Abstract

This article explores the pressing need for consistent structured guidance and training in post-excavation (PX) skills within the field of archaeology. This need was identified through consultations with commercial practitioners facilitated by the Federation of Archaeological Managers and Employers as part of the Archaeologist’s Guide to Good Practice (AG2GP-Handbook) project. Through collaborative work with a range of archaeological practitioners across the UK, within the limits of a 1-year AHRC/UKRI budget, the project has successfully developed prototype online resources at https://archgoodpractice.com/ that embody and promote FAIR and sustainable best practices within the commercial archaeological sector for wider public benefit and use internationally. PX skills are critical for transforming and synthesising raw field data into meaningful insights about the past. The AG2GP-Handbook project focused on improving stratigraphic analysis, but this work highlighted that current educational and professional training across the UK, and beyond, often falls short of equipping archaeologists with these capabilities. The article examines related key challenges, such as gaps in university education and continuing professional development, that leave graduates and junior field practitioners ill-prepared for professional PX demands and with a very limited grasp of how their records in the field should be used afterwards.

1 Introduction

Post-excavation (PX) skills in archaeology encompass a comprehensive set of competencies essential for transforming raw excavation data into meaningful interpretations of the past. These skills include stratigraphic analysis and chronological modelling to decipher the chronological sequence of site development, artefact processing and conservation to preserve and document materials recovered, and material culture analysis to study artefacts in detail. Increasingly, the hard sciences along with environmental archaeology play a key role in this process, facilitating the examination of botanical, faunal, and human remains to reconstruct past environments and human interactions with them. PX skills also involve robust data management, including the use of databases, quantitative and statistical analysis, and spatial analysis through geographic information systems (GIS). Critical interpretation and synthesis of all collected data enable archaeologists to build comprehensive narratives about past societies. For effective synthesis, “It is however crucial that there is consistency in terms of classification and typologies, and robust mechanisms for the assessment of significance of all classes of evidence within archives. It is also vital that there is sufficient consistency in terms of the methodologies used for data collection and its analysis” (Bryant et al., 2024). Effective dissemination of findings through a range of publication types (such as internal/contract assessment reports or other “grey literature,” peer-reviewed journal articles, popular science magazines, online open-access platforms, and monographs) serves different purposes and audiences. In contract or commercial archaeology, for instance, concise compliance reports may fulfil legal or regulatory obligations, whereas formal academic articles and monographs preserve a permanent scholarly record of interpretation and data. Public-facing media (including blog posts, social media threads, and museum or heritage centre exhibits) convey the significance of archaeological findings to non-specialists, thereby fostering broader community engagement and support. As a result, publication and reporting skills must be flexible enough to address both scholarly discourse and wider public interest, ensuring that knowledge is not only generated but also accessible. As such, the skills required for PX are partly determined by the types of publication outputs envisaged, shaping everything from how and why data are created and interpreted in analysis to how final narratives are crafted, peer-reviewed, and disseminated. Additional skills include data management, archiving and curation for long-term preservation of artefacts and records, project management to oversee PX processes, collaboration with specialists across various disciplines, adherence to ethical and legal standards, and the ability to disseminate findings further through presentations and outreach initiatives.

This article addresses three interwoven themes that collectively shape the challenges and opportunities in archaeological practice. First, it focuses on stratigraphic analysis, long viewed by many practitioners as a “dark art” yet fundamentally crucial for synthesising and interpreting archaeological data during PX. Second, it explores the broader scope of PX analysis, noting that many essential PX competencies (such as artefact processing, environmental sampling, and data management) are frequently under-resourced or overlooked in both academic and commercial contexts. Finally, it examines training in archaeology in general, highlighting how current university curricula and industry placements may leave graduates lacking key field and analytical skills. While each of these strands poses distinct issues, they are intimately connected in practice: robust entry-level training underpins effective PX methods, and stratigraphic analysis is pivotal to advancing both the accuracy and consistency of PX outcomes. While this article intentionally excludes increasingly common advanced digital graphics techniques, such as 3D modelling, photogrammetry, and scanning, the focus is placed on foundational PX skills such as stratigraphic analysis, artefact processing, and data management. These techniques are not directly relevant to the specific challenges addressed here, which concern core PX practices that are often under-resourced or overlooked. However, these digital approaches represent a promising area for future research and development, particularly in the broader context of enhancing PX methodologies. By acknowledging these interdependencies, the article demonstrates how targeted reforms (ranging from curricular updates at universities to coordinated continuing professional development [CPD] programmes) can collectively close skills gaps, enhance the quality of archaeological work, and yield more rigorous interpretations of the past.

2 Single-Context Recording (SCR) and the Harris Matrix as Foundations for UK PX Practice

The earliest principles of PX processing and management were underpinned by methodological advances developed largely outside academia. Two of the most important tools employed to facilitate PX are the SCR system, originally developed by the Museum of London’s Department of Urban Archaeology in the mid-1970s (Spence, 1993, p. 25), and the Harris Matrix, formalised by Edward Harris (Harris, 1975, 1979; Harris et al., 1993). Although Harris famously pinpointed 28 February 1973 as the day he “invented” the Harris Matrix (Brown & Harris, 1993), in reality, the evolution of SCR and matrix-based recording was more gradual and collaborative, refined by various archaeological units and practitioners over time (for a robust discussion of the history and development of this approach to excavation, see Lucas, 2001; Roskams, 2001).

A crucial factor in the wider spread of SCR was the use of paper-based pro forma Context Record Sheets, which effectively encoded key fields of information. These sheets were first described in the Museum of London’s red book, the Archaeological Site Manual (Spence, 1990). Their adoption was enormously influential: numerous commercial archaeology organisations adapted the sheets and accompanying procedures to suit their own circumstances, thereby embedding a relatively standardised approach to excavation, which inevitably influenced PX analysis. Figure 1, for instance, shows a more complex matrix diagram generated from single-context data, where grouping, sub-grouping, and phasing exemplify the interpretative layers that can emerge from robust field recording.

Example of a more complex matrix diagram generated for stratigraphic analysis including grouping, sub-grouping, and phasing of a segment of the site (re-using data from ADS – Crossrail XSM10 https://doi.org/10.5284/1055107).

Despite its effectiveness, the uptake of SCR across the UK was neither uniform nor instantaneous, and it heavily shaped the modern commercial sector: adopting these systems required larger teams of trained personnel to record, manage, and interpret archaeological data effectively. Over time, many organisations adapted or localised the Museum of London pro forma sheets for their own sites; yet the actual depth of knowledge and practice varied. For years, a disconnect persisted between commercial practice and academic instruction, with Greatorex (2004) remarking that SCR was “rarely taught to undergraduates in the field,” even though by the end of the 1990s it had effectively become a practical prerequisite for working in London and many other urban centres. Although many universities now address SCR more explicitly, the discussions undertaken during the Matrix Project (AH/T002093/1) suggest that students’ exposure often remains too shallow to enable them to handle complex grouping and phasing on their own. Moreover, even those who learn the principles of SCR frequently struggle when asked to convert raw data into a coherent, phased framework during PX – thereby exposing a persistent skills gap between academic instruction and commercial practice.

