Abstract

C4H16CdN4O14V6, orthorhombic, Pca21, a = 16.545(6) Å, b = 6.515(3) Å, c = 17.096(7) Å, V = 1842.9(13) Å3, Z = 4, Rgt(F) = 0.0306, wRref(F2) = 0.0796, T = 296 (2) K.

1 Source of materials

The title compound [Cd(C2H8N2)2][VIV4VV2O14] (Table 1) was prepared under the hydrothermal conditions. The mixture of Cd(NO3)2·4H2O (0.32 g), NH4VO3 (0.38 g), ethylenediamine (C10H8N2, 0.60 mL), glacial acetic acid (CH3COOH, 0.8 mL) and H2O (5.0 mL) was stirred for 2 h, transferred to a 50 mL Teflon-lined stainless steel vessels and heated at 150 °C for 5 days. The black block crystals were obtained, washed with deionized water and dried at RT (yield: ca. 72 % based on NH4VO3).

Data collection and handling.

| Crystal: | Block |

| Size: | 0.26 × 0.24 × 0.19 mm |

| Wavelength: μ: |

MoKα radiation (0.71073 Å) 4.12 mm−1 |

| Diffractometer, scan mode: θmax, completeness: |

Bruker APEX-II, φ and ω scans 26.0°, 99 % |

| N(hkl)measured, N(hkl)unique, Rint: | 10909, 3577, 0.037 |

| Criterion for Iobs, N(hkl)gt: | Iobs > 2σ(Iobs), 3449 |

| N(param)refined: | 264 |

| Programs: | Bruker, 1 Olex2, 2 , 3 SHELX 4 |

2 Experimental details

H atoms from the organic ligand ethylenediamine were positioned geometrically and refined using a riding model, with C–H = 0.97 Å and N–H = 0.90 Å, with Uiso (H) = 1.2 times Ueq(C) and Ueq(N). The absolute structure was established by refinement of the Flack parameter (0.41(5) from 3577 selected quotients) according to the method from ref. 5 . The restrictive refinement of “twin −1 0 0 0 –1 0 0 0 –1” was applied to deal with the crystal structure (BASF 0.411).

