Abstract

The crosslinking network and mechanical properties of Taraxacum kok-saghyz natural rubber (TKNR), a promising alternative to traditional natural rubber (NR), have been underexplored. In this work, TKNR, NR, and their blends (TKNR-NR) were systematically investigated to reveal their unique crosslinking network and mechanical behaviors. Equilibrium swelling tests were conducted to measure the crosslinking density (v), molecular weight between crosslinks (M c), and swelling ratio (Q). The processing rheological properties of Taraxacum kok-saghyz rubber were analyzed using rubber process analyzer testing. The vulcanization behavior and mechanical performance were analyzed using standard mechanical tests, the Mooney-Rivlin equation, tube model fitting, and dynamic mechanical analysis, thereby elucidating the crosslinking network characteristics of TKNR and their correlation with mechanical properties. Results show that TKNR possesses a higher crosslinking density (v) and a lower M c compared to NR, resulting in reduced stiffness and strength but enhanced flexibility, elongation at break, and storage modulus. TKNR’s high crosslink density and low molecular weight between crosslinks increase hardness but restrict chain mobility, inhibiting strain-induced crystallization and reducing tensile strength. These differences are attributed to the predominance of physical entanglements (G e) over chemical crosslinks (G c) in TKNR, while NR maintains a balanced G c and G e. Blending TKNR with NR yields composites with intermediate crosslinking network and mechanical properties, achieving a balance of the two materials’ advantages.

1 Introduction

Natural rubber (NR) has played a critical role in various industrial applications. However, as global dependence on natural resources increases, the primary source, the Brazilian rubber tree (Hevea brasiliensis), faces challenges such as limited planting area, susceptibility to pests and diseases, and insufficient production capacity. As a result, finding alternative rubber sources has become a research focus (1–3). Taraxacum kok-saghyz natural rubber (TKNR), due to its short growth cycle and high adaptability, has emerged as a promising alternative to NR (4–8).

The excellent mechanical properties of NR are one of the key reasons for its widespread use, and these properties are largely dependent on its crosslinking network structure (9–11). Parameters such as crosslink density, network molecular weight, and chain segment distribution directly influence the elasticity, strength, and durability of rubber (12). Therefore, to improve the application and modification of TKNR, it is necessary to study the crosslinking network structure and mechanical properties of TKNR. Due to the existence of multiple functional groups in its molecular structure, TKNR tends to form a crosslinking network different from that of NR during vulcanization. These functional groups not only increase the number of reaction sites but also may change the chain length between the crosslinking points, thereby affecting the overall performance of the rubber (13,14).

In recent years, researchers have increasingly focused on TKNR’s vulcanization process to optimize its mechanical properties (15,16). Studies have shown that the crosslinking density of TKNR can be significantly improved by adjusting the type and dosage of vulcanizing agents, thereby improving its mechanical strength and durability (17,18). Junkong et al. (19,20) demonstrated that non-rubber components (e.g., proteins) in TKNR serve as intrinsic reinforcing fillers, significantly impacting its sulfur-crosslinked rubber’s strain-induced crystallization and stress-softening behaviors.

Although researchers have done many studies on TKNR, there are few studies to explore the relationship between its mechanical properties and its crosslinking network, particularly regarding covalent bonds. In this study, we assess the crosslinking network parameters of TKNR through equilibrium swelling tests, with NR as a reference for comparison. Crosslinking network differences between TKNR and NR are evaluated from multiple perspectives, encompassing vulcanization characteristics, static and dynamic mechanical properties. Further, the mechanical properties of TKNR, NR, and their blends (TKNR-NR) are explored to elucidate the relationship with crosslinking network. By analyzing the influence of parameters such as crosslinking density, network chain molecular weight, chain segment distribution, and covalent crosslinking bonds on mechanical properties, the influence mechanism on the elasticity, strength, and durability of rubber is revealed, which provides a theoretical basis for rubber materials in different applications.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Materials

Taraxacum kok-saghyz (TKS) for TKNR extraction was obtained from Inner Mongolia Linong Chaohe Seed Industry Co., Ltd, and NR was sourced from the Jinlian Processing Division of Hainan Natural Rubber Industry Group Co., Ltd. Potassium hydroxide (KOH, 90%) was supplied by Guangzhou Chemical Reagent Factory. Pectinase (500 U/mg), cellulase (400 U/mg), and sodium citrate buffer (0.5 M, pH 5.5) were purchased from Aladdin Reagent (Shanghai) Co., Ltd. Zinc oxide (ZnO, AR, 99%), stearic acid (SA, 95%), 2-mercaptobenzothiazole (MBT, 98%), and sulfur (S, AR, ≥99.5%) were commercial-grade reagents supplied by Shanghai Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. Toluene (AR, ≥99.5%) was provided by Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd.

2.2 Extraction of TKS rubber

Three hundred grams of cleaned and dried TKS roots were crushed, boiled in 100°C water for 30 min, and filtered through a 178 µm (80-mesh) sieve. This process was repeated three times, yielding dried residue and inulin from the filtrate. The residue was treated with 60 mg KOH/g dry root in 500 mL deionized water at 120°C for 30 min, filtered, and acidified to isolate lignin. The residue was washed, soaked in 2 L deionized water at 4°C overnight, and re-filtered. It was then mixed with 1.5 L deionized water, pectinase, and cellulase (42 and 27.5 mg·g−1 dry root, respectively) in citrate buffer (pH 5.5). The mixture was stirred at 50°C, 200 rpm for 48–72 h. After centrifugation at 4°C, 5,000 rpm for 30 min, the floating rubber was collected, dried, and stored.

2.3 Sample preparation

NR, TKNR, and TKNR-NR (NR:TKNR = 1:1) blends (150 g each) were individually plasticized using a two-roll mill (KY-3220D-160, Dongguan Kaiyan Machinery Technology Co., Ltd, China). SA (0.75 g), ZnO (9 g), and MBT (0.75 g) were sequentially added, followed by the incorporation of S (5.25 g) to complete the compound formulation. The compound was subjected to vulcanization testing using a rotorless vulcaniometer, after which it was cured in a plate vulcanizing press according to the vulcanization parameters to obtain the final vulcanized rubber.

2.4 Testing and characterization

2.4.1 Vulcanization characteristics

The vulcanization characteristics of the compound rubber were evaluated following the GB/T 9869-2014 standard using a rotorless rheometer (MDR-2000E, Wuxi Liyuan Electronic Chemical Equipment Co., Ltd, China) at 145°C. From the resulting vulcanization curve, minimum torque (M L), maximum torque (M H), torque difference (ΔH = M H–M L), scorch time (t 10), and optimal vulcanization time (t 90) were measured.

2.4.2 Characterization of the rheological properties

The rheological properties were characterized using an rubber process analyzer Elite rheometer (TA Instruments, USA) through frequency and strain sweeps. For the frequency sweep, a strain of 7% was applied over a frequency range of 1–1,500 cpm (1–25 Hz) at a testing temperature of 60°C. For the strain sweep, a frequency of 1 Hz was maintained at 60°C, with a strain range of 1–1,000%.

2.4.3 Crosslinking parameters

The equilibrium swelling method was used to measure and calculate the swelling ratio (Q), molecular weight between crosslinks (M c), and crosslink density (v) of the samples (21–24). The calculation methods are described in Eqs. (1)–(3):

In the above equations, m s is the mass of the solvent in the swollen gel, m r is the mass of the rubber sample in the swollen gel, ρ s is the density of the solvent, and ρ r is the density of the rubber sample.

In Eq. 2 φ r is the volume fraction of the polymer in the swollen gel, defined as 1/Q; V s is the molar volume of the solvent; and χ s is the Huggins constant.

In this context, the values used are as follows: ρ r = 0.930 g·cm−3, ρ s = 0.886 g·cm−3, V s = 106.9 cm3·mol−1, and χ s = 0.39.

2.4.4 Conventional mechanical properties

(1) Conventional mechanical parameters: Type I dumbbell samples were prepared according to GB/T 528-2009 and tested on a universal testing machine (ETM103C, Shenzhen Wante Testing Equipment Co., China) at a tensile speed of 500 mm·min−1 to obtain stress–strain curves, tensile strength, elongation at break, and constant strain stress.

(2) Cyclic strain incremental stretching: Type I dumbbell samples, prepared as per GB/T 528-2009, were incrementally stretched to 100%, 200%, 300%, 400%, and 500% strain at a rate of 500 mm·min−1, with each cycle unloaded to zero stress before the next increment.

