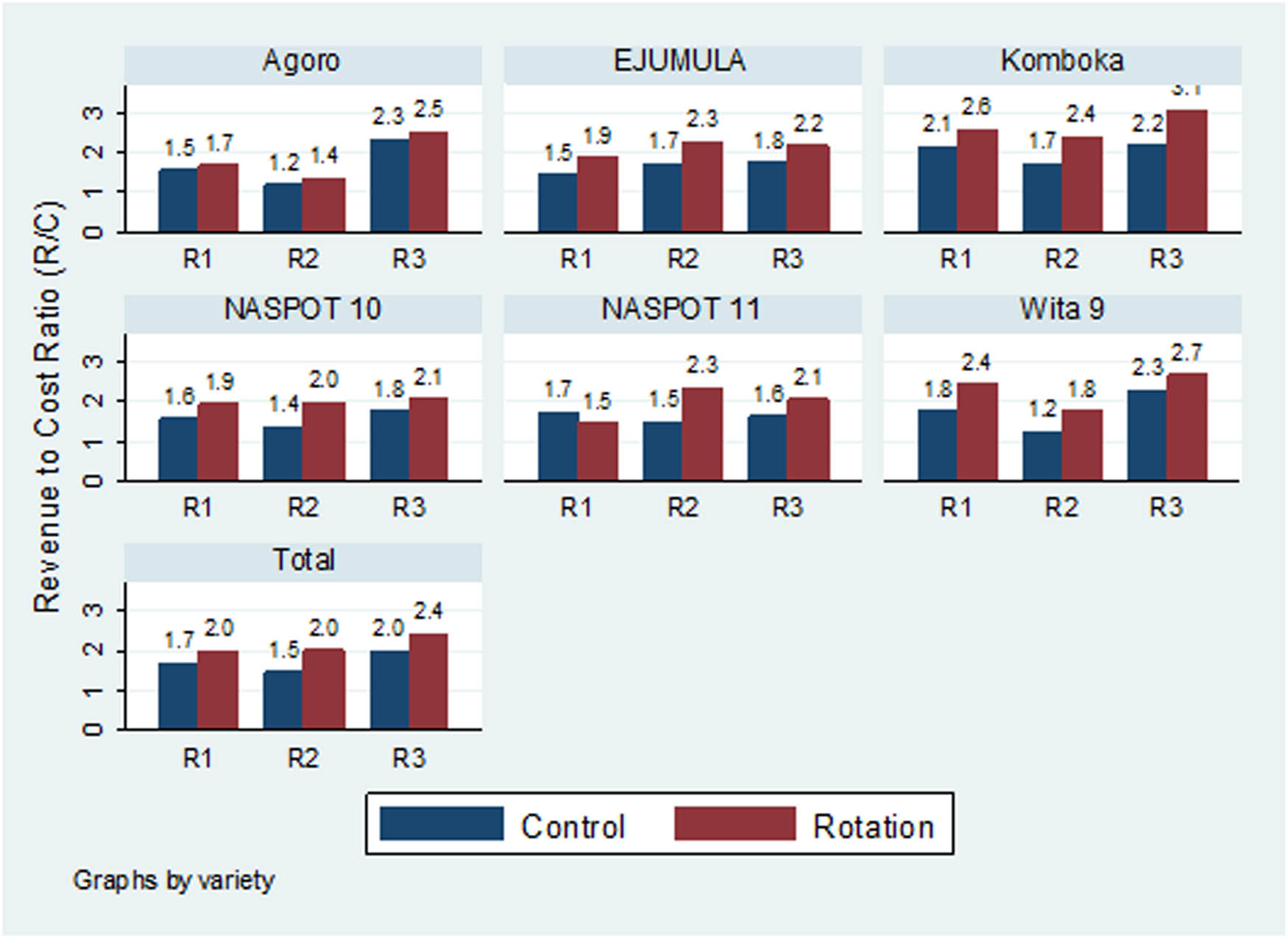

However, the rotation generated a revenue-to-cost ratio that was 0.43 times higher than the control (monocropping), indicating that both rotation and monocropping systems generated profits, but the rotation was more profitable than monocropping, where rotation generated 43% more profit compared to monocropping. Alternatively, the ratio indicates that if monocropping generates 1 dollar, the rotation can generate 1.43 dollars. The revenue-to-cost ratio for the two crops varied by season and variety, as shown in Figure 5.

Revenue-to-cost ratio of three sweetpotato varieties (Ejumula, NASPOT 10 O, and NASPOT 11) and three rice varieties (Agoro, Komboka, and Wita) and the overall revenue-to-cost ratio of both crops over three seasons in rotation (treatment) and monocropping (control) in the Agoro Rice scheme. Note: R1: 2016A, R2: 2016B, and R3: 2017.

In addition, ANOVA results, including predictive margins (Table A3), showed that the ratio varied in significance by season and variety. In summary, ANOVA and predictive margin results showed that the overall impact of crop rotation on the ratio was significant and positive for both sweetpotato and rice compared with monocropping alternatives, indicating that a rotation of both crops improved the revenue-to-cost ratio.

4 Discussion

Considering the baseline yield in season B 2015, the study showed that rice fields in northern Uganda could be used for producing sweetpotato planting materials during the December to March period when plots would otherwise be under fallow. The yield of rice can be enhanced by rotating rice and sweetpotato vis-à-vis continuous rice monocropping under Northern Uganda conditions. These results are consistent with Hung et al. [22], who found the paddy yield of rice following rice to be 3.4 t ha−1 compared to 4.6 t ha−1 when rice followed sweetpotato, representing a yield gain of 35% due to the benefits of rotation. They attributed the yield gain to the higher nitrogen (N) fertilizer-use efficiency of rice (29%), following sweetpotato, compared with lower N-fertilizer-use efficiency of 19% for rice following another rice crop. Similarly, Ning et al. [23] found that in a rotation of sweetpotato with wheat where potassium fertilizer was applied, the root yield and total rotation yield increased by 20.7‒24.5%. The yield increase in this experiment was attributed to the application of fertilizers and the return of residues back to the gardens. The results from this study showed yield increases for sweetpotato ranging from 3 to 132% across the three seasons, which is higher than that reported by Hung et al. [22] and Ning et al. [23].

