Abstract

Composite materials are used in many industries. Their mechanical and physical properties as well as their low weight make them suitable for use in many constructions. Their wide application generates a problem with their disposal. Therefore, it is necessary to design new materials based on waste from polyester–glass laminates in order to introduce a closed circuit in the composite production process. The article presents research aimed at determining solid material composites with polyester–glass recyclate, in order to use these materials for modeling the structure. The aim of this study was to determine the effect of the addition of recyclate to the polyester–glass composite on the deformation and the value of the Poisson number of the material. During the study, samples from composites with the addition of polyester–glass recyclate were used. Samples made in accordance with the standard for plastics PN-EN ISO 527-4_2000P were subjected to static tensile test on a universal testing machine, with variable load parameters. During the test, the longitudinal and transverse elongations of the samples were measured using a strain gauge measuring system. On the basis of the measurements, the values of Poisson numbers were determined, which allowed for a preliminary assessment of the impact of the recyclate content in the composite on its deformability.

1 Introduction

Over the last few years, there has been a significant increase in the use of composite materials, in particular those with fiberglass reinforcement. The interest in this material is related to relatively high mechanical and physical properties, low weight and the ease of forming various types of shapes. They are used as a construction material in industry, from the main construction material of vessels in the yachting industry, to railways, automotive and aviation [1,2,3,4]. The wide range of use of these materials translates into the amount of waste, which makes it necessary to develop methods of their utilization [5,6]. There are many methods for recovering glass fibers from waste and it is possible to use them as full-value components [7], replacing part of the reinforcing phase in the new materials [8,9,10]. The recycling of composite materials is a topic of global importance and continues to be a scientific goal of research teams around the world. The material that was previously considered unusable turns out to be usable, thus contributing to waste management [2,11,12]. The potential for saving resources through the use of more sustainable and advanced composites production methods is visible [13,14].

Earlier studies have shown that the use of polyester–glass recyclate as a filler in the matrix of new composite materials is a future-oriented and innovative direction in terms of polyester–glass waste recycling [15]. The use of polyester–glass recyclate reduces the mechanical properties of the composite material; however, the material can still be used for less responsible constructions, such as superstructures [3]. It is also possible to produce composite materials with a filler in the form of polyester–glass recyclate, not only by hand lamination [16] but also by the vacuum bag method [15]. These are materials which can be shaped in any direction, which additionally makes them more attractive, but hinders the design process [17,18]. Therefore, it seems necessary in terms of the use of these materials to determine the solid materials necessary for modeling various types of structures [19–32]. This could contribute to the industrial application of these materials.

In this article, composite materials with polyester–glass recyclate were used to determine the Poisson’s ratio. The determination of this parameter is significant not only in terms of determining the deformability of this material, but also in terms of modeling. A static tensile test was carried out in order to determine the Young’s modulus. In addition, tests were carried out with the use of strain gauges, measuring the longitudinal and transverse elongations to determine the Poisson’s ratio. On the basis of the performed measurements, the values of Poisson numbers were determined, which allowed for a preliminary assessment of the impact of the recyclate content in the composite on its deformability.

2 Materials and methods

The tests were carried out on samples made of polyester–glass composites. The composites contained various contents of recyclate and were made by hand lamination. The method of preparing composites with different recyclate content is described in detail in refs. [6,7,8]. Three composite samples were prepared for the study with the content of polyester–glass recyclate in the amount of 10 and 20%, and for comparison purpose, a composite sample without recyclate was also used. The recyclate granulation was <1.2 mm.

The recycle material was part of the hull of a decommissioned and scrapped vessel. Composite scrap obtained from the fuselage elements was initially crushed with a hammer and processed into polyester–glass granules using a crusher (Figure 1). After the process, the granulate was screened through sieves with a mesh diameter ≤1.2 mm.

In the next stage of composite preparation, materials were formed with the use of recyclate. The production of polyester–glass laminates with the addition of recyclate was carried out using the manual laminating method [9,10] with the use of metal molds, glass mat, recyclate and polyester resin and a roller for even distribution and saturation of excess resin (Figure 2). Polimal 1094-AWTP resin was used. As a result of manual lamination, a research material was obtained with a specific number of glass mat layers and the assumed percentage composition of resin and recyclate [11,12] (Table 1).

Manual production of polyester–glass composite.

| Composite marking | Recycle content (%) | Glass mat content (%) | Resin content (%) | Number of layers of glass mat | Glass mat (g) | Resin (g) | Recycle (g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| K0 | 0 | 40 | 60 | 12 | 192.1 | 288 | — |

| K10 | 10 | 30 | 60 | 10 | 169.7 | 339 | 56.5 |

| K20 | 20 | 25 | 57 | 10 | 165.0 | 366 | 117 |

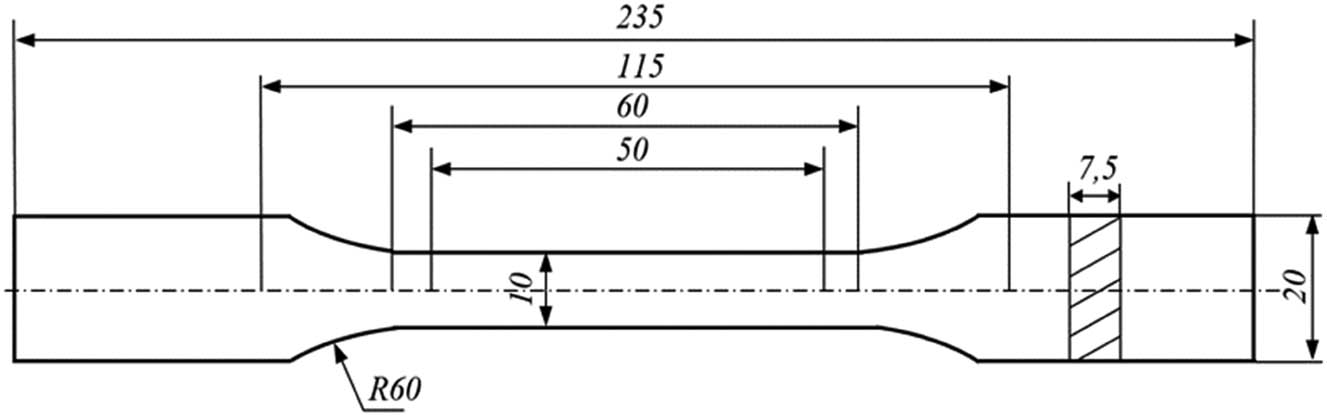

Test specimens were made from composite materials prepared in this way. The samples were made by the water cutting method, and their shape and dimensions were consistent with the standard of static stretching of composite materials PN-EN ISO 527-4_2000P (Figure 3) [14].