(3) Tear strength: Tear resistance of rectangular vulcanized rubber samples was tested following GB/T 529-2008 on a universal testing machine at a displacement rate of 500 mm·min−1.

(4) Shore A hardness: Shore A hardness was measured in accordance with GB/T 531.1-2008 using a Shore A durometer (0–100 HA, Yueqing Aidebao Instrument Co., China).

2.4.5 Dynamic mechanical analysis (DMA)

DMA was conducted on a Q800 DMA (TA Instruments, USA) under a nitrogen atmosphere, with a strain of 0.1%, frequency of 10 Hz, temperature range from −80°C to 80°C, and heating rate of 3°C·min−1.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Analysis of rubber crosslinking network structure

The crosslinking network parameters of vulcanized NR, TKNR, and their blend (TKNR-NR) are shown in Table 1. According to Table 1, NR exhibits a lower effective crosslinking density (v), along with a higher swelling volume (Q) and network chain molecular weight (M c), compared to TKNR. These differences are attributed to intrinsic variations in their molecular structures. Specifically, TKNR contains a greater number of reactive sites or functional groups, which facilitate crosslink formation during vulcanization, thereby increasing its crosslinking density. In contrast, the more ordered molecular structure of NR limits the availability of crosslinking sites.

Crosslinking network structure parameters of vulcanized rubber

| Sample | Swelling volume (Q) | Molecular weight between crosslinks (M c) (g·mol−1) | Crosslink density (v) (mol·cm−3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| NR | 5.41 | 9,452 | 97.33 |

| TKNR-NR | 5.02 | 7,373 | 124.77 |

| TKNR | 4.33 | 5,255 | 175.07 |

Additionally, the higher reactivity of TKNR promotes the formation of a denser crosslinking network. However, this results in shorter segments between crosslinks, leading to a lower molecular weight. Furthermore, the non-rubber components in TKNR act as vulcanization accelerators, enhancing crosslinking reactions and further increasing the crosslinking density (25). However, these non-rubber components may also disrupt the arrangement and crystallinity of rubber chains, leading to an increase in the swelling volume. The rapid crosslinking reactions of TKNR result in a more compact crosslinking network, whereas the slower crosslinking of NR, dominated by its longer chains, produces a network with higher molecular weights between crosslinking points but a lower overall crosslinking density. The crosslinking network parameters of the TKNR-NR blend fall between those of the two individual rubbers, reflecting a partial balance of the reactivity and structural characteristics of TKNR and NR.

3.2 Vulcanization characteristics analysis

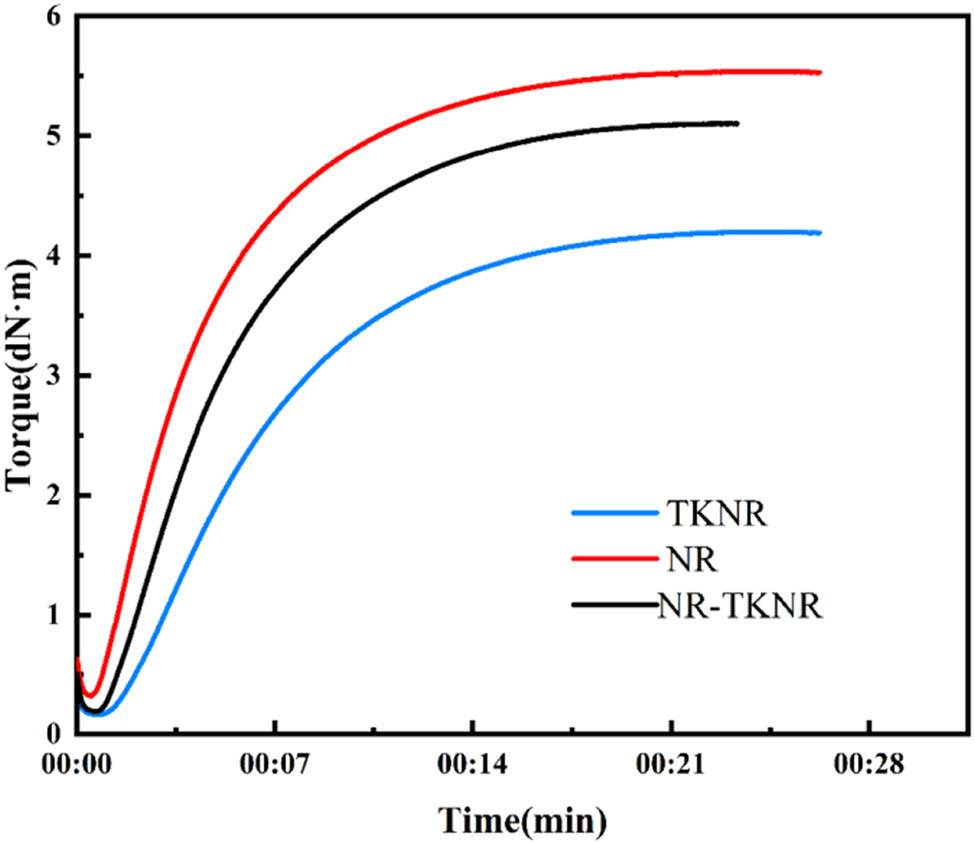

The vulcanization characteristics of the compounded rubbers are summarized in Table 2, with the corresponding vulcanization curves presented in Figure 1 Compared to TKNR, NR exhibits higher values for minimum torque (M L), maximum torque (M H), and torque difference (ΔM). These results indicate that NR forms a denser and more rigid crosslinking network. In contrast, TKNR shows lower M L, M H, and ΔM values, suggesting its looser crosslinking network. This difference is attributed to the higher number of reactive sites and functional groups in TKNR, which promote the formation of shorter crosslinks during the vulcanization process (26). The parameters of the TKNR-NR blend fall between those of the individual rubbers, indicating a balanced crosslinking network that integrates the characteristics of both NR and TKNR.

Vulcanization characteristics of compounded rubbers

| Sample | Minimum torque (M L, dN·m) | Maximum torque (M H, dN·m) | Torque difference (ΔM = M H–M L, dN·m) | Scorch time (t 10, min) | Vulcanization time (t 90, min) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NR | 0.32 | 5.54 | 5.22 | 1.19 | 11.06 |

| TKNR | 0.16 | 4.20 | 4.04 | 2.16 | 13.33 |

| TKNR-NR | 0.19 | 5.11 | 4.92 | 1.45 | 11.58 |

Curing curves of the rubber compounds.

Furthermore, TKNR exhibits a longer scorch time (t 10) and vulcanization time (t 90), reflecting a slower vulcanization process. In contrast, NR and the TKNR-NR blend show shorter t 10 and t 90 values, suggesting a faster crosslinking process. The slower crosslinking rate in TKNR contributes to a higher crosslinking density (v) and a lower molecular weight between crosslinks (M c), whereas NR displays the opposite trend.

