Abstract

Structured light has gained much interest in increasing communications capacity through the simultaneous transmission of multiple orthogonal beams. This paper gives a perspective on the current state of the art and future challenges, especially with regards to the use of multiple orbital angular momentum modes for system performance enhancement.

1 Introduction

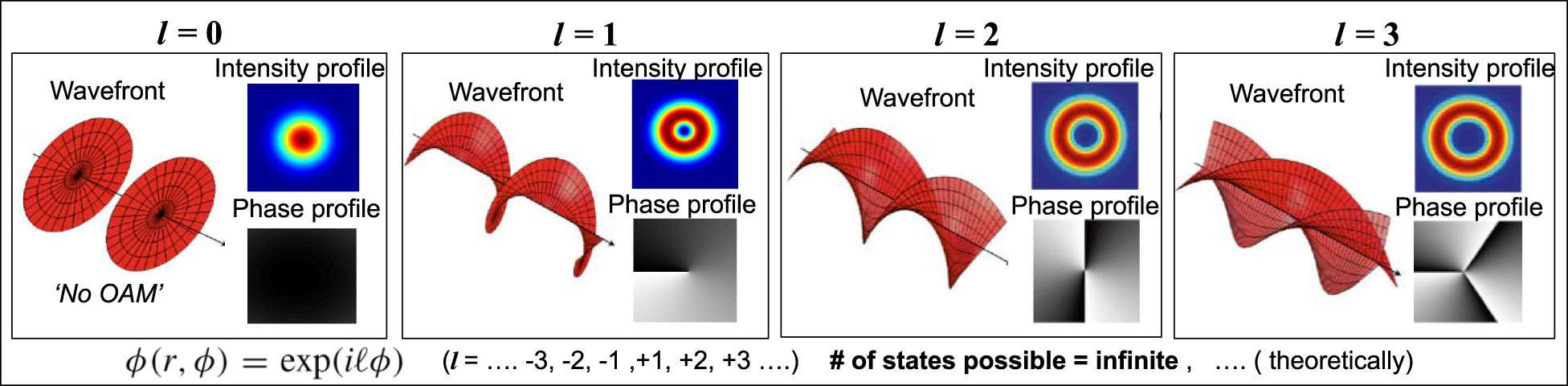

In 1992, Allen et al. [1] reported that orbital angular momentum (OAM) can be carried by an optical vortex beam. This beam has unique spatial structure, such that the amplitude has a ring-like doughnut profile and the phasefront “twists” in a helical fashion as it propagates. The number of 2π phase changes in the azimuthal direction is the OAM mode order, and beams with different OAM values can be orthogonal to each other. Such structured beams are a subset of the Laguerre–Gaussian (LGlp) modal basis set, which has two modal indices: (1) l represents the number of 2π phase shifts in the azimuthal direction and the size of the ring grows with l; and (2) p+1 represents the number of concentric amplitude rings (see Figure 1) [2]. This orthogonality enables multiple independent optical beams to be multiplexed, spatially copropagate, and be demultiplexed – all with minimal inherent cross talk [3], [4], [5].

The wavefronts, intensity profiles, and phase profiles of orbital angular momentum (OAM) modes l = 0, 1, 2, and 3. The OAM mode with a nonzero order has a donut shape intensity profile and helical phasefront. The size of the ring in the intensity profile grows with l. We note that p+1 represents the number of concentric amplitude rings and p=0 is shown.

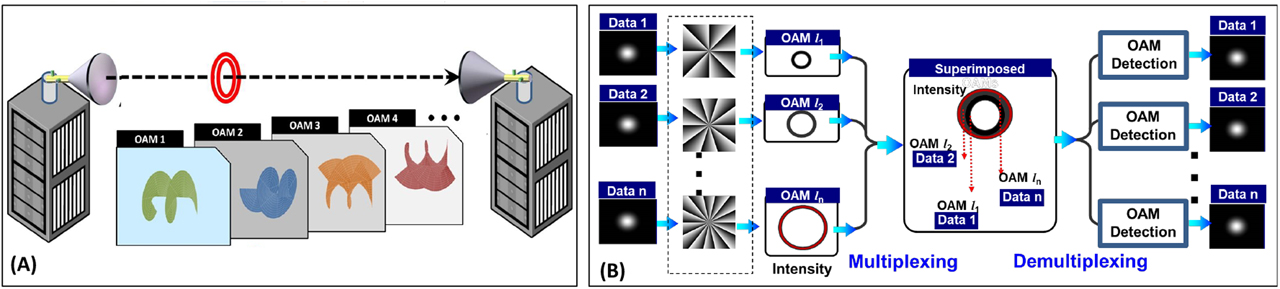

This orthogonality is of crucial benefit for a communications engineer. It implies that multiple independent data-carrying optical beams can be multiplexed and simultaneously transmitted in either free-space or fiber, thereby multiplying the system data capacity by the total number of beams (see Figure 2). Moreover, since all the beams are in the same frequency band, the system spectral efficiency (i.e., bits/s/Hz) is also increased. These multiplexed orthogonal OAM beams are a form of mode-division multiplexing (MDM), a subset of space-division multiplexing [4], [5], [6], [7].

Concept of orbital-angular-momentum (OAM)–multiplexed free-space optical (FSO) links.

(A) Multiple OAM beams are coaxially transmitted through free space. (B) Each orthogonal OAM beam carries an independent data stream.

MDM has similarities to wavelength-division multiplexing (WDM), in which multiple independent data-carrying optical beams of different wavelengths can be multiplexed and simultaneously transmitted. WDM revolutionized optical communication systems and is ubiquitously deployed worldwide. Importantly, MDM is generally compatible with and can complement WDM, such that each of many wavelengths can contain many orthogonal structured beams and thus dramatically increase data capacity [8].

The field of OAM-based optical communications: (i) is considered young and rich with scientific and technical challenges, (ii) holds promise for technological advances and applications, and (iii) has produced much research worldwide. Excitingly, the number of publications per year that deal with OAM for communications has grown significantly over the past several years (see Figure 3). Capacities, distances, and number of data channels have all increased [9], [10], and approaches for mitigating degrading effects have produced encouraging results.

![Figure 3: The orbital angular momentum (OAM) communications related publications yearly statistics (until July 2nd, 2020 from Google Scholar, provided by Guodong Xie) [11].](/document/doi/10.1515/nanoph-2020-0435/asset/graphic/j_nanoph-2020-0435_fig_003.jpg)

The orbital angular momentum (OAM) communications related publications yearly statistics (until July 2nd, 2020 from Google Scholar, provided by Guodong Xie) [11].

A key question remains as to how this young field may develop over the next decade. It is in this spirit that this article is aimed, taking an educated guess as to the subjective and relative merits of different aspects of this field. Specifically, these opinions try to address promising aspects that might be interesting to explore.

As far as context, this article will address a series of short subtopics and present our reasoned opinions. Moreover, due to the nature of this article, references will be provided for specific background, but the intent is to give a perspective rather than detail. For a basic treatment of OAM-multiplexed communications, the reader is welcome to read A.E. Willner, “Communication With a Twist”, IEEE Spectrum [12]. Finally and for the sake of readability, the article will generally assume OAM-multiplexed “free-space classical” optical communications as the basic default system. Separate subsections will be dedicated to topics that deviate from this system, such as for quantum communications (Section 7) or optical fiber transmission (Section 9).