Shape and dimensions of test samples.

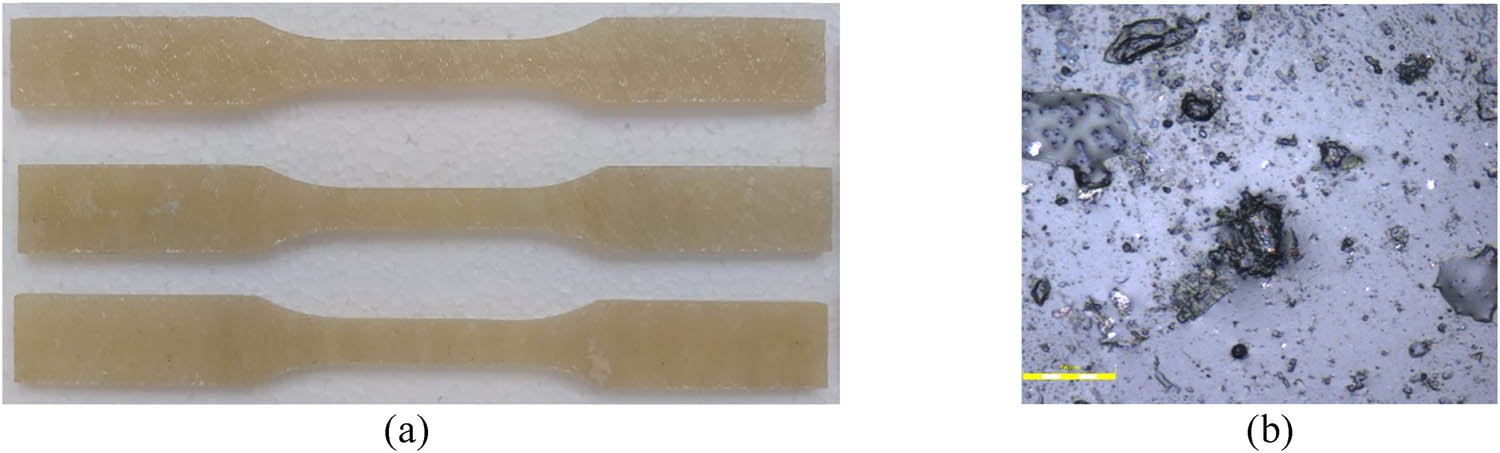

Figure 4a shows the view of samples made of polyester–glass composite without recyclate – K0. Figure 4b shows a photo of the surface structure of the samples taken with the LEXT OLS41000 confocal laser microscope. In Figure 4b, air pores and resin particles are noticeable, especially at the reinforcement.

View of samples without the addition of recyclate (a) and structure of the K0 composite at magnification 50× (b).

An important aspect is the adhesion between the resin and the fibers. Moreover, the boundary between the fibers is visible.

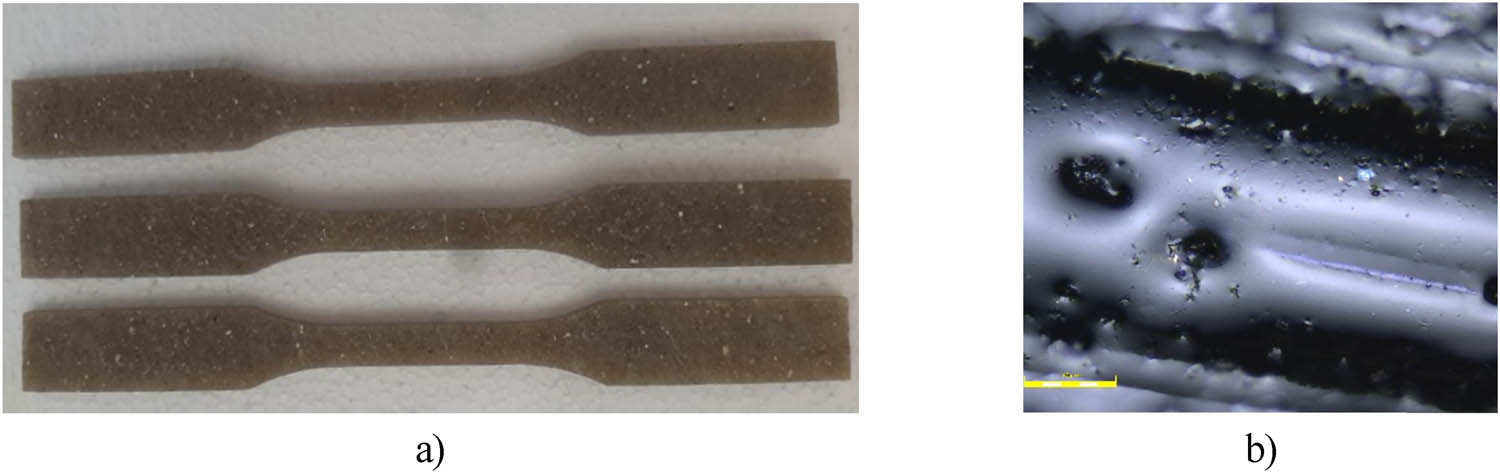

The surface structure of samples with 10% recyclate content (Figure 5a and b) is characterized by a large number of pores; moreover, recyclate granules in the structure are visible. There is a noticeable reduction in adhesion between the resin with recyclate and the reinforcement. The influence of the recyclate on the structure is observed between successive layers of reinforcement.

View of samples with 10% recyclate content (a) and structure of the K10 composite at magnification 50× (b).

Figure 6a shows the view of samples made of polyester–glass composite with a 20% content of recyclate – K20. Due to the higher content of recyclate, dark color of the samples is observed. In Figure 6b, large recyclate inclusions and air pores are noticeable. Moreover, the boundary between the fibers is visible.

View of samples with 20% recyclate content (a) and K20 composite structure at magnification 50× (b).

In the generalized Hooke’s law, expressing the relationship between the state of deformation and stress, there is a compliance matrix containing two material constants for isotropic bodies (E, ν). However, in the case under consideration, for monotropic (transversally isotropic) bodies, there are five material constants [1,2,3,4,5].

