Abstract

This article argues that the landscape attributes of a network are an influential factor in the network’s formation and function. By this, we mean that the realities of terrain and environment affect both physical and social networks in ways that can be productively incorporated into network analyses. Using two case studies from the sites of Buweib and the Paneion of the Wadi Minayh in the Eastern Desert of Egypt, we illustrate how landscape performs as an actor in the networks of the Graeco-Roman period, influencing the location of network “weak-tie” nodes and functioning as a medium of communication that, through practices of landscape marking, allows information to be exchanged between travelers, across language and cultural barriers, and even across millennia. These inscribed stopping places act as vibrant spaces of exchange in the desert by exercising an influence on how people interact physically and conceptually with the landscape.

1 Introduction

This article argues that the landscape attributes of a network are an influential factor in the network’s formation and function. By this, we mean that the realities of terrain and environment affect both physical and social networks in ways that can be productively incorporated into network analyses. The case studies below illustrate how landscape performs as an actor in the networks of the Eastern Desert of Egypt, influencing the location of network nodes and functioning as a medium of communication that, through practices of landscape marking, allows information to be exchanged between travelers, across language and cultural barriers, and even across millennia.

The analysis relies on four intersecting datasets: a comprehensive, spatialized catalog of the archaeological sites in the Eastern Desert occupied from the New Kingdom to the end of the Roman period, a library of the epigraphic evidence from these sites, a model of potential paths of movement through the region, and a high resolution, dynamic model of several environmental factors. All datasets were created or compiled by the CNRS ERC Desert Networks Project (ERC-2017-STG, Proposal number 759078). This project, under the direction of Dr. Bérangère Redon, was concerned with the gathering of archaeological, epigraphic, historical, and spatial information about hundreds of archaeological sites and routes in the Eastern Desert of Egypt.

Using this compiled information, the Desert Networks Project has modeled the flow of people, goods, and information across and within the Eastern Desert of Egypt. Working from the location of archaeological sites and a calculation of the paths across the landscape that are most traversable by pack animals (in this case, camels) the project has previously identified a dense network of potential paths that connect places to one another (Crépy et al., 2023; Manière et al., 2020, 2021). While large sites such as road stations and desert fortresses served as network hubs due to the opportunities they made for rest, news, water, and trade, the network functions of other sites in our dataset are more obscure. It is clear, though, that many sites with no formal resources for travelers were nevertheless important nodes in the road network, as evidenced by dense palimpsests of landscape inscriptions (c.f. Bernand, 1972, 1977; Colin 1998; Cuvigny et al., 1999; Cuvigny et al., 2000; Fournet, 1995). These places are often distant from major sites, but bear evidence of people stopping and contributing graffiti and other marks for millennia. Intensive Graeco-Roman interaction with these inscribed places raises questions about how locations of “off-site” activity should be identified and incorporated into models of archaeological networks. Here, we explore the physical environment of the road network as an explanatory factor.

Using a high-resolution environmental model in conjunction with the camel network mentioned above, we examine the physical profiles of two representative inscribed stopping places by considering topography, temperature, sun shelter, wind speed, and proximity to water sources and major sites. We compare these profiles to the surrounding landscape and discuss the environmental factors that we find play a significant role in the location of these network nodes. We then discuss the content and function of some of the inscriptions at these sites and consider their enduring importance in the larger network. A major strength of archaeologically driven network analyses overall is a tendency to focus on physical and social networks simultaneously (c.f. Mills, 2017), and we further discuss their inter-relatedness here.

As a framing device in this discussion, we consider the applicability of Granovetter’s (1973) theory of “weak ties” – the idea that infrequent social connections are more important for information exchange than close ones – for approaching multi-period inscriptional galleries along the desert roads. We also consider the possible role of these locations as spaces where important encounters among “weak ties” might occur. This situates the inscribed stopping places as vibrant spaces of exchange in the desert, where graffiti and other landscape markings communicate information across social groups, language barriers, and time.

2 The Desert Networks Project

The Desert Networks Project is focused on the desert landscapes of Egypt between the Nile Valley and the Red Sea. This is an area rich in natural resources, including mineral resources such as hard stones used for sculpture and building, gems, and gold, as well as more perishable produce such as game and skins. It is also a conduit between the Nile Valley and the Indian, African, and Arab worlds, by way of both land and sea routes. The Eastern Desert was inhabited, traversed, and exploited from the beginning of Egyptian history (Bloxam, 2003; Darnell, 2021; Klemm & Klemm, 2013; Tallet, 2021), resulting in a dense archaeological landscape.

The archaeological data from the Eastern Desert has a broad scope chronologically and spatially, and it exists piecemeal in a variety of sources. The modern scholarly literature includes editions of textual corpora from the desert, reports on the excavations of individual sites, and an increasing amount of data from landscape-scale survey projects, often focused on the ancient roads (Morrow et al., 2010; Rohl, 2000; Sidebotham & Gates-Foster, 2019). In addition to this, there are travelers’ and explorers’ records from the last several centuries, many of which contain not only valuable information about desert travel and culture in the immediately pre-modern era, but also descriptions of sites that are now partially or even totally destroyed.

A primary aim of the Desert Networks project is to collect this heterogeneous, fragmented dataset and create a comprehensive resource on the archaeological material of the Egyptian Eastern Desert. The project is focused predominately on the period from the middle of the Second Millennium BCE to the end of the Third-Century CE, that is to say from the Egyptian New Kingdom to the end of the Roman Period. The dataset is still growing. To date, 266 sites are documented, of which 180 were occupied during the Graeco-Roman period (end of the fourth-century BCE to the end of third-century CE), our focus in this article. A stable, publicly available searchable version can be found on the project website: https://desertnetworks.huma-num.fr/.

The Desert Networks Project is using this data to create a dynamic, synthetic history of the region and its people over the two millennia of the study period. A critical element of this effort has been the mapping of the archaeological and historical datasets. This includes determining the physical coordinates of major and minor sites, including settlements, road infrastructure, and extraction sites; ephemeral human traces recorded by archaeological survey; water sources; the actual routes of ancient roads; and the provenance of documents that make up the historical archive from the Eastern Desert.

Being able to model the physical relationships between places informs our understanding of the networks in the study area. Many network analyses either visualize social networks in abstract space based on the frequency of communication between individuals or, alternatively, use physical distance between nodes as a primary metric of social connectivity. The mapped dataset of the Desert Networks Project, however, explicitly anchors ancient social and economic relationships to physical networks and their emplaced archaeological evidence. This allows analyses of how physical accessibility influenced the relationships of the individuals named in the thousands of documents surviving from the Eastern Desert and uncovers some of the mechanisms, other than proximity, that brought people into contact. This is helpful for considering the importance of infrequent but enduring social connections.

Physical and environmental mapping are especially productive approaches in our study area, where they allow us to consider how the logistical constraints presented by the desert landscape affected the movement of things and people. The desert, like all physical space, is not isometric, and even nearby areas can be very different in their environmental particulars. Balancing the characteristics of the landscape with their own goals and activities, humans make choices about where to live and work and about the paths on which they travel. These choices influence patterns of human activity and affect social relationships. In the landscape of the Eastern Desert, communities that are near one another in space may be separated by culture, language, the type and season of their activity in the desert, and the sets of physical paths connecting their destinations to their points of departure. These cultural dimensions mean that the physical proximity of archaeological remains is not always the best proxy for social relationships. At the same time, places where the activities of different groups intersect suggest themselves as powerful locations of social interaction. Here, we explore the idea that groups can interact with and gather information from the evidence of others’ activity in the landscape and that this most often takes place in locations where the specific characteristics of the landscape attract people from a number of different social groups, engaged in a variety of different activities. The aggregation of the material remains of human activity, including explicit responses to the evidence of earlier occupation, transforms the desert landscape into a medium that communicates across social barriers and allows different groups to exchange information, even without person-to-person interactions.

The emphasis on mapping dated archaeological material allows the Desert Networks Project to study changes in networks and activity patterns over time. By assessing physical, chronological changes in Eastern Desert networks, we can make more nuanced arguments about the influence of landscape factors on human activity. We can also explore the complex ways in which cultural shifts change the way people interact with space, transforming the physical shape of the network and the constellations of social relationships that constitute it.

3 Modeling Physical Networks: The Camel Network and the Environment

A major product of the Desert Networks Project is a large network model of potential paths through the Eastern Desert (Crépy et al., 2023; Manière et al., 2020, 2021). This model, created in a geographical information systems (GIS) environment, uses a least-cost path calculation to find optimal routes connecting contemporary sites in the study area. Several movement models have been calculated, each with the parameters adjusted to emulate travel in different periods. Special attention was given to the capabilities, terrain preferences, and water requirements of camels, which were introduced in the region during the first millennium BCE and became the main pack animal in the Eastern Desert soon after (Agut-Labordère & Redon, 2020; Chaufray, 2020; Cuvigny, 2020; Leguilloux, 2020). This information was included in the model in the form of a cost surface that avoids corridors that are too steep or rough for animals to traverse. Ethnographic and historical accounts were used to supply thresholds for these calculations, and the itineraries of more than sixty early modern (i.e., pre-motorized) traveler’s accounts were used as checks to confirm that the calculated routes were feasible.

