Abstract

Museum-excavations – discovering unprovenanced and forgotten objects in museums’ storerooms – open new opportunities for engagement and highlight the consequent necessity to (de-)contextualise the discovered artefacts. Despite being unprovenanced – or even because of that – it is important to make sense of these “ordinary” finds. Developing strategies of unmasking the EXTRAordinary within such objects – an approach which I presented in my work Narrating the Extra the Ordinary has: “Re-excavating” objects in storage rooms of local museums as part of an archaeology of unloved objects as part of the workshop “Excavating the Extra-Ordinary - Challenges & merits of working with small finds” (JGU Mainz, 08–09 April 2019 – Zinn, 2019b) – and communicating them as part of imaginative activities for the wider public and the research community has been at the core of the described cooperative project, aiming at the literal and cultural (re-)discovery of ancient Egyptian artefacts. As Cyfarthfa Castle Museum and Art Gallery serves the local South Wales valleys, it was seen difficult to incorporate the Egyptian collection into the narrative of the museum’s permanent exhibition. The project brings these objects back to life by simultaneously creating different types of cultural representations via academic outputs, exhibitions, storytelling, a Museum of Lies, and artwork inspired by the items. All these methods centre on the materiality of the objects from which different meanings are drawn. This approach connects these objects with several identities in which they are placed. The engagement with all audiences/stakeholders proved crucial for the success of this project and leads to a sustainable interaction with neglected artefacts.

1 Introduction

Chinese Museums currently are experiencing a “museum craze” (Xia, 2023). The summer craze described in this newspaper article has not subsided after the summer break or the national holidays in October as I recently observed visiting 11 museums in Changchun, Xi’an and Guangzhou – giving anecdotal impression yet providing a good spread over the country. Tickets to many museums cannot be bought at the door but are released in batches online only via the WeChat App or websites and are gone within minutes. This practice introduced at the time of opening after COVID in January 2023 is still upheld due to the high demand of visitors wanting to come into museums. In China, the cause behind this craze unseen prior to COVID is a “growing fascination with traditional Chinese culture, particularly among young Chinese” (Xia, 2023). This comes in addition to a general interest in heritage and museums as I already had observed in 2000, 2016, and 2019 (this also reflected in academic discussions: Yan, 2018).

Museums around the world are not as lucky as Chinese museums. Even though we can state that museum visitors’ numbers of British museums picked up again over the last 18 months (Department for Culture, Media and Sport, 2023; Kennelly, 2023), they are still far away from the pre-COVID situation in the UK or the high percentage of general visitor numbers compared to population size we see in China. Even there are some exceptions to this trend (see the visitor numbers of the Museo Egizio in Turin, which had 853.320 visitors in 2019 – Ministerio della Cultura, 2019 – and 1,061,157 in 2023 – Museo Egizio, 2023), this raises the question what would need to be done or could be done in order to make the public and other stakeholders be interested in our heritage in general and material culture in particular in the first place? How would we then engage with them and convince them to engage with museums or other heritage institutions?

This article describes a collaborative project I lead between the University of Wales Trinity Saint David and Cyfarthfa Castle Museum, Merthyr Tydfil – a regional museum in Wales – that aims to bring unprovenanced objects back to life by creating different simultaneous types of cultural representations via academic outputs, Egyptological exhibitions, storytelling, a Museum of Lies subproject, and art exhibitions inspired by the objects. Achieving this aim would transform these objects, which currently lie dormant, from being “unloved” – as in not being (able to be) admired by audiences – into loved ones who receive attention by visitors. (Geoghegan & Hess, 2015; for more on unloved objects see Woodham et al., 2020). I was able to discuss these ideas with the authors at one of their collaborative workshops in 2015 leading up to this monograph which inspired me to introduce the Museum of Lies sub-project. This “unpacking the collection” (Byrne et al., 2011) will only be possible, let alone successful, when everyone involved will participate in the “networks of material and social agency” (Byrne et al., 2011, subtitle on cover page). This includes engagement practices with a wide spectrum of audiences driven by both the materiality of these artefacts as well as the emotional potential inherent in them. All activities as part of the Cyfarthfa Castle project focus on the materiality of the objects, but the different methods employed allow us to approach the meaning and understanding of them in different ways and with differing results.

2 Objects Within Material Culture Research

As an interdisciplinary field of studies, material culture research touches upon and borrows from many other disciplines. This can be a curse as one needs to be knowledgeable about many of them. On the other hand, this is also a blessing as it gives the researcher a wide toolset to explore material practices. Material culture studies also provide a methodology to research the interaction between objects – be it distinct objects or large groups of them – and humans. Even though material culture studies were sometimes praised as a model for post‐disciplinary research (Tilley, 2006), this view has rightly been called into question by Hicks (2010) in his recent overview about the Material Culture Turn. The field stays highly interdisciplinary, but the contribution of specific disciplines cannot be denied, especially when we think about the impact of engagement. Insofar, this study will look at both the physical form of objects as well as their social relations and meanings, which can be drawn from them in several encounters and disciplines. The material agency objects have will be seen as very important and should be used to engage audiences in the sense of drawing their attention.

The focus on the material worked alongside and sometimes against a linguistic turn applied especially in the humanities and led to a shift from a fixation on knowledge to a clear and constant interest in practice. This includes a negotiation between human and non‐human agency where both sides can be active and passive as described in the Actor-Network-Theory (ANT). Pickering (2010, p. 195) calls that the “dance of human and non‐human agency.” This human-thing entanglement (Hodder, 2011, 2012, 2016) highlights the interdependence between human and things and especially describes the notions of entanglements between things and humans as well as things and things (and the relevance of the latter for human engagement). ANT recently received more attention in Egyptology following the focus on Social Network Theory (Chollier, 2019; Stefanović, 2024) and the discussion of circumstances leading to technical change, which includes the manifold interactions between humans, things, and the environments in which they interact (Fitzenreiter, 2023).

Theoretically, the project described in detail below follows an archaeological approach of transcending boundaries that dissolves borders between academic disciplines and methodologies (Fahlander & Oestigaard, 2004, pp. 6–7). By default, Egyptology is theoretically better equipped to borrow and use ideas from other disciplines, as it already incorporates ideas from anthropology, archaeology, social science, gender studies, social history, art history, philology, and many more subjects (Langer, 2017, pp. IX–X). This helps to understand that objects relate to several social identities starting from the original setting of the object. Later, it is linked to each new habitat in which it is placed. As such, objects – being social actants in social processes – acquire and have operational ethnicity (Johannesen, 2004). Ethnicity as defined in this way is shifting and situational. Objects therefore are accumulating new identities in temporal and spatial perspective in the several stages of an object biography or life cycle. Artefacts have a life beyond their place or culture of origin, which includes their reception and modern heritage. These shifting life cycles of the objects, their method of acquisition by Western collectors in colonial situations as well as their current habitat far away of the original place of discovery also raises the need to think about colonial legacies. Despite this being immensely important and finally discussed in Egyptology (Matić, 2018, 2023; Langer & Matić, 2023 – for more literature see here), it cannot be discussed in the current article.

By promoting objects and engaging with them, new understandings are created. This proves the assumption of Kopytoff (1986, p. 68) that things have a cultural biography, which is not driven by “what it deals with, but how and from what perspective.” It is therefore legitimate to engage in research about each collector – with Harry Hartley Southey as the main one – and their connection to Merthyr Tydfil as part of Welsh heritage in addition to looking at the individual objects, their biographies and the insight into their temporality and special changes from their birth in ancient Egypt to their displaced setting in West Wales today. This interest culminated in a special exhibition about him in Cyfarthfa Castle Museum in 2017: Egyptomania! The Harry Southey Collection at Cyfarthfa Castle Museum and Art Gallery, March 21 – June 30, 2017. This exhibition in Cyfarthfa Castle was grounded in the research done on the objects coming out of the preceding annual pop-up exhibitions at the Lampeter Campus of University of Wales Trinity Saint David (UWTSD). This shows that objects not only are embedded with identity, they also can create identities as part of the engagement processes. Using their multivocal characteristics and emotional qualities, they trigger a process in which people set them in relation to themselves as individual, groups, or even large constructs like people or nations when dealing with these objects (Pocius, 2004).

The idea of operational ethnicity, the ability to create identity, and the accepted temporality of objects also mean that objects can leave the museum and unfold their potential in pop-up exhibitions, research in different settings or reception studies. By promoting them, one can create new understandings and play with the idea of human-object-entanglement that can be renewed or invoked at any time and in any new setting (Hodder, 2012). In doing so, the objects are rising beyond being misplaced and unloved by wider audiences due to not being seen, and are able to fulfil their “potential of connecting people and events over time and space” (Herle, 2012, p. 295).

3 Unprovenanced, Forgotten Objects

This section needs to start with a disclaimer. When I talk about objects being forgotten or neglected, then I say this purely from the perspective of a yet to be realised object–audience engagement owing to the fact that the objects are kept in the storerooms for several understandable reasons. It must be stressed that this does not imply in any way that they are not being adequately cared for by the museum.

The overarching co-operative project between Cyfarthfa Castle Museum, Merthyr Tydfil, Wales and the University of Wales Trinity Saint David – led by myself – started in 2011 as a “museum-excavation,” discovering unprovenanced and forgotten objects in this museum’s storerooms. Excavating as action brings both things and ideas to light and enables us to examine past items here and now and assess their relevance for the present and ideally for the future.

What came to light as secondary archaeology in the museum storerooms were Egyptian objects among others. Some information about them could be gained from the past ledgers. Being a community museum, this regional museum represents the daily life and history of the local South Wales valleys, explores the local creativity, visual and public culture, and shall provide – flexible – exhibitions and public engagement programmes within the specific community setting. Insofar, it was seen as difficult to incorporate the Egyptian collection into the narrative of the museum’s permanent exhibition. How could we combine the state rooms in which the owners of the mock castle – the Crawshay family – lived (Zinn, 2017a, pp. 693–694), downstairs rooms showing the area’s mining history, living conditions of the staff, and Hoover washing machines as well as special exhibitions about Rugby combine with the “oriental objects” mostly hidden away in boxes in the storage rooms and therefore, forgotten (Zinn, 2019a, esp. pp. 171–173). Even though these objects were not exceptional in regard to the fact that all museums have large parts of their collections in their storerooms and not on display, they nevertheless deserved better. Seen from an audience perspective, ancient Egyptian artefacts always have the potential to engage as there is a general interest in the mystery of Egypt. Why not use that point to kickstart a development from dormant objects destined to be “unloved” by audiences, as they do not know about them, into loved ones who receive attention?

