Abstract

Breaking the symmetry between forward- and backward-propagating optical modes is of fundamental scientific interest and enables crucial functionalities, such as isolators, circulators, and duplex communication systems. Although there has been progress in achieving optical isolation on-chip, integrated broadband nonreciprocal signal processing functionalities that enable transmitting and receiving via the same low-loss planar waveguide, without altering the frequency or mode of the signal, remain elusive. Here, we demonstrate a nonreciprocal delay scheme based on the unidirectional transfer of optical data pulses to acoustic waves in a chip-based integration platform. We experimentally demonstrate that this scheme is not impacted by simultaneously counterpropagating optical signals. Furthermore, we achieve a bandwidth more than an order of magnitude broader than the intrinsic optoacoustic linewidth, linear operation for a wide range of signal powers, and importantly, show that this scheme is wavelength preserving and avoids complicated multimode structures.

1 Introduction

Reciprocity is a general concept in optics dictating that a transmission channel does not change, or is symmetric, under the interchange of source and receiver [1], [2], [3]. There are, however, different approaches to break this reciprocity, most commonly by utilizing magnetic materials [4], [5], [6]. The arguably most common devices based on breaking reciprocity are isolators utilizing magnetic materials. Isolators based on magnetic materials are passive components and have large bandwidth and rejection. Chip integration and material losses, however, are still major challenges despite the great progress made over the recent years.

Another way to achieve nonreciprocal transmission is based on temporal modulation [2], [7]. Although this active method requires some sort of pumping – electrical [8], optical [9], or acoustic [10] – it offers great potential as it does not rely on magnetic materials and hence is more suitable for chip integration with the additional advantage of being reconfigurable. Nonreciprocal elements, such as optical isolators and circulators are crucial building blocks, in particular, for integrated photonic circuits to protect the laser but also to route counterpropagating signals and mitigate back-reflections that can arise from boundaries between multiple elements or are simply caused by Rayleigh backscattering.

A powerful and versatile way to achieve nonreciprocal transmission in a small footprint can be realized by coupling light and mechanical degrees of freedom [11], [12]. This coupling between light and mechanical oscillations is greatly enhanced in resonant structures which lead to demonstrations of chip-scale optomechanical isolators and circulators for optical [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19] as well as microwave signals [20], [21], [22], [23].

Similarly, stimulated Brillouin scattering (SBS), i.e. the resonant coupling of optical waves with propagating acoustic waves in waveguides via optically induced forces is known to be nonreciprocal [9], [24]. The phase-matching condition ensures that only pump and probe waves which are counterpropagating (copropagating) couple to the acoustic wave which is mainly longitudinal for backward SBS (transverse for forward Brillouin scattering) [25]. As these acoustic waves carry momentum, Brillouin interactions can be used to induce indirect photonic transitions between different optical modes [9], [24], [26].

Numerous experiments have reported nonreciprocity exploiting Brillouin interactions, including demonstrations in photonic crystal fibers [9], silicon waveguides [27], and fiber-tip resonators [28], [29], [30]. Surprisingly, however, so far there was no demonstration of Brillouin-based nonreciprocal schemes harnessing backward SBS. In this approach, the optical wave can couple to a continuum of acoustic modes that provides enormous flexibility, which is particularly important for nonreciprocal signal processing schemes that go beyond providing pure signal isolation. Furthermore, large backward SBS gain can be achieved in small footprint planar integrated circuits [25].

Here, we show a nonreciprocal light storage scheme based on coherent Brillouin coupling of acoustic and optical modes to achieve nonreciprocal delay. We experimentally demonstrate that optical pulses that are traveling simultaneously in the opposite direction, with the same optical frequency and mode, are not impacted nor do they impact the storage process. We show that the bandwidth of the scheme can be broadened beyond the intrinsic acoustic linewidth – in this demonstration by more than one order of magnitude – which was generally thought to be a limiting factor of SBS-based nonreciprocal schemes. Furthermore, the scheme depends linearly on the input data pulse power in the observed range and does neither alter the frequency nor mode of the incoming data – all important requirements for practical nonreciprocal devices.

