Disentangling Technological Traditions: Comparative Analysis of Chaînes Opératoires of Painted Pre-Hispanic Ceramics From Nariño, Colombia

-

Catherine Klesner

, Rosie Crawford

, María Camila Maya Cabrera

Abstract

Occurring throughout the Americas, ceramics with negative decoration have been variously used as archaeological markers of chronology, provenance, ethnic affiliation, or cultural interaction. In the highlands of the adjacent regions of Nariño (Colombia) and Carchi (Ecuador), they are recovered and discussed frequently, but the lack of technical studies has prevented any conclusive inferences about their technology, craft organisation, or diachronic evolution. Here we present the first comparative analysis of the chaînes opératoires of three ceramic wares – Capulí, Piartal, and Tuza – based on a large sample from multiple sites. Combining geometric morphometrics, bulk chemistry, microscopy, and microanalysis, we provide high-resolution characterisation of each ware before comparing their chaînes opératoires. We demonstrate that Capulí and Piartal share decorative features and production pathways, which we interpret as indicating the direct knowledge transmission and interaction between their makers. Similarity in vessel morphology and clay sources between Piartal and Tuza ceramics suggests continuity between these two technological traditions, but new decorative techniques and designs in Tuza vessels are strongly indicative of exogenous influences. This study has implications for regional archaeology but also offers a model for the nuanced comparison of ceramic traditions in other areas (for an extended summary in Spanish, see Supplementary Material).

1 Introduction

The high rate of occurrence of intricate, negative painted pottery in South and Central America has been noted for almost a century, and indeed was the focus of early stylistic analysis (Stigler, 1954). Negative decoration in the Americas was chiefly achieved through so-called “resist painting,” where the design was first painted with a temporary protective material such as wax, after which the ceramic was covered all over with a material imparting a dark colour, and subsequently the protective material was removed to expose the underlying figures in a light colour against a dark background. Resist painting is a complex, multi-step method, but it is the easiest way to achieve certain negative patterns, including those where the light decoration includes circles and dots (Shepard, 1954), and its occurrence points to the ingenuity of early potters. While stylistic and petrographic analyses of these wares have been the focus of many studies, technological analysis of how these decorations were achieved has been rather sparse (Baumann et al., 2013; Shepard, 1954) and today we still have little understanding of how these bi-chrome and polychrome resist-painted negative decorations were realised by potters across Central and South America.

Prime examples of resist-painted ceramics are found in Nariño (Colombia), where three overlapping styles of highly decorated ceramics were produced in the Serranía nariñense (also known as the altiplano) region during the pre-Hispanic period. The three decorative styles, originally discussed by Grijalva (1937) and Jijón y Caamaño (1952) and redefined by Francisco (1969) for the neighbouring region of Carchi (Ecuador), were adopted by Uribe (1977–1978) in her analysis of pottery from Ipiales, Nariño. These styles, hereafter referred to as wares as their definition considers technological attributes associated with surface decorative elements (Rice, 1976), can be succinctly defined as consisting of only negative resist-painted decoration (Capulí), combining a mixture of negative and positive techniques (Piartal), or only utilising positive painting (Tuza) (Figure 1).

Examples of bowls with a pedestal foot with Capulí (left – CA230359), Piartal (middle – CA230361), and Tuza (right – CA230353) style decoration. Vessel shapes are representative of each ware. Images not to scale.

All three wares comprise a wide range of vessel forms, including jars (globular and lenticular), tripod pots, moccasin vessels, and bowls with and without bases. Some shapes and ceramic objects are distinct to certain wares, including anthropomorphic figurines (coqueros) and zoomorphic vessels which are only found in Capulí ceramics, while amphoras, “composite” pots with a ring base, shallow square pedestalled bowls, and ocarinas are only present in Piartal and Tuza wares (Uribe, 1977–1978).

The wares are broadly distributed across the Serranía nariñense region, with material displaying characteristics of these wares ranging from Quito, Ecuador in the south to La Cruz in northern reaches of the Nariño department (Lleras Pérez et al., 2007). While all three wares are commonly found in burials, Tuza ceramics are additionally recovered from middens and domestic sites.

1.1 Ware Relations

How these three ceramic wares relate to one another chronologically and geographically, and how the producers and consumers of these wares relate to one another culturally, has been questioned since they were first identified by Francisco. She placed them in a single developmental sequence with Capulí representing the oldest ceramic style, followed by Piartal, and then Tuza. Although Francisco had no radiocarbon dates to plant this sequence in time, she identified this progression due to the occurrence of several features in addition to gradual morphological changes in the vessel shapes (Francisco, 1969).

Tuza was placed as the final progression in the sequence for two reasons. First, the occurrence of an unusual example of “Tuza” style ceramic with a black slip thought to be an imitation of llamita designs brought by the Incas places the ware as still being produced in the late fifteenth century onwards. Second, the site of San Gabriel (the type site of Tuza) had copious surface fragments and rich middens which composed of Tuza ceramics, which led Francisco to claim “unless one wishes to take the position that the ceramics were made by the Spaniards themselves, it is difficult to avoid the conclusion that they represent the last of the styles of the original inhabitants of Carchi” (Francisco, 1969, p. 104).

Piartal was placed in the period immediately before Tuza based on two main observations. First, there appears to be shared material culture associated with both Piartal and Tuza burials, including ceramic shell-form whistles (ocarina), as well as a shared settlement form (bohíos). These features were not observed to be associated with Capulí material. Second, Francisco (1969) excavated a large tomb at the site of OCr2-13, which recovered ceramic vessels with both Piartal and Tuza decorative features, and this was considered to represent a period of transition between the two styles. The tomb contained eight clay whistles, Piartal vessels (including those with negative decoration), Tuza vessels, two sets of copper rings (possibly earrings), marine conch shells, and sedge seed beads. The co-occurrence of Piartal and Tuza vessels has also been identified in two tombs excavated by Cárdenas Arroyo (2020, 1992) at the site of Maridíaz in Pasto. Unfortunately, none of these three transition tombs have been radiocarbon dated. Capulí was placed as the oldest ware in the sequence, as it could not fit between the Piartal and Tuza styles given their shared features.

While Uribe (1977–1978) largely agreed with Francisco’s ware types in her analysis of materials from Ipiales, Nariño, she disagreed with the relative dating of the wares. Like Francisco, Uribe identified a continuous cultural tradition between the Piartal and Tuza wares due to their relationship to bohíos settlements, emphasis on interior decoration of footed bowls, occurrence of clay snail whistles (ocarinas), and presence of painted zoomorphic features on pottery. However, based on radiocarbon dates from sites in Nariño in the 1970s, Uribe (1977–1978) did not agree with placing the production of Capulí vessels in the period before Piartal, and instead proposed that there were two distinct cultural groups occupying the same geographic area contemporaneously. One group produced Capulí ceramics, and shared relationships with groups on the Pacific coast, while the second group produced Piartal and then Tuza ceramics, with the transition between Piartal and Tuza ceramics occurring about 1250 CE.

The past 40 years of archaeological research in the Serranía nariñense have largely favoured Uribe’s chronological model, with new contributions including the work of Bernal Vélez (2011, 2020), Cadavid Camargo and Ordoñez (1992), Cárdenas Arroyo (1992, 1995, 2020), Cavelier et al. (2019), Groot de Mahecha and Hooykaas (1991), Langebaek Rueda and Piazzini Suarez (2003), Lleras Pérez et al. (2007), Patiño (1994), Uribe (1983) and Uribe and Lleras P. (1982) refining, and occasionally challenging, this narrative. Much of this research has focused on the question of whether these ceramic wares can be associated with specific ethnic groups, such as the Pastos and the Quillacingas, which were identified as residing in the Serranía nariñense in Spanish historical accounts from the sixteenth and seventeenth century CE. While much more is known about the archaeology of Nariño today, the continued lack of excavated domestic sites with long occupational periods or features associated with craft production still presents challenges for the creation of a definitive ceramic chronology, an understanding of craft organisation, and present challenges in researchers’ understanding of the society of the pre-Hispanic Nariñenses.

1.2 Thesis/Objective

Our research is based on the premise that a focus on technology can be more effective in understanding the temporal, geographical, and cultural relationships among the producers and consumers of these ceramic objects. Further, we make no a priori assumptions about the ethnic affiliations of pottery makers and users, or about potential links between luxury goods and extractive political elites. We reconstruct key stages of the chaînes opératoires of Capulí, Piartal, and Tuza ceramic vessels to better recognise how these ceramic wares relate to one another and other complex crafts. By focusing on a common vessel form, bowls with a pedestal foot, and systematically comparing the raw materials procurement, forming, and decorative stages across these wares, we can begin to form a broader understanding of craft organisation within the heterarchical societies of pre-Hispanic Colombia.

In our contribution to disentangling the ceramic traditions of Nariño, we also hope to provide a reference for other studies. While archaeological ceramic traditions are often compared in terms of shape, composition, or technology, this study demonstrates that a holistic, fine-grained comparison of ceramic wares can enable more nuanced discussions of long-term trajectories of technological evolution and knowledge transmission.

2 Materials

A total of 184 total samples were analysed for this study, half of which (n = 92) were complete or near-complete vessels, and the remaining (n = 92) samples consist of fragmentary material. All of these are registered with the Colombian Institute of Anthropology and History (ICANH) and hence legal and ethically acceptable.[1] The sample consists of artefacts from recently excavated sites in Nariño described below (Figure 2 and Table 1), as well as material in the Museo del Oro in Bogotá and the Hacienda San Antonio de Bomboná pottery collection (hereafter Bomboná collection, ICANH registration no. 1202). The sampling strategy explicitly aimed to cover a variety of wares, prioritising excavated sites as much as possible, including fragmentary material available for invasive analyses, and supplementing material from collections where needed.

Map of the Nariño highlands with the location of the sites mentioned in the text indicated. Map drawn by Jasmine Vieri in QGIS v. 3.4.4 (QGIS Development Team, 2022) with the projection Magna-Sirgas EPSG 4686. Hillshade based on 1 Arc-Second STRM data produced by NASA, with the water bodies taken from Instituto Geográfico Agustín Codazzi (IGAC, 2022).

Summary of the samples in this study

| Collection/site | Prov.? | Site | Capulí | Piartal | Tuza | Tuza – Red slip | Undec. | Others | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Museo del Oro | No | Many | 5 | 12 | 16 | 1 | 34 | ||

| El Porvenir, Iles | Yes | Site 137 | 48 | 48 | |||||

| Catambuco, Pasto | Yes | San Damián | 16 | 10 | 14 | 17 | 57 | ||

| Site 8 | 13 | 13 | |||||||

| Obonuco, Pasto | Yes | CIAO21 | 5 | 5 | |||||

| Bomboná collection | No | Many | 2 | 2 | 11 | 2 | 8 | 2 | 27 |

| Total | 55 | 48 | 37 | 16 | 25 | 3 | 184 | ||

Prov.? = provenanced; Undec. = Undecorated.

2.1 El Porvenir, Iles

At El Porvenir, in the municipality of Iles, two sites were identified (Site 136 and Site 137) and excavated in 2019–2020 as part of the preventive archaeological interventions carried out within the Rumichaca-Pasto Road Project (ICANH registration no. 7610). The sites, which sit at an altitude of 1,887 m above sea level, occupy two adjacent alluvial–colluvial terraces and consist of two cemeteries. During the limited excavations associated with the construction of the road, a total of 56 tombs with at least 67 burials were recovered. The decorated ceramic material from both cemeteries aligns with the Capulí ware, and the radiocarbon dating indicates that Sites 136 and 137 date from the fifth–sixth and fourth–fifth century CE, respectively (Mendoza Acosta & Marín, 2023). There was no evidence of contexts altered by looting or high agricultural activity in the excavated areas, resulting in remarkably well-preserved burials. Only material from Site 137 was included in this research, as a recent landslide on the terrace resulted in a mixture of full vessels and fragmentary material ideal for multi-method analysis. In addition to ceramic vessels, burials in Site 137 also contained lithics, metalwork, a pyrite mirror, and male (coquero) and female (coquera) anthropomorphic ceramic figurines, including one exceptional example of a female nursing a child.

