Abstract

Across a fragmented landscape, the Neolithic communities of the Zagros Mountains (in modern Iraq and Iran) maintained complex networks of material exchange and knowledge transfer. From the early Holocene, small groups of people explored new ways of doing and being in the world, sharing innovative ideas with one another through tangible material media. Drawing on research at sites in the Central Zagros, case studies illustrate differing approaches to the curation of networks amongst the inhabitants of highland and lowland landscapes from the Epipalaeolithic to the Chalcolithic. Through key material strands and shared networks of practice, we can identify catalysing factors behind the growth of communication networks in the Early Neolithic and consider the implications of intensified connections. The research addresses transects through time and landscapes through inter-disciplinary research at PPNA Sheikh-e Abad and Jani in the high Zagros of Iran and in the Zagros foothills at Epipalaeolithic Zarzi Cave, a PPNA open-air site Zawi Chemi Rezan, PPNB Bestansur, and Shimshara in the Kurdish Region of Iraq. This article examines material case studies from these sites and considers how engagement with networks was selective and contingent for individual communities.

1 Networks of Interaction Shaping Neolithic Communities

The people of the Central Zagros Mountains, spanning the border of modern Iraq and Iran, maintained complex networks of material exchange and knowledge transfer across topographically diverse landscapes and challenging terrains between 10,000 and 7,000 BC. In the material record, we find traces of the manifestation of the curation of networks and engagement with communities throughout Southwest Asia. Through key material strands, it is possible to identify the consolidation of communication networks and knowledge transfer in the Early Neolithic and shed light on the implications of intensified connections and increased exchanges between sedentarising communities. The power of networks in prehistoric periods can pose considerable challenges in identifying both the trajectories and significance of the networks that transformed the way people lived and engaged with the world around them. Without textual evidence, we rely solely on tangible and material evidence to examine the traces of networks that shaped and were shaped by the first sedentary communities.

These networks of interaction took place at a range of scales and between a range of actors, whether that be people and people (Gowlett et al., 2012), between people and things (Knappett, 2011; Mithen et al., 2023), people and materials (Malafouris, 2013), or people and the environment (Coward & Howard-Jones, 2021). Any alteration in the balance of interactions between people, things, places, environment, plants, and animals can be a driver for change, and as Hodder has highlighted in his studies, some of these may be the unintended consequences of our own pursuit of stasis (Hodder, 2012). Active resistance to interaction is a form of interaction in itself. Communities in the Neolithic Zagros did not uniformly subscribe to networks of interaction; there are instances of resistance to change and deliberate disengagement from networks. Excavations at the Neolithic settlement of Tol-e Bashi in Iran revealed an example of resistance to the highly connected communities across the Zagros through the minimal engagement with repertoires of durable objects (Pollock et al., 2010), where life was deliberately perishable and untangled.

Networks of interacting communities provide a useful framework through which to examine material and social connections in the landscape. Watkins has advocated for network approaches in the Fertile Crescent, at local and intra-regional scales, in conjunction with cognitive-evolutionary understandings of change (Watkins, 2003, 2006, 2008). It was the paradox between increasingly sedentary and increasingly interacting societies that he suggests forged networks “in the manner of nested peer-polity interaction spheres” (Watkins, 2008, p. 165). The construction of “socio-material” (as opposed to strictly “social”) networks (Knappett, 2011) has used material culture “as a proxy for the strength of social relationships” across Epipalaeolithic and Neolithic Southwest Asia (Coward, 2010, 2013), although this work has highlighted the challenges of timescales in the prehistoric past and the limitations of the archaeological record in accurately representing complex networks that may not have been materialised. The issues of scale have been successfully overcome through the successful application of modelling approaches to intra-site networks between households at the Neolithic site of Çatalhöyük, which have demonstrated an intensification of networks and increasing interconnectivity through time (Mazzucato, 2019).

Coward’s (2013) work has highlighted how burgeoning settlement populations do appear to have strained relationships, to the detriment of intra-site networks. This tension deriving from social interactions draws on Dunbar’s work on the scale of human social networks (1993, 2008), averaging 150 people. This number recurs throughout our hierarchical structures, including the average Neolithic village size. As the population increases, it could lead to a severing of connections or fission of the group. These critical units do, however, maintain networks with external units, for support, reciprocities, and future securities, which may provide some insight into the impetus for extensive material networks.

Interactions with external forces have powerful influences that shape the human brain through neural plasticity. In infancy, interactions with people, material things, sounds, and smells give shape to our understanding of the world. They forge the pathways for learning and provide the scaffolding to interpret experiences (Snell-Rood & Snell-Rood, 2020; Tymofiyeva & Gaschler, 2021). Interactions affect the way people act, think, and relate to the world around us. Although some of this is defined in early years, cognition, capacity, and creativity can all be developed and enhanced by our interactions. The cognitive benefits of learning a second language are well established (Ware et al., 2021) and time spent living abroad, or even making friends from different cultural backgrounds, enhances our creative capacities in problem-solving (Maddux & Galinsky, 2009).

Interactions change the way we think about, comprehend, and engage with the world around us. This is fundamental in our understanding of change in the archaeological record. The material changes we observe are shifts in the cognition of the people we study, not ideas superimposed, or adopted, or assimilated, but creative expressions of new ways of thinking and being. These interactions are so prominent in the archaeological record that they appear to be developed beyond necessity, as Karl Knappett observed: “…it is not only that humans have particular capacities for interconnecting; they seem driven to do so almost regardless of any functional advantage that may or may not be conferred” (Knappett, 2011, p. 12). In this framework, Neolithic networks of interaction comprise human engagements that are pursued not simply for material benefit, but as a social tool that is fundamental to constructing communities with greater capacity for learning and adapting to the world.

Through the development of artificial intelligence, research is revealing the complexity of physical interactions with the material world. Advances in AI are only now developing machines that can simulate human capabilities to fuse complex strategies with interactive perception. In the field of self-driving cars, AI training in experience-based decision-making processes utilised exploration games from the 1980s to learn how to cope with obstacles and hazards (Mnih et al., 2015). Recent developments in robotics have attempted to mimic human physical learning through tangible experience, rather than through modelling the parameters and contingencies (Fazeli et al., 2019). Humans learn from these principles of physical, real-world experience in infancy, but they are entirely dependent on the experiences to which they have been exposed. In the Neolithic, the neural networks of individuals developed in response to the changing physical and social worlds they experienced, developing cognitive capacities for comprehending the affordances and possibilities to creatively reimagine the material world.

The archaeological traces of networks of knowledge in the Neolithic Zagros represent the exchange of active, embodied, physical knowledge of making, crafting, and building. The creative capacity endowed by flexible thinking, by the benefits of interaction and engagement with the world, may have benefitted communities in the past. But the benefits of interactions are not only cognitive – resource security through diversification is an issue faced by both ancient and modern communities, whether it be through food, fuel, or even genetic diversification. Collective gathering in Neolithic communal spaces, such as Göbekli Tepe in Türkiye and WF16 in Jordan, provided opportunities for interactions between people (Dietrich et al., 2012; Mithen, 2020; Mithen et al., 2023). Communal spaces may have been integral to the development of relationships through commensality, generosity, and co-mingling of populations, which would have reinforced obligations to provide support in times of challenge. These interactions between Neolithic individuals and communities may not have been symmetrical, bound as they were with the social complexities of obligation, dependency, and power (Graeber & Wengrow, 2022), but they appear to have played a vital catalysing role in a period of extensive change. Through examples from the Central Zagros, we can begin to trace some of the networks in which people participated at a range of scales and begin to identify the impact these had on Neolithic lifeways.