2 Results

The nonreciprocity is induced by an interaction between two counterpropagating optical modes – here we call them data ωdata and write/read ωw/r – with a traveling acoustic mode Ω. To enable efficient coupling from optical to acoustic waves, the optical write/read and the data pulses are separated by the frequency of the acoustic wave in the waveguide, known as the Brillouin frequency shift,

Brillouin interactions can be used to store optical data pulses as acoustic waves on a photonic chip [32]. The optical data pulses are frequency-upshifted from counterpropagating write and read pulses by precisely the Brillouin frequency shift Ω. Hence, the optical data pulses are first depleted by the write pulses and an acoustic wave is generated and are later retrieved using read pulses which deplete the acoustic wave.

This interaction has not only to fulfill energy conservation

That the Brillouin process is only phase-matched for data signals traveling in one direction becomes more evident when looking at the dispersion diagram shown in Figure 1a, where changing the direction of one optical mode leads to a phase mismatch Δq. As the interaction takes place over an elongated length given by either the length of the waveguide, for the case of continuous wave (CW) signals, or the length of the optical signal pulse, a small initial phase mismatch builds up to a large mismatch over that interaction length as it was shown for the case of Brillouin interactions that involve multiple optical wavelengths [33]. Even in the case of nanosecond (ns) and subnanosecond pulses, this length scale is in the order of several centimeters.

Basic principle and phase-matching diagram.

(a) Dispersion diagram for backward Brillouin scattering illustrating the phase-matching condition for data pulses propagating in opposite directions. (b) Optical data pulses that are coupled from the left side into the waveguide are converted to acoustic phonons and experience a delay. Optical data pulses that are coupled simultaneously from the opposite side in the waveguide do not experience any conversion and hence are not delayed.

How this strict phase-matching condition of the optoacoustic Brillouin interaction can be utilized to achieve unidirectional signal delays is shown in Figure 1b. Optical data pulses ωdata that propagate from the left through the waveguide are transferred to acoustic phonons via a Brillouin interaction induced by counterpropagating write pulses ωw and are subsequently retrieved using read pulses ωr [32], [34], [35], whereas optical pulses that travel in the opposite direction are neither effected by the write, the read pulses nor the acoustic wave that stores the original optical pulses ωdata. The phase-matching condition between the optical modes and the traveling acoustic wave ensures that there is no interaction, even for the extreme case when the counterpropagating optical pulses are in the same optical waveguide mode, at the same frequency and optical power.

Data pulses that are transferred to the acoustic domain accumulate a large delay because of the five orders of magnitude difference in velocity between the acoustic and optical waves. The accumulated delay of the optical signal can hence be approximated by the time difference between the writing and the retrieving operation. Thus, the delay of the optical signal can be continuously tuned within the acoustic lifetime of the acoustic phonon that is given by the material properties of the chalcogenide glass and is in the order of 10 ns [32].

Owing to the phase-matching condition of the Brillouin interaction, the coupling between optical and acoustic wave only occurs for a certain pair of optical write/read and data pulses. Optical data pulses that are simultaneously propagating through the waveguide from the opposite side are neither transferred to the acoustic wave by the write pulses, nor do they interact with the acoustic wave present in the waveguide and hence do also not influence the stored data pulses. The counterpropagating signals could be data pulses that are simultaneously transmitted/received in the opposite direction through the same waveguide or could simply originate from back-scattering in the photonic circuit.