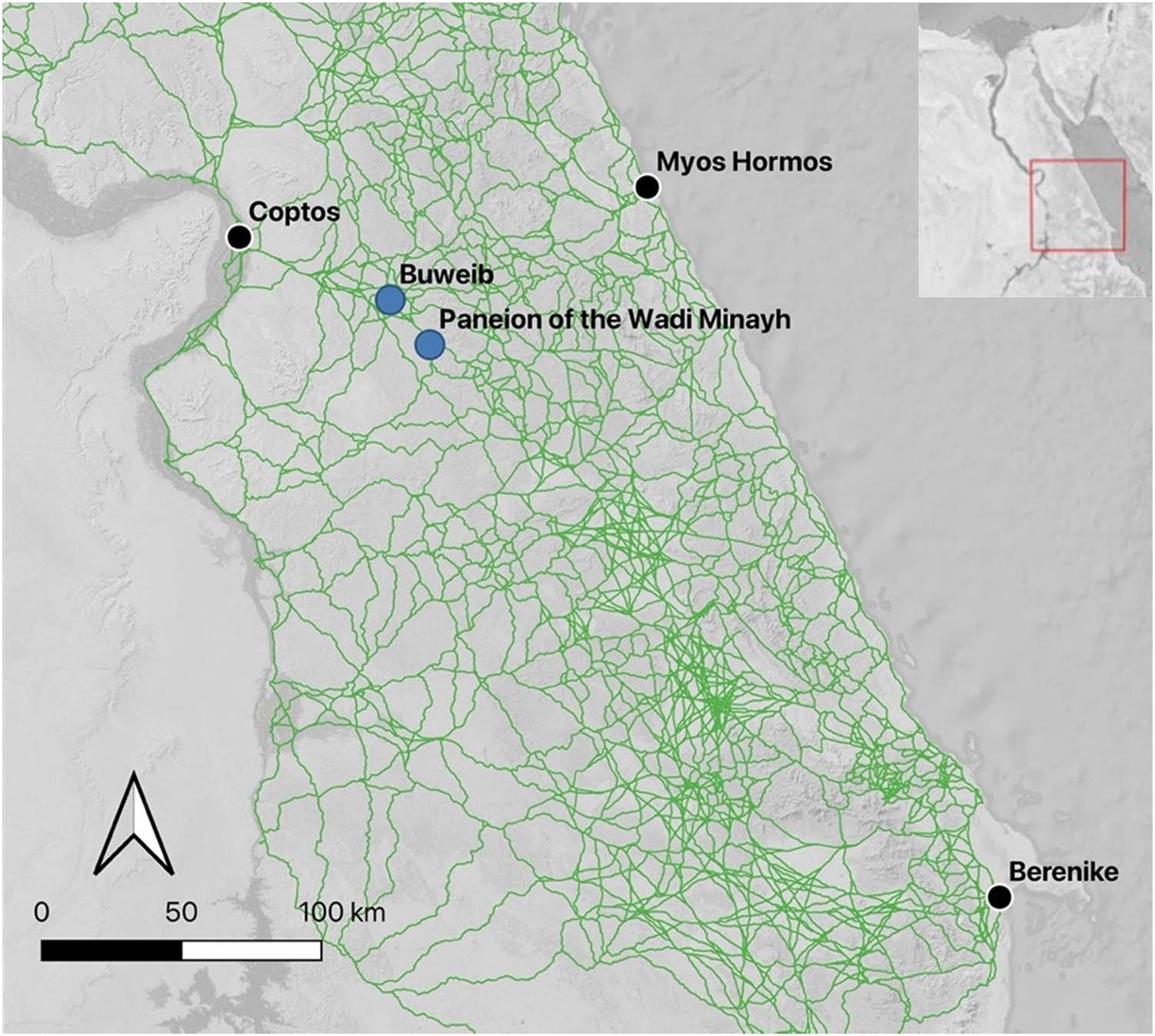

Here, we are using a version of the movement model that connects all known sites of the Hellenistic and Roman periods and is optimized for the terrain preferences and water needs of camels, the primary pack animal of those periods. The resulting network of possible paths is extremely dense (Figure 1), illustrating the complexity of the physical network connecting the nodes of human settlement and activity.

An illustration of the density of potential camel paths connecting Ptolemaic and Roman sites in the Eastern Desert. The primary origins of travel discussed in this article, as well as the case study sites, are shown.

The dataset of archaeological sites and the calculated paths connecting them create a rich body of information on which several network analyses can be performed. However, comparing the density of potential paths to the relatively lower density of sites suggests that not all the calculated paths were preferred by travelers or even in use at all. This is borne out by archaeological survey data that suggests high-intensity use of some of these potential routes, and little to no traffic on others. The survey coverage of the area is not comprehensive, and it is unfortunately not likely that time and funding will allow on-the-ground assessment of all of these routes in the near future (the region under study has a surface area of 90,000 km2). In the meantime, GIS and remote sensing suggest themselves for contributing additional information about the projected paths, and for identifying factors that make the use of certain roads more likely.

The chronological resolution in the Desert Networks dataset has allowed us to see that shifts in the prominence and accessibility of Nile Valley cities and Red Sea harbors had a strong influence on road choice (Redon, forthcoming), indicating that through-traffic across the Eastern Desert accounted for a significant part of the travel on the desert roads. Given the presence of multiple potential corridors between any two sites, as shown by the camel model, what criteria governed the choice of one route over another? Apart from the location of the departure and arrival points of the travel mentioned previously, the purpose of the journey and the means of transport used are important factors that could influence the course and route of the journey.[1] The historical conditions in which the journey takes place – whether the area is secured by one or more powers – are likewise critical.

The approach described here focuses on environmental factors that might have made certain paths, and certain stopping places along them, most attractive within the cultural constraints just noted. As a case study, we assess and compare the environment of two stopping places that were consistently used for many centuries, despite never being developed with formal infrastructure, such as architecture or other built features.

The method borrows from phenomenological approaches in archaeology in that it focuses on the features of the environment that directly affect bodily experience, like temperature, sun, shade, and wind. Phenomenology, in which a researcher draws conclusions about the influence of the landscape on people in the past by extrapolating from their own experiences exploring it, is an archaeological approach that has attracted considerable criticism for being subjective, un-reproducible, and unduly influenced by the cultural context of the researcher (Brück, 2005; Fleming, 2006; Hamilakis, 2013; Johnson, 2012). Unlike traditional phenomenology, which relies on the impressions of an individual researcher moving in the landscape in the present, the method described here puts archaeological landscapes into dialog with the environment in a way that more closely models the experience of individuals in the past. This is achieved by removing the “middleman” of the body of the researcher and comparing the spatial distribution of activity areas in the landscape directly to the conditions in the micro-environments in which the activity occurred.

We propose that identifying both static and dynamic environmental factors is an important addition to modeling networks at landscape scales. This takes for granted that networks of human activity are partly influenced by landscape factors such as terrain, weather, and the availability of resources such as water, fodder, and shelter. This is a fairly straightforward assertion[2] but it is difficult to produce a sufficiently accurate, reproducible model of these factors, many of which are experiential and subjective, to perform a meaningful analysis. Here, we present an attempt to do just that, using the incorporation of environmental data with our spatialized archaeological dataset in GIS.

For this project, we have selected environmental factors that affect human experience and are also reflected in available data layers. In this case, we are using land surface temperature in summer and winter, elevation, aspect, slope, wind speed, light and shade at various times of day and year, and the proximity of water. Each of these variables was added as a layer in the project GIS, and the locations of each of the archaeological sites as well as the road network were laid over them.

After overlaying this environmental data on the physical networks mapped in the Desert Networks dataset, we can use zonal statistics and other analyses to better assess whether some locations in the desert have quantifiably different environments than others, and how these environmental factors influence, determine, or interact with the human activity reflected in the archaeological record. In this way, we can begin to model the interplay between social activity and physical environment; the ways in which the landscape constrains or enables human activity; and the affordances of the landscape which determine human behaviors that are not strictly economic or logistical, for instance, religious or devotional activity that centers on specific natural locations or on the landscape generally. This is important because it allows us to form ideas about why certain places in the desert become heavily trafficked and inscribed locations.

4 Archaeological Network Analyses

Network Analyses were adopted early in archaeology because of their obvious application for converting large datasets of material evidence into historical narratives. The focus in early approaches was on the diffusion of technologies and materials over large areas, seen as a proxy for cultural expansion or contact (Knappett, 2014; Mills, 2017). The fundamental archaeological principle of using material culture to extrapolate past human social, emotional, and political experience meant that even early work in archaeological Network Analysis displays a blending of physical and social networks (for an early example, refer to Irwin-Williams, 1977). This is a strength of Network Analysis in archaeology, in that it naturally seeks to combine metrics of physical connectivity, usually based on distance, and social connectivity, usually visualized in abstract space. This integration more closely models human experience but raises methodological problems that are difficult to solve, and the degree to which the relationship between space and social networks is theorized still varies. In the last two decades, archaeological applications of Network Analysis have exploded (Brughmans & Peeples, 2017), due in part to the increasing accessibility and adoption of GIS and Network Analysis tools (Peeples, 2019). The theoretical questions of how best to integrate social and spatial networks, however, remain, leading archaeologists in particular to embrace an approach to networks that simultaneously investigates many kinds of relatedness (Collar et al., 2015; Knappett, 2011; see Mills, 2017).

