Eggshell membranes as green carriers for Burkholderia cepacia lipase: A biocatalytic strategy for sustainable wastewater bioremediation

-

Marta Ostojčić

Abstract

Early research on recycling agri-food industry waste focused on valorization to identify valuable components lost when waste is disposed of, reflecting a linear economy model. With the shift to a circular economy, current research aims for full recycling of waste containing high-value compounds. This study builds on previous work involving egg white layer proteins and high-purity calcium salts to explore the potential of eggshell membranes for lipase immobilization. Eggshell waste was treated with acids (5% hydrochloric, 10% acetic, 15% o-phosphoric), and then lipase from Burkholderia cepacia was immobilized using adsorption and covalent binding. The immobilized enzymes were tested for biochemical and operational properties. Results showed improved thermal stability, altered pH and temperature optima, and retention of up to 85% of initial activity after ten reuse cycles. Adsorption proved to be the most effective immobilization method, offering superior stability and reusability. Among the carriers tested, ESMC-HCl was identified as the most suitable, with the immobilized lipase successfully applied in the enzymatic pretreatment of wastewater from the oil-processing industry. This application achieved over 89% removal of chemical oxygen demand and reduced total oil content from 95% to 18% across four treatment cycles, demonstrating both effectiveness and reusability of the biocatalyst.

1 Introduction

The growing global population demands more resources, including food, water, and energy, and consequently generates increasing amounts of waste, emphasizing the need for sustainable management and environmental preservation. The relatively slow progress in the field of waste management has made this issue as a major global problem. Food waste can be used as a raw material for the production of a variety of value-added products, as it represents a valuable source of various nutrients [1]. Eggshells, among other waste materials, are an important food waste and a valuable potential raw material. For this reason, the possibilities of recycling eggshells have been investigated to avoid disposal in landfills. Initial uses of this waste included ground eggshells in the diets of poultry and laying hens as a source of calcium to investigate their nutritional quality compared to ground limestone [2,3,4,5]. Further research revealed that eggshells show a high absorption capacity for dyes [6,7,8], heavy metals [7,9,10,11], radionuclides [12], or gases [13,14]. In addition, eggshells were found suitable as a catalyst in various syntheses, such as for bioceramics [15,16,17,18,19] and biodiesel [20,21,22,23,24,25] or as a biodiesel purification agent [26], as well as for the remediation of oil spills [27]. Moreover, for the criteria of green building and the development of innovative environmentally friendly building materials through the replacement of cement and the production of bioconcrete, it has been shown that eggshells increase the strength of the obtained materials and also have great potential for the production of unburned clay blocks or value-added technical materials such as glass [28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39]. Furthermore, one of the more important applications is in medicine, where eggshells are a drug delivery vehicle [15] or a pharmaceutical excipient in pharmaceutical products [40], as well as a material for the production of bandages or even in tissue engineering [41,42,43]. On the other hand, in the food industry, eggshells are used as a source of calcium to enrich food products such as bread, biscuits, rice, snacks, meat, or drinks, where small changes in texture were observed without significant impact on taste [44]. Three papers have been published by our research group on the complete utilization of eggshell waste, in which (i) proteins were determined in aqueous solutions obtained by washing the eggshells during pretreatment, among which lysozyme stands out with an activity of 485821 U [45]. A further process, dissolving the eggshells with different acids, yielded (ii) high-purity calcium salts, but also (iii) eggshell membranes [45,46,47]. In our last published paper [46], looking at the complete utilization of eggshell waste, it was found that the eggshell membranes remaining after the treatment of eggshell waste with acid can be used for the immobilization of lipase.

Among various enzymes, lipases (E.C. 3.1.1.3) stand out because under the right reaction conditions, these adaptable biocatalysts can catalyse various reactions such as hydrolysis, esterification, transesterification, acidolysis, and aminolysis [48,49]. Lipases are widely utilized in the food industry and many other industries because of their versatility, particularly as food additives, in the production of biodiesel, and in the treatment of lipid-rich wastewater [49,50]. However, the high price of lipase and the inability of its reuse make the above-mentioned applications expensive. Exactly for this reason, immobilized lipases have become one of the most important biocatalytic systems used for many industrial purposes due to their advantages in terms of good chemical and thermal stability, with the possibility of reuse and easy recovery [48,50,51,52]. Today, various techniques are used to immobilize lipases, but immobilization by adsorption on solid carriers has proven to be the most common, especially when increasing or maintaining catalytic activity is the main goal of immobilization [48,53]. Immobilization by adsorption is based on the formation of relatively weak hydrophobic, van der Waals, and/or hydrogen bonds and ionic interactions between the enzyme and the carrier that do not lead to a change in the native structure of the enzyme [52,53,54]. Covalent immobilization enables strong and stable attachment of enzymes to solid carriers through the formation of covalent bonds. These bonds typically form between the amino groups of the enzyme and aldehyde, carboxyl, or epoxy groups on the carrier, or between enzyme carboxyl groups and amino groups on the carrier. Immobilization can be direct, where the enzyme binds directly to an activated functional group or indirect using a flexible arm attached to the carrier. A recent cost analysis of enzymatic biodiesel production [55] confirmed that the cost of the immobilization carrier is a major economic barrier for commercial application of enzyme-based processes, especially in flow-intensified systems. Since most of the commercially available carriers are primarily optimized for laboratory use [55] and are not competitive in terms of cost, having a relatively high price (380–550 EUR/kg [56]), there is a need to find cheaper ones. In this respect, various wastes and/or by-products of the agri-food industry might have a potential for use. According to the available literature, there are numerous waste-based carriers for enzyme immobilization, such as coconut fibres, waste grains, coffee grounds, onion husks, rice husk ash, and also eggshells or eggshell membranes [51,54]. Eggshell membrane, being an abundant agro-industrial waste, offers a promising alternative due to its low cost, favourable physicochemical properties, and proven potential for enzyme immobilization. However, the use of eggshell membrane as a carrier for immobilization of laccase [57], oxidase [58,59], glucose oxidase [60,61,62,63], urease [64], tyrosinase [65], uricase [66], catalase [67], β-galactosidase [68], and lipase [69,70,71] has been reported for the production of biosensors [59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67].

Although eggshell membranes have been previously investigated for enzyme immobilization, especially in the development of biosensors, there are few studies focusing on their use as carriers for lipases. This study is one of the first to investigate the influence of different chemical pretreatments of eggshell membranes on the immobilization of Burkholderia cepacia lipase (BCL) by adsorption and covalent methods. In addition, it is the first study to evaluate the biochemical and operational properties of the immobilized enzyme and its application in the pretreatment of real oily wastewater.

In this respect, we have examined the possibility of eggshell membrane immobilized lipases production to be used as a potential heterogeneous biocatalyst.

Eggshell membrane-based carriers (ESMC) were prepared by dissolving eggshells with three different acids (5% hydrochloric acid, 10% acetic acid, or 15% o-phosphoric acid) and used for immobilization of BCL by adsorption and covalent methods. Immobilized lipases were examined on biochemical and operational properties. Another objective of the present study was to evaluate the performance of the immobilized lipase for the treatment of oil-containing wastewater, specifically in terms of chemical oxygen demand (COD) and total oil reduction. The central hypothesis of this work is that chemically treated eggshell membranes can serve as effective, low-cost supports for the immobilization of B. cepacia lipase, with the specific aim of developing a reusable biocatalyst for the pretreatment of oil-rich wastewater, thereby integrating waste valorization within a sustainable bioremediation framework.

Eliminating pollutants from wastewater is essential to safeguard the environment, wildlife, and human health. A range of treatment methods has been designed to target contaminants such as lipids/oils, heavy metal ions, pharmaceuticals, and other harmful substances from various wastewater sources. Key approaches include adsorption, filtration, ion exchange, electrochemical processes, reverse osmosis, precipitation, flotation, coagulation/flocculation, and photocatalytic treatments [72]. For wastewater that is rich in organic matter, particularly effluents from the food industries, biological treatment is typically favoured over other treatment methods [73]. The main reason for removing oils and fats from wastewater is that their excessive presence can form a layer on the sludge surface, limiting the transfer of soluble substrates and oxygen to aerobic microorganisms. Furthermore, the long-term presence of fats and oils can lead to issues such as blockages and the emission of unpleasant odours. As a result, pretreatment to break down fats and oils is essential for improving the effectiveness of the subsequent biological treatment process [74,75,76]. Due to their environmentally friendly nature and clean application, lipases can be employed in a wide range of biotechnological processes, including the treatment of wastewater with high oil/fat content.

Considering the limited number of studies on the use of commercial lipases in the pretreatment of oil-rich wastewater, this study aims to evaluate the application of immobilized lipases, through several cycles of use, for the pretreatment of edible oil-industry wastewater.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Materials

Industrial eggshell waste was generously supplied by Elcon-nutritional products Ltd. (Zlatar Bistrica, Croatia). Wastewater containing edible oil was obtained from a nearby oil refinery (Tvornica ulja Čepin, Croatia).

Transformation process of eggshell waste was performed using 5% (w/v) hydrochloric, 10% (w/v) acetic, and 15% (w/v) o-phosphoric acid prepared from hydrochloric acid (37%, w/v) purchased from Carlo Erba (Emmendingen, Germany), acetic acid glacial (99–100%) purchased from LabExpert (Ljubljana, Slovenia), and o-phosphoric acid (85%) purchased from Fisher Chemical (Shanghai, China). The obtained eggshell membranes were washed with acetone purchased from LabExpert (Ljubljana, Slovenia). For carrier activation and flexible arm attachment, glutaraldehyde and polyethyleneimine were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Chemicals (Saint Louis, MO, USA). Amano lipase PS from B. cepacia (Sigma-Aldrich product number: 534641) was used for immobilization on the obtained eggshell membranes and was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Chemicals (Saint Louis, MO, USA). Lipase activity was measured with olive oil as substrate purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Chemicals (Saint Louis, MO, USA). Virgin olive (Trenton, Croatia), sunflower (Zvijezda, Croatia), vegetable (Omegol Croatia), rapeseed (S-BUDGET, Austria), and coconut (Encian, Croatia) oils, as well as fresh lard (PIK Vrbovec), were purchased in the local market, while waste cooking oil is collected in a nearby local restaurant (Osijek, Croatia). For the total oil content, n-hexane (Carlo Erba, Italy) and 96% ethanol (LabExpert, Kefo, Croatia) were used. All other chemicals used in this research were of pro-analysis purity.

2.2 Preparation of ESMC

ESMC were prepared according to the method previously reported by our research group [45,46,47]. Briefly, the preparation included washing of eggshell waste with distilled water in the 15 L conical batch reactor as described by Strelec et al. [46] and then mixing with 5% hydrochloric acid (HCl), 10% acetic acid (HAc), or 15% o-phosphoric acid (H3PO4), separately. The obtained eggshell membranes were filtered, washed, dried, and milled according to Strelec et al. [46]. Finally, three types of ESMC were obtained: ESMC-HCl, ESMC-Hac, and ESMC-H3PO4.

2.3 Immobilization of lipase on ESMC

2.3.1 Adsorption

Immobilization by adsorption of BCL on prepared ESMC was performed by the combination of the methods of Chattopadhyay and Sen [77] and Salleh et al. [78], over a period of 1 up to 6 h with constant rotation on a multi-rotator (Multi RS-60, bioSan, Riga, Latvia) set at 17 rpm at room temperature with different lipase initial activities ranging from 230 to 1,430 U in 50 mM phosphate buffer of pH 7.5. The ratio between the mass of the carrier and the volume of lipase solution was 1:20. After every hour of immobilization, vacuum filtration using a Whatman filter No. 1 was performed, and immobilized lipase was washed three times with 10 mL of buffer. Immobilized lipase activity was determined according to Mustranta et al. [79] and expressed as U·g−1 of the wet carrier. Immobilization yield was calculated based on the initial activity used for immobilization and the residual activity measured in the supernatant. After immobilization, the lipases were lyophilized for 48 h for further studies (ALPHA 2-4 LSC PLUS, Martin Christ Gefriertrocknungsanlagen GmbH, Germany).

