Abstract

This study presents an integrated analysis of two nineteenth-century gunflint workshops located in the Wadi Sannur (Eastern Desert, Egypt) and dated from Mehemed Ali’s reign. Our research focuses on the technological analysis of the lithic production from excavated assemblages and a broader survey of the mining area. The workshops are organized in both extraction and manufacturing zones, indicating segmentation of the knapping activities and craft specialization. The lithic assemblages – comprising 4,006 artifacts from four workstations – demonstrate a gunflint manufacturing process similar to those observed in Western Europe. The technological framework of these workstations suggests a flexible organization of knapping stages between the two sites. This raises questions about the identity of the craftspeople and the labor organization within the quarry’s lifespan. The dominant technique involves an integrated blade–debitage system producing standardized, rectangular gunflints of French-English style. Lithic evidence suggests the adoption of a Western European-inspired knapping tradition, aligning with the introduction of imported muskets and locally manufactured French-style firearms in the Egyptian army. Additionally, a secondary technique indicates the presence of Mediterranean-style gunflint production in select workstations. The coexistence of these technical traditions highlights the transfer of chert knapping expertise toward military-industrial strategies under Mehemed Ali’s modernization efforts. It also underscores the complexity of technological transmission in lithic production, shaped by both cultural traditions and functional military requirements.

1 Introduction

Gunflint manufacture has been well-documented as a key technique in craftsmanship since the nineteenth century and is gaining increasing recognition in modern archaeological contexts. Although gunflint production was initially documented through ethnographic studies – using oral surveys, photographs, and film recordings – there is still only limited archaeological evidence where the entire manufacturing process has been observed (Barandiarán Maestu, 1974). In Europe, this is largely because quarries are difficult to identify due to the geomorphological evolution of the landscape. Additionally, the separation of extraction and manufacturing areas in most factories (Woodall et al., 1997) increases the difficulty of identifying the entire process. In the Cher’s Valley (France), for instance, extraction areas have often been filled in, while manufacturing areas were located in domestic areas within villages that have been transformed over centuries (Emy, 1978). Comparatively, these productions remain unknown or invisible in other regions, such as in Northern Africa or the Middle East, because they have never been recorded, even though such items were clearly used and likely produced. This lack of documentation in these geographical areas is largely due to research investments being focused primarily on Western European productions, particularly from France and England, which also played a significant role in the emergence and the global distribution of these products (Emy, 1978; Weiner, 2016; Whittaker & Levin, 2019; Witthoft, 1966). As a result, some production sites have become more visible due to their industrial nature and their longstanding duration, such as those in Suffolk (England) or the Cher’s Valley (France) (Barnes, 1937; Clarke, 1935; Emy, 1978; Gould, 1981; Whittaker, 2001). Although some workshops are still operational in England or in France, the archaeological record remains the most reliable source of information about this historical tradition (Ballin, 2012; Barandiarán Maestu, 1974; Chelidonio et al., 2019; Woodall et al., 1997). Therefore, researching such productions in Egypt is particularly valuable, as gunflints documentation on the southern bank of the Mediterranean basin remains limited. In addition, it provides further insights into the history of techniques and the historical or political events involved in such industrial processes.

1.1 Overview of Gunflints Research

Gunflint production in Europe emerged in the sixteenth century with the development of flintlock firearms. This technology, based on the use of a chert piece, was primarily employed for igniting gunpowder and firing guns (Austin, 2011; Barandiarán Maestu, 1974; Chelidonio, 1987; Ciarlo et al., 2019; Dolomieu, 1797; Edeine, 1963; Emy, 1978; Emy & de Tinguy, 1964; Kenmotsu, 1990; Kent, 1983; Skertchly, 1879; Witthoft, 1966). The increasing use of “flintlocks” during the seventeenth century contributed to the spread of this technology, gradually reaching many parts of the world under European influence. The distribution of gunflint production followed the adoption of firearms, propelled by both armed conflicts and established trade routes (Austin, 2011; Ciarlo et al., 2019). While this technology had long been well practiced, its industrial character gradually emerged as it became part of the military supply chain controlled by the political powers of Western countries (Emy, 1978). This industrial process (Caliste & Carnino, 2022; Jarrige, 2021) is primarily characterized by massive, standardized production, which involves specialization and segmentation tailored to military or commercial needs. France and England have been considered the major providers through military conflicts and commercial markets for nearly three centuries worldwide (Ballin, 2012; Emy, 1978; Kent, 1983; Whittaker & Levin, 2019; Witthoft, 1966). However, the process of manufacturing gunflints may have spread unevenly across different regions, making certain productions more difficult to identify in the historical record (Whittaker & Levin, 2019). Given this scarcity, evidence of autonomous production, as revealed through collections of military objects or archaeological records, is of particular interest.

More broadly, two major issues have traditionally been observed from historical and archaeological records at different scales: on one hand, viewing the gunflint as an isolated artifact, and on the other hand, considering the whole manufacturing process. The first involves identifying gunflints that have been found in the archaeological context, as chronological markers that highlight their typology, and the historical dynamics related to their context of discovery (Hamilton, 1964; Witthoft, 1966). Beyond offering limited chronological data (Hamilton, 1980; Hamilton & Emery, 1988; Hamilton & Fry, 1975), various inferences can be drawn from raw materials, morphology, and style (Austin, 2011). The type of raw materials used is commonly accepted as evidence of provenance (Werra et al., 2019); however, some materials can be confusing macroscopically (Austin, 2011; Ballin, 2012; Durst, 2009; Horowitz & Watt, 2019), and there may be segmentation in the production chain across different countries (Emy, 1978, p. 119; Witthoft, 1966, p. 41). Morphology and style define an archaeological typology and differ from the original typologies adopted by factories for commercial needs. Gunflint types are primarily interpreted through chronological criteria, indicators of manufacturing techniques, evidence of specific weapons, and/or resulting as different technical processes associated with the country of production (Ballin, 2012, 2014; Buscaglia et al., 2016; Chelidonio, 2013; De Lotbiniere, 1977, 1980, 1984; Kenmotsu, 1990; Luedkte, 1999; Witthoft, 1966). This has been traditionally seen with the so-called French and British styles, which differ mainly in the transition from “D-shape” to “rectangular” forms (Austin, 2011; Ballin, 2012, 2014; Barnes, 1937; De Lotbiniere, 1984; Whittaker, 2001). Although none of these criteria is fully diagnostic (Ballin, 2012), they are useful for understanding an almost universal mode of distribution, often linked to major historical events. In this sense, gunflint production also documents processes of military industrialization driven by centralized policies and linked to major armed conflicts or commercial trade.

The second issue, which is more challenging in the absence of remains related to the production chain, concerns understanding the skills associated with the technical processes and the entire chaîne opératoire (Lemonnier, 1986), from production to use and discard. This has primarily been applied to French and English factories demonstrating industrial production from the end of the nineteenth to the twentieth centuries (Barnes, 1937; Clarke, 1935; De Mortillet, 1908; Dolomieu, 1797; Edeine, 1963; Evans, 1872; Lovett, 1887; Salmon, 1885; Schleicher, 1910, 1927; Skertchly, 1879), focusing in particular on labor organization (namely, segmentation or the gendered division of labor) and the working conditions for craftspeople within an ethnographic or historical perspective (Clarke, 1935; Emy, 1978; Lovett, 1887; Skertchly, 1879). This study of the production chain has also been developed in archaeological contexts such as in Italy, France, Spain, and Scotland (Ballin, 2012; Barandiarán Maestu, 1974; Chelidonio & Woodall, 2017; Weiner, 2017). Furthermore, the study of manufacturing techniques and methods has revealed a technical convergence in the field of flintknapping, particularly with respect to prehistoric times, highlighting the retroactive nature of the lithic technologies (Barnes, 1937; Clarke, 1935; Emy, 1978, p. 9; Skertchly, 1879). This anthropological dimension, prominent in early surveys, has facilitated an understanding of the phenomenon and its various stages.

Here we are investigating these two issues through the archaeological record, focusing on both the gunflints and the manufacturing process. This study is based on the discovery of a gunflint factory in the Egyptian eastern desert (Northern Galala), dated from Mehemed Ali’s reign in the first half of the nineteenth century. This discovery, initially identified by German botanist A. Schweinfurth (1885) at the end of the nineteenth century, appears to be the earliest evidence of gunflint production in this geographical area. According to this record, historical sources and archaeological data from two sites, it appears to have been exploited for the military supply of Mehemed Ali’s armies between 1810 and 1830. These quarries, which include extensive extraction and manufacturing areas, provide an exceptional example for documenting the production process. They are particularly well preserved due to the dry conditions and their unique desert location, which is a significant advantage. It allows us to precisely describe the technical traditions observed in the archaeological context, placing them within the broader historical framework of Egypt during the reign of Mehmed Ali.

1.2 Gunflints and the History of the Egyptian Armies

From the beginning of the nineteenth century, Egypt’s history is marked by several conflicts, including the defeats of the French armies (1801–1803) and the persistent struggles related to the rise of Mehemed Ali between 1803 and 1805 (Al-Sayyid Marsot, 1984; Fahmy, 2009). This rise to power gradually led to the independence of Egypt from the Ottoman Empire and the renegotiation of alliances with Western empires. The political and economic development initiated at the beginning of Mehemed Ali’s reign is notably characterized by the rise of a new army (Douin, 1923; Dunn, 1993; Fahmy, 1997; Farhi, 1972; Guémard, 1836; Gouin, 1847) as a tool for political control (Fahmy, 1997). The state’s mastery over armies appears to align with the broader advancements in military armament observed within the Ottoman Empire from the eighteenth to the nineteenth centuries (Grant, 1999; Krause, 1992). In this military upgrade, firearms were initially imported from Europe before local production began. This influx of military goods was accompanied by the transfer of technical skills to the armament industry. This was facilitated by the intervention of mercenaries from Western European countries, preceding the autonomous development of the new military industry (Douin, 1923; Dunn, 1993; Gouin, 1847; Guémard, 1936). Regarding the gun supply, French muskets were first imported in 1821 and 1824 (Guémard, 1936, p. 118, 131) and powder from England. Gun, powder, and cannon manufactures have been developed in Cairo since the 1820s (Guémard, 1936; Planat, 1830; Rochefort Scott, 1837; Russell, 1835), using the expertise of European mercenaries. The French flintlock model “1777 modifié An IX” was manufactured at Cairo’s Citadel and adopted by the new regular troops (Bowring, 1840, p. 144; Guémard, 1936, p. 141; Planat, 1830, p. 87, 350; Rochfort Scott, 1837, pp. 164–166). This upgrade had to adapt to new political needs, consolidating the economic independence of the military system and leading to the establishment of autonomous factories managed by foreign advisers.

Until recently, there have been few mentions of gunflint production in Egypt (Clarke, 1935). In addition to a site mentioned in the Galala, a manufacturing site has been reported in the village of Abu Rawach (Schweinfurth, 1885). Historical sources indicate that gunflints were used for flintlocks and pistols by Mamelukes and armed troops in Egypt during the first half of the nineteenth century (Bardin, 1851). However, its supply was likely limited by opportunistic self-procurement and manufacturing (Bardin, 1851; Emy, 1978, p. 144). Although little is known about the supply of gunflints to the Ottoman armies, it is likely that Mehmed Ali recognized their strategic importance and took measures to ensure they were adequately supplied. The creation of new troops through conscription increased the demand for ammunition and gunflints, as the supply of guns was adapted to meet this need (Guémard, 1936, p. 152). Here, gunflint production during Mehemed Ali’s reign represents new evidence for the industrialization process involved in the Egyptian army (Fahmy, 1997, 2009). Nevertheless, the evidence of such standardized production raises questions about the political initiative and the introduction of new skills.