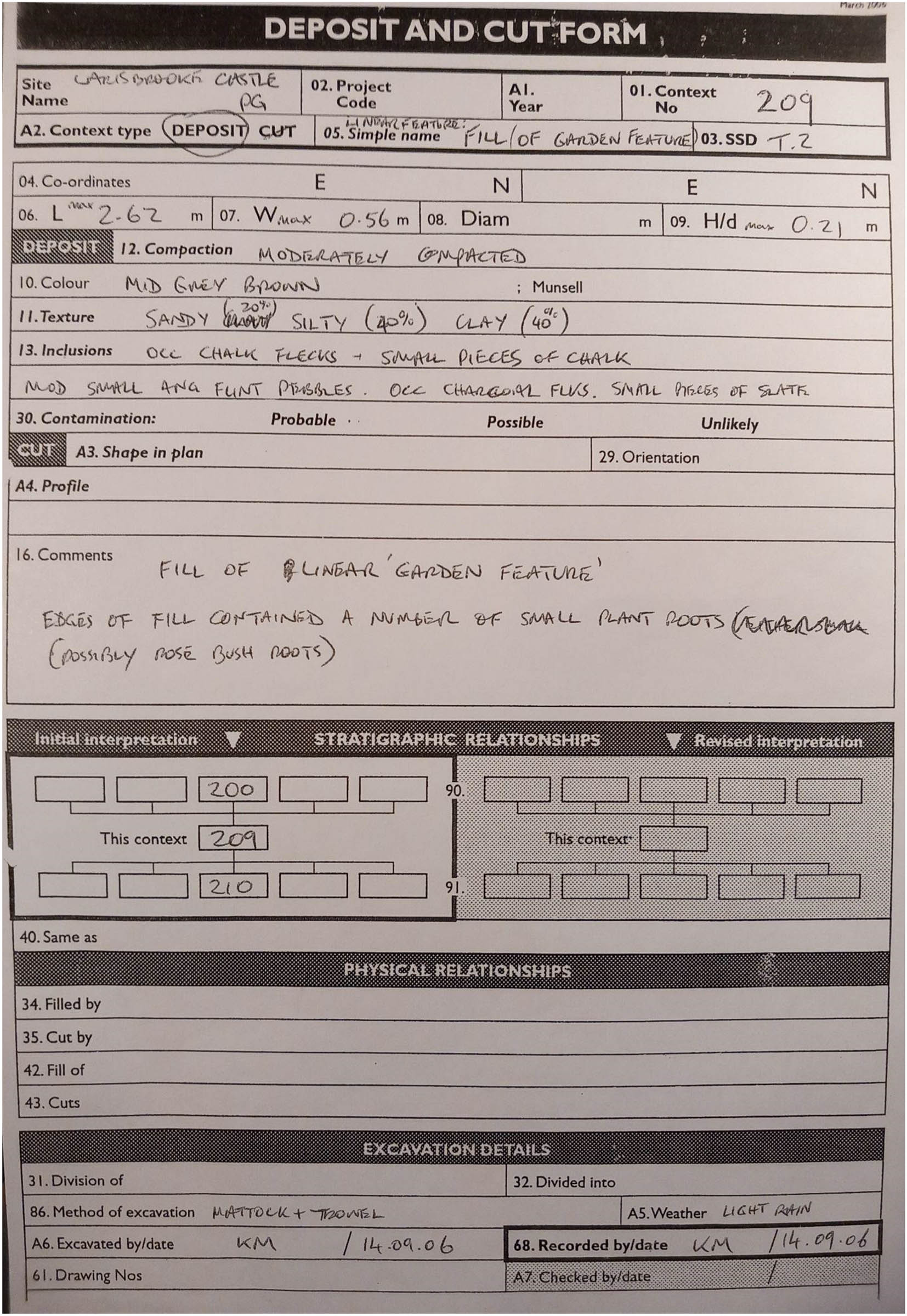

Recognising that SCR underpins the entire PX workflow, a practical means of bridging these gaps may lie in a structured, widely adopted PX Handbook (a modern, more encompassing analogue to the Museum of London’s “red book”). Just as the Context Record Sheets (Figure 2) enabled the widespread take-up of SCR, a clear, step-by-step guide to PX practices (including digital archiving formats, grouping and phasing strategies, and standard workflows) could unify best practice nationwide (see Appendix A, Recommendation 5). It would offer modular resources for universities aiming to strengthen student training, as well as standardised guidelines for commercial units. Crucially, such a handbook could better equip practitioners to move from basic SCR recording to advanced, interpretative stratigraphic analysis, ensuring that collected data can be reliably synthesised for both academic and wider public benefit.

Example of a Context Record Sheet – Historic England Recording Manual.

3 Research Focused upon Stratigraphic Analysis and the Need for Consistent PX Archiving

During the Matrix Project (AH/T002093/1), it was widely acknowledged by the range of professionals we interviewed that stratigraphic analysis is a specialism in its own right. Skilled practitioners need to select from a toolkit of methods when undertaking stratigraphic analysis during PX, depending upon a range of factors including funding, project management research objectives, and, not least, the scale and complexity of the archaeology encountered during the project. “Post-excavation,” if considered as a stage in some universal archaeological process, is largely a construct (concept) of project management practices, in the UK driven by commercial professionalisation and as a practical result of not being able to undertake all parts of the analysis at the time of excavation (Davies, 2017). The PX that archaeological practitioners in UK commercial organisations undertake is primarily a project management stage, following an “Assessment of Potential” after excavation is completed, and principally instigated in the 1990s by the English Heritage Management of Archaeological Projects (MAP2) (Davies, 2017), methodologically based upon accurate and speedy data acquisition in the field and quite far removed from the seasonally re-visited data life-cycle and analysis of research-funded excavations. The doctrine of “preservation by record” as set out in PPG-16 Department of the Environment DoE (1990) and embodied in MAP2 (and to a degree in the MoL Single Context Recording system) was rather predicated on the idea that excavators would be able to objectively record the Stratigraphic Unit (SU) as an “objective observer” with no outside pre-conceptions, so that “extensive interpretational questions of sequence could be delayed until post-excavation” (Spence, 1993, p. 26). However, if it is accepted that the excavators’ role is as a subjective interpreter of the spatiotemporal relationships encountered in the archaeology and embodied in the stratigraphic relationships they record, then it significantly increases the requirement on the excavator to have a greater understanding of how their interpretations may be (re)used in PX and any subsequent synthesis.

Watson (2019) underscores how entrenched empirical methods and time pressures in commercial archaeology hinder methodological innovation; an observation that echoes the inconsistencies in PX practices highlighted by the Matrix Project findings. Such constraints, as Watson argues, not only limit the scope for reflexive fieldwork but also carry profound implications for the robust and flexible PX strategies that our AG2GP-Handbook and its recommendations seek to foster. The Matrix Project, for example originally set out to address issues with the way digital records of PX were either not being archived at all or were very inconsistently archived across different projects and organisations. However, it became clear that the inconsistencies in what data were reaching the archives were partly due to a lack of consistent documented practices for PX across the UK. So, a follow-on project (AH/X006735/1) was devised to develop consistent guidance on the main workflows and methods used in PX stratigraphic analysis (Figure 3) to better support different practitioners undertaking analysis, highlight best practices for consistent FAIR outputs, and thereby improve the potential for synthesis of archaeological information from different projects.

Overview diagram of steps and flow of information in a typical stratigraphic analysis process (see AG2GP-Handbook for more details).

The resulting Archaeologists Guide to Good Practice Handbook for Stratigraphic Analysis reflects that our analytical tools and systems need to be flexible and adaptable and yet broadly consistent and digitally sustainable. The Handbook identifies where more consistent digital outputs of stratigraphic analysis would facilitate greater interoperability and reuse of our site and stratigraphic data to better support different practitioners undertaking analysis and improve the synthesis of archaeological information from different projects. Building upon the AG2GP-Handbook research, this article will highlight the need for structured training for PX skills, especially in stratigraphic analysis which was the focus area of our research, and propose tailored recommendations for both the academic and commercial sectors to address such skills gaps that may be symptomatic of a wider skills deficit across the sector.

The AG2GP-Handbook project has also identified a number of recommendations, to be set out in the Appendix to this article, building upon FAIR and Open data principles, such as developing a code of practice for stratigraphic and chronological data and fostering a community of practice for sustaining up-to-date guidance on PX practices, as well as enabling better international collaboration on digital data management in archaeology. Practical recommendations include the development of best practice guidelines, online modular handbooks, and learning resources, and if adequate resourcing could be found, massive open online courses (MOOCs), international workshops, and CPD and mentoring programmes. These resources could be tailored to meet the specific needs of both the commercial and academic sectors in order to address this skills deficit. The newly launched HE initiative Historic Environment Skills and Careers Action Plan for England (HESCAPE) identifies a shortage of “PX Specialist Skills” and we would propose that stratigraphic analysis is a “specialist PX skill” in its own right. The article emphasises the importance of these initiatives in ensuring consistency and quality in PX practices, ultimately enhancing the archaeological sector’s capacity to preserve heritage, advance methodologies, and contribute valuable insights into human history and prehistory.

The remainder of the article examines a series of gaps or issues in the current approaches to promoting PX skills in academia and professional practice and sets out some proactive steps that universities could take along with professional organisations to address some of these shortcomings. This would mean working with commercial partners in the sector to integrate comprehensive PX training into their curricula or CPD and ideally bridge the gap between academic instruction and professional readiness. There are also a series of resulting recommendations, which are cross-referenced in the text of the article to a numbered list of recommendations in Appendix A.

4 University Education and the Professional Skill Disconnect

The landscape of archaeology education is undergoing significant shifts, particularly in how universities prepare students for the practical demands of the profession. While theoretical knowledge and basic fieldwork skills are foundational, there remains a critical shortfall in training for PX work, such as artefact analysis and report writing. This gap leaves graduates ill-equipped to navigate the complexities of professional archaeology.

Entering the commercial archaeology sector without a degree has become increasingly uncommon (Connolly & Wooldridge, 2022, p. 10). According to Profiling the Profession in 2020 (Aitchison et al., 2021) (the latest PtP report on the 5 years cycle), 28% of the professional archaeologists held a bachelor’s degree as their highest qualification. A further 44% possessed a master’s degree or equivalent, and then 26% had earned a doctorate or post-doctoral qualifications. Remarkably, the proportion of professionals with postgraduate degrees has soared from 31% in 2002 (Aitchison et al., 2021) to an impressive 70% in 2020. This trend underscores the escalating academic demands placed on aspiring archaeologists.