2.3.2 Covalent binding

The covalent binding on the prepared ESMC was performed either directly on the activated groups of the ESMC or indirectly on the activated flexible arm. For direct covalent binding, the prepared carriers were activated with glutaraldehyde at concentrations of 0.5% and 1% for 2 h to determine the optimal concentration [80]. In the case of indirect covalent binding, activation of the prepared carriers with glutaraldehyde was followed by binding of the polyethyleneimine as a flexible arm at a concentration of 0.2% for 2 h according to the method of Cui et al. [81] and then by activation of the polyethyleneimine with 0.5% glutaraldehyde for 2 h. After activation of the carrier or flexible arm, covalent binding of lipase was then performed for 1–3 h with constant rotation on a Multi RS-60 multi-rotator (BioSan, Latvia) at 17 rpm at room temperature with different initial lipase activities ranging from 230 to 1,430 U. The ratio of the mass of the carrier to the volume of the lipase solution was 1:20. Subsequent steps of separation, washing, activity testing, and lyophilization of the immobilized lipase were performed as described for adsorption.

2.4 Characterization of free and immobilized lipase

The characterization of lipases included the determination of pH and temperature optimum, pH and temperature stability, stability in methanol and ethanol, as well as substrate specificity towards various oils/fats. In addition, the reusability of immobilized lipases was examined.

2.4.1 Lipase activity

BCL (free and immobilized) activity was determined by a titrimetric assay with olive oil as substrate according to Mustranta et al. [79]. The concentration of all buffers in the reaction mixture was 100 mmol·L−1. Enzyme addition was 1 mL (1 mg·mL−1) for free lipase, while for immobilized lipase, it was 100 mg (wet immobilized lipase) and 25 mg (lyophilized lipase).

2.4.2 pH and temperature optimum

The pH optimum of the free and immobilized lipases was determined in the pH range from 6 to 10. Three different buffer systems were used: sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6, 7, and 8), Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8 and 9) and glycine-NaOH buffer (pH 9 and 10). Once the pH optimum of lipase was determined, the temperature optimum at the pH optimum was carried out in the range from 30°C to 70°C.

2.4.3 pH and temperature stability

After determination of pH and temperature optimum, pH and thermal stabilities of free and immobilized lipases were investigated using a thermoblock (LLG uniBLOCKTHERM, Meckenheim, Germany) with constant stirring at 250 rpm. The pH stability was conducted during 6 h at optimal temperature by dissolving lipases in buffers of different pH (1 mg·mL−1 for free lipase, and 25 mg in 1.5 mL for lyophilized immobilized lipase): 100 mM sodium phosphate buffer of pH 6, 7, and 8 and 100 mM Tris-HCl buffer of pH 9. Temperature stability was investigated during 6 h at optimal pH (in optimal buffer) and at various temperatures (40°C, 50°C, 60°C, and 70°C). Samples were tested every hour (after centrifugation) for residual activity [%] of immobilized lipase, where the untreated and unheated sample activity was taken as 100%.

2.4.4 Stability in methanol and ethanol

Stability in methanol and ethanol was investigated during 3 h at optimal temperature, using a thermoblock (LLG uniBLOCKTHERM, Meckenheim, Germany) with constant stirring at 250 rpm, by dissolving lipases in 30% methanol or 30% ethanol solution (1 mg·mL−1 for free lipase and 25 mg in 1.5 mL of solvent for lyophilized immobilized lipase). Samples were tested every hour (after centrifugation) for the residual activity (%) of immobilized lipase, where the untreated and unheated sample activity was taken as 100%.

2.4.5 Substrate specificity

The substrate specificity of free and immobilized lipases towards various oils and lard was determined by titrimetric assay at optimal pH and temperature. Tested oils included olive oil standard, commercially available virgin olive oil, sunflower oil, vegetable oil, rapeseed oil and coconut oil, waste cooking oil, and fresh lard. The activity of lipase in olive oil standard was taken as 100%.

2.4.6 Reusability

The immobilized lipase activity in the hydrolysis of p-nitrophenyl palmitate (pNPP) according to Palacios et al. [82] was repeated 10 consecutive cycles to determine the reusability properties. Before each treatment, a fresh pNPP solution was added to the reaction mixture.

2.5 Evaluation of the functionality of BCL immobilized on ESMC in wastewater treatment

To evaluate the functionality of the selected immobilized lipase in terms of COD and oil reduction, three different concentrations (2, 8, and 16 g·L−1) of the selected immobilized lipase in wastewater were tested over 2, 4, 6, and 24 h with constant rotation on a magnetic stirrer (2mag magnetic motion, MIX 6, 2mag AG, München, Germany) placed in a universal dryer (Memmert, LLG, Meckenheim, Germany) at 40°C. Prior to analysis, the samples were filtrated with Whatman filter paper 113 to separate the immobilized BCL from the wastewater. Additionally, reusability was examined over five cycles. The COD in the wastewater was measured using Hach Lange LCK514 cuvette tests, following the manufacturer’s instructions. The samples were first decomposed in the HT200S High temperature thermostat (Hach Lange, Germany), after which the concentration for COD was measured in the DR3900 laboratory spectrophotometer (Hach Lange, Germany). All samples were processed within 24 h of their delivery to the laboratory. The total oil content was determined in duplicate using the partition gravimetric standard method 5520 B [83].

2.6 Statistical analysis

Mean values and standard deviations were calculated using Microsoft® Excel® 2016 MSO. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) (p < 0.05) was used to evaluate statistical differences between lipases and tested characterization parameters using software Statistica 14.0.0.15. TIBCO Software Inc. Fisher post hoc test was conducted (p < 0.05) to determine statistical differences between immobilized lipases.

3 Results

3.1 Adsorption

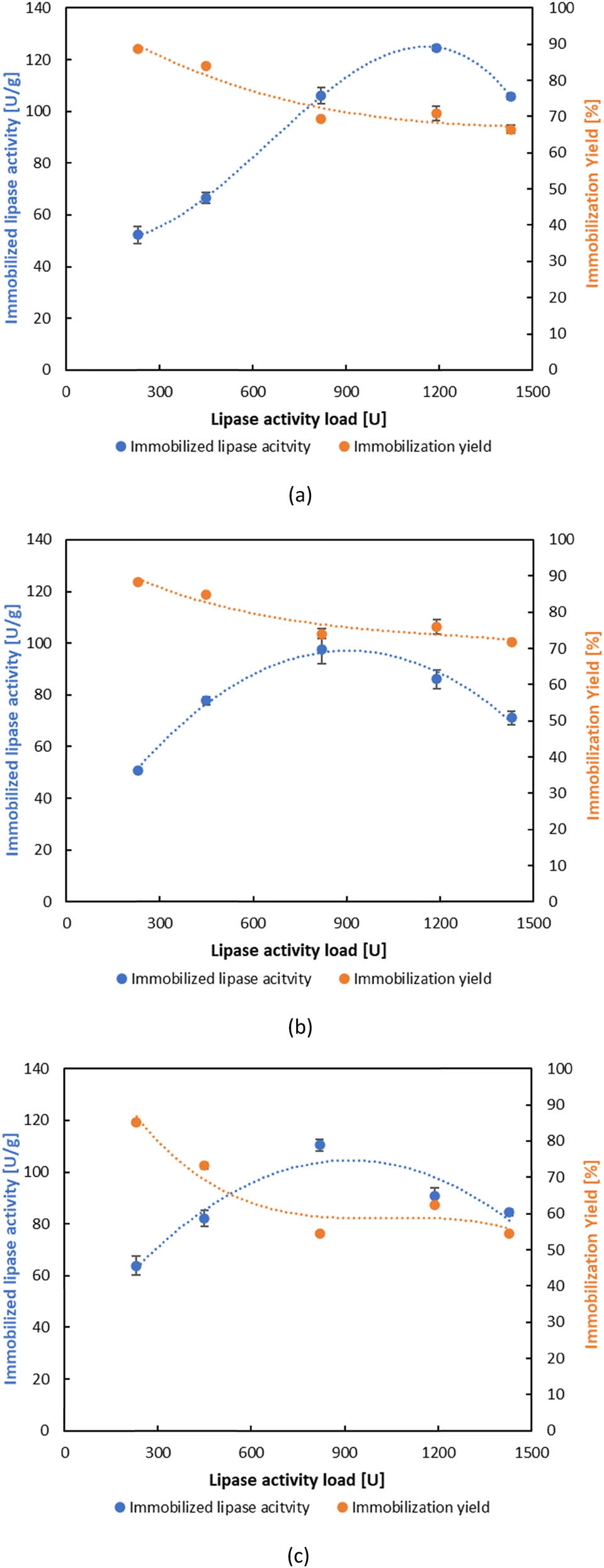

Although eggshell membrane was long regarded as waste, new investigations have shown that it contains unique qualities that have drawn the interest of numerous researchers. Eggshell membrane, mostly in its raw form, has been used in immobilization studies due to its low cost, permeability, and surface area. In this article, BCL with different lipase initial activities ranging from 230 to 1,430 U was immobilized on acid-obtained ESMC. Preliminary studies have shown that the optimal time for immobilization by adsorption of BCL on ESMC was one hour, and that the highest activities of the immobilized lipase are achieved with high initial lipase activities, specifically 820 and 1,190 U. It is interesting to note that by applying an immobilization time longer than one hour, the activity of immobilized lipase decreased. Salleh et al. [78] in their article, immobilized several lipases on eggshells and showed optimal immobilization time of 2 h followed by 1 h of incubation time, where also longer immobilization time leads to activity decrease. This phenomenon was explained by Strelec et al. [46] by utilizing the concept of multi-layered adsorption, which can result in the steric interference of nearby immobilized enzymes and thus impede substrate-related activity. Considering the optimal immobilization time, Figure 1 shows that as the lipase load for immobilization increases, the activity of the immobilized lipase also increases, while the immobilization yield decreases, ranging from 54.57% to 88.69%. This trend can be clarified by the fact that a greater amount of enzyme in the immobilization mixture increases the probability of enzyme molecules binding to the carrier, resulting in higher overall catalytic activity. However, the immobilization yield declines due to the limited number of available binding sites on the carrier. Once these sites are saturated, the excess enzyme remains in the supernatant and is not immobilized [84,85]. At higher enzyme concentrations, steric hindrance and molecular crowding on the carrier surface may reduce binding efficiency and lead to unfavourable enzyme orientations or partial inactivation [86]. This is consistent with the observed drop in activity at the highest lipase load tested, which can be attributed to surface oversaturation, conformational changes of the immobilized enzymes, and potential diffusion limitations, such as restricted substrate access.

Effect of lipase activity load on the activity of immobilized lipase and immobilization yield by adsorption: (a) ESMC-HCl, (b) ESMC-HAc, and (c) ESMC-H3PO4.

The factors of time and activity were essential for the initial selection of immobilized lipases. Analysing each ESMC separately, the highest lipase activity was observed on ESMC-HCl at 1190 U and measured 124.50 ± 0.90 U·g−1. The maximum activity for the other two ESMC was found at 820 U and measured 97.65 ± 5.46 and 110.44 ± 2.37 U·g−1 for ESMC-HAc and ESMC-H3PO4, respectively. The obtained results are higher than those reported by Jiang et al. [71] who found 12 U·g−1 as the maximum ester hydrolysis activity of BCL immobilized on eggshell membrane.