2 Investigating Networks in the Neolithic Central Zagros

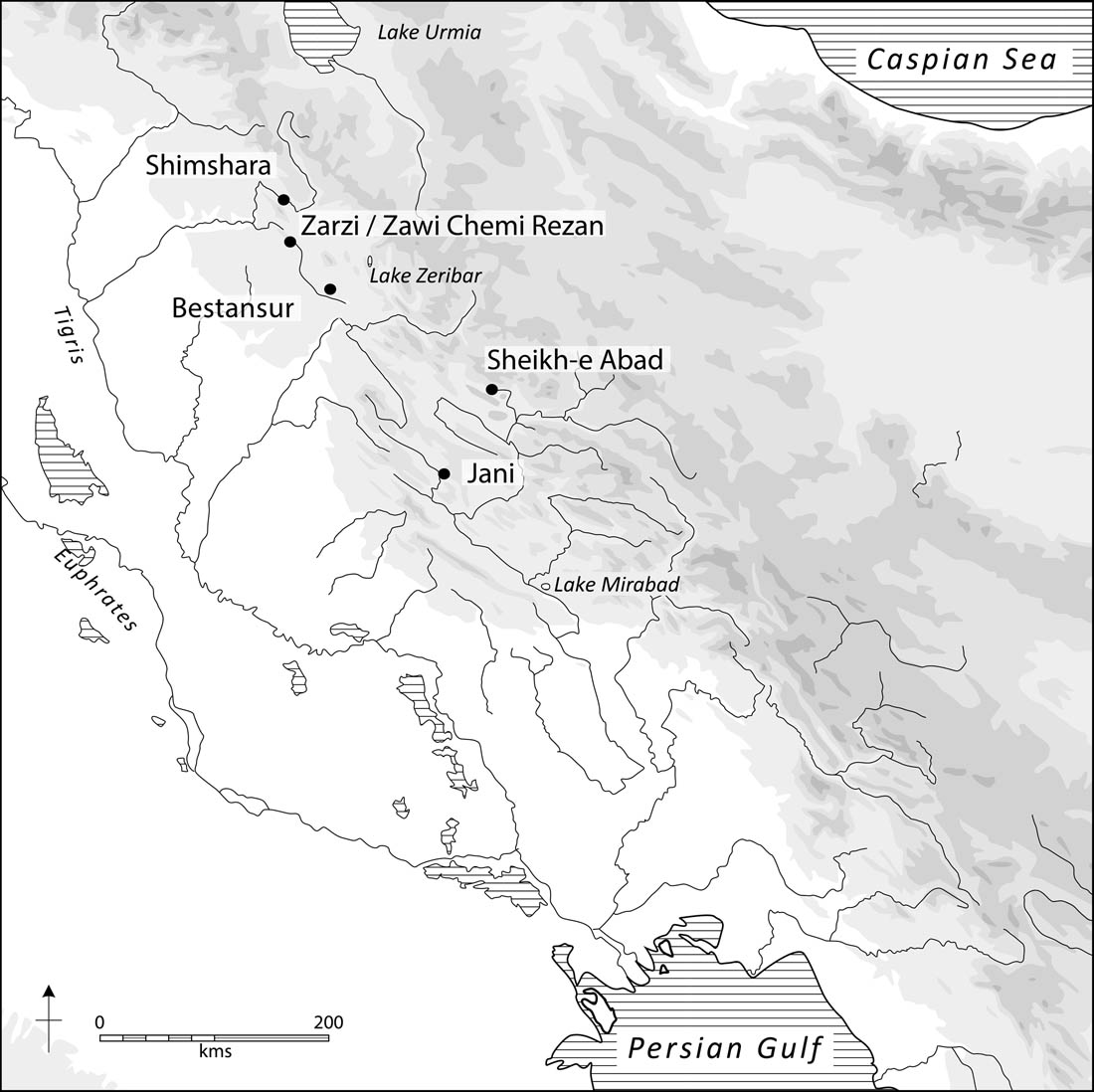

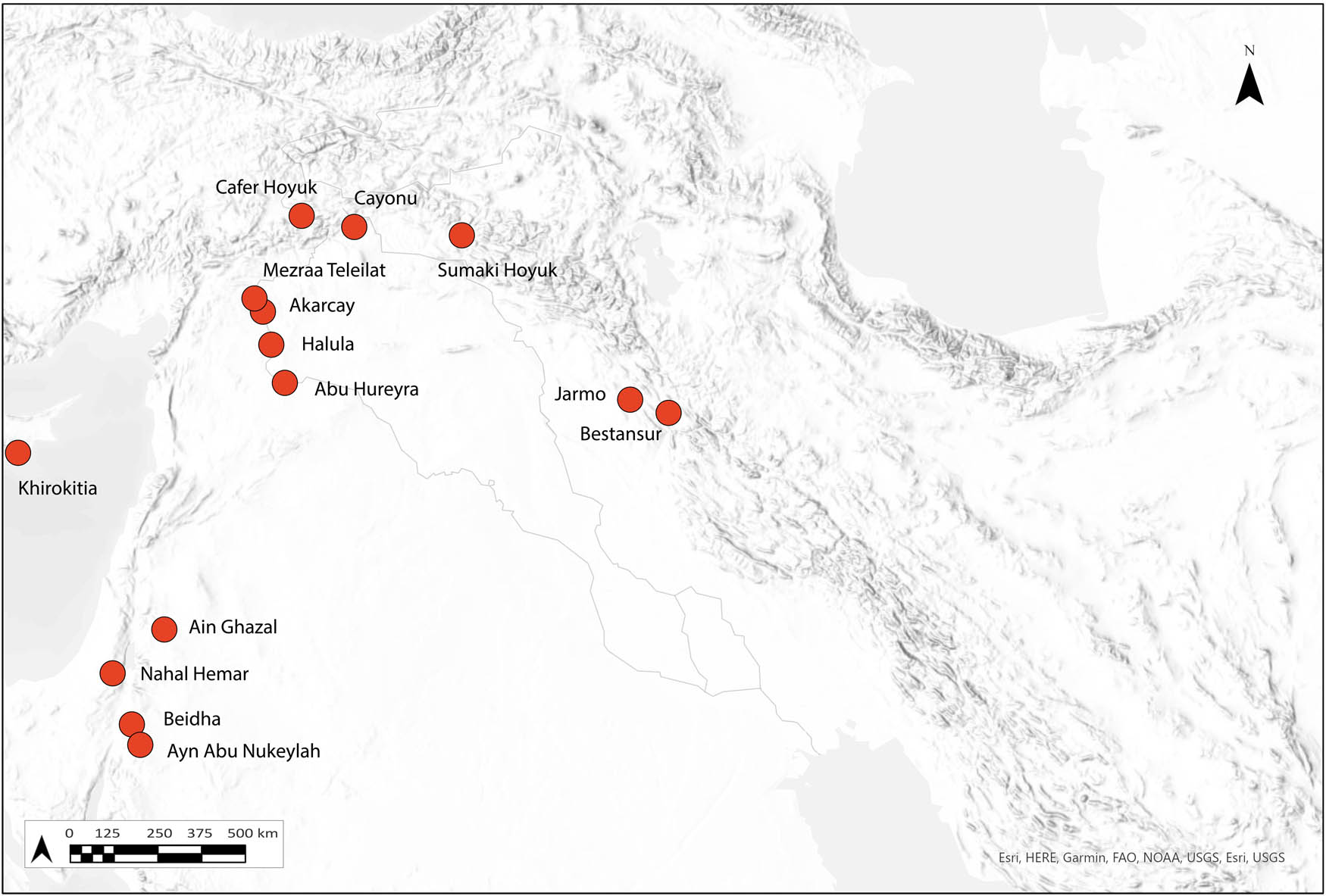

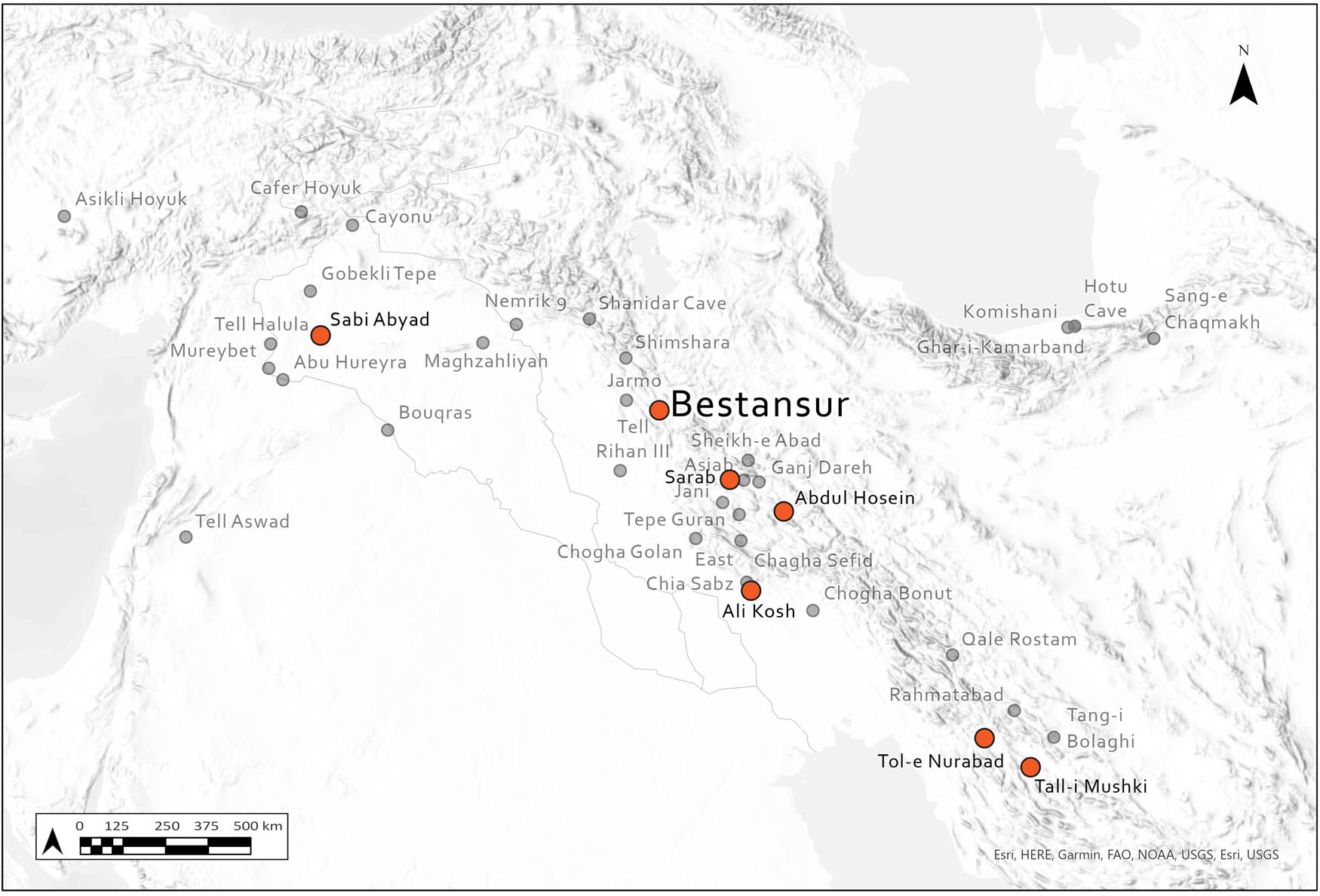

The Central Zagros is a crucial zone of major passes connecting lowlands and uplands through the Zagros Mountains, connecting Southwest and Central Asia (Figure 1). Since 2008, the Central Zagros Archaeological Project (CZAP), led by Roger Matthews and Wendy Matthews (University of Reading) with colleagues in Iraq and Iran, has been investigating sites that span from 12,000 to 7,000 BC (Figure 2). Each site demonstrates different approaches to engagement with regional networks at intervals through the Neolithic transition. Investigations have been conducted at Epipalaeolithic Zarzi Cave and an associated Early Neolithic open-air site, early settlements at tenth to eighth-millennium Sheikh-e Abad and Jani in Iran, and eighth-millennium communities at Bestansur and Shimshara (Matthews et al., 2013b, 2020d).

Map of sites excavated by the Central Zagros Archaeological Project.

Views of sites excavated by the Central Zagros Archaeological Project.

In the Epipalaeolithic to Early Neolithic Transition, mobile communities engaged in “long-distance transport or informal trade” in the form of shell beads and pendants, which were transported hundreds of kilometres to the Zagros, possibly from the Persian Gulf (Olszewski, 2012). With these objects travelled “concepts, knowledge and ideas” (Richter et al., 2011, p. 108) that extended from the Zagros to the Levant (Hole, 1996). This was a period of intensifying occupation in which people experimented with new material and technological repertoires. Early Neolithic communities expanded beyond the scrub-steppe of the mountain slopes, to low bluffs and rises in the fertile valleys. Increasing commonalities in material culture, plant and animal management strategies, and architectural approaches have been conceptualised as the components of a “PPNB interaction sphere,” modelled on a core-periphery system of settlements exchanging materials such as obsidian, shell, and turquoise as a means of negotiating social relationships (Asouti, 2006; Bar-Yosef, 2002; Bar-Yosef & Belfer-Cohen, 1989).

Raw materials played a vital role in the success of these first settlements. The limestone outcrops of the Zagros Mountains provided ample stone for grinding and chert sources for making stone tools, with readily available nodules and cobbles collected from the riverbeds. Stone was also used for making figurines, bracelets, and bowls, from alabaster and marble. In locating settlements in the Zagros foothills, inhabitants were able to experiment with the rich natural resources available. Rich clays were abundantly available for building and for making objects, figurines, tokens, beads, plastering walls, and lining floors. Depending on its purpose, it could be cleaned thoroughly to remove impurities, or tempered with chaff or grit, and fixed in its form with fire and heat. Materials were not simply functional but selected for aesthetic purposes, to decorate and paint buildings, or make adornments. Occasional fragments of obsidian, similarities in figurine styles, or the construction of houses hint at the long-distance relationships in operation between these small communities. Through networks of exchange, people were acquiring new materials, learning their affordant properties, and co-creating new ideas.

2.1 The Sites

Dorothy Garrod’s excavations in the 1920s established Zarzi Cave as the type-site for the Epipalaeolithic stone tool industry across the region, consolidated by Wahida’s subsequent excavations in the 1980s (Garrod, 1930; Wahida, 1981). Situated on the slopes of the Chemi Rezan valley, 750 m asl, the small rockshelter overlooks a biodiverse river that joins the Lesser Zab (Nature Iraq, 2017). A survey of the Chemi Rezan valley in 2013 identified an open-air site on the slopes facing the cave, based on the presence of ground stone tools and lithics (site ZS3 in the survey and now named Zawi Chemi Rezan, 670 m asl) (Matthews et al., 2020b). An intensive survey in 2021 identified a widely spread lithic scatter and large quantities of ground stone tools, concentrated around an area of approximately 40 m2. Initial excavations have uncovered semi-subterranean structures and in-situ boulder mortars. Amongst the chipped stone assemblage, analysis of seven fragments of obsidian tools from the survey and excavation point to two Anatolian sources (Nemrut and Bingöl A), expanding on the sparse data for the ninth millennium in this region. Previous investigations at Zarzi Cave have demonstrated long links to the obsidian source at Nemrut on Lake Van (Frahm & Tryon, 2018). The early results from our new excavations indicate that wide-reaching networks connected people in this region before sedentism and agriculture (Matthews et al., forthcoming).

Whereas Zarzi Cave and Zawi Chemi Rezan highlight early degrees of connectedness through lithic materials in the Zagros foothills, Sheikh-e Abad illustrates a combination of engagement and resistance to new materials and ideas. Located on a fertile plateau in the high Zagros (1,425 m asl), the inhabitants experimented with the management of plants and animals, constructed mud-brick houses, and shared a common use of symbolic displays with contemporary settlements in the region (Matthews et al., 2013b). Significantly, although these ideas and technologies drew on regional traditions, they were all executed using local resources, in the form of clay, bone, and stone, without substantial evidence for exchanged materials seen at contemporary lowland sites such as Nemrik 9 and Qermez Dere (Cole et al., 2013; Kozlowski, 1989; Watkins et al., 1989). The manner in which the occupants participated in regional networks appears to have been highly selective, well into the eighth millennium.

This characterisation is in stark contrast to the mid-eighth millennium site of Bestansur. Situated next to a perennial spring on the fertile Sharizor Plain (550 m asl), the site occupies a natural rise in the landscape, with evidence for Early Neolithic occupation and activities, spread over an area of four hectares. Excavations of the Neolithic deposits in and around the mound since 2012 have revealed architecture across all sectors dating to between 7800 and 7200 BC (Matthews et al., 2019). Recent investigations have focused on Trench 10, in the eastern flank of the mound, where there are successive layers of occupation at a neighbourhood scale, including a large building with the remains of dozens of individuals buried beneath the floors of a single room (Richardson et al., 2020). Burial practices are evident in the surrounding buildings, albeit on a smaller scale. From Bestansur, there is extensive evidence for engagement with local resources but also traces of wide-ranging networks. This includes materials such as obsidian, carnelian, and marine shells, as well as technologies and practices connected to the Fertile Crescent communities (Matthews et al., 2020c; Richardson, 2020).