2 Mitigation of modal coupling and channel crosstalk

A key issue in almost any MDM communication system is dealing with intermodal power coupling and deleterious inter-data-channel crosstalk. There are many causes of modal coupling and crosstalk, including the following for free-space OAM-multiplexed optical communication links:

Turbulence: Atmospheric turbulence can cause a phase differential at different cross-sectional locations of a propagating beam. Given this phase change distribution in a changing environment, power can couple from the intended mode into other modes dynamically (e.g., perhaps on the order of milliseconds) [13], [14].

Misalignment: Misalignment between the transmitter and receiver means that the receiver aperture is not coaxial with the incoming OAM beams. In order to operate an OAM-multiplexed link, one needs to know the mode that is being transmitted. A receiver aperture that captures power around the center of the beam will recover the full azimuthal phase change and know which l mode was transmitted. However, a limited-size receiver aperture that is off-axis will not recover the full phase change and inadvertently “think” that some power resides in other modes [15].

Divergence: Free-space beams of higher OAM orders diverge faster than lower-order beams, thus making it difficult to fully capture the higher-order OAM beam at a limited-sized receiver aperture. Power loss obviously occurs if the beam power is not fully captured, but even modal coupling can occur due to the truncation of the beam’s radial profile. This truncation can result in power being coupled to higher-order p modes [16], [17].

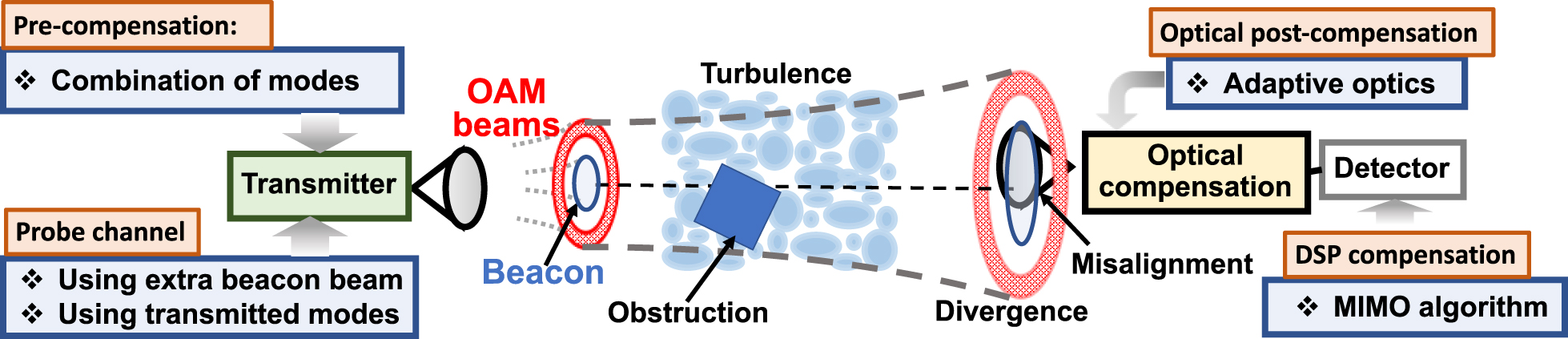

There are several approaches to potentially mitigate coupling and crosstalk in free-space OAM-multiplexed systems, including (see Figure 4):

Electrical digital signal processing (DSP): Crosstalk due to modal coupling has many similarities to crosstalk that occurs in multiple-transmitter-multiple-receiver (i.e., multiple-input multiple-output, MIMO) radio systems [18]. Multiple optical modes are similar to parallel radio frequency (RF) beams that experience crosstalk. Similar to electronic DSP that can undo much of the crosstalk in MIMO RF systems, these DSP approaches could also be used for mitigating OAM modal crosstalk [19].

Adaptive optics: Adaptive optics, such as by using digital micromirrors, spatial light modulators (SLMs) or multi-plane-light-converters (MPLCs), can mitigate modal crosstalk [20], [21], [22]. For example, if atmospheric turbulence causes a certain phase distortion on an optical beam, an SLM at the receiver can induce an inverse phase function to partially undo the effects of turbulence [21]. Typically, there could be a feedback loop, such that a data or probe beam is being monitored for dynamic changes and the new phase function is fed to an SLM.

Modifying transmitted beams: The modal structure of the transmitted beams themselves can be modified. In this approach: (a) the medium is probed by taking power measurements and determining the system modal coupling and channel crosstalk matrix, and (b) transmitting each beam with a combination of modes that represent the “inverse matrix”, such that the received data channels would have little crosstalk [23].

Various crosstalk compensation approaches in orbital-angular-momentum (OAM)–multiplexed links.

Currently, there is an increasing array of potential methods. As with most issues, cost and complexity will play a key role in determining which, if any, mitigating approach should be used.

It should also be mentioned that: (i) modal coupling “tends” to be higher to the adjacent modes, and (ii) separating data channels with a larger modal differential can help in alleviating the problem [14], [24], [25]. Of course, larger modal separation leads to larger beam divergence, so a trade-off analysis is usually recommended.

3 Free-space links

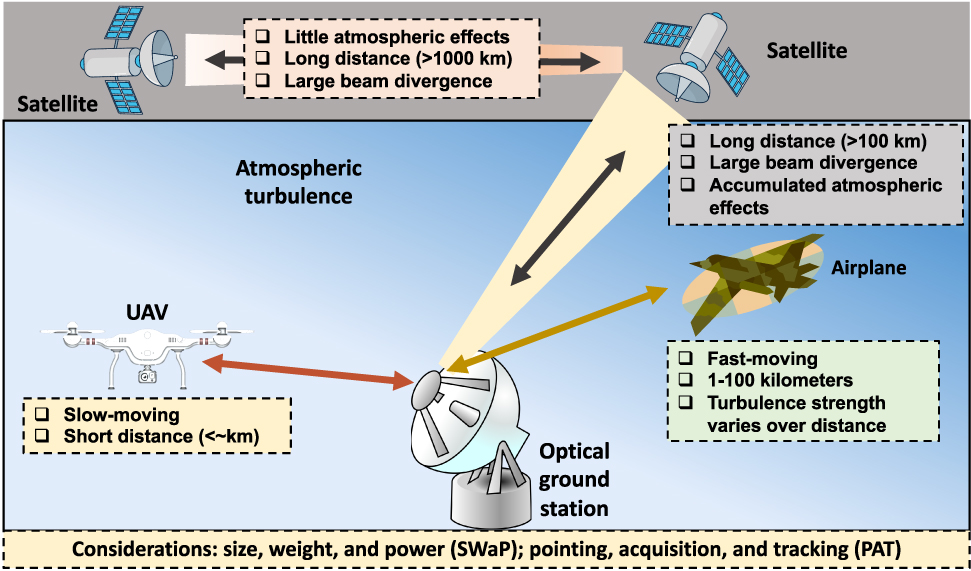

As compared to RF links, optics in general can provide: (a) more bandwidth and higher data capacity due to the higher carrier wave frequency, and (b) better beam directionality and lower divergence, thus making eavesdropping more difficult [15]. When incorporating MDM using OAM multiplexing, such optical links can potentially achieve capacity enhancement and increased difficulty to eavesdropping. This lower probability of intercept stems from the issue that any misalignment causes intermodal coupling, such that it is extremely difficult for an off-axis eavesdropper to recover the signals, and even an on-axis eavesdropper would need to know the modal properties in order to recover the data, again fairly difficult. In addition, these free-space applications share some common desirable characteristics, including: (1) low size, weight and power (SWaP), which can be alleviated by advances in integrated OAM devices [26]; and (2) accurate pointing, acquisition and tracking (PAT) systems, which helps limit modal coupling and crosstalk [15].