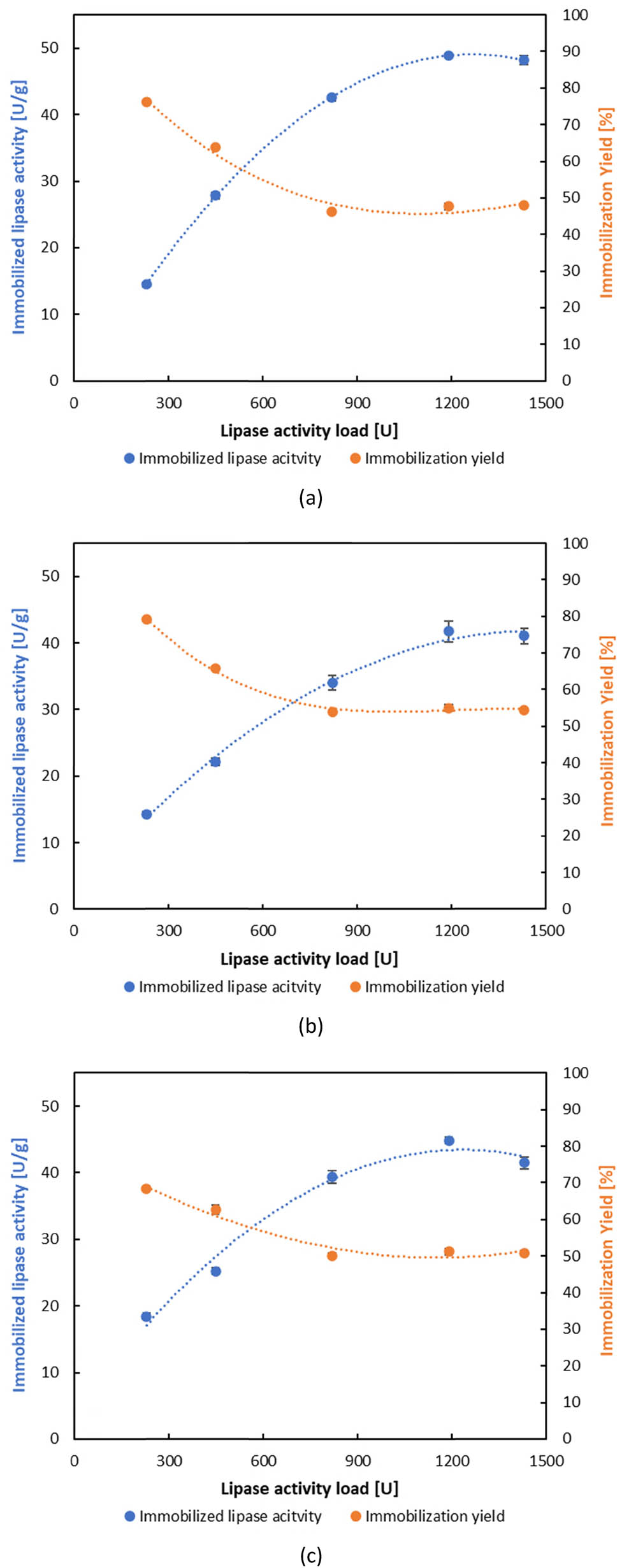

3.2 Covalent binding

The covalent immobilization of BCL initially required activation of the ESMC with glutaraldehyde, which was optimized with respect to its concentration. Considering the similar behaviour of all ESMC during immobilization by adsorption, but also the highest activity on ESMC-HCl, the optimization of carrier activation with glutaraldehyde was performed only with ESMC-HCl using two concentrations (0.5% and 1%). On the activated ESMC-HCl, BCL was directly immobilized for 1–3 h to investigate the optimal immobilization time, while in the case of indirect covalent binding, first, polyethyleneimine was attached and activated, and therefore, immobilization was performed. The results of the influence of glutaraldehyde concentration and immobilization time showed that higher activities of immobilized lipases were obtained on ESMC-HCl activated with 0.5% glutaraldehyde and that the optimal immobilization time was 1 h for both covalent binding methods. Similar to adsorption, the same trends were observed for both direct and indirect covalent binding methods, where the activity of the immobilized lipase increased as the lipase load was raised, while the immobilization yield decreased (Figures 2 and 3). However, the yield ranged differently for each method: for direct covalent binding, it varied between 46.19% and 79.09%, while for indirect covalent binding, the yield was the highest of all three methods, ranging from 76.86% to 97.08%. These findings indicate that, despite the similar trends in activity and yield across the three methods, each method displayed distinct immobilized lipase activity and immobilization yield values based on the type of ESMC applied. In the optimal hour of immobilization by covalent binding, the activity of maximum 43.92 ± 0.29 and 48.08 ± 0.54 U·g−1 was obtained, for direct and indirect methods, respectively. These results were lower than those published by Abdulla et al. [69], which showed an activity of 80 U·g−1 of BCL immobilized on eggshell membrane pretreated with glutaraldehyde. Comparing these results with those obtained by adsorption, it is clear that covalent binding was less efficient, as adsorption leads to up to 2.5 times higher activity values in the first hour (124.50 ± 0.90 U·g−1). These results are in agreement with those published by Tembe et al. [65], who immobilized tyrosinase on eggshell membranes by (i) adsorption, (ii) adsorption followed by glutaraldehyde cross-linking, and (iii) glutaraldehyde activation of the eggshell membrane followed by adsorption, where physical adsorption yielded the highest activity.

Effect of lipase activity load on the activity of immobilized lipase and immobilization yield by direct covalent binding: (a) ESMC-HCl, (b) ESMC-HAc, and (c) ESMC-H3PO4.

Effect of lipase activity load on the activity of immobilized lipase and immobilization yield by indirect covalent binding: (a) ESMC-HCl, (b) ESMC-HAc, and (c) ESMC-H3PO4.

Generally, the obtained results showed that the covalent method does not achieve high enzyme activity per gram of carrier, which confirms that covalent binding can cause a considerable loss of enzyme activity during immobilization [52]. However, results for the indirect method contradicted the hypothesis that the incorporation of a flexible arm increases the mobility of the immobilized enzyme and thus increases its activity compared to direct covalent binding [87].

3.3 Free and immobilized lipase characterization

For further characterization of the immobilized lipases, one of the highest recorded activities on each carrier for each method at the optimal immobilization time was selected. Since there were no notable differences in the results obtained using the highest initial activities applied (820, 1,190, and 1,430 U), the activities of lyophilized lipases were taken into consideration, as well as the cost-effectiveness of the immobilization process. Accordingly, taking all of the above into consideration, ESMC-HCl-BCL-820U was selected for immobilization by adsorption and indirect covalent binding, while ESMC-HCl-BCL-1190U was chosen for immobilization by direct covalent binding.

According to our knowledge, there are no data in the available literature on the characterization of BCL immobilized on ESMC prepared by exposure of eggshells to various acids. There are only three articles dealing with the immobilization of lipase on eggshell membranes: Abdulla et al. [69] immobilized BCL on ESM preactivated with glutaraldehyde; Jiang et al. [71] immobilized BCL on crude and oxidized eggshell membranes by adsorption and with two other immobilization methods, but without characterizing the resulting immobilized lipases; Işık et al. [70] immobilized lipase from Acinetobacter haemolyticus on eggshell membranes using glutaraldehyde as an activating or crosslinking agent. In this context, all comparisons of the properties of the immobilized lipases obtained in this study were made with available literature data on BCL immobilized on different types of carriers, as well as with data on other enzymes immobilized on eggshell membranes using various immobilization methods.

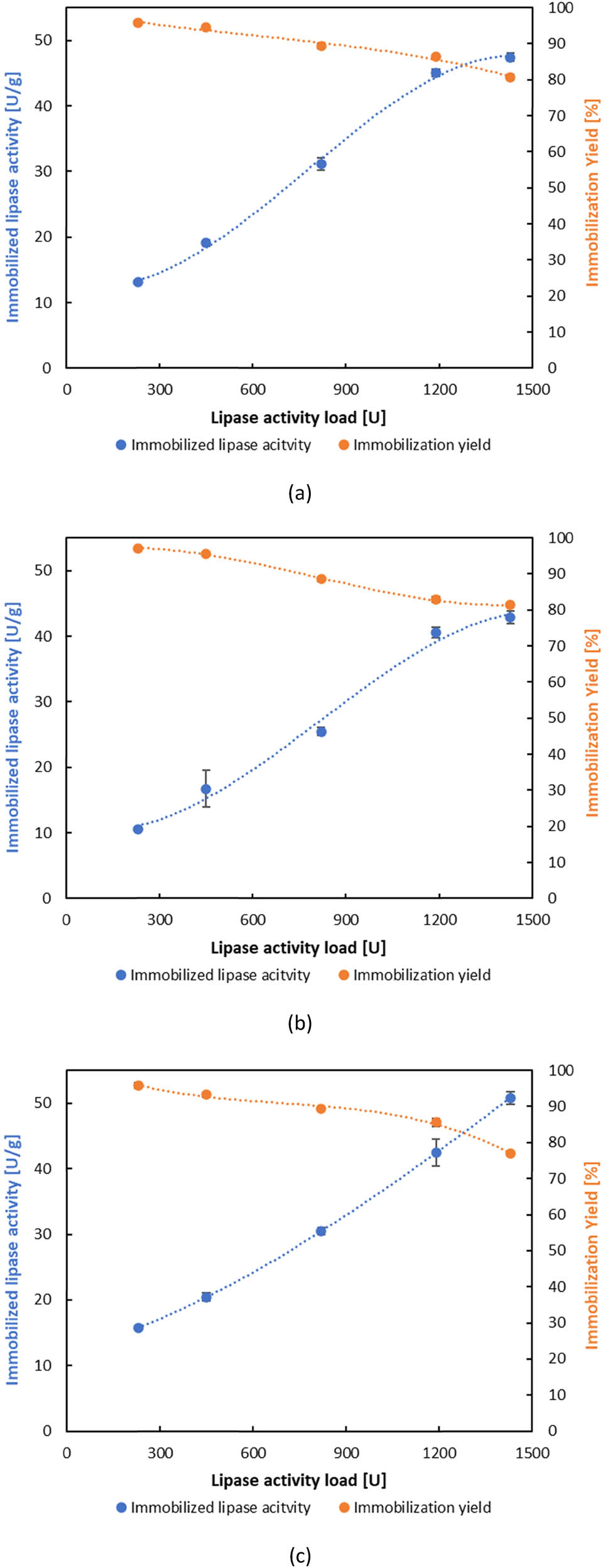

3.3.1 pH and temperature optimum

The effects of pH on the hydrolysis of olive oil were examined in the pH range from 6 to 10. According to Figure 4, the maximum of relative activity was observed at pH 8 for free lipase and at pH 9 for all of the immobilized lipases. The highest activities for all tested lipases were obtained in the pH range of 7–9, while lower activities were observed at both acidic pH 6 and alkaline pH 10. According to Mokhtar et al. [88], in an alkaline environment, immobilized lipase has higher activity than free lipase, while Işık et al. [70] reported that the activity of the lipase immobilized on the eggshell membrane was higher than that of the free enzyme at almost all pH values investigated, which was all confirmed in the present study. Most surprising was the fact that the optimal pH differentiated in one pH unit between free and immobilized lipases. Regarding free lipase, BCL exhibits the highest activity at pH 8 in sodium phosphate buffer, whereas immobilized lipases show peak activity at pH 9 in Tris-HCl buffer. The shift in optimal pH value for the immobilized lipases, according to Cao et al. [89] and Mokhtar et al. [88], may have been due to the stronger interactions between the lipase and the carrier, including hydrogen bonding as well as electrostatic interactions; however, it does not necessarily have to occur. Different authors obtained different results when immobilizing lipases. Thus, Ali et al. [90], Mortazavi and Aghaei [91], and Ghadi et al. [92] also showed a pH optimum shift towards an alkaline medium, Ferreira et al. [93] towards acidic, while El-Ghonemy et al. [94] obtained the same pH optimum values for free and immobilized lipases. The obtained data on the pH optimum for the free lipases are in accordance with our previous paper [95] where the pH optimum of free BCL was tested with two assays, and also with report from Padilha et al. [96], but are slightly different from those reported by Liu et al. [97] and Dalal et al. [98] (pH 9). Moreover, according to the literature, immobilized BCL showed the highest activities in the pH range of 7–7.5 [92,99,100].

pH optimum of free and lipase immobilized by (a) adsorption, (b) direct covalent binding, and (c) indirect covalent binding. Results are shown as average value ± standard deviation of three independent determinations.

