Abstract

The high prevalence of food insecurity and malnutrition in Kasai Oriental, Democratic Republic of the Congo, prompted an investigation into the complex relationship between household livelihood activities and food security. Despite many rural households relying on subsistence farming, this alone may not ensure improved food security in Kasai Oriental. Consequently, non-farm sectors like artisanal mining offer a potential solution to address food insecurity among rural households. The aim of this study is to explore the association between engagement in artisanal diamond mining, food insecurity, and children’s nutritional status in Kasai Oriental. The research utilizes household cross-sectional data collected between November and December 2022. Fixed effects and Instrumental variable models were employed to address household heterogeneity and potential endogeneity related to participation in artisanal diamond activities. The regression results reveal a significant relationship between participation in artisanal diamond mining and food security. This implies that participation increases households’ cash, enabling them to access sufficient food and potentially mitigating the risk of falling into food insecurity. However, involvement in artisanal mining has not shown a significant association with children’s malnutrition. These findings call for further research on “hidden hunger.” Policies aiming to encourage and formalize artisanal diamond mining should integrate specific extension services and inform rural households about hidden hunger.

Abbreviation

- AMV

-

African Mining Vision

- BCC

-

Banque centrale du Congo

- CRONG

-

Conseil Régional des Organisations non gouvernementales de développement

- DRC

-

Democratic Republic of the Congo

- GAERN

-

Groupe d’Appui aux Exploitants des Ressources Naturelles

- HAZ

-

height-for-age

- HFIAS

-

Household Food Insecurity Access Scale

- INS

-

Institut National de Statistiques

- IV

-

instrumental variable

- PACT

-

People Acting in Community Together

- SLF

-

Sustainable livelihoods framework

- UNECA

-

United Nations Economic Commission for Africa

- WAZ

-

weight-for-age

- WHO

-

World Health Organization

1 Introduction

1.1 Artisanal mining overview

Artisanal and small-scale mining is emerging as a significant non-farm activity in developing countries. Essentially informal, characterized by low entry costs, high labor intensity, and a lack of mechanization, artisanal mining encompasses various individuals or small-group mining activities, ranging from precious stones like diamonds to industrial minerals such as tantalum, etc. [1].

The rapid growth of the population, coupled with seasonality and productivity decline in the farm sector, acute rural poverty, and poor development and integration of both secondary and tertiary sectors have made artisanal mining emerge as a crucial economic pole, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa. It serves as a vital livelihood for millions, especially those in remote rural areas [1]. By absorbing excess rural labor, it regulates rural migration, generates millions of direct jobs, and facilitates millions of other indirect jobs upstream and downstream of the mining supply chain, enabling miners and their families to meet their basic needs [2,3,4,5,6]. This catalytic role of the sector creates induced and inductive effects on the activities of local rural economies, affecting farm production, local consumption, small businesses, catering services, reinforcing then human, goods, and services mobility, etc. The presence of induced activities, in turn, becomes an attractive factor for new economic actors around mining sites, leading to a cumulative development effect through consumption [7,8,9].

Studies conducted in countries such as Angola, Sierra Leone, the Central African Republic, and Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) reinforce the idea that artisanal mining has become a structural pillar, allowing many rural households to connect to local and urban markets since it provides a significant number of jobs albeit precarious. In DRC, e.g., the sector employs a little over 700,000 direct artisanal miners, with over 1,200,000 dependents on these created jobs. It contributes significantly to the country’s gross domestic product [1,6,10].

Many rural residents participate in artisanal mining in developing countries in the search for minerals in rocky terrains, waterways, and both active and abandoned mine wells mainly during the dry season. The income generated from this activity has not only improved the living standards of participants but has also funded essential government services such as health, education, and development through taxes and other levies while supporting small businesses and household farm activities. If well-directed, then, diamond revenues can greatly benefit the economies of the regions where the stones are extracted such as in Botswana, Namibia, etc. [4,11,12,13].

However, artisanal mining raises serious socioeconomic and environmental concerns in developing countries. The massive influx of immigrants into mining zones often leads to intense land pressure, farmland expropriation, anarchic land use, and unsuitable soil conditions post-exploitation [14]. Job migration frequently results in shifts in labor allocation within rural households, with young men favoring mining over agriculture. This shift can decrease farm output, and coupled with the massive influx of miners, it increases food prices, challenging food security for rural households [15,16].

Recent studies in Ghana, Liberia, and Sierra Leone indicate that while artisanal mining provides additional income and plays an important role in rural communities, it frequently causes land degradation, water pollution, and a shift of labor from agriculture to mining. These effects create vulnerabilities in farming-dependent rural economies and potentially undermine sustainable rural development, highlighting the need for sustainable practices within the sector [17,18].

Environmental degradation is a critical issue of mining activities. Artisanal mining, including digging, washing, and sorting gravel, contributes to air and water pollution, rendering soil unsuitable for farming. Deforestation and community displacement further impact local agriculture and biodiversity. These factors significantly limit subsistence farming and agricultural productivity among local communities [19]. The negative effects are particularly concerning as smallholder farms are essential for building food security for rural households in many African countries. Research on abandoned mines in the DRC raises environmental challenges such as soil and water contamination, deforestation, and increased local conflicts, emphasizing the need for sustainable mining practices [20,21].

Additionally, artisanal mining is associated with severe issues such as child labor, moral degradation, gender inequalities, prostitution, drug-related problems, health issues, and fatal accidents. These problems arise from difficult working conditions, lack of social security, illegality, and informality [13,22,23,24].

1.2 Artisanal mining: Food security and nutrition

As highlighted in Section 1.1, artisanal mining is an undeniable source of livelihood for rural households in the Global South. Significant empirical works have flourished on this theme in recent years, since artisanal mining activities have been seen by many scholars as a complementary strategy to alleviate poverty [7,8,20,21]. This is particularly relevant given the challenges posed by rudimentary, seasonal, and low-productivity agriculture in most sub-Saharan countries [10].

The artisanal mining’s ability to create jobs, even if they are frequently precarious, makes it an alternative income-generating source that can significantly influence household poverty and compensate for the lack of opportunities for jobs in rural areas. With relatively higher returns compared to the agricultural sector in most developing countries, artisanal mining becomes a boon that attracts most young men to the extent that the volume of jobs created, and the induced external economies have a significant impact on the well-being of rural households to some extent at the expense of farm activities [15,22].

For instance, it has been in the literature observed that artisanal mining creates additional sources of income by providing seasonal employment for local communities mostly among unskilled rural young men. This additional income helps alleviate the burden of poverty and facilitates access to markets and essential services such as healthcare and education [1,16].

These studies primarily focus on the link between mining activities and poverty in communities reliant on them. However, they do not delve into the relationship between mining activities and food security.

Conversely, the study by Wegenast and Beck, dynamically addressed the intricate relationship between mining, rural livelihoods, and food security in Sub-Saharan Africa. The authors distinguish between aspects related to the distribution of property among national and international actors in the mining sector, as well as their respective impacts on food security parameters [25].

They revealed that mining activities, whether owned by national or international actors, can have both positive and negative impacts on food security, employment, and local economies. They not only highlight the potential benefits of mining, such as increased employment and infrastructure development, but also negative effects such as land dispossession, loss of access to natural resources, migratory influx, and disruptions in labor allocation within households. The combination of these elements can lead to increased living costs and make access to food difficult for local communities. In this instance, the authors found that mining activities improve access to food, particularly for men, while, on the other hand, they adversely affect child nutrition and women’s food security.

So, while beneficial to some extent, artisanal mining can be the potential channel to perpetuate transgenerational poverty, fostering a cycle of generational poverty and thus food insecurity among rural households [26].

However, the Wegenast and Beck study does not address the effects of mining at the household and local community levels, which can vary considerably depending on local and regional contexts. In the local context of Kasai Oriental, e.g., miners are marginalized in the diamond trade chain due to the informality of their work. This allows traders, traditional authorities, security services, gangs, and landowners to dominate and reap the most gains from artisanal mining. These factors severely limit the socioeconomic impact of artisanal mining on communities and households. This situation may contrast with other regions where artisanal mining is more structured and formalized [8,9,27]. Indeed, household participation in this industry can significantly affect their standard of living, access to resources, and family and community structures [9,15].

In this regard, the aim of our study is to fill this gap by specifically focusing on artisanal diamond mining activities due to their central role in the economy of Kasai Oriental since the sector’s liberalization in the early 1980s. Diamond mining is the only mineral resource exploited at both industrial and artisanal levels, providing a crucial livelihood for many households, especially in rural areas [28]. Given the sector’s socioeconomic importance and the environmental concerns associated with artisanal mining, targeted studies are necessary to explore sustainable development options for the region.

This study is grounded in the Sustainable livelihoods framework (SLF), which offers a holistic approach to understanding how various factors influence livelihoods, food security, and nutrition. The SLF allows for flexible research applications, highlighting specific aspects while considering the broader context [29,30]. Constrained in credit, time, and technology, rural households in Kasai Oriental attempt to adapt to agricultural shocks and risks by engaging in artisanal mining to earn the additional income necessary to improve their food and nutritional security as well as that of their children. Relying on this framework can allow us to understand the conditions under which household diversification into artisanal mining can or cannot lead to a sustainable development strategy in the rural areas of Kasai Oriental.

The focus of this study is on how rural households in Kasai Oriental employ their livelihood strategies to achieve well-being. Specifically, it analyzes the factors influencing household participation in diamond-based livelihoods and examines their impacts on food security and children’s nutrition. By doing so, this research seeks to enhance our understanding of the artisanal mining sector and its effects on household food security.