Traditionally, the development of field skills within the private or commercial sector has relied heavily on informal mentoring (see below). Inexperienced staff are paired with seasoned archaeologists, learning through observation and hands-on experience – a process often likened to osmosis. While this method fosters practical learning, it is unstructured and lacks a diverse scope, solid theoretical grounding, and critical self-awareness. Chadwick (2003), Lucas (2001), and Watson (2019) have critiqued this approach, emphasising that many private sector excavators may disengage from broader academic discourse after entering the workforce.

In higher education, Barker et al. (2001), under the Quality Assurance Agency (QAA), identified 17 core skills that archaeology undergraduates should acquire. Among these are crucial practical competencies:

Mastery of core fieldwork techniques: identification, surveying, recording, excavation, and sampling.

Application of laboratory techniques for recording, measurement, analysis, and interpretation of archaeological materials.

Recognition of the archaeological significance of material remains and landscapes.

Interpretation of spatial data by integrating theoretical models with present-day landscapes and excavation findings.

Objective observation and recording of various classes of primary archaeological data.

However, they do not specify clear skill sets that might be explicitly associated with PX analysis. Even so, they do advocate for field investigations and hands-on practical exercises as essential components of the curriculum, complemented by placements and workplace experiences (Barker et al., 2001, p. 59).

However, the actual implementation of these recommendations varies widely across institutions (Aitchison, 2007). Croucher et al. (2008) conducted a comprehensive survey examining perceptions of fieldwork in undergraduate programmes. Their findings revealed a strong consensus: 84% of both students and staff believe that proficiency in practical aspects of archaeology is essential upon graduation, and the same percentage asserts that universities bear the responsibility to prepare students for archaeological careers (Croucher et al., 2008, pp. 24–25).

Despite these insights, a significant gap appears to persist in preparing students for field (and PX) work. Everill’s (2015) review of 44 institutions highlights the inconsistent approaches to fieldwork training:

Access to Fieldwork Opportunities:

Only 34% of the institutions offered principal department fieldwork projects as part of the degree programme. An additional 18% provided choices among various projects, 14% placed students on externally managed projects, and a concerning 2% left students to secure their own opportunities (Everill, 2015, p. 131).

Mandatory Fieldwork Duration:

Requirements ranged dramatically from 2 to 11 weeks over the course of a degree, with 4 or 6 weeks being most common (Everill, 2015, p. 132).

Assessment of Fieldwork:

While 41% of the programmes assessed students’ field performance, a notable 25% did not include any assessment of fieldwork (Everill, 2015, pp. 136–137). Where assessments existed, they often relied on field diaries, reflective written reports, and skills portfolios, rather than direct evaluations of practical competencies.

Prior to this, Phillips et al. (2010) pointed out that some universities expect students to find their own field placements, frequently leading to tensions between the research objectives of projects and the pedagogical needs of students. Geary (2012, p. 126) suggests that it is “completely unreasonable to expect higher education institutions to produce ‘oven ready’ graduate archaeologists complete with all the skills they need to embark upon a professional career.” However, this disconnect results in graduates who are theoretically knowledgeable but lack the practical skills essential for field work (and presumably therefore we can assume PX tasks). Consequently, this suggests that they would surely struggle with artefact analysis, stratigraphic interpretation, and the nuanced demands of professional report writing; skills that are indispensable in both commercial and academic archaeology.

Little has been written about this specific issue in the last decade, but it is worth noting that, building on the idea of “material dimensions” in archaeological teaching, Cobb and Croucher (2020, p. 30) highlight that “archaeology is a discipline grounded explicitly in the material”. They argue that effective pedagogy must extend beyond lecture theatres to include hands-on engagement in labs and the field – where “wet sieve tanks, flots, retents, artefact catalogues, acid free paper, and silica gel all play a role in the learning process” (Cobb and Croucher, 2020). This holistic view underscores the need for equally comprehensive training in PX methods. Whether cleaning and recording finds or interpreting data derived from on-site excavation, students benefit from active, material-based learning that prepares them for the realities of commercial and academic archaeology. In other words, the same “materiality of student learning” (Cobb and Croucher, 2020) that shapes fieldwork also applies to the analytical and reporting phases of excavation. By weaving PX-focused skills more explicitly into the curriculum, universities can reinforce the importance of these interconnected stages and ensure graduates are proficient not only in discovering archaeological evidence but also in interpreting and presenting it effectively.

Nevertheless, explicit and structured training in PX methodologies appears to remain limited across most UK universities. In the UK (in 2025), there are a total of 35 archaeology departments registered as members of University Archaeology UK. We reviewed the published course outlines and module descriptions from the 18 UK universities which offer Chartered Institute for Archaeologists (CIfA)-accredited Archaeology programmes in an effort to identify those programmes which explicitly integrate PX skills into their curricula. For the sake of parity, this review collates data from “standard” BA Archaeology programmes (in Scottish institutions, where no BA is offered then the MSc Archaeology course has been substituted). The review has only considered the core modules offered by the programme, so as to assess the baseline skill set that all graduates will receive. Using this publicly available information, we identified and compared modules that explicitly highlight content relating to PX skills and mapped where competencies relating to post-ex are implicitly delivered (focusing on five core skill areas: Stratigraphy, Chronology and Dating, Artefact/Material Culture Analysis, Fieldwork Report Writing, and Archaeological Publication).

Our investigation asked whether universities feature a module explicitly named for PX, as well as how they incorporate the five core skill areas mentioned above. A small number of universities offer modules whose titles explicitly reference “Post-Excavation” or “Post-Fieldwork” (e.g. the University of Winchester’s “Archaeological Fieldwork and Post-fieldwork Techniques” and Newcastle’s “Fieldwork and Post-Excavation: Archaeology in the UK”). At York, students have access to modules that engage them directly in artefact analysis and the preparation of professional-level reports, ensuring that graduates not only handle data competently but also critically interpret their findings. Here, PX skills are also embedded holistically into the curriculum, providing guided mentorship, specialised equipment, and opportunities to contribute to ongoing research projects. Such embedded approaches demonstrate how structured PX training can be seamlessly woven into degree programmes, rather than treated as optional or peripheral components. At most other institutions, however, these competencies appear under broader “methods,” “theory,” or “fieldwork” modules, rather than a dedicated module labelled as PX.

Nevertheless, all the reviewed programmes (regardless of whether or not they have an explicit “post-excavation” module) do appear to integrate these five skill areas into the standard curriculum of their undergraduate programmes albeit in a more diffuse way. Typically, Year 1 introduces the concepts at an overview level (for instance, how to recognise stratigraphy, the basics of relative vs absolute dating, the fundamentals of artefact classification). Year 2 and Year 3 see these skills may be reinforced and expanded in more specialised modules (e.g. archaeological science, professional practice) and particularly through field schools or excavation placements, where students undertake real-world tasks like processing finds, analysing deposits, and assembling site reports.

The nature of coverage can be briefly characterised:

Stratigraphy is typically taught during field schools and method modules, enabling students to excavate in stratigraphic order, interpret deposit formation, and document contexts with Harris matrices.

Chronology and Dating often comes under “archaeological science” or “methods” modules, offering theoretical and hands-on instruction in radiocarbon dating, dendrochronology, typological/seriation approaches, etc.

Artefact/Material Culture Analysis is core to these degrees, usually delivered through lab-based classes, artefact-handling sessions, and lectures on technology, typology, and style.

Fieldwork Report Writing typically follows the field-school stage, when students produce diaries, context sheets, and interpretive write-ups reflecting real excavated evidence.

Archaeological Publication (formal dissemination) is more often addressed through “professional practice” or “heritage” modules, culminating in an understanding of how excavation data is turned into published academic or “grey literature.”

We acknowledge then that the study found that (whether or not a dedicated “Post-Excavation” module exists by name) these five key skill sets are embedded within all accredited archaeology degrees. Differences between universities lie mainly in their structural approach: some have entire modules labeled for PX, while others weave this instruction into broader method or practice-based courses. In every case, students encounter PX processes, conceptually and practically, from early overviews to advanced placements and final-year dissertations. However, whilst PX tasks are nearly always introduced and practised in some capacity, most institutions do not single out PX training as a dedicated, in-depth module. Instead, the emphasis frequently remains on excavation and site-based data gathering, with systematic artefact analysis, advanced laboratory methods, and formal reporting either folded into optional sessions or assumed to occur “by osmosis.” Although a minority of universities (e.g. York, Winchester, Newcastle, Bournmouth) place stronger, more explicit focus on PX within their curricula, even there coverage may be spread across multiple units rather than fully consolidated.