2 Methods and Assemblages

Our study is based on an extensive survey conducted at two sites (WS003 and WS004), located in the Eastern Egyptian desert, in the Wadi Sannur area, Northern Galala (Figures 1 and 2; for further documentation, see Figures A1 and A2). They were discovered as part of a French archaeological mission that has been ongoing since 2014, focusing on Pharaonic chert quarries (Briois & Midant-Reynes, 2014; Briois et al., 2021; Briois et al., 2024). This study conducted from 2022 to 2024 included surface surveys, excavation, and artifact analysis. For each site, we can distinguish an extraction area characterized by the quarry face and spoil heaps, and a manufacturing area composed of several lithic concentrations related to gunflints production. The raw material exploited is a grey translucent chert from the El Fashn Middle Eocene Formation of the Northern Galala (Bishay, 1966), composed of microcrystalline quartz (Hamdam, & Jeuthe, 2022) and exhibiting various microfossils, such as large benthic foraminiferas. The lithic elements identified as production waste include cores, flakes, blades, and gunflints resulting from the manufacturing process.

Location of the Wadi Sannur, Eastern Desert Egypt. Focus on the WS003 location, near the Pharaonic miners’ camps, Wadi Umm Nikhaybar (map and survey ©IFAO M. Gaber). (A) Ramessid building, (B and C) manufacturing area, and (D) extraction area.

General view of the two sites, Wadi Sannur. (1) General view of the WS003 site from the Wadi Nikhaybar. (2) General view of the WS004 site showing the quarry front at the mining area (photo P.-A. Beauvais).

In a previous study (Beauvais, 2024), we compared these two sites that we attribute to the same factory, proposing a gunflint typology and hypothesizing style and their functional purposes. Here, we propose to revisit these outcomes, quantifying the technological observations and focusing on the issue of skill transfer based on the entire chaîne opératoire. This initial overview, which addressed a broader historical scale, allowed us to highlight the occupation of these desert areas and compare them to Pharaonic contexts. Following recent excavations at these two sites, we are focusing here on the lithic assemblages, providing additional data related to various methods and techniques. The lithic concentrations document several technical stages within a chaîne opératoire model, based on the literature. We are presenting the results of an analysis conducted on a set of 4,006 pieces whose dimensions are up to 2 cm, issued from five assemblages excavated across the two sites. This analysis includes planimetric surveys during excavation, multiple refits, and a technological study utilizing the French technological school’s method (Inizan et al., 1999), adopting the terminology used in gunflint studies (as per Ballin, 2012). A typology is proposed based on the morphometric and technological criteria of the manufactured pieces. Using data from the literature on Western European contexts, we compare the manufacturing processes to understand the origins and the establishment of these skills.

3 Results

3.1 Description of the Sites and Assemblages

The first site WS003 is located on the slope of the Wadi Umm Nikhaybar, a tributary of the Wadi Sannur. The site is composed of an extraction area at the bottom of a wadi (dry valley or channel outside of the rainy season), while the workshop area is located nearby, up on the plateau (Figures 1 and 2). This gunflint factory has been confused with some workshops from the Pharaonic periods (Harrell, 2024) since it is located a few hundred meters away from a miners’ camp currently being excavated and dated to the Old Kingdom (Briois et al., 2021; Briois et al., 2024). The extraction area appears to follow the natural wadi bed, where a quarry face and spoil piles can be observed. These piles consist of regular limestone blocks resulting from the exploitation of chert bands. The manufacturing area is located just above, near a collapsed building interpreted as a fort from the Ramessid period, based on pottery artifacts identified in the vicinity (Harrell, 2012, 2024, pp. 392–394). The lithic remains are observed both inside and around the site, covering an extensive area of approximately 600 m2 on average and extending onto the wadi flank (Figure 2). Although some parts of the area and the building have recently deteriorated, several concentric heaps can still be seen within this waste slick, indicating the presence of different workstations. Thirty-two of these workstations can be identified. Besides lithic remains, fragments of modern pottery and long-stemmed tobacco pipes are observed within the manufacturing area or its vicinity. Two lithic assemblages have been considered among the 32 concentrations observed in this area. The first (WS003.9) corresponds to a small lithic accumulation measuring 3 m long by 2 m wide, divided into two parts and located on a natural slope among other similar concentrations. The lithic remains include cores, flakes, fragmented and entire blades, chunks, and various gunflints. The second assemblage (WS003.15) is part of aggregated concentrations, located 80 m away near the Ramessid fort and the main accumulation area. The lithic remains in this assemblage consist only of fragmented blades, chunks, and gunflints, while the other associated concentrations are composed of cores, entire blades, and flakes. An additional assemblage of 34 gunflints was collected through a survey around the Ramessid fort within the manufacturing area and added to the other assemblages to provide a more significant sample.

The second site (WS004), located on the plateau 2 km west of the first, consists of an extensive workshop area that partially covers a mining trench and some lithic remains from a pharaonic quarry. Several loci can be identified: the main excavated area, resulting from the quarrying activity and covering approximately 300 m2, is almost entirely filled by a large spoil heap and includes a quarry face between 2 and 3 m deep (Figure 2). This quarry is partially surrounded by a vast lithic accumulation similar to site WS003, which corresponds to the manufacture area. A second excavated area was also observed, along with empty spaces behind the spoil heap that suggest the presence of dwelling structures. Some fragments of modern pottery and evidence of old fires on the ground (combustion marks) support this hypothesis (Figures A3 and A4). A short distance from the main knapping area, separated by a small wadi, there is a second zone consisting of three concentrations of lithic remains arranged in a sub-circular pattern. Some depressions noticed in their centers, along with the circular shape of certain concentrations, suggest the presence of dwelling structures or different workstations (Beauvais, 2024). The lithic concentrations observed in the workshop area consist of debitage waste such as flakes, cores, blades, and chunks. The two assemblages collected in the main sector are part of overlapping clustered accumulations. One assemblage (WS004.7) corresponds to a 1 m-diameter concentration of 153 lithic pieces, including cores, blades, and flakes (Figure A5). The other one (WS004.8) involves a selective collection of 49 blades, which are part of a larger lithic concentration (Figure 3, no 2).

Key features of the site. (1) Pile of discarded lithic cores (photo B. Midant-Reynes). (2) lithic blades forming part of a major concentration (WS004.8), indicative of the artifact density on the site (photo P.-A. Beauvais).

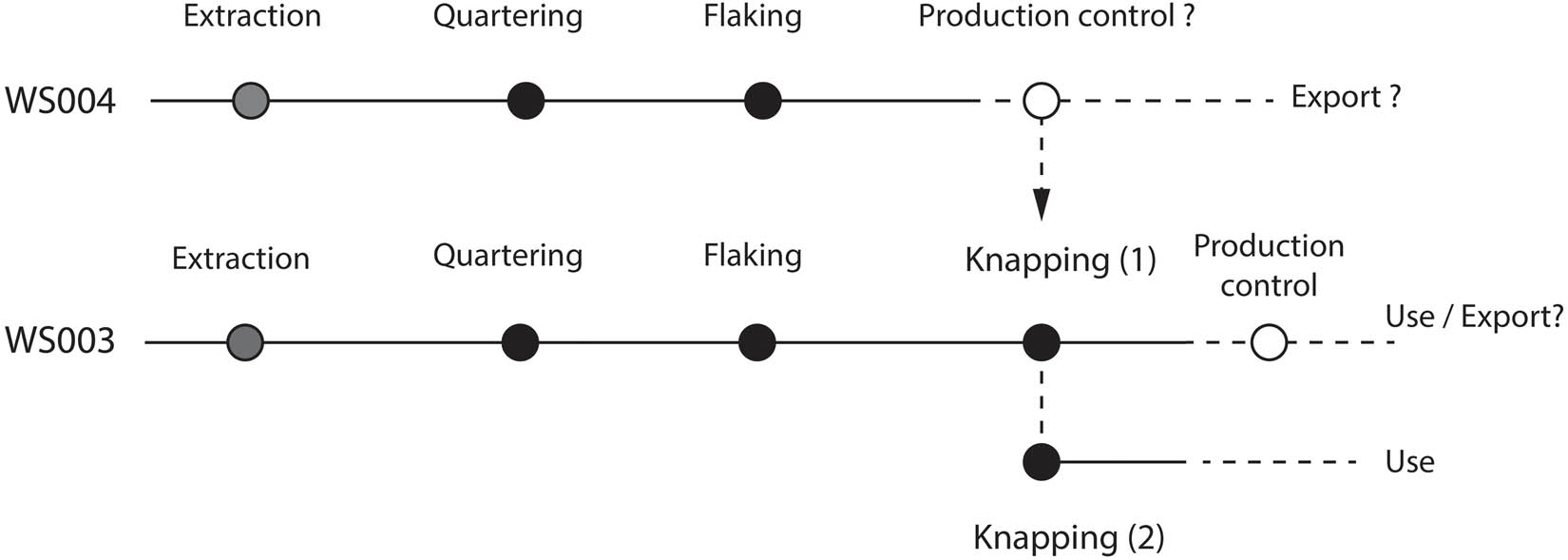

3.2 The Lithic Remains

The two manufacturing areas reflect the same spatial organization, with lithic concentrations that are either clustered or isolated, indicating a segmented manufacturing process. The four assemblages were chosen because they provide varying levels of information regarding the types of lithic remains sorted from their technological characteristics (Table 1). The fact that this production appears to be standardized in terms of the nature of the products and apparent spatial organization allows us to define the chaîne opératoire based on other industrial contexts, even though they are not contemporaneous. We used Clarke’s (1935) description, applying terminology derived from the English mining contexts. The “quartering” stage corresponds to the volume preparation, “flaking” refers to blank production and “knapping” is the final fabrication step. The two assemblages from site WS004 are exclusively devoted to extraction and the first two stages and are analyzed to describe these processes, while the assemblages from site WS003 allow us to describe all three manufacturing stages. Two technical models of gunflint manufacture, mainly based on the observation of the cores and the end products, are identified within the chaîne opératoire: one, present at both sites, produces blades, while the other that produces flakes is only attested in the WS003 site (Table 1).

Contextual information of the analyzed lithic assemblages from WS003 and W3004

| Site | General description | Elements of datation | Assemblage | Description/type of remain | Number of artifacts |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WS003 | Extraction + manufacture area | Historical record (Schweinfurth, 1885) + Lithic and pottery remains | WS003.9 | Lithic concentration − Blade and flake debitage, segmentation and retouch | 715 |

| WS003.15 | Lithic concentration − Blade segmentation and retouch | 3,055 | |||

| WS003 | Gunflints | 34 | |||

| WS004 | Extraction + manufacture area (only blank production) | Lithic and pottery remains | WS004.7 | Lithic concentration − Blade debitage | 153 |

| WS004.8 | Lithic concentration − Blades | 49 | |||

| Total artefacts | 4,006 | ||||

The first category of lithic remains found at both sites corresponds to the tabular or ovoid nodules, ranging from about 20 cm to 1 m in length, that are extracted from the limestone’s bench and transported to the manufacturing areas. Blocks are parts of the original nodules that are then divided into “quarters” by hard hammer percussion. These quarters, averaging 30 cm in length, have asymmetrical morphologies and display impact marks and large conchoidal fractures. They are often found in piles with blade cores at the WS004 site (Figure 3), near the extraction area, where they appear ready for further exploitation. These block fragments provide an adequate volume of material for the blade and flake reduction processes that follow.

