Assessing the Development in Open Access Publishing in Archaeology: A Case Study From Norway

-

Steinar Solheim

, Isak Roalkvam

, Marie Ødegaard

, Kjetil Loftsgarden

, Hege Damlien

, Svein Vatsvåg Nielsen

, Anette Sand-Eriksen

, Marte Spangen

and Ingrid Ystgaard

Abstract

This article examines open access (OA) publishing within archaeology by using Norway as a case study. The authors present data on research publications (n = 1,517) produced by archaeologists at Norwegian universities between 2010 and 2021 and classified according to their OA status. The aim is to analyze trends in OA publishing during this period and assess how it aligns with official policies and initiatives from lawmakers, funders, and institutions. The findings indicate a growing proportion of OA publications, with scientific journals emerging as the primary publishing platform during the period. The archaeological publications are also compared with other academic sectors, and the study reveals that the field of archaeology is progressing toward OA at a fast rate compared to the broader humanities sector but slower compared to other academic sectors. The authors suggest that the increasing prevalence of OA publications can primarily be attributed to national and institutional guidelines, rather than changes in researcher behavior, although this works in tandem.

1 Introduction

Most archaeological excavations and research are publicly funded. The results of these projects are typically published in books or journals that require subscription fees or charge authors at the time of publication. This has long been, and continues to be, the most common way to disseminate research not only in archaeology but across all academic disciplines. In response to the limitations of the subscription-based model of scholarly publishing and propelled by technological advancements offered by the internet, open access (OA) introduces a new model for scholarly publishing (Severin et al., 2020). OA publishing exists in various forms, and since 2000, there has been a gradual shift in scholarly publishing toward making research results increasingly available as OA, allowing readers to access content without subscription fees (Tennant et al., 2016). The rationale behind OA is to enhance the utilization of research within academia and beyond, by making it freely accessible. As a result, it has now become a fundamental component of science policy.

While there is a gradual development in OA publishing across the academic sector, differences in publishing strategies and traditions exist between disciplines. OA publication, as well as the publication of research data and software protocols, has stronger traditions in medicine and natural sciences compared to social sciences and humanities, including archaeology. This seems to be slowly changing within humanistic disciplines, as demonstrated in bibliometric studies (Severin et al., 2020). One could hypothesize that archaeology is following the general trend toward increased OA publishing within the social sciences and humanities; however, this is unclear and not yet supported by empirical data. Although there are numerous studies focusing on publication practices within archaeology, such as research topics (Jørgensen, 2015), authorship and gender (Heath-Stout, 2020; Hutson et al., 2023), and choices in publishing strategy (Beck et al., 2021), the development of OA publishing within the discipline has not been specifically addressed.

Against this backdrop and considering the growing trend of OA within scientific publishing, it is crucial to investigate publication strategies within archaeology more closely. Does archaeology align with the general trend in OA publishing as seen in other academic disciplines? If not, what are the underlying reasons? Is a potential divergence due to choices or structural issues? Archaeology is often engaged in topics relevant to the public, such as identity politics, repatriation, indigenous archaeology, and critical heritage studies, but do we truly enable the public to access research results and participate in discussions if a research output is not openly available (Marwick, 2020)? If articles are published in non-OA channels, do they become commodities accessible only to a privileged few (e.g., Ribeiro & Giamakis, 2023)? By focusing on how archaeologists engage with open science practices, particularly OA, we can foster greater awareness among archaeologists about how we publish and disseminate research results and data.

In this article, we aim to explore how archaeologists decide to publish their research results, using research publications produced by archaeologists employed at Norwegian universities as a case study. We focus on Gold OA (freely available under an open license), Green OA (available as a pre- or post-print), and non-OA publishing between 2010 and 2021. This period covers years before and after significant official and institutional initiatives aimed at promoting open research in Norway. Our objectives are (a) to determine whether there was a change in OA publication during these years and (b) to assess how these changes correlate with such initiatives.

Although there are variations in publication strategies and national guidelines across Europe and beyond, we propose that Norway serves as a useful example of how archaeologists in high-income countries choose to disseminate their research. In Norway, as in other high-income countries like Sweden, Denmark, the UK, and Germany, the government, research funders, and institutions strongly endorse the principles of OA, expecting researchers to adhere to open science practices by making their research results openly available. Researchers in Norway benefit from various national and institutional measures and incentives that support OA publishing, including institutional research archives, rights retention agreements, and transformative agreements such as publish-and-read schemes. Despite this support, we observe that archaeologists often opt not to publish their research results as OA, even when the benefits of OA publishing are clear for individual researchers (Huang et al., 2024).

To our knowledge, this article is one of the few studies focusing specifically on archaeologists’ publication practices and their relationship with OA publishing. While we rely on data exclusively from Norway, we believe our results will help highlight the importance of publishing practices and may inspire similar and comparative studies in other regions.

2 A Brief Background to OA Publishing

In the ideal publishing landscape, all researchers have equal possibilities to publish and read peer-reviewed research. This is far from the present situation where a range of different stakeholders have interests in how research results should be made available (Björk, 2017). Put broadly, there are two avenues for how researchers disseminate research results: either through OA or non-OA publication platforms. There are different ways of publishing OA: Diamond, Gold, Green, and so-called Hybrid journals. This makes it difficult to navigate between different definitions, regulations, and incentives (Table 1), but basically, OA makes peer-reviewed research results immediately freely available to everyone online without any paywalls or subscription fees. Conversely, non-OA papers are only available at the cost of a subscription or paper fee limiting access for those without access to academic libraries or financial resources.

Definitions of different terms and abbreviations used throughout the text

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Open access | Open access to research publications |

| Diamond open access | Journals’ costs covered by sources other than subscriptions or publication fees |

| Gold open access | Publishing scientific articles in online OA journals free for everyone to read and that allows reuse, storage, indexing, searching, distribution, etc. |

| Green open access | Research works made available in open electronic archives |

| Hybrid open access | Journals where authors can choose to pay a publication fee (or use the institution’s publishing quota in a license agreement) to make their article openly accessible, while other parts of the same journal require a subscription |

| Publish and read agreement (PAR), Transformative agreement | A type of agreement that allows researchers at an institution participating in the agreement to publish openly at no cost to the researcher. This type of agreement also grants the institution’s employees access to the portion of the journal portfolio that is behind a paywall |

| Article processing charges (APC) | A fee charged by a publisher to make a research contribution openly accessible. The work is published either as Gold open access or Hybrid open access. Several research institutions in Norway have allocated funds in publication funds to cover publication fees. The fee can also be paid by the author’s institution in other ways (e.g., where there is a publish and read agreement), other research funders, or by the author themselves |

| Rights retention agreements/strategy, institutional rights retention policy (IRRS) | A strategy that involves what is published being deposited in open institutional archives. Researchers are free to own, use, control, and archive their own research |

| Cristin – current research information system in Norway | Cristin is a common system for registering and reporting of research activities and results. It is used by member institutions in the research institute sector, the higher education sector and health trusts |

| NPI – Norwegian publication indicator | The purpose of NPI is to promote high-quality research and provide an overview of and insight into research activity |

| Sikt – Norwegian agency for shared services in education and research | Sikt is a collaborative body that develops, purchases, and delivers products and services designed to enhance education and research experiences. SIKT offers a common infrastructure and joint services for the knowledge sector |

| NVI – The Norwegian science index | The Norwegian Science Index is an annual report on scientific results from education and research. The result of this reporting is part of the funding basis for some institutions |

| DOAJ - The directory of open-access journals | The DOAJ is a register of OA journals |

| Scopus | Scopus is a comprehensive abstract and citation database that covers a wide range of disciplines, including science, technology, medicine, social sciences, and arts and humanities |

The move toward full OA can be understood as an (ideological) critique of the present publication system as well as to ensure that publicly funded research results are made available and benefit researchers and the public alike. Since 2000, several important initiatives toward OA have been proposed by legislators and funders who, along with most researchers, agree on the idea that research results and research data should be made freely available in a move to make the scientific process more transparent, inclusive, and democratic. Despite this, many researchers choose non-OA publications in subscription journals (Haug, 2019), and consequently, the progress toward open research has moved slowly. There are several reasons for this, such as habitual behavior in publishing (Moksness et al., 2020), perceived quality of OA journals (Moksness & Olsen, 2020; O’Hanlon et al., 2020), academic prestige and journal ranking systems (Beck et al., 2021), financial issues (Frank et al., 2023) as well as career development opportunities following these aspects (Beck et al., 2021).

Scientific journals are, to a large degree, researcher-driven enterprises. However, commercial publishers have established a firm grip on academia, and a large number of the most important journals are owned by large commercial publishing houses, which have huge profit margins and little interest in moving toward OA (Buranyi, 2017). The same scientific journals have acquired a central place in the scientific reward system, but they also constitute a democratic problem, as the cost of subscription and Article Processing Charges (APCs) are increasing at high rates (Butler et al., 2024; Jurchen, 2020). Today, the 12 largest publishers cover around 70% of all research output from the USA, China, the UK, France, Norway, and the Netherlands, which account for almost 53% of the global research output in 2015–2020 (Zhang et al., 2022). It is estimated that in 2020, the same 12 publishers had an estimated revenue of 2 billion USD from APCs in journals alone (Zhang et al., 2022).

This domination in the present publishing landscape is not new. In 2013, more than 51% of the social science and humanities papers were published by one of the five largest commercial publishers: Elsevier, Taylor & Francis, Wiley-Blackwell, Springer, and Sage Publications. If considering only the humanities, papers are more dispersed amongst several smaller publishers, with the top five commercial publishers only accounting for 20% of the published papers. The long-standing tradition in the humanities, including archaeology, for publishing in scientific books and anthologies as well as local journals, often non-English journals, are factors affecting these comparatively low numbers (Larivière et al., 2015).

