Cones with a three-fold symmetry constructed from three hydrogen bonded theophyllinium cations that coat [FeCl4]− anions in the crystal structure of tris(theophyllinium) bis(tetrachloridoferrate(III)) chloride trihydrate, C21H33Cl9Fe2N12O9

Abstract

C21H33Cl9Fe2N12O9, trigonal,

Table 1 contains crystallographic data and Table 2 contains the list of the atoms including atomic coordinates and displacement parameters.

Data collection and handling.

| Crystal: | Yellow block |

| Size: | 0.35 × 0.25 × 0.17 mm |

| Wavelength: | Mo Kα radiation (0.71073 Å) |

| μ: | 1.40 mm−1 |

| Diffractometer, scan mode: | Xcalibur, ω |

| θ max, completeness: | 29.5°, 99% |

| N(hkl)measured, N(hkl)unique, R int: | 20742, 3677, 0.029 |

| Criterion for I obs, N(hkl)gt: | I obs > 2 σ(I obs), 3238 |

| N(param)refined: | 177 |

| Programs: | Bruker [1], CrysAlisPRO [2], SHELX [3], [4], [5], [6], Diamond [7] |

Fractional atomic coordinates and isotropic or equivalent isotropic displacement parameters (Å2).

| Atom | x | y | z | U iso*/U eq |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fe1 | 0.333333 | 0.666667 | 0.47408 (2) | 0.01383 (8) |

| Fe2 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.39968 (2) | 0.01752 (9) |

| Cl1 | 0.333333 | 0.666667 | 0.41848 (2) | 0.02115 (12) |

| Cl2 | 0.42976 (3) | 0.58229 (3) | 0.49222 (2) | 0.02500 (9) |

| Cl3 | 0.18163 (3) | 0.08408 (3) | 0.38067 (2) | 0.02306 (9) |

| Cl4 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.45426 (2) | 0.03767 (17) |

| Cl5 | 0.666667 | 0.333333 | 0.40175 (2) | 0.03039 (15) |

| O1 | 0.34531 (9) | 0.41402 (9) | 0.37751 (3) | 0.0228 (2) |

| O2 | 0.18914 (9) | 0.28864 (9) | 0.48310 (2) | 0.0247 (2) |

| O1W | 0.57526 (11) | 0.46537 (11) | 0.35538 (3) | 0.0289 (2) |

| H1W | 0.596 (2) | 0.422 (2) | 0.3637 (7) | 0.058 (5)* |

| H2W | 0.511 (2) | 0.428 (2) | 0.3528 (7) | 0.058 (5)* |

| N1 | 0.16736 (9) | 0.39603 (9) | 0.38766 (3) | 0.0139 (2) |

| N2 | 0.26273 (10) | 0.34311 (10) | 0.42920 (3) | 0.0171 (2) |

| N3 | −0.02183 (10) | 0.30174 (10) | 0.45749 (3) | 0.0181 (2) |

| H3 | −0.0446 (19) | 0.2738 (19) | 0.4766 (6) | 0.043 (6)* |

| N4 | −0.02070 (10) | 0.36870 (10) | 0.40696 (3) | 0.0154 (2) |

| H4 | −0.0464 (17) | 0.3875 (17) | 0.3886 (5) | 0.036 (5)* |

| C1 | 0.26364 (11) | 0.38628 (11) | 0.39674 (3) | 0.0163 (2) |

| C2 | 0.17838 (12) | 0.31621 (11) | 0.45431 (3) | 0.0171 (3) |

| C3 | 0.08124 (11) | 0.32443 (11) | 0.44209 (3) | 0.0153 (2) |

| C4 | 0.08033 (11) | 0.36519 (11) | 0.41067 (3) | 0.0132 (2) |

| C5 | −0.08144 (12) | 0.32858 (12) | 0.43599 (3) | 0.0187 (3) |

| H5 | −0.154287 | 0.320949 | 0.440252 | 0.022* |

| C6 | 0.16445 (12) | 0.44958 (12) | 0.35544 (3) | 0.0176 (3) |

| H6A | 0.234536 | 0.470459 | 0.342899 | 0.026* |

| H6B | 0.159360 | 0.518528 | 0.359754 | 0.026* |

| H6C | 0.097546 | 0.394824 | 0.342575 | 0.026* |

| C7 | 0.36309 (13) | 0.32894 (14) | 0.43785 (4) | 0.0259 (3) |

| H7A | 0.389958 | 0.307835 | 0.417930 | 0.039* |

| H7B | 0.339902 | 0.268463 | 0.454552 | 0.039* |

| H7C | 0.425084 | 0.401252 | 0.446730 | 0.039* |

Source of material

All chemicals except theophyllinium chloride monohydrate were obtained from commercial sources and used as received. Theophyllinium chloride monohydrate was synthesized by isothermal evaporation of theophylline in concentrated hydrochloric acid.

The title compound was synthesized by dissolving 0.20 g (0.9 mmol) theophyllinium chloride monohydrate and 0.23 g (0.6 mmol) iron(III) chloride hexahydrate in 5 mL concentrated hydrochloric acid. The solution was left at room temperature for a few weeks, which resulted in the formation of yellow crystals.

Experimental details

A single crystal of the title compound was directly selected from the mother liquor and rapidly transferred to the Xcalibur four-circle diffractometer equipped with an EOS detector [2]. An absorption correction (Multiscan method) was applied [2]. The structure solution and the refinement were successfully carried out using the SHELX program system [3], [4], [5], [6]. The figure was created using the DIAMOND software package [7].

All hydrogen atoms were seen in the Fourier map after all non-hydrogen atoms were located. C-bound hydrogen atoms were included using a riding model. Coordinates of nitrogen-bound hydrogen atoms were refined freely.

The Raman spectra were measured using a Bruker MULTIRAM spectrometer (Nd: YAG-laser at 1064 nm; InGaAs detector) with an apodized resolution of 8 cm−1 in the region of 4000–70 cm−1; using the OPUS software [1].

