Conceiving Elements of Divinity: The Use of the Semantic Web for the Definition of Material Religiosity in the Levant During the Second Millennium BCE

-

Nicola Laneri

, Lorenzo Nigro

Abstract

Research on how forms of religiosity are produced through the interaction of local, exogenous, and hybrid elements is fundamental for the improvement of religious studies. This becomes particularly noteworthy in the context of the Levant during the Second Millennium BCE when cultural hybridization phenomena played a pivotal role in shaping novel religious beliefs. Such an exploration, in fact, opens up avenues in the process that ultimately led to the emergence of the Israelite monolatry in the First Millennium BCE. To reach this target, the Godscapes project combines a material culture perspective with the Semantic Web, an innovative application of artificial intelligence that will aid researchers in understanding religious phenomena by not only reconstructing inherent missing information within the data but also furnishing a powerful tool to search, query, and visualize them. Hence, the project aims to build “The Godscapes Ontology” (TGO) through a deconstruction process of the elements recognizable in four aspects associated with material religiosity: religious architecture, religious iconography, funerary rituals/beliefs, and religious texts. After introducing the project’s scope and methodology, the article will present the conceptual model for TGO, showing how the aforementioned aspects are related to each other in the construction of religious beliefs and practices. It will further detail the semantic ontology elaborated to model the religious architecture of the Second Millennium BCE Levant. Finally, the interrogation of the dataset through pilot queries in the Semantic Web language (SPARQL) will provide validation of the designed model, and assess the potential applications of the approach.

1 Introduction

During the last decade, numerous ancient and religious studies have been dedicated to reinforcing the pivotal importance of the use of material culture in interpreting religious beliefs and practices among both ancient and modern communities. Moreover, such a “material turn” involves exploring the incorporation and re-elaboration of exogenous elements in the creation of new forms of material religiosity, known as religious hybridization. Thus, adopting a material approach to the study of religion can support a research agenda aimed at explaining the phenomena of religious hybridization, especially in moments of dramatic cultural transformations.

Based on these premises, the Godscapes project seeks to employ an innovative scientific model that is grounded in a semantic vision of the web, namely the Semantic Web, in which machine-readable data enable software agents to query and manipulate information on users’ behalf. The objective is to dissect the selected data in an attempt to define how external elements act as triggers in transforming forms of religiosity. To reach this target, our research group has decided to focus on investigating religious architecture, iconicity, funerary, and written data within the Levantine region, including present-day Israel, Palestine, Jordan, Syria, and Lebanon, during the Second Millennium BCE. The selection of this particular region and period as a test case is motivated by the notable dynamics at work along the Levantine corridor, which witnessed a profound interchange between indigenous and exogenous elements, namely Egyptian, Syro-Mesopotamian, Aegean, and Anatolian, that shaped the polytheistic beliefs of the local communities. Moreover, this cultural and religious intermingling has been considered the source for the emergence of the Israelites’ monolatry. Relying on the technologies of the Semantic Web, the Godscapes project will thus provide a paradigm to scientifically define and interpret the relationship between exogenous and autochthonous elements of religiosity in Second Millennium BCE polytheisms in the Levant, with a particular focus on how these elements persisted and were reshaped in that syncretic experience that will merge in the construction of Israelites’ religious identity in the First Millennium BCE.

The present article aims to outline the project’s scope, theoretical foundations, and methodology. It will introduce the conceptual model for “The Godscapes Ontology” (TGO), which aims to formalize through its classes, relationships, and attributes how the previously mentioned components of material religion are interconnected in the constitution of religious practices and beliefs. Additionally, it will provide a more in-depth description of the semantic ontology created to build knowledge graphs about the religious architectures that make up the Godscapes dataset. Finally, the dataset will be interrogated through competence queries in the Semantic Web language (SPARQL) to validate the model and assess the potential applications of the approach.

2 For a Definition of Religious Hybridization

In a recent call to scholars in the realm of religious studies, there was an urging for upcoming researchers of religion to

Apply syncretism or hybridity … to the study of how religion is enmeshed with and co-produced in and through domains other than “religion” narrowly conceived, like language, the material world, the body, and technologies of media.

(Johnson, 2016, p. 14)

Thus, by linking various aspects of human life and knowledge and by envisioning the entanglement of things with humans and ideas (Stockhammer, 2012), the Godscapes project aims to elaborate a model to define how these elements are related to each other in the construction of religious beliefs and practices.

At the top of the renowned Hawkesian “Ladder of Inference” (Hawkes, 1954) which stated the structural difficulty of archaeology in tracing ancient thoughts, beliefs in spiritual beings, configurations of the cosmos, and conceptions of the afterlife that ancient societies had elaborated in more or less complex and institutionalized systems were long considered an elusive target for archaeology. However, in recent years, an innovative perspective known as “New Materialism” (Morgan, 2016) has emerged among the main theoretical strands of the post-humanist discourse asserting material agency in religious studies. According to the material approach, archaeological remains are dynamic entities that embody social meanings and cultural processes and thus embed hidden narratives about the intricate webs of connectivity between humans and other-than-humans. Among the key concepts enabled by this paradigmatic shift is an extension of the notion of relationality that forms the core of network theories which adopt as primary ontological units not single objects, but dynamic phenomena involving different actors and the processes of interaction between them (Laneri, 2023, 2024; Laneri & Steadman, 2023). In particular, the “Entanglement” approach (Hodder, 2011, 2012) defines explicitly the diverse nature of relationships among different kinds, humans, and things, providing a theoretical framework for the web of interconnectedness in which they are embroiled (Latour, 2005).

As a consequence, the materialization of religious practices and beliefs has taken a central position against a traditional focus on the spiritual aspects in studying ancient and modern religious phenomena that it is usually armed by forms of reductionism based on the false assumption that “there is nothing outside the text” (Engelke, 2012; Laneri, 2011, 2015; Morgan, 2016). When dealing with ancient societies, and archaeological data are the main driving factor in interpreting ancient religious practices, a thorough analysis of the material remains can become a unique tool in the process of reconstructing ancient religious beliefs. Even when texts are not available, or they represent just part of the whole story, the material approach enables researchers to visualize complex networks of social ties at various scales, allowing the detection of patterns of connectivity, and the evaluation of their nature and strength.

A material approach to the study of religions is pivotal especially when exogenous elements have been added in the creation of new forms of religiosity, that is the process of religious hybridization. The Godscapes project aims to tackle religious hybridization through a scientifically grounded model that will try to map syncretic forms of historical archives, because “religions are clusters of intersecting but mostly non-coherent networks, in which communication media, theologies, architecture, aesthetic values, ritual techniques, are all part of these complex networks” (Johnson, 2016, p. 13). This will require our ability to clearly answer the question of what syncretism or hybridity is claimed to be in a specific field of study, in this case, religion, and, more specifically, ancient forms of polytheism. In so doing, the concept of “material entanglement” that, according to Stockhammer (2013, p. 17), “signifies the creation of something new that is more than just the sum of its parts and combines the familiar with the previously foreign” can be a useful approach to define a “new taxonomic entity” that represents the typical material result of forms of hybridization characterizing the development of religiosity from a diachronic perspective.

To reach the purpose of this ambitious target, the project focuses on a geographical region (i.e., the Levant) and period (i.e., the Second Millennium BCE) that are fundamental in the history of religions, because it is this period that will bring about the burgeons of the Israelites’ monolatry and progressive henotheism that will mark the southern Levant during the Iron Age (Beckman & Lewis, 2006). Moreover, the Levantine corridor represents an incredible locale of cultural, economic, and religious interaction among Egyptian, Syro-Palestinian, Anatolian, and Aegean communities, that has been associated with the Second Millennium BCE cultures of the Biblical “land of Canaan,” and it, thus, represents a perfect crucible for forging new cultural and religious identities. In fact, as pointed out by Smith (2001, p. 14), “all of these people in the Levant, despite distances in time and space, shared many views of what deities were in general expected to be and do, although these people may have developed perceptions of deities specific of their cultures.” Thus, the project “Godscapes” wants to look “in the rear-view mirror” to lead the way for a scientific and coherent understanding of how hybrid forms of polytheistic religious practices and beliefs slowly turned into the monolatristic phenomenon that will mark the First Millennium BCE but, most of all, will become the pillar of modernity.