The late eighth-millennium site of Shimshara was initially identified by Danish and Iraqi excavations in the 1950s and subsequently submerged by waters from the Dokan Dam (Mortensen, 1970). Located close to a strategic mountain pass on the Lesser Zab (515 m asl), the earliest settlement on a natural rise above the plain dates to around 7200 BC. Two rescue interventions including documenting exposed sections, intensive sampling, and excavation have been conducted (Matthews et al., 2020a), revealing evidence of a remarkably consistent set of materials and practices in operation, with high levels of obsidian brought from Anatolian sources. Adornments were made exclusively from marble and bone, both of which are locally sourced. The marble repertoire includes high proportions of finely crafted bracelets and bowls (Richardson, 2020). Although the site is clearly connected to obsidian networks and networks of knowledge to the north, there is little evidence for the more varied materials exchanges we see at other sites, or any significant indications of connection with sites to the east.

3 Analysing Neolithic Material Networks

The application of materials analysis to clay, stone, and shell objects can reveal resource use in local and regional landscapes and identify intersections between communities. The well-established practice of geochemical analysis of obsidians sheds light on one particular set of networks in operation, marine shells on another entirely, but through integrated approaches to the materials, complex relationships between shared materials, technologies, and ideas can be explored in greater detail. Through these interactions, we can begin to conceive the breadth and depth of the complex networks that connected Neolithic people across Southwest Asia. The prism of social network analysis facilitates a vision of communities selectively engaging with multi-layered and richly textured networks but also demonstrates the challenges of working with limited datasets in prehistoric communities. Examination of material networks in comparison with emerging evidence for genetic networks highlights the extent to which not just things but also people were mobile over vast landscapes.

3.1 Marine Shell Networks

In the Neolithic Zagros, beads were made from a broad range of materials, drawing on resources immediately available as well as those hundreds of kilometres away. Marine shell beads in this landlocked region were carried from the Mediterranean, the Red Sea, or the Persian Gulf. Cowries are distributed at sites along the Zagros flanks from the eighth millennium onwards, at Abdul Hosein, Ali Kosh, Chagha Sefid, and later as both shell and clay imitations of cowries at Choga Mami (Oates, 1969). Cowry imitation was also observed at Matarrah, where the locally abundant marble was used to imitate this popular form (Braidwood & Howe, 1960, pp. 36–37). Fossil sources are suggested to have been the source of shells found in deposits at Karim Shahir (Howe, 1983), although they also occur in conjunction with the marine shell Oliva at Jarmo (Moholy-Nagy, 1983).

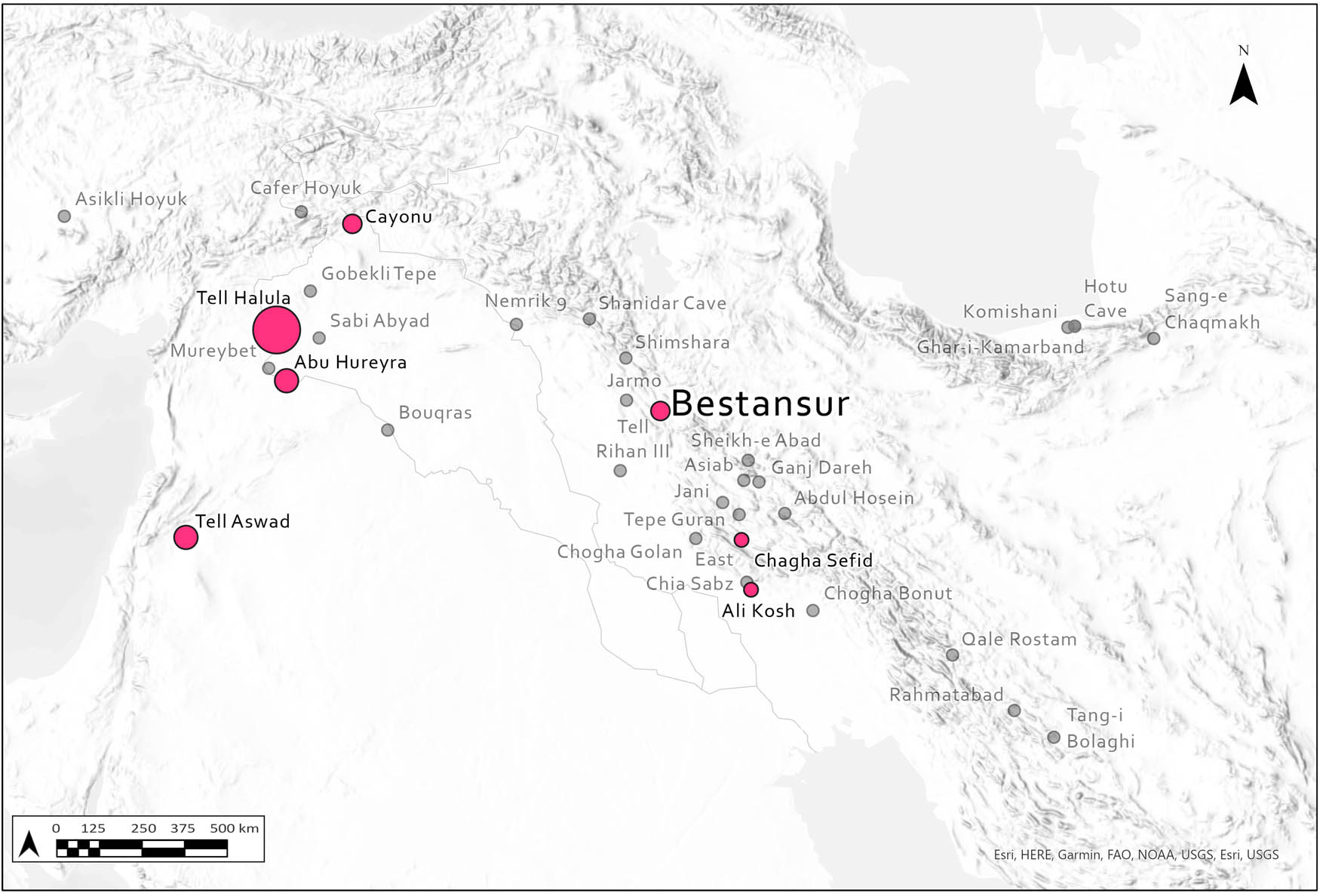

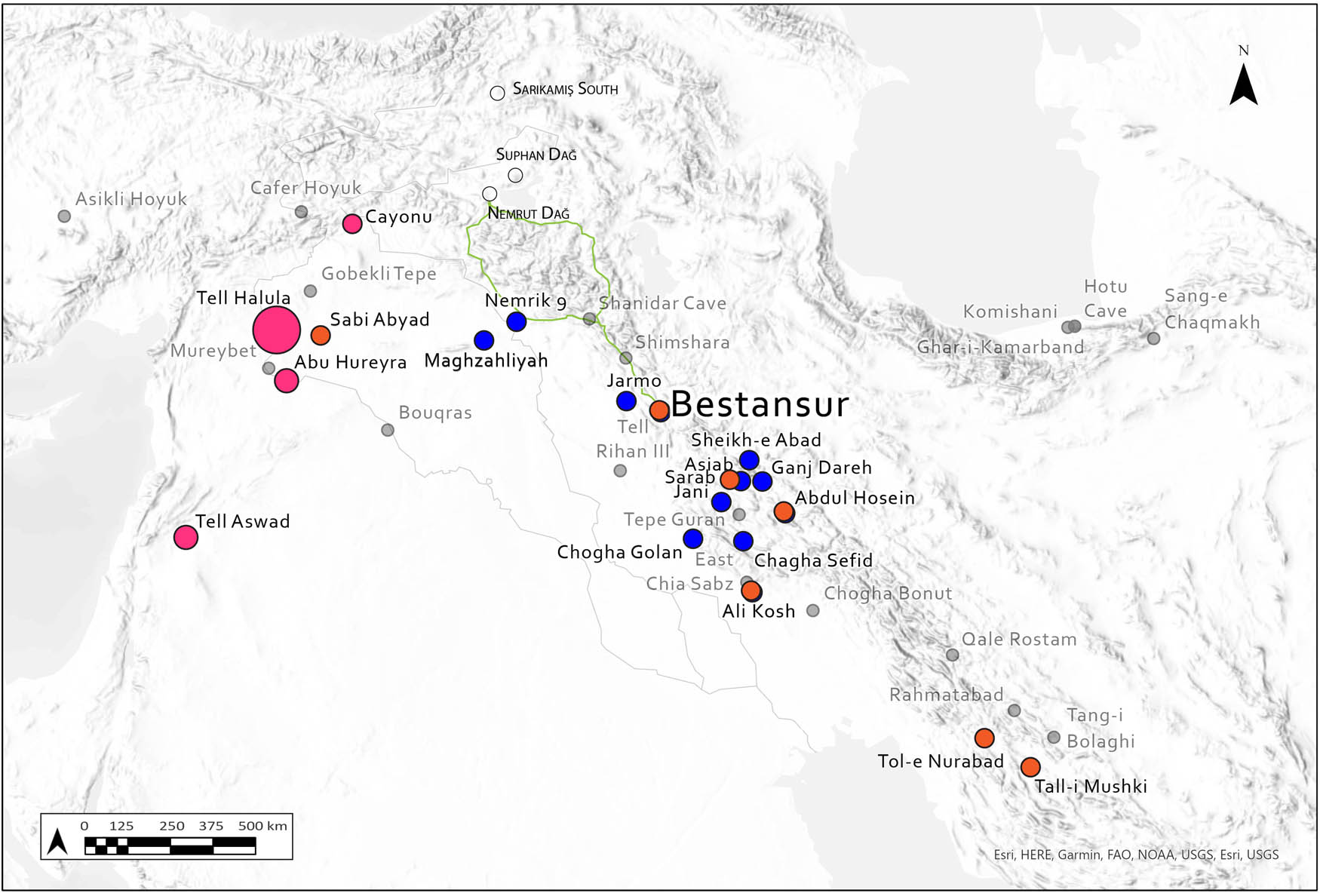

At Bestansur, hundreds of kilometres from the sea and the only one of our sites to include a marine-shell assemblage, we find cowries likely coming from the Red Sea (Figures 3 and 4). This was also the source for the majority of the assemblages at sites in Syria at Tell Aswad, Abu Hureyra, and Tell Halula (Alarashi, 2010; Alarashi et al., 2018), which may provide an indication of the routeways of exchange through which the cowries at Bestansur may have passed. Many of the cowries from Bestansur are found in association with burials. Each cowrie at Bestansur has the dorsum removed and is either packed with or bears traces of bitumen adhesive, which derives from a local source (Richardson, 2020). On the cowries, beneath the bitumen (and in some cases filled with it) is evidence for a previous use-life in the form of drilled perforations at the terminals, indicating that they were at one time strung or attached to garments. We know that cowries were strung as pelvic girdles and diadems at Tell Halula (Alarashi et al., 2018), although at Bestansur, the perforations were not used in these mortuary contexts. The Bestansur cowries may have been affixed using bitumen either to the faces of the dead (prior to decomposition of the flesh), or to materials that wrapped the dead. The cowries from Bestansur demonstrate cultural and material linkages with sites hundreds of kilometres to the west, linking to established mortuary practices but innovating in their execution and combining them with locally available materials. Scaphopod shells (also known as tusk shells or “dentalium”) have also been recovered from the burial contexts at Bestansur. The scaphopods are originally from marine sources, although the condition of the Bestansur examples suggests that these may have come from fossilised sources inland, as was observed at Karim Shahir (Howe, 1983, p. 48, 100).

Cowries with perforations and embedded with bitumen from Bestansur.

Distribution of cowries across Early Neolithic sites.

These marine species of shell were used in conjunction with local riverine molluscs at Bestansur, most prolifically nerites (Theodoxus jordani), which were perforated for stringing or sewing to fabrics. The scaphopods were found in similar contexts to local crab claws, which were also used as beads and may have deliberately imitated the form. Although shell beads are not an uncommon phenomenon at sites across the Central Zagros, the quantity of beads from mortuary and domestic contexts at Bestansur is exceptional and indicates a particularly rich practice in personal adornment that drew on local resources in combination with those acquired through material networks.