Comment

Introduction

The natural product theophylline (systematic name: 1,3-dimethyl-3,7-dihydro-1H-purine-2,6-dione) was first described by Kossel in 1888 [8, 9]. He was able to isolate theophylline from an extract of leaves from the tea plant, which explains where the name of this compound originates from. There is still interest in this compound in general and the corresponding solid state phases [10, 11] as well as in the corresponding co-crystals [12], [13], [14], [15]. Nowadays theophylline is sometimes used as pharmaceutical agent due to its effects on the respiratory system [16], [17], [18], [19]. Interestingly, theophylline was also tried in COVID-19 therapy [20]. We have already shown that N-protonated cations of naturally occurring bases like nicotine [21], [22], [23], caffeine [24, 25] and theophylline [26], [27], [28] are excellent tectons to construct hydrogen bonded networks. A database check (Cambridge structural database [29]) on structures that contain a theophyllinium cation yielded only a limited number of entries [28]. [FeCl4]– containing compounds are of general interest as some of them are known to undergo phase transitions what may change dramatically their physical properties [30], [31], [32]. In detail [FeCl4]− containing compounds may have magnetic properties [33], can be used as ionic liquids with magnetic properties [34, 35] and are in general the source of a broad scope of new materials [36], [37], [38]. It has already been shown, that the formation of double salts containing [FeCl4]− and chloride anions is a prominent feature of salts containing N-protonated organic cations [39], [40].

Structural comments

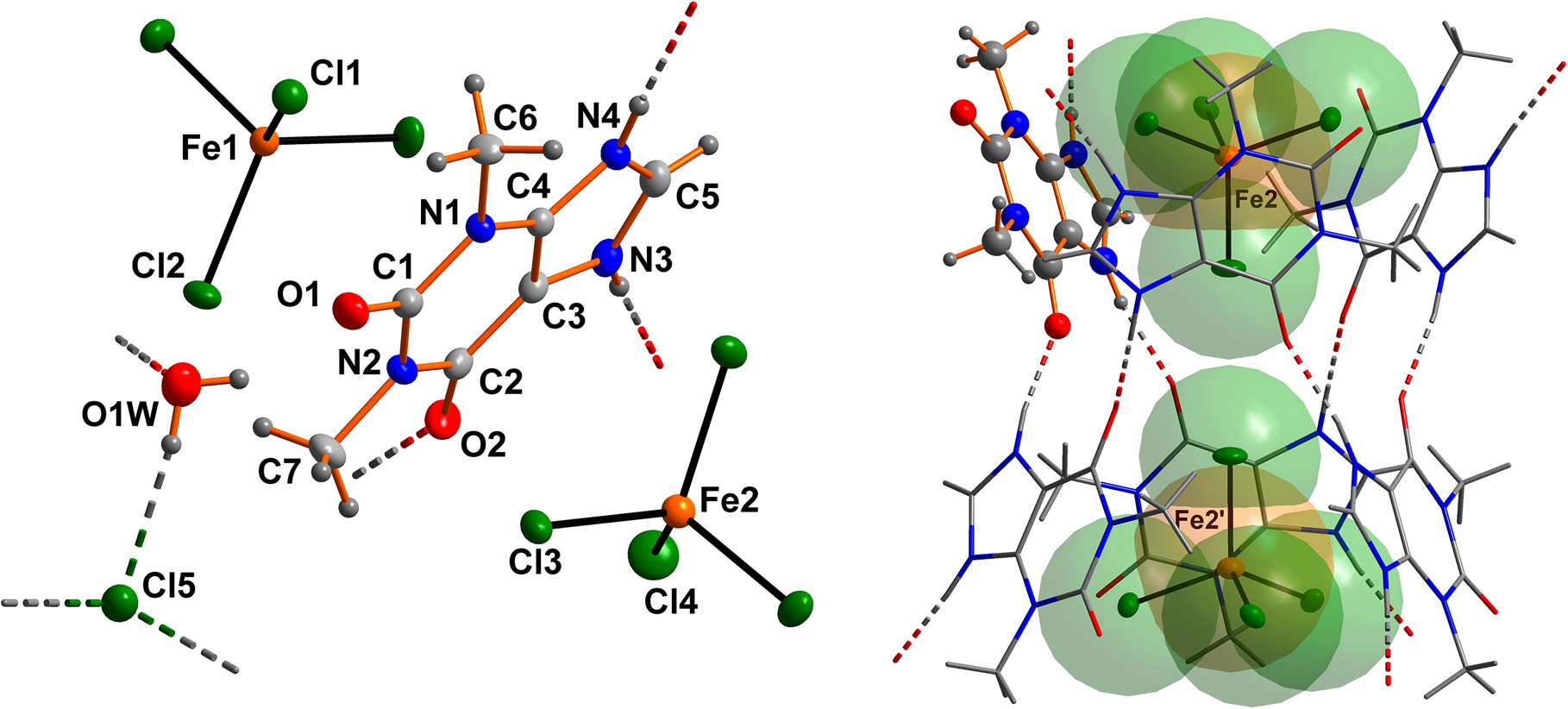

The asymmetric unit of the title compound consists of one N-protonated theophyllinium cation (TheoH+) residing on a general position, two thirds of [FeCl4]− anions, located on the three-fold axes, the isolated chloride anion also located on the three-fold axis of the space group and one water molecule in a general position. The asymmetric unit (labeled atoms) is shown in the left-hand side of the figure. Multiplication by three of this asymmetric unit gives the composition of the title double salt: tris(theophyllinium) bis(tetrachloridoferrate(III)) chloride trihydrate.

Bond lengths within the TheoH+ cation are all in the expected ranges [26], [27], [28]. The Fe–Cl distances in both crystallographically independent anions range from 2.1570(7) to 2.2084(4) Å and the angles range from 109.044(12)° to 109.809(13)°. These parameters are all in the expected ranges [39], [40], [41], [42].