3 Framing Religious Encounters in the Second Millennium BCE Levant

Monotheism makes its appearance in the biblical texts dating to the sixth century BCE as the result of a lengthy process occurred within the Israelite society, where it seems to have served as “a rhetoric expressing and advancing the cause of Israelite monolatrous practice” (Smith, 2001, p. 12). In fact, the ancient roots of Israelite religious culture in the Early Iron Age (ca. 1200–1000 BCE) can hardly be disentangled from their Canaanite polytheistic background, perhaps most extensively represented in the older Ugaritic theology (Smith, 2001). Many have been theories on when, where, and how Israelite Yahwism originated, exploring in particular the manner in which an external element infiltrated a new cultural environment. For instance, the relationship between Second Millennium BCE forms of religiosity in the Levant and Egypt as exemplary for a source related to the origin of Israelite monolatry has created one of the most vibrant debates in the history of humankind. Based on a historical use of the Bible, scholars have imagined an Egyptian origin during the Late Bronze Age, when the tenth Pharaoh of XVIIIth dynasty, Amenhotep IV (1353–1336 BCE) introduced an innovative henotheistic belief in the god Aten, changing his royal name to Akhenaten (i.e., “Effective of the Aten”), and founding a new capital (Akhetaten, the modern village of Amarna: Kemp, 2012). Such an approach has been supported by a wide series of theories, some of which were based on fascination, and others on an attempt to combine Egyptian and Biblical sources (Assmann, 1998, 2014).

These ideas on the origin of Israelite monolatry in a Second Millennium BCE cultural and religious environment have only briefly used a holistic approach considering the complex cultural milieu of the second millennium BCE Levantine polytheistic traditions (Killebrew, 2005; Oggiano, 2005). In fact, this long stretch of land corresponded, during the period under study, to an extraordinary corridor not only for trade routes and military expansion but also to exchange knowledge and ideas reaching as far as Egypt, Mesopotamia, the Mediterranean, and the Arabian oasis (Aruz et al., 2009; Cohen & Adams, 2019; Matthiae et al., 2007). Although the area formed a major cultural unity, different regional trajectories can be discerned during the Middle Bronze Age: in the north, Levant urban centers did experience a continuity with the end of the third millennium BCE (Morandi Bonacossi, 2014); in the south, the flourishing of regional fortified centers was preceded by phases of societal reorganization and resilience as well as by the influence of Syro-Mesopotamian urban and architectural monumentality (Bietak et al., 2019; D’Andrea, 2014). Funerary evidence, such as the diffusion and local reworking of weapons for burial deposits, has been recently addressed as the product of cultural transfer and hybridization mechanisms spreading from Mesopotamia to Syria, Palestine, Northern Arabia, and Egypt (Homsher & Cradic, 2018; Miniaci, 2019; Montanari, 2020). Here, the most striking archaeological proof of a west Asiatic presence in the Middle Kingdom, and eventually giving rise to the Hyksos interlude in the Second Intermediate Period, was discovered in the Eastern Nile Delta (Bietak & Prell, 2019; Mourad, 2015). A process of material entanglement can also be envisioned in the remarkable consumption of Egyptian and Egyptianizing objects that are found in funerary contexts across the Levant, and the unparalleled case of Byblos on the Lebanese coast (Ahrens, 2020; Ben-Tor, 2007; Helck, 1971; Miniaci, 2018, 2020; Miniaci & Saler, 2021; Nigro, 2018).

The dynamics of interaction changed, in the Late Bronze Age, with the participation of the Canaanite city-states in the new “world system” as vassals of the “great kings” (Liverani, 1987, pp. 66–67) of the large regional states of the Eastern Mediterranean and the Near East (Pfälzner & Al Maqdisī, 2015). The dynamics at work are particularly evident in the diplomatic correspondence between the rulers of the time (Rainey, 2014), and in the development of an unprecedented “artistic internationalism” (Feldman, 2006). The beginning of Egyptian raids in the region, resulting in an increasing importance of the Egyptian administrative centers during the Amarna period (Burke, 2010; Burke et al., 2017; Bunimovitz, 2019; Höflmayer, 2015; Weinstein, 1981). Main cities like Megiddo and Hazor seem to have maintained their status, as suggested by the continuation of monumental buildings testifying the participation of the Canaanite centers to the ancient Syrian architectural tradition (Bonfil & Zarzecki-Peleg, 2007; Pfoh, 2016). Moreover, Egyptian cultic paraphernalia, such as the Qudshu plaque figurines, clay cobras, or the large quantity of royal scarabs associated with Amenhotep III and his wife Tiy, possibly hinting at a royal cult in Canaan, may point not only to ritual activity but also to the presence of Egyptian cultic personnel (Burke, 2020).

Sites such as Sidon, Qatna, and Ugarit reveal how ideas and beliefs had passed onto the local society, and archaeological remains expressing forms of entanglement are even more explicit at Byblos: here, for instance, the Egyptian goddess Hathor is labeled as “Lady of Byblos”; the god Resheph assumes Egyptian posture and iconography; figures of Anubis and Isis are scattered across the site. In fact, as correctly pointed out by Smith (2001), the archaeological research in the area has created a massive amount of data fundamental to interpret the relationship between biblical monotheism and polytheism in ancient Israel and neighboring cultures. However, research projects aiming at explaining how the interaction shaped local ritual and religion at both a public and private level have been carried out so far only at sparse sites (Koch, 2019).

Based on these historical premises, there is a great need for a more coherent study on how phenomena of cultural hybridization affected the religiosity of the communities inhabiting the “Land of Canaan” during the Second Millennium BCE. To reach this target, it appears of fundamental importance to apply a scientifically proven methodology to define the characteristic markers of Second Millennium BCE Levantine religiosity in specific aspects of religious materiality and, consequentially, demonstrate how a syncretic outcome can be considered the result of a complex network of interreligious encounters originated during the Second Millennium BCE.

4 Objectives and Methods: Mapping Material Religion Through the Semantic Web

With the aim to reach a better understanding of how religious phenomena originate and spread, the approach proposed by the Godscapes project is based on deconstructing the elements recognizable in four fundamental aspects associated with material religiosity: (1) religious architecture, (2) religious iconography, (3) funerary rituals/beliefs, and (4) religious texts. The work of deconstruction is operated through the application of an epistemological process in which a suite of semantic ontologies is designed, implemented, linked to the most popular semantic web vocabularies in the field, and populated through a meticulous process of data entry.

The Semantic Web, or the Web of Data, offers well-established methodologies and tools to semantically model application domains and to integrate data, rendering it as global entities publicly reachable on the web (Berners-Lee et al., 2001). It envisions a web of interconnected data where web content bears explicit meaning, allowing software agents to automatically query and manipulate information on the users’ behalf. In such a framework, information can be accessed and updated on a global scale, fostering greater coherence and a wider dissemination of knowledge. Furthermore, the application of automated reasoning procedures offers the opportunity for a deeper understanding of a knowledge domain by extracting and processing implicit information from the data (Cantone et al., 2019, p. 142).

In the Semantic Web, ontologies define representational primitives (classes and attributes) used to model knowledge domains. To ensure smooth machine interoperability, applications that process information automatically require a language with formal syntax and semantics, adding to its expressive power. The W3C developed the Web Ontology Language (OWL) to handle complex knowledge representation, allowing programs to verify knowledge consistency and infer new information. OWL, the standard for ontology representation, extends beyond the capabilities of resource description framework and resource description framework schema by providing enhanced tools for building ontologies in real-world domains. Its latest version (OWL 2.1) offers advanced constructs for this purpose (Cantone et al., 2019, p. 142).

