Abstract

The article presents an early test case of the author’s ongoing project, in which she utilises aspects of social network analysis (SNA) to study social and economic life under Ptolemaios II Philadelphos and Ptolemaios III Euergetes as reflected in the largest surviving private archive from Ancient Egypt, the so-called Zenon Archive. Spanning a limited period of some 35 years (263–229 BCE), the c. 1845 documents of this archive reveal a wealth of information about individuals living under various conditions in Egypt and beyond. Since several places and persons are attested across more than one document, relational and attribute data retrieved from them can be meaningfully conceptualised and modelled as 1-partite and k-partite networks. With a case study of texts predating or written while Zenon travelled and worked as the financial minister’s private agent in the Levant, the author demonstrates how formal methods of SNA can be used to map, visualise, and analyse 3-partite networks of people and places mentioned in ancient texts. Finally, she reflects on what doing so on a larger scale may teach us.

1 Introduction

Since the first fragment of a text belonging to the so-called Zenon archive appeared on the antiquities market in 1911 (Pestman, 1980, p. 178; Vandorpe, 2015, p. 448), many more have come to light. In the summer of 2021, 1845 ancient texts covering a period of some 35 years (263–229 BCE) were linked to the archive in the online Trismegistos (TM) platform (Depauw & Gheldof, 2014). Collectively, they provide rich information about daily life and administration under Ptolemaios II Philadelphos (285–246 BCE) and Ptolemaios III Euergetes (246–222 BCE). Moreover, they do so from various perspectives since, in the words of Edgar, “every rank of society is represented among the correspondents, from the chief minister of the king down to the native swineherd writing from prison” (1931b, p. 3).

Network science offers conceptual and computational tools that can assist us in studying social and economic life in the times and places the archive sheds light on, but the grand size and heterogeneity of the data pose methodological challenges. Moreover, matters such as the nature of the sources, data, network type, and questions asked necessarily affect the relevance and appropriateness of available network analytical tools and approaches. With this article, I aim to highlight the spatial aspect of my ongoing Zenon project and explain how I utilise methods of social network analysis (SNA) to organise, model, and explore network data retrieved from the papyri that make up the archive.

Since the context of this article is an archaeological network analysis workshop and related special issue, I make use of several technical terms (marked with bold on first occurrence). Rather than defining them in the text, I have compiled a glossary for those not yet familiar with network jargon (Appendix A). Similarly, I refer to ancient texts by their unique TM text identifiers in the manuscript but provide the texts’ sigla in Appendix B.

For network analysis in archaeology, see e.g. Brughmans and Peeples (2023), Collar et al. (2015), Crabtree and Borck (2019), Peeples (2019); for applications in Near Eastern archaeology, Brughmans and Tambs (forthcoming). For introductions to SNA, e.g. Borgatti et al. (2013), Graham et al. (2022, pp. 191–261), Scott (2017), or the handbook by Wasserman and Faust (1994). For formal network analysis of archives from Egypt and the ancient Near East, see e.g. Cline and Cline (2015), Dutrey (2021), Gonçalves (2021a, b), Maiocchi (2016), Still (2019), Tambs (2020, 2022a, b, c, 2023), Veldhuis (2021), Wagner et al. (2013), and Waerzeggers (2014).

1.1 The Network Perspectives and Main Objectives of This Article

For studying the Zenon papyri from network perspectives, I conceptualise and model relational and attribute data revealed by the archive as k -partite networks (of persons and/or places mentioned in texts) and 1-partite networks (with pairs of persons linked by social and economic relationships). In doing so, the networks are built node by node and edge by edge in a bottom-up and semi-automated yet empirically grounded approach. This contribution presents concrete examples of the sort of data that can be extracted from ancient texts and analysed as k-partite networks.

After exploring a preliminary 2-partite network of people attested in the full corpus that is the archive, as well as explaining the principles of the data collection process through the example of a single text, the article presents a case study of information retrieved from a sample of 36 documents written between the spring of 263 and the spring of 258 BCE. Here, I employ a mixed-method approach of web scraping, close reading, literary review, and formal SNA to explore how the network approach can help us answer three related questions: (1) which individuals and places are mentioned in these early texts, (2) how are they – the identified texts, persons, and places – interlinked, and (3) how can spatial data be meaningfully incorporated into the project’s network models? The article closes with some reflections on the relevance of approaching the far larger text corpus that is the Zenon archive from such network perspectives.

2 Zenon Son of Agreophon and His Archive (263–229 BCE)

Zenon son of Agreophon was born in Kaunos in Caria (Turkey) c. 285 BCE but had settled in Egypt by the time he started to collect the documents today referred to as the Zenon archive (Vandorpe, 2019, p. 273). It should be clarified that Zenon was neither the only contributor nor the last owner of the archive, but the text group is named after him since he is believed to have filed and stored most of the documents (>95%) together in antiquity (Vandorpe, 2015, pp. 452–453). Moreover, the text group is classified as a private archive but represents a common mix of the subcategories of personal, family, and professional archives in that it includes documents relating to Zenon’ (and others’) official and private businesses (Fournet, 2018, p. 183). Only a rough overview of Zenon’s life and affairs is provided here, since they have been extensively described elsewhere (e.g. Durand, 1997, pp. 25–30; Edgar, 1918, pp. 160–161, 1931b, pp. 3–50; Rostovtzeff, 1979; Vandorpe, 2015, pp. 448–453, 2019, pp. 273–275), and the current article concerns but a selection of the earliest texts.

2.1 The Life of Zenon

When Zenon enters history in a letter (TM_1426) from 261 BCE, he is already a trusted employee of Apollonios, who served as the financial minister of king Ptolemaios II. The written evidence shows that Zenon’s career path and responsibilities changed several times in the period the papyri covers. Even so, he stayed loyal to his primary employer until Apollonios eventually disappeared from the documentation shortly after 246 BCE, when Ptolemaios III came to the throne (Vandorpe, 2015, p. 452).

It remains unknown how and when Zenon came to work for Apollonios, but an early letter (TM_2293) reveals that he was about to leave for the Levant on 23 November 260 BCE. Here, he would spend the next couple of years travelling and conducting business as Apollonios’ private agent. In this period, Zenon’s tasks involved inspection work, making purchases, arranging for goods to be imported, etc.

Collectively, a letter received in Kydisos (TM_1863) and a dated account (TM_742) reveal that Zenon returned to Egypt sometime between 5 March and 1 September 258 BCE (Pestman, 1981, p. 264). It is not known for which reason(s) Apollonios asked Zenon to return (TM_2019), but it has been suggested that a factor was the Second Syrian War (Vandorpe, 2015, p. 450), which became a reality as Antiochos II moved in to remove the tyrant Timarchos at Miletos in 259 BCE (Grainger, 2010, pp. 120–121; for the war’s effect on their lives, Durand, 1997, pp. 37–40).

It is generally believed that Apollonios lived in the capital, Alexandria, and that Zenon now joined him in residing there. For a while, he continued to work as Apollonios’ private agent and secretary. His duties now included accompanying the financial minister on inspection trips within Egypt’s borders. However, following a period of silence that was likely caused by illness (Vandorpe, 2015, p. 450), Zenon moved to Philadelphia (Gharabet el-Gerza) in the Fayum (Egypt), where he presumably spent the remainder of his life.

From the spring of 256 to 248/247 BCE, Zenon was the manager of a large estate owned by Apollonios near Philadelphia, but his obligations were by no means restricted to the physical and symbolic boundaries of the estate. From the surviving parts of his archive, we learn that he was simultaneously overseeing the expansion of the newly established town of Philadelphia, conducting public duties, engaged in various trades and businesses, and so on (Vandorpe, 2019, pp. 237–274). In addition, the papyri reveal that he got increasingly involved in private businesses.

Zenon stopped managing Apollonios’ estate in 248/247 BCE and in or shortly after 240 BCE, he appears to have given his documents to a man whose identity remains uncertain (for suggestions, see Vandorpe, 2015, p. 452). Even if Zenon was no longer the owner of the archive, it is clear that he stayed and continued practising his private businesses in Philadelphia and the Arsinoite nome, at least until he disappeared from history in 229 BCE.

2.2 Finding the Pieces

The ancient town and necropolis of Philadelphia are subject to extensive ongoing excavations, initiated in 2015 and 2016, respectively (Chang, 2019; Chang et al., 2020, 2023, 2024; Gehad et al., 2020, 2022a, b, 2023; Gehad, 2024), but very few authorised early excavations were conducted in the area. Viereck and Zucker found several texts from the site during their winter 1908/9 campaign (1926), but the papyri now believed to have formed part of the Zenon archive were unearthed by sebbakh-diggers and sold in batches on the antiquities market. Although Viereck and Zucker hypothesised that the Zenon correspondence “höchstwahrscheinlich in irgendeinem Hause von Philadelphia gefunden sein sind” (1926, p. 10), it is thus neither known where the manuscripts were found in modern times, nor where they were stored in antiquity. The Zenon archive, then, is an example of an ancient archive reconstructed in modern times (esp. by Pestman, 1981; for archival methods in papyrology, see Fournet, 2018; for methods of “museum archaeology,” also Vandorpe, 1994; for practices of storing papyri in antiquity and the scarcity of Egyptian archives found in situ, Ryholt, 2021; for archives of cuneiform sources, which are more frequently found together, e.g. Liverani, 2012).

