Abstract

This paper constructs networks, using social network analysis, of Delian maritime trade and the diffusion of art and architectural styles from Mediterranean locations to Delos in the Archaic, Classical and Hellenistic periods. The dataset used is based on a selection of published archaeological finds and other primary sources supported by modern scholarship. Primary sources include art and architecture, evidence of commercial exchange from the archaeological record and ancient textual sources. Also considered is the large corpus of honorary and dedicatory inscriptions at Delos, mainly from the early Hellenistic period, and whether ethnicity also relates to trade or locations influential in Delian art and architecture. Art influences include the representation and practice of cults manifested in both direct copying of styles, hybrid productions and syncretism. Subject to the limitations discussed, this approach illustrates the extent to which trade and the influences of art and architecture originate from the same source and less so in relation to the ethnicity of inscriptions. The maps for each period demonstrate how trade, art and architectural influences changed diachronically and in sync with changing political powers. This demonstrates the tolerance of the island to outside influences, a cosmopolitan, tolerant melting pot of peoples, cultures and cults.

1 Introduction

The abundance and variety of architecture and art styles at Delos demonstrate how external political and economic events dictated the island and the sanctuary’s history. The hypothesis is that trade and the influences of art and architecture originate from the same source, which can be illustrated by constructing and comparing networks for each. The data used herein for Delos’s trade connections and the diffusion of art styles are contained in Appendix 1 for the Archaic period, Appendix 2 for the Classical period and Appendix 3 for the Hellenistic period. Inscriptions from Delos (Figure 9) are based on lists indicating ethnicity in the appendices of Constantakopoulou (2017). Social network analysis is an efficient methodology to illustrate these dynamics, which analyses patterns of networks and the relationship between “actors” like people or sites, which are referred to as nodes and the connections between them as links or edges. The networks below use trading sites as nodes and links consisting of evidence of commercial exchange and the diffusion of art and architecture styles and syncretism. Trade links in the maps are colour-coded to identify different commercial exchange categories and art and architecture mediums used in the networks. The measurements illustrated by node size include outdegree, which ranks nodes by the number of their outgoing links (Exports or Diffusion) with Delos (Figures 1 and 3 and and 4) and degree, which ranks nodes illustrated by node size, by the number of connections they have in the Aegean and Eastern Mediterranean with respect to the overall Hellenistic trade network (Figure 5).

2 Dataset and Network Definitions

Circulating artefacts, art styles, and syncretism contribute to forming social ties across regions (Leidwanger & Knappet, 2018, p. 2) and, as described in Malkin’s (2011) seminal work creates a “Small Greek World.” Inscriptions are evidence of the mobility of people of different ethnicities. Trade exchange can be determined by evidence of the movement of amphorae for olive oil, wine and other foodstuffs with the source and destination of grain, enslaved persons and financial contracts relying on ancient textual sources. Metal hoards can be subjected to isotope analysis to identify ore provenance. Other useful scientific analyses include the evidence of cultivation strategy, land suitability for grapes and olives, and chromatography–mass spectrometry on amphorae to determine contents.

There are specific considerations and limitations to the selection of data samples. Having statistical significance with small samples can be difficult, and a sufficient representative sample is preferable. The sample of Delos trade connections in the appendices is from a trawl of Mediterranean-wide primary sources and modern scholarship, so a significant sample of connections is included. Statistically, using available artefacts rather than a random selection might not be stochastic (representative of the total population). However, targeting sites and choosing a significant and broad sample of exchange categories is a purposive approach and an acceptable methodology ( Richardson & Gajewski, 2002). These artefacts only act as proxies for trade connections and not necessarily the sailing route to reach their destination. Outcomes can also be biased towards sites with a higher number of finds. However, qualitative tests on the networks can be applied by comparing historical and network scholarship to network outcomes. Also, quantitative tests can be carried out to check network robustness by adding and removing nodes and links (Borgatti et al., 2006), to see if overall results remain consistent. The two networks of trade connections and the diffusion of art and architecture relating to Delos alone are “ego” networks as they relate to only part of a more extensive network in each instance. The network results of each do appear to corroborate each other (Borgatti & Li, 2009). As Greene describes, focusing on artefacts from part of a network offers artefacts as clear identifiers of the ego’s origins, relationships, and connections to its sociocultural and technological environment (Greene, 2018, p. 144). Also included is a map to illustrate Delos’s centrality at its economic peak in the Aegean and Eastern Mediterranean during the Hellenistic period (Figure 5).

3 Delos – Brief History of a Network Node

Delos was an important religious sanctuary, the birthplace of Apollo and a trading port in the Cycladic Island group in the Aegean Sea. Its geographical location made it an ideal stopping-off point and crossroads for trading, political and military movements. Cabotage and longer-distance journeys would have promoted the diffusion of cultic practices, which were reinterpreted locally (Mills, 2018). This enabled new ideas, art, culture, and technology to spread to Delos, even from nodes with whom it had a weaker connection. The new artistic innovations at Delos arose because of these weak ties as they were new styles and syncretism from outside that were unavailable within its own microregion (Granovetter, 1983). This phenomenon is particularly evident at Delos in the Hellenistic period. Also, innovative designs in living spaces and commercial premises were initiated by locals and resident traders who settled at Delos, influenced by the architecture and functionality applied at their place of origin. A combination of strong and weak ties most effectively spreads or diffuses religious innovation and participation (Kowalzig, 2018; see also Collar, 2022; Malkin, 2011).

The island was inhabited since the second-half of the third millennium B.C.E. Recognising limitations in dating, monumental buildings at Delos predated the erection of monumental buildings at Olympia, where no cult buildings or monuments were erected earlier than c. 600 B.C.E (Gruben, 2000, pp. 61–88). The Temple of Apollo at Delphi, other than of laurel, beeswax and bronze described by Pausanias (Description of Greece, 10.5.9-13), is attested to the early sixth-century B.C.E (Scott, 2014, pp. 36–39). Delos had monumental buildings probably a 100 years earlier. The earliest buildings associated with the cult were built in the late eighth- or early seventh-century B.C.E., including Temple G, a narrow construction of rough granite blocks (Bruneau & Ducat, 1983, p. 123). Building Ac/Artemision was built c.700 B.C.E. on top of Mycenean ruins and artefacts, and the Heraion, a small square building on the path up Mount Cynthus. It is considered unlikely that these were completed with local resources only and probably required the help of other island states (Constantakopoulou, 2007, pp. 41–42). The island was closely connected to an island network in the Archaic period, dominated by Athens in the Classical period and under the influence of Ptolemies, Antigonids, Athenians and Romans in the Hellenistic period. While in Rome’s orbit, it was sacked by Mithridates VI of Pontus, an enemy of Rome, in 88 B.C.E and again in 69 B.C.E by pirates of Athenodoros who were allies of Mithridates. While settlement continued up to the eighth-century C.E., it never recovered its centrality, evident during the Hellenistic period (Figure 5).

4 Archaic Period

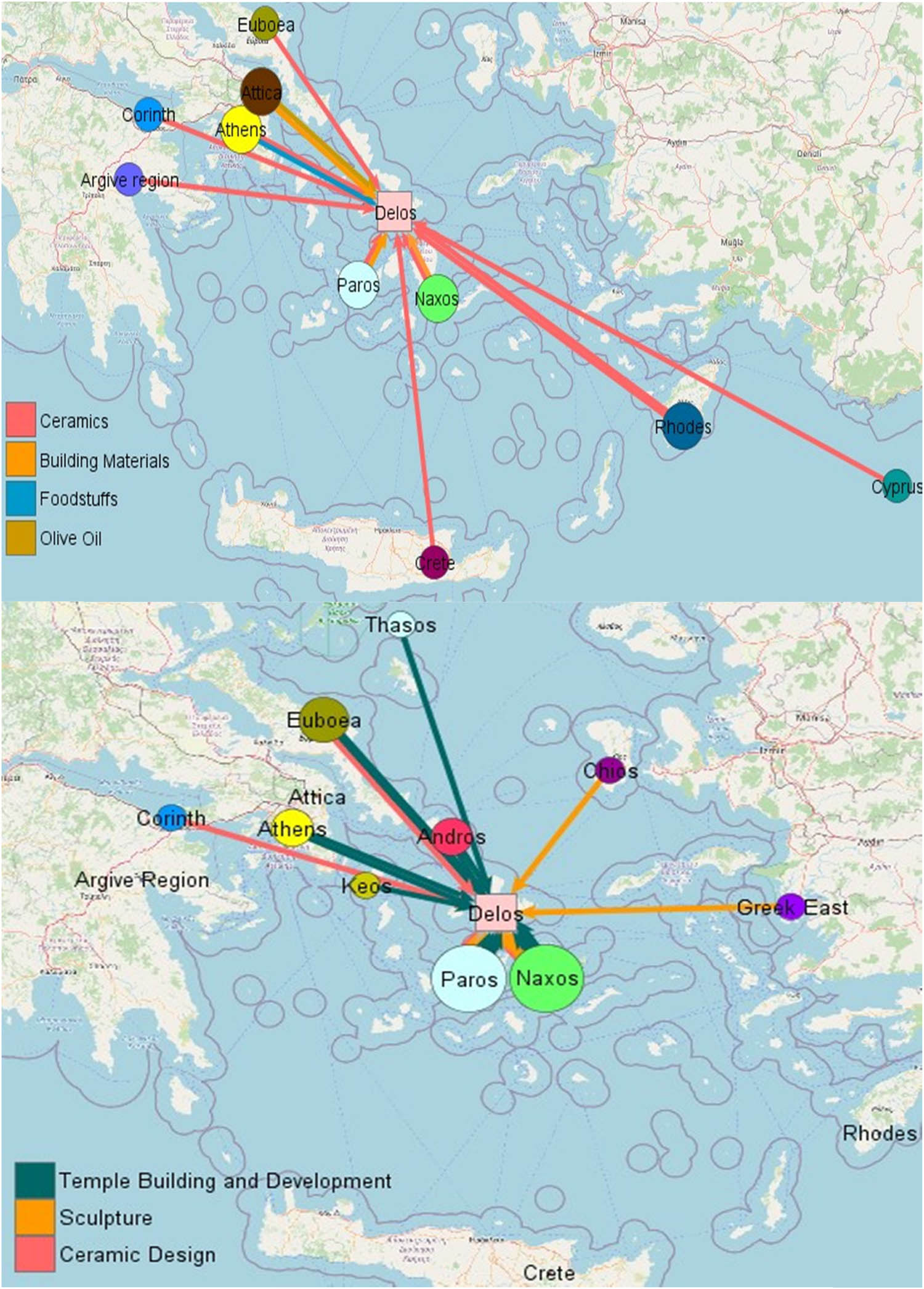

Delos had natural resources to serve the basic needs of travellers, like food and water (Angliker, 2017). The agrarian landscape was actively exploited from the late Archaic period with a subsistence polyculture closely linked to livestock farming (Brunet, 2016). However, imports were required to meet the island’s subsistence needs demonstrated by import links of foodstuffs and olive oil in the network analysis (Figure 1). The island had no exports other than the invisible export revenue from visitors to the sanctuary, which was the seat of the pan-Ionian festival (Davis, 1982). Delos’ primary contacts were with the Cycladic islands, and even though they could be considered culturally homogeneous, they still brought distinct ideas and styles often reflected in the art and architecture. Their investment in monumental buildings aimed to advertise their piety, power and wealth to the Delian gods and local and visiting communities (Constantakopoulou, 2015, p. 27). During this period, Athens/Attica supplied foodstuffs, limestone, and olive oil from Attica, and marble was provided by Paros and Naxos for the burgeoning development of the sanctuary. Other trade connections evident in ceramics include Euboea, Rhodes, Corinth and the Argive region, Crete, and Cyprus, as set out in Table A1, Appendix 1.

