From a Medieval Town to the Modern Fortress of Rosas (Girona-Spain). Combining Geophysics and Archaeological Excavation to Understand the Evolution of a Strategic Coastal Settlement

-

Marc Bouzas Sabater

, Lluís Palahí Grimal

Abstract

The paper presents the results of the archaeogeophysical study carried out in the medieval villa of Rosas (Girona-Spain). The village was built in a space that had already been occupied in Greek and Roman times. In the sixteenth century, a large fortress was built around the town. Once the village was abandoned in the seventeenth century, the site underwent a major conversion process, with the construction of military buildings and the demolition of most of the medieval constructions. When it came to studying the village, its large size (20,000 m2) made it advisable to combine different methodologies and approaches in order to obtain optimum results. Some of the areas analysed by the geophysical surveys were subsequently tested archaeologically in order to verify their reliability, taking into account the specific conditions of the terrain. The combined use of geophysical prospecting, archaeology, and the study of historical planimetry and documentation has made it possible to reconstruct the town planning of the medieval villa, as well as the transformations it underwent after its abandonment.

1 Introduction

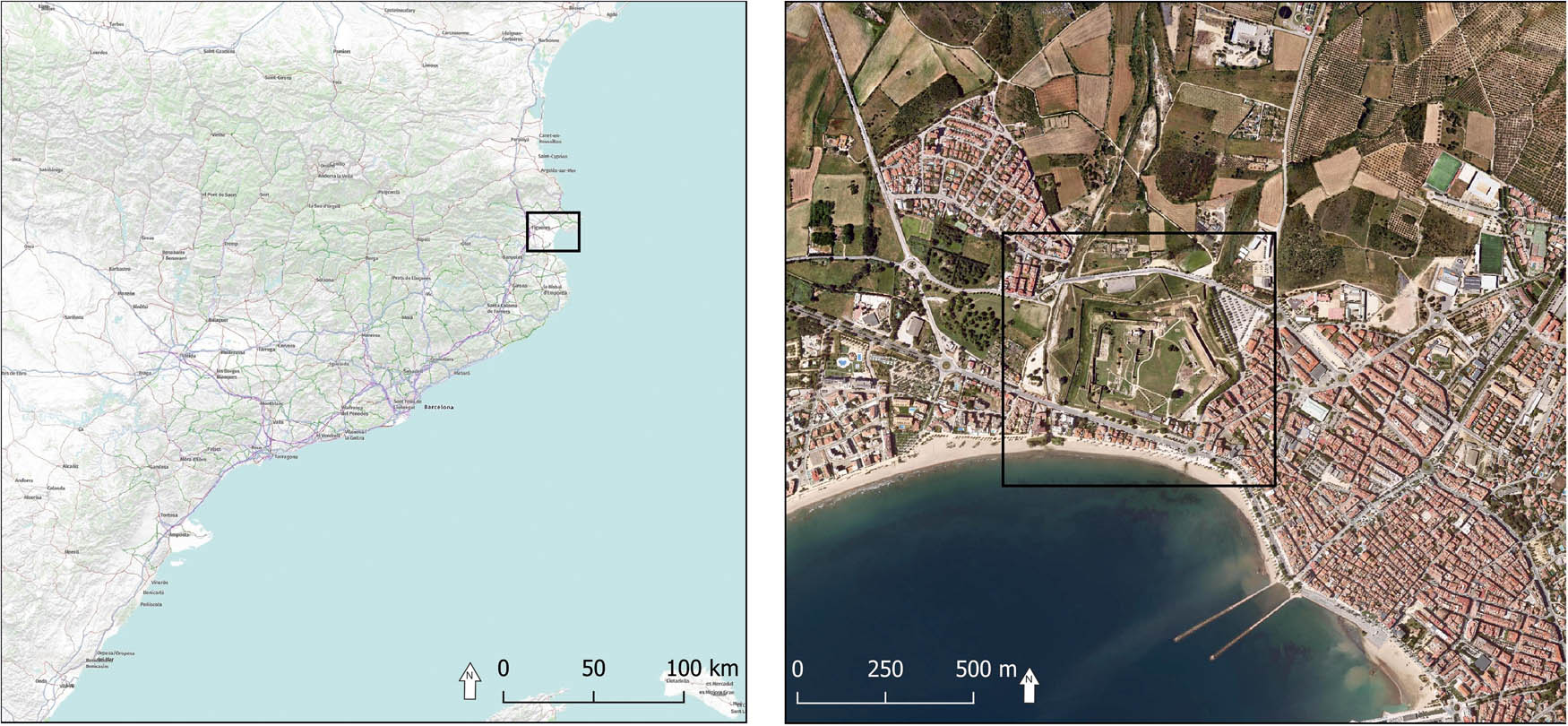

The site of the bastioned fortress known commonly as the Ciutadella (Citadel) in Rosas, a coastal town in the northeast of the Iberian Peninsula (Figure 1), is a real archaeological park. Remains are preserved there that demonstrate the continuous occupation of this site, from the foundation of the Greek colony of Rhode to the contemporary period and passing through occupations in the Roman era, a Late Antiquity hamlet and necropolis, the town of the medieval era and the fortress that gives its name to the place, constructed in the mid-sixteenth century.

Location of the medieval town of Rosas inside the modern fortress.

It is in this space where, since 2018, the Càtedra Roses d'Arqueologia i Patrimoni Arqueològic and Ajuntament de Roses of the University of Girona, in collaboration with Rosas Town Council, has been undertaking a research project focused on the recovery and study of the medieval town. With a surface area of approximately 20,000 m2, this town occupied the western half of the modern fortress. To establish an initial approach with non-destructive methods in the complex archaeological context of Ciutadella, geophysical prospecting was proposed for sectors of the town and its surroundings. The aim of this study was to respond to a diverse set of questions and to serve as a starting point for planning future archaeological and heritage actions.

The prospecting, carried out in two surveys during 2018 and 2019, covered much of the surface of the site occupied by the medieval town, and the exterior part that is closest to the walls to the south and east of the settlement. Designed as an element that complements the archaeological studies, only spaces where archaeological excavations had already been undertaken, or those in which archaeological interventions were planned, were not surveyed. However, the development of the archaeological project has made it possible to subsequently excavate some of the sectors prospected, allowing the results to be verified.

2 A Brief History of the Site: Archaeological Knowledge of the Sector of the Medieval Town

The history of Rosas has always been marked by its coastal position and the fact that it has a bay protected from the winds, which made it a port of refuge for ships coming from or going to the south of France. It is important to note that the presence of a series of small watercourses that constantly bring sediment to the mouths of the rivers has caused, throughout history, a significant shift of the coastline in a southerly direction. This has meant that the present-day hill of Santa Maria, located some two hundred metres from the present-day coastline, in Greek times was a spur leading into the sea (Bouzas et al., 2023).

The occupation of the site under study dates back to the fourth-century BC with the foundation of a Greek colony. Although the urban planning and evolution of the settlement are only partially known, archaeology has made it possible to determine that the original nucleus was located on a small elevation (now called Santa Maria hill), a space flanked by two streams (the Trencada stream to the west and the Rec Fondo to the east). The colony expanded in the third century with a new port district (known as the Hellenistic district) and was finally abandoned at the beginning of the second-century BC as part of the Consul Cato’s campaign in Spanish territory (Puig & Martin, 2006).

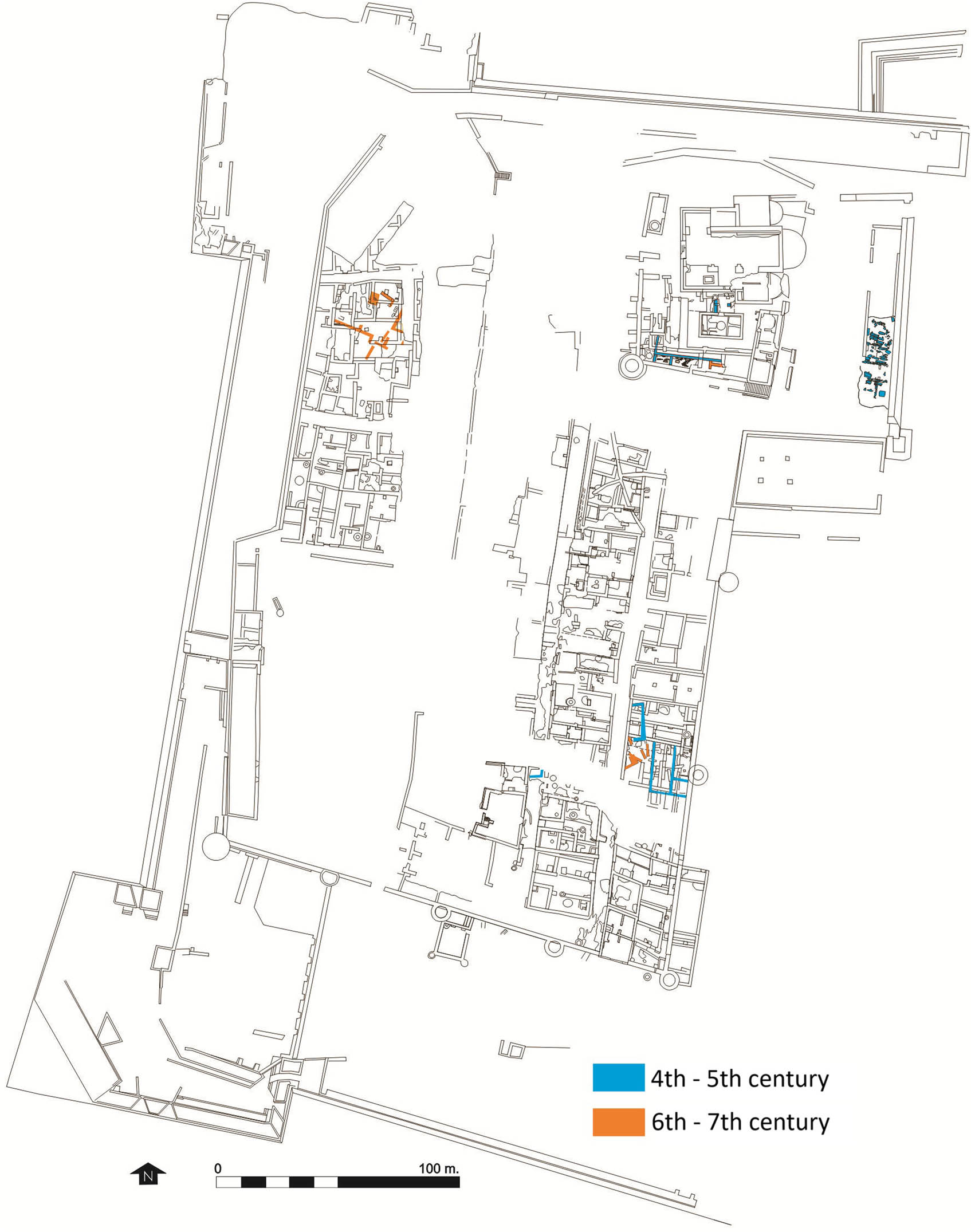

From the second-century AD, the area was occupied again, this time by a Roman vicus that continued into Late Antiquity and at least until the seventh century (Bouzas & Palahí, 2024). The settlement occupied the port area and also extended along the slopes of the hill of Santa Maria. A cella memoria was built on the upper part of the hill in the fourth century, around which a necropolis grew up. The cemetery continued in use beyond the seventh century and ended up extending over the entire site of the current fortress and beyond (Bouzas & Palahí, 2024, pp. 209–210).