According to refs. [1,2,4], for material with orthogonal anisotropy, the generalized Hooke’s law written in the summation convention is expressed as:

where

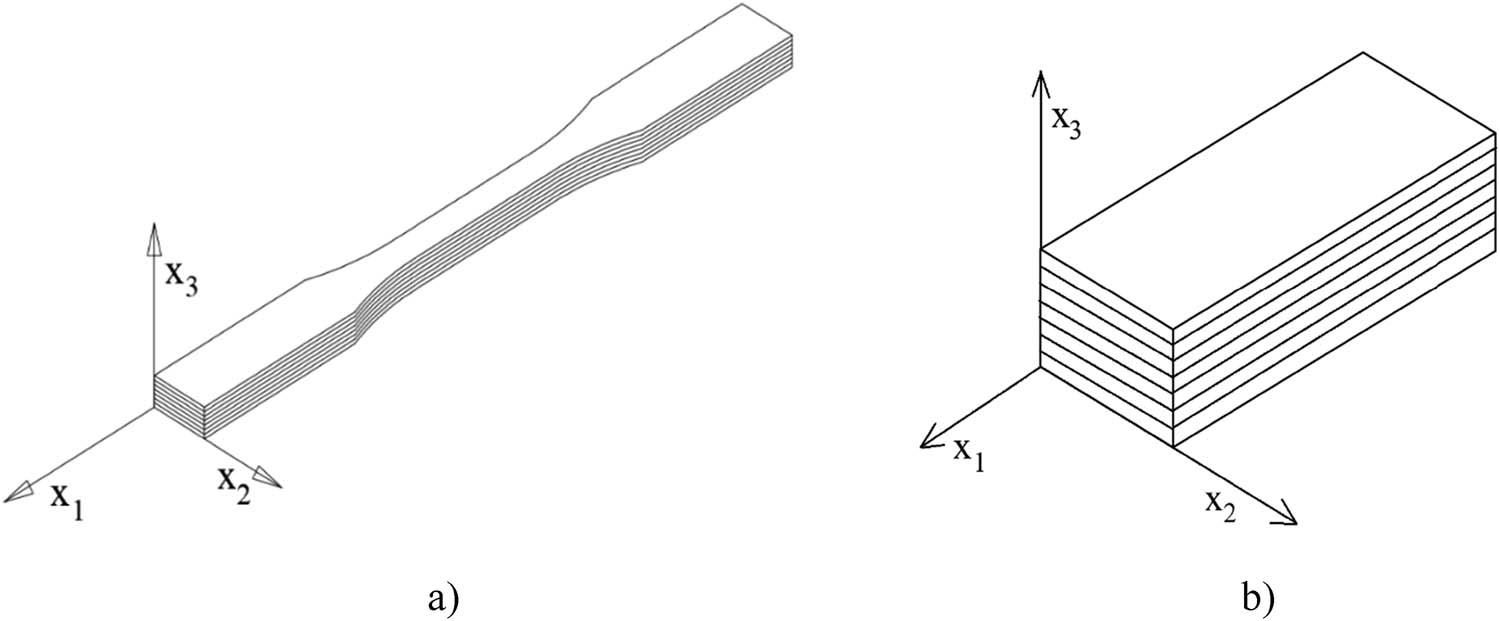

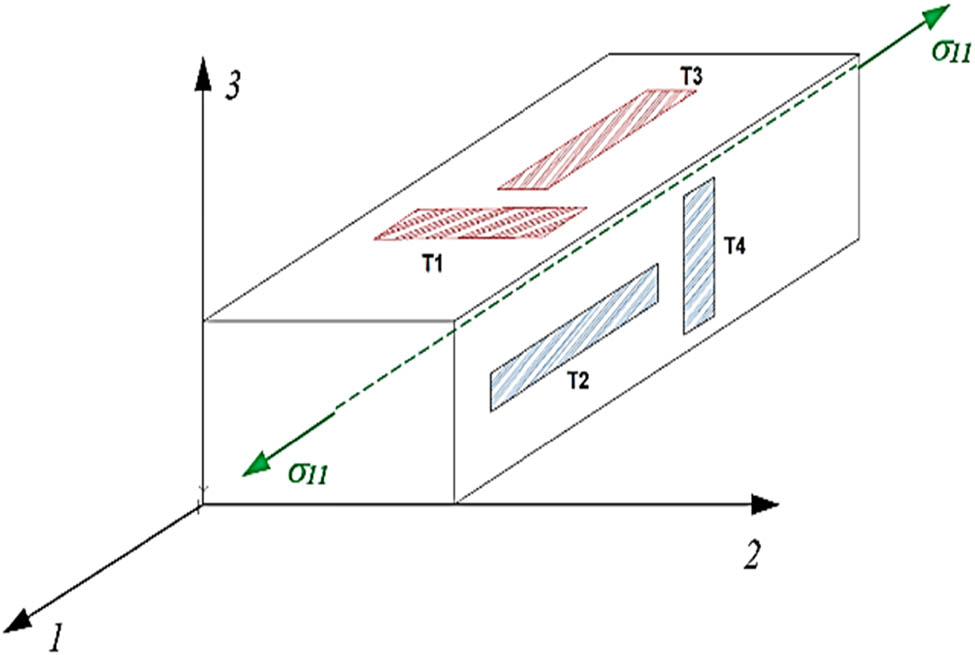

In the literature of the description of composite properties, the index notation 1, 2, 3 is used, corresponding to the coordinate axis system (Figure 7).

Orientation in the coordinate system (a) and the measuring part of the sample (b).

In the general case, for an orthotropic material, the components of the compliance tensor using engineering constants in the form of matrices can be written [17]:

There are 12 terms other than zero in the susceptibility matrix (2). Due to their symmetry with respect to the main diagonal, relations take place:

and on this basis the number of independent terms of the susceptibility matrix is reduced to 9.

On the other hand, for a monotropic material, on the basis of the tensor transformation law, it is proved during rotation that additional equality takes place. If the axis of symmetry is axis 3 (Figure 7), then:

the fifth constant results from mutual relations.

The tested composite materials are monotropic materials. The value of the Poisson number for each of the tested samples was defined as the ratio of the transverse to longitudinal deformation [1,2,4] in accordance with the strain gauge markings in Figure 10 [15,16].