3.2 Clay Networks

From the Early Neolithic, people were employing clay for a wide range of purposes all across the Eastern Fertile Crescent. People were experimenting widely with shapes and establishing shared repertoires with neighbouring communities, blurring our conception of the definition between token and figurine. Some shapes spread far and wide, occurring commonly across the sites of Southwest Asia, forming a shared language that may have worked its way into counting practices (Schmandt-Besserat, 1979), whilst others appear intermittently spread between seemingly unrelated communities, possibly engaging in unrelated practices. Simple shapes were rolled and pinched in the form of clay “tokens”; small geometric shapes whose function at this stage is unclear (Bennison-Chapman, 2019). Clay shaped into cone, ball, disc, or rod shapes were identified in the Early Neolithic levels at M’lefaat, Nemrik 9, Karim Shahir, Asiab, and Sheikh-e Abad, each of which types spanned the breadth of Southwest Asia as far as the southern Levant (Kozlowski & Aurenche, 2005).

Made at a similar scale, and perhaps even for a similar purpose, small pieces of clay were given legs, or necks, or other human physical traits. These forms are most frequently distinguished from what would otherwise be classified as “tokens” by anthropomorphising details (such as bifurcation of the legs and protrusion of the breasts or buttocks) or through references to animal traits. Animals were most frequently depicted as quadrupeds, including at Bestansur, although the repertoire may also include bird-like figurines with pointed heads as seen at Karim Shahir (Howe, 1983). People were exchanging ideas and innovations in clay through common languages of portable objects, whilst developing and retaining localised practices.

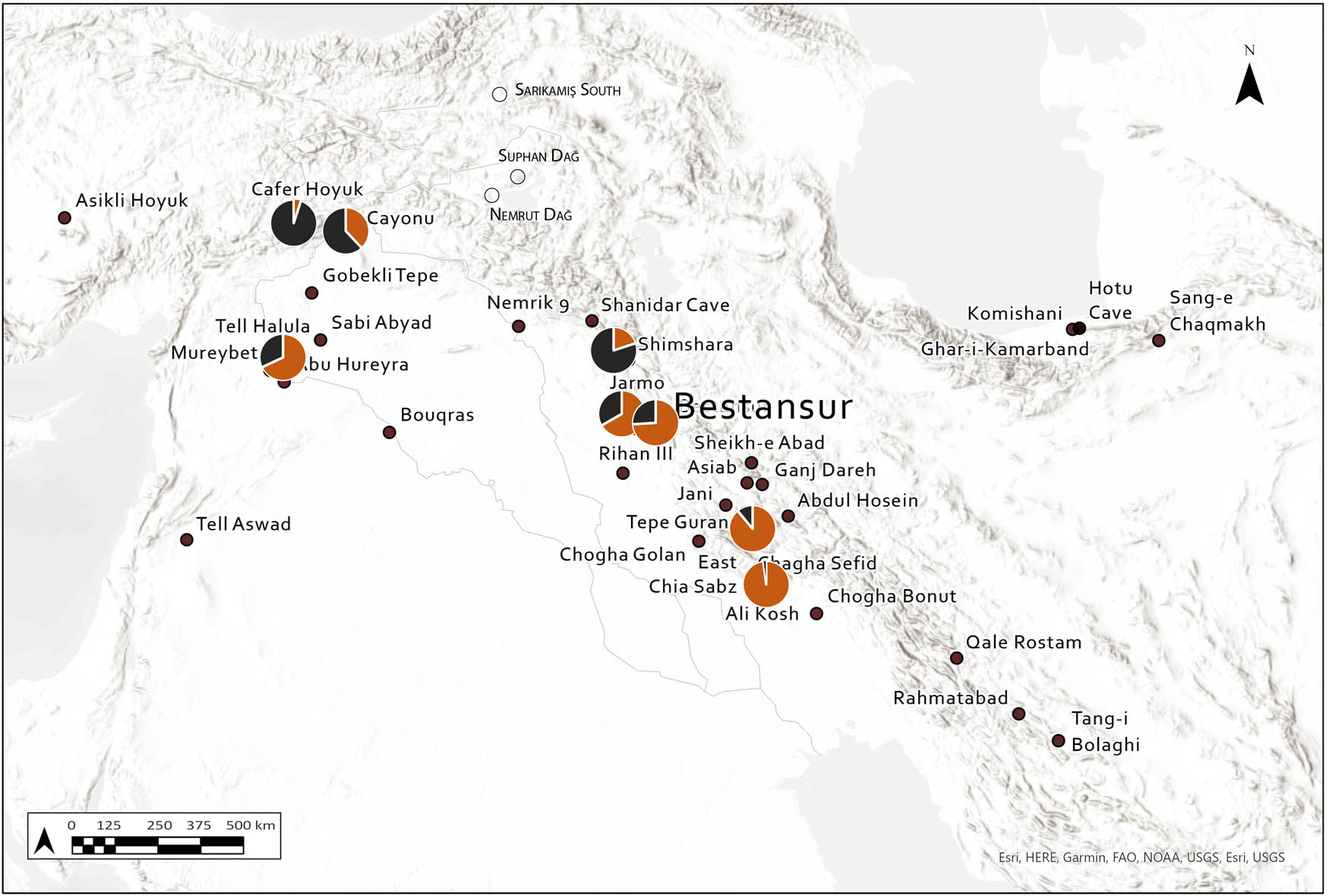

In the clay assemblage, there are distinctly different patterns of influence in technology and material used by the inhabitants of Bestansur, contrary to the westward interactions evident in the shell repertoire (Figure 5). In the shaping of mudbrick and tokens and simple-seated figurines from lightly baked local clays, Bestansur has a distinctly Zagros style (Matthews, 2020; Richardson, 2019), indicating knowledge networks that overlap with those sites in the high Zagros in Iran, such as Ganj Dareh and Sheikh-e Abad (Cole et al., 2013; Matthews et al., 2013a; Smith, 1990). Two clay objects in particular merit noting here (Figure 3): a gashed clay cone in a style that is peculiar to Ganj Dareh (Broman Morales & Smith, 1990) and a spool shape more commonly seen to the north and west prior to the eighth millennium (Kozlowski & Aurenche, 2005). Geochemical analysis confirms that both have been made with clay local to Bestansur (Richardson, 2020). A rare figurine recovered in 2021 appears to be skirted with possible fabric. Contrary to the Zagrosian style, similar linear decorations are present on figurines in the Levant, such as the example from Tell Aswad (Ayobi, 2014, fig. 6.1), but are otherwise unknown in the Eastern Fertile Crescent until some fifteen hundred years later at Sarab (Broman Morales, 1990, pp. 15g–h). This figurine appears to belong to a small group of conical clay objects at Bestansur with anthropomorphic traits, which show decorative references to traditions from both the east and the west.

Distribution of clay figurines and geometric objects in the “Zagrosian style”.

3.3 Adornment Networks

A range of minerals used for making beads and other adornments occur in the form of rich seams in the Zagros Mountains, amongst the ophiolite complexes, with serpentinites, quartz, chalcedony, and alabaster. The high number of broken blanks located at sites demonstrates a willingness to experiment with new materials, not limited to a proscribed aesthetic or source. Regardless of this abundant source, minerals for personal adornments were also transported from further afield, in the form of carnelian from the Alborz Mountains, the Persian Gulf, or Anatolia. Turquoise and variscite may also have come from a source in the Alborz Mountains to sites in the Central Zagros Mountains, appearing at Ali Kosh and, later, Jarmo (Moorey, 1994).