NASPOT 11 performed poorly each season in the control treatment, with its mean yield (15.9 t ha−1) being lower than that reported by Mwanga et al. [19] (26 t ha−1) at variety release. This, however, is consistent with its performance in national on-farm trials. In those trials, NASPOT 11 had much lower yields in the Northern region site than in the Central, Eastern, and Western Ugandan sites [19,24].

According to Thierfelder and Wall [25], rotations may improve soil quality, and deep-rooting crops can lead to better soil structure, aggregation, and pore continuity, with positive effects on infiltration and soil moisture in rainfed agricultural settings. Therefore, the higher yield of rice in this rotation may be attributed to the rooting properties of sweetpotato, potentially improving soil structure and, consequently, water infiltration and soil moisture. However, our results also showed that rice genotypes responded differently to the rotation with sweetpotato. Hence, rice varieties with different growth patterns and maturity periods must be tested when establishing new rice–sweetpotato rotations.

Throughout the study, rice plots received fertilizer in the form of NPK, and the subsequent sweetpotato crop could have benefited from residual fertilizers applied to rice the previous season, thereby contributing to the improved root yields observed. Young et al. [26] indicated that given the current low market value of sweetpotato, investment in soil fertility improvements might only be financially viable in an integrated soil and crop management system, which includes rotational cropping, whereby fertilizers used for other higher-value crops can provide residual benefits to the sweetpotato and rotational cropping with legumes to provide additional nitrogen. Residual fertilizers could have contributed to increases in sweetpotato yields in this study.

Nedunchezhiyan et al. [12] observed that soil bulk density significantly decreased from 1.41 to 1.37 g cm−3 when sweetpotato was planted after rice in India. Low soil bulk density can enhance rooting depth and available soil water, which influence productivity [27]. This is possibly another reason for the increase in sweetpotato root yield.

Lukonge et al. [28] reported a good response to the direct application of inorganic and organic fertilizers in Tanzania for vine production. In their study, application of 50 kg of nitrogen per hectare resulted in 196 cuttings (each 30 cm in length) per 1.2-m2 plot, with an incremental yield of 765,490 cuttings per hectare compared with 123 cuttings per plot recorded in the control plot. Namanda and Gibson [13] found that farmers could double the number of cuttings produced through the judicious use of NPK (25:5:5) fertilizer. Although no direct fertilizers were applied to sweetpotato in our study, we suggest that the higher number of vine cuttings recorded in the rotation treatment was a likely response to the residual fertilizer applied to rice during the preceding season. This practice also addresses the deficit in available planting material at the beginning of the rainy season created by the long drought period that farmers in rainfed systems face. In addition, roots harvested early in the season can address food shortages during the well-documented “hunger season” [29].

In the case of NASPOT 11, the overall impact of rotation was not significant, but significance was observed to increase with season. This implies that we might have to rotate more times with NASPOT 11 to realize financial benefits. In the case of NASPOT 10 O, the overall results showed the impact of rotation was significant in improving economic benefits. The results indicated that the Komboka rice variety was superior to the other two and best in rotation with sweetpotato, NASPOT 10 O, or Ejumula.

The study on rice–sweetpotato crop rotation was conducted in the irrigation scheme, Agoro rice scheme, where the crop was irrigated during the dry season, which was a drawback due to a lack of data under rainfed conditions. There is a need to conduct a study in a pure rainfed condition to be able to validate the assertion that sweetpotato can grow with minimal moisture during the dry season. Furthermore, whereas soil data for the initial period during the start of the study was collected and presented, soil data for successive seasons were not collected. As such, important soil parameters like NUE, as reported by Nedunchezhiyan et al. [30], Yu et al. [22], and Hung et al. [14], could not be calculated. Future related studies should be set up in both rainfed and irrigated systems, collect and present data on soil properties like accumulation of nitrogen, organic matter, and NUE. This will help explain parameters like rice and sweetpotato yield, number of tillers, panicles, leaf area index, and harvest indices better. These will improve future recommendations on the rice–sweetpotato rotation systems.

5 Conclusion

This study showed the agronomic and economic benefits of rotating sweetpotato with irrigated rice in the lowland rice-production systems. Farmers in the rice schemes can easily rotate sweetpotato with rice. Overall, sweetpotato roots and rice in the rotation yielded better than in the monocropping systems. The higher number of vines recorded in the rotation compared to control signifies a potential income advantage for farmers selling planting materials. This also enables the availability of quality planting materials after the long dry season. In addition, this new practice would allow farmers in upland areas to access vines when they need them at the time of planting, a remedy for late planting on account of scarcity of planting materials. The revenue-to-cost ratio was higher in rotation than control, indicating that rotating sweetpotato with rice was more profitable than monocropping in northern Uganda when there is a unimodal rainfall season. However, a deeper study is required to understand whether sweetpotato would yield well in the rotation under rainfed conditions. There is a need to replicate the current study in other regions growing rice in Uganda under the monocropping system. Rice–sweetpotato rotation should be demonstrated in other rice-growing regions of Uganda for farmers to appreciate and adopt this innovation. While sweetpotato–rice rotation has been shown to increase yields for rice and sweetpotato, the increase in yield for sweetpotato has been heavily linked to residual fertilizers from the previous rice crop. However, there are challenges to increasing fertilizer use in Uganda, particularly the high cost of fertilizers. Strategies to overcome these challenges may require different policies to incentivize fertilizer adoption as well as strategies to educate farmers on the benefits of crop rotations.

Acknowledgements

We thank the leaders of Tutte Laco Laco (TULA) Youth group and the farmers in the study area for their support in mobilizing the resources. The authors wish to express their appreciation to Elke Vandamme for her review. We are grateful to the referees for their constructive inputs.

-

Funding information: This research was coordinated by the International Potato Center and National Agricultural Research Organisation (NARO) Uganda as part of the CGIAR Research Program on Roots, Tubers, and Bananas (RTB), Sweetpotato Action for Security and Health in Africa, and CGIAR Seed Equal Initiative. It is supported by CGIAR Trust Fund contributors (http://www.cgiar.org/funders/).