The integration of network analyses at different scales has been identified as an important present issue in archaeology (Mills, 2017, who identifies this as a “future” issue), suggesting that many scholars are grappling with how best to overlay large, complex, and dynamic datasets that exist at a variety of spatial, temporal, and historical resolutions. For the time being, the most productive approach may be to apply Network Analyses question by question, using the constellations of data best suited to each inquiry, rather than seeking an overarching methodology.

The heterogeneity and depth of the Desert Networks dataset offer an excellent laboratory for a variety of network investigations, many of which are already in print (Crépy et al., 2022, 2023; Crépy forthcoming a, b; Gates-Foster et al., 2021, pp. 68–69; Redon, forthcoming) and have considerably advanced our understanding of multi-scalar, multi-temporal relationship dynamics in the Eastern Desert over the period of the study. The present paper continues our “multiplex” approach of overlaying network datasets with landscape-scale material and historical data. Here, we combine the physical network of the Greek and Roman road systems and the social network indicated by epigraphic data with the environmental dataset described above. The integration of environmental data in this way is rare in Network Analysis (Favory et al., 1999; Verhagen et al., 2016) and is an example of how multivariate network models can be creatively assembled. By combining these three datasets, we hope to answer questions about the network function of natural places, and the influence of the environment on the social relations in our network.

5 Granovetter’s Theory of Weak Ties

In order to structure our understanding of the network significance of non-central, unformalized sites in the Eastern Desert, we are turning to Granovetter’s (1973) theory of “weak ties.” This theory of the component relationships of a social network views individual connections as either “strong” or “weak.” The strength of a tie is defined as “the combination of the amount of time, emotional intimacy (mutual confiding), and the reciprocal services that define the tie (Granovetter 1973, p. 1361).” Put in the simplest terms, Granovetter posits that strong ties, which are characterized by frequent engagements in close social circles composed of groups of mutual acquaintances, introduce significantly less new information to each other than weak ties. Individuals with weak ties, by virtue of having access to entirely different sets of acquaintances and information, transmit far more novel and important information per encounter than do strong ties, making them powerful actors in a social network.

This makes sense in the Eastern Desert, where communities were small and, at least to some extent, itinerant and isolated from one another (although the Desert Networks dataset shows frequent circulation of letters, supplies, and presumably messengers; see also Cuvigny, 2013). The Ptolemaic and Roman communities in the desert were engaged in social and economic commerce with the relatively distant Nile Valley and Red Sea (Kruse, 2019). Information about developments in both these regions as well as the movements and political shifts of the pastoralist populations within the desert would have been potentially very important and would have been delivered from outside the immediate community (Cuvigny, 2005 commenting on the text O.Krok. 1 87). In many cases, this information would have been conveyed by traveling groups crossing the desert from the Nile to the Red Sea. We know from the epigraphic corpus that some individuals in these groups made the crossing repeatedly and would have been known, at least slightly, to the communities in the desert interior (Mairs, 2010; Redon, 2019), but others may have only passed by once.

These news-bearing travelers are a perfect example of important weak-tie individuals in our social network. We were curious, however, if certain places in our spatial network could be characterized as weak-tie nodes, and if their impact on the functioning of the spatial network was analogous to the importance of weak social ties. There were two ways to approach this: on the one hand, larger and more central nodes in the spatial network probably gathered a greater number of individuals from distant places, who could conceivably share important and novel information with each other. However, these central nodes in the Ptolemaic and Roman networks were largely controlled by official state systems (Gates‐Foster, 2012; Redon, forthcoming). Even though the records of names attested at larger sites suggest a degree of ethnic diversity, it is conceivable that diversity of ethnic origin did not translate in these cases to diversity of information because most individuals were operating within the same system.

It seemed equally possible that our true “weak-tie” nodes were the repeatedly used, unbuilt stopping places along the desert roads that, by virtue of being along major routes but spatially distant from settlements, allowed for serendipitous, unmediated interaction and exchange between people who may have met there. Due to their informality, these porous locales offer the potential for encounters and access that differs from the fortified and architecturally delineated spaces created by the fort and fortlet system that comprises the central nodes. We profile two of these many unbuilt sites here and consider the possibility that we can consider them “weak-tie” network nodes.

6 Case Studies: Inscribed Stopping Places

The sites of Buweib and the Paneion of the Wadi Minayh (Figure 2) both present a dense palimpsest of inscriptions carved into the living rock along the roadside and very little else in the way of architecture or cultural material except for scattered pottery and other evidence of ephemeral use. We chose these sites because they are clearly heavily traveled and frequently visited over a very long period of time (from the Pharaonic era to the Roman period at least). At the same time, they are not altered or formalized in a way that provides an infrastructural incentive to stop here; there are no forts, maintained wells, or settlements. These sites are clearly important locations in the network, but why are they located where they are? How do these sites, and the many others like them, function socially and spatially in the larger network of the Eastern Desert?

Buweib and the Paneion of the Wadi Minayh in context.

As discussed above, we propose that the location of these places is initially determined by favorable environmental and topographic conditions that encourage traveling parties or individuals to stop and rest. With repeated use, however, the sites begin to function in the network as locations where travelers may encounter and interact with members of other social groups, such as indigenous pastoralists and long-range travelers on different itineraries. They also encounter traces left by past travelers in the form of camp remains and graffiti or inscriptions in the landscape. Gradually, these encounters with the past become associated, in aggregate, with the conceptual world of the desert landscape, and the inscriptions begin to acknowledge this through dedication to gods such as Min, the Egyptian god of the desert, and Pan, the Greek version of Min (Cuvigny et al., 2000). As places accrue inscriptions dedicated to these gods, the presence of the gods in place is evoked and materialized. This in turn provides an incentive for traveling parties to stop, adding their own material traces to the dialog of present and past, increasing the chances of weak-tie social encounters (Gates‐Foster, 2012).

Following Granovetter’s theory that weak ties allow for the most diverse exchange of ideas and information in a network, we conclude that these locations in the Eastern Desert network, which are not formally constructed or overseen by authoritative structures, function as places where weak-tie connections are most likely to be explored. Below, we present the variety of inscriptional practices and the evidence for dialog between inscriptions.

6.1 Case Study 1: Paneion of Wadi Minayh

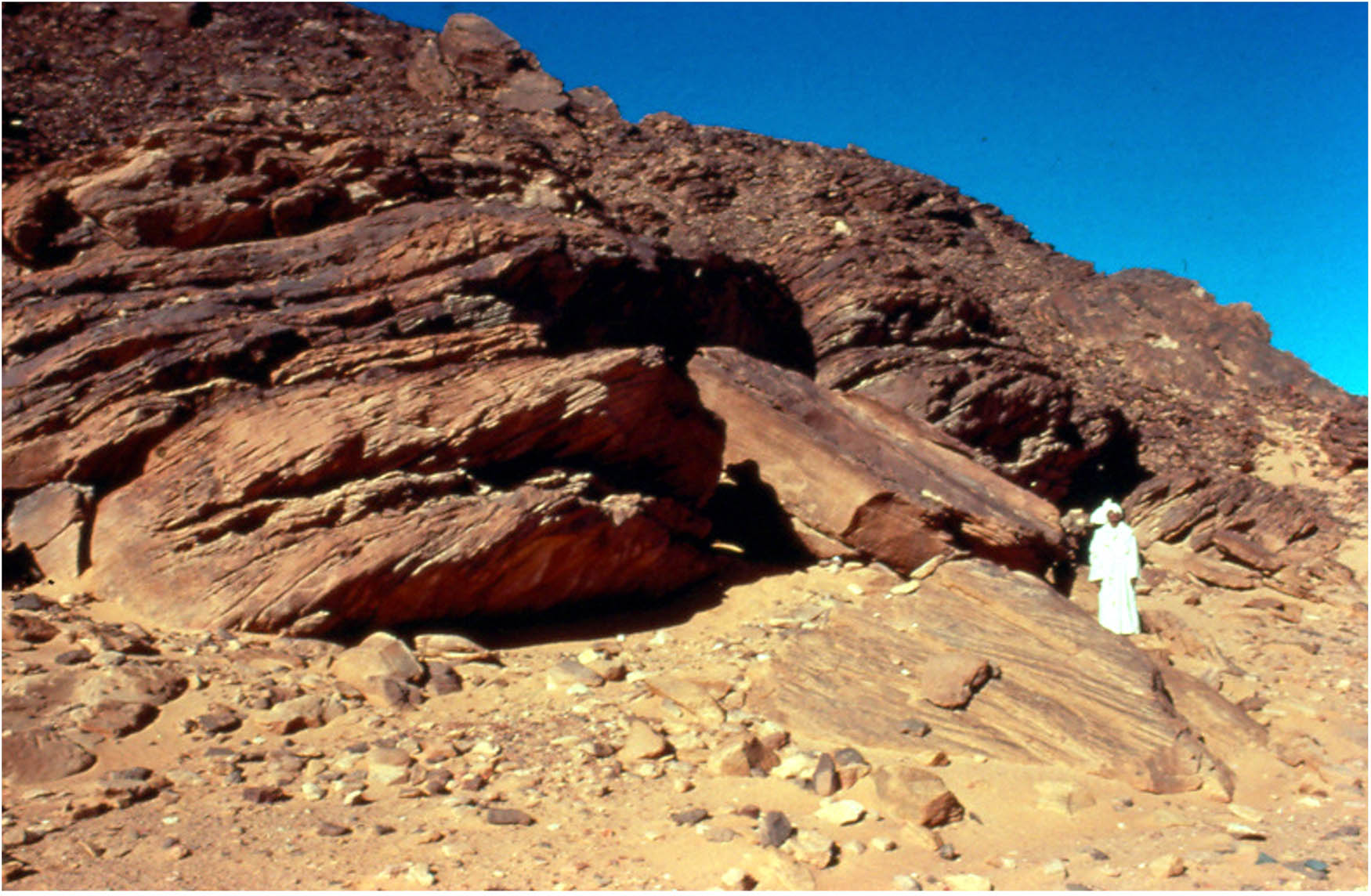

The Paneion of Wadi Minayh (Desert Networks Site 0150, https://desertnetworks.huma-num.fr/sites/DN_SIT0150) is a stopping place on the long desert road between Quft (ancient Koptos) in the Nile Valley and the southern Red Sea port of Berenike. The natural focus of this site is a small rock shelter, formed by tumbled boulders that enlarge a hollow in the wadi wall (Figure 3.). The rock overhang is quite small, too small to accommodate more than a few individuals, and probably served more as a landmark than an actual shelter for larger traveling parties. At the same time, the environmental profile of the site is hospitable relative to its surroundings on the local scale, meaning that it is a natural place for travelers to stop and rest.