Archaic period. Top: Trading Links (Appendix 1, Table A1). Below: Art and Architecture influence and development (Appendix 1, Table A2). Node size indicates the strength and ranking by Outdegree for trade exports and artistic influence. Some nodes may not be in their correct geographic position placed on the edge of the map for visibility.

Naxos constructed their oikos on Delos in the late eighth-century B.C.E, adding a porch in 575 B.C.E roofed with Naxian tiles (Ohnesorg, 1991, pp. 53–59). Athens constructed the Porinos Naos, an Ionic Temple with a cella. It was probably initiated by Peisistratus following his purification of the sanctuary (Herodotus 1.64.1; Thucydides 3.104, 1-2). Based on the use of Attic limestone Boersma considers this to be the only Attic-style building outside of Attica in this period (IG XI.2 158a60–1; Boersma, 1970, p. 17; Bruneau & Ducat, 1983, p. 128; Constantakopoulou, 2007, 64; Gruben, 2000, p. 164; Parker, 1996, p. 87). Herodotus describes the Keians having a dining facility (hestiatorion) on Delos (Herodotus, The Histories, 4.35.4). Andros constructed their Hestiatorion, and Naxian marble was used in distinctive styles applied to the Naxian Lions (Figure 2). Parian marble was used on its iconic Sphinx and the marble blocks used in the Parian oikos and Letoon, with its Parian decorative pattern also seen in its colony of Thasos (Tréheux, 1987, p. 388).

The Lions of the Naxians. Archaic Period: Late-sixth-century B.C.E. Made of coarse-grained Naxian marble. Archaeological Museum of Delos (Photo: D Grant).

Naxian kouroi examples are the earliest on Delos. An early late seventh-century B.C.E. example with the subject’s hair thrown back behind his shoulders, unlike the treatment on korai, is comparable with the kouroi of Théra. Naxian models are made from the bluish Naxian marble with a distinct flat thin profile, narrow-waisted and not emphasising anatomical or muscular detail, and the surfaces are smooth with soft features with some examples according to Bruneau and Ducat (1983, pp. 56–64) evoking a Cyrene kouros or influenced by works from Athens and Rhodes. The Nikandre Statue from 640 B.C.E., found at the Sanctuary of Artemis, contains an inscription which speaks of an elite family, expressing grief for a lost daughter, sister and wife. Unlike male kouroi, korai are passive, mirroring their role in life, the importance of a marriage union with other elite families, and the continuation of the family line (Osborne, 1994, pp. 88–96). In considering the proposition that outsiders significantly influenced Delos, this early sculpture and inscription of a daughter with a Naxian father provides an early example of an external presence. The appearance of Parian kouroi begins around 580 B.C.E. and is of Parian marble, pure white, fine-grained, semi-translucent and flawless. Parian kouroi appear distinctly athletic with heavier torso, thicker waist and arms pressed back, which appear to push the chest out. All these works are characteristic of archaic island sculpture (Bruneau & Ducat, 1983, pp. 56–64).

Although there is very little evidence available to construct Archaic trade links compared to the tangible art and architecture record, there is a correlation in the source of temple development and styles (Figure 1 top) with the Delos imports of mainly building material and foodstuffs (Figure 1 below). The high-ranking nodes (larger nodes) are similar in each map measured by outdegree (Exporter and diffusion rank). Although eastern influences can be seen in the art record, any trade links are mainly from a north-easterly direction and the islands. Many of the links in this period are less associated with normalised trade and more a matter of supplying material for architectural and sculptural development at the sanctuary. Like monumental building construction, sculpture development styles and materials initially originate from local island networks, particularly Naxos and Paros.

5 Classical Period

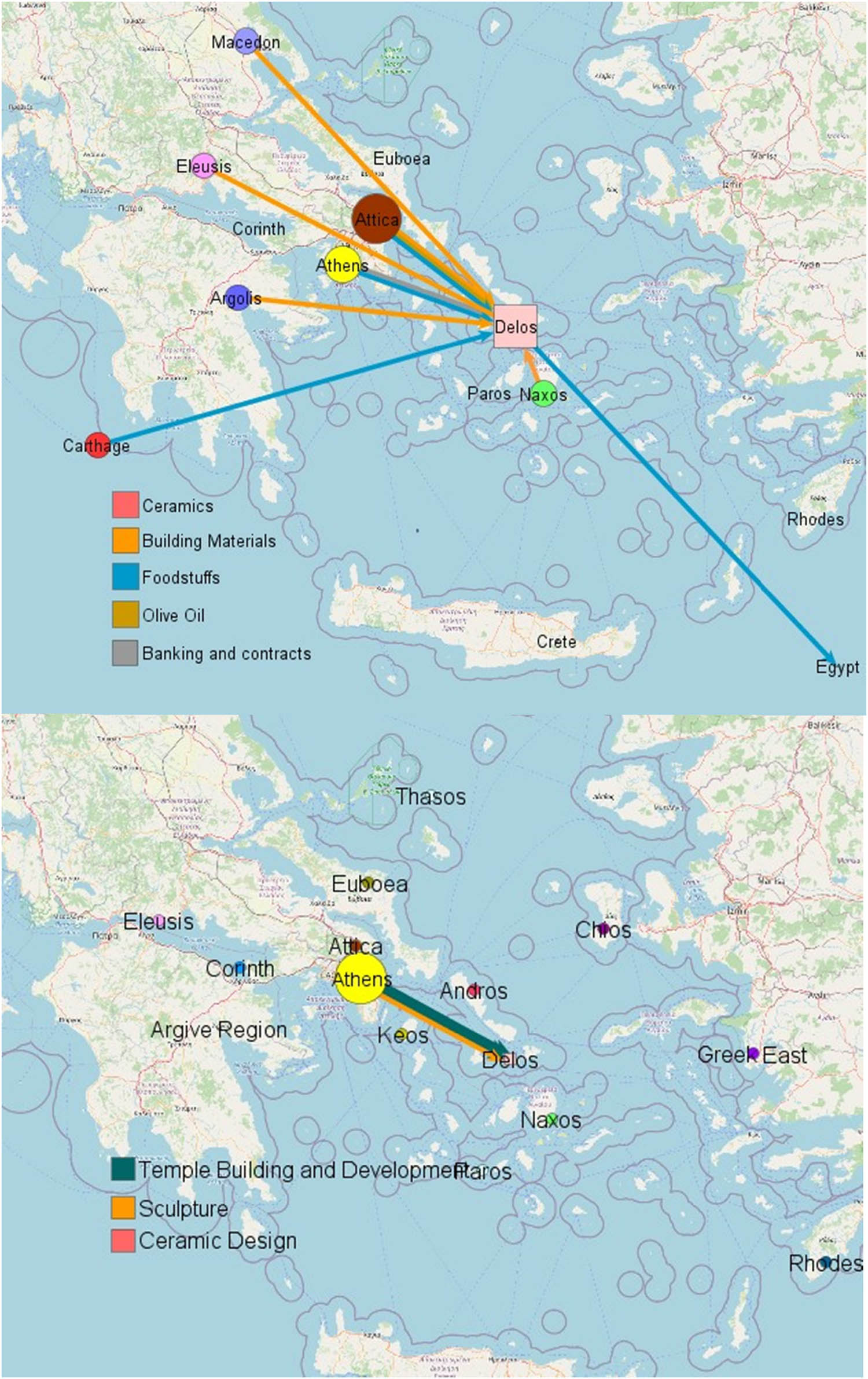

In this period, Athens exercised near-total control over maritime trade in the Aegean and over Delos, which, for a period, held the treasury of the Delian League (Carlson, 2013, p. 1; Malkin, 2011, p. 215; Pomeroy et al., 2015, pp. 161–67). This hegemony lasted until the island’s independence in 314 B.C.E. (Chankowski, 2008). This, too, is reflected with minimal evidence available of Delos’ trading relationships, which are mainly with Athens and Attica, and timber for the sanctuary coming from Macedon (Figure 3 top). This Athenian dominance is also reflected in architectural development (Figure 3 below), based on links in Table A4, Appendix 2.

Classical period. Top: Trading Links (Appendix 2, Table A3). Below: Art and Architecture influence and development (Appendix 2, Table A4). Node size indicates the strength and ranking by Outdegree for trade exports and artistic influence. Some nodes may not be in their correct geographic position placed on the edge of the map for visibility.

The Temple of the Delians is the largest of three dedicated to Apollo and was funded by the Delian League (Smarczyk, 1990, p. 465). Construction was interrupted after the removal of the Delian League treasury to Athens in 454 B.C.E. and was not recommenced until after Delian independence (Constantakopoulou, 2017, p. 70). It was the only peripteral temple on Delos, with single rows of thirteen Doric columns on the long side and six on the narrow side. Coincidentally, construction of the Temple of Hephaestus on the Agora of Athens, a similarly designed peripteral temple, commenced in 449 B.C.E., just after the league’s relocation. The Doric peripteral configuration has its original roots in the sixth-century B.C.E., like the Temple of Artemis at Corcyra from 580 B.C.E. The Temple of Athenians, beside the Temple of The Delians, is an amphiprostyle design with six Doric columns on the narrow side constructed c.425–420 B.C.E. The temple contained seven statues on a horseshoe-shaped base of grey-blue marble from Eleusis. Athens sent white Pentelic marble and experienced artisans, and according to P. J. Hadjidakis, probably under the supervision of Callicrates, the craftsman responsible for the Temple of Nike on the Athenian Acropolis. Interestingly, measurements of the temple’s lateral acroteria match that of the Temple of Athena Nike and the Athenian treasury at Delphi (Schultz, 2001, p. 17). From the available evidence, the Athenians appear not to have left a large corpus of sculptures on the island in this period. The acrotere of the Temple of the Athenians narrated mythological scenes depicting Athenian heroes, including the abduction of Oreithyia by Boreas, who personified the northern wind (Boersma, 1970, p. 171).