2.2 Catambuco, Pasto

Materials from two excavations in the municipality of Catambuco, located approximately 4 km south of Pasto, were included in this research.

Site 8 was excavated by Ana Sofia Caicedo (in 2018) and Carlos Cardona (in 2019) as part of the preventive archaeology study (ICANH registration nos 6615 and 7610) of the Rumichaca-Pasto Road Project. The site is located at 2,859 m.a.s.l., and sits above a system of hills on a colluvial terrace, with an area of approximately 470 m2. A total of eight funerary contexts were recovered, of which five were affected by looting (guaquería), while three remained intact. Archaeological evidence suggests that the site was primarily associated with Piartal pottery (refer ICANH final reports 7610 and 8030).

Adjacent and immediately below Site 8 is the site of San Damián, which was excavated by Marcela Bernal Arévalo and Lucero Aristizábal Losada as part of a preventive archaeology study (ICANH permit nos 7774 and 8066) for the CESMAG University Institution project. The study area is a large plateau (78,434 m2), which includes domestic, funerary, and ceremonial contexts. Archaeological evidence suggests that the site was primarily associated with Tuza ceramic material, and is related to a late pre-Hispanic occupation. In addition to structures associated with domestic contexts, a large rectangular structure, which could represent a ceremonial centre or multi-family residence, was identified, as well as 120 funerary structures, consisting of simple graves, pit graves, and shaft graves with lateral chambers. In addition to the standard Tuza wares a large number of the decorated sherds selected from the San Damián collection had simple, thick red slips applied to the interior of open shapes (identified as bowls) which extended almost to the edge of the rim, leaving a pale border on the rim showing the underlying pale slip/fabric. This style was also identified as common in middens associated with Tuza sites by Francisco (1969) and were separated into the subgroup “Tuza – Red slip” in this study. In this study, “Tuza” includes the “Tuza – Red slip” group unless otherwise noted. Sampling from the site of San Damián was aimed to complete our coverage of wares, but cannot be deemed fully representative of the site, given the over 130,000 fragments recovered as part of the survey and excavation.

2.3 Obonuco, Pasto

The site of CIAO21 is located on the land of the AGROSAVIA Research Centre in the Obonuco district, municipality of Pasto, Nariño, on a colluvial terrace on the slopes of the Galeras volcano. A single tomb was discovered during the development of agricultural activities associated with the Research Centre, and it was addressed by ICANH and excavated in 2021 as part of the implementation of the “Protocol for the Management of Chance Finds of Archaeological Heritage,” adopted by ICANH through Resolution 797 on October 6, 2020. The access shaft of the tomb was 90 cm deep with a lateral chamber 150 cm deep containing 14 individuals (9 adults and 5 infants) along with 59 complete or near complete ceramic vessels, lithic artefacts, an ocarina, textile fragments, necklace beads, and a sample of ochre pigment. Radiocarbon dating of two individuals in the tomb suggest that it was used for a short period of time in the eleventh–twelfth century CE (MAMS-6587 – 936 ± 15 BP and MAMS-6598 – 897 ± 15 BP, reported in Maya Cabrera, 2024, p. 119), and the ceramic material from this tomb is exclusively associated with the Piartal style.

3 Methods

3.1 2D Outline-Based Geometric Morphometrics (GMM) From 3D Mesh

A total of 87 complete or near complete open vessels were documented using an Artec Space Spider handheld structured light scanner to collect 3D data on the vessel morphology. The Artec Space Spider captures the 3D data at a resolution of up to 0.1 mm and a point accuracy of up to 0.05 mm using blue-light based technology. At least three independent scans were needed to capture the full vessel shape. Merging and post processing of the scans was achieved using Artec Studio 16 (Artec 3D) and the 3D models are accessible on sketchfab (Supplementary Material).

The 3D models were then aligned, and a random complete cross-section of each vessel was extracted using the opensource software GigaMesh (Bayer, 2018, Mara et al., 2010). The extracted sections were then processed using Adobe Illustrator to turn them into a solid black object against a solid white background to allow for the cross section to be traced (Loftus, 2022). The opensource software tpsDIG264 was then used to turn each outline into tanged points. Tanged points were subsequently loaded into the MOMOCS package (Bonhomme et al., 2014) in RStudio for all further quantitative analyses, including Elliptical Fourier Analysis (EFA) outline extraction, relying on 30 harmonics; principal component analysis for ordination and dimension reduction; and multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) for group-based significance testing. While the first 8 harmonics account for 99% of the variation in the dataset, with 16 harmonics accounting for 99.9% of variation, EFA shapes produced using a larger number of harmonics were investigated, given our interest in minor variations. Thirty harmonics were identified visually as sufficient to capture the full detail of the shape, while not capturing post-production variation such as small damage present in the cross section. All GMM visualisations and graphs were prepared in R v. 4.3.1 (R Core Team, 2023) using RStudio v. 2023.06.1.524 (Posit team, 2023).

3.2 Compositional Analysis

A total of 145 samples were analysed by portable X-ray fluorescence (pXRF) spectrometers to assess the ceramic fabric composition and nature of the surface decoration when present. This set includes both complete vessels and ceramic fragments. Complete vessels were analysed in Colombia while fragments were analysed in the United Kingdom.

The analyses were carried out using one of the Pitt-Rivers Laboratory Olympus Vanta M series pXRF spectrometers, equipped with an Rh anode and a silicon drift detector, operating at two energies (40 kV with ∼70 μA for 60 s, and 10 kV with ∼90 µA for 30 s), with a 3 mm collimator in place. Quantification was supported by the in-house calibration “BRICCcol,” which is based on the factory-built Geochem fundamental parameters algorithm, but optimised for ceramic materials through empirical calibration with the BRICC calibration set (Frahm et al., 2022).

Five measurements on unique locations were taken for the ceramic fabric and reference materials, while three unique measurements were taken for each surface feature under investigation. On fragmentary material, fabric measurements were taken from the cross-sections, while on whole vessels, fabric measurements were taken on the unslipped bottom of the foot to avoid any slips or other surface features. Data quality during ceramic analyses was assessed by repeated measurements of three independent certified reference materials (CRMs), NIST 2711a, NIST 679, and SARM 69, which were measured as homogenised powders (Supplementary Material).

While the Geochem method generates data for 36 elements, the BRICCcol in-house calibration allows for quantification of the following elements: Al, K, Ca, Ti, Mn, Fe, Zn, Rb, Y, Zr, Nb, and Pb, as calibration curves with R 2 > 0.9 were obtained for repeated measurements on the BRICC calibration set and an average % error based on the three external CRMs measured was consistently <10%. An additional four elements are considered in the BRICCcol calibration but were not included in ceramic group identification, because their calculated % error based on the three external CRMs fell between 10 and 20% (Si, Ni, and Sr). Mg was also excluded from this analysis as it displayed a large error associated with the extreme low (5 m.a.s.l) and high (>2,500 m.a.s.l) altitudes of collection (Supplementary Materials) which resulted in a differing transmission of low-energy X-rays in the respective differing atmospheric pressures (Merrill et al., 2018).

The three CRMs were regularly measured throughout the research in both Colombia and in the United Kingdom to check the long-term stability of the pXRF. The reproducibility, represented by % error calculations of the measured values, was very good and the average is <8% for most of the elements throughout the research. The reproducibility of Ca, ranged up to 13%, which is poorer than other elements but was still considered for group identification.

3.3 Raman Spectroscopy

Twelve samples were examined by Raman spectroscopy to investigate the nature of their surface decoration in more detail.

Raman point spectra data were produced on the surface of the ceramic fragments using a Renishaw InVia Raman microscope fitted with a 50× dry objective and a 785 nm laser. Point spectra were generated after 10 s exposure time, 1–3 accumulations, laser power of 0.5–5%, and spectra were collected from 100 to 1,800 cm−1 with the pinhole engaged. Data were compared to spectra in the RRUFF database (Lafuente et al., 2016) and previously published data from archaeological pigments and coatings (Caggiani et al., 2016; Łaciak et al., 2019).

3.4 Scanning Electron Microscopy With Energy Dispersive Spectroscopy (SEM-EDS)

Following compositional analysis, 12 samples were sectioned, embedded in epoxy resin blocks, ground, and polished down to 1 μm for SEM-EDS examination. Analysis was conducted on a Zeiss Evo25 SEM with an Oxford Instruments Ultim Max EDS with an energy resolution of less than 127 eV (at Mn Kα). Compositional data were acquired under the following conditions: working distance: 8.5 mm, accelerating voltage: 20 kV, acquisition normalised to 600,000 counts, calibrated with a cobalt standard. Backscattered electron imaging (BSE) was used to differentiate decorative elements on the sample surface, inclusions in the ceramic fabric, and to assess the overall microstructure. Compositional data of the ceramic fabric and slips were obtained through multiple small EDS area scans avoiding large inclusions, with an average of seven scans for the fabrics and four for the slips. In order to verify the reliability of the chemical data, the Basalt standard BIR-1g was analysed alongside the sample (Supplementary Material). Results are reported as stoichiometric oxides and have been normalised to 100% after assessment of data quality.

4 Results

4.1 Morphology

A total of 87 vessels, each/all of which can be broadly defined as a bowl with a pedestal foot, were assessed by GMM methods. This shape, which has been variably referred to by different authors for different wares as copa, compotera, cuenco con soporte, and cuenco con base anular, was chosen for morphological analysis as its general shape is present in all three ceramic styles and it is the most common vessel shape included in burial contexts in the region. A total of 85 vessels were included in the results, as one vessel (CA230380) was an exceptional Capulí style copa with an extremely tall pedestal, and another Capulí vessel (CA230384) had an encased pedestal which contained a rattle, both of which behaved as outliers in the dataset.