3.3 Conventional mechanical properties of vulcanizates

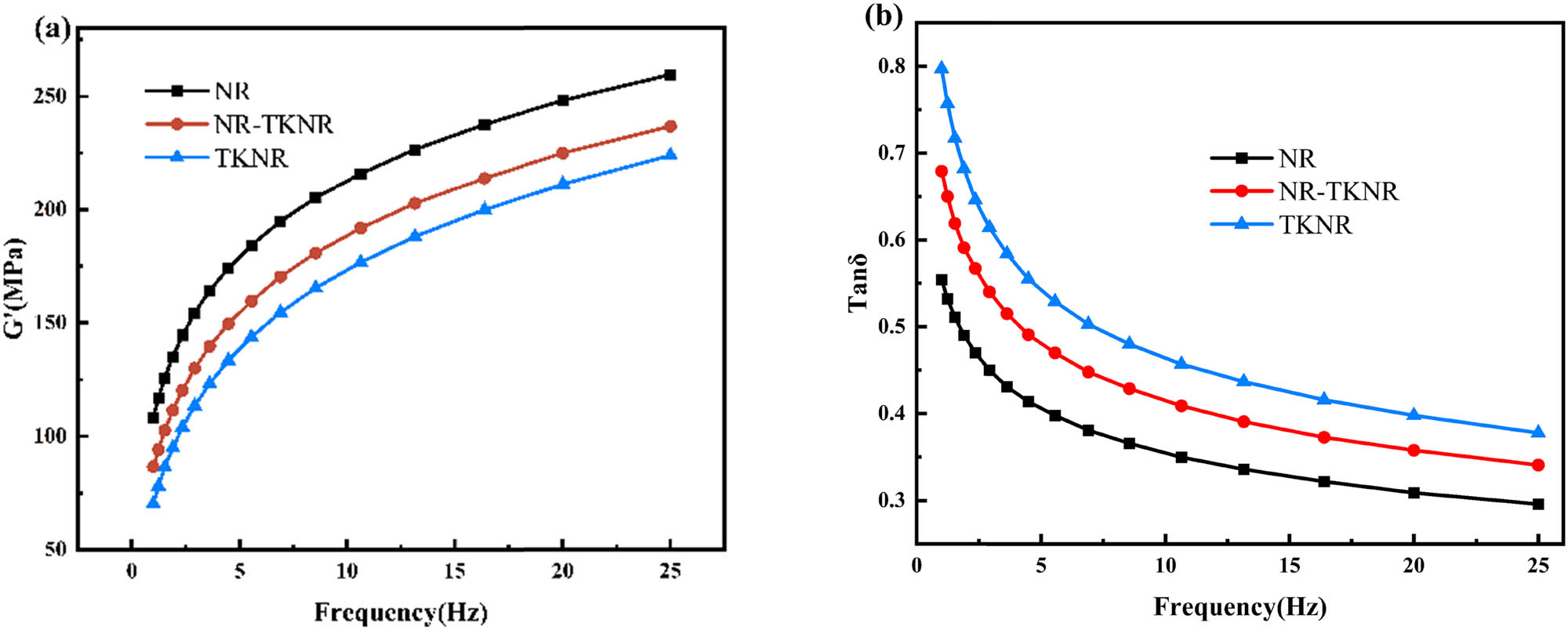

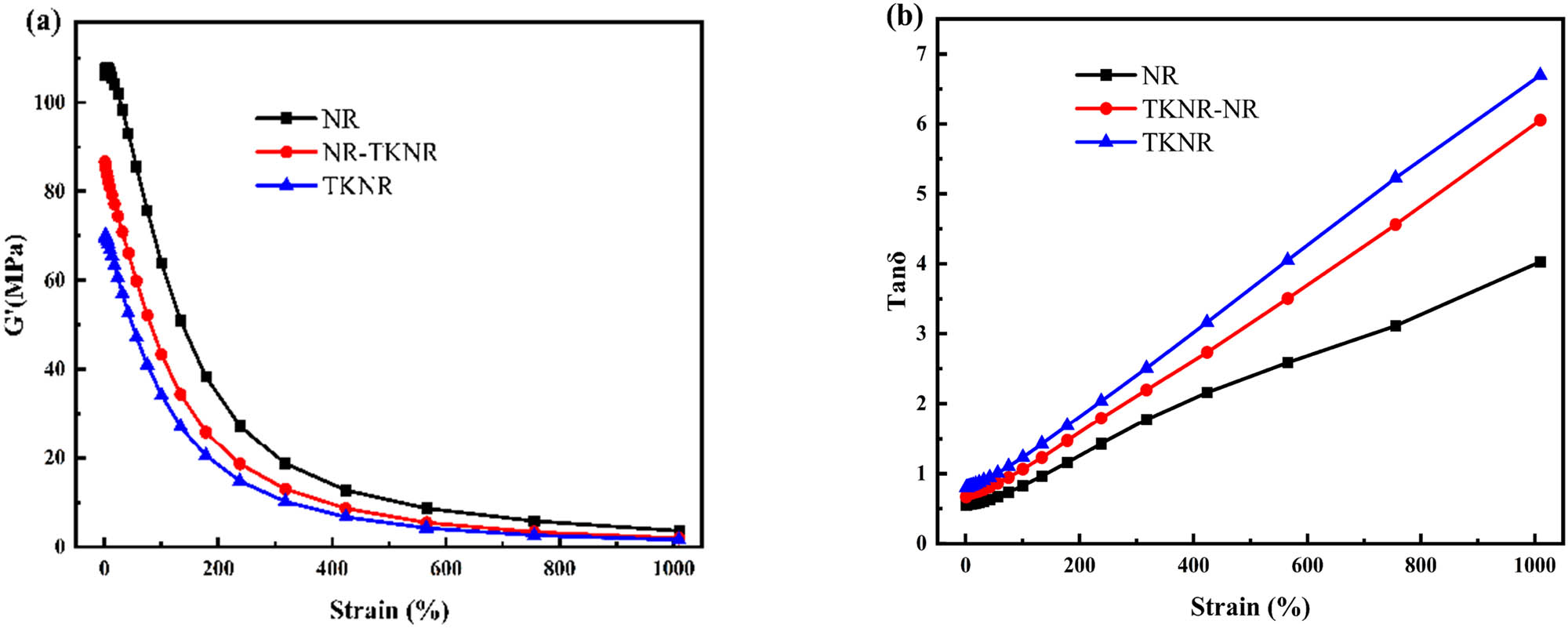

Figures 2 and 3 present the results of the frequency sweep: (a) storage modulus (G′) and (b) loss factor (Tanδ) and the strain sweep: (a) storage modulus (G′) and (b) loss factor (Tanδ), respectively, for NR, TKNR, and their blend (NR-TKNR). The differences in their rheological behavior can be attributed to variations in the crosslinking networks and molecular structures. In the frequency sweep, NR exhibited the highest and most stable G′, reflecting its strong elasticity and resistance to deformation under high frequencies. Its low Tanδ indicates minimal viscous behavior, suggesting high purity and strong chain interactions, contributing to excellent frequency responsiveness. Conversely, TKNR demonstrated a lower and more variable G′, implying a looser molecular structure, resulting in weaker elasticity and increased viscosity (higher Tanδ).

Frequency sweep results for NR, TKNR, and NR-TKNR: (a) storage modulus (G′) and (b) loss factor (Tanδ).

Strain sweep results for NR, TKNR, and NR-TKNR: (a) storage modulus (G′) and (b) loss factor (Tanδ).

In the strain sweep, NR maintained a high G′ and low Tanδ at low strains, robust elasticity and a high elastic limit, ideal for high-resilience applications. In contrast, TKNR displayed a lower G′ and higher Tanδ, highlighting more pronounced viscous characteristics and a tendency for plastic deformation under strain. As strain increased, TKNR’s G′ grew slowly, while its Tanδ rose sharply, emphasizing its low elasticity and strong viscoelastic properties. The NR-TKNR blend demonstrated intermediate behavior, with G′ and Tanδ values positioned between NR and TKNR across both frequency and strain sweeps. This indicates a balanced viscoelastic performance, suitable for applications requiring both elasticity and damping.