Consequently, the depth of PX readiness among graduates can vary greatly, reinforcing the very gap that has been identified: students often have decent theoretical grounding and basic excavation experience, but not the robust PX skill set increasingly needed by commercial and research employers. Ultimately, addressing the shortfall in PX-focused training necessitates a multipronged strategy aimed at both curriculum enhancement and institutional reform. Universities could, for example design new modules or dedicated course components that supplement existing theoretical content with hands-on artefact handling workshops, stratigraphic interpretation sessions, and practice-based report-writing exercises. Collaboration with commercial archaeology firms and heritage organisations could facilitate authentic learning experiences, allowing students to grapple with real-world datasets and industry-standard documentation protocols. Offering specialised PX training certifications or micro-credentials within the undergraduate framework might also incentivise students to develop these skills early, simultaneously bolstering their employability profiles (see Appendix A, Recommendations 8, 9, and 10).

However, enriching curricula in this manner often encounters institutional constraints. Departments must negotiate timetables already crowded with lectures delivering baseline disciplinary knowledge and critically engaged theory as well as more typical fieldwork and skills modules. Additional staff and expertise (potentially drawn from the professional archaeology sector) may be required to lead PX skill-building sessions, raising questions about resource allocation. Equally important is the need to shift perceptions: students, faculty, and administrators must recognise that PX work is not a peripheral task, but a core component of archaeological practice deserving equal emphasis throughout the learning trajectory.

Ultimately, increasing student engagement is crucial. Techniques might include establishing PX-focused student societies, peer-led study groups, or research assistantships that support ongoing departmental projects. Encouraging students to reflect on their PX skill development (through portfolios, blogs, or e-learning platforms), as one might assess field skills, can foster a sense of ownership and underline the relevance of these competencies to future careers. Regular feedback loops, wherein students receive mentorship from experienced PX specialists, could reinforce best practice and instil confidence. By creating a vibrant PX learning community and showcasing clear career pathways that hinge on these skills, universities will not only address the existing training gap but also strengthen the professional readiness of their graduates.

In addressing training gaps across the sector, it is also essential to consider the integration of employability into the archaeology curriculum as a strategic solution. Aitchison and Giles (2006) have argued that embedding employability within academic programmes not only enhances students’ learning experiences but also prepares them more effectively for professional practice. By aligning educational outcomes with the competencies required in the commercial sector, academic institutions can produce graduates who are better equipped with both the practical skills and the critical thinking abilities necessary for the diverse demands of modern archaeology. This approach fosters a deeper understanding of professional practices, ethical obligations, and the legislative frameworks governing the field. Embedding employability into the curriculum thus serves as a proactive measure to bridge the gap between academic training and the practical realities of the workforce, ultimately contributing to the development of a more competent, adaptable, and inclusive archaeological profession.

5 Sector-Wide Training Gap and Their Implications

Beyond the academic sector, Bradley et al. (2015) have outlined a timeline of training and development initiatives within the commercial archaeology sector (up to and including 2015), highlighting key milestones and persistent challenges that have shaped the current landscape (Table 1). This timeline provides context to the significant gaps in training that they identify; however, it is interesting to note that there has been no systematic study of this since (at the time of writing) (Table 2).

Summary of explicit “Post-Excavation” module titles and the implicit coverage of key PX skill areas (Stratigraphy, Chronology and Dating, Artefact/Material Culture Analysis, Fieldwork Report Writing, and Archaeological Publication) across CIfA-accredited undergraduate Archaeology programmes

| Institution | Explicit “Post-Excavation” module mention | Stratigraphy | Chronology and dating | Artefact/material culture | Fieldwork report writing | Archaeological publication |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| University of Aberdeen (BA Archaeology) | Yes (e.g. “Professional Archaeology II: Post-Excavation Analysis…”) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| University of Bradford (BSc Archaeology) | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Bournemouth University (BA Archaeology) | Yes (Year 2: “Archaeological Field Skills” explicitly states PX skills) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| University of Bristol (BA Archaeology) | Yes (Year 2: “Post-Excavation Analysis”) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| University of Cambridge (BA Archaeology) | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Canterbury Christ Church (BA Archaeology) | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Cardiff University (BA Archaeology) | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| University of Chester (BA Archaeology) | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| University of Central Lancashire (BSc Archaeology) | Yes (“Introduction to Professional Practice” mentions PX) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Durham University (BA Archaeology) | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| University of Edinburgh (MSc Archaeology) | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| University of Leicester (BA Archaeology) | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Newcastle University (BA Archaeology) | Yes (“ARA2020 Fieldwork and Post-excavation: Archaeology in the UK”) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Queen’s University Belfast (BA Archaeology) | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| University of Reading (BA Archaeology) | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| UCL (BA Archaeology) | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| University of Winchester (BA Archaeology) | Yes (Year 2: “Archaeological Fieldwork and Post-fieldwork Techniques”) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| University of York (BA Archaeology) | Yes (Year 2 core module “Post-Excavation”) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Timeline of training and development in the commercial archaeology sector (compiled from Bradley et al., 2015, pp. 99–103)

| Year | Key events and developments |

|---|---|

| 1997–1998 | Initiation of labour market profiling on a 5-year cycle, consistently identifying skills gaps and shortages in the archaeological workforce |

| 2006 | Increased recognition of the need to synthesise training timelines and address ongoing skills deficiencies became more pronounced within the sector |

| 2007 | Introduction of the national vocational qualification (NVQ) in Archaeological Practice at Levels 3 and 4 aimed to formalise vocational training. Despite its potential, uptake was limited due to costs and scepticism about the new qualification |

| 2014 | The heritage lottery fund’s (HLF) Skills for the Future programme provided significant funding to develop vocational training schemes in archaeology, aiming to address skills shortages and promote capacity building within the sector. While these initiatives offered practical, work-based learning opportunities, they struggled to diversify the workforce, failing to meet HLF targets for increasing ethnic diversity and inclusion of individuals with declared disabilities |

| 2014 | Launch of the CIfA in December after receiving a Royal Charter in June. This marked a significant step towards professionalising the sector, although clear pathways to achieving chartered status for individuals were still lacking |

| 2015 | Publication of the Historic Environment and Cultural Heritage Skills Survey highlighted ongoing demand for skills in the sector despite previous recruitment efforts. The report underscored challenges faced by new entrants, including employer expectations for specialised skills and experience typically gained through volunteering, which hindered diversity |

In their discussion of the development of training in the commercial sector, Bradley et al. (2015) highlight several significant gaps that need to be addressed. These include the absence of formal, structured entry-level professional training in archaeology, leading to an over-reliance on academic qualifications that may not adequately equip individuals with practical skills required in the field. They identify pronounced skills shortages in specific areas such as field archaeology, project management, and digital specialisations, while graduates often lack essential skills like communication, time management, and commercial awareness. The expectation for archaeologists to gain experience through unpaid volunteering creates barriers to diversity and inclusion, resulting in underrepresentation of ethnic minorities and individuals with disabilities. Vocational qualifications like the NVQ are underutilised due to cost and scepticism, indicating a pressing need for structured Apprenticeship programmes and coordinated training initiatives to provide clear career pathways, including routes to chartered status, but formal Apprenticeships have to date failed to gain traction in commercial archaeology and are under-used (Aitchison & Rocks-Macqueen, 2024, p. 28). Additionally, insufficient business and management training, lack of continuous professional development structures, and over-specialisation without adaptability further impede the development of a robust, inclusive training framework within the sector.

Bradley et al. (2015) go on to highlight CIfA’s Workplace Learning Bursaries Scheme and the HLF’s Skills for the Future programme, which aimed to embed a training culture within commercial practice. Similarly, Sutcliffe’s (2014) work on the Community Archaeology Bursaries Project further emphasises the importance of practical, work-based training, and efforts to diversify participation as essential steps in addressing the skills shortages within the archaeology sector (Bradley et al., 2015, p. 62), underscoring the importance of a broad range of archaeological skills (including presumably PX practices) to ensure professionals are prepared for all stages of archaeological work. Related to this, Smith’s (2016) reflections on the challenges of organising CPD sessions for archaeologists in Scotland also echo the training gaps highlighted by Bradley et al. (2015). Her experiences in addressing the overwhelming demand for diverse training needs support an argument for the pressing need for structured, inclusive, and coordinated training programmes within the archaeology sector.

While these projects have sought to systematically address the significant training gaps from the top down, other practical solutions have been proposed to address these challenges. Harward (2015), for instance, introduces the more “bottom up” concept of a “training hour” to be embedded within the working week. This initiative would involve dedicating 1 h each week to focused training and professional development for all site staff, thereby embedding training into daily practice and ensuring continuous skill enhancement. Harward’s approach responds directly to the deficiencies highlighted by Bradley et al. (2015) and others by providing a structured yet flexible framework that can be adapted to include a broad range of skills, including (potentially) analytical skills and PX practices. The BAJR Archaeology Skills Passport (BAJR, 2012) serves to formalise the notion of logging skills development for the purposes of ongoing CPD. However, although it references aspects of PX in its “Secondary” and “Tertiary” Skills categories (e.g. archiving, GIS, data management, reporting), it does not explicitly cover stratigraphic analysis or the construction or phasing of a stratigraphic matrix. There is also no clear guidance on how to group or structure CPD activities explicitly related to PX. Nevertheless, by linking Harward’s “training hour” concept to personal development logs and reinforcing core competencies not otherwise fully addressed in tools like the BAJR Passport, this model promotes shared ownership of training and supports broader skill development across the workforce. This not only has the potential to enhance practical skills, but also fosters a culture of continuous learning and professional development within the sector.