Although Roman-period constructions were oriented from north to south, from the sixth century onwards, a change in urban planning can be detected, as the new buildings were built oriented from northwest to southeast. This is a relevant element, since the medieval constructions will recover the north-south orientation of the Roman period and, in principle, it should be an indication when evaluating the results of the surveys.

The settlement seems to have been abandoned again from the seventh century onwards for unknown reasons.

At the beginning of the tenth century, a Benedictine monastery dedicated to Santa Maria was built on the remains of the cella memoria (Palahí et al., 2022, p. 131; Puig, 2016, pp. 352–353). The monastery would be the seed from which the medieval town of Rosas would be built a century later. The creation of the town was part of a wider process of habitat concentration, whether in the surroundings of churches (sagreras) (Martí, 1988, Mallorquí 2022 for the north-eastern Catalan area) or in the surroundings of monasteries, castles, or old rural settlements (Farías, 2009). These small towns usually met three topographical conditions, all of which are present in Rosas: taking advantage of the slopes of a hillside, being located next to a watercourse, and having a fertile alluvial plain (Farías, 2009, p. 213).

The original centre of the town developed throughout the eleventh century on the western slope of the hill. It was initially organised around two streets that crossed at a right angle, known in the documentation as the Carrer de la Creu (cross street; Pujol, 1997, p. 63; Pujol, 2018, p. 80). Traditionally, it has been considered that the town had a wall, although archaeology, as we shall see, has not so far made it possible to locate it (Palahí et al., 2022, pp. 131–135). In fact, very little is known about the original town planning, beyond the existence of the two streets, since the buildings were greatly modified in the modern period (sixteenth–seventeenth centuries).

From the thirteenth century onwards, the town grew considerably to the south and the east, and expanded towards the beach that is situated to the south. Between the end of the thirteenth century and the start of the fourteenth, this neighbourhood was protected with new walls. Outside the walls, along the beach, was an outlying neighbourhood occupied by some houses but, above all, by the fishermen’s shops and storehouses (Pujol, 2018, p. 80). The town always remained between the natural limits marked by the Trencada and Rec Fondo creeks.

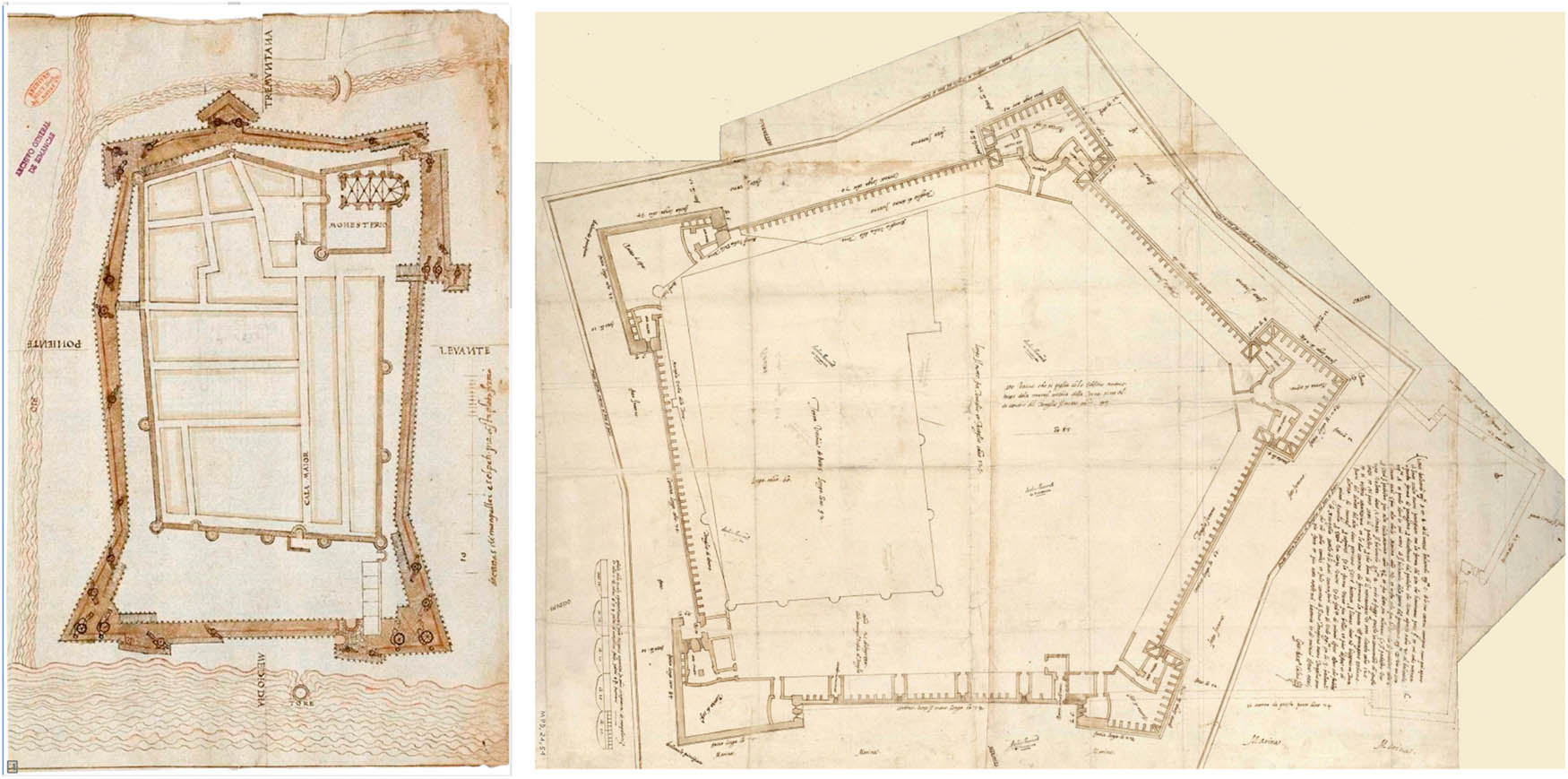

One of the characteristics of the town, both in the extension area and probably in its original centre, is the preliminary, organised planning, which considered the layout of the streets and the interior division of the blocks of houses (Puig, 2020, pp. 43–52). This planning was common since the eleventh century in newly founded towns (Betran Abadía, 2005). The basic structure was configured based on longitudinal streets, distributed in parallel, and where transversal streets were scarce. Plotting had not only an urbanistic but also a fiscal role. The blocks were arranged on the basis of spaces arranged perpendicular to the streets, with a width of between 4.5 and 6 m. (usual dimensions of a wooden beam). Another element was the homogeneity between the depths of the plots, either with elongated houses (between 15 and 25 m.) opening onto two streets or with the creation of larger blocks with a double row of houses opening onto different streets (Betran Abadía, 2005, p. 87). All these theoretical conditions are applicable to Rosas (Figure 2). While the original nucleus was laid out with two perpendicular streets (Carrer de la Creu), the area immediately to the south was organised with three east–west streets (from north to south, Carrer Hospital, Carrer Ganyut, and Carrer de Murtra). In contrast, the eastern sector (immediately south of the monastery) was structured around two long streets (Major and Nou) running north–south and connecting the monastery with the port. This organisation is reflected in the capbreus (land records) of the period (Pujol, 1997) and in the military planimetry at the time of constructing the Citadel, which sometimes reproduces the urban fabric of the settlement in more or less detail.

General view of the medieval village area with indication of the main topographical elements mentioned in the text.

In the mid-sixteenth century, the construction of the bastioned fortress, initially planned to protect the port and the bay (De la Fuente, 1998), changed much of the appearance of the area. Although the works affected the western side of the town, which was left partially under new defensive ramparts, and the port neighbourhood, which had to move eastwards, the town continued to exist, enclosed within new defences that covered an area that was almost double that occupied by the settlement.

Soldiers and civil population lived together for almost a century, until in the context of the “Segadors” War (1640–1652), the fortress was occupied by French troops after a siege (1645). During this time, the town was partially destroyed (Puig, 2020, p. 38). With the French occupation, which continued for fifteen years, the civil population moved outside of the fortress, and a process of rapid destructuring of the town began, with its conversion into an area used only by soldiers. From this time on, certain sectors and buildings of the old town remained in use as military facilities. The rest were abandoned and plundered.

With regard to the archaeological knowledge of all these areas, it should be noted that, beyond some sporadic explorations to try to locate traces of the Greek colony of Rhode, systematic and scientific archaeological excavations of the medieval town began in 1993 and continued, extremely intermittently, until 2011 (Puig, 2020). They were taken up again with the current project in 2018. These studies, which focused on the north-west quadrant of the settlement, identified traces of an earlier occupation from Late Antiquity (sixth to seventh centuries AD). Although the area in which excavations went below the medieval levels was very limited, it was found that the Late Antiquity buildings had a completely different orientation from that of the medieval town. In fact, when the construction of the new town was planned, the land was filled in, which erased any traces of the previous occupation that could have remained visible.

