Abstract

We are presenting a first overview of the ceramic annulets found in Neolithic contexts in the Balkan Peninsula, which we are interpreting as bracelets with a very specific short-term use and function. Based on available information, we are revealing their geographical and chronological distribution. The ceramic bracelets appeared within the first farming communities of the Central Balkans at the break from seventh to sixth millennium BC. They are not abundant, always fragmented and found in residential contexts at Neolithic sites north of the Aegean between 6000 and 5400 BC. The assemblages from the two Neolithic sites Amzabegovo and Svinjarička Čuka, both on the Vardar-Morava neolithization route into Europe, are presented here as case studies. Based on our data, we reveal their physical properties and their place in the ceramic production, their diversity and evolution, as well as their possible function and relation to social aspects as part of the Neolithization process.

1 Introduction

We have recently initiated the first systematic comparative study of early Neolithic sites along the Vardar-Morava dispersal route, which offers the opportunity to analyse newly excavated, dated and contextualized materials, based on the case studies of Amzabegovo and Svinjarička Čuka. The rich material assemblages of both sites also included some inconspicuous small ceramic fragments of objects identified as fragmented clay annulets, which, based on the analyses presented here, we interpret as bracelets. Until now the ceramic bracelets have not been sufficiently studied and are not well known as a distinct object category of the Neolithic in southeast Europe. Usually fragmented and deposited in domestic contexts, these specific ornaments remained neglected, underestimated or simply overlooked due to their commonly bad preservation and relatively low numbers per site. The ceramic bracelets of the Neolithic appear for the first time in the Central Balkan, and persist for a certain length of time. Seen in a broader geographic and temporal perspective, this represents one step of the neolithization process between Anatolia and Europe. The meaning behind the specificity of the Central Balkan Neolithic is a question of more complex and comprehensive study, to which more detailed study of the bracelets, as one of the markers, has the potential to contribute. Their distinct chronological appearance with the first farming communities in the early Neolithic and limited spatial distribution in southeast Europe give relevance to the bracelets in the context of studying the Neolithization process.

It is widely accepted that the main actors in the Neolithization process were migrating farmers moving in a general W-NW direction, starting from the Neolithic core area of Anatolia and the Levant (Hofmanová et al., 2016; Mathieson et al., 2018). The Neolithic techno-economic complex reached the Aegean coast of the Balkan Peninsula by the mid-seventh millennium BC. The Central Balkan hinterland was a key region, where the Neolithic communities went through essential transformations and adaptations, necessary for bridging the gap between the warm Mediterranean and the colder and humid Continental parts of Central Europe, enabling further expansion to the rest of the continent (Krauß et al., 2018). The transformative process took almost five centuries, roughly between 6500 and 6000 BC, and our main focus is to identify the discrete mechanisms and the dynamics of the Neolithic spread between the Aegean and the Danube. We believe a more high-resolution (micro-)regional approach is needed, in order to build an overarching narrative. The Vardar and Morava River valleys constitute one of the main corridors, facilitating the movement of people, goods and ideas, and is well represented by the Amzabegovo and Svinjarička Čuka sites we are investigating.

Our study of the new and well-contextualized distinct clay objects found at these sites raises the question of their function on individual and communal levels, their relation with older comparable ornaments made of stone in other areas as well as their potential as source of new information about the Neolithization process in the Balkans.

2 Ceramic Annulets

The idea of annulets as ornaments is embedded in the much older concept of stone, bone and shell body augmentation of southwest Asia and Europe, which can be traced back at least to the Upper Palaeolithic (Baker et al., 2024; Baysal, 2019; Perlès, 2018, 2021; White, 1993). Stone annulets and bracelets as individual ornaments are a common practice in Pre-Pottery Neolithic (PPN A) Anatolia and the Levant from 9500 BCE onwards, where they are strongly linked with the early stages of craft specialization (Gebel, 2023; Kozlowski & Aurenche, 2005). They are characterized by a high-quality production of diverse stone raw materials in distinct shape-types and a wide-spreading shared practice of use, repairing and re-using (Baysal, 2019, pp. 116–120), including potential deliberate fragmentation (Erim-Özdoğan, 2011). The practice of manufacturing stone bracelets is spreading further from east to west and is closely associated with the establishment of first Neolithic communities in west Anatolia and the wider Mediterranean (Çilingiroğlu, 2005; Martínez-Sevilla et al., 2021). Their common use as bracelets is evident due to their body position in burials, use-wear analyses and their standardized clusters of sizes (Martínez-Sevilla et al., 2021).

The innovation of using clay for the production of containers in the Pottery Neolithic period around 7000 BCE did not change the practice of stone bracelet production in southwest Asia. During the seventh millennium BCE, stone bracelets were distributed as far as the Aegean coast of Anatolia, as evidenced at Çukuriçi Höyük (Horejs et al., 2015), but did not reach the Greek mainland until the middle and late Neolithic times (Ifantidis, 2019, 2020). However, clay bracelets are not known in Anatolia or in the Aegean, where clay as material, aside few exceptions, plays a minor role in ornament production in general. These exceptions include the few clay beads found in level VIII at Çukuriçi Höyük (6200–6000 BC), as well as those reported from Çatal Höyük (Bains et al., 2013; Baysal, 2019, p. 127). In both cases, they are only a small part of the ornamentation repertoire, overwhelmingly populated by stone and shell objects. Ornamental ceramic objects are also very rare at Neolithic sites in Greece, related to few specific types (Ifantidis, 2019).