Whilst not much has been published on this in the last decade, our own work, as part of the AHRC-funded Matrix and AG2GP-Handbook projects, which have involved extensive workshoping with representatives across the commercial sector, highlights there still appears to be a broad consensus that there is a critical need for effective training strategies to prepare future archaeologists (Everill et al., 2016). Everill et al. (2016) emphasise that learning is a lifelong commitment starting from early engagement and continuing through university and professional practice. They also stress the need for innovative pedagogical approaches, as proposed by Handley (2016), to enhance learning effectiveness; again echoing Smith’s (2016) experiences with organising CPD sessions. However, none of this literature explicitly mentions the suite of “PX skills” identified above (c.f. the opening section of this article) in their discussion of training gaps within the commercial archaeology sector. It is also interesting to note that CPD is not discussed in some of the more general textbooks on professional pathways (see for example Flatman, 2011). However, these skills remain crucial and might be implicitly encompassed under the identified shortages of “period, area, and artefact specialists” by Smith (2016, p. 103) for example. Ultimately, the lack of structured training programmes and clear career pathways within the commercial arm of the sector is likely to have a long-term impact on PX and analytical practices as much as their “on-site” skills counterpart, and this was evidenced in the discussion and feedback on the AG2GP project. Addressing overall training deficiencies in the sector would involve incorporating PX skills into vocational qualifications and, perhaps more importantly, into coordinated CPD training initiatives, ensuring professionals are prepared for all stages of archaeological work, thereby strengthening the overall competency and inclusivity of the sector.

The HESCAPE identifies priority actions to guide long-term skill development in the sector. It follows the publication of Historic England’s Skills Needs Analysis report, which found the UK is headed towards a skills crisis that threatens the longevity of its heritage if action is not taken. The HESCAPE Action Plan (https://architecturaltechnology.com/resource/historic-environment-skills-and-careers-action-plan-for-england-launched.html) has identified “Post-excavation Specialist Skills (archaeology)” as a key area of sectoral skills that face immediate challenges due to gaps and shortages, and therefore needs prioritised training and development. This article has argued and demonstrated that stratigraphic analysis is a vital specialist PX skill in its own right, which, using all the stratigraphic and chronological information available, plays a pivotal role in drawing together all the other scientific and dating evidence and specialist information contributed during the analysis stage of archaeological projects. We would emphasise the importance that such initiatives should play in ensuring consistency and quality in PX practices, ultimately enhancing the archaeological sector’s capacity to preserve heritage, advance methodologies, and contribute valuable insights into human history and prehistory.

6 CPD and Reliance on Informal Training Methods

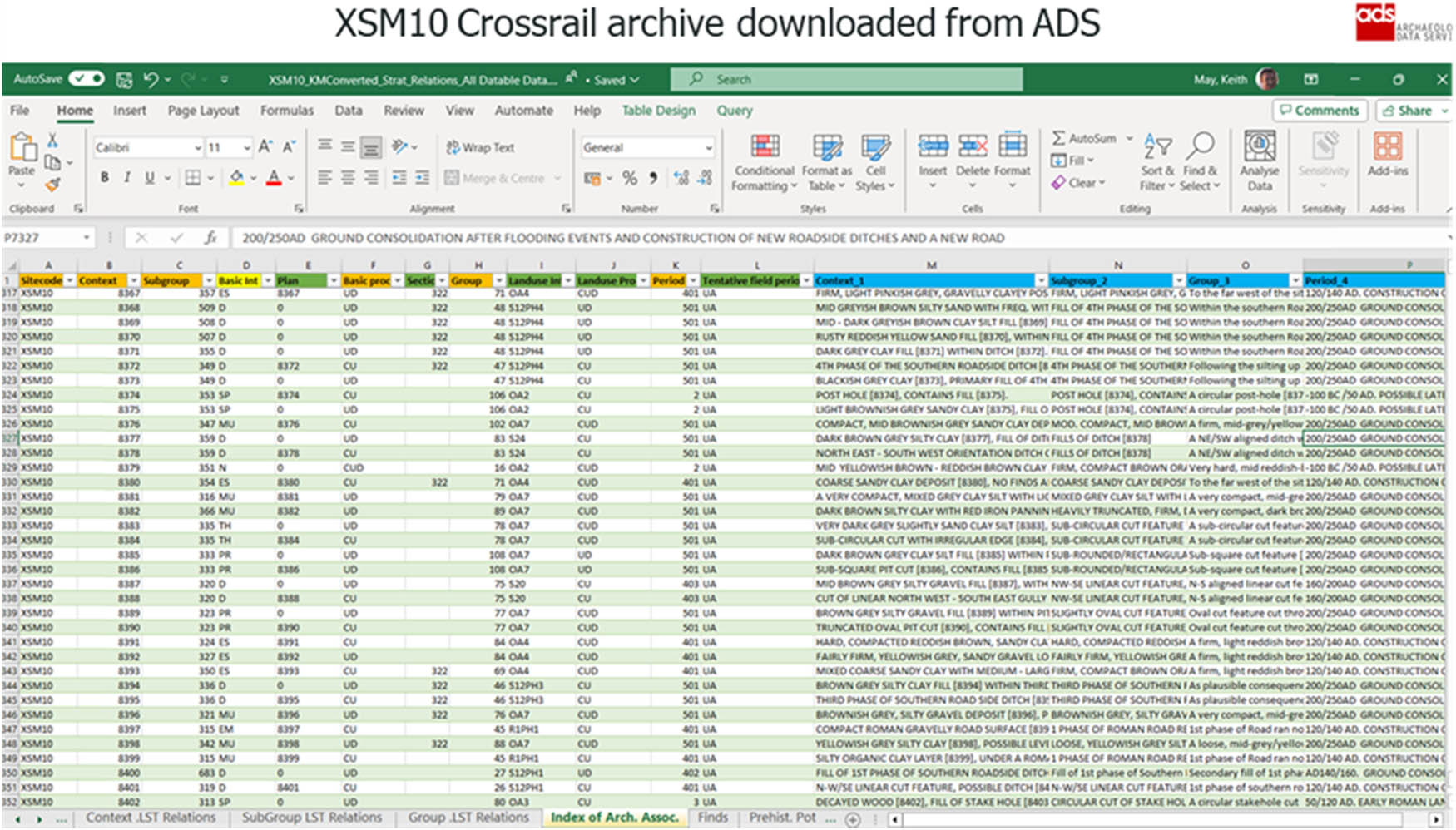

In the commercial sector, which is a significant potential employer for archaeology graduates in the UK, the opportunities for developing PX skills are variable but on the whole limited. The principal method for developing PX skills still seems to be informal on-the-job learning (Davies, 2017; Everill, 2015; Watson 2019) with very limited time and money available for any associated more formal training courses or resources. This seems primarily to be because commercially funded excavation budgets are rarely big enough, or have enough margins built into project budgets, to include provision for formal staff training. If excavation budgets do allow for any training provision, it frequently tends to focus on “on-site” skills – for instance, standard recording methods used in the field (e.g. documenting, drawing and planning of SUs, recording finds, collecting samples) and, where relevant, basic spatial digital recording (e.g. using an EDM or GPS). In comparison, less emphasis is generally placed on PX analysis skills, such as data management, grouping, sub-grouping, and phasing processes that, under typical project management regimes (largely derived from MAP2 (English Heritage 1991) or MoRPHE (Historic England 2015) in the UK), often occur well after the physical excavation is complete. While some organisations do invest in systematic PX training, these opportunities can be limited, especially on developer-led projects primarily focused on meeting immediate site-based objectives. Figure 4 shows an example of a “PX Phasing Index,” downloaded from ADS and converted into a spreadsheet for reuse during the Matrix project, to illustrate the type of analytical output that would benefit from more structured training in PX practices. But what was revealed during the Matrix was that such digital indexes were not commonplace in the deposited digital archives, even though they are essential for making sense of the analytical and interpretative constructs made during PX. Improving PX skills training should lead to improved and FAIRer archives, as well as increasing the quality and understanding of the uses of records made during excavation.

Index of Archaeological Association. Museum of London Archaeology – Example from XSM10 archive data on ADS (IAA.csv converted to spreadsheet) illustrating good practice for grouping, sub-grouping, and phasing data management.