These advantages have generated interest in free-space MDM communications in the following scenarios:

Atmosphere: OAM multiplexing can potentially benefit communication to: (a) unmanned aerial vehicles, for which distances may be relatively short range and a key challenge is to miniaturize the optical hardware, and (b) airplanes and other flying platforms, for which distances may require turbulence compensation and highly accurate pointing/tracking [27], [28], [29] (see Figure 5).

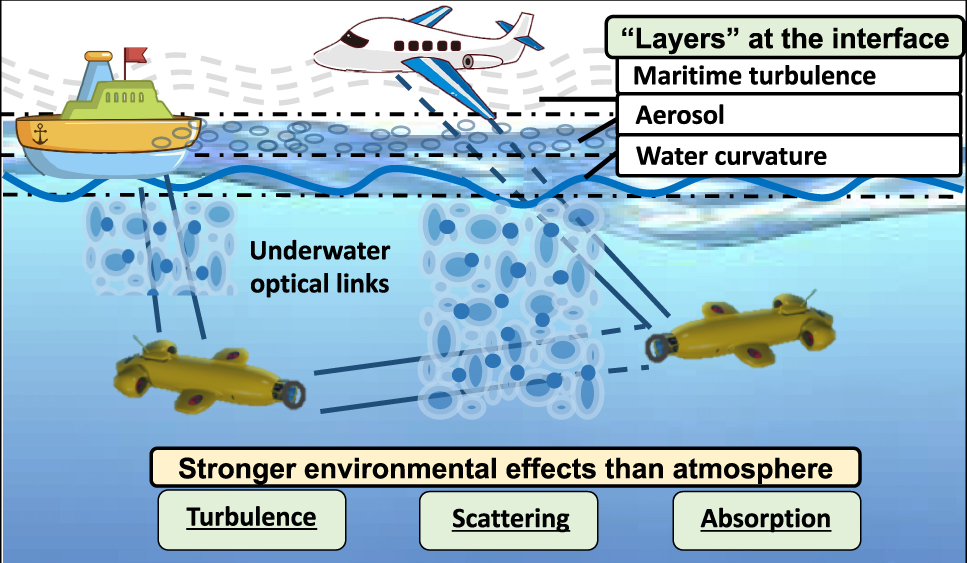

Underwater: Blue–green light has relatively low absorption in water, thereby potentially enabling high-capacity links over ∼100 m [30], [31] (see Figure 6). Note that radio waves simply do not propagate well underwater, and common underwater acoustic links have a very low bit rate. For underwater OAM links, challenges include loss, turbidity, scattering, currents, and turbulence. An interesting challenge is transmitting from above water to below the water, such that the structured optical beam would pass through inhomogeneous media surrounding the interface, including nonuniform aerosols above water, the dynamically changing geometry of the air–water interface, and bubbles/surf below the surface.

Orbital-angular-momentum (OAM)–multiplexed free-space optical airborne and satellite communications.

Challenges of different scenarios in underwater free-space optical communications.

4 “Why use OAM? Should both modal indices be used?”

Why use OAM?: Although there has been significant interest in OAM as a modal basis set for MDM communications, what is the rationale for choosing OAM over other types of modes? On a fundamental level, MDM requires that you can efficiently combine and separate different modes, so almost any complete orthogonal basis set could work. Indeed, many different types of modes were demonstrated in free-space and fiber, including Hermite–Gaussian (HG), LG, and linearly polarized (LP) modes [4], [5], [6, 34], [35], [36], [37].

In discussions with Robert Boyd and Miles Padgett [38], two practical issues seemed to emerge as to reasons that one “might” prefer OAM modes (as a subset of LG modes) to other modal basis sets:

OAM modes are round, and free-space optical components are readily available in round form.

It is important to maintain interchannel orthogonality and minimize crosstalk. This can be accomplished by fully capturing the specific parameter that defines the modal orthogonality. For a case in which different channels can be defined by different OAM l values, the channel and mode can be fully determined by azimuthally capturing a full 360° circle no matter the size of the round aperture [39].

Should both modal indices be used?: Structured beams that are from a modal basis set can generally be described by two modal indices, such that the beam can be fully described by these coordinates. For example, LG modes have l (azimuthal) and p (radial) components, whereas HG beams have n (horizontal) and m (vertical) components. However, the vast majority of publications concerning MDM-based free-space optical communications utilized only a change in a single modal index for the different OAM beams. Specifically, each beam commonly had a different l value but the same p=0 value [4], [5], [8]. This one-dimensional system can accommodate many orthogonal beams, but a system designer could also use the other beam modal index in order to possibly achieve a larger two-dimensional set of data channels. This two-dimensional approach was shown experimentally for LG and HG beams [6], [34]. It is important to note that a significant challenge is the sufficient capture of the beam at the receiver aperture to ensure accurate phase recovery and orthogonality along both indices [34].

5 Photonic integration and component ecosystem

Back in the 1980s, many WDM optical communications experiments were performed on large optical tables using expensive devices that were often either not meant for communications or one-off, custom-built components. The development of cost-effective, integrated devices was deemed important for WDM to be deployed widely.

The same could be said about OAM-multiplexed optical communications. Many systems experiments were performed on large optical tables using devices that were not originally meant for MDM optical communications. For the future of mode-multiplexing to thrive, R&D in integrated devices would seem to be of signaficants. Indeed, we have been keen advocates of photonic integrated circuits for OAM-based optical communications, as can be seen in these quotes from our prior papers:

Nature Photonics, Interview 2012 [40]: “Schemes for the generation, multiplexing and demultiplexing of OAM beams using superior SLMs or integrated devices would help to improve the maximum number of available OAM beams.”

Advances in Optics and Photonics 2015 [7]: “As was the case for many previous advances in optical communications, the future of OAM deployment would greatly benefit from advances in the enabling devices and subsystems (e.g., transmitters, (de)multiplexers, and receivers). Particularly with regard to integration, this represents significant opportunity to reduce cost and size and to also increase performance.”

System development would benefit from a full ecosystem of devices, including the above-mentioned components as well as: (i) amplifiers that uniformly provide gain to different modes, and (ii) waveguides that efficiently guide OAM modes with little modal coupling.

Key desirable features for these integrated devices include [26]: low insertion loss, high amplifier gain, uniform performance for different modes, high modal purity, low modal coupling and intermodal crosstalk, high efficiency for mode conversion, high dynamic range, small size, large wavelength range, and accommodation of high numbers of modes. Other functions that could be advantageous include: (i) fast tunability and reconfigurability covering a range of OAM modes, and (ii) integration of an OAM communication system-on-a-chip that incorporates a full transceiver.