As mentioned above, several elements suggest that this first medieval centre had walls at an early date. No archaeological traces remain of this enclosure. Fortunately, we have an extensive collection of military plans dated between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries, held in various Spanish and French military archives. Most of them are gathered in an atlas (Castells et al., 1994), and much of the planimetry of the Spanish crown can be consulted online.[1] Two plans from the period of construction of the fortress, drawn up by the engineers who were successively responsible for the works, Luís Pizaño (Archivo General de Simancas. MPD, LVIII-36 (De la Fuente 2016) and Gian Battista Calvi (Archivo General de Simancas. MPD XXI-51. Estado leg. 308 (Castells et al., 1994, n. 242)) (Figure 3), show the existence in the north sector of the town of a series of quadrangular towers that are clearly differentiated from those preserved in the southern sector, which belonged to the Late Middle Age wall and are round in shape (Pujol, 1997, p. 54; Puig, 2020, p. 47). The discovery during archaeological excavations of a quadrangular tower in the southeast of the monastery was considered proof of the existence of this first wall and its length. However, recent studies have shown how this tower is a sixteenth-century refurbishment (Palahí et al., 2022, pp. 133–134).

Plans by Luís Pizaño and Gian Battista Calvi.

3 The Questions Proposed and the Existing Problem

Although the historical planimetry and the studies of the capbreus provide data on the urban structure inside the town, they reflect a theoretical scheme. Consequently, the main aim of the prospecting was to verify whether the theoretical urban grid outlined by these studies and even the division into plots deduced from an analysis of the capbreus, with very regular plots or estates, reflects the real configuration of the space.

In addition to this objective, the prospecting was designed to respond to another set of questions that have been proposed in the study of the area occupied by the medieval town.

One important question is the surface area that was occupied by some of the structures that preceded the medieval town (Figure 4). The area of the hill had been inhabited since the Greek period. In addition, on the west and east slopes, elements were identified from the Roman period and, above all, part of a settlement and a necropolis from Late Antiquity. Given that the Late Antiquity buildings seemed to have a completely different orientation from that of the houses in the medieval town, this fact and the relative depth of the structures could provide information on the extent of the settlement.

Plan of the medieval villa with an indication of the remains located belonging to the phases between the fourth and seventh centuries.

In addition, the prospecting was designed to verify the existence of the various buildings associated with military use in the space, mainly from the seventeenth century. Despite the abundant military planimetry conserved from this period (sixteenth to nineteenth centuries), these documents contain some inconsistencies. Furthermore, as the planimetry often addresses construction projects, the buildings or elements that are represented do not always correspond with those that exist. Sometimes, buildings designed by the engineers were not executed, whether due to changes in the initial design or because of funding difficulties (on the various plans, refer to De la Fuente, 1998).

Prospecting the area outside the walled enclosure essentially responds to two questions. First, regarding the southern side, traces of the outlying neighbourhood on the coast were sought. This was a small neighbourhood that was greatly affected by the construction of the walls of the bastioned fortress.

Prospecting on the northeast side was also designed to answer some questions on various elements that are not very clear. One of these is which area was occupied by the Rec Fondo Creek. Another question is whether a moat constructed by the engineer Pizaño existed and was subsequently filled in by order of his successor, Gian Battista Calvi.

Technically, the prospection should address some specific features related to the geological characteristics of the land and the historical vicissitudes.

Geologically, the spaces that are surveyed have two configurations. The first is the hill of Santa Maria, formed of gravel with a clayey matrix that is very compact. The second is the lower zone of the site that is comprised of alluvial sands deposited by various water courses. Over time, this caused a progressive and relatively rapid shift of the coastline to the south (Puig, 2012, p. 85). Thus, in the Greek period, the coastline was situated immediately at the foot of the hill, and in the medieval period, it was situated some metres to the south of the town’s walls.

Historically, the sector that in the medieval period constituted the centre of the town was an intensely occupied space for over 2000 years from the time of the foundation of the Greek colony of Rhode until the abandonment of the modern fortress. This does not always imply major changes in the topography or significant elevations in circulation levels. In certain sectors, the archaeological structures, particularly Roman, medieval, and modern ones, are compacted in a stratigraphic sequence of less than two metres.

A final element to be assessed to interpret the results of geophysical prospecting is the large accumulations of rubble from the demolition of buildings. These are usually at shallow depths and often mask the structures. Many of the structures have very shallow foundations, which barely penetrate below the paving and, due to the considerable plundering that they underwent, only conserve one or two rows of height. This means that walls and rubble are difficult to differentiate using remote sensing systems.

All of these elements have an impact on any prospection that is undertaken in the area, and on the interpretation of the results.

4 Prospecting Methodology and Parameters

To establish a methodology for geophysical exploration in archaeology, several factors should be considered. Clearly, the first of these is the objective of the prospecting, associated with an archaeological question. In this case, the aim is to generate subsoil maps of an extensive area to provide added context to existing excavations and new data for establishing new research vectors for the scientific team that directs the research on the site (Garcia-Garcia et al., 2016).

Therefore, considering the need to obtain archaeological information on a context that previous excavations have already defined as complex, methods should be proposed that are effective at describing construction remains and at providing information at different levels of depth. This rules out magnetic prospecting, which offers only one plane of information, although it can provide complementary information of interest. Consequently, the option of an extensive ground penetrating radar survey was selected as the geophysical method with the greatest potential to answer the questions posed by the research team at the Càtedra Roses d'Arqueologia i Patrimoni Arqueològic.

To attain the objectives of delimiting and describing the construction remains in any archaeological site, three important factors should be considered. These are: the determining factors due to the geological context, the known characteristics of the archaeological context, and the most relevant environmental factors (state of the surfaces to explore, humidity of the ground, soil compaction, etc.) (Sala et al., 2012).

The geological context, which is dominated by the coastal location of much of the site and by the response relationship between sandy sediments (with a high clay content in some areas, such as the hill of Santa Maria) and the building masses made of local stone, creates a situation with pros and cons. On the one hand, the proximity of saline water tables to the surface in a large part of the site clearly affects the depth range of the ground penetrating radar data, given that the soil conductivity tends to attenuate the pulses. Hence, the lower areas with sandier materials should be differentiated from the hill of Santa Maria, with more clayey sediments. On the other hand, the characteristics of the construction materials, particularly schist and granitic rocks, should provide a high contrast to the sediments within the range of the ground penetrating radar.

Consideration of the known archaeological context of the site is also crucial. This includes the construction and conservation characteristics that are described in the excavations, and the superimposition of construction stages or the depth of the levels that are of archaeological interest compared to the surface. In these terms, the Citadel of Rosas is a complex context. The long sequence of occupation, from the Hellenistic period to the time of medieval expansion, and the more aggressive imprint of modern occupations relating to military use, comprise a context in which superposition of structures, demolition of buildings, rubble levels, and the recovery of construction materials from earlier phases (trenches from plundering) have been defined. In fact, the parameters of spatial resolution of the prospecting and the antenna frequency must provide sufficient detail to offer comprehensible data on a potentially complicated archaeological context.

Finally, the factors that we could call environmental, associated with variables such as humidity of the subsoil, the depth of the saline water tables or the condition of the surfaces to explore, comprise a third determining factor that can have a decisive influence on the quality of the data. Undoubtedly, the best of these aspects is the condition of the surfaces, which in this case are mainly covered with low grass. This facilitates good contact of the ground penetrating radar antennae with the soil. In contrast, the salinity due to the lack of elevation in the surveyed zone, particularly in the southwest area, and the proximity to the beach means that the data have a limited depth range, due to the much higher conductivity of the soils in this area (Davis & Annan, 1989).

In accordance with these determining factors, it was decided to carry out the prospecting using an IDS georadar system equipped with five antennae of 600 MHz with simultaneous reading and a resolution of 2.5 × 20 cm (200 readings per m2). In total, the prospecting work covered a surface of 14,030 m2 (8,482 m2 inside the town and 5,548 m2 outside the walled medieval enclosure).

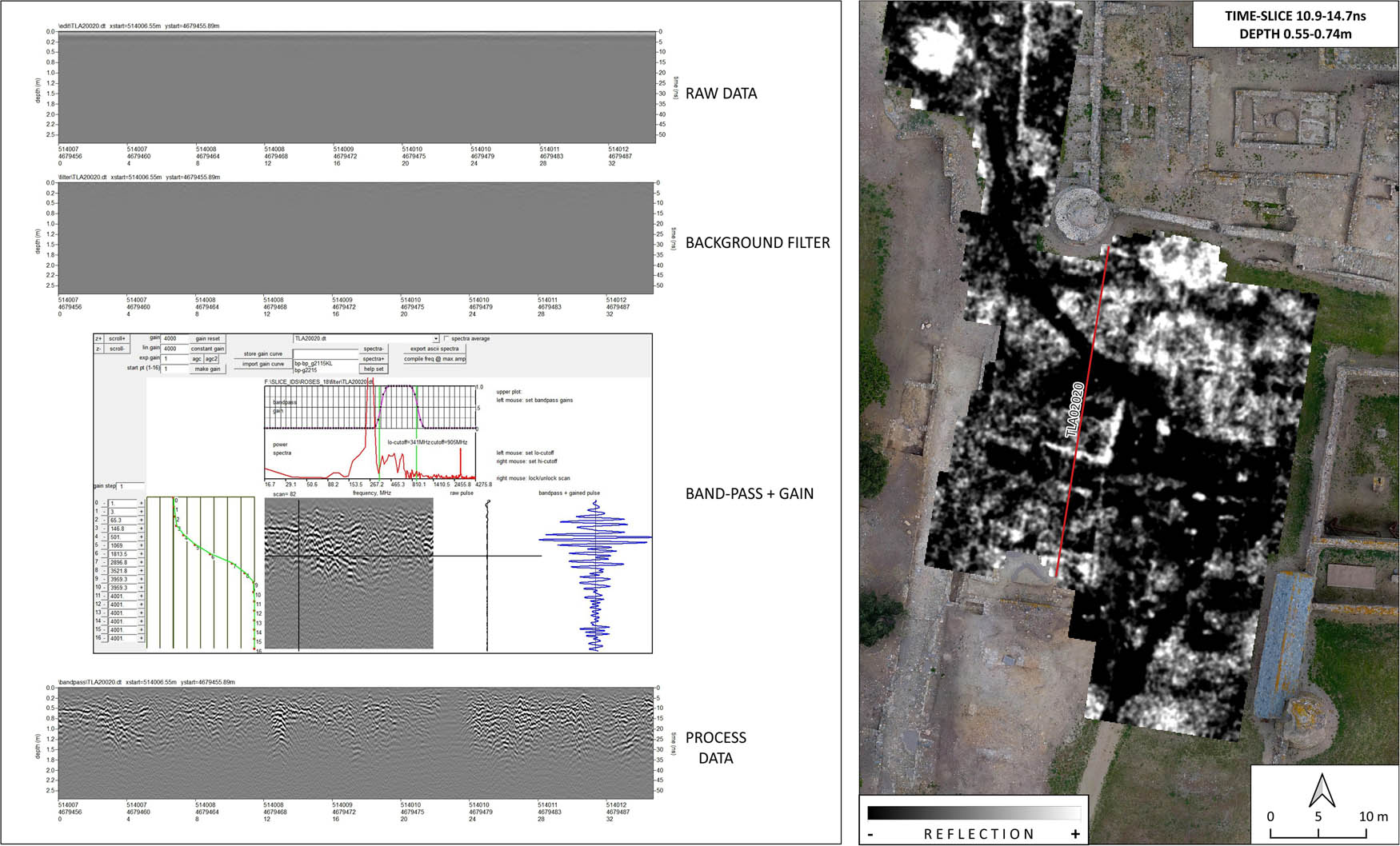

The data were processed by GPR-Slice software. In an initial phase of the process, the focus was pre-processing of the ground penetrating radar sections (Figure 5). After the conversion of the data to the internal format of this software, a background filter was applied to remove constant noise, and then a frequency filter, to centre data in a range between 320 and 900 MHz. The gain curve was established using an automatic routine (Auto Gain Control) that compensates for signal attenuation with depth. The curve was then modified manually to increase the contrast in spaces where the data showed the greatest attenuation, particularly in the sectors around the monastery and the west end of the prospecting, closest to the coastline.