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and consented to its submission to the journal, reviewed all the results and approved the final version of the manuscript. GK: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing, validation, visualization, and supervision. SR: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, funding acquisition, investigation, methodology, project administration, resources, validation, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing, and visualization. SA: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, methodology, validation, visualization, writing – original draft, and writing – review and editing. SZ: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, methodology, validation, visualization, writing – original draft, and writing – review and editing. MM: conceptualization, funding acquisition, investigation, project administration, resources, supervision, validation, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing, and visualization. ME: conceptualization, methodology, validation, visualization, and writing – review and editing. SO: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, validation, visualization, and writing – review and editing. SN: conceptualization, data curation, investigation, methodology, validation, visualization, and writing – review and editing. MHO: conceptualization, data curation, investigation, methodology, validation, visualization, and writing – review and editing. JL: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing, validation, visualization, and supervision. ROM: conceptualization, methodology, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing, validation, and visualization. JL: conceptualization, funding acquisition, investigation, methodology, project administration, resources, supervision, validation, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing, and visualization.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the International Potato Center (CIP) but restrictions may apply to the availability of these data, which were used under licence for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of CIP.

Results of soil test

| Lab no. | Client’s reference | pH | OM | N | P | Ca | Mg | K |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | mg/kg | |||||||

| S/15/7747 | KA | 6.6 | 4.61 | 0.24 | Trace | 2870.0 | 930.3 | 77.6 |

| S/15/7748 | KB | 6.8 | 4.37 | 0.23 | 3.43 | 4391.4 | 1012.9 | 245.5 |

| S/15/7749 | KC | 5.8 | 4.65 | 0.24 | Trace | 1640.7 | 545.7 | 55.1 |

| S/15/7750 | NA | 5.8 | 4.52 | 0.24 | 4.96 | 1896.6 | 330.0 | 47.7 |

| S/15/7751 | NB | 5.6 | 5.83 | 0.29 | 0.54 | 1560.6 | 304.1 | 46.3 |

| S/15/7752 | SA | 6.2 | 5.19 | 0.26 | 3.26 | 2030.1 | 512.6 | 65.5 |

| S/15/7753 | SB | 5.3 | 4.61 | 0.24 | 3.77 | 1252.9 | 333.7 | 42.0 |

| Classification of mehlich-3 extractable nutrients | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category | P | K | Ca | Mg | OM | N |

| mg/kg | % | |||||

| Very low | 0–12 | 0–20 | <330 | <17 | 0.7–1.0 | <0.05 |

| Low | 12.5–22.5 | 20.5–40.5 | 330–655 | 17–46 | 1.0–1.7 | 0.05–0.15 |

| Medium | 23–35.5 | 41–72.5 | 655–1,640 | 46–87 | 1.7–3.0 | 0.15–0.25 |

| High | 36–68.5 | 73–138.5 | 1,640–3,280 | 87–145 | 3.0–5.15 | 0.25–0.5 |

| Very high | >69 | >139 | >3,280 | >145 | >5.15 | >0.5 |

Source: National Agricultural Research Organisation (NARO) – National Agriculture Research Laboratory, Kawanda, Uganda.

Note: critical values for pH: 5.2; sufficient levels: 5.27.0.

Mean root and vine yield (t ha−1) for sweetpotato varieties during the 2015 (baseline season) growing season in Agoro rice scheme, Northern Uganda

| Treatment | Variety | Root yield (t ha−1) | Vine yield (t ha−1) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Std Dev | Mean | Std Dev | ||||

| Control | Ejumula | 22.3 | 15.6 | ||||

| NASPOT 10 O | 20.5 | 14.6 | 9.19 | 24.1 | 20.17 | 7.04 | |

| NASPOT11 | 16.1 | 20.8 | |||||

| Rotation | Ejumula | 27.4 | 16.8 | ||||

| NASPOT 10 O | 20.2 | 20.2 | 6.04 | 17.5 | 18.9 | 8.62 | |

| NASPOT11 | 26.1 | 22.4 | |||||

| Mean paddy yield (t ha−1) in 2015B season | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | Variety | Yield (t ha−1 ) | Mean |

| Control | Agoro | 2.3 | 2.66 |

| Komboka | 3.3 | ||

| Wita-9 | 2.4 | ||

| Rotation | Agoro | 2.3 | 2.63 |

| Komboka | 3.1 | ||

| Wita-9 | 2.5 | ||

| Mean | 2.7 | ||

| CV (%) | 15 | ||

| LSD0.05 variety (V) | 0.05 | ||

| LSD0.05 rotation × variety | n.s | ||

ANOVA for revenue to cost ratio for all seasons by crop and varieties (rotation vs control)

| Source of variation | df | MS | F | p | Effect size (partial SS) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Significance test across rotation, variety, and seasons for sweetpotato | |||||

| Overall model | 13 | 0.10 | 2.53 | 0.19 | 1.33 |

| Rotation | 1 | 0.77 | 19.13 | 0.01* | 0.77 |

| Variety | 2 | 0.02 | 0.44 | 0.67 | 0.04 |

| Seasons | 2 | 0.10 | 2.57 | 0.19 | 0.21 |

| Rotation*Variety | 2 | 0.01 | 0.19 | 0.84 | 0.02 |

| Rotation*Seasons | 2 | 0.10 | 2.37 | 0.21 | 0.19 |

| Variety*Seasons | 4 | 0.03 | 0.67 | 0.64 | 0.11 |

| Residual | 4 | 0.04 | 0.16 | ||

| Total | 17 | 0.09 | 1.49 | ||

| Significance test across rotation, variety, and seasons for rice | |||||

| Overall model | 13 | 0.37 | 23.98 | 0.00* | 4.80 |

| Rotation | 1 | 0.91 | 59.24 | 0.00* | 0.91 |

| Variety | 2 | 0.50 | 32.18 | 0.00* | 0.10 |

| Seasons | 2 | 1.22 | 79.16 | 0.00* | 2.44 |

| Rotation*Variety | 2 | 0.10 | 6.65 | 0.05** | 0.20 |

| Rotation*Seasons | 2 | 0.002 | 0.11 | 0.90 | 0.003 |

| Variety*Seasons | 4 | 0.63 | 4.08 | 0.10*** | 0.25 |

| Residual | 4 | 0.02 | 0.06 | ||

| Total | 17 | 0.29 | 4.86 | ||

| Significance test between rotation and control for sweetpotato variety NASPOT 10 O | |||||

