The crystal structure of poly(bis(μ2-1,3,5-tri(1H-imidazol-1-yl)benzene-κ2N:N′)-(μ2-2,3,5,6-tetrafluoroterephthalato-κ2O:O′)-manganese(II), C38H24F4N12O4Mn

-

Zhongde Wei

Abstract

C38H24F4N12O4Mn, triclinic,

Table 1 contains the crystallographic data and the list of the atoms including atomic coordinates and displacement parameters can be found in the cif-file attached to this article.

Data collection and handling.

| Crystal: | Colorless block |

| Size: | 0.30 × 0.25 × 0.15 mm |

| Wavelength: | Mo Kα radiation (0.71073 Å) |

| μ: | 0.48 mm−1 |

| Diffractometer, scan mode: | Rigaku XtaLAB Mini (ROW), ω scans |

| θmax, completeness: | 25.1°, 100 % |

| N(hkl)measured, N(hkl)unique, Rint: | 4491, 2955, 0.017 |

| Criterion for Iobs, N(hkl)gt: | Iobs > 2 σ(Iobs), 2,631 |

| N(param)refined: | 268 |

| Programs: | Rigaku, 1 Olex2, 2 SHELX 3 , 4 |

1 Source of materials

All chemicals were purchased from commercial sources and used as received. A mixture of Mn(NO3)2 (1.0 mL 0.10 mol L−1 Mn(NO3)2 solution, 0.10 mmol), 2,3,5,6-tetrafluoroterephthalic acid (2,3,5,6-tetrafluoroterephthalic acid is abbreviated as H2TFA) (0.0238 g, 0.10 mmol), 1,3,5-tri(1H-imidazol-1-yl)benzene (1,3,5-tri(1H-imidazol-1-yl)benzene is abbreviated as TIB) (0.0276 g, 0.1 mmol), NaOH (1.0 mL 0.1 mol L−1 NaOH solution, 0.1 mmol), and H2O/anhydrous ethanol (6.0 mL/3.0 mL) was added to a 25 mL Teflon-lined stainless steel reactor and heated at 393 K for 3 days. After cooling to room temperature at a rate of 283 K h−1, colorless block-shaped crystals of I were collected by filtration, washed with anhydrous ethanol and dried in air. Phase pure crystals were obtained by manual separation (yield: 50.62 mg, ca. 60 % based on 4-fluorobenzoic acid). Anal. Calc. for I: C38H24F4N12O4Mn (%) (Mr = 843.63): C, 54.05; H, 2.84; N, 19.91. Found: C, 54.06; H, 2.82; N, 19.93.

2 Experimental details

CrysAlisPro 1.171.39.46 (Rigaku Oxford Diffraction, 2018) empirical absorption correction using spherical harmonics, implemented in SCALE3 ABSPACK scaling algorithm. 1 Using Olex2, 2 the structure was solved with the ShelXT 3 structure solution program and refined with the ShelXL 4 refinement package. Carbon-bound hydrogen atoms were placed in calculated positions (d = 0.93 Å for CH and were included in the refinement in the riding model approximation, with Uiso(H) set to 1.2Ueq(C) for –CH). The structure was examined using the ADDSYM subroutine of PLATON 5 to ensure that no additional symmetry could be applied to the models.

3 Comment

The ceramics are bulk materials formed by sintering randomly oriented inorganic non-metallic crystallites. They are typically opaque due to defects, pores, and intrinsic material birefringence. 6 The optical ceramics, a specialized class of transparent ceramics, eliminate light scattering and combine the advantages of other transparent bulk materials, such as single crystals and glass. 7 They are suitable for high-performance optical windows and laser gain media. However, the optical ceramics impose stringent requirements on raw materials or precursors: (1) high-purity, size-uniform nanocrystallites are essential to eliminate defects and pores; (2) crystallization in the cubic system is mandatory to suppress birefringence. 8 Additionally, organic and inorganic-organic hybrid materials cannot withstand the high-temperature sintering required for ceramic preparation. 9 Consequently, only a limited number of materials are currently viable for optical ceramics. Coordination polymers, some of them also termed metal-organic frameworks (MOFs), represent a class of crystalline materials with diverse structures and functionalities. 10 While MOF thin films and single crystals show promise for separation, sensing, and optical devices, producing high-quality large-sized samples remains challenging. 11

The optical ceramics are a type of transparent specialty ceramics that combine the high stability of single crystals with the large-scale advantages of glass, fluids, and other amorphous materials, making them promising laser gain media. 12 Due to the strict requirements for crystal size and symmetry, coupled with the need for high-temperature sintering processes, only a limited number of inorganic non-metallic materials can be used to produce optical ceramics. 13 Considering the structural and functional diversity of metal-organic frameworks (MOFs), metal-organic ceramics hold potential not only for optical devices but also in related fields such as adsorption, separation, and sensing. 14 , 15 Recently, the Henke research group at TU Dortmund University in Germany achieved the first melting-glassification-ceramic transformation of a cadmium(II)-based MOF glass. 16 Using mechanochemical synthesis, they produced submicron Cd(im)2 particles with high-density surface defects, successfully lowering the melting point to 455°. This avoided the decomposition window, enabling stable melting and rapid quenching into glass. The study also revealed that under controlled heating conditions, the material could partially recrystallize, transforming into a monolithic glass-ceramic with nanocrystals uniformly embedded in a glass matrix. This structure exhibits enhanced mechanical properties and reversible thermal response characteristics. This research not only uncovers the distinctive thermodynamic phase transition behaviors of d-block transition metal MOF materials but also opens up new pathways for designing and functionally tailoring MOF glass-ceramics.