2.1 Experimental setup

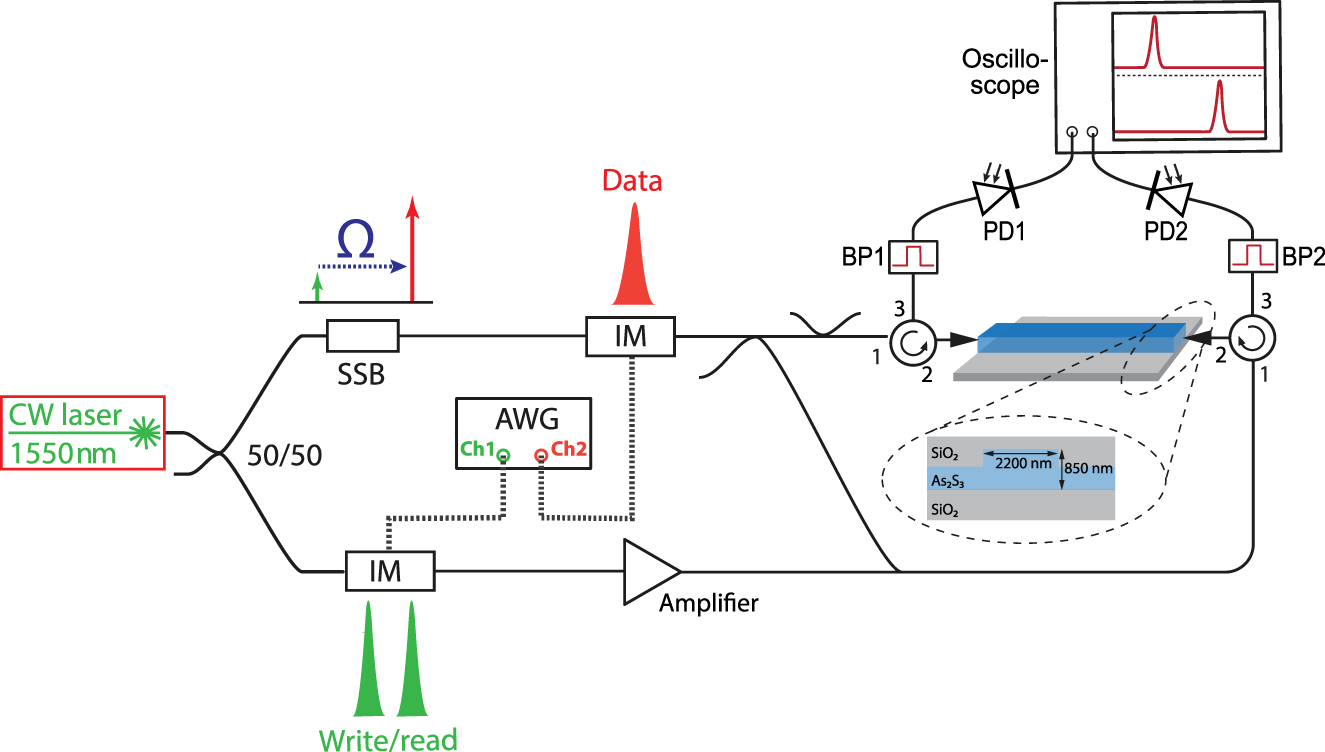

The simplified experimental setup is shown in Figure 2 (a detailed scheme and description can be found in Section 4). A CW distributed feedback laser is split into two paths, the data and the write/read path. The data signal is shifted by the Brillouin frequency shift Ω of the waveguide. Afterward, the CW signals in both arms are modulated into short pulses using a multichannel arbitrary waveform generator and electro-optic intensity modulators. The data signal is split using a 50/50 coupler. One part of the signal is combined with the write/read arm and coupled to the nonlinear chalcogenide waveguide. The other half passes through an additional 50/50 coupler, to ensure that the path length of both data signals as well as their optical power is the same in both arms, and is coupled to the chalcogenide chip from the opposite side. On both sides of the chip circulators are used to separate input and output. Two narrowband filters (bandwidth ≈ 3 GHz) are used to separate the data signal from the pump signal and fast photodetectors (bandwidth > 10 GHz) and a fast oscilloscope (bandwidth > 10 GHz) are used to detect the data pulses. A cross-section of the chalcogenide waveguides is shown in the inset of Figure 2. A rib structure with a cross-section of 2200 × 850 nm2 is used to reduce losses caused by sidewall roughness. The chalcogenide glass is surrounded by silica glass to ensure confinement of the optical as well as the acoustic mode [36]. For details on the fabrication of the acousto-optic waveguides, see Section 4. The simulated dispersion of the waveguide for both optical modes (forward and backward) is around −200 ps/nm/km. Although it is larger than in standard single-mode fiber, for the length of the chip (22 cm) and the bandwidth of the pulses (around 4 pm), the signal distortion from dispersion is negligible.

Schematic experimental setup. Continuous wave (CW) laser, continuous wave distributed feedback (DFB) laser; 50/50 fiber coupler; SSB, single-sideband modulator; IM, intensity modulator; AWG, multichannel arbitrary waveform generator; Amplifier, erbium-doped fiber amplifier; BP, bandpass filter; PD, photodetector. Inset: cross-section of the chalcogenide rib waveguide embedded in silica.