The Paneion of Wadi Minayh. The rock shelter pictured is the focal point of the many inscriptions at the site. Photo Steve Sidebotham.

The rock shelter is on the eastern side of a protruding north-south outcrop. It is surrounded on three sides by a flat wadi bottom, meaning that there is space for larger parties to disperse around the area. The situation of the promontory also means that travelers could choose between sun and shade at any time of day, a significant advantage for a year-round stopping place in a landscape where shade is critical in the summer and the sun is comfortable in the winter (Figure 4). The wadi rises slightly around the promontory, and the wadi floor in front of the rock shelter is a few meters higher than the surrounding wadi beds. This means that a slight breeze is possible, lowering local surface temperatures and providing comfort on hot days. However, other studies we have conducted indicate that wind shelter is the most important factor in the location of campsites in the Eastern Desert, meaning that only the gentlest breezes are considered optimal for a stopping place. Based on the environmental analyses described above, average wind speeds in this location are less than 3 km/h, significantly less than the local average of 3.6 km/h. Furthermore, shelter from an unpleasant wind is available in the shadow of the promontory (Figure 5).

Shade in the morning (8 am June 21) and evening (4 pm June 21). Google Satellite Imagery.

Average annual wind speed (10 m above surface) near the Paneion of the Wadi Minayh. Green areas are higher speeds, purple are lower. Note the large area of intermediate wind speed (between 3 and 3.5 km/h) near the site. Data from globalwindatlas.info; Google Satellite Imagery.

Finally, there is an unusual availability of surface water in the vicinity of the site. Salt pans on satellite imagery show that there is occasionally a pool at the foot of the rock shelter itself, and several smaller seasonal pools in the vicinity (Figure 6). There is a larger source of surface water not far away from the Paneion, in the wadi Minayh el-Hir. In the Late Roman period, when the Paneion is used intensively, this water source is developed with a water-retaining structure (Desert Networks Site 0117, https://desertnetworks.huma-num.fr/sites/DN_SIT0117, refer to Crépy & Redon, 2022, § 18, 60 and Figure 5). Abundant late Roman pottery is apparent on the surface (Sidebotham & Gates-Foster, 2019).

Evidence of seasonal surface water visible on satellite imagery. A small area directly east of the Paneion is too small to see at this resolution. Note the circular water-retaining structure in the large area to the east (black arrow). Google Satellite Imagery.

Dozens of petroglyphs and inscriptions crowd the rocks and crevices surrounding the rock shelter (Colin, 1998; Cuvigny et al., 1999; Littmann & Meredith, 1954; Winkler, 1938). The inscriptions are in hieroglyphs, Greek, Latin, Nabataean, and South Arabian, although Greek predominates. A variety of motifs are represented in the petroglyphs, including boats, animals, Min figures, Bedouin wusum and human feet. The hieroglyphic inscriptions show that the Paneion was already a road stop during the Middle and New Kingdoms, when it was probably en route to important mines and quarries (Colin, 1998). The scribe of an expedition leader left his name here at some point during the Pharaonic period (Colin, 1998, no. 3). A figure of the desert god Min, engraved in this period, shows that the place was already associated with the deity.

After a long period of apparent disuse (no inscriptions and pottery are attributable to the Ptolemaic period, which does not mean that the site was not used but may show that the nature of the activity at the site changed), the site became active again at the very beginning of the Roman period as a stopping place on the route between Coptos and Berenike. The Roman-era inscriptions were left by people on their way to or from the Red Sea, probably engaged in commercial activities. An Arab slave of a freedman left his signature precisely on October 27, 4 BCE (Cuvigny et al., 1999, no. 1), and a certain Gaius Numidius Erôs recorded his return from India in February–March 2 BCE. Nabataean graffiti of the Early Empire shows that Nabataean merchants were also using the route. Taken together, these inscriptions attest to the presence of people of many different origins and social positions operating in the area in the same period. The dates given in the Roman-period inscriptions are from almost every month of the year. This shows that this site was used by travelers even during the hottest summer months, when the relatively more comfortable local conditions, compared to other places along the road, would have been a major advantage.

The site does not accrue new graffiti during the second half of the first-century CE. The Paneion was, at this time, located between the new forts of Khashm el-Minayh/Didymoi (Desert Networks Site 0126, https://desertnetworks.huma-num.fr/sites/DN_SIT0126) to the northwest, and Minayh el-Hir/Aphrodites Orous (Desert Networks Site 0155, https://desertnetworks.huma-num.fr/sites/DN_SIT0155) to the southeast (Figure 2, above). The construction of these fortified road stops nearby presumably changed stopping practices and made it unnecessary to linger at the Paneion (Cuvigny et al., 1999, no. 135), although traffic would have continued to pass it in this period, and indeed, it may have been visited without the creation of new graffiti. Use of the site intensified after the abandonment of the forts, particularly between the fourth- and sixth-century CE. This is also when the Minayh el-Hir was developed with structures to retain seasonal surface water.

Several of the inscriptions in the Paneion use the dedicatory proskynemata formula, reminding us that there is a religious aspect to the practice of marking the place. The name of the god Pan is not explicitly mentioned in any of the Roman inscriptions, but the site is clearly dedicated to the god Min, Pan’s Egyptian precursor whose image occurs in several places here. Min was associated with the desert landscape and graffiti depicting or invoking the god is often found near small hollows or shelters like the overhang here, which creates a focal point for the inscriptional gallery. A major sanctuary of Min was located in Koptos in the Nile Valley, at the head of this desert road, and Min/Pan was seen as a patron of travelers on the desert roads. Dedications (explicit or oblique) to this deity were therefore an act of piety, a prayer for self-preservation, and a reassuring indication of the safe passage of previous expeditions.

The variety of markings at the site attest to its long use, starting with the petroglyphs of the prehistoric period. The roughly contemporary Nabatean, Roman, and indigenous marks suggest the possibility of contemporary use by different social groups, who, even if they did not meet here in person, would have encountered each other’s graffiti and reflected on the presence and activities of these other groups. Many of the inscriptions contain personal names, dates, and information about origin and destination, meaning that they serve as a medium of information exchange between people who otherwise would not have a chance to share these details. The inscriptions also allow us a glimpse of the social groups who traveled together, as many travelers who made individual, personal graffiti refer to membership in the same expeditions (see for instance Cuvigny et al., 1999, no. 4–6).

6.2 Case Study 2: Buweib/al-Bawab

The site of Buweib (Desert Networks Site 0085, https://desertnetworks.huma-num.fr/sites/DN_SIT0085) is a stopping place in the Wadi Minayh, at its northern end. It is located at the junction of routes south from Krokodilo (Desert Networks Site 0096, https://desertnetworks.huma-num.fr/sites/DN_SIT0096) and Laqeita (Desert Networks Site 0130 https://desertnetworks.huma-num.fr/sites/DN_SIT0130) on the way to the fortress of Khashm el-Minayh/Didymoi (Desert Networks Site 0126) (Figure 2, above). This places the site roughly at the center of a triangular zone of interchange between the road from Koptos, in the Nile Valley, to the southern Red Sea port of Berenike, and the road from Koptos to the central Red Sea port of Myos Hormos. Pottery scatters provide evidence of activity here in the third- to second-century BCE, late first-century BCE to first-century CE, third- to fourth- century CE, and ninth- to tenth-century CE (Sidebotham & Gates-Foster, 2019).