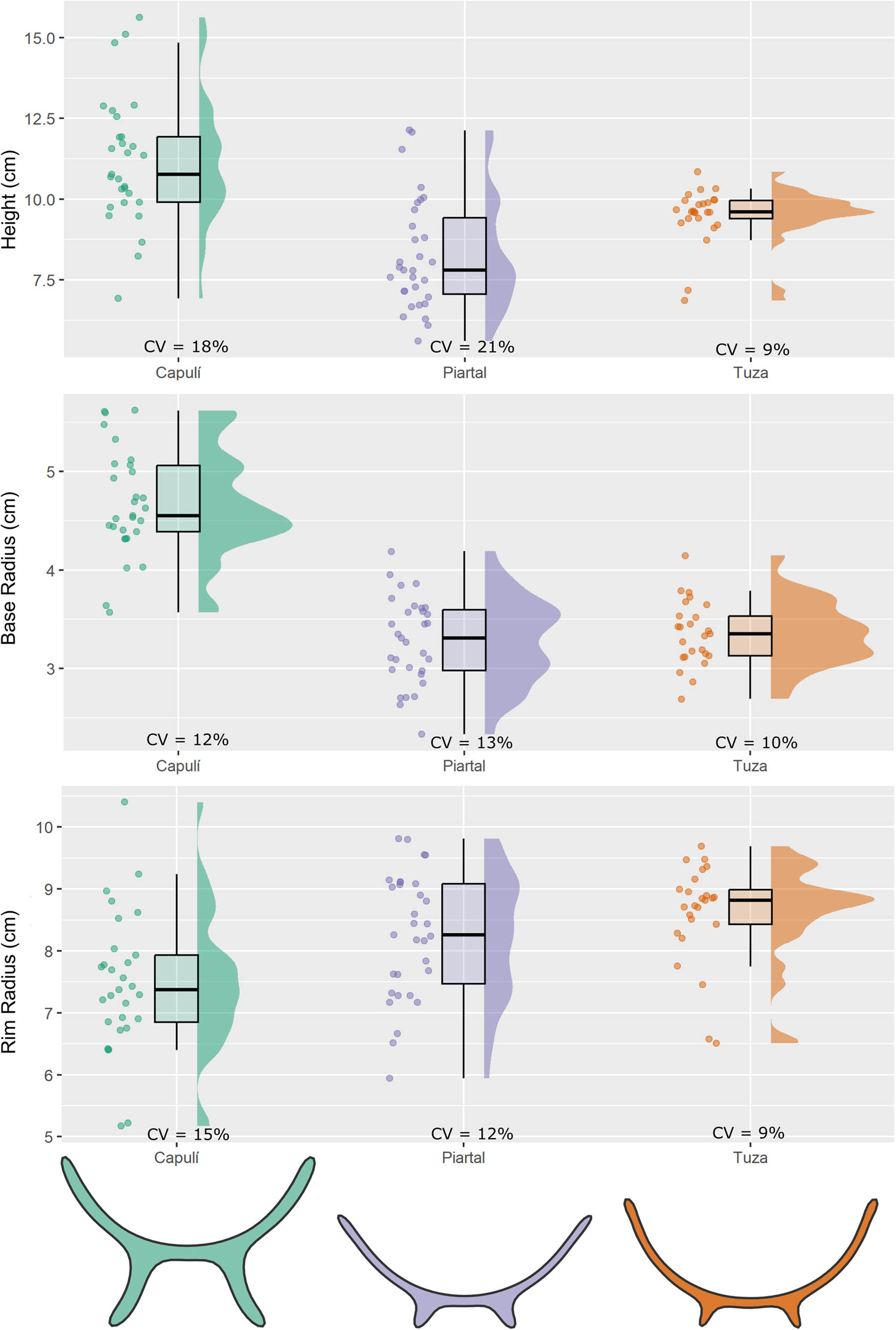

The vessels were hand built, and show evidence of coil construction including subtle, regular variations in wall thickness (Groot de Mahecha & Hooykaas, 1991; Rye, 1981; Uribe, 1977–1978). The bowls and pedestals were made separately, and later joined. Occasionally, the pedestal was joined slightly off-centre compared to the bowl; this is most apparent in the Capulí vessels. It is common for the vessels to break at the join between the bowl and the base (Uribe, 1977–1978). Some of the Tuza vessels display evidence which suggests wheel-turning on the bases, especially those with the all-over interior Red Slip, identifiable through the presence of very fine continuous horizontal groves and lines on the unslipped surface (Rye, 1981). The bowls range in size both within wares and between wares (Table 2 and Figure 3). Across all samples, they have an average height of 9.6 cm, a rim diameter of 16 cm, a base diameter of 7.5 cm, and the bowl has an average capacity of 0.7 L.

Average (μ), standard deviation (σ), and coefficient of variation (CV) of the vessel height, base radius, and rim radius of the bowls with a pedestal foot by ware type

| Ware | Stats | Height (cm) | Rim radius (cm) | Base radius (cm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Capulí (n = 29) | μ | 11.16 | 7.47 | 4.68 |

| σ | 1.97 | 1.12 | 0.54 | |

| CV | 18% | 15% | 12% | |

| Piartal (n = 31) | μ | 8.25 | 8.24 | 3.28 |

| σ | 1.74 | 1.01 | 0.44 | |

| CV | 21% | 12% | 13% | |

| Tuza (n = 25) | μ | 9.50 | 8.60 | 3.35 |

| σ | 0.87 | 0.81 | 0.33 | |

| CV | 9% | 9% | 10% |

Distribution of the vessel height, base radius, and rim radius with their respective CVs by ware type. Mean shapes for each ware are shown, calculated using the “MSHAPES” function in MOMOCs.

Variations in the morphology were assessed by examining principal components (PCs), which is a reliable method for outline-based GMM to reduce and capture major points of morphological importance (Loftus, 2022). Three PCs account for 94% of variance within the PC space and are considered significant for distinguishing ware morphology, with PC1 accounting for most of that variance (84.8%) in the dataset. Each PC correlates with different morphological features, which can be visualised in Figure 4. PC1 captures the variation in the height of the base, which has previously been noted by researchers in Nariño and Carchi as an important morphological difference between Capulí and Piartal/Tuza wares (Figure 4). Both PC2 and PC3 capture variation in the base thickness, width, and angle of attachment, and PC 3 additionally captures variation in the open and curved nature of the walls of the bowl.

Summary of shape variation along PC axes for PCs that account for >90% of variation in the dataset (PC 1–3), utilising the “PCcontrib” function in MOMOCs. Arrows added to indicate direction of shape variation across each PC.

The results of the PCA clearly indicate that Capulí vessels have a distinct morphology compared to Piartal and Tuza vessels, and almost all Capulí vessels (96% of samples) have a positive PC1 score resulting primarily from their tall, pedestalled base (Figure 5). Piartal and Tuza have more similar morphological features, with Tuza vessels having a more constrained form compared to Piartal vessels, in relation to PC2 (Figure 5) and PC3 (Supplementary Material). To test the statistical significance in the observed difference between wares, a pairwise MANOVA, utilising Pillai’s trace was applied to the PC scores accounting for 99% of the total variance in the dataset (Table 3). The results indicate that the vessels from the three wares are morphologically significantly different (p < 0.000) at alpha level 0.05.

Biplot of PC1 vs PC2 of all 85 vessels with (above) overlaid morphology of each sample displayed, and (below) samples distinguished by ware type with 90% confidence ellipses overlaid.

Results of pairwise MANOVA comparing the three wares utilising the first 11 PCs which accounts for 99% of variance

| Df | Pillai | Approx. F | Num Df | Den Df | Pr(>F) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Capulí – Piartal | 1 | 0.9164 | 47.83 | 11 | 48 | <0.000 |

| Capulí – Tuza | 1 | 0.9374 | 57.16 | 11 | 42 | <0.000 |

| Piartal – Tuza | 1 | 0.7742 | 13.72 | 11 | 44 | <0.000 |

To assess the level of morphological standardisation within wares, PC scores were examined (Table 4 and Figure 6). Tuza vessels have the narrowest range of scores for PC1 and PC2, which together account for >90% of the variation. Capulí vessels have the highest range of PC scores for the same components, and display the greatest amount of morphological variation among the three wares. As seen in PC2 (Figures 5 and 6), there is a group of six Capulí vessels with exceptionally high scores. These comprise all of the vessels without negative decoration (CA230372, CA230375, and CA230383) as well as two decorated vessels from Site 137 (CA230374 and CA230376) and one vessel from the Bomboná collection (CA230405). All of these vessels have a very wide and flared pedestalled base, and this group contains three of the four examples sampled which have a thin incised line below the rim accompanied by vertical grooves between the line and the edge of the rim.

Distribution of scores for PC1–3 for each ware, including the full range of PC scores and the range removing outliers (values falling outside 1.5 times the Interquartile range)

| PC1 | PC2 | PC3 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % Variance explained | 84.83% | 5.23% | 4.35% | ||

| Capulí | n = 29 | Full range | 0.657 | 0.302 | 0.113 |

| Range removing outliers | 0.320 | 0.302 | 0.113 | ||

| Standard deviation | 0.13 | 0.09 | 0.03 | ||

| Piartal | n = 31 | Full range | 0.235 | 0.160 | 0.343 |

| Range removing outliers | 0.235 | 0.160 | 0.261 | ||

| Standard deviation | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.07 | ||

| Tuza | n = 25 | Full range | 0.242 | 0.244 | 0.491 |

| Range removing outliers | 0.129 | 0.063 | 0.141 | ||

| Standard deviation | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.03 | ||

PC1–3 score distribution by ware.

Piartal vessels have intermediate ranges of scores in PC1 and PC2, and show the most variation in PC3, which was the component that primarily captured morphological variation in the bowl shape as opposed to the pedestalled base. Interestingly, Piartal vessels have a bimodal distribution in PC1 and PC2 (Figure 6), suggesting that there are two different forms produced within the Piartal style decoration. To investigate this, the two distributions of Piartal samples were further separated into Piartal-1, with normalised PC1 scores above −0.2 (n = 20), and Piartal-2, with scores below −0.2 (n = 11). Piartal-1 has more open shape with gently sloping walls and a taller and wider pedestalled base, while Piartal-2 has a deeper bowl shape similar in many respects to Tuza vessels (Figure 7), but with thicker base walls and less defined “ring base” structure.

Comparison of mean shapes of Capulí, Piartal (Groups 1 and 2), and Tuza vessels calculated from EFA outlines utilising the “MSHAPES” function in MOMOCS.

All of the vessels recovered from the Obonuco tomb and the San Damian excavation at Catambuco fall into the Piartal-1 group. Additionally, the majority of the vessels (87.5%) from Site 8 at Catambuco also fall into this Piartal-1 group, as do five vessels from the collections. The Piartal-2 group, on the other hand, is predominantly composed of vessels from the collections, with only a single example (CA230357) originating from the Site 8 excavation at Catambuco. This morphological distribution suggests that there may be a local Piartal vessel style (Piartal-1) which was produced and consumed in the southern Atriz valley.

4.2 Fabric Composition

Compositional data for 145 samples was obtained by pXRF. Of those, two samples from collections were identified as likely not having a pre-Hispanic origin given their fabric composition and stylistic features, and were excluded from further analysis. In particular, CA230346 had anomalously high levels of Ca (29.09 wt% CaO), Zn (1,164 ppm), and Pb (848 ppm), which was over 40 times higher than the average of other samples (19 ppm). CA230351, which is a unique ceramic mask, had significantly higher concentrations of SiO2 and Ti, and low levels of Fe and Rb compared to other samples. An additional two (CA230298_1 and CA230298_2) were identified as likely produced outside of the Serranía nariñense region given their surface decoration method (stamping similar to one produced in the Amazon region) and their fabric chemistry (elevated concentrations of Fe, Rb, Y, and low levels of Sr) and were excluded from the dataset. The composition of the remaining 141 ceramic fabrics is fairly consistent with 17.58 ± 2.32 wt% Al2O3 and 1.30 ± 0.38 wt% K2O (Table 5). They are made from a low to noncalcareous clay, with average 1.89 ± 0.38 wt% CaO. The most variation in the major elements comes from the amount of iron present in the ceramic fabrics (Figure 8), which ranges from 1.77 to 8.19 wt% Fe2O3, with an average of 4.33 ± 1.38 wt% Fe2O3.

Summary statistics for the composition of ceramic fabric (reported in ppm for elements and wt% for oxides) generated by pXRF for all samples, and for the samples grouped by decorative style

| MgO | Al2O3 | SiO2 | K2O | CaO | Fe2O3 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All samples | m | 1.80 | 17.58 | 56.74 | 1.30 | 1.89 | 4.33 |

| n = 141 | σ | 0.12 | 2.32 | 5.68 | 0.38 | 0.38 | 1.38 |

| Capulí | m | 1.88 | 17.10 | 54.12 | 1.27 | 1.92 | 5.51 |

| n = 51 | σ | 0.12 | 2.18 | 4.12 | 0.38 | 0.43 | 0.71 |

| Piartal | m | 1.72 | 17.68 | 56.09 | 1.23 | 1.74 | 3.42 |

| n = 34 | σ | 0.10 | 2.43 | 6.96 | 0.44 | 0.39 | 1.00 |

| Tuza (incl. red slip) | m | 1.70 | 17.38 | 60.43 | 1.44 | 1.95 | 3.14 |

| n = 31 | σ | 0.04 | 2.60 | 4.95 | 0.36 | 0.27 | 0.78 |

| Undecorated | m | 1.74 | 18.70 | 58.41 | 1.26 | 1.96 | 4.61 |

| n = 25 | σ | 0.06 | 1.74 | 4.50 | 0.29 | 0.34 | 1.38 |

| Ti | Mn | Ni | Zn | Rb | Sr | Y | Zr | Nb | Pb | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All samples | m | 4,579 | 670 | 25 | 60 | 52 | 557 | 10 | 190 | 15 | 19 |

| n = 141 | σ | 611 | 760 | 10 | 20 | 9 | 119 | 4 | 30 | 3 | 4 |

| Capulí | m | 4,458 | 1,069 | 28 | 65 | 53 | 571 | 11 | 206 | 14 | 19 |

| n = 51 | σ | 478 | 1,082 | 12 | 20 | 8 | 137 | 4 | 32 | 3 | 3 |

| Piartal | m | 4,623 | 410 | 24 | 49 | 45 | 504 | 10 | 179 | 14 | 20 |

| n = 34 | σ | 619 | 239 | 7 | 16 | 7 | 81 | 4 | 23 | 3 | 6 |

| Tuza (incl. red slip) | m | 4,588 | 394 | 21 | 54 | 52 | 615 | 9 | 183 | 16 | 19 |

| n = 31 | σ | 730 | 189 | 7 | 16 | 6 | 113 | 3 | 24 | 3 | 2 |

| Undecorated | m | 4,751 | 553 | 21 | 73 | 59 | 531 | 12 | 180 | 14 | 18 |

| n = 25 | σ | 661 | 515 | 8 | 21 | 11 | 98 | 4 | 25 | 3 | 3 |

Note: Italics indicate elements measured but not included in ceramic group identification.

