Abstract

Surface plasmons at an interface between dielectric and metal regions can in theory be made arbitrarily compact normal to the interface by introducing extreme anisotropy in the material parameters. We propose a metamaterial structure comprising a square array of gold cylinders and tune the filling factor to achieve the material parameters we seek. Theory is compared to a simulation wherein the unit cell dimensions of the metamaterial are shown to be the limiting factor in the degree of localisation achieved.

Surface plasmons exist at an interface between a metal, εm < 0, and dielectric, εd > 0 [1], [2], [3]. If these surface states have in-plane wave vectors kx, they are confined normal to the surface by imaginary wave vectors,

where we assume that the dielectric occupies the space z > 0, ωsp is the surface plasmon frequency and c0 is the velocity of light in free space. We have assumed isotropic media: εd, εm are the permittivities of the dielectric and metal, respectively. They are in general dependent on frequency. At lower values of kx, the surface plasmon is rather diffuse in extent, but at large values of k, the surface plasmon becomes compact and increasingly electrostatic in nature:

Transformation optics [4], [5], [6], [7] is a theory that relates distortions of geometry to redefined values of permittivity and permeability. For example, in our case, we seek to compress the surface plasmon normal to the surface. In the study by Kundtz et al. [7], we learn that if we compress the wave fields by a factor β (β < 1) so that the new imaginary wave vectors increase by a factor β−1, in order that the compressed wave fields continue to obey Maxwell’s equations, we must introduce new values of permittivity as follows,

with analogous formulas for the permeability. This formula solves our problem at a stroke, always provided of course that we can find suitably anisotropic materials. It is also possible to expand the surface plasmon by choosing β > 1 [8].

To solve the problem of finding permittivities tunable in the fashion required, we turn to metamaterials [9], [10], [11], [12], [13]. These are composite materials structured on a scale much less than the relevant wavelengths in the problem, whose properties owe more to their structure than to their chemical composition. Tuning the magnetic response is more of a problem because even metamaterials struggle with magnetism at optical frequencies. However, here, we appeal to the mainly electrostatic nature of the surface plasmon at higher values of kx and show that a high degree of compression can be achieved by tuning the electrical response alone.

Our target metamaterial structure is shown in Figure 1. In the first instance, we use a simple approximation to find the effective medium parameters of our structure, which we then check against COMSOL simulations. The Maxwell Garnett theory gives the following formula for the metamaterial parameters [14], [15],

where fm is the metal volume filling fraction of the cylinders. We model the metal with a Drude permittivity and the dielectric as vacuum,

with the metal parameters chosen to model gold. In the first instance, we shall neglect losses, γ = 0, but later when comparing to COMSOL simulations, loss is taken into account.

A two-dimensional square array of metallic cylinders much smaller than the relevant wavelengths, embedded in a dielectric. In the plane z = 0, there is an interface between two sets of cylinders. This is where the interface plasmon forms. We tune the volume fraction to achieve the desired properties of an effective medium shown on the right.