On the other hand, both 1,3,5-tris(1-imidazolyl)benzene (TIB) 17 and tetrafluoroterephthalate (H2TFA) 18 are rigid organic building blocks with triangular and linear geometries, respectively, which have been proved as versatile linkers to connect metal ions into higher dimensional structures through various coordination modes as well as secondary interactions such as hydrogen bond and halogen bond. 19 , 20 , 21 Although a search in the CSD (Cambridge Structure Database) survey with the help of ConQuest version 1.3 shows 185 and 96 hits based on the TIB and TFA2− ligands, respectively, the study of a combination of them in one CP has not been done yet. In order to further study mixed two kinds of ligands based CPs and investigate the influence of reactant molar ratio on the coordination connectivity and related network, we designed the reactions of them with Mn(II) salt. In this work, we used Hfba and bib as organic ligands for Mn(II) centers. These combinations afforded a two-dimensional CP, [Mn(TFA)(TIB2)] n (I), which has been synthesized by hydrothermal methods and characterized by single-crystal X-ray diffraction (SCXRD).

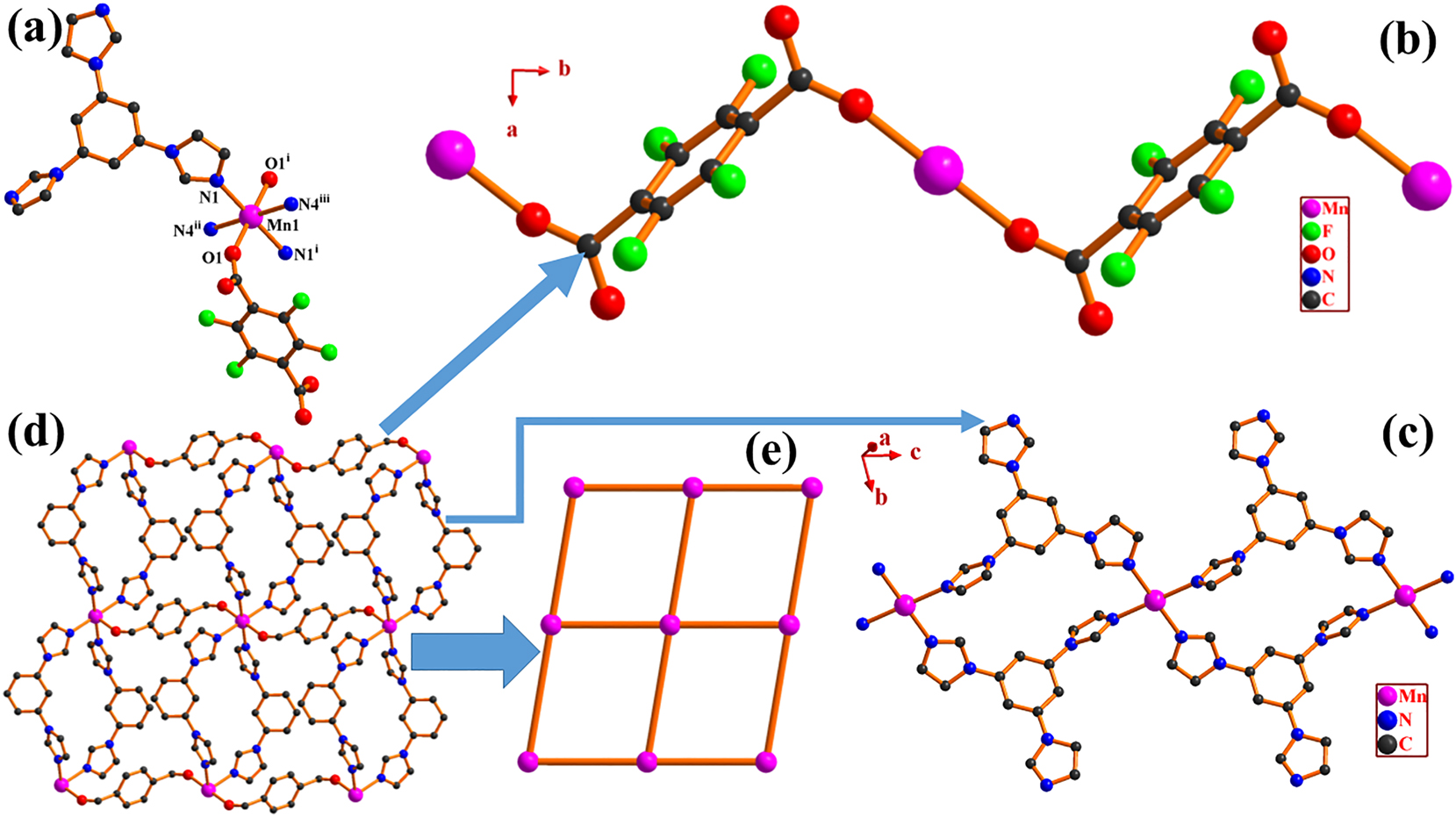

The single-crystal X-ray diffraction experiment shows that I is a two-dimensional (2D) network coordination polymer and crystallizes in a triclinic crystal system with the