A fragment of a letter addressed to Zenon from 7 December 252 BCE (TM_1877) was acquired by the British Museum as early as in 1911 (Pestman, 1980, p. 178), but this is an unusually early example. The larger part of the archive was sold from the winter of 1914 (Edgar, 1918, p. 159) until the mid-1920s (Gee, 2020; legislation relating to the antiquities trade in Egypt is summarised in Hagen & Ryholt, 2016, Table 5). As a result, preserved manuscripts and fragments were published in chunks and are now spread over a number of institutions and collections (Durand, 1997, pp. 13–14; Edgar, 1931b, pp. 1–2; Rostovtzeff, 1979, pp. 5–6; Vandorpe, 2015, p. 448). That some museums and institutions acquired texts that form meaningful groups does, however, suggest that the documents were at least left to be found in a partially organised state (Fournet, 2018, p. 178; Vandorpe, 2015, p. 448).

2.3 The Text Types and Data of Interest

A substantial part of what makes Zenon’s archive an unusually rich source into various aspects of life in early Ptolemaic times is its size: with c. 1845 documents, this constitutes the largest archive to have survived from Ancient Egypt. Others are the variety of people, places, and subject matters it concerns, as well as the level of trust, the nature of the responsibilities, and the variety of the tasks assigned to Zenon. He was clearly an entrusted employee and representative of the financial minster and, in extension, of the state, but also deeply involved in a range of affairs involving common workers and villagers. Since his affairs simultaneously reach across many places and trades, his documents offer glimpses into the lives and activities of people living under very different conditions.

As explained below, my data collection process starts with the online TM platform (Depauw & Gheldof, 2014). The associated description of the Zenon archive (Vandorpe, 2015) includes a rough indication of the text types represented in the archive as a whole (Chart 1).

Bar chart indicating the representation of text types in the Zenon archive. Chart by the author, based on Vandorpe (2015, 455 and App. 2).

Through classifying the texts at two levels – designating the text type (as “account,” “letter,” etc.) but also defining a sub-type (like “wine” or “private”) – this picture will become increasingly nuanced as I work my way through the ancient material (example below). In particular, I expect to drastically reduce the number of papyri here classified as “other texts” while increasing the number of categories, for example by introducing mixed types (like “account and list”). Already evident is, however, that most of the ancient sources are correspondences or texts of a documentary nature, as opposed to literary pieces. For studies of daily life, this is advantageous since it indicates that the archive contains “real” empirical data relating to the businesses, ways of life, and overlapping networks the attested persons were engaged in.

3 Extracting Network Data From the Zenon Archive

The methodology employed in my Zenon project is based on methods I developed for studying the small-scale community of Pathyris in Upper Egypt (186–88 BCE) from a network perspective (Tambs, 2020, 2022a, b, c) but is necessarily modified and extended to fit this project’s source material and main objectives (the aims of the larger Zenon project are now outlined in Tambs, 2023). For example, to meet the greater emphasis on geographical information of this project, I have to refine and design ways of incorporating geodata into the project’s database and network models.

From the Zenon papyri, I model two types of networks: 3-partite affiliation networks in which people and places are connected to the texts they are attested in; and 1-partite interpersonal networks in which pairs of individuals are tied by edges representing the social and economic relationships that linked them in antiquity. This article focuses on the former network type, whereas the latter is introduced in Tambs (2023). To explain my methodology and demonstrate the models’ different characteristics and potential, both network types are, however, exemplified below.

3.1 Online Resources and Semi-Automated Data Collection

Various online resources and databases now offer the digital humanist assistance for conducting (relatively) big data studies. For my research, the TM platform is particularly useful; in addition to offering metadata on the studied texts (TM Texts, Depauw & Gheldof, 2014), TM provides information on the individuals (TM People, Broux & Depauw, 2015) and locations (TM Places, Verreth, 2013) attested in them.

As a starting point, I retrieved information from lists of people attested in the documents of the Zenon archive from TM. Through more traditional methods of literary review and reading ancient documents in translation (and/or transliteration), the data are later checked and extended. Added information includes mentioned places and interpersonal relationships, but also node and edge attributes like the coordinates of a place, the biological sex of a person, or the date of a text, to mention but a few. Although the data collection process is still far from finished, visualising the result of the initial step – resulting in a 2-partite affiliation network of “individuals” mentioned in “texts” (Figure 1) – already gives a good impression of the cohesiveness of the text group and relevance of studying the archive under scrutiny with digital methods and SNA.

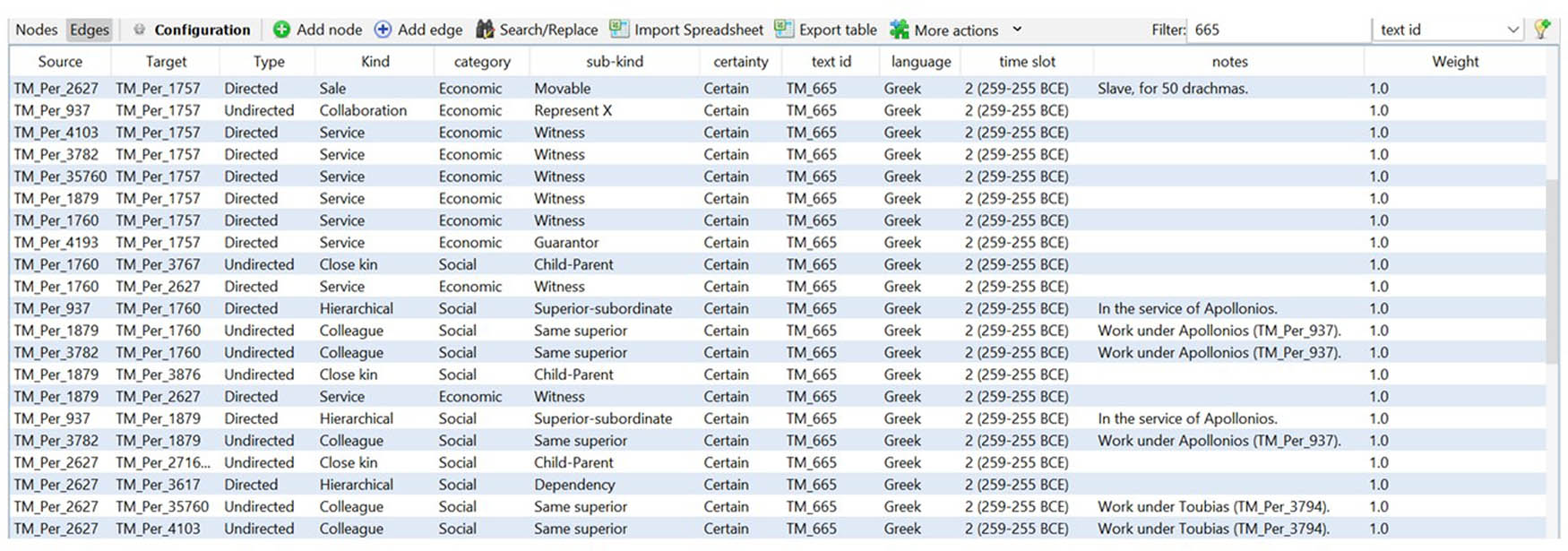

Directed 2-partite network of people attested in texts assigned to the Zenon Archive. Network size: 5,831 nodes (1,845 texts, 3,986 individuals) connected by 11,222 edges (attestations). Node colour: people (black), texts (red). Node size: large (the early texts). Layout: ForceAtlas2. Graph created by the author in Gephi.

After combining and modelling all of the TM lists of people mentioned in the texts as a single 2-partite network in the network analytical software Gephi (Bastian et al., 2009), it was deemed useful to visually distinguish the texts from the people to better “see” the network structure and potential of the dataset for network approaches. In Figure 1, nodes representing people are coloured black, whereas texts are shown as red dots. This serves to highlight the distribution of people and texts across the whole network, which comprises 5,831 nodes (3,986 persons and 1,845 texts) linked by 11,222 edges (here: attestations).

Measuring the nodes’ degree centrality scores reveals that they have an average degree of 1.9, but also that the network is characterised by a long-tailed distribution pattern, meaning that a handful of nodes have significantly higher degree centrality scores than the rest. Amongst the top five, we find Zenon and Apollonios, accompanied by three accounts mentioning an exceptionally high number of people. They are TM_936, TM_970, and TM_822, neither of which are included in the case study below. In applying this very common centrality measure we must not only keep the nature of the sources in mind, but also that in k-partite datasets, links are only allowed between nodes of different types. This serves as a reminder that a crucial part of the network analyst’s work is to critically assess the suitability of available tools, to identify useful metrics for the task at hand.

In this specific case, more reliable indicators of the overall connectedness of the source material (here measured as the degree to which the texts are indirectly linked by the people they mention) are the size and number of the connected components that make up the whole network. Although measuring the model reveals that it consists of 413 connected components, some 86% of the nodes and 96% of the edges form a core component. Moreover, positioning the nodes with the ForceAtlas2 layout algorithm (Jacomy et al., 2014) serves to clarify that most of the text nodes that are excluded from the core are isolates or part of relatively small connected components consisting of a single text and the individuals mentioned in it. This tells us that few of the disconnected texts mention at least one person attested in any other source in the TM data.

A similar tendency is observed for the selection of documents that make up the case study (below). Increasing the node size of these early texts and studying their network positions in the full dataset shows that three texts remain disconnected from all other texts (Figure 1). The vast majority are, however, not only included in the core component; they are also positioned in the same area of it.[1] This indicates that most early texts are also interlinked.

That many texts and persons are directly or indirectly connected by the concept of co-attestation is to be expected, but the relative size of the core component, combined with a very low density observed across the disconnected components, reveals the degree to which this notion is observed in the data. A high number of the attested persons and texts are already interconnected through a continuous path, and the number of connected components is expected to drop further once the prosopographical aspect is tightened through methods of literary review and close reading (albeit less dramatically so than in the case of Pathyris, Tambs, 2020, p. 176) and another mode – the places – is added to the dataset. As a case in point, the 3-partite network of the case study (below) is made up of seven connected components so long as both individuals and places are linked to texts, but nine if the places are filtered out (Figure 4). Before I present the 3-partite network extracted from these early texts, a concrete example will serve to clarify how the networks are modelled and what sort of data they are qualified with.

