Improvement of cocoa powder properties through ultrasonic- and microwave-assisted alkalization

-

Dimas Rahadian Aji Muhammad

, Dion Pratama

Abstract

Improving the process efficiency is still a challenge in the alkalization process of cocoa powder. This research aims to study the effect of ultrasonic- and microwave-assisted alkalization on the quality attributes of cocoa powder. Three levels of process duration were used (5, 10, and 15 min), and then the physical and antioxidant properties of the cocoa powder were evaluated. The results show that ultrasonic- and microwave-assisted alkalization is more effective in improving cocoa powder’s darkness and red intensity than the conventional alkalization process. The cocoa powder produced using ultrasonic- and microwave-assisted alkalization significantly improved the pH to 7.59, solubility from 20 to 28% and wetting time to almost twice, depending on the type and duration of the process. However, both advanced methods caused a significant decrease in total phenols, flavonoids, and antioxidant activity by about 35, 22, and 38%, respectively, compared to the conventional method. This research provides further information on the potential use of ultrasonication and microwave techniques, particularly in cocoa powder processing that has not been explored previously.

1 Introduction

Cocoa is a vital economic agroforestry product in many countries, and it can be processed into many products, including cocoa powder, chocolate, and beverages [1]. The products of the cocoa agroindustry are highly competitive in the market, and thus, innovation of cocoa-derived products by the industry is needed mainly to attract consumers. Some attempts have been made previously by developing chocolate and cocoa drinks enriched with probiotics, various herbs and spices, and other functional ingredients [2–4]. However, up till now, innovation in cocoa powder products and production processes is still scarce.

Cocoa powder is one of the main products of the cocoa industry, which is widely used as an ingredient for baking and beverages. However, natural cocoa powder has some limitations for its application, particularly for beverage production purposes, including poor dispersibility and unappealing appearance. Hence, additional research must be carried out to ameliorate the characteristics of cocoa powder [5]. Alkalization is a strategy that can be carried out to improve cocoa powder properties. Basically, alkalization generally consists of mixing natural cocoa material with an alkali solution and treating this mixture with the combined effects of temperature and pressure. Thus, in this research the alkalization was conducted using a pressured pan in which the working principle is boiling with an increased pressure [6]. This method is usually done to improve cocoa powder dispersibility in water as well as for enhancing its flavor and color. Many research groups have attempted to design more effective alkalization methods and investigate its effects on the physicochemical and sensory properties of the alkalized cocoa. It is presumed that the process of alkalization can be improved by combining the conventional method with advanced techniques.

Ultrasound and microwave are successfully employed in many areas, including food production. Microwave, with its wavelength ranging from 106 to 109 nm, induces rapid chemical reactions due to the increase in temperature during its application. It has a frequency range of 0.3–300 GHz and is proven to be a process with high reproducibility [7]. Meanwhile, ultrasound is composed of mechanical sound waves with a frequency of >20 kHz, which can form cavitation bubbles that induces biochemical reactions [8]. Thus, microwave treatment and ultrasonication are techniques that can potentially be combined with alkalization process to alter the properties of cocoa powder. It is hypothesized that waves produced by microwave and ultrasonic devices can cause rapid chemical reactions and cavitation, respectively, in the cocoa powder, assisting the acceleration of alteration of cocoa powder characteristics.

To the best of our knowledge, there is no study involving microwave and ultrasound treatment in alkalization process. Recent research studies related to modification of cocoa powder for food and beverage making purposes only include the effect of cocoa powder production method on the flavor compounds [9], the impact of alkaline type and concentration on the quality of cocoa powder [10], and the influence of various types of cocoa powder and stabilizers on the quality attributes of cocoa beverages [5]. Therefore, it is important to investigate the feasibility of microwave- and ultrasound-assisted alkalization which can be applied in small-scale industry. As emphasized by Valverde-Garcia and colleagues [6], the effects of alkalization on the nutritional and functional properties of cocoa need to be deeply investigated since this process can substantially affect cocoa powder characteristics. Hence, this research aims to examine the effect of ultrasonic- and microwave-assisted alkalization on the physicochemical properties and antioxidant activities of cocoa powder.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Samples and chemicals

Natural cocoa powder, also known as non-alkalized cocoa powder, was obtained from PT Cargill Cocoa and Chocolate Gresik (Indonesia). KOH, FeCl3, ascorbic acid, sodium carbonate, acetic acid, and Folin–Ciocalteu reagent were purchased from Merck KGaA (Darmstadt, Germany). Meanwhile tannic acid, quercetin, gallic acid, and trichloroacetic acid were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Stenheim, Germany). 2,2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) for molecular biology was obtained from HiMedia Laboratories Pvt. Ltd (Nashik, India) AlCl3 and K3[Fe(CN)6] were purchased from PT Smart Lab Indonesia (Tangerang, Indonesia). All the chemicals and reagents are of analytical grade.