3 Comment

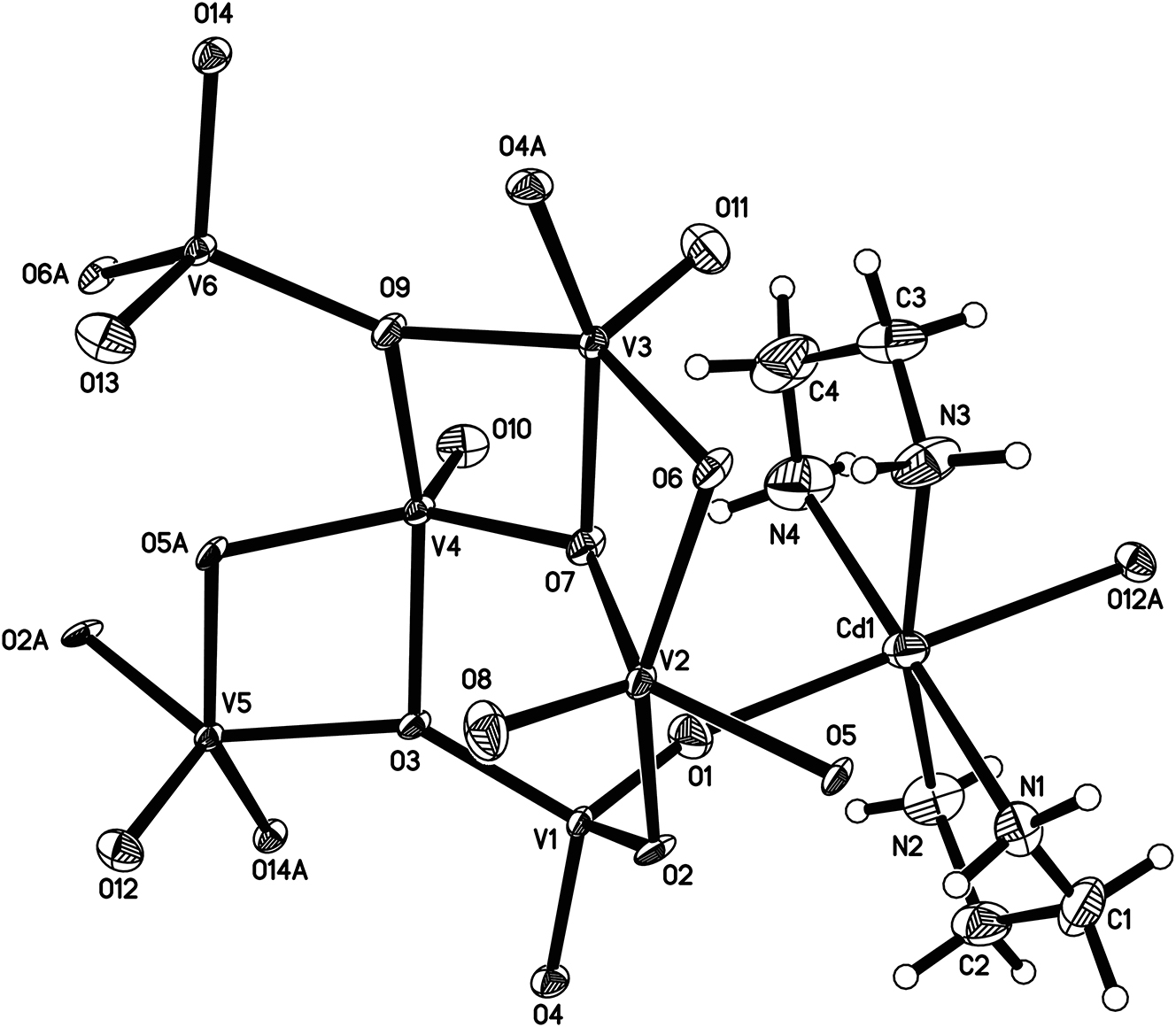

In recent years, polyoxovanadates have attracted extensive attention due to their fascinating structural features, multiple valence states and flexible coordination geometry. 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 The use of vanadate anions as building blocks has become an effective strategy for the preparation of organic-inorganic hybrid polyoxovanadates. 12 , 13 Here, we have synthesized a novel Cd2+-based polyoxovanadate [Cd(C2H8N2)2][VIV4VV2O14] (V4+/V5+ = 2/1) by means of organic ligand ethylenediamine under hydrothermal conditions. X-ray single-crystal diffraction structural analysis reveals that its molecular structure is composed of one coordinating cation [Cd(C2H8N2)2]2+ and one vanadate anion [VIV4VV2O14]2−. A part of the title crystal structure is shown in the Figure. In order to determine the valence states of the V and Cd sites in the crystal structure, the oxidation state of each metal site in the crystal structure is obtained by the method of bond-valence calculation. The results show that the valence states of V(1) and V(6) sites are +V, the valence states of V(2), V(3), V(4) and V(5) sites are +IV, and the valence state of Cd site is +II. Within the vanadate anion [VIV4VV2 O14]2−, the V sites can be divided into two types depending to their coordination numbers: each V(1) and V(6) site adopts a 4-coordinated tetrahedral geometry with four surrounding oxygen atoms, while each V(2), V(3), V(4) and V(5) site is respectively coordinated with five surrounding oxygen atoms to lead to a 5-coordinated distorted square pyramidal geometry. The coordination geometries of V(1) and V(6) sites are similar as those of the reported vanadate compounds α-[Cu(mIM)4]V2O6, and β-[Cu(mIM)4]V2O6 (mIM = 1-methylimidazole), 14 while the coordination geometries of V(2), V(3), V(4) and V(5) sites are compared with those of known {V6O18} cluster-containing compounds [CuII(en)2]4{Na(H2O)(μ–OH)[B(OH)2]}2[(VVO)2(VIVO)10O6(B18O36(OH)6)]}·7H2O 15 and [CdII3(H2O)6][(VIVO)6(VVO)6(O6)(B18O36(OH)6)]·10H2O (en = ethylenediamine). 16 The lengths of the V–O bonds in the title compound range from 1.586(3) Å to 2.014(4) Å, and the bond angles of O–V–O range from 77.41(13)° to 152.22(16)°. These parameters of bond lengths and bond angles are within their reasonable ranges and can be compared with previously reported vanadate compounds. 