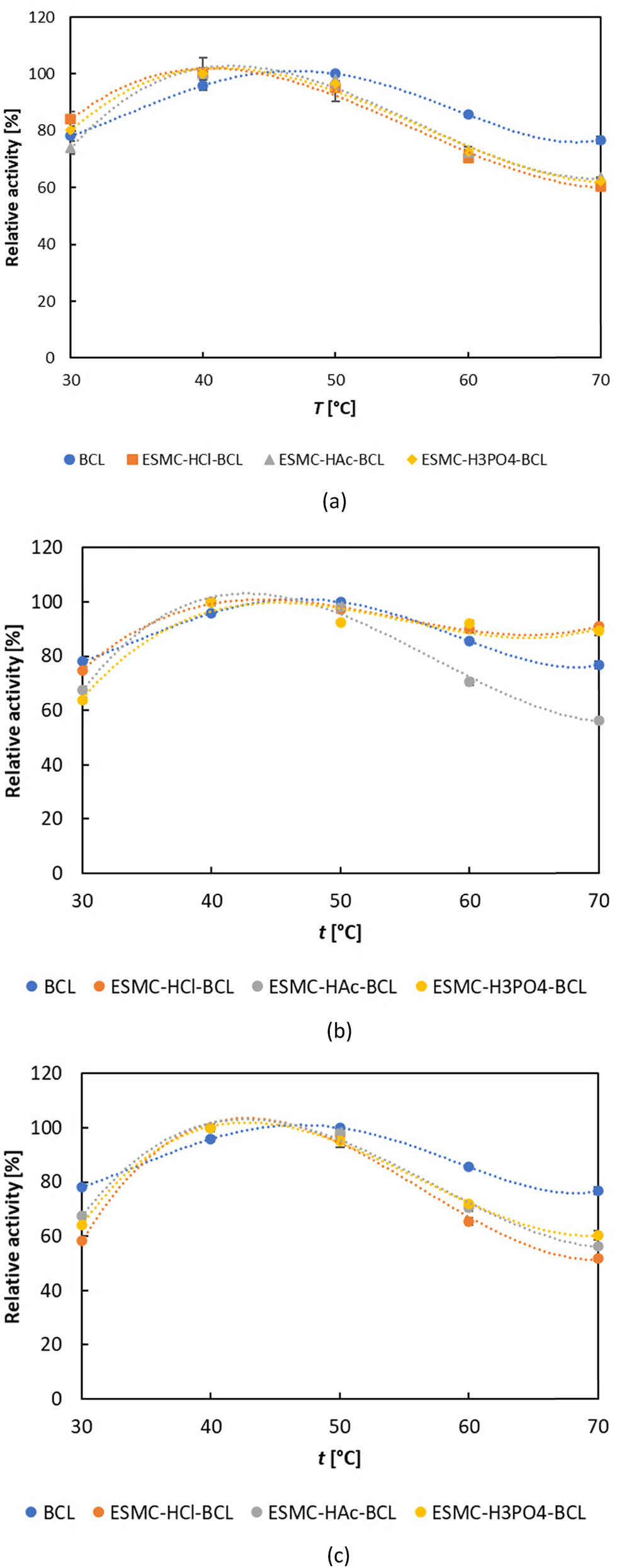

Once the pH optimum was found, the temperature optimum at optimal pH was determined (Figure 5). A shift in the temperature optimum between free and immobilized lipases also occurred. Free BCL optimally hydrolyzed olive oil at 50°C, while immobilized lipases showed the highest activity at 40°C. According to Işık et al. [70], carriers as eggshell membrane contain large amounts of –OH groups in their structure and hence have the ability to change the optimum temperature of the immobilized enzyme compared to the free enzyme, since they protect its structure against a temperature change. In enzyme immobilization studies using eggshell membrane and other carriers, there are papers in which the optimum temperature value changes after immobilization [58,77]. When evaluating the immobilized lipases at the highest tested temperature of 70°C, the lipases immobilized by direct covalent binding retained the highest activity, confirming a positive effect on the protection of lipases from loss of activity during manipulation at higher temperatures. The obtained data on the temperature optimum of free lipase are different from those reported by Padilha et al. [96] (37°C), Dalal et al. [98] (40°C), Liu et al. [97] (55°C), Wang et al. [101] (60°C), and Yang et al. [102] (70°C) but are in agreement with those reported by Sharma et al. [103] and Sánchez et al. [104]. According to reports on immobilized BCL, when immobilized on various carriers using different methods, it exhibited the highest activity within a temperature range of 40–70°C [69,92,99,105].

Temperature optimum of free and lipase immobilized by (a) adsorption, (b) direct covalent binding, and (c) indirect covalent binding. Results are shown as average value ± standard deviation of three independent determinations.

3.3.2 pH and temperature stability

Contrary to expectations based on the literature, the immobilized BCL exhibited lower pH stability than its free form (Table 1). After 6 h of incubation, the adsorption-immobilized BCL retained 60.19 ± 0.59 to 86.27 ± 1.96% of its initial activity, whereas the free enzyme retained up to full initial activity. Lipases immobilized by direct covalent binding were found to be relatively resistant to the effect of pH, retaining 49.15 ± 0.29 to 86.77 ± 1.06% of their activity over a 6-h period, with the highest stability at pH 9. On the other hand, lipases immobilized by indirect covalent binding were less stable and retained only 22.57 ± 1.68 to 51.57 ± 1.76% of their activity. This result is somewhat surprising, as immobilization is generally reported to enhance the pH stability of lipases. Indeed, numerous studies have documented improved pH tolerance and structural stability of lipases following immobilization [88,106]. However, the observed reduction in pH stability could be due to several factors [107,108,109,110]. First, the unfavourable surface charge of the carrier (e.g., a negative charge) may lead to microscopic pH fluctuations in the environment of the enzyme, thereby impairing its catalytic activity. Second, conformational changes caused by immobilization could limit the structural flexibility of the enzyme and impair its ability to adapt to pH fluctuations. Finally, steric hindrance effects could limit the access of substrates to the active site, especially under extreme pH conditions.

pH stability of free and immobilized BCL

| pH stability (6 h) | Free BCL | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| pH 6 (%) | 81.63 ± 0.27 | ||

| pH 7 (%) | 75.38 ± 0.00 | ||

| pH 8 (%) | 101.50 ± 1.67 | ||

| pH 9 (%) | 86.53 ± 0.70 | ||

| BCL immobilized by adsorption | |||

| ESMC-HCl-BCL | ESMC-HAc-BCL | ESMC-H 3 PO 4 -BCL | |

| pH 6 (%) | 69.10 ± 1.23a | 86.27 ± 1.96b | 82.18 ± 0.43c |

| pH 7 (%) | 62.48 ± 0.85a | 69.72 ± 2.65b | 67.94 ± 0.82b |

| pH 8 (%) | 63.14 ± 2.45a,b | 60.19 ± 0.59a | 65.21 ± 1.90b |

| pH 9 (%) | 73.64 ± 2.40a | 64.23 ± 1.87b | 69.51 ± 0.69a |

| BCL immobilized by direct covalent binding | |||

| ESMC-HCl-BCL | ESMC-HAc-BCL | ESMC-H 3 PO 4 -BCL | |

| pH 6 (%) | 76.90 ± 0.85a | 83.06 ± 2.74a | 70.92 ± 2.23b |

| pH 7 (%) | 62.49 ± 1.28a | 53.72 ± 1.49b | 51.79 ± 1.63b |

| pH 8 (%) | 49.15 ± 0.29a | 51.64 ± 0.42b | 52.26 ± 0.94b |

| pH 9 (%) | 75.90 ± 1.36a | 82.42 ± 1.96b | 86.77 ± 1.06c |

| BCL immobilized by indirect covalent binding | |||

| ESMC-HCl-BCL | ESMC-HAc-BCL | ESMC-H 3 PO 4 -BCL | |

| pH 6 (%) | 28.18 ± 1.94a,b | 25.48 ± 1.55a | 29.42 ± 0.53b |

| pH 7 (%) | 28.42 ± 4.65a | 27.25 ± 0.26a | 24.88 ± 0.85a |

| pH 8 (%) | 24.69 ± 0.41a | 24.63 ± 1.42a | 22.57 ± 1.68a |

| pH 9 (%) | 51.15 ± 1.61a | 50.21 ± 1.18a | 51.57 ± 1.76a |

Results are shown as average value ± standard deviation of three independent determinations. Means with the different superscripts within the raw indicate significant differences; p < 0.05.

Since the operation of bioprocesses at elevated temperatures is advantageous due to higher diffusion rates, lower substrate viscosity, better solubility of reactants, and lower risk of microbial contamination, the immobilization of lipases on solid carriers helps to increase their thermostability and expand their biotechnological potential [106]. Table 2 presents the temperature stability of free and immobilized BCL. At lower temperatures (≤60°C), immobilized lipases retained approximately 42–86% of their initial activity, while a more pronounced decrease was observed at 70°C. Free lipase demonstrated slightly better thermal stability at 40°C and 50°C, retaining full activity at optimal temperature, with only a slight drop to 88% at 40°C. However, its stability declined significantly at elevated temperatures, with activity falling to 52.88 ± 0.86% at 60°C and complete inactivation at 70°C. In contrast, immobilized lipases retained up to 59% of their activity at 70°C, indicating improved thermal stability due to immobilization, as in the literature [111,112,113], with lipases immobilized by direct covalent binding showing the highest stability. Girelli and Scuto [57] investigated the thermal stability of laccase immobilized on eggshell membranes for one hour at 30°C, 40°C, and 50°C and showed a slightly lower stability of the immobilized compared to the free enzyme. Similar results were presented by Kharrat et al. [106] who immobilized lipase from R. oryzae on silica aerogels by adsorption and observed during the thermostability test that although the free lipase is inactivated at 60°C, the immobilized lipase retains 83% of its activity. Corrêa et al. [105] reported that, at 70°C, the lipase thermal deactivation is increased, but immobilization positively affected lipase stability at high temperatures [88,106]. This may be because lipase is located inside carrier micropores, which provide good resistance to changes. Because of the constraint on its conformational flexibility caused by the many attachment points of the enzyme on the carrier, which limit the conformational modifications and movements under different temperatures, immobilized enzyme is frequently observed to have a higher thermal stability than free enzyme.

Temperature stability of free and immobilized BCL

| Temp. stability (6 h) | Free BCL | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 40°C (%) | 88.11 ± 0.63 | ||

| 50°C (%) | 101.50 ± 1.67 | ||

| 60°C (%) | 52.88 ± 0.86 | ||

| 70°C (%) | 1.19 ± 0.24 | ||

| BCL immobilized by adsorption | |||

| ESMC-HCl-BCL | ESMC-HAc-BCL | ESMC-H 3 PO 4 -BCL | |

| 40°C (%) | 73.64 ± 2.40a | 64.23 ± 1.87b | 69.51 ± 0.69a |

| 50°C (%) | 63.91 ± 1.67a | 66.70 ± 1.42a | 75.53 ± 1.13b |

| 60°C (%) | 65.60 ± 0.96a | 63.80 ± 2.15a | 73.65 ± 2.35b |

| 70°C (%) | 43.54 ± 1.84a | 43.83 ± 1.31a | 45.93 ± 0.92a |

| BCL immobilized by direct covalent binding | |||

| ESMC-HCl-BCL | ESMC-HAc-BCL | ESMC-H 3 PO 4 -BCL | |

| 40°C (%) | 75.90 ± 1.36a | 82.42 ± 1.96b | 86.77 ± 1.06c |

| 50°C (%) | 66.08 ± 0.65a | 67.75 ± 0.92b | 66.58 ± 0.59b |

| 60°C (%) | 64.28 ± 0.16a | 64.47 ± 1.52a | 62.64 ± 0.52a |

| 70°C (%) | 55.31 ± 1.04a | 59.92 ± 0.67b | 54.48 ± 0.93a |

| BCL immobilized by indirect covalent binding | |||

| ESMC-HCl-BCL | ESMC-HAc-BCL | ESMC-H 3 PO 4 -BCL | |

| 40°C (%) | 51.15 ± 1.61a | 50.21 ± 1.18a | 51.57 ± 1.76a |

| 50°C (%) | 68.09 ± 1.32a | 57.20 ± 0.73b | 53.51 ± 1.91c |

| 60°C (%) | 50.64 ± 1.74a | 42.63 ± 1.33b | 46.11 ± 0.69c |

| 70°C (%) | 40.32 ± 0.68a | 37.35 ± 0.61b | 49.28 ± 0.11c |

Results are shown as average value ± standard deviation of three independent determinations. Means with the different superscripts within the raw indicate significant differences; p < 0.05.

3.3.3 Stability in methanol and ethanol

Stability in organic solvents is a very important issue in the use of lipases in real systems, where the most commonly used solvents are methanol and ethanol, which can have an inactivating effect on lipases. Therefore, the stability of free and immobilized BCL in 30% solutions of methanol and ethanol was tested for 3 h, and the results are presented in Table 3. When comparing the stabilities in the two selected solvents, it can be concluded that immobilized lipases exhibited similar stability within each solvent. However, slightly better stability was observed in methanol, where the lowest recorded relative activity remained above 70%. Overall, the results showed that ethanol inactivates lipases more than methanol, which is not in accordance with the statement by Lotti et al. [114], who reported that lipase inactivation tends to decrease with an increasing number of carbon atoms in the alcohol, although the preference for alcohol type is enzyme specific. Nonetheless, the same authors noted that lipases from the Pseudomonas/Burkholderia genus exhibit high tolerance to methanol [114].