2.2 Nonreciprocal Brillouin light storage

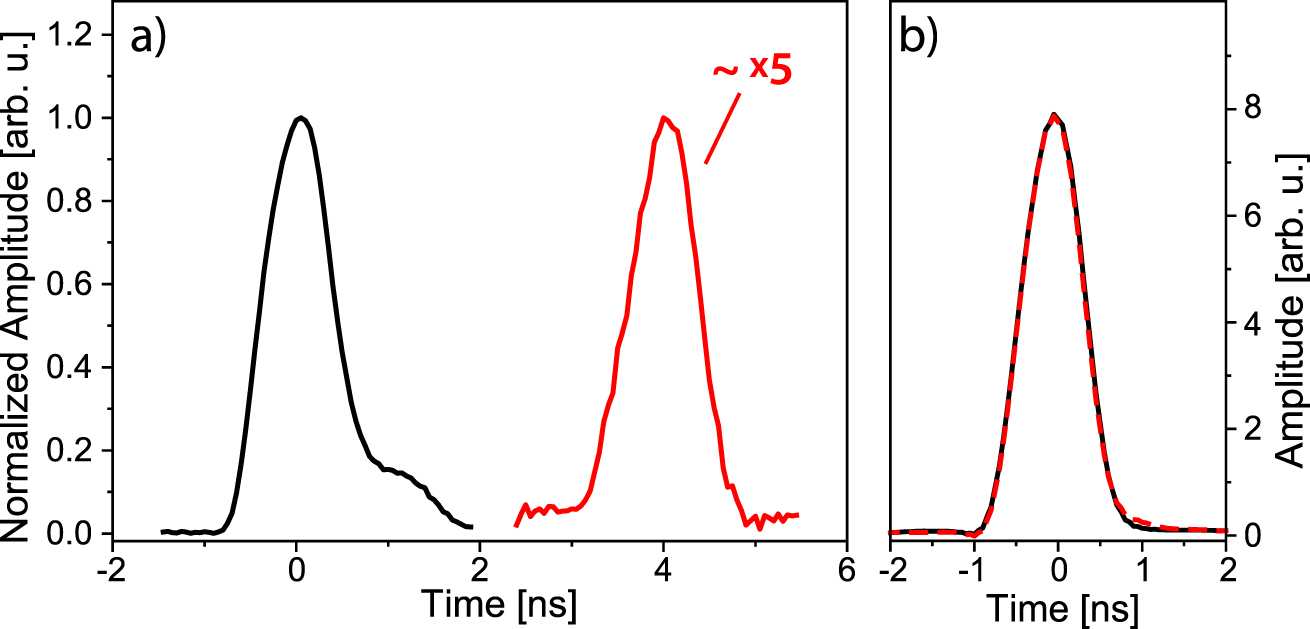

Figure 3a shows the transfer of an optical data pulse ωdata to an acoustic wave by a counterpropagating write pulse ωw (black curve; full-width half-maximum ≈ 1 ns). The depleted optical signal is shown in red (Figure 3a). Around 90% of data pulse depletion could be achieved, whereas a simultaneously counterpropagating data pulse (copropagating to the write pulses) is not impacted by the acoustic wave generated in the depletion process (inset Figure 3a). The black curve in the inset shows optical data pulses transmitted in the counterpropagating direction, whereas there is no data transferred to the acoustic wave. The red dashed curve in the inset of Figure 3a shows the counterpropagating optical data pulses while the data traveling in the opposite direction is depleted and transferred to a traveling acoustic wave. Both curves perfectly overlap. In the current experimental implementation, the depletion efficiency of 90% was mainly limited by power constraints and can in principle reach almost full conversion of the optical pulse to the acoustic wave. Figure 3b shows the fast Fourier transform (FFT) of the optical input data pulses demonstrating that the bandwidth of the optical data pulses that can be successfully depleted and transferred to the acoustic domain can greatly exceed the intrinsic Brillouin linewidth of 30 MHz. The dashed lines in Figure 3b indicate the full-width half-maximum of the FFT of the data pulses.

Nonreciprocal pulse depletion.

(a) Conversion of an optical data pulse (black curve) to acoustic phonons (red curve) while a simultaneously counterpropagating data pulse is not impacted (black and dashed red curve in inset). (b) Fast Fourier transform (FFT) of the input data pulse.

This extension of the bandwidth by more than one order of magnitude beyond the intrinsic acoustic linewidth is enabled by the ultrahigh Brillouin gain provided in chalcogenide waveguides which is about two orders of magnitude larger than in standard silica single-mode fiber. The strength of the interaction is usually measured in terms of Brillouin gain G which gives the amplification of the Stokes wave for a given pump power P and is proportional to ∝ exp(g LeffP), with

The broad bandwidth is one main advantage of the resonator-free waveguide-based Brillouin approach. Although the intrinsic linewidth of the optoacoustic interaction is given by the phonon lifetime for a single frequency CW optical pump the Brillouin response can be broadened by using a broad bandwidth optical pump where the bandwidth of the Brillouin response is then given by the bandwidth of the optical pump itself. The intrinsic Brillouin gain is in this case distributed over the bandwidth and hence the absolute maximum Brillouin gain is reduced accordingly for a given input power.