3.2 Literary Review, Close Reading, and Manual Data Collection – The Example of TM_665

For this exercise, we shall place a contract preserved in two copies on a single sheet of papyrus under the loop. TM_665 documents the sale of a young slave girl and reveals that the purchase took place in Birta in the land of Ammon (Transjordan) in 259 BCE. Six witnesses testify to Nikanor (in the service of Toubias) selling Sphargis to Zenon (acting on behalf of Apollonios) for 50 drachmae. As translated in Tcherikover and Fuks (1957, p. 120), the contracts read:

To visualise such sources as 3-partite networks (Figure 2, top left), I model and represent the given text as red, mentioned individuals as light pink, and locations (incl. ethnics, etc.) as purple nodes, and draw directed edges from the text to each person/place mentioned in it. Regarding the place references, it should be noted that all edges receive a default weight of “1.” However, to distinguish between (1) words that designate locations, (2) those qualifying people, and (3) those describing things, food, animals, and the like, I tag edges recording place attestations with edge attributes signalling the role the given place takes in the given context. In this contract, for example, only three locations are attested as places (Alexandria, Birta, and Ammanitis), but more are referenced indirectly to identify or describe persons or their professions. For an example of the third usage, which is not represented in the contract at hand, we can turn to TM_674 (transcribed and translated in Durand, 1997, pp. 122–123). In this account of goods imported by the captain Herakleides in 259 BCE, commodities include jars specified to be from Chios and Thason, as well as walnuts from Chios and Pontus.

![Figure 2

Directed 3-partite network (top left) of people and places mentioned in TM_665 (Network size: 39 nodes [1 text, 25 individuals, 13 places] connected by 65 edges [attestations]. Node colour: text [red], individual [light pink], place [purple]. Node size: out-degree. Edge colour: attestation [grey]. Layout: ForceAtlas2); directed 2-partite network (top right) of people mentioned in TM_665 (Network size: 26 nodes [1 text, 25 individuals] connected by 44 edges [attestations]. Node colour: text [red], individual [light pink]. Node size: out-degree. Edge colour: attestation [grey]. Layout: ForceAtlas2); 1-partite network projection (bottom left) of people mentioned together in TM_665 (Network size: 25 nodes [25 individuals] connected by 300 edges [co-attestation]. Node colour: male [light green], female [dark green]. Node size: betweenness centrality. Edge colour: co-attestation [grey]. Layout: as in Figure 2, top right); and mixed 1-partite network (bottom right) of interpersonal relations revealed by TM_665 (Network size: 25 nodes [25 individuals] connected by 56 edges [39 social, 17 economic]. Node colour: male [light green], female [dark green]. Node size: betweenness centrality. Edge colour: colleague [brown], service [yellow], hierarchical [dark purple], close kin [red], collaboration [green], sale [blue]. Layout: ForceAtlas2). Graphs created by the author in Gephi.](/document/doi/10.1515/opar-2025-0040/asset/graphic/j_opar-2025-0040_fig_002.jpg)

Directed 3-partite network (top left) of people and places mentioned in TM_665 (Network size: 39 nodes [1 text, 25 individuals, 13 places] connected by 65 edges [attestations]. Node colour: text [red], individual [light pink], place [purple]. Node size: out-degree. Edge colour: attestation [grey]. Layout: ForceAtlas2); directed 2-partite network (top right) of people mentioned in TM_665 (Network size: 26 nodes [1 text, 25 individuals] connected by 44 edges [attestations]. Node colour: text [red], individual [light pink]. Node size: out-degree. Edge colour: attestation [grey]. Layout: ForceAtlas2); 1-partite network projection (bottom left) of people mentioned together in TM_665 (Network size: 25 nodes [25 individuals] connected by 300 edges [co-attestation]. Node colour: male [light green], female [dark green]. Node size: betweenness centrality. Edge colour: co-attestation [grey]. Layout: as in Figure 2, top right); and mixed 1-partite network (bottom right) of interpersonal relations revealed by TM_665 (Network size: 25 nodes [25 individuals] connected by 56 edges [39 social, 17 economic]. Node colour: male [light green], female [dark green]. Node size: betweenness centrality. Edge colour: colleague [brown], service [yellow], hierarchical [dark purple], close kin [red], collaboration [green], sale [blue]. Layout: ForceAtlas2). Graphs created by the author in Gephi.

Hence, as a practical means to distinguish between these types of place references while analysing the networks, the edges linking texts to places are currently qualified with the place’s “role,” specifying whether the location serves as a “place,” an “ethnic,” or an “adjective” in the given attestation (for places appearing as places, subcategories clarify whether it is mentioned as a “place,” “place (mentioned in dating),” or “place (written there)”). Recording such details as I consult the ancient texts will, for example, enable me to quickly hide all places not attested as places, remove places attested in dating formulae, or isolate and study texts mentioning people or commodities from a certain town or place separately.[2] Moreover, the networks are qualified with a range of attribute information that extends the potential and usability of the network data.

Such 3-partite models can help shed light on the movement of goods from or to specific regions, but for many questions, it will be more useful to analyse 1-partite networks of only persons, places, or texts. Existing tools and plugins for example allow researchers to effortlessly project (or compress) k-partite to 1-partite networks. If we project the 2-partite network of people-in-texts (Figure 2, top right) contained in this 3-partite model (Figure 2, top left), the relational ties of the resulting network of people (Figure 2, bottom left) are, however, still based on (co-)attestations. Moreover, much data recorded in the 3-partite network are lost in the process.

In transforming the 3-partite network visualised in Figure 2 (top left) into a 1-partite network of people (Figure 2, bottom left) using the Multimode Networks Transformation plugin developed by Jaroslav Kuchar,[3] we, for example, ignore the mode that is the places. Furthermore, since our example is a single text, we are left with an unrealistically dense network in which all possible relations are realised: since everyone is now connected to everyone else, all attested persons have a degree centrality of “24” and the whole network has a density of “1.” Increasing the dataset will also increase the potential of the method, but the fact remains that much is lost or obscured.

As a case in point, compressed versions of the much larger network visualised in Figure 1 are presented in Appendix C.[4] By transforming this 2-partite network into two 1-partite networks (of people and texts, respectively), we arrive at two models characterised by very high numbers of cliques. The example serves to remind us of the nuances lost by this approach – including the edge attributes and parallel edges contained in the k-partite network. Connecting everyone mentioned in the same text can be meaningful for some questions but is unlikely to result in a model that accurately reflects lived realities. Network projection has been meaningfully applied in historical network research (Urbinati et al., 2022) and a clear advantage is that such models can often be generated quickly and on the basis of existing and “big” data. Their limitations should, however, also be acknowledged, and for my purpose, the advantages do not outweigh the costs.

Rather, the proposed interpersonal (1-partite) network approach (Figure 2, bottom right) moves beyond the assumption that people and/or locations have something in common simply by being recorded in the same document. In striving to reach deeper understandings of the social and economic worlds of attested persons, these richly attributed 1-partite network models represent the social and economic bonds and activities the human actors were entangled in. Since the information of interested is not readily available, I build the edge-lists of these networks from scratch.

Collecting data for such models is admittedly time-consuming, but the data-collection process is again eased by TM: only individuals are here recorded as nodes, so the extracted TM lists of attested people can also form the backbone and prosopographical baseline of these node lists.[5] Because an individual is referred to by the same (string of) ID number(s) across the datasets, attribute data such as the person’s biological sex, profession, or origin can also be queried from the project’s relational database for the node-list of the 1-partite networks.