This contrast between the local and the being-brought-in as well as the being-of-interest and the forgotten is even more highlighted as the Egyptian objects at Cyfarthfa Castle are what Stevenson (2019, p. 1) calls unassuming objects being scattered. We know that they were bound into the circulation of material culture in the colonial context of exchange and the drive to collect in order to build up private collections at the end of the nineteenth and the beginning of the twentieth centuries AD. Exchange in a colonial context means that the material culture was being taken rather than exchanged as gift – an action, which now would be seen as an art crime (Brodie et al., 2001; Campbell, 2013). This, however, already describes the extent of the knowledge about these unprovenanced objects. Following Joyce (2012), provenance is here understood as the history of ownership and circulation of an artefact at potentially all stages of the object’s life-cycle as opposed to provenience, which traditionally is seen as a fixed point of the first origin or find situation or provenance studies, which include the act of relocation from its place of origin to the location at which it was recovered, but nothing beyond (Kolb, 2020, p. 8962). As such, provenance includes the temporal trajectory of layered lives of objects in their different habitats they inhabited up to the current point. Habitat here can be seen as temporally or spatially different – or both. I see this trajectory as an important framework for an object biography. New habitats or situations in which the object is placed always add a new or altered layer of meaning without making previous ones – if known – obsolete. As it will be shown below, my work with artefacts and audiences proves the ideas of the ANT that objects have agency (Latour, 2005). When applying ANT to material culture studies and archaeology, Knappett (2005, 2008) argued that for this to happen, two conditions should be considered: agency is to be understood being relational and often asymmetrical and objects – the material culture looked at in this work – is able to influence and transform human understanding. This idea is used by granting the objects to be the driving force in their revival and unlocking emotional responses from the human actors.

In the case of the Egyptian objects of Cyfarthfa Castle Museum, no archaeological context such as find spots or excavation situations was known and, in most cases, not even when and how the artefacts came into the museum, let alone any layer in between (Zinn, 2017a). These orphaned objects were not only displaced, as they were lying dormant, but they were also forgotten and neglected, disconnected from any audience. Such museum objects with no or inadequate information about their origin or archaeological evidence often provide a considerable challenge for the museums. Originally, museums worried about how to present objects and deliver adequate explanations. Later, the issue of authenticity was added. This led, especially in smaller museums with non-specialist curators, to the fact that objects were banned to the storerooms as it happened at Cyfarthfa Castle. Over the last 50 + years, it has become clear through many examples that the research value of such collections is nevertheless too important for them to be neglected. However, recent awareness for and discussions about illicit looting called for not researching or publishing unprovenanced existing museums’ collections in order to decrease the potential value attributed to them and to prevent illicit artefact trade. I find this point of view in general highly debatable as it de facto presents a case of unsustainable heritage practice and furthers loss of heritages. Provenance has in many cases become “one of the primary mechanisms for determining the legal status and authenticity of a cultural object” (Gerstenblith, 2019, p. 285). This can be helpful with detecting illicit objects currently offered on the antiquities market but does not help the situation of orphaned artefacts, which already have for some time been part of museum collections.

While it is often stated that “re-establishing the context of these objects by scientific research proves to be the best option for museums” (Al Saad & Azaizeh, 2023, p. 75), I would argue that it is the knowledge about what fascinates audiences, which opens strategies for reconnecting material culture with all stakeholders as this triggers the engagement with them.

Despite being unprovenanced – one could even say especially because of that – it is important to make sense of these often “ordinary” finds. Museum-excavations with the following interventions open new opportunities for engagement with the public and shed new light on the consequent necessity to (de-)contextualise the discovered artefacts.

4 Status Quo – Things in the Storeroom

Behind the scenes at museums the world over are thousands upon thousands of artefacts. These objects, removed from other lives, other places, other times, are neatly labelled, catalogued and packed away out of sight, rarely displayed and infrequently studied. The processes by which these collections are formed remain obscure to many visitors and creator or source communities alike, perhaps because of their ubiquitous presence in the museum environment (Byrne et al., 2011, p. 4).

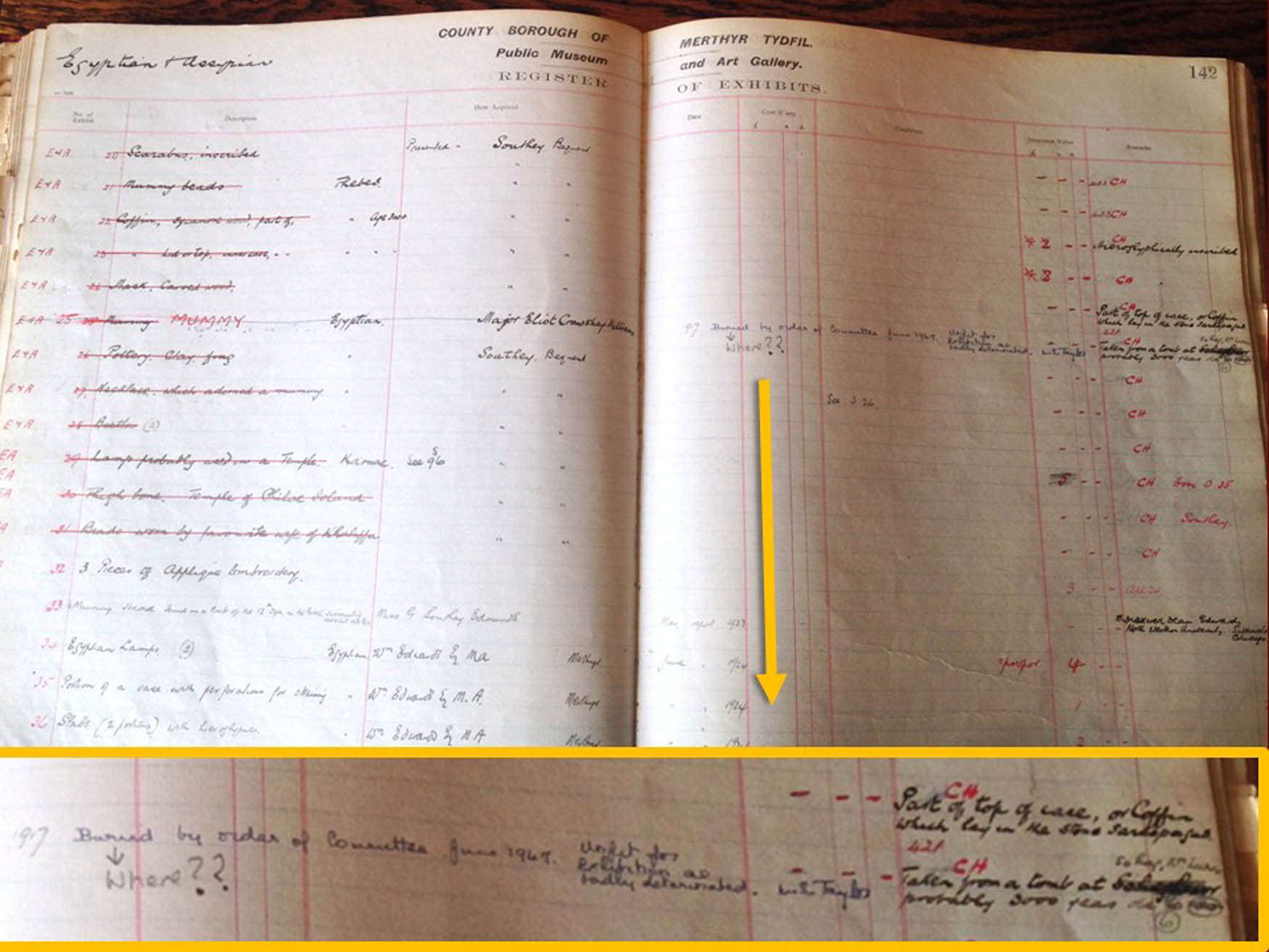

When the project started in 2011, very few Egyptian objects belonging to Cyfarthfa Castle Museum have been visible in the permanent exhibition over the decades since the first opening of the museum. Audiences – potential ones and even visitors already coming into the museum – did not know about the collections. Even though the Egyptian artefacts were added to the database in the 1990s and 2000s, current curators were not necessarily familiar with all objects in the relevant boxes in the storeroom. As a first step of engagement, we – the curators, myself and some of the participating students – literally unpacked all the boxes, discussed the objects, added data to the very sparse information in the database and compared them with the old ledgers, which were holding information which the colleagues compiling the database obviously did not see as important or maybe academic enough and therefore left out. Comments in the ledger such as (Figure 1)

EA 25 – Mummy Egyptian – Major Eliot Crawshay Williams 1917 – buried by order of Committee. June 1947. Unfit for Exhibition as badly deteriorated. M.S. Taylor → Where??

Ledger Cyfarthfa Castle Museum.

allow further insights into collecting and collection practices and are vital for applying modern approaches or practices to and with the objects. Objects are very often bound into layers of histories and interactions as wonderfully complicated entanglements with people and other things. Understanding these layers can capture objects “in and out of context” (title of a session at EAA 2022 in Belfast to which I contributed) and beyond traditional academic object biographies. These movements across time and space, of which objects have been a part, can therefore be re-defined, making it easier for the artefacts to (re-)connect with audiences. Just like a human CV which brings a name alive in a job application, these direct or unidirectional layers open up potential interactions with possible audiences.