2.2 Sample preparation

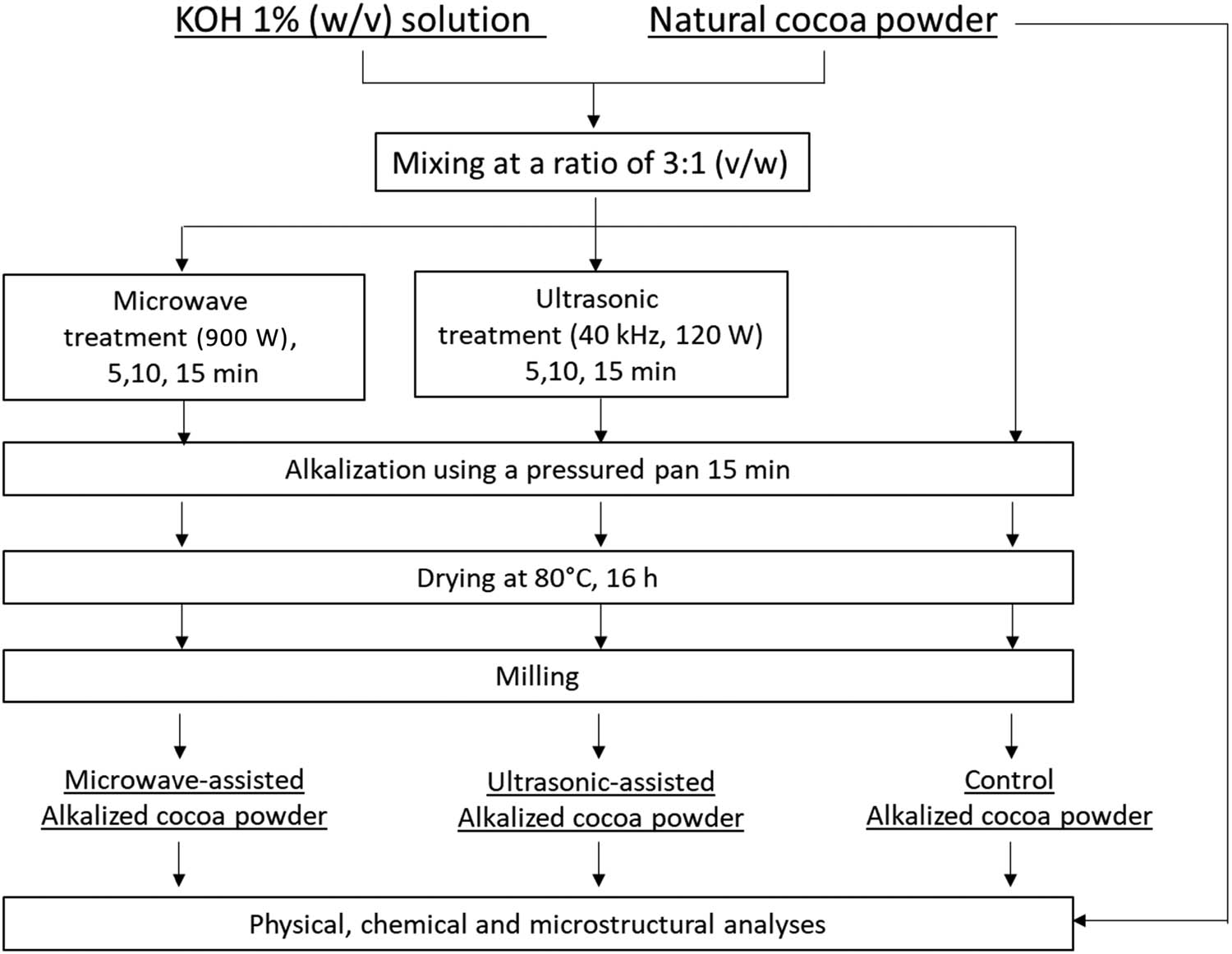

An alkali solution made of 1% KOH (w/v) in distilled water was prepared. The selected alkali concentration followed the previous study of Li et al. [11], in which 1% is considered light alkaline. Light alkali produced alkalized cocoa powder with higher antioxidant properties than heavy alkaline. The alkali solution was mixed with natural cocoa powder at a ratio of 3:1 (v/w) by manually stirring for about 3 min to get a homogenous mixture. The mixture was then separated into two parts in which one part was treated by ultrasonication at 40 kHz and 120 W using ultrasonicator (Baku BK-2000, Baku Guangdong, China) and the other part was treated with the lowest power (900 W) of the microwave (Sammic HM1001, DKSH Group, Bangkok Thailand). Ultrasonication and microwave treatment were conducted for 5, 10, and 15 min. After the treatments, the samples were then boiled in a small-scale pressured pan (Maxim 20 cm/4 L Maspion Group, Sidoarjo, Indonesia) for 15 min. Afterward, the samples were poured in a 20 × 20 baking pan with a thickness of 0.5 mm. Then, the samples were dried in an oven (Memmert 75, No. F-0109.0088, Schwabach, Germany) at 80°C for 16 h to obtain the dry alkalized cocoa powder. The dried samples were milled using a miller (Retsch ZM 200 Ultra Centrifugal Mill, Retsch GmBH, Haan, Germany). A maximum peripheral rotor speed of 92.8 m/s was set during the milling until the fineness of the product was smaller than 10 mm. Natural cocoa powder (without alkalization) and conventionally alkalized cocoa powder (without ultrasonication and microwave treatment) were also prepared as controls. The sample preparation is shown schematically in Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the experimental design.

2.3 Analytical determination

2.3.1 Wettability

A method described by Muhammad et al. [5] was used as the reference for the wetting time which is also known as wettability. The wetting time was determined by rapidly pouring 4 g of the milled cocoa powder in a glass with 40 mL of water (80°C), and then the time duration by which the poured cocoa powder becomes totally wet and has disappeared from the surface of the water was observed.

2.3.2 Solubility

The solubility analysis was conducted by initially mixing cocoa powder and water (80°C) in a ratio of 1:4 (w/v) using a magnetic stirrer for 30 min, after which the solution was centrifuged at 492g (2,000 rpm) for 10 min (Kokusan H-107, Kokusan Corp., Saitama, Japan). The supernatant was then collected and dried in an oven dryer at 120°C until a stable weight was reached. Solubility was stated as the percentage of the weight of soluble matter per weight of the initial material [5].

2.3.3 Sedimentation index (SI)

SI analysis was performed to determine the stability of the cocoa powder suspension. SI was calculated using equation (1) after visual assessment to see the relatively clear area where V is the total sample volume and V S is the volume of the relatively clear area after 24 h [5]

2.3.4 pH and morphology

The pH of the cocoa powder was determined using a pH meter (Ohaus ST3100, Ohaus Co., NJ, USA) at 20°C, while the morphology analysis was conducted using a scanning electron microscope (SEM) (Quanta 250 FEG, FEI Company, OR, USA). A double-sided adhesive carbon tape was used to embed the sample and the stubs. An acceleration voltage of 10 kV at a pressure of 80 Pa was employed. Electron micrographs were obtained from secondary electrons collected by a large-field detector.

2.3.5 Color properties

The color coordinates of CIELAB. (L*, a*, b*) were determined using a spectrophotometer (ColorFlex EZ 45/0 LAV, Hunter Associates Laboratory Inc., VA, USA). Following the method as described by Muhammad et al. [5], the obtained L*, a*, b* values were further used to calculate the level of the Chroma (C*), the °Hue, and the redness intensity of the samples, as well as the color difference between the alkalized and natural cocoa powder (ΔE) using equations (2)–(5), respectively:

2.3.6 Extraction of antioxidant compound

Antioxidant compound extraction is substantial prior to the antioxidant properties determination. Extraction was carried out following the method of Muhammad et al. [12]. Briefly, the fat content of cocoa powder (10 g) was removed by washing with 50 mL of n-hexane thrice. Afterward, n-hexane was discarded, and the cocoa powder was air-dried for 24 h to obtain the defatted cocoa powder. The dried defatted cocoa powder (4 g) was mixed with 10 mL of extractive solvent composed of acetone, distilled water, and acetic acid (70:29.8:0.2) in an ultrasonic bath for 30 min to extract antioxidant compounds, mainly phenols and flavonoids. It was then centrifuged for 10 min at 1,107g (3,000 rpm) and the supernatant was collected. The procedure was repeated twice. The collected supernatant was filtered to remove the residual particles and obtain the cocoa powder extract. The extract was then used for further analyses following the methods of Muhammad et al. [13].

2.3.7 Total phenol content

In the total phenol analysis, a solution of the cocoa powder extract (200 µL), distilled water (1 mL), and Folin–Ciocalteu reagent (200 µL) were prepared. After which, 7% of Na2CO3 (2.5 mL) solution and distilled water (2.1 mL) were added. The mixture was placed at ambient temperature condition (±25°C) in the absence of light for 1.5 h. After the incubation, the absorbance was measured at 760 nm in an UV-vis spectrophotometer (Shimadzu BioSpec-1600, Shimadzu Corp., Kyoto, Japan). A standard curve of gallic acid was constructed to determine the total phenolic content expressed as milligram gallic acid equivalent per gram dry weight (mg GAE/g DW).

2.3.8 Total flavonoid content

In the total flavonoid content analysis, 0.1 M AlCl3 (4 mL) was mixed with 160 µL of extract, followed by incubation for 40 min at ambient temperature (±25°C) in a dark condition. The absorbance was measured at 415 nm and the total flavonoid content was expressed as milligrams of quercetin equivalent per gram of dry weight (mg QE/g DW).

2.3.9 Ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP)

FRAP assay was performed by incubation (50°C) of a mixture containing cocoa powder extract (1 mL), phosphate buffer (0.2 M, pH 7, 2.5 mL), and 1% of K3[Fe(CN)6] (2,5) for 0.5 h. After that, 10% trichloroacetic acid (2.5 mL) was added to the mixture and then centrifuged (1,107g, 10 min) to remove the large particles and get the supernatant. Distilled water and 0.1% FeCl3 were then added to the supernatant. The ratio of distilled water, FeCl3 solution, and the supernatant was at 5:1:5. The absorbance was measured at 700 nm. A standard curve of ascorbic acid was prepared (0–100 µg/mL). Thus, FRAP was expressed as milligrams of ascorbic acid equivalent per gram of the extract (mg AAE/g).

2.3.10 DPPH-radical scavenging activity

In the DPPH assay, the cocoa powder extract (100 µL) was mixed with 4 mL of DPPH solution (0.01 mM). After incubation in the dark for 0.5 h, the absorbance was determined at 517 nm, and then the DPPH radical scavenging activity (% inhibition) was calculated using equation (6). The DPPH radical scavenging activity was expressed in IC50 (the concentration required to scavenge 50% of the initial DPPH radicals):

2.3.11 Experimental design and statistical analysis

The parameters that were considered to be affecting the characteristics of the alkalized cocoa powder were the technique and the duration. The experiment was performed by means of a completely randomized design, and the results represented the means of three replicates, except for SEM analysis. One-way ANOVA method followed by Duncan’s Multiple Range Test to test the differences among the samples. The differences were considered significant at 0.95 confidence level. The statistical analysis was executed by SPSS 23.0 Software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Effect of ultrasonic- and microwave-assisted alkalization on physical properties of cocoa powder

Table 1 shows that alkalization using 1% KOH increased the pH of cocoa powder in which the pH of natural cocoa powder was 5.72 and the pH of alkalized cocoa powder (all treatments) was 7.48 or even higher. It was shown that ultrasonic- and microwave-assisted alkalization resulted in a very slight effect in the pH as compared to the conventional alkalization. Yet, statistical analyses showed a significant difference between alkalized cocoa powder obtained by conventional method and ultrasonic-/microwave-assisted alkalization method (p < 0.05). It is also shown that the increase in pH of the alkalized cocoa powder was linearly correlated with the duration of microwave and ultrasonic treatment. It is believed that those treatments caused more intense chemical reactions, resulting in a higher pH alteration.

pH wetting time, solubility, and SI of alkalized cocoa powder

| Treatment | pH | Wetting time (s) | Solubility (%) | SI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control (natural cocoa powder) | 5.72 ± 0.01a | 80.87 ± 0.38c | 20.52 ± 0.08a | 50.67 ± 0.94d |

| Conventional alkalization | 7.50 ± 0.04b | 89.24 ±± 0.51e | 24.29 ± 0.17b | 49.06 ± 0.27cd |

| Ultrasonic-assisted alkalization | ||||

| 5 min | 7.60 ± 0.02c | 22.31 ± 0.36b | 24.79 ± 0.61bc | 48.47 ± 0.39cd |

| 10 min | 7.68 ± 0.02cd | 92.23 ± 0.37f | 25.56 ± 1.01d | 45.65 ± 0.54ab |

| 15 min | 7.59 ± 0.01cd | 158.04 ± 0.84h | 27.68 ± 1.02e | 44.19 ± 0.09a |

| Microwave-assisted alkalization | ||||

| 5 min | 7.48 ± 0.01cd | 6.81 ± 0.49a | 25.43 ± 0.53cd | 47.05 ± 0.28bc |

| 10 min | 7.53 ± 0.01cd | 86.73 ± 0.55d | 26.00 ± 0.10d | 44.61 ± 0.95ab |

| 15 min | 7.49 ± 0.01d | 141.97 ± 0.34g | 28.81 ± 0.28f | 43.92 ± 0.13a |

Mean values with different lowercase notations within the same column differ significantly (p < 0.05).