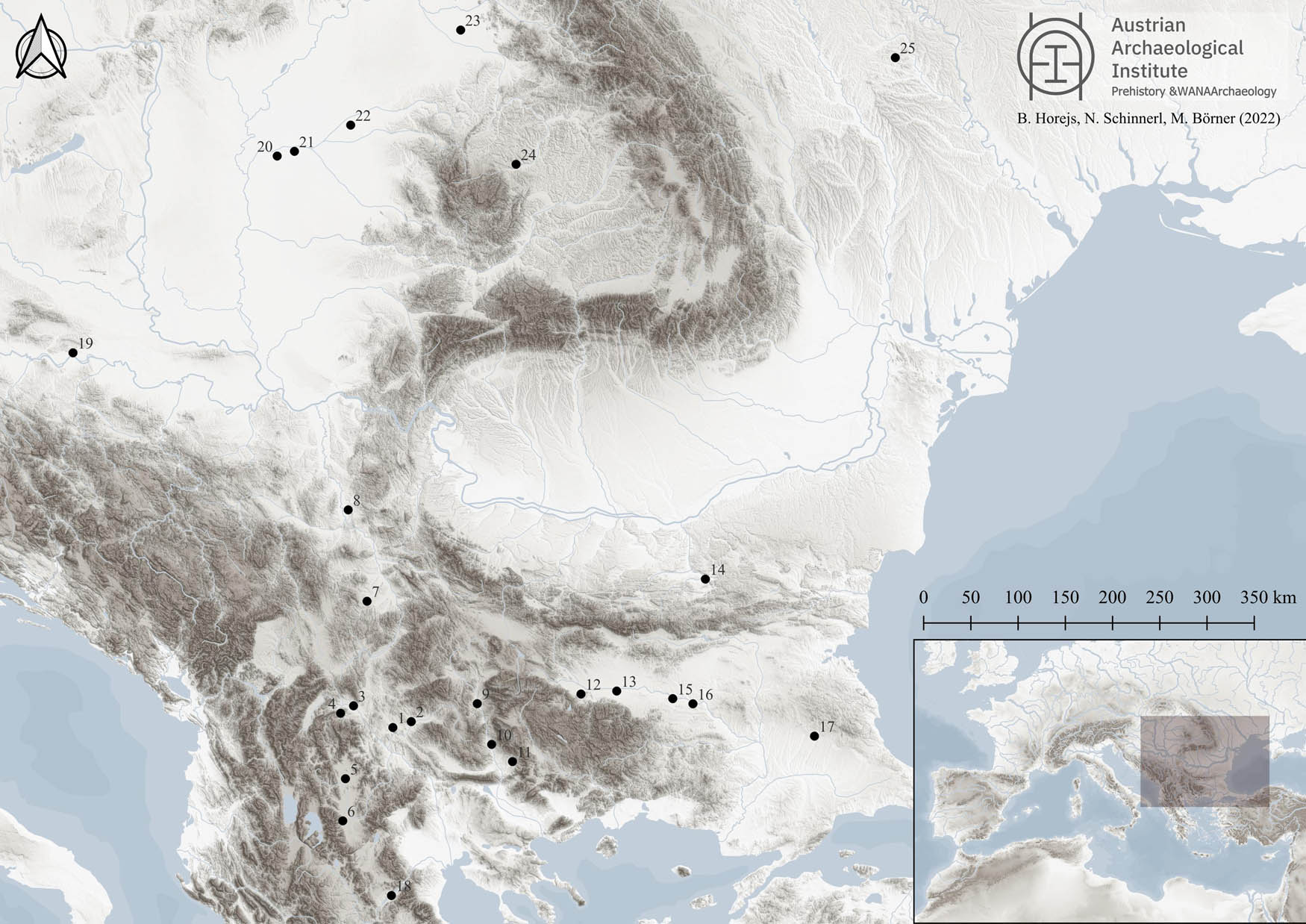

Further up north from the Aegean coast, however, the picture changes significantly. The ceramic annulets appear for the first time around 6000 BC in the south-central Balkans, and can be found at numerous sites spread throughout the central Balkan region and further to the north following the Neolithic dispersal (Figure 1). The most detailed studies come from the fringes of the dispersal area, such as Aşağı Pınar in Türkiye (Aytek, 2015), Sacarovca I in Moldova (Dergachev & Larina, 2015), and the Körös Valley from Hungary (as part of the figurine study of Starnini (2014)). From the central part of the distribution area (i.e. the south-central Balkans) the annulets are rarely published in detail. Gimbutas described nine ceramic bracelets in an edited monograph on Amzabegovo (Gimbutas, 1976, p. 250). Similar objects are reported from several other sites (Detev, 1959; Dimitrijević et al., 2021; Elenski, 2006; Kalicz, 2011; Lazarovici & Maxim, 1995; Lichardus-Itten et al., 2002; Minichreiter, 2007; Mould et al., 2000; Perić, 2008; Stojanovski, 2017; Vasileva & Hadzipetkov, 2014). A regional overview has not been presented yet, but their distribution in southeast Europe suggests a potential importance as transcultural material expression related to the Neolithization, comparable to the southwest Asia and the Mediterranean with their stone counterparts. The current gaps in their spatial dissemination are very likely related to the state of publications and identification (Figure 1).

Map with location of sites where ceramic annulets were reported: 1. Amzabegovo (Gimbutas, 1976; this study), 2. Grnčarica (Stojanovski, 2017), 3. Tumba Madžari (Kanzurova, personal communication), 4. Cerje Govrlevo (Dimitrijević et al., 2021), 5. Vrbjanska Čuka (Naumov, personal communication), 6. Veluška Tumba (Naumov, personal communication), 7. Svinjarička Čuka (this study), 8. Drenovac (Perić, 2008), 9. Bulgarchevo (Grebska-Kulow personal communication), 10. Ilindentsi (Grebska-Kulow personal communication), 11. Kovachevo (Lichardus-Itten et al., 2002), 12. Yasa Tepe-Plovdiv (Detev, 1959), 13. Kapitan Dimitrievo (Detev, 1950), 14. Dzhulyunitsa-Smardesh (Elenski, 2006), 15. Yabalkovo (Vasileva & Hadzipetkov, 2014), 16. Nova Nadezhda (Bacvarov and Nikolova, personal communication), 17. Aşağı Pınar (Aytek, 2015), 18. Servia (Mould et al., 2000), 19. Galovo (Minichreiter, 2007), 20. Szarvas (Starnini, 2014), 21. Endröd (Starnini, 2014), 22. Furta-Csátó (Starnini, 2014), 23. Mehtelek (Kalicz, 2011), 24. Gura Baciului (Lazarovici & Maxim, 1995), 25. Sacarovca I (Dergachev & Larina, 2015) (©B. Horejs, N. Schinnerl, M. Börner (2022), modified by D. Stojanovski).

3 Ceramic Bracelets of Amzabegovo and Svinjarička Čuka

Amzabegovo is a well-known Neolithic site in the Vardar River system in Macedonia and has served as a reference point in Balkan Neolithic studies since the early 1970s (Garašanin et al., 2009; Garašanin, 1979, 1982, 1998; Gimbutas, 1974, 1976). New excavations are ongoing since 2019 and this is the first presentation of material coming from the latest campaigns. Svinjarička Čuka is a newly discovered site in the South Morava system of South Serbia. The intensive multidisciplinary research at this site since 2018, by the Austrian Archaeological Institute and local and national Serbian partners, has illuminated the beginning of settled life in the Leskovac basin, a previously not well-known microregion of the Vardar-Morava Neolithization corridor (Horejs et al., 2019, 2022).

This study is focusing on the ceramic annulets coming from the latest excavations at these two sites, which are systematically studied in a comparative approach by the authors since 2023. Both sites are settlements located along the Vardar-Morava River corridor and provide substantial data deriving from state-of-the-art fieldwork and cover not only the initial phases of the Neolithic in their area, but also the subsequent centuries. Their location on opposite parts of the environmental frontier between Mediterranean climate and vegetation zone in the south (Amzabegovo) and continental climate and landscapes in the north (Svinjarička Čuka) offer an ideal framework for cross-cultural-environmental studies within a regional nutshell. Their distance of around 200 km also represents a farming frontier zone for a few centuries, before its further dispersal into the continent along this corridor based on radiocarbon data (Porčić, 2024; Whittle et al., 2002). Amzabegovo starts around 6400/6300 BC and is the eponym site of the Amzabegovo-Vršnik group (Ballmer et al., submitted; Pavúk & Bakamska, 2021), while S. Čuka starts later at 6100/6000 cal BC and is attributed to the Starčevo group (Horejs et al., 2025).