Finally, experiments commonly use SLMs to tailor the beam structure, but commercially available SLMs are generally bulky, expensive, and slow. Our favorite wishlist device would be the creation of a “super” SLM that has low cost, small footprint, large dynamic range in amplitude and phase, wide spectral range, high modal purity, fast tunability (the faster the better, to even encode data bits), and high resolution [41], [42].

6 Novel beams

The excitement in this field originated by the ability to utilize orthogonal structured optical beams. However, there is much work in the fields of optics and photonics on several types of novel variations of optical beams (e.g., Airy and Bessel types), with more being explored at an exciting pace.

Over the next several years, it would not be surprising if novel beams are used to minimize certain system degrading effects. There have been initial results for some of these concepts, but a partial “wish list” for novel beams could be beams:

that are more resilient to modal coupling caused by turbulence and turbidity;

that have limited divergence in free space;

that are resilient to partial obstruction, such that their phase structure can “self-heal” (e.g., Bessel-type beams);

whose phase structure can readily be recovered even if the transmitter and receiver are misaligned.

7 Quantum communications

Another important advantage of OAM orthogonality is that one can use OAM mode order as a data encoding scheme [43], [44], [45], [46]. For example in the case of a quantum communication system, an individual photon can carry one of the many different OAM values; this is similar to digital data taking on one of many different amplitude values. A binary data symbol (i.e., one data bit) has two values of “0” and “1”, whereas an M-ary symbol may have many more possible values ranging from “0” to “M−1”. The number of data bits per unit time would be log2M. If each photon can be encoded with a specific OAM value from M possibilities, the photon efficiency in bits/photon can be increased. This has the potential to be quite useful for quantum communication systems which are typically photon “starved” and of which qubits commonly can be encoded on one of only two orthogonal polarization states [46] (see Figure 7).

![Figure 7: Concept of orbital-angular-momentum (OAM)–based quantum data encoding. Within each symbol period, a Gaussian photon is converted to one of the M OAM states, resulting in information encoding of up to log2M bit/photon. The accumulated intensity structure image is recorded using a single-photon sensitivity, low-noise–intensified charge-coupled device camera [46].](/document/doi/10.1515/nanoph-2020-0435/asset/graphic/j_nanoph-2020-0435_fig_007.jpg)

Concept of orbital-angular-momentum (OAM)–based quantum data encoding. Within each symbol period, a Gaussian photon is converted to one of the M OAM states, resulting in information encoding of up to log2M bit/photon. The accumulated intensity structure image is recorded using a single-photon sensitivity, low-noise–intensified charge-coupled device camera [46].

A larger alphabet for each qubit is, in general, highly desirable for enhancing system performance. However, there is much research needed to overcome the challenges in fielding an OAM-encoded quantum communication system, such as: (i) mitigating coupling among orthogonal states, and (ii) developing transmitters that can be tuned rapidly to encode each photon on one of many modes.

8 Different frequency ranges

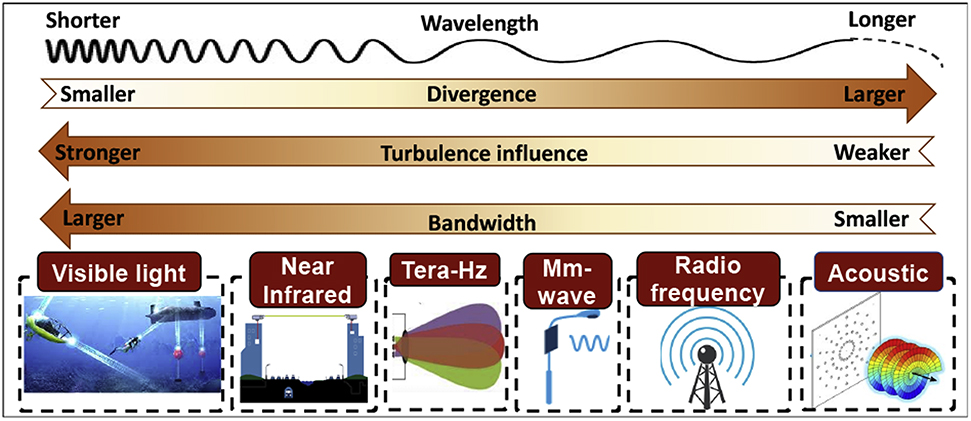

Separate from using optical beams, free-space communication links can take advantage of mode multiplexing in many other carrier-wave-frequency ranges to increase system capacity. For example, OAM can be manifest in many types of electromagnetic and mechanical waves (see Figure 8), and interesting reports have explored the use of OAM in millimeter, acoustic, and THz waves [].

Orbital angular momentum (OAM) applications in different frequencies for communications.

From a system designer’s perspective, there tends to be a trade-off in different frequency ranges:

Divergence: Lower frequencies have much higher beam divergence, exacerbating the problem of collecting enough of the beam to recover the data channels.

Interaction with Matter: Lower frequencies tend to have much lower interaction with matter, such that radio waves are less affected by atmospheric-turbulence-induced modal coupling than optical waves.

There are exciting developments in the millimeter-wave application space, for which industrial labs are increasingly engaging in R&D in order to significantly increase the potential capacity of fronthaul and backhaul links [47], [52], [53], [54], [55]. Advances in this area include the use of RF antenna arrays that are fabricated on printed-circuit boards [54]. For example, a multiantenna element ring can emit a millimeter-wave OAM beam by selectively exciting different antenna elements with a differential phase delay [55]. Moreover, multiple concentric rings can be fabricated, thereby emitting a larger number of multiplexed OAM beams [52], [53].

9 Optical fiber transmission

MDM can be achieved in both free-space and fiber, with much of the transmitter and receiver technology being similar. However, the channel medium is different, which gives rise to the following distinctions:

There is no beam divergence in light-guiding fiber.

The excitement around using MDM for capacity increase originally occurred primarily in the fiber transmission world, especially in research laboratories [35], [36], [60], [61]. There was much important work using LP modes as the modal set in fiber. However, since there was significant modal crosstalk when propagating through conventional-central-core few-mode fiber, MIMO-like DSP was used with impressive results to mitigate crosstalk [35], [60].

OAM has also been used as the modal basis set for fiber transmission, both for central-core and ring-core few-mode fibers [4], [36], [37], [62]. Importantly, the modal coupling itself can be reduced in the optical domain by utilizing specialty fiber that makes the propagation constants of different modes quite different, thus reducing intermodal coupling. Such fibers include ring-core and elliptical-core fibers [4], [36], [62], and 10’s of modes with low crosstalk have been demonstrated. These specialty fibers have produced exciting results, but they are structurally different than conventional fiber and thus require a little more resolve in order for them to be widely adopted.

10 Summary

Will OAM be widely deployed in communication systems? Not clear. However, our opinion is that the R&D community is producing excellent advances that, with all likelihood, will be valuable in some important aspects that use structured light.