12 , 13 , 14 The distorted {VO5} square pyramids are linked by bridging oxygen atoms [O(3), O(5), O(6), O(7) and O(9)], forming a tetranuclear {V4O14} cluster. Then, the tetranuclear clusters {V4O14} are further connected with the surrounding {VO4} units by the bridging oxygen atoms [O(3) and O(9)], resulting in the formation of the vanadate anion [VIV4VV2O14]2−. These adjacent vanadate anionic structural units are finally extend to a 2D layered anionic structure along the a, b and c axis by bridging oxygen atoms [O(1), O(5), O(4) and O(14)]. The adjacent anionic layers are linked to [Cd(C2H8N2)2]2+ cations by bridging oxygen atoms (O1 and O12), generating a 3D framework architecture. The bond lengths of Cd–O and Cd–N fall in the ranges of 2.372(4) Å–2.555(4) Å and 2.253(5) Å–2.278(6) Å, respectively. The bond angles of O–Cd–N, N–Cd–N fall in the ranges of 81.7(2)°–91.2(2)° and 76.5(2)°–179.3(2)°, respectively. The bond angle O–Cd–O is 176.73(13)°. These bond lengths and bond angles can be compared with the known related Cd-containing compounds [Cd(en)3]{[Cd(H2O)(en)]6[B20V12O60(OH)2]}·8H2O (en = ethylenediamine) 17 and poly[aqua-(pyridine-3-carboxylato-κ1N)(pyridine-3-carboxylato-κ2O,O′) cadmium(II)] dihydrate (C12H14N2O7Cd). 18 In addition, the N–H⋯O hydrogen bonds, which contribute to the stability of the crystal structure, can be observed in the title compound.

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Henan (no. 252300421341) and the National Natural Science Foundation Project Cultivation Fund of Nanyang Normal University (no. 2025PY032).

References

1. Bruker Corporation, Bruker Smart Apex–II, Germany, 2008.Search in Google Scholar

2. Bourhis, L. J.; Dolomanov, O. V.; Gildea, R. J.; Howard, J. A. K.; Puschmann, H. The Anatomy of a Comprehensive Constrained, Restrained Refinement Program for the Modern Computing Environment – Olex2 Dissected. Acta Crystallogr. 2015, A71, 59–75; https://doi.org/10.1107/s2053273314022207.Search in Google Scholar

3. Dolomanov, O. V.; Bourhis, L. J.; Gildea, R. J.; Howard, J. A. K.; Puschmann, H. Olex2: a Complete Structure Solution, Refinement and Analysis Program. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2009, 42, 339–341; https://doi.org/10.1107/s0021889808042726.Search in Google Scholar

4. Sheldrick, G. M. Crystal Structure Refinement with Shelxl. Acta Crystallogr. 2015, C71, 3–8; https://doi.org/10.1107/s2053229614024218.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

5. Flack, H. D. On Enantiomorph-polarity Estimation. Acta Crystallogr. 1983, A39, 876–881; https://doi.org/10.1107/s0108767383001762.Search in Google Scholar

6. Liu, Y.; Xuan, W.; Cui, Y. Engineering Homochiral Metal–Organic Frameworks for Heterogeneous Asymmetric Catalysis and Enantioselective Separation. Adv. Mater. 2010, 22, 4112–4135; https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201000197.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