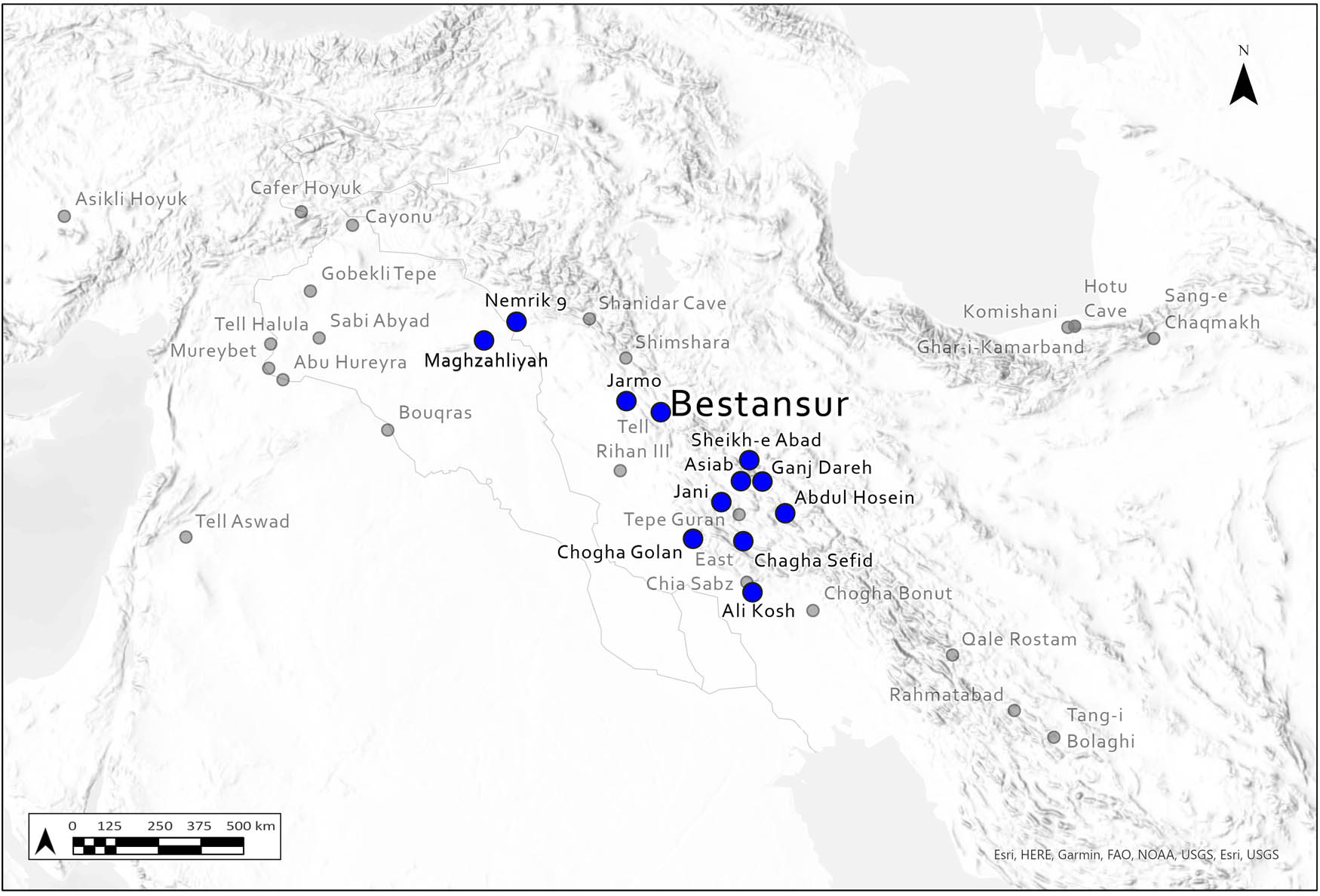

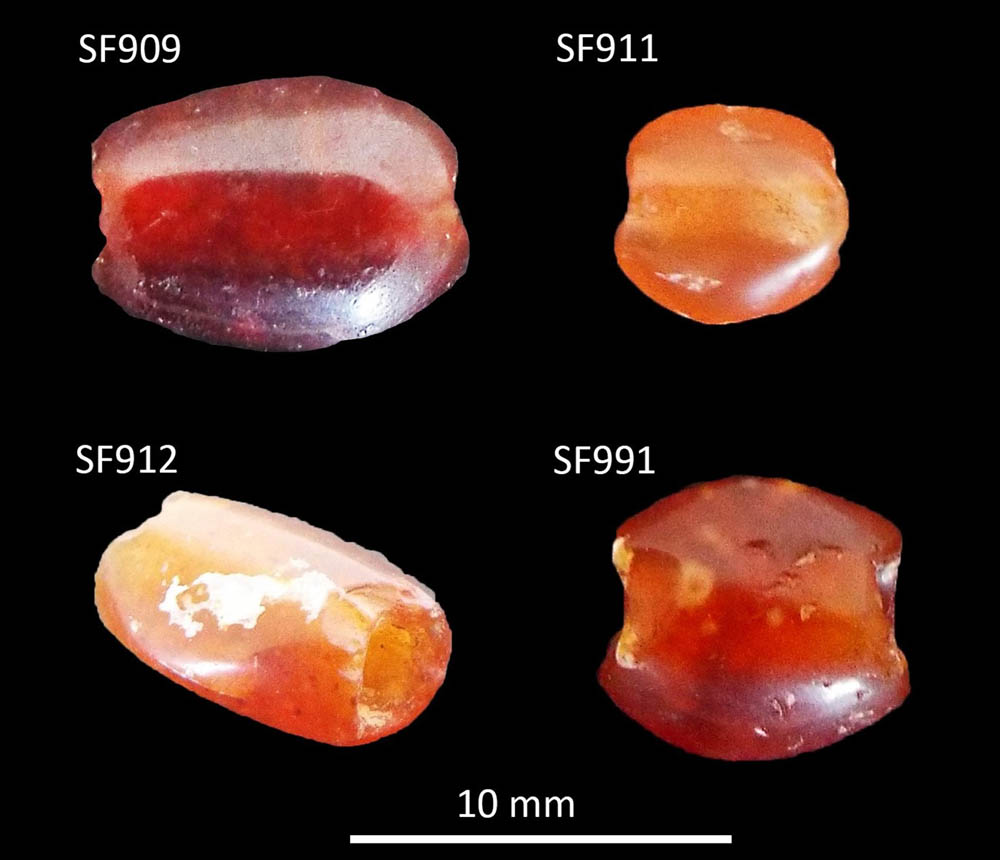

Half a dozen carnelian beads from Bestansur may come from several different sources (Figures 6 and 7). Five of these are highly polished in a “flat” or “tabular” shape found at other sites in the region (Kozlowski & Aurenche, 2005, fig. 5.1.1). Possible sources have been identified in central Anatolia, the Sinai Peninsula, and Iran (Alarashi, 2016; Beale, 1973). Analysis of the carnelian using pXRF suggests that these are from several chemically distinct sources and we see a similar variety of carnelians from Jarmo (Richardson, 2017), in a pattern of diverse sourcing similar to that identified at Early Neolithic sites in Cyprus (Moutsiou & Kassianidou, 2019). At Bestansur, we have no evidence for the working of carnelian on site and it is in all probability reaching the site as finished objects. Braidwood noted that casual contacts by nomadism or transhumance may have incorporated exchanges of materials over great distances (Braidwood et al., 1983, p. 290).

Carnelian beads from Bestansur.

Distribution of Neolithic carnelian beads.

At Bestansur, there is early evidence of body modification in the form of a piercing. A stone labret or spool was recovered from a burial dating to around 7500 BC. It was found resting on a skull at the top of the jaw, close to where the flesh of the ear would have been. The Bestansur stone labret appears to be a particularly early example for the Zagros (Figure 8), although Early Neolithic examples have been identified at Boncuklu Tarla in southeast Türkiye (Kodaş et al., 2024). Similar stone spools appear in eighth and seventh-millennium Fars with dental wear, and later figurines have been taken as evidence that these were worn in the lip (Alizadeh, 2021; Hole et al., 1969; Khanipour et al., 2021). However, the example from Bestansur was not found close to the lip, and analysis of the teeth did not find buccal wear that would correspond with labrets worn as lip piercings (Walsh, 2022).

Distribution of Neolithic spools and labrets.

3.4 Obsidian Networks

Since the first studies of Renfrew et al. (1966, 1969), obsidian across Southwest Asia has been scrutinised for patterns of long-distance trade and exchange. Geochemical analysis has provided evidence for the use of obsidian from the varying flows at Nemrut Dağ from the Palaeolithic to the Neolithic and beyond in the Eastern Fertile Crescent. Fragments of obsidian were found in Epipalaeolithic levels at Zarzi, Zawi Chemi Shanidar, Nemrik 9, and Qermez Dere, as well as occurring in Early Neolithic contexts at M’lefaat, Gird Chai (Howe, 1983) and at Zawi Chemi Rezan (Matthews et al., forthcoming). It becomes apparent that early settlements were, as Watkins et al. (1989) described, paradoxically both sedentarising and maintaining long-distance networks of interaction with the communities to the north, in modern Türkiye.

Over the course of the eighth millennium, obsidian reached almost all sites in the region, although in very small quantities in the high Iranian Zagros. The analysed obsidian at early eighth-millennium Chogha Golan and at East Chia Sabz in the late eighth millennium was transported exclusively from Nemrut sources (Darabi & Glascock, 2013; Zeidi & Conard, 2013). Analysis of the obsidians from Ali Kosh, Chagha Sefid, and Tepe Sabz has highlighted a transition from the exclusive use of Nemrut or Bingöl A obsidians in the early eighth millennium, to the use of obsidians from both Nemrut and Bingöl B by the late eighth millennium (Tonoike, 2012). Both the range of sources and the proportion of obsidian used expanded over time: the inhabitants of Jarmo increased their use of obsidian tools from a quarter of the chipped stone repertoire to half of all chipped stone usage (Hole, 1983).

Our Central Zagros sites fit within a framework of depleting obsidian proportions based on distance from the source along the southeast trajectory of the Zagros (Figure 9). At Bestansur, about 25% of the lithic assemblage is made from obsidian, the vast majority coming from the Lake Van Nemrut source, with only three fragments from alternative sources further north (Matthews et al., 2020c). At Shimshara, in contrast, 80% of tools recovered during our excavations were made from the volcanic material. Recent work on least-cost pathways has examined key routes that could have been utilised for the transmission of obsidian from sources and between sites (Barge et al., 2018), although the focus on the obsidian alone greatly underestimates the connectedness of the inhabitants of Bestansur.

Proportions of obsidian (black) versus chert (orange).

Geochemical analysis using portable X-ray fluorescence applied to sites in the Kurdish regions of Iraq and Iran from the Epipaleolithic to the Chalcolithic has demonstrated chronological shifts in the acquisition and transmission of obsidians from a number of sources (Catanzariti et al., 2023). There is a strong emphasis on Nemrut obsidian used for tools at Central Zagros sites that lasts from the Epipalaeolithic to the Late Chalcolithic, with half a dozen sources episodically contributing to the obsidian in circulation. This includes material from as far north as Armenia reaching Bestansur and as far west as Bingöl B in use at Shimshara.

Analysis of the chipped stone tools from both the sites of Bestansur and Shimshara has highlighted a transitional difference in the use of obsidian along this network (Matthews et al., 2020c). From both sites, residues are present on the working edges of so-called “Çayönü” tools, including the presence of sulphur and calcite, indicating they may have been used for working alabaster and marble bowls and bracelets (Matthews et al., 2020c). However, there is a pivotal difference in the working of the tools indicating that Bestansur and Shimshara, although only 100 km apart, sit on either side of two observed working traditions (Fujii, 1988). At Shimshara, in keeping with Anatolian tools of this type, the steep retouch is focused on the dorsal face, with grinding striations on the ventral, whilst the opposite is true of the Çayönü tools at Bestansur in keeping with Zagros practices. Consequently, we can identify multi-layered and innovative practices within the obsidian assemblage.

4 Multi-Layered Networks in the Neolithic Central Zagros

These examples demonstrate varied and extensive networks that span long periods and hundreds of kilometres. By bringing together multiple material strands, it is possible to begin to construct a nuanced understanding of the complex and multi-layered networks with which the Neolithic communities of the Central Zagros engaged. From only these few examples, it is possible to demonstrate that obsidian, although the most numerously exchanged material, only accounts for one portion of the networks in which the communities of the Central Zagros were involved. Through integrating data across materials that might otherwise be divided between disciplinary silos, it is possible to shed light on the multi-directional networks, composed of agents who participated in a variety of ways. If we bring together the data for some of the most commonly occurring materials such as clay, stone tools, marine shells, and adornments, it is possible to explore the role of individual sites in the sharing of material and technological knowledge (Figure 10). Further integration of other key materials, such as bone tools, adhesives, and plasters, will only increase the resolution of integrated analyses (Matthews et al., forthcoming).

Intersecting networks of clay, cowries, and carnelian.

Bestansur sits nestled between the highland sites to the south and lowland sites to the north, with material evidence to demonstrate a connection to the networks of both. In applying a socio-material network approach to the adornments constructed from all materials at Bestansur, we can begin to consider the possibility that Bestansur played a pivotal role in regional networks of exchange. Through constructing a weighted one-mode regional network of shared material culture characteristics, based on the presence/absence of shared raw material types and object characteristics, including published assemblages from Early Neolithic sites in the region, we can visualise central nodes within the network (Figure 11). Few Early Neolithic sites have been extensively excavated in the region, particularly in the Central Zagros, and the network represented here must have included many intermediaries. Further, the sites do not all fit the same chronological scope and the broad temporal scale spanning at least two millennia should be considered here. However, based on this approach, it remains clear that Bestansur was an intensely connected site, engaging with wide networks and perhaps even acting as a conduit between sites, in particular at the intersection between the sites on the plains to the northwest and the plateaus of the Zagros Mountains to the southeast.

Social networks analysis of material culture bonds between key sites in the Central Zagros (Gephi).

Furthermore, it illustrates the isolation of sites such as Shimshara, which appears to have participated in a limited and selective way with regional networks, in spite of the high proportions of obsidian present in the assemblage.

The initial results from the DNA analysis of four individuals buried at Bestansur have indicated that the diversity identified in material and knowledge exchange may also be represented in the genetic makeup of the population (Lazaridis et al., 2022). These individuals represent a small sample from an extensive mortuary assemblage at Bestansur providing new insights into a network of pan-regional contacts between early farming communities that corresponds with the material evidence for interactions between the inhabitants of Bestansur and networks that extended along a trajectory to the southeast and northwest.

The connections and rich material culture at Bestansur, in particular, provided a fertile ground for innovation and creativity. Exposure to and engagement with a wide range of materials, concepts, and technologies laid the groundwork for new cognitive scaffolding that formed the basis for the development of complex societies. This blending of brain, body, and world has been explored in relation to prehistoric sites such as the Neolithic community at WF16 (Mithen, 2010) and in Iron Age Britain (Gosden, 2008). Three key strands should be considered here: material culture as a scaffold for distributed cognition (Dunbar et al., 2010; Gamble et al., 2014), the evolution of social and material networks (Coward & Gamble, 2010; Coward, 2013; Knappett, 2011, 2013), and how material engagements have shaped the mind (Malafouris, 2013; Malafouris et al., 2014; Renfrew, 2004, 2007). Material Engagement Theory (Malafouris, 2013; Renfrew, 2004) has made the argument that the capacity for understanding comes as a product of interactions between people and things, situated in space and time. These approaches have highlighted the key role that interactions with material worlds have played in our cognition, drawing together the biological, social, and material spheres of analysis. In early sedentarising communities, in a rootedness in one place – such as at Bestansur – people found new properties, materials, and ways of engaging with the physical world, and so-doing fettered themselves to its materiality, to its rhythms, forging entangled, inextricable, enabling, ever-changing webs of things and people.

By engaging with new materials and concepts through communication with other communities, the people of Neolithic Bestansur developed their own capacities for creating new ways of living, communicating, and interpreting the world around them. Through interaction with multiple networks that spanned Southwest Asia, this small community drew from elements of each, creatively employing and reinterpreting material resources and technologies. Bestansur is just one example of the many Early Neolithic communities collectively engaging with material networks, but it provides insight into interactions at an axial point in the landscape where the Northern Fertile Crescent meets the Central Zagros and a community that chose to bridge between the two.

Acknowledgements

This research was conducted under the remit of the ERC-funded MENTICA project (the Middle East Neolithic Transition: Integrated Community Approaches), led by Roger Matthews. The project aims to examine the ways in which communities (on the local and trans-regional scale) engaged with “Neolithic” ways of living, as well as working with modern communities to support heritage and cultural rights. Excavations and research have been conducted with kind permission from and in collaboration with the Directorate for Antiquities and Heritage, Sulaimaniyah, the Slemani Museum, the Directorate General of Antiquities and Heritage, Erbil, and the Kurdistan Regional Government.