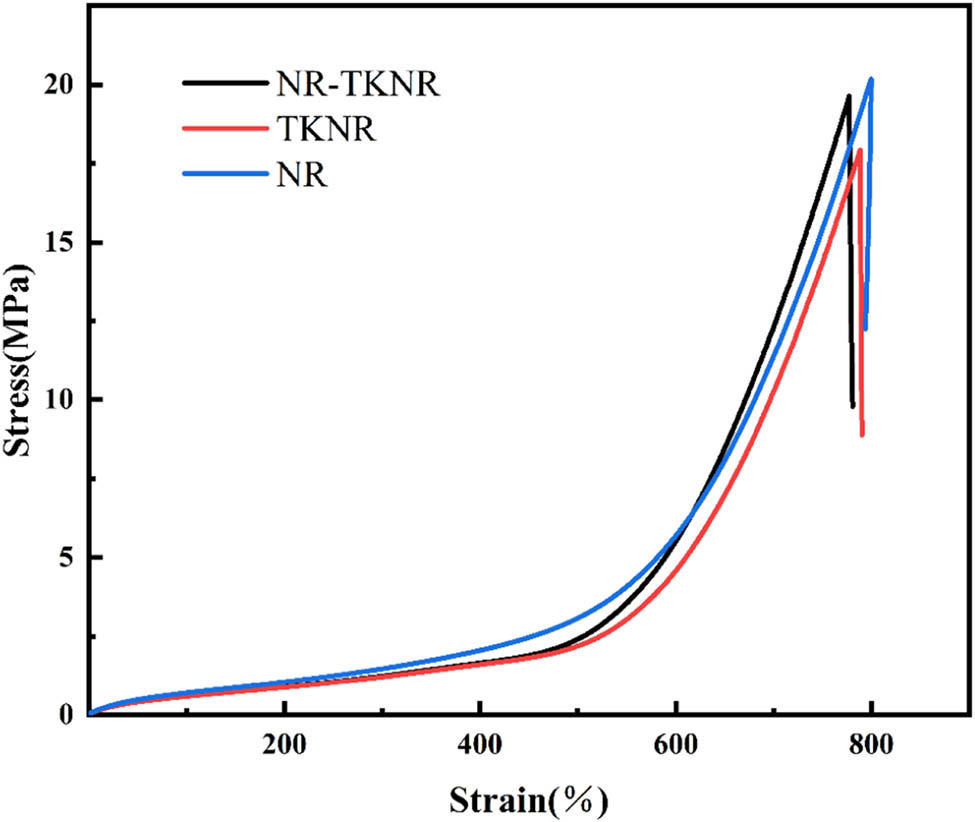

3.4 Conventional mechanical properties of vulcanizates

The stress–strain curves of the vulcanizates are shown in Figure 4, and their conventional mechanical properties are summarized in Table 3. As evident from Figure 4 and Table 3, NR exhibits higher 100% and 300% moduli as well as greater tensile strength, attributed to its more denser and more robust crosslinking network. In contrast, TKNR demonstrates lower tensile strength but higher elongation at break, which is related to its more flexible network structure and a higher density of reactive sites. These characteristics result in a faster crosslinking rate for TKNR, which limits effective network entanglement and leads to reduced tensile strength but increased elongation at break. The NR-TKNR blend exhibits moderate tensile properties and modulus values, indicating that the blending creates a balanced network structure. Additionally, TKNR shows slightly higher tear strength and slightly lower hardness compared to NR, indicating that its network can endure substantial force before tearing while maintaining greater flexibility. Meanwhile, NR displays higher hardness and comparable tear strength, confirming its stiffer and more resilient network. The NR-TKNR blend retains intermediate values for these properties, highlighting the synergistic effect of combining the rigidity of NR with the flexibility of TKNR.

Stress–strain curves of the vulcanized rubber samples.

Mechanical properties of the vulcanized rubber

| Sample | Tensile strength (MPa) | Elongation at break (%) | 100% Modulus (MPa) | 300% Modulus (MPa) | 500% Modulus (MPa) | Tear strength (kN·m−1) | Hardness (HA) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NR | 20.18 | 865 | 1.43 | 2.33 | 4.24 | 26.24 | 36 |

| TKNR | 17.92 | 900 | 0.87 | 2.01 | 4.02 | 26.52 | 34 |

| NR-TKNR | 19.63 | 843 | 1.36 | 2.17 | 5.19 | 26.47 | 35 |

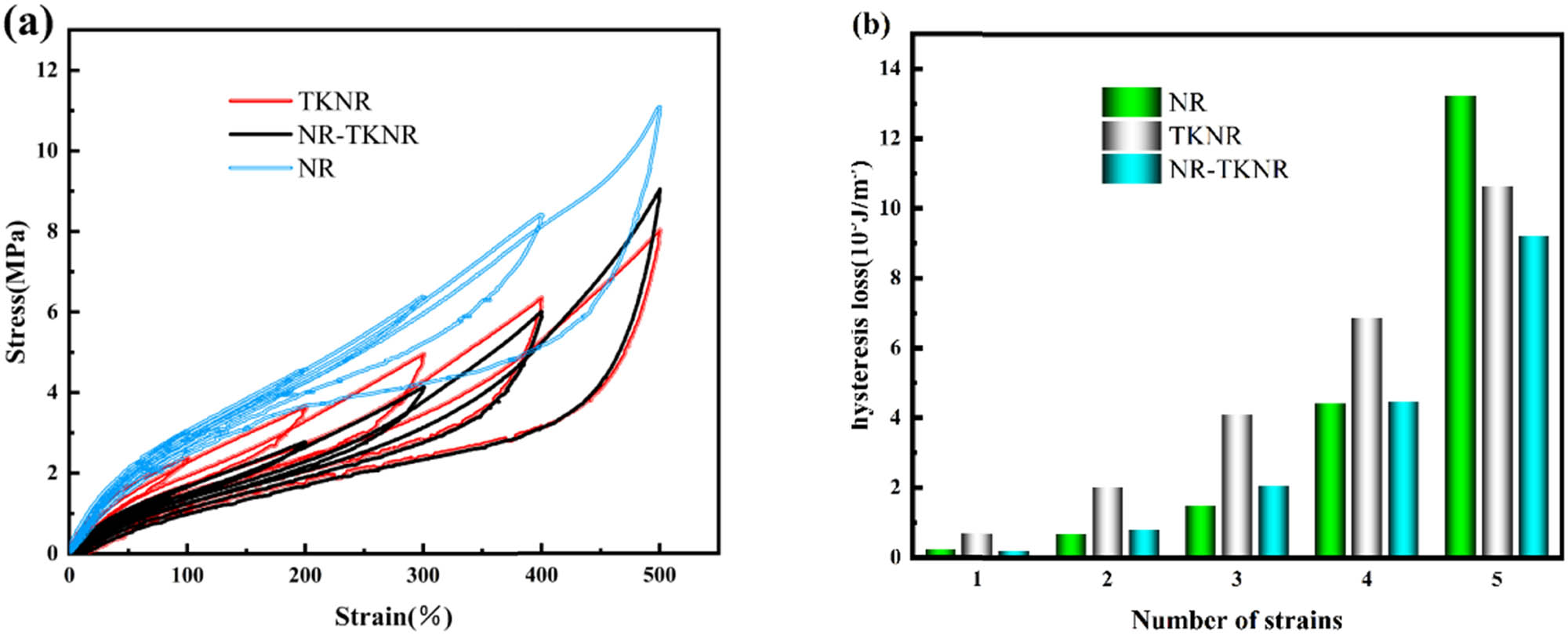

To further investigate the dynamic behavior of the materials under tensile loading, incremental strain cyclic tensile tests were performed, and the results are shown in Figure 5. NR exhibits higher stress at equivalent strain levels compared to TKNR and the TKNR-NR blend. This behavior is attributed to NR’s more robust and dense crosslinking network, as evidenced by the higher stress values in its curve, indicating greater energy storage and release during deformation cycles (27). In contrast, TKNR exhibits lower stress at comparable strain levels, indicating a more flexible crosslinking network. The TKNR-NR blend demonstrates intermediate stress–strain behavior, reflecting a balanced network structure that integrates the strengths of both NR and TKNR.

Cyclic tensile tests: (a) incremental strain cyclic tensile curves and (b) hysteresis loop areas during the incremental strain cyclic tensile process.

Figure 5a highlights the Mullins effect, characterized by a progressive reduction in tensile stress at equivalent strain levels in subsequent cycles. This phenomenon is evident as the tensile stress decreases with each successive cycle (28,29). After approximately five cycles, the stress response stabilizes, signifying stress softening. The hysteresis loss, determined by integrating the area within each tensile loop, is presented in Figure 5b. The results reveal that TKNR exhibits the highest energy loss, followed by NR-TKNR, while NR demonstrates the lowest energy dissipation. This elevated energy loss in TKNR is attributed to its denser crosslinking network and lower molecular weight between crosslinks, leading to greater energy dissipation as heat during deformation. In addition, TKNR contains a more extensive physical entanglement network, leading to higher energy dissipation during stretching. Compared to chemical networks, this structure is more fragile, as weak bonds are preferentially broken under strain. Meanwhile, molecular chains in the physical entanglement network undergo disentanglement, exhibiting a stronger “sacrificial bond” effect and resulting in greater energy dissipation. Notably, an anomaly was observed at 500% strain, where NR showed the highest energy loss. This phenomenon can be attributed to substantial damage to NR’s long-chain crosslinks under high strain, causing pronounced network disruption and increased energy dissipation.