7. Hagrman, P.-J.; Finn, R.-C.; Zubieta, J. Molecular Manipulation of Solid State Structure: Influences of Organic Components on Vanadium Oxide Architectures. J. Solid State Sci. 2001, 3, 745–774; https://doi.org/10.1016/s1293-2558(01)01186-4.Search in Google Scholar

8. Jiang, H.-L.; Xu, Q. Porous Metal–Organic Frameworks as Platforms for Functional Applications. Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 3351–3370; https://doi.org/10.1039/c0cc05419d.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

9. Meek, S.-T.; Grathouse, J.-A.; Allenford, M. Metal–Organic Frameworks: a Rapidly Growing Class of Versatile Nanoporous Materials. Adv. Mater. 2011, 23, 249–267; https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201002854.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

10. Dhakshinamoorthy, A.; Alvaro, M.; Corma, A.; García, H. Delineating Similarities and Dissimilarities in the Use of Metal Organic Frameworks and Zeolites as Heterogeneous Catalysts for Organic Reactions. Dalton Trans. 2011, 40, 6344–6360; https://doi.org/10.1039/c1dt10354g.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

11. Rocha, J.; Carlos, L.-D.; Paz, F.-A.-A.; Ananias, D. Luminescent Multifunctional Lanthanides-based metal–organic Frameworks. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011, 40, 926–940; https://doi.org/10.1039/c0cs00130a.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

12. Chen, H.; Yu, Z.; Bacsik, Z.; Zhao, H.; Yao, Q.; Sun, J. Construction of Mesoporous Frameworks with Vanadoborate Clusters. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 3608–3611; https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.201311122.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

13. Chen, H.; Deng, Y.; Yu, Z.; Zhao, H.; Yao, Q.; Zou, X.; Bäckvall, J.-E.; Sun, J. 3D Open–Framework Vanadoborate as a Highly Effective Heterogeneous Pre-catalyst for the Oxidation of Alkylbenzenes. Chem. Mater. 2013, 25, 5031–5036; https://doi.org/10.1021/cm401400m.Search in Google Scholar

14. Li, J.; Huang, X.; Yang, S.; Xu, Y.; Hu, C. Controllable Synthesis, Characterization, and Catalytic Properties of Three Inorganic–Organic Hybrid Copper Vanadates in the Highly Selective Oxidation of Sulfides and Alcohols. Cryst. Growth Des. 2015, 15, 1907–1914; https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.cgd.5b00086.Search in Google Scholar

15. Feng, Y.-Q.; Ding, C.-H.; Fan, H.-T.; Zhong, Z.-G.; Qiu, D.-F.; Shi, H.-Z. Employing a New 12-connected Topological open-framework Copper Borovanadate as an Effective Heterogeneous Catalyst for Oxidation of benzyl-alkanes. Dalton Trans. 2015, 44, 18731–18736; https://doi.org/10.1039/c5dt03425f.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

16. Feng, Y.-Q.; Qiu, D.-F.; Fan, H.-T.; Li, M.; Huang, Q.-Z.; Shi, H.-Z. A New 3–D Open-Framework Cadmium Borovanadate with Plane-Shaped Channels and High Catalytic Activity for the Oxidation of Cyclohexanol. Dalton Trans. 2015, 44, 8792–8796; https://doi.org/10.1039/c5dt00873e.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

17. Feng, Y.-Q.; Wu, J.-H.; Zhong, Z.-G.; Meng, Z.-H.; Chen, S.-Y.; Liu, K.-C. Heptanuclear Cadmium Borovanadate Containing a Sandwich–Type Anionic Partial Structure {B20V12} as a Heterogeneous Photocatalyst for the Reduction of CO2 into CH4. Inorg. Chem. 2024, 63, 16515–16522; https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.inorgchem.4c02860.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

18. Feng, Y.-Q.; Chen, S.-Y.; Yue, Z.-L. Crystal Structure of poly[Aqua-(pyridine-3-carboxylato-κ1N)(pyridine-3-carboxylato-κ2 O,O′) cadmium(II)] Dihydrate. Z. Kristallogr. – N. Cryst. Struct. 2024, 239 (6), 1065–1067; https://doi.org/10.1515/ncrs-2024-0300.Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- New Crystal Structures