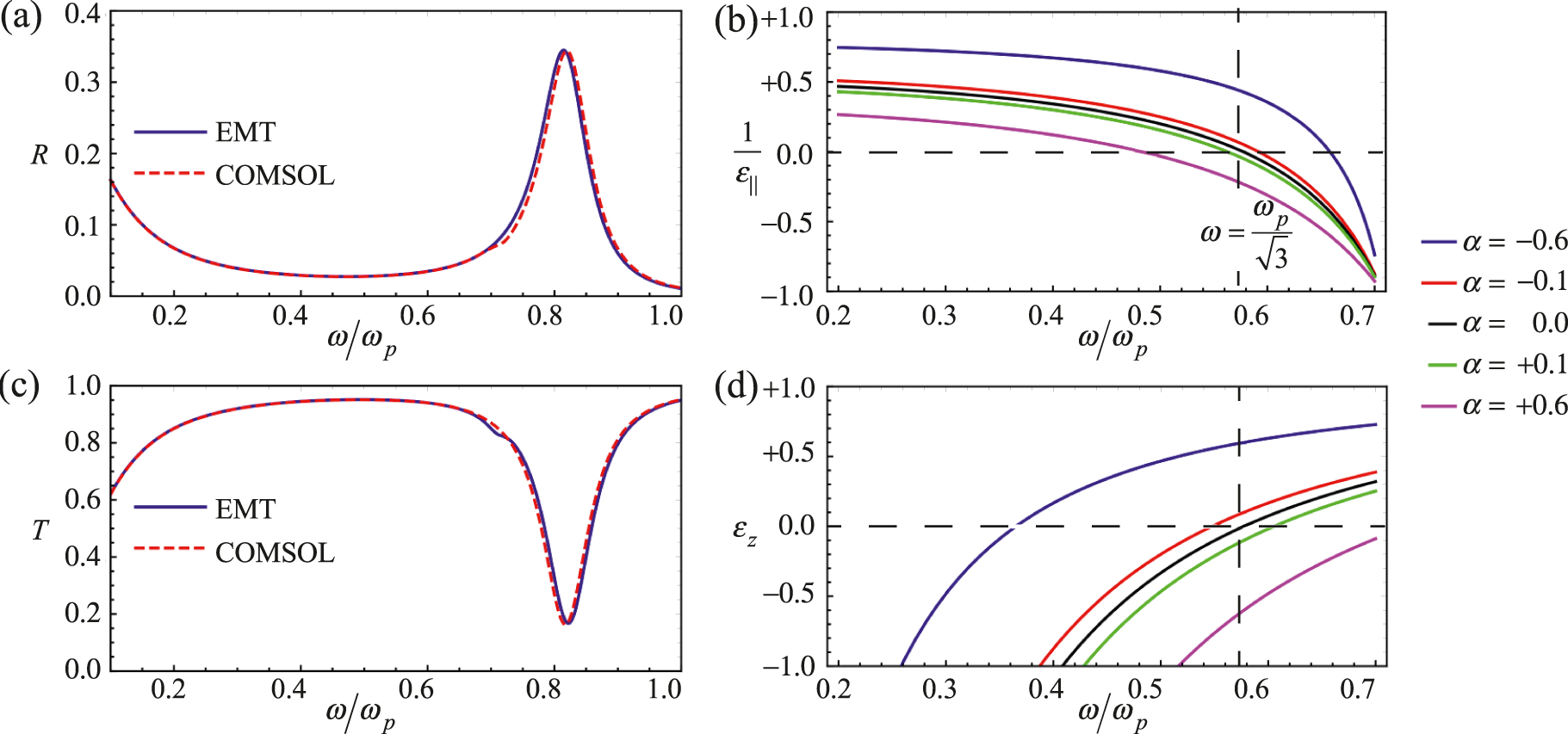

Although (3) is an approximation, it can be shown to be highly accurate [16]. Figure 2 compares a COMSOL simulation of transmission and reflection coefficients for the structure shown in Figure 1, with an effective medium calculation using the parameters given by the Maxwell Garnet formula.

(a) Reflection from and (c) transmission through one unit cell of a nanowire metamaterial with period 10 nm and filling ratio fm = 1/3, calculated with effective medium theory (EMT) theory and COMSOL. The incident angle is at 45° to the z-axis, and the electric field has both Ez and Ex components. The magnetic field has only a Hy component. (b)

The challenge is to design two metamaterials each with huge anisotropies, but one pair taking negative values and the other taking positive values. This will realize our requirements for compression of a surface plasmon at the interface between the two.

Recognizing that εd, εm have opposite signs, inspection of (3) shows that we can make the real part of εz very small by choice of

where we have recognized that εm < 0. We can arrange that the denominator takes a very small value by adjusting

we find that for α > 0, we have an extremely anisotropic metal, and for α < 0, we have an extremely anisotropic dielectric.

In Figure 2b and d, we plot the Maxwell Garnett formula for the metallic and dielectric metamaterial anisotropic permittivities for several values of α. When α = 0, the curves intersect at zero and a frequency of

Next, we present some calculations to demonstrate the feasibility of our theory.

We also need to recognize that the metamaterial concept only holds good on length scales greater than the metamaterial structure, which we take to be 10 nm.