It is interesting to note that the Mn(II) cations are connected by TFA2− dianions to construct a one-dimensional (1D) [Mn2(TFA)] n linear chain along b axis. The distance between Mn(II) and Mn(II) within the [Mn2(TFA)] n chain is 9.92(9) Å. The [Mn2(TFA)] n chains are further connected by TIB ligands resulting in a two-dimensional (2D) network structure (Figure). The distance between Mn(II) and Mn(II) within the [Mn2(TIB)] n chain is 11.51(7) Å. From a topological perspective, if each Mn2+ core serves as a 4-connected node and is linked by 2 TFA2− and 2 TIB ligands, and each TFA2− and TIB chelates or μ2 bridges two Mn(II) cations acting as a 2-connected linker. The 2D structure of I can be simplified as a 4-c unimodal sql topology with a Schläfli symbol {44.62} as analyzed with the TOPOS 4.0 program. 22

In the crystal of I the analysis of potential hydrogen bonds and schemes with d(D⋯A) ⟨R(D) + R(A) + 0.50, d(H⋯A) ⟨R(H) + R(A)−0.12 Å, D–H⋯A⟩ 100.0° are calculated by PLATON software. The calculation results indicate that there are no classic hydrogen bonds found except for C–H⋯F and C–H⋯O interactions. All potential hydrogen bond acceptors and donors participate in no classic hydrogen bond interactions. In detail, two weak C–H⋯O no classic intermolecular hydrogen bonds are formed between C13 and O2 v (C13–H13⋯O2 v , C13 as donor, O2 v as acceptor; bond distances: C13–H13 = 0.93, H13⋯O2 v = 2.57, and C13⋯O2 v = 3.477(2) Å; bond angle: C13–H13⋯O2 v = 164°, symmetry code: v x, y−1, z), and between C17 and O2 (C17–H17⋯O2 v , C17 as donor, O2 as acceptor; bond distances: C17–H17 = 0.93, H17⋯O2 v = 2.43, and C17⋯O2 v = 3.358(3) Å; bond angle: C17–H17⋯O2 v = 173°). More significantly, three halogen hydrogen bonds C–H⋯F lies in I, i.e., C11–H11⋯F2ii (C11 as donor, F2ii as acceptor; bond distances: C11–H11 = 0.93, H11⋯F2ii = 2.48, and C11⋯F2ii = 3.240(2) Å; bond angle: C11–H11⋯F2ii = 139°), C14–H14⋯F2ii (C14 as donor, F2ii as acceptor; bond distances: C14–H14 = 0.93, H14⋯F2ii = 2.48, and C14⋯F2ii = 3.120(2) Å; bond angle: C14–H14⋯F2ii = 126°), C18–H18⋯F2ii (C18 as donor, F2ii as acceptor; bond distances: C18–H18 = 0.93, H18⋯F2ii = 2.48, and C18⋯F2ii = 3.368(2) Å; bond angle: C18–H18⋯F2ii = 159°), resulting in a supramolecular three-dimensional (3D) C–H⋯F and C–H⋯O hydrogen bonding network.

In addition, it obviously exist either offset face-to-face π⋯π or edge-to-face C–X⋯π (X = H, O) stacking interactions calculated by PLATON program. The offset face-to-face π⋯π interactions between imidazole rings (Cg1 and Cg3) and benzene rings (Cg4 and Cg5) may be separated into three groups, i.e. (1) Cg1⋯Cg4i, Cg1⋯Cg4 v , Cg4⋯Cg1i, and Cg4⋯Cg1vi; (2) Cg3⋯Cg5vii and Cg5⋯Cg3vii; (3) Cg3⋯Cg5viii and Cg5⋯Cg3viii (symmetry codes: vi x, 1+y, z; vii 1−x, 1−y, 1−z; viii 2−x, 1−y, 1-z). Their Cg–Cg, CgI_Perp, and the dihedral angles range from 3.5815(12) to 3.9663(12), 3.1850(7) to 3.8259(10) Å, and 13.16(11) to 14.39(11)°, respectively. It is worth mentioning that the adjacent two-dimensional sheets linked together dependent not only by C–H⋯O, C–H⋯F, and π⋯π, but also by two edge-to-face C–X⋯π (X = H, O) stacking interactions, i.e. between the Cg1ix and C15–H15 (C15–H15⋯Cg1ix, symmetry code: ix 2−x, 2−y, 1−z), between the Cg2ix and C1–O2 (C1–HO2⋯Cg2ix). The C15–H15⋯Cg1ix, C1–O2⋯Cg2ix (Y–X⋯Cg) dihedral angle are 130 and 117.59(12)°, and with H15⋯Cg1ix, O2⋯Cg2ix (X⋯Cg) distances of 2.96 and 3.6020(18) Å, and C15⋯Cg1ix, C1⋯Cg2ix (Y⋯Cg) distance of 3.638(2) and 4.315(2) Å, respectively. However, their contribution to the overall lattice energy must be very small. Thus a supramolecular 3D network fragment is formed by C–H⋯X (X = O or F) and π⋯π, C–X⋯π (X = H, O) interactions stabilizing the coordination polymer.