Funding source: Vannevar Bush Faculty Fellowship sponsored by the Basic Research Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense (ASD) for Research and Engineering (R&E) and funded by the Office of Naval Research (ONR)

Award Identifier / Grant number: N00014-16-1-2813

Funding source: Defense Security Cooperation Agency

Award Identifier / Grant number: DSCA 4441006051

Funding source: Air Force Research Laboratory

Award Identifier / Grant number: FA8650-20-C-1105

Funding source: National Science Foundation (NSF)

Award Identifier / Grant number: ECCS-1509965

Funding source: Office of Naval Research through a MURI grant

Award Identifier / Grant number: N00014-20-1-2558

Author contribution: All the authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this submitted manuscript and approved submission.

Research funding: We acknowledge the generous supports from Vannevar Bush Faculty Fellowship sponsored by the Basic Research Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense (ASD) for Research and Engineering (R&E) and funded by the Office of Naval Research (ONR) (N00014-16-1-2813); Defense Security Cooperation Agency (DSCA 4441006051); Air Force Research Laboratory (FA8650-20-C-1105); National Science Foundation (NSF) (ECCS-1509965); and Office of Naval Research through a MURI grant (N00014-20-1-2558).

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare no conflicts of interest regarding this article.

References

[1] L. Allen, M. W. Beijersbergen, R. J. Spreeuw, and J. P. Woerdman, “Orbital angular momentum of light and the transformation of Laguerre–Gaussian laser modes,” Phys. Rev. A, vol. 45, no. 11, p. 8185, 1992. https://doi.org/10.1103/physreva.45.8185.Search in Google Scholar

[2] A. M. Yao and M. J. Padgett, “Orbital angular momentum: origins, behavior and applications,” Adv. Opt. Photonics, vol. 3, no. 2, pp. 161–204, 2011. https://doi.org/10.1364/aop.3.000161.Search in Google Scholar

[3] G. Gibson, J. Courtial, M. J. Padgett, et al., “Free-space information transfer using light beams carrying orbital angular momentum,” Optics Express, vol. 12, no. 22, pp. 5448–5456, 2004. https://doi.org/10.1364/opex.12.005448.Search in Google Scholar

[4] N. Bozinovic, Y. Yue, Y. Ren, et al., “Terabit-scale orbital angular momentum mode division multiplexing in fibers,” Science, vol. 340, no. 6140, pp. 1545–1548, 2013. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1237861.Search in Google Scholar

[5] J. Wang, J. Y. Yang, I. M. Fazal, et al., “Terabit free-space data transmission employing orbital angular momentum multiplexing,” Nat. Photon., vol. 6, no. 7, pp. 488–496, 2012. https://doi.org/10.1038/nphoton.2012.138.Search in Google Scholar

[6] K. Pang, H. Song, Z. Zhao, et al., “400-Gbit/s QPSK free-space optical communication link based on four-fold multiplexing of Hermite–Gaussian or Laguerre–Gaussian modes by varying both modal indices,” Opt. Lett., vol. 43, no. 16, pp. 3889–3892, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1364/ol.43.003889.Search in Google Scholar

[7] A. E. Willner, H. Huang, Y. Yan, et al., “Optical communications using orbital angular momentum beams,” Adv. Opt. Photonics, vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 66–106, 2015. https://doi.org/10.1364/aop.7.000066.Search in Google Scholar

[8] H. Huang, G. Xie, Y. Yan, et al., “100 Tbit/s free-space data link enabled by three-dimensional multiplexing of orbital angular momentum, polarization, and wavelength,” Opt. Lett., vol. 39, no. 2, pp. 197–200, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1364/ol.39.000197.Search in Google Scholar

[9] M. Krenn, J. Handsteiner, M. Fink, et al., “Twisted light transmission over 143 km,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A., vol. 113, no. 48, pp. 13648–13653, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1612023113.Search in Google Scholar

[10] J. Wang, S. Li, M. Luo, et al., “N-dimentional multiplexing link with 1.036-Pbit/s transmission capacity and 112.6-bit/s/Hz spectral efficiency using OFDM-8QAM signals over 368 WDM pol-muxed 26 OAM modes.” in The European Conference on Optical Communication (ECOC). IEEE, 2014, pp. 1–3.10.1109/ECOC.2014.6963934Search in Google Scholar

[11] G. Xie, Private Communication, 2020.Search in Google Scholar

[12] A. E. Willner, “Communication with a twist,” IEEE Spectrum, vol. 53, no. 8, pp. 34–39, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1109/mspec.2016.7524170.Search in Google Scholar

[13] L. C. Andrews and R. L. Phillips, Laser Beam Propagation through Random Media, SPIE, 2005. https://doi.org/10.1117/3.626196.Search in Google Scholar

[14] Y. Ren, H. Huang, G. Xie, et al., “Atmospheric turbulence effects on the performance of a free space optical link employing orbital angular momentum multiplexing,” Opt. Lett., vol. 38, no. 20, pp. 4062–4065, 2013. https://doi.org/10.1364/ol.38.004062.Search in Google Scholar

[15] G. Xie, L. Li, Y. Ren, et al., “Performance metrics and design considerations for a free-space optical orbital-angular-momentum–multiplexed communication link,” Optica, vol. 2, no. 4, pp. 357–365, 2015. https://doi.org/10.1364/optica.2.000357.Search in Google Scholar

[16] K. Pang, H. Song, X. Su, et al., “Simultaneous orthogonalizing and shaping of multiple LG beams to mitigate crosstalk and power loss by transmitting each of four data channels on multiple modes in a 400-Gbit/s free-space link,” in Optical Fiber Communication Conference (OFC), OSA, 2020, pp. W1G-2.10.1364/OFC.2020.W1G.2Search in Google Scholar

[17] Z. Xin, Z. Yaqin, R. Guanghui, et al., “Influence of finite apertures on orthogonality and completeness of Laguerre-Gaussian beams,” IEEE Access, vol. 6, pp. 8742–8754, 2018, https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2018.2806887.Search in Google Scholar

[18] P. J. Winzer and G. J. Foschini, “MIMO capacities and outage probabilities in spatially multiplexed optical transport systems,” Opt. Express, vol. 19, no. 17, pp. 16680–16696, 2011. https://doi.org/10.1364/oe.19.016680.Search in Google Scholar

[19] H. Huang, Y. Cao, G. Xie, et al., “Crosstalk mitigation in a free-space orbital angular momentum multiplexed communication link using 4 × 4 MIMO equalization,” Opt. Lett., vol. 39, no. 15, pp. 4360–4363, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1364/ol.39.004360.Search in Google Scholar

[20] G. A. Tyler, “Adaptive optics compensation for propagation through deep turbulence: a study of some interesting approaches,” Opt. Eng., vol. 52, no. 2, p. 021011, 2012. https://doi.org/10.1117/1.oe.52.2.021011.Search in Google Scholar

[21] Y. Ren, G. Xie, H. Huang, et al., “Adaptive-optics-based simultaneous pre- and post-turbulence compensation of multiple orbital-angular-momentum beams in a bidirectional free-space optical link,” Optica, vol. 1, no. 6, pp. 376–382, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1364/optica.1.000376.Search in Google Scholar

[22] N. K. Fontaine, R. Ryf, H. Chen, D. T. Neilson, K. Kim, and J. Carpenter, “Laguerre–Gaussian mode sorter,” Nat. Commun., vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 1–7, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-09840-4.Search in Google Scholar