On the left, processing sequence of the geo-radar data from the raw data to the application of band-pass and a gain curve. On the right, a time-slice with indication of the position of the section represented on the left.

In a second phase of data processing, the set of processed sections was integrated into a three-dimensional matrix to generate plan views or time slices (Conyers & Goodman, 1997).

This type of visualisation makes it possible to express the reflectivity values of an area within a range of depths, and therefore to generate sequences of raster images that represent the evolution of the subsoil response as the depth increases. Given the complexity of the data that was obtained, two different visualisations were generated. The first is a sequence of 16 horizontal slices with depth intervals of 0.19 m. The second is a sequence of 24 horizontal slices at 0.12 m intervals, used to view certain structures in more detail. The time slices shown in the figures of the text are based on the sequence of 16 horizontal slices, as they provide a more condensed view of the results.

The sequences of time slices were analysed in the context of a GIS project, to generate simplified interpretation schemes that consider other available data, such as aerial images, photogrammetric surveys of excavations, or relief models. The GIS project was created using the free application Quantum Gis 3.2. The base mapping included public data provided by the data infrastructure of the Institute of Catalonia and the Geological Institute of Catalonia (ICGC), and various photogrammetric flights carried out over the most recent excavations.

All these data were used to create two final planimetries. The first is a vector map of reflective anomalies to express the evolution of elements schematically, with their depth indicated using a scale of colour intensity (Schmidt & Tsetskhladze, 2013). This representation was created by setting a transparency threshold for each of the slices in the sequence, so that only the most reflective bodies are represented. These visualisations have been vectorised and integrated into one image, which represents the most reflective elements in each time slice, according to a colour chart that illustrates the calculated depth.

Finally, a simplified interpretation scheme was generated. This consists of the expression in vector format of the elements interpreted in the previous visualisations, categorised according to their designation as surface elements, built structures, levels of rubble, and unidentified elements.

5 General Characteristics of the Results

The set of data obtained in the two prospecting surveys carried out in 2018 and 2019 were of good quality generally. The regularity of the surfaces in much of the prospecting area made it easier to obtain data with a regular response, except in spaces where the soil was more compacted (circulation areas with compacted sands) or more localised areas with irregular surfaces (north).

As expected, the penetration of the data into the subsoil was more limited in the area of the hill of Santa Maria, where previous excavations had already shown more clayey soils. This limitation was also found in the southwest. However, in the southwest area, which is close to the current coastline, the result was attributed to the proximity of saline water tables (in this area, the land elevation is around 1.8 m asl).

The sequences of time slices generated from the data show a clear contrast between homogeneous deposits of sediments and construction elements or areas filled in with heterogeneous material (rubble, levels of building debris). Nevertheless, some parts of the western sector show data attenuation, possibly due to areas with more clayey sediments.

The analysis of data and their interpretation has been condensed into an interpretation scheme that has enabled comparisons with the results of subsequent excavations and the delimitation of some of the structures detected with the historical mapping.

5.1 The Results of Prospecting and Archaeological and Documentary Verification

To verify the prospecting results (Figure 6), two complementary systems were used. First, from 2020, several archaeological surveys of considerable scope were undertaken that affected some of the spaces examined in the geophysical prospecting. These studies enabled a direct comparison to be made between the prospecting and the archaeological results. Second, an extensive collection of historical plans was used (particularly from the seventeenth to nineteenth centuries), which enabled a more in-depth interpretation of some of the elements that were identified and verification of the reliability of the data obtained.

General view of the area of the medieval town with indication of the surveyed sectors.

One of the main characteristics of the prospecting results is the abundant large anomalies, often with irregular profiles. These mainly correspond to large pockets of rubble. Frequently, these anomalies mask a series of walls and structures that are not always easy to differentiate.

Other very abundant anomalies correspond to signals of between 1 and 1.5 m of diameter that are located at various points of the explored area. Considering the morphology and characteristics of these irregularities, they are considered to correspond to craters resulting from the impact of artillery projectiles during the various sieges suffered by the modern fortress.

The excavations undertaken in 2020 served to verify some of the prospecting results and to refine the interpretation of them in sectors that have not been affected by excavations. This was achieved by extrapolation of the comparison between the georadar detection and the archaeological verification.

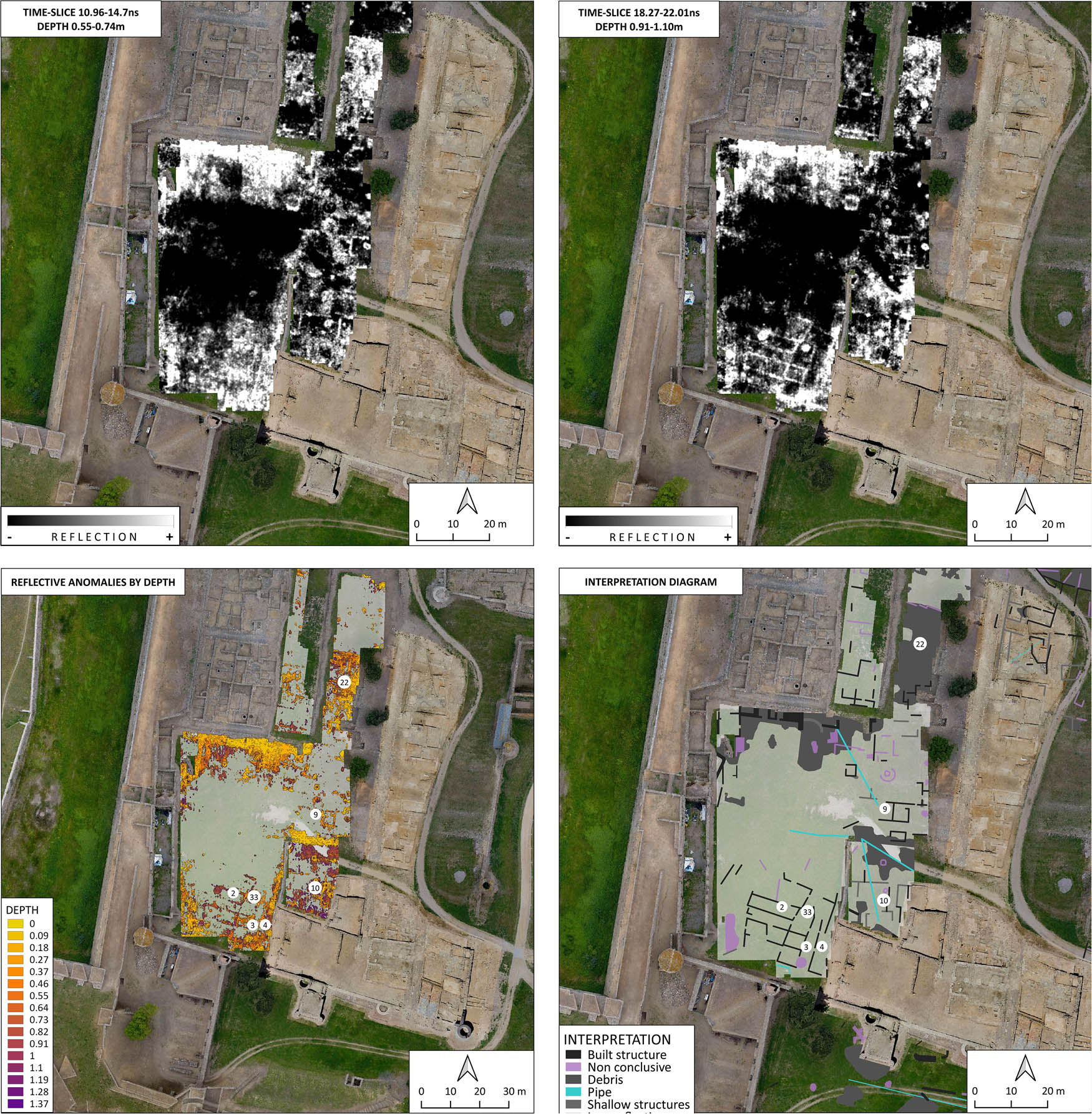

South-east sector (Figure 7): this space outside of the walls covers a surface area of 3,482 m2. On the east side, right next to the wall and at a shallow depth (0.15 m), are some strong levels of rubble. From half a metre of depth, quite strong anomalies could be detected that may correspond to walls. These signals had two discontinuities: one corresponding to the current service road that crosses the zone and a second one several metres to the north.

South-east. Time-slices at different depths. Image below: diagram of anomalies by depth and interpretation scheme.

At the beginning of 2020, excavations began outside the southeast section of the medieval wall (Aguelo, Pujol, 2020). In these studies, a building with a long floor plan was revealed, oriented from north to south and leaning against the eastern face of the wall. Part of this building had already been identified in excavations undertaken in this sector in 1993, when a series of walls were revealed that are orientated from east to west and correspond to the interior partitions of the building (Puig 1994, pp. 75–97). The novelty of the excavation was the identification of the outer perimeter of the building and its eastern façade. Its location coincides fully with the data obtained by the prospecting, in which anomaly 64 corresponds with the eastern façade of the same building.