Our analysis provides localized insights into artisanal mining activities in this remote region and aims to fill a gap in the literature by examining the specific effects of artisanal diamond mining on household food security and children’s nutrition.

The remainder of the study is structured as follows: in Section 2, we will briefly look at the context of artisanal mining activities in Kasai Oriental. Section 3 discusses the methods and endogeneity issues. Section 4 presents the data used in the empirical analysis, Section 5 discusses the empirical results, and the last section provides some concluding remarks based on the findings.

2 Artisanal diamond mining in landlock region: Opportunities and challenges

Artisanal mining is legally recognized in the DRC by Law No. 82-039. This legislation allows adult Congolese to use non-industrial tools and methods to extract mineral substances in specific areas. This law has been the catalyst for the rapid expansion of artisanal mining, becoming, de facto, the epicenter of non-farm activities in the Kasaï Oriental region. This sector is considered a “source of rapid enrichment,” based on easily marketable precious stones [31].

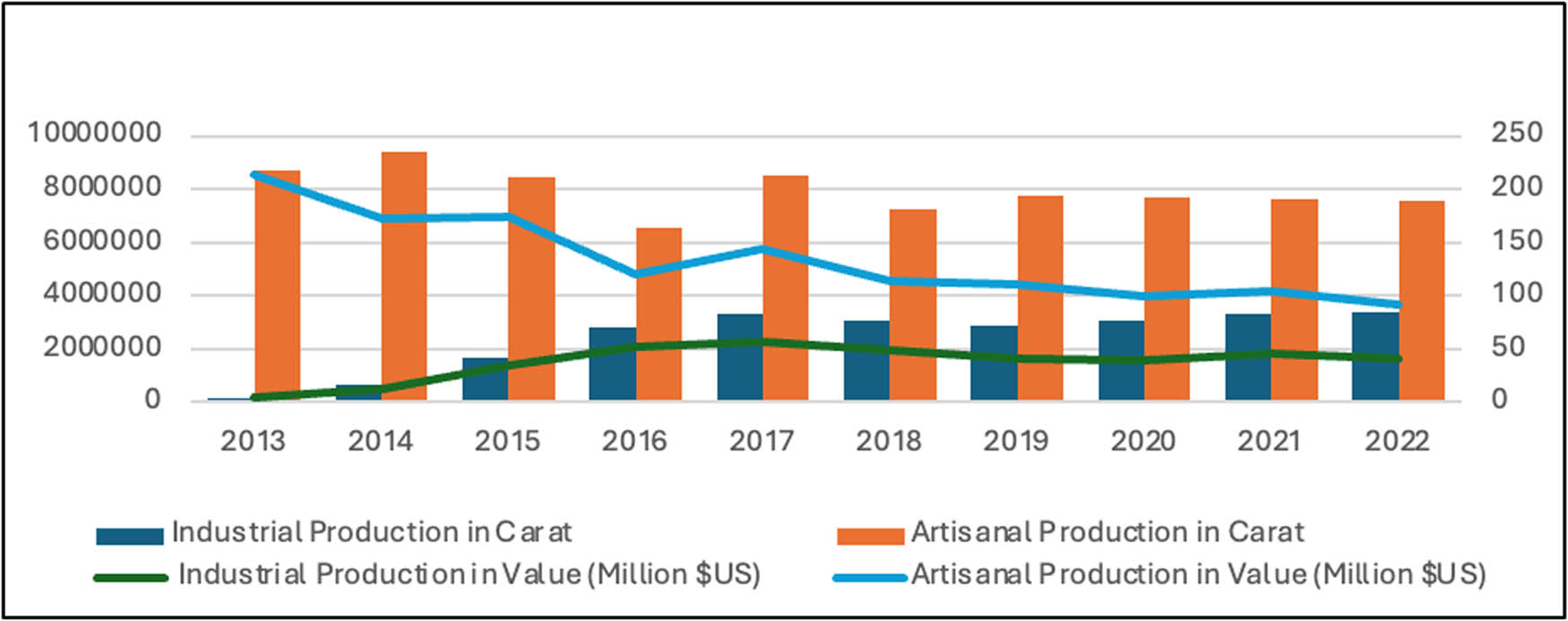

As illustrated in Figure 1, despite production fluctuations due to variations in global market prices, depletion of alluvial deposits, etc., artisanal diamond mining remains a significant source of jobs in rural areas of Kasai Oriental. Its low entry cost makes it the most non-farm important job provider sector, especially among young men aged 18–45, often lacking skills for farming and other non-farm activities.

Industrial versus Artisanal Diamond Production in Kasai Oriental (in carat and in value US$). Source: Treated data from Division Provinciale des Mines et Hydrocarbures and BCC, 2022.

Thousands of young men, frequently heads of households, who are involved in diamond artisanal activities, often lack formal training or mining training to work as artisanal miners. The majority are unskilled workers using very basic tools. They do not have geological expertise, or any other skills related to artisanal mining. Most of them are either underemployed in agriculture or struggle to find alternative jobs. Hence, some fully depend on mining for their income, while others use it occasionally to supplement their earnings [16,32].

However, the strong dependence on artisanal diamond mining exposes some households and the regional economy to significant vulnerability in the event of a sharp drop in diamond prices in global markets. This results in a reduction in household income and purchasing power for food, as observed during the periods 2008–2011 and 2018–2021 [25,33].

In the other chapter, it is interesting to note that the coexistence of artisanal diamond mining with the agriculture sector in Kasai Oriental leads frequently to a complex relationship between these two sectors [10].

On one hand, the strong expansion of artisanal diamond mining constitutes an important source of income for rural households, which can help alleviate poverty and improve livelihoods, especially during farm off-seasons. Furthermore, the potential cash from artisanal diamond mining can also help to access improved inputs and technology for farm, which can be beneficial to increase farm productivity [28].

On the other hand, artisanal diamond mining can also have negative impacts on agriculture and food security. The relatively higher incomes from artisanal diamond mining can lead to diverting labor from agriculture, resulting in a shortage of labor for agricultural activities, a decline in agricultural production, and competition for arable land [16].

Farmers who engage in artisanal diamond mining activities often allocate less labor and resources to agriculture, resulting in less intensive land management practices and potentially lower yields. This is because diamond mining requires significant time and effort, diverting attention and labor away from agricultural activities. Moreover, the influx of miners to mining areas due to the discovery of profitable mining deposits can disrupt local communities and local farming practices, leading to conflicts over land use and social tensions [25,34].

Miner migrations frequently harm farm livelihood activities and household resource allocations. Furthermore, they often lead to the formation of “diamond micro-economies” in situ, where mining earnings are frequently spent on alcohol and social interactions within these spontaneous local economies, rather than being allocated to improving household well-being [13].

However, artisanal mining is often perceived today as having generally negative consequences on the human environment despite the benefits that rural households and local communities can derive from it. In Kasai Oriental, artisanal mining is frequently associated with landslides and fatal accidents, and socio-economic and health harm to workers and local populations. It generates significant environmental damage, including CO2 emissions, dust potentially laden with heavy metals, pollution of surface and/or groundwater, land subsidence, loss of biodiversity, and sometimes deadly conflicts among local populations. Additionally, it fosters the development of corruption, fraud, and tax evasion, notably due to the opacity of the artisanal diamond trade chain [13,32]. These combined factors can hinder the effectiveness of artisanal diamond mining beside agriculture as a viable livelihood strategy to tackle rural food insecurity and poverty.

3 Methods

3.1 Study design, sample size, and sampling frame

Among the 26 regions in DRC, Kasai Oriental stands out as one of the most impoverished and food-insecure areas. Located in the central part of DRC, its unfavorable geography makes it a landlocked region, with about 70% of the population residing in rural areas [35]. For this study, the data were collected through a cross-sectional household-based survey conducted in Kasai Oriental from November 17 to December 20, 2022, a rain and pre-harvest period characterized by hikes in food prices in the market. The study included variables at both the household and individual levels in rural areas, encompassing 310 households with 233 identified children to ensure a regionally representative sample.

Thus, we used a multi-stage sampling approach, combining purposive and simple random sampling methods, to ensure a representative sample across rural Kasai Oriental. Our sampling strategy comprised four levels. Initially, we purposively selected five rural health zones out of the nine in Kasai Oriental, ensuring each zone represented diverse administrative territories, geographic regions, and demographic characteristics. Within each selected health zone, we purposively chose 6–7 health areas from the 147 rural health areas, proportional to their demographic and geographic size to ensure representativeness. This stratified sampling approach included both densely and sparsely populated areas.

A simple random sampling technique using random numbers generated in Excel software 16 was employed to select villages and households for the survey from a list provided by local authorities and community leaders to minimize selection bias. However, we acknowledged that recent migrants or informal settlers might not be included in the village lists. If a selected household was unavailable or unwilling to participate, we used a replacement strategy, selecting the next household on the list. To circumvent this, we cross-referenced official lists with information from community health workers and local informants for better coverage.

The selection of 10 households per village was based on our sample size calculation, aiming for a cluster sample design of 310 households. This calculation was based on a food insecurity rate of 72% in Kasai Oriental, with Zα (the critical value for a two-tailed test at a 95% confidence level) of 1.96, and a margin of error (m) of 0.5, resulting in a sample size of 309, rounded up to 310. Consequently, we selected 10 households in each of the 31 villages.