[23] H. Song, H. Song, R. Zhang, et al., “Experimental mitigation of atmospheric turbulence effect using pre-signal combining for uni- and bi-directional free-space optical links with two 100-Gbit/s OAM-multiplexed channels,” J. Lightwave Technol., vol. 38, no. 1, pp. 82–89, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1109/jlt.2019.2933460.Search in Google Scholar

[24] J. A. Anguita, M. A. Neifeld, and B. V. Vasic, “Turbulence-induced channel crosstalk in an orbital angular momentum-multiplexed free-space optical link,” Appl. Opt., vol. 47, no. 13, pp. 2414–2429, 2008. https://doi.org/10.1364/ao.47.002414.Search in Google Scholar

[25] N. Chandrasekaran and J. H. Shapiro, “Photon information efficient communication through atmospheric turbulence—part I: channel model and propagation statistics,” J. Lightwave Technol., vol. 32, no. 6, pp. 1075–1087, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1109/jlt.2013.2296851.Search in Google Scholar

[26] A. E. Willner, “Advances in components and integrated devices for OAM-based systems,” Invited Tutorial in Conference on Lasers and Electro-Optics (CLEO), 2018, OSA, pp. Stu3B.1.Search in Google Scholar

[27] S. S. Muhammad, T. Plank, E. Leitgeb, et al., “Challenges in establishing free space optical communications between flying vehicles,” in 6th Int’l Symposium on Communication Systems, Networks and Digital Signal Processing, IEEE, 2008, pp. 82–86.10.1109/CSNDSP.2008.4610721Search in Google Scholar

[28] A. Kaadan, H. Refai, and P. Lopresti, “Spherical FSO receivers for UAV communication: geometric coverage models,” IEEE Trans. Aero. Electron. Syst., vol. 52, no. 5, pp. 2157–2167, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1109/taes.2016.150346.Search in Google Scholar

[29] L. Li, R. Zhang, Z. Zhao, et al., “High-capacity free-space optical communications between a ground transmitter and a ground receiver via a UAV using multiplexing of multiple orbital-angular-momentum beams,” Sci. Rep., vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 1–2, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-17580-y.Search in Google Scholar

[30] J. Baghdady, K. Miller, K. Morgan, et al., “Multi-gigabit/s underwater optical communication link using orbital angular momentum multiplexing,” Opt. Express, vol. 24, no. 9, pp. 9794–9805, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1364/oe.24.009794.Search in Google Scholar

[31] Y. Ren, L. Li, Z. Wang, et al., “Orbital angular momentum-based space division multiplexing for high-capacity underwater optical communications,” Sci. Rep., vol. 6, p. 33306, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep33306.Search in Google Scholar

[32] R. Fields, C. Lunde, R. Wong, et al., “NFIRE-to-TerraSAR-X laser communication results: satellite pointing, disturbances, and other attributes consistent with successful performance,” in Sensors and Systems for Space Applications III, vol. 7330, International Society for Optics and Photonics, 2009, p. 73300Q.10.1117/12.820393Search in Google Scholar

[33] F. Heine, G. Mühlnikel, H. Zech, S. Philipp-May, and R. Meyer, “The European Data Relay System, high speed laser based data links,” in 2014 7th Advanced Satellite Multimedia Systems Conference and the 13th Signal Processing for Space Communications Workshop (ASMS/SPSC), IEEE, 2014, pp. 284–286.10.1109/ASMS-SPSC.2014.6934556Search in Google Scholar

[34] G. Xie, Y. Ren, Y. Yan, et al., “Experimental demonstration of a 200-Gbit/s free-space optical link by multiplexing Laguerre–Gaussian beams with different radial indices,” Opt. Lett., vol. 41, no. 15, pp. 3447–3450, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1364/ol.41.003447.Search in Google Scholar

[35] R. Ryf, S. Randel, A. H. Gnauck, et al., “Mode-division multiplexing over 96 km of few-mode fiber using coherent 6 × 6 MIMO processing,” J. Lightwave Technol., vol. 30, no. 4, pp. 521–531, 2011. https://doi.org/10.1109/JLT.201.Search in Google Scholar

[36] D. J. Richardson, J. M. Fini, and L. E. Nelson, “Space-division multiplexing in optical fibres,” Nat. Photon., vol. 7, no. 5, pp. 354–362, 2013. https://doi.org/10.1038/nphoton.2013.94.Search in Google Scholar

[37] B. Ndagano, R. Brüning, M. McLaren, M. Duparré, and A. Forbes, “Fiber propagation of vector modes,” Opt. Express, vol. 23, no. 13, pp. 17330–17336, 2015. https://doi.org/10.1364/oe.23.017330.Search in Google Scholar

[38] R. W. Boyd and M. J. Padgett, Private Communication, 2020.Search in Google Scholar

[39] S. Restuccia, D. Giovannini, G. Gibson, and M. J. Padgett, “Comparing the information capacity of Laguerre–Gaussian and Hermite–Gaussian modal sets in a finite-aperture system,” Opt. Express, vol. 24, pp. 27127–27136, 2016, https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.24.027127.Search in Google Scholar

[40] O. Graydon, “Interview: a new twist for communications,” Nat. Photon., vol. 6, p. 498, 2012. https://doi.org/10.1038/nphoton.2012.151.Search in Google Scholar

[41] J. Lin, P. Genevet, M. A. Kats, N. Antoniou, and F. Capasso, “Nanostructured holograms for broadband manipulation of vector beams,” Nano Lett., vol. 13, no. 9, pp. 4269–4274, 2013. https://doi.org/10.1021/nl402039y.Search in Google Scholar

[42] V. Liu, D. A. B. Miller, and S. Fan, “Ultra-compact photonic crystal waveguide spatial mode converter and its connection to the optical diode effect,” Opt. Express, vol. 20, pp. 28388–28397, 2012, https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.20.028388.Search in Google Scholar

[43] M. Mafu, A. Dudley, S. Goyal, et al., “Higher-dimensional orbital-angular-momentum-based quantum key distribution with mutually unbiased bases,” Phys. Rev. A, vol. 88, no. 3, p. 032305, 2013. https://doi.org/10.1103/physreva.88.032305.Search in Google Scholar

[44] M. Mirhosseini, O. S. Magaña-Loaiza, M. N. O’Sullivan, et al., “High-dimensional quantum cryptography with twisted light,” New J. Phys., vol. 17, no. 3, p. 033033, 2015. https://doi.org/10.1088/1367-2630/17/3/033033.Search in Google Scholar

[45] C. Liu, K. Pang, Z. Zhao, et al., “Single-end adaptive optics compensation for emulated turbulence in a bi-directional 10-Mbit/s per channel free-space quantum communication link using OAM encoding,” Research, vol. 2019, p. 8326701, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/8326701.Search in Google Scholar

[46] M. Erhard, R. Fickler, M. Krenn, and A. Zeilinger, “Twisted photons: new quantum perspectives in high dimensions,” Light Sci. Appl., vol. 7, no. 3, p. 17146, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1038/lsa.2017.146.Search in Google Scholar

[47] Y. Yan, G. Xie, M. P. Lavery, et al., “High-capacity millimetre-wave communications with orbital angular momentum multiplexing,” Nat. Commun., vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 1–9, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms5876.Search in Google Scholar