Substantial improvement in the solubility of cocoa powder was also observed in the microwave- and ultrasound-assisted alkalization. As shown in Table 1, alkalized cocoa powder produced by ultrasonic- and microwave-assisted alkalization had better solubility than that produced by conventional alkalization as well as natural cocoa powder. As such, the solubility of natural cocoa powder and alkalized cocoa powder processed using conventional method were about 20.52 and 24.29%, respectively, while the alkalized cocoa powder processed by ultrasonic- and microwave-assisted methods were about 27.68 and 28.81%, respectively. The statistical analyses showed a significant difference between alkalized cocoa powder obtained by conventional method and ultrasonic-/microwave-assisted alkalization method (p < 0.05). Table 1 also shows that increasing the duration of alkalization notably increased the solubility, regardless of the type of the treatments (p < 0.05).

In any case, the improvement in solubility by alkalization is attributed to the chemical modification due to alkali treatment. As for microwave-assisted alkalization, the microwave increased the temperature, triggering rapid chemical reactions [7]. Meanwhile, mechanical sound waves formed cavitation bubbles for ultrasonic-assisted alkalization, inducing more intense biochemical reactions [8]. In both cases, therefore, at a similar duration of the process, the solubility of alkalized cocoa powder assisted by microwave or ultrasonic process is better than that of the powder obtained by a conventional process.

In addition to solubility, a significant improvement was shown in the wetting time parameters. As shown, the conventional alkalization resulted in wetting time of 89 s, while the ultrasonication (10 and 15 min) resulted in the wetting time of 92 and 158 s, respectively, and the microwave treatment (15 min) resulted in the wetting time of 141 s. It is interesting that the duration of assisted alkalization was directly proportional to the wetting time implying that ultrasonication and microwave treatment had significant effect on this parameter. Furthermore, it is also notable that the lower duration of ultrasonication and microwave treatment resulted in a lower wetting time as compared to conventional alkalization. Up until now, this phenomenon is still under investigated.

Table 1 shows that ultrasonic treatment resulted in a longer wetting time than microwave treatment at a similar duration (p < 0.05). As such, ultrasonic-assisted alkalization at 5, 10, and 15 resulted in the wetting time of 22.31, 92.23, and 158.04 s, respectively. In contrast, microwave-assisted alkalization at the duration of 5, 10, and 15 resulted in the wetting time of 6.81, 86.73, and 141.97 s, respectively. Wetting time indicates the interfacial dynamics of particle–water interactions and it is substantially affected by hydrophobic properties of the particle. It was also reported by Amer et al. [14] that the higher alkalization degree, such as longer alkalization duration in this case, causes more intensive base-catalyzed hydrolysis reactions increasing the chemical sorption sites for water molecules in cocoa particles.

Wetting time has a linear correlation with suspension stability [5], which is also presented in this study. Cocoa powder can be suspended in the drink for a longer period in the condition of longer wetting time. Suspension stability is an important parameter in the quality of cocoa drink indicating how fast the cocoa powder deposits as sediment. The suspension stability can be measured by SI. The results showed that ultrasonic- and microwave-assisted alkalization had lower SI (p < 0.05) (Table 1), meaning that the treatments resulted in more stable suspensions. Interestingly, longer duration of treatments led to lower SI. For instance, ultrasonic-assisted alkalization at 5, 10, and 15 resulted in the SI of 48.47, 45.65, and 44.19, respectively. Meanwhile, microwave-assisted alkalization at the duration of 5, 10, and 15 resulted in the SI of 47.05, 44.61, and 43.93, respectively. Muhammad et al. [5] stated that insoluble matter may also affect the sedimentation of particles. Therefore, it is rational if the SI aligns with solubility, as clearly shown in Table 1. It is also noted that at 10 and 15 min, the SI between cocoa powder obtained by ultrasonic and microwave treatments was not statistically different (p > 0.05).

SEM analysis was able to visualize the physical modification of cocoa powder after the ultrasonic- and microwave-assisted alkalization. As revealed in Figure 2, natural cocoa powder had a regular and oval form. However, alkalization generally causes disruption of the powder structure; in the case of ultrasonic- and microwave-assisted alkalization, the disruption may be more intense, and thus the alkalization effect may be more pronounced. As well known, the microwave provides an alternative heat source and can create the opportunity to induce rapid chemical reactions [7], while ultrasonic wave creates cavitation bubbles causing hotspots and extreme local condition. These hotspots expedite the biochemical reactions in its vicinity [8]. Simply put, ultrasonication provides more access for alkali solution to interact with cocoa powder surface.

Microstructural properties of natural cocoa powder (a) and cocoa powder with alkalization – control (b), ultrasonic-assisted alkalization (c), and microwave-assisted alkalization (d).

The effects of ultrasonic- and microwave-assisted alkalization were also visibly shown in the color properties of cocoa powder. Generally, alkalization can darken the color of cocoa powder due to oxidation caused by the alkali. As shown, the lightness of the natural cocoa powder was 21.31 and that of alkalized cocoa powder was 14.19. In this study, the application of ultrasonic and microwave in the alkalization process led to a more pronounced effect of alkalization to the color properties of the cocoa powder (Table 2). Ultrasonic- and microwave-assisted alkalization caused darker powder, lower value of chroma and °Hue than conventional alkalization (p < 0.05). At the same time, it led to higher redness intensity (p < 0.05) and higher value of color difference between the alkalized and the natural cocoa powder (p < 0.05). The variation in color properties was also shown to be linearly correlated with the duration of the treatment. Nevertheless, at a similar duration, the color properties of the cocoa powder obtained by ultrasonic treatment were not significantly different with that obtained by microwave treatment. The appearance of the alkalized cocoa powder is presented in Figure 3.

Color properties of alkalized cocoa powder

| Sample and treatment | Lightness | Chroma | °Hue | Redness intensity | ∆E |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control (natural cocoa powder) | 21.31 ± 0.09d | 14.35 ± 0.06e | 43.95 ± 0.20c | 1.04 ± 0.01a | — |

| Conventional alkalization | 14.19 ± 0.06c | 10.14 ± 0.04d | 39.54 ± 0.25b | 1.21 ± 0.01d | 8.33 ± 0.09a |

| Ultrasonic-assisted alkalization | |||||

| 5 min | 14.08 ± 1.03c | 9.83 ± 0.73cd | 39.44 ± 0.52b | 1.22 ± 0.02d | 8.52 ± 1.05ab |

| 10 min | 13.51 ± 0.34ab | 9.65 ± 0.30bc | 38.35 ± 0.45a | 1.26 ± 0.02c | 8.51 ± 0.38cd |

| 15 min | 13.09 ± 0.02a | 9.59 ± 0.36bc | 38.04 ± 1.14a | 1.28 ± 0.05c | 9.58 ± 0.03de |

| Microwave-assisted alkalization | |||||

| 5 min | 13.76 ± 0.05bc | 9.81 ± 0.03cd | 38.37 ± 0.31a | 1.26 ± 0.01c | 8.87 ± 0.03b |

| 10 min | 13.42 ± 0.19ab | 9.34 ± 0.17ab | 38.22 ± 1.31a | 1.27 ± 0.01b | 9.41 ± 0.25de |

| 15 min | 13.04 ± 0.03a | 9.13 ± 0.22a | 37.93 ± 1.04a | 1.28 ± 0.05a | 9.85 ± 0.09e |

Mean values with different lowercase notations within the same column differ significantly (p < 0.05).

Appearance of alkalized cocoa powder.

3.2 Effect of ultrasonic- and microwave-assisted alkalization on antioxidant properties of cocoa powder

These results evidently show the potential use of ultrasonic and microwave treatment in alkalization process. However, the treatments also have drawbacks such that it reduced the phenolic content and antioxidant activity of the cocoa powder (Table 3). In general, the total phenols, total flavonoids, and antioxidant activity of alkalized cocoa powder were lower than that of natural cocoa powder (p < 0.05). The additional treatment of ultrasonic and microwave resulted in more noticeable reduction which may be due to a more intense chemical reaction during the alkalization process. As such, the total phenols and flavonoids of cocoa powder produced by conventional alkalization were about 20.90 mg GAE/g and 0.89 mg QE/g, respectively, while those of cocoa powders produced by advanced treatments were less than 20 mg GAE/g and 0.89 mg QE/g, respectively. Longer duration of treatments also caused lower phenol and flavonoid content. Similar phenomenon was also found in the FRAP activity as one of the antioxidant activity parameters of cocoa powder. It is understandable since FRAP activity had a positive correlation with phenolic content according to previous reports [13]. This result is also confirmed by the result of IC50 DPPH radical scavenging activity. As shown, the higher degree of alkalization caused the higher IC50 value meaning that more concentration of cocoa powder extract is required to inhibit 50% of radical reaction. This indicates that the antioxidant activity of the samples is lower. A similar phenomenon was found in the study of Sioriki et al. [15] explaining the decrease of active compounds after alkalization. Several studies reported a similar reduction in active compounds after alkalization [16–18].