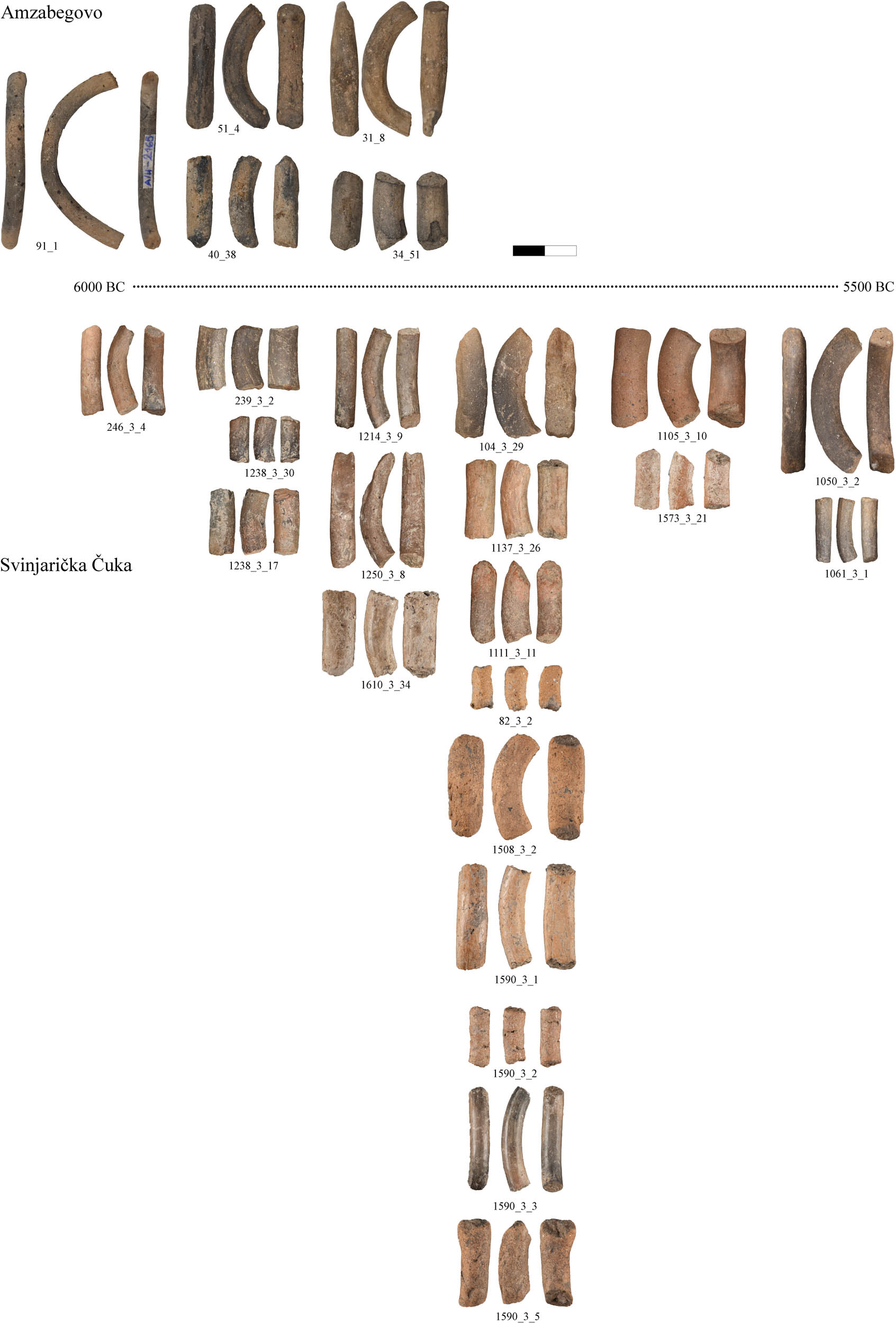

Twenty clay bracelets from Svinjarička Čuka and five from Amzabegovo are included in this study (Figure 2, Table 1). They are all coming from non-funerary contexts (stratified, contextualized and radiocarbon-dated), and are old-broken pieces without signs of reuse, presumably partially re-deposited. By comparing them with similar objects from the wider Balkan area, we are presenting them in the context of the Neolithic development in the Central Balkans.

The ceramic annulets assemblage included in this study, in a chronological perspective (© D. Stojanovski and F. Ostmann, ÖAI).

Amzabegovo and Svinjarička Čuka ceramic bracelet assemblage

| Item ID | Context | Age range (cal BC) | Type | Diameter (mm) | Thickness/width (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMZ_31_8 | Dry brick wall debris | 5750–5600 | I | 40 | 8/8.5 |

| AMZ_34_51 | Clay layer | 5750–5600 | I | 40 | 9.3/9.3 |

| AMZ_51_4 | Floor foundation | 6000–5800 | I | 40 | 8/8 |

| AMZ_40_38 | Levelling layer | 6000–5800 | I | 80 | 7.7/7.7 |

| AMZ_91_1 | Pit next to oven | 6028–5888 | I | 45 | 5.5/5.5 |

| CU19_1050_3_2 | Clay layer | Around 5500 | IV | 42 | 10/7 |

| CU21_1061_3_1 | Activity horizon | Around 5500 | I | 48 | 5/5 |

| CU24_1573_3_21 | Clay layer | 5600–5500 | I | 70 | 7.5/7.5 |

| CU21_1105_3_10 | Clay layer | 5600–5500 | I | 36 | 11/11 |

| CU21_1111_3_11 | Clay layer | Around 5600 | I | 74 | 9/8 |

| CU22_1137_3_26 | Activity horizon | Around 5600 | II | 50 | 9/9 |

| CU21_0104_3_29 | Find accumulation | Around 5600 | V | 50 | 11/10 |

| CU24_1508_3_2 | Filling layer | Around 5600 | II | 38 | 10/11 |

| CU24_1590_3_1 | Complex 3 – activity horizon | Around 5600 | II | 70 | 8/11 |

| CU24_1590_3_2 | Complex 3 – activity horizon | Around 5600 | I | 80 | 6/6 |

| CU24_1590_3_3 | Complex 3 – activity horizon | Around 5600 | I | 64 | 6/6 |

| CU24_1590_3_5 | Complex 3 – activity horizon | Around 5600 | I | 50 | 10/9 |

| CU23_0082_3_2 | Complex 4 – Starčevo house | Around 5600 | VI | 40 | 7/7 |

| CU22_1214_3_9 | Clay layer | 5700–5600 | I | 56 | 7/7 |

| CU22_1250_3_8 | Clay layer | 5700–5600 | I | 40 | 8/8 |

| CU24_1610_3_34 | activity horizon with Complex 8 | 5700–5600 | I | 50 | 10/10 |

| CU22_1238_3_17 | Clay layer | 5900–5700 | I | 50 | 9/8 |

| CU23_1238_3_30 | Clay layer | 5900–5700 | I | 44 | 6/6 |

| CU22_0239_3_2 | Activity horizon | 5900–5700 | III | 40 | 8/9 |

| CU22_0246 _3_4 | Clay layer | c. 6000 | I | 50 | 6/6 |

The age range is determined from absolute dates, obtained from samples coming from the same, or closely related units as the bracelets.

3.1 Techno-Typology

The annulets are part of the established ceramic production at each of the sites. Macroscopically, they are identified with some of the ware groups already recognized from the pottery (Burke, 2022; Horejs et al., 2022). No recipe preferences could be noticed – fine micaceous fabrics were used at the same time with fabrics containing large mineral inclusions, as well as a blend tempered with organic material (Figure 3a). There was no single approach to surface treatment either. Most of the pieces are evenly and well burnished. Some show different levels of polish. In one example specifically, there is a clear difference between the highly polished interior and the dull exterior (Figure 3b). This is highly likely a use-wear consequence, rather than a technological trait. In contrast, there are roughly formed examples such as SČ_104_3_29, where folds and striations are visible, and on which an imprint of some sort of cloth is visible on its surface (Figure 3c). The colour after firing, like in the pottery, varies from lighter red and brown hues to dark grey.

Selected bracelets representing technological features: (a) Two different clay fabrics, (b) bracelet with different surface treatments of the exterior and the interior and (c) a sample with rough surface and fabric imprint (photos: F. Ostmann, ÖAI).