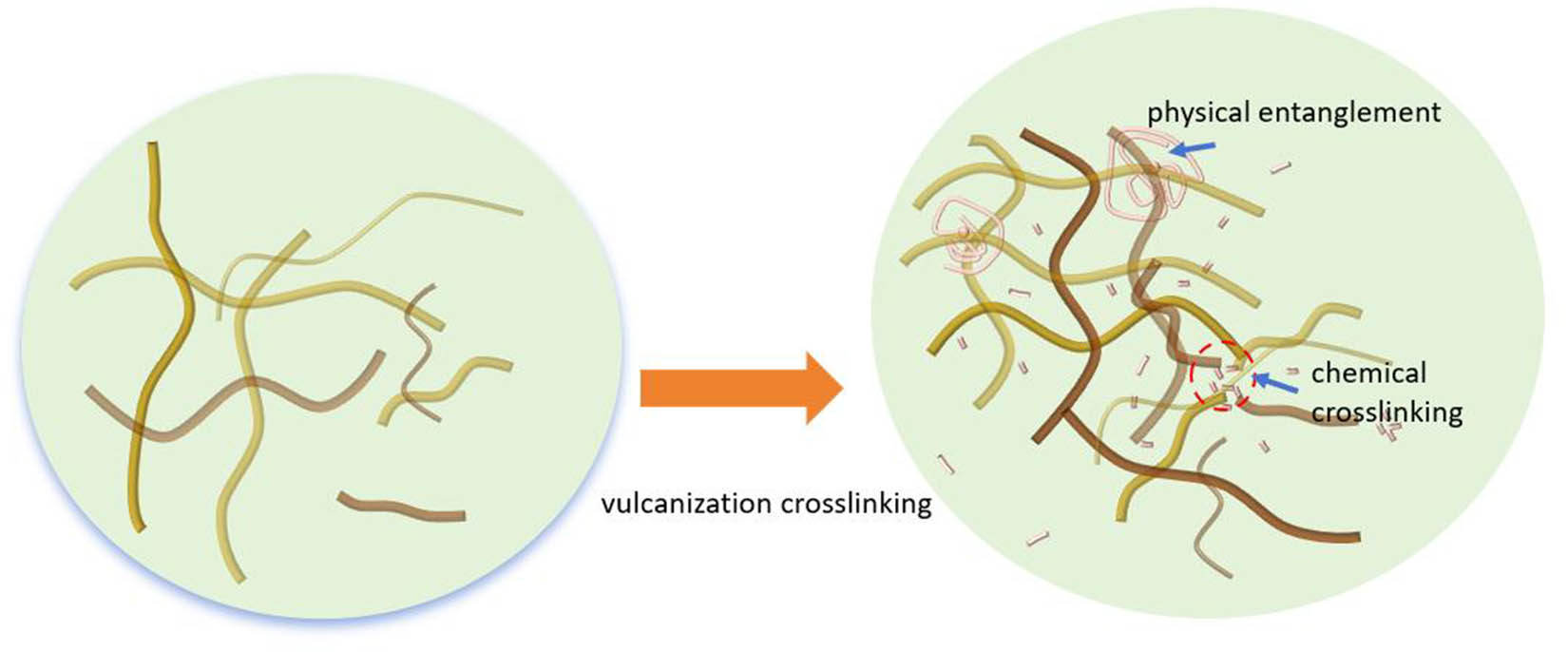

The tensile data were analyzed using the modified Mooney-Rivlin equation and the tube model, enabling the determination of key network parameters. These include the contributions of physical entanglements (G e) and chemical crosslinks (G c) (the network composition during the crosslinking process is illustrated in Figure 6), the onset strain of crystallization (α u), and structural characteristics such as effective crosslink density (υ c), molecular weight between crosslinks (M c), average number of chain segments between consecutive crosslinks (N), the fluctuation range of chain segments within the tube (d 0), and the average number of chain segments between consecutive entanglements (n e) (30–34).

Composition of the vulcanized crosslinking network.

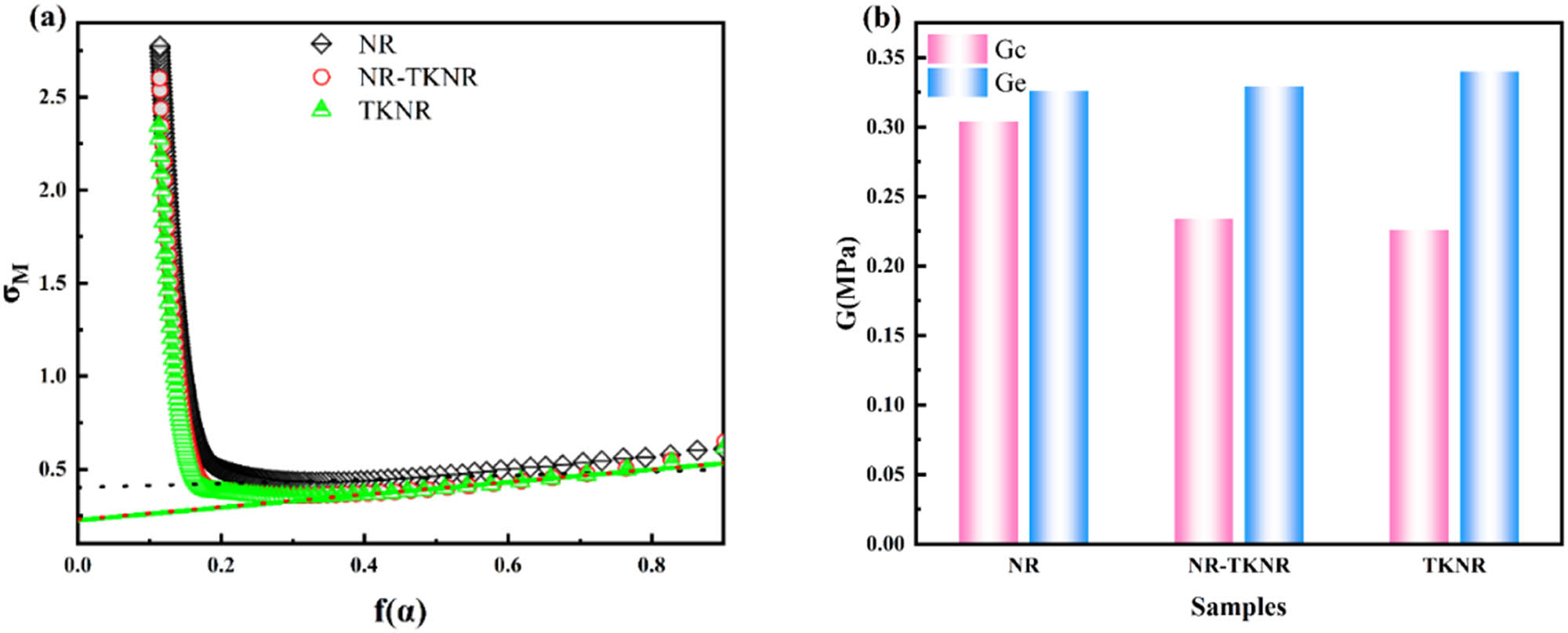

Here, β is set to 1, and L 0 and L represent the sample lengths before and after stretching, respectively. A plot of σ M against f(α) was created, and a linear fit was applied to the linear region of the curve. The intercept of the resulting line corresponds to G c, while the slope represents G e. The fitted curve is shown in Figure 7a, and the calculated values of G c and G e are presented in Figure 7b.

where α m represents the maximum extension ratio, which is used to calculate the crystallization onset strain α u.

Mooney-Rivlin equation fitting: (a) fitted curves and (b) calculated G c and G e.

Here A c is taken as 0.67, k B is the Boltzmann constant (1.380649 × 10−23 J·K−1), T is the absolute temperature (300 K), and N A is the Avogadro constant. Based on these parameters, the effective crosslink density ν c is calculated.

where ρ represents the density of rubber, taken as 0.93 g·cm−3. Based on this value, the molecular weight between cross-links M c was calculated.

where M s represents the molar mass of a single chain segment, taken as 105 g·mol−1. Based on this value, the average number of chain segments between consecutive crosslinking points N was calculated.

where n s represents the segmental spatial number density, taken as 5.46 nm−3, and l s is the average Kuhn segment length, with NR taken as 0.76 nm. Based on these values, the fluctuation range of the segments within the tube d 0 in the tube model was calculated.

Based on these values, the number of chain segments between consecutive entanglement points n e was calculated.

The calculated network parameters are summarized in Table 4, highlighting the distinct crosslinking characteristics of NR, NR-TKNR blends, and TKNR. NR exhibits a higher degree of chemical crosslinking, contributing to its superior strength, whereas TKNR displays greater physical crosslinking, enhancing its flexibility. These observations align well with the stress–strain test results. The NR-TKNR blend demonstrates intermediate values, reflecting a balance between the chemical crosslinking of NR and the physical crosslinking of TKNR. Notably, the crystallization onset strain (α u) in NR-TKNR is higher than that of both NR and TKNR, indicating a more robust network structure capable of delaying crystallization and potentially improving mechanical performance.