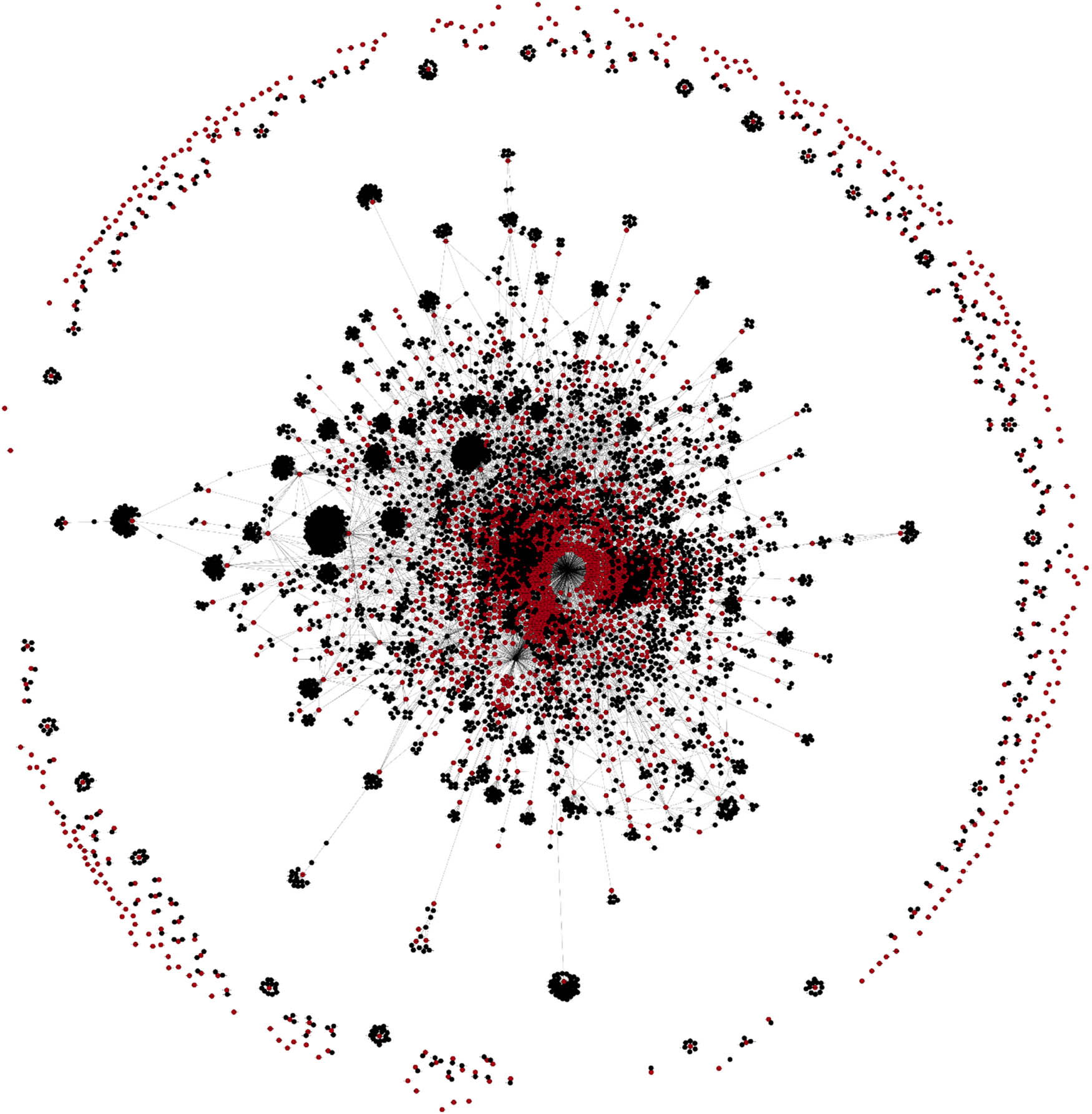

For creating the edge lists, the ancient documents are, however, carefully read and pairs of individuals manually linked by ties representing their socio-economic relationships. Since edges are drawn between pairs of persons based on intra-textual information, persons that cannot be meaningfully tied to anyone based on the content of the text at hand are ignored. To qualify and contextualise recorded actions and relations, I attribute the interpersonal edges with information about the relationship, but also metadata reflecting the source (such as document type and absolute and relative dates). For a concrete example of a selection of the edge attributes recorded in this dataset, we can again consider TM_665 (Figure 3).

Part of the edge-list with selected attributes qualifying interpersonal relationships recorded from TM_665, after Gephi import.

Based on the two surviving copies of this text, I recorded a total of 56 directed and undirected edges involving a total of 25 individuals. Once the social actors, relationships, and node and edge attributes have been identified, recorded, and organised into node- and edge-lists (with the source and target nodes of the latter mirroring the unique IDs assigned to the studied entities in the former), the lists can be effortlessly formatted, imported, and modelled as a social network in Gephi (Figure 2, bottom right).

From a network structural perspective, exposing the k-partite and 1-partite datasets to the same layout algorithm (ForceAtlas2) before visually comparing the network visualisations of the graphs representing the given text (Figure 2) serves to illustrate that the collected 1-partite network (Figure 2, bottom right) is more complex and reminiscent of what we would expect of a real-world network. Certain information, like the fact that only one woman is mentioned in the contract, can be easily highlighted in either model, but only this interpersonal network representation offers the insight that not all persons recorded in social or economic relations are directly or indirectly linked to one another. Whereas this information is already in the gathered dataset, other results – such as the realisation that the well-known Toubias and Apollonios, on whose behalf Nikanor and Zenon act, both have betweenness centrality scores of 0.0 – are network specific.

It is of course difficult to argue that formal methods of SNA are needed for studying a single document, since we could admittedly have arrived at these findings by reading and analysing the text with other methods. An essential question in network science and historical network research, then, is one of scale; the value of recording and analysing network data from ancient texts will be more easily recognised once we move beyond the boundaries of this contract, to model the datasets representing the 36 early documents (and eventually the entire Zenon archive) as such networks. To illustrate this point, and remembering that the article concerns the 3-partite network approach, we shall proceed to model the 3-partite network data gathered from the selection of early texts by the same principles.

4 Case Study of Early Dated Documents in the Zenon Archive (263–258 BCE)

To test and modify my methodology, I defined and studied an easily digestible sample of early documents with known dates in the fall of 2021, which helped me gain an initial impression of the potential of the sources, datasets, and research methods I was developing in the process. The following concerns this test case.

4.1 Dealing With Time

Here it should be noted that the task of dating the Zenon papyri is complicated by three calendars being in use at the time (as outlined and explained in Pestman, 1981, pp. 215–217; also Edgar, 1917, 1931b, pp. 50–57). For the absolute dates of the documents, I thus rely on existing scholarship. In addition to noting down exact dates (as given in the ancient text or established by scholars), I group documents into time slots (representing predefined windows of time) as well as phases (defined by shifts in Zenon’s career and responsibilities). The latter approach resembles that of Vandorpe (2015), whose four phases are based on the six periods defined by Pestman (1981, p. 171), whereas the time slot system was introduced as a means to enhance the diachronic analysis of the social networks (as in Tambs, 2022b, pp. 328–344). By this threefold dating system, many texts can be assigned to an appropriate time slot and/or phase based on tentative dates or context, even if the exact date of the document in question is lost or unknown (see also Section 5).

4.2 Selecting the Sources

Before settling on the larger project’s methodology, I deemed it favourable to prepare and analyse sample datasets that were sufficiently small for results to be critically assessed, yet big enough to reveal some general trends. For this purpose, I focused on dated texts from the earliest phase (A: 263–258 BCE), i.e. documents written before or while Zenon was working as Apollonios’ private agent in the Levant. With this temporal restriction, the number of ancient texts was reduced to 36 documents, of which 21 were found to mention at least one pair of individuals that can be meaningfully linked by a social or economic relationship.[6] Having studied these documents up close, a more detailed typological landscape of early texts emerged (Chart 2).

Bar chart showing the text type distribution of the earliest dated texts. New categories are added at the end of the list presented in Chart 1. Chart by the author.

As expected, (nearly) all early sources are correspondences, accounts, and/or lists documenting things distributed, paid, purchased, shipped, and controlled, but also for example trips made and favours asked for. It is worth noting here that accounts are often undesirable to the network analyst, since identifying individuals in them is often (near) impossible. Nevertheless, several persons mentioned in these accounts have been identified (on accounting practices in the archive, see esp. Grier, 1934). Because many persons attested in the Zenon papyri are well known, even those mentioned in small fragments of accounts can sometimes be identified from context, subject matter, the mention of other persons, etc.

An early account of corn allowances from 10 April to 9 May 263 BCE (TM_1299) – i.e. written well before Zenon left Alexandria for the Levant – will serve as an example. C. C. Edgar (1931a, p. 108) put forward that the collection of names listed in it shows that the account relates to the household of Apollonios. With reference to the unique identifiers used in the lists of people mentioned in this and other texts, this is also reflected in the raw data extracted from TM. According to TM, 3 of the 8 men reappear in additional texts from the archive: Charmides in 6 later documents; Simylos in another account from this case study (TM_2377) and 2 later texts; Iatrokles in 2 accounts from this case study (TM_2377 and TM_673) and 12 later papyri. If these cross-identifications are correct, TM_2377 (an account of wine distributions) reveals that the latter two formed part of Zenon’s travelling group in the early spring of 259 BCE. In addition, TM_673 (an account of imported goods) indicates that Iatrokles and a fellow agent of Apollonias named Nikanor (who is listed right below Iatrokles in TM_2377) included some goods for their families in shipments valuated in the late spring of the same year. Such details reveal tantalising information about ancient ways of life that, when scaled up to form part of large network models, can help us find more general patterns in the mess that is the heterogenous, highly personalised and context-bound actions recorded in such ancient texts.

Here, it should be noted that the early texts also represent a suitable case study from the spatial point of view. In addition to several of the documents mentioning locations or specifying the origin of persons or commodities, Zenon was travelling abroad for the larger part of this period. Two texts list places visited in 259 BCE: according to TM_666, Zenon formed part of a group travelling to Straton’s Tower, Jerusalem, Jericho, Abella, Sorabitta, Lakasa, Noe, Eitoui, Baitanata, Kydisos, and Ptolemaios Akko on a longer journey (Durand, 1997, pp. 60–69), whereas TM_668 relates to a shorter journey to Iemnai, Gaza, Marisa, and Adoreos (Durand, 1997, pp. 97–100). As we shall see, a relatively large number of places (59) are thus also attested in the discussed texts.

4.3 The 3-Partite Network of People and Places in Early Texts

Once the datasets are built, the node lists reveal which people and places are attested in the documents whereas visualising the 3-partite network as a node-link diagram helps us “see” how people and places are connected (by co-attestation). A glance at Figure 4 confirms the suspicion obtained from analysing the graph shown in Figure 1, namely that despite the vast geographical scope of the sources, dated texts (red nodes) from phase A are also largely interconnected by the people (light pink nodes) and places (purple nodes) they mention (cf. Figures 1 and 4). Measuring the network further reveals that this whole network consists of seven connected components, of which one is again vastly larger than the rest: some 86% of the texts explicitly mention at least one person or place that reappears in at least one other source.

Directed 3-partite network of 36 dated texts from the earliest phase of the Zenon archive. Network size: 279 nodes (36 texts, 184 individuals, 59 places) connected by 514 edges (attestations). Node colour: text (red), individual (light pink), place (purple). Node size: in-degree. Edge colour: attestation (grey). Layout: ForceAtlas2. Graph created by the author in Gephi.