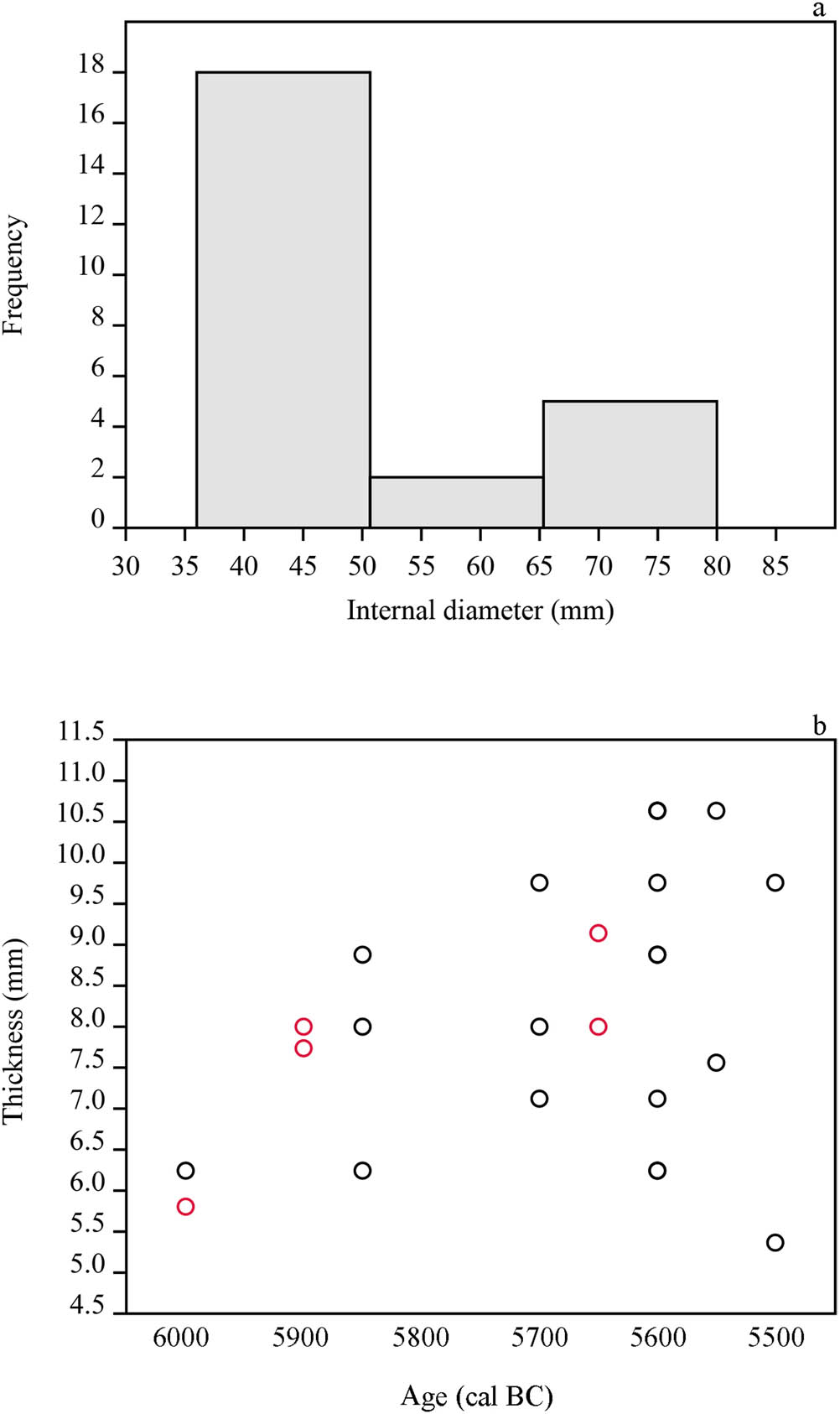

Regarding the size of the bracelets, 18 of the 25 items (72%) fall into the small category, with internal diameter between 36 and 50 mm (Figure 4a). Two are intermediate, with diameter between 50 and 65 mm, and five are large (65–80 mm). The width and thickness of the bracelet body range between 5.5 and 11 mm. Even though we are dealing with a small assemblage, as far as the width and thickness is concerned, there is a clear pattern of size increase through time (Figure 4b). The older examples are thinner with more symmetrical body (i.e. the width and the thickness are the same). The younger show a tendency towards width and thickness increase and often there is a difference between the two parameters, resulting in diversification of the cross section.

(a) Graph showing the frequency of small, medium and large diameter bracelets within our assemblage and (b) graph showing the increase in thickness of the annulets through time. The Svinjarička Čuka examples are in black and Amzabegovo in red.

The cross sections of the individual pieces are used here to classify the annulets of the two sites into six types: type I – the cross section is circle, making the body of the object cylindrical; type II – dome cross section, the annulet is flattened on the internal side; type III – inverted dome cross section, the outer surface of the annulet is flattened; type IV – vertical ellipse cross section, resulting in taller and slimmer annulets; type V – trapeze cross section, the internal surface of the annulet is flat and wider than the outer, which is also flat; we have only one example, in which the sides are slightly concave; type VI – triangular cross section. Only type I annulets are found at Amzabegovo, which is also the dominant type at Svinjarička Čuka. The other types are represented only at Svinjarička Čuka by one sample each, except for type II, which is represented by three examples. It seems that the shapes diversify with time, type I being the earliest prototype, but a bigger assemblage is needed to establish the cross section as a chronological marker.

3.2 Spatial Framing

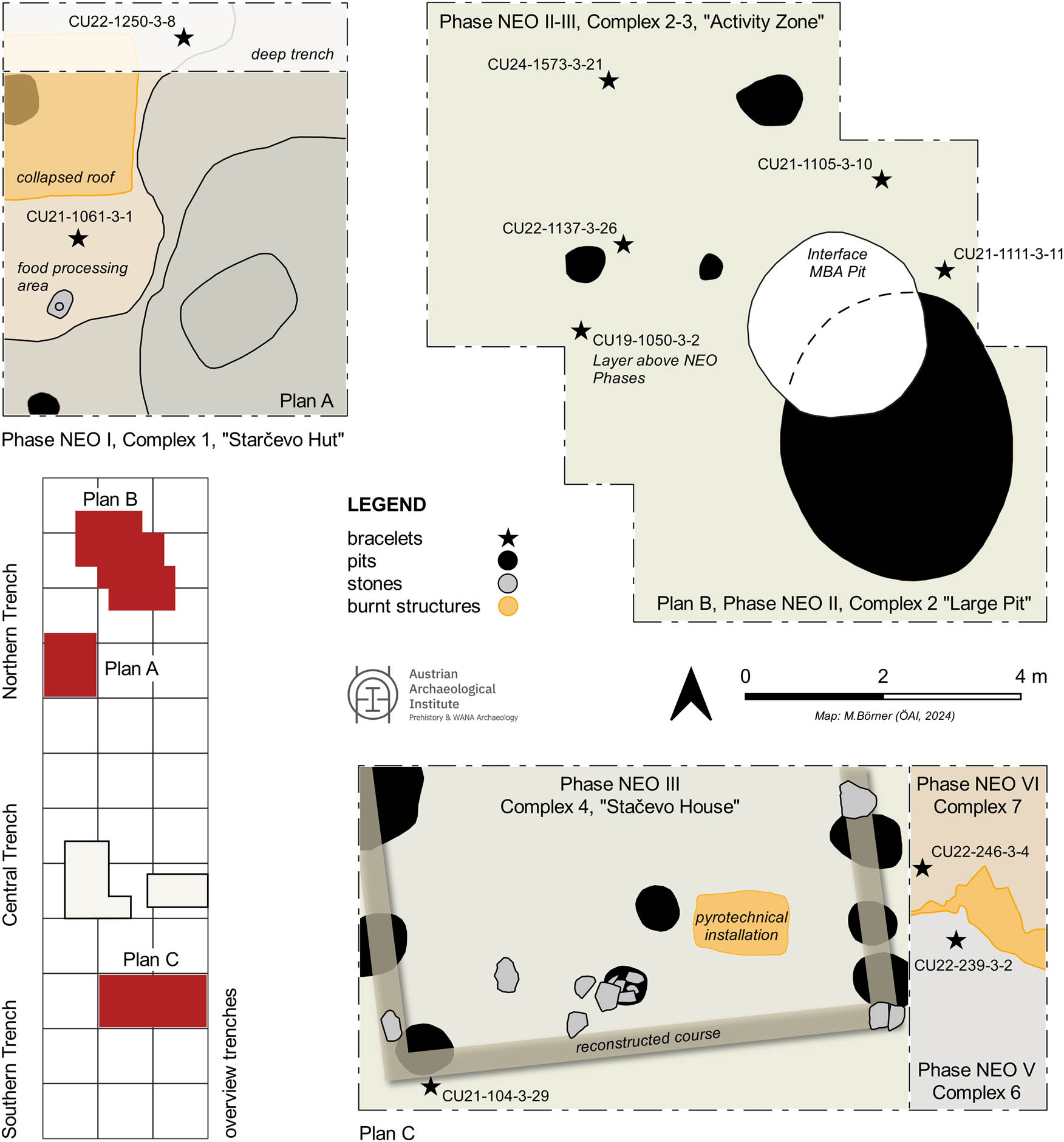

Most of the bracelets were re-deposited and found in filling or levelling layers, although several were discovered in concrete domestic units (a pit, a floor or an activity area) (Figure 5 and Table 1). With the well-established chrono-stratigraphic structure at both sites, the occurrence of the annulets can be precisely dated. The earliest annulet from Amzabegovo (91_1, Figure 2) was found in phase 3 of the revised stratigraphy, in a shallow pit next to an oven dated around 6000 BC (Ballmer et al., submitted). Item 51_4 was found in phase 4 in a thin fundament layer under a subfloor of wooden planks, dated one century later. The rest were found in reworked house rubble layers (levelling events) of phase 5 up until 5600 BC. No annulets were found in the overlying layers in trench 1 at Amzabegovo, neither in those older than 6000 BC.

The excavation area at Svinjarička Čuka, with plans of units and phases associated with ceramic bracelets (©M. Börner, ÖAI).

The oldest ceramic annulet from Svinjarička Čuka (246_3_4, Figures 2 and 5) comes from a clay layer, which is part of a burned daub structure in the southern trench (Complex 7), dated again around 6000 BC. Item 239_3_2 comes from the overlying Complex 6 – an activity horizon associated with pits. These two annulets belong to phases NEO 6 and 5, respectively, which represent the establishment and the early developments in the southern part of the settlement (Horejs et al., 2025). Two other annulet fragments from phase NEO 5 were found in the northern trench (1238_3_17 and 1238_3_30). Three annulets were found in layers from the NEO 4 phase (1610_3_34, 1214_3_9 and 1250_3_8). Dated units from this phase are currently lacking, but it is later than 5700 BC, and earlier than the NEO 3 phase. NEO 3 is represented by Complex 3 and Complex 4 – “the Starčevo House” – securely dated around 5600 BC (Horejs et al., 2022). Nine bracelets were found in these two complexes, or units related to them (Figures 2 and 5). NEO 2 phase closely follows NEO 3. It is represented by Complex 2, from where an annulet fragment was also retrieved (1105_3_10, Figures 2 and 5). Another one (1573_3_21) from the same phase comes from a clay layer west of Complex 2. The youngest example 1061_3_1 was found in Complex 1 (“the Starčevo Hut”) of the NEO 1 phase, dated around 5500 BC, and another one (1050_3_2) in the overlying layer marking the end of the Neolithic sequence at Svinjarička Čuka (Horejs et al., 2019, 2022).