Each theophyllinium cation is connected to two neighboring cations by classical NH⃛O hydrogen bonds (see the left part of the figure; N3–H3⃛O2′: N–O distance = 2.6920(15) Å with an angle of 171(2)°; ′ = x−y, x, 1−z). These connections create a double cone, constructed from six cations which coat two [FeCl4]− anions (see the right part of the figure). Two more hydrogen bonds are seen for the TheoH+ cation: a) a connection to a neighboring water molecule by the N4 hydrogen bond donor (N4–H4⃛O1w″: N–O distance = 2.6374(16) Å with an angle of 173.3(19)°; ″ = −x+y, 1−x, z); b) the TheoH+ cation accepts a weak hydrogen bond from a neighboring water molecule O1w–H2w⃛O1: O–O distance = 2.8928(16) Å with an angle of 136(2)°. The isolated chloride anion accepts three crystallographically dependent O–H⃛Cl hydrogen bonds from three surrounding water molecules (O1W–H1W⃛Cl5: Cl–O distance = 3.1537(14) Å with an angle of 163(2)°). The different hydrogen bonds construct a two-dimensional network parallel to the aa′ plane.

The [FeCl4]− anion as a weak hydrogen bond acceptor is not involved in any strong hydrogen bonds in the title structure. This was bound to happen as all classic hydrogen donors in the title structure are already involved in medium-strong hydrogen bonds. Thus we suppose that the shape and the group radius of the [FeCl4]− determines or at least supports the formation of the hydrogen bonded network by non-classical interactions.

Raman spectroscopy

To further characterize the [FeCl4]− anion a Raman spectrum was recorded and compared to the Raman spectrum of theophyllinium chloride monohydrate, which served as starting material. According to Shamir and Sobota [43] the [FeCl4]− anion with local T d symmetry can be characterized through four characteristic vibration bending modes in the range of 400–100 cm−1. A very strong line at 339 cm−1 is caused by the symmetric stretching vibration ν 1(A 1). The asymmetric bending mode ν 4(F 2) is observed as a weak shoulder at 138 cm−1, while the symmetric bending mode ν 2(E) around 110 cm−1 can not be observed due to overlapping of a strong cation vibration. The stretching vibration ν 3(F 2) is observed as a weak and broad line around 400 cm −1 .

Conclusions

We have shown that the shape of the counter anion influences the hydrogen bonding scheme of the theophyllinium sub system [26, 28].

Funding source: Ministry of Innovation, Science and Research of North-Rhine Westphalia

Funding source: German Research Foundation

Award Identifier / Grant number: 208/533-1

Award Identifier / Grant number: 162659349

Funding source: Heinrich-Heine-Universität Düüsseldorf

-

Author contributions: All the authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this submitted manuscript and approved submission.

-

Research funding: This study was funded by the Ministry of Innovation, Science and Research of North-Rhine Westphalia; the German Research Foundation (DFG) for financial support (Xcalibur diffractometer; INST 208/533-1, project no. 162659349); and finally funded by the open access fund of the Heinrich-Heine-Universität Düsseldorf.

-

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare no conflicts of interest regarding this article.

References

1. Bruker OPUS Software for MultiRam Raman Spectrometer, 2012.Suche in Google Scholar

2. Oxford Diffraction. CrysAlisPRO (version 1.171.33.42); Oxford Diffraction Ltd.: Oxford, UK, 2009.Suche in Google Scholar

3. Sheldrick, G. M. A short history of SHELX. Acta Crystallogr. 2008, A64, 112–122; https://doi.org/10.1107/s0108767307043930.Suche in Google Scholar

4. Sheldrick, G. M. SHELXT – integrated space-group and crystal-structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. 2015, A71, 3–8; https://doi.org/10.1107/s2053273314026370.Suche in Google Scholar

5. Sheldrick, G. M. Crystal structure refinement with SHELXL. Acta Crystallogr. 2015, C71, 3–8; https://doi.org/10.1107/s2053229614024218.Suche in Google Scholar

6. Hübschle, C. B., Sheldrick, G. M., Dittrich, B. ShelXle: a Qt graphical user interface for SHELXL. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2011, 44, 1281–1284.10.1107/S0108767319098143Suche in Google Scholar

7. Brandenburg, K. DIAMOND. Visual Crystal Structure Information System (ver. 5.2); Crystal Impact: Bonn, Germany, 2018.Suche in Google Scholar

8. Kossel, A. Ueber eine neue Base aus dem Pflanzenreich. Ber. Dtsch. Chem. Ges. 1888, 21, 2164; https://doi.org/10.1002/cber.188802101422.Suche in Google Scholar

9. Kossel, A. Ueber das Theophyllin, einen neuen Bestandtheil des Thees. Z. Physiol. Chem. 1889, 13, 298–308; https://doi.org/10.1515/bchm1.1889.13.3.298.Suche in Google Scholar

10. Fucke, K., McIntyre, G. J., Wilkinson, C., Henry, M., Howard, J. A., Steed, J. W. New insights into an old molecule: interaction energies of theophylline crystal forms. Cryst. Growth Des. 2012, 12, 1395–1401; https://doi.org/10.1021/cg201499s.Suche in Google Scholar

11. Matsuo, K., Matsuoka, M. Solid-state polymorphic transition of theophylline anhydrate and humidity effect. Cryst. Growth Des. 2007, 7, 411–415; https://doi.org/10.1021/cg060299i.Suche in Google Scholar

12. Darwish, S., Zeglinski, J., Krishna, G. R., Shaikh, R., Khraisheh, M., Walker, G. M., Croker, D. M. A new 1:1 drug-drug cocrystal of Theophylline and Aspirin: discovery, characterization, and construction of ternary phase diagrams. Cryst. Growth Des. 2018, 18, 7526–7532; https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.cgd.8b01330.Suche in Google Scholar