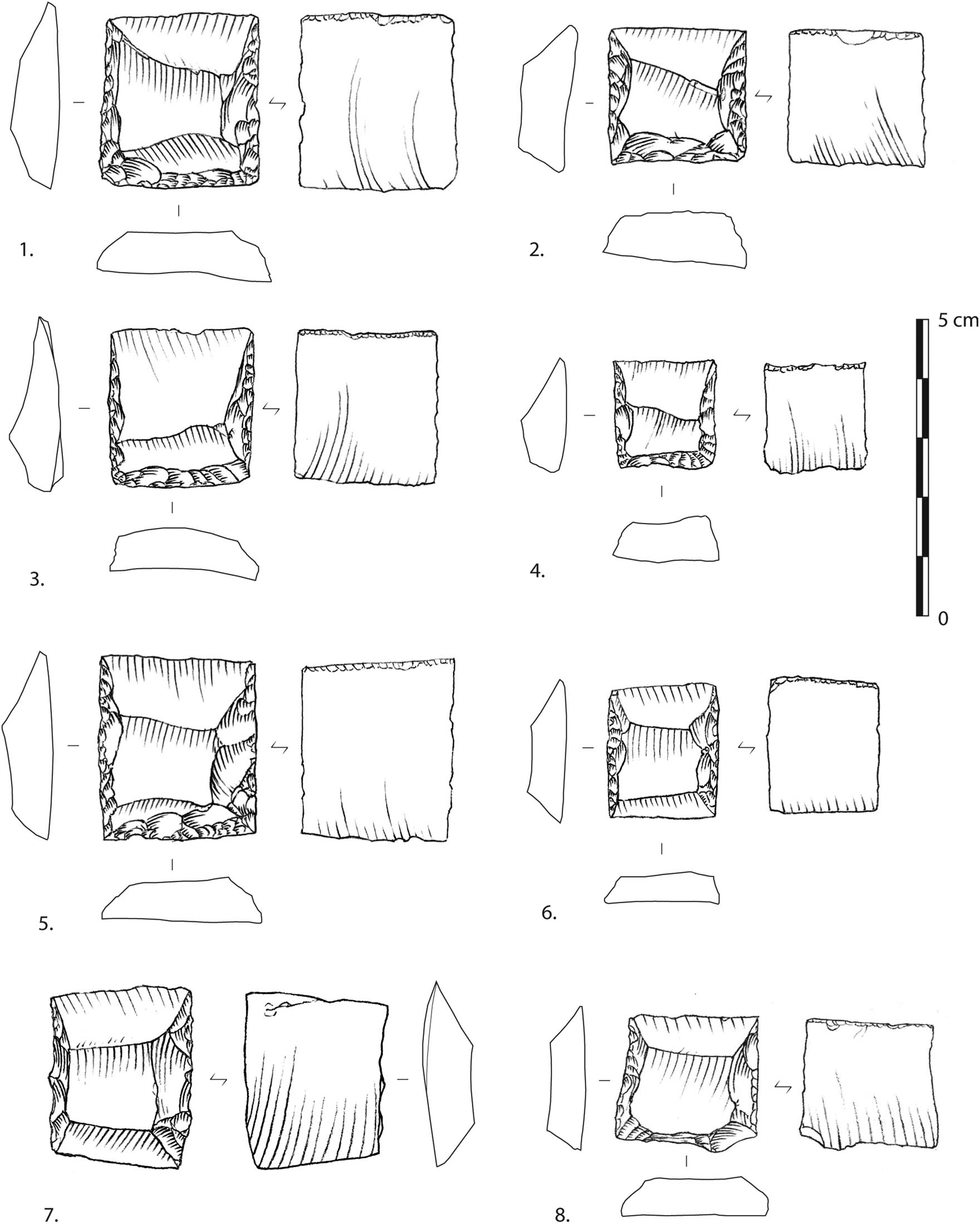

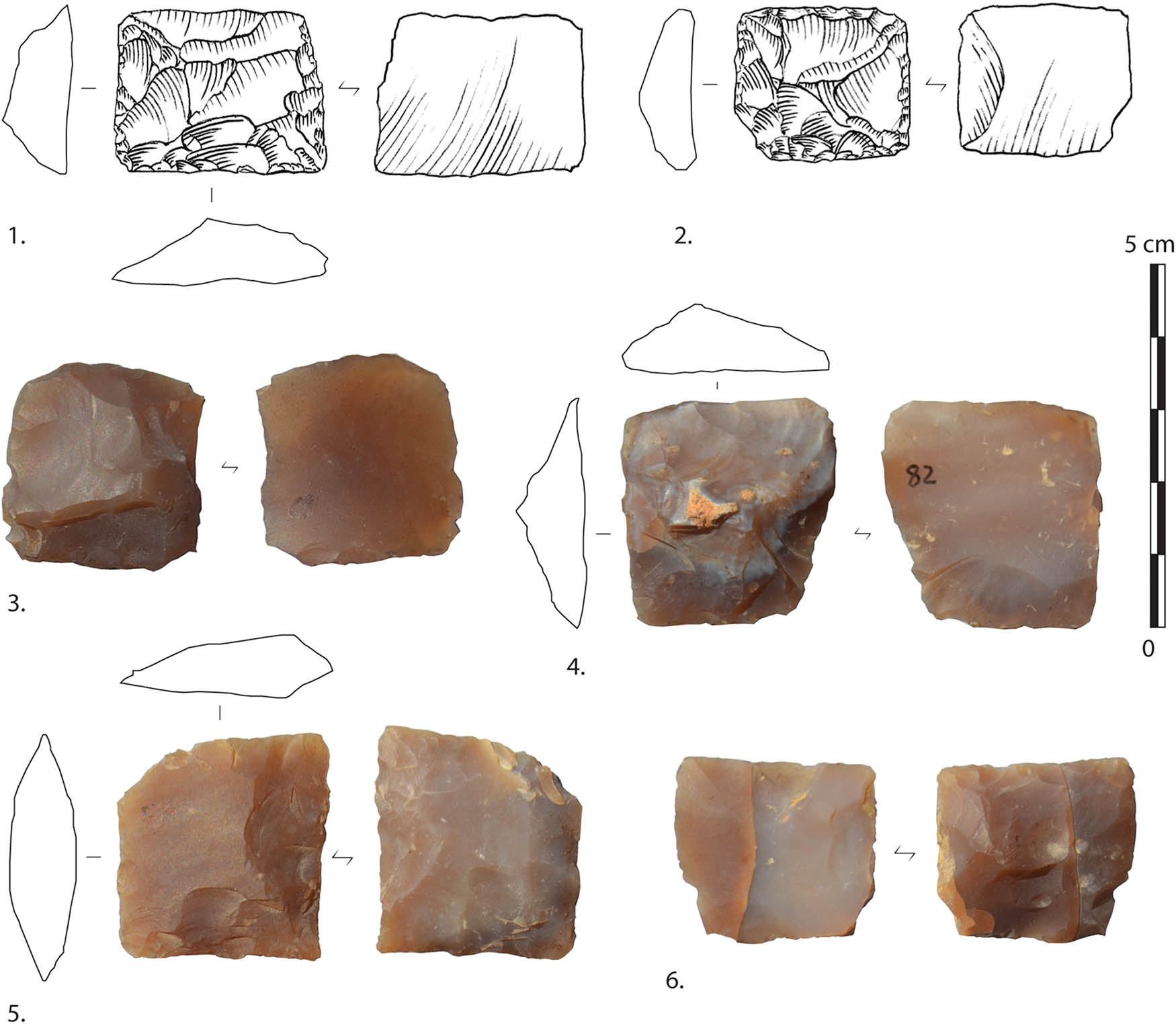

3.2.1 The Cores

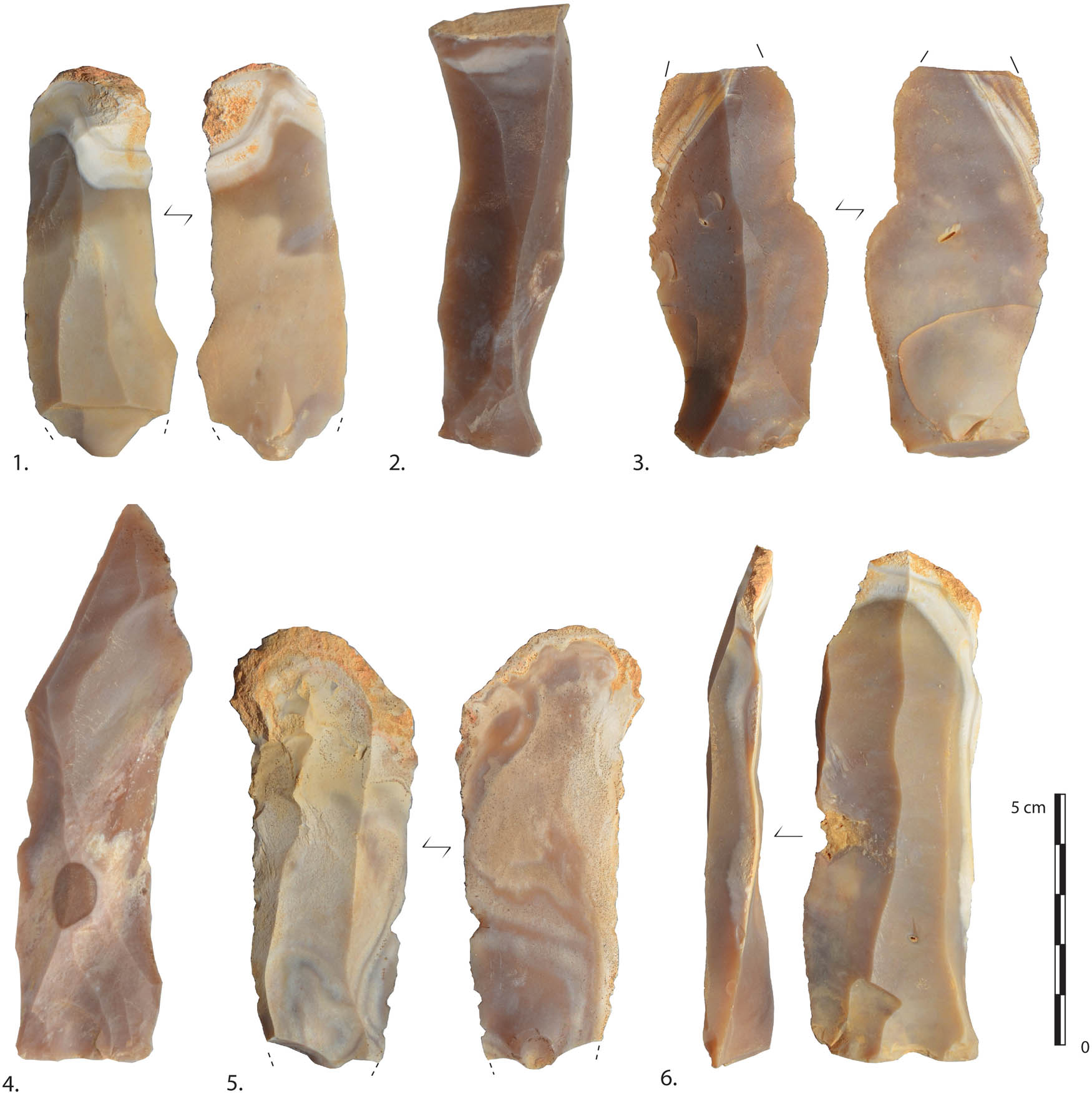

Primary observations regarding blade cores within the sites are based on the WS004.7 assemblage, which comprises 5 blade cores, 92 blades, and 52 flakes and fragments. Three cores refitted appear to originate from the same nodule divided in “quarters.” Although a significant portion of the products is missing from this assemblage, these refits reveal characteristics associated with the first two stages, “quartering” and “flaking” (Figure 4). The blade cores observed in both WS004 and WS003 sites display different morphologies, which depend on the original volume or correspond to different steps in the reduction process. The two main morphologies both combine an orthogonal platform with a unidirectional debitage surface. The first morphology, an octagonal prism, results from enveloping or full exploitation of the core volume. The second, flat cores with a natural or knapped ventral face and a dorsal knapping surface, result from semi-enveloping exploitation until the core is exhausted (Figures 4 and 5). The flat platform is usually the negative of the ventral surface’s knapped “quarters.” The refit from this assemblage shows that the initial “quarter” volumes have been knapped using the length, width, or thickness to produce a large number of blades, even if only the best are selected.