Researchers, funders, and governing bodies adhere to the principle that scientific knowledge and research results should be freely available or subject to minimal restrictions, especially when they are publicly funded. It is worth noting that since the internet came into regular use, scholars have had the possibility to make research results and data available through self-archiving and Green OA. Today, we have numerous choices for sharing research results and data online either in OA journals (e.g., Open Archaeology, Journal of Archaeological data, Internet Archaeology), online repositories (e.g., ArXiv, SocArXiv, Zenodo), or institutional research archives (e.g., duo.UiO.no, DASH), making OA publishing relatively easy. The optimistic view that merging the old tradition of scientific publishing with new technology in the early 2000s should lead to a new publishing landscape is unfortunately proved wrong (Haug, 2019). Tennant et al. (2016) showed that 79% of the published scientific papers could have been OA within 12 months after publication via Green OA, and 62% of them immediately after publication via author self-archiving in repositories or institutional archives (Gargouri et al., 2012). Nevertheless, less than 50% of the scientific publications listed in the Web of Science and Dimensions are OA (Basson et al., 2022).

Scientific publishing is used to disseminate new knowledge among researchers, but scientific results also carry a non-academic and sometimes commercial value for user groups labeled as “other curious minds” in the Budapest Open Access Initiative (Wenaas & Gulbrandsen, 2022). As a result, the governments in different countries have started to require that research results funded by public funds be made accessible to the public. Norway, which is the case used here, is considered a “cautious forerunner” in the pursuit of OA. As pointed out by Wenaas and Gulbrandsen (2022), the Norwegian government issued a White Paper on OA already in 2005 as a response to the increasingly high subscription fees paid by university libraries. OA has since been addressed in a series of parliamentary reports. In 2017, the Norwegian government issued national goals and guidelines declaring that publicly funded research results were to be made openly available by 2024 (Ministry of Education and Research, 2017). It also stated that Norway aimed to be a driving force in making publicly financed research articles openly available at the time of publishing, thus encouraging funders, institutions, and researchers to practice these guidelines to achieve this aim.

When national OA guidelines were introduced in 2017, university policy documents changed accordingly. Current institutional policies accept Green OA, and the universities expect researchers to upload scientific papers or post-prints to the Current Research Information System in Norway (Cristin) or institutional scientific archives (e.g., duo.uio.no) with the aim of making them available in open repositories. When choosing between publication channels of equal academic quality, researchers are recommended to choose publication channels with the widest OA distribution, either by Diamond or Gold OA or in journals allowing Green OA (UiB, 2024; UiO, 2024; UiT, 2024). The subsequent introduction of rights retention policies has strengthened the possibility of immediately sharing accepted manuscript versions freely without extra administrative work for individual researchers.

In 2018, the Research Council of Norway (RCN) joined Plan S, a progressive initiative toward a quicker transition to OA. Norway was through RCN a main proponent behind cOAlition S, a consortium made up of a range of national and private research funders, the European Research Council, and the European Commission. cOAlition S unveiled a radical initiative stating that by January 1, 2020, researchers funded by public grants were required to make papers immediately freely available as Gold OA when published. The requirements were watered down in later versions accepting Green OA as sufficient. Plan S was a controversial policy initiative toward OA and researchers raised concerns on how the plan could affect scholarly communication and academic freedom (Kamerlin et al., 2021). The plan caused considerable debate in academia, and in Norway, c. 1100 researchers signed a petition, urging the Norwegian government and RCN to implement a consequence assessment of the possible consequences for research quality and research development if implementing Plan S. Due to the controversies, the implementation of the plan was delayed until 2021.

Most strategies for OA are connected to choices by the researchers and their decision to choose OA journals or Green OA. More recently and due to the increased attention to OA, strategies involving conversion of journals to OA are becoming more common (Wenaas, 2021), and several initiatives have been introduced in different countries. Among these are transformative or publish and read agreements between institutions and publishers, aiming to transform the business model underlying scholarly publishing (Table 1). Publish and read-agreements (PAR) combine the subscription fee, and the article processing charges (APC) within the same deal (ESAC, 2024 for an overview of PAR agreements). Through these agreements, the institutions or institutional consortiums cover the researchers’ cost of OA, the APC, while also paying subscription fees – thus, basically charging institutions twice. This includes unlimited OA publishing in hybrid journals and a discount on publishing in fully Gold OA journals. The aim was to achieve OA on both publishing and reading and it should, as time-limited transformative agreements, contribute to flipping the journals from closed to open within a set period, and ideally contribute to reducing cost for publishing as well as leaving journal preference among scholars unchanged (Wenaas, 2021). The PAR-agreements have made it possible for Norwegian researchers, if working at an institution taking part in the agreements, to publish in the vast majority of the largest journals without a cost for the individual researcher, and it has led to an increase in immediately accessible journal papers. However, it has not necessarily resulted in more OA papers overall as Green OA seems to decline correspondingly (Forskningsrådet, 2023, p. 20).

3 Methods and Data

In this article, we investigate trends in OA publishing from 2010 to 2021 among archaeologists at archaeological institutes and museums located at Norwegian universities. An overview of publications was achieved by collecting data from the Current Research Information System in Norway (Cristin). This database holds publication records from 102 research institutions in Norway and represents a near complete record of publicly funded research in Norway (Wenaas, 2022). Entries published by archaeologists at the county administrations or the Norwegian Institute for Cultural Heritage Research (NIKU) are not included, but as the great majority of researchers are situated at the universities, we consider our data to be representative of the publication trend in Norway. Each record in Cristin has an OA status defined at the registration of a publication in the database and is regularly updated with data from Unpaywall (Unpaywall, 2024). The OA status is defined at three levels: None, Gold, and Green. Green OA publications are available as a pre- or post-print, while Gold OA publications are freely available under an open license, irrespective of whether the publication involves payment of article processing charges or not. Depending on the OA status of the text registered in Cristin, these are made available through institutional repositories. In our case, these are NTNU Open (https://ntnuopen.ntnu.no/), Bergen Open Research Archive (https://bora.uib.no), UiO DUO (https://www.duo.uio.no/), UiS Brage (https://uis.brage.unit.no/), and UiT Munin (https://munin.uit.no/).

We exported data from Cristin using the R package rcristin (Karlstrøm, 2019). Data for 2010–2021 were retrieved for archaeological departments at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU), the University of Bergen (UiB), the University of Oslo (UiO), the University of Stavanger (UiS), and the University of Tromsø (UiT). Due to re-organizations at some of the institutions, we extracted data from multiple departments at each institution, thus accounting for present and previous organizational structures (Table 2).

Overview of archaeological institutes and departments with identification numbers as they are organized in Cristin

| Institution | Subdivision 1 | Subdivision 2 | Subdivision 3 | Cristin ID |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NTNU | Faculty of Humanities | Department of Historical and Classical Studies | 194.62.75.00 | |

| NTNU | Faculty of Humanities | Department of Historical Studies | 194.62.65.00 | |

| NTNU | University Museum | Department of Archaeology and Cultural History | 194.31.05.00 | |

| UiB | Faculty of Humanities | Department of Archaeology, History, Cultural Studies and Religion | 184.11.22.00 | |

| UiB | University Museum of Bergen | Department of Cultural History | 184.34.30.00 | |

| UiB | University Museum of Bergen | Department of Cultural History | Department of Antiquities | 184.34.30.20 |

| UiO | Faculty of Humanities | Department of Archaeology, Conservation and History | Archaeology | 185.14.31.10 |

| UiO | Museum of Cultural History | Department of Archaeology | 185.27.82.00 | |

| UiS | Museum of Archaeology | Department of Archaeological Excavations | 217.09.05.00 | |

| UiS | Museum of Archaeology | Department of Collections | 217.09.02.00 | |

| UiT | Faculty of Humanities, Social Sciences and Education | Department of Archaeology, History, Religious Studies and Theology | 186.33.14.00 | |

| UiT | Faculty of Humanities, Social Sciences and Education | Department of Archaeology and Social Anthropology | 186.33.16.00 | |

| UiT | The Arctic Museum of Norway and Academy of Arts | The Arctic Museum of Norway | 186.41.15.00 |

Data from Cristin were not always subdivided in accordance with discipline, which required us to manually exclude publications from other fields (Table 2). We considered a publication “archaeological” when the subject field in Cristin listed archaeology, if one or more of the authors was listed as an archaeologist on the website of the respective institution, or if the publication channel was archaeological. We excluded results not classified as academic articles or chapters in edited books, such as newspaper articles, conference presentations, and posters. Cristin defines journal papers as Academic article, and chapters in edited books as Introduction, Academic chapter/article/Conference paper, and Chapter.

Our manual review identified six entries misclassified as Academic anthology/Conference proceedings chapters in Cristin, and several chapters in edited books with a unspecified OA status. We therefore manually reviewed the anthology data, using the criteria listed above for determining the OA status of each chapter. This manual process is prone to error but given that the Cristin data were already found to be reasonably reliable also for anthology chapters, the general trends of interest should be adequately captured in the resulting data set.

The data set distributed with the repository for this article consists of 2,222 entries. After excluding duplicates, we could reduce entries to 1,848 publications. Finally, we removed publications not ranked according to the quality level in the Norwegian Scientific Index (NVI), resulting in a final dataset of 1,517 publications.

To investigate whether the publication trend in archaeology deviates from the general trend in the humanities, where archaeology is situated within the Norwegian academic sector, we include a comparative dataset of the humanities retrieved from the Open Access Barometer (OAB). OAB is hosted by the Norwegian Agency for Shared Services in Education and Research (SIKT, Table 1), which tracks OA publishing of Norwegian research, and data included in the OAB are based on reported entries of scientific articles in Cristin. Data for all sectors and the humanities were retrieved, allowing a comparison between archaeological OA publishing and the overall developments in the humanities and Norwegian research. The OAB covers the period 2013–2021 and includes only papers published as journal articles. However, as the OAB operates with more sub-categories for OA status than Cristin, we collapsed categories into the three categories used by Cristin. Furthermore, the OAB draws on more sources than Cristin for determining OA status, including the Directory of Open Access Journals (DOAJ) and Scopus. While we consider the Cristin data trustworthy, some artificial discrepancies in the below comparisons between archaeology and developments in Norwegian research more widely might therefore arise because of this.