Antioxidant properties of alkalized cocoa powder

| Treatment | Total phenolic content (mg GAE/g) | Total flavonoid content (mg QE/g) | DPPH IC50 (ppm) | FRAP (mg AAE/g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control (natural cocoa powder) | 35.23 ± 0.04g | 2.85 ± 0.02d | 35.07 ± 0.45a | 28.03 ± 0.27d |

| Conventional alkalization | 20.90 ± 0.01f | 0.89 ± 0.01c | 57.95 ± 0.65b | 21.40 ± 0.03c |

| Ultrasonic-assisted alkalization | ||||

| 5 min | 19.20 ± 0.45e | 0.88 ± 0.01c | 81.62 ± 0.02c | 15.15 ± 0.50b |

| 10 min | 15.36 ± 0.09c | 0.81 ± 0.01b | 82.48 ± 0.50cd | 14.21 ± 0.94ab |

| 15 min | 14.99 ± 0.73c | 0.78 ± 0.01b | 84.76 ± 0.10cd | 13.47 ± 0.76a |

| Microwave-assisted alkalization | ||||

| 5 min | 17.74 ± 0.01d | 0.72 ± 0.03a | 82.15 ± 0.82cd | 14.76 ± 0.59ab |

| 10 min | 14.32 ± 0.01b | 0.70 ± 0.09a | 82.72 ± 0.04cd | 13.70 ± 0.78ab |

| 15 min | 13.63 ± 0.56a | 0.68 ± 0.03a | 85.75 ± 0.76d | 13.25 ± 0.08a |

Mean values with different lowercase notations within the same column differ significantly (p < 0.05).

Phenolic content and antioxidant activity have gained high interest nowadays because they are closely associated with beneficial health effects [19,20]. This study shows that the alkalization coupled with microwave or ultrasonic may negatively impact these parameters. However, the primary purpose of alkalization is to improve the pH, color, solubility, and stability of cocoa powder. In these aspects, microwave or ultrasonic treatment demonstrates a significant contribution to improving the process of obtaining cocoa powder with a more intense color and better solubility and suspension stability. Further study related to the sensory profile of cocoa powder is recommended to investigate the other possible positive impacts of microwave- and ultrasonic-assisted processes.

Despite its limitations, this study provides the first attempt to involve microwave and ultrasonic processes and strengthen the new paradigm in combining the advanced method with conventional alkalization. The methods proposed in this study can be alternatives in addition to a recent method combining alkalization with extrusion and cold plasma technique [21,22]. As all the novel proposed alkalization methods still have limitations, particularly regarding the bioactive content, finding a new alkalization method for retaining the phenolic content and antioxidant activity of the cocoa powder is encouraged to be explored in the future. To better understand the bioactive compounds’ stability during alkalization, analysis using metabolomic approaches is highly recommended [23].

4 Conclusion

To sum up, ultrasonication and microwave treatment were potentially used in the alkalization process to improve the physical properties of cocoa powder to some extent. Ultrasonication and microwave treatment modify the color properties of cocoa powder to be more appealing by increasing the darkness and red intensity. The color difference of cocoa powders produced by the treatments was higher than that of the cocoa powder produced by conventional alkalization. Cocoa powders produced by using ultrasonic- and microwave-assisted alkalization are suitable for beverage making purposes as the technique is proven to improve the pH, solubility, and wetting time, and at the same time decrease the SI of cocoa powder. However, the methods also cause significant decrease in total phenols, flavonoids, and antioxidant activity. Based on the evaluation of each parameter, ultrasonic-assisted alkalization seems more promising in changing the physical properties of cocoa powder with a better retainment of antioxidant properties. However, the solubility of the alkalized cocoa powder obtained by ultrasonic treatment was lower than that obtained by microwave treatment. Thus, the results obtained in this study are still considered not satisfying. Further research by combining other advanced methods with alkalization process may be required. Despite the limitation of each method, this research provides new insights for the application of ultrasonic and microwave treatment to assist alkalization process. Metabolomic approach may be significant to understand the behavior of bioactive compounds during ultrasonic- and microwave-assisted alkalization.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank PT Cargill Cocoa and Chocolate Gresik (Indonesia) for giving the opportunity for the second author (D.P.) to do internship and giving free sample of natural cocoa powder.

-

Funding information: This research was financially supported by Universitas Sebelas Maret through Hibah Kolaborasi Internasional 2023 (Grant no. 228/UN27.22/PT.01.03/2023).

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and consented to its submission to the journal, reviewed all the results and approved the final version of the manuscript. D.R.A.M.: conceptualization, funding acquisition, supervision, writing – review and editing; D.P. (2nd author): data curation, formal analysis, investigation; D.P. (3rd author): validation, writing – review; S.A.: writing – review & editing; M.F.A.: writing – review and editing; S.P.P.: supervision; E.F.: supervision.

-

Conflict of interest: The second author (D.P.) did internship at PT Cargill Cocoa and Chocolate Gresik (Indonesia). The company gave free sample of natural cocoa powder, but was not involved in the experimentation, data interpretation, writing, or publication of this study at Universitas Sebelas Maret. The other authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to disclose. None of the authors received payment for consultation or expert testimony and do not own stock or stock options from PT Cargill Cocoa and Chocolate Gresik (Indonesia).

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] Praseptiangga D, Zambrano JMG, Sanjaya AP, Muhammad DRA. Challenges in the development of the cocoa and chocolate industry in Indonesia: a case study in Madiun, East Java. AIMS Agric Food. 2020;5(4):920–37.Search in Google Scholar

[2] Muhammad DRA, Rahayu ES, Fibri DLN. Revisiting the development of probiotic-based functional chocolates. Rev Agric Sci. 2021;9:233–48.Search in Google Scholar

[3] Faiqoh KEN, Muhammad DRA, Praseptiangga D. Ginger-flavoured ready-to-drink cocoa beverage formulated with high and low-fat content powder: consumer preference, properties and stability. Food Res. 2021;5(2):7–17.Search in Google Scholar

[4] Muhammad DRA, Zulfa F, Purnomo D, Widiatmoko C, Fibri DLN. Consumer acceptance of chocolate formulated with functional ingredient. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science. Vol. 637, No. 1. IOP Publishing; 2021. p. 012081.Search in Google Scholar

[5] Muhammad DRA, Kongor JE, Dewettinck K. Investigating the effect of different types of cocoa powder and stabilizers on suspension stability of cinnamon-cocoa drink. J Food Sci Technol. 2021;58(10):3933–41.Search in Google Scholar

[6] Valverde Garcia D, Perez Esteve E, Barat Baviera JM. Changes in cocoa properties induced by the alkalization process: a review. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf. 2020;19(4):2200–21.Search in Google Scholar

[7] Kumar A, Kuang Y, Liang Z, Sun X. Microwave chemistry, recent advancements, and eco-friendly microwave-assisted synthesis of nanoarchitectures and their applications: a review. Mater Today Nano. 2020;11:100076.Search in Google Scholar

[8] Kumar K, Srivastav S, Sharanagat VS. Ultrasound assisted extraction (UAE) of bioactive compounds from fruit and vegetable processing by-products: a review. Ultrason Sonochem. 2021;70:105325.Search in Google Scholar

[9] Mohamadi Alasti F, Asefi N, Maleki R, SeiiedlouHeris SS. Investigating the flavor compounds in the cocoa powder production process. Food Sci Nutr. 2019;7(12):3892–901.Search in Google Scholar

[10] Alasti FM, Asefi N, Maleki R, SeiiedlouHeris SS. The influence of three different types and dosage of alkaline on the inherent properties in cocoa powder. J Food Sci Technol. 2020;57(7):2561–71.Search in Google Scholar

[11] Li Y, Feng Y, Zhu S, Luo C, Ma J, Zhong F. The effect of alkalization on the bioactive and flavor related components in commercial cocoa powder. J Food Compos Anal. 2012;25(1):17–23.Search in Google Scholar

[12] Muhammad DRA, Saputro AD, Rottiers H, Van de Walle D, Dewettinck K. Physicochemical properties and antioxidant activities of chocolates enriched with engineered cinnamon nanoparticles. Eur Food Res Technol. 2018;244:1185–202.Search in Google Scholar