Lithic refits from WS004.7. (1) refit showing two quarters divided from the same nodule. (2) blade debitage on the first “quarter”; (3) core preparation on the second quarter. (4) exhausted core after blade debitage (refits P.-A. B. and photos B. M.-D).

Cores from WS003. (1) Blade core exhibiting a flat morphology. (2) Flake core showing centripetal removals (short and elongated flakes) (photo B. M.-R.).

Flake cores that depend on an autonomous reduction process have been found in four lithic concentrations, including WS003.9. The main morphologies correspond to flat or bi-pyramidal discoid cores, exhibiting centripetal flake removals. The blanks selected for reduction are typically block fragments or large flakes, with peripheral preparation leading to a discoid morphology. Debitage from these cores is multidirectional and produced using direct percussion, resulting in both elongated and short flakes (Figure 5). The shorter flakes are thick and removed using an internal motion, where the core is struck closer to the center, while elongated flakes are detached through a marginal motion, where the core is struck closer to the edge. The alternating removal of these two types of flakes ensures the maintenance of the core and the presence of flat surfaces, which are intentionally sought after.

3.2.2 The Blanks

Two categories of produced blades have been observed at both sites: fragmented blades showing segmentation fractures at the WS003 site and entire blades at the WS004 site (Table 2). The entire blades are additionally assigned to different categories, including cortical or partially cortical blades, as well as hinged or plunging blades with partially cortical ends (Figure 6). Based on a sample of 49 blanks from the WS004.8 concentration, the average size is 7.3 cm in length (σ = 1.8), 2.5 cm in width (σ = 0.73), and 0.76 cm in thickness (σ = 0.34). The general morphology corresponds to a straight profile with one or two central ridges and a rectilinear delineation; the distal part is slightly convergent or plunging. The proximal part exhibits a flat platform without preparation and an impact point with a complete circular ring crack, sometimes containing iron residues. The ventral face displays an overhanging platform with a prominent bulb in clear relief, bulbar fissures, and cracks, but without lipping (Figure 7, nos 8 and 9). These characteristics indicate the use of metallic hard hammer percussion. The estimated angle between the platform and the knapping surface averages around 90°. Two technical accidents are associated with the percussion: the first is a Siret fracture, which splits the blade into two parts and is often accompanied by a bulbar scar; the second is the loss of the overhang on the dorsal face of the proximal part (Figure 6). The two accidents result from a mechanical process caused by the percussion tool and the force applied by the craftsman. Blade debitage produces a large number of blades, from which the most regular ones are selected for the next step. The reduction process operates through unidirectional debitage, where each blade is produced without preparation, overlapping the previous ones in an enveloping manner. Based on the WS004.7 assemblage, we interpret the absence of most of the blades as the result of a selection process, whereas the shorter and more irregular blanks (hinged, plunging blades, curved profiles) are discarded and can be refitted later.

Technological sorting and frequencies related to different lithic remains in a selection of the assemblages

| WS003.9 | WS003.15 | WS004.8 | WS004.7 | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Technological category | N | % (N) | N | % (N) | N | N | N |

| Blade core | 1 | 0.1% | — | – | — | 5 | 6 |

| Flake core | 1 | 0.1% | — | – | — | — | 1 |

| Flake | 132 | 18.5% | 85 | 2.8% | — | 51 | 268 |

| Flake fragment | 84 | 11.7% | 22 | 0.7% | — | 1 | 107 |

| Debris | 52 | 7.3% | 430 | 14.1% | — | — | 482 |

| Entire blade | 1 | 0.1% | 8 | 0.3% | 41 | 92 | 142 |

| Bladelet | 19 | 2.7% | 25 | 0.8% | 8 | 4 | 56 |

| Fragmented blade (proximal) | 75 | 10.5% | 567 | 18.6% | — | — | 642 |

| Fragmented blade (mesial) | 52 | 7.3% | 234 | 7.7% | — | — | 286 |

| Fragmented blade (distal) | 69 | 9.7% | 208 | 6.8% | — | — | 277 |

| Retouch flake | 207 | 29.0% | 1355 | 44.4% | — | — | 1,562 |

| Gunflint preform | 3 | 0.4% | 97 | 3.2% | — | — | 100 |

| Gunflint | 19 | 2.7% | 24 | 0.8% | — | — | 43 |

| Total | 715 | 100% | 3055 | 100% | 49 | 153 | 3,972 |

Blades from two different lithic assemblages (WS004.1 and WS004.7). (1 and 5) loss of the overhang on the proximal part of the blade (photo B. M.-R.).

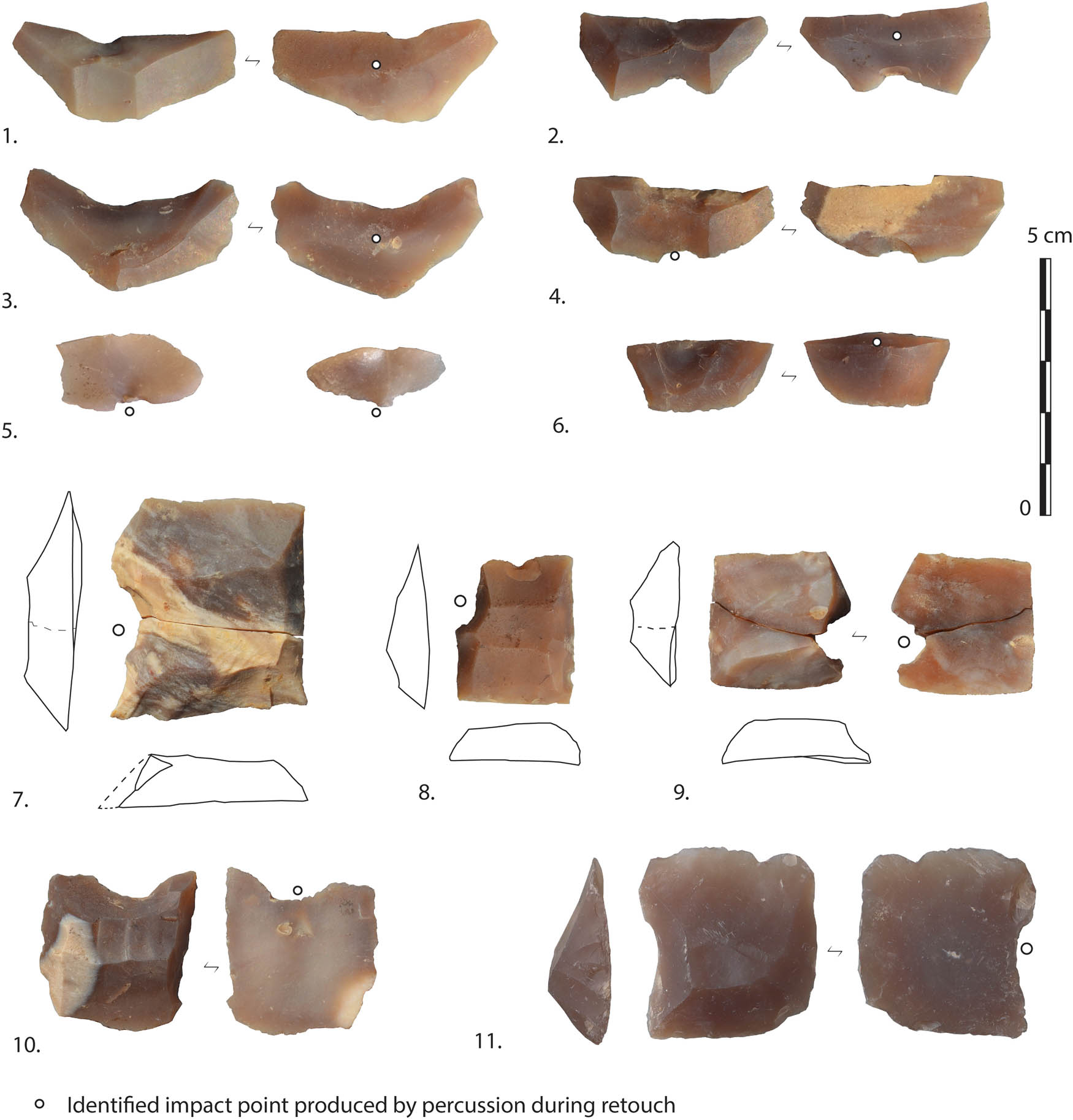

Blade fragments discarded after segmentation. The white circles indicate the location of the impact points. (1–3) Distal parts showing typical impact point locations. (4, 5, 7) Mesial parts, broken and segmented. (6) Mesial part with two impact points. (8 and 9) Proximal parts (photos B. M.-R.).

Flake blanks at the WS003 site are mainly produced during the flake reduction sequence but are also generated during blade core preparation. The proportion of flakes is well documented for WS003.9 where both types of debitage are attested. The presence of blanks is difficult to distinguish among the discarded flakes. However, it is possible to mentally reconstruct the knapping process using unfinished gunflints and flake cores in the vicinity. Flakes of sufficient size and thickness for gunflint production are detached using direct percussion in either an oblique or frontal motion from an angulated platform (estimated angle around 50°–60°), formed by the intersection of the two surfaces (Figure 5). The same platform stigmata and bulb surfaces observed in blades are present on the flakes, and the percussion negatives are highly marked on the cores. The short flakes exhibit a flat dorsal surface – originally the ventral face of the core – and a sub-triangular cross-section. This flat dorsal surface becomes the ventral face of the finished gunflint, while the retouching process shapes the former ventral face of the flake, which retains the bulb of percussion. In this model of flake debitage, the shorter flakes are selected as blanks for gunflints (Barandiarán Maestu, 1974; Chandler, 1917; Weiner, 2017). This technique closely resembles those used to produce gunspalls – or “wedge-shaped (Witthoft, 1966)” – which some authors describe as “flake-based” gunflints (Ballin, 2012). We interpret these flakes as intentional blanks produced for gunflint manufacture. However, craftsmen may have selected a wide range of products – both short and elongated flakes – for the retouching process.