A scatterplot of Fe2O3 vs CaO concentrations (in wt%) for the ceramics considered in the dataset. Confidence ellipses indicate 90% confidence.

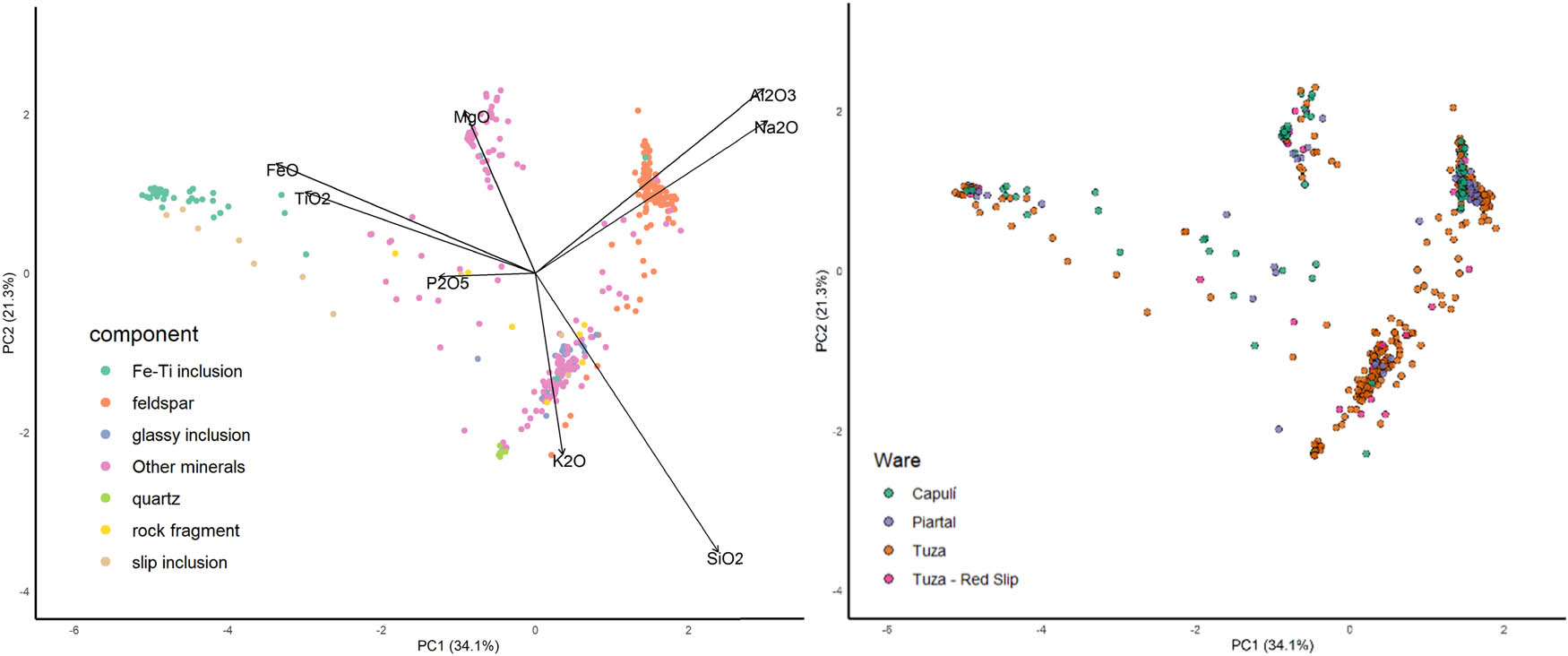

A PCA was performed on all the ceramic fabrics (n = 141) for the 12 elements retained. For the PCA, all Tuza samples were considered as a single group. The first nine PCs describe 92% of the total variance. The most defining elements for these ceramic fabrics are Fe, Mn, Zn, K, and Al (Figure 9). The distribution of the ware groups in relation to the first two principal components is shown in Figure 9, with PC1 enriched in most elements under consideration and depleted in Al, while PC2 is depleted in Mn, Fe, Zn, and Al, but enriched in K, Nb, and Ca. While the overall compositions of the ware fabrics do not easily resolve, it is apparent that Capulí ceramic fabrics are compositionally somewhat different than Piartal and Tuza, and are enriched in Mn, Fe, and Zn relative to the other wares under study. Piartal and Tuza ceramics have a more similar composition, although Tuza is slightly enriched in K compared to the Piartal wares.

Bivariate plot comparison of compositional data using PC1 (representing 23.1% of total variance) vs PC2 (14.7% of total variance) for the ceramics measured by pXRF. Confidence ellipses indicate 90% confidence interval for group centroid and are only displayed for the three decorated wares.

While two groups of Piartal vessels were identified morphologically, the same groups did not resolve compositionally. A total of 14 Piartal vessels were analysed by both XRF and GMM, nine of which were in the Piartal-1 group and five of which fell into the Piartal-2 group. Twenty-one other Piartal fragments were analysed by XRF but were fragmentary and not included in the morphological study. There is some indication that Piartal-2 is enriched in K, Ca, and Nb compared to the samples in the Piartal-1 group and the Piartal fragments that were not included in the morphological study (predominantly from excavations in Catambuco) (Figure 10); however, the small sample number and overlapping chemistry do not allow for any resolution of this.

Bivariate plot comparison of compositional data using PC1 (representing 23.1% of total variance) vs PC2 (14.7% of total variance) for the Piartal ceramics distinguished by the morphological groups as measured by pXRF. Confidence ellipses indicate 90% confidence interval for group centroid.

4.3 Fabric Inclusions

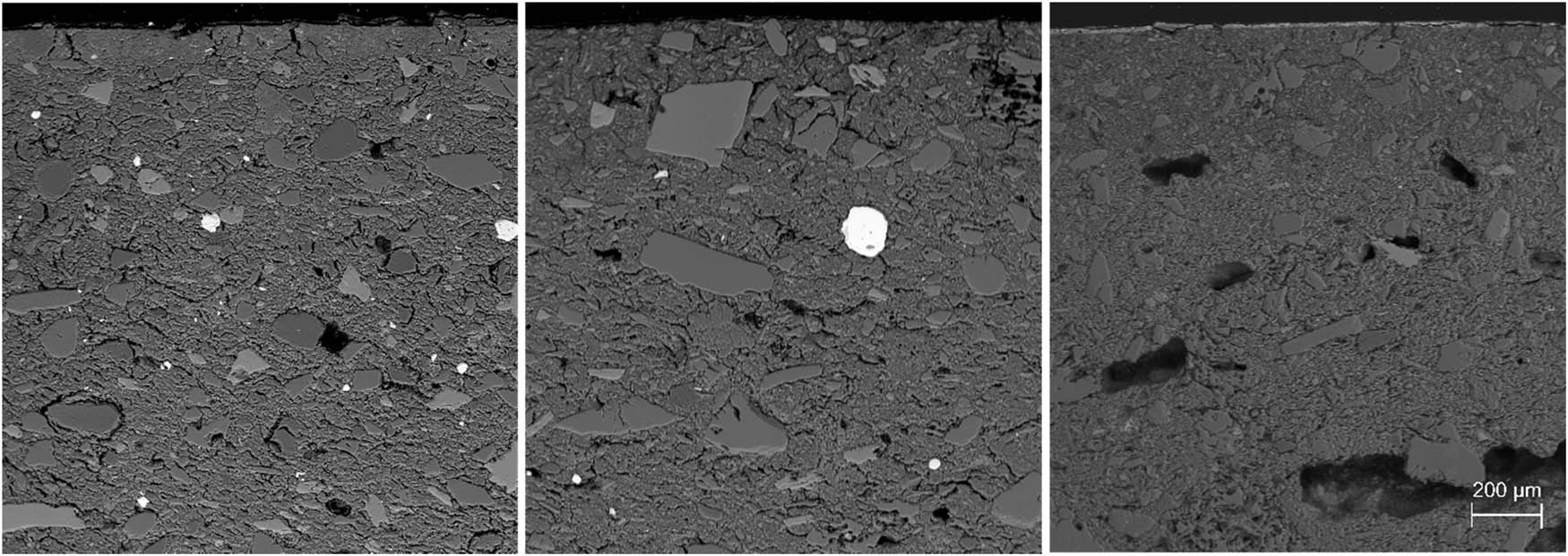

Several consistent types of inclusions were identified in the ceramic matrix (Figure 11) when examined in polished cross section by SEM-EDS: these include distinctive fragments of volcanic glass (tephra), titanium-bearing iron-oxide, quartz, as well as inclusions that compositionally consist of volcanic rocks and minerals.

BSE images of (left to right) of Capulí (CA230443), Piartal (CA230176), and Tuza (CA230163) ceramics scaled for direct comparison.

The chemical composition of inclusions in the ceramic fabric were analysed by EDS, averaging 37 analyses per sample (EDS results reported in Supplementary Material). A principal component analysis was performed on all the inclusions (n = 449) for the major elements (SiO2, Na2O, MgO, Al2O3, P2O5, K2O, CaO, TiO2, and FeO) (Figure 12), with clear groups present in the data including feldspars, a group of 44 inclusions enriched in MgO (mostly basalts), a large group enriched in K2O which includes the volcanic glass inclusions, quartz inclusions, and titanium-bearing magnetite (including the slip inclusions). Comparing inclusion types to wares, we do not see any clear divisions, with all inclusion types being found in Capulí, Piartal, and Tuza samples. The inclusions suggest that the materials are being sourced from a similar volcanic environment; however, there are some differences in the abundance and chemical variation within these groups that suggest the exploitation of different clay sources.

PCA major element for all inclusions analysed by EDS, showing (left) element vectors and inclusion type and (right) the inclusions groups by decorative ware.