Network structure parameters of vulcanized rubber

| Sample | G c (MPa) | G e (MPa) | α u | v (mol·m−3) | M c (g·mol−1) | N | d 0 (nm) | n e |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NR | 0.304 | 0.326 | 4.38 | 97.33 | 9,452 | 90 | 1.93 | 6.43 |

| NR-TKNR | 0.234 | 0.329 | 5.08 | 124.77 | 7,373 | 70 | 1.92 | 6.37 |

| TKNR | 0.226 | 0.340 | 4.39 | 175.07 | 5,255 | 50 | 1.89 | 6.17 |

The average number of chain segments between consecutive crosslinks (N), the segmental fluctuation range within the tube (d 0), and the number of segments between entanglement points (ne) in TKNR are slightly lower than those in NR, indicating that the crosslinked network structure of TKNR is marginally less stable than that of NR. This observation aligns with the energy loss patterns observed in the cyclic tensile tests. These network parameters correlate well with the mechanical properties of the rubbers, emphasizing NR’s higher stiffness and strength, TKNR’s greater flexibility and elongation, and the NR-TKNR blend’s balanced combination of these attributes.

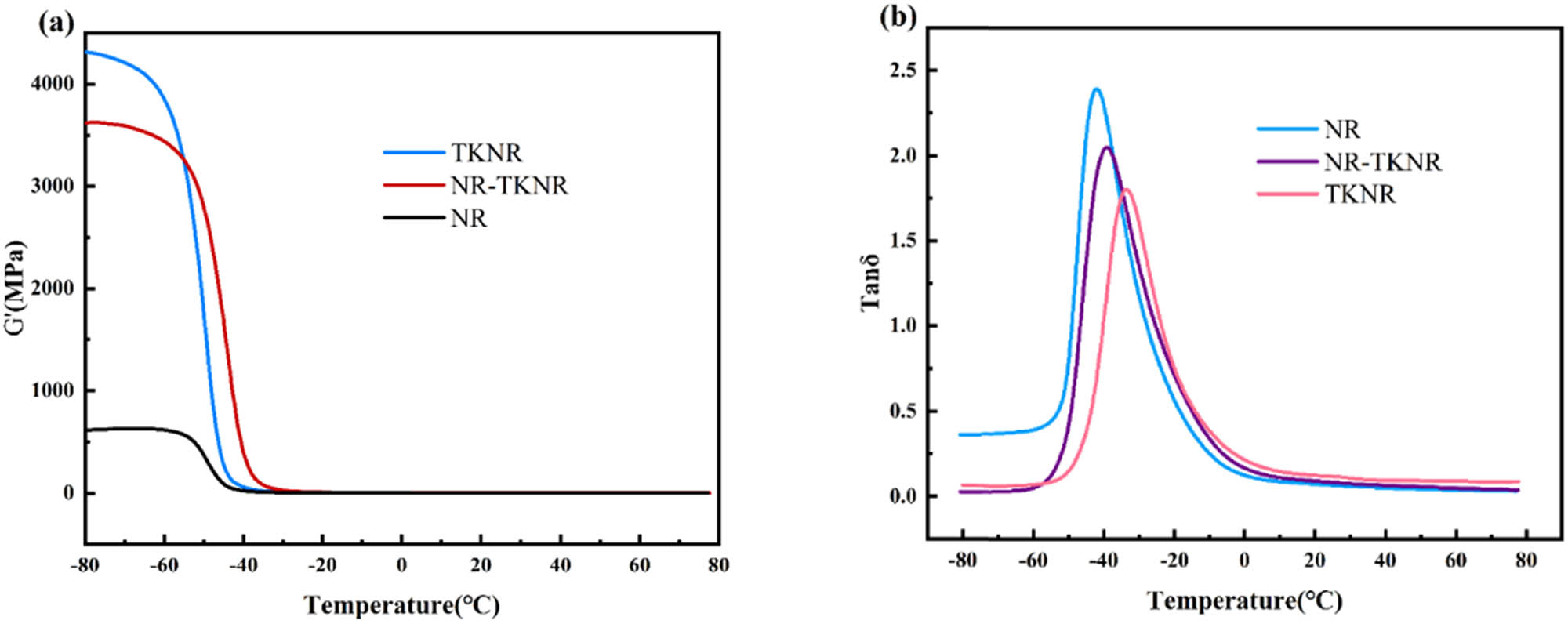

3.5 DMA of vulcanized rubber

The DMA of the vulcanized rubbers are shown in Figure 8. As shown in Figure 8a, the storage modulus (G′) of NR, NR-TKNR, and TKNR exhibits distinct trends with temperature variation. NR demonstrates the lowest G′, TKNR shows the highest, and NR-TKNR lies between the two. These differences reflect the variations in elastic energy storage capacity among the rubber samples under changing temperature conditions (35). The relatively low G′ of NR indicates weaker elasticity across a broad temperature range, which can be attributed to the comparable contributions from both its physical entanglements (G e) and chemical crosslinks (G c). Consequently, G′ remains low throughout the temperature variation. In contrast, TKNR, with a greater contribution from physical entanglements (G e) and a smaller contribution from chemical crosslinks (G c), exhibits a higher initial G′ and a more pronounced temperature-dependent change. The NR-TKNR blend shows intermediate properties, combining NR’s flexibility with TKNR’s higher elasticity.

DMA curves of vulcanized rubber: (a) storage modulus curves and (b) loss factor curves.

Figure 8b illustrates that NR has the highest loss factor (Tanδ) peak, TKNR the lowest, and NR-TKNR lies in between. The Tanδ value reflects the internal friction and energy dissipation of the material. The high Tanδ peak in NR indicates greater internal friction and higher energy loss, which correlates with its lower crosslink density (v) and higher molecular weight between crosslinks (M c). TKNR, exhibiting a higher crosslink density (v) and lower M c, demonstrates less internal friction and energy loss, resulting in the lowest Tanδ peak. The NR-TKNR blend again shows intermediate values, reflecting moderate internal friction and energy loss.

Alongside the crosslinking network analysis, the fluctuation range of chain segments within the tube and the average number of chain segments between consecutive entanglement points in NR-TKNR are also intermediate, between those of NR and TKNR. These results underscore the significant influence of the crosslinking network structure on the dynamic mechanical properties of rubber materials: higher crosslink density leads to lower internal friction and energy loss.

4 Conclusion

This study systematically evaluated the crosslinking network and mechanical properties of TKNR using vulcanization characterization, equilibrium swelling tests, rheological analysis, mechanical performance testing, DMA, and simulations based on the Mooney-Rivlin and tube models. The findings revealed the distinctive relationship between TKNR’s crosslinking network structure and its performance.

During vulcanization, the higher number of functional groups and reactive sites in TKNR facilitated a faster vulcanization process, resulting in the formation of a denser yet shorter crosslinking network. This structural characteristic yielded a higher crosslink density (v) and lower molecular weight between crosslinks (M c) in TKNR compared to conventional NR. Consequently, TKNR exhibited superior elongation at break and tear strength, albeit with slightly lower tensile strength and hardness. However, during cyclic tensile testing, the denser network led to greater chain scission and higher energy dissipation. DMA further demonstrated that, as temperature increased, TKNR displayed an enhanced storage modulus (G′) and a reduced loss factor peak (Tanδ), indicating excellent elastic energy storage capacity and minimized internal friction losses. The results of the Mooney-Rivlin and tube model simulations provided deeper insights into the relationship between TKNR’s network and performance. TKNR’s crosslinking network featured a higher level of physical entanglement (G e) and relatively lower chemical crosslink density (G c), which collectively contributed to its superior toughness and outstanding elastic energy storage capability.

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by the Hainan Province Science and Technology Special Fund (ZDYF2022XDNY209), Central Public-interest Scientific Institution Basal Research Fund (1630122022006), Hainan Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (521RC1039), National Key R&D Program of China (2022YFD23012053-4), the earmarked fund for Tropical High-efficiency Agricultural Industry Technology System of Hainan University (THAITS-3), and the Key Laboratory of Natural Rubber Processing of Hainan Province (No. HNXJ2024601).

-

Author contributions: Jiagang Zheng: conceptualization, investigation, data curation, methodology, formal analysis, visualization, and writing – original draft. Xiaokang Wei: formal analysis. Yanfang Zhao: investigation, formal analysis. Xuechao Zhang: investigation, data curation. Qingyun Zhao: formal analysis. Xiaoxue Liao: writing – review & editing, supervision, project administration, and funding acquisition. Rentong Yu: writing – review & editing. Haozhi Wang: formal analysis.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this article.

-

Data availability statement: Data will be made available on request.