Figure 3 shows dispersion of the surface plasmon trapped between the metametal and the metadielectric calculated for an effective medium corresponding to two media with filling factors defined by ±α. Shown on the same plot is the light line for the metadielectric. Dispersion curves to the right of this line represent surface plasmons trapped at the surface; to the left of this line, dispersion curves represent waves that are perfectly transmitted across the interface in the manner of a Brewster condition. This is a typical behaviour when a surface plasmon dispersion curve appears to cross the light line. For example, the α = ±0.1 surface plasmon exists between 0.56268 < ω/ωp < 0.57765. The pure metal-vacuum surface plasmon is shown for comparison. It disperses much more rapidly with frequency than the compressed surface plasmon and therefore has a much lower density of states. All dispersion curves are degenerate at

Dispersion of the surface plasmons for α = 0.1 and α = 0.6 together with dispersion of the pure metal-vacuum surface plasmon plotted against kx in units of m−1. The dotted lines show the associated light lines in the dielectric.

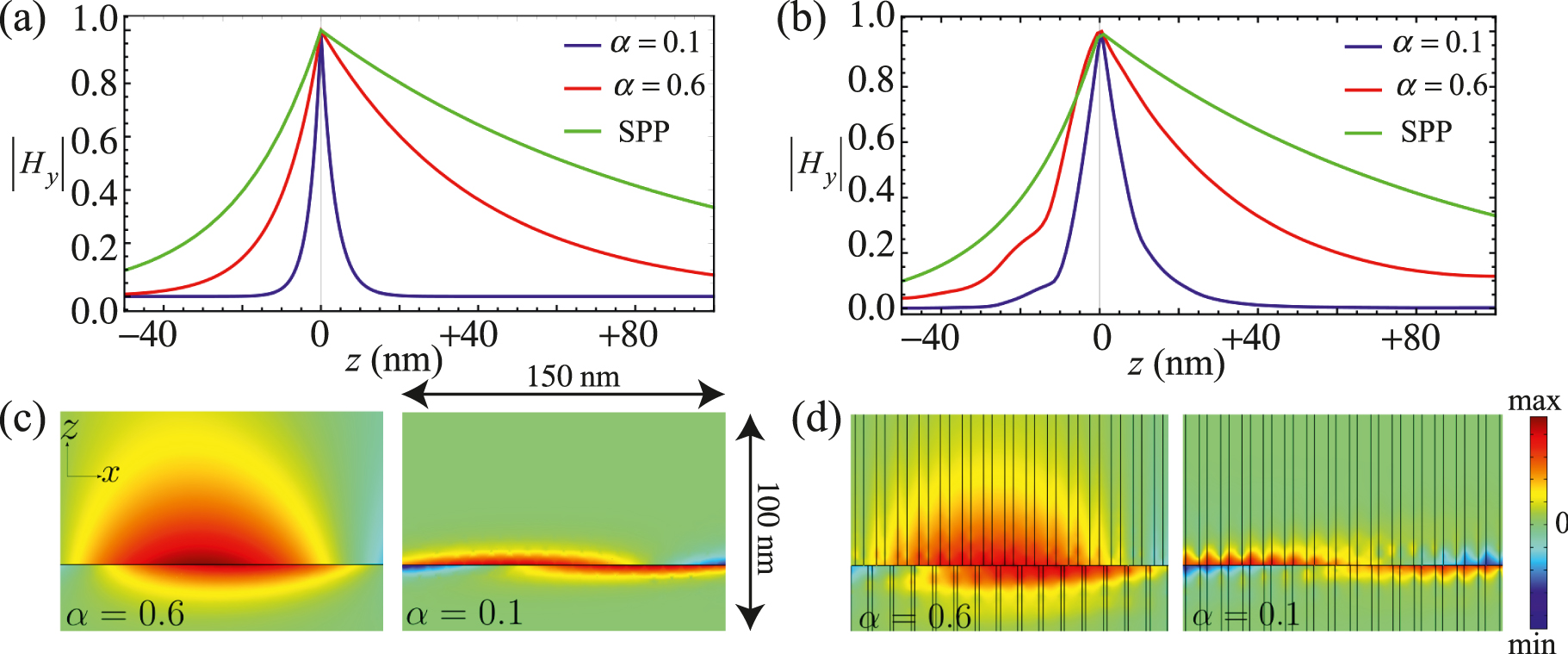

Figure 4a shows an interface surface state plotted as a function of distance from the interface calculated in the effective medium approximation. Compared to the surface plasmon existing between a pure metal and pure vacuum, we can see very large compression by a factor of about 20 when α = ±0.1. Furthermore, as noted in Figure 3, the density of states is greatly enhanced by the flattened dispersion of the interface surface plasmon.

(a) Modulus of the magnetic field for the interface plasmon calculated in the effective medium approximation at kx = 2.26 × 107 m−1 compared to a surface plasmon that exists between a pure metal and pure vacuum at the same frequency. (b) The same calculation but now deploying COMSOL on the metamaterial structure, lattice spacing a = 10 nm. (c) An effective medium calculation of the magnetic field distribution plotted in the vicinity of the interface. (d) The same calculation but now deploying COMSOL on the metamaterial structure and plotted in a plane taken through the centre of the cylinders. The surface mode is excited by a surface current along the x-direction at the interface, which makes the magnetic field discontinuous.