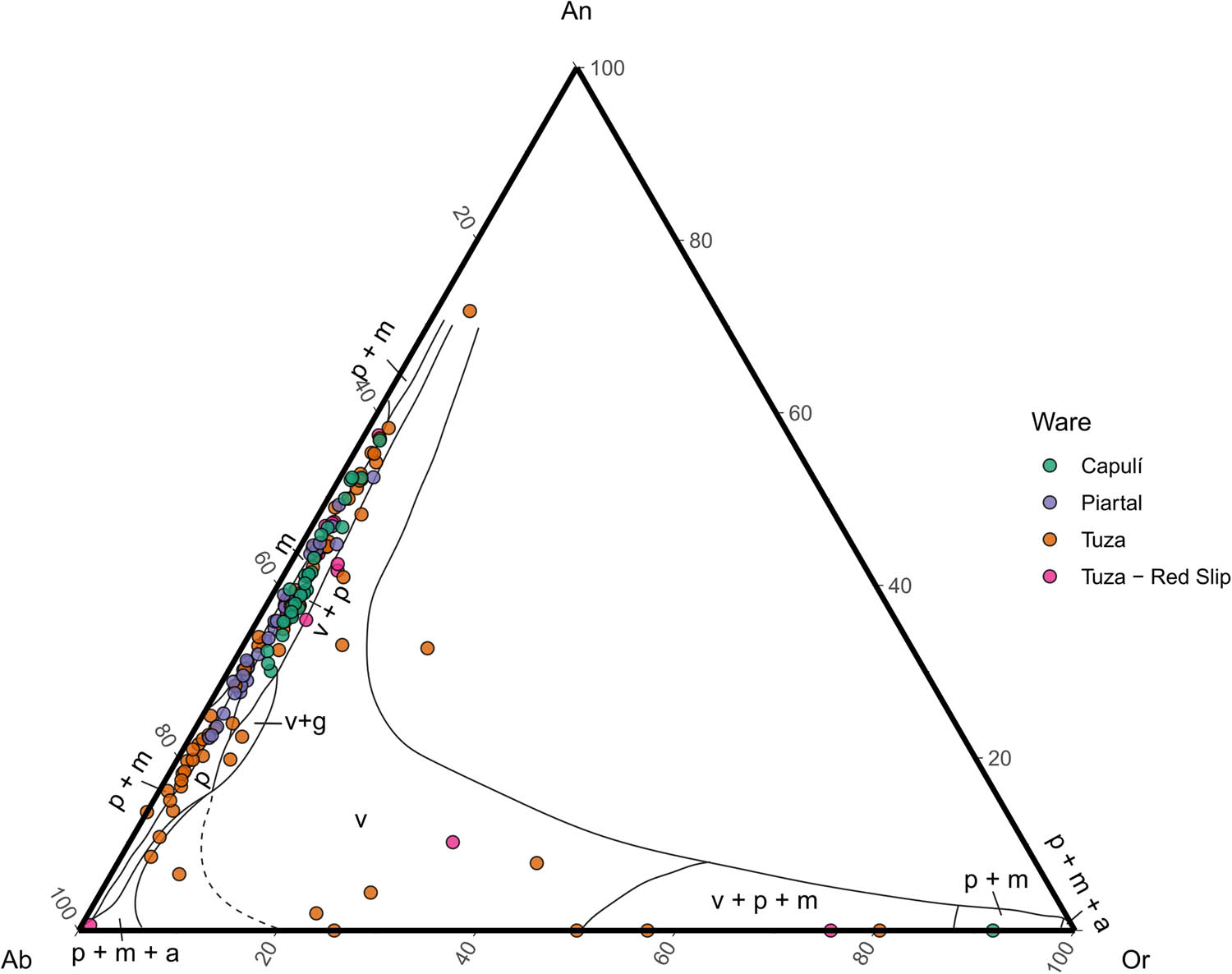

A total of 144 feldspar inclusions were identified across all 12 samples. The normative proportions of albite (Ab), anorthite (An), and orthoclase (Or) for these inclusions were calculated for the feldspars based on their chemical composition following Trevena and Nash (1981) (also refer Freestone (1982) and Martinón-Torres et al. (2018)) (Figure 13). Most represent plagioclase feldspars, with normative compositions plotting in the volcanic and volcanic+plutonic regions of the ternary diagram; only ten examples showed an alkali feldspar chemistry. Even though plagioclase feldspars are present across all three wares, Capulí samples display a more constrained chemistry (Figure 14) while Tuza samples include a wider range of plagioclase and alkali feldspars (Figure 14 and Supplementary Materials).

Compositions of the feldspar inclusions (n = 144) plotted in terms of their weight percent of An, Ab, and Or components overlying boundaries between feldspars from different rock types (redrawn after Trevena and Nash (1981)). v: volcanic; p: plutonic; m: metamorphic; v + g: volcanic or granophyre; v + p: volcanic or plutonic; p + m: plutonic or metamorphic: v + p + m: volcanic, plutonic, or metamorphic; p + m + a: plutonic, metamorphic, or authigenic.

Compositions of the feldspar inclusions in (left) Capulí (n = 29), (middle) Piartal (n = 36), and (right) Tuza (n = 64), and Tuza – Red Slip (n = 19). All compositions are plotted in terms of their weight percent of An, Ab, and Or components.

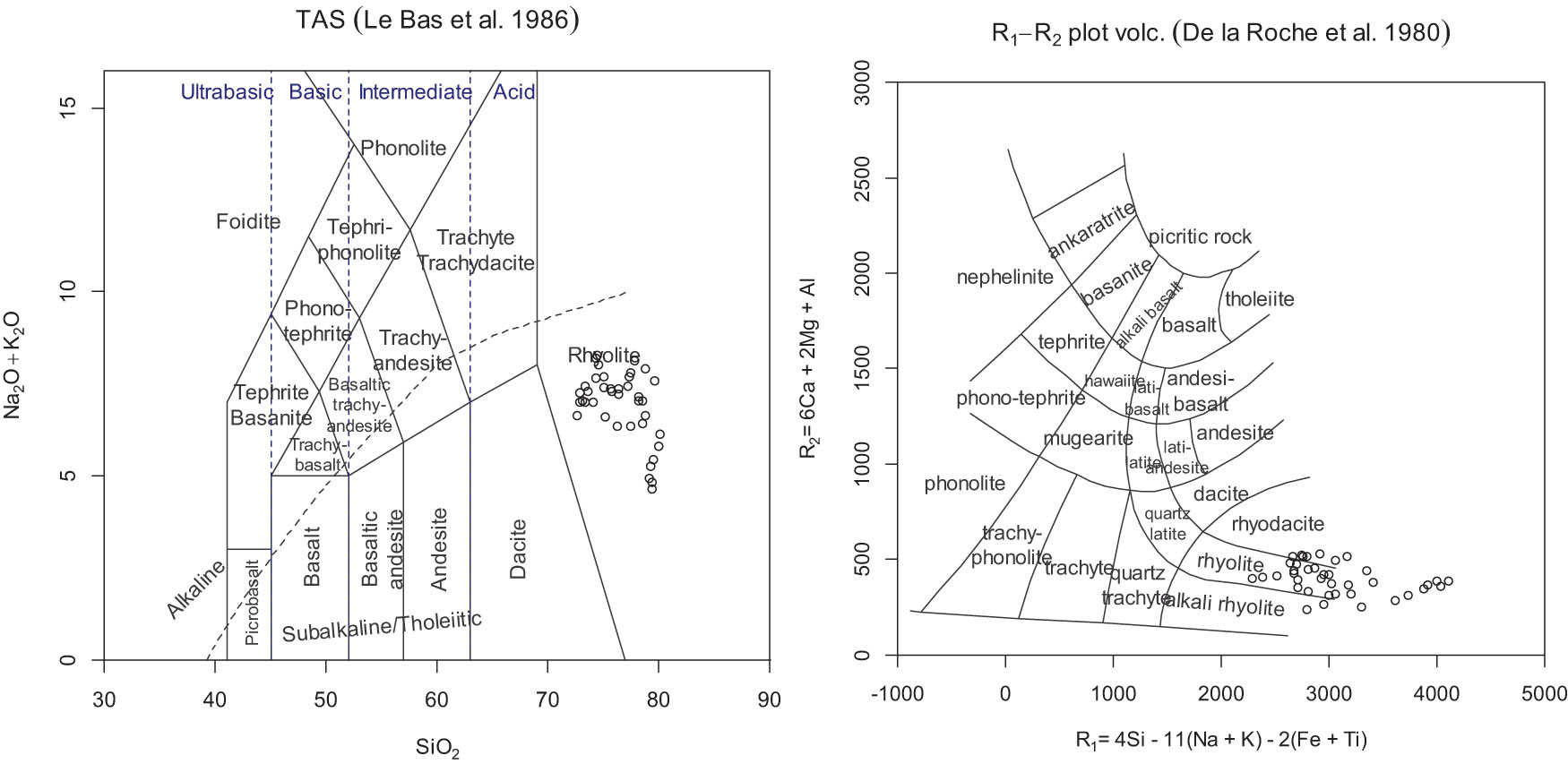

Volcanic glass was identified morphologically in the cross section of embedded and polished samples, as shown in Figure 15. While volcanic glass was observed across eight samples, the Tuza ceramics displayed proportionally more volcanic glass inclusions, with only one example identified in Capulí and Piartal fragments. There was no clear compositional distinction in the volcanic glass (Figure 16), and all were compositionally classified as rhyolites (Figure 17), occasionally falling outside the compositional field. The chemistry of the individual glassy inclusions within samples are similar (Figure 16), clustering by sample, with some samples having two different clusters of glassy inclusions. This could be reflective of the original volcanic glass chemistry which varied slightly from sample to sample, but it could also be the result of compositional change which occurred during the firing of the vessels, and which could alter the inclusions based on the immediate local environment in the ceramic fabric.

BSE image of tephra (volcanic glass) inclusions in a Tuza style ceramic (CA230163).

A scatterplot of SiO2 vs Al2O3 concentrations (in wt%) showing the compositional variation in glassy inclusions in eight samples as analysed by EDS.

Classification of the glassy fragments from the analysed pottery samples, based on two common systems for classification of volcanic rocks (left) and volcanic glasses (right). Created using the GCDkit package in R.

4.4 Surface Decoration

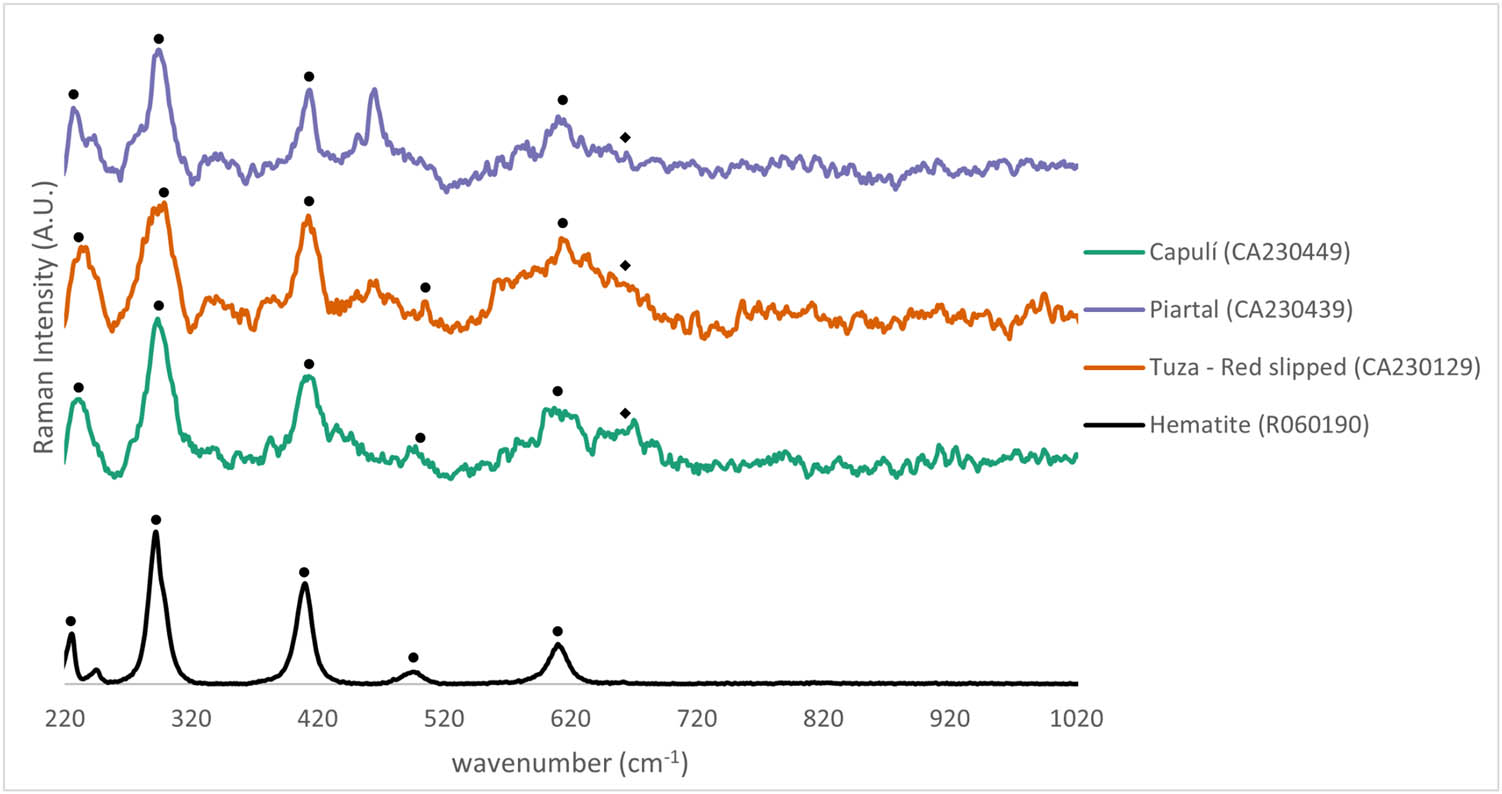

Red decoration was incorporated in all three wares, either through the application of a red slip or wash covering the entire decorative surface, or a red slip-paint employed in the application of decorative motifs. The red decorative components on all wares exhibited a similar chemistry when analysed by pXRF, defined by elevated concentrations of iron and titanium compared to the underlying component (Figure 18). This was confirmed by SEM-EDS on eight samples, where the red slip and slip-paint’s composition across all wares was shown to be composed of a large quantity of micron or sub-micron sized iron-rich particles mixed with a clay binder (Figure 19), whose bulk composition averaged 13.43 wt% Fe2O3 and 1.62 wt% TiO2 (Supplementary Materials). The Tuza vessels, both with the painted motifs and the “Red slip” examples had the most elevated concentrations of iron particles in the slip layer, reflected both in the microstructure and bulk composition (average 17.72 wt% Fe2O3). Raman analysis confirmed that the iron oxide was in the form of a Ti-bearing hematite (Figure 20), identified by the strong increase in peak intensity and peak width at 660 cm−1 (Krolop et al., 2019, p. 77). This unique signature was observed on all three wares and suggest that similar iron-oxide sources were being exploited for use in the red decoration for Capulí, Piartal, and Tuza ceramics.