13. Wang, L., Luo, M., Li, J., Wang, J., Zhang, H., Deng, Z. Sweet Theophylline cocrystal with two tautomers of acesulfame. Cryst. Growth Des. 2015, 15, 2574–2578; https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.cgd.5b00207.Suche in Google Scholar

14. McTague, H., Rasmuson, A. C. Nucleation of the theophylline : salicylic acid 1:1 cocrystal. Cryst. Growth Des. 2021, 21, 2711–2719 https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.cgd.0c01594.Suche in Google Scholar

15. Lange, L., Sadowski, G. Polymorphs, hydrates, cocrystals, and cocrystal hydrates: thermodynamic modeling of theophylline systems. Cryst. Growth Des. 2016, 16, 4439–4449; https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.cgd.6b00554.Suche in Google Scholar

16. Persson, C. G. A. Overview of effects of theophylline. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 1986, 78, 780–787; https://doi.org/10.1016/0091-6749(86)90061-8.Suche in Google Scholar

17. Sofian, Z. M., Benaouda, F., Wang, J. T. W., Lu, Y., Barlow, D. J., Royall, P. G., Farag, D. B., Rahman, K. M., Al Jamal, K. T., Forbes, B., Jones, S. A. A Cyclodextrin stabilized spermine tagged drug triplex that targets Theophylline to the lungs selectively in respiratory emergency. Adv. Ther. 2020, 3, 2000153.10.1002/adtp.202000153Suche in Google Scholar

18. Benaouda, F., Jones, S. A., Chana, J., Dal Corno, B. M., Barlow, D. J., Hider, R. C., Page, C. P., Forbes, B. Ion-pairing with spermine targets Theophylline to the lungs via the polyamine transport system. Mol. Pharm. 2018, 15, 861–870; https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.7b00715.Suche in Google Scholar

19. Tanaka, R., Hattori, Y., Otsuka, M., Ashizawa, K. Application of spray freeze drying to theophylline-oxalic acid cocrystal engineering for inhaled dry powder technology. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm. 2020, 46, 179–187; https://doi.org/10.1080/03639045.2020.1716367.Suche in Google Scholar

20. Zhou, C., Gao, C., Xie, Y., Xu, M. COVID-19 with spontaneous pneumomediastinum. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, 510; https://doi.org/10.1016/s1473-3099(20)30156-0.Suche in Google Scholar

21. Reiss, G. J. I5− polymers with a layered arrangement: synthesis, spectroscopy, and structure of a new polyiodide salt in the nicotine/HI/I2 system. Z. Naturforsch. B Chem. Sci. 2015, 70, 735–740; https://doi.org/10.1515/znb-2015-0092.Suche in Google Scholar

22. Reiss, G. J., Sergeeva, A. Hydrogen bonding versus packing effects in the crystal structure of 3-((1R, 2S)-1-methylpyrrolidin-1-ium-2-yl) pyridin-1-ium tetraiodidozincate(II). Z. Kristallogr. N. Cryst. Struct. 2020, 235, 959–962; https://doi.org/10.1515/ncrs-2020-0123.Suche in Google Scholar

23. Reiss, G. J., Sergeeva, A. The crystal structure of 3-((1R,2S)-1-methylpyrrolidin-1-ium-2-yl)pyridin-1-ium tetrachloridocobaltate(II) monohydrate, C10H18Cl4CoN2O. Z. Kristallogr. N. Cryst. Struct. 2017, 232, 159–161; https://doi.org/10.1515/ncrs-2016-0245.Suche in Google Scholar

24. Merkelbach, J., Majewski, M. A., Reiss, G. J. Crystal structure of caffeinium triiodide-caffeine (1/1), C16H21I3N8O4. Z. Kristallogr. N. Cryst. Struct. 2018, 233, 941–944; https://doi.org/10.1515/ncrs-2018-0125.Suche in Google Scholar

25. Reiss, G. J., Majewski, M. A., Merkelbach, J. Higher symmetry at lower temperature: reinvestigation of the historic compound caffeinium triiodide monohydrate. In 26th Annual Conference of the German Crystallographic Society, Essen, Germany. Z. Kristallogr. Suppl. Vol. 38, 2018; pp. 93–94.Suche in Google Scholar

26. Reiss, G. J. A cyclic I102− anion in the layered crystal structure of theophyllinium pentaiodide, C7H9I 5N4O2. Z. Kristallogr. N. Cryst. Struct. 2019, 234, 737–739; https://doi.org/10.1515/ncrs-2019-0082.Suche in Google Scholar

27. Wyshusek, M., Reiss, G. J., Frank, W. The triple salt 2(C7H9N4O2) [MoOCl4(H2O)]· 2(C7H9N4O2)Cl · (H17O8)Cl containing a C2-symmetrical unbranched H+(H2O)8 Zundel type species in a framework composed of Theophyllinium, aquatetrachloridooxidomolybdate and chloride ions. Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 2021, 647, 575–581; https://doi.org/10.1002/zaac.202100007.Suche in Google Scholar

28. Reiss, G. J., Wyshusek, M. The layered crystal structure of bis(theophyllinium) hexachloridostannate(IV), C14H18N8O8SnCl6. Z. Kristallogr. N. Cryst. Struct. 2021, 236, 989–992.10.1515/ncrs-2021-0185Suche in Google Scholar

29. Groom, C. R., Bruno, I. J., Lightfoot, M. P., Ward, S. C. The Cambridge structural database. Acta Crystallogr. B 2016, 72, 171–179; https://doi.org/10.1107/s2052520616003954.Suche in Google Scholar

30. González-Izquierdo, P., Fabelo, O., Beobide, G., Vallcorba, O., Sce, F., Rodríguez Fernández, J., Fernández-Díaz, M. T., de Pedro, I. Magnetic Structure, single-crystal to single-crystal transition, and thermal expansion study of the (Edimim)[FeCl4] halometalate compound. Inorg. Chem. 2018, 57, 1787–1795; https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.inorgchem.7b02632.Suche in Google Scholar