4 Results

4.1 Trends in OA Publications in Norwegian Archaeology

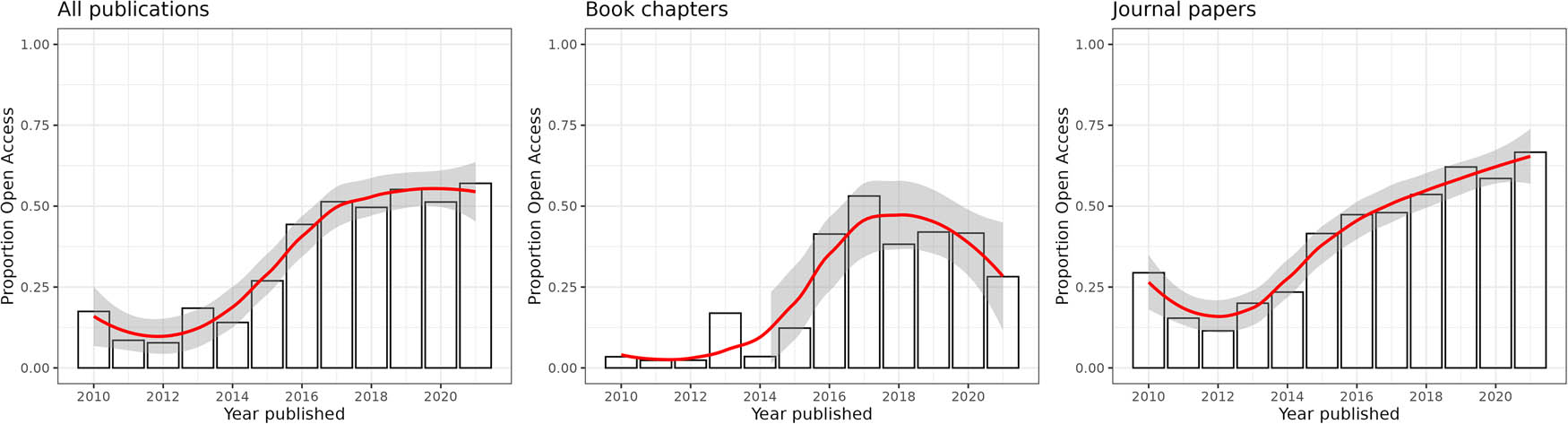

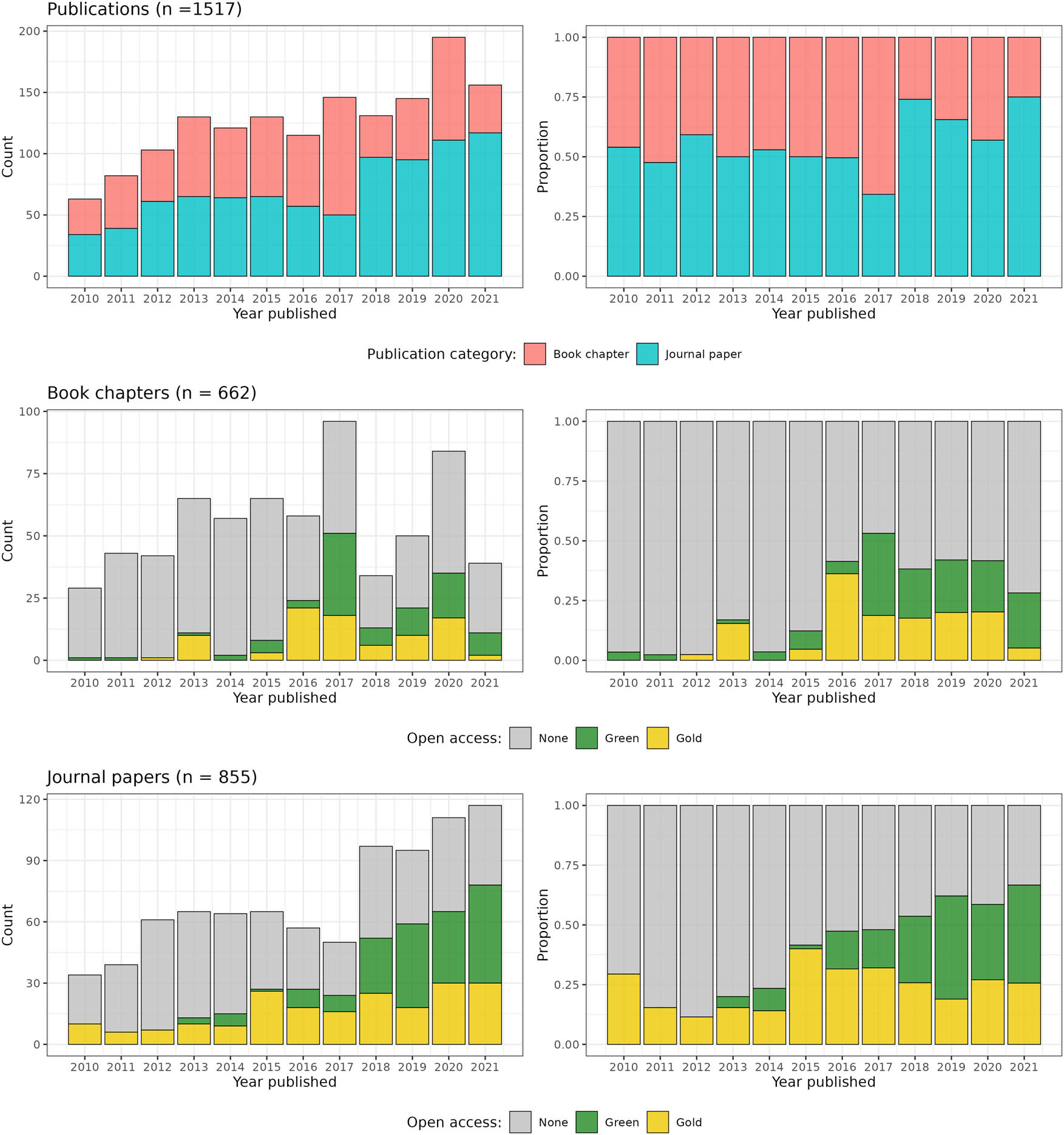

The OA status of archaeological publications from 2010 to 2021 is presented in Figure 1. As the time frame studied is relatively short and the number of publications each year is limited, we will point to observations, general trends, and yearly variations in the data set.

OA status of counted archaeological publications from 2010 to 2021.

There is a steady increase in the raw number of all archaeological publications, peaking in 2020, in line with overall scientific output across the different academic sectors. This is also in line with the marked increase in the number of researchers at universities and university colleges in general, which has surpassed 50% between 2010 and 2021.[1] The overall trend displays a relatively low proportion (below 25%) of Green and Gold OA publications before 2015, after which we see a near doubling in 2016 reaching close to 50%. The following years have a slightly higher proportion of OA, and after 2016/2017, the trend slowly rises to stabilize at around the 50% mark (Figures 1 and 2).

Development of the combined proportion of green and gold OA archaeology publications from 2010 to 2021. Locally estimated scatterplot smoothing (LOESS) curves with 95% confidence intervals are displayed.

With a share of 57% journal papers and 43% chapters in edited books across all years, there is an almost equal split between journal publications and edited books in the data set (Figure 3). From 2010 to 2016, the proportion of journal to edited book chapters fluctuated around the 50% mark; 2017 stands out as a year when research results were predominantly published in edited books, before journal papers became the most dominating publication format. Journal papers thus became the preferred medium of publishing relatively recently among Norwegian archaeologists, demonstrating the long-lasting tradition of publishing scientific books. This development is also in line with the general trend across the humanistic disciplines outside Norway (Larivière et al., 2015).

The relationship between archaeological journal papers and chapters in edited books.

While there was a largely equal split in preferred publication type, there is a large difference in OA-publication between journal papers and edited books. In total, 45% of the journal papers, and only 27% of the book chapters were published OA. While preference between publishing in one of the two formats generally impacts the proportion of OA publications for each year, the most marked growth in the number of journal publications, irrespective of OA-status, took place in 2018. The mentioned increase in OA-publications in 2016–2017 cannot be ascribed to a corresponding growth in the number of journal publications in archaeology but was instead driven by a larger proportion of book chapters that were published as OA during these years. From 2018, the proportion of OA chapters in edited books decreased, and the stable aggregated OA-trend from 2016 is maintained by the mentioned rise in OA journal papers.