Relative concentrations of elements in the red decoration compared to the underlying layer for the following elements: Fe (left), and Ti (right). All concentrations are reported in ppm.

Cross section showing the interface between the red decoration and underlying ceramic fabric on (a) Capulí (CA230449), (b) Piartal (CA230439), and (c) Tuza (CA230172) ceramics with the paint/slip fabric interface indicated in a dashed line. BSE images were taken at 1,000× mag, 20 kV, and scaled for direct comparison.

Raman spectra of the red paint layer on Capulí (CA230449), Piartal (CA230439), and Tuza – Red Slip (CA230129) fragments compared to reference spectra for Hematite (R060190) from the RRUFF database. Characteristic peaks for Hematite (•) were identified at 224, 290, 410, 492, and 610 cm−1, while the characteristic peak resulting from titanium substitution in hematite (◆) was observed at 660 cm−1 (Krolop et al., 2019; Varshney & Yogi, 2014).

Brown paint is only present on Tuza ceramics with positive painted motifs. The brown paint is enriched in Mn and Fe compared to the underlying areas, with twice as much Fe and seven times as much Mn observed in the brown painted layers compared to the underlying cream slip when measured by pXRF. Raman analysis (Figure 21) identified the pigment as jacobsite (Mn2+Fe3+ 2O4) and magnetite (Fe2+Fe3+ 2O4), spinel group minerals that form a solid series and have a strong black to brown colouration. Jacobsite and magnetite have previously been identified as the mineral paint used to create pre-fired black painted decoration on Late Intermediate period ceramics (ca. AD 900–1400) from northwest Argentina (Centeno et al., 2012; Lynch et al., 2022; Tomasini et al., 2020). Hematite was also identified in one sample (CA230163), which could either be a minor mineral inherent in the brown paint, or originate from the underlying layers (Figure 21). The brown paint is composed of a large amount of ground mineral pigment mixed with a minimal amount of clay binder to form a thin paint (∼10 μm) (Figure 22).

Raman spectra of the brown paint layers on Tuza fragments (CA230163 and CA230172), compared to reference spectra for Hematite (R060190), Magnetite (R060656), and Jacobsite (R070719) from the RRUFF database. Characteristic peaks are indicated by (•) for Jacobsite, (◆) for Magnetite, and (Δ) for Hematite.

BSE image of the interface between the brown decoration and underlying cream slip on a Tuza (CA230172) style ceramic fragment.

4.4.1 Burnishing

Burnishing, or the use of a hard, smooth object such as a pebble, piece of wood, or bone tool, to rub the surface of the vessel when it is leather hard to create a shiny surface (Berg, 2008; Ionescu et al., 2015), was identified in all wares. The evidence of burnishing was noticed by macroscopic observation, surface texture analysis from 3D scanned objects, and in microscopic analysis of ceramic cross sections.

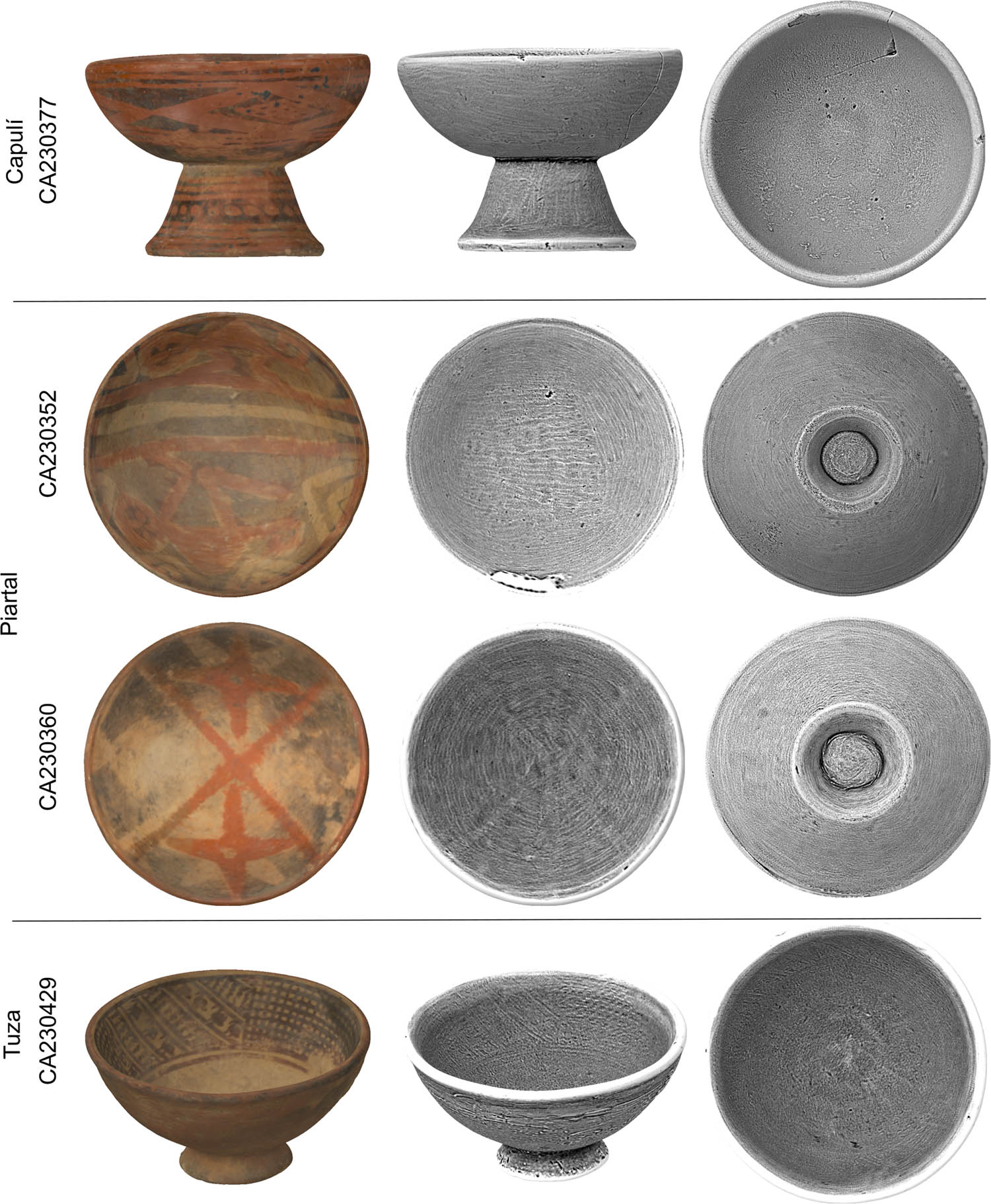

Visible, directional burnishing is distinctly present on Capulí and Piartal vessels, but is not a prevalent feature of Tuza vessels. Capulí and Piartal styles are usually burnished on their decorated surfaces, and the craftspeople were choosing to orient the direction of burnishing marks to be parallel to one another and to follow contours of the vessel. This can be visualised on the 3D scanned objects when using a Multi-Scale Integral Invariant (MSII) filter (Figure 23). This feature is used to highlight small details in 3D models, such as fingerprints (Mara & Krömker, 2017; Mara et al., 2010) and in our data, it renders the relief of burnishing marks more perceptible, as well as positive and negative painted features. While patterned, directional burnishing is visible on Capulí and Piartal objects, Tuza vessels do not show visible polishing marks on their decorated surface (interior of bowls). There are occasionally thin, minimal burnishing lines visible on the upper portion of the exterior of these bowls, but this style of burnishing stands in stark contrast to the dense, systematic, parallel burnishing seen on the other two wares.

Images of 3D objects with (centre and right) and without (left) MSII filtering to visualise paint and burnishing details. Capulí and Piartal display examples of directional burnishing while the Tuza only shows details of paint. Visualisations made in GigaMesh (build: 22nd June 2023).

As shown in Figure 19, Capulí and Piartal ceramics demonstrate an irregular slip-fabric interface, contrasting with a flat surface, which suggests that the bowls were burnished only after the red slip or slip-paint was applied. Conversely, Tuza style ceramics have a very flat, uniform slip-body interface, suggesting they were first burnished to create the uniform surface, and then an even coating of red paint was applied. It is clear that the employment of directional burnishing on the Capulí and Piartal vessels was a deliberate aesthetic choice by the craftspeople, and that in both cases this burnishing was done after the application of the red slip or slip-paint. For the Piartal vessels, this sequence is a rather unusual choice, as it causes the red paint to smear during the burnishing process (Figure 23, vessel CA230360).