So far, we have worked in the effective medium approximation, but now, we make a more realistic test by including the microstructure of the metamaterial and the loss parameter γ = 0.329 eV, which so far, we have taken to be zero. Loss is also included in the effective medium calculation in Figure 4. Figure 4b presents a COMSOL simulation of a metamaterial structure in which the metal permittivity includes loss as described in (4), and the lattice period is 10 nm. At the interface, the two sets of cylinders on either side are coaxial with one other and touch at the interface. The pure metal/dielectric SPP is unchanged of course, but we see spreading of the metamaterial interface plasmon. This is mainly due to the finite dimensions of the metamaterial unit cell: on length scales <10 nm, the effective medium approximation breaks down. Nevertheless, our model metamaterial still shows substantial compression of the surface plasmon by about a factor of 7.

In conclusion, we have shown that in theory, interface surface plasmons can be arbitrarily compressed provided that the specified anisotropic material parameters can be realized. We proposed a metamaterial structure based on a square array of gold cylinders and showed how the design parameters can be tuned to approach the ideal anisotropic parameters for the metamaterials on each side of the interface. In practice, although substantial compression of the interface surface plasmon can be achieved, the extreme values predicted by an ideal theory are limited first by the finite unit cell of the metamaterial, which limits compression to no less than the unit cell dimensions, and secondly by metallic losses, which limit the compression of the density of states and hence also of the local density of states.

Funding source: Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation

Acknowledgements

F.Y. acknowledges the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation. J.B.P. and K.D. acknowledge funding from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation.

Author contribution: All the authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this submitted manuscript and approved submission.

Research funding: Funding from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation.

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare no conflicts of interest regarding this article.

References

[1] R. H. Ritchie, “Plasma losses by fast electrons in thin films,” Phys. Rev., vol. 106, pp. 874–881, 1957. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrev.106.874.Suche in Google Scholar

[2] W. L. Barnes, A. Dereux, and T. W. Ebbesen, “Surface plasmon subwavelength optics,” Nature, vol. 424, pp. 824–830, 2003. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature01937.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[3] S. A. Maier, Plasmonics: Fundamentals and Applications, New York, Springer Science & Business Media, 2007.10.1007/0-387-37825-1Suche in Google Scholar

[4] A. Ward and J. B. Pendry, “Refraction and geometry in Maxwell’s equations,” J. Mod. Opt., vol. 43, pp. 773–793, 1996. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500349608232782.Suche in Google Scholar