4.2 Trends in OA Publication in Archaeology Compared to Other Research Disciplines

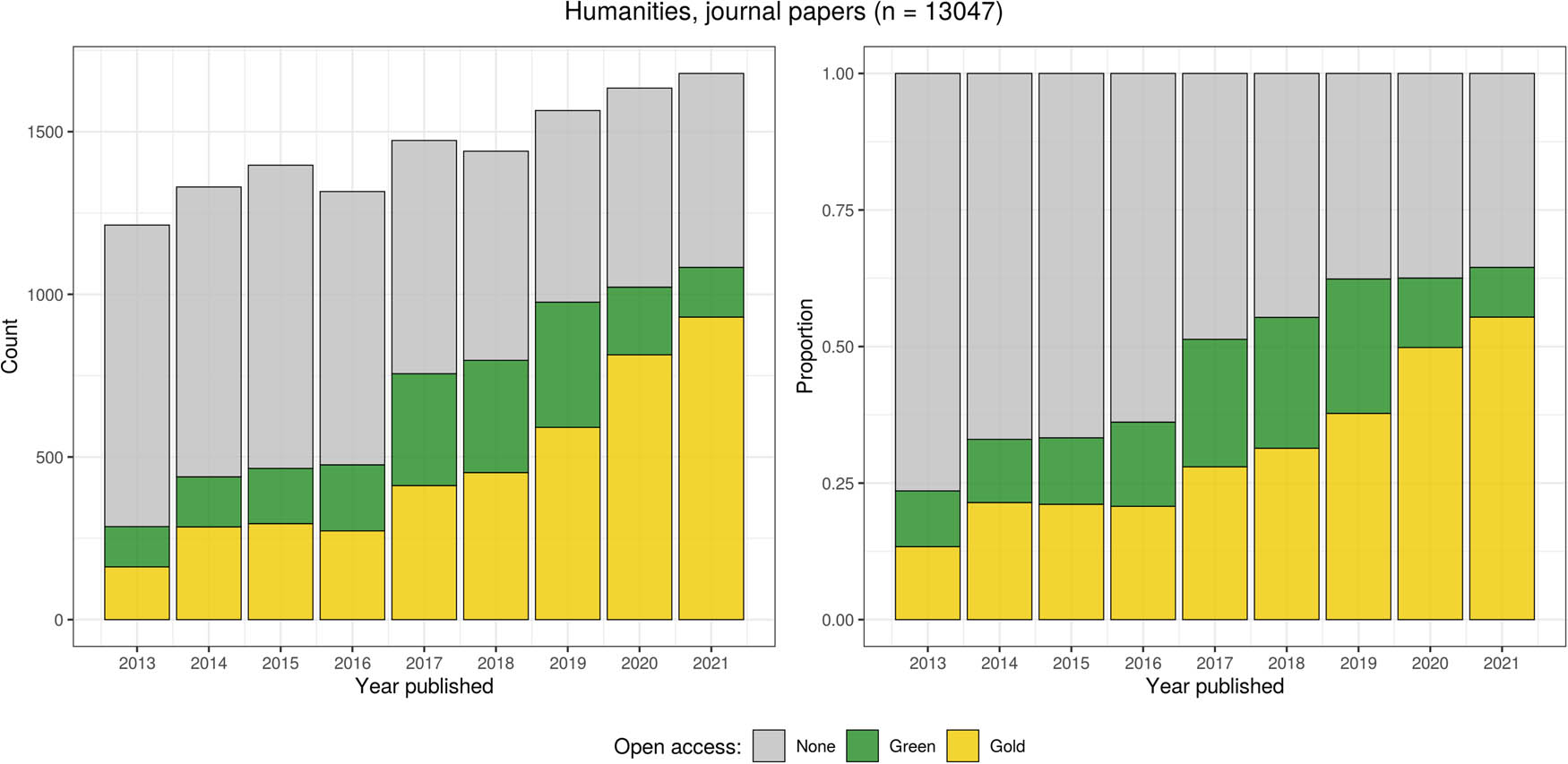

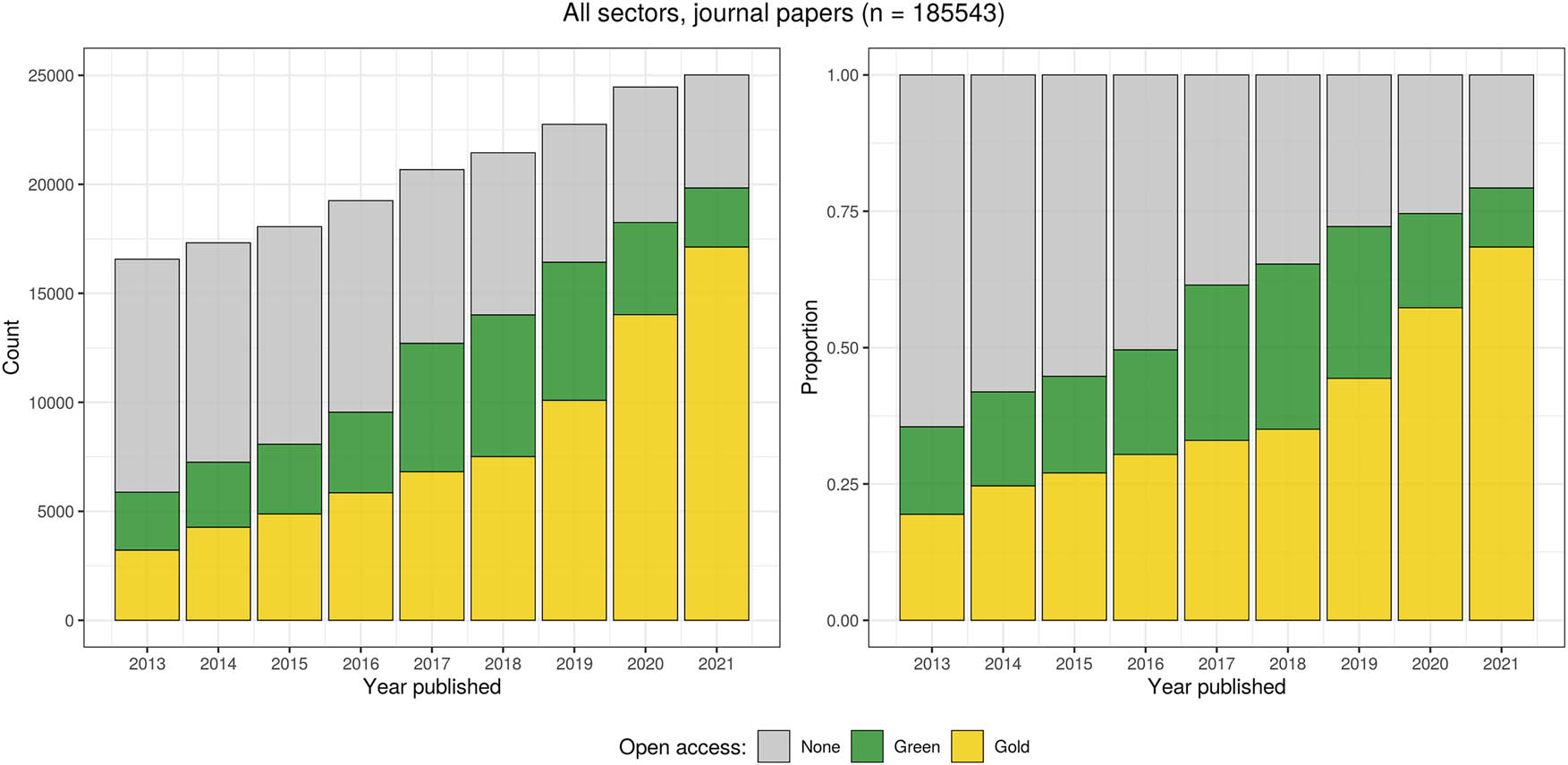

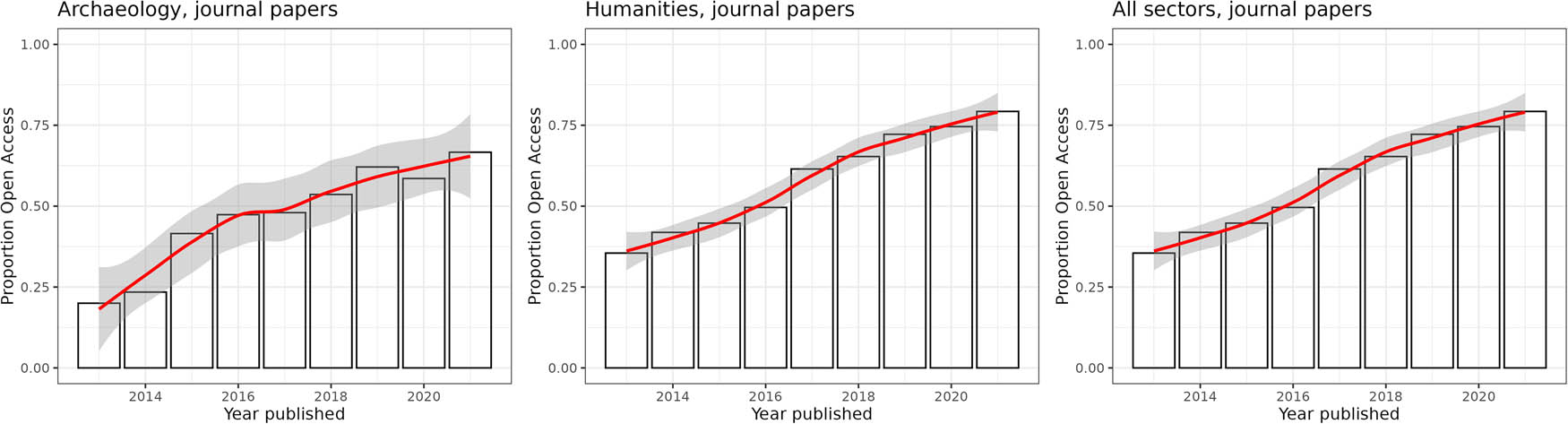

Comparisons with data from the humanities and all research sectors in Norway are given in Figures 4–6. The OAB is based on journal publications and is therefore most appropriate to compare with the archaeological journal data in Figures 2 and 3. The data from archaeological publications are more sensitive to stochastic fluctuations due to lower sample size, following for instance the timing of research output from larger research projects. This gives merit to also comparing the trends in the aggregated archaeological publication data to that of the OAB data, to reduce random noise. Also contrasting this with trends in archaeological book chapters makes it likely to better capture overall disciplinary trends. A pertinent question is how the OAB data would have looked if book chapters were also included in this data set. Book chapters (presumably) make up a large portion of the research output from within the humanities in general, at least if judged by the archaeological data presented here (c.f. Larivière et al., 2015).

Data from the OAB showing the OA status of journal papers published within the humanities in Norway between 2013 and 2021.

Data from the OAB showing the OA status of journal papers published across all research sectors in Norway between 2013 and 2021.