where

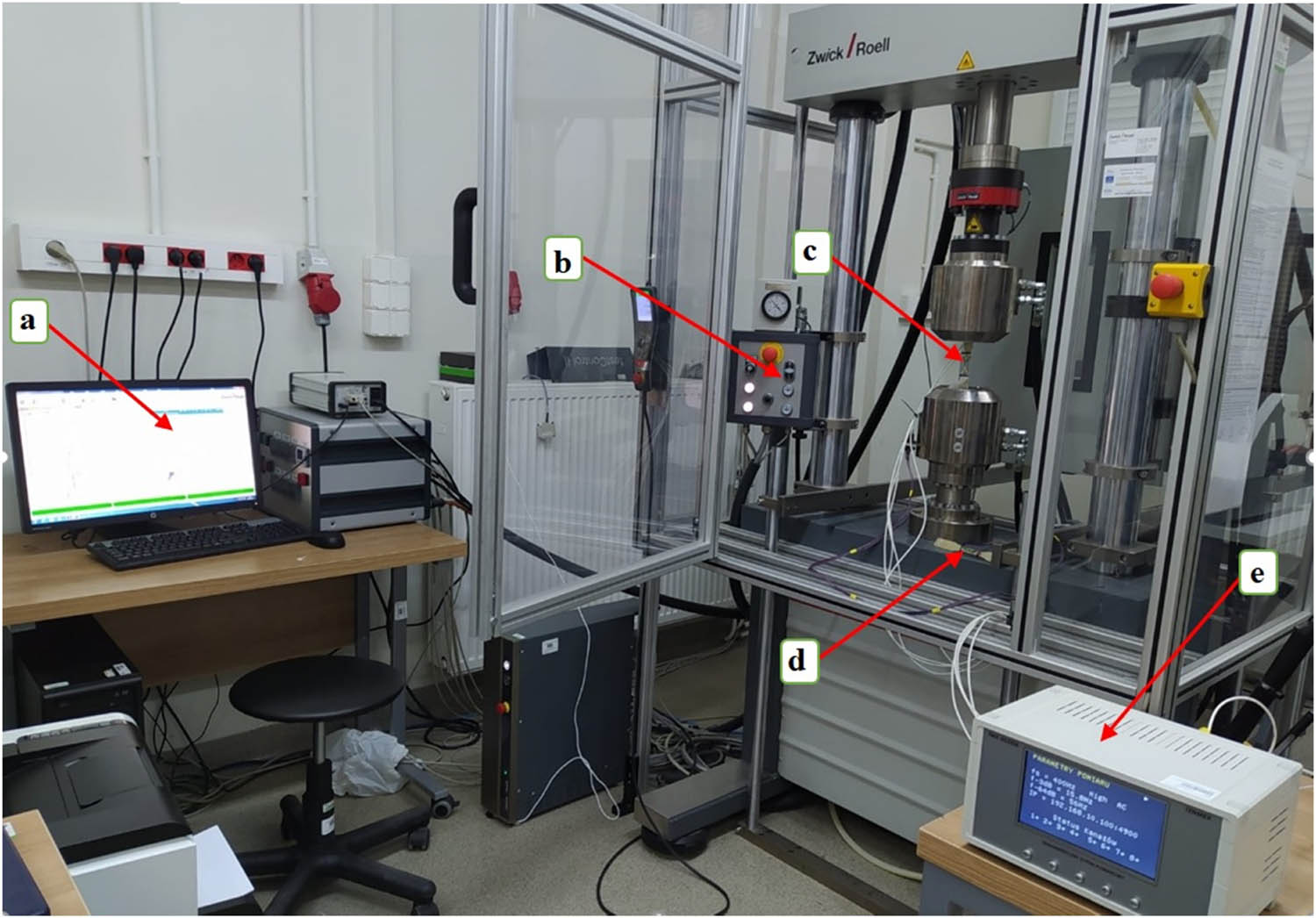

View of the Zwick Roell testing machine during the test. Computer stand (a), control panel of the machine (b), fixed composite sample (c), temperature compensation sample (d) and strain gauge measuring system (e).

Tensometric tests were carried out on samples subjected to tension using a universal Zwick Roell testing machine with a hydraulic drive, type MPMD P10B with TestXpert II software, version 3.61 (Figure 8). The test results for the samples were recorded using ZwickRoell-TestXpert II version 3.61.

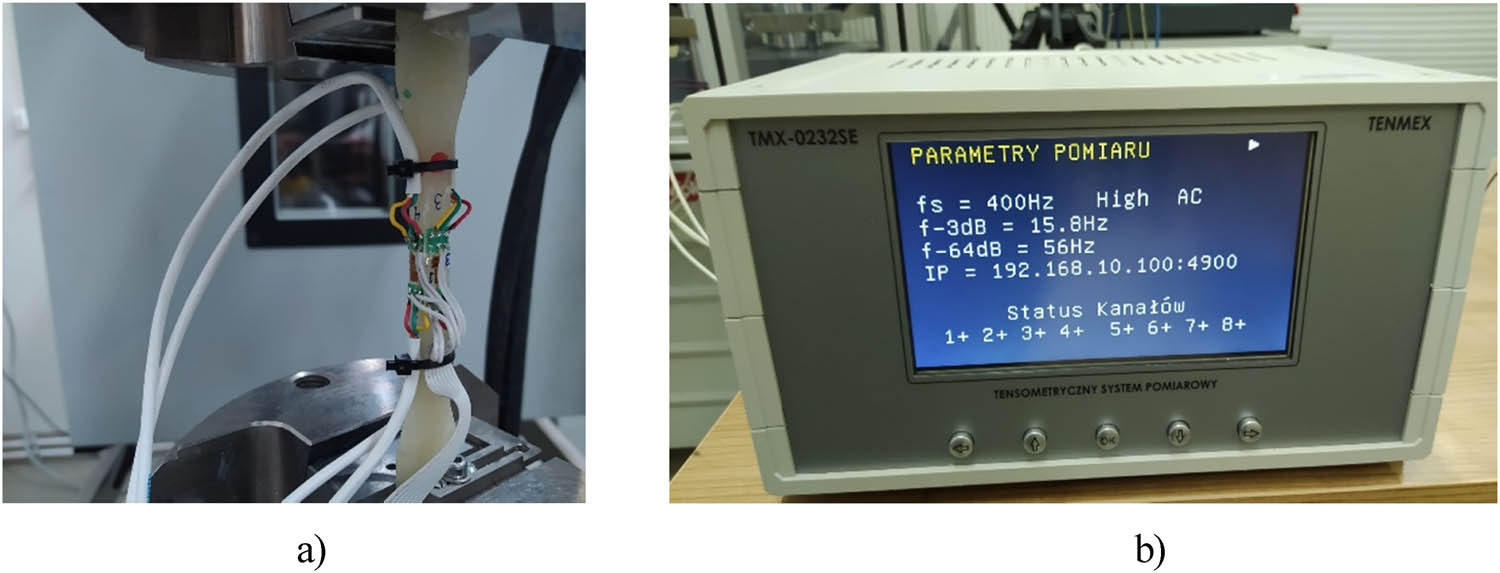

Sample with glued resistance strain gauges (a) and TMX 0216SE strain gauge measuring system (b).

To measure the deformation of the samples, a strain gauge TMX 0216SE measuring system (TENMEX, Poland) was used (Figure 9b), designed to work with strain gauges, in particular with strain gauges glued on the front and side surfaces of the sample (Figure 9a). In order to precisely place the strain gauge in a specific place on the sample, the cyanoacrylate adhesive TB-1731 and the self-adhesive TT-18 tape recommended by the manufacturer of the foil strain gauges were used [13].