In some cases, site supervisors in the field might pass on tips about how to record better interpretations that could prove useful later in PX, but that will be very dependent upon the type of archaeology encountered on a particular site. For instance, if the site has many deep ditches, then the excavator might be asked to interpret how many “re-cuts” they have found and what sort of primary fills there might be. However, if they are on a site with none of those types of features, then there is no reason for that to happen. Thus, excavators (from which subsequent stratigraphic analysts seem to be expected to emerge, like a rare butterfly from a cocoon) tend to develop excavation and interpretive skills that are very much honed by what type of archaeology they have experienced on the particular sites they have worked on. This level of on-the-job learning experience will be carried through to how people approach PX. Working in PX on a site, or parts of a site, that you have personally excavated is advantageous and may also be enhanced by having worked on other sites nearby with similar or related stratigraphy (especially in an urban scenario).

But that does not always happen and is perhaps less common in archaeological organisations working in more rural and dispersed localities. Increasingly in the commercial sector, sites are not written up (analysed in PX) by the people who excavated on them. With some major projects, the PX stage can be advertised and funded as a separate project stage, where a consortium takes on the PX project collectively so people may be working on the records of sites excavated by a different organisation.

When undertaking PX for the first time, a person will be very reliant upon the experiences of the PX manager who is overseeing their PX project. Again, the levels of interpretative skills will be a by-product of that particular PX-manager’s experiences on sites that relate to the one being analysed and written up. A broad listing of relevant PX skills would be useful here, e.g. stratigraphic analysis; specialist finds identification and dating; contracting scientific dating specialists; geotechnical analysis; research data management; and report writing, although it is notable that CIfA do not have a Competence Matrix setting out the skills expected for PX managers.

The National Occupational Standard CCSAPAC8, entitled “Undertake analysis and interpretation of archaeological material and data” (Creative & Cultural Skills, 2012), explicitly defines the performance criteria, knowledge, and understanding required to undertake analysis and interpretation of archaeological material and data. Covering everything from confirming technical and ethical standards (P2, K3) to accurately recording, storing, and reporting findings (P14–P19, K10, K14–K16), CCSAPAC8 demonstrates that advanced interpretative tasks (so central to PX work) already have a recognised skills framework. Yet feedback from both commercial employers and academic tutors suggests that many early-career archaeologists struggle to meet these exacting standards. This gap reinforces the urgent need for systematic PX training programmes, more robust CPD provision, and shared resources (e.g. a PX Handbook) to help practitioners acquire, refine, and apply the skills laid out in CCSAPAC8.

Sharing skills already in limited supply would be a positive way forward, and even allowing for the competitive nature of commercial project funding, there would be considerable cost-benefit advantages in being able to share PX skills across organisational boundaries, for at least the following reasons:

Increasing consistency in practice, outputs, and resulting publications.

Sharing archaeological (and geotechnical, etc.) expertise within identified geographic areas.

Increasing knowledge outputs and skills from shared working experiences.

Sharing PX skills while distilling, and ideally documenting, good practice.

Sharing mentoring schemes between different organisations working on similar or differing archaeologies.

In day-to-day practice, some of this may happen informally as the number of PX managers in archaeology is not huge, and they do talk to each other; the authors estimate that between 60 and 100 people working in UK commercial archaeology in 2024 manage or are closely involved in supervising PX projects, and many of these people may have moved and thereby shared experiences informally between organisations and projects over time. Nevertheless, a more structured approach to designing and sharing formal and consistent PX-based training programmes, with some provisions for mentoring, across organisations would be beneficial, both in building a better archaeological knowledge base, and also in propagating shared good practice within the profession (see Appendix A, Recommendations 2, 3, and 5).

7 Retention Issues and the Erosion of Institutional Knowledge

A persistent set of interconnected issues continues to weaken staff retention in commercial archaeology, undermining the transmission of essential expertise and, in turn, complicating efforts to improve training. These problems encompass inadequate career progression opportunities, the perception that archaeological work is undervalued, and the narrowing of experienced talent pools through compressed salary structures. Collectively, they exacerbate the erosion of institutional knowledge, leaving newer practitioners without the guidance necessary to develop advanced PX skills. In the sections that follow, we examine how each of these factors compounds the overall challenge of building and maintaining a skilled workforce, arguing that more structured provisions for PX training and CPD are vital to addressing them.

8 Poor Career Development Opportunities

Currently, the sector as a whole has stopped growing, and companies are finding it difficult to hire (State of the Archaeological Market 2023 https://famearchaeology.co.uk/state-of-the-archaeological-market-2023/, Sector Growth, p. 15; Perceptions, pp. 32–33). Could it be one reason that the sector is losing more people after a few years in the profession is because they are not getting suitable opportunities to hone and extend their excavation skills and enhance their careers with CPD that encompasses the challenges of PX and writing more interpretively about the sites they keep being asked to excavate?

9 An Undervalued Profession and Relative Poor Pay

There is an increasing perception amongst archaeological professionals that their jobs are undervalued, when measured in terms of economic rewards. Archaeologists in commercial organisations report increasing economic pressures due to poor pay and conditions, along with other issues around job security, peripatetic lifestyles, and the exponential additional responsibilities of middle management jobs in archaeology which are not remunerated as well as one sees elsewhere in the private sector. The recent BAJR “Poverty Impact Report” largely reflects these views, although there are also some improvements reported: “although individual archaeologists are being pushed past the poverty line, there are signs of potential, as in 2022 just over 35% felt confident that they could continue in archaeology, while this has risen to 46% in this 2024 survey. This is due to a concerted effort by many employers to help staff as best they can within a challenging time” (Stanton-Greenwood et al., 2024).

The most recently produced comprehensive review of salaries in UK archaeology (Aitchison et al., 2021) identified that on average (mean figures), archaeologists earned £30,183 per annum in 2019–2020 and the median archaeological salary was £28,500 (50% of the archaeologists earned more than this, 50% earned less). Low pay is another factor frequently cited as being a reason that adversely influences staff retention in archaeology, and so has led to the loss of experienced practitioners (e.g. CIfA, 2024a; Flatman, 2011, p. 30; RESCUE, 2024). However, this could be an issue of perceived low pay rather than absolute low pay. By comparison, the average for all UK full‐time workers was £29,000 – so, overall, the average archaeological salary was 104% of the UK national average. The UK median salary (for all occupations) was £25,780, and so by this measure, archaeologists were, overall, being paid 10% more than the typical salary taken home across the entire UK workforce. It is relevant to note that for professional, scientific, and technical activities the median salary was £32,533 (Aitchison et al., 2021, Table 2.17.2). This is relevant because “Most current students of archaeology come from a professional social background. Their aspirations for their own social lives have been framed in such a background, and their expectations of a future lifestyle are mostly nurtured by what a professional background can afford” (Sinclair, 2015, p. 222). The biggest factor with remuneration may therefore be not that archaeologists are in very poor-paying jobs, especially as wages across many professions have not kept pace with recent inflation and the “cost of living.”

Rather then, recent reviews and stakeholder feedback by commercial organisations suggest a compressed salary structure in commercial archaeology, where most staff earn above a moderate baseline, but only a small proportion receive significantly higher pay. As a result, there is limited potential for salaries to rise substantially upon promotion. These organisations often report that as employees move into middle or senior management, an increasing share of their responsibilities shifts to administration rather than fee-earning activities, effectively restricting opportunities for higher remuneration. Equivalent managerial roles in other sectors may offer considerably larger salaries, which may also help explain why experienced managers in archaeology sometimes choose to leave the profession.

10 Erosion of Institutional Knowledge

Regardless of the reasons, whether feeling undervalued; lack of career progression; or basic economic necessities; individuals do leave archaeology without necessarily having passed on their expertise and knowledge to their colleagues, resulting in organisational amnesia and loss of competence. Compounding this issue is the widespread perception (across both academic and commercial spheres) that PX is the exclusive domain of a select few “experts,” with the relevant experience, having “done their time in the field” and “pulled up through the ranks,” as it were. As a result, excavators encounter limited formal avenues and career paths for developing these specialised skills, further exacerbating the problem of knowledge retention.

Ultimately, high staff turnover weakens the potential for effective PX analysis by depleting the pool of experienced mentors able to transmit advanced interpretative skills. This erosion of institutional knowledge has direct consequences for professional development: without seasoned practitioners to guide novices, the consistent application of PX workflows becomes harder to sustain. In turn, this highlights the need for structured training schemes and formalised resources (such as a sector-wide PX Handbook) to capture best practice, mitigate the effects of staff churn, and ensure continuity in how archaeological data are handled and interpreted. Embedding such tools within ongoing CPD not only strengthens skills retention but also helps cement PX analysis as a core dimension of professional progression.

11 Opportunities for Implementing PX Training and Good Practice in the Commercial Sector

All major commercial projects recognise that there will be learning outcomes from doing the work, both in terms of people learning on the job and as learning legacies that can then be used to raise sectoral competency bars and to be taken into account in future major projects.