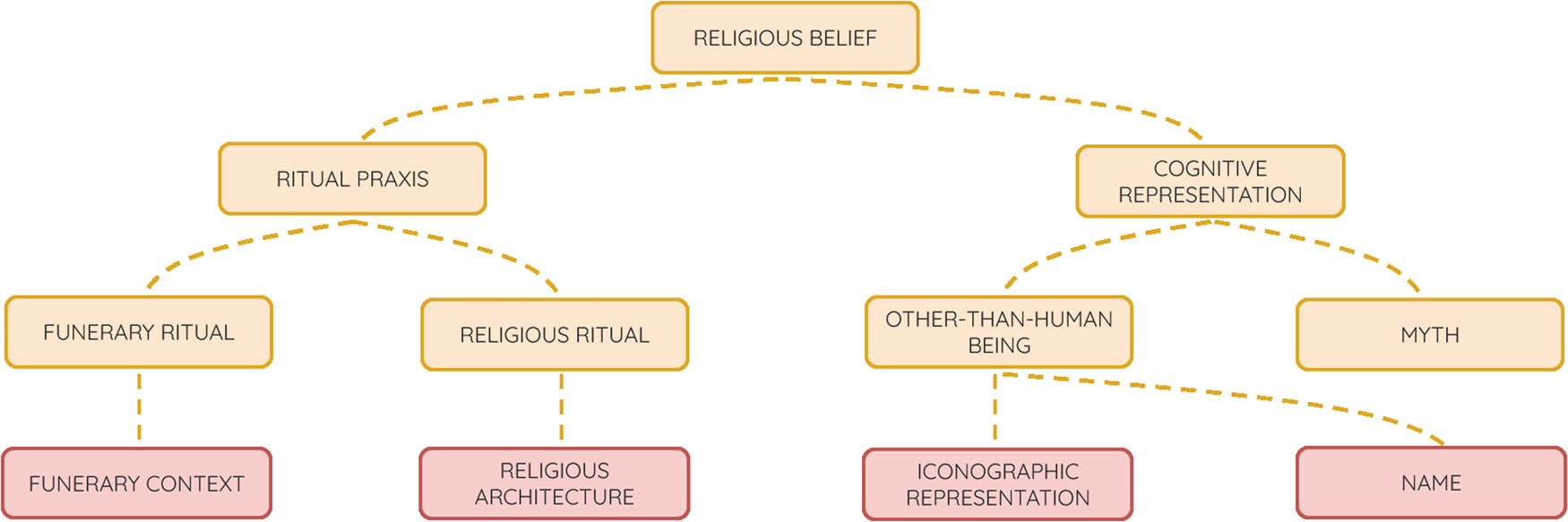

To assess the potential of the Semantic Web for mapping religious materiality, the research work has integrated a top-down with a bottom-up approach, working on the conceptual layout of the ontologies while standardizing the metadata for the creation of the Godscapes dataset. In TGO (Figure 1), religious belief is regarded as a co-product of ritual behaviors and cognitive representations which, according to the Mental Functioning Ontology, are shaped by the individuals who hold them as part of their mental framework (Schulz & Jansen, 2018). Within these broad categories, the instances entered in the Godscapes dataset aim at approaching emic knowledge systems. Thus, our project focuses on other-than-human beings that encompass a wide range of entities, from gods and goddesses to hybrid creatures, as indicated by the Ugaritic term for the divine sphere ’il (Smith, 2001), and myths referring to the actions and the relationships they engage. Ritual behaviors are reconstructed from their material correlates recognizable in both funerary and religious archaeological contexts. From these classes stem the four categories which represent the main core of our research agenda, and the ontologies to model them. Thus, a crucial step of the research work was the design of a suite of OWL 2 ontologies, each describing one of the four principal characteristics associated with material religiosity, namely religious architecture, religious iconography, funerary data, and religious texts, together with their related epistemological analysis, thus resulting in an unambiguous and shared formalization of the religious concerns. TGO serves as a semantic glue connecting them via a set of ontological primitives, which are also employed to encompass the huge amount of digital and non-digital bibliography concerning the Godscapes domain.

Conceptual design of The Godscapes Ontology.

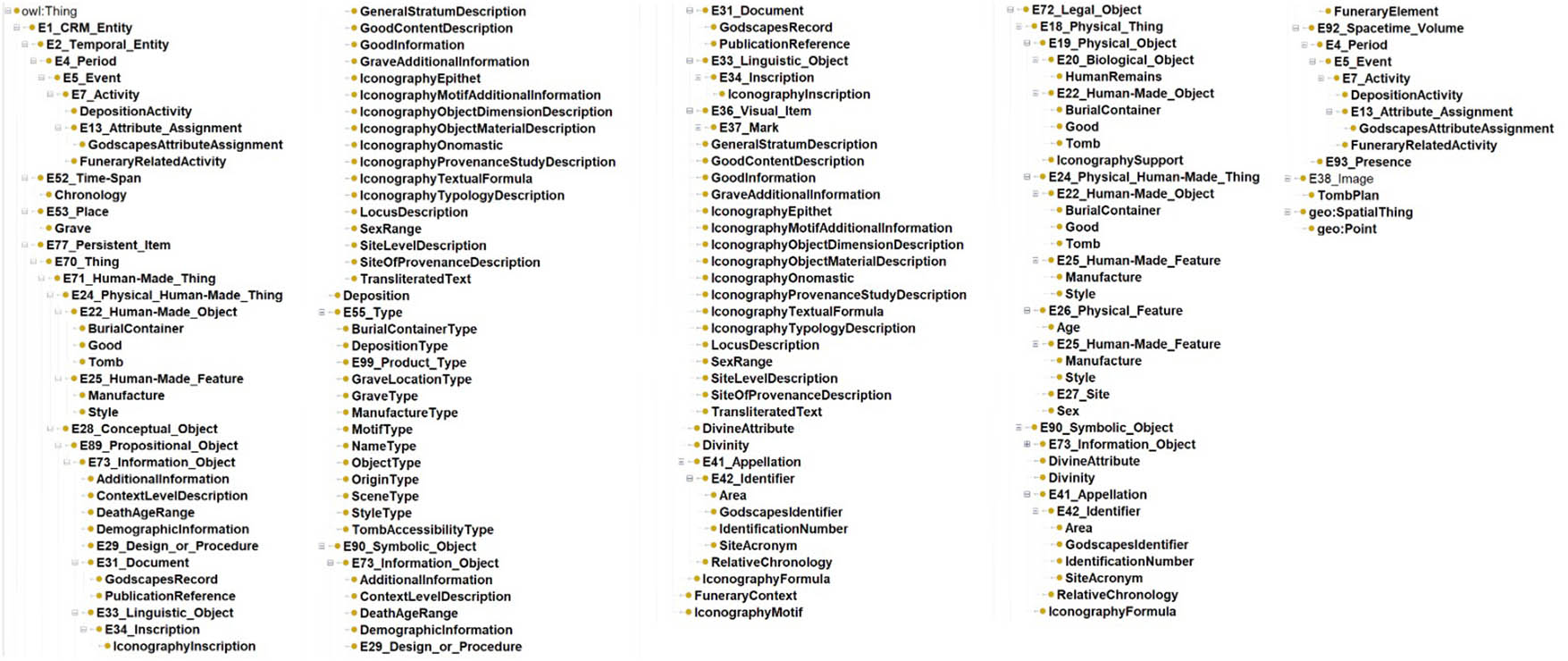

To refine the aforementioned ontologies and to initiate the first phase of testing and validation, the project coupled the survey of literature and open datasets with in-depth review of the evidence from a list of selected pilot sites from the Siro-Palestinian area and the Sinai, namely Ugarit, Byblos, Shechem, Megiddo, Jericho, Lachish, Deir el-Balah, and Serabit el-Khadim (Figure 2). Since the project confronts mainly with legacy data involving different recording standards, description accuracy, and a regional discrepancy of documentation, the preliminary standardization of the metadata for the creation of the Godscapes database and web portal[1] was necessary to define the hierarchy of relevant classes (Figure 3) that will enable effective querying of interconnected knowledge and the evaluation of ritual convergence/divergence across space and time.

Archaeological sites of the second millennium BCE within the Godscapes dataset.

Hierarchy of the defined classes.

TGO is developed according to the guidelines indicated by the CIDOC CRM model in version 7.1.2 (Crofts et al., 2011) and extended by including domain-relevant ontologies. Among the most authoritative, for example, TGO adopts CRMarchaeo, a branch of the CIDOC CRM, “PeriodO” for the temporal extent of chronological phases, and the “Pleiades” for geospatial information. Moreover, the OWL ontology for Godscapes is partially based on previous results and experience accrued in the analysis of architectural types (Cantale et al., 2017a, b, 2021), ancient ceramics (Brancato et al., 2019a, b; Cantone et al., 2015), and epigraphs (Cantone et al., 2019).

5 Modeling and Querying the Godscapes Ontology: Religious Architecture

The research target cannot be achieved using traditional relational databases, which do not support global data and coherent integration mechanisms among different sources of knowledge, and therefore suffer from limited modeling and reasoning capabilities. Moreover, application domains often present interesting implicit information that researchers cannot gather when standard relational databases are adopted, but that can be deduced from the available data if appropriate tools for knowledge representation and reasoning are provided. Sets of rules formalized in the semantic web query language (SPARQL) are thus intended to characterize specific concepts, as well as to answer competency questions. The following section will outline in greater detail a portion of TGO, namely the ontology devoted to the modeling of religious architecture in the Second Millennium BCE Levant, and apply SPARQL queries intended to characterize local, exogenous, and hybrid religious elements, ultimately assessing the potential of the proposed method in mapping and creating domain-specific knowledge.