-

Funding information: This research and its underlying data have been generously supported by the European Research Council (grant no. 787264), the Arts and Humanities Research Council (grant no. AH/H034315/2), the Gerald Averay Wainwright Fund (University of Oxford), National Geographic, the British Academy, the British Institute for the Study of Iraq, and the British Institute of Persian Studies. The Open Access status of this article has received funding from the Centre of Excellence in Ancient Near Eastern Empires (ANEE), funded by the Research Council of Finland (decision number 352748).

-

Author contributions: The author confirms the sole responsibility for the conception of the study, presented results, and manuscript preparation.

-

Conflict of interest: The author states no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: Data for the excavations between 2012 and 2017 are available at the Archaeology Data Service: https://doi.org/10.5284/1090506.

References

Alarashi, H. (2010). Shell beads in the pre-pottery Neolithic B in central levant: Cypraeidae of Tell Aswad (Damascus, Syria). In E. Alvarez-Fernandez & D. Carvajal-Contreras (Eds.), Not only food: Marine, terrestrial and freshwater molluscs in archaeological sites. Proceedings of the 2nd meeting of the ICAZ Archaeomalacology Working Group (Santander, February 19th-22nd 2008) (pp. 88–98). Aranzadi Zientzia Elkartea.Suche in Google Scholar

Alarashi, H. (2016). Butterfly beads in the Neolithic Near East: Evolution, technology and socio-cultural implications. Cambridge Archaeological Journal, 26(3), 493–512. doi: 10.1017/S0959774316000342.Suche in Google Scholar

Alarashi, H., Ortiz, A., & Molist, M. (2018). Sea shells on the riverside: Cowrie ornaments from the PPNB site of Tell Halula (Euphrates, northern Syria). Quaternary International, 490, 98–112. doi: 10.1016/j.quaint.2018.05.004.Suche in Google Scholar

Alizadeh, A. (2021). Review and synthesis of the Early Neolithic cultural development in Fars, Southern Iran. Journal of Neolithic Archaeology, 23, 1–27. doi: 10.12766/jna.2021.1.Suche in Google Scholar

Asouti, E. (2006). Beyond the pre-pottery Neolithic B interaction sphere. Journal of World Prehistory, 20(2–4), 87–126. doi: 10.1007/s10963-007-9008-1.Suche in Google Scholar

Ayobi, R. (2014). Les objets en terre du Levant néolithique avant l’invention de la céramique: Cuisson intentionnelle ou accidentelle? Syria, 91, 7–34. doi: 10.4000/syria.2608.Suche in Google Scholar

Bar-Yosef, O. (2002). The Natufian culture and the Early Neolithic: Social and economic trends in Southwest Asia. In P. Bellwood & C. Renfrew (Eds.), Examining the farming/language dispersal hypothesis (pp. 113–126). MacDonald Institute for Archaeological Research.Suche in Google Scholar

Bar-Yosef, O., & Belfer-Cohen, A. (1989). The Levantine ‘PPNB’ interaction sphere. In I. Hershkovitz (Ed.), People and culture in change. Proceedings of the Second Symposium on Upper Palaeolithic, Mesolithic and Neolithic Populations of Europe and the Mediterranean Basin (pp. 59–72). Archaeopress.Suche in Google Scholar

Barge, O., Azizi Kharanaghi, H., Biglari, F., Moradi, B., Mashkour, M., Tengberg, M., & Chataigner, C. (2018). Diffusion of Anatolian and Caucasian obsidian in the Zagros Mountains and the highlands of Iran: Elements of explanation in ‘least cost path’ models. Quaternary International, 467, 297–322. doi: 10.1016/j.quaint.2018.01.032.Suche in Google Scholar

Beale, T. W. (1973). Early trade in highland Iran: A view from a source area. World Archaeology, 5(2), 133–148. http://www.jstor.org/stable/123983.10.1080/00438243.1973.9979561Suche in Google Scholar

Bennison-Chapman, L. E. (2019). Reconsidering ‘tokens’: The Neolithic origins of accounting or multifunctional, utilitarian tools? Cambridge Archaeological Journal, 29(2), 233–259. doi: 10.1017/s0959774318000513.Suche in Google Scholar

Braidwood, L. S., Braidwood, R. J., Howe, B., Reed, C. A., & Watson, P. J. (Eds.). (1983). Prehistoric archeology along the Zagros flanks (Vol. 105). The Oriental Institute.Suche in Google Scholar

Braidwood, R. J., & Howe, B. (1960). Prehistoric investigations in Iraqi Kurdistan. University of Chicago Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Broman Morales, V. (1990). Figurines and other clay objects from Sarab and Çayönü. University of Chicago.Suche in Google Scholar

Broman Morales, V., & Smith, P. E. L. (1990). Gashed clay cones at Ganj Dareh, Iran. Paléorient, 16, 115–117.10.3406/paleo.1990.4525Suche in Google Scholar

Catanzariti, A., Tanaka, T., & Richardson, A. (2023). Results from the 2018 and 2019 excavation seasons at Ban Qala, Iraqi Kurdistan. In N. Marchetti, F. Cavaliere, E. Cirelli, C. D’Orazio, G. Giacosa, M. Guidetti, & E. Mariani (Eds.), Proceedings of the 12th International Congress on the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East, 06-09 April 2021, Bologna. Vol. 2: Field Reports (pp. 129–142). Harrassowitz.10.13173/9783447119030.129Suche in Google Scholar

Cole, G., Matthews, R., & Richardson, A. (2013). Material networks of the Neolithic at Sheikh-e Abad: Objects of bone, stone and clay. In R. Matthews, W. Matthews, & Y. Mohammadifar (Eds.), The earliest Neolithic of Iran: 2008 excavations at Sheikh-e Abad and Jani (pp. 135–145). Oxbow Books.10.2307/j.ctvh1dwnk.17Suche in Google Scholar

Coward, F. (2010). Small worlds, material culture and ancient Near Eastern social networks. In R. Dunbar, C. Gamble, & J. Gowlett (Eds.), Social brain, distributed mind (pp. 448–479). Oxford University Press.10.5871/bacad/9780197264522.003.0021Suche in Google Scholar

Coward, F. (2013). Grounding the net: Social networks, material culture and geography in the Epipalaeolithic and Early Neolithic of the Near East (∼21,000–6,000 cal BCE). In C. Knappett (Ed.), Network analysis in archaeology: New approaches to regional interaction (pp. 247–280). Oxford University Press.10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199697090.003.0011Suche in Google Scholar

Coward, F. & Gamble, C. (2010). Metaphor and materiality in earliest prehistory. In L. Malafouris & C. Gamble (Eds.), The cognitive life of things (pp. 47–58). McDonald Institute of Archaeological Research.Suche in Google Scholar

Coward, F., & Howard-Jones, P. (2021). Exploring environmental influences on infant development and their potential role in processes of cultural transmission and long-term technological change. Childhood in the Past, 14(2), 80–101. doi: 10.1080/17585716.2021.1956057.Suche in Google Scholar

Darabi, H., & Glascock, M. D. (2013). The source of obsidian artefacts found at East Chia Sabz, Western Iran. Journal of Archaeological Science, 40(10), 3804–3809. doi: 10.1016/j.jas.2013.04.022.Suche in Google Scholar

Dietrich, O., Heun, M., Notroff, J., Schmidt, K., & Zarnkow, M. (2012). The role of cult and feasting in the emergence of Neolithic communities. New evidence from Göbekli Tepe, south-eastern Turkey. Antiquity, 86(333), 674–695. doi: 10.1017/S0003598X00047840.Suche in Google Scholar

Dunbar, R. (1993). Co-evolution of neocortical size, group size and language in humans. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 16, 681–735.10.1017/S0140525X00032325Suche in Google Scholar

Dunbar, R. (2008). Cognitive constraints on the structure and dynamics of social networks. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice, 12, 7–16.10.1037/1089-2699.12.1.7Suche in Google Scholar

Dunbar, R., Gamble, C. & Gowlett, J. (Eds.). (2010). Social brain, distributed mind. Oxford University Press.10.5871/bacad/9780197264522.001.0001Suche in Google Scholar

Fazeli, N., Oller, M., Wu, J., Wu, Z., Tenenbaum, J. B., & Rodriguez, A. (2019). See, feel, act: Hierarchical learning for complex manipulation skills with multisensory fusion. Science Robotics, 4(26), eaav3123. doi: 10.1126/scirobotics.aav3123.Suche in Google Scholar

Frahm, E., & Tryon, C. A. (2018). Origins of Epipalaeolithic obsidian artifacts from Garrod’s excavations at Zarzi Cave in the Zagros foothills of Iraq. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, 21, 472–485. doi: 10.1016/j.jasrep.2018.08.001.Suche in Google Scholar

Fujii, S. (1988). Typological reassessment and some discussions on “beaked blades”. Bulletin of the Okayama Orient Museum, 7, 1–16.Suche in Google Scholar

Gamble, C., Gowlett, J. & Dunbar, R. (2014). Thinking big: How the evolution of social life shaped the human mind. Thames & Hudson.Suche in Google Scholar

Garrod, D. (1930). The Palaeolithic of Southern Kurdistan: Excavations in the caves of Zarzi and Hazar Merd. American School of Prehistoric Research Bulletin, 6, 9–43.Suche in Google Scholar

Gosden, C. 2008. Social ontologies. Philosophical Transactions: Biological Sciences, 363(1499), 2003–2010.10.1098/rstb.2008.0013Suche in Google Scholar

Gowlett, J., Gamble, C., & Dunbar, R. (2012). Human evolution and the archaeology of the social brain. Current Anthropology, 53(6), 693–722. doi: 10.1086/667994.Suche in Google Scholar

Graeber, D., & Wengrow, D. (2022). The dawn of everything. A new history of humanity. Penguin.Suche in Google Scholar

Hodder, I. (2012). Entangled: An archaeology of the relationships Between Humans and Things. Wiley-Blackwell.10.1002/9781118241912Suche in Google Scholar

Hole, F. (1983). The Jarmo chipped stone. In L. S. Braidwood, R. J. Braidwood, B. Howe, C. A. Reed, & P. J. Watson (Eds.), Prehistoric archeology along the Zagros flanks (pp. 233–284). Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago.Suche in Google Scholar

Hole, F. (1996). A Syrian bridge between the Levant and the Zagros? In S. K. Kozłowski & H. G. Gebel (Eds.), Neolithic chipped stone industries of the Fertile Crescent and their contemporaries in adjacent regions: Proceedings of the Second Workshop on PPN Chipped Lithic Industries, Institute of Archaeology, Warsaw University, 3rd-7th April 1995 (pp. 5–14). Ex Oriente.Suche in Google Scholar

Hole, F., Flannery, K. V., & Neely, J. A. (1969). Prehistory and human ecology of the Deh Luran Plain. University of Michigan Press.10.3998/mpub.11395036Suche in Google Scholar

Howe, B. (1983). Karim Shahir. In L. S. Braidwood, R. J. Braidwood, B. Howe, C. A. Reed, & P. J. Watson (Eds.), Prehistoric archeology along the Zagros flanks (pp. 23–154). Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago.Suche in Google Scholar

Khanipour, M., Niknami, K., & Abe, M. (2021). Challenges of the Fars Neolithic chronology: An appraisal. Radiocarbon, 63(2), 693–712. doi: 10.1017/RDC.2020.113.Suche in Google Scholar

Knappett, C. (2011). An archaeology of interaction: Network perspectives on material culture and society. Oxford University Press.10.1093/acprof:osobl/9780199215454.001.0001Suche in Google Scholar

Knappett, C. (Ed.). (2013). Network analysis in archaeology: New approaches to regional interaction. Oxford University Press.10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199697090.001.0001Suche in Google Scholar

Kodaş, E., Baysal, E. L., & Özkan, K. (2024). Bodily boundaries transgressed: Corporal alteration through ornamentation in the Pre-Pottery Neolithic at Boncuklu Tarla, Türkiye. Antiquity, 98(398), 323–342 doi: 10.15184/aqy.2024.28.Suche in Google Scholar

Kozlowski, S. K. (1989). Nemrik 9, a PPN Neolithic site in Northern Iraq. Paléorient, 15(1), 25–31.10.3406/paleo.1989.4482Suche in Google Scholar

Kozlowski, S. K., & Aurenche, O. (2005). Territories, boundaries and cultures in the Neolithic Near East. Archaeopress.10.30861/9781841718071Suche in Google Scholar