Arrangement of strain gauges on the sample measuring surfaces.

Tensometric tests were carried out on samples subjected to stretching with a force of 100, 200, 300 and 400 N, with automatic registration of deformations using strain gauges. The use of the TMX 0216SE multi-channel strain gauge bridge made it possible to measure the longitudinal and transverse deformations of the samples of the tested materials. The deformation of the samples for each load value (100, 200, 300 and 400 N) was recorded after a fixed time interval for the given load. A diagram of the place of sticking strain gauges on the working part of samples oriented in the Cartesian coordinate system is shown in Figure 10.

3 Results and discussion

Based on the studies [8,9], the values of Young’s modulus were obtained, which are listed in Table 2.

Values of Young’s modulus of samples from composite with the addition of recyclate with a granule size ≤1.2 mm produced by the manual laminating method

| Composite | E 1 = E 2 (MPa) | E 3 (MPa) |

|---|---|---|

| K0 – 0% | 7,004 | 3,650 |

| K10 – 10% | 5,682 | 2,850 |

| K20 – 20% | 5,318 | 2,570 |

The results of strain gauge tests of the tested polymer composites without recyclate and with recyclate in accordance with the designations of strain gauges in Figure 10 are presented in Tables 3–5.

Results of strain gauge measurements of samples K0 without recyclate

| F (N) |

|

|

|

Time (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100 | 56.3 | −18.5 | −12.9 | 30 |

| 200 | 124.6 | −42.6 | −27.7 | 30 |

| 300 | 194.5 | −64.7 | −45.7 | 30 |

| 400 | 259.2 | −85.8 | −63.8 | 30 |

Results of strain gauge measurement of composite samples K10 with 10% recyclate content

| F (N) |

|

|

|

Time (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100 | 139.1 | −47.7 | −33.4 | 30 |

| 200 | 195.2 | −68.3 | −46.8 | 30 |

| 300 | 297.5 | −108.1 | 77.4 | 30 |

| 400 | 414.0 | −141.9 | −103.5 | 30 |

Results of strain gauge measurement of samples K20 with 20% recyclate content

| F (N) |

|

|

|

Time (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100 | 229.7 | −80.7 | −64.3 | 30 |

| 200 | 480.5 | −178.0 | −120.1 | 30 |

| 300 | 822.4 | −297.1 | −213.8 | 30 |

| 400 | 1063.0 | −379.7 | −308.3 | 30 |

Using the compounds (3), the Poisson’s ratio values of the tested composites with and without recyclate were determined in accordance with the markings in Figure 10.

because

because

The average values of Poisson’s ratios for the composite without K0 recyclate and with K10 and K20 recyclates are shown in Table 6.

Values of Poisson’s ratios for composites K0, K10 and K20

| Composite |

|

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| K0 | 0.33 | 0.23 | 0.12 |

| K10 | 0.35 | 0.25 | 0.12 |

| K20 | 0.36 | 0.27 | 0.13 |

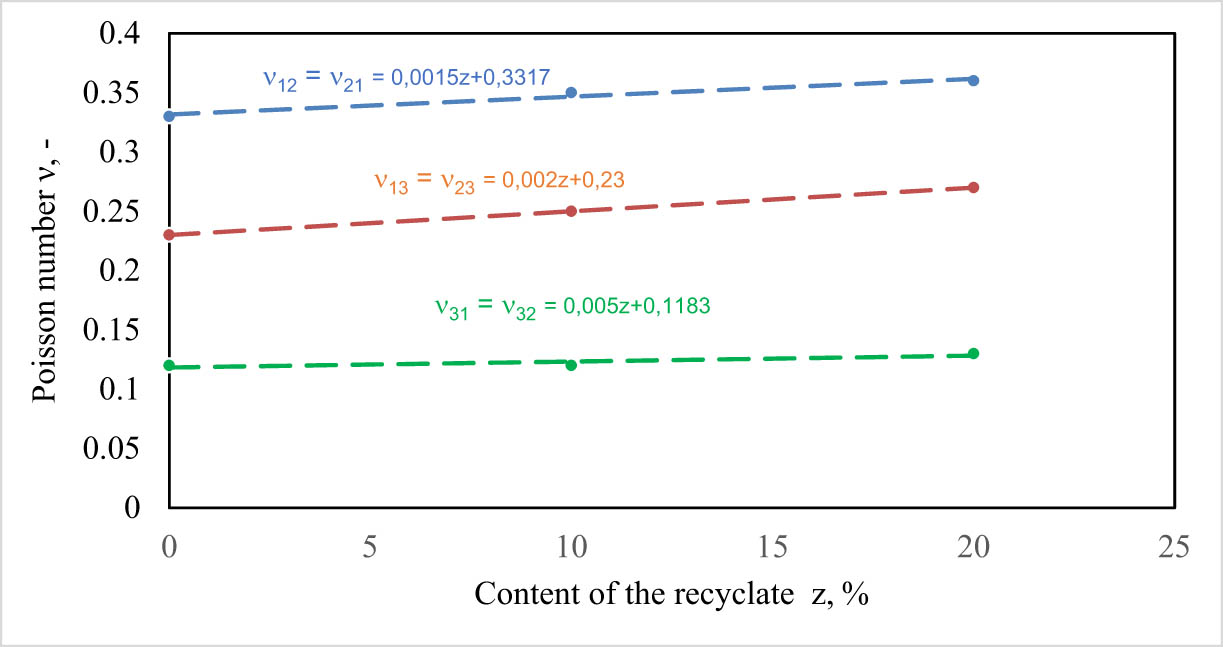

Figure 11 shows the changes in the value of the Poisson’s ratio depending on the content of the recyclate in the polyester–glass composite.

Diagram of dependency between Poisson number and content of the recyclate in samples.

The changes in the values of Poisson’s ratios depending on the content of recyclate in the polyester–glass composite presented in Figure 11 prove the changes in the mechanical properties of the tested composites. The increase in the content of recyclate caused a decrease in the value of Young’s modulus and an increase in the value of Poisson’s coefficients. Composites with a higher content of recyclate show an increase in the deformability of the material with a decrease in mechanical properties.

4 Conclusion

Determining the physical properties of polyester–glass composites with the addition of recyclate requires conducting experimental and analytical research. Tensometric tests allow to determine material constants, i.e., Poisson coefficients, with high accuracy.

The tests carried out with the use of strain gauges showed that changes in the percentage of recyclate content in the composite have a significant impact on the change in the strength properties, i.e., longitudinal and transverse deformations, and, as a result, on the change in the Poisson’s ratio. The measurement results became the basis for determining the trend of changes in the Poisson’s ratio depending on the changes in the recyclate (10 and 20%) in the composite.