4.4.2 Negative Black Decoration

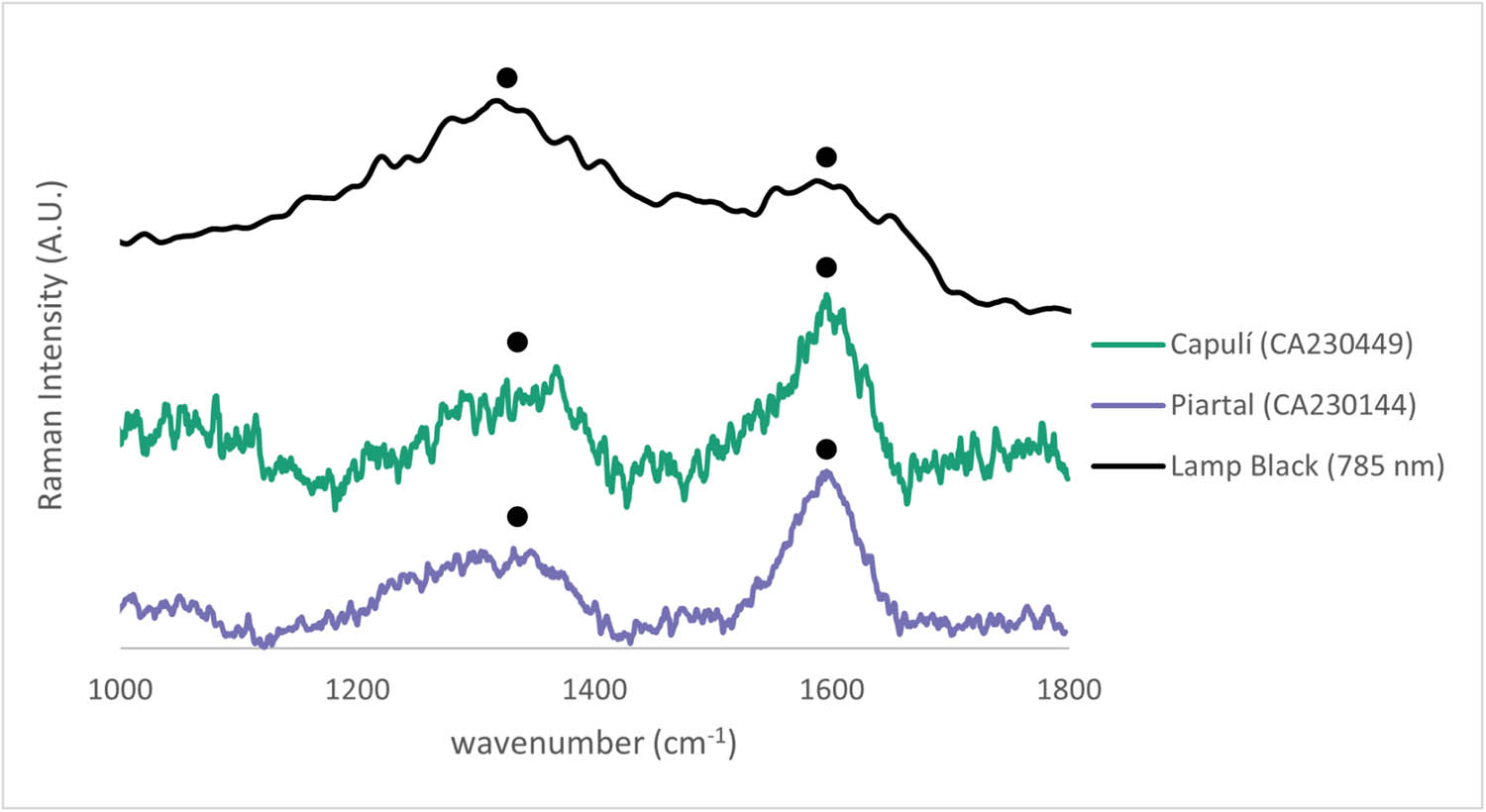

The black, negative decoration on Capulí and Piartal ceramics was achieved through resist painting the decorative motifs with a fluid protective material, such as liquid wax, before covering the whole vessel with a uniform layer of carbon. Analysis of the chemical composition on 73 Capulí and Piartal vessels showed no systematic increase in the common inorganic elements associated with black pigments, notably Fe and Mn (Figure 24), suggesting that the black decoration was not formed using a mineral-based black pigment. Eight Capulí samples from Site 137 yielded an elevated Mn signature (>0.2% Mn) in the surface analysis of vessels; however, this was associated with Mn-oxide accretions, which have been shown to form post-depositionally by manganese-consuming bacteria (O’Grady, 2009). Raman analysis identified the black layer on both Capulí and Piartal fragments as amorphous, disordered carbon (Figure 25) with characteristic broad peaks at 1,345–1,360 and 1,590 cm−1 (Łaciak et al., 2019). This suggests that the carbon black decoration was achieved through the application of charcoal or soot, applied through rubbing, smoking, or smudging. This decoration was almost certainly achieved after the vessels had been initially fired. Research by Shepard (1954) found that negative grey and black coatings, constituting the background of resist-painted negative designs, oxidised at temperatures below those required to transform the clay into a ceramic, indicating that the decoration was applied post-firing.

Relative concentrations of elements in the black decoration on Capulí and Piartal vessels compared to the underlying layer for the following elements: Fe (left) and Mn (right). All concentrations are reported in ppm.

Raman spectra of the black decorative component on Capulí (CA230449) and Piartal (CA230144) fragments, compared to reference spectra for Lamp Black from the Pigments Checker v.5 open access Raman Spectroscopy library (Caggiani et al., 2016). Characteristic peaks for amorphous carbon (soot/charcoal) at 1,345–1,360 and 1,590 cm−1 are indicated by (•).

5 Discussion

5.1 Updated Ware Definitions

As with any archaeological study, the classification of these ceramic objects into ware categories is not the end goal of this research in and of itself. Instead, we see these ware definitions as a way for us to structure and organise our data, clearly communicate the results of this research through a shared terminology and nomenclature, and identify relationships between objects (Rice, 1987), so that we may better engage with these ceramic objects to understand the people who made, used, and were buried with these ceramic vessels in the past. With that in mind, we propose the following refined ware definitions to better classify decorated ceramics from the Serranía nariñense region.

Capulí – The decorated area of the ceramic is covered in a red slip, and directionally burnished following the contours of the vessel. Vessels can have, but do not need to have, incised decoration. The vessel is then fired, and sometime after firing, a design is painted in a resist material and subsequently covered with an organic black layer to create negative designs.

Piartal – The decorative area of the ceramic is covered in a cream slip and a simple design is painted in red slip-paint. Vessels can have, but do not need to have, incised decoration. The vessel is then directionally burnished following the contours of the form, and fired. Once fired, most, but not all vessels, have a more elaborate design painted on with a resist material which is then covered with an organic black layer to create negative designs.

Tuza – The decorative area of the ceramic is covered in a cream slip and the surface is burnished leaving no visible burnishing marks. Designs then are applied to the decorative area in red and/or brown slip-paint and the vessel is fired. No post-firing decoration is employed.

These definitions focus not just on the type of decorative elements used, but also how and when these decorative elements were applied, from which we can begin to identify technological commonalities (Rice, 1976). The features described in the refined ware definitions can all be identified macroscopically, which allows for easy identification of materials in the field, including on fragmentary material.

5.2 Shared Materials, Shared Practices

By reconstructing key stages of the three chaînes opératoires, we can begin to disentangle the unique technological relationships between these three wares, and offer tentative insights into craft organisation in the Serranía nariñense region. As shown in Figure 26, all three wares were produced using similar raw materials and production methods, although these were combined in different and meaningful ways.

Simplified decorative chaînes opératoires for Capulí, Piartal, and Tuza ceramics.

5.2.1 Raw Material Sourcing and Chronology

The composition and mineralogy of the ceramic fabrics suggest that they were made using locally available raw materials. The bulk compositional data did not resolve any groups that would suggest multiple production centres or exploitation of unique clay deposits within the wares, instead the chemistry is homogeneous and overlapping. While it is tempting to suggest that this indicates the exploitation of single clay source for all materials, the chemical homogeneity is more likely reflective of the similar geology present across the Serranía nariñense region, which is characterised by Pliocene, Pleistocene, and Holocene unconsolidated ash fall deposits and intermediate volcanic rocks. If there were subtle differences in the underlying geology, it is also the case that these are not detectable by pXRF, and would perhaps resolve using more invasive or destructive analytical methods such as petrography, LA-ICP-MS, or NAA. Capulí ceramics do, however, have a somewhat unique composition compared to the Piartal/Tuza vessels which suggests that the potters may have been exploiting different clay beds. The Capulí vessels have a red to orange oxidised fabric colour while the Piartal and Tuza vessels have a lighter coloured cream to tan fabric, corresponding with the higher iron oxide content of the former, which could suggest that the difference in clay selection was driven by the desire for a specific colour of ceramic fabric. Undecorated ceramics recovered in context with both Piartal and Tuza ceramics have red or orange fabric colour (Groot de Mahecha & Hooykaas, 1991; Uribe, 1977–1978), so the choice of a clay that fires to cream colour for the decorated wares appears to be an intentional, technological choice.

Piartal and Tuza have a very similar fabric composition, albeit with Tuza being slightly enriched in potassium. This aligns with the microstructure, with the latter containing a higher proportion of volcanic glass fragments composed of potassium-rich (3.72 ± 0.86 wt% K2O) rhyolitic glass. This suggests that Piartal and Tuza are exploiting very similar/the same clay sources, although the Tuza had more volcanic glass inclusions, which we assume are inherent to the clay source. While Barone et al. (2010) demonstrated that the volcanic glass in ceramic fabrics undergoes chemical modification during the firing process and thus is not an ideal candidate proxy for provenance, the increase in tephra inclusions in the Tuza fabric is significant. This increase in tephra inclusions can either suggest the exploitation of a different, volcanic ash-rich clay deposit for Tuza vessels, or that there was a volcanic event that altered the clay source sometime between the production of Piartal and Tuza vessels in the Atriz valley.

Assuming that the increased tephra in Tuza ceramics is reflective of a volcanic event prior to their production, we may be able to tentatively narrow the dates of production of Tuza vessels in the Atriz valley. The Galeras volcano, on which the Obonuco and Catambuco sites lie on the slopes, is one of the most active volcanoes in present-day Colombia. It has been active for more than a million years, but for the past approximately 4,500 years it has been characterised by small scale periodic eruptions with pyroclastic flow deposits, ash-rich paleosols, and tephra-fall layers (Banks et al., 1997). Historic accounts of eruptions date back to the sixteenth century CE and include over 50 periods of volcanic unrest (Banks et al., 1997). The earliest recorded eruption was by Cieza de León in 1547 and is assumed to occur in the period before his arrival in Pasto, sometime in the early sixteenth century CE (1500–1547) (Espinosa Baquero, 2001). The eruption is described as involving a great deal of smoke and releasing vast amounts of rocks. Prior to that event, there has been one identified major volcanic episode in our period of interest, which occurred around 750–950 CE (1–1.2 ka) (Banks et al., 1997). This volcanic episode, which is dated by radiocarbon dating of charcoal samples in pyroclastic-flow deposits (Figure 27), included the deposition of a pumice tephra-fall on the eastern slopes of the volcano.

Calibrated radiocarbon dates from the Municipality of Pasto for sites associated with Piartal (purple), Tuza (orange), and undecorated (dark grey) ceramics. The radiocarbon dates associated with the 1–1.2 ka volcanic episode are indicated in light grey (Banks et al., 1997), as are the range of possible dates for that event and the 1500–1547 CE Galeras volcanic episode.

In the vicinity of Pasto, we have ten absolute dates for contexts associated with Piartal and Tuza ceramics. The best dated site in the region is the cemetery of Maridíaz, Pasto (Cárdenas Arroyo, 2020), which yielded both Piartal and Tuza style ceramics. There are five radiocarbon dates from the site, obtained from four different tombs. The dated tombs either had no decorated ceramics (BMT-G [Beta-452851]: 1296–1400 cal CE and BMT-V1 Z2 [Gx-15474-G]: 1406-present), anthropomorphic ceramics but no Tuza or Piartal vessels (BMT-22.10 [Beta-452849]: 1305–1419 cal CE), or only Tuza ceramics (BMT-31.13 [Beta-34827: 1494-present and Beta-452850: 1447–1632 cal CE]) (Cárdenas Arroyo, 2020). While there certainly is a Piartal presence on the site, and a tomb with both Piartal and Tuza ceramics, there is no date for the Piartal material in Maridíaz, and the Tuza ceramics appear to date to a relatively late period. Four different sites in the vicinity of Pasto have yielded Piartal material and reported absolute dates, including the site of Jongovito in the vicinity of Catambuco (Beta-39576: 404–890 cal CE) (Groot de Mahecha & Hooykaas, 1991), El Retiro which lies to the east (Beta-76183: 537–668 cal CE) (Patiño, 1994), the Obonuco tomb in this study (MAMS-6597: 1040–1159 cal CE and MAMS-6598: 1050–1215 cal CE), and a looted tomb in Catambuco with a Piartal ceramic fragment dated by thermoluminescence (UW-3907: 960–1300 cal CE) (Cárdenas Arroyo, 2020). Taking these dates into consideration (Figure 27), the 1500–1547 CE volcanic episode is a candidate for producing the tephra fragments present in the Tuza vessels but not in the Piartal material. While more work is needed to confidently identify this dating, including obtaining dates for other sites with Tuza vessels (notably San Damián) and more extensive survey of Tuza ceramic fabrics, this initial analysis suggests a late production of Tuza style vessels in the Atriz valley. This late date also aligns with the observation that a number of Tuza – Red Slip samples from the site of San Damián show evidence on their bases which could suggest they were wheel-turned, indicating that production of this ware may have continued into the colonial period.