[5] J. B. Pendry, D. Schurig, and D. R. Smith, “Controlling electromagnetic fields,” Science, vol. 312, pp. 1780–1782, 2006. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1125907.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] U. Leonhardt, “Optical conformal mapping,” Science, vol. 312, pp. 1777–1780, 2006. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1126493.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[7] N. B. Kundtz, D. R. Smith, and J. B. Pendry, “Electromagnetic design with transformation optics,” Proc. IEEE, vol. 99, pp. 1622–1633, 2011. https://doi.org/10.1109/jproc.2010.2089664.Suche in Google Scholar

[8] F. Yang, S. Ma, K. Ding, S. Zhang, and J. B. Pendry, “Continuous topological transition from metal to dielectric,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., 2020, to appear. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2003171117.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[9] J. B. Pendry, A. J. Holden, D. J. Robbins, and W. J. Stewart, “Magnetism from conductors and enhanced non-linear phenomena,” IEEE Trans. Microw. Theor. Tech., vol. 47, pp. 2075–2084, 1999. https://doi.org/10.1109/22.798002.Suche in Google Scholar

[10] D. R. Smith, J. B. Pendry, and M. C. K. Wiltshire, “Metamaterials and negative refractive index,” Science, vol. 305, pp. 788–792, 2004. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1096796.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] J. B. Pendry, “Metamaterials and the control of electromagnetic fields”, in Coherence and Quantum Optics IX, N. P. Bigelow, J. H. Eberly and C. R. StroudJr., Eds., Washington, DC, OSA Publications, 2009, 2008, pp. 42–52.10.1364/CQO.2007.CMB2Suche in Google Scholar

[12] W. Cai and V. M. Shalaev, Optical Metamaterials, New York, Springer, 2010.10.1007/978-1-4419-1151-3Suche in Google Scholar

[13] A. Poddubny, I. Iorsh, P. Belov, and Y. Kivshar, “Hyperbolic metamaterials,” Nat. Photonics, vol. 7, pp. 948–957, 2013. https://doi.org/10.1038/nphoton.2013.243.Suche in Google Scholar

[14] S. I. Bozhevolnyi, L. Martin-Moreno, and F. Garcia-Vidal, Quantum Plasmonics, New York, NY, Springer, 2017.10.1007/978-3-319-45820-5Suche in Google Scholar

[15] J. Elser, R. Wangberg, V. A. Podolskiy, and E. E. Narimanov, “Nanowire metamaterials with extreme optical anisotropy,” Appl. Phys. Lett., vol. 89, p. 261102, 2006. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.2422893.Suche in Google Scholar

[16] D. R. Smith, S. Schultz, P. Markos, and C. M. Soukoulis, “Determination of effective permittivity and permeability of metamaterials from reflection and transmission coefficients,” Phys. Rev. B, vol. 65, p. 195104, 2002. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.65.195104.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2020 Fan Yang et al., published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Editorial

- Editorial

- Optoelectronics and Integrated Photonics

- Disorder effects in nitride semiconductors: impact on fundamental and device properties

- Ultralow threshold blue quantum dot lasers: what’s the true recipe for success?

- Waiting for Act 2: what lies beyond organic light-emitting diode (OLED) displays for organic electronics?

- Waveguide combiners for mixed reality headsets: a nanophotonics design perspective

- On-chip broadband nonreciprocal light storage

- High-Q nanophotonics: sculpting wavefronts with slow light

- Thermoelectric graphene photodetectors with sub-nanosecond response times at terahertz frequencies

- High-performance integrated graphene electro-optic modulator at cryogenic temperature

- Asymmetric photoelectric effect: Auger-assisted hot hole photocurrents in transition metal dichalcogenides

- Seeing the light in energy use

- Lasers, Active optical devices and Spectroscopy

- A high-repetition rate attosecond light source for time-resolved coincidence spectroscopy

- Fast laser speckle suppression with an intracavity diffuser

- Active optics with silk

- Nanolaser arrays: toward application-driven dense integration

- Two-dimensional spectroscopy on a THz quantum cascade structure

- Homogeneous quantum cascade lasers operating as terahertz frequency combs over their entire operational regime

- Toward new frontiers for terahertz quantum cascade laser frequency combs

- Soliton dynamics of ring quantum cascade lasers with injected signal

- Fiber Optics and Optical Communications

- Propagation stability in optical fibers: role of path memory and angular momentum