6 Hellenistic Period

The changing political and military fortunes are clearly evident, and the same sources (indicated by node size measured by outdegree = export/diffusion rank) of export trade goods to Delos (Figure 4 top) as the origin of diffusing styles of art and architecture (Figure 4 below) found at the sanctuary. In particular, Egypt, Macedon, Phoenicia, Asia Minor, and Italy feature with high outdegree centrality in both maps. The Black Sea was a meaningful trading connection, yet it was not reflected in the art and architecture records. This is not that surprising in that culture and religious influence went from the Greek world in the opposite direction, originally through colonisation and reflected, in the adoption of the temple and Greek deities, for example, the Hieron on the Bosporus dedicated to Zeus Ourios in the Hellenistic period and previously other Greek deities (Moreno, 2008, pp. 658–679 and Appendix 1 for Zeus Ourios Ancient Testimonia and Inscriptions) The Aegean, in any case, also reduced their reliance in the Classical period on the Black Sea for grain, with Cyrene, Sicily and Egypt filling the gap in supply (Figure 5).

Hellenistic period. Top: Trading Links (Appendix 3, Table A5). Below: Art and Architecture influences and development (Appendix 3, Table A6). Node size indicates the strength and ranking by Outdegree for trade exports and artistic Influence. Some nodes may not be in their correct geographic position placed on the edge of the map for visibility.

Hellenistic Period node degree centrality ranking (number of trading connections) illustrated by node size and colour shade, with 70 nodes and 306 links of commercial exchange based on archaeology and other ancient sources. Some nodes may not be in their correct geographic position placed on the edge of the map for visibility.

Athens’s maritime dominance in the Classical period was down to its fleet, which it retained until the Battle of Amorgos in 322 B.C.E, marking the end of Athenian power and political independence (Bresson, 2016, p. 304). New powers flexed their military muscle in Alexander’s conquered territories. Ptolemy, who inherited Egypt, and the Antipater/Antigonid dynasties, who retained Macedon and Greece (Freeman, 2011, p. 321). Delos would fall under their influence, if not under direct political control, in respect of culture, religion, and trade. Within 7 years of the “liberation” of Delos from Athens in 314 B.C.E., the League of the Islanders, an island alliance, was set up with its religious centre on Delos, which also incorporated the cult of Antigonus (Billows, 1990, p. 222; Buraselis, 1982). Following the Roman victory in the Macedonian wars, they rewarded Delos by making it a free port at the expense of the Rhodians and Corinthians (Strabo, Geography, 14.5.4). The catalyst for the influences, as demonstrated above, was the international travel of merchants and mercenaries (Barret, 2011, p. 23). Delos became a powerful commercial node, as measured by its high centrality ranking earned by virtue of its commercial connections as an exchange hub and by leveraging its political relationships and geographical position (Figure 5). Black Sea grain supplies continued, with Rhodes and Delos acting as intermediaries and reducing this dependency by sourcing grain from Sicily, North Africa and Egypt (Casson, 1954, pp. 171–174, 187; Reger, 1994, p. 53). Cyrene also supplied direct to the Aegean and mainland. Olive oil from Egypt was also transited through Rhodes and then to Delos and other Cycladic islands (Grace & Savvatianou-Pétropoulako, 1970, Ch. 14; Reger, 1994, pp. 29, 67–69, 265). Delos wine suppliers include Kos, Apulia, Campania, Knidos, Thasos and Rhodes and olive oil from Rhodes, Egypt, Italy and Sicily. Enslaved persons move from the east to the west through Delos, described by Strabo (Geography, 14.5.2) as a slave market. Macedon and Phoenicia remain an essential timber source for the sanctuary. Delos was also an established centre for banking (Bresson, 2016, p. 392; Cohen, 1997, p. 114).

There is a distinct difference in the architecture development by the earlier Ptolemaic and Antigonids dynasties, who favoured temple and sanctuary development and the later Romans, whose developments were of a domestic and commercial nature along with Athenian and Levantine settlers. Their presence also influenced the introduction of distinct styles in sculpture and subtle influences in mosaic and wall painting, some of which, in turn, influenced later Italian design. A temple dedicated to the twelve Olympian gods, including an idealised portrait of a Hellenistic sovereign, was constructed as early as 290 B.C.E and identified as the Dodekatheon. The Antigonids probably funded this development (Bruneau & Ducat, 2005, pp. 216–217). Later in this century, a monumental stoa, which an inscription indicates is associated with Antigonus Gonatas, had projecting wings and elaborate sculptural decorations (XI. 4 1095 = Choix 35). The forty-seven Doric columns were fluted only on the upper portion, and there was an Ionic inner colonnade of 19 columns. On the Doric entablature, the frieze triglyphs alternate with embossed marble heads of bulls (Figure 6). Similar bull head figures appear at the Hellenistic site of Didyma, which bears a striking resemblance if not a baroque interpretation. In 210 B.C.E, Philip V of Macedonia built a stoa, as attested by an inscription (IG XI. 4 1099 = Choix 57). His great-grandfather built the Doric Monument of the Bulls/Neorion, which housed a trireme as a dedication to Apollo. Pausanias (Description of Greece, 1.29.1) famously described a ship with nine rows of oars on display at Delos.

Portion of the frieze of the Stoa of Antigonus, c.240 B.C.E. (Photo: D Grant).

The goddess Aphrodite, and especially Aphrodite Euploia, saviour of the shipwrecked and protectress of sailors and the navy, was especially associated with the Ptolemies, as was the Aphrodision of Stesileos constructed c.305 B.C.E. All these beneficiaries of her protection would have promoted her cult on their travels (Constantakopoulou, 2017, pp. 80–81; Marquaille, 2001, pp. 195–200; Papantoniou, 2012, p. 195). While the Ptolemies were not as prolific as the Antigonids in monumental building projects, the representation of Egyptian cults in sculpture and figurines is present in both the temple and domestic sphere.

The attraction of the Sarapis to Ptolemy I and the leaders that followed relates to the god’s optimistic prophecy revealed in a dream of a great future for Ptolemy and his kingdom. Isis and Sarapis appear together in the sculpture relief of Agathodaimon, which includes Egyptian snake imagery. Sarapis is also conflated with Zeus in the statue of Sarapis as a semi-nude figure. Syncretism, where the same divinity generates diverse iconographical and onomastic representations, can also be seen in a statue of the Egyptian goddess Isis, identifiable only by its location in the Doric Temple of Isis (Figure 7), where the Isis sculpture’s format could easily be confused with an Aphrodite type. Isis takes over the Greek goddess’s composition, is dressed in a chiton and mantle, and is moving forward. Pakkanen believes that this does not undermine faith, as a polytheistic system is flexible, fluid and syncretistic in nature. Visual representations of divinities were adapted to better suit and respond to new cultural contexts (Pakkanen, 2011, p. 135). The “Oriental Aphrodite” with a multi-tiered crown incorporating vegetal elements and radiate rays is a Hellenised example of a figurine manufactured in a Greek tradition but wears unusual clothing that combines a range of Greek, Near Eastern, and Egyptian influences. Pottier and Reinach, who coined the term “Oriental Aphrodite,” saw these figurines as a syncretism of Aphrodite with Near Eastern goddesses such as Astarte or Anat. This was an open international community engaged in exchanging ideas and technology. To make Egyptian iconography more understandable or recognisable for locals, producers and consumers of these figurines opted to employ a strategy of active syncretism (Barret, 2011, pp. 26–35, 160).

Temple of Isis and Statue of Isis. Sarapieon. Mid-Hellenistic period (Photos: D Grant).

The earliest dated examples of female statue styles, popular later in the Roman imperial period, are found on Delos, the “Pudicitia” and the “Small Herculaneum” type (Smith, 1991, p. 257). The “Pudictia” style, which has its roots in grave reliefs from Asia Minor and the Aegean, attempts to display a chaste, virtuous, and modest woman (Pfuhl & Möbius, 1977). The “Small Herculaneum” type shows a woman pulling the end of her mantle up over her shoulder in a gesture of modesty. Both these body types were widely used for portraits of Roman women. The veristic Roman style of portrait sculpture expressing a harsh and severe realism implying favoured Roman virtues of simplicitas and gravitas can be seen in a female portrait and the Pseudo-Athlete, both from the House of the Diadoumenos with the latter displaying a Roman veristic head but with an idealised Greek body (Bremen, 1996, p. 166; Fejfer, 2008, pp. 89–90; Kleiner 1992, pp. 34–36; Richter 1955, pp. 39–46).

The Delos emporium attracted Roman, Athenian and Levantine traders to settle and construct lavish villas with external colonnades like those along the façade of the House of the Dolphins, House of the Masks and House of the Trident (Figure 8). The high concentration of numerous commercial facilities near the port, at accessible locations and near the sanctuary of Apollo confirms the importance of commerce to Delos (Karvonis, 2008, p. 217). A typical late Republican Italian country villa type can be seen in the design of Maison de Fourni, on a roadside facing the countryside with rooms related to agricultural and craft activities (Archibald et al., 2012, pp. 89–90). The floor plan appears to indicate rooms for rent at the House of the Trident and of the Masks. In the House of the Trident (Figure 8), on a column of its Rhodian peristyle, symbols of the Syrian deities Atargatis and Hadad appear, suggesting the home of a Syrian merchant (Westgate, 2000, p. 401). Decoration of these homes also reflects the influence of international trading connections, with wall paintings and mosaics echoing Macedonian and Roman styles and motifs. This combination of commerce with luxury is a common Roman architectural and property management strategy, as seen in houses and villas in Italy (Zarmakoupi, 2015, p. 123). Examples include a coroplast who operated at House VI B in the Theater District and a marble worker at the House of Kerdon. The design of commercial buildings in the Theatre Quarter and the South Quarter come from the Roman world, including warehouse buildings from Ostia and buildings associated with commerce and crafts from Rome and Ostia (Karvonis, 2008, pp. 196, 208).

House of the Trident. Atargatis and Hadad. c.150–100 B.C.E. (Photo D Grant).

Delos has a substantial corpus of inscriptions, mainly from the Hellenistic period, recording honours and dedications. Constantakopoulou, 2017, compiled lists of the ethnicity of dedicators and of those honoured, which are presented above in a summary graph form (Figure 9). Honorific decrees were issued by the demos and the Boule of the Delians to award the status of proxenos, an official friend of the polis. Honours could also be given by way of mention in Delian accounts for dedications of statues and exedras. The inventories record the objects and often the ethnicity of dedicants to the Delian deities.

Delian Honours (Left), Dedications record in the Delian Inventories (Right) by ethnicity. The number and link thickness represent quantities.