Funding source: This research was funded by the Guangxi Natural Science Foundation

Award Identifier / Grant number: 2025GXNSFAA069072

Award Identifier / Grant number: 2025GXNSFHA069144

Funding source: the Guangxi Science and Technology Major Project

Award Identifier / Grant number: AB25069382

Funding source: the Beibu Gulf University High-level Talent Research Start-up Project in 2024

Award Identifier / Grant number: 24KYQD04

Funding source: the Research Fund of Guangxi Education Department

Award Identifier / Grant number: 2025KY0481

Funding source: the National Natural Science Foundation of China

Award Identifier / Grant number: 22065001

Funding source: the Innovation Project of Guangxi Graduate Education

Award Identifier / Grant number: YCSW2025621

Funding source: the Innovative Training Program for Guangxi Province College Students

Award Identifier / Grant number: 202511607253

Funding source: the Guangxi Key Laboratory of Green Chemical Materials and Safety Technology, Beibu Gulf University

Award Identifier / Grant number: 2023ZZKT01

-

Author contributions: All the authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this submitted manuscript and approved submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest regarding this article.

-

Research funding: This research was funded by the Guangxi Natural Science Foundation (Grant Nos. 2025GXNSFAA069072 and 2025GXNSFHA069144), the Guangxi Science and Technology Major Project (Grant No. AB25069382), the Beibu Gulf University High-level Talent Research Start-up Project in 2024 (Grant No. 24KYQD04), the Research Fund of Guangxi Education Department (2025KY0481), the research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 22065001), the Innovation Project of Guangxi Graduate Education (Grant no: YCSW2025621), the Innovative Training Program for Guangxi Province College Students (Grant No. 202511607253), and the Guangxi Key Laboratory of Green Chemical Materials and Safety Technology, Beibu Gulf University (Grant No. 2023ZZKT01).

References

1. Oxford Diffraction Ltd. CrysAlisPRO; Rigaku Oxford Diffraction, Version 1.171.39.6a: England, 2018.Search in Google Scholar

2. Dolomanov, O. V.; Bourhis, L. J.; Gildea, R. J.; Howard, J. A. K.; Puschmann, H. Olex2: A Complete Structure Solution, Refinement and Analysis Program. J. Appl. Cryst. 2009, 42, 339–341; https://doi.org/10.1107/s0021889808042726.Search in Google Scholar

3. Sheldrick, G. M. Shelxtl – Integrated Space-Group and Crystal-Structure Determination. Acta Crystallogr. 2015, A71, 3–8.10.1107/S2053273314026370Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

4. Sheldrick, G. M. Crystal Structure Refinement with Shelxl. Acta Crystallogr. 2015, C71, 3–8; https://doi.org/10.1107/s2053229614024218.Search in Google Scholar

5. Spek, A. L. Structure Validation in Chemical Crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. 2009, D65, 148–155; https://doi.org/10.1107/s090744490804362x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

6. Ye, J.-W.; Zhou, X.; Wang, Y.; Huang, R.-K.; Zhou, H.-L.; Cheng, X.-N.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, J.-P. Room-Temperature Sintered Metal-Organic Framework Nanoparticles: A New Type of Optical Ceramics. Sci. China Mater. 2018, 61, 424–428; https://doi.org/10.1007/s40843-017-9184-1.Search in Google Scholar

7. Gao, C.; Jiang, Z.; Qi, S.; Wang, P.; Jensen, L. R.; Johansen, M.; Christensen, C. K.; Zhang, Y.; Ravnsbæk, D. B.; Yue, Y. Metal-Organic Framework Glass Anode with an Exceptional Cycling-Induced Capacity Enhancement for Lithium-Ion Batteries. Adv. Mater. 2022, 34, 2110048; https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.202110048.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

8. Zhang, Z.; Zhao, Y. Transparent and High-Porosity Aluminum Alkoxide Network-Forming Glasses. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 7339; https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-51845-1.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

9. Kong, C.; Du, H.; Chen, L.; Chen, B. Nanoscale MOF/Organosilica Membranes on Tubular Ceramic Substrates for Highly Selective Gas Separation. Energy Environ. Sci. 2017, 10, 1812–1819; https://doi.org/10.1039/c7ee00830a.Search in Google Scholar

10. Liu, Z.; Navas, J. L.; Han, W.; Ibarra, M. R.; Kwan, J. K. C.; Yeung, K. L. Gel Transformation as a General Strategy for Fabrication of Highly Porous Multiscale MOF Architectures. Chem. Sci. 2023, 14, 7114–7125; https://doi.org/10.1039/d3sc00905j.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