| Overall model | 3 | 0.11 | 8.95 | 0.10*** | 0.34 |

| Rotation | 1 | 0.28 | 22.01 | 0.04** | 0.28 |

| Season | 2 | 0.03 | 2.42 | 0.29 | 0.06 |

| Residual | 2 | 0.01 | 0.03 | ||

| Total | 5 | 0.07 | 0.36 | ||

| Significance test between rotation and control for sweetpotato variety NASPOT 11 | |||||

| Overall model | 3 | 0.10 | 0.60 | 0.67 | 0.29 |

| Rotation | 1 | 0.17 | 1.06 | 0.41 | 0.17 |

| Season | 2 | 0.06 | 0.37 | 0.73 | 0.12 |

| Residual | 2 | 0.16 | 0.32 | ||

| Total | 5 | 0.12 | 0.61 | ||

| Significance test between rotation and control for sweetpotato variety Ejumula | |||||

| Overall model | 3 | 0.16 | 39.62 | 0.02** | 0.48 |

| Rotation | 1 | 0.34 | 84.85 | 0.01** | 0.34 |

| Season | 2 | 0.07 | 17.01 | 0.06*** | 0.14 |

| Residual | 2 | 0.004 | 0.008 | ||

| Total | 5 | 0.10 | 0.49 | ||

| Significance test between rotation and control for rice variety WITA 9 | |||||

| Overall model | 3 | 0.47 | 47.49 | 0.02** | 1.41 |

| Rotation | 1 | 0.41 | 41.64 | 0.02** | 0.41 |

| Season | 2 | 0.50 | 50.41 | 0.02** | 0.10 |

| Residual | 2 | 0.01 | 0.02 | ||

| Total | 5 | 0.29 | 1.43 | ||

| Significance test between rotation and control for rice variety Komboka | |||||

| Overall model | 3 | 0.33 | 15.04 | 0.06*** | 1.00 |

| Rotation | 1 | 0.67 | 30.14 | 0.03** | 0.67 |

| Season | 2 | 0.17 | 7.48 | 0.12**** | 0.33 |

| Residual | 2 | 0.2 | 0.44 | ||

| Total | 5 | 0.21 | 0.04 | ||

| Significance test between rotation and control for rice variety Agoro | |||||

| Overall model | 3 | 0.47 | 1036.07 | 0.00* | 1.40 |

| Rotation | 1 | 0.04 | 85.33 | 0.01* | 0.04 |

| Season | 2 | 0.68 | 1511.44 | 0.00* | 1.36 |

| Residual | 2 | 0.001 | 0.001 | ||

| Total | 5 | 0.28 | 1.40 | ||

| Predictive margins for revenue-to-cost ratio for all seasons by interventions (rotation vs control) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Margin | Std. Err. | t | P > |t| |

| Margins for overall significance test across rotation, variety, and seasons for both sweetpotato and rice | ||||