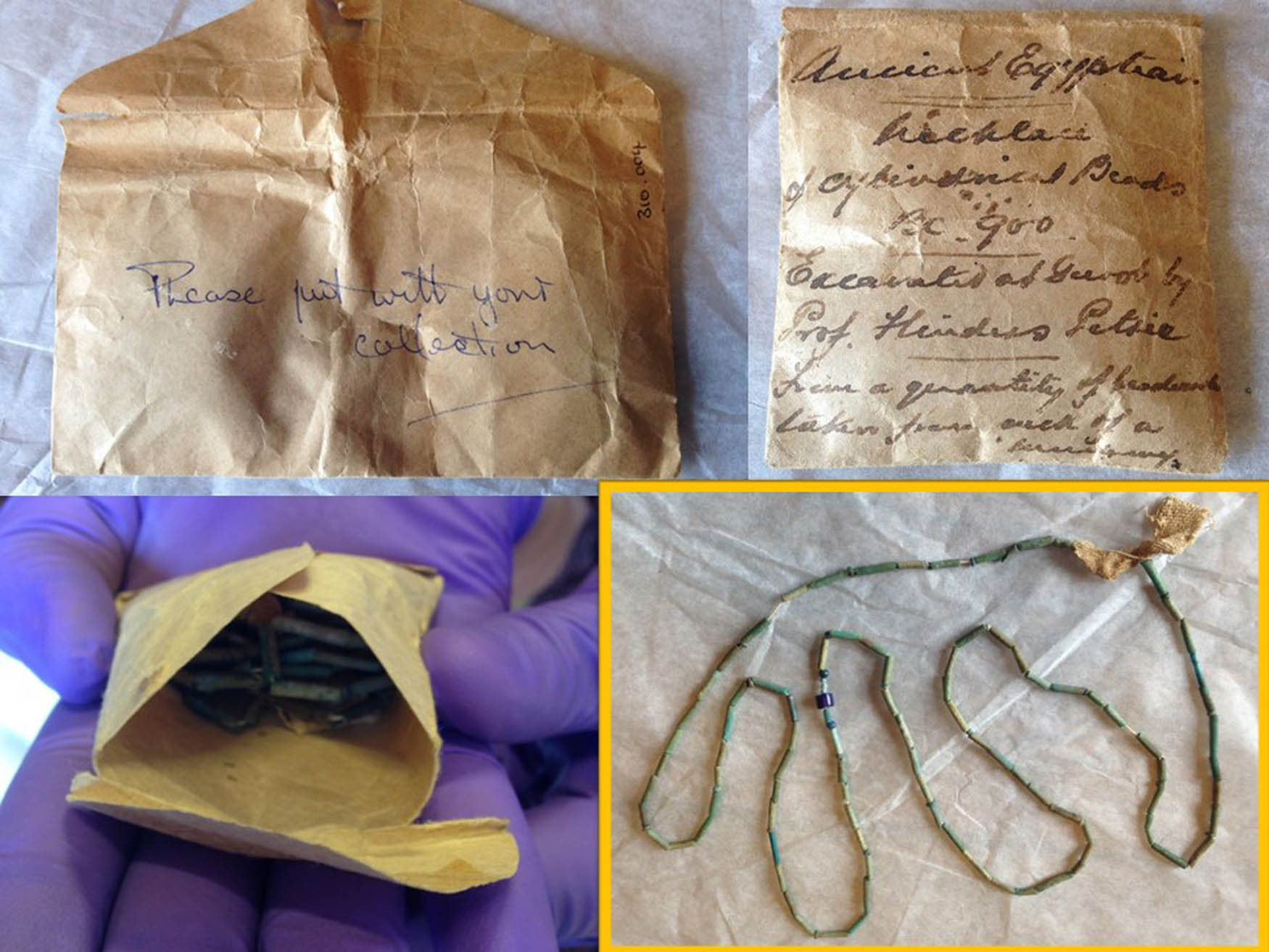

This is best explained with the example of the faience bead necklace CCM 310.004 (Figure 2). This single stranded necklace of blue tubular faience beads – likely re-strung in modern times – is in the collection as part of the assemblage of the necklace within two brown envelopes. The first, square envelop has the note: “Ancient Egyptian Necklace of cylindrical beads BC 900. Excavated at Gurob by Prof. Flinders Petrie from a quantity of beadwork taken from each(?) of a cemetery(?)”

Faience necklace CCM 310.004.

This envelop was likely the original packaging of the beads when they were acquired in Egypt. It was placed in a second one with the note: “Please put with your collection.” The fact that the latter received the new inventory number in 2004 shows that the museum staff at that time considered the assemblage as one object. Tubular beads are known from all periods of Egyptian history. Many were found scattered in tombs, possibly belonging to broad collars (see as example New York, MMA 40.3.2, Broad Collar of Wah) or bead net dresses (such as Boston MfA 27.1548.1), and were restrung after excavation (see string of tubular faience beads New York, MMA 14.7.97). The allocation of these beads to Petrie provides a second layer. We know that he excavated in Gurob for several seasons (1888–89, 1889–90, 1903–04, 1919–20, 1920–21). Artefacts from the later season were redistributed after WW2 by Hilda Petrie, having been stored at University College London before (Griffith Institute, 2018). Oral communication with staff in the Cyfarthfa Museum hints towards such an event. These two examples show that the later life cycles of museum objects can be equally interesting as the object itself and add to the story to tell about them.

This was the first step in the quest to overcome the alienation between all partners of the network: curators, stakeholders, audiences, and the objects, which all faced barriers. Even though barriers have been a much-discussed topic in museum studies over the last few decades, the discussion usually circles around several factors such as overcoming of spatial obstacles (finding the museum and navigating through the museum/collection – Davies, 2001), impediments for people with disabilities or special needs (mobility, hearing and visual impairment, autism, specific age groups, etc. – Murphy, 2015; Anderson et al., 2015; Bradbury & McVicker, n.d.; Research Centre for Museums and Galleries, 2024), so-called attitudinal barriers to museums (Desai & Thomas, 1998; Research Centre for Museums and Galleries, 2020), or the interrelationship of museums with other institutions with which they share responsibilities (as example education – see Luke & McCreedy, 2012).

The specific barrier, we faced at the starting point of the project is often not understood as such, despite it seemingly being an obvious one: The disengagement between audiences and forgotten, unloved or hidden objects (Zinn, 2018b). Audiences (or in some cases even museum staff) know nothing of such objects in their museums as they are out of sight, tucked safely away in storage rooms and often not fully – if at all – catalogued. This could be seen as an obstacle for accessing the full range of artefacts available in the museum as well as building up potential audience–object relationships.

Such a situation is unfortunately more common than assumed, even outside of small, non-specialised museums. Large museums put their focus on object groups that deliver a clear and comprehensive narrative, either because they derive from a secure archaeological context or are known – or assumed – to draw visitors in. Museums focus on valuable or jaw-dropping artefacts as an object type because they are often already known to audiences. They were then publicised to motivate visitors to come into the museum because of their power to play with public imagination. Consequently, audiences often assumed such objects to be on display, an expectation sometimes shared by museum curators. This creates a cycle that excludes lesser known or forgotten objects. It is only recently that curators have realised that even seemingly unassuming, lacklustre, or humble artefacts can entice audiences once their story catches the public’s interest (Kilian & Zöller-Engelhardt, 2021).

Very quickly after starting the project, I decided not only to deal with the material object in an academic Egyptological way, but also to trace the relationship between the physical object and humans, be it on an individual or institutional level. I wanted to see how people are attracted by and to objects and how they make sense of the world around them through tangible objects, involving other people.

5 Becoming Mobile – Preparing the Ground

Being mobile – or expressed differently: having been on the move – is a familiar sensation for these objects. All of them were “misplaced” both in space and time. “[W]hen things move, things change.” (Spitta, 2009, p. 3). This simple yet fitting expression given by Silvia Spitta when tracking the distribution of South American objects all over Europe and North America shows that misplaced objects are in greater danger of being forgotten because information gets lost, objects as well as their perceptions change. It is therefore more difficult to (re-)connect them with audiences, to negotiate this change between object, place, time, and visitor. In this case, the necessary process of reconfiguring the object within the new space – foreign in a geopolitical and cultural sense – is often impeded or in the best case delayed: “[e]very new cultural configuration and therefore every subject position depends upon transcultural processes.” (Spitta, 2009, p. 21). The creation of a new and ready “receptor culture” (Spitta, 2009, p. 21) often did not take place as these objects were deemed too alien or strange by curators who saw themselves incapable to offer valid explanations. Therefore, the objects were hidden away in boxes in the storage rooms. This robbed them of the chance to make a potential impact. The process is even more relevant in smaller or regional museums with only one – if any – curator overseeing all areas and expected to cater to a certain public. Such hidden away collections are even more at risk than others and the objects often face the threat of deaccession because they seemingly do not have a story to tell within their immediate local environment.

Borrowing an often-cited principle of Homeopathy – similia similibus curantur, which means like cures like – we decided to take the objects out of the home museum (Cyfarthfa Castle Museum) on the move again and prepare them together with students of the University of Wales Trinity Saint David – 75 miles to the Northwest of Merthyr Tydfil – for annual and changing pop-up exhibitions in Lampeter (West Wales).

What was somewhat anecdotally experienced in the Cyfarthfa Castle project was then in 2021 argued with more examples – mainly from the viewpoints of science museums and botanical gardens – in the edited monograph “Mobile Museums: Collections in circulation” (Driver et al., 2021), exploring the importance of circulation in the study of past and present museum collections. Taking the Cyfarthfa objects out again would be their re-mobilisation. In our case, it would not be in the context of indigenous community engagement as is mostly the case in other examples (Driver et al., 2021, p. 1), but as part of an engagement with diverse regional and academic audiences aimed at reviving the objects by creating object–audience interactions, and by doing so challenge uses of museum collections in times of economic challenges. By making the object mobile again, the radius of what counts as local or regional expands. This also extends the possibilities of local creativity, visual and public culture to tap in. Taking the object out of the museum offers new spaces for – now fully flexible – exhibitions and public engagement programmes within the extended community setting. This embedded the objects with additional meaning and value and therefore, influenced the interpretation once they returned to the home museum.

6 Doing Things with Things: Engagements

“This is not to over-dramatise the role of things, since the choice to use this term was made on the assumption that, by definition, ‘things’ are non-special and mundane, but merely that which makes up the physicality of the everyday.” (Attfield, 2000, p. 9)

Once the objects were received in Lampeter, we methodologically focused simultaneously on a theoretical and a practical level, by thinking or researching and making.