- Crystal structure of (S)-N-(10-((2,2-dimethoxyethyl)amino)-1,2,3-trimethoxy-9-oxo-5,6,7,9-tetrahydrobenzo[a]heptalen-7-yl)acetamide, C25H32N2O7

- The crystal structure of 6,6′-difluoro-3,3′-dimethyl-5,5′-di(10H-phenoxazin-10-yl)- [1,1′-biphenyl]-2,2′-dicarbonitrile, C40H24F2N4O2

- Crystal structure of poly[(di-ethylenediamine-κ2N,N′)cadmium(II) tetradedocyloxidohexavanadate] (V4+/V5+ = 2/1), C4H16CdN4O14V6

- The crystal structure of poly[bis(dimethylformamide-κ1N)-(μ4-2′,3,3″,5′-tetrakis(trifluoromethyl)-[1,1′:4′,1″-terphenyl]-4,4″-dicarboxylato-κ4 O,O′: O″,O‴)dicadmium(II)], C27H15CdF12NO5

- Crystal structure of bis(μ2-ferrocenylcarboxylato-O,O′)-(μ3-oxido-κ3O:O:O)-bis(μ2-salicyladoximato-κ2N,O,O′)-(μ2-isopropoxo)-tris(isopropoxy-κ1O trititanium(IV)), C48H55N2O13Fe2Ti3

- Crystal structure of 3-(diethylamino)-7,9,11-trimethyl-8-phenyl-6H,13H-12λ4,13λ4-chromeno[3′,4′:4,5]pyrrolo[1,2-c]pyrrolo[2,1-f][1,3,2]diazaborinin-6-one, C28H26BF2N3O2

- The crystal structure of catena-poly[aqua-μ2-2-nitro-benzene-1,3-dicarboxylato-κ2O,O′)-(1,10-phenanthroline-κ2N,N′)-zinc(II)], C20H13N3O7Zn

- Crystal structure of poly[diaqua-{μ3-1-(3-carboxylatophenyl)-4-oxo-1,4-dihydropyridazine-3-carboxylato-κ4O,O′:O′′:O′′′′}manganese(II)] hydrate

- Crystal structure of N′-((1-hydroxycyclohexyl)(phenyl)methyl)-2-methoxybenzohydrazide methanol solvate, C22H28N2O4

- The cocrystal of caffeic acid — progesterone — water (1/2/1), C51H70O9

- Crystal structure of (((oxido(quinolin-6-yl)methoxy)triphenyl-λ5-stibanyl)oxy)(quinolin-7-yl)methanolate

- Crystal structure of [(E)-6′-(diethylamino)-2-(2-(((E)-pyren-1-ylmethylene)amino)ethyl)-4′-(2-((E)-1,3,3-trimethylindolin-2-ylidene)ethylidene)-1′,2′,3′,4′-tetrahydrospiro[isoindoline-1,9′-xanthen]-3-one]-methanol, solvate C57H56N4O3

- The crystal structure of 1-(acridin-9-yl)pyrrolidine-2,5-dione, C17H22N2O2

- Crystal structure of N-(4-acetylphenyl)-2-(6-methoxynaphthalen-2-yl)propanamide, C22H21NO3

- The crystal structure of 5,10,15,20-tetrakis(4-(1H-1,2,4-triazol-1-yl)phenyl)porphyrin, C52H34N16

- Crystal structure of hexacarbonyl-μ2-[phenylmethanedithiolato-κ4S:S,S′:S′]diiron (Fe–Fe) C13H6Fe2O6S2

- Crystal structure of diiodo-bis(1-((2-propyl-1H-benzo[d]imidazol-1-yl)methyl)-1H-benzo[d][1,2,3]triazole-κ1N)cadmium(II), C34H34CdI2N10