| Rotation vs control (overall) | ||||

| Control | 1.72 | 0.080 | 21.24 | 0.000* |

| Rotation | 2.15 | 0.080 | 26.59 | 0.000* |

| Rotation vs control (sweetpotato) | ||||

| Control | 1.61 | 0.067 | 24.01 | 0.000* |

| Rotation | 2.02 | 0.067 | 30.20 | 0.000* |

| Rotation vs control (rice) | ||||

| Control | 1.82 | 0.041 | 44.05 | 0.000* |

| Rotation | 2.27 | 0.041 | 54.93 | 0.000* |

| Varieties for sweetpotato | ||||

| NASPOT 10 | 1.78 | 0.114 | 15.52 | 0.000* |

| NASPOT 11 | 1.79 | 0.114 | 15.64 | 0.000* |

| Ejumula | 1.88 | 0.114 | 16.39 | 0.000* |

| Varieties for rice | ||||

| Wita 9 | 2.03 | 0.114 | 17.67 | 0.000* |

| Komboka | 2.34 | 0.114 | 20.45 | 0.000* |

| AGORO | 1.77 | 0.114 | 15.45 | 0.000* |

| Rotation*Variety (sweetpotato) | ||||

| Control*NASPOT 10 O | 1.56 | 0.116 | 13.47 | 0.000* |

| Control*NASPOT 11 | 1.62 | 0.116 | 13.99 | 0.000* |

| Control*Ejumula | 1.64 | 0.116 | 14.13 | 0.000* |

| Rotation*NASPOT 10 O | 1.99 | 0.116 | 17.18 | 0.000* |

| Rotation*NASPOT 11 | 1.96 | 0.116 | 16.89 | 0.000* |

| Rotation*EJUMULA | 2.12 | 0.116 | 18.24 | 0.000* |

| Rotation*Variety (rice) | ||||

| Control*Wita9 | 1.56 | 0.116 | 13.47 | 0.000* |

| Control*Komboka | 1.62 | 0.116 | 13.99 | 0.000* |

| Control*Agoro | 1.64 | 0.116 | 14.13 | 0.000* |

| Rotation*Wita 9 | 1.99 | 0.116 | 17.18 | 0.000* |

| Rotation*Komboka | 1.96 | 0.116 | 16.89 | 0.000* |

| Rotation*Agoro | 2.12 | 0.116 | 18.24 | 0.000* |

| Seasons (both sweetpotato and rice) | ||||

| 2016A season | 1.85 | 0.099 | 18.66 | 0.000* |

| 2016B season | 1.73 | 0.099 | 17.54 | 0.000* |

| 2017A season | 2.21 | 0.099 | 22.39 | 0.000* |

| Seasons (sweetpotato) | ||||

| 2016A season | 1.67 | 0.082 | 39.99 | 0.000* |

| 2016B season | 1.86 | 0.082 | 46.28 | 0.000* |

| 2017A season | 1.92 | 0.082 | 34.96 | 0.000* |

| Seasons (rice) | ||||

| 2016A season | 2.02 | 0.051 | 20.33 | 0.000* |

| 2016B season | 1.61 | 0.051 | 22.67 | 0.000* |

| 2017A season | 2.50 | 0.051 | 23.40 | 0.000* |

| Variety*Seasons (sweetpotato) | ||||

| NASPOT 10 O*2016A season | 1.75 | 0.142 | 12.28 | 0.000* |

| NASPOT 10 O*2016b season | 1.68 | 0.142 | 11.78 | 0.000* |

| NASPOT 10 O*2017A season | 1.92 | 0.142 | 13.47 | 0.000* |

| NASPOT 11*2016A season | 1.60 | 0.142 | 11.22 | 0.000* |

| NASPOT 11*2016B season | 1.92 | 0.142 | 13.47 | 0.000* |

| NASPOT 11*2017A season | 1.87 | 0.142 | 13.12 | 0.000* |

| Ejumula*2016A season | 1.67 | 0.142 | 11.71 | 0.000* |

| Ejumula*2016B season | 1.99 | 0.142 | 14.00 | 0.000* |

| Ejumula*2017A season | 1.98 | 0.142 | 13.93 | 0.000* |

| Variety*seasons (rice) | ||||

| Wita 9*2016A season | 2.10 | 0.088 | 23.89 | 0.000* |

| Wita 9*2016B season | 1.50 | 0.088 | 17.05 | 0.000* |

| Wita 9*2017A season | 2.49 | 0.088 | 28.33 | 0.000* |

| Komboka*2016A season | 2.36 | 0.088 | 26.85 | 0.000* |

| Komboka*2016B season | 2.05 | 0.088 | 23.37 | 0.000* |

| Komboka*2017A season | 2.63 | 0.088 | 29.93 | 0.000* |

| Agoro*2016A season | 1.62 | 0.088 | 18.41 | 0.000* |

| Agoro*2016B season | 1.28 | 0.088 | 14.59 | 0.000* |

| Agoro*2017A season | 2.42 | 0.088 | 27.54 | 0.000* |

| Rotation*seasons (both sweetpotato and rice) | ||||

| Control*2016A season | 1.70 | 0.139 | 12.13 | 0.000* |

| Control*2016B season | 1.45 | 0.139 | 10.38 | 0.000* |

| Control*2017A season | 2.00 | 0.139 | 14.28 | 0.000* |

| Rotation*2016A season | 2.00 | 0.139 | 14.25 | 0.000* |

| Rotation*2016B season | 2.02 | 0.139 | 14.42 | 0.000* |

| Rotation*2017A season | 2.43 | 0.139 | 17.39 | 0.000* |

| Rotation*seasons (sweetpotato) | ||||

| Control*2016A season | 1.58 | 0.116 | 13.61 | 0.000* |

| Control*2016B season | 1.52 | 0.116 | 13.10 | 0.000* |

| Control*2017A season | 1.73 | 0.116 | 14.88 | 0.000* |

| Rotation*2016A season | 1.76 | 0.116 | 15.14 | 0.000* |

| Rotation*2016B season | 2.20 | 0.116 | 18.96 | 0.000* |

| Rotation*2017A season | 2.11 | 0.116 | 18.21 | 0.000* |

| Rotation*seasons (rice) | ||||

| Control*2016A season | 1.81 | 0.072 | 25.32 | 0.000* |

| Control*2016B season | 1.38 | 0.072 | 19.32 | 0.000* |

| Control*2017A season | 2.27 | 0.072 | 31.65 | 0.000* |

| Rotation*2016A season | 2.23 | 0.072 | 31.14 | 0.000* |

| Rotation*2016B season | 1.83 | 0.072 | 25.60 | 0.000* |

| Rotation*2017A season | 2.75 | 0.072 | 38.40 | 0.000* |

Note: MS = mean squares, effect size = η 2 or partial η 2 .

p (significance level) *1% level; **5% level; ***10% level; and ****15% level.

Note: p (significance level) *1% level; **5% level; ***10% level; and ****15% level.

Remarks: The soils are mainly low in phosphorus and moderate in potassium in a few of the highlighted blocks. This indicates that the use of phosphates and potash fertilizers is a must for successful plant growth.

Crop requirements (sweetpotato): Sweetpotatoes grow in a wide variety of soils, from swamps to eroded areas, but they perform best on well-drained sandy loam soils and poorly on clay soils. They are sensitive to alkaline and saline soils, and their preferred soil pH is 5.5–6.5. They show a good response to farmyard manure, which increases the yield and quality of the storage roots. Mineral fertilizers, especially potassium (K), which promotes swelling of the storage roots, are also important. A common recommendation in most countries that grow sweetpotatoes is 35–65 kg/ha N, 50–100 kg/ha P2O5, and 85–170 kg/ha K. This combination of fertilizers is usually applied as NPK compound fertilizer with a high K content.

References

[1] Low JW, Mwanga R, Andrade M, Carey E, Ball AM. Tackling vitamin A deficiency with biofortified sweetpotato in sub-Saharan Africa. Global Food Secur. 2017;14:23–30.10.1016/j.gfs.2017.01.004Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[2] Rachkara P, Phillips DP, Kalule SW, Gibson RW. Innovative and beneficial informal sweetpotato seed private enterprise in northern Uganda. Food Secur. 2017;9(3):595–610.10.1007/s12571-017-0680-4Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[3] Ssemakula G, Niringiye C, Otema M, Kyalo G, Namakula J, Mwanga R, et al. Evaluation and delivery of disease-resistant and micronutrientdense sweetpotato varieties to farmers in Uganda. Uganda J Agric Sci. 2014;15(2):101–11.Suche in Google Scholar

[4] UBOS (Uganda Bureau of Statistics). Statistical Abstract. Kampala, Uganda: Government of Uganda; 2023.Suche in Google Scholar

[5] Namirimu J, Okello JJ, Kizito AM, Ssekiboobo AM. Gender‐differentiated preference for sweetpotato traits and their drivers among smallholder farmers: Implications for breeding. Crop Sci. 2024;64:1251–65. 10.1002/csc2.21190.Suche in Google Scholar

[6] Bayiyana I, Okello JJ, Mayanja SL, Nakitto M, Namazzi S, Osaru F, et al. Barriers and enablers of crop varietal replacement and adoption among smallholder farmers as influenced by gender: the case of sweetpotato in Katakwi district, Uganda. Front Sustainable Food Syst. 2024;8. 10.3389/fsufs.2024.1333056.Suche in Google Scholar

[7] Mwanga ROM, Swanckaert J, Da Silva Pereira G, Andrade MI, Makunde G, Grüneberg WJ, et al. Breeding progress for vitamin A, iron and zinc biofortification, drought tolerance, and sweetpotato virus disease resistance in sweetpotato. Front Sustainable Food Syst. 2021;5. 10.3389/fsufs.2021.616674.Suche in Google Scholar