Notably, the prospecting data do not enable clear identification of any of the wall faces, mainly due to the amount of rubble located around the walls and coming from their own demolition. Prospecting also identified similar structures in the north of the excavated area. These anomalies correspond to the north end of the building that was identified (63) and to another building of similar characteristics situated a few metres to the north (61). The buildings were probably used as storehouses and appear on much of the historical planimetry of the sector from the mid-eighteenth century, for example, on the plan of engineer Miguel Marin from 1741 (Archivo General de Simancas. MPD IX-46, GM Leg. 3313) (Castells et al., 1994, n. 272).

On the same historical planimetry, we can find other elements identified in the prospecting. For example, a series of irregularities can be found in the southeast corner of the town (72, 80, and 82). These can be separated into two groups. The most superficial group is comprised of a rectangular shape of 14 m × 5 m, apparently delimited by very wide walls. Under the main signal, at a greater depth, a possible wall is identified that leans against the corner tower of the town. Regarding the more superficial anomalies, these could correspond to levels of rubble associated with a military building from the modern period, which was constructed to the southeast of the walls and is reflected in the planimetry of the time. This building appears on the plans of 1693, such as that of Jean Baptiste Joblot (Ministére de la Défense, SHAT, Archives du Genie, art. 14, Chateau de Vincennes) (Castells et al., 1994, n. 259). In contrast, the deeper signal could be related to a north-south wall that has a gateway and a series of small buildings that formed an initial point of access to the zone of the outlying neighbourhood. This is represented in the aforementioned plan of the engineer Luis Pizaño of 1543.

Another element located in this area (74) can be related to the structures that are present in Pizaño’s plan. This is a pro-wall structure, situated to the south of the walls, in front of what was one of the main gateways to the town. It is a defensive element with the function of protecting the gateway.

A final, clearly identified element is anomaly 77, which corresponds to a drain that starts at the south end of Carrer Nou street, crosses the wall (where it is still visible today), and runs to the south-west.

Anomalies 77, 78, and 79 have a circular shape and diameters between 1.5 and 1.8 m. They serve as an example of the large number of bomb craters that are located around the fortress site.

West sector (Figure 8): in this space, of 4,643 m2, prospecting revealed two types of anomalies that have very different characteristics.

West. Time-slices at different depths. Image below: diagram of anomalies by depth and interpretation scheme.

The first element that stands out from the results for this sector is that in the entire central zone of the prospecting, no positive or negative traces of structures were identified. This is surprising, especially considering that we are in the centre of the medieval town – a densely urbanised space. Furthermore, the historical planimetry from the end of the seventeenth century and the start of the eighteenth century refers to the existence of a series of buildings here. However, these had a short lifespan, as in the mid-eighteenth century all this zone appears as an open area; a kind of square without any buildings. Thus, the 1693 plans, such as that of Joblot (Ministére de la Défense, SHAT, Archives du Genie, art. 14, Chateau de Vincennes) (Castells et al., 1994, n. 259), outline a pair of large buildings immediately to the south of the governor’s gardens. In contrast, in Miguel Marin’s plan of 1741, the area appears to be free of buildings (Archivo General de Simancas, MPD IX-46, GM Leg. 3313) (Castells et al., 1994, n. 272). There may be two or even three answers to this problem. The first could be related to the specific characteristics of the subsoil that make readings difficult. However, this would be unusual, considering that the immediately adjacent areas give positive readings. The other reasons are associated with the topography and history of the place. In relation to the modern buildings, two situations are possible. First, some of the buildings that are indicated on the plans may never have been constructed. Many of the plans correspond to designs for building projects to be executed in the Citadel. However, in other sectors, it has been verified archeologically and with documents that many of the planned works were never carried out. Second, some of the buildings may have been constructed and subsequently demolished and plundered to take advantage of the material for other buildings in the fortress. In fact, total, systematic plundering of many of the buildings was common. This practice began in the mid-seventeenth century when the town was abandoned and all the houses that were not reused for military purposes were despoiled rapidly and systematically.

The last reason is related to the rest of the medieval structures. A small excavation in 2016 of a building located immediately to the west of the surveyed area (Palahí & Burch, 2018) revealed traces of the medieval town. In this area, it was found that the paving level of the houses was almost a metre and a half below the current level of circulation and that the perimeter walls of these buildings had been plundered to practically the same level as the paving. This depth, combined with the salinity of the ground and fluctuations in the water table, could explain the problems with the depth range of the ground penetrating radar data in this area.

The other interesting aspect of the prospecting in this sector is the identification of a series of structures on the south side of the town (2, 3, 4, and 33), which are very coherent and enable the definition of quite a clear medieval urban fabric (which undoubtedly is mixed with some walls from subsequent renovations and building, corresponding to the military complex).

The orientation of buildings in this sector differs slightly from that of buildings in the northern part of the town. The excavation of the southeast area revealed how the east-west walls of the buildings in the southern area are in a slightly oblique position in relation to the north-south orientation of the main road axes. In fact, the same situation is true of the southern wall, which follows the same orientation. This skewing is corrected further to the north. Another issue is that the prospecting identified an organisation of plots with buildings oriented from east to west. In contrast, in the northwest sector, the area is oriented from north to south. This rotation is determined by the layout of the streets. Thus, the streets in the northern area are arranged from east to west, and this layout marks the orientation of the various buildings, which are perpendicular to the road axes. In contrast, in the eastern area, the two main streets (Carrer Major and Carrer Nou) run from north to south and the houses are arranged from east to west. In the southwest area, we can find a combination of streets from east to west and from north to south. The buildings’ orientation is established depending on the street onto which their main façade opens.

These changes in orientation were maintained even in the modern era. Thus, in what is known as the governor’s house, a building to the west of Carrer Major that served at the end of the seventeenth century as the residence of the stronghold’s commander, the east façade follows the orientation of Carrer Major. However, the east-west partition walls are arranged in a similar orientation to that of the south wall, which generates a general skew in the structure of the building. In contrast to what could be considered, the south wall does not influence the orientation of the buildings in its surroundings. The capbreu of 1304 documents a series of houses in this sector, but the south wall does not seem to have been constructed at this time (Pujol, 1997, p. 78).

The elements identified to the north of the governor’s house follow the orientation of Carrer Major. These structures (9, 10) clearly reflect the medieval organisation, given that between them there is clearly part of a cross street (to the south of 9). Question verified archeologically in the excavations carried out to the east of the sector and through documentation (in which the street is given various names over time, such as the Carrer d’en Murtra, Carrer de Cura or Carrer de Pere Coll) (Pujol 1997). A little further west, above all in the area of a north–south alley that was also identified in the prospecting (3), the change in orientation of the buildings can be seen.

In contrast, in the northern direction, the general orientation of the buildings recovers that marked by the north–south streets. This can be verified that in the northwest quadrant of the town, which was the subject of archaeological work between the years 1993 and 1996.

The northern half of this area is terraced land that ascends towards the east. Therefore, the east section is situated two metres above the area excavated archaeologically. In this higher area, considerable levels of rubble have been found (22), but hardly any structures. To understand this situation, the successive changes in the modern era should be considered. During the siege of 1645, the explosion of an arsenal destroyed much of the northwest neighbourhood of the town. During the French occupation of the Citadel (1645–1660), the town was abandoned, and a rapid transformation of the space began that involved the destruction or plundering of many of the civil buildings. In the area destroyed by the explosion of the arsenal, the action was different. The ruins were covered and filled in, which elevated considerably the level of circulation, and some large gardens were created. In addition, the block of houses situated to the east of the new gardens and the west of the Carrer Major were remodelled significantly. These new buildings were at a higher level than the houses from the medieval period. At some point in the contemporary period, they were cut back, so that the current level of circulation is a metre and a half below that of the modern era. Anomaly 22 is located in this space, with a large amount of rubble.