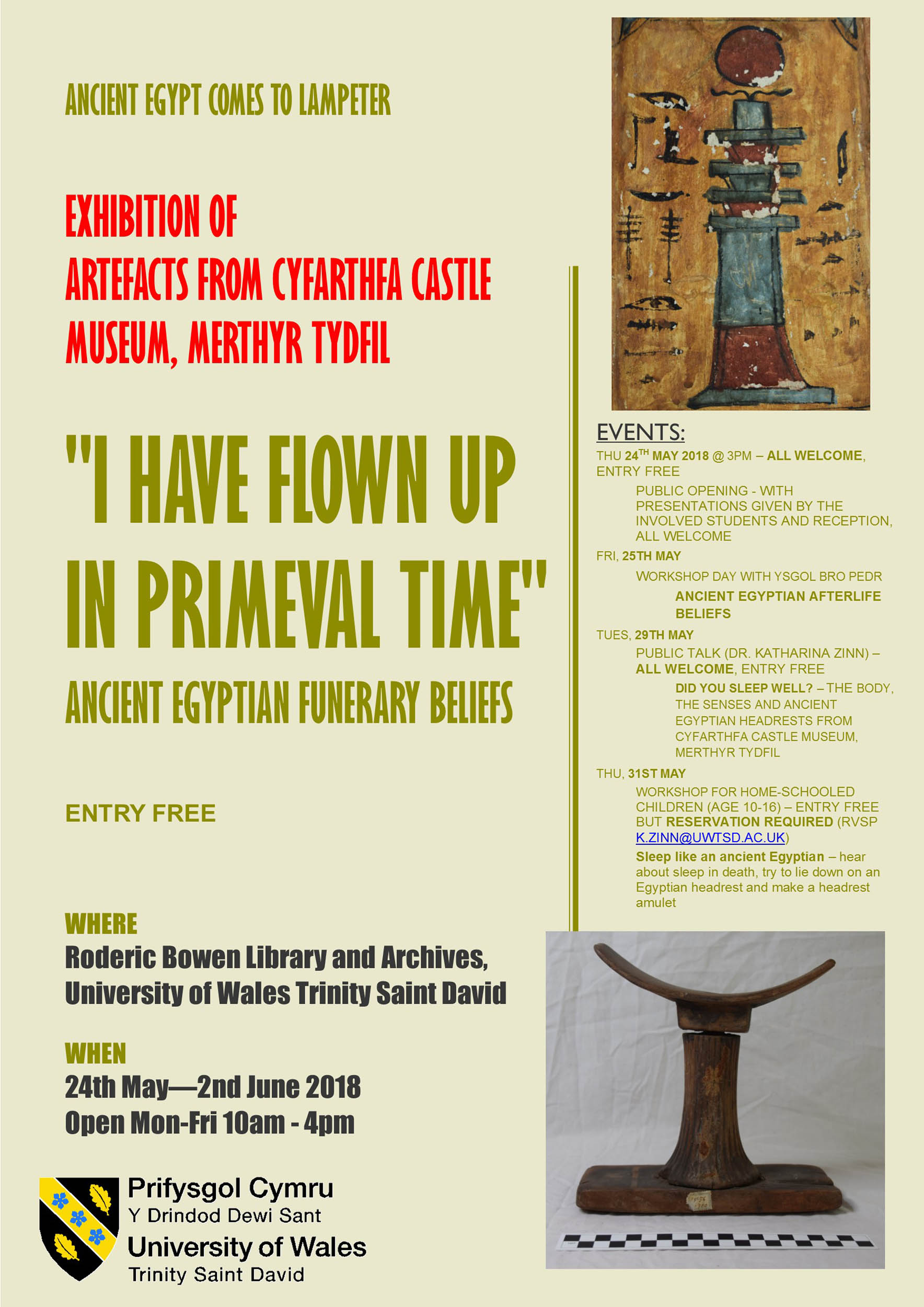

This process began with the incorporation of objects from the museum into Higher Education teaching activities at Lampeter as curricular activity for second- and third-year BA students from the academic year 2011/12 onward – representing researching and learning. Students and staff researched 5–10 objects per year. It was planned from the beginning to offer the students an extra-curricular pursuit of setting out a pop-up exhibition, which already happened – albeit in a very small scope – since 2012. This allowed learning and skills acquirement beyond academic activities. The pop-up exhibition had a vernissage and finissage, public talks, and student-led engagement workshops with local schoolchildren. As Wales does not include Egypt in the primary or secondary history curriculum, we decided in discussion with teachers to offer Egypt as an example of afterlife beliefs as part of the subject Religious Education. From 2013 onward, we also provided activities for local home-educating networks. This guaranteed a presentation of the objects to and an engagement with a wide audience from the beginning. Even though this was a learning curve, we were able to improve from year to year. A very important point however was that the second level engagement beyond the involvement of the students as part of their module was planned as a corresponding activity from the very start. This combination allowed a comprehensive education and skills development for students of several degrees and at the same time best fulfilled the heritage/museum studies approach. The project in general and this dual method in particular were seen as unusual and therefore, recognized in the local newspaper (Students, 2012).

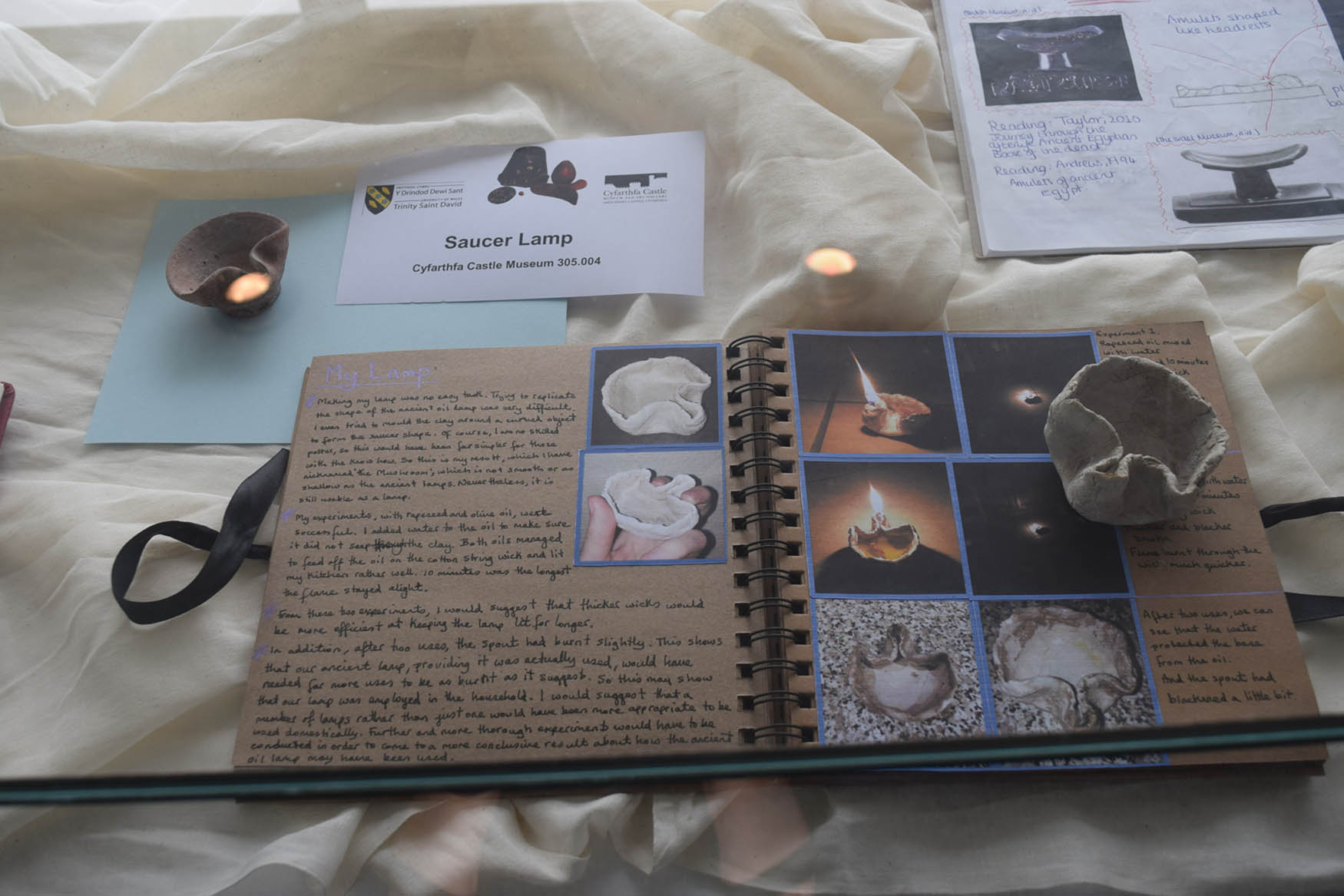

The student involvement alternated between two modules: one centring around funerary beliefs in ancient Egypt and the other one on gender issues. These modules prepared the students for academic interpretations of the objects. They were asked to write an academic catalogue entry as their final module assessment, which needed to be directed to a wide, non-academic audience as part of the later catalogue of the exhibition. Other forms of the assessment portfolio were either the design of an academic poster to be exhibited with the artefacts or the preparation of a talk (presentation) to be given at the vernissage. These assessments were prepared in workshops and handling sessions where the students worked in groups together and with the staff, while writing their assessments on their own. This form brought a lot of synergies and allowed results beyond BA level. From the academic year 2017/18 on, I introduced an additional form of assessment – the scrapbook. That was meant as a sustainable research journal leading up to the catalogue entry since many students misplaced or lost their notes from the workshops and constantly consulted myself or peers about the discussion already had. The unexpected outcome was that the students designed the scrapbooks as real pieces of art or objects in their own right. As a result, we started to display them with the objects as part of the exhibition (Figure 3).

Scrapbook in exhibition.

Academic routes of engagement also included publications, using the act of publishing as one way to make the objects public and rouse interest. In addition to the above-mentioned annual catalogues and posters, we have publications by staff (Zinn, 2016, 2017a, b, 2018a, 2019a) and students (Elliott, 2014) as well as several presentations at international conferences. Outcomes of the student research were also presented at Posters in Parliament in 2015 (Sophie Millward and Robert Edwards) and 2023 (Deborah Mercer and Kurtis Williams), after these students won the internal competition to take part.