Examples of an honorary decree are two decrees to honour Autocles, son of Autocles, from Chalkis, from c.230 B.C.E who is described as a good man with regard to the sanctuary and demos who provided services to the city as a whole and the citizens (IG XI.4 681 and 682). On inventory lists, there is a dedication by Queen Stratonike from 250 B.C.E (IG XI.2 287B 64–72), which includes golden crowns on the wall of the Temple of Apollo (Constantakopoulou, 2017, pp. 176, 122). Connecting honours to commerce include decrees relating to the role of the Rhodian navy in protecting trade, including against the activity of pirates, and indicating the vulnerability of the island and dependence on others for protection. Economy and trade, with a wide description of the activities thereof, appear closely, but not solely related, to the award of proxeny linking Delos with the honorand (IG XI.4 596 = Choix 39; IG XI.4 1135 = Choix 40; (Constantakopoulou, 2017, p. 149). The greater number of honours appear to be from nearby Cycladic islands, Attica, Peloponnese and Asia Minor coastal regions and islands, with only the latter correlating significantly with trade links (Figure 4). Rhodes and its proximate neighbour, Kos, have the highest numbers of honours and dedications, which is not surprising because of strong trade links with Delos, its role as protector, and confirming stronger commercial relationships than just a waypoint node on passing trade routes. Despite Egypt and Macedon being rich in trade and art and architecture links to Delos, they do not register significantly for honours but do for dedications, which probably relates to their investment in the sanctuary through big gestures in temple developments. Italy and Phoenicia’s trade volume would have come later in the Hellenistic period to most of these honours and dedications, so no correlation should be expected. In summary, those nodes with links nearer to Delos seem to fare on average better in honours recognition stakes, but the distance does not appear to matter so much with dedications.

7 Conclusion

Other than for subsistence, early trade connections substantially relate to the supply of materials for the development of the sanctuary. This does not factor in Delos acting as a stopover for trade between other locations. Later, a normalised trade network developed with Delos becoming an emporium and highly central node (Figure 5). Connections widened to include Attica, Asia Minor, the states of the former Macedonian empire and the Romans, all bringing their culture and cults, which will be assimilated, as if by osmosis, in the styles and use of art and architecture at Delos. It is not surprising that the impact of trade connections would extend beyond commercial relationships to influence the style and iconography of cultic practice employed in the development of the sanctuary and in domestic and commercial construction and decoration. The former driven by the religious practice and ideological influence of sailors and merchants as well as kings investing in displays of power, and the latter arising from the profits of foreign merchants settling in Delos. The symbiotic relationship between commerce and religion is considered by many scholars, including Kowalzig, who suggests that religious connections reflect commercial ties with sanctuaries as nodes on networks and ideologies transmitted by mariners (Kowalzig, 2018). This would include how religion is expressed in art and architecture, a common source to trade links as demonstrated above and, as a driver of dedication practice, recorded in the Delian inventories at the sanctuary. These maps also illustrate how Malkin’s (2011) theory on the spread of Greek culture can be facilitated by trade and how the small Greek world continues to be inspired by other cultures as trade networks expand.

Acknowledgements

I wish to acknowledge the continued guidance and support of my supervisor, Dr Giorgos Papantoniou, Assistant Professor in Ancient Visual and Material Culture in the Department of Classics at Trinity College Dublin.

-

Funding information: The research conducted in this publication was funded by a Government of Ireland Postgraduate Scholarship through the Irish Research Council under grant number GO I PG/2023/3956. The Open Access status of this article has received funding from the Centre of Excellence in Ancient Near Eastern Empires, funded by the Research Council of Finland (decision number 352748).

-

Author contributions: The author confirms the sole responsibility for the conception of the study, presented results and manuscript preparation.

-

Conflict of interest: The author states no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: All the main data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article in the appendices or available publicly with references included. The data used to construct the network in Figure 5 were compiled by the author from publicly available sources, details of which will be shared on reasonable request.

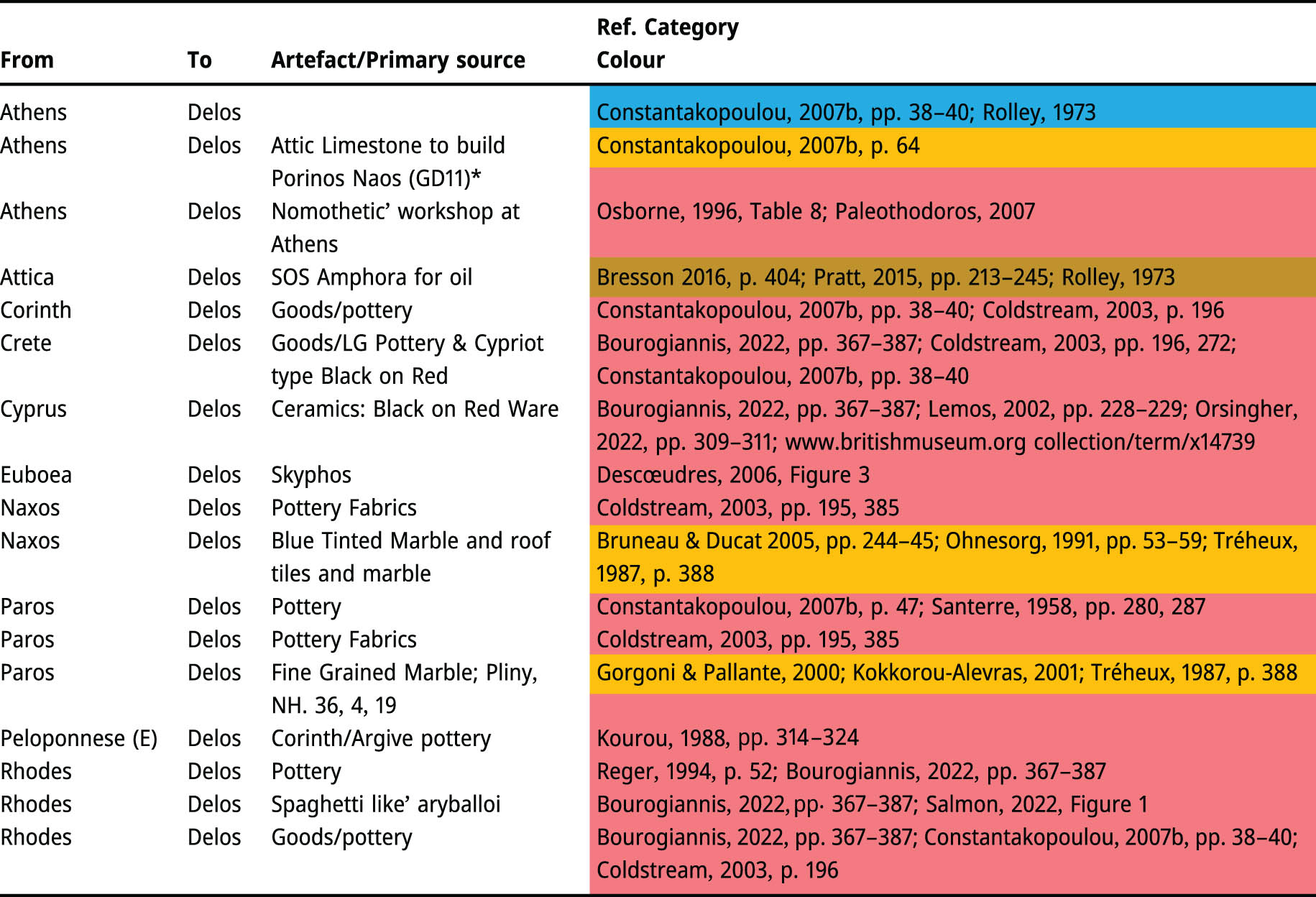

Appendix 1 Archaic Period

Archaic period – Trade links

|

*GD reference is Delos site reference on the official map.

Archaic period – Art and architecture links

| From/Influence | Art and architecture | Ref. |

|---|---|---|

| Andros | Oikos of the Andrians (GD43) | Hamilton, 2000, p. 367 |

| Athens | Porinos Naos (GD11) | Boersma, 1970, p. 17; Constantakopoulou, 2007, p. 64 |

| Chios | Nike of Archermos “Chian Style” | Pedley, 2012, p. 279; Romano, 2006, p. 234; Sheedy, 1985, p. 619 |

| Corinth | Fineware. Slim ovoid body | Coldstream, 2003, p. 68–69 |

| Euboea | Oikos of the Carystians (GD 16) | |

| Euboea | Fineware | Coldstream, 2003, pp. 175, 180 |

| Euboea | Euboea Cesnola painter themes. Static female dance | Coldstream, 2003, p. 195 |

| Greek East | Ivory Sea. East Greek type: a recumbent lion | Coldstream, 2003, p. 140 |

| Keos | Hestiatorion | Herodotus The Histories, 4.35.4 |

| Naxos | Oikos of the Naxians (GD6) | Bruneau & Ducat, 1983, p. 121; Mackill, 2013, p. 191f |

| Naxos | The Nikandre Statue. Naxos family | IG xii, 5.2, p. xxiv; SGDI 5423; ID II, 1; Jefferys LSAG 303 |

| Naxos | Upper part of kouros | Bruneau & Ducat, 1983, pp. 56–64 |

| Naxos | Naxian korai A, b and C. Flat profile | “ |

| Naxos | Porches added to Oikos of the Naxians (GD6) | Constantakopoulou, 2007, p. 43; Gruben, 2000, p. 164 |

| Naxos | Naxian roof tile marble on Oikos | Ohnesorg, 1991, pp. 53–59 |

| Naxos | Naxian Lions (up to 19?) | Bruneau & Ducat, 2005, pp. 244–245; Barlou 2014, 137(Note 10) & 139–44 |

| Naxos | Fineware | Coldstream, 2003, pp. 68–69, 195 |

| Paros | Fineware | “ |

| Paros | Parian kouros. Island sculpture | Bruneau & Ducat, 1983, pp. 56–66 |

| Paros | The Parian sphinx pf Parian marble | Bruneau & Ducat, 1983, pp. 64–65 |

| Paros | Monument of Hexagons (GD44). Oikos. Stylistic design | Bruneau & Ducat, 1983, pp. 64–65 |

| Paros | Letoon Temple (GD53). Parian Decorative pattern | Santerre, 1958, pp. 257–258 |

| Thasos | Decorative pattern on Monument of Hexagones | Hellmann & Fraisse, 1979, pp. 73–75 |

*GD reference is Delos site reference on the official map.