[8] Echodu R, Edema H, Wokorach G, Zawedde C, Otim G, Luambano N, et al. Farmers’ practices and their knowledge of biotic constraints to sweetpotato production in East Africa. Physiol Mol Plant Pathol. 2019;105:3–16. 10.1016/j.pmpp.2018.07.004.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[9] Namanda S. Current and potential systems for maintaining sweetpotato planting material in areas with prolonged dry seasons: a biological, social and economic framework. PhD thesis. London, UK: Natural Resources Institute, University of Greenwich; 2012.Suche in Google Scholar

[10] MAAIF. Uganda national rice development strategy (2nd draft). Ministry of Agriculture, Animal Industry and Fisheries. Entebbe, Uganda; 2023. http://www.jica.go.jp/english/our_work/thematic_issues/agricultural/pdf/uganda_en.pdf.Suche in Google Scholar

[11] UBOS (Uganda Bureau of Statistics). Statistical Abstract. Kampala, Uganda: Government of Uganda; 2010.Suche in Google Scholar

[12] Nedunchezhiyan M, Misra R, Naskar S. Zero tillage stand establishment of sweet potato: an option for intensive rice based cropping system. Proceedings of the National Seminar on Climate Change and Food Security: Challenges and Opportunities for Tuber Crops. Thiruvananthapuram: Central Tuber Crops Research Institute; 2011. p. 256–60.Suche in Google Scholar

[13] Namanda S, Gibson R. Shortage of sweetpotato planting material caused by prolonged dry seasons in Africa: strategies to increase its availability in Uganda. In: Low J, Nyongesa M, Quinn S, Parker M, et al. editors, Potato and sweetpotato in Africa: Transforming the value chains for food and nutrition security. Oxfordshire, United Kingdom: CABI; 2015. p. 322–9.10.1079/9781780644202.0322Suche in Google Scholar

[14] Hung NN, Nguyen BV, Buresh RJ, Bayley M, Watanabe T. Sustainability of paddy soil fertility in Vietnam. In: Toriyama K, Heong KL, Hardy B editors. Rice is life: scientific perspectives for the 21 st century. Proceedings of the World Rice Research Conference held in Tokyo and Tsukuba, Japan, November 2004; 2005. p. 590. Los Baños (Philippines): International Rice Research Institute, and Tsukuba (Japan): Japan International Research Center for Agricultural Sciences. 2005;CD-ROM.Suche in Google Scholar

[15] Wanyama J, Ssegane H, Kisekka I, Komakech AJ, Banadda N, Zziwa A, et al. Irrigation development in Uganda: constraints, lessons learned, and future perspectives. J Irrig Drain Eng. 2017;143(5):04017003.10.1061/(ASCE)IR.1943-4774.0001159Suche in Google Scholar

[16] Okalebo JR, Gathua KW, Woomer PL. Laboratory methods of soil and plant analysis: a working manual. Nairobi: Tropical Soil Biology and Fertility Programme; 1993.Suche in Google Scholar

[17] Mwanga ROM, Odongo B, Niringiye C, Alajo A, Abidin PE, Kapinga R, et al. Release of two orange-fleshed sweetpotato cultivars,‘spk004’(‘kakamega’) and ‘ejumula’, in Uganda. HortScience. 2007;42(7):1728–30.10.21273/HORTSCI.42.7.1728Suche in Google Scholar

[18] Mwanga ROM, Odongo B, Niringiye C, Alajo A, Kigozi B, Makumbi R, et al. ‘NASPOT 7’,‘NASPOT 8’,‘NASPOT 9 O’,‘NASPOT 10 O’, and ‘Dimbuka-Bukulula’ sweetpotato. HortScience. 2009;44(3):828–32.10.21273/HORTSCI.44.3.828Suche in Google Scholar

[19] Mwanga ROM, Niringiye C, Alajo A, Kigozi B, Namukula J, Mpembe I, et al. NASPOT 11’, a sweetpotato cultivar bred by a participatory plant-breeding approach in Uganda. HortScience. 2009;46(2):317–21.10.21273/HORTSCI.46.2.317Suche in Google Scholar

[20] Lamo J, Ochan D, Abebe D, Zewdu Ayalew Z, Mlaki A, Ndikuryayo C. Irrigated and rain-fed lowland rice breeding in Uganda: a review. Cereal Grains. 2021;2. 10.5772/intechopen.97157.Suche in Google Scholar

[21] Rajendran S, Kimenye LN, McEwan M. Strategies for the development of the sweetpotato early generation seed sector in eastern and southern Africa. Open Agric. 2017;2(1):236–43.10.1515/opag-2017-0025Suche in Google Scholar

[22] Yu CC, Hung KT, Kao CH. Nitric oxide reduces Cu toxicity and Cu-induced NH4+ accumulation in rice leaves. J Plant Physiol. 2006;162(12):1319–30. 10.1016/j.jplph.2005.02.003.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[23] Ning YW, Zhang H, Xu X-J, Ma H-B, Zhang Y-C. Full application of potassium fertilizer in sweet potato to increase tuber and annual yields in sweet potato/wheat rotation. J Plant Nutr Fert. 2018;24(4):935–46.Suche in Google Scholar

[24] Belesova K, Agabiirwe CN, Zou M, Phalkey R, Wilkinson P. Drought exposure as a risk factor for child undernutrition in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review and assessment of empirical evidence. Environ Int. 2019;131:104973. 10.1016/j.envint.2019.104973.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[25] Thierfelder C, Wall PC. Rotation in conservation agriculture systems of Zambia: effects on soil quality and water relations. Exp Agric. 2010;46(3):309–25. 10.1017/s001447971000030x.Suche in Google Scholar

[26] Young H, Plumpton H, Miret Barrio JA, Cornforth RJ, Petty C, Todman L, et al. Sweet potato production in Uganda in a changing climate: what is the role for fertilisers. Working paper. Walker Institute; 2020. p. 8.Suche in Google Scholar

[27] Deb P, Debnath P, Pattanaaik SK. Physico-chemical properties and water holding capacity of cultivated soils along altitudinal gradient in South Sikkim, India. Indian J Agric Res. 2013;48(2):120–6.10.5958/j.0976-058X.48.2.020Suche in Google Scholar