References

(1) Soratana K, Rasutis D, Azarabadi H, Eranki PL, Landis AE. Guayule as an alternative source of natural rubber: a comparative life cycle assessment with Hevea and synthetic rubber. J Clean Prod. 2017;159:271–80. 10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.05.070.Search in Google Scholar

(2) Hodgson-Kratky KJM, Stoffyn OM, Wolyn DJ. Recurrent selection for rubber yield in Russian Taraxacum kok-saghyz. J Am Soc Hortic Sci. 2017;142(6):470–5. 10.21273/JASHS04252-17.Search in Google Scholar

(3) Piccolella S, Sirignano C, Pacifico S, Fantini E, Daddiego L, Facella P, et al. Beyond natural rubber: Taraxacum kok-saghyz and Taraxacum brevicorniculatum as sources of bioactive compounds. Ind Crop Prod. 2023;195:116446. 10.1016/j.indcrop.2023.116446.Search in Google Scholar

(4) Olsen KM, Li LF. Rooting for new sources of natural rubber. Nat Sci Rev. 2018;5(1):89. 10.1093/nsr/nwx101c.Search in Google Scholar

(5) Puskas JE, Cornish K, Kenzhe-Karim B, Mutalkhanov M, Kaszas G, Molnar K. Natural rubber - increasing diversity of an irreplaceable renewable resource. Heliyon. 2024;10(3):e25123.10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e25123.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

(6) Zwart H, Krabbenborg L, Zwier J. Is Taraxacum kok-saghyz rubber more natural? Naturalness, biotechnology and the transition towards a bio-based society. J Agric Environ Ethics. 2015;28(2):313–34. 10.1007/s10806-015-9536-0.Search in Google Scholar

(7) Sikandar S, Ujor VC, Ezeji TC, Rossington JL, Michel FC, McMahan CM, et al. STm: a source of thermostable hydrolytic enzymes for novel application in extraction of high-quality natural rubber from -Rubber Taraxacum kok-saghyz. Ind Crop Prod. 2017;103:161–8.10.1016/j.indcrop.2017.03.044.Search in Google Scholar

(8) Ramirez Cadavid DA, Hathwaik U, Cornish K, McMahan C, Michel FC. Alkaline pretreatment of Taraxacum kok-saghyz (TK) roots for the extraction of natural rubber (NR). Biochem Eng J 2022;181:108376. 10.1016/j.bej.2022.108376.Search in Google Scholar

(9) He SM, Zhang FQ, Liu S, Cui HP, Chen S, Peng WF, et al. Influence of sizes of rubber particles in latex on mechanical properties of natural rubber filled with carbon black. Polymer. 2022;261:125393.10.1016/j.polymer.2022.125393.Search in Google Scholar

(10) Wei YC, Liu GX, Zhang HF, Zhao FC, Luo MC, Liao SQ. Non-rubber components tuning mechanical properties of natural rubber from vulcanization kinetics. Polymer. 2019;183:121911. 10.1016/j.polymer.2019.121911.Search in Google Scholar

(11) Raa Khimi SR, Pickering KL. The effect of silane coupling agent on the dynamic mechanical properties of iron sand/natural rubber magnetorheological elastomers. Compos Part B Eng. 2016;90:115–25. 10.1016/j.compositesb.2015.11.042.Search in Google Scholar

(12) Yamano M, Yamamoto Y, Saito T, Kawahara S. Preparation and characterization of vulcanized natural rubber with high stereoregularity. Polymer. 2021;235:124271.10.1016/j.polymer.2021.124271.Search in Google Scholar

(13) Nardelli F, Calucci L, Carignani E, Borsacchi S, Cettolin M, Arimondi M, et al. Influence of sulfur-curing conditions on the dynamics and crosslinking of rubber networks: a time-domain NMR study. Polymers. 2022;14(4):767.10.3390/polym14040767.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

(14) Candau N, Vives E, Fernández AI, Maspoch ML. Elastocaloric effect in vulcanized natural rubber and natural/wastes rubber blends. Polymer. 2021;236:124309.10.1016/j.polymer.2021.124309.Search in Google Scholar

(15) Zhou Y, Kosugi K, Yamamoto Y, Kawahara S. Effect of non-rubber components on the mechanical properties of natural rubber. Polym Adv Technol. 2017;28(2):159–65. 10.1002/pat.3870.Search in Google Scholar

(16) Li ZX, Kong YR, Chen XF, Huang YJ, Lv YD, Li GX. High-temperature thermo-oxidative aging of vulcanized natural rubber nanocomposites: evolution of microstructure and mechanical properties. Chin J Polym Sci. 2023;41(8):1287–97.10.1007/s10118-023-2948-9.Search in Google Scholar

(17) Ahsan Q, Mohamad N, Soh TC. Effects of accelerators on the cure characteristics and mechanical properties of natural rubber compounds. Int J Automot Mech Eng. 2015;12:2954–66. 10.15282/ijame.12.2015.12.0247.Search in Google Scholar

(18) Hosseini SM, Razzaghi-Kashani M. Catalytic and networking effects of carbon black on the kinetics and conversion of sulfur vulcanization in styrene-butadiene rubber. Soft Matter. 2018;14(45):9194–208. 10.1039/C8SM01953C.Search in Google Scholar

(19) Junkong P, Cornish K, Ikeda Y. Characteristics of mechanical properties of sulphur cross-linked guayule and Taraxacum kok-saghyz natural rubbers. RSC Adv. 2017;7(80):50739–52.10.1039/C7RA08554K.Search in Google Scholar

(20) Ikeda Y, Cornish K, Phakkeeree T, Matsushima Y, Junkong P. Influence of strain-induced crystallization on stress softening of sulfur cross-linked unfilled guayule and Taraxacum kok-saghyz natural rubbers. Rubber Chem Technol. 2019;92(2):388–98. 10.5254/rct.19.81481.Search in Google Scholar

(21) Nun-anan P, Wisunthorn S, Pichaiyut S, Vennemann N, Kummerlöwe C, Nakason C. Influence of alkaline treatment and acetone extraction of natural rubber matrix on properties of carbon black filled natural rubber vulcanizates. Polym Test. 2020;89:106623. 10.1016/j.polymertesting.2020.106623.Search in Google Scholar

(22) Sriring M, Nimpaiboon A, Kumarn S, Sirisinha C, Sakdapipanich J, Toki S. Viscoelastic and mechanical properties of large- and small-particle natural rubber before and after vulcanization. Polym Test. 2018;70:127–34.10.1016/j.polymertesting.2018.06.026.Search in Google Scholar

(23) Kim DY, Park JW, Lee DY, Seo KH. Correlation between the crosslink characteristics and mechanical properties of natural rubber compound via accelerators and reinforcement. Polymers. 2020;12(9):2020. 10.3390/polym12092020.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

(24) Chaikumpollert O, Yamamoto Y, Suchiva K, Kawahara S. Mechanical properties and cross-linking structure of cross-linked natural rubber. Polym J 2012;44(8):772–7. 10.1038/pj.2012.112.Search in Google Scholar

(25) Wang M, Wang R, Chen X, Kong Y, Huang Y, Lv Y, et al. Effect of non-rubber components on the crosslinking structure and thermo-oxidative degradation of natural rubber. Polym Degrad Stab 2022;196:109845. 10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2022.109845.Search in Google Scholar

(26) Wang Y, Su S, Liu H, Wang R, Liao L, Peng Z, et al. Effect of proteins on the vulcanized natural rubber crosslinking network structure and mechanical properties. Polymers. 2024;16(21):2957. 10.3390/polym16212957.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

(27) Zhang FZ, Chen YL, Sun CZ, Wen SP, Liu L. Network evolutions in both pure and silica-filled natural rubbers during cyclic shear loading. RSC Adv. 2014;4(51):26706–13. 10.1039/C4RA02003K.Search in Google Scholar

(28) Göktepe S, Miehe C. A micro-macro approach to rubber-like materials. Part III: the micro-sphere model of anisotropic Mullins-type damage. J Mech Phys Solids. 2005;53(10):2259–83. 10.1016/j.jmps.2005.04.010.Search in Google Scholar

(29) Song YH, Yang RQ, Du M, Shi XY, Zheng Q. Rigid nanoparticles promote the softening of rubber phase in filled vulcanizates. Polymer. 2019;177:131–8. 10.1016/j.polymer.2019.06.003.Search in Google Scholar

(30) López-Manchado MA, Valentín JL, Carretero J, Barroso F, Arroyo M. Rubber network in elastomer nanocomposites. Eur Polym J 2007;43(10):4143–50. 10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2007.07.023.Search in Google Scholar

(31) Li K, Li Z, Liu J, Wen S, Liu L, Zhang L. Designing the cross-linked network to tailor the mechanical fracture of elastomeric polymer materials. Polymer. 2022;252:124931. 10.1016/j.polymer.2022.124931.Search in Google Scholar