Infrastructure megaprojects in the UK, such as the Channel Tunnel Rail Link (Foreman, 2018), Heathrow Terminal 5 Framework Archaeology (2006), and Crossrail Museum of London Archaeology (2019), have all involved considerable numbers of archaeological practitioners and resulted in high-quality records and PX interpretation. These have led to the publication of models of best practices (Carver, 2003, 2013) that have then allowed for subsequent emulation within archaeological heritage management. The lessons learned from these megaprojects have also contributed to the development of best practice guidance for the construction sector that is commissioning archaeological investigation and PX analysis, specifically the CIRIA Archaeology and Construction: good practice guidance, which makes clear to client-side what the context and activities involved in the post-ex work that they will be commissioning involves (Nixon et al., 2021, pp. 44–45).

At the time of writing, the contract to deliver the PX services for High Speed 2 (HS2), the largest ever archaeological project in the UK (where fieldwork was undertaken along the line of a new high-speed rail line between London and Birmingham), had recently been awarded to ACCESS+, a consortium led by Headland Archaeology (HS2 Ltd, 2024). As this had been so recently awarded, work had not yet begun at the time of writing, but it is hoped that this will have further transformatory results for professional practice in UK archaeology.

There is great importance attached, both within archaeology and by archaeology’s clients, to seeing that work is professionally accredited, and so the quality of the work has been externally benchmarked. The clear route to professional accreditation and standardisation in UK archaeology would be through collaboration with the CIfA, as the professional association for the sector. In addition to delivering accreditation, CIfA has ambitions to become a significant provider of post-higher education professional training for archaeologists. Following the 2024 appointment of a new CEO (Nathan Baker), CIfA

has adopted a new three-year plan for the Institute, led by our incoming CEO. One pillar of this will be a new focus on training and learning programmes in business. As the sector improves the way it does business, it will attract more high value work and be better placed to pass on the return as salaries. This is a long-term strategy, but improving salaries depends on the sector bringing in more money per head. (CIfA, 2024b)

CIfA prepares competency matrices for archaeological work, but at the time of writing had not prepared such a tool for PX management. This is considered to be because these are largely prepared by the members of CIfA’s Special Interest Groups (SIGs), and there is not currently a CIfA SIG for PX practice. Would some form of Community of Practice and/or related SIG for people managing and closely involved in PX and analysis projects be viable? (see Appendix A, Recommendation 1).

12 Proposed Training and CPD Resources for PX

Given these identified gaps and the pressing need for comprehensive training that encompasses both excavation and PX skills. Addressing the overall training deficiencies within the sector necessitates a multifaceted approach that integrates PX skills into vocational qualifications and emphasises coordinated CPD initiatives. In view of these identified gaps, the following section proposes the development of structured programmes and resources for PX skills aimed at bridging the identified training gaps and highlights some recommendations for their implementation (see Appendix A for all recommendations).

13 Best Practice Guidelines

Developing and implementing standardised best practice guidelines across the sector is fundamental to ensuring quality and consistency in archaeological practices. These guidelines would serve as an authoritative framework outlining essential procedures for both fieldwork and PX processes. By adhering to a unified set of standards, professionals can minimise discrepancies and uphold the integrity of archaeological work across different projects and organisations. The CIfA has established professional standards and guidance documents that provide benchmarks for archaeological practice (CIfA, n.d.). However, there is a notable absence of detailed guidelines specifically addressing PX practices and associated skills. Creating comprehensive guidelines in this area would fill a critical gap, providing clear expectations for training and professional conduct (see Appendix A, Recommendation 2).

14 Modular Handbook

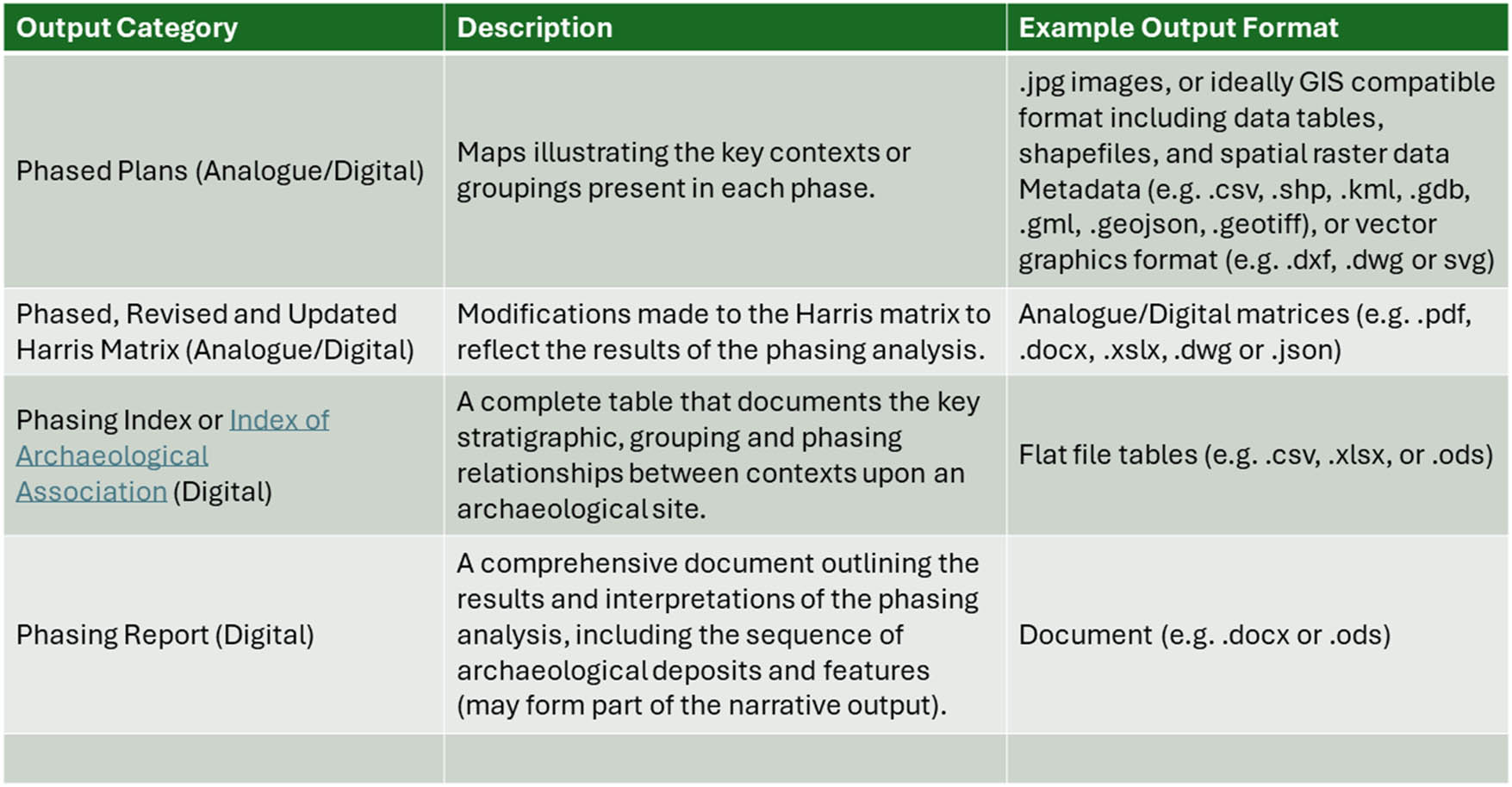

The development of a modular online handbook, building on the Archaeologist’s Guide to Good Practice (AG2GP) (Historic England et al., 2024) work, could offer a more comprehensive and flexible resource designed to cater to varying levels of expertise within the archaeological community. By organising content into distinct modules, individuals can tailor their learning to specific areas of interest or need, whether they are newcomers seeking foundational knowledge or experienced professionals aiming to update their skills. In this case, the AG2GP offers specific guidance on the practice of stratigraphic analysis, however, a modular handbook on PX skills could also include sections on artefact processing, environmental sampling, data management, and report writing. Each module would provide in-depth information, practical examples such as examples of good practice digital outputs recommended for archiving (Figure 5, Outputs for Phasing), e.g. see all recommended outputs on AG2GP-Handbook, and case studies, enabling users to develop proficiency in targeted areas. Such a resource could be made available in both digital and print-on-demand formats, enhancing accessibility and convenience. This sort of modular approach could be used to facilitate continuous learning and can be easily integrated into academic curricula or professional development programmes alike (see Appendix A, Recommendations 2 and 3).

Recommended example outputs from PX stratigraphic analysis Phasing with preferred digital formats and link to a digital example of IAA.csv on ADS – see AG2GP-Handbook – Phasing.

15 Massive Open Online Courses

MOOCs represent a valuable opportunity to deliver structured, widely accessible training in PX practices – a pressing need that goes beyond typical field-based or introductory archaeology modules. A MOOC dedicated to PX skills could include step-by-step guides to grouping, sub-grouping, and phasing, demonstrations of best-practice data management and archiving, and report-writing strategies aimed at both specialist publication and grey literature. Practical video tutorials might walk participants through creating robust digital archives or using a Harris Matrix to organise stratigraphic data, thus bridging the gap between basic field records and final interpretative synthesis.