The increase in the content of recyclate from 0 to 20% resulted in an increase in the deformability of the material and a reduction in its mechanical properties.

Determining the detailed changes in the composite deformability in relation to changes in the percentage of recyclate content requires the preparation and testing of a larger number of samples with a smaller jump in the percentage changes of the recyclate content.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

References

[1] Kyzioł L, Jastrzębska M. Determination of selected mechanical properties of composite waste materials. Logistyka. 2015;3:2758–63.Search in Google Scholar

[2] Królikowski W. Polymer structural composites. Warsaw: Scientific Publishing House PWN; 2012.Search in Google Scholar

[3] Panasiuk K. Analiza właściwości mechanicznych kompozytów warstwowych z recyklatem poliestrowo-szklanym. Gdynia: Publishing House of Gdynia Maritime University; 2019.Search in Google Scholar

[4] Kyzioł L, Panasiuk K, Hajdukiewicz G, Dudzik K. Acoustic emission and K–S metric entropy as methods for determining mechanical properties of composite materials. Sensors. 2021;21:145. 10.3390/s21010145.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[5] Rutecka M, Śleziona J, Myalski J. Estimation of possibility of using polyester–glass fiber recyclate in laminates production. Composites. 2004;9:56–60.Search in Google Scholar

[6] Żakowska H. Packaging waste recycling systems – selected legal, organizational and economic problems in Poland. Polimery. 2012;57:613–9.10.14314/polimery.2012.613Search in Google Scholar

[7] Rodrigues VD, Kennedy VR, Milena CC. Strategy and management for the recycling of carbon fiber-reinforced polymers (CFRPs) in the aircraft industry: a critical review. Int J Sustain Dev World Ecol. 2017;214–23.10.1080/13504509.2016.1204371Search in Google Scholar

[8] Kowalska E, Wielgosz Z, Bartczak T. Utilization of waste polyester–glass laminates. Polimery. 2002;47(2):110–6.10.14314/polimery.2002.110Search in Google Scholar

[9] Pickering S. Recycling technologies for thermoset composite materials—current status. Compos Part A: Appl Sci Manuf. 2006;37:1206–15.10.1016/j.compositesa.2005.05.030Search in Google Scholar

[10] Jeziórska R, Wierz-Motysia B, Szadkowska A. Modifiers for recycling of polymeric materials: production, properties and application. Polimery. 2010;55:748–56.10.14314/polimery.2010.748Search in Google Scholar

[11] Asmatulu E, Twomey J, Overcash M. Recycling of fiber-reinforced composites and direct structural composite recycling concept. J Composite Mater. 2014;48:593–608.10.1177/0021998313476325Search in Google Scholar

[12] Wong KH, Pickering SJ, Rudd CD. Recycled carbon fibre reinforced polymer composite for electromagnetic interference shielding. Composite Part A: Appl Sci Manuf. 2010;41:693–702.10.1016/j.compositesa.2010.01.012Search in Google Scholar

[13] Oliveux G, Dandy LO, Leeke GA. Current status of recycling of fibre reinforced polymers: review of technologies, reuse and resulting properties. Prog Mater Sci. 2015;72:61–99.10.1016/j.pmatsci.2015.01.004Search in Google Scholar

[14] Zahid B, Chen X. Manufacturing of single-piece textile reinforced riot helmet shell from vacuum bagging. J Composite Mater. 2013;47:2343–51.10.1177/0021998312457703Search in Google Scholar

[15] Kyzioł L, Panasiuk K, Barcikowski M, Hajdukiewicz G. The influence of manufacturing technology on the properties of layered composites with polyester–glass recyclate additive. Prog Rubber, Plast Recycling Technol. 2020;36(1):18–30. 10.1177/1477760619895003.Search in Google Scholar

[16] Kyzioł L, Panasiuk K, Hajdukiewicz G. The influence of granulation and content of polyester–glass waste on properties of composites. J Kones. 2018;4(25):223–9. 10.5604/01.3001.0012.4795.Search in Google Scholar

[17] Mrówka M, Woźniak A, Nowak J, Wróbel G, Sławski S. Determination of mechanical and tribological properties of silicone-based composites filled with manganese waste. Materials. 2021;14:4459. 10.3390/ma14164459.Search in Google Scholar

[18] Mrówka M, Woźniak A, Prężyna S, Sławski S. The influence of zinc waste filler on the tribological and mechanical properties of silicone-based composites. Polymers. 2021;13:585. 10.3390/polym13040585.Search in Google Scholar

[19] Kyzioł L. Analiza właściwości drewna konstrukcyjnego nasyconego powierzchniowo polimerem MM. Gdynia: Publishing house of the Naval Academy; 2004.Search in Google Scholar

[20] Kyzioł L. Drewno modyfikowane na konstrukcje morskie. Gdynia: Publishing house of the Naval Academy; 2010.Search in Google Scholar

[21] Kyzioł L. Determining strength of the modified wood. Pol Marit Res. 2008;2(56):40–5. 10.2478/v10012-007-0063-4 Search in Google Scholar

[22] Jayne BA. Theory and design of wood and fiber composite materials. New York: Syracuse University Press; 1972.Search in Google Scholar

[23] Rocens KA. Technologičeskije regulirovanie svojstv dreviesiny. Riga: Zinatyje Press; 1979.Search in Google Scholar

[24] Panasiuk K, Kyzioł L, Abramczyk N, Hajdukiewicz G. The impact of polyester-glass recyclate on the hardness and structure of composites. Sci J Marit Univ Szczec. 2019;59(131):22–6. 10.17402/348.Search in Google Scholar

[25] Jacob A. Composites can be recycled. Reinf Plast. 2011;55(3):45–6.10.1016/S0034-3617(11)70079-0Search in Google Scholar

[26] Gucma M, Bryll K, Gawdzińska K, Przetakiewicz W, Piesowicz E. Technology of single polymer polyester composites and proposals for their recycling. Sci J Marit Univ Szczec. 2015;44(116):14–8.Search in Google Scholar

[27] Błędzki AK, Gorący K, Urbaniak M. Possibilities of recycling and utlisation of the polymeric materials and composite products. Polimery. 2012;57:620–6.10.14314/polimery.2012.620Search in Google Scholar

[28] Barcikowski M, Królikowski W. Effect of resin modification on the impact strength of glass-polyester. Polimery. 2013;58(3):450–60.10.14314/polimery.2013.450Search in Google Scholar