31. Lutz, M., Huang, Y., Moret, M.-E., Klein Gebbink, R. J. M. Phase transitions and twinned low-temperature structures of tetraethylammonium tetrachloridoferrate(III). Acta Crystallogr. C 2014, 70, 470–476; https://doi.org/10.1107/s2053229614007955.Suche in Google Scholar

32. González-Izquierdo, P., Fabelo, O., Beobide, G., Cano, I., Ruiz de Larramendi, I., Vallcorba, O., Fernández, J. R., Fernández-Díaz, M. T., de Pedro, I. Crystal structure, magneto-structural correlation, thermal and electrical studies of an imidazolium halometallate molten salt: (trimim)[FeCl4]. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 11200–11209.10.1039/D0RA00245CSuche in Google Scholar

33. García-Saiz, A., Migowski, P., Vallcorba, O., Junquera, J., Blanco, J. A., González, J. A., Fernández-Díaz, M. T., Rius, J., Dupont, J., Rodríguez Fernández, J., de Pedro, I. A magnetic ionic liquid based on tetrachloroferrate exhibits three-dimensional magnetic ordering: a combined experimental and theoretical study of the magnetic interaction mechanism. Chem. Eur J. 2014, 20, 72–76; https://doi.org/10.1002/chem.201303602.Suche in Google Scholar

34. Xie, Z.-L., Jelicic, A., Wang, F.-P., Rabu, P., Friedrich, A., Beuermann, S., Taubert, A. Transparent, flexible, and paramagnetic ionogels based on PMMA and the iron-based ionic liquid 1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium tetrachloroferrate(III) [Bmim][FeCl4]. J. Mater. Chem. 2010, 20, 9543–9549; https://doi.org/10.1039/c0jm01733g.Suche in Google Scholar

35. Iimori, T., Abe, Y. Magneto-optical spectroscopy of the magnetic room-temperature ionic liquid 1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium tetrachloroferrate. Chem. Lett. 2016, 45, 347–349; https://doi.org/10.1246/cl.151139.Suche in Google Scholar

36. Göbel, R., Xie, Z.-L., Neumann, M., Günter, C., Löbbicke, R., Kubo, S., Titirici, M.-M., Giordano, C., Taubert, A. Synthesis of mesoporous carbon/iron carbide hybrids with unusually high surface areas from the ionic liquid precursor [Bmim][FeCl4]. CrystEngComm 2012, 14, 4946–4951.10.1039/c2ce25064kSuche in Google Scholar

37. Zehbe, K., Kollosche, M., Lardong, S., Kelling, A., Schilde, U., Taubert, A. Ionogels based on poly(methyl methacrylate) and metal-containing ionic liquids: correlation between structure and mechanical and electrical properties. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 391; https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms17030391.Suche in Google Scholar

38. Kociolek-Balawejder, E., Stanislawska, E., Ciechanowska, A. Iron(III) (hydr)oxide loaded anion exchange hybrid polymers obtained via tetrachloroferrate ionic form—synthesis optimization and characterization. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2017, 5, 3354–3361.10.1016/j.jece.2017.06.043Suche in Google Scholar

39. Reiss, G. J. The double salt tris(diisopropylammonium) tetrachloridoferrate(III) dichloride: synthesis, crystal structure, and vibrational spectra. J. Struct. Chem. 2012, 53, 403–407; https://doi.org/10.1134/s0022476612020308.Suche in Google Scholar

40. Reiss, G. J. Z. Crystal structure of pentakis(diisobutylaminium) dichloride tris(tetrachloridoferrate(III), C40H100Cl14Fe3N5. Z. Kristallogr. N. Cryst. Struct. 2013, 228, 407–409https://doi.org/10.1524/ncrs.2013.0187.Suche in Google Scholar

41. Kruszynski, R., Wyrzykowski, D., Styczen, E., Chmurzynski, L. Bis(8-methylquinolinium) tetrachloridoferrate(III) chloride. Acta Crystallogr. E 2007, 63, m2279–m2280; https://doi.org/10.1107/s1600536807037555.Suche in Google Scholar

42. Boudjarda, A., Bouchouit, K., Arroudj, S., Bouacida, S., Merazig, H. Crystal structure of bis(quinolin-1-ium) tetrachloridoferrate(III) chloride. Acta Crystallogr. E 2015, 71, m273–m274; https://doi.org/10.1107/s2056989015024548.Suche in Google Scholar

43. Shamir, J., Sobota, P. Raman spectrum of [MgCl(THF)5][FeCl4] . THF. J. Raman Spectrosc. 1991, 22, 535–536 https://doi.org/10.1002/jrs.1250220912.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2021 Guido J. Reiss and Maik Wyshusek, published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- New Crystal Structures

- Crystal structure of (E)-7-hydroxy-2-((6-methoxypyridin-3-yl)methylene)-3, 4-dihydronaphthalen-1(2H)-one, C17H15NO3

- Crystal structure of (E)-7-methoxy-2-((2-methoxypyridin-3-yl)methylene)-3,4-dihydronaphthalen-1 (2H)-one, C18H17NO3

- The crystal structure of N 6,N 6′-di(pyridin-2-yl)-[2,2′-bipyridine]-6,6′-diamine, C20H16N6

- The crystal structure of {N 1,N 2-bis[2,4-dimethyl-6-(4-(tert-butyl)phenyl)(phenyl)methyl]acenaphthylene-1,2-diimino-κ2 N, N′}-dibromido-nickel(II) – dichloromethane(1/2), C64H64Br2Cl4N2Ni

- Synthesis and crystal structure of nonacarbonyltris[(2-thia-1,3,5-triaza-7-phosphatricylco[3.3.1.1]decane-κ1 P)-2,2-dioxide]triruthenium(0) – acetonitrile (7/6), C25.71H32.57N9.86O15P3S3Ru3

- A new polymorph of 1-(4-nitrophenyl)-1H-benzimidazole (C13H9N3O2)