3.2 Data collection and field procedure

The survey questions were translated into Tshiluba, the vernacular language spoken in Kasai Oriental, and pre-tested to ensure consistency and comprehensibility. During the survey, all questions were administered in Tshiluba using the KoboCollect tool phone-based survey. The data collection process involved three teams, each comprising two surveyors, making a total of six investigators. All of them were well-trained persons with prior experience in data collection with Catholic Relief Services and Action Contre la Faim in the Kasai Oriental.

Before the survey, all investigators received a comprehensive 5 days training in Mbuji Mayi, which included testing the questionnaires. Prior starting the survey, we discussed and obtained informed consent from all household representatives. We explained the study's purpose, their rights as participants, and how we would keep their information confidential to ensure they fully understood and agreed to participate. This approach helped us uphold ethical standards and establish trust with the participants before gathering any data. The collected data cover various aspects, including household demographics, socio-economic status, livelihood activities, and institutional circumstances. Specific information was gathered on household size, education level, and profession of the head of the household, sources of income, food security, access to markets and land, participation in mining activities, resource management, anthropometry, and child nutrition. Anthropometric data were collected from children aged 0–59 months, focusing on their height (in cm), weight (in kg), gender, and age. Mechanical weighing scales with an accuracy of 0.1 kg, and local wood infantometer measures with an accuracy of 0.1 cm, were used to gather these data. Children’s ages and birthdates were determined through memory recall and, when available, cross-verified with health, Christian, or administrative records. Data analysis was conducted using STATA 14 software. The data were summarized through descriptive statistics, including mean differences, cross-tabulations, linear fixed effects, and instrumental variable (IV) fixed effects models, to establish relationships between outcome variables and the variable of interest.

-

Ethical approval: The standard survey protocols, questionnaires, and anthropometric procedures related to children under 5 years old were reviewed and approved by the Medical Research Ethics Committee at the University of Mbuji Mayi in the Democratic Republic of Congo. The trial was officially registered under the reference number N/Ref:01/MREC/UM/NKL/2022 on September 14th, 2022.

-

Informed consent: Informed consent has been obtained from all household representatives.

3.3 Study outcome variables

In this study, we utilized the 9-item Household Food Insecurity Access Scale (HFIAS) module to assess households’ food security. This module is widely adopted as a standard measure of household food security in many African countries [28,29,30]. The HFIAS 9-item involves assigning raw scores based on specific household answers. Each question has four alternative codes: “0” for a “No” answer indicating no occurrence, “1” for rare, “2” for sometimes, and “3” for often.

The possible raw scores for any household range from 0 to 27, where 0 characterizes households as food secure and 27 as extremely food insecure [36]. Before using these raw scores, we checked for the internal consistency and reliability analysis of HFIAS questions. In this respect, Cronbach’s alpha score of 93.8% proved that the HFIAS 9-item had good internal consistency so that the data collected from them are reliable to analyze the food security in Kasai Oriental (see Appendix Table A1 for detail).

In another chapter, for assessing children’s nutritional status, we followed the World Health Organization (WHO) child growth reference and used anthropometric measures to establish three outcomes: height-for-age (HAZ) and weight-for-age (WAZ) indicators. We employed the Stata package zscore06 to generate z-scores based on the WHO’s growth standards [37]. The HAZ serves as an index to identify past undernutrition or chronic malnutrition. The WAZ is a composite indicator that provides information on changes in the prevalence of malnutrition over time. Children with HAZ and WAZ below minus two standard deviations (−2SD) from the WHO child growth reference are stunted and underweighted, respectively [37]. Missing data on height, weight, age, and gender, as well as measurement or coding errors, were excluded from our analyses. To achieve this, we applied WHO cut-off points for each child’s nutrition outcome for HAZ and WAZ, respectively. As a result, children with values falling within the following intervals were excluded: HAZ, ≤−6 or ≥6 SD; and WAZ, ≤−6 or ≥5 SD.

Thus, HFIAS raw scores and anthropometric z-scores are used in this study as continuous outcome variables.

3.4 Variable of interest and other variables

This study focuses on participation in artisanal diamond activities as the main variable of interest. It is coded as “1” for households with at least one adult who participated in artisanal mining during the last 30 days and “0” for all others. For an in-depth analysis, we also systematically control certain other variables. These additional factors are carefully selected considering their relevance to household food insecurity and poverty in many empirical studies [31,38,39]. They include household size and household head characteristics such as gender, level of education, marital status, and age. In addition, we include household dependency ratio, access to land, road conditions, livestock ownership, and household resource management. We also include other individual variables on children (gender, age) and the mother’s age. Since early marriages and births are still common in rural areas, young mothers often lack childcare experience, which can affect their children’s nutrition [40]. In regression analysis, this is especially important to consider in children under five because women play a primary role in childcare in this Kasai Oriental [10,37].

3.5 Empirical and estimation procedures

Given that the link between involvement in artisanal mining activities, food security, and children’s nutrition status remains little explored in empirical studies in Kasai Oriental, we employ village fixed effects along with instrumental variables models to capture the types of associations that exist in those variables while attempting to address the individual heterogeneity and the potential endogeneity of engagement in these activities. Household participation in artisanal diamond mining in Kasai Oriental is voluntary so it depends on various decision-making factors specific to each household, and thus an endogenous variable that ideally should be instrumented. Finding valid and appropriate instruments that meet relevance corr

Considering the approach, we identify and select potential instruments to be included in the regression. These are artisanal mining sites’ presence in sub-areas and the unemployment rate by territory. The presence of mining sites in sub-areas or not is expected to be a motivating factor for artisanal diamond participation. The unemployment rate reflects differences in unemployment distribution across territories, potentially leading individuals without jobs to engage in artisanal diamond activities. The instrumental variables were collected through the Division of Mines and Hydrocarbons and the Division of Labor and Social Foresight [37,44,45].

We applied the standard heuristic relevance threshold criterion (F > 10) to identify statistically significant associations between instruments and our endogenous variable. The results revealed the relevance of our instruments and are the motivating factor of participation in artisanal diamond mining. To assess under-identification, instrument strengths, and over-identification, respectively, we employed the Anderson–Rubin Wald test and Stock–Wright LM S statistic joint tests for robust inference with weak instruments. We also employed the Cragg–Donald and Kleibergen–Paap (1993) statistics based on the Stock and Yogo (2005) criteria for assessing instrument weakness, along with the over-identification test based on the Sargan–Hansen (1982) J-statistic. The results of these tests confirm the strength and reliability of our instruments (Table 6).

Following the work of Colin Cameron and Miller to account for possible heteroscedasticity and autocorrelation, robust standard errors clustered at village levels have been employed to improve the accuracy and reliability of associations that exist between engagement in artisanal mining activities, household food security, and children’s health conditions [46]. The key equations used in this study are as follows:

Participation equation

Food insecurity equation

Children’s nutritional equation

where

So, the statistical models in this study are implemented using a robust methodological framework that combines linear village fixed effects and instrumental variables to address endogeneity and heterogeneity. The Instrumental variable (IV) estimation is implemented in two steps. First, using the selected instruments, a binary response model is used to fit the participation in artisanal diamond mining. In the second step, the values of food security and children’s anthropometry outcomes are regressed on participation in artisanal diamond mining and other household characteristics. Standard errors are clustered at the village level to correct for possible heteroscedasticity and autocorrelation, enhancing the reliability of the results. The IV models address endogeneity issues while fixed effects are included to control for unobserved time-invariant heterogeneity [47,48,49]. Combining these methods allows for a more robust analysis by addressing both types of biases. Data treatment and estimation methods were implemented using Excel 16 and STATA 14.2 software (StataCorp, USA) (Table 1).

9-HFIAS Questions

| No. | Questions for the past 4 weeks prior to survey |

|---|---|

| 1 | Did you worry that your household would not have enough food? |

| 2 | Were you or any household member not able to eat the kinds of foods you preferred because of lack of resources? |

| 3 | Did you or any household member have to eat a limited variety of foods due to lack of resources? |

| 4 | Did you or any household member have to eat some foods that you really did not want to eat because of lack of resources to obtain other types of food? |

| 5 | Did you or any household member have to eat a smaller meal than you felt you needed because there was not enough food? |

| 6 | Did you or any household member have to eat fewer meals in a day because there was not enough food? |

| 7 | Was there ever no food to eat of any kind in your household because of lack of resources to get food? |

| 8 | Did you or any household member go to sleep at night hungry because there was not enough food? |

| 9 | Did you or any household member go a whole day and night without eating anything because there was not enough food? |

4 Descriptive and regression results

4.1 Descriptive statistics

In total, 308 households were analyzed based on the HFIAS questionnaire. A significant proportion of households in Kasai Oriental have experienced food insecurity in all conditions (Table 2). In the first domain, 4.33% of households answered “no” in the full sample, indicating that 95.77% of sampled households felt anxious and uncertain about food availability. This proportion is similar for both participants and non-participants in artisanal diamond mining. In the second domain, the average proportion of “no” responses was 14%, suggesting that 86% of households in the full sample have insufficient food quality. However, participants have relatively better access to quality food, with 15.2% of them having access compared to 13.19% of non-participants. In the last domain, the average proportion of “no” responses was 30.58%, indicating that about 69.42% of households in the full sample have inadequate food quantity intake. Participants, on the other hand, have a slightly higher food intake at 31.36% compared to 29.93% for non-participants.