[13] Muhammad DRA, Praseptiangga D, Van de Walle D, Dewettinck K. Interaction between natural antioxidants derived from cinnamon and cocoa in binary and complex mixtures. Food Chem. 2017;231:356–64.Search in Google Scholar

[14] Amer A, Schaumann GE, Diehl D. The effect of pH modification on wetting kinetics of a naturally water-repellent coniferous forest soil. Eur J Soil Sci. 2017;68:317–26.Search in Google Scholar

[15] Sioriki E, Tuenter E, Van de Walle D, Lemarcq V, Cazin CS, Nolan SP, et al. The effect of cocoa alkalization on the non-volatile and volatile mood-enhancing compounds. Food Chem. 2022;381:132082.Search in Google Scholar

[16] Demirci S, Elmaci C, Atalar İ, Toker OS, Palabiyik I, Konar N. Influence of process conditions of alkalization on quality of cocoa powder. Food Res Int. 2024;182:114147.Search in Google Scholar

[17] Sioriki E, Lemarcq V, Alhakim F, Triharyogi H, Tuenter E, Cazin CS, et al. Impact of alkalization conditions on the phytochemical content of cocoa powder and the aroma of cocoa drinks. Lwt. 2021;145:111181.Search in Google Scholar

[18] Greño M, Herrero M, Cifuentes A, Marina ML, Castro-Puyana M. Assessment of cocoa powder changes during the alkalization process using untargeted metabolomics. Lwt. 2022;172:114207.Search in Google Scholar

[19] Cerit I, Demirkol O, Avcı A, Arkan BS. Phenolic content and oxidative stability of chocolates produced with roasted and unroasted cocoa beans. Food Sci Technol Int. 2024;30(5):450–61.Search in Google Scholar

[20] Razola-Díaz MDC, Aznar-Ramos MJ, Verardo V, Melgar-Locatelli S, Castilla-Ortega E, Rodríguez-Pérez C. Exploring the nutritional composition and bioactive compounds in different cocoa powders. Antioxidants. 2023;12(3):716.Search in Google Scholar

[21] Palabiyik I, Kopuk B, Konar N, Toker OS. Investigation of cold plasma technique as an alternative to conventional alkalization of cocoa powders. Innov Food Sci Emerg Technol. 2023;88:103440.Search in Google Scholar

[22] Valverde D, Behrends B, Pérez-Esteve É, Kuhnert N, Barat JM. Functional changes induced by extrusion during cocoa alkalization. Food Res Int. 2020;136:109469.Search in Google Scholar

[23] Palma-Morales M, Rangel-Huerta OD, Díaz C, Castilla-Ortega E, Rodríguez-Pérez C. Integration of network-based approaches for assessing variations in metabolic profiles of alkalized and non-alkalized commercial cocoa powders. Food Chem: X. 2024;23:101651.Search in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- Supplementation of P-solubilizing purple nonsulfur bacteria, Rhodopseudomonas palustris improved soil fertility, P nutrient, growth, and yield of Cucumis melo L.

- Yield gap variation in rice cultivation in Indonesia

- Effects of co-inoculation of indole-3-acetic acid- and ammonia-producing bacteria on plant growth and nutrition, soil elements, and the relationships of soil microbiomes with soil physicochemical parameters

- Impact of mulching and planting time on spring-wheat (Triticum aestivum) growth: A combined field experiment and empirical modeling approach

- Morphological diversity, correlation studies, and multiple-traits selection for yield and yield components of local cowpea varieties

- Participatory on-farm evaluation of new orange-fleshed sweetpotato varieties in Southern Ethiopia

- Yield performance and stability analysis of three cultivars of Gayo Arabica coffee across six different environments

- Biology of Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) on different types of plants feeds: Potency as a pest on various agricultural plants

- Antidiabetic activity of methanolic extract of Hibiscus sabdariffa Linn. fruit in alloxan-induced Swiss albino diabetic mice

- Bioinformatics investigation of the effect of volatile and non-volatile compounds of rhizobacteria in inhibiting late embryogenesis abundant protein that induces drought tolerance

- Nicotinamide as a biostimulant improves soybean growth and yield

- Farmer’s willingness to accept the sustainable zoning-based organic farming development plan: A lesson from Sleman District, Indonesia

- Uncovering hidden determinants of millennial farmers’ intentions in running conservation agriculture: An application of the Norm Activation Model

- Mediating role of leadership and group capital between human capital component and sustainability of horticultural agribusiness institutions in Indonesia

- Biochar technology to increase cassava crop productivity: A study of sustainable agriculture on degraded land

- Effect of struvite on the growth of green beans on Mars and Moon regolith simulants

- UrbanAgriKG: A knowledge graph on urban agriculture and its embeddings

- Provision of loans and credit by cocoa buyers under non-price competition: Cocoa beans market in Ghana

- Effectiveness of micro-dosing of lime on selected chemical properties of soil in Banja District, North West, Ethiopia

- Effect of weather, nitrogen fertilizer, and biostimulators on the root size and yield components of Hordeum vulgare

- Effects of selected biostimulants on qualitative and quantitative parameters of nine cultivars of the genus Capsicum spp.

- Growth, yield, and secondary metabolite responses of three shallot cultivars at different watering intervals

- Design of drainage channel for effective use of land on fully mechanized sugarcane plantations: A case study at Bone Sugarcane Plantation

- Technical feasibility and economic benefit of combined shallot seedlings techniques in Indonesia

- Control of Meloidogyne javanica in banana by endophytic bacteria

- Comparison of important quality components of red-flesh kiwifruit (Actinidia chinensis) in different locations

- Efficiency of rice farming in flood-prone areas of East Java, Indonesia

- Comparative analysis of alpine agritourism in Trentino, Tyrol, and South Tyrol: Regional variations and prospects

- Detection of Fusarium spp. infection in potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) during postharvest storage through visible–near-infrared and shortwave–near-infrared reflectance spectroscopy

- Forage yield, seed, and forage qualitative traits evaluation by determining the optimal forage harvesting stage in dual-purpose cultivation in safflower varieties (Carthamus tinctorius L.)

- The influence of tourism on the development of urban space: Comparison in Hanoi, Danang, and Ho Chi Minh City

- Optimum intra-row spacing and clove size for the economical production of garlic (Allium sativum L.) in Northwestern Highlands of Ethiopia

- The role of organic rice farm income on farmer household welfare: Evidence from Yogyakarta, Indonesia

- Exploring innovative food in a developing country: Edible insects as a sustainable option

- Genotype by environment interaction and performance stability of common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) cultivars grown in Dawuro zone, Southwestern Ethiopia

- Factors influencing green, environmentally-friendly consumer behaviour

- Factors affecting coffee farmers’ access to financial institutions: The case of Bandung Regency, Indonesia

- Morphological and yield trait-based evaluation and selection of chili (Capsicum annuum L.) genotypes suitable for both summer and winter seasons

- Sustainability analysis and decision-making strategy for swamp buffalo (Bubalus bubalis carabauesis) conservation in Jambi Province, Indonesia

- Understanding factors affecting rice purchasing decisions in Indonesia: Does rice brand matter?

- An implementation of an extended theory of planned behavior to investigate consumer behavior on hygiene sanitation-certified livestock food products

- Information technology adoption in Indonesia’s small-scale dairy farms

- Draft genome of a biological control agent against Bipolaris sorokiniana, the causal phytopathogen of spot blotch in wheat (Triticum turgidum L. subsp. durum): Bacillus inaquosorum TSO22

- Assessment of the recurrent mutagenesis efficacy of sesame crosses followed by isolation and evaluation of promising genetic resources for use in future breeding programs

- Fostering cocoa industry resilience: A collaborative approach to managing farm gate price fluctuations in West Sulawesi, Indonesia

- Field investigation of component failures for selected farm machinery used in small rice farming operations

- Near-infrared technology in agriculture: Rapid, simultaneous, and non-destructive determination of inner quality parameters on intact coffee beans

- The synergistic application of sucrose and various LED light exposures to enhance the in vitro growth of Stevia rebaudiana (Bertoni)

- Weather index-based agricultural insurance for flower farmers: Willingness to pay, sales, and profitability perspectives

- Meta-analysis of dietary Bacillus spp. on serum biochemical and antioxidant status and egg quality of laying hens

- Biochemical characterization of trypsin from Indonesian skipjack tuna (Katsuwonus pelamis) viscera

- Determination of C-factor for conventional cultivation and soil conservation technique used in hop gardens

- Empowering farmers: Unveiling the economic impacts of contract farming on red chilli farmers’ income in Magelang District, Indonesia

- Evaluating salt tolerance in fodder crops: A field experiment in the dry land

- Labor productivity of lowland rice (Oryza sativa L.) farmers in Central Java Province, Indonesia

- Cropping systems and production assessment in southern Myanmar: Informing strategic interventions

- The effect of biostimulants and red mud on the growth and yield of shallots in post-unlicensed gold mining soil

- Effects of dietary Adansonia digitata L. (baobab) seed meal on growth performance and carcass characteristics of broiler chickens: A systematic review and meta-analysis

- Analysis and structural characterization of the vid-pisco market

- Pseudomonas fluorescens SP007s enhances defense responses against the soybean bacterial pustule caused by Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. glycines

- A brief investigation on the prospective of co-composted biochar as a fertilizer for Zucchini plants cultivated in arid sandy soil

- Supply chain efficiency of red chilies in the production center of Sleman Indonesia based on performance measurement system

- Investment development path for developed economies: Is agriculture different?