The OWL ontology describing religious architecture aims to identify the most relevant architectural types present in the area and to determine and formalize the main characteristics of each of them, mainly consisting of the architectural, functional, and ornamental elements that can be found inside and outside the area devoted to cult activity, and the relationships between them. The information regarding the four types of data connected to the religiosity of the Second Millennium BCE Levant is collected and organized through a specific data sheet structured so as to ensure the distinction between objective observations from subjective considerations and measurements. To represent a Godscapes project card, the GodscapesRecord class is defined as a subclass of the CIDOC E31 Document class. According to the CIDOC guidelines, the modeling activity follows an event-oriented approach, in which each relevant element of the domain is associated with an activity of attribution of one or more characteristics (Bruseker et al., 2017). At the core of the model designed to represent the cultic architecture (Figure 4) is the CulticArchitecture class, a sub-class of the CIDOC E53 Place. The model comprehends open-air cult sites, temples, and domestic/palatial chapels, introduced, respectively, by the subclasses OpenAirCulticSite, Temple, and DomesticChapel. For each of the aforementioned sub-classes, TGO specifies references to publication, context location, and the proximity to natural elements (introduced by the DBPedia class NaturalElement) that can emerge as points of reference in the cognitive map of ancient communities, as in the case of the Spring and the Lac Sacré that were at the core of the Gublite religious life, and proximal to the sacred compounds that flourished since the beginning of the Early Bronze Age (Sala, 2015).

The TGO ontology for cultic architecture.

Common to the sub-classes of open-air cult sites, temples, and domestic chapels is also the possibility to describe cardinal orientation (sub-class of CIDOC E55 Physical Feature), location in relation to settlements or, in the case of domestic/palatial chapels, domestic spaces (annexed/sub-floor location), and eventual termination events marking the change of the designated use of the place, or its destruction. In the TGO ontology for the termination event (Figure 5), the change of use is introduced by specific sub-classes of CIDOC E7 Activity, including destruction, either by human hand or by natural causes (both subclasses of E6 Destruction), abandonment, and ritual burial (two subclasses of E81 Transformation).

The TGO ontology for the termination event.

Within the aforementioned classes, a specific typology defines each cultic architecture through the CIDOC class E55 Type, which is meant to comprise terms from controlled vocabularies within the given domain. This is based on the general plan (Figure 6), but also on the individual description of architectural elements and spaces (e.g., entrance type, indoor/outdoor court, antecella, cella, annexed rooms) from the instances within the Godscapes dataset. These elements are described based on type and dimensions, but particular attention is also reserved for the recording of semifixed furniture and foundation/offering/ritual deposits from within these spaces. Although still subject to further expansion and refinement, the modeling of the knowledge domain through a dedicated ontology, currently hosting 25 instances from the Middle to the Late Bronze Age strata of the selected pilot sites, allows the interrogation of the dataset through the formalization of research questions in the Semantic Web query language (SPARQL). A first query identifies the new elements, within the dataset, that concern the general plan of religious architecture, which fall within the generally accepted typologies “langraum migdol” (D’Andrea, 2016), and “temple with indirect entrance and irregular plan” (Mazar, 1992, pp. 177–182). Instances of the “langraum” type within the dataset include the first and second phases of the Migdol Temple of Shechem in the Middle Bronze II–III, the Temple 7300 from the fortification walls of the site, with only one phase in the Middle Bronze III (Campbell, 2002; Wright, 2002), and the Migdol Temple from area bb at Megiddo, dating from the Middle Bronze III to the final Late Bronze (Loud, 1948). Instances of “temple with indirect entrance and irregular plan” refer to the Fosse Temple from Lachish (Tufnell et al., 1940) and to Building 5700 of Shechem (Campbell, 2002; Wright, 2002). The machine therefore correctly identifies these typologies as new additions to previous types which appear fully developed already at the beginning of the Middle Bronze I, namely the cultic precinct with temenos wall (Nigro, 1996; Pinnock, 2009), sometimes characterized by the presence of annexed rooms and standing stones, and the “breitraum” plan type, locally represented from the Early Bronze Age II–III by both the monocellular and the northern Syrian “in antis” type (Castel, 2010; D’Andrea, 2016; Sala, 2008).

The TGO ontology for the temple plan.

With the aim to trace the exogenous influences on such general plans according to their earlier attestation within or outside the study area, a second query excludes the last type, that is regarded as the local development of a Canaanite tradition whose prodromes can be traced back to the Late Bronze I temples of Tel Mevorakh (Stern, 1984, pp. 4–9, 28–39) and Beth Shean (Mullins, 2012, pp. 128–130). Thus, the query rightly defines the most evident exogenous influence on the development of sacred architecture as “Syrian.”

Further planned queries will identify hybrid cults by crossing the information regarding the temple type with decorative elements, and the finds from the identified deposits. Moreover, through a dedicated query counting cultic semi-fixed furniture and deposits, the machine will indicate the main areas devoted to cult within the sacred complexes. The ultimate aim of this query will be the application of the approach proposed by Wightman (2007), which identifies a hierarchy of sacral spaces according to their accessibility, and thus the definition of ritual convergence/divergence through time and space.

6 Approaching Religion Through the Semantic Web: Preliminary Assessment and Future Developments

The Godscapes project proposes to use the technology of the Semantic Web as a tool for defining categories and modeling forms of cultural interactions in the process of framing Second Millennium BCE religiosity in the Eastern Mediterranean. In fact, thanks to the ability to provide information with well-defined meaning, the Semantic Web has the potential to build consistent organic systems of knowledge (or “ontologies”), and to infer implicit information. Indeed, unlike relational databases, given a particular field of knowledge, an ontology can be defined as a mathematical theory that formally defines hierarchies of concepts and the relationships that hold between them.

The ultimate aim of the project is to refine an ontology for each domain following the structure of the Godscapes database, and an ontology for religiosity (TGO), that will form a semantic glue for these ontologies. The first testing of the TGO for religious architecture through SPARQL queries has disclosed the potential of the methodologic approach. However, more efforts will be devoted to avoid subjective interpretations and bias in modeling the archaeological data. TGO, modeled through a top-down approach that considers future integration with other classes of data (funerary data, iconography, and texts), and a bottom-up process taking into account the available archaeological records, has considerable theoretical and descriptive depth. Nevertheless, the use of typologies referring to the archaeological literature, which may overlook the development of single elements beyond general temple plans, may hinder the automated reasoning capabilities of the Semantic Web. This is the case, to mention an example from the Godscapes dataset, of the Acropolis Temple of Lachish (Ussishkin, 2004), which was purposely left out from the above discussion because the attribution to the category of symmetrical temples (langraum migdol) or to an instance of “temple with indirect entrance and irregular plan” largely depends on the unknown positioning of the temple’s entrance (for further insights on the question, see Mazar, 1992, pp. 173–177; Ussishkin, 2004, pp. 216–221; Weissbein et al., 2019; Yannai 1996, pp. 171–172; 176). The Gublite sacred architecture will also need a specific description that goes beyond the labels so far considered to render its distinctive traits of originality and local reinterpretation. For this reason, a further refinement of TGO for religious architecture will require the modeling of more ontologies describing each plan type. In fact, this step will aid effective querying concerning the development of single components of the cultic architecture, such as the entrance type, the structure of the temple cella with the eventual adyton, or the adjunction of non-canonic spaces to the general plan, such as subsidiary rooms. Moreover, we believe that such well-refined ontologies, when collecting more information from the web of data, will suggest further elements of comparison, and missing inherent knowledge.

A permanent link to the ontology will be available through the Godscapes platform, and the resulting datasets will publicly be available in open format to simplify the integration with ontologies for different domains and to extend the modeled knowledge. As a last step, the project will formalize sets of rules in the Semantic Web Rule Language to characterize specific concepts such as the one of “religious elements” (i.e., “exogenous religious element” and/or “indigenous religious element”), as well as to answer research questions such as, for example: how exogenous elements transformed autochthones forms of religiosity? Which are those religious elements that persist and those that are abandoned in Levantine traditions? To query and visualize data in a human-friendly style, the knowledge base so constructed will be accessed by means of an adequate web platform, an SPARQL endpoint, and a WebGIS interface.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the Italian Ministry for University and Research and the project STORAGE (University of Catania, program PIA.CE.RI.) for funding the project “Godscapes: Modeling Second Millennium BCE Polytheisms in the Eastern Mediterranean.” They are also grateful for the reviewer’s valuable comments that improved the manuscript.