4 Discussion

The ceramic annulets are a Balkan Neolithic phenomenon. They appear in a restricted central region of the peninsula, with Veluška Tumba, Kovachevo and Aşağı Pınar being the southernmost manifestations (Figure 1). The only case south of this line is the site of Servia on the Haliacmon River in the Greek interior, where two bracelets were found, but they are not well contextualized, with problematic absolute dates, and vaguely attributed to the Greek Middle Neolithic (Mould et al., 2000). They were probably a late introduction from the north. Relying on the current data, the highest density of sites with ceramic bracelets appears to be along the river valleys of the South-Central Balkans, such as Vardar, Morava, Struma and Maritsa (Figure 1). The earliest ceramic bracelets come from this group, including Amzabegovo and Svinjarička Čuka, appearing for the first time around 6000 BC. So far, no earlier examples are known, despite that some of the sites, like Amzabegovo, contain earlier strata. In Central and Eastern Europe, ceramic bracelets were found at sites in Hungary, Romania and Moldova with the majority evident in the Carpathian basin. Here they are part of the assemblage since the sites were established and can be associated with the beginning of the Neolithic. After they first appeared in the Central Balkans, they became part of the material culture and were involved in the post-6000 BC neolithization process. After a detailed review of published materials from Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina, we concluded that no ceramic annulets were reported from the western Balkans mountainous region or along the Adriatic coast. Such items were also not reported from Greece and Turkey (apart from Aşağı Pınar, which is part of the Balkan interior, and Servia). Data are missing from many regions and the annulets are not always reported. For a more accurate and detailed dispersal pattern, a more thorough study is needed, which should fill in the gap along the Danube in the northern Balkans and the southern Carpathians. Nevertheless, we believe the map in Figure 1 reflects the general outline of the dispersal area of the ceramic bracelets during the first half of the sixth millennium BC.

Throughout the dispersal area, the bracelets share a common form – a ring-shaped ceramic body with reddish-brown and grey hues. Regarding the Amzabegovo and Svinjarička Čuka assemblages, we have established that there is no specific unified recipe. The same fabrics used for pottery were also used for the annulets. There is no unique approach to surface finishing also. In general, they are well smoothed, some polished, but often there are visible traces from the forming process, such as folds, wrinkles, smoothing tracks, and one bares imprints of fine cloth on one side (Figure 3c). However, the makers had paid attention to the outline of the body of the annulets, and based on the cross section, our assemblage is grouped into six categories (see above). About 72% (18 out of the 25) belong to type I, with regular cylindrical body and round cross section. All the other types are represented by one or very few examples. The assemblage is not too big, but we have noticed a relevant trend in evolution of the annulets, from thinner bodies in the earlier phases, towards thicker and wider bodies in the mid-sixth millennium.

Due to their shape, the ceramic annulets are usually interpreted as bracelets. This is assumed from their visual appearance and the analogies with comparable stone objects in early Neolithic southwest Asia and the Mediterranean. One example from Svinjarička Čuka gives some support in this direction. Item 1105_3_10 has significantly burnished internal side, as opposed to the dull exterior (Figure 3b). The burnish is not equally distributed and, in both macro- and microscopic observation, resembles a use wear from a frequent and continuous striation against a soft surface (such as skin), which indicates it was worn as bracelet. Experimental studies on pottery and bone have indeed shown that a prolonged contact with skin leaves burnished areas on the surface (Martisius et al., 2018; van Gijn et al., 2020). Given the fragility of the material, they were probably not intended for constant everyday use, but for occasional and deliberate display, during specific acts and events, such as annual festivities, initiation rituals, coming of age, etc. Looking at the diameter, the majority of the annulets in our assemblage were too small for an adult, but would fit the size of a child’s hand. At Aşağı Pınar, which has a significantly larger assemblage, also large portion of it (41%) has a diameter range between 4 and 7 cm (Aytek, 2015). Overall, the sizes of the clay examples from the Balkans are comparable with the stone bracelets in the wider Mediterranean (Martínez-Sevilla et al., 2021), indicating a comparable function, too. Furthermore, the ceramic bracelets are always found in habitat contexts, so it seems they were part of the ornamental world of the living. The burial record of the Neolithic in the south-central Balkans is slim, but none of the burials discovered so far contain ceramic annulets.

5 Conclusion

The ceramic annulets of the Balkan Neolithic were used as bracelets or personal adornment. From the data we collected from Amzabegovo and Svinjarička Čuka, we understand that they were not mass-produced items for common use, but a rather specific item produced for specific occasions and individuals, without implying social stratification. Judging by their size, most of the annulets were intended for children, but this was not an exclusive group as small number could have been used by adults as well.

The ceramic bracelets are not uniform in technological details, but they are homogeneous in their appearance as ring shaped, smoothed items, made of the same fabrics as the pottery. The craftsperson mainly kept a simple working technique, which is rolling a clay coil and connecting the ends. The overwhelming majority are simple cylindrical shaped coils, but some were flattened on the exterior or the interior, extended in height, or with angular body (trapeze or triangular cross section). The diversification seems to advance towards the mid-sixth millennium BC, when they were also the most numerous. Some were well smoothed, while others were roughly shaped. All this suggests that the ceramic annulets were embedded in the local ceramic production, probably at a household level.

The ceramic bracelets were not part of the Neolithic during the seventh millennium BC in Anatolia and the Aegean. In these regions, the personal adornments were manufactured in stone, shell, bone and teeth, in continuation with earlier traditions. Not far north of the Aegean shore, in the Balkan interior along the Vardar, Morava and Struma Rivers, they were replaced by clay. These clay objects are a true invention of the picturesque “clayscapes world” of Bánffy (2019), from its southern fringe to the northernmost reach, crossing the borders of the regional and local cultural groups but also of the climatic and environmental belts, from the sub-Mediterranean to the Continental. And it seems they also disappeared along the transformation of the Balkan Neolithic communities into the following Vinča and LBK conglomerates, when clay was replaced by stones and shells for bracelets (Vitezović & Antonović, 2020). Considering the available absolute dates, the latest ceramic annulets in this area are dated at around 5500–5400 BCE. They disappeared the same way they appeared, as a roughly synchronous event throughout the entire dispersal area after being produced for about half a millennium.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Elena Kanzurova, Goce Naumov, Malgorzata Grebska-Kulow, Krum Bacvarov and Nikolina Nikolova for sharing unpublished information. We would also like to thank Hans Gebel, Mehmet Özdoğan, Emma Baysal and Dmytro Kiosak for vital discussions and insights. Finally, we would like to thank the two anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments.

-

Funding information: The presented work is part of an ongoing comparative studies of the Vardar-Morava region, an initiative of the Horejs research group at the Austrian Archaeological Institute (OeAI), of which both authors are part of, and which is funded by the Austrian Academy of Sciences. As part of it, D.S. benefitted from a JESH grant, awarded by the Academy, in support of the project “The Vardar-Morava neolithization corridor: embedding data and building narratives.” Field work and analyses at Svinjarička Čuka are financially supported by the OeAI, the Austrian Science Fund (FWF), the OeAD and the BmEIA. The excavations at Amzabegovo are financially supported with grants from the Ministry of Culture and Tourism of N. Macedonia.