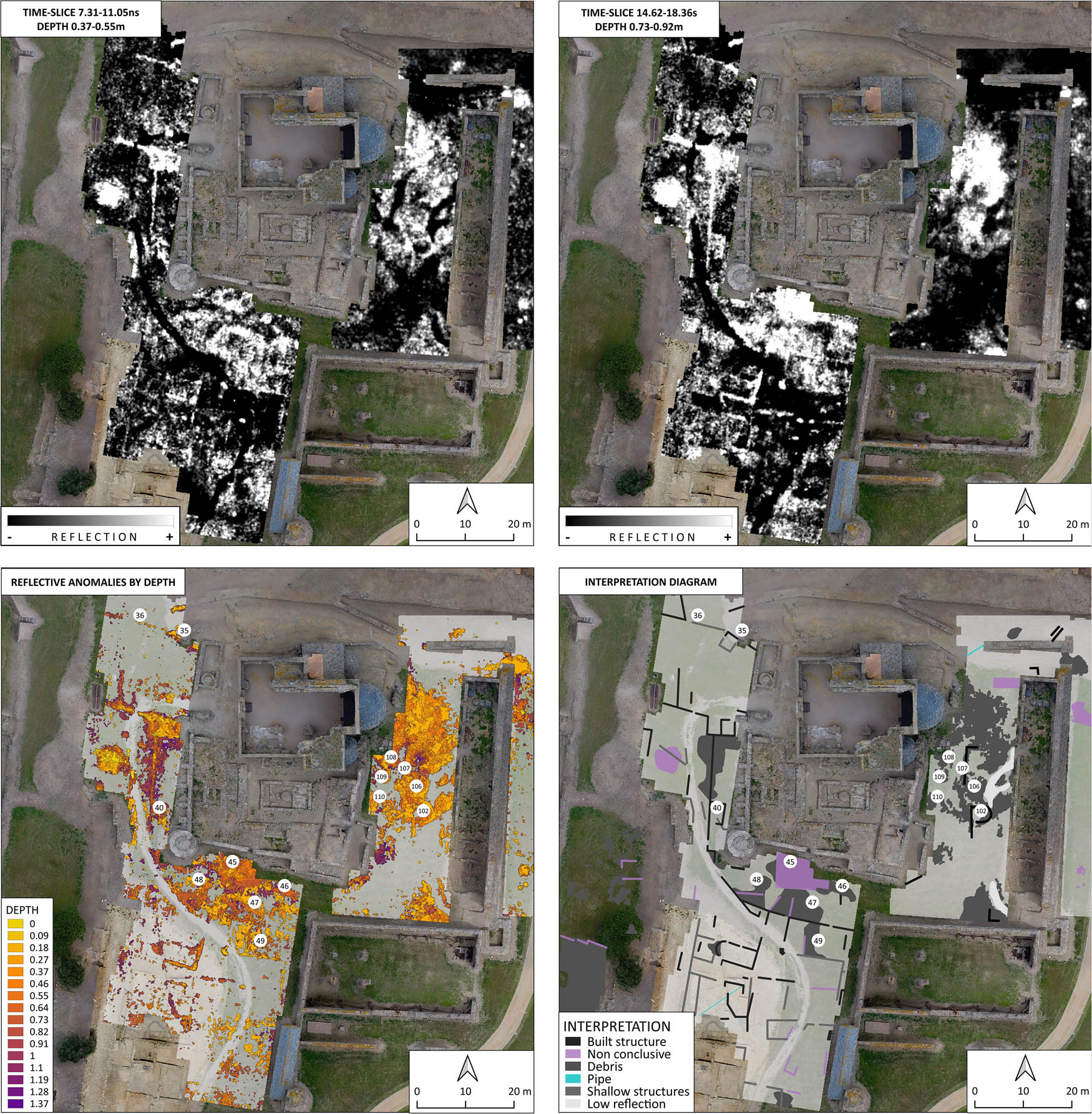

North-east sector (Figure 9): this space is situated to the south and west of the monastery of Santa Maria and has a surface area of 2,287 m2. It is the sector in which the prospecting results could be verified most clearly, as in 2020 an archaeological excavation was carried out here that covered part of the section situated south of the monastery.

Nort-east. Time-slices at different depths. Image below: diagram of anomalies by depth and interpretation scheme.

The archaeological excavation carried out in this sector affected a surface area of around 500 m2 and revealed part of two streets oriented from north to south (Carrer Major and Carrer Nou), and the block of houses situated between them.

The first aspect that should be noted is the existence of two trenches from the archaeological survey carried out in 1945. These cross the entire excavated area in the form of an X. The trench was already detected in the geophysical prospection but the disparity in the consistency of its infill (areas filled in with stones are combined with others in which only earth was used) makes it hard to interpret. In addition, the trenches cut across many structures in the area, which hamper the interpretation due to an apparent lack of coherence of the whole.

Nevertheless, in general, most of the structures that were identified during the prospecting correspond perfectly with the various walls identified during the archaeological studies. They outline a dozen environments that define a series of buildings oriented from east to west.

Regarding Carrer Major, the archaeological excavations identified two parallel walls, which clearly delimit the east side. These two walls have some very different characteristics. The wall situated further to the east is comprised of stones connected with earth, while the second wall further to the west is constructed of stone and abundant mortar. The prospecting identified more clearly the wall to the east (which also appears at a greater height), while the other wall, which is apparently more solid due to its construction with mortar, appears intermittently.

The prospecting identified the continuity of the two streets beyond the excavated area. Carrer Nou is seen to end a few metres before the south wall of the monastery, although it is not entirely clear if the limit marked by the prospecting in this area really corresponds to a wall or to the start of a moat, which is reflected in some historical planimetry and in the documentary sources and corresponds to anomalies 45 to 48.

Carrer Major is prolonged beyond the southwest corner of the monastery. In this area, all the historical planimetry outlines a large square around which a series of buildings would have been distributed. One of these would be the building leaning against the west wall of the monastery, which is clearly defined in the prospecting (40).

If we analyse the prospecting area beyond where it has been verified archaeologically, notable results can be observed to the west of the monastery. At the north end of this space, a structure is observed (35, 36) that, due to its location, can be identified as the north wall of the town. In fact, the planimetry of Luís Pizaño’s design shows the same outline for the wall. Even the existing discontinuity corresponds with the theoretical location of the north gateway to the town.

In this area, the historical planimetry often indicates the location of a small cemetery associated with the monastery that occupied the space between the monastery grounds and the north wall of the town. The existence of this cemetery was verified during the excavations in the 1990s when a series of human remains were identified in this area, which were not excavated at that time to maintain their state of conservation. The distortions in the most superficial sections of the prospection could be related to this cemetery, which was laid out in a very superficial way according to the aforementioned archaeological reports.

In the zone immediately to the south of the south wall of the monastery, some strong anomalies have been identified that probably correspond to levels of rubble (46, 47, and 48) that filled in the moat that both documentary sources and some planimetries situate in this sector. The large anomaly (45) could correspond to the rocky outcrop of the hill itself.

On the east side, some elements are identified that follow the orientation and configuration of the medieval urban planning. However, the building outlined at the northeast end (49) is probably from the eighteenth century.

Sector to the east of the monastery (Figure 9): with a surface area of 1,552 m2 and situated between the east façade of the monastery and the east wall of the town, this is an unusual space. Neither the capbreus documentation nor the historical planimetry indicates any kind of urbanisation of this area, which is shown as a space free of buildings. Nevertheless, the archaeological excavations undertaken in the mid-twentieth century within a storehouse dated to the eighteenth century and constructed against the east wall of the town revealed part of a considerable necropolis from Late Antiquity. This extended along the eastern slope of the hill and was also identified under the cloisters of the monastery.

The original topography of the sector showed an incline from west to east. The prospecting results for this sector differ greatly from those of the rest of the area inside the town. First, the lack of a medieval urban fabric in this area is confirmed. In fact, most of the large anomalies identified (108, 109, 110, and 135) probably corresponded to building debris due to the partial collapse of the monastery. In this respect, it is interesting to observe the map of anomalies by depth of the entire hill of Santa María. Unfortunately, clear construction elements on the east side cannot be distinguished individually. Only in the central zone are anomalies (102, 106, and 107) detected that could correspond to identifiable construction structures. Their definition (in which some semi-circular shapes can be glimpsed) is not clear enough to determine whether they are tombs or a building. Second, chronological conclusions cannot be drawn, given that in this area the remains could date from any period from the foundation of the Greek colony to the construction of the Citadel’s own fortress.

The results obtained outside the walls of the town in this area are a lot more disappointing, as they do not provide any kind of information that helps to clarify the existence of a moat or a valley caused by the movement of water in the creek.

Notably, in this prospecting, it was decided to also explore a sector of the esplanade situated to the east of the medieval town. For this purpose, an area was selected in which archaeological studies were carried out some years ago, which were then covered over. The aim was to try to establish a comparison between the existing structures and those detected by the ground penetrating radar. Most of the structures were re-covered fifteen years ago, except those at the western end that were covered in 2019 (Aguelo, 2020). This is important, as it has a direct impact on the interpretation of the results. The differences in the results are notable. In much of the excavated area, the results of the prospecting largely verify the structures located in the archaeological studies. However, in the sector that was filled in a few months before the prospecting, only the outer limits of the excavation were identified, without being able to determine the existing structures.

6 Conclusions

Despite the technical difficulties posed a priori by the characteristics of the site, the prospecting carried out in the medieval town provided significant data on the configuration of this town’s urban structure (Figure 10). However, some of the questions that were established initially could not be answered. This was due mainly to the limitations that are inherent in the establishment of the work methodology. The limitations in the depth range in some of the areas (hill of Santa Maria, west sector), meant that the research depth was less than 1.2 m to 1.4 m, which failed to exhaust the extensive sequence of occupation established by archaeology. This fact causes a problem, especially in the northwest area of the village, since most of the possible late-antique structures, which could be easily identified as they have a different orientation, do not appear in the surveys. This fact does not allow for a deeper knowledge of the theoretical limits of the Late Antique settlement.

Overlay of the theoretical urban plan with the geophysical survey results.

Another decisive factor in the interpretation of the data was the abundance of deposits with heterogeneous infill and layers of building debris, due to the successive changes in the spaces that were explored. The use of rubble and material of all kinds for levelling out the ground or the demolition of structures in disuse tends to produce a highly reflective response. However, it also leads to clear difficulties in discerning construction waste inside these demolitions or levelled-out areas.

In general, the prospecting enabled the clear reconstruction of the urban structure inside the town. The urban organisation, with long plots, some oriented north to south and others east to west, was also verified, especially in the sectors closest to the monastery of Santa Maria and in the southwest sector. In this area, a variation of the inner plots was identified with a rotation to the northwest. Although this variation is associated visually with the orientation that marks the south wall of the town, it should be noted that the real situation is the other way around, given that the wall was built after the urban extension area and as a result of it. Therefore, another topographic element must have existed that affected this rotation, perhaps the course of the Trencada Creek that ran to the west of the town.

A relevant novelty can be observed in the apparent layout of the plots in the southwest area. It is a sector with very wide blocks and, normally, it has been interpreted that the plots would be oriented north-south, as in fact happens in the excavated sector of the northwest quadrant. The layout of the identified walls shows an east-west orientation of the buildings and the existence of two possible north–south streets (Figure 7). The documentation only indicates one north–south street in the sector (Carrer d’en Vaca), which could correspond to the line of walls found in the western sector. On the other hand, the possible alleyway visible to the east (between points 3 and 4) does not appear in the written documentation or in the plans of the modern period.

In this sector, moreover, work was carried out in the knowledge that the structures identified must be from the medieval or modern period, given that in ancient times almost the entire sector was under the sea.

The prospecting also provided data on the walled enclosure, with the identification of what could correspond to a part of the north section of the walls in the area closest to the monastery. In contrast, none of the anomalies detected could be associated with the existence or the course of the south wall of an initial walled enclosure from the Early Middle Ages and its supposed extension to the south of the monastery. Their existence is not certain and, in fact, the lack of this type of defence was common in the first villas, prior to the mid-twelfth century (Farías, 2009, p. 240). In spite of this, we believe that, given its position, the town must have had defences, although these would not have been as we have seen so far. It would be an enclosure that would only surround the urban nucleus, leaving out the monastery, which had its own defences. To the west and north it would follow the same circuit as the fourteenth-century wall, to the east it would be located under a wall that currently acts as a retaining wall for the space in front of the monastery, and to the south it would probably be located under Hospital Street (on this hypothesis Palahi et al., 2022).

Also relevant are the results obtained in the area of the square located to the west of the monastery (Figure 8). It is a space that in medieval times formed a square. The surveys have made it possible to identify part of the route of the fourteenth-century north wall, with its possible gateway (36). This gateway, known as the Damunt gateway, is well documented from at least 1361 (Pujol, 1997, p. 63). The area of the square occupied the entire surface, but in 1304 (Pujol, 1997, p. 53) structures such as the dunghill (femoracium) or the oven (forno) (Pujol, 1997, p. 59) were already documented there (Pujol, 1997, p. 59). On the other hand, the building built against the west wall of the monastery and partially visible before the prospections appears in military plans from the sixteenth century (Figure 3).