-

Funding information: The project is funded by the Italian Ministry of Research (PRIN 2020) – Project 20204N3WCX – led by the University of Catania and directed by Nicola Laneri, and by the STORAGE project of the University of Catania. The other three units involved in the project are the University of Rome ‘La Sapienza’ (Lorenzo Nigro), the University of Pisa (Gianluca Miniaci) and the CNR (Ida Oggiano).

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission. NL is the PI of the Godscapes project and the corresponding author of the manuscript. Together with LN and GM, he has developed the theoretical foundations and reviewed the relevant literature. MNA and DFS have applied the Semantic Web methodologies to design the TGO ontologies and write the SPARQL queries. CP has curated the Godscapes archaeological dataset together with the conceptual model of TGO and revised the query results.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The Godscapes dataset and the SPARQL queries generated during this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Ahrens, A. (2020). Aegyptiaca in der nördlichen Levante. Eine Studie zur Kontextualisierung und Rezeption ägyptischer und ägyptisierender Objekte in der Bronzezeit. Peeters.10.2307/j.ctv1q26phgSearch in Google Scholar

Aruz, J., Benzel, K., & Evans J. M. (Eds.). (2009). Beyond Babylon: Art, trade, and diplomacy in the second millennium B.C. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Yale University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Assman, J. (1998). Moses der Ägypter: Entzifferung einer Gedächtnisspur. Hanser.Search in Google Scholar

Assmann, J. (2014). From Akhenaten to Moses: Ancient Egypt and religious change. American University in Cairo Press.10.5743/cairo/9789774166310.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Beckman, G., & Lewis, T. J. (Eds.). (2006). Text, artifact, and image: Revealing ancient Israelite religion. Brown Judaic Studies.Search in Google Scholar

Ben-Tor, D. (2007). Scarabs, chronology and interconnections. Egypt and Palestine in the Second Intermediate Period. Academic Press, Fribourg, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.Search in Google Scholar

Berners-Lee, T, Hendler, J., & Lassila, O. (2001). The semantic web. Scientific American, 284(5), 34–43.10.1038/scientificamerican0501-34Search in Google Scholar

Bietak, M., Matthiae, P., & Prell., S. (Eds.). (2019). Ancient Egyptian and Ancient Near Eastern palaces (Vol. II). Harrassowitz Verlag.10.13173/9783447111836Search in Google Scholar

Bietak, M., & Prell, S. (Eds.). (2019). The Enigma of the Hyksos (Vol. I), ASOR Conference Boston 2017 - ICAANE Conference Munich 2018 Collected Papers. Harrassowitz Verlag.Search in Google Scholar

Bonfil, R., & Zarzecki-Peleg, A. (2007). The palace in the upper city of Hazor as an expression of a Syrian architectural paradigm. Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research, 348, 25–47.10.1086/BASOR25067036Search in Google Scholar

Brancato, R., Nicolosi-Asmundo, N., Pagano G., Santamaria, D. F., & Ucchino, S. (2019a). An ontology for legacy data on ancient ceramics of the plain of Catania. Proceedings of the 34th Italian Conference on Computational Logic, CILC 2019, Trieste 19 June, 2019, CEUR Workshop Proceedings (Vol. 2396, pp. 59–67).Search in Google Scholar

Brancato, R., Nicolosi-Asmundo, N., Pagano G., Santamaria, D. F. & Ucchino, S. (2019b). Towards an ontology for investigating on archaeological Sicilian landscapes. Proceedings of the 1st International Workshop on Open Data and Ontologies for Cultural Heritage (ODOCH 2019), Rome, 3 June 2019, CEUR Workshop Proceedings (Vol. 2375, pp. 85–90).Search in Google Scholar

Bruseker, B., Carboni, N., & Guillem, A. (2017). Cultural heritage data management: The role of formal ontology and CIDOC CRM. In M. L. Vincent, V. M. L´opez-Menchero Bendicho, M. Ioannides, & T. E. Levy (Eds.), Heritage and archaeology in the digital age: Acquisition, curation, and dissemination of spatial cultural heritage data (pp. 93–131). Springer.10.1007/978-3-319-65370-9_6Search in Google Scholar

Bunimovitz, S. (2019). Canaan is your land and its kings are your servants-conceptualizing the Late Bronze Age Egyptian Government in the Southern Levant. In A. Yasur-Landau, E. H. Cline, & Y. M. Rowan (Eds.), The social archaeology of the levant from prehistory to the present (pp. 265–280). Cambridge University Press.10.1017/9781316661468.016Search in Google Scholar

Burke, A. A. (2010). Canaan under Siege. The History and Archaeology of Egypt’s War in Canaan during the Early Eighteenth Dynasty. In J. Vidal (Ed.), Studies on War in the Ancient Near East. Collected Essays on Military History (pp. 43–66). Ugarit-Verlag.Search in Google Scholar

Burke, A. A. (2020). The Amorites and the Bronze Age Near East. Cambridge University Press.10.1017/9781108856461Search in Google Scholar

Burke, A. A., Peilstöcker, M., Karoll, A., Pierce, G. A., Kowalski, K., Ben-Marzouk, N., Damm, J. C., Danielson, A. J., Fessler, H. D., & Kaufman, B. (2017). Excavations of the New Kingdom Fortress in Jaffa, 2011–2014: Traces of Resistance to Egyptian Rule in Canaan. American Journal of Archaeology, 121(1), 85–133.10.3764/aja.121.1.0085Search in Google Scholar

Campbell, E. F. (2002). The stratigraphy and architecture of Shechem/Tell Balatah, 1. American Schools of Oriental Research.Search in Google Scholar

Cantale, C., Cantone, D., Lupica Rinato, M., Nicolosi-Asmundo, M. & Santamaria, D. F. (2017a). The shape of a Benedictine monastery: The SaintGall ontology. In Proceedings of the Joint Ontology Workshops Episode 3: The Tyrolean Autumn of Ontology (JOWO 2017), Bozen-Bolzano, 21-23 September 2017, CEUR Workshop Proceedings (Vol. 2050, pp. 1–6).Search in Google Scholar

Cantale, C., Cantone, D., Nicolosi-Asmundo, M., & Santamaria, D. F. (2017b). Distant reading through ontologies. Italian Journal of Library, Archives, and Information Science, 8(3), 203–219. doi: 10.4403/jlis.it-12342.Search in Google Scholar

Cantale, C., Cantone, D., Lupica Rinato, M., Nicolosi-Asmundo, M., Santamaria, D. F., & Stufano Melone, M. R. (2021). The ideal Benedictine Monastery: From the Saint Gall map to ontologies. Applied Ontologies, 16(2), 137–160. doi: 10.3233/AO-210248.Search in Google Scholar

Cantone, D., Nicolosi-Asmundo, M., Santamaria, D. F., Cristofaro, S., Spampinato, D., & Prado, F. (2019). An EPIDOC ontological perspective: The epigraphs of the Castello Ursino Civic museum of Catania via CIDOC CRM. Archeologia e Calcolatori, 30, 139–157. doi: 10.19282/ac.30.2019.10.Search in Google Scholar

Cantone, D., Nicolosi-Asmundo, M., Santamaria, D. F., & Trapani, F. (2015). Ontoceramic: An OWL ontology for ceramics classification. In Proceedings of the 30th Italian Conference on Computational Logic (CILC 2015), Genova, 1–3 July, 2015, CEUR Workshop Proceedings (Vol. 1459, pp. 122–127).Search in Google Scholar

Castel, C. (2010). The first temples in antis: The sanctuary of tell Al-Rawda in the context of 3rd millennium Syria. Kulturlandschaft Syrien, Zentrum und Peripherie, Festschrift für Jan-Waalke Meyer, 371, 123–164.Search in Google Scholar

Cohen, S. L., & Adams, M. J. (Eds.). (2019). Movement and Mobility between Egypt and the Southern Levant in the Second Millennium BCE. [Special issue]. Journal of Ancient Egyptian Interconnections, 21.Search in Google Scholar