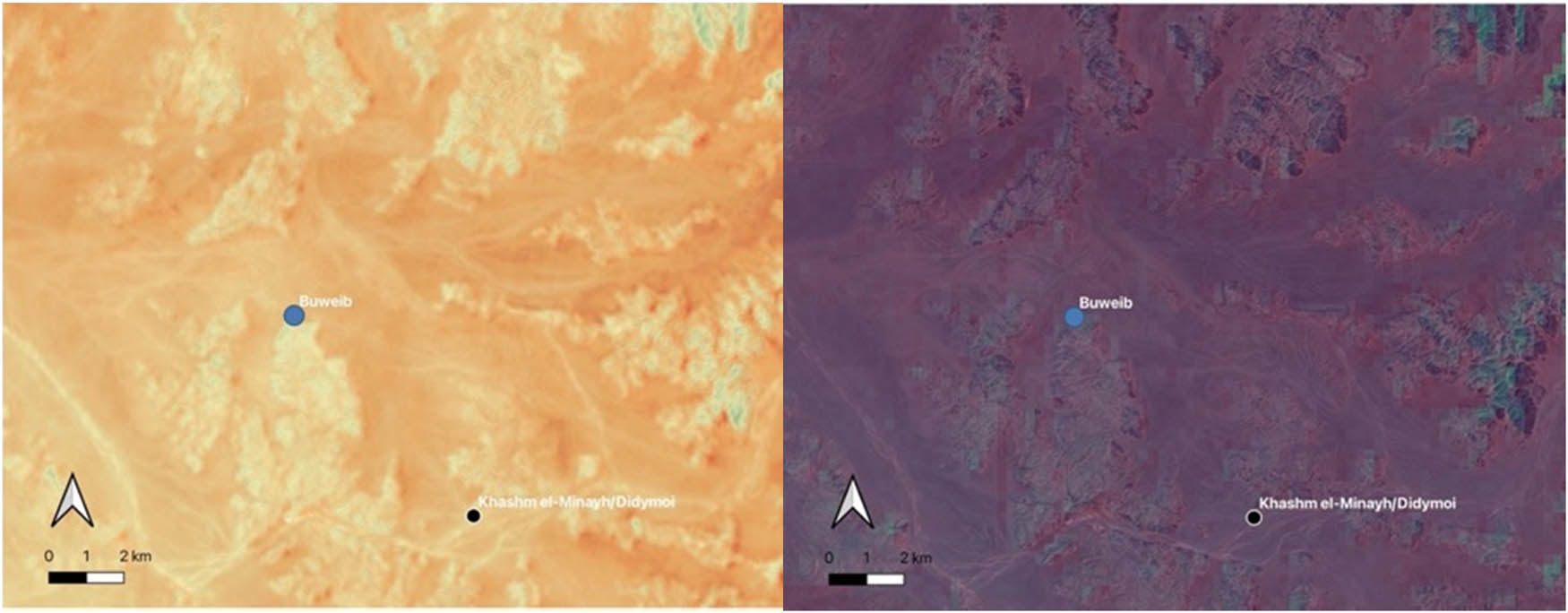

As at the Paneion of Wadi Minayh, a small rock shelter on the side of the wadi provides the focal point for the site (Figure 7). Also like the Paneion, the site is on a slight rise that corresponds to a slight breeze and locally low temperature, a difference that was probably meaningful although in this particular instance it is not statistically different from the local mean (Figure 8). The site is located on the northern face of a promontory with coves to the east and west, providing not only shelter from the wind but also a choice of shade or sun at any time of day (Figure 9). The similarities between the two sites and the environmental advantages that these characteristics afford bolster the idea that they are both intentionally chosen for this reason.

The rock shelter at the site of Buweib. As at the Paneion of the Wadi Minayh, the small shelter serves as a focal point that attracts inscriptions. Photo Adam Bülow-Jacobsen (MAFDO).

Left: Average June land surface temperature at Buweib. The flat areas surrounding the site average 55°C, compared with 58.5 in the broader area. Data from Landsat 8. Right: Average annual windspeed. Greens are higher speed, and purples lower. At the Paneion of Wadi Minayh, the windspeed is between 3 and 3.5 km/h. Data from globalwindatlas.info.

Shade in the morning (8 am June 21) and evening (4 pm June 21). Google Satellite Imagery.

Petroglyphs and graffiti cluster around the rock shelter. The texts date from the New Kingdom (Colin, 1998; Winkler, 1938), with several of the Pharaonic inscriptions linked to mining expeditions. The Greek graffiti is similar in content to those at the nearby Paneion of Wadi Minayh, but also includes inscriptions clearly dated to the Ptolemaic period (Cuvigny et al., 2000), suggesting that the break in use that occurred at the Paneion during the period did not affect this site in the same way. This may be due to the site’s proximity to one of the several roads leading to the harbor of Myos Hormos, founded by the Ptolemies, which links the Nile Valley to the Red Sea coast via the gold mining and quarrying zone of the Wadi Hammamat which was exploited at the same time (Redon, forthcoming). Ptolemaic prospectors entering the region would have been aware of this route, and five of the inscriptions at Buweib gloss the god Pan as “the one who gives gold,” indicating the relationship between the Ptolemaic use of the site and the renewal of gold-mining activity in the region.

It is also probable that, on these expeditions, successive waves of officials from the Nile Valley engaged indigenous guides to help them locate the best paths through the desert. Rock shelters and other good stopping places would have been known to the local pastoralist communities, who maintained a constant presence in the Egyptian desert through successive periods of occupation and abandonment from the Nile Valley (Cooper, 2022, pp. 11–21; Cuvigny, 2022). This is another example of the importance of transmitting information across different social networks and has a real effect on the spatial network of the Eastern Desert in different periods.

The Roman inscriptions at the site are similar in content to those at the Paneion of Wadi Minayh, demonstrating an established inscriptional practice adopted by desert travelers that follows similar patterns. The reception of Pharaonic images of Min inspired dozens of dedicatory inscriptions to his Graeco-Roman counterpart, Pan (Figure 10). Here, Pan bears epithets such as “of the Good Road,” a hopeful traveler’s choice, and “of the desert,” responsively acknowledging both the surroundings of the site and the visible presence of Min who also bears the epithet “of the desert.”

An image of Pan at Buweib which responds to the earlier depictions of Min at the site. Photo Adam Bülow-Jacobsen (MAFDO).

The diachronic range represented suggests a frequent, if not consistent, engagement with this site over thousands of years and at times when patterns of economic activity and road use, not to mention methods of travel, must have varied considerably. The fact that the rock saw the emergence in the Ptolemaic period of a new divine epithet for Pan (“the one who gives gold”) that is not attested elsewhere in Egypt is striking and shows how reading previous messages was an important act for travelers passing through. This epigraphic innovation modifies the traditional formula and responds to the authors and dedicants in a moment of informational exchange over time and space. Like the inscriptions in Wadi Minayh, these markings demonstrate the durability of the site’s attraction and suggest that the act of inscribing and the conversational nature of these galleries made them points of significance over a broad period of time, connecting travelers over time and space.

7 Discussion and Conclusions

Taken together, the two case study sites illustrate a phenomenon that can be seen in many of the non-architectural archaeological sites in the Eastern Desert. Proximity to topographically determined routes of travel through the rough desert terrain is combined with local environmental conditions that make these particular locations attractive to traveling parties of many different types (indigenous, exogamous, large and small groups, and both short- and long-range itineraries). Notably, these sites also offer topographic and environmental features that make them more attractive than nearby locales even as conditions shift from hour to hour or season to season. The broad appeal of these landscape nodes means that they begin to accrue signs of human use, which attract the attention of other travelers attuned to the desert landscape. Slowly, over hundreds or even thousands of years, the aggregation of these signs organically creates a known, recognizable place in the road itinerary that becomes a locus of devotional activity and social messaging that is not controlled or determined by any one group or authority. The organic nature of these sites, and the novel, diverse information they are made to communicate, make them analogous to “weak-tie” network connections.

Looking at two of the “weak tie” sites in our corpus sheds some light on the importance of this type of location in the cultural landscape of the Eastern Desert, as well as on certain circulation patterns in the region. First, it is interesting to note that although the Paneion of the Wadi Minayh was not in use between the end of the New Kingdom and the beginning of the Early Roman era, the memory of its existence and environmental utility as a stopping place remained. After a period of fluorescence in the early Roman era, the site was eclipsed in the late first century CE by a fortified road station built a few kilometers away. Once this was abandoned in the third–fourth centuries, travelers returned to using the Paneion as a primary road stop and even formalized nearby water sources. This demonstrates a level of continuity and knowledge of the site’s location and significance through anepigraphic periods. The nomadic population in the area likely had much to do with the maintenance and transmission of this information, plausibly through “weak-tie” interactions with groups arriving from the Nile Valley.

Second, the location of so-called “weak-tie” sites may have influenced the location of the central nodes of the networks. This phenomenon can be seen in the eventual construction of Roman forts near the two case-study sites. Didymoi is less than 10 km from El-Buweib and Aphrodito is 12 km from the Paneion. The forts were built when the Roman administration decided to make traffic to the port of Berenike safer and more regulated. In both cases, however, the first–second-century CE forts were not built at the exact location of the older road stops, but at nearby locations that privileged logistical economy, visibility, defensibility, the pace of the horses that carried the couriers across the desert, and offered more space for large caravans. The architectural innovation of the fortresses, which provided water, shelter, and other resources directly on the fastest and most developed roads, meant that it was no longer necessary to go a little out of the way to find the comfortable, sheltered stopping places provided by the topography of the desert landscape. At the same time, it seems that the patterns of memory and itinerary were stable enough to incentivize the construction of formal road stops near the older, environmentally determined, stopping places (see the similar conclusions of Fournet, 1995 on another rock-shelter of the Eastern Desert, Abu Ku).

As we know, networks are not simply nodes connected by lines along which nothing happens. In a physical network, the activity along the lines and in the interstitial places is important for understanding the function of the network overall. Analyses of networks of movement and connectivity in physical space require the consideration of the environment that is passed through, not merely as a gradient of difficulty or ease of movement but as a space where people have experiences and form relationships and ideas that influence their pragmatic and symbolic behavior.