Development of the combined proportion of Green and Gold OA publications across archaeology, the humanities and all research sectors in Norway from 2013 to 2021. LOESS curves with 95% confidence intervals are displayed.

Irrespective of OA status, there is a general and steady increase in the number of journal publications within the humanities from 2013 to 2021 (Figure 6). The proportion of OA publications is also generally increasing, although there is a marked jump from 2016 to 2017 when the proportion for the first time exceeded 50% of the publications. Subsequently, the years 2019–2021 appear relatively stable. The proportion of OA archaeological journal papers generally follows a similar trajectory. There is a slightly lower proportion of OA publications in archaeology compared to the humanities in general in 2013 and 2014. However, already from 2015, there has been a marked increase in the proportion of OA journal papers within archaeology, and 2015 and 2016 are marked by a higher proportion of OA archaeological journal papers than within the humanities.

From 2015 to 2021, the trend is a general increase in OA journal papers in archaeology (Figure 6). In the humanities in general, we see an increase in OA journal papers from 2013 to 2021, with a pronounced increase from 2016 to 2017 (Figure 6). When comparing archaeology with other humanistic disciplines, we see similar trends. In the period 2013 to 2021, 50% of archaeological journal papers were published OA, compared to 48% within the humanities, and 60% within all research sectors.

Compared to other academic disciplines, the degree of OA publications is lowest in the humanities, according to the OAB (see also Mikki et al., 2018). Within the social sciences, about 75% of publications were OA during the last 3 years, while the percentage for the humanities was about 70%. Comparatively, the number for the natural sciences and health sciences was nearly 80%. In 2015–2016, archaeology had comparable numbers to all sectors, but after 2017 OA increased more rapidly in other disciplines (Figure 6).

5 Discussion

We have demonstrated changes in Norwegian archaeological research publications as mainly a gradual development toward an increased proportion of OA publications (Figure 5). Our results showed that from 2013 to 2021, 50% of archaeological journal papers were published OA, which is slightly above the proportion of journal papers in other humanistic disciplines (48%). There is a substantially higher proportion of OA journal papers (45%) than OA book chapters (27%) in our data set. In 2016, there was a significant increase in both chapters in edited books and journal papers compared to earlier years. After 2017 there has been a slight decrease in OA publication of archaeological book chapters while the proportion of journal publications continued to increase in the same period. What are the main drivers behind this development, and how does this relate to official and institutional initiatives?

Given that the trend in the aggregated archaeological data indicates that OA publishing has increased throughout the period and stabilized around 50% after 2016, it seems that chapters in edited books suppressed the increase in OA publication of journal papers. This tendency cannot reasonably be ascribed to a lack of awareness of OA before 2017, when edited books were preferred as a publishing format, as OA has been an important topic in academia already from the early 2000s (Wenaas, 2022) and in archaeology from around 2010 (Lake, 2012). A possible explanation could be that researchers favoring publication in edited books have a different attitude toward OA than researchers favoring publication in journals. It might possibly also be a difference in preferred publication type between different generations of researchers, but we see it as more likely that political demands, strategies, and facilitation of OA publishing at the institutional level are the main driving forces. Regardless of personal favoring, these factors probably pushed researchers to more frequently publish OA.

A factor possibly influencing the observed tendency and difference between book chapters and journal publications is the shift in the Norwegian publication indicator (NPI) in 2015 and how publication points (i.e., reward system) were calculated. The new system favored co-authorship across institutional and national borders to a larger extent than before, encouraging (international) cooperation. This also corresponds with a gradually increasing shift toward journals as the preferred publication channel across different disciplines within the academic sector in general (Hkdir, 2024). The combination of scientific journals’ much quicker turnover rate and an increasing political and institutional focus on publishing in international channels (Forskningsrådet, 2020), might have given Norwegian archaeologists a push to shift their publication strategies toward choosing journal publications over edited books.

When registering a scientific publication in Cristin, a full-text version of journal papers must be provided. This can either be a pre- or post-print, the author’s accepted manuscript, or the final proof of the text, irrespective of whether this is published OA or not. Chapters in edited books, on the other hand, are only encouraged to be uploaded, but this step can be skipped when registering these research results. Given that Cristin requires an active choice of what full-text version to upload when a journal paper is registered, this might result in more researchers providing OA versions of journal papers, as this, as opposed to book chapters, has been required for institutions to be rewarded in the NPI. Consequently, edited book chapters are made less available to researchers and the public. Demands from legislators and funders for OA publications have focused on journal papers, and Plan S, for instance, did not include OA for scientific books (monographs/edited books). This could also influence the relatively low percentage of OA book chapters and is especially relevant to humanistic disciplines as there are long traditions for publishing in books rather than journals. Combined with a lack of tradition for self-archiving (Marwick, 2020), this can contribute to explaining why the humanities tend to publish fewer OA articles compared to other academic disciplines.

The cost of making edited books OA is also a relevant factor for publishing trends. National and institutional OA publishing agreements (PAR deals) usually involve publishers that only have scientific journals in their portfolio. Popular anthology publishers for archaeologists, such as Routledge, Oxbow, Archaeopress, and Equinox are not covered by these deals and thus require researchers to pay pricey APC for OA publishing of the final products. Legal regulations and agreements between publisher and author might also be relevant here. Allowing Green OA to book chapters could affect book sales and the authors’ possibilities to upload chapters to online repositories might be limited. A reasonable explanation for the trend could be that the increase in OA publishing is not primarily the result of ideological convictions or changes in publication culture in the research communities, but that it is rather the response to demands and incentives at national political as well as institutional level for publishing OA as well as the high cost. This is supported by the observation that the tendency in OA publishing appears to have been relatively stable and fluctuating between 50 and 60% of all publications since 2016, even though awareness of OA should be assumed to have increased in the same period among researchers and initiatives from funders and legislators. If this holds true, we should expect an increasing trend in OA publishing in the near future as cOAlition S has issued recommendations that all books should be made OA (cOAlition S, 2021). RCN’s policies state that for projects receiving grants after 2023, immediate OA publication is recommended but if an embargo period is required, it must not exceed 12 months (Forskningsrådet, 2019). The Norwegian government also requires that publicly funded research results should be published OA within 2024.

There is close to an equal split between Gold and Green OA among all publications in our data from 2017 (Figure 2), but the green route seems to be the preferred way to make results openly available. The proportion of green OA publications increases similarly to the proportion of journal papers versus book chapters. Traditions for using post-print repositories and publishing OA varies between disciplines, and self-archiving and the use of preprint repositories prior to publication is less established within the humanities compared to natural and technical sciences (Marwick, 2020; Severin et al., 2020; Wenaas & Gulbrandsen, 2022). While this is becoming increasingly more common in interdisciplinary archaeology, it seems that few papers from archaeologists based at Norwegian institutions are uploaded to preprint repositories.

The increase in Green OA can most likely be explained by researchers using Cristin as a scientific archive, rather than a shift in behavior. If shifting sentiments among researchers were the main driver behind the increase in (Green) OA, we would also expect to see an increase in the number of Green OA book chapter publications, and possibly also in preprint servers, even if APCs were deemed too expensive and regardless of recommendations from funders and legislators. While the publishers listed above operate with an embargo period for uploading final versions of manuscripts, uploading preprints to repositories is free and technically easy to do, and thus offers a way around the APCs of edited books. Importantly, this requires a conscious and active choice from researchers. Compared to other disciplines, humanities scholars generally show lower levels of awareness of OA, and this, combined with the high cost of producing (OA) monographs and edited books (Severin et al., 2020), might be highly relevant to the trend we observe here.

There has been an increased focus among research institutions to implement policies on OA publishing since 2009. By 2019, all Norwegian universities with archaeological departments or museums had developed institutional policies for OA publishing. It seems that the trend toward more OA in archaeology is linked to national guidelines, institutional policies, and funders' initiatives more than a culture change among researchers – although this works in synergy. The universities are invited to comment on drafts of white papers and national guidelines and suggestions are often taken into consideration and implemented in the strategies. This is a reason why the introduction of OA in Norway appears to happen without serious friction between the institutions and researchers on one side and the implemented national guidelines on the other (Wenaas & Gulbrandsen, 2022). Implementations of OA strategies in the university policies trickle down to publishing practice and lead to a slow increase in OA publications. Thus, it seems fair to suggest that policies and funder mandates are the main drivers of OA publishing in archaeology in the last decade, a result that is in line with conclusions by Wenaas and Gulbrandsen (2022) concerning the development across different academic disciplines.

6 OA Publishing in Norwegian Archaeology and Beyond – The Wider Perspective

OA is important for maintaining the public legitimacy of archaeology as an academic discipline. In Norway, the state has a monopoly on excavations, which is regulated through the Cultural Heritage Act (see Nelson, 2023 for a Swedish perspective). Millions of Euros are spent on archaeological rescue excavations each year, and archaeological excavations and research are carried out in a total of five university museums, three maritime museums, and one archaeological research institute. While excavations are covered by the “polluter pays”-principle, research expenses are covered by the institutions or through research grants. To gain public trust, we need to communicate and make research findings accessible to the public, not exclusively to other scholars. From a global perspective, Marwick (2020, p. 167) has described the current publishing practice as a system of symbolic violence where paywalls lead to a monopolization of the right to determine what is legitimate knowledge. The dominant group - the authors, editors, and publishers – have shifting degrees of control over the value of publications, while subordinated groups are people that are historically underrepresented in archaeology and in academia, basically speaking, most people outside academia. As Marwick states, OA, and Open Research in general, opens archaeology for broader participation, and leads to the democratization of knowledge and opening of the research field. Although most archaeological papers in journals and edited books are never read outside the academic sector, this concern does not present a valid argument against OA publishing. The point is that it should be open and available, as (1) research is paid for by the public and (2) it has, in combination with different forms of dissemination to the public through, e.g., museums, media, and public lectures, the potential to enhance participation in the scholarly process, and because (3) it can expand inclusion in the creation and consumption of academic work.