[29] Baltazar K Technologie wytwarzania kompozytów polimerowych cz.1. http://www.baltazarkompozyty.pl/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=224:technologie-wytwarzania-kompozytow-polimerowych-cz-1&catid=15&Itemid=46 (2018, accessed 11 February 2020).Search in Google Scholar

[30] Reczek M, Skalski M, Baier A. Pomiary odkształceń materiałów kompozytowych z zastosowaniem metod eksperymentalnych oraz modelowych. Wybrane Problemy Inżynierskie; 2010.Search in Google Scholar

[31] Roliński Z. Tensometria oporowa: podstawy teoretyczne i przykłady zastosowań. Warszawa: WNT; 1981.Search in Google Scholar

[32] Hyla I, Śleziona J. Kompozyty: elementy mechaniki i projektowania. Gliwice: Wydawnistwo Politechniki Śląskiej; 2004.Search in Google Scholar

© 2021 Daria Żuk et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Effects of Material Constructions on Supersonic Flutter Characteristics for Composite Rectangular Plates Reinforced with Carbon Nano-structures

- Processing of Hollow Glass Microspheres (HGM) filled Epoxy Syntactic Foam Composites with improved Structural Characteristics

- Investigation on the anti-penetration performance of the steel/nylon sandwich plate

- Flexural bearing capacity and failure mechanism of CFRP-aluminum laminate beam with double-channel cross-section

- In-Plane Permeability Measurement of Biaxial Woven Fabrics by 2D-Radial Flow Method

- Regular Articles

- Real time defect detection during composite layup via Tactile Shape Sensing

- Mechanical and durability properties of GFRP bars exposed to aggressive solution environments

- Cushioning energy absorption of paper corrugation tubes with regular polygonal cross-section under axial static compression

- An investigation on the degradation behaviors of Mg wires/PLA composite for bone fixation implants: influence of wire content and load mode

- Compressive bearing capacity and failure mechanism of CFRP–aluminum laminate column with single-channel cross section

- Self-Fibers Compacting Concrete Properties Reinforced with Propylene Fibers

- Study on the fabrication of in-situ TiB2/Al composite by electroslag melting

- Characterization and Comparison Research on Composite of Alluvial Clayey Soil Modified with Fine Aggregates of Construction Waste and Fly Ash

- Axial and lateral stiffness of spherical self-balancing fiber reinforced rubber pipes under internal pressure

- Influence of technical parameters on the structure of annular axis braided preforms

- Nano titanium oxide for modifying water physical property and acid-resistance of alluvial soil in Yangtze River estuary

- Modified Halpin–Tsai equation for predicting interfacial effect in water diffusion process

- Experimental research on effect of opening configuration and reinforcement method on buckling and strength analyses of spar web made of composite material

- Photoluminescence characteristics and energy transfer phenomena in Ce3+-doped YVO4 single crystal

- Influence of fiber type on mechanical properties of lightweight cement-based composites

- Mechanical and fracture properties of steel fiber-reinforced geopolymer concrete

- Handcrafted digital light processing apparatus for additively manufacturing oral-prosthesis targeted nano-ceramic resin composites

- 3D printing path planning algorithm for thin walled and complex devices

- Material-removing machining wastes as a filler of a polymer concrete (industrial chips as a filler of a polymer concrete)

- The electrochemical performance and modification mechanism of the corrosion inhibitor on concrete

- Evaluation of the applicability of different viscoelasticity constitutive models in bamboo scrimber short-term tensile creep property research

- Experimental and microstructure analysis of the penetration resistance of composite structures

- Ultrasensitive analysis of SW-BNNT with an extra attached mass

- Active vibration suppression of wind turbine blades integrated with piezoelectric sensors

- Delamination properties and in situ damage monitoring of z-pinned carbon fiber/epoxy composites

- Analysis of the influence of asymmetric geological conditions on stability of high arch dam

- Measurement and simulation validation of numerical model parameters of fresh concrete

- Tuning the through-thickness orientation of 1D nanocarbons to enhance the electrical conductivity and ILSS of hierarchical CFRP composites

- Performance improvements of a short glass fiber-reinforced PA66 composite

- Investigation on the acoustic properties of structural gradient 316L stainless steel hollow spheres composites

- Experimental studies on the dynamic viscoelastic properties of basalt fiber-reinforced asphalt mixtures

- Hot deformation behavior of nano-Al2O3-dispersion-strengthened Cu20W composite

- Synthesize and characterization of conductive nano silver/graphene oxide composites

- Analysis and optimization of mechanical properties of recycled concrete based on aggregate characteristics

- Synthesis and characterization of polyurethane–polysiloxane block copolymers modified by α,ω-hydroxyalkyl polysiloxanes with methacrylate side chain

- Buckling analysis of thin-walled metal liner of cylindrical composite overwrapped pressure vessels with depressions after autofrettage processing

- Use of polypropylene fibres to increase the resistance of reinforcement to chloride corrosion in concretes

- Oblique penetration mechanism of hybrid composite laminates

- Comparative study between dry and wet properties of thermoplastic PA6/PP novel matrix-based carbon fibre composites

- Experimental study on the low-velocity impact failure mechanism of foam core sandwich panels with shape memory alloy hybrid face-sheets

- Preparation, optical properties, and thermal stability of polyvinyl butyral composite films containing core (lanthanum hexaboride)–shell (titanium dioxide)-structured nanoparticles

- Research on the size effect of roughness on rock uniaxial compressive strength and characteristic strength

- Research on the mechanical model of cord-reinforced air spring with winding formation

- Experimental study on the influence of mixing time on concrete performance under different mixing modes

- A continuum damage model for fatigue life prediction of 2.5D woven composites

- Investigation of the influence of recyclate content on Poisson number of composites

- A hard-core soft-shell model for vibration condition of fresh concrete based on low water-cement ratio concrete

- Retraction

- Thermal and mechanical characteristics of cement nanocomposites

- Influence of class F fly ash and silica nano-micro powder on water permeability and thermal properties of high performance cementitious composites

- Effects of fly ash and cement content on rheological, mechanical, and transport properties of high-performance self-compacting concrete

- Erratum

- Inverse analysis of concrete meso-constitutive model parameters considering aggregate size effect

- Special Issue: MDA 2020

- Comparison of the shear behavior in graphite-epoxy composites evaluated by means of biaxial test and off-axis tension test

- Photosynthetic textile biocomposites: Using laboratory testing and digital fabrication to develop flexible living building materials

- Study of gypsum composites with fine solid aggregates at elevated temperatures

- Optimization for drilling process of metal-composite aeronautical structures

- Engineering of composite materials made of epoxy resins modified with recycled fine aggregate

- Evaluation of carbon fiber reinforced polymer – CFRP – machining by applying industrial robots

- Experimental and analytical study of bio-based epoxy composite materials for strengthening reinforced concrete structures