Household food security characteristics in the last 30 days (%)

| Domains | Conditions | Participant | Non-participants | Full sample |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| Anxiety and uncertainty over food | Worried about not enough food | 95.68 | 95.85 | 95.77 |

| Insufficient quality food | Unable to eat preferred food | 89.2 | 92.89 | 91.24 |

| Ate just few kinds of food | 83.47 | 86.98 | 85.38 | |

| Ate unwanted foods | 82.74 | 81.56 | 81.5 | |

| Insufficient food intake | Ate a smaller quantity than desired at a meal | 84.18 | 83.44 | 83.77 |

| Ate fewer meals in a day than desired | 66.89 | 73.79 | 70.13 | |

| Had no food of any kind | 59 | 57.22 | 57.47 | |

| Went to sleep at night hungry | 64.75 | 66.87 | 65.9 | |

| Went without food over a day and night | 68.34 | 71 | 69.8 |

In Table 3, we can observe that the distribution of HAZ and WAZ dimensions between non-participant and participant households shows a slightly similar pattern. The mean difference in both dimensions of children’s health is not statistically significant, suggesting that there is likely no difference in the health conditions of children between participants and non-participants in artisanal diamond mining in rural households in Kasai Oriental.

Children’s anthropometric z-score distribution

| Variables | Participants | Non-participants | Full sample | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean | SD | Min | Max | N | Mean | SD | Min | Max | N | Mean | SD | Min | Max | P-values | |

| HAZ | 84 | −2.28 | 2.85 | −5.96 | 5.82 | 100 | −1.66 | 2.65 | −5.82 | 5.83 | 184 | −1.94 | 2.75 | −5.96 | 5.83 | 0.129 |

| WAZ | 88 | −1.67 | 2.44 | −5.75 | 4.30 | 104 | −1.86 | 2.25 | −5.60 | 3.22 | 192 | −1.77 | 2.33 | −5.75 | 4.30 | 0.674 |

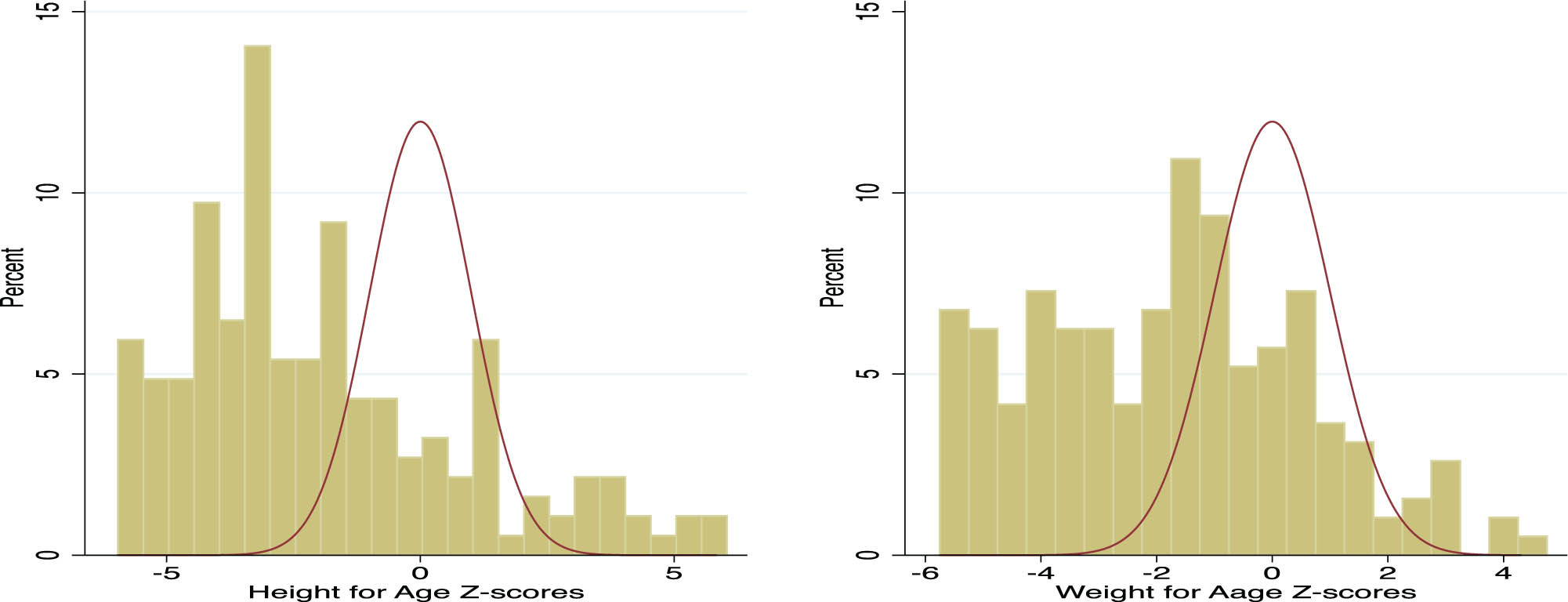

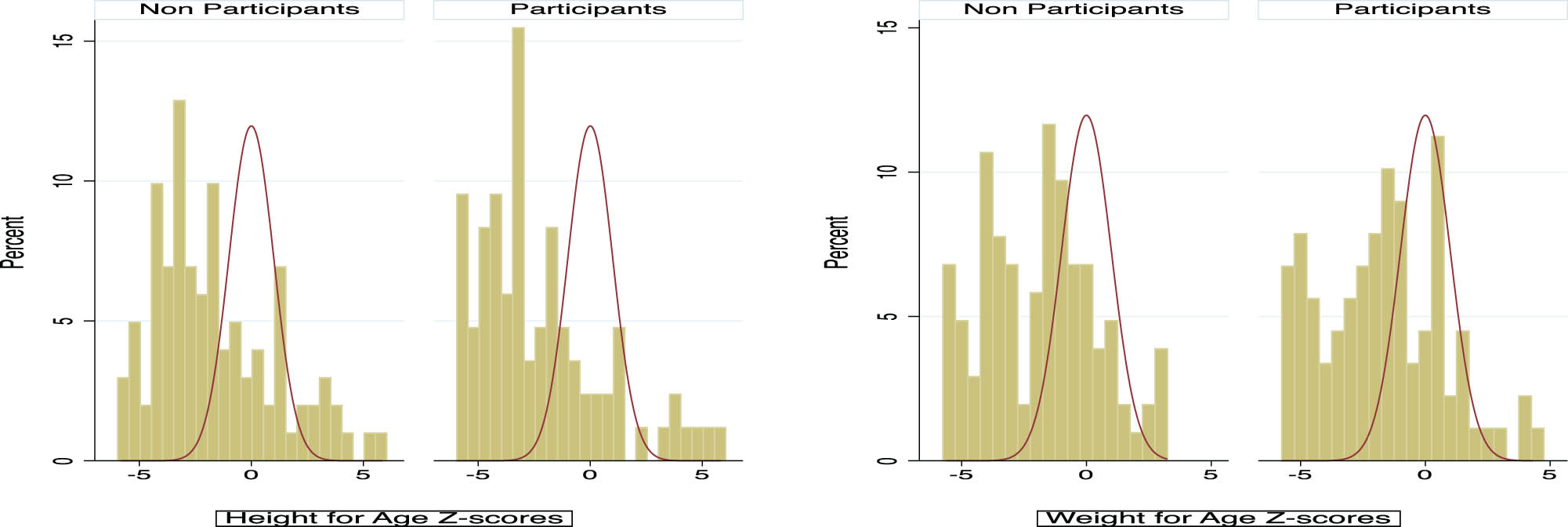

Figures 2 and 3, and Table 4, respectively, present the overall distribution of HAZ and WAZ based on participation in artisanal diamond mining while disaggregating the extent of malnutrition in both a general and gender-specific breakdown. The analysis by gender reveals a predominance of boys experiencing stunting, underweight, and wasting. Overall, in the examined sample, 56.21% of children exhibit stunting (HAZ < −2 SD), and 44.79% are underweight (WAZ < −2 SD), these figures single out leftward-skewed distribution across, indicating the prevalence of malnutrition in the Kasai Oriental region (Figures 2 and 3).

Children’s anthropometric outcomes distribution.

Children’s anthropometric outcome distributions by artisanal diamond participation.

Children’s gender z-score distribution

| HAZ | WAZ | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Z-scores ≤ −2 SD | Z-scores ≤ −2 SD | |||

| Frequency | Percent | Frequency | Percent | |

| Child-sex | ||||

| Female | 42 | 22.70 | 33 | 17.19 |

| Male | 62 | 33.51 | 53 | 27.60 |

| Total | 104 | 56.21 | 86 | 44.79 |

Table 5 displays descriptive statistics of variables categorized by diamond participation in the econometric models. We find significant differences between those involved in artisanal diamond activities and those who are not. On average, participants experience lower levels of food insecurity, with a mean score of 15.82, compared to 17.15 for non-participants. This difference is statistically significant at the 1% level based on t-test results.