One of the main aims of the project was that students and staff went beyond traditional object biographies in the subsequent extracurricular activities while preparing the actual pop-up exhibitions in Lampeter. We offered a vernissage open to academics, students, and the local community as well as the families of the participating students coming from all parts of the UK, making the project as well as the museum and its objects known far beyond Lampeter and Wales. On these occasions, students presented their 5 min talks about each object and visitors could ask questions after reading the posters. During the running time of the exhibitions (usually about 10 days), we offered guided tours combined with handling sessions. This getting eye-to eye with the objects fostered the feeling of belonging and interconnectivity between objects, audiences, and places (where it all happened – Lampeter – as well as the location of the museum – 75 miles afar in Merthyr Tydfil plus Egypt as the place of origin). Belonging here can be understood in two ways: in the double sense of the I get acquainted or take emotionally possession of these objects (they “belong” to me as I formed a connection) and feeling part of a wider network/group (I belong to a community) (Modest, 2019, p. 15). It was interesting to see how all these different groups defined for themselves how and why these particular ancient Egyptian things presented by a German Egyptologist mattered. This included different audiences: English students in Wales, rural Welsh communities who often had not yet experienced the world outside Wales (both in a spatial and temporal sense), discussing the controversial question of connecting north and south Wales (a unique differentiation in the perception of Welsh people without anyone being able to say where this “border” would lie), parents and grandparents of participating pupils, students who had never been in a museum before, and many more. More members of the local community became interested by seeing the exhibition posters distributed at crucial places around the town and the county (Figure 4). They all felt included and became interested (Figure 5). These pop-up exhibitions fulfilled new priorities museums are facing such as participation, social justice, and maybe even activism; they functioned as public space and became one potential case study proving the participatory turn (Eckersley, 2022, esp. p. 19).

Poster exhibition 2018.

Engagement activities.

The exhibitions – together with the adjacent outreach activities – focused on creating stories and slightly different narratives around the objects. In the first years, we aimed to teach students with the help of this extracurricular activity how to engage with visitors and to draw them into the exhibition. In the second year, we combined this with outreach sessions with year 8 pupils (aged 12–13) from local schools. They visited the campus in whole year groups (up to 150 pupils at a time) and participated in student-led workshops in smaller groups. This participation was part of their curriculum Religious Education. As Wales has a high percentage of home-educated children, we also offered sessions for home-educated children. We run several parallel workshop classes: a guided tour through the exhibition, performance of ancient Egyptian rituals (daily cult ritual or the Opening of the Mouth) following a script, making Egyptianising artefacts from air-drying clay (pyramids and scarabs) and “mummifying” teachers and fellow pupils. These classes were taught by our students who took their academic research to new horizons and could apply their knowledge in completely new settings trying and succeeding to interest the pupils.

This playing around with things helped to unearth curiosity and to develop new ideas about how to deal with non-cared-for objects. Interestingly, the objects, which students originally had dubbed as “boring” after having seen the objects on photographs taken prior to the module, became very interesting when being looked at differently. These images followed the rules of archaeological photographs (Fisher, 2009) rather than aiming at a potential emotional connection as artistic images do. Sometimes it was enough to deliver a different, more emotionally touching creative or artistic photograph instead of the archaeologically correct one (Figures 6 and 7; Cartonnage Mask CCM 331.004) to interest the students. Seeing the objects themselves and handling them opened further viewpoints. In other cases, we engaged with them differently. Students emotionally connected with the objects, so that the “damaged old thing” (comment of one of my students) had become a charismatic object (Wingfield, 2010); proving that artefacts far away from being “star objects” (Wingfield, 2010, p. 55; such as the Buddha in the Birmingham Museum) can also be perceived as charismatic. They were no longer simply culture-bearing objects which stood in for distant people and places, which would have fascinated in the Victorian and Edwardian Period (Plotz, 2008). They also created a sense of self and community in a new location here and now as well as the new group and started a new process to become culture-bearing. Insofar, they are an interesting example for Johannesen’s (2004, also mentioned above) idea of operational ethnicity (for a discussion of the concept of identities in archaeology, see Insoll, 2007). Due to the formed bond emerging out of the engagement and the story coming with the object, the students – and later the audiences – felt enchanted and as a result valued the objects differently. They had become curious, wanted to know more, and wove further stories, which created more curiosity.

Cartonnage mask CCM 331.004 archaeological.

Cartonnage mask CCM 331.004 creative.

By using academic knowledge and creating a new setting, new parts of the object biography appeared in the form of extended narratives which helped to refocus on the object. This is especially important when the provenance and traditional archaeological context are missing. In doing this, we proved Tim Ingold right who described the twenty-first century as a storied world to live in (Ingold, 2011, esp. pp. 141–176). For him, stories and life belong together. Through storytelling, the past is pulled into our present experiences and connected as our experiences deliver a new side of the story. In this context, past and present are continuous and generate a future (Ingold, 2011, p. 161). To achieve the goal of combining as many narratives as possible connected to each object – academic and beyond – I decided to be serious about the seemingly frivolous and frivolous about the serious – the latter interestingly being defined by my students as the academic. This meant to use our academic knowledge and to add creative interpretations. It is described below that the confidence to include creativity increased over the years until it became one of the main aims of one of the sub-projects. Creating a new habitat for the object by putting it in a new setting formed by new narratives helped to re-focus on the object.

To avoid misunderstanding, I would like to add a disclaimer: Any of the creative ideas and engagement should not be understood as attempting to replace the academic research. The latter will remain the necessary “bread and butter” of work in a museum, but it will be enhancing by the creation of new stories.

This storytelling already began with the placement of the objects in the exhibition cases once they arrive at the Lampeter campus. As the objects were in sight in a secure environment, students were able to see them when they wanted, to think about them, to add additional materials, and to work toward the catalogue entry. Throughout the module, I ran specific sessions handling the objects. Beyond that, I offered experimental and experiential archaeology sessions in which the student could create replicas, test theories about making and more. The faces of the audience say it all (Figure 8). This proves that the object is a magnet in this context. Following the premise that humans depend on things (Hodder, 2012, pp. 15–39) and things depend on humans (Hodder, 2012, pp. 64–87), we need to think differently about things, understand their potential to create entanglement and engage with this ability. Once applied, it opens several engagement routes and connects audiences and objects (Figure 9).

Making funerary cones.

Entanglement.

After realising these developments, we started with one particular object which the students had dubbed as “boring” or “lackluster”: the slightly damaged miniature offering plate or dish CC308.004 (Figure 10). The spherical dish is a red coarse ware pottery bowl made from completely fired through un-slipped Nile silt. It is 5 cm in diameter and 1.4 cm high. It does not show any sign of having been treated with a semiliquid clay – called a slip. It is hand moulded with a level, yet not completely flat base and an unmodelled, partially broken rim. Miniature vessels were used as votive offerings throughout Egyptian pharaonic history from the earliest times onward and can be found throughout Egypt. The form of these vessels ranges from dishes and pots to bottles and jars. Dishes such as CCM 308.004 were placed in tombs or formed part of foundation deposits (Zinn, 2017b). A thorough academic description and interpretation had already revealed how interesting such a small artefact can be, but the real fascination was created by different activities centring on this dish. In addition to the inclusion in a special exhibition about food as part of an international symposium (Embodied Encounters: Exploring the Materialities of Food “Stuffs,” 20–22/05/2014), I created a 10-week seminar (second- and third-year BA students) around this object, which comprised general archaeological topics such as context, dating, documentation (such as drawings), food in ancient Egypt, religious symbolic meaning of such dishes, etc. This also included creative sessions following Tim Ingold’s approach of making. We were making a similar dish with clay after experiencing that the original was hand-formed. This became clear while handling the plate as it fitted perfectly into a medium sized hand such as most women’s hands or a small male hand. This was the first step towards realising the entanglement between the dish and its original maker, which also incorporated the contemporary handling person as part of an extended process of handling. The newly made replica dishes were present in each session and used in further activities such as experiencing the application of slips, writing on them or – during the last seminar – the performance of an execration ritual for which we wrote the name of an “enemy” (a fictional person or a hated or uncomfortable situation) on them, which was magically obliterated by smashing the dish. Before this happened, the students transported the dishes into the present day by placing chocolate Easter eggs on them as the session took place on the last day before Easter. These are some of the initiatives I implemented as tailored examples established in and aimed to be situated within Higher Education teaching (for examples for teaching Egyptology in museum pedagogy please see Thum et al., 2024 or the upcoming book Teaching about the Ancient World in Museums: Pedagogies in Practice by the same editors).

CCM 308.004.

Storytelling here functioned as re-enactment. A second line of inquiry to this experimental and experiential archaeological enquiry followed even more the experiential route. The dish was the starting point of an outreach event: an academic talk and a practical food preparation and eating session entitled Food for Thought: Eat like an Egyptian (Rhywbeth I Gnoi Cil Drosto: Bwyta fel Eifftiwr) as part of the annual Lampeter Food Festival in 2015.

The author is fully aware that such an extensive treatment of one object cannot often be repeated, but it was a necessary and fabulous learning curve. It set the expectations and aimed for experiences to push forward the project activities outside the immediate university teaching and learning environment. Being able to explore the transition from a “boring and featureless” thing into a loved and well-remembered object stimulated new ways of thinking and more confidence to push the boundaries of traditional exhibitions. Taking the objects out of the actual museum relieved the participants of some restrictions placed on them in the traditional museum setting. While upholding museum security standards for their safeguarding, we were able to create manifold new ways of research and activities around it to facilitate interesting annual pop-up exhibitions of only 5–10 objects.