- Crystal structure of (E)-(3-(3-bromophenyl)acryloyl)ferrocene, C19H15BrFeO

- Crystal structure of catena-poly(μ2-6-chloropyridine-2-carboxylato-κ3N,O:O′)(6-chloropyridine-2-carboxylato-κ2O,N)copper(II), C12H6Cl2N2O4Cu

- Crystal structure of poly[diaqua-μ 3-(5-(3,5-dicarboxy-2,4,6-trimethylbenzyl)-2,4,6-trimethylisophthalato)-κ 6O,O′:O″,O‴:O‴′,O‴″) terbium(III)-monohydrate], C23H28TbO12

- Crystal structure of (E)-2-(((5-chloro-3-methyl-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)methylene)amino)-3′,6′-dihydroxyspiro[isoindoline-1,9′-xanthen]-3-one – ethanol (1/2), C35H33ClN4O6

- The crystal structure of 3-(5-amino-3-phenylisoxazol-4-yl)-4-chloro-3-hydroxyindolin-2-one, C17H12ClN3O3

- The crystal structure of dimethylammonium 4-[2-(4-fluorophenyl)-4, 5-diphenyl-1H-imidazol-1-yl]benzenesulfonate, C29H26FN3O3S

- Crystal structure of (R)-2-ammonio-3-((5-carboxypentyl)thio)propanoate

- Crystal structure of 4-cyclohexyl-5-(thiophen-2-yl)-2,4-dihydro-3H-1,2,4-triazole-3-thione, C12H15N3S2

- The crystal structure of 4,6-bis(dimethylamino)-2-fluoroisophthalonitrile, C12H13FN4

- Hydrogen bonding in the crystal structure of nicotin-1,1′-dium tetrabromidomanganate(II)

- The crystal structure of bis(2-bromobenzyl)(2-((2-oxybenzylidene)amino)-4-methylpentanoato-κ3N, O,O′)tin(IV), C27H27Br2NO3Sn

- Crystal structure of (E)-(3-(p-tolyl)acryloyl)ferrocene, C20H18FeO

- Crystal structure of (E)-7-fluoro-2-((5-(4-methylpiperazin-1-yl)pyridin-2-yl)methylene)-3,4-dihydronaphthalen-1(2H)-one, C21H22FN3O

- Crystal structure of (E)-7-methoxy-2-((5-(4-methylpiperazin-1-yl)pyridin-2-yl)methylene)-3,4-dihydronaphthalen-1(2H)-one, C22H25N3O2

- The crystal structure of poly(bis(μ2-1,3,5-tri(1H-imidazol-1-yl)benzene-κ2N:N′)-(μ2-2,3,5,6-tetrafluoroterephthalato-κ2O:O′)-manganese(II), C38H24F4N12O4Mn

- Crystal structure of (3,4-dimethoxybenzyl)triphenylphosphonium bromide ethanol solvate, C29H32BrO3P

- Crystal structure of tetraethylammonium hydrogencarbonate – (diaminomethylene)thiourea – water (2/1/3)

- Crystal structure of N, N-Dimethyl-N′-tosylformimidamide, C10H14N2O2S

- The crystal structure of ethyl 2-methyl-5-oxo-4-(2-methoxyphenyl)-1,4,5,6,7,8-hexahydroquinoline-3-carboxylate, C20H23N2O4

- Crystal structure of bis(μ2-1,5-bis[(E)-1-(2-hydroxyphenyl)ethylidene] thiocarbonohydrazide)-bis(dimethylformamide)-dizinc(II) dimethylformamide solvate, C40H46N10O6S2Zn2⋅C3H7NO

- Crystal structure of azido-κ1N{hydridotris(3-tert-butyl-5-methylpyrazol-1-yl)borato-κ3N,N′,N″}copper(II), C24H40BCuN9

- The crystal structure of fac-tricarbonyl(1,10-phenanthroline-κ2N,N′)-(azido-κ1N)rhenium(I), C15H8N5O3Re

- Crystal structure of 4-((triphenylphosphonio)methyl)pyridin-1-ium tetrachloridozincate(II), C24H22Cl4NPZn