[48] C. Shi, M. Dubois, Y. Wang, and X. Zhang, “High-speed acoustic communication by multiplexing orbital angular momentum,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A., vol. 114, no. 28, pp. 7250–7253, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1704450114.Search in Google Scholar

[49] Z. Zhao, R. Zhang, H. Song, et al., “Fundamental system-degrading effects in THz communications using multiple OAM beams with turbulence,” in 2020 IEEE International Conference on Communications (ICC), IEEE, 2020, pp. WC24-4.10.1109/ICC40277.2020.9149201Search in Google Scholar

[50] X. Wei, L. Zhu, Z. Zhang, K. Wang, J. Liu, and J. Wang, “Orbit angular momentum multiplexing in 0.1-THz free-space communication via 3D printed spiral phase plates,” in 2014 Conference on Lasers and Electro-Optics (CLEO)-Laser Science to Photonic Applications, IEEE, 2014, pp. STu2F.2.10.1364/CLEO_SI.2014.STu2F.2Search in Google Scholar

[51] C. Liu, X. Wei, L. Niu, K. Wang, Z. Yang, and J. Liu, “Discrimination of orbital angular momentum modes of the terahertz vortex beam using a diffractive mode transformer,” Opt. Express, vol. 24, no. 12, pp. 12534–12541, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1364/oe.24.012534.Search in Google Scholar

[52] H. Sasaki, D. Lee, H. Fukumoto, et al., “Experiment on over-100-Gbps wireless transmission with OAM-MIMO multiplexing system in 28-GHz band,” in IEEE Global Communications Conference, IEEE, 2018, pp. 1–6.10.1109/GLOCOM.2018.8647361Search in Google Scholar

[53] H. Sasaki, Y. Yagi, T. Yamada, and D. Lee, “Field experimental demonstration on OAM-MIMO wireless transmission on 28 GHz band,” in 2019 IEEE Globecom Workshops (GC Workshops), IEEE, 2019, pp. 1–4.10.1109/GCWkshps45667.2019.9024684Search in Google Scholar

[54] Z. Zhao, Y. Yan, L. Li, et al., “A dual-channel 60 GHz communications link using patch antenna arrays to generate data-carrying orbital-angular-momentum beams,” in IEEE International Conference on Communications (ICC), IEEE, 2016, pp. 1–6.10.1109/ICC.2016.7511413Search in Google Scholar

[55] G. Xie, Z. Zhao, Y. Yan, et al., “Demonstration of tunable steering and multiplexing of two 28 GHz data carrying orbital angular momentum beams using antenna array,” Sci. Rep., vol. 6, p. 37078, 2016, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep37078.Search in Google Scholar

[56] K. I. Kitayama and N. P. Diamantopoulos, “Few-mode optical fibers: original motivation and recent progress,” IEEE Commun. Mag., vol. 55, no. 8, pp. 163–169, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1109/mcom.2017.1600876.Search in Google Scholar

[57] P. J. Winzer, “Making spatial multiplexing a reality,” Nat. Photon., vol. 8, no. 5, pp. 345–348, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1038/nphoton.2014.58.Search in Google Scholar

[58] R. Zhang, H. Song, H. Song, et al., “Utilizing adaptive optics to mitigate intra-modal-group power coupling of graded-index few-mode fiber in a 200-Gbit/s mode-division-multiplexed link,” Opt. Letters, vol. 45, no. 13, pp. 3577–3580, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1364/OL.394307.Search in Google Scholar

[59] J. Carpenter, B. C. Thomsen, T. D. Wilkinson, “Degenerate mode-group division multiplexing.” J. Lightwave Technol., vol. 30, no. 24, pp. 3946–3952, 2012, https://doi.org/10.1109/JLT.2012.2206562.Search in Google Scholar

[60] S. Randel, R. Ryf, A. Sierra, et al., “6 × 56-Gb/s mode-division multiplexed transmission over 33-km few-mode fiber enabled by 6 × 6 MIMO equalization,” Opt. Express, vol. 19, no. 17, pp. 16697–16707, 2011. https://doi.org/10.1364/oe.19.016697.Search in Google Scholar

[61] S. Bae, Y. Jung, B. G. Kim, and Y. C. Chung, “Compensation of mode crosstalk in MDM system using digital optical phase conjugation,” IEEE Photon. Technol. Lett., vol. 31, no. 10, pp. 739–742, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1109/lpt.2019.2906403.Search in Google Scholar

[62] C. Brunet, P. Vaity, Y. Messaddeq, S. LaRochelle, and L. A. Rusch, “Design, fabrication and validation of an OAM fiber supporting 36 states,” Opt. Express, vol. 22, no. 21, pp. 26117–26127, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1364/oe.22.026117.Search in Google Scholar

© 2020 Alan E. Willner and Cong Liu, published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Editorial

- Editorial

- Optoelectronics and Integrated Photonics

- Disorder effects in nitride semiconductors: impact on fundamental and device properties

- Ultralow threshold blue quantum dot lasers: what’s the true recipe for success?

- Waiting for Act 2: what lies beyond organic light-emitting diode (OLED) displays for organic electronics?

- Waveguide combiners for mixed reality headsets: a nanophotonics design perspective

- On-chip broadband nonreciprocal light storage

- High-Q nanophotonics: sculpting wavefronts with slow light

- Thermoelectric graphene photodetectors with sub-nanosecond response times at terahertz frequencies

- High-performance integrated graphene electro-optic modulator at cryogenic temperature

- Asymmetric photoelectric effect: Auger-assisted hot hole photocurrents in transition metal dichalcogenides

- Seeing the light in energy use

- Lasers, Active optical devices and Spectroscopy

- A high-repetition rate attosecond light source for time-resolved coincidence spectroscopy

- Fast laser speckle suppression with an intracavity diffuser

- Active optics with silk

- Nanolaser arrays: toward application-driven dense integration

- Two-dimensional spectroscopy on a THz quantum cascade structure

- Homogeneous quantum cascade lasers operating as terahertz frequency combs over their entire operational regime

- Toward new frontiers for terahertz quantum cascade laser frequency combs

- Soliton dynamics of ring quantum cascade lasers with injected signal

- Fiber Optics and Optical Communications

- Propagation stability in optical fibers: role of path memory and angular momentum

- Perspective on using multiple orbital-angular-momentum beams for enhanced capacity in free-space optical communication links

- Biomedical Photonics

- A fiber optic–nanophotonic approach to the detection of antibodies and viral particles of COVID-19

- Plasmonic control of drug release efficiency in agarose gel loaded with gold nanoparticle assemblies

- Metasurfaces for biomedical applications: imaging and sensing from a nanophotonics perspective

- Hyperbolic dispersion metasurfaces for molecular biosensing

- Fundamentals of Optics

- A Tutorial on the Classical Theories of Electromagnetic Scattering and Diffraction

- Reflectionless excitation of arbitrary photonic structures: a general theory

- Optimization Methods

- Multiobjective and categorical global optimization of photonic structures based on ResNet generative neural networks

- Machine learning–assisted global optimization of photonic devices

- Artificial neural networks for inverse design of resonant nanophotonic components with oscillatory loss landscapes

- Adjoint-optimized nanoscale light extractor for nitrogen-vacancy centers in diamond

- Topological Photonics

- Non-Hermitian and topological photonics: optics at an exceptional point

- Topological photonics: Where do we go from here?