Crofts, N., Doerr, M., Gill, T., Stead, S., & Stiff, M. (2011). Definition of the CIDOC conceptual reference model version 5.0.4. Technical report. ICOM/CIDOC CRM Special Interest Group, 11. https://cidoc-crm.org//html/5.0.4/cidoc-crm.html.Search in Google Scholar

D’Andrea, M. (2014). The Southern Levant in Early Bronze IV: Issues and perspectives in the pottery evidence (Vol. 2). ‘Sapienza’ University Press.Search in Google Scholar

D’Andrea, M. (2016). I luoghi di culto del Levante meridionale all’inizio del Bronzo Medio. Caratteri locali, sviluppi autonomi e rapporti con il Levante settentrionale. In P. Matthiae (Ed.), Atti dei Convegni Lincei (Vol. 304, pp. 179–221). Bardi Edizioni.Search in Google Scholar

Engelke, M. (2012). Material religion. In R. Orsi (Ed.), The Cambridge companion to religious studies (pp. 209–229). Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CCOL9780521883917.012Search in Google Scholar

Feldman, M. H. (2006). Diplomacy by design: Luxury arts and an ‘international style’ in the ancient Near East, 1400–1200 BCE. University of Chicago Press.Search in Google Scholar

Hawkes, C. (1954). Wenner-gren foundation supper conference: Archeological theory and method: Some suggestions from the old world. American Anthropologist, 56(2), 155–168.10.1525/aa.1954.56.2.02a00660Search in Google Scholar

Helck, W. (1971). Die Beziehungen Ägyptens zu Vorderasien im 3. und 2. Jahrtausend v. Chr. Harrassowitz Verlag.Search in Google Scholar

Hodder, I. (2011). Human-thing entanglement: Towards an integrated archaeological perspective. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 17, 154–177.10.1111/j.1467-9655.2010.01674.xSearch in Google Scholar

Hodder, I. (2012). Entangled: An archaeology of the relationships between humans and things. Wiley-Blackwell.10.1002/9781118241912Search in Google Scholar

Höflmayer, F. (2015). Egypt´s ‘Empire’ in the Southern Levant during the Early 18th Dynasty. In B. Eder & R. Pruzsinszky (Eds.), Policies of Exchange. Political Systems and Modes of Interaction in the Aegean and the Near East in the 2nd Millennium B.C.E. Proceedings of the International Symposium at the University of Freiburg, Institute for Archaeological Studies, 30 May - 2 June, 2012 (pp. 191–206). Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften.10.51679/ophiussa.2018.42Search in Google Scholar

Homsher, R., & Cradic, M. (2018). The Amorite Problem. Resolving an historical dilemma. Levant, 49, 259–283.10.1080/00758914.2017.1418038Search in Google Scholar

Johnson, P. J. (2016). Syncretism and hybridization. In M. Stausberg & S. Engler (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of the study of religion (pp. 754–774). Oxford University Press.10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198729570.013.50Search in Google Scholar

Kemp, B. (2012). The City of Akhenaten and Nefertiti: Amarna and its people. Thames & Hudson.Search in Google Scholar

Killebrew, A. E. (2005). Biblical Peoples and Ethnicity: An Archaeological Study of Egyptians, Canaanites, Philistines, and Early Israel, 1300-1100 B.C.E. Society of Biblical Literature.Search in Google Scholar

Koch, I. (2019). Religion at Lachish under Egyptian Colonialism. Die Welt des Orients, 49, 161–182.10.13109/wdor.2019.49.2.161Search in Google Scholar

Laneri, N. (2011). Connecting fragments of a materialized belief: A small-sized ceremonial settlement in rural northern Mesopotamia at the beginning of the Second Millennium BC. Cambridge Archaeological Journal, 21(1), 77–94.10.1017/S0959774311000059Search in Google Scholar

Laneri, N. (Ed.). (2015). Defining the sacred: Approaches to the archaeology of religion in the Near East. Oxbow Books.Search in Google Scholar

Laneri, N. (2023). Introduction to the Bloomsbury handbook of material religion in the Ancient Near east and Egypt. In N. Laneri & S. R. Steadman (Eds.), The Bloomsbury handbook of material religion in the Ancient Near East and Egypt. Bloomsbury Publishing.Search in Google Scholar

Laneri, N. (2024). From Ritual to God in the Ancient Near East. Tracing the Origins of Religion. Cambridge University Press.10.1017/9781009306621Search in Google Scholar

Laneri, N., & Pappalardo, C. (2024). Patterns of Religiosity in the Levant and Egypt during the Second Millennium BCE: The Case of the Anthropoid Clay Coffins. In G. Miniaci, C. Greco, P. Dele Vesco, M. Mancini & C. Alù (Eds.), Ancient Egypt and the Surrounding World: Contact, Trade, and Influence (pp. 57–70). Pisa University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Laneri, N., & Steadman, S. R. (Eds.). (2023). The Bloomsbury handbook of material religion in the Ancient Near East and Egypt. Bloomsbury Publishing.10.5040/9781350280847Search in Google Scholar

Latour, B. (2005). Reassembling the social. An introduction to actor-network-theory. Oxford University Press.10.1093/oso/9780199256044.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Liverani, M. (1987). The collapse of the Near Eastern regional system at the end of the Bronze Age: The case of Syria. In M. J. Rowlands, M. T. Larsen, & K. Kristiansen (Eds.), Centre and periphery in the ancient world (pp. 66–73). Cambridge University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Loud, G. (1948). Megiddo II. Seasons of 1935-39. OIP 62. University of Chicago Press.Search in Google Scholar

Matthiae, P., Pinnock, F., Nigro, L., & Peyronel, L. (Eds.). (2007). Proceedings of the International Colloquium. From Relative Chronology to Absolute Chronology: The Second Millennium BC in Syria-Palestine (Rome, 29th November – 1st December 2001), Contributi del Centro Lincei Interdisciplinare “Beniamino Segre”, 117. Bardi.Search in Google Scholar

Mazar, A. (1992). Temples of the Middle and Late Bronze Ages and the Iron Age. In A. Kempinski & R. Reich (Eds.), The architecture of ancient Israel (pp. 161–189). The Israel Exploration Society.Search in Google Scholar

Miniaci, G. (2018). Deposit f (nos. 15121-15567) in the Obelisk Temple at Byblos: Artefact mobility in the middle Bronze Age I-II (1850-1650 BC) between Egypt and the Levant. Ägypten und Levante, 28, 379–408.10.1553/AEundL28s379Search in Google Scholar

Miniaci, G. (2019). The material entanglement in the ‘Egyptian Cemetery’ in Kerma (Sudan, 1750-1500 BC): Appropriation, incorporation, tinkering, and hybridisation. Egitto e Vicino Oriente, XLII, 13–32.10.12871/97888333934212Search in Google Scholar

Miniaci, G. (2020). At the dawn of the Late Bronze Age ‘globalization’: The (re)-circulation of Egyptian artefacts in Nubia and the northern Levant in the MB II-mid MB III (c. 1710–1550 BC). Claroscuro, 19(2), 1–26.10.35305/cl.vi19.46Search in Google Scholar

Miniaci, G., & Saler, C. (2021). The sheet metal figurines from Byblos: Evidence for an Egyptian import and adaptation. Ägypten und Levante, 31, 339–355.10.1553/AEundL31s339Search in Google Scholar

Montanari, D. (2020). Metal weapons and social differentiation at Bronze Age Tell es-Sultan. In R. T. Sparks, B. Finlayson, B. Wagemakers, & J. M. Briffa (Eds.), Digging Up Jericho. Past, present and future (pp. 115–127). Archaeopress.10.2307/j.ctvwh8bss.12Search in Google Scholar

Morandi Bonacossi, D. (2014). The Northern Levant (Syria) during the Middle Bronze Age. In A. E. Killebrew & M. Steiner (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of the archaeology of the Levant (c. 8000–332 BCE) (pp. 408–427). Oxford University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Morgan, D. (2016). Materiality. In M. Stausberg & S. Engler (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of the study of religion (pp. 271–289). Oxford University Press.10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198729570.013.19Search in Google Scholar

Mourad, A. L. (2015). Rise of the Hyksos: Egypt and the Levant from the Middle Kingdom to the early Second Intermediate Period. Archaeopress.10.2307/j.ctvr43jbkSearch in Google Scholar