3.3 Gunflints and Their Fabrication Process

The final step, observed only at the WS003 site, involves the segmentation of blanks until the final retouch. The description of the gunflints is based on the WS003.9 and WS003.15 assemblages, as well as a selected set of samples collected from the manufacturing area (Table 1). Two main types are distinguished, based on the nature of the blank and the retouch mode.

The first type of gunflint widely identified in all the lithic concentrations is a rectangular piece made from a mesial blade fragment. The lithic wastes consist of blades and flakes fragments as well as short flakes resulting from the retouch process within the WS003 site. Both assemblages primarily consist of these items, especially fragmented blades – proximal, mesial, and distal parts – that mostly show signs of segmentation (Figure 7). The straight or oblique fractures observed on the blade fragments are associated with a circular crack or an incipient demi-cone located on the dorsal or ventral surfaces, along the central debitage axis of the blank (Figure 7). These stigmata result from the percussion impact of a metallic tool. The circular crack represents the negative stigmata of the percussion, while the incipient demi-cone is the positive stigmata, caused by the counter-blow when the blank is held against an anvil (Barnes, 1937). The absence of these marks on some blade fragments may indicate incidental breakage during blade debitage or indirect breakage during the segmentation process. The frequency and morphology of these marks likely depend on factors such as the force applied by the knapper, the force transmitted back by the steel, and the type of hammer used. The position of the diagnostic marks on the dorsal or ventral faces helps determine how the blank was segmented (Barandiarán Maestu, 1974; Barnes, 1937). When one piece is produced from each blank, only the distal and proximal fragments remain; when two pieces are produced, the short mesial part – marked with double percussion – is discarded (Figure 7). In the WS003.15 and WS003.9 assemblages, blades mainly produce one piece since there is a low presence of short mesial parts showing double impact fractures. The mesial parts observed in the assemblage are discarded because they are either too short or due to irregular profiles or fractures. The wide array of short flakes associated with these fragments, ranging 0.5–2.5 cm, corresponds to the final stage of manufacturing (Figure 8). For the WS003.15 assemblage, the retouch flakes are removed in a direct motion with an anvil percussion technique; they show a surface on the ventral face and counter-blow marks, indicating the use of a steel (Barnes, 1937).

Diagnostic flakes and chips associated with the retouch process (1–6). Unfinished and broken rectangular gunflint pieces (7–10). D-shape gunflint (11) (photos B. M.-R. and P.-A.B.).

The first type of gunflints consists mostly of unfinished and finished pieces, featuring one or two arises, two or three retouched sides, and one or two leading edges with marginal and regular inverse retouch. These discarded pieces represent various stages of retouch, ranging from preform to finalized states. Our focus is on unfinished gunflints displaying initial and interrupted retouch and finished pieces exhibiting defects, irregular shapes, or breakage during the retouch process (Figure 8). On these pieces, the active part is the leading edge, corresponding to the right or left edge of the blade blank. The presence of one or two leading edges depends on the degree of retouch applied but could also define an independent category (Table 3) based on specific functional purposes. These pieces may offer two active edges, potentially extending the lifespan of the object. Based on a sample of 29 rectangular finished gunflints, the average size of these pieces ranges 2.63 cm (σ = 0.33) in length, 2.4 cm in width (σ = 0.31), and between 0.71 in thickness (σ = 0.15). A comparison between the complete blades and finished products reveals overlapping width/thickness dimensions. No distinct clusters were observed regarding the morphometry of these pieces (Figure 9).

Typology of unfinished and finished gunflints found in the assemblages

| Typology | WS003.9 | WS003.15 | WS003 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rectangular gunflint with one leading edge | 3 | 13 | 24 | 40 |

| Rectangular gunflint with two leading edges | — | — | 1 | 1 |

| Small rectangular gunflint with one leading edge | — | 6 | 4 | 10 |

| Small rectangular gunflint with two leading edges | — | 3 | 1 | 4 |

| Rectangular unfinished gunflint | 3 | 1 | 1 | 5 |

| D-shape gunflint | — | — | 2 | 2 |

| Gunflint with invasive retouch | 13 | — | — | 13 |

| Total | 19 | 23 | 33 | 75 |

Graph showing the dimensions of the blades compared to the dimensions of the gunflints (length/width; width/thickness).

Although the produced gunflints could have been highly standardized, the discarded pieces are considered non-conforming and unsuitable for further use. The gradual variation in dimensions of these final products suggests adaptation for different types of firearms, such as muskets and pistols, particularly for the smaller rectangular gunflints ranging in average, 1.9 cm (σ = 0.16) in length, 1.8 cm in width (σ = 0.16), and between 0.56 in thickness (σ = 0.13). In terms of typology, the rectangular gunflint (N = 54) is traditionally associated with British style, in contrast to the convex “D-shape” characteristic of the French style seen in a limited range of pieces (N = 2). However, this assumption remains unclear and does not lead to definitive conclusions regarding the influence of style and expertise developed at this factory.

The second type is a rectangular gunflint with irregular edges, shaped by invasive retouch and produced from flake blanks (Figure 10). These pieces, found only in certain concentrations, are shaped using unifacial techniques and exhibit scars from a previous generation of removals that were since discarded. For these pieces, the ventral face typically corresponds to the dorsal face of the flake blank, while the blank’s ventral face has been reworked through invasive retouch (as per Barandiarán Maestu, 1974). This can be observed in unfinished gunflints, where the old dorsal face – now the gunflint’s ventral face – displays centripetal removals (Figure 10). However, invasive retouch may also have been applied directly to elongated flakes, as suggested by some examples. The lithic wastes resulting from the retouch process consist of short shaping flakes with low thickness, flat butts, and dorsal surfaces displaying unifacial removals. These small flakes reveal an invasive retouching technique applied either unifacially or bifacially (Barandiarán Maestu, 1974). The retouching process appears to have been performed using direct percussion, as no evidence of counter-blows has been identified. The average dimension of these pieces ranges 2.9 cm in length (σ = 1.6), 2.6 cm in width (σ = 1.3), with an average thickness of 0.8 cm (σ = 0.5). The orientation of these gunflints relative to the active part is problematic, as the edges are equally worked (Barandiarán Maestu, 1974). The frequency of this type of gunflint is considerably smaller than the blade-based first type, although some workstations show evidence for combined production of both models (e.g., WS003.9; Table 3). The shaping technique could, in theory, correspond to strike-a-light flints production, as observed in certain contexts within the Mediterranean basin (Evans, 1887). However, based on the morphology and average dimensions of these pieces – especially when compared to blade-based gunflints (Figure 9) – and considering the lack of comparative morphometric data on strike-a-light flints, we argue that these pieces represent a distinct method of gunflint manufacture involving invasive retouch. This retouch technique is already attested in the Mediterranean basin, notably in Spain (Barandiarán Maestu, 1974). While the frequency of certain gunflint types may vary depending on the area studied, as well as selective discard processes during production, the primary manufacturing focus appears to have been on rectangular, blade-based gunflints.

Gunflints with invasive retouch. (1) Preform showing unifacial shaping on a flake blank. (2 and 3) Shaping flakes discarded during the retouch process (drawing P.-A. B.; photo B. M.-R.).

The coexistence of both blade-based and flake-based gunflints at the site raises questions about the specific tools used for knapping and retouching. During the initial stages of production, the same tools may have been employed for both blade and flake debitage. A heavier splitting hammer was likely used for “quartering” the blocks, while a double-pointed hammer – commonly used in France (Barnes, 1937; Emy, 1978; Weiner, 2017) – may have been adopted by craftsmen specifically for blade production. For retouching, a different metallic tool – such as a disc hammer or a hammer made from a file – was used in Western Europe to strike the piece against a steel anvil, typically set in a wooden support (Barnes, 1937). In contrast, techniques documented in the Mediterranean basin at the end of the nineteenth century involved the use of the same angular, square-pointed hammer for both flaking and shaping via direct percussion (Evans, 1887).

In this context, we might expect different tools to have been used for producing blade-based rectangular gunflints compared to those shaped using invasive retouch. The retouching technique for blade-based gunflints involves a hammer-and-steel setup, while invasive retouch likely relied on direct percussion, possibly using a small hammer. These apparent differences in tool use suggest the presence of two distinct technical traditions at the site.

4 Discussion

The manufacturing process of the Wadi Sannur gunflints is essentially similar to that observed in Western European contexts (Barandiarán Maestu, 1974; Barnes, 1937; Clarke, 1935; Emy, 1978; Schleicher, 1927), demonstrating an industrial level of production. This industrial nature is evident in the spatial organization of the manufacturing area, which appears to have been structured for military supply under the centralized authority of Mehemed Ali’s state. Segmented organization was likely planned for seasonal expeditions, taking into account the logistical challenges of a desert environment. Archaeological evidence, including dwelling spaces and pottery wastes (see Figures A3 and A4), suggests a setup specifically designed to meet provisioning needs: for instance, water supply may have been locally sourced from a natural cistern in the Wadi Umm Nikhaybar (Briois et al., 2024) and transported to the sites. We can imagine that such activities were facilitated by animal traction, particularly for transporting nodules and blanks between sites. Historical record mentioning the existence of a control center at the Ramessid Fort (Schweinfurth, 1885) suggests that these productions were closely monitored due to their importance. This type of organization is part of the political strategies developed by Mehemed Ali’s centralized power and is well-recognized within the organization of the Egyptian army (Fahmy, 1997). In the absence of archival sources, questions regarding the identity of the miners and the organization of labor remain unanswered. Some sources mention miner corps within Mehemed Ali’s army (Planat, 1830, p. 351), which may have been composed of deserters (Fahmy, 1997). Meanwhile, while the extraction process required significant energy and labor capacity, the expertise necessary for manufacturing suggests the presence of craftsmen who were either trained or already specialized in this field.

In addition to the issues related to the origins of expertise, the spatial analysis of the quarries provides insights into the labor organization: lithic concentrations, which indicate remnants of workstations, represent short production stages within the lifespan of the quarry. The fact that all the lithic concentrations at the WS004 site are entirely devoted to the reduction process of “flaking” suggests that blanks were likely transported to the other site or directly imported for military supply (Figure 11). In this case, each concentration represents the same step of the entire manufacturing process during an undetermined lifespan. In WS003, the presence of different workstations showing segmentation and the coexistence of two different technical models support the proposition of labor organization and short duration.

Summary of the general organization of the production in the factory including different chaîne opératoire steps at the two sites.