After demonstrating the nonreciprocal depletion of optical data pulses, we now show that we can retrieve the data back from the acoustic to the optical domain, even in the presence of counterpropagating pulses, and hence unidirectionally delay optical signals relative to the regular transit time of the waveguide. Figure 4a shows experimental measurements of a 1 ns long optical data pulse that is delayed by 4 ns when propagating in one direction in the waveguide, whereas an optical data pulse simultaneously propagating in the opposite direction with the same optical frequency and optical mode is not interacting with the Brillouin storage process or the acoustic wave present in the waveguide (Figure 4). The transit time of the chip is around 1.8 ns and hence our measured delay would equate to an increase in the group index by a factor of about 2.2. As a proof-of-principle demonstration, we only show a pulse delay of 4 ns; however, we note that the delay is given by the arrival time difference between the write and the read pulses and hence can continuously be tuned. As the phonon exponentially decays as

Nonreciprocal light storage.

(a) Optical data pulses (black trace) propagating in one direction are delayed by 4 ns (red trace), whereas (b) simultaneously counterpropagating data pulses are not impacted (black trace shows transmitted data without delay applied to the counterpropagating signals, red dotted trace shows transmitted data while counterpropagating data are stored). Note that the readout efficiency of the pulses presented in (a) is around 20% and the data pulses are normalized to visualize the pulse shape before and after the storage process.

Conversely, in the here-demonstrated delay scheme, the pulse shape is maintained (Figure 4a). The input data pulse and the delayed data pulse in Figure 4a are normalized to visually emphasize that point and show the similarity in the pulse shape as it is a common practice for fiber-based optical pulse delay techniques [35], [40], [41], [42], [43], [44]. The readout efficiency of this measurement was around 20% after a delay of 4 ns. Here, the efficiency is slightly below the record of 32% after a delay time of 3.5 ns reported previously [32], which can be accounted to overall power limitations of the experimental setup due to simultaneously counterpropagating signals.

While the data pulses are stored and delayed in one direction, simultaneously counterpropagating data pulses are not delayed (Figure 4b). The black curve in Figure 4b shows an optical pulse when there is no delay applied to the data that travels in the opposite direction, whereas the dashed red curve shows the optical pulse for the case when the counterpropagating channel is delayed via coherent transfer from optical to acoustic and back to the optical domain. Here, the data pulses are not normalized to emphasize that there is neither a change in amplitude nor shape of the pulses. The counterpropagating data pulses do not interact with the acoustic mode present in the waveguide from the delay process of the data pulses propagating in the opposite direction nor do they distort the storage process of these pulses. Hence, we show that the nonreciprocal pulse storage scheme enables full duplex signal processing. It also shows that potential back-reflections which can occur in complex integrated circuits that consist of many discreet components are not distorting the delay process.