- Power relations among actors in laying hen business in Indonesia: A MACTOR analysis

- High-throughput digital imaging and detection of morpho-physiological traits in tomato plants under drought

- Converting compression ignition engine to dual-fuel (diesel + CNG) engine and experimentally investigating its performance and emissions

- Structuration, risk management, and institutional dynamics in resolving palm oil conflicts

- Spacing strategies for enhancing drought resilience and yield in maize agriculture

- Composition and quality of winter annual agrestal and ruderal herbages of two different land-use types

- Investigating Spodoptera spp. diversity, percentage of attack, and control strategies in the West Java, Indonesia, corn cultivation

- Yield stability of biofertilizer treatments to soybean in the rainy season based on the GGE biplot

- Evaluating agricultural yield and economic implications of varied irrigation depths on maize yield in semi-arid environments, at Birfarm, Upper Blue Nile, Ethiopia

- Chemometrics for mapping the spatial nitrate distribution on the leaf lamina of fenugreek grown under varying nitrogenous fertilizer doses

- Pomegranate peel ethanolic extract: A promising natural antioxidant, antimicrobial agent, and novel approach to mitigate rancidity in used edible oils

- Transformative learning and engagement with organic farming: Lessons learned from Indonesia

- Tourism in rural areas as a broader concept: Some insights from the Portuguese reality

- Assessment enhancing drought tolerance in henna (Lawsonia inermis L.) ecotypes through sodium nitroprusside foliar application

- Edible insects: A survey about perceptions regarding possible beneficial health effects and safety concerns among adult citizens from Portugal and Romania

- Phenological stages analysis in peach trees using electronic nose

- Harvest date and salicylic acid impact on peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.) properties under different humidity conditions

- Hibiscus sabdariffa L. petal biomass: A green source of nanoparticles of multifarious potential

- Use of different vegetation indices for the evaluation of the kinetics of the cherry tomato (Solanum lycopersicum var. cerasiforme) growth based on multispectral images by UAV

- First evidence of microplastic pollution in mangrove sediments and its ingestion by coral reef fish: Case study in Biawak Island, Indonesia

- Physical and textural properties and sensory acceptability of wheat bread partially incorporated with unripe non-commercial banana cultivars

- Cereibacter sphaeroides ST16 and ST26 were used to solubilize insoluble P forms to improve P uptake, growth, and yield of rice in acidic and extreme saline soil

- Avocado peel by-product in cattle diets and supplementation with oregano oil and effects on production, carcass, and meat quality

- Optimizing inorganic blended fertilizer application for the maximum grain yield and profitability of bread wheat and food barley in Dawuro Zone, Southwest Ethiopia

- The acceptance of social media as a channel of communication and livestock information for sheep farmers

- Adaptation of rice farmers to aging in Thailand

- Combined use of improved maize hybrids and nitrogen application increases grain yield of maize, under natural Striga hermonthica infestation

- From aquatic to terrestrial: An examination of plant diversity and ecological shifts

- Statistical modelling of a tractor tractive performance during ploughing operation on a tropical Alfisol

- Participation in artisanal diamond mining and food security: A case study of Kasai Oriental in DR Congo

- Assessment and multi-scenario simulation of ecosystem service values in Southwest China’s mountainous and hilly region

- Analysis of agricultural emissions and economic growth in Europe in search of ecological balance

- Bacillus thuringiensis strains with high insecticidal activity against insect larvae of the orders Coleoptera and Lepidoptera

- Technical efficiency of sugarcane farming in East Java, Indonesia: A bootstrap data envelopment analysis

- Comparison between mycobiota diversity and fungi and mycotoxin contamination of maize and wheat

- Evaluation of cultivation technology package and corn variety based on agronomy characters and leaf green indices

- Exploring the association between the consumption of beverages, fast foods, sweets, fats, and oils and the risk of gastric and pancreatic cancers: Findings from case–control study

- Phytochemical composition and insecticidal activity of Acokanthera oblongifolia (Hochst.) Benth & Hook.f. ex B.D.Jacks. extract on life span and biological aspects of Spodoptera littoralis (Biosd.)

- Land use management solutions in response to climate change: Case study in the central coastal areas of Vietnam

- Evaluation of coffee pulp as a feed ingredient for ruminants: A meta-analysis

- Interannual variations of normalized difference vegetation index and potential evapotranspiration and their relationship in the Baghdad area

- Harnessing synthetic microbial communities with nitrogen-fixing activity to promote rice growth

- Agronomic and economic benefits of rice–sweetpotato rotation in lowland rice cropping systems in Uganda

- Response of potato tuber as an effect of the N-fertilizer and paclobutrazol application in medium altitude

- Bridging the gap: The role of geographic proximity in enhancing seed sustainability in Bandung District

- Evaluation of Abrams curve in agricultural sector using the NARDL approach

- Challenges and opportunities for young farmers in the implementation of the Rural Development Program 2014–2020 of the Republic of Croatia

- Yield stability of ten common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) genotypes at different sowing dates in Lubumbashi, South-East of DR Congo

- Effects of encapsulation and combining probiotics with different nitrate forms on methane emission and in vitro rumen fermentation characteristics

- Phytochemical analysis of Bienertia sinuspersici extract and its antioxidant and antimicrobial activities

- Evaluation of relative drought tolerance of grapevines by leaf fluorescence parameters

- Yield assessment of new streak-resistant topcross maize hybrids in Benin

- Improvement of cocoa powder properties through ultrasonic- and microwave-assisted alkalization

- Potential of ecoenzymes made from nutmeg (Myristica fragrans) leaf and pulp waste as bioinsecticides for Periplaneta americana

- Analysis of farm performance to realize the sustainability of organic cabbage vegetable farming in Getasan Semarang, Indonesia

- Revealing the influences of organic amendment-derived dissolved organic matter on growth and nutrient accumulation in lettuce seedlings (Lactuca sativa L.)

- Identification of viruses infecting sweetpotato (Ipomoea batatas Lam.) in Benin

- Assessing the soil physical and chemical properties of long-term pomelo orchard based on tree growth

- Investigating access and use of digital tools for agriculture among rural farmers: A case study of Nkomazi Municipality, South Africa

- Does sex influence the impact of dietary vitD3 and UVB light on performance parameters and welfare indicators of broilers?

- Design of intelligent sprayer control for an autonomous farming drone using a multiclass support vector machine

- Deciphering salt-responsive NB-ARC genes in rice transcriptomic data: A bioinformatics approach with gene expression validation

- Review Articles

- Impact of nematode infestation in livestock production and the role of natural feed additives – A review

- Role of dietary fats in reproductive, health, and nutritional benefits in farm animals: A review

- Climate change and adaptive strategies on viticulture (Vitis spp.)

- The false tiger of almond, Monosteira unicostata (Hemiptera: Tingidae): Biology, ecology, and control methods

- A systematic review on potential analogy of phytobiomass and soil carbon evaluation methods: Ethiopia insights

- A review of storage temperature and relative humidity effects on shelf life and quality of mango (Mangifera indica L.) fruit and implications for nutrition insecurity in Ethiopia

- Green extraction of nutmeg (Myristica fragrans) phytochemicals: Prospective strategies and roadblocks

- Potential influence of nitrogen fertilizer rates on yield and yield components of carrot (Dacus carota L.) in Ethiopia: Systematic review

- Corn silk: A promising source of antimicrobial compounds for health and wellness

- State and contours of research on roselle (Hibiscus sabdariffa L.) in Africa

- The potential of phosphorus-solubilizing purple nonsulfur bacteria in agriculture: Present and future perspectives

- Minor millets: Processing techniques and their nutritional and health benefits

- Meta-analysis of reproductive performance of improved dairy cattle under Ethiopian environmental conditions

- Review on enhancing the efficiency of fertilizer utilization: Strategies for optimal nutrient management

- The nutritional, phytochemical composition, and utilisation of different parts of maize: A comparative analysis

- Motivations for farmers’ participation in agri-environmental scheme in the EU, literature review

- Evolution of climate-smart agriculture research: A science mapping exploration and network analysis

- Short Communications

- Music enrichment improves the behavior and leukocyte profile of dairy cattle

- Effect of pruning height and organic fertilization on the morphological and productive characteristics of Moringa oleifera Lam. in the Peruvian dry tropics