Lazaridis, I., Alpaslan-Roodenberg, S., Acar, A., Açıkkol, A., Agelarakis, A., Aghikyan, L., Akyüz, U., Andreeva, D., Andrijašević, G., Antonović, D., Armit, I., Atmaca, A., Avetisyan, P., Aytek, A., Bacvarov, K., Badalyan, R., Bakardzhiev, S., Balen, J., Bejko, L., … Reich, D. (2022). Ancient DNA from Mesopotamia suggests distinct pre-pottery and pottery Neolithic migrations into Anatolia. Science, 377(6609), 982–987. doi: 10.1126/science.abq0762.Suche in Google Scholar

Maddux, W. W., & Galinsky, A. D. (2009). Cultural borders and mental barriers: The relationship between living abroad and creativity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 96(5), 1047–1061. doi: 10.1037/a0014861.Suche in Google Scholar

Malafouris, L. (2013). How things shape the mind: A theory of material engagement. MIT Press.10.7551/mitpress/9476.001.0001Suche in Google Scholar

Malafouris, L., Gosden, C. & Overmann, K. A. (2014). Creativity, cognition, and material culture: An introduction. Pragmatics & Cognition, 22(1), 1–4.10.1075/pc.22.1.001inSuche in Google Scholar

Matthews, W. (2020). Sustainability of early sedentary agricultural communities: New insights from high-resolution microstratigraphic and micromorphological analyses. In R. Matthews, W. Matthews, K. Rasheed Raheem, & A. Richardson (Eds.), The early Neolithic of the Eastern Fertile Crescent: Excavations at Bestansur and Shimshara, Iraqi Kurdistan (pp. 197–264). Oxbow.10.2307/j.ctv2npq9gd.16Suche in Google Scholar

Matthews, R., Matthews, W., & Mohammadifar, Y. (Eds.). (2013b). The earliest Neolithic of Iran: 2008 excavations at Sheikh-e Abad and Jani. British Institute of Persian Studies, Oxbow.10.2307/j.ctvh1dwnkSuche in Google Scholar

Matthews, W., Matthews, R., Raeuf Aziz, K., & Richardson, A. (2020a). Excavations and contextual analyses: Shimshara. In R. Matthews, W. Matthews, K. Rasheed Raheem, & A. Richardson (Eds.), The early Neolithic of the Eastern Fertile Crescent: Excavations at Bestansur and Shimshara, Iraqi Kurdistan (pp. 177–186). Oxbow.10.2307/j.ctv2npq9gd.14Suche in Google Scholar

Matthews, R., Matthews, W., Raeuf Aziz, K. & Richardson, A. (Eds.). (forthcoming). The Epipalaeolithic-Early Neolithic transition in the Eastern Fertile Crescent, ca. 12,000-7000 BCE: Inter-disciplinary research at Zarzi, Zawi Chemi Rezan, and Bestansur, Iraqi Kurdistan. Oxbow.Suche in Google Scholar

Matthews, R., Matthews, W., Rasheed Raheem, K., & Richardson, A. (Eds.). (2020d). The early Neolithic of the Eastern Fertile Crescent: Excavations at Bestansur and Shimshara, Iraqi Kurdistan. Oxbow.10.2307/j.ctv2npq9gdSuche in Google Scholar

Matthews, R., Matthews, W., Richardson, A., & Raeuf Aziz, K. (2020b). Intensive field survey in the Zarzi Region. In R. Matthews, W. Matthews, K. Rasheed Raheem, & A. Richardson (Eds.), The early Neolithic of the Eastern Fertile Crescent: Excavations at Bestansur and Shimshara, Iraqi Kurdistan (pp. 43–56). Oxbow.10.2307/j.ctv2npq9gd.8Suche in Google Scholar

Matthews, R., Matthews, W., Richardson, A., Rashid Raheem, K., Walsh, S., Raeuf Aziz, K., Bendrey, R., Whitlam, J., Charles, M., Bogaard, A., Iversen, I., Mudd, D., & Elliott, S. (2019). The early Neolithic of Iraqi Kurdistan: Current research at Bestansur, Shahrizor Plain. Paléorient, 45(2), 13–32.10.4000/paleorient.644Suche in Google Scholar

Matthews, R., Richardson, A., & Maeda, O. (2020c). Early Neolithic chipped stone worlds of Bestansur and Shimshara. In R. Matthews, W. Matthews, K. Rasheed Raheem, & A. Richardson (Eds.), The early Neolithic of the Eastern Fertile Crescent: Excavations at Bestansur and Shimshara, Iraqi Kurdistan (pp. 461–532). Oxbow.10.2307/j.ctv2npq9gd.24Suche in Google Scholar

Matthews, W., Shillito, L. M., & Elliott, S. (2013a). Investigating early Neolithic materials, ecology and sedentism: Micromorphology and microstratigraphy. In R. Matthews, W. Matthews, & Y. Mohammadifar (Eds.), The earliest Neolithic of Iran. 2008 Excavations at Sheikh-e Abad and Jani (pp. 67–104). Oxbow Books.10.2307/j.ctvh1dwnk.13Suche in Google Scholar

Mazzucato, C. (2019). Socio-material archaeological networks at Çatalhöyük: A community detection approach. Frontiers in Digital Humanities, 6(8), 1–25. doi: 10.3389/fdigh.2019.00008.Suche in Google Scholar

Mithen, S. (2010). Excavating the Prehistoric mind: The brain as a cultural artefact and material culture as biological extension. In R. Dunbar, C. Gamble, & J. Gowlett (Eds.), Social brain, distributed mind (pp. 481–503). Oxford University Press.10.5871/bacad/9780197264522.003.0022Suche in Google Scholar

Mithen, S. (2020). Lost for words: An extraordinary structure at the early Neolithic settlement of WF16. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 7(1), 125. doi: 10.1057/s41599-020-00615-7.Suche in Google Scholar

Mithen, S., Richardson, A., & Finlayson, B. (2023). The flow of ideas: Shared symbolism between WF16 in the south and Göbekli Tepe in the north during Neolithic emergence in SW Asia. Antiquity, 97(394), 829–849.10.15184/aqy.2023.67Suche in Google Scholar

Mnih, V., Kavukcuoglu, K., Silver, D., Rusu, A. A., Veness, J., Bellemare, M. G., Graves, A., Riedmiller, M., Fidjeland, A. K., Ostrovski, G., Petersen, S., Beattie, C., Sadik, A., Antonoglou, I., King, H., Kumaran, D., Wierstra, D., Legg, S., & Hassabis, D. (2015). Human-level control through deep reinforcement learning. Nature, 518(7540), 529–533. doi: 10.1038/nature14236.Suche in Google Scholar

Moholy-Nagy, H. (1983). Jarmo artifacts of pecked and ground stone and shell. In L. S. Braidwood, R. J. Braidwood, B. Howe, C. A. Reed, & P. J. Watson (Eds.), Prehistoric archeology along the Zagros flanks (pp. 289–346). Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago.Suche in Google Scholar

Moorey, P. R. S. (1994). Ancient Mesopotamian materials and industries. The Archaeological Evidence. Clarendon Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Mortensen, P. (1970). Tell Shimshara: The Hassuna period. Det Kongelige Danske Videnskabernes Selskab.Suche in Google Scholar

Moutsiou, T., & Kassianidou, V. (2019). Geochemical characterisation of carnelian beads from aceramic Neolithic Cyprus using portable X-ray Fluorescence Spectrometry (pXRF). Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, 25, 257–265. doi: 10.1016/j.jasrep.2019.04.013.Suche in Google Scholar

Nature Iraq. (2017). Key biodiversity areas of Iraq: Priority sites for conservation & protection. Tablet House Publishing.Suche in Google Scholar

Oates, J. (1969). Choga Mami, 1967-68: A preliminary report. Iraq, 31(2), 115–152.10.2307/4199877Suche in Google Scholar

Olszewski, D. (2012). The Zarzian in the context of the Epipaleolithic Middle East. International Journal of Humanities, 19(3), 1–20.Suche in Google Scholar

Pollock, S., Bernbeck, R., & Abdi, K. (Eds.). (2010). The 2003 excavations at Tol-e Basi, Iran: Social life in a Neolithic village. Verlag Philipp von Zabern.Suche in Google Scholar

Renfrew, C. (2004). Towards a theory of material engagement. In E. DeMarrais, C. Gosden & C. Renfrew (Eds.). Rethinking materiality: The engagement of mind with the material world (pp. 23–32). McDonald Institute of Archaeological Research.Suche in Google Scholar

Renfrew, C. (2007). Prehistory: The making of the human mind. Phoenix.Suche in Google Scholar

Renfrew, C., Dixon, J. E., & Cann, J. R. (1966). Obsidian and early cultural contact in the Near East. Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society, 32, 30–72.10.1017/S0079497X0001433XSuche in Google Scholar

Renfrew, C., Dixon, J. E., & Cann, J. R. (1969). Further analysis of Near Eastern obsidians. Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society, 34, 319–331.10.1017/S0079497X0001392XSuche in Google Scholar

Richardson, A. (2017). Neolithic materials and materiality in the foothills of the Zagros Mountains. In T. Pereira, X. Terradas, & N. Bicho (Eds.), The exploitation of raw materials in Prehistory: Sourcing, processing and distribution. Cambridge Scholars.Suche in Google Scholar

Richardson, A. (2019). Pre-pottery clay innovation in the Zagros foothills. Oxford Journal of Archaeology, 38(1), 2–17. doi: 10.1111/ojoa.12155.Suche in Google Scholar

Richardson, A. (2020). Material culture and networks of Bestansur and Shimshara. In R. Matthews, W. Matthews, K. Rasheed Raheem, & A. Richardson (Eds.), The early Neolithic of the Eastern Fertile Crescent: Excavations at Bestansur and Shimshara, Iraqi Kurdistan (pp. 533–612). Oxbow.10.2307/j.ctv2npq9gd.25Suche in Google Scholar

Richardson, A., Matthews, R., Matthews, W., Raeuf Aziz, K., & Stone, A. (2020). Excavations and contextual analyses: Bestansur. In R. Matthews, W. Matthews, K. Rasheed Raheem, & A. Richardson (Eds.), The early Neolithic of the Eastern Fertile Crescent: Excavations at Bestansur and Shimshara, Iraqi Kurdistan (pp. 115–176). Oxbow.10.2307/j.ctv2npq9gd.13Suche in Google Scholar

Richter, T., Garrard, A. N., Allock, S., & Maher, L. A. (2011). Interaction before agriculture: Exchanging material and sharing knowledge in the Final Pleistocene Levant. Cambridge Archaeological Journal, 21, 95–114. doi: 10.1017/s0959774311000060.Suche in Google Scholar

Schmandt-Besserat, D. (1979). Reckoning before writing. Archaeology, 32, 22–31.Suche in Google Scholar

Smith, P. E. L. (1990). Architectural innovation and experimentation at Ganj Dareh, Iran. World Archaeology, 21(3), 323–335.10.1080/00438243.1990.9980111Suche in Google Scholar

Snell-Rood, E., & Snell-Rood, C. (2020). The developmental support hypothesis: Adaptive plasticity in neural development in response to cues of social support. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 375(1803), 20190491. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2019.0491.Suche in Google Scholar

Tonoike, Y. (2012). Understanding obsidian artifact distribution in Iran using pXRF analysis. Poster presented at the 39th International Symposium on Archaeometry (ISA).Suche in Google Scholar

Tymofiyeva, O., & Gaschler, R. (2021). Training-induced neural plasticity in youth: A systematic review of structural and functional MRI studies [Systematic Review]. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 14, 1–24. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2020.497245.Suche in Google Scholar

Wahida, G. A. (1981). The re-excavation of Zarzi, 1971. Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society, 47, 19–40.10.1017/S0079497X00008847Suche in Google Scholar

Walsh, S. (2022). Early evidence of extra-masticatory dental wear in a Neolithic community at Bestansur, Iraqi Kurdistan. International Journal of Osteoarchaeology, 32(6), 1264–1274. doi: 10.1002/oa.3162.Suche in Google Scholar

Ware, C., Dautricourt, S., Gonneaud, J., & Chételat, G. (2021). Does second language learning promote neuroplasticity in aging? A systematic review of cognitive and neuroimaging studies. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience, 13, 1–13. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2021.706672.Suche in Google Scholar

Watkins, T. (2003). Developing socio-cultural networks. Neo-Lithics, 2(3), 36–37.Suche in Google Scholar