Since this network is directed, with all edges pointing from a document to an individual or location mentioned in it, we can now use the measures of out- or in-degree centrality to quickly identify the texts that mention the most persons/places or the persons/places attested the most times, respectively (Table 1).

Top ranking nodes in Figure 4, with regard to out- and in-degree centrality

| Rank | Id | Text type | Sub-type | Out-degree | Rank | Id | Label | In-degree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | TM_2377 | Account | Wine | 89 | 1 | TM_Per_1135 | Artemidoros | 64 |

| 2 | TM_665 | Contract | Sale (movable) | 65 | 2 | TM_Per_1757 | Zenon | 16 |

| 3 | TM_668 | Account | Fish and places | 42 | 3 | TM_Per_937 | Apollonios | 15 |

| 4 | TM_666 | Account | Places and flour | 40 | 4 | TM_Per_3794 | Toubias | 12 |

| 5 | TM_673 | Account | Import/Export | 38 | 5a | TM_Per_3905 | Philon | 11 |

| — | — | — | — | — | 5b | TM_Geo_512 | Chios | 11 |

Doing so, and supplementing the results with attribute analysis, we find that four of the five highlighted texts are accounts. TM_2377 reports daily distributions of wine; TM_668 documents distributed fish and places visited during the shorter trip; TM_666 lists places of the longer journey and reports distribution of flour; TM_673 concerns goods shipped on two vessels and imported at Pelousion in the spring of 259 BCE; and finally, TM_665 is the contract used as an example above.

Studying the structure of the network and distribution of the highlighted nodes, we also notice that all top-ranking texts mention places, as well as persons, but only TM_673 mentions more locations than people. This is because it concerns the valuation of goods whose origin is often stated (for this event, see also TM_674 and TM_675). That the contract (TM_665) has the second highest out-degree score reflects that several place-references describe people, but also that the contract is preserved in two copies.

In the network visualisation (Figure 4), text nodes are small since node size is set to reflect the nodes’ in-degree centrality scores, but all highlighted texts are positioned in the core component. Still, only TM_666 holds a relatively central network position since the ForceAtlas2 layout algorithm serves to push poorly connected nodes away from the centre of the graph and most people and places mentioned in these texts are known from the given source only.

To highlight the person and place nodes attested across several texts, we can shift perspective by measuring and sizing the nodes according to their in-degree centrality (Table 1). Sticking with TM_665 as our example, Zenon, ‘Apollonios’ and ‘Toubias’ – who re-appear in a number of texts – are the second, third, and fourth most frequently attested actors in the whole network. While this is to be expected, hoovering over the TM_665 text node in Gephi will lead our attention to Herakleitos, who is also pulled closer towards the centre of the graph and receives a higher in-degree score than most. This is because the prosopographical baseline of the underlying TM data recognise that, as part of the travelling company, he also receives wine in the discussed TM_2377 (account).

Given the central parts played by Zenon and Apollonios in the archive, as well as the high status, powerful position, and extraordinary wealth enjoyed by the local chieftain Toubias (Goff, 2016, p. 265), it is unsurprising that these men are particularly well-attested in the early documents. The best-attested person by far is, however, a man named Artemidoros. He was also an agent (TM_668) but is exclusively listed in early accounts (TM_668, TM_1301, TM_1427, TM_2377), according to which he received wine, corn, fish, and barley for his horse (but see note 8).

The fifth highest in-degree score is shared by two nodes, representing a man (Philon) and a place (Chios), respectively. Like Artemidoros, Philon is only attested in accounts (or lists), but unlike him, a quick look at the raw data collected from TM (and visualised in Figure 1) reveals that we will meet him again in later texts. As for Chios (a Greek island), returning to the dataset and ancient texts reveals that this place’s high in-degree centrality score reflects that Chios is specified as the origin of jars, cheese, and walnuts in several lists and accounts (TM_673, TM_674, TM_675, TM_1172, TM_1701, and TM_2173).

While Chios is well-known for its exports, the relatively high in-degree scores of other place nodes might be more surprising. Places with in-degree centrality ≥3 include Miletos (in-degree: 9), Samos (9), Ptolemais Akko (8), Thasos (7) Syria (5), Minaia (4), Gaza (4), Pelousion (4), and Alexandria (3).[7] Worth noting is also that, in contrast to Artemidoros, whose unusually high in-degree centrality is largely explained by his frequent appearance in the account with the highest out-degree,[8] highlighted places tend to be attested a few times across several different documents. As information revealed by more texts is gradually incorporated into these models, the networks will thus become increasingly valuable for identifying patterns of connectivity and studying the paths travelled by people and things in antiquity.

4.4 Filtering by Attributes and Tracking Ancient Paths

Reminding ourselves that the questions asked in this article are how we can use SNA to explore (1) which individuals and places are mentioned in the ancient texts, (2) how they are interlinked, and (3) how such connections can be meaningfully modelled, the test case suggests that such 3-partite networks can already answer the first and help shed light on the latter two. The node lists already reveal which persons and places are attested, whereas the network models can be used as supplements to more traditional methods, for the purpose of exploring the connections between them. For this to be both doable and useful, care must be taken as we design the networks and collect the data “behind” the models.

For example, if a text reveals that an attested person can be meaningfully linked to a location – i.e. said to be in, travelling to, arriving from, or being from a certain place – one could tag the relevant text-to-person edge with the unique identifier(s) of the place(s) in question. With such information recorded as edge attributes, one could for example filter the graph visualised in Figure 4 to only show the edges signalling that a person was “in” a place, before hiding the now inactive nodes and re-running the ForceAtlas2 layout algorithm to more clearly see the structure of this subnetwork (Figure 5, top). As before, sizing the nodes according to in-degree centrality serves to highlight the individuals most frequently said to be in a place.

![Figure 5

Directed 2-partite network (top) of people-in-texts. The network is a subset of the core component of the 3-partite network shown in Figure 4, filtered to show only people and texts active in at least one edge signalling that a person was in a place (Network size: 27 nodes [7 texts, 20 individuals] connected by 47 edges [attestations]. Node colour: text [red], individual [light pink]. Node size: in-degree. Edge colour: different places. Layout: ForceAtlas2); directed weighted 2-partite network (bottom) of people-in-places. The network is based on data contained in Figure 5 (top) but reorganised so people are linked to the places they are revealed to have been in (Network size: 28 nodes [8 places, 20 individuals] connected by 24 weighted edges [in place]. Import strategy: sum. Node colour: place [purple], individual [light pink]. Node size: in-degree. Edge colour: black. Layout: ForceAtlas2). Graphs created by the author in Gephi.](/document/doi/10.1515/opar-2025-0040/asset/graphic/j_opar-2025-0040_fig_005.jpg)

Directed 2-partite network (top) of people-in-texts. The network is a subset of the core component of the 3-partite network shown in Figure 4, filtered to show only people and texts active in at least one edge signalling that a person was in a place (Network size: 27 nodes [7 texts, 20 individuals] connected by 47 edges [attestations]. Node colour: text [red], individual [light pink]. Node size: in-degree. Edge colour: different places. Layout: ForceAtlas2); directed weighted 2-partite network (bottom) of people-in-places. The network is based on data contained in Figure 5 (top) but reorganised so people are linked to the places they are revealed to have been in (Network size: 28 nodes [8 places, 20 individuals] connected by 24 weighted edges [in place]. Import strategy: sum. Node colour: place [purple], individual [light pink]. Node size: in-degree. Edge colour: black. Layout: ForceAtlas2). Graphs created by the author in Gephi.

Again, the presence of parallel edges does, however, obscure the picture. This is evident by the men with the three highest in-degree scores (i.e. Patron [7], Toubias [7], and Herakleides [6]) being linked to a single text each. Toubias we know from TM_665 (the contract used as an example above); Patron and Herakleides are the captains of the ships importing goods at Pelousion, as recorded in TM_673 (see Section 4.3). Recording parallel edges can be useful in that they enable the researcher to attribute the relationships with a range of contextual information that can ease the task of returning to the sources as part of the analytical and interpretative stages of the network research. At the same time, they are often problematic in that they affect the mathematical measures. Since Gephi places parallel edges on top of each other, they can also be difficult to spot and study in the interactive interface, and are easily lost in the static visualisations we publish.

In practice, such issues can be (partially) overcome by also creating a version of the network, in which parallel edges are removed or merged. Early explorations, like the ones presented here, can be extremely valuable in that they allow the network researcher to test hypotheses, play with the data, and adjust the methodology to be applied. For example, if the aim is to track the movements of ancient people, one may assume that a network linking persons directly to the locations the ancient sources reveal them to have visited might be more useful than this 2-partite affiliation network. To test the potential of such a model we can consider whether the data at hand already allows for such graphs to be easily created.

Taking a closer look at the data “behind,” Figure 5 (top) reveals that such a network can (relatively) easily be created from it – by renaming column headings so that the persons become the “source” nodes, the column with unique TM place IDs revealing which locations the persons were in become the “target” nodes, and the text references are reframed as edge attributes. Although it might prove useful to also model a version with parallel edges (to retain the contextual information of each attestation), importing the restructured dataset with the import strategy “sum” will convert parallel edges to edge weights, thus transforming our unweighted network to a weighted graph (Figure 5, bottom). In this model, edges are directed from the people to the places they visited or lived, so that in-degree centrality can now be used to show the relative frequency by which any person mentioned in the Zenon papyri is said to have been there.

As a final example, I will direct the reader’s attention to the connected components positioned in the upper left corner of Figure 5 (top and bottom), respectively. Only in the latter is it easily spotted that a fourth person, who is not attested in the account concerning imported goods (TM_673), is also said to have been in Pelousion. This is Andronikos, an oikonomos based in Pelousion. According to a letter from Apollonios to Zenon (TM_2019), Apollonios had asked to rent a ship for Zenon from him (Durand, 1997, pp. 105–106).