- Corrigendum

- Corrigendum to “Bioinformatics investigation of the effect of volatile and non-volatile compounds of rhizobacteria in inhibiting late embryogenesis abundant protein that induces drought tolerance”

- Corrigendum to “Composition and quality of winter annual agrestal and ruderal herbages of two different land-use types”

- Special issue: Smart Agriculture System for Sustainable Development: Methods and Practices

- Construction of a sustainable model to predict the moisture content of porang powder (Amorphophallus oncophyllus) based on pointed-scan visible near-infrared spectroscopy

- FruitVision: A deep learning based automatic fruit grading system

- Energy harvesting and ANFIS modeling of a PVDF/GO-ZNO piezoelectric nanogenerator on a UAV

- Effects of stress hormones on digestibility and performance in cattle: A review

- Special Issue of The 4th International Conference on Food Science and Engineering (ICFSE) 2022 - Part II

- Assessment of omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acid profiles and ratio of omega-6/omega-3 of white eggs produced by laying hens fed diets enriched with omega-3 rich vegetable oil

- Special Issue on FCEM - International Web Conference on Food Choice & Eating Motivation - Part II

- Special Issue on FCEM – International Web Conference on Food Choice & Eating Motivation: Message from the editor

- Fruit and vegetable consumption: Study involving Portuguese and French consumers

- Knowledge about consumption of milk: Study involving consumers from two European Countries – France and Portugal

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- Supplementation of P-solubilizing purple nonsulfur bacteria, Rhodopseudomonas palustris improved soil fertility, P nutrient, growth, and yield of Cucumis melo L.

- Yield gap variation in rice cultivation in Indonesia

- Effects of co-inoculation of indole-3-acetic acid- and ammonia-producing bacteria on plant growth and nutrition, soil elements, and the relationships of soil microbiomes with soil physicochemical parameters

- Impact of mulching and planting time on spring-wheat (Triticum aestivum) growth: A combined field experiment and empirical modeling approach

- Morphological diversity, correlation studies, and multiple-traits selection for yield and yield components of local cowpea varieties

- Participatory on-farm evaluation of new orange-fleshed sweetpotato varieties in Southern Ethiopia

- Yield performance and stability analysis of three cultivars of Gayo Arabica coffee across six different environments

- Biology of Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) on different types of plants feeds: Potency as a pest on various agricultural plants

- Antidiabetic activity of methanolic extract of Hibiscus sabdariffa Linn. fruit in alloxan-induced Swiss albino diabetic mice

- Bioinformatics investigation of the effect of volatile and non-volatile compounds of rhizobacteria in inhibiting late embryogenesis abundant protein that induces drought tolerance

- Nicotinamide as a biostimulant improves soybean growth and yield

- Farmer’s willingness to accept the sustainable zoning-based organic farming development plan: A lesson from Sleman District, Indonesia

- Uncovering hidden determinants of millennial farmers’ intentions in running conservation agriculture: An application of the Norm Activation Model

- Mediating role of leadership and group capital between human capital component and sustainability of horticultural agribusiness institutions in Indonesia

- Biochar technology to increase cassava crop productivity: A study of sustainable agriculture on degraded land

- Effect of struvite on the growth of green beans on Mars and Moon regolith simulants

- UrbanAgriKG: A knowledge graph on urban agriculture and its embeddings

- Provision of loans and credit by cocoa buyers under non-price competition: Cocoa beans market in Ghana

- Effectiveness of micro-dosing of lime on selected chemical properties of soil in Banja District, North West, Ethiopia

- Effect of weather, nitrogen fertilizer, and biostimulators on the root size and yield components of Hordeum vulgare

- Effects of selected biostimulants on qualitative and quantitative parameters of nine cultivars of the genus Capsicum spp.

- Growth, yield, and secondary metabolite responses of three shallot cultivars at different watering intervals

- Design of drainage channel for effective use of land on fully mechanized sugarcane plantations: A case study at Bone Sugarcane Plantation

- Technical feasibility and economic benefit of combined shallot seedlings techniques in Indonesia

- Control of Meloidogyne javanica in banana by endophytic bacteria

- Comparison of important quality components of red-flesh kiwifruit (Actinidia chinensis) in different locations

- Efficiency of rice farming in flood-prone areas of East Java, Indonesia

- Comparative analysis of alpine agritourism in Trentino, Tyrol, and South Tyrol: Regional variations and prospects

- Detection of Fusarium spp. infection in potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) during postharvest storage through visible–near-infrared and shortwave–near-infrared reflectance spectroscopy

- Forage yield, seed, and forage qualitative traits evaluation by determining the optimal forage harvesting stage in dual-purpose cultivation in safflower varieties (Carthamus tinctorius L.)

- The influence of tourism on the development of urban space: Comparison in Hanoi, Danang, and Ho Chi Minh City

- Optimum intra-row spacing and clove size for the economical production of garlic (Allium sativum L.) in Northwestern Highlands of Ethiopia

- The role of organic rice farm income on farmer household welfare: Evidence from Yogyakarta, Indonesia

- Exploring innovative food in a developing country: Edible insects as a sustainable option

- Genotype by environment interaction and performance stability of common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) cultivars grown in Dawuro zone, Southwestern Ethiopia

- Factors influencing green, environmentally-friendly consumer behaviour

- Factors affecting coffee farmers’ access to financial institutions: The case of Bandung Regency, Indonesia

- Morphological and yield trait-based evaluation and selection of chili (Capsicum annuum L.) genotypes suitable for both summer and winter seasons

- Sustainability analysis and decision-making strategy for swamp buffalo (Bubalus bubalis carabauesis) conservation in Jambi Province, Indonesia

- Understanding factors affecting rice purchasing decisions in Indonesia: Does rice brand matter?

- An implementation of an extended theory of planned behavior to investigate consumer behavior on hygiene sanitation-certified livestock food products

- Information technology adoption in Indonesia’s small-scale dairy farms

- Draft genome of a biological control agent against Bipolaris sorokiniana, the causal phytopathogen of spot blotch in wheat (Triticum turgidum L. subsp. durum): Bacillus inaquosorum TSO22

- Assessment of the recurrent mutagenesis efficacy of sesame crosses followed by isolation and evaluation of promising genetic resources for use in future breeding programs

- Fostering cocoa industry resilience: A collaborative approach to managing farm gate price fluctuations in West Sulawesi, Indonesia

- Field investigation of component failures for selected farm machinery used in small rice farming operations

- Near-infrared technology in agriculture: Rapid, simultaneous, and non-destructive determination of inner quality parameters on intact coffee beans

- The synergistic application of sucrose and various LED light exposures to enhance the in vitro growth of Stevia rebaudiana (Bertoni)

- Weather index-based agricultural insurance for flower farmers: Willingness to pay, sales, and profitability perspectives

- Meta-analysis of dietary Bacillus spp. on serum biochemical and antioxidant status and egg quality of laying hens

- Biochemical characterization of trypsin from Indonesian skipjack tuna (Katsuwonus pelamis) viscera

- Determination of C-factor for conventional cultivation and soil conservation technique used in hop gardens

- Empowering farmers: Unveiling the economic impacts of contract farming on red chilli farmers’ income in Magelang District, Indonesia

- Evaluating salt tolerance in fodder crops: A field experiment in the dry land

- Labor productivity of lowland rice (Oryza sativa L.) farmers in Central Java Province, Indonesia

- Cropping systems and production assessment in southern Myanmar: Informing strategic interventions

- The effect of biostimulants and red mud on the growth and yield of shallots in post-unlicensed gold mining soil

- Effects of dietary Adansonia digitata L. (baobab) seed meal on growth performance and carcass characteristics of broiler chickens: A systematic review and meta-analysis

- Analysis and structural characterization of the vid-pisco market

- Pseudomonas fluorescens SP007s enhances defense responses against the soybean bacterial pustule caused by Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. glycines

- A brief investigation on the prospective of co-composted biochar as a fertilizer for Zucchini plants cultivated in arid sandy soil

- Supply chain efficiency of red chilies in the production center of Sleman Indonesia based on performance measurement system

- Investment development path for developed economies: Is agriculture different?