Stability in methanol and ethanol of free and immobilized BCL

| Organic solvent (3 h) | Free BCL | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Methanol (%) | 85.10 ± 0.71 | ||

| Ethanol (%) | 90.10 ± 2.84 | ||

| BCL immobilized by adsorption | |||

| ESMC-HCl-BCL | ESMC-HAc-BCL | ESMC-H 3 PO 4 -BCL | |

| Methanol (%) | 76.25 ± 0.91a | 78.96 ± 1.12a | 84.46 ± 1.98b |

| Ethanol (%) | 61.67 ± 0.28a | 67.85 ± 0.45b | 74.46 ± 2.66c |

| BCL immobilized by direct covalent binding | |||

| ESMC-HCl-BCL | ESMC-HAc-BCL | ESMC-H 3 PO 4 -BCL | |

| Methanol (%) | 68.56 ± 1.10a | 71.08 ± 2.61a,b | 74.28 ± 0.58b |

| Ethanol (%) | 73.42 ± 0.63a | 72.48 ± 0.92a | 67.72 ± 0.60b |

| BCL immobilized by indirect covalent binding | |||

| ESMC-HCl-BCL | ESMC-HAc-BCL | ESMC-H 3 PO 4 -BCL | |

| Methanol (%) | 40.90 ± 0.68a | 36.56 ± 1.49b | 41.56 ± 0.25a |

| Ethanol (%) | 28.16 ± 0.64a | 25.93 ± 2.35a | 28.50 ± 1.20a |

Results are shown as average value ± standard deviation of three independent determinations. Means with the different superscripts within the raw indicate significant differences; p < 0.05.

The stronger inactivation of BCL by ethanol compared to methanol can be attributed to the different interactions with the enzyme. Ethanol is a larger molecule and more hydrophobic than methanol, which may disrupt the hydrophobic residues on the surface of the lipase, and affect its tertiary structure and stability [115,116,117,118]. Methanol tends to be better tolerated by certain lipases, including BCL, possibly due to enzyme-specific adaptations. In addition, the immobilization technique used also affects stability: Adsorption keeps the enzyme more flexible and stable, whereas covalent binding may increase susceptibility to solvent-induced denaturation, especially by hydrophobic solvents such as ethanol. In summary, the stronger hydrophobic interactions of ethanol, the enzyme-specific solvent tolerance, and the immobilization effects together explain the observed increased inactivation of BCL by ethanol. This is consistent with existing studies on the behaviour of lipases in organic solvents [115,116].

In contrast, regarding the free lipase, BCL showed greater inactivation in methanol, where tolerance to both solvents decreased after immobilization. For example, its activity in methanol dropped from 85.10 ± 0.71% (free form) to 74.28 ± 0.58% (direct covalent binding), and further to 36.56 ± 1.49% (indirect covalent binding), while the highest activity was retained in adsorption-based immobilization (84.46 ± 1.98%). A similar trend was observed with ethanol: stability decreased after immobilization, ranging from 74.46 ± 2.66% (adsorption) and 67.72 ± 0.60% (direct covalent) to 25.93 ± 2.35% (indirect covalent). In general, adsorption-immobilized lipases were the most stable, followed by those immobilized via direct covalent binding, while the least stable were those immobilized via indirect covalent binding.

3.3.4 Substrate specificity

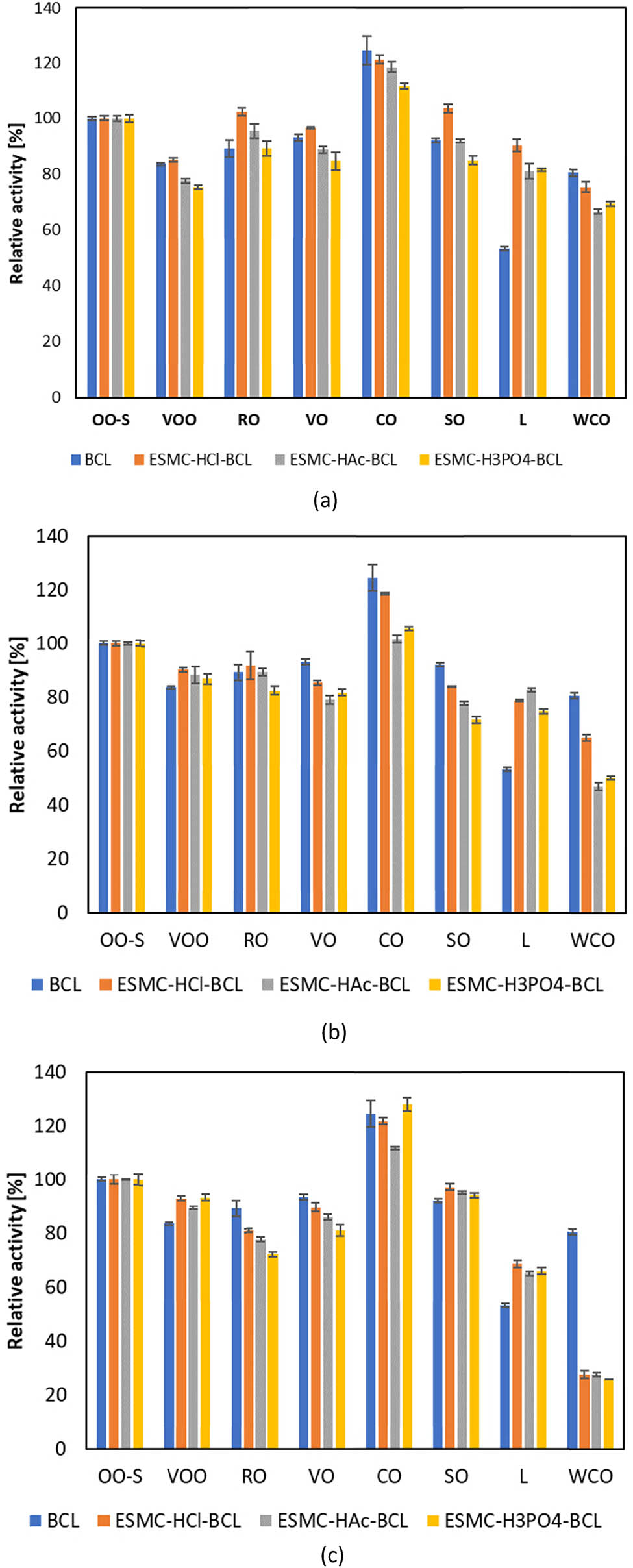

Regarding substrate specificity, a similar trend in the hydrolysis of the tested oils was observed between free and immobilized BCL (Figure 6). The exception was lard, where immobilized lipases showed greater activity compared to free lipase, and waste cooking oil, where the situation was reversed, with free lipase showing greater specificity than the immobilized forms. In general, all lipases exhibited the highest activity with coconut oil. According to Dalal et al. [98], BCL also showed higher activity towards coconut oil compared to olive oil. The substrate specificity results for free BCL align with our previous work [95], where BCL exhibited nearly equal activity in virgin olive oil, rapeseed oil, vegetable oil, and sunflower oil. Moreover, while coconut oil exhibited the highest activity in this study, this was not the case in our previous work, which could be attributed to differences in the brands or lots of commercially available oils. Coconut oil is classified as a saturated fat due to its high content of saturated fatty acids. However, unlike most saturated fats, it consists mainly of medium-chain triglycerides, which are easily digested and quickly metabolized for energy. Regulatory data [119] indicate that coconut oil contains 45–53% lauric acid (C12:0) and 16–21% myristic acid (C14:0), in contrast to common vegetable oils such as sunflower, rapeseed, and olive oils, which are predominantly rich in oleic acid. The increased lipase activity observed with coconut oil can be explained by several factors. Although lipases generally exhibit broad specificity with a relatively low preference for C12:0 and C14:0 fatty acids [120], their pronounced activity towards coconut oil seems to be due to the fact that lauric acid is more readily hydrolysed compared to oleic acid [121]. Additionally, the physical properties of the substrate play a significant role, while coconut oil (often referred to as coconut fat due to its solid state at room temperature) is saturated, its distinct profile of medium-chain triglycerides enhances the enzyme’s accessibility. This pronounced activity also explains the comparatively high activity in lard, which contains a significant proportion of 20–32% lauric acid [119].

Substrate specificity of free and lipase immobilized by (a) adsorption, (b) direct covalent binding, and (c) indirect covalent binding to selected oils and fats (OO-S – olive oil standard, VOO – virgin olive oil, RO – rapeseed oil, VO – vegetable oil, CO – coconut oil, SO – sunflower oil, L – lard, WCO – waste cooking oil). Results are shown as average value ± standard deviation of three independent determinations.