The superficiality of the structures identified makes it unlikely that they belong to the Late Antique or Greek phases, which are located in the excavations, carried out in the monastery sector at much more profound levels.

The area to the east of the monastery is one of the most problematic. In medieval and modern times, it is an apparently unbuilt area (except for the storeroom still preserved next to the wall, built in the seventeenth century), but in the Late Antique period, it must have been integrated into the necropolis of the cella memoria. It remains to be ascertained whether the few distortions located belong to tombs from this cemetery or to structures from earlier phases. In fact, the excavation of the warehouse mentioned above provided a space densely occupied by burials. These were arranged between a series of walls that were not dated at the time, and which would suggest that this sector was occupied in an ancient period that has not yet been sufficiently explored.

Consequently, this study is an example of the use of archaeological geophysics and the fact that archaeological verification studies and the review of historical mapping provide additional information that could be of great relevance in the reinterpretation of geophysical data.

Acknowledgments

The research for this paper was conducted under the project “Urbanisme, poblament i conflicte en època medieval i moderna. La vila de Rosas com a paradigma” (CLT_2022_EXP_ARQ001SOLC_00000195) (Urban development, settlement and conflict in the medieval and modern era. The town of Rosas as a paradigm).

-

Funding information: The work was financed by the Càtedra Roses d'Arqueologia i Patrimoni Arqueològic.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and consented to its submission to the journal, reviewed all the results, and approved the final version of the manuscript. LLP, MB, and RS prepared the manuscript with contributions from all co-authors. LLP has directed the archaeological excavations. RS, HO, and PR have carried out geophysical surveys.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Aguelo, X. (2020). Intervencions per protegir i adequar diferents espais a l’interior de la Ciutadella de Rosas (Rosas, Alt Empordà). In J. Burch, R. Buxó, J. Frigola, M. Fuertes, S. Manzano, & M. Mataró, Quinzenes Jornades d’Arqueologia de les comarques de Girona, Castelló d’Empúries (pp. 375–377). Documenta Universitaria.Suche in Google Scholar

Aguelo, X., & Pujol, M. (2020). Ciutadella de Rosas- Muralla medieval, costat de llevant (Rosas, Alt Empordà). In J. Burch, R. Buxó, J. Frigola, M. Fuertes, S. Manzano, & M. Mataró, Quinzenes Jornades d’Arqueologia de les comarques de Girona, Castelló d’Empúries (pp. 371–374). Documenta Universitaria.Suche in Google Scholar

Annan, A. P. (2009). Electromagnetic principles of ground penetrating radar. In H. M. Jol (Ed.), Ground penetrating radar theory and applications (pp. 1–40). Elsevier. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-53348-7.00001-6.Suche in Google Scholar

Betran Abadía, R. (2005). Planeamiento y geometria en la Ciudad Medieval Aragonesa. Arqueologia y Territorio Medieval, 12(2), 75–146.10.17561/aytm.v12i2.1712Suche in Google Scholar

Bouzas, M., Burch, J., Julià, R., Palahí, Ll., Pons, P., & Solà, J. (2023). Changes and transformations on the coastal. The exemple of Roses (Alt Empordà, Catalonia). Land, 12, 2104. doi: 10.3390/land12122104.Suche in Google Scholar

Bouzas, M., & Palahí, Ll. (2024). Roses de la tardoantiguitata a l'època medieval. In M. Bouzas & Ll. Palahí (Eds.), De la tardoantiguitat a l’alta edat mitjana: una visió arqueològica, MonCRAPA, (Vol. 1, pp. 199–212). Documenta Universitaria. https://www.documentauniversitaria.media/omp/index.php/crapa/catalog/book/moncrapa-1.Suche in Google Scholar

Castells, R., Catllar, B., & Riera, J. (1994), Ciutats de Girona. Catàleg de plànols de les Ciutats de Girona des del segle XVII al XX. Col·legi d’Arquitectes.Suche in Google Scholar

Conyers, L. B., & Goodman, D. (1997). Ground-penetrating radar: An introduction for archaeologists. AltaMira Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Davis, J. L., & Annan, A. P. (1989). Ground-penetrating radar for high-resolution mapping of soil and rock stratigraphy. Geophysical Prospecting, 37, 531–551.10.1111/j.1365-2478.1989.tb02221.xSuche in Google Scholar

De la Fuente, P. (1998). Les fortificacions reials del golf de Rosas en l’època moderna, (Col·lecció Papers de Recerca, 3). Ajuntament de Rosas.Suche in Google Scholar

De la Fuente, P. (2016). Luís Pizaño y sus proyectos para Rosas: Idea, traza y decisión. In A. Cámara (Ed.), El dibujante ingeniero al servicio de la monarquia hispánica. Siglos XVI–XVIII (pp. 181–196). Fundación Juan Turriano.Suche in Google Scholar

Farías, V. (2009). El mas i la vila a la Catalunya medieval. Els fonaments d’una societat senyorialitzada (segles XI–XIV). Publicacions de la Universitat de València.Suche in Google Scholar

Garcia-Garcia, E., De Prado, G., & Principal, J. (Eds.). (2016). Working with buried remains at Ullastret (Catalonia). Proceedings of the 1st MAC International Workshop of Archaeological Geophysics. Museu d’Arqueologia de Catalunya-Ullastret.Suche in Google Scholar

Linford, N. T., & Canti, M. G. (2001). Geophysical evidence for fires in antiquity: Preliminary results from an experimental study. Paper given at the EGS XXIV General Assembly in The Hague, April 1999. Archaeological Prospection, 8(4), 211–225. doi: 10.1002/arp.170.Suche in Google Scholar

Mallorquí, E. (2022). Celleres i viles fortificades de les terres gironines (segles XI–XIV). Evidències a partir de la documentació escrita, RODIS. Journal of Medieval and Post-Medieval Archaeology, 5, 81–112.10.33115/a/26046679/5_4Suche in Google Scholar

Martí, R. (1988), L’ensagrerament: l’adveniment de les sagreres feudals, Faventia, 10, 153–182.Suche in Google Scholar

Palahí, Ll., & Burch, J. (2018). La Ciutadella de Rosas. Intervenció al sector dels forns de munició del s.XVIII. In Catorzenes Jornades d’Arqueologia de les Comarques de Girona (pp. 787–792). Generalitat de Catalunya.Suche in Google Scholar

Palahí, Ll., Pujol, M., & Aguelo, X. (2022). Les muralles del monestir de Santa Maria i la vila de Roses a l’Edat Mitjana, RODIS. Journal of Medieval and Post-medieval Archaeology, 5, 125–150. doi: 10.33115/a/26046679/5_6.Suche in Google Scholar

Puig, A. M. (1994). La Ciutadella. 1a campanya memòria (desembre 1993–gener 1994), maig 1994. Generalitat de Catalunya.Suche in Google Scholar

Puig, A. M. (2006). La paleotopografia del jaciment a partir dels estudis arqueològics. In A. M. Puig & A. Martín (Eds.), La colònia grega de Rhode (Rosas, Alt Empordà) (pp. 35–38). Museu d’Arqueologia de Catalunya (Sèrie Monogràfica, 23).Suche in Google Scholar

Puig, A. M. (2012). La problemàtica de l’entorn periurbà de Rhode. In C. Belarte & R. Plana (Eds.), El paisatge periurbà a la Mediterrània occidental durant la protohistòria i l’antiguitat: actes del col·loqui internacional (p. 83–98). Institut Català d’Arqueologia Clàssica (Documenta, 26).Suche in Google Scholar

Puig, A. M. (2016). L’evolució urbana de la vila de Roses. La trama ortogonal i la parcel·lació gòtica a l’ampliació del segle XIII. Annals de l’Institut d’Estudis Empordanesos, 47, 341‑380. doi: 10.2436/20.8010.01.209.Suche in Google Scholar

Puig, A. M. (2020), La modulació urbana a l’eixample baixmedieval de Roses. El prototip de casa. RODIS Journal of Medieval and Postmedieval Archaeology, 3, 35–56. https://www.documentauniversitaria.media/rodis/index.php/rodis/article/view/21.Suche in Google Scholar

Puig, A. M., & Martín, A. (Eds.). (2006). La colònia grega de Rhode (Roses, Alt Empordà). MAC-Girona, (Sèrie Monogràfica, 23).Suche in Google Scholar

Pujol, M. (1997). La vila de Roses (segles XIV-XVI): aproximació a l'urbanisme, la societat i l'economia a partir dels capbreus del monestir de Santa Maria de Roses (1304–1565). El Brau.Suche in Google Scholar

Pujol, M. (2018). L urbanisme de la vila de Roses (segles XI‑XVIII). Rodis: journal of medieval and postmedieval archaeology, 1, 72–94.Suche in Google Scholar

Sala, R., Garcia, E., & Tamba, R. (2012). Archaeological geophysics. From basics to new perspective. In I. Ollich-Castanyer (Ed.), Archaeology, new approaches in theory and techniques (pp. 133–166). InTech. doi: 10.5772/45619.Suche in Google Scholar

Schmidt, A., & Tsetskhladze, G. (2013). Raster was yesterday: Using vector engines to process geophysical data. Archaeological Prospection, 20(1), 59–65. doi: 10.1002/arp.1443.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Etched in Stone: The Kevermes Stone Stela From the Great Hungarian Plain

- Waste Around Longhouses: Taphonomy on LBK Settlement in Hlízov

- Raw Materials and Technological Choices: Case Study of Neolithic Black Pottery From the Middle Yangtze River Valley of China

- Disentangling Technological Traditions: Comparative Analysis of Chaînes Opératoires of Painted Pre-Hispanic Ceramics From Nariño, Colombia

- Ancestral Connections: Re-Evaluating Concepts of Superimpositioning and Vandalism in Rock Art Studies

- Disability and Care in Late Medieval Lund, Sweden: An Analysis of Trauma and Intersecting Identities, Aided by Photogrammetric Digitization and Visualization

- Assessing the Development in Open Access Publishing in Archaeology: A Case Study From Norway