Here, we have pursued the idea that landscape inscriptional galleries along road corridors mark minor nodes in the network, analogous to “weak ties,” where less formality and institutional involvement generates richer communication across professions, cultural groups, and time. These locations in fact allow encounters between people who have no network connections at all, as the deep palimpsest of the landscape inscriptions creates an opportunity for individuals to enter into dialog with marks made hundreds or thousands of years before their time. As in the weak-tie model, these connections communicate ideas about the movement and marking systems of other groups operating in the landscape and outside the traveler’s immediate social group. This also inspires reflection about the historical character of the desert landscape and the gods who control it. In this respect, the attractive power of natural rock shelters is not simply due to the physical protection they offer, but also to the ways in which they evoke the niche or shrine, and the long tradition of associating natural cavities with desert gods that stretches into the Pharaonic period, if not before. The palimpsest of markings at these places enriches the experience of travelers by reiterating these ideas and producing an appropriately natural landscape locus for devotional attention to gods associated with the wild desert, such as Min/Pan.

The ties across time, while weak in the sense that they are indirect, create a community of shared place-specific religious knowledge and practice across time at various scales (Gates‐Foster, 2012). In the same way, interacting with marks in a variety of scripts and systems would have provoked an awareness of the many different groups who were operating on the desert roads. Roadside inscriptional galleries served as information hubs where individuals could broadcast their presence and intentions to other travelers. The placement of these messages where environmental factors encouraged stopping ensured that the messages would repeatedly find an audience.

In summary, we assert here that the location of these stopping places along the desert roads is influenced in part by testable, concrete environmental features at the local level. Places that feature hospitable combinations of environmental attributes will be attractive to any traveling party with sufficient landscape knowledge to recognize them. When these naturally hospitable places are also central to the networks of movement and activity of many different groups, they become hubs where people repeatedly interact with each other and with the landscape. The desert environment ensures that simple spatial centrality is not the primary determinant of stopping behavior: attractive stopping places need to be both convenient and locally comfortable.

The iterative practice of landscape marking communicates that the place has been tested by many generations of desert travelers, effectively using the living rock of the wadi as a “weak-tie” medium for passing information between unrelated groups. The information communicated is not merely pragmatic or logistical, but also involves the dissemination and maintenance of ideas about history, cult, and the overlay of emotional and conceptual ideas on the desert landscape. Furthermore, the messages held in the rock inscriptions at these sites motivate responses in the same medium, exercising influence on how people interact physically and conceptually with these landscape nodes. Passage through and interaction with these places is an important feature of activity and communication in the desert road network. These dynamics are a productive and important dimension of understanding physical and social networks in the landscape, and merit further incorporation of environmental data into traditional Network Analyses.

-

Funding information: The work was done in the frame of the project Desert Networks, which has received funding from the ERC under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program (grant agreement no. 759078). The Open Access status of this article has received funding from the Centre of Excellence in Ancient Near Eastern Empires, funded by the Research Council of Finland (decision number 352748).

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission. The authors contributed equally to the conception and design of the research and analysis described here. LDH prepared the manuscript with contributions from all co-authors.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

Agut-Labordère, D., & Redon, B. (2020). Introduction. Dromadaires et chameaux de l’Asie centrale au Nil dans les mondes anciens (IVe millénaire av. J.‑C. – premiers siècles de notre ère). In D. Agut-Labordère & B. Redon (Eds.), Les vaisseaux du désert et des steppes: Les camélidés dans l’Antiquité (Camelus dromedarius et Camelus bactrianus) (pp. 9–20). MOM Éditions. doi: 10.4000/books.momeditions.8522.Search in Google Scholar

Bernand, A. (1972). De Koptos à Kosseir. Brill.10.1163/9789004675773Search in Google Scholar

Bernand, B. (1977). Pan du Désert. Brill.10.1163/9789004675803Search in Google Scholar

Bloxam, E. G. (2003). The organisation, transportation and logistics of hard stone quarrying in the Egyptian Old Kingdom: A comparative study (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University College, London.Search in Google Scholar

Brück, J. (2005). Experiencing the past? The development of a phenomenological archaeology in British prehistory. Archaeological Dialogues, 12(1), 45–72.10.1017/S1380203805001583Search in Google Scholar

Brughmans, T., & Peeples, M. (2017). Trends in archaeological network research: A bibliometric analysis. Journal of Historical Network Research, 1, 1–24. http://jhnr.uni.lu/index.php/jhnr/article/view/10.Search in Google Scholar

Chaufray, M. P. (2020). Les chameaux dans les ostraca démotiques de Bi’r Samut (Égypte, désert Oriental). In D. Agut-Labordère & B. Redon (Eds.), Les vaisseaux du désert et des steppes: Les camélidés dans l’Antiquité (Camelus dromedarius et Camelus bactrianus) (pp. 135–170). MOM Éditions. doi: 10.4000/books.momeditions.8567.Search in Google Scholar

Colin, F. (1998). Les Paneia d’El-Buwayb et du Ouadi Minayḥ sur la piste de Bérénice à Coptos: Inscriptions égyptiennes. BIFAO, 98, 89–125.Search in Google Scholar

Collar, A., Coward, F., Brughmans, T., & Mills, B. (2015). Networks in archaeology: Phenomena, abstraction, representation. Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory, 22(1), 1–32. doi: 10.1007/s10816-014-9235-6.Search in Google Scholar

Cooper, J. (2022). Children of the Desert: The Indigenes of the Eastern Desert in the Pharaonic Period and the longue durée of Desert Nomadism. In H. Cuvigny (Ed.), Blemmyes. New Documents and New Perspectives (pp. 5–40). Presses de l’IFAO.10.2307/jj.18654597.4Search in Google Scholar

Crépy, M. (Forthcoming a). Tracer la route ou brouiller les pistes? Etudier les itinéraires anciens par l’imagerie satellitaire. In S. Devaux, S. Esposito, & M. Prévost (Eds.), Transports et mobilités dans l’Égypte antique. Montpellier University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Crépy, M. (Forthcoming b). Environnement et géographie de la région de Dios et de Bi’r Bayza. In E. Botte, H. Cuvigny, & M. Reddé (Eds.), Du côté de chez Zeus, Fouilles de la mission archéologique française du désert Oriental à Abû Qurayya (Dios) et Bi’r Bayza. Presses de l’IFAO.Search in Google Scholar

Crépy, M., Faucher, T., Redon, B., Le Bomin, J., Manière, L., Marchand, J., Rabot, A., & Villars, N. (2022). Désert oriental (2021) – Stathmoi et metalla. Exploiter et traverser le désert oriental à l’époque ptolémaïque. Bulletin Archéologique des Écoles françaises à l’étranger. doi: 10.4000/baefe.6368.Search in Google Scholar

Crépy, M., Manière, L., & Redon, B. (2023). Roads in the sand: Using data from modern travelers to reconstruct the ancient road networks of Egypt’s Eastern Desert. In T. Kulayci (Ed.), The archaeologies of roads (pp. 245–274). Digital Press at the University of North Dakota.Search in Google Scholar

Crépy, M., & Redon, B. (2022). Water resources and their management in the Eastern Desert of Egypt from the Antiquity to present-days: Contribution of the accounts of modern travelers and early scholars (1769–1951). In C. Durand, J. Marchand, B. Redon, & P. Schneider (Eds.), Connected Spaces. Proceedings of the Red Sea Conference IX (pp. 451–492). MOM Éditions. https://books.openedition.org/momeditions/16271.10.4000/books.momeditions.16471Search in Google Scholar

Cuvigny, H. (2005). Ostraca de Krokodilô. La correspondance militaire et sa circulation. O. Krok. 1-151. Praesidia du désert de Bérénice II. Presses de l’IFAO.Search in Google Scholar

Cuvigny, H. (2013). Hommes et Dieux en réseaux: Bilan papyrologique du programme “Praesidia du désert Oriental égyptien”. Comptes-Rendus de l’Académie des Inscriptions et Belles Lettres, 157(1), 405–442.10.3406/crai.2013.95330Search in Google Scholar

Cuvigny, H. (2020). L’élevage des chameaux sur la route d’Edfou à Bérénice d’après une lettre trouvée à Bi’r Samut (IIIe siècle av. J.-C.). In D. Agut-Labordère & B. Redon (Eds.), Les vaisseaux du désert et des steppes: Les camélidés dans l’Antiquité (Camelus dromedarius et Camelus bactrianus) (pp. 171–180). MOM Éditions. doi: 10.4000/books.momeditions.8572.Search in Google Scholar

Cuvigny, H. (Ed.). (2022). Blemmyes: New Documents and New Perspectives. Presses de l’IFAO.Search in Google Scholar

Cuvigny, H., Bülow-Jacobsen, A., & Bosson, N. (2000). Le paneion d’Al-Buwayb revisité. BIFAO, 100, 243–266.Search in Google Scholar

Cuvigny, H., Bülow-Jacobsen, A., Robin, C., & Nehmé, L. (1999). Inscriptions rupestres vues et revues dans le désert de Bérénice. BIFAO, 99, 133–193.Search in Google Scholar

Darnell, J. C. (2021). Egypt and the Desert. Cambridge University Press.10.1017/9781108900683Search in Google Scholar

Favory, F., Girardot, J. J., Nuninger, L., & Tourneux, J. F. (1999). ARCHAEOMEDES II: Une étude de la dynamique de l’habitat rural en France méridionale, dans la longue durée (800 av. J.-C.-1600 ap. J.-C.). AGER, 9, 15–35.Search in Google Scholar