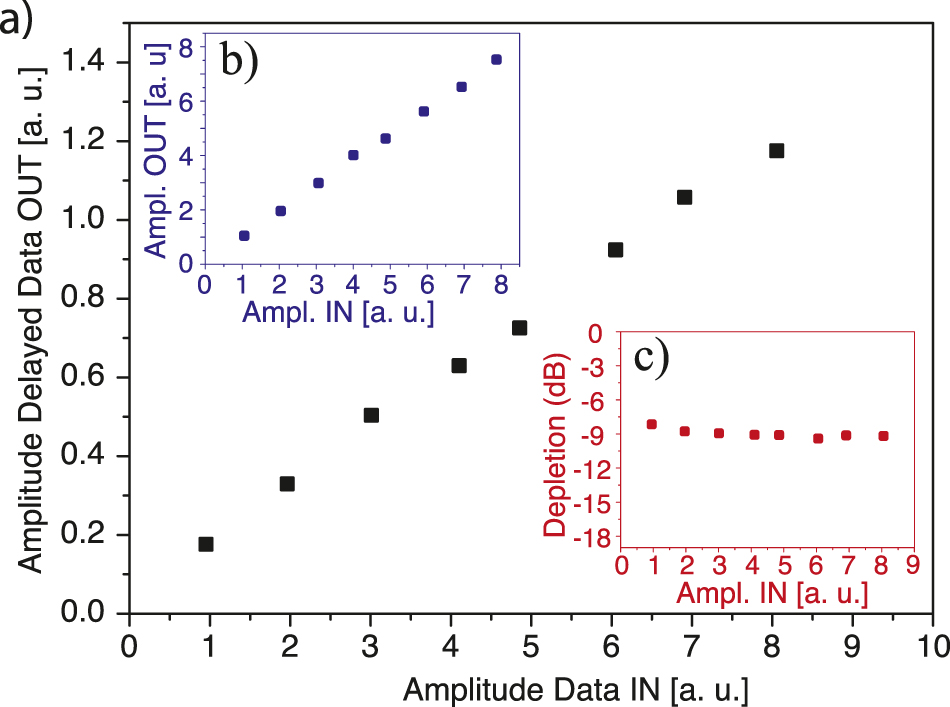

A crucial metric for nonreciprocal devices in general, which is particularly important for optical signal processing applications, is the linearity of the scheme. The linearity ensures that information encoded in the amplitude is maintained during the signal processing operation. Figure 5 shows that the Brillouin-based nonreciprocal delay scheme is linear over a wide range. The coupled power of the input data pulses in Figure 5 is varied by an order of magnitude from −10 to −20 dBm average optical power and we observe a linear relationship between input and output amplitude. We confirm that the same is true for the counterpropagating data channel (Figure 5b). The second inset, Figure 5c, shows that the depletion of the original data pulses which are transferred to the acoustic wave is approximately constant in the measured data power range.

Linearity of nonreciprocal light storage.

(a) Linear amplitude response of the delayed optical data pulses. Inset (b) shows the linearity of the counterpropagating data pulses, whereas inset (c) shows the depletion of the data pulses for different input amplitude levels.

3 Conclusion and outlook

We showed a nonreciprocal delay scheme based on the coherent interaction of photons with traveling acoustic phonons. The phase-matching underlying this process ensures that only optical data pulses traveling in a distinct direction are delayed. We showed that the bandwidth of this scheme is not limited to the intrinsic linewidth of the optoacoustic interaction, but can, in fact, be much broader approaching the GHz regime. Furthermore, we demonstrated that the scheme depends linearly on the input power and does neither convert the optical mode nor the wavelength of the signal. Hence, it opens a pathway to full duplex signal processing architectures that can greatly reduce size, weight, and power requirements. The delay time is continuously tunable as it is given by the difference in the arrival time of the readout pulse with respect to the write pulse within the phonon lifetime [32]. Recently, however, it was proposed and experimentally shown that the storage time can be extended by refreshing the acoustic phonon with optical pulses [45] overcoming said limitation.

Our demonstration of delaying an optical signal while another optical signal at the same frequency is counterpropagating shows the immunity of the here-presented delay scheme to detrimental back-reflections common in complex integrated photonic circuits that are composed of a multitude of optical elements. In the context of phased array antennas and beam steering elements, inducing nonreciprocal delays could enable new ways of separating transmitted and received signals.