Appendix 2 Classical Period

Classical period – Trade links

|

Classical period – Art and architecture links

| From | Art and architecture | Style/Material | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Athens | Temple of the Delians (GD13) | Doric peripteral configuration like Temple of Artemis Corfu | Smarczyk, 1990, p. 465; Constantakopoulou, 2017, p. 70 |

| Athens | Temple of Athenians (GD12) | Amphiprostyle design with six Doric columns | Constantakopoulou, 2007, p. 72 |

| Athens | Temple of Athenians (GD12) | Greek Theme on Acroterion: Abduction of Oreithyia by Boreas. | Boersma, 1970, p. 171 |

| Athens | Temple of Athenians (GD12) | Callicrates, craftsman of the Temple of Nike on the Acropolis. | Schultz, 2001, p. 17 |

| Measurements of the temple’s lateral acroteria same as Nike and Delphi treasury | |||

| Athens | The Prytaneion (GD22) | Insular style | Buckingham, 2012 |

Appendix 3 Hellenistic Period

Hellenistic period – Trade links

|

Hellenistic period – Art and architecture links

| From/Influence | Art and architecture | Syncretism/Style | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anatolia | Orthostats from the House of the Masks | Like Sphinx Gate, Alaca Höyük | Harmanşah, 2013, p. 157 |

| Athens | Cleopatra and Dioskourides statues from House of Cleopatra | Pudictia’ style, roots in grave reliefs from Asia Minor and the Aegean | Dillon, 2013; Pfuhl & Möbius, 1977, pp. 205–206 |

| Athens | Head of young woman from the House of Dionysus. | Hellenistic female portraiture with conventional ideals of female beauty | Dillon, 2013, pp. 212–214 |

| Athens | The Diadumenos (diadem-bearer) | “neo-Attic” academicism in Greco-Roman art, a reversion to classical types, | Bruneau & Ducat, 1983, p. 71 |

| Athens | Pseudo-Athlete | Roman veristic head with an idealised Greek body | Kleiner, 1992, pp. 34–36 |

| Athens | Decorative friezes from houses in the Stadium District | Greek themes with no hint of syncretism | Bruneau & Ducat, 1983, p. 83 |

| Athens | House of the Masks, theatrical, Panathenaic prize amphorae motifs | Style, technology and narrative are Greek | |

| Beirut | Establishment of Poseidoniasts | Small temples to Baal-Posidon, Astarte-Aphrodite and Esmund- Acespeilos | Lipiński, 2004, p. 166 |

| Corinth | Corinthian style aryballos, | Decorated with dogs, was found at the Heraion | |

| East | House of Dionysus | Stucco, an oriental art form | Westgate, 2000, p. 412 |

| Egypt | Philadelpheion: Later called the Temple of Agathe Tyche | Sanctuary for the cult of Arsinoe Philadelphus, sister and wife of Ptolemy II. To honour a new goddess of the Delian pantheon, a link to Ptolemaic Royal circles | Constantakopoulou, 2017, p. 98 |

| Egypt | Aphrodision of Stesileos | Ptolemy influence on deities | IG XI 4, 1247 = RICIS 202/0124 = ID 4756; Antoniadis, 2022; Constantakopoulou, 2017, pp. 80–86 |

| Egypt | Sarapieion, founded by Apollonios | Ptolemy influence on deities | “ |

| Egypt | Sarapeion A | Nilometres created from tunnel to Inopos river | Barret, 2011, p. 133; Richter, 2010, p. 161 |

| Egypt | Isis and Serapis. Relief of Agathodaimon | Syncretism of deities. Ptolemy influence | Pakkanen, 2011, p. 134 |

| Egypt | Doric Temple of Isis, Terrace of the Foreign Gods | Doric | |

| Egypt | Statue of Isis. Sarapieon | Isis sculpture’s format as Aphrodite type | Pakkanen, 2011, p. 135 |

| Egypt | The “Oriental Aphrodite” figurine | 1500 published terracotta figurines, 82 represent Egyptian deities, only 3 imported | Barret, 2011, pp. 86–87; Marcadé, 1969, pp. 408–417 |

| Egypt | “Harpocrates” figurine | Syncretism of deities | Barret, 2011, p. 411 |

| Greco/Rome | The “Oriental Aphrodite” figurine | 1500 published terracotta figurines, include Greco-Roman examples | Barret, 2011, pp. 86–87; Marcadé, 1969, pp. 408–417 |

| Italy | Establishment of Poseidoniasts and goddess Roma adoption of Roman styles | ||

| Italy | La Maison de Fourni | Late Republican Italian villa syyle | Archibald et al., 2012, pp. 89–90 |

| Italy | Agora of the Italians honorific statues | Italians honorific statues | Dillon, 2013, pp. 217–219 |

| Italy | Lake House | Small Herculaneum type | |

| Italy | Pseudo-Athlete Female portrait from the “House of the Diadoumenos” | Veristic form was popular for Roman male portraits | Bremen, 1996, p. 166; Fejfer, 2008, pp. 89–90 |

| Macedon | Demetrius. Monument of the Bulls/Neorion (GD24) | Doric style | Pausanias, Description of Greece, 1.29.1 |

| Macedon | Dodekatheon (GD51) | Idealised portrait of a Hellenistic sovereign | Bruneau & Ducat, 2005, pp. 217–217; Constantakopoulou 2017, p. 98 |

| Macedon | Antigonus’ Stoa (GD29) | Doric entablature, triglyphs alternate with embossed marble heads of bulls | XI. 4 1095 = Choix 35 |

| Macedon | Philip V Stoa | IG XI. 4 1099 = Choix 57 | |

| Macedon | Figurative wall paintings equine | Macedon influences are evident in equine scenes | |

| Macedon | Mosaic House of Dionysus | Similarity to Stag Hunt, Mosaic. Pella | |

| Macedon/N.Greece | House of the Dolphins | External stoas or verandas | Papaioannou, 2018, pp. 359–360 |

| Macedon/N.Greece | House of the Masks | External stoas or verandas | “ |

| Pergamum | Stoa and Statue | IG XI. 4 1109 = Choix 53; Bringmann & von Steuben, 1995, p. 221 | |

| Phoenicia | Sanctuary of the Syrian Gods | ||

| Phoenicia | House of the Triton | Rhodian Peristyle and Syrian deities Atargatis and Hadad. Also, rental space | Westgate, 2000, p. 401; Zarmakoupi, 2015, p. 123 |

| Rhodes | House of the Triton | Rhodian Peristyle and Syrian deities Atargatis and Hadad. Also, rental space | “ |

| Rome | Wall paintings of chariot/horse racing, hunting, sacrifice and boxing | Activities associated with the Roman festival of the Compitalia | Stek, 2008, p. 115 |

References

Angliker, E. (2017). Worshipping the Divinities at the Archaic Sanctuaries in the Cyclades. In Les Sanctuaires Archaiques Des Cyclades. Presses universitaires de Rennes.Search in Google Scholar

Antoniadis, V. (2022). Objectifying faith: Managing a private sanctuary in Hellenistic Delos. The Journal of Archæological Numismatics, 12, 123–136. https://www.academia.edu/120245480/Objectifying_faith_managing_a_private_sanctuary_in_Hellenistic_Delos.Search in Google Scholar

Archibald, Z., Morgan, C., Smith, D., Stamatopoulou, M., Bennet, J., Haysom, M., Ainian, A. M., & Sweetman, R. (2012). Archaeology in Greece 2012-2013. Archaeological Reports, 59, 1–119.10.1017/S0570608413000033Search in Google Scholar

Badoud, N. (2014). The contribution of inscriptions to the chronology of Rhodian Amphora. In P. G. Bilde & M. L. Lawall (Eds.), Pottery, peoples and places. Aarhus University Press. https://www.academia.edu/13385153/The_Contribution_of_Inscriptions_to_the_Chronology_of_Rhodian_Amphora_Eponyms.10.2307/jj.608198.5Search in Google Scholar

Barlou, V. (2014). The Terrace of the Lions on Delos: Rethinking a Monument of Power in Context. In G. Bonnin & E. Le Quéré (Hrsg.), Pouvoirs, îles et mer: Formes et modalités de l’hégémonie dans les Cyclades antiques (VIIe s. A.C. – IIIe s. P.C.), Bordeaux, 13.-15.6.2012 (Bordeaux 2014) 135-16 (pp. 135–160). Ausonius Éditions. https://www.academia.edu/8747595/The_Terrace_of_the_Lions_on_Delos_Rethinking_a_Monument_of_Power_in_Context_in_G._Bonnin_E._Le_Qu%C3%A9r%C3%A9_Hrsg._Pouvoirs_%C3%AEles_et_mer_Formes_et_modalit%C3%A9s_de_l_h%C3%A9g%C3%A9monie_dans_les_Cyclades_antiques_VIIe_s._a.C._IIIe_s._p.C._Bordeaux_13.-15.6.2012_Bordeaux_2014_135-160.Search in Google Scholar

Barret, C. (2011). Egyptianizing figurines from Delos. A study in Hellenistic religion. Brill.10.1163/9789004222663Search in Google Scholar

Billows, R. A. (1990). Antigonos the One-eyed and the Creation of the Hellenistic State. University of California Press.10.1525/9780520919044Search in Google Scholar

Boer, J. D. (2013). Stamped amphorae from the Greek Black Sea colony of Sinope in the Mediterranean during the Hellenistic period. Proceedings of the Fourth International Congress on Black Sea Antiquities (pp. 109–114). https://www.academia.edu/3818119/Stamped_amphorae_from_the_Greek_Black_Sea_colony_of_Sinope_in_the_Mediterranean_during_the_Hellenistic_period.Search in Google Scholar

Boersma, J. (1970). Athenian Building Policy from 561/0 to 405/4 BC. Wolters-Noordhoff Publishing.Search in Google Scholar

Borgatti, S., Carley, K., & Krackhardt, D. (2006). On the robustness of centrality measures under conditions of imperfect data. Social Networks, 28, 124–136. doi: 10.1016/j.socnet.2005.05.001.Search in Google Scholar

Borgatti, S. P., & Li, X. (2009). On social network analysis in a supply chain context. Journal of Supply Chain Management, 45(2), 5–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-493X.2009.03166.x.Search in Google Scholar

Boulay, T. (2012). Les techniques vinicoles grecques, des vendanges aux Anthestéries: Nouvelles perspectives. Dialogues d’histoire Ancienne., Supplément 7, 95–115.10.3406/dha.2012.3531Search in Google Scholar

Bourogiannis, G. (2022). Cypriot Black-on-Red pottery in Early Iron Age Greece. In search of a beginning and an end. In Beyond Cyprus: Investigating Cypriot Connectivity in the Mediterranean from the Late Bronze Age to the End of the Classical Period (Vol. 9, pp. 367–387). http://epub.lib.uoa.gr/index.php/aura/article/view/2322.Search in Google Scholar

Bremen, R. V. (1996). The Limits of Participation: Women and Civic Life in the Greek East in the Hellenistic and Roman Periods. Dutch Monographs on Ancient History and Archaeology.Search in Google Scholar