OA as a scholarly publishing model has emerged as an alternative to traditional subscription-based journal publishing as the model aims to make research information freely accessible to a wide range of “curious minds” online as well as reducing the cost of journal subscriptions. In a survey of publishing decisions among international academic archaeologists, Beck et al. (2021) found that “Open Access” was the third most important factor in the choice of publication channel, while 37% ranked it as the first or second most important factor. This shows again that archaeologists are well-known to the challenges of the publication system and are invested in contributing to change the norms of this system. Interestingly, Beck et al. (2021) also observed fewer OA archaeological journals compared to the academic sector at large. As illustrated here, the growth of OA publishing holds promise but like researchers in other (humanistic) disciplines, archaeologists have been hesitant to fully adopt the OA model and make a complete shift in their publishing practices.

The recent shift toward APCs and PAR-agreements where costs transfer to publishers at the publication date by researchers, their institutions, and/or funding partners, is not improving the current situation. On the contrary, it shifts the paywall from reader to author. As Costopoulos (2018) puts it: The APC model is not in any way related to anything that can remotely be called OA, and OA is certainly not APC. Open means open. It doesn’t mean closed at one end, and it doesn’t mean closed at the other. While APCs and transformative agreements pose several challenges, the primary issue is the inequitable economic burden they place on researchers who lack external grant funding to cover those costs. Early career researchers, independent researchers, and researchers from resource-poor settings, i.e., low- and middle-income countries, where research environments typically do not allocate funds to cover APCs for OA publications are particularly prone to this challenge (Frank et al., 2023; Shu & Larivière, 2024). Any form of underrepresentation based on career stage, institutional, or geographical factors challenges the discipline and also leads to impoverishment of the discourse (e.g., Hutson et al., 2023). It is also argued that the cost of OA through APCs is causing elitism or classism in archaeology as the model depends on researchers being backed by a well-funded institution or other funders (Ribeiro & Giamakis, 2023). A recent negotiation of the PAR-agreement between the Norwegian Agency for Shared Services in Education and Research (SIKT) and Wiley recently broke down, as the final offer from the latter included a price increase compared to the previous agreement. This has left more than 50 Norwegian research institutions without an agreement with the publisher for 2025 (SIKT 2025), demonstrating that this can be a restraining issue for researchers also in high-income countries. These transformative agreements are meant to change the business models from subscription-based to OA, rather than behavior among researchers (ESAC 2025). Such strategies are obviously important, but one can ask if the introduction of APCs and transformative agreements are adequate incentives for publishers to contribute to changing the publishing system to become more open. The failure to negotiate a deal with Wiley serves as an example of the fragility of this approach and underlines the importance of archaeologists engaging in making research results openly available.

The path to OA publication faces numerous challenges, and navigating the legal landscape of publishing is indeed challenging. As a minimum, researchers can upload paper preprints to an online server or archive, and several institutions now have right retention agreements, ensuring that authors have the right to share the final accepted version of a paper, thus avoiding copyright issues. This policy ensures that researchers can follow the green OA route and make the manuscript openly available.

There may not be any simple solutions to the complex issue of open scholarly publishing, but as researchers, we have a responsibility to advocate OA and encourage peers to make research openly accessible without paywalls. The role of the researcher is in a way obvious; it is the researchers who choose to publish, select journals, and thus decide whether the article will be made openly accessible and in which version. This can be done in several ways; by using preprint servers, publishing accepted manuscript versions at online repositories or web pages (Green OA), using Peer Community Journals (e.g., PCI Archaeology) and publishing in serious and peer-reviewed open journals. By doing so, we can help ensure that knowledge is more readily available to the scientific community as well as a wider audience. This is not free of challenges for the single researcher (cf. Beck et al., 2021), but a commitment to OA has the potential to impact the accessibility and dissemination of scholarly knowledge. By committing to OA, we are doing the right thing for the scientific community and for those who fund us – the public.

7 Conclusion

Here, we have studied the development of OA publishing in archaeology by using Norway as an example. The data are retrieved from Cristin and consists of 1,517 publications published between 2010 and 2021 by archaeologists at the five Norwegian universities: UiO, UiB, UiS, UiT, and NTNU. In sum, around 50% of all papers were published OA with a significant difference between journal papers (45%) and chapters in edited books (27%). Our analysis demonstrates a growing trend toward more OA publications during the period with a stabilization of around 50% of all publications from 2016 to 2017 until 2021. The green route seems to be preferred by archaeologists, and this is likely related to the use of Cristin as a scientific archive as well as to index publications in the Norwegian publication indicator. This again coincides with what seems to be a preference toward publishing in scientific journals, at least for the most recent years.

The trend in archaeology was compared to general development in other humanistic disciplines and it generally follows the same tendency toward an increasing share of OA publications. Archaeologists (50%) have slightly more OA publications than the humanities sector (48%) in general. Both archaeology and other humanistic disciplines are below the proportion of OA publications across all academic sectors in Norway. The growth also seems to be slower.

The current reward system of science where publications in high-impact journals are at the core of academic merit systems and can come in conflict with OA and the principle that research results should be freely available and not put behind paywalls. In addition to state official and institutional guidelines and initiatives, a change in researcher behavior as well as in the merit system is necessary to progress. While discussions of the benefits of OA often center around the increased value to academics, increased access has wider and more positive benefits to research through increased visibility, facilitating innovation and decreasing financial pressure on academic and research libraries (the “serials crisis,” McGuigan & Russell, 2008, McKiernan et al., 2016, Tennant et al., 2016).

Despite strong incentives and clear expectations from the Norwegian government and institutions, our data and results indicate that researchers have often chosen not to publish in open channels. Our findings show that while the growth of OA publishing is promising, archaeologists remain reluctant to fully embrace the model and shift to OA. We believe that the upward trend in the discipline is largely driven by increasing demands from legislators, funders, and institutional policies toward a more open and democratic publishing landscape rather than a cultural change among researchers themselves or a shift in publishing behavior. The shift to APC-model can be regarded as an important step in changing the system, but the failure of renegotiating deals, as exemplified above, demonstrates a potential fragility in this approach.

This study is one of the very few that focus on publication strategies within archaeology, and we have unfortunately not been able to find studies from other countries and regions to compare with our data and results. Nevertheless, we believe our data and findings from Norway hold relevance outside the country as well. Since the expectations for OA publishing are largely uniform among funders and national governments, we anticipate that the trends and outcomes will be comparable in other European countries and beyond. We also hope this study will draw the attention of other archaeologists to this important topic and raise awareness of how we, as researchers, can choose to make our results available and openly accessible. As this study barely scratches the surface of OA publishing within archaeology, conducting similar studies in other areas, when combined with this one, would yield more generalized results. Thus, we highly welcome similar studies from other regions in the future that either back or contradict our results and interpretations.

-

Funding information: MØ was funded by a grant awarded by the Norwegian Research Council to the project Viking Beacons – Militarism in northern Europe, project no. 324454.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission. SS, HD, KL, IR, MØ, and SVN conceptualized the study. SS and IR developed methodology. SS, IR, and AS-E carried out the investigation of data. KL, IR, MØ, MS, and IY curated data. SS prepared the original manuscript with contributions from HD, KL, IR, MØ, AS-E, and SVN. All authors reviewed and edited the manuscript.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available in the Zenodo repository, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15101561.

References

Basson, I., Simard, M. A., Ouangré, Z. A., Sugimoto, C. R., & Larivière, V. (2022). The effect of data sources on the measurement of open access: A comparison of Dimensions and the Web of Science. PLoS One, 17, e0265545. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0265545.Search in Google Scholar

Beck, J., Gjesfjeld, E., & Chrisomalis, S. (2021). Prestige or perish: Publishing decisions in academic archaeology. American Antiquity, 86, 669–695. doi: 10.1017/aaq.2021.64.Search in Google Scholar

Björk, B. C. (2017). Open access to scientific articles: A review of benefits and challenges. Internal and Emergency Medicine, 12, 247–253. doi: 10.1007/s11739-017-1603-2.Search in Google Scholar

Buranyi, S. (2017). Is the staggeringly profitable business of scientific publishing bad for science? The Guardian.Search in Google Scholar

Butler, L. A., Hare, M., Schönfelder, N., Schares, E., Alperin, J. P., & Haustein, S. (2024). An open dataset of article processing charges from six large scholarly publishers (2019–2023). arXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.08356.Search in Google Scholar

cOAlition S. (2021). cOAlition S statement on Open Access for academic books [WWW Document]. https://www.coalition-s.org/coalition-s-statement-on-open-access-for-academic-books/ (accessed 2.6.24).Search in Google Scholar

Costopoulos, A. (2018). Elsevier, Unpaywall, and Aries Systems: the accelerating co-opting of the open access concept. ArcheoThoughts. https://archeothoughts.wordpress.com/2018/08/07/elsevier-unpaywall-and-aries-systems-the-accelerating-co-opting-of-the-open-access-concept/ (accessed 6.28.24).Search in Google Scholar

ESAC. (2024). ESAC Initiative [WWW Document]. https://esac-initiative.org/ (accessed 10.28.24).Search in Google Scholar

Forskningsrådet. (2019). Åpen tilgang til publikasjoner [WWW Document]. Åpen tilgang til publikasjoner. https://www.forskningsradet.no/forskningspolitikk-strategi/apen-forskning/publikasjoner/ (accessed 2.6.24).Search in Google Scholar

Forskningsrådet. (2020). Språk og vitenskapelig publisering [WWW Document]. Språk og vitenskapelig publisering. https://www.forskningsradet.no/indikatorrapporten/fokusartikler-og-dypdykk/sprak-og-vitenskapelig-publisering/ (accessed 2.6.24).Search in Google Scholar

Forskningsrådet. (2023). Strategi for vitenskapelig publisering etter 2024. Norges forskningsråd. https://www.openscience.no/media/3775/download?inline (accessed 2.6.24).Search in Google Scholar