Increasing the sample size will add further examples. As a case in point, this Andronikos is also mentioned in a letter written by Moschos to Zenon on 21 July 257 BCE (TM_736), which is not included in this test case but forms part of the author’s larger Zenon project. Still, it is already clear that the scarcity of spatial data incorporated into the networks shown in Figure 5 does not give justice to the wealth of information preserved in the studied documents. Depending on the aims of the study, one might for example find that loosening the criteria by which a person is recorded as being “in (place)” might be more useful. Linking people mentioned in the accounts related to the longer and shorter trips with the cities the travelling groups visited (TM_666 and TM_668) would, for example, change the picture dramatically. While doing so might prove useful, the more information that is subject to interpretation one adds to the network models, the more tiresome the data collection process and the greater the risk of disturbing the “real” picture reflected in the written or archaeological record. As so often in network science, determining whether such efforts are worthwhile will depend on the sources and questions to be asked of them.

4.5 Lessons Learned From the Test Case

When methods of data collection, processing, and analysis are developed or adapted for the case at hand, testing one’s methodology on a small dataset can prove beneficial. In addition to ensuring that everything works as intended, such explorations can give useful insight into the potentials and limitations of the dataset in its current form, and suggest ways to improve it.

On the one hand, the test case presented in this article served to indicate the degree to which the Zenon archive can be meaningfully modelled and explored with methods of network science and SNA. More specifically, it suggested how integrating a third node type (the places) into the network shown in Figure 1 can help the author better understand the nature of the sources, but also warned that parallel edges might be best removed prior to formal network analysis since they skew the picture by affecting network measures.

For analysing 3-partite networks, available metrics must be selected and applied with care. Still, as a research tool, the author finds it useful to keep and visualise everything in one whole network. Above all, such inclusive models can offer the researcher a means to explore the retrieved data and identify relevant cases and text groups for exploring different questions, that can subsequently be filtered, re-organised, or analysed as different network models, with unnecessary elements removed.

On the other hand, the early exploration helped the author test the feasibility of her initial methodology with regard to recording geographical information. A point worth stressing is that the current method of data collection proved too time-consuming for the benefits to outweigh the costs. Should such information be added for the remaining 1,809 documents of the archive, also retrieving some information on the places mentioned in the ancient texts (from TM or elsewhere) through a semi-automated data collection process seems essential.

Finally, the test case proved useful for evaluating the ways in which spatial data is currently conceptualised and recorded in the project’s database. From a spatial perspective, the relevance of recording latitude and longitude coordinates as place node attributes quickly became evident, since qualifying such nodes with geodata would for example enable filtered networks of places, or places-in-texts, to be organised according to the place nodes’ geographical locations.

5 Conclusion and Future Perspectives

Approaching the Zenon archive with formal network analysis will surely become more interesting as the datasets grow. For example, many letters from the next phase of Zenon’s career, during which he followed Apollonios on inspection tours in Egypt, have dockets specifying where the correspondence was received added to the verso (esp. Edgar, 1918, p. 161). Mapping and studying large quantities of such details as k-partite and 1-partite networks should enable me to track and study some of Zenon’s, but also other persons, animals, and materials’ movements through space.

The project’s 3-partite affiliation networks can reveal many characteristics of the sources, as well as the persons and places mentioned in them. Currently, people and locations are on occasion linked in that place IDs also qualify individuals or the edges that link them to ancient texts. It should, however, be remembered that these models remain affiliation networks that are based on attestations. Above all, they can thus serve as navigation maps, guiding the researcher through the masses of data by means of visual exploration and formal analysis of the network data that make up the whole networks, or subsets of them.

By modelling information preserved in the far larger corpus that is the Zenon archive, one can shed light on complex systems of trade, transport, control, and administration, but also on the significance, function, and position of specific locations and agents entangled in, and interacting with, them. For the purpose of studying how people, places, and commodities were linked in antiquity, I modelled only data explicitly mentioned in the selected sources (for a different approach, see e.g. Seland, 2016). Moving forwards, it would also be useful to test how adhering to a more inclusive approach – for example, adding implicit relational bonds or also modelling unnamed people and places – would affect the networks (a separate article exploring the impact of unnamed persons and groups is underway, as Tambs, forthcoming).

Since the Zenon archive was reconstructed in modern times, the boundary of the text group remains fuzzy. Of the 1845 text included in the author’s Zenon project, TM classifies the relation of 16 to the archive as “uncertain,” 3 as “related,” and 4 as “erroneous.” For a future study, one could also try using such k-partite network data (or subsets of it) to locate and study the network position of the nodes representing these less securely related texts to the rest. Combined with methods of attribute analysis, literary review, close reading, and museum archaeology, their level of integration in the network might be taken as an argument for or against the notion that they formed part of the same ancient archive.

Similarly, formal network measures can be used to identify structurally meaningful communities within a network that might not be easily detectable without computational tools. For example, Wagner et al. (2013, pp. 125–128) showed how running the Girvan-Newman algorithm (Girvan & Newman, 2002) on 2-partite (persons-in-texts) data representing a subset of the Murašû archive enabled them to identify two clearly distinguished chronological phases (and some meaningful outliers) in their affiliation network. They present a simple method they propose can aid researchers in disambiguating individuals with partially lost names,[9] suggesting relative dates for undated texts, etc. (for another example, see Maiocchi, 2016). Initial exploration of the data at hand suggests that the present dataset is less suitable for such pursues,[10] but especially for the later Zenon papyri – which are more numerous, span a greater number of years, and document activities that are less geographically dispersed – it would be interesting to check whether their workflow can also be used to propose relative dates for Zenon papyri with unknown dates.

Network science offers practical and mathematical tools for conducting such research, but also theoretical assumptions that can suggest how and why relationships matter, or why certain network positions are favourable or unfavourable within a given system. For SNA, we must acknowledge that the theoretical backbone, but also the most commonly applied measures were developed for the analysis of networks with social actors (persons, organisations, firms, etc.). In this respect, the interpersonal networks created under the author’s Zenon project are expected to be most useful for increasing our understanding of the conditions under which the ancient subjects lived, and the workings of the socio-economic systems they engaged with. The discussed network types thus serve fundamentally different purposes, offering different yet complimentary guiding lights for the researcher fumbling his or her way through vast amounts of complex relational data.

Abbreviations

- P. Cairo Zen.

-

Catalogue général des antiquités égyptiennes du Musée du Caire

- P. Iand. Zen.

-

Die Giessener Zenonpapyri

- P. Lond.

-

Greek Papyri in the British Museum

- P. Mich. Zen.

-

Michigan Papyri

- P. Zen. Pestm.

-

Greek and Demotic Texts from the Zenon Archive

- P.

-

Papyrus

- PSI

-

Papiri greci e latini

- SB

-

Sammelbuch griechischer Urkunden aus Aegypten

- SNA

-

Social network analysis

- TM

-

Trismegistos (www.trismegistos.org)

- TM_###

-

Trismegistos text id

- TM_Geo_###

-

Trismegistos place id

- TM_Per_###

-

Trismegistos person id

Acknowledgements

I thank the organisers of the “Network Perspectives in the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East and Eastern Mediterranean” workshop – Dr. Maria-Gabriella Micale, Prof. Dr. Antti Lahelma, and Dr. Helen Dawson – for including me in the workshop and proceedings, and Dr. Thomas Christiansen for comments and corrections to the first draft. I am also grateful to the Trismegistos team, and to Dr. Fernanda Alvares Freire for sharing her “attestation per document” python code. Finally, I thank the two anonymous reviewers for improving the article with their constructive comments and suggestions.

-

Funding information: The research presented in this article was carried out under the Centre of Excellence in Ancient Near Eastern Empires (ANEE, Team 1), which is funded by the Research Council of Finland (decision number 352747) and hosted by the University of Helsinki. The larger Zenon project is now supported by the Kone Foundation. The Open Access status of this article has received funding from the Centre of Excellence in Ancient Near Eastern Empires, funded by the Research Council of Finland (decision number 352748).

-

Author contributions: The author confirms the sole responsibility for the conception of the study, presented results, and manuscript preparation.

-

Conflict of interest: The author states no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: Raw data were collected from Trismegistos in the spring/summer of 2021, with the “attestation per document” python webscraper developed by Fernanda Alvares Freire (link below). For the sake of transparency, supporting material (high-resolution images, graph files), are shared via Zenodo: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13963730.

Online Resources and Software:

- –

-

Attestation per document: www.github.com/fernandaalvaf/Attestation-per-Document.

- –

-

Gephi: www.gephi.org/.

- –

-

Trismegistos: www.trismegistos.org.

- –

-

Trismegistos Texts: www.trismegistos.org/tm/index.php.

- –

-

Trismegistos People: www.trismegistos.org/ref/index.php.

- –

-

Trismegistos Places: www.trismegistos.org/geo/index.php.