Mullins, R. A. (2012). The late bronze and iron age temples at Beth Shean. In J. Kamlah (Ed.), Temple building and temple cult architecture and cultic paraphernalia of temples in the Levant (2. - 1. Mill. B.C.E.); Proceedings of a Conference on the Occasion of the 50th Anniversary of the Institute of Biblical Archaeology at the University of Tübingen (28–30 May 2010) (pp. 127–157). Harrassowitz Verlag.Search in Google Scholar

Nigro, L. (1996). Santuario e pellegrinaggio nella Palestina dell’Età del Bronzo Medio (2000-1600 aC): recenti scoperte sulle aree di culto aperte e gli «alti luoghi» dei Cananei. In L. Andreatta, F. Marinelli, F. Arinze, & Ioannes Paulus (Eds.), Santuario, tenda dell’incontro con Dio: tra storia e spiritualità (pp. 216–229). Piemme.Search in Google Scholar

Nigro, L. (2018). Hotepibra at Jericho. Interconnections between Egypt and Syria-Palestine during the 13th dynasty. In A. Vacca, S. Pizzimenti, & M. G. Micale (Eds.), A Oriente del Delta: Scritti sull’Egitto ed il Vicino Oriente antico in onore di Gabriella Scandone Matthiae, Contributi e Materiali di Archeologia Orientale XVIII (pp. 437–446). Scienze e Lettere.Search in Google Scholar

Oggiano, I. (2005). Dal terreno al divino. Archeologia del culto nella Palestina del primo millennio. Carocci.Search in Google Scholar

Pfälzner, P., & Al Maqdisī, M. (2015). Qaṭna and the Networks of Bronze Age Globalism. Proceedings of an International Conference in Stuttgart and Tübingen in October 2009 (Vol. 2). Harrassowitz Verlag.Search in Google Scholar

Pfoh, E. (2016). Syria-Palestine in the Late Bronze Age. An anthropology of politics and power. Routledge.10.4324/9781315678818Search in Google Scholar

Pinnock, F. (2009). Open cults and temples in Syria and the Levant. In C. Doumet-Serhal (Ed.), Interconnections in the Eastern Mediterranean. Lebanon in the Bronze and Iron Ages. Proceedings of the International Symposium Beirut 2008. Bulletin d’Archéologie e d’Architecture Libanaise, Hors Série VI (pp. 195–207). Ministere de la culture, Direction generale des antiquites.Search in Google Scholar

Rainey, A. F. (2014). The El-Amarna Correspondence: A New Edition of the Cuneiform Letters from the Site of El-Amarna based on Collations of all Extant Tablets (2 vols.). Brill.10.1163/9789004281547Search in Google Scholar

Sala, M. (2008). L’architettura sacra della Palestina nell’età del bronzo antico I-III: contesto archeologico, analisi architettonica e sviluppo storico. Contributi e materiali di archeologia orientale XIII. Università degli studi di Roma La Sapienza.Search in Google Scholar

Sala, M. (2015). Early and Middle Bronze Age Temples at Byblos: Specificity and Levantine Interconnections. BAAL Hors-Série, 10, 31–58.Search in Google Scholar

Schulz, S., & Jansen, L. (2018). Towards an ontology of religious and spiritual belief. In S. Borgo, P. Hitzler, & O. Kutz (Eds.), Formal Ontology in Information Systems. Proceedings of the 10th International Conference (FOIS 2018) (pp. 253–260). IOS Press.10.3233/978-1-61499-910-2-253Search in Google Scholar

Smith, M. S. (2001). The origins of biblical monotheism: Israel’s polytheistic background and the Ugaritic Texts. Oxford University Press.10.1093/019513480X.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Stern, E. (1984). Excavations at Tel Mevorakh (1973-1976), Part 2: The Bronze Age. Qedem 18. Institute of Archaeology, Hebrew University of Jerusalem.Search in Google Scholar

Stockhammer, P. W. (2012). Conceptualizing cultural hybridization in archaeology. In P. W. Stockhammer (Ed.), Conceptualizing cultural hybridization: A transdisciplinary approach (pp. 43–58). Springer.10.1007/978-3-642-21846-0_4Search in Google Scholar

Stockhammer, P. W. (2013). From hybridity to entanglement, from essentialism to practice, Archaeological Review from Cambridge, 28, 11–28.Search in Google Scholar

Tufnell, O., Ince, C. H., & Harding, G. L. (1940). Lachisch II (Tell ed-Duweir). The Fosse Temple. Oxford University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Ussishkin, D. (2004). Area P: The Level VI Temple. In D. David Ussishkin (Ed.), The Renewed Archaeological Excavations at Lachish (1973–1994), Volume I (pp. 215–281). Emery and Clair Yass Publications in Archaeology.Search in Google Scholar

Weinstein, J. M. (1981). The Egyptian empire in Palestine: A reassessment. Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research, 241(1), 1–28.10.2307/1356708Search in Google Scholar

Weissbein, I., Garfinkel, Y., Hasel, M. G., Klingbeil, M. G., Brandl, B., & Misgav, H. (2019). The Level VI north-east temple at Tel Lachish. Levant, 51(1), 76–104.10.1080/00758914.2019.1695093Search in Google Scholar

Wightman, G. J. (2007). Sacred spaces: Religious architecture in the ancient world. Peeters.Search in Google Scholar

Wright, G. R. H. (2002). The stratigraphy and architecture of Shechem/Tell Balatah 2: The plans. American Schools of Oriental Research.Search in Google Scholar

Yannai, E. (1996). Aspects of Material Culture of Canaan during the Egyptian 20th Dynasty, (1130–1200 BCE). [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv, Israel. (in Hebrew).10.1179/033443596788138675Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Etched in Stone: The Kevermes Stone Stela From the Great Hungarian Plain

- Waste Around Longhouses: Taphonomy on LBK Settlement in Hlízov

- Raw Materials and Technological Choices: Case Study of Neolithic Black Pottery From the Middle Yangtze River Valley of China

- Disentangling Technological Traditions: Comparative Analysis of Chaînes Opératoires of Painted Pre-Hispanic Ceramics From Nariño, Colombia

- Ancestral Connections: Re-Evaluating Concepts of Superimpositioning and Vandalism in Rock Art Studies

- Disability and Care in Late Medieval Lund, Sweden: An Analysis of Trauma and Intersecting Identities, Aided by Photogrammetric Digitization and Visualization

- Assessing the Development in Open Access Publishing in Archaeology: A Case Study From Norway

- Decorated Standing Stones – The Hagbards Galge Monument in Southwest Sweden

- Geophysical Prospection of the South-Western Quarter of the Hellenistic Capital Artaxata in the Ararat Plain (Lusarat, Ararat Province, Armenia): The South-West Quarter, City Walls and an Early Christian Church

- Lessons From Ceramic Petrography: A Case of Technological Transfer During the Transition From Late to Inca Periods in Northwestern Argentina, Southern Andes

- An Experimental and Methodological Approach of Plant Fibres in Dental Calculus: The Case Study of the Early Neolithic Site of Cova del Pasteral (Girona, Spain)

- Bridging the Post-Excavation Gaps: Structured Guidance and Training for Post-Excavation in Archaeology

- Everyone Has to Start Somewhere: Democratisation of Digital Documentation and Visualisation in 3D

- The Bedrock of Rock Art: The Significance of Quartz Arenite as a Canvas for Rock Art in Central Sweden

- The Origin, Development and Decline of Lengyel Culture Figurative Finds

- New “Balkan Fashion” Developing Through the Neolithization Process: The Ceramic Annulets of Amzabegovo and Svinjarička Čuka

- From a Medieval Town to the Modern Fortress of Rosas (Girona-Spain). Combining Geophysics and Archaeological Excavation to Understand the Evolution of a Strategic Coastal Settlement

- Technical Transfers Between Chert Knappers: Investigating Gunflint Manufacture in the Eastern Egyptian Desert (Wadi Sannur, Northern Galala, Egypt)

- Early Neolithic Pottery Production in the Maltese Islands: Initiating a Għar Dalam and Skorba Pottery Fabric Classification

- Revealing the Origins: An Interdisciplinary Study Into the Provenance of Sacral Microarchitecture–The Unique Case of the Church Model From Žatec in Bohemia

- An Analogical and Analytical Approach to the Burçevi Monumental Tomb

- A Glimpse at Raw Material Economy and Production of Chipped Stones at the Neolithic (Starčevo) Site of Svinjarička Čuka, South Serbia

- Archaeological Lithotheques of Siliceous Rocks in Spain: First Diagnosis of the Lithotheque Thematic Network