- Perspective on using multiple orbital-angular-momentum beams for enhanced capacity in free-space optical communication links

- Biomedical Photonics

- A fiber optic–nanophotonic approach to the detection of antibodies and viral particles of COVID-19

- Plasmonic control of drug release efficiency in agarose gel loaded with gold nanoparticle assemblies

- Metasurfaces for biomedical applications: imaging and sensing from a nanophotonics perspective

- Hyperbolic dispersion metasurfaces for molecular biosensing

- Fundamentals of Optics

- A Tutorial on the Classical Theories of Electromagnetic Scattering and Diffraction

- Reflectionless excitation of arbitrary photonic structures: a general theory

- Optimization Methods

- Multiobjective and categorical global optimization of photonic structures based on ResNet generative neural networks

- Machine learning–assisted global optimization of photonic devices

- Artificial neural networks for inverse design of resonant nanophotonic components with oscillatory loss landscapes

- Adjoint-optimized nanoscale light extractor for nitrogen-vacancy centers in diamond

- Topological Photonics

- Non-Hermitian and topological photonics: optics at an exceptional point

- Topological photonics: Where do we go from here?

- Topological nanophotonics for photoluminescence control

- Anomalous Anderson localization behavior in gain-loss balanced non-Hermitian systems

- Quantum computing, Quantum Optics, and QED

- Quantum computing and simulation

- NIST-certified secure key generation via deep learning of physical unclonable functions in silica aerogels

- Thomas–Reiche–Kuhn (TRK) sum rule for interacting photons

- Macroscopic QED for quantum nanophotonics: emitter-centered modes as a minimal basis for multiemitter problems

- Generation and dynamics of entangled fermion–photon–phonon states in nanocavities

- Polaritonic Tamm states induced by cavity photons

- Recent progress in engineering the Casimir effect – applications to nanophotonics, nanomechanics, and chemistry

- Enhancement of rotational vacuum friction by surface photon tunneling

- Plasmonics and Polaritonics

- Shrinking the surface plasmon

- Polariton panorama

- Scattering of a single plasmon polariton by multiple atoms for in-plane control of light

- A metasurface-based diamond frequency converter using plasmonic nanogap resonators

- Selective excitation of individual nanoantennas by pure spectral phase control in the ultrafast coherent regime

- Semiconductor quantum plasmons for high frequency thermal emission

- Origin of dispersive line shapes in plasmon-enhanced stimulated Raman scattering microscopy

- Epitaxial aluminum plasmonics covering full visible spectrum

- Metaoptics

- Metamaterials with high degrees of freedom: space, time, and more

- The road to atomically thin metasurface optics

- Active nonlocal metasurfaces

- Giant midinfrared nonlinearity based on multiple quantum well polaritonic metasurfaces

- Near-field plates and the near zone of metasurfaces

- High-efficiency metadevices for bifunctional generations of vectorial optical fields

- Printing polarization and phase at the optical diffraction limit: near- and far-field optical encryption

- Optical response of jammed rectangular nanostructures

- Dynamic phase-change metafilm absorber for strong designer modulation of visible light

- Arbitrary polarization conversion for pure vortex generation with a single metasurface

- Enhanced harmonic generation in gases using an all-dielectric metasurface

- Monolithic metasurface spatial differentiator enabled by asymmetric photonic spin-orbit interactions

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Editorial

- Editorial

- Optoelectronics and Integrated Photonics

- Disorder effects in nitride semiconductors: impact on fundamental and device properties

- Ultralow threshold blue quantum dot lasers: what’s the true recipe for success?

- Waiting for Act 2: what lies beyond organic light-emitting diode (OLED) displays for organic electronics?