11. Liu, H.; Xia, H.; Yao, R.; Hu, J.; Zhang, L.; Jin, H.; Li, Y. Gas Transport Mechanisms Through MOF Glass Membranes. Adv. Membr. 2024, 4, 100104; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.advmem.2024.100104.Search in Google Scholar

12. Yin, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Wan, S.; Yang, J.; Shi, Z.; Peng, S.-X.; Chen, M.-Z.; Xie, T.-Y.; Zeng, T.-W.; Yamamuro, O.; Nirei, M.; Akiba, H.; Zhang, Y.-B.; Yu, H.-B.; Zeng, M.-H. Synergistic Stimulation of Metal–Organic Frameworks for Stable Super-Cooled Liquid and Quenched Glass. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 13021–13025; https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.2c04532.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

13. Wang, Y.; Jin, H.; Ma, Q.; Mo, K.; Mao, H.; Feldhoff, A.; Cao, X.; Li, Y.; Pan, F.; Jiang, Z. A MOF Glass Membrane for Gas Separation. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 4365–4369; https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.201915807.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

14. Madsen, R. S. K.; Qiao, A.; Sen, J.; Hung, I.; Chen, K.; Gan, Z.; Sen, S.; Yue, Y. Ultrahigh-Field 67Zn NMR Reveals Short-Range Disorder in Zeolitic Imidazolate Framework Glasses. Science 2020, 367, 1473–1476; https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaz0251.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

15. Xu, T.; Paul, S.; Zhang, C.; Azam, M.; Han, B.-L.; Si, W.-D.; Wang, Z.; Gao, Z.-Y.; Anoop, A.; Tung, C.-H.; Sun, D. Boosting Circularly Polarized Luminescent and Decagram–Scale Mechanochemistry Synthesis of Atomically Precise Superstructure from Achiral Silver Cluster and Chiral Cyclodextrin. CCS Chem. 2025, 7, 519–531; https://doi.org/10.31635/ccschem.024.202404301.Search in Google Scholar

16. Xue, W. L.; Klein, A.; Skafi, M. E.; Weiß, J.-B.; Egger, F.; Ding, H.; Vasa, S. K.; Liebscher, C.; Zobel, M.; Linser, R.; Tan, J. C.; Henke, S. Mechanochemical Synthesis Enables Melting, Glass Formation and Glass–Ceramic Conversion in a Cadmium–Based Zeolitic Imidazolate Framework. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2025, 147, 15625–15635; https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.5c02767.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

17. Wang, L.; Yan, Z.-H.; Xiao, Z.; Guo, D.; Wang, W.; Yang, Y. Reactant Ratio-Modulated Entangled Cd(II) Coordination Polymers Based on Rigid Tripodal Imidazole Ligand and Tetrabromoterephthalic Acid: Interpenetration, Interdigitation and Self-Penetration. CrystEngComm 2013, 15, 5552–5560; https://doi.org/10.1039/c3ce40273h.Search in Google Scholar

18. Liu, S.; Dong, Q.; Wang, D.; Wang, Y.; Wang, H.; Huang, Y.; Wang, S.; Liu, L.; Duan, J. Interplay of Tri- and Bidentate Linkers to Evolve Micropore Environment in a Family of Quasi-3D and 3D Porous Coordination Polymers for Highly Selective CO2 Capture. Inorg. Chem. 2019, 58, 16241–16249; https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.inorgchem.9b02774.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

19. Su, Z.; Fan, J.; Okamura, T.; Sun, W. Y.; Ueyama, N. Ligand–Directed and pH–Controlled Assembly of Chiral 3d-3d Heterometallic Metal-Organic Frameworks. Cryst. Growth Des. 2010, 10, 3515–3521; https://doi.org/10.1021/cg100418a.Search in Google Scholar

20. Li, C.-P.; Yu, Q.; Zhang, Z.-H.; Du, M. Multifarious ZnII and CdII Coordination Frameworks Constructed by a Versatile trans-1-(2-Pyridyl)-2-(4-Pyridyl)Ethylene Tecton and Various Benzenedicarboxyl Ligands. CrystEngComm 2010, 12, 834–844; https://doi.org/10.1039/b912001g.Search in Google Scholar

21. Li, C.-P.; Chen, J.; Du, M. Structural Diversification and Metal-Directed Assembly of Coordination Architectures Based on Tetrabromoterephthalic Acid and a Bent Dipyridyl Tecton 2,5-Bis(4-Pyridyl)-1,3,4-Oxadiazole. CrystEngComm 2010, 12, 4392–4402; https://doi.org/10.1039/c003738a.Search in Google Scholar

22. Blatov, V. A.; Shevchenko, A. P.; Proserpio, D. M. Applied Topological Analysis of Crystal Structures with the Program Package ToposPro. Cryst. Growth Des. 2014, 14, 3576–3586; https://doi.org/10.1021/cg500498k.Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- New Crystal Structures

- Crystal structure of (S)-N-(10-((2,2-dimethoxyethyl)amino)-1,2,3-trimethoxy-9-oxo-5,6,7,9-tetrahydrobenzo[a]heptalen-7-yl)acetamide, C25H32N2O7