Bresson, A. (2016). The Making of the Ancient Greek Economy: Institutions, Markets, and Growth in the City-States (S. Rendall, Trans.). Princeton University Press. doi: 10.2307/j.ctt21c4v6h.Search in Google Scholar

Bringmann, K., & von Steuben, H. (Eds.). (1995). Schenkungen hellenistischer Herrscher an griechische Städte und Heligtümer. Zeugnisse und Kommentare (Vol.1). De Gruyter Akademie Forschung.10.1524/9783050068930Search in Google Scholar

Bruneau, P. (1970). Recherches sur les cultes de Délos à l’époque hellénistique. French School of Athens.Search in Google Scholar

Bruneau, P., & Ducat, J. (1983). Guide de Délos. French School of Athens.Search in Google Scholar

Bruneau, P., & Ducat, J. (2005). Guide de Délos (4th ed.). French School of Athens.Search in Google Scholar

Brunet, M. (2016). Delos – the rural areas. Ecole Francaise Athenes. https://www.efa.gr/delos-le-territoire-rural-3/?lang=en.Search in Google Scholar

Buckingham, E. (2012). Delian civic structures: A critical reassessment. University of North Carolina]. https://www.academia.edu/8965244/Delian_Civic_Structures_A_Critical_Reassessment.Search in Google Scholar

Buraselis, K. (1982). Das hellenistische Makedonien und die Ägäis: Forschungen zur Politik des Kassandros und der drei ersten Antigoniden (Antigonos Monophthalmos, Demetrios Poliorketes und Antigonos Gonatas) im Ägäischen Meer und in Westkleinasien. C.H. Beck.Search in Google Scholar

Carlson, D. (2013). A view from the sea: The archaeology of maritime trade in the 5th century BC Aegean. In Trade and Finance in the 5th C. BC Aegean World (pp. 1–25). Zertifikat-Nr.Search in Google Scholar

Casson, L. (1954). The grain trade of the Hellenistic world. John Kopkins University/American Philological Association.10.2307/283474Search in Google Scholar

Casson, L. (1971). Ships and seamanship in the ancient world. Princeton University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Chankowski, V. (2008). Athènes et Délos à l’époque classique. Recherches sur l’administration du sanctuaire d’Apollon délien. BEFAR.Search in Google Scholar

Cohen, E. (1997). Athenian economy and society: A banking perspective. Princeton University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Coldstream, J. N. (2003). Geometric Greece: 900-700 B.C. Routledge.10.4324/9780203425763Search in Google Scholar

Collar, A. (Ed.). (2022). Networks and the spread of ideas in the past: Strong ties, innovation and knowledge exchange. Routledge. https://www.routledge.com/Networks-and-the-Spread-of-Ideas-in-the-Past-Strong-Ties-Innovation-and/Collar/p/book/9781138368477.10.4324/9780429429217Search in Google Scholar

Constantakopoulou, C. (2007). The dance of the islands insularity, networks, the Athenian empire and the Aegean world. Oxford University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Constantakopoulou, C. (2015). Regional religious groups, Amphiktionies and other leagues. In E. Eidinow & J. Kindt (Eds.), Oxford handbook of ancient Greek religion. Oxford Academic.10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199642038.013.20Search in Google Scholar

Constantakopoulou, C. (2017). Aegean interactions: Delos and its networks in the third century. Oxford University Press.10.1093/oso/9780198787273.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Curtis, R. I. (1991). Garum and Salsamenta: Production and commerce in Materia Medica. Brill.10.1163/9789004377264Search in Google Scholar

Davis, J. J. (1982). Thoughts on prehistoric and Archaic Delos’. Temple University Aegean Symposium, 7, 23–33.Search in Google Scholar

Descœudres, J. P. (2006). Euboean pottery overseas (10th to 7th Centuries Bc). Mediterranean Archaeology, 19/20, 3–24.Search in Google Scholar

Dillon, S. (2013). Portrait Statues of Women on the Island of Delos. In E. Hemelrijk & G. Woolf (Eds.), Women and the Roman City in the Latin West (pp. 201–223). Brill. https://www.academia.edu/38348037/Portrait_Statues_of_Women_on_the_Island_of_Delos.10.1163/9789004255951_012Search in Google Scholar

Dimitrova, A. (2022). Beyond Cyprus the evidence from the Black Sea. In G. Bourogiannis (Ed.), Beyond Cyprus: Investigating Cypriot Connectivity in the Mediterranean from the Late Bronze Age to the End of the Classical Period (pp. 437–448). Athens University Review of Archaeology.Search in Google Scholar

Durrbach, F. (1977). Choix d’inscriptions de Délos avec traduction et commentaire (Reprint 1977). E. Leroux.Search in Google Scholar

Durrbach, F., & Roussel., P. (1935). Inscriptions de Délos: Actes des fonctionnaires athéniens préposés a l’administration des sanctuaires après 166 av. J.-C (numéros 1400-1479); fragments d’actes divers (numéros 1480-1496)/publiés. https://stella.catalogue.tcd.ie/iii/encore/record/C__Rb12917019__SFelix%20Durrbach__Orightresult__U__X4?lang=eng&suite=cobalt.Search in Google Scholar

Dzierzbicka, D. (2018). OINOS. Production and import of wine in Graeco-Roman Egypt. University of Warsaw; Raphael Taubenschlag Foundation.Search in Google Scholar

Fejfer, J. (2008). Roman portraits in context. De Gruyter.10.1515/9783110209990Search in Google Scholar

Finkielsztejn, G. (2011). Black Sea amphora stamps found in the southern Levant Most probably not a trade. In C. Tzochev, T. Stoyanov, & A. Bozkova (Eds.), PATABS II. Production and Trade of Amphorae in the Black Sea. National Institute of Archaeology with Museum (Bulgarian Academy of Sciences)/“St. Kliment Ohridski” Sofia University. https://www.academia.edu/4248997/2011_Black_Sea_Amphora_Stamps_Found_in_the_Southern_Levant_Most_Probably_not_a_Trade_PATABS_II?auto=download&email_work_card=download-paper.Search in Google Scholar

Freeman, P. (2011). Alexander the Great. Simon & Schuster.Search in Google Scholar

Garlan, Y. (2007). Échanges d’amphores timbrées entre Sinope et la Méditerranée aux époques classique et hellénistique. In V. Gabrielsen & J. Lund (Eds.), The Black Sea in antiquity (pp. 143–148). Aarhus University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Gorgoni, C., & Pallante, P. (2000). On Cycladic marbles used in the Greek and Phoenician colonies of Sicily. In D. U. Schilardi & D. Katsonopoulou (Eds.), Paria Lithos: Parian Quarries, Marble and Workshops of Sculpture (pp. 497–506). The Paros and Cyclades Institute of Archaeology.Search in Google Scholar

Grace, V. R., & Savvatianou-Pétropoulako, M. (1970). L’llot de la Maison des comédiens. French School of Athens.Search in Google Scholar

Granovetter, M. (1983). The strength of weak ties: A network theory revisited. Sociological Theory, 1, 201–233.10.2307/202051Search in Google Scholar

Greene, E. S. (2018). Shipwrecks as indices of Archaic Mediterranean trade networks. In J. Leidwanger & C. Knappet (Eds.), Maritime networks in the ancient Mediterranean world. Cambridge University Press.10.1017/9781108555685.007Search in Google Scholar

Gruben, G. (2000). Heiligtumer und Tempel der Griechen. Hirmer.Search in Google Scholar

Hadjidakis, P. I. (2017). A small tavern in ancient Delos. In N. C. Stampolidis, D. Tsangari, & Y. Tassoulas (Eds.), Money. Tangible symbols in ancient Greece (pp. 323–349). Museum of Cycladic Art. https://www.Hadjidakiscademia.edu/38116753/A_small_tavern_in_ancient_Delos.Search in Google Scholar

Hadjidakis, P. J. (n.d.). Label: Temple of the Athenians. Delos Museum.Search in Google Scholar

Hamilton, R. (2000). Treasure Map: A Guide to the Delian Inventories. Ann Arbor.10.3998/mpub.16411Search in Google Scholar

Harmanşah, Ö. (2013). Upright Stones and Building Stories: Architectural technologies and the poetics of urban space. In Cities and the shaping of memory in the ancient Near East (pp. 153–188). Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9781139227216.007.Search in Google Scholar

Hellmann, M.-C., & Fraisse, P. H. (1979). Le monument aux hexagones et le portique des Naxiens (De´los 32). French School of Athens.Search in Google Scholar

James, S. A. (2010). The Hellenistic pottery from the Panayia Field, Corinth: Studies in chronology and context. (Doctoral dissertation, University of Texas at Austin). UT Electronic Theses and Dissertations. https://repositories.lib.utexas.edu/handle/2152/ETD-UT-2010-12-2355.Search in Google Scholar

Karvonis, P. (2008). Les installations commerciales dans la ville de Délos à l’époque hellénistique. BCH, 132, 153–219.10.3406/bch.2008.7500Search in Google Scholar

Kleiner, D. (1992). Roman sculpture. Yale University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Kokkorou-Alevras, G. (2001). The use and distribution of Parian Marble during the archaic period. Στο Παρία Λίθος, Πρακτικά Tου A΄ Διεθνούς Συνεδρίου Aρχαιολογίας Πάρου Kαι Kυκλάδων (pp. 143–153). Academia.Search in Google Scholar

Kourou, N. (1988). Handmade pottery and trade: The case of the “Argive Monochrome” ware. In J. Christiansen & T. Melander (Eds.), Proceedings of the 3rd Symposium on Ancient Greek and Related Pottery (pp. 314–324). Ny Carlsberg Glyptote.Search in Google Scholar

Kowalzig, B. (2018). Cults, cabotage, and connectivity. In C. Knappet (Ed.), Maritime networks in the ancient Mediterranean world. Cambridge University Press.10.1017/9781108555685.006Search in Google Scholar

Lawall, M. L., & Tzochev, C. (2020). New research on Aegean & Pontic transport amphorae of the ninth to first century BC, 2010–2020. Cambridge University Press on Behalf of the Society for the Promotion of Hellenic Studies and the British School at Athens, 66, 117–144.10.1017/S057060842000006XSearch in Google Scholar

Leidwanger, J., & Knappet, C. (2018). Maritime networks, connectivity, and mobility in the ancient Mediterranean. In J. Leidwanger & C. Knappet (Eds.), Maritime networks in the ancient Mediterranean world. Cambridge University Press.10.1017/9781108555685Search in Google Scholar

Lemos, I. (2002). The Protogeometric Aegean: The Archaeology of the Late Eleventh and Tenth Centuries BC. Oxford University Press.10.1093/oso/9780199253449.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Lewis, D. M. (2016). The market for slaves in the fifth and fourth-century aegean: Achaemenid anatolia as a case study. In E. M. Harris, D. M. Lewis, & M. Woolmer (Eds.), The ancient Greek economy (pp. 316–336). Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9781139565530.015.Search in Google Scholar