- Mapping Changes in Settlement Number and Demography in the South of Israel from the Hellenistic to the Early Islamic Period

- Review Article

- Structural Measures Against the Risks of Flash Floods in Patara and Consequent Considerations Regarding the Location of the Oracle Sanctuary of Apollo

- Commentary Article

- A Framework for Archaeological Involvement with Human Genetic Data for European Prehistory

- Special Issue on Digital Religioscapes: Current Methodologies and Novelties in the Analysis of Sacr(aliz)ed Spaces, edited by Anaïs Lamesa, Asuman Lätzer-Lasar - Part II

- Goats and Goddesses. Digital Approach to the Religioscapes of Atargatis and Allat

- Conceiving Elements of Divinity: The Use of the Semantic Web for the Definition of Material Religiosity in the Levant During the Second Millennium BCE

- Deep Mapping the Asklepieion of Pergamon: Charting the Path Through Challenges, Choices, and Solutions

- Special Issue on Engaging the Public, Heritage and Educators through Material Culture Research, edited by Katherine Anne Wilson, Christina Antenhofer, & Thomas Pickles

- Inventories as Keys to Exploring Castles as Cultural Heritage

- Hohensalzburg Digital: Engaging the Public via a Local Time Machine Project

- Monastic Estates in the Wachau Region: Nodes of Exchange in Past and Present Days

- “Meitheal Adhmadóireachta” Exploring and Communicating Prehistoric Irish Woodcraft Through Remaking and Shared Experience

- Community, Public Archaeology, and Co-construction of Knowledge Through the Educational Project of a Rural Mountain School

- Valuing Material Cultural Heritage: Engaging Audience(s) Through Development-Led Archaeological Research

- Engaging the Public Through Prehistory: Experiences From an Inclusive Perspective

- Material Culture, the Public, and the Extraordinary – “Unloved” Museums Objects as the Tool to Fascinate

- Archaeologists on Social Media and Its Benefits for the Profession. The Results and Lessons Learnt from a Questionnaire

- Special Issue on Network Perspectives in the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East and Eastern Mediterranean, edited by Maria Gabriella Micale, Helen Dawson, & Antti A. Lahelma

- Networks of Pots: The Usage of Ceramics in Network Analysis in Mediterranean Archaeology

- Networks of Knowledge, Materials, and Practice in the Neolithic Zagros

- Weak Ties on Old Roads: Inscribed Stopping-Places and Complex Networks in the Eastern Desert of Graeco-Roman Egypt

- Mediterranean Trade Networks and the Diffusion and Syncretism of Art and Architecture Styles at Delos

- People and Things on the Move: Tracking Paths With Social Network Analysis

- Networks and the City: A Network Perspective on Procopius De Aed. I and the Building of Late Antique Constantinople

- Network Perspectives in the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East and Eastern Mediterranean

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Etched in Stone: The Kevermes Stone Stela From the Great Hungarian Plain

- Waste Around Longhouses: Taphonomy on LBK Settlement in Hlízov

- Raw Materials and Technological Choices: Case Study of Neolithic Black Pottery From the Middle Yangtze River Valley of China

- Disentangling Technological Traditions: Comparative Analysis of Chaînes Opératoires of Painted Pre-Hispanic Ceramics From Nariño, Colombia

- Ancestral Connections: Re-Evaluating Concepts of Superimpositioning and Vandalism in Rock Art Studies

- Disability and Care in Late Medieval Lund, Sweden: An Analysis of Trauma and Intersecting Identities, Aided by Photogrammetric Digitization and Visualization

- Assessing the Development in Open Access Publishing in Archaeology: A Case Study From Norway

- Decorated Standing Stones – The Hagbards Galge Monument in Southwest Sweden

- Geophysical Prospection of the South-Western Quarter of the Hellenistic Capital Artaxata in the Ararat Plain (Lusarat, Ararat Province, Armenia): The South-West Quarter, City Walls and an Early Christian Church

- Lessons From Ceramic Petrography: A Case of Technological Transfer During the Transition From Late to Inca Periods in Northwestern Argentina, Southern Andes

- An Experimental and Methodological Approach of Plant Fibres in Dental Calculus: The Case Study of the Early Neolithic Site of Cova del Pasteral (Girona, Spain)

- Bridging the Post-Excavation Gaps: Structured Guidance and Training for Post-Excavation in Archaeology

- Everyone Has to Start Somewhere: Democratisation of Digital Documentation and Visualisation in 3D

- The Bedrock of Rock Art: The Significance of Quartz Arenite as a Canvas for Rock Art in Central Sweden

- The Origin, Development and Decline of Lengyel Culture Figurative Finds

- New “Balkan Fashion” Developing Through the Neolithization Process: The Ceramic Annulets of Amzabegovo and Svinjarička Čuka

- From a Medieval Town to the Modern Fortress of Rosas (Girona-Spain). Combining Geophysics and Archaeological Excavation to Understand the Evolution of a Strategic Coastal Settlement

- Technical Transfers Between Chert Knappers: Investigating Gunflint Manufacture in the Eastern Egyptian Desert (Wadi Sannur, Northern Galala, Egypt)

- Early Neolithic Pottery Production in the Maltese Islands: Initiating a Għar Dalam and Skorba Pottery Fabric Classification

- Revealing the Origins: An Interdisciplinary Study Into the Provenance of Sacral Microarchitecture–The Unique Case of the Church Model From Žatec in Bohemia

- An Analogical and Analytical Approach to the Burçevi Monumental Tomb

- A Glimpse at Raw Material Economy and Production of Chipped Stones at the Neolithic (Starčevo) Site of Svinjarička Čuka, South Serbia

- Archaeological Lithotheques of Siliceous Rocks in Spain: First Diagnosis of the Lithotheque Thematic Network

- Mapping Changes in Settlement Number and Demography in the South of Israel from the Hellenistic to the Early Islamic Period

- Review Article

- Structural Measures Against the Risks of Flash Floods in Patara and Consequent Considerations Regarding the Location of the Oracle Sanctuary of Apollo

- Commentary Article

- A Framework for Archaeological Involvement with Human Genetic Data for European Prehistory

- Special Issue on Digital Religioscapes: Current Methodologies and Novelties in the Analysis of Sacr(aliz)ed Spaces, edited by Anaïs Lamesa, Asuman Lätzer-Lasar - Part II

- Goats and Goddesses. Digital Approach to the Religioscapes of Atargatis and Allat

- Conceiving Elements of Divinity: The Use of the Semantic Web for the Definition of Material Religiosity in the Levant During the Second Millennium BCE

- Deep Mapping the Asklepieion of Pergamon: Charting the Path Through Challenges, Choices, and Solutions

- Special Issue on Engaging the Public, Heritage and Educators through Material Culture Research, edited by Katherine Anne Wilson, Christina Antenhofer, & Thomas Pickles

- Inventories as Keys to Exploring Castles as Cultural Heritage

- Hohensalzburg Digital: Engaging the Public via a Local Time Machine Project

- Monastic Estates in the Wachau Region: Nodes of Exchange in Past and Present Days

- “Meitheal Adhmadóireachta” Exploring and Communicating Prehistoric Irish Woodcraft Through Remaking and Shared Experience

- Community, Public Archaeology, and Co-construction of Knowledge Through the Educational Project of a Rural Mountain School

- Valuing Material Cultural Heritage: Engaging Audience(s) Through Development-Led Archaeological Research

- Engaging the Public Through Prehistory: Experiences From an Inclusive Perspective

- Material Culture, the Public, and the Extraordinary – “Unloved” Museums Objects as the Tool to Fascinate

- Archaeologists on Social Media and Its Benefits for the Profession. The Results and Lessons Learnt from a Questionnaire

- Special Issue on Network Perspectives in the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East and Eastern Mediterranean, edited by Maria Gabriella Micale, Helen Dawson, & Antti A. Lahelma

- Networks of Pots: The Usage of Ceramics in Network Analysis in Mediterranean Archaeology

- Networks of Knowledge, Materials, and Practice in the Neolithic Zagros

- Weak Ties on Old Roads: Inscribed Stopping-Places and Complex Networks in the Eastern Desert of Graeco-Roman Egypt

- Mediterranean Trade Networks and the Diffusion and Syncretism of Art and Architecture Styles at Delos

- People and Things on the Move: Tracking Paths With Social Network Analysis

- Networks and the City: A Network Perspective on Procopius De Aed. I and the Building of Late Antique Constantinople

- Network Perspectives in the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East and Eastern Mediterranean