- The crystal structure of 6,6′-difluoro-3,3′-dimethyl-5,5′-di(10H-phenoxazin-10-yl)- [1,1′-biphenyl]-2,2′-dicarbonitrile, C40H24F2N4O2

- Crystal structure of poly[(di-ethylenediamine-κ2N,N′)cadmium(II) tetradedocyloxidohexavanadate] (V4+/V5+ = 2/1), C4H16CdN4O14V6

- The crystal structure of poly[bis(dimethylformamide-κ1N)-(μ4-2′,3,3″,5′-tetrakis(trifluoromethyl)-[1,1′:4′,1″-terphenyl]-4,4″-dicarboxylato-κ4 O,O′: O″,O‴)dicadmium(II)], C27H15CdF12NO5

- Crystal structure of bis(μ2-ferrocenylcarboxylato-O,O′)-(μ3-oxido-κ3O:O:O)-bis(μ2-salicyladoximato-κ2N,O,O′)-(μ2-isopropoxo)-tris(isopropoxy-κ1O trititanium(IV)), C48H55N2O13Fe2Ti3

- Crystal structure of 3-(diethylamino)-7,9,11-trimethyl-8-phenyl-6H,13H-12λ4,13λ4-chromeno[3′,4′:4,5]pyrrolo[1,2-c]pyrrolo[2,1-f][1,3,2]diazaborinin-6-one, C28H26BF2N3O2

- The crystal structure of catena-poly[aqua-μ2-2-nitro-benzene-1,3-dicarboxylato-κ2O,O′)-(1,10-phenanthroline-κ2N,N′)-zinc(II)], C20H13N3O7Zn

- Crystal structure of poly[diaqua-{μ3-1-(3-carboxylatophenyl)-4-oxo-1,4-dihydropyridazine-3-carboxylato-κ4O,O′:O′′:O′′′′}manganese(II)] hydrate

- Crystal structure of N′-((1-hydroxycyclohexyl)(phenyl)methyl)-2-methoxybenzohydrazide methanol solvate, C22H28N2O4

- The cocrystal of caffeic acid — progesterone — water (1/2/1), C51H70O9

- Crystal structure of (((oxido(quinolin-6-yl)methoxy)triphenyl-λ5-stibanyl)oxy)(quinolin-7-yl)methanolate

- Crystal structure of [(E)-6′-(diethylamino)-2-(2-(((E)-pyren-1-ylmethylene)amino)ethyl)-4′-(2-((E)-1,3,3-trimethylindolin-2-ylidene)ethylidene)-1′,2′,3′,4′-tetrahydrospiro[isoindoline-1,9′-xanthen]-3-one]-methanol, solvate C57H56N4O3

- The crystal structure of 1-(acridin-9-yl)pyrrolidine-2,5-dione, C17H22N2O2

- Crystal structure of N-(4-acetylphenyl)-2-(6-methoxynaphthalen-2-yl)propanamide, C22H21NO3

- The crystal structure of 5,10,15,20-tetrakis(4-(1H-1,2,4-triazol-1-yl)phenyl)porphyrin, C52H34N16

- Crystal structure of hexacarbonyl-μ2-[phenylmethanedithiolato-κ4S:S,S′:S′]diiron (Fe–Fe) C13H6Fe2O6S2

- Crystal structure of diiodo-bis(1-((2-propyl-1H-benzo[d]imidazol-1-yl)methyl)-1H-benzo[d][1,2,3]triazole-κ1N)cadmium(II), C34H34CdI2N10

- Crystal structure of (E)-(3-(3-bromophenyl)acryloyl)ferrocene, C19H15BrFeO

- Crystal structure of catena-poly(μ2-6-chloropyridine-2-carboxylato-κ3N,O:O′)(6-chloropyridine-2-carboxylato-κ2O,N)copper(II), C12H6Cl2N2O4Cu

- Crystal structure of poly[diaqua-μ 3-(5-(3,5-dicarboxy-2,4,6-trimethylbenzyl)-2,4,6-trimethylisophthalato)-κ 6O,O′:O″,O‴:O‴′,O‴″) terbium(III)-monohydrate], C23H28TbO12

- Crystal structure of (E)-2-(((5-chloro-3-methyl-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)methylene)amino)-3′,6′-dihydroxyspiro[isoindoline-1,9′-xanthen]-3-one – ethanol (1/2), C35H33ClN4O6

- The crystal structure of 3-(5-amino-3-phenylisoxazol-4-yl)-4-chloro-3-hydroxyindolin-2-one, C17H12ClN3O3

- The crystal structure of dimethylammonium 4-[2-(4-fluorophenyl)-4, 5-diphenyl-1H-imidazol-1-yl]benzenesulfonate, C29H26FN3O3S

- Crystal structure of (R)-2-ammonio-3-((5-carboxypentyl)thio)propanoate

- Crystal structure of 4-cyclohexyl-5-(thiophen-2-yl)-2,4-dihydro-3H-1,2,4-triazole-3-thione, C12H15N3S2

- The crystal structure of 4,6-bis(dimethylamino)-2-fluoroisophthalonitrile, C12H13FN4

- Hydrogen bonding in the crystal structure of nicotin-1,1′-dium tetrabromidomanganate(II)