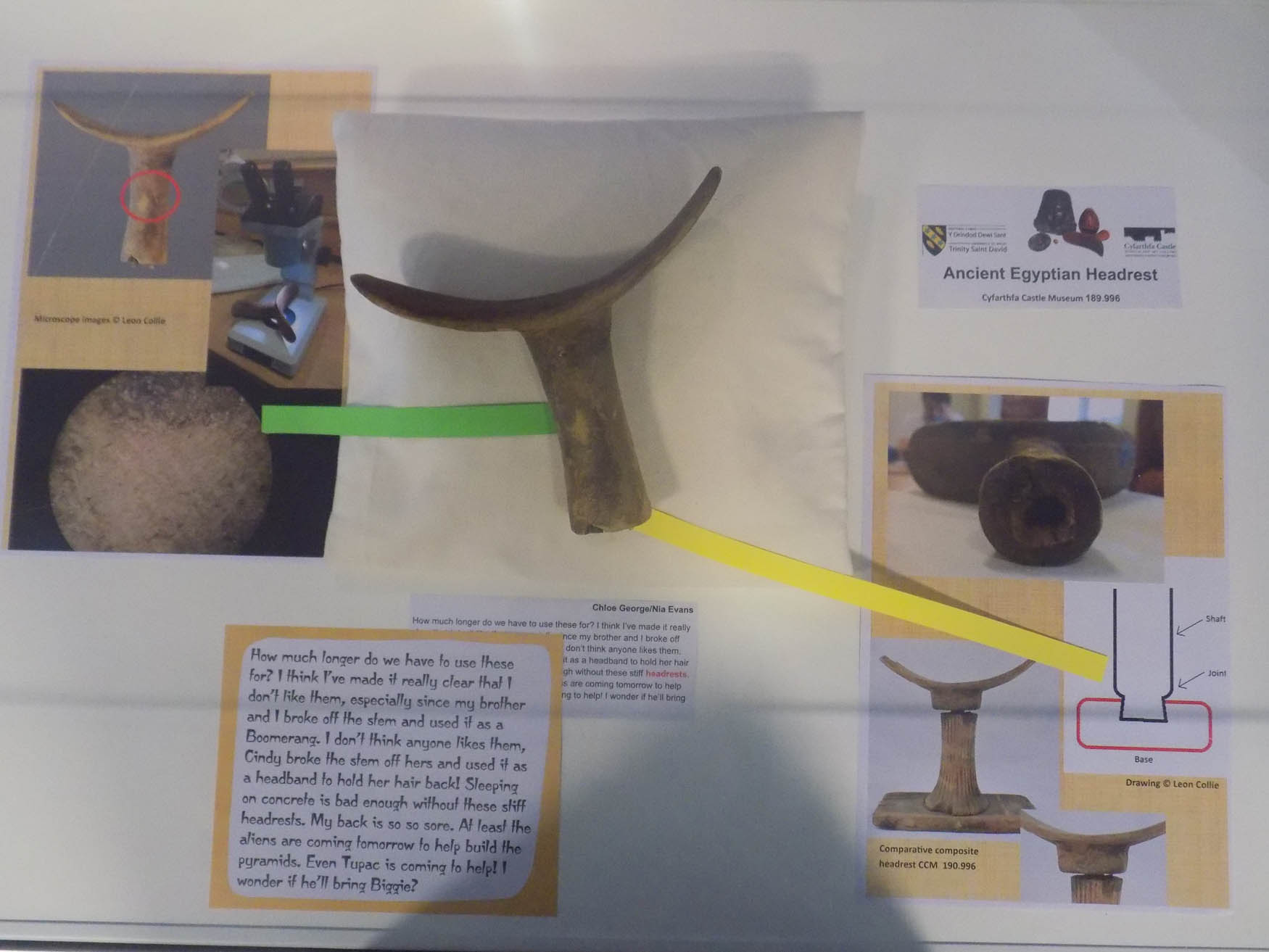

The next step in developing a strategy for how to care for these objects and how to bring them back into the lived memory of their potential audiences was exemplified by looking more closely at two previously unpublished and unprovenanced headrests in the collection (Zinn, 2018a). CCM 189.996 is an incompletely preserved headrest made from a low-quality local soft wood. The nevertheless well-made and well-proportioned headrest originally consisted of three parts that were tenoned together with a long crest, a slender column, and the now missing base. Compared to the first headrest, CCM 190.996 was made of a higher-quality hard wood and features a wide rectangular base, a fluted or ribbed structure of the pedestal or shaft and a crest on a small abacus. While different in appearance, both reveal either imprints of fabric at one of the longer outer edges of the crest or patches of linen stuck on the columnar with resin. The existence of these fabric patches and imprints drove the research on these two headrests, combining academic research and museological approaches as well as looking at their impact on visitors. These fabric patches indicate the feasibility of using headrests to sleep on. This was explored using sensorial approaches within anthropology and their application to archaeology. The unusual form of the headrest heightens modern Western audiences’ curiosity about the practicality of sleeping on them as pillows. Making a headrest replica with a carpenter (Steve Parsons), which could be used for lying down in outreach sessions, was the starting point for new experiences and discussions removing the borders between ancient Egyptian objects usually tucked safely away in museum cases and the curiosity of potential audiences. We tested if lying down on the headrest was comfortable and if the form of the headrest was enough to achieve that or if padding – see attached linen and its imprint – might help. This was not only great fun and a considerable learning curve for all participants (Figure 11), but it also helped to indicate how headrests were used in ancient Egypt and to show that they must have been very personal objects.

Sleeping on a headrest.

The headrests were also the beginning of a new adventure in engaging with objects leading to new interpretations – the Museum of Lies. Inspired by the LÜSEUM: Wunderkammer Lügenmuseum Radebeul in Germany (formerly Lügenmuseum Gantikow, a development of the Kunsthaus Babe; https://www.luegenmuseum.de) as well as Orhan Pamuk’s Museum of Innocence – both as a novel (Pamuk, 2010) and museum (https://www.masumiyetmuzesi.org) – I decided to deliberately misplace our objects again. This time they were moved from their Egyptological setting into a fictional or unusual situation by using creative and artistic methods with the help of creative non-Egyptologists. This again was inspired especially by Orhan Pamuk, in this instance by his Modest Manifesto for Museums laid out in the catalogue of his physical museum (Pamuk, 2012). Here he states that we had “epics, representation, monuments, histories, nations, groups and team[s], large and expensive” and need now “novels, expression, homes, stories, persons, individuals, small and cheap” (Pamuk, 2012, p. [57]). In my mind, from this follows that objects require: stories, attention, awareness for materiality, identity (receiving and giving) and that at any scale (Zinn, 2019a, p. 185).

This coincided with the fact that in 2016, the idea of CURIOSITY in museums was making a come-back in museum and heritage studies (Chorell, 2021; Thomas, 2016). Curiosity is here understood as an eagerness to experience new things and to re-experience already known ideas from a new angle. By realising that it is often the unexpected we are curious about, we can accept that material culture is forcing us – in a good way – to tell stories. Being curious enables the narrative to be formed, which in return can re-contextualise things.

Even naming can function as storytelling. While working with school classes as part of their year 9 English curriculum, headrest CCM 189.996 became a boomerang, saucer lamp CCM 305.004 was called the magic hollow mushroom and CCM 276.004 – upper part of a statue from black stone – was named Darth Vader (Figure 12). Even these names seem to be lightyears away from the Egyptological identifications, the discussions following the naming exercise lead back to the original “Sitz im Leben” (setting in life). We took the exercise further and let the pupils write short stories. During the writing process, we discussed the objects, which function as inspiration for their stories from different angles. Headrest CCM 189.996 led to the following short story, co-authored by Chloe George and Nia Evans:

How much longer do we have to use these for? I think I’ve made it really clear that I don’t like them, especially since my brother and I broke off the stem and used it as a Boomerang. I don’t think anyone likes them, Cindy broke the stem of hers and used it as a headband to hold her hair back! Sleeping on concrete is bad enough without these stiff headrests. My back is so, so sore. At least the aliens are coming tomorrow to help build the pyramids. Even Tupac is coming to help! I wonder if he’ll bring Biggie?

Naming as storytelling.

It is striking how such new positions often reaffirm the original idea, meaning, or identity the objects (might have) had. Exhibiting the creative outputs together with the academic ideas really gave the visitors different pathways for understanding the objects (Figure 13; CCM 189.996 with different types of explanation in the exhibition). Intuitive explanations emerging from the artistic and creative involvement with the objects have led to a new set of academic enquiries. These “part-truths” work towards a more comprehensive object biography and better understanding. This encouraged me to take engagement further and include these first attempts of creatively playing around with interpretations into an academically underpinned (sub-)project called Museum of Lies, exploring creative additions to object biographies (Zinn, 2019a). This line of enquiry for unprovenanced objects can be one strategy, applicable to different museum settings and pop-up exhibitions, for how to deal with unprovenanced objects.

CCM 189.996 in exhibition situation.

In addition to the above-mentioned short stories written by pupils, I started to work with artists during the 2017/18 project season. Julie Davis – a painter living in Wales (https://www.juliedavisartuk.com/about.html) – was inspired by two wooden Sokar birds and chose one of them as the starting point of her creative exploration (CCM 1694.004; Figure 14). Being robbed of their original setting, both Sokar birds appeared to be simple little bird figurines. Explanation could be provided via comparative Egyptological object biographies, though however satisfying that was for a specialist, it did not enthuse the wider public. Julie’s triptych Into the Light (oil and acrylic on reclaimed wooden panels; Figure 15) – inspired by the artist’s thoughts about losing a close family member during this time – reconnected these objects with their original ancient Egyptian context of flying and overcoming space, time, and death. Throughout her creation process, we talked about the different academic, artistic, and personal perceptions of this artefact. In her artist statement (Interview with J. Davis), Julie mentioned that

“[a]s an artist, I found working in this way has been something of an exciting challenge: to respond to an object that had so much in terms of its own meaning and yet so little in terms of visual clues still remaining. Semiotically, birds have always been imbued with connotations across so many cultures, so the task was to respect this object culturally whilst responding personally. […] Looking back, I realised two things: firstly, that as a member of a medieval choir and having often been surrounded by British/European iconography I found that this influenced what I wanted to create – an object that could be felt or understood as ‘religious’ (i.e. a triptych) and yet was not necessarily confined to a particular time, place, or belief system. Secondly (and more personally), my father had passed away a couple of years ago, and he had always been very interested in birds and collected many pictures and objects. I have therefore found that in the last couple of years my own artwork has been ‘collecting’ birds as well – they have started to fly out of many of my paintings and have begun nesting in my head (and also in my house, in my own burgeoning collection). […] I was drawn to this object in particular: it further reinforced the idea that objects can speak to us in many different voices.”

Sokar Bird CCM 1694.004.

Julie Davis: “Into the Light.”

The triptych was exhibited together with the object, a short story written by one pupil, the scrapbook assembled by one of my students as well as the catalogue entry. This drawing together of different aspects and viewpoints could be seen as a summary of “part-truths” which – as part of the concept of the Museum of Lies – together create the understanding of the object. As mentioned in the quote, the positive reactions by exhibition visitors to this compilation in general as well as the triptych in particular stimulated Julie to continue to paint Welsh birds, which were since then widely displayed in art galleries.