5.2.2 Forming

While all three wares share the same forming method (coil-built, hand shaped), there are differences in morphology and morphological variation which suggest differences in craft organisation between these wares. The standardisation hypothesis proposes that the higher the rate of production by any single producer, the more uniformity will be present in ceramic products (Costin, 1991, 2000; Costin & Hagstrum, 1995). Conversely, the less variability observed in a ceramic assemblage, the fewer the number of full-time potters must have been involved in the production (Roux, 2003). Thus, a devoted, full-time pottery workshop with a few specialists producing goods for the entire population will result in more standardisation than many individual potters producing vessels for household consumption. The sole focus on standardisation as a proxy for specialisation, however, has been criticised (Arnold, 2000) as has the prioritisation of “specialised” production in studies of craft organisation (Clark, 2008). However, how homogeneous a ware’s composition, morphology, or decoration are in relation to other wares produced in a region is still a useful metric to analyse when comparing technological traditions and assessing their possible connections.

Capulí vessels display the most morphological variation among the three wares. This includes differences in the height, width, and shape of the pedestalled base, as well as in the shape of the rim on the bowl. This suggests that there was relative freedom in the shape of the pedestalled-bowl for Capulí vessels, and that consistency in the morphology of the vessel was not necessarily a desired component of the production. This could also suggest that the production of Capulí vessels was more dispersed, with more people engaging in production compared to Piartal and Tuza vessels. The results also indicate that there may be some local styles present in this ware. The subgroup of six Capulí vessels with the flared bases are mostly represented by excavated samples from Site 137, suggesting that this could be a local style. Three of the vessels were recovered from a single tomb (LS 1). However, there is one example in this group from the Bomboná pottery collection (CA230405) which is attributed to the Los Eucaliptos locality in Bomboná, Consaca. Additionally, the incised feature present on three of the examples, including the one from the Bomboná pottery collection, has also previously been observed by Francisco (1969) on vessels from Carchi, Ecuador. If it is a local style, the feature is not constrained to Site 137, and more research would be needed to assess whether these morphological and stylistic features indicate a specific production group centred in the Iles area, or whether these are features commonly employed across the region.

Piartal vessels are the only style that clearly differentiated into more than a single morphological group, which could indicate that in this region, there were two different groups or production centres which existed concurrently and favoured slightly different vessel shapes. If this was the case, one would expect that these vessels would also have distinct ceramic fabrics, as ethnoarchaeological research suggests that potters tend to exploit clay in the vicinity of their production location (Arnold, 1985, Table 2.1). However, with our sample size and methods of analysis, we cannot identify any compositional distinction between the two Piartal forms. Alternatively, the two morphological groups could represent a sequence of development. Given the morphological similarity between the Piartal-2 group and the Tuza vessels in this study, we favour the latter hypothesis. The Tuza style has generally been accepted to have developed after, and out of, Piartal ceramic traditions (Uribe, 1977–1978). Given the similarity in the bowl shape between Piartal-2 and Tuza vessels, we suggest that Piartal-1 vessels were made in an earlier phase, while Piartal-2 was made later, and this was the morphological shape that continued to be produced with Tuza style designs. The only Piartal vessels in this study which have an associated absolute date are the vessels recovered from the Obonuco tomb, which dates between 1040–1215 cal CE, and these all fall into the Piartal-1 group.

The Tuza bowls have the most consistent, confined shape, which suggests that uniformity in vessel shape was a favoured feature in the production of this ware, that there was a higher level of control in its production, there were fewer production hands involved, and/or the producers had an overall higher level of expertise. As noted above, there are also examples of vessels with Tuza style decoration, which show evidence on their bases which could suggest they were wheel-turned, indicating that production of this ware may have continued into the colonial period, this change in forming or finishing method could lead to the increase in vessel uniformity observed across the assemblage. However, this uniformity may also be biased by the nature of our sample. Tuza is the only style in the morphological study that predominantly includes examples from collections (88%), as opposed to a combination of vessels from controlled, systematic excavations and those from acquired collections (Piartal – 48% from collections, Capulí – 21% from collections). It was noted by Francisco (1969, p. 90) that compared to Capulí and Piartal ceramics, Tuza vessels were not of interest to looters, and when they were, the focus was confined on the footed bowl shape. Therefore, it is not unreasonable to hypothesise that the lack of variation in morphology of the Tuza ceramics that we observe in our data is actually a consequence of looters or collectors preferentially selecting “ideal” shaped vessels, and is not an accurate reflection of the diversity of vessel forms present in Tuza style ceramics.

5.2.3 Decorative Elements

The three wares all incorporate red in their surface decoration. The composition of red decorative elements employed across the three wares suggests that potters were exploiting a common raw material, in this case, a Ti-bearing hematite, and preparing it in similar ways to create the red slip or slip-paint. While Tuza ceramics are the only ware to use a brown decorative element, the brown slip-paint appears to be prepared in the same manner as the red slip-paint, with the mineral pigment ground to a fine particle size and mixed with a minimal amount of clay. The main observed difference between the wares when it comes to the positive painting technology appears to be its application sequence relative to the burnishing of the vessel.

Capulí and Piartal share similar burnishing characteristics including when they were burnished (after the red decorative component applied) and the use of a burnishing technique that left visible, directional marks. This is in opposition to Tuza ceramics, which were also burnished, but their burnishing stage occurred before any coloured decoration was employed, and the burnishing strokes are not distinguishable by the naked eye, nor do they appear to occur in identifiable patterns. While linear and pattern burnishing has been employed in the decoration of ceramics from the Neolithic period onwards (Ionescu et al., 2015), it is not commonly accompanied by painting or other decoration. The added painted designs on the Capulí and Piartal ceramics (achieved through slip-paint and resist-painted negative decoration), cover up the directional burnishing marks to an extent, and create a more complex design field which makes isolating the directional burnishing visually more difficult. The choice to employ directional burnishing may be related to a wider technological and stylistic preference by pre-Hispanic craftspeople in the Serranía nariñense region. Goldwork from the region also incorporates directional polishing marks (Quintero Guzmán et al., 2016), suggesting that the burnishing marks may be a preferred aesthetic or technological feature that extends beyond the decorative scheme or any single vessel.

Capulí and Piartal ceramics also share the employment of negative design elements, as well as the technique used to achieve those designs. The negative decoration was achieved post-firing through the application of amorphous carbon over a resist painted design. Negative decoration, like directional burnishing, is also a decorative feature used in goldwork from the region, and further suggests stylistic and technological parallels between the two materials. Both Capulí and Piartal ceramics also occasionally included incised decoration, although to different effects. Incision on Capulí ceramics appears to be constrained to the rims of pedestalled bowls, and occurs both in combination with other decorative elements, and on vessels without added red slip or negative painted designs. Incision on Piartal vessels occurs on the upper portion of lenticular pots, and can occur in combination with red slip-painted designs.

5.2.4 Decorative Episodes

Piartal style vessels underwent two distinct decorative episodes, and two types of motifs were employed in the decoration. The red decoration applied before burnishing and firing appears to be limited to a few types of patterns (Figure 28). These patterns were used to divide the decorative space, and included simple crosses and variations on crosses including swastikas, two parallel lines with a z pattern in the centre, concentric circles, and, rarely, simple zoomorphic figures (Francisco, 1969, p. 82). However, the resist-painted decoration in the second stage of decoration utilised a much more expansive vocabulary, and resist-painted patterns do not appear to have been replicated across different vessels. This results in vessels which share red motifs but have unique negative designs. This disparity may indicate that the two decorative episodes were not executed by the same individual, and indeed, it was not necessary for them to happen at the same point, as the post fired designs could have been applied at any point of the ceramics’ use life. In fact, the presence of “Piartal” ceramics with only red painted designs and no negative decoration suggests that there were pieces that never had this last decorative episode before deposition.

Photographs of the interior of Piartal style bowls sharing common simple motifs achieved in red paint, with distinct resist-painted negative decoration. The vessels are organised by their archaeological context/collection.

5.3 Technological Relationships

When considering the raw materials sourcing, forming, and decoration of these three wares, we conclude that there are three different relationships present. Capulí and Piartal ceramics share a common set of decorative methods, but there are marked differences in vessel shape and, to some extent, ceramic fabric composition. Piartal and Tuza vessels share common vessel forms and ceramic fabric (with the higher volcanic ash in Tuza perhaps reflecting simply a different chronology), but they have distinct decorative methods. Capulí and Tuza vessels do not share features beyond the common exploitation of broadly similar raw materials presumed to be available locally, a feature shared by all three wares. Different stages of the ceramic chaîne opératoire are considered to have different resistances to change due to the nature of the tasks and how they are learned and performed. Forming techniques, for instance, are considered to be a more conservative attribute of the ceramic production process (Gosselain, 2008; Mills, 2018), as the act of forming a pot is an embodied practice (Dobres, 2000). Similarly, we see the finishing techniques of burnishing also as a conservative, learned method that is resistant to change. Decorative styles, on the other hand, are considered more mutable as the motifs and designs used on vessels have been demonstrated to change over shorter periods of time, and multiple styles may be practiced within an individual maker’s lifetime (Mills, 2018). It is interesting, therefore, that we see different combinations of conservative and mutable characteristics between these wares.

While Capulí and Piartal vessels share the same general forming method (coil construction), finishing techniques (directional burnishing), and decorative sequences, they have distinct vessel morphologies, colour palettes, and somewhat distinct clay sources. Uribe (1977–1978) also observed the morphological discrepancy between Capulí and Piartal vessels and interpreted this, along with other archaeological information, as indicating that separate ethnic groups made these goods. This assumption relies on radiocarbon dating, which suggests that Capulí and Piartal ceramics were being produced and consumed concurrently, and thus do not represent a diachronic sequence. While some of our results also favour the conclusion that two separate communities made these objects, the similarities in production process suggest that there was shared technological information between them and that they did not exist in isolation. More absolute dates directly associated with Capulí and Piartal ceramic vessels are needed to assess whether these communities existed concurrently or diachronically. Regardless of their chronological relationship, the fact that there are several complex decorative methods shared between the Capulí and Piartal wares would suggest that there was the direct transfer of knowledge between the communities, and that we are not simply observing stylistic emulation.

Piartal and Tuza vessels, conversely, have some shared conservative features including vessel morphology and raw materials sources, which could suggest that the same community is producing both wares, but there is a meaningful difference in the decorative methods and sequence. The results suggest that there was a shift in the craft organisation, possibly resulting from introduction of outside technologies. Again, the results do not suggest that the change in decoration in Tuza vessels was simply the result of imitation of exogeneous pottery designs. Instead, the abandonment of the negative decoration, directional burnish, integration of new elements, and change in production sequence all suggest that there is a larger technological shift indicative of the introduction of foreign ideas or craft knowledge. The more standardised vessel form observed in Tuza style ceramics may also indicate that a more controlled production landscape occurred concurrently with this shift.

As with the relationship between Capulí and Piartal ceramics, more absolute dates directly associated with Piartal and Tuza ceramic vessels are needed to assess when this transition occurred, and therefore, what were the social changes which could have influenced this change in ceramic production. Considering known exogeneous sources, two major, albeit unlikely, candidates emerge: influence from Inka potters corresponding with the Inka northward expansion in the fifteenth and sixteenth century CE, and influence from Spanish potters in the sixteenth century CE. The latter option, given its late date, is considered unlikely to be the candidate for the catalyst event leading to the transition from Piartal to Tuza style designs. However, the occurrence of vessels with Tuza designs, which may have been shaped or finished using a pottery wheel, suggests Tuza style pottery was produced into the colonial period, and in communities which shared technological knowledge regarding the production of ceramic vessels. Turning to the former option, while it is generally accepted that the Inka military control did not extend into the Carchi and Nariño regions (Bernal Vélez, 2020), there was some Inka presence in the region, especially in Carchi, which can be observed on ceramics (Francisco, 1969; Meyers, 1998). Francisco (1969) describes a Tuza style piece from Carchi which incorporated Inka features, including the “llamitas” design and an Inka band, which she uses to demonstrate the late placement of Tuza style ceramics in her chronological sequence. She also identified the use of black (as opposed to brown) slip on some Tuza vessels as an introduction by the Inkcas, and its rare occurrence is attested due to the short occupation of the Inca in the Carchi region. However, there have not been similar Inka or Inka influenced pottery found in Nariño (Bernal Vélez, 2020). This does not completely rule out the Inka influence as the catalyst for change, but the current archaeological evidence would support a rather indirect mechanism of introduction.