[28] Lukonge EJ, Gibson RW, Laizer L, Amour R, Phillips DP. Delivering new technologies to the Tanzanian sweetpotato crop through its informal seed system. Agroecol Sustainable Food Syst. 2015;39(8):861–84.10.1080/21683565.2015.1046537Suche in Google Scholar

[29] Namanda S, Amour R, Gibson RW. The triple S method of producing sweet potato planting material for areas in Africa with long dry seasons. J Crop Improv. 2013;27(1):67–84. 10.1080/15427528.2012.727376.Suche in Google Scholar

[30] Nedunchezhiyan M, Byju G, Ravi V. Photosynthesis, dry matter production and partitioning in cassava (Manihot esculenta Crantz) under partial shade of a coconut plantation. J Root Crops. 2013;38(2):116.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Regular Articles

- Supplementation of P-solubilizing purple nonsulfur bacteria, Rhodopseudomonas palustris improved soil fertility, P nutrient, growth, and yield of Cucumis melo L.

- Yield gap variation in rice cultivation in Indonesia

- Effects of co-inoculation of indole-3-acetic acid- and ammonia-producing bacteria on plant growth and nutrition, soil elements, and the relationships of soil microbiomes with soil physicochemical parameters

- Impact of mulching and planting time on spring-wheat (Triticum aestivum) growth: A combined field experiment and empirical modeling approach

- Morphological diversity, correlation studies, and multiple-traits selection for yield and yield components of local cowpea varieties

- Participatory on-farm evaluation of new orange-fleshed sweetpotato varieties in Southern Ethiopia

- Yield performance and stability analysis of three cultivars of Gayo Arabica coffee across six different environments

- Biology of Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) on different types of plants feeds: Potency as a pest on various agricultural plants

- Antidiabetic activity of methanolic extract of Hibiscus sabdariffa Linn. fruit in alloxan-induced Swiss albino diabetic mice

- Bioinformatics investigation of the effect of volatile and non-volatile compounds of rhizobacteria in inhibiting late embryogenesis abundant protein that induces drought tolerance

- Nicotinamide as a biostimulant improves soybean growth and yield

- Farmer’s willingness to accept the sustainable zoning-based organic farming development plan: A lesson from Sleman District, Indonesia

- Uncovering hidden determinants of millennial farmers’ intentions in running conservation agriculture: An application of the Norm Activation Model

- Mediating role of leadership and group capital between human capital component and sustainability of horticultural agribusiness institutions in Indonesia

- Biochar technology to increase cassava crop productivity: A study of sustainable agriculture on degraded land

- Effect of struvite on the growth of green beans on Mars and Moon regolith simulants

- UrbanAgriKG: A knowledge graph on urban agriculture and its embeddings

- Provision of loans and credit by cocoa buyers under non-price competition: Cocoa beans market in Ghana

- Effectiveness of micro-dosing of lime on selected chemical properties of soil in Banja District, North West, Ethiopia

- Effect of weather, nitrogen fertilizer, and biostimulators on the root size and yield components of Hordeum vulgare

- Effects of selected biostimulants on qualitative and quantitative parameters of nine cultivars of the genus Capsicum spp.

- Growth, yield, and secondary metabolite responses of three shallot cultivars at different watering intervals

- Design of drainage channel for effective use of land on fully mechanized sugarcane plantations: A case study at Bone Sugarcane Plantation

- Technical feasibility and economic benefit of combined shallot seedlings techniques in Indonesia

- Control of Meloidogyne javanica in banana by endophytic bacteria

- Comparison of important quality components of red-flesh kiwifruit (Actinidia chinensis) in different locations

- Efficiency of rice farming in flood-prone areas of East Java, Indonesia

- Comparative analysis of alpine agritourism in Trentino, Tyrol, and South Tyrol: Regional variations and prospects

- Detection of Fusarium spp. infection in potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) during postharvest storage through visible–near-infrared and shortwave–near-infrared reflectance spectroscopy

- Forage yield, seed, and forage qualitative traits evaluation by determining the optimal forage harvesting stage in dual-purpose cultivation in safflower varieties (Carthamus tinctorius L.)

- The influence of tourism on the development of urban space: Comparison in Hanoi, Danang, and Ho Chi Minh City

- Optimum intra-row spacing and clove size for the economical production of garlic (Allium sativum L.) in Northwestern Highlands of Ethiopia

- The role of organic rice farm income on farmer household welfare: Evidence from Yogyakarta, Indonesia

- Exploring innovative food in a developing country: Edible insects as a sustainable option

- Genotype by environment interaction and performance stability of common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) cultivars grown in Dawuro zone, Southwestern Ethiopia

- Factors influencing green, environmentally-friendly consumer behaviour

- Factors affecting coffee farmers’ access to financial institutions: The case of Bandung Regency, Indonesia

- Morphological and yield trait-based evaluation and selection of chili (Capsicum annuum L.) genotypes suitable for both summer and winter seasons

- Sustainability analysis and decision-making strategy for swamp buffalo (Bubalus bubalis carabauesis) conservation in Jambi Province, Indonesia

- Understanding factors affecting rice purchasing decisions in Indonesia: Does rice brand matter?

- An implementation of an extended theory of planned behavior to investigate consumer behavior on hygiene sanitation-certified livestock food products

- Information technology adoption in Indonesia’s small-scale dairy farms

- Draft genome of a biological control agent against Bipolaris sorokiniana, the causal phytopathogen of spot blotch in wheat (Triticum turgidum L. subsp. durum): Bacillus inaquosorum TSO22

- Assessment of the recurrent mutagenesis efficacy of sesame crosses followed by isolation and evaluation of promising genetic resources for use in future breeding programs

- Fostering cocoa industry resilience: A collaborative approach to managing farm gate price fluctuations in West Sulawesi, Indonesia

- Field investigation of component failures for selected farm machinery used in small rice farming operations

- Near-infrared technology in agriculture: Rapid, simultaneous, and non-destructive determination of inner quality parameters on intact coffee beans

- The synergistic application of sucrose and various LED light exposures to enhance the in vitro growth of Stevia rebaudiana (Bertoni)

- Weather index-based agricultural insurance for flower farmers: Willingness to pay, sales, and profitability perspectives

- Meta-analysis of dietary Bacillus spp. on serum biochemical and antioxidant status and egg quality of laying hens