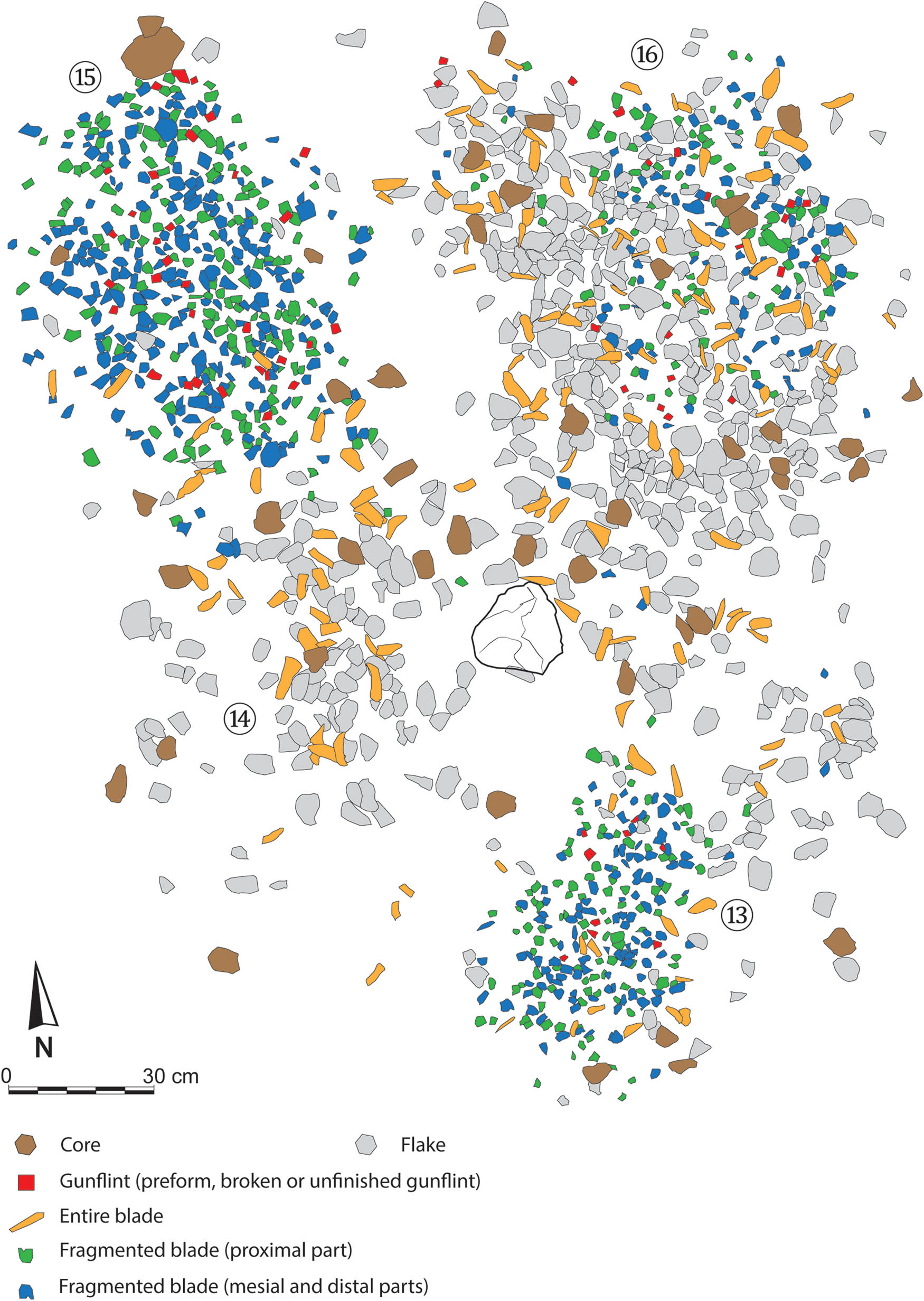

Among the 32 concentrations at the WS003 site, some are isolated, and others are clustered. All of these concentrations consist of lithic remains related to one or more stages of the manufacturing process that have been previously described. Of the 19 isolated concentrations, 16 document the entire knapping process, from debitage to the retouch stage. If each concentration corresponds to a single individual, it suggests that the craftsman was independently carrying out every stage of the manufacturing process. For the three isolated concentrations lacking lithic remains associated with the final stage of manufacture, we interpret this as evidence that the knapper relocated within the manufacturing area. The clustered concentrations indicate a spatial organization, with two to four accumulations, each averaging 3 m in diameter and overlapping one another (Figure 12). The assemblages that form part of the clustered concentrations consist of lithic remains linked to the debitage and/or retouch steps. Considering the model of the WS003.13-16 workstation, we can argue that some craftsmen were working together at the same station. Alternatively, if we consider how waste is discarded and dispersed during the knapping process, and the physical positioning of the knapper, it is possible that a single knapper was successively producing several accumulations. Some large limestone blocks observed within the workshop area may indicate a temporary seat for the craftsman (Figure 12). Additionally, based on the number of fragmented proximal blade parts found in the WS003.15 concentration (Figure 12 and Figure A6), 567 blades have been segmented and retouched in this concentration. The average production in the European factories at the end of the nineteenth century ranged approximately from 500 to 3,000 gunflints per day when the craftsman was exclusively focused on the retouch process (Emy 1978, p. 128, 155; Skertchly, 1879). When contemporary craftspeople execute the entire manufacturing process, the output is approximately 200 pieces per day (Dutrieux J.-J., personal communication). This suggests that the workstation was used for a short duration, at most one or two days, with craftsmen moving fluidly around the main knapping area. These indicators of knappers' mobility point to a flexible organization, despite the specialization and potential oversight throughout the quarry’s operational lifespan.

Planimetric survey of the main lithic artifacts observed on the surface of the clustered workstations WS003.13-16 (Survey and C.A.O P.-A. B.).

Blade technology within gunflint production has not been recognized previously in Egypt, despite being extensively distributed in Europe and beyond since the eighteenth century (Chelidonio & Woodall, 2017). The presence of such a technological trend in Mehemed Ali’s factories is likely due to skill transfers following the military reforms. This idea is supported by sources reporting the exchange of skills between craftsmen of gunflint production between France and Egypt during the nineteenth century (Emy, 1978, p. 16; Salmon, 1885). Regarding the final products and their morphology, the rectangular gunflint type (Figure 12) aligns with those produced in both English and French factories during the same period (Ballin, 2012; Emy, 1978). While the typology does not allow for a precise attribution of technical transfer, it does permit certain inferences about the methods and techniques involved. Although blade technology was widespread across various factories and countries during this period (Avanzini et al., 2016; Chelidonio et al., 2019; Chelidonio & Woodall, 2017), the segmentation and retouching processes have always been considered through different techniques that varied from one country to another. In the basic model described in the literature for Western European factories dating from the end of the eighteenth to the beginning of the twentieth centuries, blades are fragmented by metallic percussion on steel (Barandiarán Maestu, 1974; Barnes, 1937; Chelidonio & Woodall, 2017; Emy, 1978), but the tool used and the fragmentation process vary according to the identity of the knappers (Austin, 2011; Barnes, 1937). Barnes (1937) proposed a typological and technical differentiation based primarily on his observations in Suffolk (England). In the French model described by Emy (1978), the blade is segmented into two parts by removing the proximal and distal ends. The central fragment is then progressively retouched, allowing the production of one or several gunflints from a single blank. The English technique, as described by Barnes (1937), involves holding the blank at an angle and striking it on the dorsal face to remove the proximal end, thereby creating one side. This process is then repeated on the ventral face to form the opposite side. While the overall sequence is broadly similar for both examples, key differences emerge in the quantity and type of waste produced during the retouching phase. In the French system, the amount of discarded material is considerably higher because of the shaping of the gunflint heel, reflecting a greater degree of retouch investment. In contrast, British gunflints appear to generate minimal retouch waste, as the oblique side fractures resulting from the initial segmentation already define the shape of the final product (Austin, 2011). Typical rectangular British gunflints often retain demi-cone percussion marks – referred to as “knots” by Barnes (1937) – on two sides, evidencing their origin from segmented blades.

In our case, while the gunflints exhibit forms consistent with the British style (Figure 13), the high frequency of short, retouch-derived flakes in the WS003 assemblage – distinct from typical blade waste (proximal, mesial, or distal fragments) – indicates a higher degree of retouch investment. This suggests a deviation from standard British manufacturing practices. The assemblage appears to reflect an adapted form of blade-based manufacture, incorporating traits from both French and British traditions. This supports the hypothesis of the introduction of Western European knapping skills and techniques. The preference for the rectangular morphology may be explained by the high value attributed to these forms compared to the D-shaped French gunflints (Emy, 1978) – possibly due to their longer service life, or because they were easier to produce. Despite the absence of direct archival evidence, the hypothesis of French influence in the transmission of technical knowledge is supported by the historical presence of French mercenaries in Mehmed Ali’s armies.

Gunflints of “Western-European style” from the WS003 site (drawing P.-A. B.).

The second model observed within the chaîne opératoire – on invasive retouched gunflints from flake blanks – indicates the existence of another technical tradition. Flake debitage is the original technique used in the history of gunflint production, particularly evident in “wedge-shaped” gunflints or “gunspalls,” which are considered among the earliest forms of gunflint production (Kenmotsu, 1990; Kent, 1983; Skertchly, 1879; White, 1975; Witthoft, 1966). While the technical process for producing gunspalls – removing flakes from large cores and flakes by frontal detachment (e.g. Chandler, 1917; Weiner, 2017) – resembles the technique observed here, the key difference lies in the invasive retouching process employed at this site (Figure 14). The invasive-retouch technique has been widely documented through gunflint production across different regions, including North America (Kent, 1983; White, 1975; Witthoft, 1966), Europe (Barandiarán Maestu, 1974; Chelidonio, 2013; Evans, 1887), Africa (Phillipson, 1969), and Southeast Asia (Whittaker & Levin, 2019). This technique has often been characterized as easy to reproduce, implying fewer technical skills. Such assumption – applied to Egyptian gunflints (Bardin, 1851; Rock, 1861) – is, however, only one possible explanation. This perspective also obscures the actual complexity of these manufacturing processes, the historical context in which they developed, and their potential suitability to specific types of firearms. This interpretation aligns with the concept of technological convergence, in which similar solutions emerge independently in different regions and time periods. Still, the occurrence of similar retouching techniques does not exclude the possibility of technical transfer or external influence. A well-documented example is the progressive spread of blade-based techniques, thought to have originated from France and subsequently adopted in England (Emy, 1978; Witthoft, 1966), and elsewhere.

Gunflint of “Mediterranean-style” from the WS003 site (drawing P.-A. B.; photo B. M.-R.).

This shaping technique has been identified in various countries across the Mediterranean basin, including Spain, Portugal, and Albania (Barandiarán Maestu, 1974; Chelidonio, 2013; Evans, 1887; Kent, 1983; Picazo Millán et al., 2020; Roncal Los Arcos et al., 1996). In Spain, evidence of such a method involving flake debitage and invasive retouch on unifacial gunflints is related to factories dating from the eighteenth to nineteenth centuries (Picazo Millán et al., 2020; Roncal Los Arcos et al., 1996). This technique, even when replicated or transferred to other countries in the Mediterranean basin, is believed to have originated in the Ottoman Empire (Barandiarán Maestu, 1974). We interpret the presence of this technique in the Wadi Sannur workshop as resulting from a distinct technical tradition potentially influenced by the craftsmen’s backgrounds.