4 Materials and methods

4.1 Experimental setup for nonreciprocal light storage

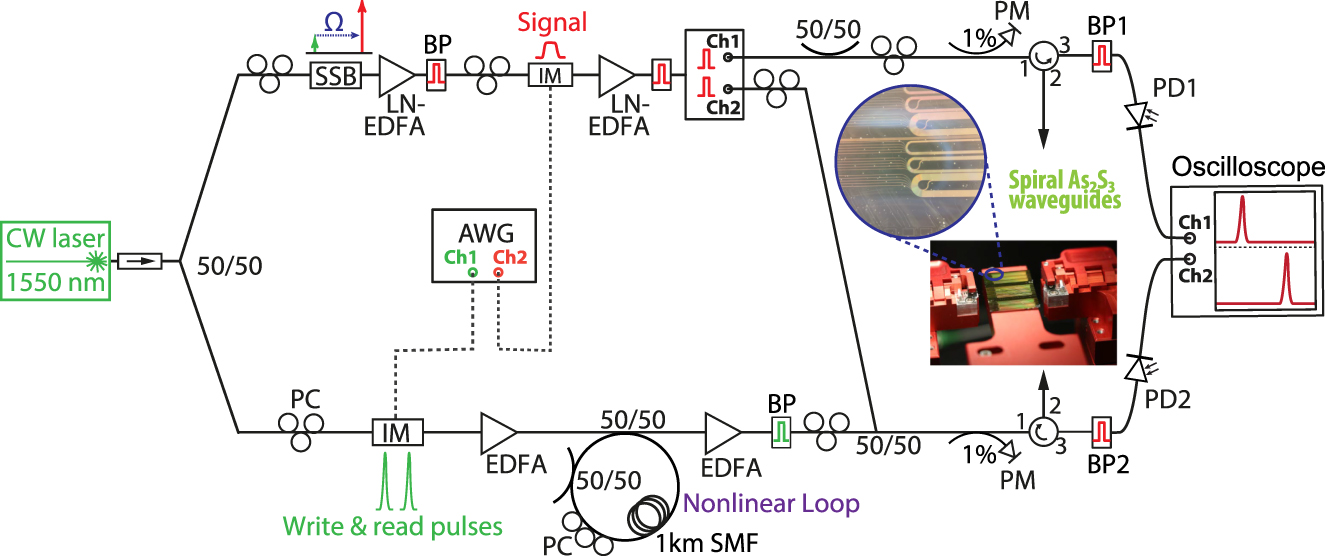

A layout of the experimental setup is shown in Figure 6.

Experimental setup.

Continuous wave (CW) laser, continuous-wave laser; 50/50: 50/50 optical fiber coupler; PC, polarization controller; SSB, single-sideband modulator; EDFA, erbium-doped fiber amplifier; LN-EDFA, low-noise EDFA; IM, intensity modulator; BP, bandpass filter; AWG, arbitrary waveform generator; CH 1/2, Channel 1/2; SMF, standard single-mode fiber; PM, power meter; PD, photodetector.

As a laser source, we use a narrow-linewidth distributed feedback laser (TerraXion NLL) with a wavelength of around 1550 nm. The laser signal is divided into two arms, the data and the write/read arm. The data signal is up-shifted in frequency by the Brillouin frequency shift Ω via a single-sideband modulator. A single laser source is used to avoid relative drift of the data and the write/read arm. Two intensity modulators connected to a multichannel arbitrary waveform generator are used to chop the CW laser signals in both arms into a pulse stream. The write/read pulses are amplified via an erbium-doped fiber amplifier (EDFA) and afterward pass through a nonlinear fiber loop. The nonlinear fiber loop only transmits the write/read pulses and suppresses any background present from the laser or amplifier between the pulses as only the pulses have a high enough intensity to induce a nonlinear phase shift in the fiber loop. Hence, only the pulses are transmitted and the low-intensity background is reflected by the loop. A second EDFA after the loop boosts the signal to peak powers of several Watts. To minimize the effect of white noise, bandpass filters with a bandwidth of around 0.5 nm are implemented after every amplification step by the EDFAs. The one-laser setup, the low-noise EDFA combined with filtering, and the nonlinear loop are all used in the setup to maximize the signal-to-noise ratio that ensures the highest efficiency of the storage process with the least amount of distortions. The write and read pulses are coupled into the photonic chip using lensed fibers and the average coupled on-chip power was around 7 dBm.

The data signal is split with a 50/50 coupler and coupled from both sides into the photonic chip with an average power of around −10 dBm. From one side, the write/read pulses are combined with the data pulses and coupled via the same lensed fiber into the chip. Additional 50/50 couplers are used in the data path to make sure the data pulses and the write/read pulses overlap in the middle of the waveguide. Circulators are used on both sides of the chip to route the transmitted data signal to a two-channel fast oscilloscope. Two narrowband filters with a bandwidth of 3 GHz are used before the fast photodetectors (bandwidth 12 GHz) to filter residual write/read pulses.

4.2 Storage medium

The storage medium for the nonreciprocal light storage is a chalcogenide rib waveguide [37], [46]. The chalcogenide As2S3 thin film of around 850 nm is deposited on a thermal oxide silicon wafer with a variation of the film thickness below 5% [47]. Photolithography is used to pattern the waveguide structures which are etched into the thin film using inductively coupled plasma dry etching with a mixture of CHF3, O2, and Ar. The dimensions of the rib structure are 850 nm by 2.2 μm with a 50% etch depth and an overall length of 22 cm. The waveguide is arranged in a spiral to reduce the overall footprint to around 16 mm2. The bend radius of the spiral is around 200 μm to ensure that there is no additional bending loss introduced for the fundamental optical mode as well as the acoustic mode.