Watkins, T. (2006). Neolithisation in Southwest Asia - the path to modernity. Documenta Praehistorica, 33, 71–88.10.4312/dp.33.9Suche in Google Scholar

Watkins, T. (2008). Supra-regional networks in the Neolithic of Southwest Asia. Journal of World Prehistory, 21, 139–171.10.1007/s10963-008-9013-zSuche in Google Scholar

Watkins, T., Baird, D., & Betts, A. V. G. (1989). Qermez Dere and the early aceramic Neolithic of N. Iraq. Paléorient, 15(1), 19–24.10.3406/paleo.1989.4481Suche in Google Scholar

Zeidi, M., & Conard, N. J. (2013). Chipped stone artifacts from the aceramic Neolithic site of Chogha Golan, Ilam Province, Western Iran. In F. Borrell, J. J. Ibáñez Estévez, & M. Molist (Eds.), Stone tools in transition: From hunter-gatherers to farming societies in the Near East. Papers presented to the 7th Conference on PPN Chipped and Ground Stone Industries of the Fertile Crescent (pp. 315–326). Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Servei de Publicacions.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Etched in Stone: The Kevermes Stone Stela From the Great Hungarian Plain

- Waste Around Longhouses: Taphonomy on LBK Settlement in Hlízov

- Raw Materials and Technological Choices: Case Study of Neolithic Black Pottery From the Middle Yangtze River Valley of China

- Disentangling Technological Traditions: Comparative Analysis of Chaînes Opératoires of Painted Pre-Hispanic Ceramics From Nariño, Colombia

- Ancestral Connections: Re-Evaluating Concepts of Superimpositioning and Vandalism in Rock Art Studies

- Disability and Care in Late Medieval Lund, Sweden: An Analysis of Trauma and Intersecting Identities, Aided by Photogrammetric Digitization and Visualization

- Assessing the Development in Open Access Publishing in Archaeology: A Case Study From Norway

- Decorated Standing Stones – The Hagbards Galge Monument in Southwest Sweden

- Geophysical Prospection of the South-Western Quarter of the Hellenistic Capital Artaxata in the Ararat Plain (Lusarat, Ararat Province, Armenia): The South-West Quarter, City Walls and an Early Christian Church

- Lessons From Ceramic Petrography: A Case of Technological Transfer During the Transition From Late to Inca Periods in Northwestern Argentina, Southern Andes

- An Experimental and Methodological Approach of Plant Fibres in Dental Calculus: The Case Study of the Early Neolithic Site of Cova del Pasteral (Girona, Spain)

- Bridging the Post-Excavation Gaps: Structured Guidance and Training for Post-Excavation in Archaeology

- Everyone Has to Start Somewhere: Democratisation of Digital Documentation and Visualisation in 3D

- The Bedrock of Rock Art: The Significance of Quartz Arenite as a Canvas for Rock Art in Central Sweden

- The Origin, Development and Decline of Lengyel Culture Figurative Finds

- New “Balkan Fashion” Developing Through the Neolithization Process: The Ceramic Annulets of Amzabegovo and Svinjarička Čuka

- From a Medieval Town to the Modern Fortress of Rosas (Girona-Spain). Combining Geophysics and Archaeological Excavation to Understand the Evolution of a Strategic Coastal Settlement

- Technical Transfers Between Chert Knappers: Investigating Gunflint Manufacture in the Eastern Egyptian Desert (Wadi Sannur, Northern Galala, Egypt)

- Early Neolithic Pottery Production in the Maltese Islands: Initiating a Għar Dalam and Skorba Pottery Fabric Classification

- Revealing the Origins: An Interdisciplinary Study Into the Provenance of Sacral Microarchitecture–The Unique Case of the Church Model From Žatec in Bohemia

- An Analogical and Analytical Approach to the Burçevi Monumental Tomb

- A Glimpse at Raw Material Economy and Production of Chipped Stones at the Neolithic (Starčevo) Site of Svinjarička Čuka, South Serbia

- Archaeological Lithotheques of Siliceous Rocks in Spain: First Diagnosis of the Lithotheque Thematic Network

- Mapping Changes in Settlement Number and Demography in the South of Israel from the Hellenistic to the Early Islamic Period

- Review Article

- Structural Measures Against the Risks of Flash Floods in Patara and Consequent Considerations Regarding the Location of the Oracle Sanctuary of Apollo

- Commentary Article

- A Framework for Archaeological Involvement with Human Genetic Data for European Prehistory

- Special Issue on Digital Religioscapes: Current Methodologies and Novelties in the Analysis of Sacr(aliz)ed Spaces, edited by Anaïs Lamesa, Asuman Lätzer-Lasar - Part II

- Goats and Goddesses. Digital Approach to the Religioscapes of Atargatis and Allat

- Conceiving Elements of Divinity: The Use of the Semantic Web for the Definition of Material Religiosity in the Levant During the Second Millennium BCE

- Deep Mapping the Asklepieion of Pergamon: Charting the Path Through Challenges, Choices, and Solutions

- Special Issue on Engaging the Public, Heritage and Educators through Material Culture Research, edited by Katherine Anne Wilson, Christina Antenhofer, & Thomas Pickles

- Inventories as Keys to Exploring Castles as Cultural Heritage

- Hohensalzburg Digital: Engaging the Public via a Local Time Machine Project

- Monastic Estates in the Wachau Region: Nodes of Exchange in Past and Present Days

- “Meitheal Adhmadóireachta” Exploring and Communicating Prehistoric Irish Woodcraft Through Remaking and Shared Experience

- Community, Public Archaeology, and Co-construction of Knowledge Through the Educational Project of a Rural Mountain School

- Valuing Material Cultural Heritage: Engaging Audience(s) Through Development-Led Archaeological Research

- Engaging the Public Through Prehistory: Experiences From an Inclusive Perspective

- Material Culture, the Public, and the Extraordinary – “Unloved” Museums Objects as the Tool to Fascinate

- Archaeologists on Social Media and Its Benefits for the Profession. The Results and Lessons Learnt from a Questionnaire

- Special Issue on Network Perspectives in the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East and Eastern Mediterranean, edited by Maria Gabriella Micale, Helen Dawson, & Antti A. Lahelma

- Networks of Pots: The Usage of Ceramics in Network Analysis in Mediterranean Archaeology

- Networks of Knowledge, Materials, and Practice in the Neolithic Zagros

- Weak Ties on Old Roads: Inscribed Stopping-Places and Complex Networks in the Eastern Desert of Graeco-Roman Egypt

- Mediterranean Trade Networks and the Diffusion and Syncretism of Art and Architecture Styles at Delos

- People and Things on the Move: Tracking Paths With Social Network Analysis

- Networks and the City: A Network Perspective on Procopius De Aed. I and the Building of Late Antique Constantinople

- Network Perspectives in the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East and Eastern Mediterranean

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Etched in Stone: The Kevermes Stone Stela From the Great Hungarian Plain

- Waste Around Longhouses: Taphonomy on LBK Settlement in Hlízov

- Raw Materials and Technological Choices: Case Study of Neolithic Black Pottery From the Middle Yangtze River Valley of China

- Disentangling Technological Traditions: Comparative Analysis of Chaînes Opératoires of Painted Pre-Hispanic Ceramics From Nariño, Colombia

- Ancestral Connections: Re-Evaluating Concepts of Superimpositioning and Vandalism in Rock Art Studies

- Disability and Care in Late Medieval Lund, Sweden: An Analysis of Trauma and Intersecting Identities, Aided by Photogrammetric Digitization and Visualization

- Assessing the Development in Open Access Publishing in Archaeology: A Case Study From Norway

- Decorated Standing Stones – The Hagbards Galge Monument in Southwest Sweden

- Geophysical Prospection of the South-Western Quarter of the Hellenistic Capital Artaxata in the Ararat Plain (Lusarat, Ararat Province, Armenia): The South-West Quarter, City Walls and an Early Christian Church

- Lessons From Ceramic Petrography: A Case of Technological Transfer During the Transition From Late to Inca Periods in Northwestern Argentina, Southern Andes

- An Experimental and Methodological Approach of Plant Fibres in Dental Calculus: The Case Study of the Early Neolithic Site of Cova del Pasteral (Girona, Spain)

- Bridging the Post-Excavation Gaps: Structured Guidance and Training for Post-Excavation in Archaeology

- Everyone Has to Start Somewhere: Democratisation of Digital Documentation and Visualisation in 3D

- The Bedrock of Rock Art: The Significance of Quartz Arenite as a Canvas for Rock Art in Central Sweden

- The Origin, Development and Decline of Lengyel Culture Figurative Finds

- New “Balkan Fashion” Developing Through the Neolithization Process: The Ceramic Annulets of Amzabegovo and Svinjarička Čuka

- From a Medieval Town to the Modern Fortress of Rosas (Girona-Spain). Combining Geophysics and Archaeological Excavation to Understand the Evolution of a Strategic Coastal Settlement

- Technical Transfers Between Chert Knappers: Investigating Gunflint Manufacture in the Eastern Egyptian Desert (Wadi Sannur, Northern Galala, Egypt)

- Early Neolithic Pottery Production in the Maltese Islands: Initiating a Għar Dalam and Skorba Pottery Fabric Classification

- Revealing the Origins: An Interdisciplinary Study Into the Provenance of Sacral Microarchitecture–The Unique Case of the Church Model From Žatec in Bohemia

- An Analogical and Analytical Approach to the Burçevi Monumental Tomb

- A Glimpse at Raw Material Economy and Production of Chipped Stones at the Neolithic (Starčevo) Site of Svinjarička Čuka, South Serbia

- Archaeological Lithotheques of Siliceous Rocks in Spain: First Diagnosis of the Lithotheque Thematic Network

- Mapping Changes in Settlement Number and Demography in the South of Israel from the Hellenistic to the Early Islamic Period

- Review Article

- Structural Measures Against the Risks of Flash Floods in Patara and Consequent Considerations Regarding the Location of the Oracle Sanctuary of Apollo

- Commentary Article

- A Framework for Archaeological Involvement with Human Genetic Data for European Prehistory

- Special Issue on Digital Religioscapes: Current Methodologies and Novelties in the Analysis of Sacr(aliz)ed Spaces, edited by Anaïs Lamesa, Asuman Lätzer-Lasar - Part II

- Goats and Goddesses. Digital Approach to the Religioscapes of Atargatis and Allat

- Conceiving Elements of Divinity: The Use of the Semantic Web for the Definition of Material Religiosity in the Levant During the Second Millennium BCE

- Deep Mapping the Asklepieion of Pergamon: Charting the Path Through Challenges, Choices, and Solutions

- Special Issue on Engaging the Public, Heritage and Educators through Material Culture Research, edited by Katherine Anne Wilson, Christina Antenhofer, & Thomas Pickles

- Inventories as Keys to Exploring Castles as Cultural Heritage

- Hohensalzburg Digital: Engaging the Public via a Local Time Machine Project

- Monastic Estates in the Wachau Region: Nodes of Exchange in Past and Present Days

- “Meitheal Adhmadóireachta” Exploring and Communicating Prehistoric Irish Woodcraft Through Remaking and Shared Experience

- Community, Public Archaeology, and Co-construction of Knowledge Through the Educational Project of a Rural Mountain School

- Valuing Material Cultural Heritage: Engaging Audience(s) Through Development-Led Archaeological Research

- Engaging the Public Through Prehistory: Experiences From an Inclusive Perspective

- Material Culture, the Public, and the Extraordinary – “Unloved” Museums Objects as the Tool to Fascinate

- Archaeologists on Social Media and Its Benefits for the Profession. The Results and Lessons Learnt from a Questionnaire

- Special Issue on Network Perspectives in the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East and Eastern Mediterranean, edited by Maria Gabriella Micale, Helen Dawson, & Antti A. Lahelma

- Networks of Pots: The Usage of Ceramics in Network Analysis in Mediterranean Archaeology

- Networks of Knowledge, Materials, and Practice in the Neolithic Zagros

- Weak Ties on Old Roads: Inscribed Stopping-Places and Complex Networks in the Eastern Desert of Graeco-Roman Egypt

- Mediterranean Trade Networks and the Diffusion and Syncretism of Art and Architecture Styles at Delos

- People and Things on the Move: Tracking Paths With Social Network Analysis

- Networks and the City: A Network Perspective on Procopius De Aed. I and the Building of Late Antique Constantinople

- Network Perspectives in the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East and Eastern Mediterranean