Frank, J., Foster, R., & Pagliari, C. (2023). Open access publishing – noble intention, flawed reality. Social Science & Medicine 317, 115592. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2022.115592.Search in Google Scholar

Gargouri, Y., Larivière, V., Gingras, Y., Carr, L., & Harnad, S. (2012). Green and gold open access percentages and growth, by discipline. arXiv:1206.3664 11.Search in Google Scholar

Haug, C. J. (2019). No free lunch – what Price plan S for scientific publishing? New England Journal of Medicine, 380, 1181–1185. doi: 10.1056/NEJMms1900864.Search in Google Scholar

Heath-Stout, L. E. (2020). Who writes about archaeology? An intersectional study of authorship in archaeological journals. American Antiquity, 85, 407–426. doi: 10.1017/aaq.2020.28.Search in Google Scholar

Hkdir. (2024). Database for statistikk om høyere utdanning - DBH [WWW Document]. Database for statistikk om høyere utdanning. https://dbh.hkdir.no/tall-og-statistikk/statistikk-meny/publisering/statistikk-side/10.1/param?visningId=278&visKode=false&admdebug=true&columns=arstall&hier=instkode%219%21fakkode%219%21ufakkode%219%21itar_id&formel=1125%218%211126%218%211127%218%211128&index=1&sti=¶m=arstall%3D2022%219%21kanaltypekode%3D1%218%212&binInst=1101 (accessed 2.6.24).Search in Google Scholar

Huang, C. K., Neylon, C., Montgomery, L., Hosking, R., Diprose, J. P., Handcock, R. N., & Wilson, K. (2024). Open access research outputs receive more diverse citations. Scientometrics, 129, 825–845. doi: 10.1007/s11192-023-04894-0.Search in Google Scholar

Hutson, S. R., Johnson, J., Price, S., Record, D., Rodriguez, M., Snow, T., & Stocking, T. (2023). Gender, institutional inequality, and institutional diversity in archaeology articles in major journals and Sapiens. American Antiquity, 88, 326–343. doi: 10.1017/aaq.2023.36.Search in Google Scholar

Jørgensen, E. K. (2015). Typifying scientific output: A bibliometric analysis of archaeological publishing across the science/humanities spectrum (2009–2013). Danish Journal of Archaeology, 4, 125–139. doi: 10.1080/21662282.2016.1190508.Search in Google Scholar

Jurchen, S. (2020). Open access and the serials crisis: The role of academic libraries. Technical Services Quarterly, 37, 160–170. doi: 10.1080/07317131.2020.1728136.Search in Google Scholar

Kamerlin, S. C. L., Allen, D. J., de Bruin, B., Derat, E., & Urdal, H., 2021. Journal open access and Plan S: Solving problems or shifting burdens? Development and Change, 52, 627–650. doi: 10.1111/dech.12635.Search in Google Scholar

Karlstrøm, H. (2019). rcristin: Get Cristin results from the Cristin API. https://henrikkarlstrom.github.io/rcristin/index.htmlSearch in Google Scholar

Lake, M. (2012). Open archaeology. World Archaeology, 44, 471–478. doi: 10.1080/00438243.2012.748521.Search in Google Scholar

Larivière, V., Haustein, S., & Mongeon, P. (2015). The oligopoly of academic publishers in the digital era. Plos One, 10, e0127502. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0127502.Search in Google Scholar

Marwick, B. (2020). Open access to publications to expand participation in archaeology. Norwegian Archaeological Review, 53(2), 163–169. doi: 10.1080/00293652.2020.1837233.Search in Google Scholar

McGuigan, G. S., & Russell, R. D. (2008). The business of academic publishing: A strategic analysis of the academic journal publishing industry and its impact on the future of scholarly publishing. E-JASL: The Electronic Journal of Academic and Special Librarianship, 9, 1–15.Search in Google Scholar

McKiernan, E., Bourne, P. E., Brown, T., Buck, S., Kenall, A., Lin, J., McDougall, D., Nosek, B. A., Ram, K., Soderberg, C., Spies, J., Thaney, K., Updegrowe, A., Woo, K., & Yarkoni, T. (2016). The open research value proposition: How sharing can help researchers succeed. doi: 10.6084/m9.figshare.1619902.v2.Search in Google Scholar

Mikki, S., Gjesdal, Ø. L., & Strømme, T. E. (2018). Grades of openness: Open and closed articles in Norway. Publications, 6, 46. doi: 10.3390/publications6040046.Search in Google Scholar

Ministry of Education and Reaserch. (2017). National goals and guidelines for open access to research articles [WWW Document]. Government.no. https://www.regjeringen.no/en/dokumenter/national-goals-and-guidelines-for-open-access-to-research-articles/id2567591/ (accessed 2.6.24).Search in Google Scholar

Moksness, L., & Olsen, S. O. (2020). Perceived quality and self-identity in scholarly publishing. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 71, 338–348. doi: 10.1002/asi.24235.Search in Google Scholar

Moksness, L., Olsen, S. O., & Tuu, H. H. (2020). Exploring the effects of habit strength on scholarly publishing. Journal of Documentation, 76, 1393–1411. doi: 10.1108/JD-11-2019-0220.Search in Google Scholar

Nelson, M. (2023). The Swedish apparatus of contract archaeology and its entanglement with society. Current Swedish Archaeology, 31, 113–141. doi: 10.37718/CSA.2023.10.Search in Google Scholar

O’Hanlon, R., McSweeney, J., & Stabler, S. (2020). Publishing habits and perceptions of open access publishing and public access amongst clinical and research fellows. Journal of the Medical Library Association: JMLA, 108, 47–58. doi: 10.5195/jmla.2020.751.Search in Google Scholar

Ribeiro, A., & Giamakis, C. (2023). On class and Elitism in archaeology. Open Archaeology, 9, 1–22. doi: 10.1515/opar-2022-0309.Search in Google Scholar

Severin, A., Egger, M., Eve, M. P., & Hürlimann, D. (2020). Discipline-specific open access publishing practices and barriers to change: An evidence-based review. F1000Research, 7, 1925. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.17328.2.Search in Google Scholar

Shu, F., & Larivière, V. (2024). The oligopoly of open access publishing. Scientometrics, 129, 519–536. doi: 10.1007/s11192-023-04876-2.Search in Google Scholar

Tennant, J. P., Waldner, F., Jacques, D. C., Masuzzo, P., Collister, L. B., & Hartgerink, C. H. (2016). The academic, economic and societal impacts of Open Access: An evidence-based review. F1000Research, 5, 632. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.8460.3.Search in Google Scholar

UiB. (2024). The University of Bergen Policy for Open Science [WWW Document]. The University of Bergen Policy for Open Science. https://www.uib.no/en/foremployees/142184/university-bergen-policy-open-science (accessed 2.6.24).Search in Google Scholar

UiO. (2024). Strategy for open access at UiO [WWW Document]. Strategy for open access at UiO. https://www.ub.uio.no/english/writing-publishing/open-access/documents/strategy-open-access.html (accessed 2.6.24).Search in Google Scholar

UiT. (2024). Principles for open access to academic publications at UIT the Arctic University of Norway [WWW Document]. Sentrale regelverk ved UiT Norges arktiske universitet. https://uit.no/regelverk/sentraleregler (accessed 2.6.24).Search in Google Scholar

Unpaywall. (2024). Unpaywall: An open database of 20 million free scholarly articles [WWW Document]. https://unpaywall.org/ (accessed 2.6.24).Search in Google Scholar

Wenaas, L. (2021). Attracting new users or business as usual? A case study of converting academic subscription-based journals to open access. Quantitative Science Studies, 2, 474–495. doi: 10.1162/qss_a_00126.Search in Google Scholar

Wenaas, L. (2022). Åpen tilgang. Nytt Norsk Tidsskrift, 39, 51–61. doi: 10.18261/nnt.39.1.6.Search in Google Scholar

Wenaas, L., & Gulbrandsen, M. (2022). The green, gold grass of home: Introducing open access in universities in Norway. PLoS One, 17, e0273091. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0273091.Search in Google Scholar

Zhang, L., Wei, Y., Huang, Y., & Sivertsen, G. (2022). Should open access lead to closed research? The trends towards paying to perform research. Scientometrics, 127, 7653–7679. doi: 10.1007/s11192-022-04407-5.Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Etched in Stone: The Kevermes Stone Stela From the Great Hungarian Plain

- Waste Around Longhouses: Taphonomy on LBK Settlement in Hlízov

- Raw Materials and Technological Choices: Case Study of Neolithic Black Pottery From the Middle Yangtze River Valley of China

- Disentangling Technological Traditions: Comparative Analysis of Chaînes Opératoires of Painted Pre-Hispanic Ceramics From Nariño, Colombia

- Ancestral Connections: Re-Evaluating Concepts of Superimpositioning and Vandalism in Rock Art Studies

- Disability and Care in Late Medieval Lund, Sweden: An Analysis of Trauma and Intersecting Identities, Aided by Photogrammetric Digitization and Visualization

- Assessing the Development in Open Access Publishing in Archaeology: A Case Study From Norway

- Decorated Standing Stones – The Hagbards Galge Monument in Southwest Sweden

- Geophysical Prospection of the South-Western Quarter of the Hellenistic Capital Artaxata in the Ararat Plain (Lusarat, Ararat Province, Armenia): The South-West Quarter, City Walls and an Early Christian Church

- Lessons From Ceramic Petrography: A Case of Technological Transfer During the Transition From Late to Inca Periods in Northwestern Argentina, Southern Andes

- An Experimental and Methodological Approach of Plant Fibres in Dental Calculus: The Case Study of the Early Neolithic Site of Cova del Pasteral (Girona, Spain)

- Bridging the Post-Excavation Gaps: Structured Guidance and Training for Post-Excavation in Archaeology