Additionally, Witthoft (1966) suggested a possible correlation between the shape of invasively retouched gunflints and the striking angle of Mediterranean muskets equipped with miquelet locks. Theoretically, the miquelet mechanism was less demanding regarding the regularity of the gunflint edge shape, due to the groove on the lock plate (Emy, 1978, p. 23). In this context, unifacial or bifacial invasively retouched gunflints – even when irregularly shaped – may have been particularly effective with miquelet locks, as they ensured more reliable contact with the battery, thus improving ignition. This correlation between the expedient nature of Egyptian gunflints and Mameluke’s flintlocks was notably observed during the French Military Campaign (Bardin, 1851). However, further confirmation is needed regarding the recurrent association between this gunflint type and the miquelet flintlocks, as their use may not have been exclusive to the Ottoman army like the Mamelukes corps (Guémard, 1925). The same observation can be made considering the use of these gunflints manufactured in Spain and Portugal (Barandiarán Maestu, 1974; Buscaglia et al., 2016). In fact, invasive retouch by unifacial/bifacial motion in general was also widespread in the New World (Kent, 1983; Withe, 1975; Witthoft, 1966), despite the major use of conventional European flintlocks (Kent, 1983). Nevertheless, this fabrication technique in the factory could be an adaptation to specific firearms still in use by Egyptian troops. This is likely the case for armies like the Ottoman armies, as for Mamelukes or Mehemed Ali’s Albanian troops, who traditionally used these types of gunflints, and are observed in the archaeological record (Riemer & Kindermann, 2020). It is therefore possible that the style was linked to a technical tradition already existing in Egypt or introduced from the Ottoman Empire. This proposition should be tested by comparing Ottoman gunflint productions, for the final products and the entire manufacturing process.

While the standardization, quality, and quantity of the dominant products (rectangular gunflints made from blades) were linked to the supply of new muskets for Mehemed Ali’s army, the technical transfers indicate an overlap between two technical traditions. The uneven presence of these productions within the workstation assemblages suggests that craftsmen may have alternated between different types of gunflints, tailoring their work to specific needs or adapting to their knapping habits. This variability in individual behaviors within the workstations reflects differing backgrounds, with craftsmen using different methods and techniques based on their traditional expertise.

The variability may also suggest chronological boundaries in the lifespan of the quarry. Following the gradual replacement of older muskets within the army and considering the functional design, the production of Western European-style blades and gunflints may have been exclusively adopted at a certain point. This would have led the factory to become highly specialized in blade production and rectangular gunflints, as observed at the two sites. In this scenario, blade technology would have been progressively adopted, with other technical processes remaining visible in only a few workstations.

This implies that the origin of the quarry may date back much further than previously proposed, even though the production itself was not industrial. On the other hand, these peripheral workstations, which show a combination of flake and blade production, are unlikely to have been contemporaneous with the main manufacturing area. They may have resulted from independent production during the decline of the quarry, though such pieces were probably still useful for the civil purposes of the local nomadic populations.

5 Conclusion

The presence of this quarry in Egypt highlights the dynamics of military reform under the political power of Mehemed Ali. In addition, it provides insights into the nature of these industries in this geographic area during the nineteenth century. Questions still arise about how these factories were established and their duration. The input of archival sources could highlight the political initiative and the organization of these activities, as well as the identity of the craftsmen. We can also interpret that the end of quarrying activities may have coincided with the decrease in warfare or the adoption of modern weapons within the Egyptian armies.

Regarding the lithic industry, we observe different patterns based on style and technology, which can be explained in two complementary ways. The first dominant production model involving Western European-like gunflints is managed by political and military control and is devoted to the muskets used by the Egyptian armies. In parallel, the coexistence of various techniques and styles in the quarry likely results from diverse traditions and expertise of the craftsmen, not only functional objectives. Analysis of these sites and their assemblages addresses direct questions relating to the circulation of skills in the field of lithic technology. The adoption of laminar technology in Mehemed Ali’s workshops suggests a chain of transmission based on the transfer of expertise among specialized craftsmen, adapted and reproduced in specific contexts. This archaeological example highlights the importance of studying these phenomena within the lithic industry over a period spanning from a decade to potentially half a century. In addition, the coexistence of traditions in terms of style and technique intersects with various explanations related to functional design on one hand and the replication of traditions on the other. These findings emphasize the complexity of examining lithic industries through the lens of style and the challenges involved in discussing technical identities.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the Minister of Tourism and Antiquities (MoTA), Cairo, Egypt, for permission to conduct our research on Wadi Sannur. We also thank Kevin Chartier and Jean-Jacques Dutrieux from the “Musée de la pierre à fusil” [French gunflint’s museum] from Meusnes (Cher, France), for their professional advice. Our sincere thanks go to Paul Dubrunfaut and Isis Mesfin for their thought-provoking discussions on gunflint use and knapping. We also thank Naglaa Hamdi Boutros and members of the Wadi Sannur team for their assistance throughout the research. We would like to thank Kerryn Warren for her help with the manuscript revision. We also thank the reviewers for their advice and suggestions.

-

Funding information: This work is part of an excavation program funded by the IFAO “Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale,” The “Keops Foundation,” and the Labex “Structuration des Mondes Sociaux” (SMS, ANR-11-LABX-0066) of Toulouse-Jean-Jaurès-University and the EHESS “École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales” research fund. The achievement of this work was made possible by a fellowship awarded by the Fyssen Foundation.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and consented to its submission to the journal, reviewed all the results, corrected and approved the final version of the manuscript. Pierre-Antoine Beauvais (Fyssen Foundation, University of Cape Town): conceptualization, methodology, writing the original draft and illustrations. François Briois (EHESS, UMR 5608 TRACES, Toulouse), director of the Wadi Sannur project: methodology, writing the final draft, and illustrations. Béatrix Midant-Reynes (CNRS, UMR 5608 TRACES, Toulouse), co-director of the Wadi Sannur project): writing the final draft and illustrations.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Appendix

General view of the WS003 site, view from the Wadi Um Nikhaybar showing the Ramessid Fort (photo B. Midant-Reynes).

WS004 site, view of the quarry with the spoil heap from the manufacturing area (photo B. Midant-Reynes).

Burned area, suggesting fire-camps near the quarry at the WS004 site (photo P.-A. Beauvais, 2022).

Discarded modern pottery remains in the vicinity of the quarry, WS004 site (photo P.-A. Beauvais, 2022).

Lithic concentration (WS004.7) excavated at the WS004 site (photo P.-A. Beauvais, 2022).

Lithic concentration (WS003.15) excavated at the WS003 site (photo P.-A. Beauvais, 2021).

References

Al-Sayyid Marsot, A. L. (1984). Egypt in the reign of Muhammad Ali. Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511563478.Suche in Google Scholar

Austin, R. J. (2011). Gunflints from Fort Brooke: A study and some hypotheses regarding gunflint procurement. The Florida Anthropologist, 64(2), 85–105. https://ufdc.ufl.edu/fr/UF00027829/00212/images.Suche in Google Scholar

Avanzini, M., Salvador, I., & Neri, S. (2016). Le pietre focaie storiche del Monte Baldo tra uso del territorio ed economia minore [Gunflint’s history from Monte Baldo, between land use and mining economy]. Archeologia delle Alpi, 2016, 99–105.Suche in Google Scholar

Ballin, T. B. (2012). ‘State of the Art’ of British gunflint research, with special focus on the early gunflint workshop at Dun Eistean, Lewis ». Post-Medieval Archeology, 46(1), 116–142. doi: 10.1179/0079423612Z.0000000006.Suche in Google Scholar

Ballin, T. B. (2014). East European gunflints - A case study: Gunflints from the Modlin Fortress, near Warsaw, Poland. Gunflints – Beyond the British and French Empires, Occasional Newsletter from an informal working group New Series, 4, 3–11.Suche in Google Scholar

Barandiarán Maestu, I. (1974). Un taller de pierdas de fusil en el Ebro Medio. Extraido Original Cuadernos de Etnologia y Etnografia de Navarra, 6(17), 189–228.Suche in Google Scholar

Bardin, Gnrl E.-A. (1851). Dictionnaire de l’armée de terre, ou recherches historiques sur l’art et les usages militaires des anciens et des modernes [Dictionary of the Army, or Historical Research on the Art and Military Practices of the Ancients and Moderns]. J. Corréard.Suche in Google Scholar

Barnes, A. (1937). L’Industrie des pierres à fusil par la méthode anglaise et son rapport avec le coup de burin tardenoisien [The gunflints industry by the English method and its connection with the Tardenoisian burin technique]. Bulletin de la Société préhistorique française, 34(7–8), 328–335. https://www.persee.fr/doc/bspf_0249-7638_1937_num_34_7_4541.10.3406/bspf.1937.4541Suche in Google Scholar

Beauvais, P.-A. (2024). Des ateliers de pierres à fusil de Méhémet Ali au Ouadi Sannour (Galâlâ Nord) [About Mehemed Ali’s gunflint workshops at the Wadi Sannur (Northern Galâlâ)]. Bulletin de l’Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale, 124, 69–93. doi: 10.4000/129mz.Suche in Google Scholar

Bishay, Y. (1966). Studies on the large foraminifera of the Eocene (the Nile Valley between Assiut and Cairo and SW Sinai). (Unpublished doctoral Dissertation). Alexandria University.Suche in Google Scholar

Bowring, S. J. (1840). Report on Egypt and Candia, Parliamentary Papers: Reports from Commissioners. Tria Exploration reprint, 1998.Suche in Google Scholar

Briois, F., & Midant-Reynes, B. (2014). Sur les traces de Georg August Schweinfurth. Les sites d’exploitation du silex d’époque pharaonique dans le massif du Galâlâ nord (désert Oriental) [Following the footsteps of Georg August Schweinfurth: Chert’s mining sites from the Pharaonic period in the Nothern Galâlâ plateau (Eastern Desert)]. Bulletin de l’Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale, 114, 73–98. https://www.ifao.egnet.net/bifao/114/3/.Suche in Google Scholar

Briois, F., Midant-Reynes, B., & Beauvais, P.-A. (2024). Flint miners’camp at the Galala plateau: WS013 in Wadi Nikhaybar. In Y. Tristant, J. Villaeys, & E. M. Ryan (Eds.), Egypt at its Origin 7; Proceedings of the seventh International Conference ‘Origin of the State. Predynastic and Early Dynastic Egypt, Paris 19th – 23rd September 2022 (pp. 33–44). Peeters Publishers. doi: 10.2307/jj.24751900.8.Suche in Google Scholar

Briois, F., Midant-Reynes, B., & Guyot, F. (2021). The flint mines of North Galala (Eastern Desert). In E. C. Köhler, N. Kuch, F. Junge, & A-K. Jeske (Eds.), Egypt at its Origins 6, Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference « Origin of the State. Predynastic and Early Dynastic Egypt », Vienna 10th–15th September 2017 (pp. 65–81). 303. doi: 10.2307/j.ctv2crj2bh.8.Suche in Google Scholar

Buscaglia, S., Alberti, J., & Álvarez, M. (2016). Techno-morphological and Use-wear Analyses of Gunflints from two Spanish Colonial Sites (Patagonia, Argentina). Archaeometry, 58(1), 230–245. doi: 10.1111/arcm.12237.Suche in Google Scholar

Caliste, L., & Carnino, G. (2022). Qu’est-ce que l’industrie? Qualité, territoires et marchés sur la longue durée [What Is Industry? Qualities, Territories and Markets in the longue durée]. Artefact, 17, 219–242. doi: 10.4000/artefact.13273.Suche in Google Scholar

Chandler, R. H. (1917). Some supposed gunflint sites. Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society of East Anglia, 2, 360–365.10.1017/S0958841800023759Suche in Google Scholar

Chelidonio, G. (1987). Le pietre del fuoco: Metodo, problemi e prospettive di unaricerca interdisciplinare [The gunflints: Method, Problems, and Perspectives of an Interdisciplinary Research]. Annali Musei Civico Rovereto, 3, 113–132. https://www.fondazionemcr.it/UploadDocs/671_Annali3_1987_art06_chelidonio.pdf.Suche in Google Scholar