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- New Crystal Structures

- Crystal structure of (S)-N-(10-((2,2-dimethoxyethyl)amino)-1,2,3-trimethoxy-9-oxo-5,6,7,9-tetrahydrobenzo[a]heptalen-7-yl)acetamide, C25H32N2O7

- The crystal structure of 6,6′-difluoro-3,3′-dimethyl-5,5′-di(10H-phenoxazin-10-yl)- [1,1′-biphenyl]-2,2′-dicarbonitrile, C40H24F2N4O2

- Crystal structure of poly[(di-ethylenediamine-κ2N,N′)cadmium(II) tetradedocyloxidohexavanadate] (V4+/V5+ = 2/1), C4H16CdN4O14V6

- The crystal structure of poly[bis(dimethylformamide-κ1N)-(μ4-2′,3,3″,5′-tetrakis(trifluoromethyl)-[1,1′:4′,1″-terphenyl]-4,4″-dicarboxylato-κ4 O,O′: O″,O‴)dicadmium(II)], C27H15CdF12NO5

- Crystal structure of bis(μ2-ferrocenylcarboxylato-O,O′)-(μ3-oxido-κ3O:O:O)-bis(μ2-salicyladoximato-κ2N,O,O′)-(μ2-isopropoxo)-tris(isopropoxy-κ1O trititanium(IV)), C48H55N2O13Fe2Ti3

- Crystal structure of 3-(diethylamino)-7,9,11-trimethyl-8-phenyl-6H,13H-12λ4,13λ4-chromeno[3′,4′:4,5]pyrrolo[1,2-c]pyrrolo[2,1-f][1,3,2]diazaborinin-6-one, C28H26BF2N3O2

- The crystal structure of catena-poly[aqua-μ2-2-nitro-benzene-1,3-dicarboxylato-κ2O,O′)-(1,10-phenanthroline-κ2N,N′)-zinc(II)], C20H13N3O7Zn

- Crystal structure of poly[diaqua-{μ3-1-(3-carboxylatophenyl)-4-oxo-1,4-dihydropyridazine-3-carboxylato-κ4O,O′:O′′:O′′′′}manganese(II)] hydrate

- Crystal structure of N′-((1-hydroxycyclohexyl)(phenyl)methyl)-2-methoxybenzohydrazide methanol solvate, C22H28N2O4

- The cocrystal of caffeic acid — progesterone — water (1/2/1), C51H70O9

- Crystal structure of (((oxido(quinolin-6-yl)methoxy)triphenyl-λ5-stibanyl)oxy)(quinolin-7-yl)methanolate

- Crystal structure of [(E)-6′-(diethylamino)-2-(2-(((E)-pyren-1-ylmethylene)amino)ethyl)-4′-(2-((E)-1,3,3-trimethylindolin-2-ylidene)ethylidene)-1′,2′,3′,4′-tetrahydrospiro[isoindoline-1,9′-xanthen]-3-one]-methanol, solvate C57H56N4O3

- The crystal structure of 1-(acridin-9-yl)pyrrolidine-2,5-dione, C17H22N2O2

- Crystal structure of N-(4-acetylphenyl)-2-(6-methoxynaphthalen-2-yl)propanamide, C22H21NO3

- The crystal structure of 5,10,15,20-tetrakis(4-(1H-1,2,4-triazol-1-yl)phenyl)porphyrin, C52H34N16

- Crystal structure of hexacarbonyl-μ2-[phenylmethanedithiolato-κ4S:S,S′:S′]diiron (Fe–Fe) C13H6Fe2O6S2

- Crystal structure of diiodo-bis(1-((2-propyl-1H-benzo[d]imidazol-1-yl)methyl)-1H-benzo[d][1,2,3]triazole-κ1N)cadmium(II), C34H34CdI2N10