-

Author contributions: Both authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission. Both authors designed the concept of this study, gathered data and prepared the manuscript.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Aytek, Ö. (2015). Aşaği Pinar höyüğü’nde bulunan kil bilezik/halkalar üzerine bir ön değerlendirme. In C. Şimşek, B. Duman, & E. Konakçı (Eds.), Essays in Honor of Mustafa Büyükkolancı (pp. 55–70). Ege Yayinlari.Suche in Google Scholar

Bains, R., Vasic, M., Bar-Yosef, D., Russell, N., Wright, K. I., & Doherty, C. (2013). A technological approach to the study of personal ornamentation and social expression at Catalhoyuk. In I. Hodder (Ed.), Substantive Technologies at Çatalhöyük: Reports from the 2000–2008 Seasons (pp. 331–364). British Institute at Ankara, Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Baker, J., Rigaud, S., Pereira, D., Courtenay, L. A., & d’Errico, F. (2024). Evidence from personal ornaments suggest nine distinct cultural groups between 34,000 and 24,000 years ago in Europe. Nature Human Behaviour, 8(3), 431–444. doi: 10.1038/s41562-023-01803-6.Suche in Google Scholar

Ballmer, A., Stojanovski, D., Pearce, M., Danev, A., Friedrich, R. (submitted). A revisited absolute chronology of the Neolithic occupation sequence at Amzabegovo (Sveti Nikole, North Macedonia). Radiocarbon.Suche in Google Scholar

Bánffy, E. (2019). First Farmers of the Carpathian Basin Changing patterns in subsistence, ritual and monumental figurines. The Prehistoric Society/Oxbow Books.Suche in Google Scholar

Baysal, E. L. (2019). Personal Ornaments in Prehistory: An exploration of body augmentation from the Palaeolithic to the Early Bronze Age. Oxbow Books.10.2307/j.ctvpmw46dSuche in Google Scholar

Burke, C. (2022). Potting Links: The Starčevo ceramic repertoire of Svinjarička Čuka, Serbia. In L. Fidanoski & G. Naumov (Eds.), Neolithic in Macedonia - recent research and analyses. Center for Prehistoric Research.Suche in Google Scholar

Çilingiroğlu, Ç. (2005). The concept of “Neolithic package”: Considering its meaning and applicability. Documenta Praehistorica, 32, 1–13. doi: 10.4312/dp.32.1.Suche in Google Scholar

Dergachev, A. V., & Larina, V. O. (2015). Monuments of Criş Culture in Moldova: (with catalogue). Aкaд. Hayк Pecп. Moлдoвы, Ин-т кyльтyp. нacлeдия.Suche in Google Scholar

Detev, P. (1950). Selistnata mogila Banjata pri Kapitan Dimitrievo. Godišnik Na Narodnija Arheologičeski Muzej Plovdiv, 2, 1–23.Suche in Google Scholar

Detev, P. (1959). Materiali za Praistoriyata na Plovdiv. Annual National Archaeological Museum Plovdiv, 3, 3–80.Suche in Google Scholar

Dimitrijević, V., Naumov, G., Fidanoski, L., & Stefanović, S. (2021). A string of marine shell beads from the Neolithic site of Vršnik (Tarinci, Ovče pole), and other marine shell ornaments in the Neolithic of North Macedonia. Anthropozoologica, 56(4), 57–70. doi: 10.5252/anthropozoologica2021v56a4.Suche in Google Scholar

Elenski, N. (2006). Trench excavations at Dzhulyunitza-Smardesh early Neolithic site, Veliko Tarnovo region (preliminary report). Apxeoлoгия, 1–4, 96–117.Suche in Google Scholar

Erim-Özdoğan, A. (2011). Çayönü. In M. Özdoğan, N. Basgelen, & P. Kuniholm (Eds.), The neolithic in Turkey. New Excavations & new research - The Tigris Basin (Vol. 1, pp. 185–269). Archaeology and Art Publications.Suche in Google Scholar

Garašanin, M. (1979). Centralnobalkanska zona. In Praistorija Jugoslavenskih zemalja, vol. 2: Neolitsko doba (pp. 79–212). Akademija nauka i umjetnosti Bosne i Hercegovine.Suche in Google Scholar

Garašanin, M. (1982). The stone age in the Central Balkan area. In The Cambridge ancient history (pp. 75–135). Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CHOL9780521224963.003.Suche in Google Scholar

Garašanin, M. (1998). Kulturströmungen im Neolithikum des südlichen Balkanraumes. Prähistorische Zeitschrift, 73(1), 25–51. doi: 10.1515/prhz.2013.73.1.25.Suche in Google Scholar

Garašanin, M., Garašanin, D., & Sanev, V. (2009). Anzabegovo - the early and middle Neolithic settlement in Macedonia. Institute for Preservation of Cultural Monuments and Museum.Suche in Google Scholar

Gebel, H. G. K. (2023). The Neolithic of the Greater Petra area: The early 1980’s research history. In S. Kerner, O. al-Ghul, & H. Hayajneh (Eds.), Excavations, surveys and heritage. Essays on southwest Asian archaeology in honour of Zeidan Kafafi (marru 7). Zaphon.Suche in Google Scholar

Gimbutas, M. (1974). Anza, ca. 6500–5000 BC: A cultural yardstick for the study of Neolithic southeast Europe. Journal of Field Archaeology, 1(1–2), 27–66.10.1179/jfa.1974.1.1-2.27Suche in Google Scholar

Gimbutas, M. (1976). Neolithic Macedonia: As reflected by excavation at Anza, southeast Yugoslavia. Institute of Archaeology, University of California.Suche in Google Scholar

Hofmanová, Z., Kreutzer, S., Hellenthal, G., Sell, C., Diekmann, Y., Díez-Del-Molino, D., Van Dorp, L., López, S., Kousathanas, A., Link, V., Kirsanow, K., Cassidy, L. M., Martiniano, R., Strobel, M., Scheu, A., Kotsakis, K., Halstead, P., Triantaphyllou, S., Kyparissi-Apostolika, N., … Burger, J. (2016). Early farmers from across Europe directly descended from Neolithic Aegeans. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 113(25), 6886–6891. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1523951113.Suche in Google Scholar

Horejs, B., Bulatović, A., Brandl, M., Dietrich, L., Milić, B., Mladenović, O., Waltenberger, L., & Webster, L. (2025). Fresh light on Balkan prehistory: Highlights from Svinjarička Čuka (Serbia). Antiquity, 1–7. doi: 10.15184/aqy.2025.34.Suche in Google Scholar

Horejs, B., Bulatovic, A., Bulatovic, J., Brandl, M., Burke, C., Filipovic, D., & Milic, B. (2019). New insights into the later stage of the neolithisation process of the central Balkans. First excavations at Svinjarička Čuka 2018. In Archaeologia Austriaca (Vol. 103, pp. 175–226). Verlag der Oesterreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften. doi: 10.1553/archaeologia103s175.Suche in Google Scholar

Horejs, B., Bulatović, A., Bulatović, J., Burke, C., Brandl, M., Dietrich, L., Filipović, D., Milić, B., Mladenović, O., Schinnerl, N., Schroedter, T. M., & Webster, L. (2022). New Multi-disciplinary Data from the Neolithic in Serbia. The 2019 and 2021 Excavations at Svinjarička Čuka. Archaeologia Austriaca, 106, 255–317. doi: 10.1553/archaeologia106s255.Suche in Google Scholar

Horejs, B., Milić, B., Ostmann, F., Thanheiser, U., Weninger, B., & Galik, A. (2015). The Aegean in the early 7th millennium BC: Maritime networks and colonization. Journal of World Prehistory, 28(4), 289–330. doi: 10.1007/s10963-015-9090-8.Suche in Google Scholar

Ifantidis, F. (2019). Practices of personal adornment in Neolithic Greece. Archaeopress.10.2307/j.ctv1zckxq8Suche in Google Scholar

Ifantidis, F. (2020). Self-adorned in Neolithic Greece: A biographical synopsis. In M. Mărgărit & A. Boroneanț (Eds.), Beauty and the Eye of the Beholder. Personal adornments across the millennia. Cetatea de scaun. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/343006959.Suche in Google Scholar

Kalicz, N. (2011). Méhtelek the first excavated site of the Méhtelek group of the Early Neolithic Körös Culture in the Carpathian Basin (BAR, Vol. 2321). Archaeopress.10.30861/9781407309040Suche in Google Scholar

Kozlowski, S., & Aurenche, O. (2005). Territories, Boundaries and Cultures in the Neolithic Near East (BAR, Vol. 1362). Archaeopress.10.30861/9781841718071Suche in Google Scholar

Krauß, R., Marinova, E., De Brue, H., & Weninger, B. (2018). The rapid spread of early farming from the Aegean into the Balkans via the Sub-Mediterranean-Aegean Vegetation Zone. Quaternary International, 496, 24–41. doi: 10.1016/j.quaint.2017.01.019.Suche in Google Scholar

Lazarovici, G., & Maxim, Z. (1995). Gura Baciului. Bibliotheca Musei Napocensis XI. Cluj-Napoca: Ministry of Culture, National History Museum of Transylavania.Suche in Google Scholar