Fleming, A. (2006). Post-processual landscape archaeology: A critique. Cambridge Archaeological Journal, 16(3), 267–280. 10.1017/S0959774306000163.Search in Google Scholar

Fournet, J.-L. (1995). Les inscriptions grecques d’Abu Ku’et de la route de Quft-Qusayr. BIFAO, 95, 173–233.Search in Google Scholar

Gates‐Foster, J. E. (2012). The well-remembered path: Roadways and cultural memory in Ptolemaic and Roman Egypt. In S. E. Alcock & R. J. A. Talbert (Eds.), Highways, byways, and road systems in the pre-modern world (pp. 202–221). Wiley-Blackwell.10.1002/9781118244326.ch10Search in Google Scholar

Gates-Foster, J. E., Goncalves, I., Redon B., Cuvigny, H., Hepa, M., & Faucher, T. (2021). The Early Imperial fortress of Berkou, Eastern Desert, Egypt. JRA, 34(1), 30–74. doi: 10.1017/S1047759421000337.Search in Google Scholar

Granovetter, M. S. (1973). The strength of weak ties. American Journal of Sociology, 78(6), 1360–1380.10.1086/225469Search in Google Scholar

Hamilakis, Y. (2013). Archaeology of the senses: Human experience, memory, and affect. Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9781139024655Search in Google Scholar

Irwin-Williams, C. (1977). A network model for the analysis of prehistoric trade. In T. K. Earle & J. E. Ericson (Eds.), Exchange systems in prehistory (pp. 141–151). Academic Press.10.1016/B978-0-12-227650-7.50014-6Search in Google Scholar

Johnson, M. (2012). Phenomenological approaches in landscape archaeology. Annual Review of Anthropology, 41, 269–284. doi: 10.1146/annurev-anthro-092611-145840.Search in Google Scholar

Klemm, D. & Klemm, R. (2013). Gold and gold mining in ancient Egypt and Nubia: Geoarchaeology of the ancient goldmining sites in the Egyptian and Sudanese eastern deserts. Springer.10.1007/978-3-642-22508-6Search in Google Scholar

Knappett, C. (2011). An archaeology of interaction: Network perspectives on material culture and society. Oxford University Press.10.1093/acprof:osobl/9780199215454.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Knappett, C. (2014). What are social network perspectives in archaeology?. In E. Evans & G. Felder (Eds.), Social network perspectives in archaeology (Special Issue). Archaeological review from cambridge (Vol. 29, No. 1, pp. 179–184). University of Cambridge.Search in Google Scholar

Kruse, T. (2019). The Archive of the “Camel Driver” Nikanor. In B. Wotek (Ed.), Infrastructure and distribution in Ancient Economies. The Flow of Money, Goods and Services (pp. 369–380). Austrian Academy of Sciences Press.10.2307/j.ctvddzgz9.15Search in Google Scholar

Leguilloux, M. (2020). Camelus ou Equus?: Le rôle des dromadaires dans les stathmoi et praesidia du désert Oriental d’Égypte. In D. Agut-Labordère & B. Redon (Eds.), Les vaisseaux du désert et des steppes: Les camélidés dans l’Antiquité (Camelus dromedarius et Camelus bactrianus) (pp. 181–198). MOM Éditions. doi: 10.4000/books.momeditions.8577.Search in Google Scholar

Littmann, E. & Meredith, D. (1954). Nabatæan Inscriptions from Egypt–II. Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, 16(2), 211–246.10.1017/S0041977X00105956Search in Google Scholar

Mairs, R. (2010). Egyptian ‘Inscriptions’ and Greek ‘Graffiti’ at El Kanais (Egyptian Eastern Desert). In J. Baird & C. Taylor (Eds.), Ancient graffiti in context (pp. 153–164). Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Manière, L., Crépy, M., & Redon, B. (2020). Geospatial data from the “building a model to reconstruct the Hellenistic and Roman road networks of the Eastern Desert of Egypt, a semi-empirical approach based on modern travelers’ itineraries.” Journal of Open Archaeology Data, 8, 7. doi: 10.5334/joad.71.Search in Google Scholar

Manière, L., Crépy, M., & Redon, B. (2021). Building a model to reconstruct the Hellenistic and Roman road networks of the Eastern Desert of Egypt: A semi-empirical approach based on modern travelers’ itineraries. Journal of Computer Applications in Archaeology, 4(1), 20–46. doi: 10.5334/jcaa.67.Search in Google Scholar

Mills, B. (2017). Social network analysis in archaeology. Annual Review of Anthropology, 46(1), 379–397. doi: 10.1146/annurev-anthro-102116-041423.Search in Google Scholar

Morrow, M., Morrow, M., Judd, T., & Phillipson, G. (2010). Desert RATS: Rock Art Topographical Survey in Egypt’s Eastern Desert. Site catalogue. Archeopress.10.30861/9781407307107Search in Google Scholar

Peeples, M. (2019). Finding a place for networks in archaeology. Journal of Archaeological Research, 27, 451–499. doi: 10.1007/s10814-019-09127-8.Search in Google Scholar

Redon, B. (2019). Introduction: La petite société des fortins des routes du désert de Bérénice. Les réseaux personnels de Philoklès, Apollôs et Ischyras. In A. Bülow-Jacobsen, J.-L. Fournet, & B. Redon. Ostraca de Krokodilô II. La correspondance privée et les réseaux personnels de Philoklès, Apollôs et Ischyras (pp. 1–31). Presses de l’IFAO.Search in Google Scholar

Redon, B. (Forthcoming). Sur la Route, Logiques d’occupation et réseaux de circulation dans le Désert Oriental égyptien aux époques hellénistique et romaine. MOM Editions.Search in Google Scholar

Rohl, D. (2000). The followers of Horus: Eastern Desert Survey report, volume 1. Institute for the Study of Interdisciplinary Sciences.Search in Google Scholar

Sidebotham, S. E., & Gates-Foster, J. E. (Eds.). (2019). The archaeological survey of the desert roads between Berenike and the Nile Valley. Expeditions by the University of Michigan and the University of Delaware to the Eastern Desert of Egypt, 1987–2015. American Schools of Oriental Research.Search in Google Scholar

Tallet, P. (2021). Les papyrus de la mer Rouge II. Le journal de Dedi et autres fragments de journaux de bord (papyrus Jarf C, D, E, F, Aa). Presses de l’IFAO.10.2307/jj.18654600Search in Google Scholar

Verhagen, P. (2018). Spatial analysis in archaeology: Moving into new territories. In C. Siart, M. Forbriger, & O. Bubenzer (Eds.), Digital geoarchaeology: Bridging the gap between archaeology, geosciences and computer sciences (pp. 11–26). Springer.Search in Google Scholar

Verhagen, P., Nunninger, L., Bertoncello, F., & Castrorao Barba, A. (2016). Estimating The ‘memory of landscape’ to predict changes in archaeological settlement patterns. In S. Campana, R. Scopigno, G. Carpentiero, & M. Cirillo (Eds.), CAA2015. Keep the Revolution Going. Proceedings of the 43rd Annual Conference on Computer Applications and Quantitative Methods in Archaeology (pp. 623–636). Archaeopress.10.2307/jj.15135955.73Search in Google Scholar

Winkler, H. A. (1938). Rock-drawings of southern Upper Egypt; I. Sir Robert Mond desert expedition, Season 1936-1937: Preliminary report. (Archaeological survey of Egypt). Egypt Exploration Society.Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Etched in Stone: The Kevermes Stone Stela From the Great Hungarian Plain

- Waste Around Longhouses: Taphonomy on LBK Settlement in Hlízov

- Raw Materials and Technological Choices: Case Study of Neolithic Black Pottery From the Middle Yangtze River Valley of China

- Disentangling Technological Traditions: Comparative Analysis of Chaînes Opératoires of Painted Pre-Hispanic Ceramics From Nariño, Colombia

- Ancestral Connections: Re-Evaluating Concepts of Superimpositioning and Vandalism in Rock Art Studies

- Disability and Care in Late Medieval Lund, Sweden: An Analysis of Trauma and Intersecting Identities, Aided by Photogrammetric Digitization and Visualization

- Assessing the Development in Open Access Publishing in Archaeology: A Case Study From Norway

- Decorated Standing Stones – The Hagbards Galge Monument in Southwest Sweden

- Geophysical Prospection of the South-Western Quarter of the Hellenistic Capital Artaxata in the Ararat Plain (Lusarat, Ararat Province, Armenia): The South-West Quarter, City Walls and an Early Christian Church

- Lessons From Ceramic Petrography: A Case of Technological Transfer During the Transition From Late to Inca Periods in Northwestern Argentina, Southern Andes

- An Experimental and Methodological Approach of Plant Fibres in Dental Calculus: The Case Study of the Early Neolithic Site of Cova del Pasteral (Girona, Spain)

- Bridging the Post-Excavation Gaps: Structured Guidance and Training for Post-Excavation in Archaeology

- Everyone Has to Start Somewhere: Democratisation of Digital Documentation and Visualisation in 3D

- The Bedrock of Rock Art: The Significance of Quartz Arenite as a Canvas for Rock Art in Central Sweden

- The Origin, Development and Decline of Lengyel Culture Figurative Finds

- New “Balkan Fashion” Developing Through the Neolithization Process: The Ceramic Annulets of Amzabegovo and Svinjarička Čuka