(32) Nie YJ, Wang BY, Huang GS, Qu LL, Zhang P, Weng GS, et al. Relationship between the material properties and fatigue crack-growth characteristics of natural rubber filled with different carbon blacks. J Appl Polym Sci. 2010;117(6):3441–7. 10.1002/app.32098.Search in Google Scholar

(33) Drozdov AD, deClaville Christiansen J. Thermo-mechanical behavior of elastomers with dynamic covalent bonds. Int J Eng Sci. 2020;147:103200. 10.1016/j.ijengsci.2019.103200.Search in Google Scholar

(34) Chen GJ, Wang BB, Lin HT, Peng WF, Zhang FQ, Li GR, et al. Effect of nonisoprene degradation and naturally occurring network during maturation on the properties of natural rubber. Polymers. 2022;14(11):2180. 10.3390/polym14112180.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

(35) Baruel AF, de Mello SAC, Menezes F, Cassu SN. Effect of vulcanization system on damping properties of natural rubber. Macromol Symp. 2022;406(1):2200040. 10.1002/masy.202200040.Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Flow-induced fiber orientation in gas-powered projectile-assisted injection molded parts

- Research on thermal aging characteristics of silicone rubber composite materials for dry-type distribution transformers

- Kinetics of acryloyloxyethyl trimethyl ammonium chloride polymerization in aqueous solutions

- Influence of siloxane content on the material performance and functional properties of polydimethylsiloxane copolymers containing naphthalene moieties

- Enhancement effect of electron beam irradiation on acrylonitrile–butadiene–styrene (ABS) copolymers from waste electrical and electronic equipment by adding 1,3-PBO: A potential way for waste ABS reuse

- Model construction and property study of poly(ether-ether-ketone) by molecular dynamics simulation with meta-modeling methods

- Zinc–gallic acid–polylysine nanocomplexes with enhanced bactericidal activity for the treatment of bacterial keratitis

- Effect of pyrogallol compounds dosage on mechanical properties of epoxy coating

- Preparation of in situ polymerized polypyrrole-modified braided cord and its electrical conductivity investigation under varied mechanical conditions

- Hydrophobicity, UV resistance, and antioxidant properties of carnauba wax-reinforced CG bio-polymer film

- Janus nanofiber membrane films loading with bioactive calcium silicate for the promotion of burn wound healing

- Synthesis of migration-resistant antioxidant and its application in natural rubber composites

- Influence of the flow rate on the die swell for polymer micro coextrusion process

- Fatty acid filled polyaniline nanofibres with dual electrical conductivity and thermo-regulatory characteristics: Futuristic material for thermal energy storage

- Hydrolytic depolymerization of major fibrous wastes

- Performance of epoxy hexagonal boron nitrate underfill materials: Single and mixed systems

- Blend electrospinning of citronella or thyme oil-loaded polyurethane nanofibers and evaluating their release behaviors

- Efficiency of flexible shielding materials against gamma rays: Silicon rubber with different sizes of Bi2O3 and SnO

- A comprehensive approach for the production of carbon fibre-reinforced polylactic acid filaments with enhanced wear and mechanical behaviour

- Electret melt-blown nonwovens with charge stability for high-performance PM0.3 purification under extreme environmental conditions

- Study on the failure mechanism of suture CFRP T-joints under/after the low-velocity impact loading

- Experimental testing and finite element analysis of polyurethane adhesive joints under Mode I loading and degradation conditions

- Optimizing recycled PET 3D printing using Taguchi method for improved mechanical properties and dimensional precision

- Effect of stacking sequence of the hybrid composite armor on ballistic performance and damage mechanism

- Bending crack propagation and delamination damage behavior of orthogonal ply laminates under positive and negative loads

- Molecular dynamics simulation of thermodynamic properties of Al2O3-modified silicone rubber under silane coupling agent modification

- Precision injection molding method based on V/P switchover point optimization and pressure field balancing

- Heparin and zwitterion functionalized small-diameter vascular grafts for thrombogenesis prevention

- Metal-free N, S-co-doped carbon materials derived from calcined aromatic co-poly(urea-thiourea)s as efficient alkaline oxygen reduction catalysts

- Influence of stitching parameters on the tensile performance and failure mechanisms of CFRP T-joints

- Synthesis of PEGylated polypeptides bearing thioether pendants for injectable ROS-responsive hydrogels

- A radiation-resistant MWCNT/Nafion/MWCNT composite film for humidity perception

- Study on the crosslinking network and mechanical properties of Taraxacum kok-saghyz natural rubber

- Preparation of maleic anhydride-modified curcumin/PBAT composite film for food packaging

- Rapid Communication

- RAFT-mediated polymerization-induced self-assembly of poly(ionic liquid) block copolymers in a green solvent

- Corrigendum

- Corrigendum to “High-strength polyvinyl alcohol-based hydrogel by vermiculite and lignocellulosic nanofibrils for electronic sensing”

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Flow-induced fiber orientation in gas-powered projectile-assisted injection molded parts

- Research on thermal aging characteristics of silicone rubber composite materials for dry-type distribution transformers

- Kinetics of acryloyloxyethyl trimethyl ammonium chloride polymerization in aqueous solutions

- Influence of siloxane content on the material performance and functional properties of polydimethylsiloxane copolymers containing naphthalene moieties

- Enhancement effect of electron beam irradiation on acrylonitrile–butadiene–styrene (ABS) copolymers from waste electrical and electronic equipment by adding 1,3-PBO: A potential way for waste ABS reuse

- Model construction and property study of poly(ether-ether-ketone) by molecular dynamics simulation with meta-modeling methods

- Zinc–gallic acid–polylysine nanocomplexes with enhanced bactericidal activity for the treatment of bacterial keratitis

- Effect of pyrogallol compounds dosage on mechanical properties of epoxy coating

- Preparation of in situ polymerized polypyrrole-modified braided cord and its electrical conductivity investigation under varied mechanical conditions

- Hydrophobicity, UV resistance, and antioxidant properties of carnauba wax-reinforced CG bio-polymer film

- Janus nanofiber membrane films loading with bioactive calcium silicate for the promotion of burn wound healing

- Synthesis of migration-resistant antioxidant and its application in natural rubber composites

- Influence of the flow rate on the die swell for polymer micro coextrusion process

- Fatty acid filled polyaniline nanofibres with dual electrical conductivity and thermo-regulatory characteristics: Futuristic material for thermal energy storage

- Hydrolytic depolymerization of major fibrous wastes

- Performance of epoxy hexagonal boron nitrate underfill materials: Single and mixed systems

- Blend electrospinning of citronella or thyme oil-loaded polyurethane nanofibers and evaluating their release behaviors

- Efficiency of flexible shielding materials against gamma rays: Silicon rubber with different sizes of Bi2O3 and SnO

- A comprehensive approach for the production of carbon fibre-reinforced polylactic acid filaments with enhanced wear and mechanical behaviour

- Electret melt-blown nonwovens with charge stability for high-performance PM0.3 purification under extreme environmental conditions

- Study on the failure mechanism of suture CFRP T-joints under/after the low-velocity impact loading

- Experimental testing and finite element analysis of polyurethane adhesive joints under Mode I loading and degradation conditions

- Optimizing recycled PET 3D printing using Taguchi method for improved mechanical properties and dimensional precision

- Effect of stacking sequence of the hybrid composite armor on ballistic performance and damage mechanism

- Bending crack propagation and delamination damage behavior of orthogonal ply laminates under positive and negative loads

- Molecular dynamics simulation of thermodynamic properties of Al2O3-modified silicone rubber under silane coupling agent modification

- Precision injection molding method based on V/P switchover point optimization and pressure field balancing

- Heparin and zwitterion functionalized small-diameter vascular grafts for thrombogenesis prevention

- Metal-free N, S-co-doped carbon materials derived from calcined aromatic co-poly(urea-thiourea)s as efficient alkaline oxygen reduction catalysts

- Influence of stitching parameters on the tensile performance and failure mechanisms of CFRP T-joints

- Synthesis of PEGylated polypeptides bearing thioether pendants for injectable ROS-responsive hydrogels

- A radiation-resistant MWCNT/Nafion/MWCNT composite film for humidity perception

- Study on the crosslinking network and mechanical properties of Taraxacum kok-saghyz natural rubber

- Preparation of maleic anhydride-modified curcumin/PBAT composite film for food packaging

- Rapid Communication

- RAFT-mediated polymerization-induced self-assembly of poly(ionic liquid) block copolymers in a green solvent

- Corrigendum

- Corrigendum to “High-strength polyvinyl alcohol-based hydrogel by vermiculite and lignocellulosic nanofibrils for electronic sensing”