- Topological nanophotonics for photoluminescence control

- Anomalous Anderson localization behavior in gain-loss balanced non-Hermitian systems

- Quantum computing, Quantum Optics, and QED

- Quantum computing and simulation

- NIST-certified secure key generation via deep learning of physical unclonable functions in silica aerogels

- Thomas–Reiche–Kuhn (TRK) sum rule for interacting photons

- Macroscopic QED for quantum nanophotonics: emitter-centered modes as a minimal basis for multiemitter problems

- Generation and dynamics of entangled fermion–photon–phonon states in nanocavities

- Polaritonic Tamm states induced by cavity photons

- Recent progress in engineering the Casimir effect – applications to nanophotonics, nanomechanics, and chemistry

- Enhancement of rotational vacuum friction by surface photon tunneling

- Plasmonics and Polaritonics

- Shrinking the surface plasmon

- Polariton panorama

- Scattering of a single plasmon polariton by multiple atoms for in-plane control of light

- A metasurface-based diamond frequency converter using plasmonic nanogap resonators

- Selective excitation of individual nanoantennas by pure spectral phase control in the ultrafast coherent regime

- Semiconductor quantum plasmons for high frequency thermal emission

- Origin of dispersive line shapes in plasmon-enhanced stimulated Raman scattering microscopy

- Epitaxial aluminum plasmonics covering full visible spectrum

- Metaoptics

- Metamaterials with high degrees of freedom: space, time, and more

- The road to atomically thin metasurface optics

- Active nonlocal metasurfaces

- Giant midinfrared nonlinearity based on multiple quantum well polaritonic metasurfaces

- Near-field plates and the near zone of metasurfaces

- High-efficiency metadevices for bifunctional generations of vectorial optical fields

- Printing polarization and phase at the optical diffraction limit: near- and far-field optical encryption

- Optical response of jammed rectangular nanostructures

- Dynamic phase-change metafilm absorber for strong designer modulation of visible light

- Arbitrary polarization conversion for pure vortex generation with a single metasurface

- Enhanced harmonic generation in gases using an all-dielectric metasurface

- Monolithic metasurface spatial differentiator enabled by asymmetric photonic spin-orbit interactions

Articles in the same Issue

- Editorial

- Editorial

- Optoelectronics and Integrated Photonics

- Disorder effects in nitride semiconductors: impact on fundamental and device properties

- Ultralow threshold blue quantum dot lasers: what’s the true recipe for success?

- Waiting for Act 2: what lies beyond organic light-emitting diode (OLED) displays for organic electronics?

- Waveguide combiners for mixed reality headsets: a nanophotonics design perspective

- On-chip broadband nonreciprocal light storage

- High-Q nanophotonics: sculpting wavefronts with slow light

- Thermoelectric graphene photodetectors with sub-nanosecond response times at terahertz frequencies

- High-performance integrated graphene electro-optic modulator at cryogenic temperature

- Asymmetric photoelectric effect: Auger-assisted hot hole photocurrents in transition metal dichalcogenides

- Seeing the light in energy use

- Lasers, Active optical devices and Spectroscopy

- A high-repetition rate attosecond light source for time-resolved coincidence spectroscopy

- Fast laser speckle suppression with an intracavity diffuser

- Active optics with silk

- Nanolaser arrays: toward application-driven dense integration

- Two-dimensional spectroscopy on a THz quantum cascade structure

- Homogeneous quantum cascade lasers operating as terahertz frequency combs over their entire operational regime

- Toward new frontiers for terahertz quantum cascade laser frequency combs

- Soliton dynamics of ring quantum cascade lasers with injected signal

- Fiber Optics and Optical Communications

- Propagation stability in optical fibers: role of path memory and angular momentum

- Perspective on using multiple orbital-angular-momentum beams for enhanced capacity in free-space optical communication links

- Biomedical Photonics

- A fiber optic–nanophotonic approach to the detection of antibodies and viral particles of COVID-19

- Plasmonic control of drug release efficiency in agarose gel loaded with gold nanoparticle assemblies

- Metasurfaces for biomedical applications: imaging and sensing from a nanophotonics perspective

- Hyperbolic dispersion metasurfaces for molecular biosensing

- Fundamentals of Optics

- A Tutorial on the Classical Theories of Electromagnetic Scattering and Diffraction

- Reflectionless excitation of arbitrary photonic structures: a general theory

- Optimization Methods

- Multiobjective and categorical global optimization of photonic structures based on ResNet generative neural networks

- Machine learning–assisted global optimization of photonic devices

- Artificial neural networks for inverse design of resonant nanophotonic components with oscillatory loss landscapes

- Adjoint-optimized nanoscale light extractor for nitrogen-vacancy centers in diamond

- Topological Photonics

- Non-Hermitian and topological photonics: optics at an exceptional point

- Topological photonics: Where do we go from here?

- Topological nanophotonics for photoluminescence control

- Anomalous Anderson localization behavior in gain-loss balanced non-Hermitian systems

- Quantum computing, Quantum Optics, and QED

- Quantum computing and simulation

- NIST-certified secure key generation via deep learning of physical unclonable functions in silica aerogels

- Thomas–Reiche–Kuhn (TRK) sum rule for interacting photons

- Macroscopic QED for quantum nanophotonics: emitter-centered modes as a minimal basis for multiemitter problems

- Generation and dynamics of entangled fermion–photon–phonon states in nanocavities

- Polaritonic Tamm states induced by cavity photons

- Recent progress in engineering the Casimir effect – applications to nanophotonics, nanomechanics, and chemistry

- Enhancement of rotational vacuum friction by surface photon tunneling

- Plasmonics and Polaritonics

- Shrinking the surface plasmon

- Polariton panorama

- Scattering of a single plasmon polariton by multiple atoms for in-plane control of light

- A metasurface-based diamond frequency converter using plasmonic nanogap resonators

- Selective excitation of individual nanoantennas by pure spectral phase control in the ultrafast coherent regime

- Semiconductor quantum plasmons for high frequency thermal emission

- Origin of dispersive line shapes in plasmon-enhanced stimulated Raman scattering microscopy

- Epitaxial aluminum plasmonics covering full visible spectrum

- Metaoptics

- Metamaterials with high degrees of freedom: space, time, and more

- The road to atomically thin metasurface optics

- Active nonlocal metasurfaces

- Giant midinfrared nonlinearity based on multiple quantum well polaritonic metasurfaces

- Near-field plates and the near zone of metasurfaces

- High-efficiency metadevices for bifunctional generations of vectorial optical fields

- Printing polarization and phase at the optical diffraction limit: near- and far-field optical encryption

- Optical response of jammed rectangular nanostructures

- Dynamic phase-change metafilm absorber for strong designer modulation of visible light

- Arbitrary polarization conversion for pure vortex generation with a single metasurface

- Enhanced harmonic generation in gases using an all-dielectric metasurface

- Monolithic metasurface spatial differentiator enabled by asymmetric photonic spin-orbit interactions