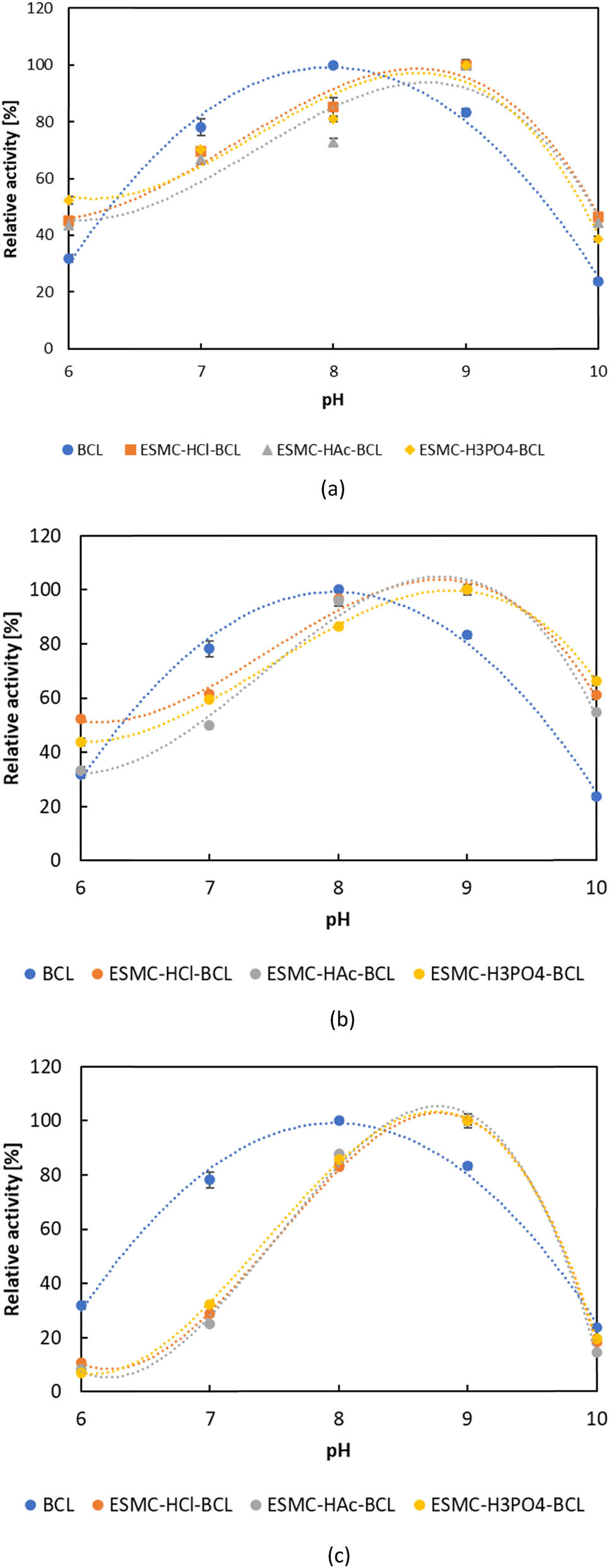

3.3.5 Reusability

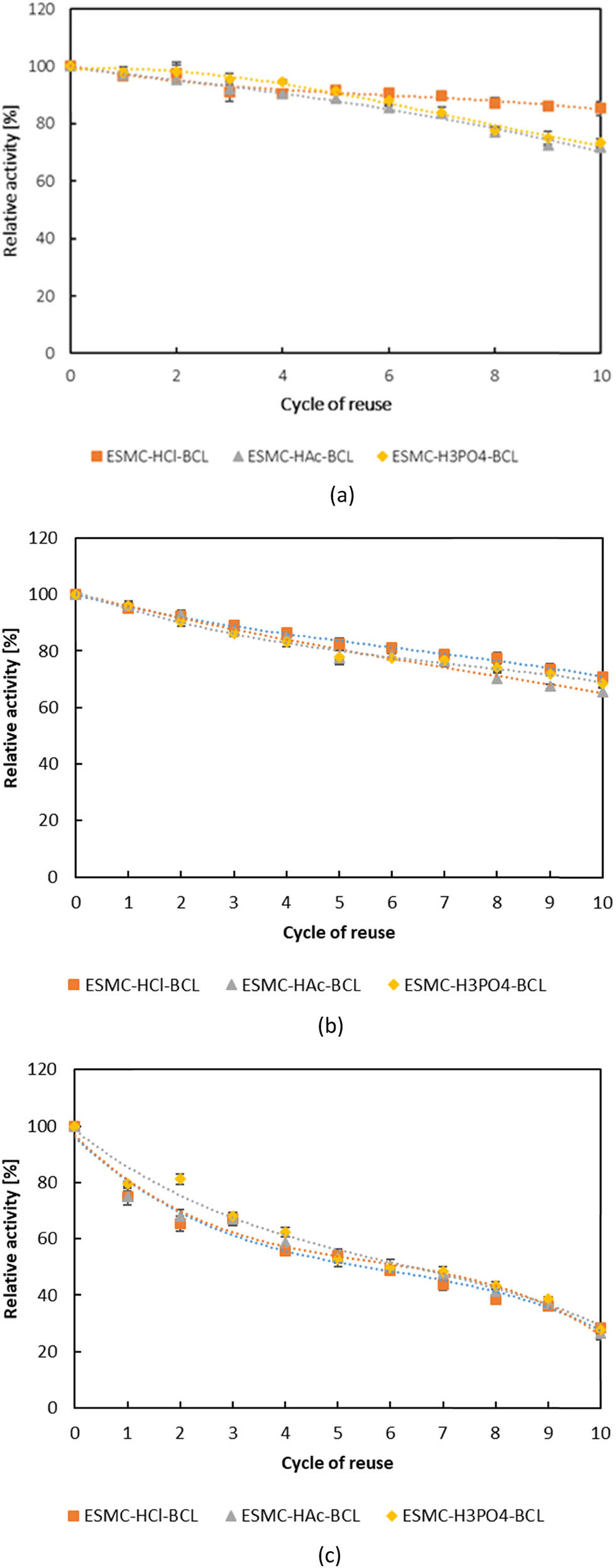

In contrast to free enzymes, which are used only once and are difficult to separate from the reaction mixture, immobilized enzymes can be reused over several reaction cycles, making processes more sustainable and cost-effective. They are also suitable for long-term use due to their greater resistance to unfavourable conditions. The results for the reusability of BCL immobilized on ESMC, through 10 cycles of pNPP hydrolysis, are shown in Figure 7. BCL immobilized by adsorption was found to have great reusability, as it retained from 71.63 ± 0.17 to 85.46 ± 2.45% of its initial activity after 10 cycles, while results for covalent binding were lower. For direct covalent binding, BCL retained between 65.54 ± 1.29 and 70.98 ± 1.21% of initial activity after ten cycles, and for indirect, even lower 26.52 ± 2.34 to 28.44 ± 0.11%. The best reusability was shown when immobilized on ESMC-HCl. Jiang et al. [71] recorded a drop in activity to 5% for BCL immobilized by adsorption on the eggshell membrane after only 5 cycles of pNPP hydrolysis, while with oxidized eggshell membranes, the activity remained at 50% after 10 cycles. In the article of Işık et al. [70], the lipase activity during pNPP hydrolysis was repeated 19 times in succession to determine the reusability properties of the lipase immobilized on the eggshell membrane by cross-linking. According to the results, lipase retained 60% of its activity after 16 reuses, while its activity dropped below 50% after 18 reuses. On the other hand, Abdulla et al. [69] studied the reusability in the hydrolysis of olive oil and found a lipase activity of only 13.5% after 10 cycles when the eggshell membrane was treated with glutaraldehyde before immobilization. From all this, it is clear that the best reusability results were obtained in the present work. In addition to biochemical performance, economic aspects support the use of this biocatalyst. A recent cost analysis of enzymatic biodiesel production by packed-bed reactors [55] showed that raw material costs accounted for nearly 80% of total production costs, highlighting the critical need to reduce expenses related to feedstocks and enzymes. In our study, the use of eggshell membranes (an agro-industrial waste) as enzyme carriers significantly lowered material costs, while effective immobilization of B. cepacia lipase enabled up to five reuse cycles. Although our system was not directly aimed at biodiesel production, the observed reusability and performance in wastewater treatment demonstrate a comparable potential for cost reduction. Similar to the referenced study, enhanced recyclability of the biocatalyst played a key role in improving the economic feasibility and sustainability of the process.

Reusability of BCL immobilized by (a) adsorption, (b) direct covalent binding, and (c) indirect covalent binding. Results are shown as average value ± standard deviation of three independent determinations.

3.3.6 Selection of lipases

Statistical analysis (ANOVA) showed that there are statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) in lipases and all of the applied values and parameters, such as time, pH, temperature, organic solvent, and examined oil, when looking pH and temperature stability, stability in organic solvents, as well as substrate specificity and their combinations in treated samples (data not shown). To see possible statistically significant differences between individual immobilized lipases for all the tested characterization parameters, a post hoc Fisher test was performed, where in almost all tested parameters, there were statistically significant differences between immobilized BCL on all carriers (Tables 1–4), which was predictable considering the results of variance analysis. Generally looking, the results of the stability of immobilized BCL at different pHs, temperatures, and inorganic solvents are very varied, depending on the ESMC used, so looking at it separately, it is not possible to say which immobilized BCL lipase would be the best. However, BCL immobilized by adsorption on ESMC-HCl showed the highest activity towards all oils and lard, but also the best stability at the widest pH and, most importantly, highest stability at the optimal pH and temperature, as well as best reusability. If the activity values are further examined (Table 4), it is evident that the highest value was achieved on the ESMC-HCl, with statistically significant differences observed compared to the other two ESMC. Therefore, based on the best stability results, demonstrated reusability, and the highest activity of the lipase bound to the carrier, BCL immobilized by adsorption onto ESMC-HCl was selected for further functionalization studies. Membranes treated with HCl showed the highest efficiency compared to those treated with acetic or phosphoric acid. This effect is attributed to the more complete removal of mineral components by HCl, resulting in a cleaner and more porous collagen network with fully exposed functional groups (e.g., –NH₂, –COOH) available for enzyme binding. In contrast, acetic acid can leave behind acetate groups, while phosphoric acid can cause phosphate deposits on the membrane surface, partially blocking the binding sites and altering the surface chemistry. These differences in surface composition and porosity are consistent with our previous studies on eggshell membrane treatment, which have shown that HCl treatment maximizes organic (protein) content and preserves a membrane structure that is highly favourable for enzyme immobilization [45,46,47].

Activity of immobilized BCL

| Lipases immobilized by adsorption | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| ESMC-HCl-BCL | ESMC-HAc-BCL | ESMC-H3PO4-BCL | |

| A (U·g−1) | 646.02 ± 36.25a | 607.04 ± 8.57b | 610.48 ± 12.78a,b |

| Lipases immobilized by direct covalent binding | |||

| ESMC-HCl-BCL | ESMC-HAc-BCL | ESMC-H 3 PO 4 -BCL | |

| A (U·g−1) | 369.98 ± 3.04a | 353.66 ± 1.82b | 348.13 ± 3.68b |

| Lipases immobilized by indirect covalent binding | |||

| ESMC-HCl-BCL | ESMC-HAc-BCL | ESMC-H 3 PO 4 -BCL | |

| A (U·g−1) | 389.92 ± 2.95a | 361.01 ± 4.87b | 327.49 ± 3.03c |

A – activity of lyophilized immobilized lipases at optimal conditions (pH 9, 40°C). Results are shown as average value ± standard deviation of three independent determinations. Means with the different superscripts within the raw indicate significant differences; p < 0.05.

3.4 Evaluation of the functionality of ESMC-HCl-BCL in wastewater treatment

Lipid-rich wastewater poses significant environmental risks due to its harmful properties. Fats and oils represent the primary organic components in municipal and certain industrial wastewater streams. Major contributors to high lipid concentrations (exceeding 100 mg·L−1) include edible oil refineries, restaurants, slaughterhouses, wool processing facilities, and the food and dairy industries [122].