- Crystal structure of (E)-(3-(3-bromophenyl)acryloyl)ferrocene, C19H15BrFeO

- Crystal structure of catena-poly(μ2-6-chloropyridine-2-carboxylato-κ3N,O:O′)(6-chloropyridine-2-carboxylato-κ2O,N)copper(II), C12H6Cl2N2O4Cu

- Crystal structure of poly[diaqua-μ 3-(5-(3,5-dicarboxy-2,4,6-trimethylbenzyl)-2,4,6-trimethylisophthalato)-κ 6O,O′:O″,O‴:O‴′,O‴″) terbium(III)-monohydrate], C23H28TbO12

- Crystal structure of (E)-2-(((5-chloro-3-methyl-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)methylene)amino)-3′,6′-dihydroxyspiro[isoindoline-1,9′-xanthen]-3-one – ethanol (1/2), C35H33ClN4O6

- The crystal structure of 3-(5-amino-3-phenylisoxazol-4-yl)-4-chloro-3-hydroxyindolin-2-one, C17H12ClN3O3

- The crystal structure of dimethylammonium 4-[2-(4-fluorophenyl)-4, 5-diphenyl-1H-imidazol-1-yl]benzenesulfonate, C29H26FN3O3S

- Crystal structure of (R)-2-ammonio-3-((5-carboxypentyl)thio)propanoate

- Crystal structure of 4-cyclohexyl-5-(thiophen-2-yl)-2,4-dihydro-3H-1,2,4-triazole-3-thione, C12H15N3S2

- The crystal structure of 4,6-bis(dimethylamino)-2-fluoroisophthalonitrile, C12H13FN4

- Hydrogen bonding in the crystal structure of nicotin-1,1′-dium tetrabromidomanganate(II)

- The crystal structure of bis(2-bromobenzyl)(2-((2-oxybenzylidene)amino)-4-methylpentanoato-κ3N, O,O′)tin(IV), C27H27Br2NO3Sn

- Crystal structure of (E)-(3-(p-tolyl)acryloyl)ferrocene, C20H18FeO

- Crystal structure of (E)-7-fluoro-2-((5-(4-methylpiperazin-1-yl)pyridin-2-yl)methylene)-3,4-dihydronaphthalen-1(2H)-one, C21H22FN3O

- Crystal structure of (E)-7-methoxy-2-((5-(4-methylpiperazin-1-yl)pyridin-2-yl)methylene)-3,4-dihydronaphthalen-1(2H)-one, C22H25N3O2

- The crystal structure of poly(bis(μ2-1,3,5-tri(1H-imidazol-1-yl)benzene-κ2N:N′)-(μ2-2,3,5,6-tetrafluoroterephthalato-κ2O:O′)-manganese(II), C38H24F4N12O4Mn

- Crystal structure of (3,4-dimethoxybenzyl)triphenylphosphonium bromide ethanol solvate, C29H32BrO3P

- Crystal structure of tetraethylammonium hydrogencarbonate – (diaminomethylene)thiourea – water (2/1/3)

- Crystal structure of N, N-Dimethyl-N′-tosylformimidamide, C10H14N2O2S

- The crystal structure of ethyl 2-methyl-5-oxo-4-(2-methoxyphenyl)-1,4,5,6,7,8-hexahydroquinoline-3-carboxylate, C20H23N2O4

- Crystal structure of bis(μ2-1,5-bis[(E)-1-(2-hydroxyphenyl)ethylidene] thiocarbonohydrazide)-bis(dimethylformamide)-dizinc(II) dimethylformamide solvate, C40H46N10O6S2Zn2⋅C3H7NO

- Crystal structure of azido-κ1N{hydridotris(3-tert-butyl-5-methylpyrazol-1-yl)borato-κ3N,N′,N″}copper(II), C24H40BCuN9

- The crystal structure of fac-tricarbonyl(1,10-phenanthroline-κ2N,N′)-(azido-κ1N)rhenium(I), C15H8N5O3Re

- Crystal structure of 4-((triphenylphosphonio)methyl)pyridin-1-ium tetrachloridozincate(II), C24H22Cl4NPZn