Descriptive statistics and variable definitions

| Variables | Participant n = 139 (45.1%) | Non-participant n = 169 (55.9%) | Full sample n = 308 (100%) | P-values | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Interest variable participation | |||||||

| Household participation during last 30 days = 1 | 0.451 | 0.498 | |||||

| Dependent variables | |||||||

| HFIAS raw scores (continuous: 0–27) | 15.82 | 8.547 | 17.15 | 8.027 | 16.55 | 8.279 | ∼0.00 |

| Independent household variables | |||||||

| 1 if married, 0 otherwise | 0.978 | 0.146 | 0.994 | 0.076 | 0.987 | 0.113 | 0.222 |

| Household head is Male = 1 | 0.935 | 0.247 | 0.935 | 0.247 | 0.935 | 0.247 | 0.986 |

| Household head age in years (continuous) | 41.47 | 9.766 | 41.81 | 10.58 | 41.66 | 10.21 | 0.720 |

| Household size (continuous) | 5.532 | 1.625 | 5.722 | 1.531 | 5.636 | 1.575 | 0.315 |

| Household dependency ratio (continuous) | 3.514 | 1.585 | 3.435 | 1.427 | 3.471 | 1.498 | 0.539 |

| Head education level achieved | |||||||

| 1 if illiterate, 0 otherwise | 0.259 | 0.440 | 0.154 | 0.362 | 0.201 | 0.402 | ∼0.039 |

| 1 if primary, 0 otherwise | 0.288 | 0.454 | 0.349 | 0.478 | 0.321 | 0.468 | 0.285 |

| 1 if secondary, 0 otherwise | 0.374 | 0.486 | 0.391 | 0.489 | 0.383 | 0.487 | 0.838 |

| 1 if state diploma, 0 otherwise | 0.079 | 0.271 | 0.107 | 0.309 | 0.094 | 0.293 | 0.434 |

| Land access mode | |||||||

| 1 if inheritance, 0 otherwise | 0.619 | 0.487 | 0.639 | 0.482 | 0.630 | 0.484 | 0.648 |

| 1 if purchased, 0 otherwise | 0.129 | 0.337 | 0.124 | 0.331 | 0.127 | 0.333 | 0.856 |

| 1 if gifts/donations, 0 otherwise | 0.252 | 0.436 | 0.237 | 0.426 | 0.244 | 0.430 | 0.709 |

| Road status | |||||||

| 1 if fair, 0 otherwise | 0.245 | 0.431 | 0.243 | 0.430 | 0.244 | 0.430 | 0.872 |

| 1 if poor, 0 otherwise | 0.597 | 0.492 | 0.527 | 0.501 | 0.558 | 0.497 | 0.171 |

| 1 if very poor, 0 otherwise | 0.158 | 0.366 | 0.231 | 0.423 | 0.198 | 0.399 | 0.125 |

| Household income management | |||||||

| 1 if male, 0 otherwise | 0.568 | 0.497 | 0.568 | 0.497 | 0.568 | 0.496 | 0.925 |

| 1 if female, 0 otherwise | 0.151 | 0.359 | 0.130 | 0.337 | 0.140 | 0.347 | 0.567 |

| 1 if cooperation, 0 otherwise | 0.281 | 0.451 | 0.302 | 0.460 | 0.292 | 0.456 | 0.739 |

| Farmland size in ha (continuous) | 0.957 | 1.156 | 1.263 | 1.873 | 1.125 | 1.595 | 0.082 |

| Corn yields per hectare in kg (continuous) | 372.3 | 224.4 | 386.3 | 256.9 | 380.0 | 242.5 | ∼0.026 |

| Household holds livestock = 1 | 0.619 | 0.487 | 0.479 | 0.501 | 0.542 | 0.499 | ∼0.019 |

Furthermore, when it comes to educational attainment, non-participants have lower levels of illiteracy compared to participants, with a significant mean difference at the 5% level. On the other hand, participants are more likely to be engaged in livestock activity than non-participants, with a significant mean difference at the 5% level. While these descriptive variations do not imply causation, they suggest that there might be structural differences in food security, access to land and agricultural inputs, livestock possession, and educational opportunities between participants and non-participants.

4.2 Regression results

4.2.1 Determinants of household participation in diamond artisanal activities

The estimation of the IV-fixed effects (FE) first-stage model is presented in Table 6. The dependent variable is participation in diamond artisanal activities. The results of the regression for household participation in artisanal activities have shown that the territory of residence of households, and the level of territorial unemployment, as instruments, have a statistically significant influence at 5% levels on households’ decisions to participate in these mining activities (Table 6).

Determinants of diamond participation in Kasai Oriental

| Variables | (1) | (2) |

|---|---|---|

| HFIAS-IV-FE | Standard errors (SE) | |

| Artisanal mining sites in areas | 0.55*** | (0.06) |

| Territorial unemployment rate | −0.09*** | (0.03) |

| Gender of head | 0.01 | (0.10) |

| Age of head | −0.00 | (0.00) |

| Marital status of head | 0.18 | (0.13) |

| Household size | −0.02 | (0.02) |

| Dependency ratio | −0.00 | (0.03) |

| Head education level achieved (ref: illiterate) | ||

| Diploma | −0.27*** | (0.08) |

| Secondary | −0.21*** | (0.08) |

| Primary | −0.19** | (0.09) |

| Road status (ref: very poor) | ||

| Poor | 0.06 | (0.07) |

| Fair | 0.11 | (0.07) |

| Income management (ref: men) | ||

| Women | 0.03 | (0.08) |

| Cooperation | −0.02 | (0.05) |

| Land access mode (ref: donations) | ||

| Inheritance | 0.01 | (0.07) |

| Purchased | 0.08 | (0.08) |

| Farmland size | −0.03*** | (0.01) |

| Corn yields | −0.00 | (0.00) |

| Livestock | 0.19*** | (0.05) |

| Observations | 308 | |

| Number of villages | 31 | |

| Wald chi2 (30) | 54.52 | |

| Prob > chi2 | 0.0000 |

Robust standard errors in parentheses ***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1.

On the other side, the results of other variables reveal that household heads with a higher level of education and households with extensive fields are less inclined to engage in these mining activities. This result suggests that households led by more educated individuals are less motivated to participate in diamond artisanal activities in Kasai Oriental. One possible explanation is that more educated individuals tend to choose activities that offer relatively safer social security and working conditions, in the tertiary sector in rural areas. This differs from artisanal diamond activities, which are physically demanding and involve risks [8].

However, this result is consistent with the Programme des Nations Unies pour le Développement findings, which revealed that individuals with lower levels of education are more inclined to engage in artisanal diamond mining in Kasai Oriental [16]. This likely underlines the difference between artisanal mining activities and other non-farm activities such as commerce, etc., where highly educated individuals are more willing to participate [50]. On the other hand, households with small farmland have an incentive to participate in mining activities. This result is in line with previous studies that found that individuals limited in access to farmland may be tempted to engage in non-farm activities to secure a reliable income stream [40,51].

Holding livestock is strongly and positively associated with artisanal diamond activities. Households holding livestock are more likely to engage in artisanal mining activities, with statistical significance below 1%. This suggests that households with a higher number of livestock are more inclined to diversify their sources of income beyond the agricultural sector alone. Often regarded in the literature as a risk management strategy, holding livestock provides income stability, which can expand access to economic opportunities, and improve market and network connections. This stability makes it easier for households to explore and diversify into non-farm income opportunities. This result aligns with the findings of a previous study that observed a positive correlation between livestock ownership and participation in some artisanal activities [52,53,54].

There is also a negative association between the age of the household head and participation in diamond artisanal activities but not at a statistically significant level, indicating that households led by younger individuals are more inclined to take risks and engage in income-generating mining activities than older household heads. Since many of artisanal jobs in Kasai Oriental are seasonal and require significant physical work, coupled with constraints on access to farmland during the lifetime of their parents or grandparents, younger households tend to seek other employment alternatives offered by the environment. This result is consistent with previous studies [16,43,55,51].

Other variables such as the condition of roads, women’s management of income, and the mode of accessing land, whether through inheritance or purchase, did not significantly influence household participation in diamond mining. This suggests that while infrastructure and income management are important, they may not be the primary factors driving artisanal mining. Although these factors show positive correlations with participation, their improvement may encourage households to engage in artisanal mining, but they are not decisive.

Previous studies indicate that poverty and the lack of alternative livelihood opportunities are the major drivers of participation in artisanal mining, rather than infrastructure, land access modes, or women’s income management [48,49]. Higher corn yields and income management through cooperation were negatively associated with participation in diamond mining, though not significantly. This suggests that better agricultural productivity and cooperative income management might provide alternative livelihoods, reducing the need to engage in mining. A study on artisanal diamond mining in Lesotho supports this, showing that mining is often a supplementary means of income or livelihood diversification in response to economic challenges. This implies that better agricultural outcomes could reduce reliance on mining [56].

4.2.2 Participation in artisanal diamond mining and household food security

Table 7 presents the estimation results on the effects of participation in artisanal diamond mining and food insecurity. To test for potential selection bias, we estimate IV regressions utilizing the unemployment rate and mining sites in sub-areas. In the IV regression, the first stage joint F-statistic had values far beyond the heuristic cutoff of 10 (Tables 7 and 8). The F-statistic tests the hypothesis that the instrument coefficients