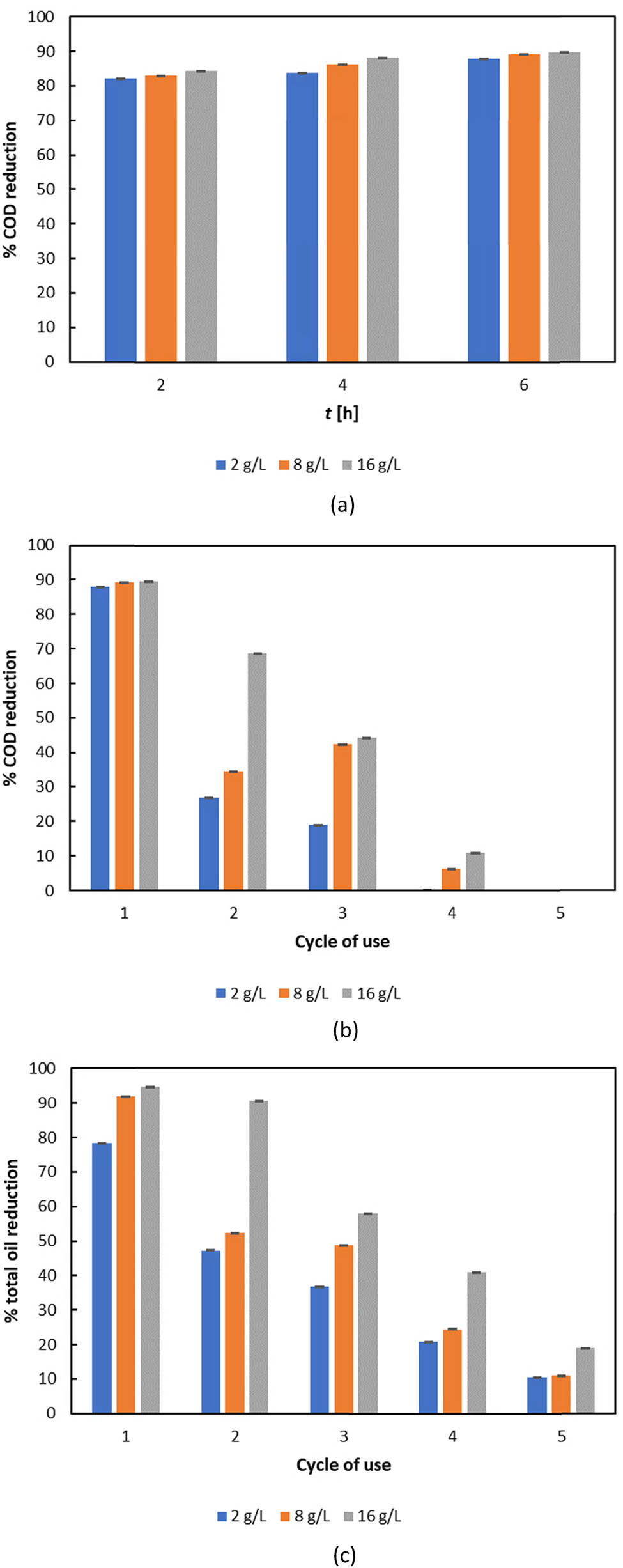

The results of the functionality testing of ESMC-HCl-BCL in oil-rich wastewater are shown in Figure 8. Based on the comparison of results in Figure 8a, the highest COD reduction was observed after 6 h of contact with ESMC-HCl-BCL (over 89% COD reduction achieved with 16 g·L−1 of material). Therefore, a contact time of 6 h was used in subsequent tests to evaluate the reusability of ESMC-HCl-BCL over multiple cycles. A noticeable decrease in COD reduction was observed after the fourth reuse cycle, with no further COD reduction detected in the fifth cycle (Figure 8b). A similar trend was observed in total oil reduction (Figure 8c). After the first cycle, approximately 95% of the total oil content was removed, whereas by the final cycle, only 18% was reduced. These findings are consistent with those reported by Yao et al. [123], who observed that immobilized lipase pretreatment of pet food industry wastewater resulted in a 65% reduction in COD and a 64% reduction in oil and grease content. In addition to these analyses, enzyme activity loss was also evaluated. The results showed that after the fifth reuse cycle, enzyme activity was 15.22% for 2 g·L−1 of ESMC-HCl-BCL, 20.71% for 8 g·L−1, and 10.92% for 16 g·L−1. This decrease in performance was accompanied by a significant decrease in the remaining enzyme activity after the fifth cycle (e.g., to 10.92–20.71% of the original activity, depending on the ESMC-HCl-BCL dosage). Several factors could contribute to this loss of activity: (i) partial enzyme inactivation – several studies have shown that repeated cycles of immobilized lipase use can lead to reduced enzyme activity due to denaturation, conformational changes, or blockage of the active site by accumulated reaction by-products or impurities in the wastewater [123,124]. For example, loss of activity after several cycles has been attributed to both structural changes in the enzyme and gradual denaturation, especially in harsh or oily environments [88,125]; (ii) fouling of the biocatalyst – fouling is widely reported as one of the main reasons for performance degradation when reusing immobilized enzymes in oily or complex wastewaters. The accumulation of fats, oils, and organic material on the surface of the immobilized matrix can hinder substrate diffusion and shield the active enzyme sites, reducing the overall catalytic capacity [124,126,127]. These phenomena have been quantitatively described in the literature, e.g., by Yao et al. [123], who found that immobilized lipase can be reused up to four cycles, but decreases significantly thereafter, and in a recent study on magnetic carriers, which showed greatly reduced catalytic activity after the fourth reuse – especially when fouling and high surface loading were present [124]. In addition, extensive reviews and modelling studies dealing with fouling of biocatalysts and membranes in real wastewater systems have highlighted the need for regeneration strategies or replacement [127,128]. All these findings indicate that ESMC-HCl-BCL can be effectively used for the pretreatment of oily wastewater.

Evaluation of functionality of ESMC-HCl-BCL in wastewater treatment (a) COD reduction over time, (b) COD reduction over multiple reuse cycles, and (c) total oil reduction over multiple reuse cycles. Results are shown as average value ± standard deviation of three independent determinations.

It is important to note that while ESMC-HCl-BCL demonstrates effective pretreatment of oily wastewater for up to four reuse cycles, the observed decrease in enzyme activity and COD removal efficiency beyond this point represents a trade-off for potential industrial applications. Maintaining constant treatment performance would require frequent regeneration or replacement of the biocatalyst, which could impact both process costs and operational sustainability. The development of effective regeneration strategies, such as purification protocols to reduce fouling or the optimization of enzyme immobilization to improve stability, is therefore essential for practical implementation. In addition, future research should investigate the potential leaching of enzymes during treatment and explore strategies to minimize this leaching to ensure catalyst longevity and environmental safety. Enzyme activity has only been measured at the end of each reuse cycle, while activity in the treated wastewater itself has not been assessed. Recognizing and systematically addressing this limitation will be crucial to expand the application of ESMC-HCl-BCL in real wastewater treatment systems.

4 Conclusions

In continuation of efforts to fully utilize waste eggshells, this research investigated the ability of the eggshell membrane for immobilization of lipase using both adsorption and covalent binding methods to achieve a cost-effective zero-waste model of transformation of eggshells. Immobilized BCL showed a shift in pH and temperature optimum, better temperature stability at high temperatures, and improved storage stability compared to free lipases, as well as retention of up to 85% of initial activity through 10 reusability cycles, with adsorption proving as the most effective method. The study demonstrated that ESMC-HCl-BCL is highly effective in the pretreatment of oil-rich wastewater, achieving over 89% COD reduction and 95% total oil removal after 6 h of contact time with 16 g·L−1 of material. However, the reusability tests revealed a gradual decline in performance, with a significant drop in COD and oil reduction after the fourth cycle, and minimal activity remaining by the fifth cycle. Enzyme activity measurements further confirmed this trend, with residual activity ranging from 10.92 to 20.71% depending on the concentration used. Overall, ESMC-HCl-BCL presents a promising option for the short-term enzymatic pretreatment of oily wastewater, although its reusability remains limited over extended cycles. While ESMC-HCl-BCL shows promising performance, its declining efficiency after four reuse cycles emphasizes the need for regeneration strategies and leaching controls that will be crucial for sustainable, large-scale application in wastewater treatment.

Further process design research is needed for emerging wastewater treatment technologies, which are currently gaining momentum. Ultimately, these developments must progress from laboratory-scale studies to full-scale industrial implementation. To advance towards industrial application, future research should focus on scaling up carrier production and immobilization processes, i.e., standardizing the washing, separation, drying, and enzyme coupling steps to ensure consistent carrier quality and performance. Continuous or semi-continuous pilot-scale systems need to be evaluated under real wastewater conditions to assess durability, resistance to fouling, contaminant removal efficiency, and re-use of the enzymes over longer cycles. Extending the scope to other lipases and enzyme classes will test the versatility of the platform. The integration of techno-economic and life cycle assessments will reveal bottlenecks (e.g., energy consumption, carrier lifetime), while strategies such as by-product utilization (e.g., CaCl₂ recovery), carrier regeneration, and regulatory compliance planning are essential for an environmentally friendly, circular, and scalable application.

-

Funding information: This work has been fully supported by the Croatian Science Foundation under the project IP-2020-02-6878.

-

Author contributions: Marta Ostojčić: conceptualization, investigation, methodology, formal analysis, visualization, and writing – original draft; Marija Stjepanović: investigation, methodology, formal analysis, and writing – original draft; Ivica Strelec: conceptualization, investigation, methodology, supervision, validation, and writing – review and editing; Natalija Velić: writing – review and editing; Mirna Brekalo: formal analysis; Zita Šereš: writing – review and editing; Nikola Maravić: writing – review and editing; Nam Nghiep Tran: writing – review and editing; Volker Hessel: writing – review and editing; Sandra Budžaki: conceptualization, funding acquisition, investigation, project administration, resources, supervision, and writing – review and editing.

-

Conflict of interest: Volker Hesse is the Editor-in-Chief of Green Processing and Synthesis. Nam Nghiep Tran is the Deputy Editor-in-Chief of Green Processing and Synthesis. The other authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] Waheed M, Yousaf M, Shehzad A, Inam-Ur-Raheem M, Khan MKI, Khan MR, et al. Channelling eggshell waste to valuable and utilizable products: A comprehensive review. Trends Food Sci Technol. 2020;106:78–90. 10.1016/j.tifs.2020.10.009.Search in Google Scholar

[2] Froning G, Bergquist D. Utilization of inedible eggshells and technical egg-white using extrusion technology. Poult Sci. 1990;69:2051–3. 10.3382/ps.0692051.Search in Google Scholar

[3] Gennadios A, Hanna MA, Kollengode ANR. Extruded mixtures of spent hens and soybean meal. Trans ASAE. 2000;43:375–8.10.13031/2013.2714Search in Google Scholar

[4] Sim J, Awyong L, Bragg D. Utilization of eggshell waste by the laying hen. Poult Sci. 1983;62:2227–9. 10.3382/ps.0622227.Search in Google Scholar

[5] Sim J, Awyong L, Bragg D. Utilization of eggshell waste for poultry feed. Poult Sci. 1983;62:1502–2.10.3382/ps.0622227Search in Google Scholar

[6] Chowdhury S, Das P. Utilization of a Domestic Waste - Eggshells for Removal of Hazardous Malachite Green from Aqueous Solutions. Env Prog Sustain Energy. 2012;31:415–25. 10.1002/ep.10564.Search in Google Scholar

[7] Guru PS, Dash S. Sorption on eggshell waste-A review on ultrastructure, biomineralization and other applications. Adv Colloid Interface Sci. 2014;209:49–67. 10.1016/j.cis.2013.12.013.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[8] Tsai W-T, Hsien K-J, Hsu H-C, Lin C-M, Lin K-Y, Chiu C-H. Utilization of ground eggshell waste as an adsorbent for the removal of dyes from aqueous solution. Bioresour Technol. 2008;99:1623–9. 10.1016/j.biortech.2007.04.010.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] Habte L, Shiferaw N, Thriveni T, Mulatu D, Lee M, Jung S, et al. Removal of Cd(II) and Pb(II) from wastewater via carbonation of aqueous Ca(OH)2 derived from eggshell. PROCESS Saf Env Prot. 2020;141:278–87. 10.1016/j.psep.2020.05.036.Search in Google Scholar

[10] Ince OK, Ince M, Yonten V, Goksu A. A food waste utilization study for removing lead(II) from drinks. Food Chem. 2017;214:637–43. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2016.07.117.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] Vijayaraghavan K, Joshi UM. Chicken eggshells remove Pb(II) ions from synthetic wastewater. Env Eng Sci. 2013;30:67–73. 10.1089/ees.2012.0038.Search in Google Scholar

[12] Metwally SS, Ayoub RR, Aly HF. Utilization of low-cost sorbent for removal and separation of 134Cs, 60Co and 152+154 Eu radionuclides from aqueous solution. J Radioanal Nucl Chem. 2014;302:441–9. 10.1007/s10967-014-3185-z.Search in Google Scholar

[13] Ahmad W, Sethupathi S, Kanadasan G, Iberahim N, Bashir MJK, Munusamy Y. Adsorption of SO2 and H2S by sonicated raw eggshell. In Proceedings of the Materials Today-Proceedings. Vol. 31, Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2020. p. 36–4210.1016/j.matpr.2020.01.084Search in Google Scholar

[14] Sacia ER, Ramkumar S, Phalak N, Fan L-S. Synthesis and regeneration of sustainable CaO sorbents from chicken eggshells for enhanced carbon dioxide capture. ACS Sustain Chem Eng. 2013;1:903–9. 10.1021/sc300150k.Search in Google Scholar

[15] Balaz M. Ball milling of eggshell waste as a green and sustainable approach: A review. Adv Colloid Interface Sci. 2018;256:256–75. 10.1016/j.cis.2018.04.001.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[16] Kamkum P, Vittayakorn W, Seeharaj P, Woramongkolchai S, Muanghlua R, Vittayakorn N. Utilization of eggshell as a low-cost precursor for synthesizing calcium niobate ceramic. Green Mater. 2018;6:108–16. 10.1680/jgrma.18.00049.Search in Google Scholar

[17] Muniz Ferreira JR, da Rocha DN, Leme Louro LH, Prado da Silva MH. Phosphating of calcium carbonate for obtaining hydroxyapatite from the ostrich egg shell. In: Antoniac I, Cavalu S, Traistaru T, editors. Proceedings of the Bioceramics. Vol. 25, Durnten-Zurich: Trans Tech Publications Ltd; 2014. Vol. 587, p. 69–73.10.4028/www.scientific.net/KEM.587.69Search in Google Scholar

[18] Nayar S, Guha A. Waste utilization for the controlled synthesis of nanosized hydroxyapatite. Mater Sci Eng C-Biomim Supramol Syst. 2009;29:1326–9. 10.1016/j.msec.2008.10.002.Search in Google Scholar

[19] Ummartyotin S, Tangnorawich B. Utilization of eggshell waste as raw material for synthesis of hydroxyapatite. Colloid Polym Sci. 2015;293:2477–83. 10.1007/s00396-015-3646-0.Search in Google Scholar

[20] Asikin-Mijan N, Lee HV, Taufiq-Yap YH. Synthesis and catalytic activity of hydration-dehydration treated clamshell derived CaO for biodiesel production. Chem Eng Res Des. 2015;102:368–77. 10.1016/j.cherd.2015.07.002.Search in Google Scholar

[21] Boro J, Deka D, Thakur AJ. A review on solid oxide derived from waste shells as catalyst for biodiesel production. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2012;16:904–10. 10.1016/j.rser.2011.09.011.Search in Google Scholar

[22] El-Gendy NS, Deriase SF. Waste eggshells for production of biodiesel from different types of waste cooking oil as waste recycling and a renewable energy process. Energy Sources Part -Recov Util Env Eff. 2015;37:1114–24. 10.1080/15567036.2014.963745.Search in Google Scholar