- The crystal structure of 2,2′-((1E,1′E)-(naphthalene-2,3 diylbis(azanylylidene)) bis(methanylylidene))bis(4-methylphenol), C26H22N2O2

- The crystal structure of bis(μ2-iodido)-bis(η6-benzene)-bis(iodido)-diosmium(II), C12H12I4Os2

- Redetermination of the crystal structure of bis{hydridotris(3,5-dimethylpyrazol-1-yl-κN 3)borato}copper(II), C30H44B2CuN12

- Crystal structure of (E)-3-((4-(tert-butyl)phenyl)thio)-4-hydroxypent-3-en-2-one, C15H20O2S

- Crystal structure of 2,2′-(p-tolylazanediyl)bis(1-phenylethan-1-one), C23H21NO2

- Redetermination of the crystal structure of the crystal sponge the poly[tetrakis(μ3-2,4,6-tris(pyridin-4-yl)-1,3,5-triazine)-dodecaiodidohexazinc(II) nitrobenzene solvate], C72H48I12N24Zn6⋅10(C6H5NO2)

- Crystal structure of (4′E)-6′-(diethylamino)-2-[(E)-[(6-methylpyridin-2-yl)methylidene]amino]-4′-{2-[(2E)-1,3,3-trimethyl-2,3-dihydro-1H-indol-2-ylidene]ethylidene}-1′,2,2′,3,3′,4′-hexahydrospiro[isoindole-1,9′-xanthene]-3-one, C44H45N5O2

- Crystal structure of (E)-7-fluoro-2-(3-fluorobenzylidene)-3,4-dihydronaphthalen-1(2H)-one, C17H12F2O1

- Crystal structure of tetrabutylammonium sulfanilate – 1-(diaminomethylene)thiourea (1/2)

- Crystal structure of [2,2′-{azanediyl)bis[(propane-3,1-diyl)(azanylylidene)methylylidene]} bis(3,5-dichlorophenolato)-κ2O,O′]-isothiocyanato-κN-iron(III), C21H19Cl4FeN4O2S

- Crystal structure of (4-chlorophenyl)(4-hydroxyphenyl)methanone, C13H9ClO2

- Crystal structure of 6,6′-((pentane-1,3-diylbis(azaneylylidene))bis(methaneylylidene))bis(2,4-dibromolphenolato-κ4 N,N′,O,O′)copper(II),) C19H16Br4CuN2O2

- Chlorido-(2,2′-(ethane-bis(5-methoxyphenolato))-κ4 N,N′,O,O′)manganese(III) monohydrate, C19H18Cl2CuN2O2

- Crystal structure of 2,6-di-tert-butyl-4-(4-methoxybenzylidene)cyclohexa-2,5-dien-1-one, C22H28O2

- Crystal structure of [6,6′-(((2,2-dimethylpropane-1,3-diyl)bis(azanylylidene))bis(methanylylidene))bis(2-chlorophenolato)-κ4N,N′,O,O′]copper(II)

- Crystal structure of 2-chloro-3-((thiophen-2-ylmethyl)amino)naphthalene-1,4-dione, C30H20O4N2Cl2S2

- Crystal structure of bis{hydridotris(3-trifluoromethyl-5-methylpyrazolyl-1-yl)borato-κN 3}manganese(II), C30H26B2F18MnN12

- Crystal structure of 1-(2-methylphenyl)-2-(2-methylbenzo[b]thienyl)-3,3,4,4,5,5-hexafluorocyclopent-ene, C21H14F6S

- Crystal structure of 2-(3-((carbamimidoylthio)methyl)benzyl)isothiouronium hexafluorophosphate monohydrate, C10H17F6N4OPS2

- Crystal structure of 4,5-diiodo-1,3-dimesityl-1H-1,2,3-triazol-3-ium chloride – chloroform (1/1), C21H23Cl4I2N3

- Crystal structure of azido-k1 N-{6,6′-((((methylazanediyl)bis(propane-3,1-diyl))bis(azanylylidene))bis(methanylylidene))bis(2,4-dibromophenolato)k5 N,N′,N″,O,O′}cobalt(III)-methanol (1/1)), C21H23Br4CoN6O3

- The crystal structure of 2-(4-((carbamimidoylthio)methyl)benzyl)isothiouronium hexafluorophosphate monohydrate, C10H17F6N4OPS2

- Crystal structure of 1,1′-(methane-1,1-diyl)bis(3-methyl-1H-imidazol-3-ium) bis(hexafluoridophosphate), C9H14F12N4P2

- Crystal structure of (4′E)-6′-(diethylamino)-2-[(E)-[(pyren-1-yl)methylidene]amino]-4′-{2-[(2E)-1,3,3-trimethyl-2,3-dihydro-1H-indol-2-ylidene]ethylidene}-1′,2,2′,3,3′,4′-hexahydrospiro[isoindole-1,9′-xanthene]-3-one, C54H48N4O2

- Crystal structure of poly[bis(μ2-2,6-bis(1-imidazoly)pyridine-κ2 N,N′)-bis(thiocyanato-κ1 N)copper(II)] dithiocyanate, C24H18CuN12S2

- Cones with a three-fold symmetry constructed from three hydrogen bonded theophyllinium cations that coat [FeCl4]− anions in the crystal structure of tris(theophyllinium) bis(tetrachloridoferrate(III)) chloride trihydrate, C21H33Cl9Fe2N12O9

- Crystal structure of 14-O-[(4-(4-hydroxypiperidine-1-yl)-6-methylpyrimidine-2-yl)thioacetyl]-mutilin monohydrate, C32H49N3O6S

- The crystal structure of (E)-3-chloro-2-(2-(4-methylbenzylidene)hydrazinyl)pyridine, C13H12ClN3

- The crystal structure of 4-phenyl-4-[2-(pyridine-4-carbonyl)hydrazinylidene]butanoic acid, C16H15N3O3

- The crystal structure of 6-amino-5-carboxypyridin-1-ium pentaiodide monohydrate C6H9I5N2O3