Lipiński, E. (2004). Itineraria phoenicia. Peeters.Search in Google Scholar

Mackill, E. (2013). Creating a common polity. Religion, economy, and politics in the making of the Greek Koinon. University of California.10.1525/9780520953932Search in Google Scholar

Malkin, I. (2011). A small Greek world: Networks in the Ancient Mediterranean. Oxford University Press.10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199734818.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Marasco, G. (1988). Economia, commerci e politica nel Mediterraneo fra il III e il II secolo a.c. Università degli studi di Firenze, dipartimento di storia, studi.Search in Google Scholar

Marcadé, J. (1969). Au Musée de Délos: Étude sur la sculpture hellénistique en ronde bosse découverte dans l’isle. Éditions E. de Boccard.Search in Google Scholar

Marquaille, C. (2001). The External Image of Ptolemaic Egypt. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). King’s College, University of London, UK.Search in Google Scholar

McGlin, M. J. (2019). Sacred Loans, Sacred Interest(s): An Economic Analysis of Temple Loans from Independent Delos (314-167 BCE). (Upublished doctoral dissertation). Graduate School of the University at Buffalo, The State University of New York, United States.Search in Google Scholar

Meiggs, R. (1972). The Athenian empire. Oxford University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Meiggs, R. (1982). Trees and timber in the ancient Mediterranean world (1st ed.). Oxford University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Mills, B. J. (2018). Navigating Mediterranean Archaeology’s Maritime networks in the ancient Mediterranean world. In J. Leidwanger & C. Knappet (Eds.), Maritime networks in the ancient Mediterranean world. Cambridge University Press.10.1017/9781108555685.011Search in Google Scholar

Morel, J.-P. (1986). Céramiques à vernis noir d’Italie trouvées à Délos. Bulletin de Correspondance Hellénique, 114, 461–493.10.3406/bch.1986.1810Search in Google Scholar

Moreno, A. (2007). Feeding the Democracy: The Athenian Grain Supply in the Fifth and Fourth Centuries BC. Oxford University Press.10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199228409.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Moreno, A. (2008). Hieron: The ancient sanctuary at the mouth of the Black Sea. Hesperia: The Journal of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens, 77(4), 655–709.10.2972/hesp.77.4.655Search in Google Scholar

Ohnesorg, A. (1991). Inselionische Marmordächer (Denkmäler antiker Architektur 18.2). Walter de Gruyter.Search in Google Scholar

Orsingher, A. (2022). Sailing east Networks, mobility, trade and cultural exchanges between Cyprus and the central Levant during the Iron Age. In G. Bourogiannis (Ed.), Beyond Cyprus: Investigating Cypriot Connectivity in the Mediterranean from Late Bronze Age to the End Of The Classical Period (pp. 305–322). Athens University Review of Archaeology.Search in Google Scholar

Osborne, R. (1994). Looking On – Greek Style: Does the Sculpted Girl Speak to Women Too? In I. Morris (Ed.), Classical Greece: Ancient histories and modern archaeologies (pp. 81–96). Cambridge University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Osborne, R. (1996). Greece in the Making 1200-479 BC (The Routledge History of the Ancient World). Routledge. Cambridge University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Pakkanen, P. (2011). Is it possible to believe in a syncretistic god? A discussion on conceptual and contextual aspects of Hellenistic syncretism. Opuscula. Annual of the Swedish Institutes at Athens and Rome, 4, 125–137.10.30549/opathrom-04-06Search in Google Scholar

Paleothodoros, D. (2007). Commercial networks in the Mediterranean and the diffusion of early Attic red-figure pottery (525–490 BCE). In I. Malkin, C. Constantakopoulou, & K. Panagopoulou (Eds.), Greek and Roman networks in the Mediterranean (pp. 158–175). Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781315876580-11.Search in Google Scholar

Papuci-Władyka, E. (2012). A Phoenician amphoriskos from Olbia in the collection of Jagiellonian University in Krakow. Notes on our research in the Ukraine. In W. Blajer (Ed.), Peregrinationes archaeologicae in Asia et Europa (pp. 565–572). Instytut Archeologii Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego: Wydawnictwo Profil-Archeo.Search in Google Scholar

Papaioannou, M. (2018). Villas in Roman Greece. In A. Marzano & G. P. R. Métraux (Eds.), The Roman villa in the Mediterranean basin. Late republic to late antiquity (pp. 327–375). Cambridge University Press.10.1017/9781316687147.021Search in Google Scholar

Papantoniou, G. (2012). Religion and social transformations in Cyprus: From the Cypriot basileis to the Hellenistic strategos. (Electronic resource). Brill. https://elib.tcd.ie/login?url=https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/trinitycollege/detail.action?docID=1081519.10.1163/9789004233805Search in Google Scholar

Parker, R. (1996). Athenian religion: A history. Oxford University Press.10.1093/oso/9780198149798.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Patabs, I., & Balabanov, P. (2010). Production and Trade of Amphorae in the Black Sea. Actes de la Table Ronde internationale de Batoumi et Trabzon, 27-29 avril 2006 (Vol. 21, No. 1). https://www.persee.fr/issue/anatv_1013-9559_2010_act_21_1.Search in Google Scholar

Pedley, J. (2012). Greek art and archaeology (5th ed.). Pearson.Search in Google Scholar

Peignard-Giros, A. (2014). La céramique d’époque impériale dans les Cyclades: L’exemple de Délos. Orient - Occident, 19(1), 417–433.10.3406/topoi.2014.2544Search in Google Scholar

Pfuhl, E., & Möbius, H. (1977). Die ostgriechischen Grabreliefs. Von Zabern, Mainz am Rhein.Search in Google Scholar

Pleket, H. W., & Bogaert, R. (1976). Epigraphica: Texts on bankers, banking and credit in the Greek world (Vol. III). BRILL.Search in Google Scholar

Pomeroy, S., Burstein, S., Donlon, W., Roberts, J. T., & Tandy, D. W. (2015). A brief history of ancient Greece. Oxford University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Pratt, C. E. (2015). The ‘SOS’ amphora: An update. Annual of the British School at Athens, 110, 213–245. doi: 10.1017/S0068245414000240.Search in Google Scholar

Rauh, N. (1993). The sacred bonds of commerce: Religion, economy and trade society at Hellenistic Roman Delos. J.C. Gieben.10.1163/9789004663459Search in Google Scholar

Reger, G. (1994). Regionalism and change in the economy of Independent Delos. University of California Press.Search in Google Scholar

Reynolds, P. (2013). Transport amphorae of the first to seventh centuries: Early Roman to Byzantine periods (Vol. II, pp. 93–161, Plates 43). The Packard Humanities Institute.Search in Google Scholar

Richardson, M., & Gajewski, B. (2002). Archaeological sampling strategies. Journal of Statistics Education, 10(3), 16. doi: 10.1080/10691898.2002.11910690.Search in Google Scholar

Richter, G. M. A. (1955). The Origin of Verism in Roman Portraits. The Journal of Roman Studies, 45, 155–186.10.2307/298742Search in Google Scholar

Richter, B. A. (2010). On the Heels of the Wandering Goddess: The Myth and the Festival at the Temples of the Wadi el-Hallel and Dendera. In H. Beinlich & M. Dolinska, (Eds.), Ägyptologische Tempeltagung: Beziehungen zwischen Tempeln (pp. 155–186). Harrassowitz.Search in Google Scholar

Rolley, C. (1973). Bronzes geometriques et orientaux a Delos. E´tudes De´liennes, BCH Suppl, 1, 491–523.10.3406/bch.1973.5076Search in Google Scholar

Romano, I. B. (2006). Classical sculpture: Catalogue of the Cypriot, Greek, and Roman stone sculpture in the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. https://1lib.eu/book/2885824/389317.10.9783/9781934536292Search in Google Scholar

Salmon, N. (2022). The “Spaghetti Workshop” of Rhodes Cypriot inspirations, Rhodian alterations. In G. Bourogiannis (Ed.), Beyond Cyprus: Investinging Cypriot Connectivity in the Mediterranean from the Late Bronze Age to the End of the Classical Period (pp. 389–397). Athens University Review of Archaeology.Search in Google Scholar

Santerre, H. G. D. (1958). Delos primitive et archai. French School of Athens.Search in Google Scholar

Schultz, P. (2001). The akroteria of the temple of Athena Nike. Hesperia: The Journal of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens, 70(1), 1–47. JSTOR. doi: 10.2307/2668486.Search in Google Scholar

Scott, M. (2014). Delphi: A history of the center of the ancient world. Princeton University Press.10.1515/9781400851324Search in Google Scholar

Sheedy, K. (1985). The Delian Nike and the search for Chian sculpture. American Journal of Archaeology, 89(4), 619–626. doi: 10.2307/504203.Search in Google Scholar

Smarczyk, B. (1990). Untersuchungen zur Religionspolitik und Politischen Propaganda Athens im Delisch-Attischen Seebund. Tuduv-Verlag-Gesellschaft.Search in Google Scholar

Smith, R. R. R. (1991). Hellenistic Sculpture: A Handbook. Thames and Hudson Ltd.Search in Google Scholar

Stek, T. D. (2008). A Roman Cult in the Roman Countryside? The Compitalia and the Shrines of the Lares Compitales. Babesch, 83, 111–132.10.2143/BAB.83.0.2033102Search in Google Scholar

Tréheux, J. (1987). L’Hieropoion et les Oikoi du Sanctuaire à Délos. In Servais et al. (Ed.), 1987, 377-390. – (1992): Inscriptions de Délos. Index, tome 1 : Les étrangers à l’exclusion des Athéniens de la clérouchie et des Romains, Paris.Search in Google Scholar

Westgate, R. C. (2000). Space and decoration in Hellenistic houses. The Annual of the British School at Athens, 95, 391–426.10.1017/S0068245400004743Search in Google Scholar

Zarmakoupi, M. (2015). Hellenistic and Roman Delos: The city and its emporion. Archaeological Reports, 61, 115–132.10.1017/S0570608415000125Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Etched in Stone: The Kevermes Stone Stela From the Great Hungarian Plain

- Waste Around Longhouses: Taphonomy on LBK Settlement in Hlízov

- Raw Materials and Technological Choices: Case Study of Neolithic Black Pottery From the Middle Yangtze River Valley of China

- Disentangling Technological Traditions: Comparative Analysis of Chaînes Opératoires of Painted Pre-Hispanic Ceramics From Nariño, Colombia

- Ancestral Connections: Re-Evaluating Concepts of Superimpositioning and Vandalism in Rock Art Studies