- From a Medieval Town to the Modern Fortress of Rosas (Girona-Spain). Combining Geophysics and Archaeological Excavation to Understand the Evolution of a Strategic Coastal Settlement

- Technical Transfers Between Chert Knappers: Investigating Gunflint Manufacture in the Eastern Egyptian Desert (Wadi Sannur, Northern Galala, Egypt)

- Early Neolithic Pottery Production in the Maltese Islands: Initiating a Għar Dalam and Skorba Pottery Fabric Classification

- Revealing the Origins: An Interdisciplinary Study Into the Provenance of Sacral Microarchitecture–The Unique Case of the Church Model From Žatec in Bohemia

- An Analogical and Analytical Approach to the Burçevi Monumental Tomb

- A Glimpse at Raw Material Economy and Production of Chipped Stones at the Neolithic (Starčevo) Site of Svinjarička Čuka, South Serbia

- Archaeological Lithotheques of Siliceous Rocks in Spain: First Diagnosis of the Lithotheque Thematic Network

- Mapping Changes in Settlement Number and Demography in the South of Israel from the Hellenistic to the Early Islamic Period

- Review Article

- Structural Measures Against the Risks of Flash Floods in Patara and Consequent Considerations Regarding the Location of the Oracle Sanctuary of Apollo

- Commentary Article

- A Framework for Archaeological Involvement with Human Genetic Data for European Prehistory

- Special Issue on Digital Religioscapes: Current Methodologies and Novelties in the Analysis of Sacr(aliz)ed Spaces, edited by Anaïs Lamesa, Asuman Lätzer-Lasar - Part II

- Goats and Goddesses. Digital Approach to the Religioscapes of Atargatis and Allat

- Conceiving Elements of Divinity: The Use of the Semantic Web for the Definition of Material Religiosity in the Levant During the Second Millennium BCE

- Deep Mapping the Asklepieion of Pergamon: Charting the Path Through Challenges, Choices, and Solutions

- Special Issue on Engaging the Public, Heritage and Educators through Material Culture Research, edited by Katherine Anne Wilson, Christina Antenhofer, & Thomas Pickles

- Inventories as Keys to Exploring Castles as Cultural Heritage

- Hohensalzburg Digital: Engaging the Public via a Local Time Machine Project

- Monastic Estates in the Wachau Region: Nodes of Exchange in Past and Present Days

- “Meitheal Adhmadóireachta” Exploring and Communicating Prehistoric Irish Woodcraft Through Remaking and Shared Experience

- Community, Public Archaeology, and Co-construction of Knowledge Through the Educational Project of a Rural Mountain School

- Valuing Material Cultural Heritage: Engaging Audience(s) Through Development-Led Archaeological Research

- Engaging the Public Through Prehistory: Experiences From an Inclusive Perspective

- Material Culture, the Public, and the Extraordinary – “Unloved” Museums Objects as the Tool to Fascinate

- Archaeologists on Social Media and Its Benefits for the Profession. The Results and Lessons Learnt from a Questionnaire

- Special Issue on Network Perspectives in the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East and Eastern Mediterranean, edited by Maria Gabriella Micale, Helen Dawson, & Antti A. Lahelma

- Network Perspectives in the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East and Eastern Mediterranean

- Networks of Pots: The Usage of Ceramics in Network Analysis in Mediterranean Archaeology

- Networks of Knowledge, Materials, and Practice in the Neolithic Zagros

- Weak Ties on Old Roads: Inscribed Stopping-Places and Complex Networks in the Eastern Desert of Graeco-Roman Egypt

- Mediterranean Trade Networks and the Diffusion and Syncretism of Art and Architecture Styles at Delos

- People and Things on the Move: Tracking Paths With Social Network Analysis

- Networks and the City: A Network Perspective on Procopius De Aed. I and the Building of Late Antique Constantinople

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Etched in Stone: The Kevermes Stone Stela From the Great Hungarian Plain

- Waste Around Longhouses: Taphonomy on LBK Settlement in Hlízov

- Raw Materials and Technological Choices: Case Study of Neolithic Black Pottery From the Middle Yangtze River Valley of China

- Disentangling Technological Traditions: Comparative Analysis of Chaînes Opératoires of Painted Pre-Hispanic Ceramics From Nariño, Colombia

- Ancestral Connections: Re-Evaluating Concepts of Superimpositioning and Vandalism in Rock Art Studies

- Disability and Care in Late Medieval Lund, Sweden: An Analysis of Trauma and Intersecting Identities, Aided by Photogrammetric Digitization and Visualization

- Assessing the Development in Open Access Publishing in Archaeology: A Case Study From Norway

- Decorated Standing Stones – The Hagbards Galge Monument in Southwest Sweden

- Geophysical Prospection of the South-Western Quarter of the Hellenistic Capital Artaxata in the Ararat Plain (Lusarat, Ararat Province, Armenia): The South-West Quarter, City Walls and an Early Christian Church

- Lessons From Ceramic Petrography: A Case of Technological Transfer During the Transition From Late to Inca Periods in Northwestern Argentina, Southern Andes

- An Experimental and Methodological Approach of Plant Fibres in Dental Calculus: The Case Study of the Early Neolithic Site of Cova del Pasteral (Girona, Spain)

- Bridging the Post-Excavation Gaps: Structured Guidance and Training for Post-Excavation in Archaeology

- Everyone Has to Start Somewhere: Democratisation of Digital Documentation and Visualisation in 3D

- The Bedrock of Rock Art: The Significance of Quartz Arenite as a Canvas for Rock Art in Central Sweden

- The Origin, Development and Decline of Lengyel Culture Figurative Finds

- New “Balkan Fashion” Developing Through the Neolithization Process: The Ceramic Annulets of Amzabegovo and Svinjarička Čuka

- From a Medieval Town to the Modern Fortress of Rosas (Girona-Spain). Combining Geophysics and Archaeological Excavation to Understand the Evolution of a Strategic Coastal Settlement

- Technical Transfers Between Chert Knappers: Investigating Gunflint Manufacture in the Eastern Egyptian Desert (Wadi Sannur, Northern Galala, Egypt)

- Early Neolithic Pottery Production in the Maltese Islands: Initiating a Għar Dalam and Skorba Pottery Fabric Classification

- Revealing the Origins: An Interdisciplinary Study Into the Provenance of Sacral Microarchitecture–The Unique Case of the Church Model From Žatec in Bohemia

- An Analogical and Analytical Approach to the Burçevi Monumental Tomb

- A Glimpse at Raw Material Economy and Production of Chipped Stones at the Neolithic (Starčevo) Site of Svinjarička Čuka, South Serbia

- Archaeological Lithotheques of Siliceous Rocks in Spain: First Diagnosis of the Lithotheque Thematic Network

- Mapping Changes in Settlement Number and Demography in the South of Israel from the Hellenistic to the Early Islamic Period

- Review Article

- Structural Measures Against the Risks of Flash Floods in Patara and Consequent Considerations Regarding the Location of the Oracle Sanctuary of Apollo

- Commentary Article

- A Framework for Archaeological Involvement with Human Genetic Data for European Prehistory

- Special Issue on Digital Religioscapes: Current Methodologies and Novelties in the Analysis of Sacr(aliz)ed Spaces, edited by Anaïs Lamesa, Asuman Lätzer-Lasar - Part II

- Goats and Goddesses. Digital Approach to the Religioscapes of Atargatis and Allat

- Conceiving Elements of Divinity: The Use of the Semantic Web for the Definition of Material Religiosity in the Levant During the Second Millennium BCE

- Deep Mapping the Asklepieion of Pergamon: Charting the Path Through Challenges, Choices, and Solutions

- Special Issue on Engaging the Public, Heritage and Educators through Material Culture Research, edited by Katherine Anne Wilson, Christina Antenhofer, & Thomas Pickles

- Inventories as Keys to Exploring Castles as Cultural Heritage

- Hohensalzburg Digital: Engaging the Public via a Local Time Machine Project

- Monastic Estates in the Wachau Region: Nodes of Exchange in Past and Present Days

- “Meitheal Adhmadóireachta” Exploring and Communicating Prehistoric Irish Woodcraft Through Remaking and Shared Experience

- Community, Public Archaeology, and Co-construction of Knowledge Through the Educational Project of a Rural Mountain School

- Valuing Material Cultural Heritage: Engaging Audience(s) Through Development-Led Archaeological Research

- Engaging the Public Through Prehistory: Experiences From an Inclusive Perspective

- Material Culture, the Public, and the Extraordinary – “Unloved” Museums Objects as the Tool to Fascinate

- Archaeologists on Social Media and Its Benefits for the Profession. The Results and Lessons Learnt from a Questionnaire

- Special Issue on Network Perspectives in the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East and Eastern Mediterranean, edited by Maria Gabriella Micale, Helen Dawson, & Antti A. Lahelma

- Network Perspectives in the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East and Eastern Mediterranean

- Networks of Pots: The Usage of Ceramics in Network Analysis in Mediterranean Archaeology

- Networks of Knowledge, Materials, and Practice in the Neolithic Zagros

- Weak Ties on Old Roads: Inscribed Stopping-Places and Complex Networks in the Eastern Desert of Graeco-Roman Egypt

- Mediterranean Trade Networks and the Diffusion and Syncretism of Art and Architecture Styles at Delos

- People and Things on the Move: Tracking Paths With Social Network Analysis

- Networks and the City: A Network Perspective on Procopius De Aed. I and the Building of Late Antique Constantinople