- Crystal structure of bis(μ3-oxido)-bis(μ2-2-formylbenzoato-k2O:O′)-bis(2-(dimethoxymethyl)-benzoato-κO)-oktakismethyl-tetratin(IV)

- Crystal structure of 2-((E)-(((E)-2-hydroxy-4-methylbenzylidene) hydrazineylidene)methyl)-4-methylphenol, C16H16N2O2

- Crystal structure of (E)-amino(2-((5-methylfuran-2-yl)methylene)hydrazinyl) methaniminium nitrate monohydrate, C14H26N10O10

- The crystal structure of N′-(2-chloro-6-hydroxybenzylidene)thiophene-2-carbohydrazide monohydrate, C12H11ClN2O3S

- Crystal structure of catena-poly[(μ2-1,1′-(biphenyl-4,4′-diyl)bis(1H-imidazol)-κ2N:N′)-bis(4-bromobenzoate-κ1O)zinc(II)], C64H44Br4N8O8Zn2

- The crystal structure of catena-poly[(1-(4-carboxybenzyl)pyridin-1-ium-4-carboxylato-κ1O)-(μ2-oxalato-κ4 O:O′:O″:O‴)dioxidouranium(VI)], C16H11NO10U

- Crystal structure of 3-allyl-4-(2-bromoethyl)-5-(4-methoxyphenyl)-2-phenylfuran, C22H21BrO2

- Halogen bonds in the crystal structure of 4,3′:5′,4″-terpyridine — 1,3-diiodotetrafluorobenzene (1/1), C21H11F4I2N3

- Crystal structure of 2-(1H-indol-3-yl)ethan-1-aminium 2-(4-acetylphenoxy)acetate, C20H22N2O4

- Chalcogen bonds in the crystal structure of 4,7-dibromo-2,1,3-benzoselenadiazole, C6H2Br2N2Se

- The crystal structure of 1,4-bis((1H-benzimidazol-2-yl)methyl)-piperazine-2,5-dione dihydrate, C20H22N6O4

- The crystal structure of C19H20O8

- The crystal structure of KNa3Te8O18·5H2O exhibiting a ∞2[Te4O9]2− layer

- Erratum

- Erratum to: Crystal structure of (Z)-3-(6-bromo-1H-indol-3-yl)-1,3-diphenylprop-2-en-1-one, C23H16BrNO

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- New Crystal Structures

- Crystal structure of (E)-7-hydroxy-2-((6-methoxypyridin-3-yl)methylene)-3, 4-dihydronaphthalen-1(2H)-one, C17H15NO3

- Crystal structure of (E)-7-methoxy-2-((2-methoxypyridin-3-yl)methylene)-3,4-dihydronaphthalen-1 (2H)-one, C18H17NO3

- The crystal structure of N 6,N 6′-di(pyridin-2-yl)-[2,2′-bipyridine]-6,6′-diamine, C20H16N6

- The crystal structure of {N 1,N 2-bis[2,4-dimethyl-6-(4-(tert-butyl)phenyl)(phenyl)methyl]acenaphthylene-1,2-diimino-κ2 N, N′}-dibromido-nickel(II) – dichloromethane(1/2), C64H64Br2Cl4N2Ni

- Synthesis and crystal structure of nonacarbonyltris[(2-thia-1,3,5-triaza-7-phosphatricylco[3.3.1.1]decane-κ1 P)-2,2-dioxide]triruthenium(0) – acetonitrile (7/6), C25.71H32.57N9.86O15P3S3Ru3

- A new polymorph of 1-(4-nitrophenyl)-1H-benzimidazole (C13H9N3O2)

- The crystal structure of 2,2′-((1E,1′E)-(naphthalene-2,3 diylbis(azanylylidene)) bis(methanylylidene))bis(4-methylphenol), C26H22N2O2

- The crystal structure of bis(μ2-iodido)-bis(η6-benzene)-bis(iodido)-diosmium(II), C12H12I4Os2

- Redetermination of the crystal structure of bis{hydridotris(3,5-dimethylpyrazol-1-yl-κN 3)borato}copper(II), C30H44B2CuN12

- Crystal structure of (E)-3-((4-(tert-butyl)phenyl)thio)-4-hydroxypent-3-en-2-one, C15H20O2S

- Crystal structure of 2,2′-(p-tolylazanediyl)bis(1-phenylethan-1-one), C23H21NO2

- Redetermination of the crystal structure of the crystal sponge the poly[tetrakis(μ3-2,4,6-tris(pyridin-4-yl)-1,3,5-triazine)-dodecaiodidohexazinc(II) nitrobenzene solvate], C72H48I12N24Zn6⋅10(C6H5NO2)

- Crystal structure of (4′E)-6′-(diethylamino)-2-[(E)-[(6-methylpyridin-2-yl)methylidene]amino]-4′-{2-[(2E)-1,3,3-trimethyl-2,3-dihydro-1H-indol-2-ylidene]ethylidene}-1′,2,2′,3,3′,4′-hexahydrospiro[isoindole-1,9′-xanthene]-3-one, C44H45N5O2

- Crystal structure of (E)-7-fluoro-2-(3-fluorobenzylidene)-3,4-dihydronaphthalen-1(2H)-one, C17H12F2O1

- Crystal structure of tetrabutylammonium sulfanilate – 1-(diaminomethylene)thiourea (1/2)

- Crystal structure of [2,2′-{azanediyl)bis[(propane-3,1-diyl)(azanylylidene)methylylidene]} bis(3,5-dichlorophenolato)-κ2O,O′]-isothiocyanato-κN-iron(III), C21H19Cl4FeN4O2S

- Crystal structure of (4-chlorophenyl)(4-hydroxyphenyl)methanone, C13H9ClO2

- Crystal structure of 6,6′-((pentane-1,3-diylbis(azaneylylidene))bis(methaneylylidene))bis(2,4-dibromolphenolato-κ4 N,N′,O,O′)copper(II),) C19H16Br4CuN2O2