- Power relations among actors in laying hen business in Indonesia: A MACTOR analysis

- High-throughput digital imaging and detection of morpho-physiological traits in tomato plants under drought

- Converting compression ignition engine to dual-fuel (diesel + CNG) engine and experimentally investigating its performance and emissions

- Structuration, risk management, and institutional dynamics in resolving palm oil conflicts

- Spacing strategies for enhancing drought resilience and yield in maize agriculture

- Composition and quality of winter annual agrestal and ruderal herbages of two different land-use types

- Investigating Spodoptera spp. diversity, percentage of attack, and control strategies in the West Java, Indonesia, corn cultivation

- Yield stability of biofertilizer treatments to soybean in the rainy season based on the GGE biplot

- Evaluating agricultural yield and economic implications of varied irrigation depths on maize yield in semi-arid environments, at Birfarm, Upper Blue Nile, Ethiopia

- Chemometrics for mapping the spatial nitrate distribution on the leaf lamina of fenugreek grown under varying nitrogenous fertilizer doses

- Pomegranate peel ethanolic extract: A promising natural antioxidant, antimicrobial agent, and novel approach to mitigate rancidity in used edible oils

- Transformative learning and engagement with organic farming: Lessons learned from Indonesia

- Tourism in rural areas as a broader concept: Some insights from the Portuguese reality

- Assessment enhancing drought tolerance in henna (Lawsonia inermis L.) ecotypes through sodium nitroprusside foliar application

- Edible insects: A survey about perceptions regarding possible beneficial health effects and safety concerns among adult citizens from Portugal and Romania

- Phenological stages analysis in peach trees using electronic nose

- Harvest date and salicylic acid impact on peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.) properties under different humidity conditions

- Hibiscus sabdariffa L. petal biomass: A green source of nanoparticles of multifarious potential

- Use of different vegetation indices for the evaluation of the kinetics of the cherry tomato (Solanum lycopersicum var. cerasiforme) growth based on multispectral images by UAV

- First evidence of microplastic pollution in mangrove sediments and its ingestion by coral reef fish: Case study in Biawak Island, Indonesia

- Physical and textural properties and sensory acceptability of wheat bread partially incorporated with unripe non-commercial banana cultivars

- Cereibacter sphaeroides ST16 and ST26 were used to solubilize insoluble P forms to improve P uptake, growth, and yield of rice in acidic and extreme saline soil

- Avocado peel by-product in cattle diets and supplementation with oregano oil and effects on production, carcass, and meat quality

- Optimizing inorganic blended fertilizer application for the maximum grain yield and profitability of bread wheat and food barley in Dawuro Zone, Southwest Ethiopia

- The acceptance of social media as a channel of communication and livestock information for sheep farmers

- Adaptation of rice farmers to aging in Thailand

- Combined use of improved maize hybrids and nitrogen application increases grain yield of maize, under natural Striga hermonthica infestation

- From aquatic to terrestrial: An examination of plant diversity and ecological shifts

- Statistical modelling of a tractor tractive performance during ploughing operation on a tropical Alfisol

- Participation in artisanal diamond mining and food security: A case study of Kasai Oriental in DR Congo

- Assessment and multi-scenario simulation of ecosystem service values in Southwest China’s mountainous and hilly region

- Analysis of agricultural emissions and economic growth in Europe in search of ecological balance

- Bacillus thuringiensis strains with high insecticidal activity against insect larvae of the orders Coleoptera and Lepidoptera

- Technical efficiency of sugarcane farming in East Java, Indonesia: A bootstrap data envelopment analysis

- Comparison between mycobiota diversity and fungi and mycotoxin contamination of maize and wheat

- Evaluation of cultivation technology package and corn variety based on agronomy characters and leaf green indices

- Exploring the association between the consumption of beverages, fast foods, sweets, fats, and oils and the risk of gastric and pancreatic cancers: Findings from case–control study

- Phytochemical composition and insecticidal activity of Acokanthera oblongifolia (Hochst.) Benth & Hook.f. ex B.D.Jacks. extract on life span and biological aspects of Spodoptera littoralis (Biosd.)

- Land use management solutions in response to climate change: Case study in the central coastal areas of Vietnam

- Evaluation of coffee pulp as a feed ingredient for ruminants: A meta-analysis

- Interannual variations of normalized difference vegetation index and potential evapotranspiration and their relationship in the Baghdad area

- Harnessing synthetic microbial communities with nitrogen-fixing activity to promote rice growth

- Agronomic and economic benefits of rice–sweetpotato rotation in lowland rice cropping systems in Uganda

- Response of potato tuber as an effect of the N-fertilizer and paclobutrazol application in medium altitude

- Bridging the gap: The role of geographic proximity in enhancing seed sustainability in Bandung District

- Evaluation of Abrams curve in agricultural sector using the NARDL approach

- Challenges and opportunities for young farmers in the implementation of the Rural Development Program 2014–2020 of the Republic of Croatia

- Yield stability of ten common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) genotypes at different sowing dates in Lubumbashi, South-East of DR Congo

- Effects of encapsulation and combining probiotics with different nitrate forms on methane emission and in vitro rumen fermentation characteristics

- Phytochemical analysis of Bienertia sinuspersici extract and its antioxidant and antimicrobial activities

- Evaluation of relative drought tolerance of grapevines by leaf fluorescence parameters

- Yield assessment of new streak-resistant topcross maize hybrids in Benin

- Improvement of cocoa powder properties through ultrasonic- and microwave-assisted alkalization

- Potential of ecoenzymes made from nutmeg (Myristica fragrans) leaf and pulp waste as bioinsecticides for Periplaneta americana

- Analysis of farm performance to realize the sustainability of organic cabbage vegetable farming in Getasan Semarang, Indonesia

- Revealing the influences of organic amendment-derived dissolved organic matter on growth and nutrient accumulation in lettuce seedlings (Lactuca sativa L.)

- Identification of viruses infecting sweetpotato (Ipomoea batatas Lam.) in Benin

- Assessing the soil physical and chemical properties of long-term pomelo orchard based on tree growth

- Investigating access and use of digital tools for agriculture among rural farmers: A case study of Nkomazi Municipality, South Africa

- Does sex influence the impact of dietary vitD3 and UVB light on performance parameters and welfare indicators of broilers?

- Design of intelligent sprayer control for an autonomous farming drone using a multiclass support vector machine

- Deciphering salt-responsive NB-ARC genes in rice transcriptomic data: A bioinformatics approach with gene expression validation

- Review Articles

- Impact of nematode infestation in livestock production and the role of natural feed additives – A review

- Role of dietary fats in reproductive, health, and nutritional benefits in farm animals: A review

- Climate change and adaptive strategies on viticulture (Vitis spp.)

- The false tiger of almond, Monosteira unicostata (Hemiptera: Tingidae): Biology, ecology, and control methods

- A systematic review on potential analogy of phytobiomass and soil carbon evaluation methods: Ethiopia insights

- A review of storage temperature and relative humidity effects on shelf life and quality of mango (Mangifera indica L.) fruit and implications for nutrition insecurity in Ethiopia

- Green extraction of nutmeg (Myristica fragrans) phytochemicals: Prospective strategies and roadblocks

- Potential influence of nitrogen fertilizer rates on yield and yield components of carrot (Dacus carota L.) in Ethiopia: Systematic review

- Corn silk: A promising source of antimicrobial compounds for health and wellness

- State and contours of research on roselle (Hibiscus sabdariffa L.) in Africa

- The potential of phosphorus-solubilizing purple nonsulfur bacteria in agriculture: Present and future perspectives

- Minor millets: Processing techniques and their nutritional and health benefits

- Meta-analysis of reproductive performance of improved dairy cattle under Ethiopian environmental conditions

- Review on enhancing the efficiency of fertilizer utilization: Strategies for optimal nutrient management

- The nutritional, phytochemical composition, and utilisation of different parts of maize: A comparative analysis

- Motivations for farmers’ participation in agri-environmental scheme in the EU, literature review

- Evolution of climate-smart agriculture research: A science mapping exploration and network analysis

- Short Communications

- Music enrichment improves the behavior and leukocyte profile of dairy cattle

- Effect of pruning height and organic fertilization on the morphological and productive characteristics of Moringa oleifera Lam. in the Peruvian dry tropics

- Corrigendum

- Corrigendum to “Bioinformatics investigation of the effect of volatile and non-volatile compounds of rhizobacteria in inhibiting late embryogenesis abundant protein that induces drought tolerance”

- Corrigendum to “Composition and quality of winter annual agrestal and ruderal herbages of two different land-use types”

- Special issue: Smart Agriculture System for Sustainable Development: Methods and Practices

- Construction of a sustainable model to predict the moisture content of porang powder (Amorphophallus oncophyllus) based on pointed-scan visible near-infrared spectroscopy

- FruitVision: A deep learning based automatic fruit grading system

- Energy harvesting and ANFIS modeling of a PVDF/GO-ZNO piezoelectric nanogenerator on a UAV

- Effects of stress hormones on digestibility and performance in cattle: A review

- Special Issue of The 4th International Conference on Food Science and Engineering (ICFSE) 2022 - Part II

- Assessment of omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acid profiles and ratio of omega-6/omega-3 of white eggs produced by laying hens fed diets enriched with omega-3 rich vegetable oil

- Special Issue on FCEM - International Web Conference on Food Choice & Eating Motivation - Part II

- Special Issue on FCEM – International Web Conference on Food Choice & Eating Motivation: Message from the editor

- Fruit and vegetable consumption: Study involving Portuguese and French consumers

- Knowledge about consumption of milk: Study involving consumers from two European Countries – France and Portugal