Estimated effects of participation in artisanal diamond mining on household food security

| Variables | OLS | SE | Linear-FE | SE | HFIAS-IV-FE | SE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participation | −1.40* | (0.81) | −1.55* | (0.79) | −2.45** | (1.15) |

| Gender of head | −1.15 | (1.78) | −1.04 | (1.30) | −1.03 | (1.24) |

| Age of head | 0.01 | (0.05) | 0.04 | (0.04) | 0.04 | (0.04) |

| Marital status of head | −0.31 | (4.33) | 0.63 | (2.89) | 0.89 | (2.82) |

| Household size | −0.10 | (0.45) | 0.33 | (0.37) | 0.30 | (0.36) |

| Dependency ratio | 0.26 | (0.39) | −0.46 | (0.35) | −0.45 | (0.34) |

| Head education level achieved (ref: illiterate) | ||||||

| Diploma | −6.18*** | (2.07) | −4.45** | (2.05) | −4.71** | (1.96) |

| Secondary | −4.41** | (1.79) | −3.13** | (1.52) | −3.34** | (1.45) |

| Primary | −0.52 | (1.37) | 0.33 | (1.29) | 0.14 | (1.28) |

| Road status (ref: very poor) | ||||||

| Fair | −5.82*** | (2.07) | −3.36* | (1.86) | −3.32* | (1.79) |

| Poor | −1.27 | (1.59) | 0.37 | (1.62) | 0.42 | (1.56) |

| Income management (ref: men) | ||||||

| Women | −4.32** | (1.68) | −2.13* | (1.24) | −2.11* | (1.18) |

| Cooperation | −3.33*** | (1.03) | −0.99 | (0.67) | −1.01 | (0.63) |

| Land access mode (ref: donations) | ||||||

| Inheritance | −3.05*** | (1.02) | −1.28 | (0.96) | −1.22 | (0.93) |

| Purchased | −3.04* | (1.65) | 0.16 | (1.29) | 0.23 | (1.25) |

| Farmland size | −0.33 | (0.25) | −0.23 | (0.25) | −0.26 | (0.23) |

| Corn yields | 0.00 | (0.00) | −0.00 | (0.00) | −0.00 | (0.00) |

| Livestock | −1.83* | (0.93) | −1.15* | (0.66) | −0.99* | (0.61) |

| Constant | 27.56*** | (5.56) | 20.13*** | (3.60) | ||

| Observations | 308 | 308 | 308 | |||

| F test (p-value) | 26.72*** | 54.52*** | ||||

| Anderson–Rubin Wald test | 5.69* | |||||

| Stock–Wright LM statistic | 14.55** | |||||

| Kleibergen–Paap rk LM statistic | 23.93*** | |||||

| Cragg–Donald Wald F statistic | 54.23 | |||||

| Hansen J statistic | 0.846 | |||||

*, **, *** indicates coefficients are significant at the 10, 5, and 1% levels. Robust clustered standard errors are in parentheses.

Children’s anthropometric estimates

| Variables | HAZ-OLS | HAZ-FE | HAZ-IV-FE | WAZ-OLS | WAZ-FE | WAZ-IV-FE | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. | SE | Coef. | SE | Coef. | SE | Coef. | SE | Coef. | SE | Coef. | SE | |

| Participation | −0.60 | (0.50) | −0.42 | (0.49) | 0.98 | (1.22) | 0.20 | (0.33) | 0.23 | (0.34) | 0.22 | (0.85) |

| Gender of head | −1.00 | (1.01) | −1.64 | (1.02) | −1.33 | (1.06) | −1.96 | (1.16) | −2.03* | (1.03) | −2.06** | (0.98) |

| Age of head | 0.02 | (0.03) | 0.03 | (0.04) | 0.00 | (0.04) | −0.01 | (0.02) | 0.02 | (0.03) | 0.02 | (0.03) |

| Household size | −1.16 | (2.00) | 0.55 | (1.13) | 0.24 | (0.15) | 0.43 | (0.55) | 0.45 | (0.62) | −0.02 | (0.13) |

| Head marital status | 0.15 | (0.14) | 0.21 | (0.16) | 0.95 | (1.55) | 0.17 | (0.14) | −0.02 | (0.14) | 0.42 | (0.64) |

| Age of mother | −0.01 | (0.05) | −0.06 | (0.05) | −0.04 | (0.05) | 0.03 | (0.04) | 0.04 | (0.04) | 0.04 | (0.04) |

| Gender of child | −0.76** | (0.34) | −0.78** | (0.38) | −0.84** | (0.36) | −0.48 | (0.39) | −0.55 | (0.38) | −0.54 | (0.36) |

| Age of child | −0.01 | (0.01) | −0.01 | (0.02) | −0.01 | (0.01) | −0.01 | (0.01) | −0.01 | (0.01) | −0.01 | (0.01) |

| Dependency ratio | −0.06 | (0.14) | 0.02 | (0.17) | 0.02 | (0.16) | 0.04 | (0.14) | 0.17 | (0.14) | 0.16 | (0.13) |

| Head education level achieved (ref: illiterate) | ||||||||||||

| Diploma | 0.12 | (0.97) | 0.03 | (0.88) | 0.23 | (0.84) | 0.34 | (0.59) | 0.45 | (0.68) | −0.45 | (0.62) |

| Secondary | 0.03 | (0.53) | 0.03 | (0.56) | 0.19 | (0.60) | −1.23 | (0.49) | −1.4** | (0.58) | −1.44*** | (0.53) |

| Primary | 0.85 | (0.56) | 0.46 | (0.64) | 0.53 | (0.62) | −0.32 | (0.51) | −0.33 | (0.58) | −0.33 | (0.53) |

| Road status (ref: very poor) | ||||||||||||

| Fair | 1.16 | (0.79) | 1.50 | (0.97) | 1.45* | (0.85) | 0.33 | (0.61) | 0.60 | (0.65) | 0.60 | (0.60) |

| Poor | 0.11 | (0.58) | 0.92 | (0.86) | 0.79 | (0.75) | 0.60 | (0.52) | 0.81 | (0.65) | 0.82 | (0.58) |

| Income management (ref: men) | ||||||||||||

| Women | 0.53 | (0.49) | −0.28 | (0.53) | −0.25 | (0.49) | 0.35 | (0.61) | −0.01 | (0.60) | −0.01 | (0.56) |

| Cooperation | 0.92 | (0.76) | 0.99 | (0.70) | 1.12* | (0.67) | 0.83** | (0.32) | 0.76* | (0.38) | 0.76** | (0.35) |

| Land access mode (ref: donations) | ||||||||||||

| Inheritance | 0.98* | (0.54) | 0.38 | (0.52) | 0.20 | (0.54) | 0.27 | (0.35) | 0.01 | (0.39) | 0.02 | (0.37) |

| Purchased | 1.45 | (0.86) | 0.47 | (0.84) | 0.28 | (0.84) | 1.01** | (0.47) | 1.04 | (0.65) | 1.06* | (0.62) |

| Farmland size | 0.03 | (0.13) | −0.04 | (0.13) | −0.03 | (0.14) | −0.01 | (0.09) | 0.03 | (0.11) | 0.03 | (0.10) |

| Corn yields | −0.00 | (0.00) | −0.00 | (0.00) | 0.00 | (0.00) | 0.00 | (0.00) | 0.00 | (0.00) | 0.00 | (0.00) |

| Livestock | 0.07 | (0.41) | −0.53 | (0.42) | −0.60 | (0.46) | 0.13 | (0.37) | 0.14 | (0.42) | 0.14 | (0.39) |

| Constant | −0.44 | (4.07) | −2.27 | (2.46) | −2.51* | (1.35) | −3.1** | (1.47) | ||||

| Observations | 184 | 184 | 184 | 192 | 192 | 192 | ||||||

| F | 6.09*** | 4.05*** | 15*** | 10.36*** | 3.83*** | 18.37*** | ||||||

| Anderson–Rubin Wald test | 11.57*** | 1.19 | ||||||||||

| Stock–Wright LM S statistic | 6.37 *** | 9.39 *** | ||||||||||

| Kleibergen–Paap rk LM statistic | 9.493*** | 10.749*** | ||||||||||

| Cragg–Donald Wald F statistic | 14.286 | 13.97 | ||||||||||

| Hansen static | 1.171 | 0.708 | ||||||||||

*, **, ***indicates coefficients are significant at the 10, 5, and 1% levels. Robust clustered standard errors are in parentheses. Only second-stage IV estimates are shown.

As mentioned earlier, the validity of our IV model depends on the quality of the instruments. Since our model is over-identified, we tested the exogeneity of the instruments using the Hansen J test and concluded that the instruments are likely exogenous (Tables 7 and 8). Furthermore, employing the Kleibergen–Paap statistic, the Anderson–Rubin Wald, and the Stock–Wright LM statistic, we also assessed the instrumental variables’ weak identification of the model. The results reported at the bottom of Tables 7 and 8 suggest that the instruments identify the model and are jointly statistically significant.

Table 7 shows that participation in artisanal mining significantly reduces household food insecurity, leading to a 2.45-point decrease in food insecurity.

Other socioeconomic and demographic characteristics of households also appear to be important determinants of food insecurity. Education levels (diploma and secondary), and women managing household income appear to play significant effects in reducing household food insecurity. The other control variables like owning livestock and road conditions are linked to better household food security. Households with livestock are less likely to face food insecurity. Moreover, road conditions seem to be a contributing factor to household food security (Table 7).

This study also investigates the relationship between participation in artisanal mining and children’s health z-scores. Participation in artisanal mining showed no significant relationship with HAZ and WAZ.

Moreover, the gender of the child exhibited a negative association with HAZ-IV, while fair road status showed a positive association. The gender of the head and secondary education level displayed negative associations with WAZ-IV. Income cooperation management and the purchased mode of land access were positively linked to WAZ-IV (Table 8).

5 Discussion of findings

Focusing on regionally representative cross-sectional data and employing village-level fixed-effects and IV models, our IV analysis suggests that participation in artisanal diamond mining has a positive effect on household food security in the short run by reducing household food insecurity by 2.45 points (Table 6) but has showed no significant association with children’s nutrition status.

The relationship between food insecurity and participation in diamond artisanal activities aligns with the widely held belief in the literature that involvement in non-farm activities plays a significant role in enhancing food security for rural households. For instance, our study aligns with recent research using regionally representative cross-sectional data, which found that households engaged in non-farm activities had significantly better food security [58,59,60,61,62]. Our results are also consistent with other studies using regional cross-sectional data from Nigeria and panel data from Vietnam, showing that engagement in non-farm activities improves food security and reduces poverty in rural households in these respective countries [57,63,64].