- Disability and Care in Late Medieval Lund, Sweden: An Analysis of Trauma and Intersecting Identities, Aided by Photogrammetric Digitization and Visualization

- Assessing the Development in Open Access Publishing in Archaeology: A Case Study From Norway

- Decorated Standing Stones – The Hagbards Galge Monument in Southwest Sweden

- Geophysical Prospection of the South-Western Quarter of the Hellenistic Capital Artaxata in the Ararat Plain (Lusarat, Ararat Province, Armenia): The South-West Quarter, City Walls and an Early Christian Church

- Lessons From Ceramic Petrography: A Case of Technological Transfer During the Transition From Late to Inca Periods in Northwestern Argentina, Southern Andes

- An Experimental and Methodological Approach of Plant Fibres in Dental Calculus: The Case Study of the Early Neolithic Site of Cova del Pasteral (Girona, Spain)

- Bridging the Post-Excavation Gaps: Structured Guidance and Training for Post-Excavation in Archaeology

- Everyone Has to Start Somewhere: Democratisation of Digital Documentation and Visualisation in 3D

- The Bedrock of Rock Art: The Significance of Quartz Arenite as a Canvas for Rock Art in Central Sweden

- The Origin, Development and Decline of Lengyel Culture Figurative Finds

- New “Balkan Fashion” Developing Through the Neolithization Process: The Ceramic Annulets of Amzabegovo and Svinjarička Čuka

- From a Medieval Town to the Modern Fortress of Rosas (Girona-Spain). Combining Geophysics and Archaeological Excavation to Understand the Evolution of a Strategic Coastal Settlement

- Technical Transfers Between Chert Knappers: Investigating Gunflint Manufacture in the Eastern Egyptian Desert (Wadi Sannur, Northern Galala, Egypt)

- Early Neolithic Pottery Production in the Maltese Islands: Initiating a Għar Dalam and Skorba Pottery Fabric Classification

- Revealing the Origins: An Interdisciplinary Study Into the Provenance of Sacral Microarchitecture–The Unique Case of the Church Model From Žatec in Bohemia

- An Analogical and Analytical Approach to the Burçevi Monumental Tomb

- A Glimpse at Raw Material Economy and Production of Chipped Stones at the Neolithic (Starčevo) Site of Svinjarička Čuka, South Serbia

- Archaeological Lithotheques of Siliceous Rocks in Spain: First Diagnosis of the Lithotheque Thematic Network

- Mapping Changes in Settlement Number and Demography in the South of Israel from the Hellenistic to the Early Islamic Period

- Review Article

- Structural Measures Against the Risks of Flash Floods in Patara and Consequent Considerations Regarding the Location of the Oracle Sanctuary of Apollo

- Commentary Article

- A Framework for Archaeological Involvement with Human Genetic Data for European Prehistory

- Special Issue on Digital Religioscapes: Current Methodologies and Novelties in the Analysis of Sacr(aliz)ed Spaces, edited by Anaïs Lamesa, Asuman Lätzer-Lasar - Part II

- Goats and Goddesses. Digital Approach to the Religioscapes of Atargatis and Allat

- Conceiving Elements of Divinity: The Use of the Semantic Web for the Definition of Material Religiosity in the Levant During the Second Millennium BCE

- Deep Mapping the Asklepieion of Pergamon: Charting the Path Through Challenges, Choices, and Solutions

- Special Issue on Engaging the Public, Heritage and Educators through Material Culture Research, edited by Katherine Anne Wilson, Christina Antenhofer, & Thomas Pickles

- Inventories as Keys to Exploring Castles as Cultural Heritage

- Hohensalzburg Digital: Engaging the Public via a Local Time Machine Project

- Monastic Estates in the Wachau Region: Nodes of Exchange in Past and Present Days

- “Meitheal Adhmadóireachta” Exploring and Communicating Prehistoric Irish Woodcraft Through Remaking and Shared Experience

- Community, Public Archaeology, and Co-construction of Knowledge Through the Educational Project of a Rural Mountain School

- Valuing Material Cultural Heritage: Engaging Audience(s) Through Development-Led Archaeological Research

- Engaging the Public Through Prehistory: Experiences From an Inclusive Perspective

- Material Culture, the Public, and the Extraordinary – “Unloved” Museums Objects as the Tool to Fascinate

- Archaeologists on Social Media and Its Benefits for the Profession. The Results and Lessons Learnt from a Questionnaire

- Special Issue on Network Perspectives in the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East and Eastern Mediterranean, edited by Maria Gabriella Micale, Helen Dawson, & Antti A. Lahelma

- Network Perspectives in the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East and Eastern Mediterranean

- Networks of Pots: The Usage of Ceramics in Network Analysis in Mediterranean Archaeology

- Networks of Knowledge, Materials, and Practice in the Neolithic Zagros

- Weak Ties on Old Roads: Inscribed Stopping-Places and Complex Networks in the Eastern Desert of Graeco-Roman Egypt

- Mediterranean Trade Networks and the Diffusion and Syncretism of Art and Architecture Styles at Delos

- People and Things on the Move: Tracking Paths With Social Network Analysis

- Networks and the City: A Network Perspective on Procopius De Aed. I and the Building of Late Antique Constantinople

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Etched in Stone: The Kevermes Stone Stela From the Great Hungarian Plain

- Waste Around Longhouses: Taphonomy on LBK Settlement in Hlízov

- Raw Materials and Technological Choices: Case Study of Neolithic Black Pottery From the Middle Yangtze River Valley of China

- Disentangling Technological Traditions: Comparative Analysis of Chaînes Opératoires of Painted Pre-Hispanic Ceramics From Nariño, Colombia

- Ancestral Connections: Re-Evaluating Concepts of Superimpositioning and Vandalism in Rock Art Studies

- Disability and Care in Late Medieval Lund, Sweden: An Analysis of Trauma and Intersecting Identities, Aided by Photogrammetric Digitization and Visualization

- Assessing the Development in Open Access Publishing in Archaeology: A Case Study From Norway

- Decorated Standing Stones – The Hagbards Galge Monument in Southwest Sweden

- Geophysical Prospection of the South-Western Quarter of the Hellenistic Capital Artaxata in the Ararat Plain (Lusarat, Ararat Province, Armenia): The South-West Quarter, City Walls and an Early Christian Church

- Lessons From Ceramic Petrography: A Case of Technological Transfer During the Transition From Late to Inca Periods in Northwestern Argentina, Southern Andes

- An Experimental and Methodological Approach of Plant Fibres in Dental Calculus: The Case Study of the Early Neolithic Site of Cova del Pasteral (Girona, Spain)

- Bridging the Post-Excavation Gaps: Structured Guidance and Training for Post-Excavation in Archaeology

- Everyone Has to Start Somewhere: Democratisation of Digital Documentation and Visualisation in 3D

- The Bedrock of Rock Art: The Significance of Quartz Arenite as a Canvas for Rock Art in Central Sweden

- The Origin, Development and Decline of Lengyel Culture Figurative Finds

- New “Balkan Fashion” Developing Through the Neolithization Process: The Ceramic Annulets of Amzabegovo and Svinjarička Čuka

- From a Medieval Town to the Modern Fortress of Rosas (Girona-Spain). Combining Geophysics and Archaeological Excavation to Understand the Evolution of a Strategic Coastal Settlement

- Technical Transfers Between Chert Knappers: Investigating Gunflint Manufacture in the Eastern Egyptian Desert (Wadi Sannur, Northern Galala, Egypt)

- Early Neolithic Pottery Production in the Maltese Islands: Initiating a Għar Dalam and Skorba Pottery Fabric Classification

- Revealing the Origins: An Interdisciplinary Study Into the Provenance of Sacral Microarchitecture–The Unique Case of the Church Model From Žatec in Bohemia

- An Analogical and Analytical Approach to the Burçevi Monumental Tomb

- A Glimpse at Raw Material Economy and Production of Chipped Stones at the Neolithic (Starčevo) Site of Svinjarička Čuka, South Serbia

- Archaeological Lithotheques of Siliceous Rocks in Spain: First Diagnosis of the Lithotheque Thematic Network

- Mapping Changes in Settlement Number and Demography in the South of Israel from the Hellenistic to the Early Islamic Period

- Review Article

- Structural Measures Against the Risks of Flash Floods in Patara and Consequent Considerations Regarding the Location of the Oracle Sanctuary of Apollo

- Commentary Article

- A Framework for Archaeological Involvement with Human Genetic Data for European Prehistory

- Special Issue on Digital Religioscapes: Current Methodologies and Novelties in the Analysis of Sacr(aliz)ed Spaces, edited by Anaïs Lamesa, Asuman Lätzer-Lasar - Part II

- Goats and Goddesses. Digital Approach to the Religioscapes of Atargatis and Allat

- Conceiving Elements of Divinity: The Use of the Semantic Web for the Definition of Material Religiosity in the Levant During the Second Millennium BCE

- Deep Mapping the Asklepieion of Pergamon: Charting the Path Through Challenges, Choices, and Solutions

- Special Issue on Engaging the Public, Heritage and Educators through Material Culture Research, edited by Katherine Anne Wilson, Christina Antenhofer, & Thomas Pickles

- Inventories as Keys to Exploring Castles as Cultural Heritage

- Hohensalzburg Digital: Engaging the Public via a Local Time Machine Project

- Monastic Estates in the Wachau Region: Nodes of Exchange in Past and Present Days

- “Meitheal Adhmadóireachta” Exploring and Communicating Prehistoric Irish Woodcraft Through Remaking and Shared Experience

- Community, Public Archaeology, and Co-construction of Knowledge Through the Educational Project of a Rural Mountain School

- Valuing Material Cultural Heritage: Engaging Audience(s) Through Development-Led Archaeological Research

- Engaging the Public Through Prehistory: Experiences From an Inclusive Perspective

- Material Culture, the Public, and the Extraordinary – “Unloved” Museums Objects as the Tool to Fascinate

- Archaeologists on Social Media and Its Benefits for the Profession. The Results and Lessons Learnt from a Questionnaire

- Special Issue on Network Perspectives in the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East and Eastern Mediterranean, edited by Maria Gabriella Micale, Helen Dawson, & Antti A. Lahelma

- Network Perspectives in the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East and Eastern Mediterranean

- Networks of Pots: The Usage of Ceramics in Network Analysis in Mediterranean Archaeology

- Networks of Knowledge, Materials, and Practice in the Neolithic Zagros

- Weak Ties on Old Roads: Inscribed Stopping-Places and Complex Networks in the Eastern Desert of Graeco-Roman Egypt

- Mediterranean Trade Networks and the Diffusion and Syncretism of Art and Architecture Styles at Delos

- People and Things on the Move: Tracking Paths With Social Network Analysis

- Networks and the City: A Network Perspective on Procopius De Aed. I and the Building of Late Antique Constantinople