Chelidonio, G. (2013). Recent findings and observations on firestones and gunflints between craftsmanship, expedient strategies and warfare conditions. In F. Lugli, A. A. Stoppiello, & S. Biagetti (Eds.), Ethnoarchaeology: Current research and field methods (pp. 36–41). Oxford: BAR British Archaeological Reports, International Series, 2472.Suche in Google Scholar

Chelidonio, G., Castagna, A., & Piccolo, G. (2019). Due officine litiche da pietrefocaie fra Cà Palùi e Moruri (Verona) [Two gunflint workshops between Cà Palùi and Moruri (Verona)]. Prehistoria Alpina, 49, 119–127. https://www.muse.it/contrib/uploads/2022/12/PA_49-2017_10_Chelidonio.pdf.Suche in Google Scholar

Chelidonio, G., & Woodall, J. N. (2017). Italian firesteel flints and gunflint workshop traces. Archäologische Informationen, 40, 153–160. doi: 10.11588/ai.2017.1.42478.Suche in Google Scholar

Ciarlo, N. C., Charlin, J., Alberti, J., Buscaglia, S., Vivar Lombarte, G., & Geli Mauri, R. (2019). Size and shape analysis of gunflints from the British shipwreck Deltebre I (1813), Catalonia, Spain: A qeometric morphometric comparison of unused and used artefacts. Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences, 11, 6569–6582. doi: 10.1007/s12520-019-00925-1.Suche in Google Scholar

Clarke, R. (1935). The flint-knapping industry at Brandon. Antiquity, 9(1), 38–56. doi: 10.1017/S0003598X00009959.Suche in Google Scholar

De Lotbiniere, S. (1977). The story of the English gunflint: Some theories and queries. Journal of the Arms & Armour Society, 9, 18–53.Suche in Google Scholar

De Lotbiniere, S. (1980). English gunflint making in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. In T. M. Hamilton (Ed.), Colonial frontier guns (pp. 154–159). Fur Press. (Reprinted 1987, Pioneer Press).Suche in Google Scholar

De Lotbiniere, S. (1984). Gunflint recognition. International Journal of Nautical Archaeology and Underwater Exploration, 13(3), 206–209. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/permissions/10.1111/j.1095-9270.1984.tb01191.x?scroll=top.10.1111/j.1095-9270.1984.tb01191.xSuche in Google Scholar

De Mortillet, A. (1908). Les pierres à fusil: leur fabrication en Loir-et-Cher [Gunflints: Their production in Loir-et-Cher]. Revue de l’École d’Anthropologie, 18, 262–266.Suche in Google Scholar

Dolomieu, D. (1797). Mémoire sur l’art de tailler les pierres à fusil (silex pyromaque) [Dissertation on the art of gunflints knapping (“pyromaque flint”)]. Journal des Mines, 6(33), 693–712. https://www.annales.org/archives/annales/1796-1797-2/100-110.pdf.Suche in Google Scholar

Douin, G. (1923). Une Mission militaire française auprès de Mohamed Aly. Correspondance des généraux Belliard et Boyer [A French Military Mission to Mohamed Aly. Correspondence of Generals Belliard and Boyer]. IFAO, XXXII.Suche in Google Scholar

Dunn, J. (1993). Napoleonic veterans and the modernization of the Egyptian army, 1817–1840. In Consortium on Revolutionary Europe, 1750–1850 (pp. 468–75). Proceedings 22.Suche in Google Scholar

Durst, J. J. (2009). Sourcing gunflints to their country of manufacture. Historical Archaeology, 43(2), 18–29. doi: 10.1007/BF03376748.Suche in Google Scholar

Edeine, B. (1963). À propos des pierres à fusil [About gunflints]. Bulletin de la Société préhistorique française, 60(12), 16–18. https://www.persee.fr/doc/bspf_0249-7638_1963_num_60_1_3876.Suche in Google Scholar

Emy, J. (1978). Histoire de la pierre à fusil [History of gunflint]. Imprimerie Alleaume.Suche in Google Scholar

Emy, J., & de Tinguy, B. (1964). Histoire de la pierre à fusil [History of gunflint]. Meusnes: Musée de la pierre à fusil.Suche in Google Scholar

Evans, J. (1872). The ancient stone implements, weapons and ornaments of Great Britain. Longmans.Suche in Google Scholar

Evans, J. A. (1887). On the Flint-knappers’Art in Albania. The Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, 16(1887), 65–68. doi: 10.2307/2841740.Suche in Google Scholar

Fahmy, K. (1997). All the Pasha’s Men: Mehmed Ali, his army and the making of modern Egypt. American University in Cairo Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Fahmy, K. (2009). Mehmed Ali: From Ottoman governor to ruler of Egypt. Oneworld.Suche in Google Scholar

Farhi, D. (1972). Niẓām-I Cedid. Military Reform in Egypt under Meḥmed ‘Alī. Asian and African Studies, 8(1972), 151–83.Suche in Google Scholar

Gouin, E. (1847). L’Égypte au XIXème siècle, Histoire militaire et politique, anecdotique et pittoresque de Méhémet-Ali, Ibrahim-Pacha, Soliman-Pacha [Egypt in the 19th Century, Military and Political History, Anecdotal and Picturesque of Mehemed-Ali, Ibrahim Pasha, Soliman Pasha]. Paul Boizard.Suche in Google Scholar

Gould, R. A. (1981). Brandon revisited: A new look at an old technology. In R. A. Gould & M. Schiffer (Eds.), Modern material culture: The archaeology of Us (pp. 269–282). Academic. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-293580-0.50027-5.Suche in Google Scholar

Grant, J. (1999). Rethinking the Ottoman “Decline”: Military technology diffusion in the Ottoman empire, fifteenth to eighteenth centuries. Journal of World History, 10(1), 179–201. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20078753.10.1353/jwh.2005.0012Suche in Google Scholar

Guémard, G. (1925). De l’armement et de l’équipement des Mameluks [On the Armament and Equipment of the Mamluks]. Bulletin de l'Institut d'Egypte, 8, 1–19.10.3406/bie.1925.1604Suche in Google Scholar

Guémard, G. (1936). Les réformes en Égypte: d’Ali El Kébir à Méhémet-Ali: 1760–1848 [Reforms in Egypt: From Ali El Kebir to Mehemed Ali: 1760–1848]. Imprimerie P. Barbey.Suche in Google Scholar

Hamdam, M. A., & Jeuthe, C. (2022). Where does Egyptian Chert come from? Preliminary macroscopic, microscopic, and geochemical results. In B. Gehad & A. Quiles (Eds.), Proceedings of the First International Conference on the Science of Ancient Egyptian Materials and Technologies (pp. 99–110). Institut français d’Archéologie orientale, Bibliothèque générale 64. https://www.jstor.org/stable/jj.18654619.11.Suche in Google Scholar

Hamilton, T. M. (1964). Recent developments in the use of gunflints for dating and identification. In J. D. Holmquist & A. H. Wheeler (Eds.), Diving into the past: Theories, techniques, and applications of underwater archaeology (pp. 52–57). Minnesota Historical Society and the Council of Underwater Archaeology.Suche in Google Scholar

Hamilton, T. M. (1980). The gunflint in North America. In T. M. Hamilton (Ed.), Colonial frontier guns (pp. 138–147). Fur Press. (Reprinted 1987, Pioneer Press).Suche in Google Scholar

Hamilton, T. M., & Emery, K. O. (1988). Eighteenth-century gunflints from Fort Michilimackinac and other colonial sites. Mackinac Island State Park Commission.Suche in Google Scholar

Hamilton, T. M., & Fry, B. W. (1975). A survey of Louisbourg gunflints. Canadian Historic Sites Occasional Papers in Archaeology and History, 12, 101–128. http://parkscanadahistory.com/series/chs/12/chs12-3e.htm.Suche in Google Scholar

Harrell, J.-A. (2012). Utilitarian stones. In W. Wendrich (Ed.), UCLA encyclopedia of egyptology, archeology and geology of ancient Egyptian stones. http://digital2.library.ucla.edu/viewItem.do?ark=21198/zz002bqsfg.Suche in Google Scholar

Harrell, J.-A. (2024). Archaeology and geology of ancient Egyptian stones. Archeopress Egyptology, 49. doi: 10.32028/9781803275819.Suche in Google Scholar

Horowitz, R. A., & Watt, D. J. (2019). Eighteenth-and nineteenth-century gunflint assemblages: Understanding use, trade, and variability in the Southeastern United States. International Journal of Historical Archaeology, 24, 95–114. doi: 10.1007/s10761-019-00505-y.Suche in Google Scholar

Inizan, M.-L., Reduron-Ballinger, M., Roche, H., & Tixier, J. (1999). Technology and terminology of knapped stone. CREP.Suche in Google Scholar

Jarrige, F., (2021). Qu’est que l’industrie? [What is industry?]. L’Histoire, 91, 6–11.10.3917/lhc.091.0006Suche in Google Scholar

Kenmotsu, N. (1990). Gunflints: A study. Historical Archaeology, 24(2), 92–124. doi: 10.1007/BF03374133.Suche in Google Scholar

Kent, B. C. (1983). More on gunflints. Historical Archaeology, 17(2), 27–40. doi: 10.1007/BF03373463.Suche in Google Scholar

Krause, K. (1992). Arms and the state: Patterns of military production and trade. Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511521744.Suche in Google Scholar

Lemonnier, P. (1986). The study of material culture today: Towards an anthropology of technical systems. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, 5, 147–186.10.1016/0278-4165(86)90012-7Suche in Google Scholar

Lovett, E. (1887). Notice of the gun flint manufactory at Brandon, with reference to the bearing of its processes upon the modes of flint-working practised in prehistoric times. Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, 21, 206–212.10.9750/PSAS.021.206.212Suche in Google Scholar

Luedkte, B. E. (1999). What makes a good gunflint? Archaeology of Eastern North America, 27, 71–79. http://www.jstor.com/stable/40914428.Suche in Google Scholar

Phillipson, D. W. (1969). Gun-flint manufacture in North-Western Zambia. Antiquity, 43(172), 301–304. doi: 10.1017/S0003598X00040746.Suche in Google Scholar

Picazo Millán, J. V., Morgado-Rodríguez, A., Fanlo Loras, J., & Pérez-Lambán, F. (2020). El aprovechamiento histórico del silex para piedras de fusil. El caso del Río Huerva (Zaragoza) [Historical flint exploitation for gunflints. River Huerva case study (Zaragoza)]. Zephyrus, 86, 191–216. doi: 10.14201/zephyrus202086191216.Suche in Google Scholar

Planat, J. (1830). Histoire de la régénération de l'Égypte: lettres écrites du Kaire à M. le Cte Alexandre de Laborde [History of the Regeneration of Egypt: Letters Written from Cairo to Count Alexandre de Laborde]. Imprimerie J. Barbezat.Suche in Google Scholar

Riemer, H., & Kindermann, K. (2020). Flints from the Road: On the Significance of two Enigmatic Stone Tools Found along the Darb el Tawil. Archaeologia Polona, 58, 257–274. doi: 10.23858/APa58.2020.015.Suche in Google Scholar

Rochfort Scott, C. (1837). Rambles in Egypt and Candia, with details on the military power and resources of those countries, and observations on the government, policy, and commercial system of Mohammed Ali. H. Coldburn publisher. https://archive.org/details/ramblesinegypta01scotgoog.Suche in Google Scholar