However, our study, unlike previous ones, includes contextual variables such as road conditions, household income management, land access methods, and livestock ownership allowing us to underscore the importance of these contextual factors, which, beyond the mechanic impacts of income from artisanal mining on household food access, can seriously threaten food security in rural areas if not considered. Poor road conditions in landlocked regions, land access modes, and income management by men in a deeply patriarchal society are specific local challenges to achieving food security. Therefore, artisanal diamond income compounded with better context-specific factors can pave the way for stable food security in the rural areas of Kasai Oriental.

On the other hand, our IV regression model reveals that involvement in artisanal mining has no significant effect on children’s anthropometries. However, our result is partially in parallel with the study by Babatunde and Qaim, which found that non-farm income positively affects children HAZ, at 10% but not on WAZ [65]. This might be explained by the fact that cross-sectional data cannot allow us to capture the children’s growth conditions over time. As it is argued in the literature that a child’s nutritional history influences their current well-being, and that optimal child growth depends on continuous monitoring of their health and nutrition from birth [66,67]. Achieving such a condition may be challenging for many rural households, as access to services such as pediatric health and nutrition services, remains limited or poor in many rural areas of Kasai Oriental.

The absence of a significant association between participation in artisanal mining and children’s anthropometries between mining and children’s health conditions calls for panel data analysis that monitors further children’s specific details over time and allows capturing the effect of season on household behaviors; meanwhile, it might raise also questions about unforeseen factors influencing the link between employment in the artisanal mining sector and children’s nutritional conditions.

Unlike the previous study that found a positive association between non-farm activities and children’s health conditions, our study reveals a different outcome [65]. While cash from artisanal diamond mining improves access to food, it does not necessarily enhance nutritional status. This supports the idea that higher non-farm income does not automatically translate into better nutrition for vulnerable households, at least not in the short term [66,68]. Therefore, while participation in artisanal mining contributes to household food security in Kasai Oriental, it may not be enough to improve children’s nutritional status. Much attention must be given to factors such as nutrition literacy, maternal age, and education that may play a substantial role in determining children’s nutrition status by decision-makers.

Besides, socioeconomic characteristics like education levels and women managing household income have a positive effect in reducing household food insecurity. These results are in line with findings from recent research indicating that households led by more educated individuals are more likely to achieve food security [28,48,49].

On the other side, effective income management by women is linked to lower household food insecurity, suggesting that women’s ability to manage income rationally might be a significant strategy in reducing household food insecurity. This result is consistent with Adekunle’s study which argued that women’s bargaining power over income positively affects food security in farm households [69]. The other control variables like owning livestock and road conditions are linked to better household food security. Households with livestock are less likely to face food insecurity. The result aligns with previous studies that highlight livestock as a financial security and food source for rural households especially during shocks [50,70,71,72]. Moreover, road conditions have also a positive effect on reducing household food insecurity (Table 6). This suggests that improved roads boost rural mobility and food circulation. This supports the idea that better roads reduce poverty and thereby, food insecurity by providing access to urban markets [73].

Furthermore, the gender of the child was identified as a factor worsening HAZ-IV, implying that boys are more susceptible to chronic malnutrition than their female counterparts. A fair road status was associated with improved children’s long-term nutrition. The gender of the head and the secondary education level harmed WAZ-IV, suggesting that the migration of male heads and their insufficient knowledge negatively impacted children’s nutrition over time. Income cooperation management and the mode of land access through purchase had a positive impact on WAZ-IV, contributing to the improvement of children’s nutrition over time.

Moreover, factors such as farmland size and corn yields must be the subject of attention for food security and children’s nutrition status in Kasai Oriental. As our summary statistics reveal, there are significant differences in terms of farmland size and corn yields. Non-participants typically hold larger land and achieve higher corn yields than participants. The mean differences for farmland and corn yields are statistically significant at the 10 and 5% levels. This observation may suggest that the intensity of farmland use, soil quality, and labor allocation play crucial roles in determining yields. The low yield of participants might be explained by environmental issues such as soil degradation resulting from mining activities, and reduced rainfall. Additionally, extensive farmland practices due to household members engaging in artisanal diamond activities could contribute to lower yields (Table 5). Considering these issues may contribute to catalyzing agriculture production and contribute to achieving food security in rural areas of Kasai Oriental.

Above all, artisanal diamond mining, while providing immediate economic benefits, also brings significant environmental and social risks that affect not only the mining areas and miners but also surrounding villages and communities since it is closely linked to land damage, dispossession, water pollution, deforestation, soil erosion, and social concerns, which increase the vulnerability of remote rural communities to food insecurity bringing many households down into food insecurity as their access to food becomes limited [20,21]. Additionally, environmental pollution from mining leads to poor health outcomes and reduced agricultural productivity due to weakened working abilities and exposure to violence [74]. The long-term impacts on natural resource sustainability are significant, affecting rural households that rely on these resources and communities beyond the immediate mining areas to the extent that the social fabric of communities can also be disrupted [13,20,39]. The migration of male household members to mining areas often disrupts family structures and social networks, increasing burdens on women and children left behind, which in turn, adversely affects children’s education and overall well-being, as family support systems become strained [55,75]. These factors collectively might impact the socioeconomic stability of rural communities, exacerbating their vulnerability to food insecurity.

These findings rely on cross-sectional data, which limits our ability to observe changes in household behavior over time; such observations would require longitudinal data. Additionally, the households sampled were from rural areas of Kasai oriental where artisanal mining focuses exclusively on diamonds given its unique natural endowment in this mineral. Unlike other minerals that require some quantities for sale, diamonds can be easily marketed by piece.

6 Conclusion and policy implications

This study aimed to analyze the relationship between engagement in artisanal mining activities and household food security, as well as the nutritional status of children under 5 years old in the Kasai Oriental in DRC. To assess the impact of artisanal mining employment, we employed Linear fixed effects and IV fixed effects both at the village level, incorporating HFIAS scores, HAZ, and WAZ.

Indeed, participation in artisanal mining activities has a positive effect on household food security. The results of our model suggest that engagement in these activities likely contributes to reducing the food insecurity of participants by 2.45 points, highlighting the capacity of these activities to generate additional income, enabling households to access more food through markets, beyond what agricultural production alone could provide. However, this engagement did not show a significant association with the nutritional status of children under 5 years old.

Based on these results, it is advisable to consider participation in artisanal diamond mining in any policy aimed at addressing food security and rural poverty in Kasai Oriental.

This involves formalizing the sector as a key rural livelihood and establishing a supportive environment to secure miners’ livelihoods by promoting favorable and secured working conditions that may contribute to extending the socio-economic impact of this sector in the regional economy.

A potential way is for local and regional governments to fund initiatives that identify miners, provide access to production materials, and encourage the formation of cooperatives and associations. As raised in summary statistics (Table 5), illiteracy is still high among those who participate in artisanal mining. This can hinder their access to information on nutrition, socio-environmental issues, empowerment, and self-organization. Government involvement is crucial, especially when there is little interest from third parties in formalizing and organizing the artisanal mining sector in rural Kasai Oriental. Beyond providing legal and technical assistance and funding, government support can enforce sustainable environmental practices, increase local socioeconomic benefits, legitimize miners’ associations, and create a supportive environment for their growth and effectiveness [25,76]. As grassroots organizations, artisanal miner associations can offer targeted support services, boosting incomes and improving working conditions. Studies in Ghana and Tanzania have shown that formalizing and organizing artisanal miners leads to better outcomes by pooling resources, accessing training (nutrition education, financial literacy, environmental practices, and agriculture), and negotiating better prices [76,77]. By doing so, it may be possible to make these activities a viable strategy for rural households to tackle food insecurity and malnutrition in Kasai Oriental.

Besides, artisanal diamond mining activities have shown a negligible effect on improving children’s health conditions within households. Therefore, considering the coexistence of artisanal mining and the agricultural sector, this finding calls for a further enhancement of the agricultural sector’s contribution to the well-being of households in Kasai Oriental. This could involve increasing agricultural productivity and integrating it into a rural development scheme alongside the artisanal diamond mining sector. One approach is to engage communities in ongoing dialogue about land tenure and decision-making processes related to mining projects. This collaboration can establish clear land-use boundaries, ensuring mutual benefits for all stakeholders by addressing agricultural, social, and environmental concerns. Furthermore, miners should be trained in sustainable practices, including water usage, land use, and restoration techniques. Combined with regular, holistic monitoring of the impacts of multiple mining operations, this collaboration can help minimize land damage and ensure the sustainable integration of both sectors [7,26,74,75,76,77,78,79,80]. By aligning household needs with respective sectoral yields in combating food insecurity, it might be possible to improve the nutritional status of children.

However, this study has several limitations that need to be considered. The data for this research were collected in a snapshot, which does not account for the dynamic nature of rural livelihoods. This study focuses only on capturing the role of artisanal diamond mining in improving food security and children’s nutritional status in rural households in Kasai Oriental. However, it does not study in-depth the drivers of participation in artisanal mining, such as shocks that are often push factors for artisanal diamond mining or the nebulous organization and supply chain of the diamond sector in Kasai oriental. Nor does it address the country controversial social such as child labor, gender bias, and environmental issues associated with artisanal mining. Future research should address these limitations to better weigh the potential socioeconomic benefits of artisanal mining against its socio-environmental costs.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to my Sensei for their advice and patience in guiding me, to the two anonymous reviewers for their useful comments and insights, and to the JICA SDGs Global Leaders Program.