- Biochemical characterization of trypsin from Indonesian skipjack tuna (Katsuwonus pelamis) viscera

- Determination of C-factor for conventional cultivation and soil conservation technique used in hop gardens

- Empowering farmers: Unveiling the economic impacts of contract farming on red chilli farmers’ income in Magelang District, Indonesia

- Evaluating salt tolerance in fodder crops: A field experiment in the dry land

- Labor productivity of lowland rice (Oryza sativa L.) farmers in Central Java Province, Indonesia

- Cropping systems and production assessment in southern Myanmar: Informing strategic interventions

- The effect of biostimulants and red mud on the growth and yield of shallots in post-unlicensed gold mining soil

- Effects of dietary Adansonia digitata L. (baobab) seed meal on growth performance and carcass characteristics of broiler chickens: A systematic review and meta-analysis

- Analysis and structural characterization of the vid-pisco market

- Pseudomonas fluorescens SP007s enhances defense responses against the soybean bacterial pustule caused by Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. glycines

- A brief investigation on the prospective of co-composted biochar as a fertilizer for Zucchini plants cultivated in arid sandy soil

- Supply chain efficiency of red chilies in the production center of Sleman Indonesia based on performance measurement system

- Investment development path for developed economies: Is agriculture different?

- Power relations among actors in laying hen business in Indonesia: A MACTOR analysis

- High-throughput digital imaging and detection of morpho-physiological traits in tomato plants under drought

- Converting compression ignition engine to dual-fuel (diesel + CNG) engine and experimentally investigating its performance and emissions

- Structuration, risk management, and institutional dynamics in resolving palm oil conflicts

- Spacing strategies for enhancing drought resilience and yield in maize agriculture

- Composition and quality of winter annual agrestal and ruderal herbages of two different land-use types

- Investigating Spodoptera spp. diversity, percentage of attack, and control strategies in the West Java, Indonesia, corn cultivation

- Yield stability of biofertilizer treatments to soybean in the rainy season based on the GGE biplot

- Evaluating agricultural yield and economic implications of varied irrigation depths on maize yield in semi-arid environments, at Birfarm, Upper Blue Nile, Ethiopia

- Chemometrics for mapping the spatial nitrate distribution on the leaf lamina of fenugreek grown under varying nitrogenous fertilizer doses

- Pomegranate peel ethanolic extract: A promising natural antioxidant, antimicrobial agent, and novel approach to mitigate rancidity in used edible oils

- Transformative learning and engagement with organic farming: Lessons learned from Indonesia

- Tourism in rural areas as a broader concept: Some insights from the Portuguese reality

- Assessment enhancing drought tolerance in henna (Lawsonia inermis L.) ecotypes through sodium nitroprusside foliar application

- Edible insects: A survey about perceptions regarding possible beneficial health effects and safety concerns among adult citizens from Portugal and Romania

- Phenological stages analysis in peach trees using electronic nose

- Harvest date and salicylic acid impact on peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.) properties under different humidity conditions

- Hibiscus sabdariffa L. petal biomass: A green source of nanoparticles of multifarious potential

- Use of different vegetation indices for the evaluation of the kinetics of the cherry tomato (Solanum lycopersicum var. cerasiforme) growth based on multispectral images by UAV

- First evidence of microplastic pollution in mangrove sediments and its ingestion by coral reef fish: Case study in Biawak Island, Indonesia

- Physical and textural properties and sensory acceptability of wheat bread partially incorporated with unripe non-commercial banana cultivars

- Cereibacter sphaeroides ST16 and ST26 were used to solubilize insoluble P forms to improve P uptake, growth, and yield of rice in acidic and extreme saline soil

- Avocado peel by-product in cattle diets and supplementation with oregano oil and effects on production, carcass, and meat quality

- Optimizing inorganic blended fertilizer application for the maximum grain yield and profitability of bread wheat and food barley in Dawuro Zone, Southwest Ethiopia

- The acceptance of social media as a channel of communication and livestock information for sheep farmers

- Adaptation of rice farmers to aging in Thailand

- Combined use of improved maize hybrids and nitrogen application increases grain yield of maize, under natural Striga hermonthica infestation

- From aquatic to terrestrial: An examination of plant diversity and ecological shifts

- Statistical modelling of a tractor tractive performance during ploughing operation on a tropical Alfisol

- Participation in artisanal diamond mining and food security: A case study of Kasai Oriental in DR Congo

- Assessment and multi-scenario simulation of ecosystem service values in Southwest China’s mountainous and hilly region

- Analysis of agricultural emissions and economic growth in Europe in search of ecological balance

- Bacillus thuringiensis strains with high insecticidal activity against insect larvae of the orders Coleoptera and Lepidoptera

- Technical efficiency of sugarcane farming in East Java, Indonesia: A bootstrap data envelopment analysis

- Comparison between mycobiota diversity and fungi and mycotoxin contamination of maize and wheat

- Evaluation of cultivation technology package and corn variety based on agronomy characters and leaf green indices

- Exploring the association between the consumption of beverages, fast foods, sweets, fats, and oils and the risk of gastric and pancreatic cancers: Findings from case–control study

- Phytochemical composition and insecticidal activity of Acokanthera oblongifolia (Hochst.) Benth & Hook.f. ex B.D.Jacks. extract on life span and biological aspects of Spodoptera littoralis (Biosd.)

- Land use management solutions in response to climate change: Case study in the central coastal areas of Vietnam

- Evaluation of coffee pulp as a feed ingredient for ruminants: A meta-analysis

- Interannual variations of normalized difference vegetation index and potential evapotranspiration and their relationship in the Baghdad area

- Harnessing synthetic microbial communities with nitrogen-fixing activity to promote rice growth

- Agronomic and economic benefits of rice–sweetpotato rotation in lowland rice cropping systems in Uganda

- Response of potato tuber as an effect of the N-fertilizer and paclobutrazol application in medium altitude

- Bridging the gap: The role of geographic proximity in enhancing seed sustainability in Bandung District

- Evaluation of Abrams curve in agricultural sector using the NARDL approach

- Challenges and opportunities for young farmers in the implementation of the Rural Development Program 2014–2020 of the Republic of Croatia

- Yield stability of ten common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) genotypes at different sowing dates in Lubumbashi, South-East of DR Congo