Lichardus-Itten, M., Demoule, J.-P., Perničeva, L., Grebska-Kulova, M., & Kulov, I. (2002). The site of Kovačevo and the beginnings of the Neolithic period in Southwestern Bulgaria. The French-Bulgarian excavations 1986–2000. In M. Lichardus-Itten, J. Lichardus, & V. Nikolov (Eds.), Beiträge zu Jungsteinzeitlichen Forschungen in Bulgarien. Saarbrücker Beiträge zur Altertumskunde, band 74 (pp. 99–158). Dr. Rudolf Habelt GMBH.Suche in Google Scholar

Martínez-Sevilla, F., Baysal, E. L., Micheli, R., Ifantidis, F., & Lugliè, C. (2021). A very early “fashion”: Neolithic stone bracelets from a Mediterranean perspective. Open Archaeology, 7(1), 815–831. doi: 10.1515/opar-2020-0156.Suche in Google Scholar

Martisius, N. L., Sidéra, I., Grote, M. N., Steele, T. E., Mcpherron, S. P., & Schulz-Kornas, E. (2018). Time wears on: Assessing how bone wears using 3D surface texture analysis. PLoS ONE, 13(11), 22. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0206078.Suche in Google Scholar

Mathieson, I., Alpaslan-Roodenberg, S., Posth, C., Szécsényi-Nagy, A., Rohland, N., Mallick, S., Olalde, I., Broomandkhoshbacht, N., Candilio, F., Cheronet, O., Fernandes, D., Ferry, M., Gamarra, B., Fortes, G. G., Haak, W., Harney, E., Jones, E., Keating, D., Krause-Kyora, B., … Reich, D. (2018). The genomic history of southeastern Europe. Nature, 555(7695), 197–203. doi: 10.1038/nature25778.Suche in Google Scholar

Minichreiter, K. (2007). Slavonski Brod, Galovo. Ten years of archaeological excavations. Institut za arheologiju.Suche in Google Scholar

Mould, C. A., Ridley, C., & Wardle, K. A. (2000). The small finds: Additional clay objects. In C. Ridley, K. A. Wardle, & C. A. Mould (Eds.), Servia I: Anglo-Hellenic rescue excavations 1971-73 (pp. 264–275). British School at Athens.Suche in Google Scholar

Pavúk, J., & Bakamska, A. (2021). Die neolithische Tellsiedlung in Gălăbnik. Studien zur Chronologie des Neolithikums auf dem Balkan (MPK, Vol. 91). Verlag der österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften. doi: 10.2307/j.ctv1z7kj4h.Suche in Google Scholar

Perić, S. (2008). The oldest cultural horizon of trench XV at Drenovac. Starinar, LVIII, 29–50.10.2298/STA0858029PSuche in Google Scholar

Perlès, C. (2018). Ornaments and other ambiguous artifacts from Franchthi. The Palaeolithic and the Mesolithic (Vol. 1). Indiana University Press.10.2307/j.ctt2204qrpSuche in Google Scholar

Perlès, C. (2021). What details can tell us. Perforated shells from the Mesolithic–Neolithic transition at Franchthi (Greece). In H. V. Mattson (Ed.), Personal adornment and the construction of identity (pp. 25–40). Oxbow Books. doi: 10.2307/j.ctv24q4z2g.6.Suche in Google Scholar

Porčić, M. (2024). The beginning of the Neolithic in the central Balkans: Knowns and unknowns. Documenta Praehistorica, 51, 178–193. doi: 10.4312/dp.51.11.Suche in Google Scholar

Starnini, E. (2014). Fired clay, plastic figurines of the Körös culture from the excavations of the early Neolithic sites of the Körös culture in the Körös valley, Hungary (P. Biagi, Ed.; Quaderno 14). Società per la preistoria e protostoria della regione Friuli-Venezia Giulia.Suche in Google Scholar

Stojanovski, D. (2017). Grnčarica: A contribution to the early Neolithic puzzle of the Balkans. Center for Prehistoric Research.Suche in Google Scholar

van Gijn, A., Verbaas, A., Dekker, J., Feisrami, T., de Koning, N., Spithoven, M., Timmer, T., & Vernon, F. (2020). Studying the life history of vessels. Creating a reference collection for microwear studies of pottery. In A. van Gijn, J. Fries-Knoblach, & P. W. Stockhammer (Eds.), Pots and practices. An experimental and microwear approach to Early Iron Age vessel biographies (pp. 65–109). Sidestone Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Vasileva, Z., & Hadzipetkov, I. (2014). Ornaments. In J. Roodenberg, K. Leshtakov, & V. Petrova (Eds.), Yabalkovo (Maritsa Project, Vol. 1). ATE, Sofia University “St. Kliment Ohridski.”Suche in Google Scholar

Vitezović, S., & Antonović, D. (2020). Jewellery from osseous and lithic raw materials in the Vinča culture. In M. Mărgărit & A. Boroneanț (Eds.), Beauty and the eye of the beholder. Personal adornments across the millennia. Cetatea de scaun.Suche in Google Scholar

White, R. (1993). Technological and social dimensions of Aurignacian-age body ornaments across Europe. In R. White, H. Knecht, & A. Pike-Tay (Eds.), Before Lascaux: The complex record of the Early Upper Paleolithic (pp. 279–299). CRC Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Whittle, A., Bartosiewicz, L., Borić, D., Pettitt, P., & Richards, M. P. (2002). In the beginning: New radiocarbon dates for the Early Neolithic in northern Serbia and south-east Hungary. Antæus, 25, 63–117.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Etched in Stone: The Kevermes Stone Stela From the Great Hungarian Plain

- Waste Around Longhouses: Taphonomy on LBK Settlement in Hlízov

- Raw Materials and Technological Choices: Case Study of Neolithic Black Pottery From the Middle Yangtze River Valley of China

- Disentangling Technological Traditions: Comparative Analysis of Chaînes Opératoires of Painted Pre-Hispanic Ceramics From Nariño, Colombia

- Ancestral Connections: Re-Evaluating Concepts of Superimpositioning and Vandalism in Rock Art Studies

- Disability and Care in Late Medieval Lund, Sweden: An Analysis of Trauma and Intersecting Identities, Aided by Photogrammetric Digitization and Visualization

- Assessing the Development in Open Access Publishing in Archaeology: A Case Study From Norway

- Decorated Standing Stones – The Hagbards Galge Monument in Southwest Sweden

- Geophysical Prospection of the South-Western Quarter of the Hellenistic Capital Artaxata in the Ararat Plain (Lusarat, Ararat Province, Armenia): The South-West Quarter, City Walls and an Early Christian Church

- Lessons From Ceramic Petrography: A Case of Technological Transfer During the Transition From Late to Inca Periods in Northwestern Argentina, Southern Andes

- An Experimental and Methodological Approach of Plant Fibres in Dental Calculus: The Case Study of the Early Neolithic Site of Cova del Pasteral (Girona, Spain)

- Bridging the Post-Excavation Gaps: Structured Guidance and Training for Post-Excavation in Archaeology

- Everyone Has to Start Somewhere: Democratisation of Digital Documentation and Visualisation in 3D

- The Bedrock of Rock Art: The Significance of Quartz Arenite as a Canvas for Rock Art in Central Sweden

- The Origin, Development and Decline of Lengyel Culture Figurative Finds

- New “Balkan Fashion” Developing Through the Neolithization Process: The Ceramic Annulets of Amzabegovo and Svinjarička Čuka

- From a Medieval Town to the Modern Fortress of Rosas (Girona-Spain). Combining Geophysics and Archaeological Excavation to Understand the Evolution of a Strategic Coastal Settlement

- Technical Transfers Between Chert Knappers: Investigating Gunflint Manufacture in the Eastern Egyptian Desert (Wadi Sannur, Northern Galala, Egypt)

- Early Neolithic Pottery Production in the Maltese Islands: Initiating a Għar Dalam and Skorba Pottery Fabric Classification

- Revealing the Origins: An Interdisciplinary Study Into the Provenance of Sacral Microarchitecture–The Unique Case of the Church Model From Žatec in Bohemia

- An Analogical and Analytical Approach to the Burçevi Monumental Tomb

- A Glimpse at Raw Material Economy and Production of Chipped Stones at the Neolithic (Starčevo) Site of Svinjarička Čuka, South Serbia

- Archaeological Lithotheques of Siliceous Rocks in Spain: First Diagnosis of the Lithotheque Thematic Network

- Mapping Changes in Settlement Number and Demography in the South of Israel from the Hellenistic to the Early Islamic Period