Appendix A Glossary of Technical Terms

| 1-partite network | A network in which all nodes represent a single node type (e.g. individuals). Also called monopartite or 1-mode |

| 2-partite network | A network with two distinct node types (e.g. individuals and texts). Also called bipartite or 2-mode |

| 3-partite network | A network with three distinct node types (e.g. individuals, places, and texts). See also k-partite network |

| Affiliation network | A network with more than one node type, in which the edges represent an affiliation (e.g. attestation in ancient documents) |

| Average degree | Global measure of the average degree centrality score of the nodes in a network. See also degree centrality |

| Betweenness centrality | Point centrality measure that calculates how often a node appears on the shortest path between pairs of other nodes in the network |

| Clique | A maximally connected part of a network, meaning that all nodes in the clique are connected to every other node in the clique |

| Connected component | A set of nodes in which every node can reach all other nodes through a continuous path of edges. See also isolate, dyad, core component, and whole network |

| Core component | The largest connected component of a whole network with several connected components. Also called the main or giant component. See also isolate, dyad, connected component, and whole network |

| Degree centrality | Point centrality measure that calculates the number of edges a node is involved in. See also in-degree and out-degree centrality |

| Directed edge | A relational tie with an inherent direction. Also called arc. In network visualisations, directed edges are typically represented by arrows. See also edge and undirected edge |

| Dyad | A connected component consisting of a single pair of nodes. See also isolate, connected component, core component, and whole network |

| Edge | A relational tie linking a pair of nodes. See also directed edge and undirected edge |

| Edge attribute | Information qualifying an edge (such as the date of a text) |

| Edge-list | The dataset with information on the studied relationships. In addition to the required source and target columns, it can include various edge attributes |

| In-degree centrality | Point centrality measure calculating the number of directed edges that point towards a given node. See also out-degree and degree centrality |

| Interpersonal network | A social network of human actors linked by interpersonal relationships |

| Isolate | A node that is disconnected from all other nodes in the network and therefore has a degree centrality of 0 |

| k-partite network | A network with several node types (with k referring to the number of distinct node types, or modes) |

| Mode | In network jargon, mode refers to the node types a network model contains |

| Network position | A node’s network position is its structural position in the network |

| Node | A studied entity. In network visualisations, typically represented by a dot |

| Node attribute | Information qualifying a node (such as the coordinates of a place) |

| Node-list | The dataset with information on the studied entities. In addition to the required unique ID, it can include various node attributes |

| Undirected edge | A relational tie with no inherent direction. In network visualisations, typically represented by a line. See also edge and directed edge |

| Out-degree centrality | Point centrality measure calculating the number of directed edges that point away from a given node. See also in-degree and degree centrality |

| Parallel edges | Multiple edges of the same kind linking one pair of nodes. Parallel edges cause problems for the network analysis and are difficult to visualise. Therefore, they are often better merged or converted (e.g. to edge weights) |

| Source | In the edge list, the “source” column contains the unique ID of the source node. If the network is directed, this will be the node on the giving end of the directed edge |

| Target | In the edge list, the “target” column contains the unique ID of the target node. If the network is directed, this will be the node on the receiving end of the directed edge |

| Weight | A value signalling the strength of an edge (e.g. frequency of occurrence, or the distance between two places) |

| Whole network | The entire graph, consisting of one or more connected components. See also isolate, dyad, connected component, and core component |

Appendix B Sigla of Texts Included in the Case Study

TM_665/P. Cairo Zen. 1 59003

TM_666/P. Cairo Zen. 1 59004

TM_667/P. Cairo Zen. 1 59005

TM_668/P. Cairo Zen. 1 59006

TM_669/P. Cairo Zen. 1 59008

TM_670/PSI 6 628 + P. Cairo Zen. 1 59009 + P. Cairo Zen. 4 p. 285

TM_672/P. Cairo Zen. 1 59011

TM_673/P. Cairo Zen. 1 59012

TM_674/P. Cairo Zen. 1 59013

TM_675/SB 26 16505

TM_676/P. Cairo Zen. 1 59015

TM_677/P. Cairo Zen. 1 59016

TM_678/P. Cairo Zen. 1 59018

TM_1172/P. Cairo Zen. 4 59536

TM_1299/P. Cairo Zen. 4 59671

TM_1301/P. Cairo Zen. 4 59673

TM_1325/P. Cairo Zen. 4 59698

TM_1426/P. Cairo Zen. 5 598001

TM_1427/P. Cairo Zen. 5 59802

TM_1701/P. Lond. 7 2141

TM_1708/P. Lond. 7 2148

TM_1863/P. Zen. Pestm. 32

TM_1890/P. Iand. Zen. 51 + 52

TM_1906/P. Zen. Pestm. 76 a

TM_1910/P. Mich. Zen. 4

TM_2019/PSI 4 322

TM_2021/PSI 4 324

TM_2022/PSI 4 325

TM_2173/PSI 6 553

TM_2174/PSI 6 554

TM_2237/PSI 6 632

TM_2293/P. Cairo Zen. 1 59002

TM_2372/P. Zen. Pestm. 76 b

TM_2377/P. Lond. 7 1930

TM_2378/P. Lond. 7 1932

TM_2436/PSI 7 863 h

Appendix C Network Projection of Bipartite Network Data

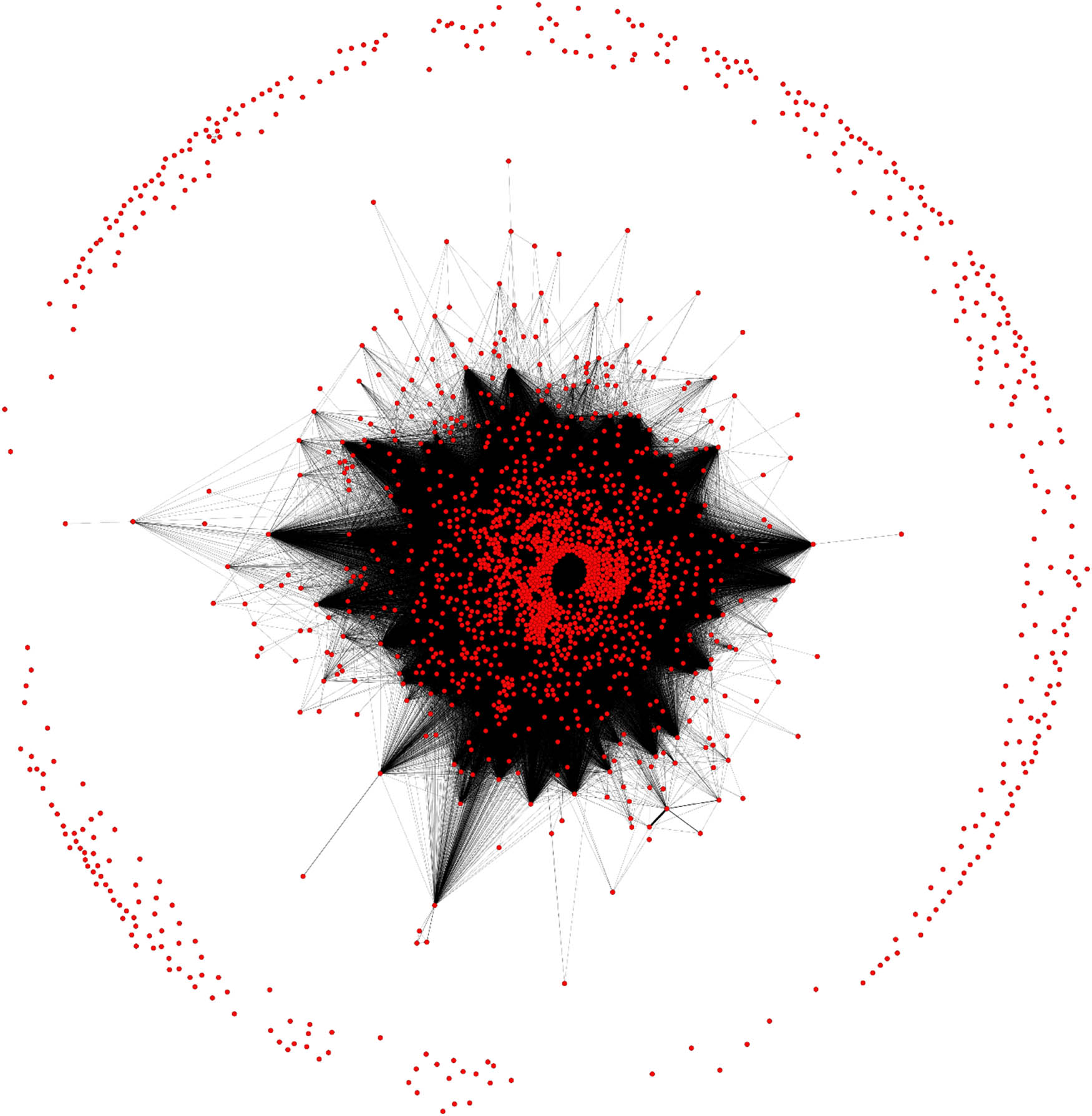

To explore the potential of network projection for the large 2-partite network visualised in the main article as Figure 1, the author transformed this model (Figure A1) into 1-partite networks of people (Figure A2) and texts (Figure A3), respectively.

“Network a” is the 2-partite affiliation network of individuals (black nodes) linked to ancient texts (red nodes) by edges signalling that the given person is attested in the given text. Layout: ForceAtlas2. Graph by author, created in Gephi.

“Network b” is the 1-partite network projection in which pairs of individuals (black nodes) are linked if they are mentioned together in one or more ancient texts (here represented by a red edge). Nodes are positioned as in Figure A1. Graph by author, created in Gephi.

“Network c” is the 1-partite network projection in which pairs of ancient texts (red nodes) are linked if at least one individual is attested in both texts (here signalled by black edges). Nodes are positioned as in Figure A1. Graph by author, created in Gephi.

Table A1 presents some network characteristics of the three models. “Network a” is the 2-partite network of people-in-texts (Figure A1), “Network b” is the projection network of people linked by co-attestation (Figure A2), and “Network c” is the text-projection, in which text nodes are directly linked by the shared people they mention (Figure A3).