Other archaeology-themed MOOCs, for example the “Archaeology of Portus: Exploring the Lost Harbour of Ancient Rome” offered by the University of Southampton, UK (University of Southampton, 2018), “Advanced Archaeological Remote Sensing: Site Prospection, Landscape Archaeology and Heritage Protection in the Middle East and North Africa” offered by Durham University (Durham University, 2018), UK, and “Exploring Stone Age Archaeology: The Mysteries of Star Carr” offered by the University of York (University of York, 2019), attracted thousands of participants worldwide, demonstrating that substantial global audiences can be reached Although these successful offerings do not substantially address specialist PX content, they illustrate the potential reach, accessibility, and flexibility of online learning. Building on their model, a dedicated PX-focused MOOC could incorporate short video lectures, interactive quizzes, and digital forums where participants collaboratively tackle real-world data sets with expert guidance. Such a format would allow students, early-career excavators, or mid-career professionals to develop more advanced interpretative skills at their own pace, freeing commercial units from having to provide all training on-site and enabling universities to extend their teaching beyond the campus.

Ultimately, while MOOCs can help fill more general archaeology training gaps, their greatest benefit for the sector lies in targeted PX modules. Such resources would not only support CPD but also enhance consistency and rigour in how PX data are handled, interpreted, and reported across the field (see Appendix A, Recommendation 6).

16 Workshops and Day Schools

Organising workshops and day schools provides opportunities for intensive, hands-on learning experiences essential for mastering practical skills. These short-term training sessions can focus on specific topics, allowing participants to gain practical experience under the guidance of experts. Workshops can be tailored to address particular needs within the sector, such as advanced analytical techniques or the use of specialised equipment. Again, these could be tailored to address specific training gaps and have the benefit of providing immersive training that complements theoretical knowledge and enhances practical competencies. Organisations such as CIfA and the Council for British Archaeology already frequently host workshops addressing various topics, facilitating skill enhancement and professional networking, suggesting not only that there is infrastructure, but impetus and uptake of this sort of training within the sector already (see Appendix A, Recommendation 7).

17 Teaching Resources

Developing standardised teaching resources is crucial for educators and trainers to deliver consistent, high-quality instruction. These resources might include lesson plans, practical exercises, case studies, and multimedia content, all aligned with industry standards and best practices. Standardisation would ensure that learners receive a cohesive educational experience, regardless of the instructor or institution.

In archaeology, such resources could support university programmes, vocational training, and professional development courses and could be designed and implemented by collaboration between industry and the education sector by bodies such as CIfA, Federation of Archaeological Managers and Employers (FAME), and UAUK (see Appendix A, Recommendations 6, 7, and 8).

18 Mentoring Programmes and Apprenticeships

Formalised mentoring programmes and Apprenticeships offer structured, on-the-job training that bridges the gap between theoretical knowledge and practical application. By pairing less experienced individuals with seasoned professionals, these programmes facilitate the transfer of tacit knowledge, skills, and professional values. Apprenticeships, in particular, provide comprehensive training while contributing to active projects.

The Historic England Heritage Apprenticeships initiative is an example of how Apprenticeships can be structured to provide valuable experience and address skills shortages, but there is still more work to be done to get such Apprenticeships implemented effectively by a wider range of archaeological employers (Aitchison & Rocks-Macqueen, 2024, p. 28). In terms of chargeable hours for commercial organisations, it is junior field staff that can be the most valuable members of the archaeological workforce. If they are only employed to work on specific projects, then 100% of their time can be charged to clients. But if Apprentices’ hours cannot be charged to clients, then they are a direct cost to the employer, not a revenue-generating asset.

As is clear from less formal training that is traditionally practised in the sector, mentorships not only enhance technical skills but also support career development and professional integration. In addition, some tailored “Training for the Trainers” would increase the numbers with communication and mentoring skills to pass on their experience in the best ways to others. Establishing sector-wide mentoring programmes would promote inclusivity, ensure quality and standards are upheld, which respect ethical and professional boundaries that cannot be monitored in less formal or ad hoc arrangements, thus promoting equity across the discipline (see Appendix A, Recommendation 5).

19 Community of Practice for Post-Excavation (CoP-PX)

A potential solution around which many of the proposed resources listed above, and elsewhere in recommendations, could consolidate would be to foster and develop suitable resources for a Community of Practice (CoP) centred around PX and based in the professional side of the sector (e.g. incorporating CIfA Toolkits), but with appropriate linkages to and from academic resources. Some aspects of this may well already exist in separate professional groupings. But there does not seem to be acknowledgement of the role of PX managers in bringing PX projects to fruition. It has been noted that CIfA does not have a Competency Matrix for PX managers (see Appendix A, Recommendation 4).

One starting point might be to hold some pan-UK Focus Groups and workshops for PX managers, building on the AG2GP-Handbook approach, to gauge the appetite along with what user requirements and resources might be needed for a “PX-CoP.” The intention of such a “PX-CoP” would be to coordinate with existing resources – such as CIfA Toolkits, Dig Digital, & ADS G2GP – and assess the necessary support from organisations such as FAME, CIfA, and UAUK to make such a CoP sustainable. A coherent approach to implementing recommendations such as these aligns with the overarching goal of enhancing professional development within archaeology. By integrating such initiatives, the sector can address the pressing need for comprehensive training encompassing both excavation and PX skills, as identified most recently by Sadie Watson:

It would be preferable to also link excavation and analysis at the earliest opportunity in the process, an objective attempted by Framework Archaeology yet not pursued by subsequent projects. This objective requires excavation to be intellectualised through the research-led adaptation of processes during fieldwork and the provision of specialists and processing systems throughout project design and excavation. (Watson, 2019, p. 1648)

This would ultimately strengthen the overall competency and sustainability of the profession and help retain talent by providing clear pathways for progression within the profession (see Appendix A, Recommendation 1).

20 Conclusion

The evidence and discussions presented throughout this article underline the urgent need to develop more systematic, comprehensive, and accessible training resources for PX skills within archaeology. While theoretical instruction and basic fieldwork competencies have long formed the bedrock of archaeological education, the pivotal stage of PX analysis (comprising stratigraphic interpretation, artefact processing, specialist finds analysis, robust data management, and clear reporting) remains comparatively under-emphasised in both academic curricula and professional development programmes. Initiatives such as the AG2GP-Handbook have shown that PX resources can be developed by cooperative efforts and shared effectively online. Yet there remain persistent gaps between aspiration and implementation, so further work is still needed to “bed in” such initiatives and sustain and keep such online resources up to date with evolving and innovative methods.

A key challenge lies in balancing theoretical knowledge with the practical skills required for PX work. University programmes have historically provided strong intellectual foundations, but ought to be adapting to ensure that graduates can transform raw excavation data into meaningful syntheses of past societies. Especially as the way PX is handled commercially can change, with current trends towards dedicated PX teams taking on infrastructure projects or PX work being tendered out to parties who were not involved in the initial evaluation or excavation phases of a project. Accessible and inclusive training models, whether delivered through formal university modules, CPD courses, MOOCs, or hands-on workshops, have the potential to attract a more diverse audience. They can also accommodate varied learning styles and professional backgrounds, thus broadening engagement with these skill-sets and fostering greater equity within the sector. Future-proofing these training resources is equally crucial. As archaeological methods and technologies evolve, guidance on best practice must be kept current. Ensuring regular updates to modular, online, PX training materials, and processes (through ongoing consultation with commercial practitioners, academic experts, and professional bodies) will help maintain their relevance and align them with the latest methodological and technical advances.

Although CIfA has developed a range of widely used professional standards, the lack of a formalised competency matrix covering the skills and accreditation of PX-focused professionals serves to emphasise that the learning pathways for PX skills are still rather disparate. Perhaps, establishing a dedicated SIG at CIfA along with a wider Community of Practice (CoP-PX) dedicated to PX work could make useful steps towards redressing this imbalance. Such groups could drive the creation of a competency matrix that recognises the distinct skill sets, knowledge bases, and professional responsibilities that characterise PX management. This, in turn, would foster clearer career pathways and professional benchmarks, supporting practitioners at all stages of their development.

There seem to be some clear opportunities for action. Academic institutions, commercial firms, sector bodies such as CIfA and FAME, and research-funded initiatives like the AG2GP-Handbook need to coordinate to translate good intentions into tangible changes. By developing structured course modules; offering relevant CPD opportunities; actively promoting mentorship and take-up of Apprenticeship programmes; and establishing and promoting best practice for PX analysis including archiving the resulting digital products; the sector can better nurture the interpretive, analytical and synthesising capabilities that are vital for understanding and interpreting the archaeological record. At the same time, systematically embedding the evaluation and enhancement of PX skills within accreditation frameworks will raise professional standards and improve quality across the board. Evaluating the effectiveness of such measures would probably require a longitudinal study.