This first successful attempt was then incorporated, expanded, and reflected upon in the following years, deliberately using different art forms to continue with the idea of playing around. In 2018/19, award winning Welsh poet Samantha Wynn-Rhydderch hand-wrote and performed at the exhibition vernissage the poem “Souvenir” inspired by the inscribed wall relief CCM186.996. The relief was very well researched and academically described by BA student Georgie Whittock who then also presented this object at the International Congress for Young Egyptologists in Leiden in August 2019 (title: The hare above the waterline – researching an unprovenanced raised relief from Cyfarthfa Castle Museum, Merthyr Tydfil, Wales, UK) and offered a talk and an object tour during the exhibition in Lampeter. This object, showing the hieroglyphs wnn (to be, to exist), was likely taken from a temple or a tomb wall due to the visual character of the hieroglyphs. This fact inspired Samantha to think about the circumstance that this piece was misplaced and ripped out of its original context. She reflected on the question of what is happening with artefacts (and people) being misplaced. This reflection is structured as a direct dialogue with the object.

Souvenir – Samantha Wynne Rhydderch

Dear hieroglyph hare, did he mention you in his letters home, the man who chipped out this picture, not thinking that you are in fact a word? Without your presence at whichever tomb or temple he nicked you from, the sentence no longer makes sense, and hasn’t done for a hundred years.

You float on a row of ‘w’s and ‘n’s: when when when. So many questions unanswered: when did he take you away? When did you arrive in Merthyr to grace a mantelshelf, you who had observed the world from the top of a temple or the gloom of a tomb, guarding your conversations with the dead?

When you look back at us from a glass case in this place of learning, we will stop and listen to what you have to teach us about unexpected journeys, about context, about stillness and change, what it is like to live in the boundary between the desert and the fertile land, to speak through time.

The reading performance at the vernissage brought this message even closer to home and had an increased emotional effect on the audience.

In the same year, I set out a photography workshop with A-level and vocational art students (Madeleine Smith, Gethin Bevan, and Friederike Zinn) with the aim to provide further opportunities for creative engagement leading to a multifaceted and diverse portfolio for their application to university-based art courses at BA level. They gained experiences in photographing archaeological objects both for academic and creative outputs and then took these photos as the starting point for artistic collages or computer designs. The outputs were again exhibited next to the object and together with the scrapbooks and catalogue entries created by my students to give very different yet complementing descriptions. All three were present at the vernissage and received many questions by the audience.

For 2019/20, I planned a performance interpretation via a short neoclassical ballet piece called Death?!, choreographed by Friederike Zinn, then classical ballet student of Ballet West, Scottland and to be danced by Isobel Fisher, Ingrid Nokkleberg, Ashton Parker, and Friederike Zinn. The project started in January 2020 was interrupted by the COVID pandemic and could not be brought to an end.

Having time during the COVID lockdowns to rethink creative narratives and being forced to question common ways of working due to the unexpected and disruptive event, which shook up and changed the world as we knew it, I was inspired to start to conceptualise the interaction with ancient material culture, going away from one particular object and its interpretation to addressing wider questions. In this sense, I was following the idea instilled by Samantha Wynn-Rhydderch, being encouraged by the response of the audience to this approach shown in 2019. This resulted in two conceptual art projects, which are finished but have not yet been shown together with the objects in an exhibition due to the delay because of the pandemic. Therefore, the engagement character beyond the immediate engagement with the artists and their response to the Egyptological and heritage side could not yet been tested.

The first of these initiatives was Ancient Egypt reborn? Unprovenanced objects, art and emotions III together with Professor Catrin Webster (artist, academic Aberystwyth University) resulting in a series of painted canvases functioning as paintings each in their own right as well as being able to be used together responding to the invert character of moulds used in ancient Egypt (2020–2022).

A second project aimed to continue ideas from the interrupted dance project. Friederike Zinn had moved on to study contemporary dance at Trinity Laban Conservatoire of Dance and Music, London. In the project Moving Objects, she used conceptual dance in collaboration with myself to explore the agency of objects, the interrelationship of objects and the human as well as notions of misplacement/absence. The outcome of three workshops with further dancers and myself was filmed and transformed into a 3 min long artistic dance video which will be shown at the next exhibition.

The experiences with the pop-up exhibitions and audience engagement also changed the presentations of the Egyptian objects within the home museum, both as temporary exhibitions as well as re-designing the cases in the permanent exhibition and accompanying them with new labels, panels, and explanatory content. This not only raised the profile of this collection so that more visitors popped down to the museum in South Wales in addition to visiting the pop-up exhibitions in Mid-Wales but has also drawn up strategies for working with lost, forgotten, misplaced, and unloved objects elsewhere.

7 Instead of a Summary: Engaging as a Method

To come back to Stevenson’s (2019, p. 1) remark given at the beginning of this article that these objects are both scattered between different places and cultures as well are unassuming, I would like to state that the practices of engagement re-awakened these artefacts, embedded them with meaning in different layers and developed them into emotionally fascinating objects on par with monumental works of art and beyond, both in value and appreciation. These ordinary, mostly damaged and broken objects not only revealed their potential to be remarkable, they became EXTRAordinary (Zinn, 2019b).

All these above-described methods centre on the materiality of the objects from which different meanings are drawn. This approach connects these previously dormant objects, with several identities in which they are placed: locally at Merthyr Tydfil in rural Wales, students of UWTSD in Lampeter who are becoming involved in primary research, local school children using the exhibited objects as case studies in their Religious Education and English curriculum, the community around Lampeter, the research community (Egyptologists, anthropologists, heritage professionals), artists, and more. The inclusion of and engagement with all these audiences and stakeholders proved crucial for the success of this project and leads to a sustainable interaction with neglected artefacts and therefore to heritage resilience.

The setup of this successful cooperation helps to overcome the barrier of dormant Egyptian collections tucked away in Museums conceived differently by helping to break down the museum’s barrier to research, influencing decision makers, opening up new networks and above all developing audiences in many ways. It is often said that visitors go to museums to see what they expect, yet I argue that we do not do enough to break down these pre-conceived barriers. One way to do that is to make the potential audience curious. Interestingly enough, it seems that it is the unexpected that we are curious about. The perfect side effect of this lies in the fact that curiosity therefore re-contextualises things. This Freude am Neuen (delight in the new) – albeit ambiguous – can break down the often-harboured idea of the museum as a dusty institution sheltering – some might say hiding – things, which are real but dead.

As such, these engagement initiatives can be seen as part of the discussion around “museums are not neutral” as the Museum of Lies raises the questions of what could or should be exhibited and where and how it is shown (refer also Zinn, 2019a). Furthermore, it problematizes who should or could make this decision. This also leads to a discussion about engagement practices and the impact forms of connecting audiences and objects might have via alternative methods as part of this process. The above-described examples show that museums as institutions or indeed the academic discipline museum studies are not outlived. This is valid as long as museums- or archaeological objects – as part of the wider heritage sector and cultural media production – are future-orientated and audience focused (including new potential audiences), seen under many perspectives inter-, multi- and intradisciplinary and are understood to be relevant (socially, culturally, politically, identity focused). Above all engaging with material culture needs to be FUN.

Acknowledgments

Foremost, I would like to thank all the creative people involved, especially the following (in sequence of participation): Artists: Julie Davis, Samantha Wynne-Rhydderch, Madeleine Smith, Friederike Zinn, Gethin Bevan, Catrin Webster. Choreographer: Friederike Zinn. Dancers: Friederike Zinn, Ashton Parker, Isobel Fisher, Ingrid Nokkleberg, Tessa Nicholls. I also would like to express my deepest thanks to my exhibition students and the pupils of Ysgol Bro Pedr who have been taking part in this project since 2011. Furthermore, I would like to point out that such a complex and long-ongoing project is not happening in isolation and only possible with the help of many people starting from the highly collaborative museum staff of Cyfarthfa Castle Museum over colleagues at UWTSD, the staff of the Roderic Bowen Library and Archives where the pop-up exhibitions happen, staff at the participating schools and the organisers of the contributing home-education networks. I also would like to thank the organisers of the European Association of Archaeologists (EAA) panel and editors of this special issue – Katherine Wilson, Christina Antenhofer, and Thomas Pickles – for the interesting topic and inspiring discussions. Last but not least, I would like to thank Thomas Jansen for patiently discussing and then proof-reading the draft. I, however, take full responsibility for all potential errors in the article.

-

Funding information: This work is based on the research entitled The public and the extraordinary – material culture as tool to fascinate, presented at the EAA annual conference 2022: Networking in session 27: Engaging the Public, Heritage, and Educators through Material Culture Research (02/09/2022). The participation in the conference was part-funded by a conference grant as part of a RIAP (Research and Impact Accelerator Programme) Research Innovation Award awarded by the University of Wales Trinity Saint David, UK in 2022. The article was written during a Visiting Professorship in Egyptology (academic year 2023/24) at the Institute for the History of the Ancient World (IHAC), Northeast Normal University, Changchun, China.

-

Author contributions: The author confirms the sole responsibility for the conception of the study, presented results, and manuscript preparation.

-

Conflict of interest: The author states no conflict of interest.

-

Informed consent: Informed consent has been obtained from all individuals included in this study.