- Chlorido-(2,2′-(ethane-bis(5-methoxyphenolato))-κ4 N,N′,O,O′)manganese(III) monohydrate, C19H18Cl2CuN2O2

- Crystal structure of 2,6-di-tert-butyl-4-(4-methoxybenzylidene)cyclohexa-2,5-dien-1-one, C22H28O2

- Crystal structure of [6,6′-(((2,2-dimethylpropane-1,3-diyl)bis(azanylylidene))bis(methanylylidene))bis(2-chlorophenolato)-κ4N,N′,O,O′]copper(II)

- Crystal structure of 2-chloro-3-((thiophen-2-ylmethyl)amino)naphthalene-1,4-dione, C30H20O4N2Cl2S2

- Crystal structure of bis{hydridotris(3-trifluoromethyl-5-methylpyrazolyl-1-yl)borato-κN 3}manganese(II), C30H26B2F18MnN12

- Crystal structure of 1-(2-methylphenyl)-2-(2-methylbenzo[b]thienyl)-3,3,4,4,5,5-hexafluorocyclopent-ene, C21H14F6S

- Crystal structure of 2-(3-((carbamimidoylthio)methyl)benzyl)isothiouronium hexafluorophosphate monohydrate, C10H17F6N4OPS2

- Crystal structure of 4,5-diiodo-1,3-dimesityl-1H-1,2,3-triazol-3-ium chloride – chloroform (1/1), C21H23Cl4I2N3

- Crystal structure of azido-k1 N-{6,6′-((((methylazanediyl)bis(propane-3,1-diyl))bis(azanylylidene))bis(methanylylidene))bis(2,4-dibromophenolato)k5 N,N′,N″,O,O′}cobalt(III)-methanol (1/1)), C21H23Br4CoN6O3

- The crystal structure of 2-(4-((carbamimidoylthio)methyl)benzyl)isothiouronium hexafluorophosphate monohydrate, C10H17F6N4OPS2

- Crystal structure of 1,1′-(methane-1,1-diyl)bis(3-methyl-1H-imidazol-3-ium) bis(hexafluoridophosphate), C9H14F12N4P2

- Crystal structure of (4′E)-6′-(diethylamino)-2-[(E)-[(pyren-1-yl)methylidene]amino]-4′-{2-[(2E)-1,3,3-trimethyl-2,3-dihydro-1H-indol-2-ylidene]ethylidene}-1′,2,2′,3,3′,4′-hexahydrospiro[isoindole-1,9′-xanthene]-3-one, C54H48N4O2

- Crystal structure of poly[bis(μ2-2,6-bis(1-imidazoly)pyridine-κ2 N,N′)-bis(thiocyanato-κ1 N)copper(II)] dithiocyanate, C24H18CuN12S2

- Cones with a three-fold symmetry constructed from three hydrogen bonded theophyllinium cations that coat [FeCl4]− anions in the crystal structure of tris(theophyllinium) bis(tetrachloridoferrate(III)) chloride trihydrate, C21H33Cl9Fe2N12O9

- Crystal structure of 14-O-[(4-(4-hydroxypiperidine-1-yl)-6-methylpyrimidine-2-yl)thioacetyl]-mutilin monohydrate, C32H49N3O6S

- The crystal structure of (E)-3-chloro-2-(2-(4-methylbenzylidene)hydrazinyl)pyridine, C13H12ClN3

- The crystal structure of 4-phenyl-4-[2-(pyridine-4-carbonyl)hydrazinylidene]butanoic acid, C16H15N3O3

- The crystal structure of 6-amino-5-carboxypyridin-1-ium pentaiodide monohydrate C6H9I5N2O3

- Crystal structure of bis(μ3-oxido)-bis(μ2-2-formylbenzoato-k2O:O′)-bis(2-(dimethoxymethyl)-benzoato-κO)-oktakismethyl-tetratin(IV)

- Crystal structure of 2-((E)-(((E)-2-hydroxy-4-methylbenzylidene) hydrazineylidene)methyl)-4-methylphenol, C16H16N2O2

- Crystal structure of (E)-amino(2-((5-methylfuran-2-yl)methylene)hydrazinyl) methaniminium nitrate monohydrate, C14H26N10O10

- The crystal structure of N′-(2-chloro-6-hydroxybenzylidene)thiophene-2-carbohydrazide monohydrate, C12H11ClN2O3S

- Crystal structure of catena-poly[(μ2-1,1′-(biphenyl-4,4′-diyl)bis(1H-imidazol)-κ2N:N′)-bis(4-bromobenzoate-κ1O)zinc(II)], C64H44Br4N8O8Zn2

- The crystal structure of catena-poly[(1-(4-carboxybenzyl)pyridin-1-ium-4-carboxylato-κ1O)-(μ2-oxalato-κ4 O:O′:O″:O‴)dioxidouranium(VI)], C16H11NO10U

- Crystal structure of 3-allyl-4-(2-bromoethyl)-5-(4-methoxyphenyl)-2-phenylfuran, C22H21BrO2

- Halogen bonds in the crystal structure of 4,3′:5′,4″-terpyridine — 1,3-diiodotetrafluorobenzene (1/1), C21H11F4I2N3

- Crystal structure of 2-(1H-indol-3-yl)ethan-1-aminium 2-(4-acetylphenoxy)acetate, C20H22N2O4

- Chalcogen bonds in the crystal structure of 4,7-dibromo-2,1,3-benzoselenadiazole, C6H2Br2N2Se

- The crystal structure of 1,4-bis((1H-benzimidazol-2-yl)methyl)-piperazine-2,5-dione dihydrate, C20H22N6O4

- The crystal structure of C19H20O8

- The crystal structure of KNa3Te8O18·5H2O exhibiting a ∞2[Te4O9]2− layer

- Erratum

- Erratum to: Crystal structure of (Z)-3-(6-bromo-1H-indol-3-yl)-1,3-diphenylprop-2-en-1-one, C23H16BrNO