[23] Hangun-Balkir Y. Green biodiesel synthesis using waste shells as sustainable catalysts with camelina sativa oil. J Chem. 2016;2016:6715232. 10.1155/2016/6715232.Search in Google Scholar

[24] Putra MD, Ristianingsih Y, Jelita R, Irawan C, Nata IF. Potential waste from palm empty fruit bunches and eggshells as a heterogeneous catalyst for biodiesel production. RSC Adv. 2017;7:55547–54. 10.1039/c7ra11031f.Search in Google Scholar

[25] Wei Z, Xu C, Li B. Application of waste eggshell as low-cost solid catalyst for biodiesel production. Bioresour Technol. 2009;100:2883–5. 10.1016/j.biortech.2008.12.039.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[26] Gomes MG, Pasquini D. Utilization of eggshell waste as an adsorbent for the dry purification of biodiesel. Env Prog Sustain Energy. 2018;37:2093–9. 10.1002/ep.12870.Search in Google Scholar

[27] Ongo EA, Valdecanas CS, Gutierrez BJM. Utilization of agricultural wastes for oil spills remediation. In: Clemente RC, editor. Proceedings of the 3RD International Conference on Agriculture And Forestry (ICOAF) 2016: Sustainable Agriculture and Forestry as Essential Response to the Challenges of Global Food Security and Environmental Stability. Pitakotte: Int Inst Knowledge Management-Tiikm; 2016. p. 51–60.10.17501/icoaf.2016.2106Search in Google Scholar

[28] Imron MA, Ahkam DNI, Hidayat AW. DECO FRECASE (drywall eco-friendly from eggshell and cane bagasse) as an innovation of eco-friendly interior construction. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference on Material Engineering and Advanced Manufacturing Technology. Vol. 282, Bristol: IOP Publishing Ltd; 2017. p. 012009.10.1088/1757-899X/282/1/012009Search in Google Scholar

[29] Jannat N, Al-Mufti RL, Hussien A, Abdullah B, Cotgrave A. Influences of agro-wastes on the physico-mechanical and durability properties of unfired clay blocks. Constr Build Mater. 2022;318:126011. 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2021.126011.Search in Google Scholar

[30] Jhatial AA, Goh WI, Mohamad N, Sohu S, Lakhiar MT. Utilization of palm oil fuel ash and eggshell powder as partial cement replacement - A review. Civ Eng J-Tehran. 2018;4:1977–84. 10.28991/cej-03091131.Search in Google Scholar

[31] Jhatial AA, Goh WI, Mo KH, Sohu S, Bhatti IA. Green and sustainable concrete - The potential utilization of rice husk ash and egg shells. Civ Eng J-Tehran. 2019;5:74–81. 10.28991/cej-2019-03091226.Search in Google Scholar

[32] Nandhini K, Karthikeyan J. Sustainable and greener concrete production by utilizing waste eggshell powder as cementitious material-A review. Constr Build Mater. 2022;335:127482. 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2022.127482.Search in Google Scholar

[33] Nandhini K, Karthikeyan J. Effective utilization of waste eggshell powder in cement mortar. In Proceedings of the Materials Today-Proceedings. Vol. 61, Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2022. p. 428–32.10.1016/j.matpr.2021.11.328Search in Google Scholar

[34] Sathiparan N. Utilization prospects of eggshell powder in sustainable construction material-A review. Constr Build Mater. 2021;293:123465. 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2021.123465.Search in Google Scholar

[35] Sharma G, Singh K. Recycling and utilization of agro-food waste ashes: Syntheses of the glasses for wide-band gap semiconductor applications. J Mater Cycles Waste Manag. 2019;21:801–9. 10.1007/s10163-019-00839-z.Search in Google Scholar

[36] Shekhawat P, Sharma G, Singh RM. Strength behavior of alkaline activated eggshell powder and flyash geopolymer cured at ambient temperature. Constr Build Mater. 2019;223:1112–22. 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2019.07.325.Search in Google Scholar

[37] Shiferaw N, Habte L, Thenepalli T, Ahn JW. Effect of eggshell powder on the hydration of cement paste. Materials. 2019;12:2483. 10.3390/ma12152483.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[38] Yadav R, Dwivedi VK, Dwivedi SP. Eggshell and rice husk ash utilization as reinforcement in development of composite material: A review. In Proceedings of the Materials Today-Proceedings. Vol. 43, Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2021. p. 426–33.10.1016/j.matpr.2020.11.717Search in Google Scholar

[39] Yang D, Zhao J, Ahmad W, Amin MN, Aslam F, Khan K, et al. Potential use of waste eggshells in cement-based materials: A bibliographic analysis and review of the material properties. Constr Build Mater. 2022;344:128143. 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2022.128143.Search in Google Scholar

[40] Rasheed SP, Shivashankar M, Dev S, Azeem AK. Treatment of biowaste to pharmaceutical excipient. In Proceedings of the Materials Today-Proceedings. Vol. 15, Amsterdam: Elsevier Science BV; 2019. p. 316–22.10.1016/j.matpr.2019.05.011Search in Google Scholar

[41] Jana S, Das P, Mukherjee J, Banerjee D, Ghosh PR, Kumar Das P, et al. Waste-derived biomaterials as building blocks in the biomedical field. J Mater Chem B. 2022;10:489–505. 10.1039/d1tb02125g.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[42] Opris H, Dinu C, Baciut M, Baciut G, Mitre I, Crisan B, et al. The influence of eggshell on bone regeneration in preclinical in vivo studies. Biology. 2020;9:476. 10.3390/biology9120476.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[43] Razak SA, Isa NAAM, Bakar SASA. Review on eggshell waste in tissue engineering application. Int J Integr Eng. 2022;14:64–80.10.30880/ijie.2022.14.04.007Search in Google Scholar

[44] Waheed M, Butt MS, Shehzad A, Adzahan NM, Shabbir MA, Rasul Suleria HA, et al. Eggshell calcium: A cheap alternative to expensive supplements. Trends Food Sci Technol. 2019;91:219–30. 10.1016/j.tifs.2019.07.021.Search in Google Scholar

[45] Strelec I, Ostojčić M, Brekalo M, Hajra S, Kim H-J, Stanojev J, et al. Transformation of eggshell waste to egg white protein solution, calcium chloride dihydrate, and eggshell membrane powder. Green Process Synth. 2023;12:20228151. 10.1515/gps-2022-8151.Search in Google Scholar

[46] Strelec I, Peranović K, Ostojčić M, Aladić K, Pavlović H, Djerdj I, et al. Eggshell waste transformation to calcium chloride anhydride as food-grade additive and eggshell membranes as enzyme immobilization carrier. Green Process Synth. 2024;13:20230254. 10.1515/gps-2023-0254.Search in Google Scholar

[47] Strelec I, Tomičić K, Zajec M, Ostojčić M, Budžaki S. Eggshell-waste-derived calcium acetate, calcium hydrogen phosphate and corresponding eggshell membranes. Appl Sci. 2023;13:7372. 10.3390/app13137372.Search in Google Scholar

[48] Mulinari J, Oliveira JV, Hotza D. Lipase immobilization on ceramic supports: An overview on techniques and materials. Biotechnol Adv. 2020;42:107581. 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2020.107581.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[49] Sarmah N, Revathi D, Sheelu G, Yamuna Rani K, Sridhar S, Mehtab V, et al. Recent advances on sources and industrial applications of lipases. Biotechnol Prog. 2018;34:5–28. 10.1002/btpr.2581.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[50] Ismail AR, Baek K-H. Lipase immobilization with support materials, preparation techniques, and applications: Present and future aspects. Int J Biol Macromol. 2020;163:1624–39. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.09.021.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[51] Girelli AM, Astolfi ML, Scuto FR. Agro-industrial wastes as potential carriers for enzyme immobilization: A review. Chemosphere. 2020;244:125368. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.125368.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[52] Thangaraj B, Solomon PR. Immobilization of lipases – A review. Part I: Enzyme immobilization. ChemBioEng Rev. 2019;6:157–66. 10.1002/cben.201900016.Search in Google Scholar

[53] Jesionowski T, Zdarta J, Krajewska B. Enzyme immobilization by adsorption: A review. Adsorption. 2014;20:801–21. 10.1007/s10450-014-9623-y.Search in Google Scholar

[54] Budžaki S, Velić N, Ostojčić M, Stjepanović M, Rajs BB, Šereš Z, et al. Waste management in the agri-food industry: The conversion of eggshells, spent coffee grounds, and brown onion skins into carriers for lipase immobilization. Foods. 2022;11:409. 10.3390/foods11030409.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[55] Budžaki S, Miljić G, Sundaram S, Tišma M, Hessel V. Cost analysis of enzymatic biodiesel production in small-scaled packed-bed reactors. Appl Energy. 2018;210:268–78. 10.1016/j.apenergy.2017.11.026.Search in Google Scholar

[56] Sepabeads | Sigma-Aldrich Available online: https://www.sigmaaldrich.com/HR/en/search/sepabeads?focus=products&page=1&perpage=30&sort=relevance&term=sepabeads&type=product (accessed on 22 May 2025).Search in Google Scholar

[57] Girelli AM, Scuto FR. Eggshell membrane as feedstock in enzyme immobilization. J Biotechnol. 2021;325:241–9. 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2020.10.016.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[58] Pundir C, Bhambi M, Chauhan N. Chemical activation of egg shell membrane for covalent immobilization of enzymes and its evaluation as inert support in urinary oxalate determination. Talanta. 2009;77:1688–93. 10.1016/j.talanta.2008.10.004.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[59] Zhang G, Liu D, Shuang S, Choi MMF. A homocysteine biosensor with eggshell membrane as an enzyme immobilization platform. Sens Actuat B Chem. 2006;114:936–42. 10.1016/j.snb.2005.08.011.Search in Google Scholar

[60] Aini BN, Siddiquee S, Ampon K, Rodrigues KF, Suryani S. Development of glucose biosensor based on ZnO nanoparticles film and glucose oxidase-immobilized eggshell membrane. Sens Bio-Sens Res. 2015;4:46–56. 10.1016/j.sbsr.2015.03.004.Search in Google Scholar

[61] Choi MMF, Pang WSH, Wu X, Xiao D. An optical glucose biosensor with eggshell membrane as an enzyme immobilisation platform. Analyst. 2001;126:1558–63. 10.1039/b103205b.Search in Google Scholar

[62] Li B, Lan D, Zhang Z. Chemiluminescence flow-through biosensor for glucose with eggshell membrane as enzyme immobilization platform. Anal Biochem. 2008;374:64–70. 10.1016/j.ab.2007.10.036.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[63] Wu B, Zhang G, Shuang S, Choi MMF. Biosensors for determination of glucose with glucose oxidase immobilized on an eggshell membrane. Talanta. 2004;64:546–53. 10.1016/j.talanta.2004.03.050.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[64] D’Souza SF, Kumar J, Jha SK, Kubal BS. Immobilization of the urease on eggshell membrane and its application in biosensor. Mater Sci Eng C. 2013;33:850–4. 10.1016/j.msec.2012.11.010.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[65] Tembe S, Kubal BS, Karve M, D’Souza SF. Glutaraldehyde activated eggshell membrane for immobilization of tyrosinase from amorphophallus companulatus: Application in construction of electrochemical biosensor for dopamine. Anal Chim Acta. 2008;612:212–7. 10.1016/j.aca.2008.02.031.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[66] Zhang Y, Wen G, Zhou Y, Shuang S, Dong C, Choi MMF. Development and analytical application of an uric acid biosensor using an uricase-immobilized eggshell membrane. Biosens Bioelectron. 2007;22:1791–7. 10.1016/j.bios.2006.08.038.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[67] Choi MMF, Yiu TP. Immobilization of beef liver catalase on eggshell membrane for fabrication of hydrogen peroxide biosensor. Enzyme Microb Technol. 2004;34:41–7. 10.1016/j.enzmictec.2003.08.005.Search in Google Scholar

[68] Kessi E, Arias JL. Using natural waste material as a matrix for the immobilization of enzymes: Chicken eggshell membrane powder for β-galactosidase immobilization. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2019;187:101–15. 10.1007/s12010-018-2805-4.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[69] Abdulla R, Sanny SA, Derman E. Stability studies of immobilized lipase on rice husk and eggshell membrane. IOP Conf Ser Mater Sci Eng. 2017;206:012032. 10.1088/1757-899X/206/1/012032.Search in Google Scholar