- Waveguide combiners for mixed reality headsets: a nanophotonics design perspective

- On-chip broadband nonreciprocal light storage

- High-Q nanophotonics: sculpting wavefronts with slow light

- Thermoelectric graphene photodetectors with sub-nanosecond response times at terahertz frequencies

- High-performance integrated graphene electro-optic modulator at cryogenic temperature

- Asymmetric photoelectric effect: Auger-assisted hot hole photocurrents in transition metal dichalcogenides

- Seeing the light in energy use

- Lasers, Active optical devices and Spectroscopy

- A high-repetition rate attosecond light source for time-resolved coincidence spectroscopy

- Fast laser speckle suppression with an intracavity diffuser

- Active optics with silk

- Nanolaser arrays: toward application-driven dense integration

- Two-dimensional spectroscopy on a THz quantum cascade structure

- Homogeneous quantum cascade lasers operating as terahertz frequency combs over their entire operational regime

- Toward new frontiers for terahertz quantum cascade laser frequency combs

- Soliton dynamics of ring quantum cascade lasers with injected signal

- Fiber Optics and Optical Communications

- Propagation stability in optical fibers: role of path memory and angular momentum

- Perspective on using multiple orbital-angular-momentum beams for enhanced capacity in free-space optical communication links

- Biomedical Photonics

- A fiber optic–nanophotonic approach to the detection of antibodies and viral particles of COVID-19

- Plasmonic control of drug release efficiency in agarose gel loaded with gold nanoparticle assemblies

- Metasurfaces for biomedical applications: imaging and sensing from a nanophotonics perspective

- Hyperbolic dispersion metasurfaces for molecular biosensing

- Fundamentals of Optics

- A Tutorial on the Classical Theories of Electromagnetic Scattering and Diffraction

- Reflectionless excitation of arbitrary photonic structures: a general theory

- Optimization Methods

- Multiobjective and categorical global optimization of photonic structures based on ResNet generative neural networks

- Machine learning–assisted global optimization of photonic devices

- Artificial neural networks for inverse design of resonant nanophotonic components with oscillatory loss landscapes

- Adjoint-optimized nanoscale light extractor for nitrogen-vacancy centers in diamond

- Topological Photonics

- Non-Hermitian and topological photonics: optics at an exceptional point

- Topological photonics: Where do we go from here?

- Topological nanophotonics for photoluminescence control

- Anomalous Anderson localization behavior in gain-loss balanced non-Hermitian systems

- Quantum computing, Quantum Optics, and QED

- Quantum computing and simulation

- NIST-certified secure key generation via deep learning of physical unclonable functions in silica aerogels

- Thomas–Reiche–Kuhn (TRK) sum rule for interacting photons

- Macroscopic QED for quantum nanophotonics: emitter-centered modes as a minimal basis for multiemitter problems

- Generation and dynamics of entangled fermion–photon–phonon states in nanocavities

- Polaritonic Tamm states induced by cavity photons

- Recent progress in engineering the Casimir effect – applications to nanophotonics, nanomechanics, and chemistry

- Enhancement of rotational vacuum friction by surface photon tunneling

- Plasmonics and Polaritonics

- Shrinking the surface plasmon

- Polariton panorama

- Scattering of a single plasmon polariton by multiple atoms for in-plane control of light

- A metasurface-based diamond frequency converter using plasmonic nanogap resonators

- Selective excitation of individual nanoantennas by pure spectral phase control in the ultrafast coherent regime

- Semiconductor quantum plasmons for high frequency thermal emission

- Origin of dispersive line shapes in plasmon-enhanced stimulated Raman scattering microscopy

- Epitaxial aluminum plasmonics covering full visible spectrum

- Metaoptics

- Metamaterials with high degrees of freedom: space, time, and more

- The road to atomically thin metasurface optics

- Active nonlocal metasurfaces

- Giant midinfrared nonlinearity based on multiple quantum well polaritonic metasurfaces

- Near-field plates and the near zone of metasurfaces

- High-efficiency metadevices for bifunctional generations of vectorial optical fields

- Printing polarization and phase at the optical diffraction limit: near- and far-field optical encryption

- Optical response of jammed rectangular nanostructures

- Dynamic phase-change metafilm absorber for strong designer modulation of visible light

- Arbitrary polarization conversion for pure vortex generation with a single metasurface

- Enhanced harmonic generation in gases using an all-dielectric metasurface

- Monolithic metasurface spatial differentiator enabled by asymmetric photonic spin-orbit interactions