- Everyone Has to Start Somewhere: Democratisation of Digital Documentation and Visualisation in 3D

- The Bedrock of Rock Art: The Significance of Quartz Arenite as a Canvas for Rock Art in Central Sweden

- The Origin, Development and Decline of Lengyel Culture Figurative Finds

- New “Balkan Fashion” Developing Through the Neolithization Process: The Ceramic Annulets of Amzabegovo and Svinjarička Čuka

- From a Medieval Town to the Modern Fortress of Rosas (Girona-Spain). Combining Geophysics and Archaeological Excavation to Understand the Evolution of a Strategic Coastal Settlement

- Technical Transfers Between Chert Knappers: Investigating Gunflint Manufacture in the Eastern Egyptian Desert (Wadi Sannur, Northern Galala, Egypt)

- Early Neolithic Pottery Production in the Maltese Islands: Initiating a Għar Dalam and Skorba Pottery Fabric Classification

- Revealing the Origins: An Interdisciplinary Study Into the Provenance of Sacral Microarchitecture–The Unique Case of the Church Model From Žatec in Bohemia

- An Analogical and Analytical Approach to the Burçevi Monumental Tomb

- A Glimpse at Raw Material Economy and Production of Chipped Stones at the Neolithic (Starčevo) Site of Svinjarička Čuka, South Serbia

- Archaeological Lithotheques of Siliceous Rocks in Spain: First Diagnosis of the Lithotheque Thematic Network

- Mapping Changes in Settlement Number and Demography in the South of Israel from the Hellenistic to the Early Islamic Period

- Review Article

- Structural Measures Against the Risks of Flash Floods in Patara and Consequent Considerations Regarding the Location of the Oracle Sanctuary of Apollo

- Commentary Article

- A Framework for Archaeological Involvement with Human Genetic Data for European Prehistory

- Special Issue on Digital Religioscapes: Current Methodologies and Novelties in the Analysis of Sacr(aliz)ed Spaces, edited by Anaïs Lamesa, Asuman Lätzer-Lasar - Part II

- Goats and Goddesses. Digital Approach to the Religioscapes of Atargatis and Allat

- Conceiving Elements of Divinity: The Use of the Semantic Web for the Definition of Material Religiosity in the Levant During the Second Millennium BCE

- Deep Mapping the Asklepieion of Pergamon: Charting the Path Through Challenges, Choices, and Solutions

- Special Issue on Engaging the Public, Heritage and Educators through Material Culture Research, edited by Katherine Anne Wilson, Christina Antenhofer, & Thomas Pickles

- Inventories as Keys to Exploring Castles as Cultural Heritage

- Hohensalzburg Digital: Engaging the Public via a Local Time Machine Project

- Monastic Estates in the Wachau Region: Nodes of Exchange in Past and Present Days

- “Meitheal Adhmadóireachta” Exploring and Communicating Prehistoric Irish Woodcraft Through Remaking and Shared Experience

- Community, Public Archaeology, and Co-construction of Knowledge Through the Educational Project of a Rural Mountain School

- Valuing Material Cultural Heritage: Engaging Audience(s) Through Development-Led Archaeological Research

- Engaging the Public Through Prehistory: Experiences From an Inclusive Perspective

- Material Culture, the Public, and the Extraordinary – “Unloved” Museums Objects as the Tool to Fascinate

- Archaeologists on Social Media and Its Benefits for the Profession. The Results and Lessons Learnt from a Questionnaire

- Special Issue on Network Perspectives in the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East and Eastern Mediterranean, edited by Maria Gabriella Micale, Helen Dawson, & Antti A. Lahelma

- Networks of Pots: The Usage of Ceramics in Network Analysis in Mediterranean Archaeology

- Networks of Knowledge, Materials, and Practice in the Neolithic Zagros

- Weak Ties on Old Roads: Inscribed Stopping-Places and Complex Networks in the Eastern Desert of Graeco-Roman Egypt

- Mediterranean Trade Networks and the Diffusion and Syncretism of Art and Architecture Styles at Delos

- People and Things on the Move: Tracking Paths With Social Network Analysis

- Networks and the City: A Network Perspective on Procopius De Aed. I and the Building of Late Antique Constantinople

- Network Perspectives in the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East and Eastern Mediterranean

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Etched in Stone: The Kevermes Stone Stela From the Great Hungarian Plain

- Waste Around Longhouses: Taphonomy on LBK Settlement in Hlízov

- Raw Materials and Technological Choices: Case Study of Neolithic Black Pottery From the Middle Yangtze River Valley of China

- Disentangling Technological Traditions: Comparative Analysis of Chaînes Opératoires of Painted Pre-Hispanic Ceramics From Nariño, Colombia

- Ancestral Connections: Re-Evaluating Concepts of Superimpositioning and Vandalism in Rock Art Studies

- Disability and Care in Late Medieval Lund, Sweden: An Analysis of Trauma and Intersecting Identities, Aided by Photogrammetric Digitization and Visualization

- Assessing the Development in Open Access Publishing in Archaeology: A Case Study From Norway

- Decorated Standing Stones – The Hagbards Galge Monument in Southwest Sweden

- Geophysical Prospection of the South-Western Quarter of the Hellenistic Capital Artaxata in the Ararat Plain (Lusarat, Ararat Province, Armenia): The South-West Quarter, City Walls and an Early Christian Church

- Lessons From Ceramic Petrography: A Case of Technological Transfer During the Transition From Late to Inca Periods in Northwestern Argentina, Southern Andes

- An Experimental and Methodological Approach of Plant Fibres in Dental Calculus: The Case Study of the Early Neolithic Site of Cova del Pasteral (Girona, Spain)

- Bridging the Post-Excavation Gaps: Structured Guidance and Training for Post-Excavation in Archaeology

- Everyone Has to Start Somewhere: Democratisation of Digital Documentation and Visualisation in 3D

- The Bedrock of Rock Art: The Significance of Quartz Arenite as a Canvas for Rock Art in Central Sweden

- The Origin, Development and Decline of Lengyel Culture Figurative Finds

- New “Balkan Fashion” Developing Through the Neolithization Process: The Ceramic Annulets of Amzabegovo and Svinjarička Čuka

- From a Medieval Town to the Modern Fortress of Rosas (Girona-Spain). Combining Geophysics and Archaeological Excavation to Understand the Evolution of a Strategic Coastal Settlement

- Technical Transfers Between Chert Knappers: Investigating Gunflint Manufacture in the Eastern Egyptian Desert (Wadi Sannur, Northern Galala, Egypt)

- Early Neolithic Pottery Production in the Maltese Islands: Initiating a Għar Dalam and Skorba Pottery Fabric Classification

- Revealing the Origins: An Interdisciplinary Study Into the Provenance of Sacral Microarchitecture–The Unique Case of the Church Model From Žatec in Bohemia

- An Analogical and Analytical Approach to the Burçevi Monumental Tomb

- A Glimpse at Raw Material Economy and Production of Chipped Stones at the Neolithic (Starčevo) Site of Svinjarička Čuka, South Serbia

- Archaeological Lithotheques of Siliceous Rocks in Spain: First Diagnosis of the Lithotheque Thematic Network

- Mapping Changes in Settlement Number and Demography in the South of Israel from the Hellenistic to the Early Islamic Period

- Review Article

- Structural Measures Against the Risks of Flash Floods in Patara and Consequent Considerations Regarding the Location of the Oracle Sanctuary of Apollo

- Commentary Article

- A Framework for Archaeological Involvement with Human Genetic Data for European Prehistory

- Special Issue on Digital Religioscapes: Current Methodologies and Novelties in the Analysis of Sacr(aliz)ed Spaces, edited by Anaïs Lamesa, Asuman Lätzer-Lasar - Part II

- Goats and Goddesses. Digital Approach to the Religioscapes of Atargatis and Allat

- Conceiving Elements of Divinity: The Use of the Semantic Web for the Definition of Material Religiosity in the Levant During the Second Millennium BCE

- Deep Mapping the Asklepieion of Pergamon: Charting the Path Through Challenges, Choices, and Solutions

- Special Issue on Engaging the Public, Heritage and Educators through Material Culture Research, edited by Katherine Anne Wilson, Christina Antenhofer, & Thomas Pickles

- Inventories as Keys to Exploring Castles as Cultural Heritage

- Hohensalzburg Digital: Engaging the Public via a Local Time Machine Project

- Monastic Estates in the Wachau Region: Nodes of Exchange in Past and Present Days

- “Meitheal Adhmadóireachta” Exploring and Communicating Prehistoric Irish Woodcraft Through Remaking and Shared Experience

- Community, Public Archaeology, and Co-construction of Knowledge Through the Educational Project of a Rural Mountain School

- Valuing Material Cultural Heritage: Engaging Audience(s) Through Development-Led Archaeological Research

- Engaging the Public Through Prehistory: Experiences From an Inclusive Perspective

- Material Culture, the Public, and the Extraordinary – “Unloved” Museums Objects as the Tool to Fascinate

- Archaeologists on Social Media and Its Benefits for the Profession. The Results and Lessons Learnt from a Questionnaire

- Special Issue on Network Perspectives in the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East and Eastern Mediterranean, edited by Maria Gabriella Micale, Helen Dawson, & Antti A. Lahelma

- Networks of Pots: The Usage of Ceramics in Network Analysis in Mediterranean Archaeology

- Networks of Knowledge, Materials, and Practice in the Neolithic Zagros

- Weak Ties on Old Roads: Inscribed Stopping-Places and Complex Networks in the Eastern Desert of Graeco-Roman Egypt

- Mediterranean Trade Networks and the Diffusion and Syncretism of Art and Architecture Styles at Delos

- People and Things on the Move: Tracking Paths With Social Network Analysis

- Networks and the City: A Network Perspective on Procopius De Aed. I and the Building of Late Antique Constantinople

- Network Perspectives in the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East and Eastern Mediterranean