- Review Article

- Structural Measures Against the Risks of Flash Floods in Patara and Consequent Considerations Regarding the Location of the Oracle Sanctuary of Apollo

- Commentary Article

- A Framework for Archaeological Involvement with Human Genetic Data for European Prehistory

- Special Issue on Digital Religioscapes: Current Methodologies and Novelties in the Analysis of Sacr(aliz)ed Spaces, edited by Anaïs Lamesa, Asuman Lätzer-Lasar - Part II

- Goats and Goddesses. Digital Approach to the Religioscapes of Atargatis and Allat

- Conceiving Elements of Divinity: The Use of the Semantic Web for the Definition of Material Religiosity in the Levant During the Second Millennium BCE

- Deep Mapping the Asklepieion of Pergamon: Charting the Path Through Challenges, Choices, and Solutions

- Special Issue on Engaging the Public, Heritage and Educators through Material Culture Research, edited by Katherine Anne Wilson, Christina Antenhofer, & Thomas Pickles

- Inventories as Keys to Exploring Castles as Cultural Heritage

- Hohensalzburg Digital: Engaging the Public via a Local Time Machine Project

- Monastic Estates in the Wachau Region: Nodes of Exchange in Past and Present Days

- “Meitheal Adhmadóireachta” Exploring and Communicating Prehistoric Irish Woodcraft Through Remaking and Shared Experience

- Community, Public Archaeology, and Co-construction of Knowledge Through the Educational Project of a Rural Mountain School

- Valuing Material Cultural Heritage: Engaging Audience(s) Through Development-Led Archaeological Research

- Engaging the Public Through Prehistory: Experiences From an Inclusive Perspective

- Material Culture, the Public, and the Extraordinary – “Unloved” Museums Objects as the Tool to Fascinate

- Archaeologists on Social Media and Its Benefits for the Profession. The Results and Lessons Learnt from a Questionnaire

- Special Issue on Network Perspectives in the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East and Eastern Mediterranean, edited by Maria Gabriella Micale, Helen Dawson, & Antti A. Lahelma

- Network Perspectives in the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East and Eastern Mediterranean

- Networks of Pots: The Usage of Ceramics in Network Analysis in Mediterranean Archaeology

- Networks of Knowledge, Materials, and Practice in the Neolithic Zagros

- Weak Ties on Old Roads: Inscribed Stopping-Places and Complex Networks in the Eastern Desert of Graeco-Roman Egypt

- Mediterranean Trade Networks and the Diffusion and Syncretism of Art and Architecture Styles at Delos

- People and Things on the Move: Tracking Paths With Social Network Analysis

- Networks and the City: A Network Perspective on Procopius De Aed. I and the Building of Late Antique Constantinople

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Etched in Stone: The Kevermes Stone Stela From the Great Hungarian Plain

- Waste Around Longhouses: Taphonomy on LBK Settlement in Hlízov

- Raw Materials and Technological Choices: Case Study of Neolithic Black Pottery From the Middle Yangtze River Valley of China

- Disentangling Technological Traditions: Comparative Analysis of Chaînes Opératoires of Painted Pre-Hispanic Ceramics From Nariño, Colombia

- Ancestral Connections: Re-Evaluating Concepts of Superimpositioning and Vandalism in Rock Art Studies

- Disability and Care in Late Medieval Lund, Sweden: An Analysis of Trauma and Intersecting Identities, Aided by Photogrammetric Digitization and Visualization

- Assessing the Development in Open Access Publishing in Archaeology: A Case Study From Norway

- Decorated Standing Stones – The Hagbards Galge Monument in Southwest Sweden

- Geophysical Prospection of the South-Western Quarter of the Hellenistic Capital Artaxata in the Ararat Plain (Lusarat, Ararat Province, Armenia): The South-West Quarter, City Walls and an Early Christian Church

- Lessons From Ceramic Petrography: A Case of Technological Transfer During the Transition From Late to Inca Periods in Northwestern Argentina, Southern Andes

- An Experimental and Methodological Approach of Plant Fibres in Dental Calculus: The Case Study of the Early Neolithic Site of Cova del Pasteral (Girona, Spain)

- Bridging the Post-Excavation Gaps: Structured Guidance and Training for Post-Excavation in Archaeology

- Everyone Has to Start Somewhere: Democratisation of Digital Documentation and Visualisation in 3D

- The Bedrock of Rock Art: The Significance of Quartz Arenite as a Canvas for Rock Art in Central Sweden

- The Origin, Development and Decline of Lengyel Culture Figurative Finds

- New “Balkan Fashion” Developing Through the Neolithization Process: The Ceramic Annulets of Amzabegovo and Svinjarička Čuka

- From a Medieval Town to the Modern Fortress of Rosas (Girona-Spain). Combining Geophysics and Archaeological Excavation to Understand the Evolution of a Strategic Coastal Settlement

- Technical Transfers Between Chert Knappers: Investigating Gunflint Manufacture in the Eastern Egyptian Desert (Wadi Sannur, Northern Galala, Egypt)

- Early Neolithic Pottery Production in the Maltese Islands: Initiating a Għar Dalam and Skorba Pottery Fabric Classification

- Revealing the Origins: An Interdisciplinary Study Into the Provenance of Sacral Microarchitecture–The Unique Case of the Church Model From Žatec in Bohemia

- An Analogical and Analytical Approach to the Burçevi Monumental Tomb

- A Glimpse at Raw Material Economy and Production of Chipped Stones at the Neolithic (Starčevo) Site of Svinjarička Čuka, South Serbia

- Archaeological Lithotheques of Siliceous Rocks in Spain: First Diagnosis of the Lithotheque Thematic Network

- Mapping Changes in Settlement Number and Demography in the South of Israel from the Hellenistic to the Early Islamic Period

- Review Article

- Structural Measures Against the Risks of Flash Floods in Patara and Consequent Considerations Regarding the Location of the Oracle Sanctuary of Apollo

- Commentary Article

- A Framework for Archaeological Involvement with Human Genetic Data for European Prehistory

- Special Issue on Digital Religioscapes: Current Methodologies and Novelties in the Analysis of Sacr(aliz)ed Spaces, edited by Anaïs Lamesa, Asuman Lätzer-Lasar - Part II

- Goats and Goddesses. Digital Approach to the Religioscapes of Atargatis and Allat

- Conceiving Elements of Divinity: The Use of the Semantic Web for the Definition of Material Religiosity in the Levant During the Second Millennium BCE

- Deep Mapping the Asklepieion of Pergamon: Charting the Path Through Challenges, Choices, and Solutions

- Special Issue on Engaging the Public, Heritage and Educators through Material Culture Research, edited by Katherine Anne Wilson, Christina Antenhofer, & Thomas Pickles

- Inventories as Keys to Exploring Castles as Cultural Heritage

- Hohensalzburg Digital: Engaging the Public via a Local Time Machine Project

- Monastic Estates in the Wachau Region: Nodes of Exchange in Past and Present Days

- “Meitheal Adhmadóireachta” Exploring and Communicating Prehistoric Irish Woodcraft Through Remaking and Shared Experience

- Community, Public Archaeology, and Co-construction of Knowledge Through the Educational Project of a Rural Mountain School

- Valuing Material Cultural Heritage: Engaging Audience(s) Through Development-Led Archaeological Research

- Engaging the Public Through Prehistory: Experiences From an Inclusive Perspective

- Material Culture, the Public, and the Extraordinary – “Unloved” Museums Objects as the Tool to Fascinate

- Archaeologists on Social Media and Its Benefits for the Profession. The Results and Lessons Learnt from a Questionnaire

- Special Issue on Network Perspectives in the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East and Eastern Mediterranean, edited by Maria Gabriella Micale, Helen Dawson, & Antti A. Lahelma

- Network Perspectives in the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East and Eastern Mediterranean

- Networks of Pots: The Usage of Ceramics in Network Analysis in Mediterranean Archaeology

- Networks of Knowledge, Materials, and Practice in the Neolithic Zagros

- Weak Ties on Old Roads: Inscribed Stopping-Places and Complex Networks in the Eastern Desert of Graeco-Roman Egypt

- Mediterranean Trade Networks and the Diffusion and Syncretism of Art and Architecture Styles at Delos

- People and Things on the Move: Tracking Paths With Social Network Analysis

- Networks and the City: A Network Perspective on Procopius De Aed. I and the Building of Late Antique Constantinople