-

Funding information: Authors state no funding is involved.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and consented to its submission to the journal, reviewed all the results and approved the final version of the manuscript. HNK: conceptualization: developed the research idea and framework. Methodology: designed the research methods and experimental procedures. Software: created and maintained the software used for data analysis. Data collection: collected and organized the raw data. Curation and analysis: processed and analyzed the data. Writing: drafted the initial manuscript. Reviewing and editing: reviewed and revised the manuscript for intellectual content. MK: supervision and guidance: provided oversight and strategic guidance throughout the research process. Validation: verified the accuracy and validity of the manuscript content and revisions. AC: supervision and guidance: offered continuous support and expert advice during the research. Validation: ensured the integrity and correctness of the manuscript and its revisions.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Ethical approval: The standard survey protocols, questionnaires, and anthropometric procedures related to children under 5 years old were reviewed and approved by the Medical Research Ethics Committee at the University of Mbuji Mayi in the Democratic Republic of Congo. The trial was officially registered under the reference number N/Ref:01/MREC/UM/NKL/2022 on September 14th, 2022.

-

Informed consent: Informed consent has been obtained from all household representatives.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Appendix

Alpha Cronbach test statistics

| Average interitem covariance | 0.7949246 | |||

| Cronbach’s alpha coefficient | 0.937846716 | |||

| Number of items | 9 | |||

| Observations | 308 | |||

| Item | Item test correlation | Item rest correlation | Average interitem correlation | Alpha |

| Worried about not enough food | 0.6648 | 0.577574548 | 0.666495269 | 0.94113376 |

| Unable to eat preferred food | 0.7916 | 0.731396294 | 0.633118847 | 0.932457197 |

| Ate just a few kinds of food | 0.8131 | 0.758024462 | 0.627499375 | 0.930922406 |

| Ate unwanted foods | 0.8625 | 0.820412749 | 0.61449505 | 0.927283322 |

| Ate a smaller than desired at a meal | 0.8497 | 0.804140316 | 0.617846784 | 0.92823316 |

| Ate fewer meals in a day than desired | 0.8194 | 0.765840308 | 0.625678125 | 0.93042017 |

| Had no food of any kind | 0.8566 | 0.813034195 | 0.616122918 | 0.927745687 |

| Went to sleep at night hungry | 0.8283 | 0.777344198 | 0.623406308 | 0.929790337 |

| Went without food over a day and night | 0.8677 | 0.82723049 | 0.612858092 | 0.926816366 |

| Test scale | 0.6264 | 0.9378 |

References

[1] World Bank. State of the artisanal and small-scale mining sector. Washington, DC: World Bank; 2019.Suche in Google Scholar

[2] African Mining Vision AMV. Building a sustainable future for Africa’s extractive industry: From vision to action. Addis Ababa: African Union, African Development Bank and UNECA; 2011.Suche in Google Scholar

[3] Hilson G, Hilson A, Maconachie R, McQuilken J, Goumandakoye H. Artisanal and small-scale mining (ASM) in sub-Saharan Africa: Re-conceptualizing formalization and “illegal” activity. Geoforum. Jul. 2017;83:80–90. 10.1016/j.geoforum.2017.05.004.Suche in Google Scholar

[4] Hilson G, Maconachie R. Formalising artisanal and small-scale mining: insights, contestations and clarifications. Area. 2017;49(4):443–51. 10.1111/area.12328.Suche in Google Scholar

[5] Justice IM-S, Ahenkan A, Bawole JN, Yeboah-Assiamah E. Rural poverty and artisanal mining in sub-saharan africa: new perspective through environment–poverty paradox. Int J Rural Manag. Oct 2017;13(2):162–81. 10.1177/0973005217730274.Suche in Google Scholar

[6] United Nations Economic Commission for Africa UNECA. Minerals and Africa’s Development Report New York: UNECA; 2011.Suche in Google Scholar

[7] Chupezi TJ, Ingram V, Schure J. Impacts of artisanal gold and diamond mining on livelihoods and the environment in the Sangha Tri-National Park landscape. Indonesia: Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR); 2009. 10.17528/cifor/003029.Suche in Google Scholar

[8] Tshimanga M. Rôle de l’artisanat minier du diamant dans l’organisation régionale. Cas de Mbujimayi et ses environs au Kasaï Oriental Lubumbashi. DR Congo: Université de Lubumbashi; 2009.Suche in Google Scholar

[9] Tshonda JO. Un nœud gordien dans l’espace congolais. Tervuren, Belgique: Musée Royal de l’Afrique Centrale; 2014.Suche in Google Scholar

[10] Banque Mondiale. République démocratique du Congo RDC Évaluation de la pauvreté. Washington, DC. USA: Banque Mondiale; 2016. Rapport no: ACS19045.Suche in Google Scholar

[11] Hilson G, McQuilken J. Four decades of support for artisanal and small-scale mining in sub-Saharan Africa: A critical review. Extr Ind Soc. Mar 2014;1(1):104–18. 10.1016/j.exis.2014.01.002.Suche in Google Scholar

[12] Okoh G, Hilson G. Poverty and Livelihood Diversification: Exploring the Linkages Between Smallholder Farming and Artisanal Mining in Rural Ghana. J Int Dev. 2011;23(8):1100–14. 10.1002/jid.1834.Suche in Google Scholar

[13] PACT, PROMINES Study Artisanal Mining in the Democratic Republic of Congo, 2010.Suche in Google Scholar

[14] Hund K, Carole M. Dynamiques de déforestation dans le bassin du Congo Réconcilier la croissance économique et la protection de la forêt. Washington, DC: World Bank; 2013.Suche in Google Scholar

[15] Kouadio AC, Kouassi K, Assi-Kaudjhis JP. Orpaillage, disponibilité alimentaire et compétition foncière dans les zones aurifères du département de Bouaflé. Tropicultura. 2018;36(2):369–79Suche in Google Scholar

[16] PNUD, Profil de pauvreté de la province du Kasai Oriental. Kinshasa. RD Congo., Kinshasa. RD Congo, 2009.Suche in Google Scholar

[17] Hilson G, Maconachie R. Entrepreneurship and innovation in Africa’s artisanal and small-scale mining sector: Developments and trajectories. J Rural Stud. Aug. 2020;78:149–62. 10.1016/j.jrurstud.2020.06.004.Suche in Google Scholar

[18] Ofosu G, Dittmann A, Sarpong D, Botchie D. Socio-economic and environmental implications of Artisanal and Small-scale Mining (ASM) on agriculture and livelihoods. Environ Sci Policy. Apr. 2020;106:210–20. 10.1016/j.envsci.2020.02.005.Suche in Google Scholar

[19] Mwitwa J, German L, Muimba-Kankolongo A, Puntodewo A. Governance and sustainability challenges in landscapes shaped by mining: Mining-forestry linkages and impacts in the Copper Belt of Zambia and the DR Congo. For Policy Econ. Dec. 2012;25:19–30. 10.1016/j.forpol.2012.08.001.Suche in Google Scholar

[20] Galli N, Chiarelli DD, D’Angelo M, Rulli MC. Socio-environmental impacts of diamond mining areas in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Sci Total Environ. Mar. 2022;810:152037. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.152037.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[21] Otamonga J-P, Poté JW. Abandoned mines and artisanal and small-scale mining in Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC): Survey and agenda for future research. J Geochem Explor. Jan. 2020;208:106394. 10.1016/j.gexplo.2019.106394.Suche in Google Scholar

[22] Pokorny B, von Lübke C, Dayamba SD, Dickow H. All the gold for nothing? Impacts of mining on rural livelihoods in Northern Burkina Faso. World Dev. Jul. 2019;119:23–39. 10.1016/j.worlddev.2019.03.003.Suche in Google Scholar

[23] Hilson G, Garforth C. “Agricultural Poverty” and the expansion of artisanal mining in sub-saharan africa: experiences from Southwest Mali and Southeast Ghana. Popul Res Policy Rev. Jun. 2012;31(3):435–64. 10.1007/s11113-012-9229-6.Suche in Google Scholar

[24] Hentschel T, Hruschka F, Priester M. Artisanal and small-scale mining: challenges and opportunities. London: IIED: WBCSD; 2003.Suche in Google Scholar

[25] Wegenast T, Beck J. Mining, rural livelihoods and food security: A disaggregated analysis of sub-Saharan Africa. World Dev. Jun. 2020;130:104921. 10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.104921.Suche in Google Scholar

[26] Schwartz FW, Lee S, Darrah TH. A review of the scope of artisanal and small‐scale mining worldwide, poverty, and the associated health impacts. GeoHealth. Jan. 2021;5(1):1–15. 10.1029/2020GH000325.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[27] Buxton A, Responding to the challenge of artisanal and small-scale mining How can knowledge networks help?, IED 2013, 2013, [Online]. Available: http://pubs.iied.org/16532IIED.html.Suche in Google Scholar

[28] Murphy E, Glaeser L, Maalouf-Manasseh Z, Collison DK. USAID Office of Food for Peace Food Security Desk Review for Kasai Occidental and Kasai Oriental. Democratic Republic of Congo., Washington, DC: FHI 360/FANTA; 2015.Suche in Google Scholar

[29] DFID. Sustainable livelihoods guidance sheets. UK, London: DFID; 1999. 10.1002/smj.Suche in Google Scholar

[30] Ashagrie E. A theoretical and analytical framework to the inquiry of sustainable land management practices. Int J Bus Econ Dev. 2021;9(2):1–15.10.24052/IJBED/V09N02/ART-03Suche in Google Scholar