- The crystal structure of bis(2-bromobenzyl)(2-((2-oxybenzylidene)amino)-4-methylpentanoato-κ3N, O,O′)tin(IV), C27H27Br2NO3Sn

- Crystal structure of (E)-(3-(p-tolyl)acryloyl)ferrocene, C20H18FeO

- Crystal structure of (E)-7-fluoro-2-((5-(4-methylpiperazin-1-yl)pyridin-2-yl)methylene)-3,4-dihydronaphthalen-1(2H)-one, C21H22FN3O

- Crystal structure of (E)-7-methoxy-2-((5-(4-methylpiperazin-1-yl)pyridin-2-yl)methylene)-3,4-dihydronaphthalen-1(2H)-one, C22H25N3O2

- The crystal structure of poly(bis(μ2-1,3,5-tri(1H-imidazol-1-yl)benzene-κ2N:N′)-(μ2-2,3,5,6-tetrafluoroterephthalato-κ2O:O′)-manganese(II), C38H24F4N12O4Mn

- Crystal structure of (3,4-dimethoxybenzyl)triphenylphosphonium bromide ethanol solvate, C29H32BrO3P

- Crystal structure of tetraethylammonium hydrogencarbonate – (diaminomethylene)thiourea – water (2/1/3)

- Crystal structure of N, N-Dimethyl-N′-tosylformimidamide, C10H14N2O2S

- The crystal structure of ethyl 2-methyl-5-oxo-4-(2-methoxyphenyl)-1,4,5,6,7,8-hexahydroquinoline-3-carboxylate, C20H23N2O4

- Crystal structure of bis(μ2-1,5-bis[(E)-1-(2-hydroxyphenyl)ethylidene] thiocarbonohydrazide)-bis(dimethylformamide)-dizinc(II) dimethylformamide solvate, C40H46N10O6S2Zn2⋅C3H7NO

- Crystal structure of azido-κ1N{hydridotris(3-tert-butyl-5-methylpyrazol-1-yl)borato-κ3N,N′,N″}copper(II), C24H40BCuN9

- The crystal structure of fac-tricarbonyl(1,10-phenanthroline-κ2N,N′)-(azido-κ1N)rhenium(I), C15H8N5O3Re

- Crystal structure of 4-((triphenylphosphonio)methyl)pyridin-1-ium tetrachloridozincate(II), C24H22Cl4NPZn

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- New Crystal Structures

- Crystal structure of (S)-N-(10-((2,2-dimethoxyethyl)amino)-1,2,3-trimethoxy-9-oxo-5,6,7,9-tetrahydrobenzo[a]heptalen-7-yl)acetamide, C25H32N2O7

- The crystal structure of 6,6′-difluoro-3,3′-dimethyl-5,5′-di(10H-phenoxazin-10-yl)- [1,1′-biphenyl]-2,2′-dicarbonitrile, C40H24F2N4O2

- Crystal structure of poly[(di-ethylenediamine-κ2N,N′)cadmium(II) tetradedocyloxidohexavanadate] (V4+/V5+ = 2/1), C4H16CdN4O14V6

- The crystal structure of poly[bis(dimethylformamide-κ1N)-(μ4-2′,3,3″,5′-tetrakis(trifluoromethyl)-[1,1′:4′,1″-terphenyl]-4,4″-dicarboxylato-κ4 O,O′: O″,O‴)dicadmium(II)], C27H15CdF12NO5

- Crystal structure of bis(μ2-ferrocenylcarboxylato-O,O′)-(μ3-oxido-κ3O:O:O)-bis(μ2-salicyladoximato-κ2N,O,O′)-(μ2-isopropoxo)-tris(isopropoxy-κ1O trititanium(IV)), C48H55N2O13Fe2Ti3

- Crystal structure of 3-(diethylamino)-7,9,11-trimethyl-8-phenyl-6H,13H-12λ4,13λ4-chromeno[3′,4′:4,5]pyrrolo[1,2-c]pyrrolo[2,1-f][1,3,2]diazaborinin-6-one, C28H26BF2N3O2

- The crystal structure of catena-poly[aqua-μ2-2-nitro-benzene-1,3-dicarboxylato-κ2O,O′)-(1,10-phenanthroline-κ2N,N′)-zinc(II)], C20H13N3O7Zn

- Crystal structure of poly[diaqua-{μ3-1-(3-carboxylatophenyl)-4-oxo-1,4-dihydropyridazine-3-carboxylato-κ4O,O′:O′′:O′′′′}manganese(II)] hydrate

- Crystal structure of N′-((1-hydroxycyclohexyl)(phenyl)methyl)-2-methoxybenzohydrazide methanol solvate, C22H28N2O4

- The cocrystal of caffeic acid — progesterone — water (1/2/1), C51H70O9

- Crystal structure of (((oxido(quinolin-6-yl)methoxy)triphenyl-λ5-stibanyl)oxy)(quinolin-7-yl)methanolate