-

Data availability statement: Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Al Saad, Z., & Azaizeh, S. (2023). Re-establishing context of “orphaned” museum objects through scientific investigation: A case study from the Museum of Jordanian Heritage. International Journal of Conservation Science, 14(1), 75–82. doi: 10.36868/IJCS.2023.01.06.Search in Google Scholar

Anderson, A., de Cosson, A., & McIntosh, L. (Eds). (2015). Research informing the practice of museum educators diverse audiences, challenging topics, and reflective praxis. Sense Publishers.10.1007/978-94-6300-238-7Search in Google Scholar

Attfield, J. (2000). Wild things: The material culture of everyday life. Berg.10.5040/9781350036048Search in Google Scholar

Bradbury, P., & McVicker, J. N. (n.d.). BradburyMcVicker. Retrieved from https://www.bradburymcvicker.com/.Search in Google Scholar

Brodie, N., Doole, J., & Renfrew, C. (2001). Trade in illicit antiquities: The destruction of the world’s cultural heritage. Oxbow Books.Search in Google Scholar

Byrne, S., Clarke, A., Harrison, R., & Torrence, R. (2011). Unpacking the collection: Networks of material and social agency in the museum. Springer.10.1007/978-1-4419-8222-3Search in Google Scholar

Campbell, P. (2013). The illicit antiquities trade as a transnational criminal network: Characterizing and anticipating trafficking of cultural heritage. International Journal of Cultural Property, 20(2), 113–153.10.1017/S0940739113000015Search in Google Scholar

Chollier, V. (2019). Social network analysis in egyptology: Benefits, methods and limits. The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, 105(1), 83–96.10.1177/0307513319889329Search in Google Scholar

Chorell, T. G. (2021). Modes of historical attention: Wonder, curiosity, fascination. Rethinking History: The Journal of Theory and Practice, 25(2), 242–257. doi: 10.1080/13642529.2020.1847896.Search in Google Scholar

Davies, R. (2001). Overcoming barriers to visiting: Raising awareness of, and providing orientation and navigation to, a museum and its collections through new technologies. Museum Management and Curatorship, 19(3), 283–295. doi: 10.1080/09647770100501903.Search in Google Scholar

Department for Culture, Media and Sport. (2023). Monthly and Quarterly Visits to DCMS-Sponsored Museums and Galleries- April 2023 to June 2023 data tables. Retrieved from https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1187118/Monthly_and_quarterly_visits_to_DCMS_sponsored_museums_and_galleries_April_2023_to_June_2023_data_tables.ods.Search in Google Scholar

Desai, P., & Thomas, A. (1998). Cultural diversity: Attitudes of ethnic minority populations towards museums and galleries. Museums and Galleries Commission.Search in Google Scholar

Driver, F., Nesbitt, M., & Cornish, C. (Eds.). (2021). Mobile museums: Collections in circulation. UCL Press. doi: 10.14324/111.9781787355088.Search in Google Scholar

Eckersley, S. (2022). Museums as a public space of belonging? Negotiating dialectics of purpose, presentation, and participation. In S. Eckersley & C. Vos (Eds.), Diversity of belonging in Europe: Public spaces, contested places, cultural encounters (pp. 17–40). Routledge.10.4324/9781003191698-4Search in Google Scholar

Elliott, K. (2014). A happy ancient Egyptian family? The bronze statuettes of Osiris, Horus, and Isis (Cyfarthfa Castle, Merthyr Tydfil 1697.004, 1699.004, 1705.004). The Student Researcher, Journal of Undergraduate Research University of Wales Trinity Saint David, 3(1), 7–18.Search in Google Scholar

Fahlander, F., & Oestigaard, T. (2004). Introduction: Material culture and post-disciplinary sciences. In F. Fahlander & T. Oestigaard (Eds.), Material culture and other things - post-disciplinary studies in the 21st century (pp. 1–20). University of Gothenburg, Department of Archaeology.Search in Google Scholar

Fisher, L. J. (2009). Photography for Archaeologists, Part II: Artefact recording. (BAJR Practical Guide Series: 26). Retrieved from http://www.bajr.org/BAJRGuides/26.%20Artefact%20Photography%20in%20Archaeology/26ArtefactPhotographyforArchaeologists.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

Fitzenreiter, M. (2023). Technology and culture in Pharaonic Egypt: Actor network theory and the archaeology of things and people. Cambridge University Press.10.1017/9781009070300Search in Google Scholar

Geoghegan, H., & Hess, A. (2015). Object-love at the science museum: Cultural geographies of museum storerooms. Cultural Geographies, 22(3), 445–465.10.1177/1474474014539247Search in Google Scholar

Gerstenblith, P. (2019). Provenances: Real, fake, and questionable. International Journal of Cultural Property, 26(3), 285–304. doi: 10.1017/S0940739119000171.Search in Google Scholar

Griffith Institute. (2018). Artefacts of Excavation: British Excavations in Egypt 1880-1980 – Gurob. Retrieved from https://egyptartefacts.griffith.ox.ac.uk/excavations/1920-21-gurob.Search in Google Scholar

Herle, A. (2012). Objects, agency and museums: Continuing dialogues between the Torres Strait and Cambridge. In S. H. Dudley (Ed.), Museum objects: Experiencing the properties of things (pp. 295–310). Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Hicks, D. (2010). The material‐cultural turn: Event and effect. In D. Hicks & M. C. Beaudry (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of material culture studies (pp. 25–98). Oxford University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Hodder, I. (2011). Human-thing entanglement: Towards an integrated archaeological perspective. The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 17(1), 154–177. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23011576.10.1111/j.1467-9655.2010.01674.xSearch in Google Scholar

Hodder, I. (2012). Entangled: An Archaeology of the Relationships between Humans and Things. Wiley-Blackwell.10.1002/9781118241912Search in Google Scholar

Hodder, I. (2016). Studies in human-thing entanglement. Author’s edit. http://www.ian-hodder.com/books/studies-human-thing-entanglement.Search in Google Scholar

Ingold, T. (2011). Being alive: Essays on movement, knowledge and description. Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Insoll, T. (Ed.). (2007). The archaeology of identities: A reader. Routledge.10.4324/9780203965986Search in Google Scholar

Johannesen, J. M. (2004). Operational ethnicity. Serial practice and materiality. In F. Fahlander & T. Oestigaard (Eds.), Material culture and other things - Post-disciplinary studies in the 21st century (pp. 161–184). University of Gothenburg, Department of Archaeology.Search in Google Scholar

Joyce, R. A. (2012). From place to place: Provenience, provenance, and archaeology. In G. Feigenbaum & I. Reist (Eds.), Provenance: An alternate history of art (pp. 48–60). Getty Publications.Search in Google Scholar

Kennelly, S. (2023, December). Upward trend in museum visitor figures across UK: Latest data suggests museums are gradually regaining pre-pandemic levels of footfall. Retrieved from https://www.museumsassociation.org/museums-journal/news/2023/12/upward-trend-in-museum-visitor-figures-across-uk/#.Search in Google Scholar

Kilian, A., & Zöller-Engelhardt, M. (Eds.). (2021). Excavating the extra-ordinary: Challenges & merits of working with small finds. Proceedings of the International Egyptological Workshop at Johannes Gutenberg-University Mainz, 8–9 April 2019. Propylaeum. doi: 10.11588/propylaeum.676.Search in Google Scholar

Knappett, C. (2005). Animacy, agency, and personhood. In C. Knappett (Ed.), Thinking through material culture: An interdisciplinary perspective (pp. 11–34). University of Pennsylvania Press. doi: 10.9783/9780812202496.11.Search in Google Scholar

Knappett, C. (2008). The neglected networks of material agency: Artefacts, pictures and texts. In C. Knappett & L. Malafouris (Eds.), Material agency: Towards a non-anthropocentric approach (pp. 139–156). Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-74711-8_8.Search in Google Scholar

Kolb, C. C. (2020). Provenance studies in archaeology. In C. Smith (Ed.), Encyclopedia of global archaeology (pp. 8962–8972). Springer.10.1007/978-3-030-30018-0_327Search in Google Scholar

Kopytoff, I. (1986). The cultural biography of things: Commoditization as process. In A. Appadurai (Ed.), The social life of things (pp. 64–91). Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511819582.004Search in Google Scholar

Langer, C. (Ed.). (2017). Global Egyptology: Negotiations in the production of knowledges on ancient Egypt in global contexts. Golden House Publications.Search in Google Scholar

Langer, C., & Matić, U. (2023). Postcolonial theory in Egyptology: Key concepts and agendas. Archaeologies 19, 1–27. doi: 10.1007/s11759-023-09470-9.Search in Google Scholar

Latour, B. (2005). Reassembling the social: An introduction to actor-network-theory. Oxford University Press.10.1093/oso/9780199256044.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Luke, J., & McCreedy, D. (2012). Breaking down barriers: Museum as broker of home/school collaboration. Visitor Studies, 15(1), 98–113.10.1080/10645578.2012.660847Search in Google Scholar

Matić, U. (2018). De-colonizing the historiography and archaeology of ancient Egypt and Nubia. Part 1. Scientific racism. Journal of Egyptian History, 11(1–2), 19–44. doi: 10.1163/18741665-12340041.Search in Google Scholar

Matić, U. (2023). Postcolonialism as a reverse discourse in Egyptology: De-colonizing historiography and archaeology of ancient Egypt and Nubia Part 2. Archaeologies, 19, 60–82. doi: 10.1007/s11759-023-09473-6.Search in Google Scholar

Ministerio della Cultura. (2019). Musei, top 30: Colosseo, Uffizi e POMPEI superstar nel 2019. Retrieved from https://cultura.gov.it/comunicato/musei-top-30-colosseo-uffizi-e-pompei-superstar-nel-2019-franceschini-autonomia-funziona-andiamo-avanti-su-percorso-innovazione-1#:∼:text=La%20Top%2030%20dei%20musei,circa%204%20milioni%20di%20presenze.Search in Google Scholar

Modest, W. (2019). Introduction: Ethnographic museums and the double bind. In W. Modest, N. Thomas, D. Prlić, & C. Augustat (Eds.), Matters of belonging: Ethnographic museums in a changing Europe (pp. 9–21). Sidestone Press.Search in Google Scholar

Murphy, A. (2015). Accessibility in museums: Creating a barrier-free cultural landscape. Retrieved from https://advisor.museumsandheritage.com/features/accessibility-in-museums-creating-a-barrier-free-cultural-landscape/.Search in Google Scholar

Museo Egizio. (2023). Integrated report 2023. Retrieved from https://museoegizio.it/en/explore/news/integrated-report-2023/.Search in Google Scholar

Pamuk, O. (2010). The museum of innocence. Faber and Faber.Search in Google Scholar

Pamuk, O. (2012). The innocence of objects. Abrams.Search in Google Scholar

Pickering, A. (2010). Material culture and the dance of agency. In D. Hicks & M. C. Beaudry (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of material culture studies (pp. 191–207). Oxford University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Plotz, J. (2008). Portable property: Victorian culture on the move. Princeton University Press.10.1515/9781400828937Search in Google Scholar

Pocius, G. (2004). Objects and identity/objets et identitéʼ. Material Culture Review, 60(1), 1–3.Search in Google Scholar

Research Centre for Museums and Galleries (RCMG). (2020). Museums and social inclusion: The GLLAM Report. University of Leicester.Search in Google Scholar

Research Centre for Museums and Galleries (RCMG). (2024). Trans-inclusive culture: Guidance on advancing trans inclusion for museums, galleries, archives and heritage organisations. University of Leicester.Search in Google Scholar