Network characteristics of the original and compressed models

| Measure | Network a (Figure A1) | Network b (Figure A2) | Network c (Figure A3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of nodes | 5,831 (persons and texts) | 3,986 (persons) | 1,845 (texts) |

| Number of edges | 1,222 | 65,947 | 472,404 |

| Connected components | 414 | 182 | 406 |

| Average degree | 1,925 | 33,089 | 512,091 |

| Average weighted degree | 1,925 | 87,694 | 1,477,298 |

| Densitya | 0.001 | 0.008 | 0.278 |

aFor calculating the network density, all networks were interpreted as undirected.

One observation that the network projection approach makes clear is that in the compressed people-network, several groups that are tightly linked to one another but disconnected from the core component are formed, whereas in the text-projection, the vast majority of the texts that are excluded from the core component are isolates. In fact, only four smaller components are formed: a small group of four texts (TM_711, TM_713, TM_1913, and TM_1914) and three dyads (TM_1397, and TM_2195; TM_1433, and TM_1434; TM_1307, and TM_1702). Moreover, in both projection networks, all smaller connected components are maximally dense, since all nodes are liked to every other node in the clique.

References

Bastian, M., Heymann, S., & Jacomy, M. (2009). Gephi: An open source software for exploring and manipulating networks. Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media (361–362). doi: 10.1609/icwsm.v3i1.13937.Search in Google Scholar

Borgatti, S. P., Everett, M. G., & Johnson, J. C. (2013). Analyzing social networks. SAGE.Search in Google Scholar

Broux, Y., & Depauw, M. (2015). Developing onomastic gazetteers and prosopographies for the ancient world through named entity recognition and graph visualization. In L. M. Aiello & D. McFarland (Eds.), Social Informatics Socinfo 2014 International Workshops, Barcelona, Spain, November 10, 2014 (pp. 304–313). Springer.10.1007/978-3-319-15168-7_38Search in Google Scholar

Brughmans, T., & Peeples, M. A. (2023). Network science in archaeology. Cambridge University Press.10.1017/9781009170659Search in Google Scholar

Brughmans, T., & Tambs, L. (forthcoming). Network Approaches to Near Eastern Archaeology. In E. Bennett, L. Tambs & J. Valk (Eds.), Networks in Ancient Near Eastern Studies. HUP.Search in Google Scholar

Chang, R. L. (2019). Philadelphie (No. 17124; BIFAO-Suppl. 118, pp. 153–161). l’Institut français d’archéologie orientale.Search in Google Scholar

Chang, R.-L., Awad Mohamed, S., Hartenstein, C., Marchand, S., & Nannucci, S. (2020). Philadelphie (2019). Bulletin Archéologique Des Écoles Françaises à l’étranger, 1–11. doi: 10.4000/baefe.1023.Search in Google Scholar

Chang, R.-L., Empereur, J.-Y., Hartenstein, C., Huang, C.-J., Hussein, A., Kruse, T., Marchand, S., Nannucci, S., & El-Shahat Mohamed Mahmoud, Y. (2023). Philadelphia (2022): Kūm al-Ḫarāba al-Kabīir Ǧirza. Bulletin Archéologique Des Écoles Françaises à l’étranger, 1–17. doi: 10.4000/baefe.8176.Search in Google Scholar

Chang, R.-L., Nannucci, S., Mohamed, S. A., Marchand, S., Mahmoud, Y. E. S. M., Kačičnik, M., Gaber, M., Hussein, A., Al-Amir, H., Kan, Y.-C., & Crépy, M. (2024). Philadelphia (2023): Kūm al-Ḫarāba al-Kabīir Ǧirza. Bulletin Archéologique Des Écoles Françaises à l’étranger, 1–15. doi: 10.4000/11sxj.Search in Google Scholar

Cline, D. H., & Cline, E. H. (2015). Text messages, tablets, and social networks. In J. Mynářová, P. Onderka, & P. Pavúk (Eds.), There and back again – The crossroads II. Proceedings of an international conference held in Prague, September 15–18, 2014 (pp. 17–44). Charles University, Faculty of Arts.Search in Google Scholar

Collar, A., Coward, F., Brughmans, T., & Mills, B. J. (2015). Networks in archaeology: Phenomena, abstraction, representation. Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory, 22(1), 1–32. doi: 10.1007/s10816-014-9235-6.Search in Google Scholar

Crabtree, S. A., & Borck, L. (2019). Social networks for archaeological research. In Encyclopedia of global archaeology (pp. 1–12). Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-51726-1_2631-2.Search in Google Scholar

Depauw, M., & Gheldof, T. (2014). Trismegistos: An interdisciplinary platform for ancient world texts and related information. In Ł. Bolikowski, V. Casarosa, P. Goodale, N. Houssos, P. Manghi, & J. Schirrwagen (Eds.), Theory and practice of digital libraries. TPDL 2013 selected workshops (pp. 40–52). Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-08425-1.Search in Google Scholar

Durand, X. (1997). Des Grecs en Palestine au IIIe siècle avant Jésus-Christ. Le dossier syrien des archives de Zénon de Caunos (261–252). J. Gabalda.Search in Google Scholar

Dutrey, C. (2021). Distribution de l’information et stratégies relationnelles dans le corpus de correspondances amarniennes: Approche par l’analyse de réseaux. Journal of Historical Network Research, 6, 1–40. doi: 10.25517/JHNR.V6I1.85.Search in Google Scholar

Edgar, C. C. (1917). On the dating of early Ptolemaic Papyri. Annales Du Service Des Antiquités de l’Égypte, 17, 209–223.Search in Google Scholar

Edgar, C. C. (1918). Selected Papyri from the archives of Zenon: (Nos. 1-10). Annales Du Service Des Antiquités de l’Égypte, 18, 159–182.Search in Google Scholar

Edgar, C. C. (1931a). Zenon Papyri. Catalogue Général des Antiquités Égyptiennes du Musée du Caire. Nos 59532–59800 (Vol. 4). Imprimerie de l´Institut Francais d´Archéologie Orientale.Search in Google Scholar

Edgar, C. C. (1931b). Zenon Papyri in the University of Michigan Collection. University of Michigan Press.10.3998/mpub.12946961Search in Google Scholar

Fournet, J. L. (2018). Archives and libraries in Greco-Roman Egypt. In A. Bausi, C. Brockmann, M. Friedrich, & S. Kienitz (Eds.), Manuscripts and archives: Comparative views on record-keeping (pp. 171–199). De Gruyter.10.1515/9783110541397-006Search in Google Scholar

Gee, J. (2020). Philadelphia: A preliminary report. In K. Muhlestein, B. Jensen, & K. V. L. Pierce (Eds.), Excavations at Fag el-Gamous and the Seila Pyramid (pp. 318–335). Brill.10.1163/9789004416383_016Search in Google Scholar

Gehad, B. (2024). A report on a Mid-Ptolemaic Graveyard with Gable-roof Coffins from Ancient Philadelphia. In BIFAO (Vol. 124, pp. 251–276). Institut français d’archéologie orientale.10.4000/129n6Search in Google Scholar

Gehad, B., Corcoran, L. H., Ibrahim, M., Hammad, A., Samah, M., Abdo, A. A., & Fekry, O. (2022a). Newly discovered Mummy portraits from the Necropolis of Ancient Philadelphia – Fayum. In BIFAO (Vol. 122, pp. 245–264). Institut français d’archéologie orientale.10.4000/bifao.11727Search in Google Scholar

Gehad, B., Hammad, A., Ibrahim, M., Samah, M., Hussein, M., Badr El Din, D., Baetens, G., Mostafa, M., & Atef, M. (2023). Ancient Philadelphia Necropolis: Understanding Burial Customs in Fayum during the Ptolemaic and Roman Periods. In O. el-Aguizy & B. Kasparian (Eds.), Proceedings of the Twelfth International Congress of Egyptologists. ICE XII, 3rd–8th November 2019, Cairo, Egypt (Vol. 1, pp. 111–126).Search in Google Scholar

Gehad, B., Hammad, A., Saad, A., Samah, M., & Hussein, M. (2020). The Necropolis of Philadelphia: Preliminary results. In C. E. Römer (Ed.), News from Texts and Archaeology. Acts of the 7th International Fayoum Symposiu 29 October–3 November 2018 in Cairo and the Fayoum (pp. 35–58). Harrassowitz Verlag.Search in Google Scholar

Gehad, B., Mostafa, M., Baetens, G., & Hussein, M. (2022b). Understanding daily life through the afterlife: A case study from ancient Philadelphia’s Necropolis. In J. Sigl (Ed.), Daily life in ancient Egyptian settlements (Vol. 47, pp. 119–129). Harrassowitz.Search in Google Scholar

Girvan, M., & Newman, M. E. J. (2002). Community structure in social and biological networks. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 99(12), 7821–7826. doi: 10.1073/pnas.122653799.Search in Google Scholar

Goff, M. J. (2016). The Hellenistic period. In S. Niditch (Ed.), The Wiley Blackwell Companion to Ancient Israel (pp. 260–276). John Wiley & Sons. doi: 10.1002/9781118774199.ch13.Search in Google Scholar

Gonçalves, C. (2021a). Social Network Analysis and Kinship in the Old Babylonian Diyala. Fathers and Sons in the Archive of Nūr-Šamaš. H2D|Revista de Humanidades Digitais, 3(1), 1–11. doi: 10.21814/h2d.3470.Search in Google Scholar

Gonçalves, C. (2021b). Social network analysis, homonyms, and aliases in the Old Babylonian Diyala: A Study of the Archive of Nūr-Šamaš. In C. Gonçalves & C. Michel (Eds.), Interdisciplinary Research on the Bronze Age Diyala. Proceedings of the Conference Held at the Paris Institute for Advanced Study, 25–26 June, 2018 (pp. 83–101). Brepolis Publishers.10.1484/M.SUBART-EB.5.126529Search in Google Scholar