- Crystal structure of [(E)-6′-(diethylamino)-2-(2-(((E)-pyren-1-ylmethylene)amino)ethyl)-4′-(2-((E)-1,3,3-trimethylindolin-2-ylidene)ethylidene)-1′,2′,3′,4′-tetrahydrospiro[isoindoline-1,9′-xanthen]-3-one]-methanol, solvate C57H56N4O3

- The crystal structure of 1-(acridin-9-yl)pyrrolidine-2,5-dione, C17H22N2O2

- Crystal structure of N-(4-acetylphenyl)-2-(6-methoxynaphthalen-2-yl)propanamide, C22H21NO3

- The crystal structure of 5,10,15,20-tetrakis(4-(1H-1,2,4-triazol-1-yl)phenyl)porphyrin, C52H34N16

- Crystal structure of hexacarbonyl-μ2-[phenylmethanedithiolato-κ4S:S,S′:S′]diiron (Fe–Fe) C13H6Fe2O6S2

- Crystal structure of diiodo-bis(1-((2-propyl-1H-benzo[d]imidazol-1-yl)methyl)-1H-benzo[d][1,2,3]triazole-κ1N)cadmium(II), C34H34CdI2N10

- Crystal structure of (E)-(3-(3-bromophenyl)acryloyl)ferrocene, C19H15BrFeO

- Crystal structure of catena-poly(μ2-6-chloropyridine-2-carboxylato-κ3N,O:O′)(6-chloropyridine-2-carboxylato-κ2O,N)copper(II), C12H6Cl2N2O4Cu

- Crystal structure of poly[diaqua-μ 3-(5-(3,5-dicarboxy-2,4,6-trimethylbenzyl)-2,4,6-trimethylisophthalato)-κ 6O,O′:O″,O‴:O‴′,O‴″) terbium(III)-monohydrate], C23H28TbO12

- Crystal structure of (E)-2-(((5-chloro-3-methyl-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)methylene)amino)-3′,6′-dihydroxyspiro[isoindoline-1,9′-xanthen]-3-one – ethanol (1/2), C35H33ClN4O6

- The crystal structure of 3-(5-amino-3-phenylisoxazol-4-yl)-4-chloro-3-hydroxyindolin-2-one, C17H12ClN3O3

- The crystal structure of dimethylammonium 4-[2-(4-fluorophenyl)-4, 5-diphenyl-1H-imidazol-1-yl]benzenesulfonate, C29H26FN3O3S

- Crystal structure of (R)-2-ammonio-3-((5-carboxypentyl)thio)propanoate

- Crystal structure of 4-cyclohexyl-5-(thiophen-2-yl)-2,4-dihydro-3H-1,2,4-triazole-3-thione, C12H15N3S2

- The crystal structure of 4,6-bis(dimethylamino)-2-fluoroisophthalonitrile, C12H13FN4

- Hydrogen bonding in the crystal structure of nicotin-1,1′-dium tetrabromidomanganate(II)

- The crystal structure of bis(2-bromobenzyl)(2-((2-oxybenzylidene)amino)-4-methylpentanoato-κ3N, O,O′)tin(IV), C27H27Br2NO3Sn

- Crystal structure of (E)-(3-(p-tolyl)acryloyl)ferrocene, C20H18FeO

- Crystal structure of (E)-7-fluoro-2-((5-(4-methylpiperazin-1-yl)pyridin-2-yl)methylene)-3,4-dihydronaphthalen-1(2H)-one, C21H22FN3O

- Crystal structure of (E)-7-methoxy-2-((5-(4-methylpiperazin-1-yl)pyridin-2-yl)methylene)-3,4-dihydronaphthalen-1(2H)-one, C22H25N3O2

- The crystal structure of poly(bis(μ2-1,3,5-tri(1H-imidazol-1-yl)benzene-κ2N:N′)-(μ2-2,3,5,6-tetrafluoroterephthalato-κ2O:O′)-manganese(II), C38H24F4N12O4Mn

- Crystal structure of (3,4-dimethoxybenzyl)triphenylphosphonium bromide ethanol solvate, C29H32BrO3P

- Crystal structure of tetraethylammonium hydrogencarbonate – (diaminomethylene)thiourea – water (2/1/3)

- Crystal structure of N, N-Dimethyl-N′-tosylformimidamide, C10H14N2O2S

- The crystal structure of ethyl 2-methyl-5-oxo-4-(2-methoxyphenyl)-1,4,5,6,7,8-hexahydroquinoline-3-carboxylate, C20H23N2O4

- Crystal structure of bis(μ2-1,5-bis[(E)-1-(2-hydroxyphenyl)ethylidene] thiocarbonohydrazide)-bis(dimethylformamide)-dizinc(II) dimethylformamide solvate, C40H46N10O6S2Zn2⋅C3H7NO

- Crystal structure of azido-κ1N{hydridotris(3-tert-butyl-5-methylpyrazol-1-yl)borato-κ3N,N′,N″}copper(II), C24H40BCuN9

- The crystal structure of fac-tricarbonyl(1,10-phenanthroline-κ2N,N′)-(azido-κ1N)rhenium(I), C15H8N5O3Re

- Crystal structure of 4-((triphenylphosphonio)methyl)pyridin-1-ium tetrachloridozincate(II), C24H22Cl4NPZn