- Environmental effects on mode II fracture toughness of unidirectional E-glass/vinyl ester laminated composites

- Special Issue: NCM4EA

- Effect and mechanism of different excitation modes on the activities of the recycled brick micropowder

Articles in the same Issue

- Effects of Material Constructions on Supersonic Flutter Characteristics for Composite Rectangular Plates Reinforced with Carbon Nano-structures

- Processing of Hollow Glass Microspheres (HGM) filled Epoxy Syntactic Foam Composites with improved Structural Characteristics

- Investigation on the anti-penetration performance of the steel/nylon sandwich plate

- Flexural bearing capacity and failure mechanism of CFRP-aluminum laminate beam with double-channel cross-section

- In-Plane Permeability Measurement of Biaxial Woven Fabrics by 2D-Radial Flow Method

- Regular Articles

- Real time defect detection during composite layup via Tactile Shape Sensing

- Mechanical and durability properties of GFRP bars exposed to aggressive solution environments

- Cushioning energy absorption of paper corrugation tubes with regular polygonal cross-section under axial static compression

- An investigation on the degradation behaviors of Mg wires/PLA composite for bone fixation implants: influence of wire content and load mode

- Compressive bearing capacity and failure mechanism of CFRP–aluminum laminate column with single-channel cross section

- Self-Fibers Compacting Concrete Properties Reinforced with Propylene Fibers

- Study on the fabrication of in-situ TiB2/Al composite by electroslag melting

- Characterization and Comparison Research on Composite of Alluvial Clayey Soil Modified with Fine Aggregates of Construction Waste and Fly Ash

- Axial and lateral stiffness of spherical self-balancing fiber reinforced rubber pipes under internal pressure

- Influence of technical parameters on the structure of annular axis braided preforms

- Nano titanium oxide for modifying water physical property and acid-resistance of alluvial soil in Yangtze River estuary

- Modified Halpin–Tsai equation for predicting interfacial effect in water diffusion process

- Experimental research on effect of opening configuration and reinforcement method on buckling and strength analyses of spar web made of composite material

- Photoluminescence characteristics and energy transfer phenomena in Ce3+-doped YVO4 single crystal

- Influence of fiber type on mechanical properties of lightweight cement-based composites

- Mechanical and fracture properties of steel fiber-reinforced geopolymer concrete

- Handcrafted digital light processing apparatus for additively manufacturing oral-prosthesis targeted nano-ceramic resin composites

- 3D printing path planning algorithm for thin walled and complex devices

- Material-removing machining wastes as a filler of a polymer concrete (industrial chips as a filler of a polymer concrete)

- The electrochemical performance and modification mechanism of the corrosion inhibitor on concrete

- Evaluation of the applicability of different viscoelasticity constitutive models in bamboo scrimber short-term tensile creep property research

- Experimental and microstructure analysis of the penetration resistance of composite structures

- Ultrasensitive analysis of SW-BNNT with an extra attached mass

- Active vibration suppression of wind turbine blades integrated with piezoelectric sensors

- Delamination properties and in situ damage monitoring of z-pinned carbon fiber/epoxy composites

- Analysis of the influence of asymmetric geological conditions on stability of high arch dam

- Measurement and simulation validation of numerical model parameters of fresh concrete

- Tuning the through-thickness orientation of 1D nanocarbons to enhance the electrical conductivity and ILSS of hierarchical CFRP composites

- Performance improvements of a short glass fiber-reinforced PA66 composite

- Investigation on the acoustic properties of structural gradient 316L stainless steel hollow spheres composites

- Experimental studies on the dynamic viscoelastic properties of basalt fiber-reinforced asphalt mixtures

- Hot deformation behavior of nano-Al2O3-dispersion-strengthened Cu20W composite

- Synthesize and characterization of conductive nano silver/graphene oxide composites

- Analysis and optimization of mechanical properties of recycled concrete based on aggregate characteristics

- Synthesis and characterization of polyurethane–polysiloxane block copolymers modified by α,ω-hydroxyalkyl polysiloxanes with methacrylate side chain

- Buckling analysis of thin-walled metal liner of cylindrical composite overwrapped pressure vessels with depressions after autofrettage processing

- Use of polypropylene fibres to increase the resistance of reinforcement to chloride corrosion in concretes

- Oblique penetration mechanism of hybrid composite laminates

- Comparative study between dry and wet properties of thermoplastic PA6/PP novel matrix-based carbon fibre composites

- Experimental study on the low-velocity impact failure mechanism of foam core sandwich panels with shape memory alloy hybrid face-sheets

- Preparation, optical properties, and thermal stability of polyvinyl butyral composite films containing core (lanthanum hexaboride)–shell (titanium dioxide)-structured nanoparticles

- Research on the size effect of roughness on rock uniaxial compressive strength and characteristic strength

- Research on the mechanical model of cord-reinforced air spring with winding formation

- Experimental study on the influence of mixing time on concrete performance under different mixing modes

- A continuum damage model for fatigue life prediction of 2.5D woven composites

- Investigation of the influence of recyclate content on Poisson number of composites

- A hard-core soft-shell model for vibration condition of fresh concrete based on low water-cement ratio concrete

- Retraction

- Thermal and mechanical characteristics of cement nanocomposites

- Influence of class F fly ash and silica nano-micro powder on water permeability and thermal properties of high performance cementitious composites

- Effects of fly ash and cement content on rheological, mechanical, and transport properties of high-performance self-compacting concrete

- Erratum

- Inverse analysis of concrete meso-constitutive model parameters considering aggregate size effect

- Special Issue: MDA 2020

- Comparison of the shear behavior in graphite-epoxy composites evaluated by means of biaxial test and off-axis tension test

- Photosynthetic textile biocomposites: Using laboratory testing and digital fabrication to develop flexible living building materials

- Study of gypsum composites with fine solid aggregates at elevated temperatures

- Optimization for drilling process of metal-composite aeronautical structures

- Engineering of composite materials made of epoxy resins modified with recycled fine aggregate

- Evaluation of carbon fiber reinforced polymer – CFRP – machining by applying industrial robots

- Experimental and analytical study of bio-based epoxy composite materials for strengthening reinforced concrete structures

- Environmental effects on mode II fracture toughness of unidirectional E-glass/vinyl ester laminated composites

- Special Issue: NCM4EA

- Effect and mechanism of different excitation modes on the activities of the recycled brick micropowder

![Figure 1

(a) Crusher – a stand for processing composite materials and (b) view of polyester–glass granules with the grain size ≤ 1.2 mm [6,8].](/document/doi/10.1515/secm-2021-0065/asset/graphic/j_secm-2021-0065_fig_001.jpg)