- Decorated Standing Stones – The Hagbards Galge Monument in Southwest Sweden

- Geophysical Prospection of the South-Western Quarter of the Hellenistic Capital Artaxata in the Ararat Plain (Lusarat, Ararat Province, Armenia): The South-West Quarter, City Walls and an Early Christian Church

- Lessons From Ceramic Petrography: A Case of Technological Transfer During the Transition From Late to Inca Periods in Northwestern Argentina, Southern Andes

- An Experimental and Methodological Approach of Plant Fibres in Dental Calculus: The Case Study of the Early Neolithic Site of Cova del Pasteral (Girona, Spain)

- Bridging the Post-Excavation Gaps: Structured Guidance and Training for Post-Excavation in Archaeology

- Everyone Has to Start Somewhere: Democratisation of Digital Documentation and Visualisation in 3D

- The Bedrock of Rock Art: The Significance of Quartz Arenite as a Canvas for Rock Art in Central Sweden

- The Origin, Development and Decline of Lengyel Culture Figurative Finds

- New “Balkan Fashion” Developing Through the Neolithization Process: The Ceramic Annulets of Amzabegovo and Svinjarička Čuka

- From a Medieval Town to the Modern Fortress of Rosas (Girona-Spain). Combining Geophysics and Archaeological Excavation to Understand the Evolution of a Strategic Coastal Settlement

- Technical Transfers Between Chert Knappers: Investigating Gunflint Manufacture in the Eastern Egyptian Desert (Wadi Sannur, Northern Galala, Egypt)

- Early Neolithic Pottery Production in the Maltese Islands: Initiating a Għar Dalam and Skorba Pottery Fabric Classification

- Revealing the Origins: An Interdisciplinary Study Into the Provenance of Sacral Microarchitecture–The Unique Case of the Church Model From Žatec in Bohemia

- An Analogical and Analytical Approach to the Burçevi Monumental Tomb

- A Glimpse at Raw Material Economy and Production of Chipped Stones at the Neolithic (Starčevo) Site of Svinjarička Čuka, South Serbia

- Archaeological Lithotheques of Siliceous Rocks in Spain: First Diagnosis of the Lithotheque Thematic Network

- Mapping Changes in Settlement Number and Demography in the South of Israel from the Hellenistic to the Early Islamic Period

- Review Article

- Structural Measures Against the Risks of Flash Floods in Patara and Consequent Considerations Regarding the Location of the Oracle Sanctuary of Apollo

- Commentary Article

- A Framework for Archaeological Involvement with Human Genetic Data for European Prehistory

- Special Issue on Digital Religioscapes: Current Methodologies and Novelties in the Analysis of Sacr(aliz)ed Spaces, edited by Anaïs Lamesa, Asuman Lätzer-Lasar - Part II

- Goats and Goddesses. Digital Approach to the Religioscapes of Atargatis and Allat

- Conceiving Elements of Divinity: The Use of the Semantic Web for the Definition of Material Religiosity in the Levant During the Second Millennium BCE

- Deep Mapping the Asklepieion of Pergamon: Charting the Path Through Challenges, Choices, and Solutions

- Special Issue on Engaging the Public, Heritage and Educators through Material Culture Research, edited by Katherine Anne Wilson, Christina Antenhofer, & Thomas Pickles

- Inventories as Keys to Exploring Castles as Cultural Heritage

- Hohensalzburg Digital: Engaging the Public via a Local Time Machine Project

- Monastic Estates in the Wachau Region: Nodes of Exchange in Past and Present Days

- “Meitheal Adhmadóireachta” Exploring and Communicating Prehistoric Irish Woodcraft Through Remaking and Shared Experience

- Community, Public Archaeology, and Co-construction of Knowledge Through the Educational Project of a Rural Mountain School

- Valuing Material Cultural Heritage: Engaging Audience(s) Through Development-Led Archaeological Research

- Engaging the Public Through Prehistory: Experiences From an Inclusive Perspective

- Material Culture, the Public, and the Extraordinary – “Unloved” Museums Objects as the Tool to Fascinate

- Archaeologists on Social Media and Its Benefits for the Profession. The Results and Lessons Learnt from a Questionnaire

- Special Issue on Network Perspectives in the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East and Eastern Mediterranean, edited by Maria Gabriella Micale, Helen Dawson, & Antti A. Lahelma

- Networks of Pots: The Usage of Ceramics in Network Analysis in Mediterranean Archaeology

- Networks of Knowledge, Materials, and Practice in the Neolithic Zagros

- Weak Ties on Old Roads: Inscribed Stopping-Places and Complex Networks in the Eastern Desert of Graeco-Roman Egypt

- Mediterranean Trade Networks and the Diffusion and Syncretism of Art and Architecture Styles at Delos

- People and Things on the Move: Tracking Paths With Social Network Analysis

- Networks and the City: A Network Perspective on Procopius De Aed. I and the Building of Late Antique Constantinople

- Network Perspectives in the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East and Eastern Mediterranean

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Etched in Stone: The Kevermes Stone Stela From the Great Hungarian Plain

- Waste Around Longhouses: Taphonomy on LBK Settlement in Hlízov

- Raw Materials and Technological Choices: Case Study of Neolithic Black Pottery From the Middle Yangtze River Valley of China

- Disentangling Technological Traditions: Comparative Analysis of Chaînes Opératoires of Painted Pre-Hispanic Ceramics From Nariño, Colombia

- Ancestral Connections: Re-Evaluating Concepts of Superimpositioning and Vandalism in Rock Art Studies

- Disability and Care in Late Medieval Lund, Sweden: An Analysis of Trauma and Intersecting Identities, Aided by Photogrammetric Digitization and Visualization

- Assessing the Development in Open Access Publishing in Archaeology: A Case Study From Norway

- Decorated Standing Stones – The Hagbards Galge Monument in Southwest Sweden

- Geophysical Prospection of the South-Western Quarter of the Hellenistic Capital Artaxata in the Ararat Plain (Lusarat, Ararat Province, Armenia): The South-West Quarter, City Walls and an Early Christian Church

- Lessons From Ceramic Petrography: A Case of Technological Transfer During the Transition From Late to Inca Periods in Northwestern Argentina, Southern Andes

- An Experimental and Methodological Approach of Plant Fibres in Dental Calculus: The Case Study of the Early Neolithic Site of Cova del Pasteral (Girona, Spain)

- Bridging the Post-Excavation Gaps: Structured Guidance and Training for Post-Excavation in Archaeology

- Everyone Has to Start Somewhere: Democratisation of Digital Documentation and Visualisation in 3D

- The Bedrock of Rock Art: The Significance of Quartz Arenite as a Canvas for Rock Art in Central Sweden

- The Origin, Development and Decline of Lengyel Culture Figurative Finds

- New “Balkan Fashion” Developing Through the Neolithization Process: The Ceramic Annulets of Amzabegovo and Svinjarička Čuka

- From a Medieval Town to the Modern Fortress of Rosas (Girona-Spain). Combining Geophysics and Archaeological Excavation to Understand the Evolution of a Strategic Coastal Settlement

- Technical Transfers Between Chert Knappers: Investigating Gunflint Manufacture in the Eastern Egyptian Desert (Wadi Sannur, Northern Galala, Egypt)

- Early Neolithic Pottery Production in the Maltese Islands: Initiating a Għar Dalam and Skorba Pottery Fabric Classification

- Revealing the Origins: An Interdisciplinary Study Into the Provenance of Sacral Microarchitecture–The Unique Case of the Church Model From Žatec in Bohemia

- An Analogical and Analytical Approach to the Burçevi Monumental Tomb

- A Glimpse at Raw Material Economy and Production of Chipped Stones at the Neolithic (Starčevo) Site of Svinjarička Čuka, South Serbia

- Archaeological Lithotheques of Siliceous Rocks in Spain: First Diagnosis of the Lithotheque Thematic Network

- Mapping Changes in Settlement Number and Demography in the South of Israel from the Hellenistic to the Early Islamic Period

- Review Article

- Structural Measures Against the Risks of Flash Floods in Patara and Consequent Considerations Regarding the Location of the Oracle Sanctuary of Apollo

- Commentary Article

- A Framework for Archaeological Involvement with Human Genetic Data for European Prehistory

- Special Issue on Digital Religioscapes: Current Methodologies and Novelties in the Analysis of Sacr(aliz)ed Spaces, edited by Anaïs Lamesa, Asuman Lätzer-Lasar - Part II

- Goats and Goddesses. Digital Approach to the Religioscapes of Atargatis and Allat

- Conceiving Elements of Divinity: The Use of the Semantic Web for the Definition of Material Religiosity in the Levant During the Second Millennium BCE

- Deep Mapping the Asklepieion of Pergamon: Charting the Path Through Challenges, Choices, and Solutions

- Special Issue on Engaging the Public, Heritage and Educators through Material Culture Research, edited by Katherine Anne Wilson, Christina Antenhofer, & Thomas Pickles

- Inventories as Keys to Exploring Castles as Cultural Heritage

- Hohensalzburg Digital: Engaging the Public via a Local Time Machine Project

- Monastic Estates in the Wachau Region: Nodes of Exchange in Past and Present Days

- “Meitheal Adhmadóireachta” Exploring and Communicating Prehistoric Irish Woodcraft Through Remaking and Shared Experience

- Community, Public Archaeology, and Co-construction of Knowledge Through the Educational Project of a Rural Mountain School

- Valuing Material Cultural Heritage: Engaging Audience(s) Through Development-Led Archaeological Research

- Engaging the Public Through Prehistory: Experiences From an Inclusive Perspective

- Material Culture, the Public, and the Extraordinary – “Unloved” Museums Objects as the Tool to Fascinate

- Archaeologists on Social Media and Its Benefits for the Profession. The Results and Lessons Learnt from a Questionnaire

- Special Issue on Network Perspectives in the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East and Eastern Mediterranean, edited by Maria Gabriella Micale, Helen Dawson, & Antti A. Lahelma

- Networks of Pots: The Usage of Ceramics in Network Analysis in Mediterranean Archaeology

- Networks of Knowledge, Materials, and Practice in the Neolithic Zagros

- Weak Ties on Old Roads: Inscribed Stopping-Places and Complex Networks in the Eastern Desert of Graeco-Roman Egypt

- Mediterranean Trade Networks and the Diffusion and Syncretism of Art and Architecture Styles at Delos

- People and Things on the Move: Tracking Paths With Social Network Analysis

- Networks and the City: A Network Perspective on Procopius De Aed. I and the Building of Late Antique Constantinople

- Network Perspectives in the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East and Eastern Mediterranean