The chalcogenide glass As2S3 is sandwiched between a silica substrate and a silica top-cladding to ensure guiding of the acoustic as well as the optical mode [36]. The difference in refractive index of silica n ≈ 1.4 and the chalcogenide rib waveguides n ≈ 2.4 guarantees tight confinement of the optical mode, whereas the difference in sound velocity of around 3400 m/s prevents leakage of the acoustic mode into the substrate or cladding which enables strong overlap between the two respective modes. The silica top-cladding is deposited using sputtering.

Light is coupled in and out of the chip using lensed fibers with a roughly 2 μm focus spot size. The coupling loss per facet is around 4 dB. The polarization is adjusted so light is coupled into the fundamental TE mode of the waveguide which is the mode with the lowest loss.

Funding source: Australian Research Council (ARC)

Award Identifier / Grant number: FL120100029

Funding source: Center of Excellence CUDOS

Award Identifier / Grant number: CE110001018

Funding source: ARC 2020 Discovery Project

Award Identifier / Grant number: DP200101893

Funding source: ARC Linkage grant

Award Identifier / Grant number: LP170100112

Funding source: U.S. Office of Naval Research Global (ONRG)

Award Identifier / Grant number: N62909-18-1-2013

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Australian Research Council (ARC) through Laureate Fellowship (FL120100029), Center of Excellence CUDOS (CE110001018), ARC 2020 Discovery Project (DP200101893), ARC Linkage grant (LP170100112), and U.S. Office of Naval Research Global (ONRG) (N62909-18-1-2013). The authors acknowledge the support of the ANFF ACT.

Author contributions: All the authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this submitted manuscript and approved submission.

Research funding: This work was supported by the Australian Research Council (ARC) through Laureate Fellowship (FL120100029), Center of Excellence CUDOS (CE110001018), ARC 2020 Discovery Project (DP200101893), ARC Linkage grant (LP170100112), and U.S. Office of Naval Research Global (ONRG) (N62909-18-1-2013).

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare no conflicts of interest regarding this article.

References

[1] D. Jalas, A. Petrov, M. Eich, et al., “What is – and what is not – an optical isolator,” Nat. Photonics, vol. 7, pp. 579–582, 2013. https://doi.org/10.1038/nphoton.2013.185.Search in Google Scholar

[2] D. L. Sounas and A. Alù, “Non-reciprocal photonics based on time modulation,” Nat. Photonics, vol. 11, pp. 774–783, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41566-017-0051-x.Search in Google Scholar

[3] C. Caloz, A. Andrea, S. Tretyakov, D. Sounas, K. Achouri, and Z. L. Deck-Léger, “Electromagnetic nonreciprocity,” Phys. Rev. Appl., vol. 10, p. 1, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevapplied.10.047001.Search in Google Scholar

[4] Y. Shoji, T. Mizumoto, H. Yokoi, I. Wei Hsieh, and R. M. Osgood, “Magneto-optical isolator with silicon waveguides fabricated by direct bonding,” Appl. Phys. Lett., vol. 92, pp. 2–5, 2008. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.2884855.Search in Google Scholar

[5] L. Bi, J. Hu, P. Jiang, et al., “On-chip optical isolation in monolithically integrated non-reciprocal optical resonators,” Nat. Photonics, vol. 5, pp. 758–762, 2011. https://doi.org/10.1038/nphoton.2011.270.Search in Google Scholar

[6] D. Huang, P. Pintus, C. Zhang, et al., “Dynamically reconfigurable integrated optical circulators,” Optica, vol. 4, p. 23, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1364/optica.4.000023.Search in Google Scholar

[7] Z. Yu and S. Fan, “Complete optical isolation created by indirect interband photonic transitions,” Nat. Photonics, vol. 3, pp. 91–94, 2009. https://doi.org/10.1038/nphoton.2008.273.Search in Google Scholar

[8] H. Lira, Z. Yu, S. Fan, and M. Lipson, “Electrically driven nonreciprocity induced by interband photonic transition on a silicon chip,” Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 109, pp. 1–5, 2012. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevlett.109.033901.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] M. S. Kang, A. Butsch, and P. S. J. Russell, “Reconfigurable light-driven opto-acoustic isolators in photonic crystal fibre,” Nat. Photonics, vol. 5, pp. 549–553, 2011. https://doi.org/10.1038/nphoton.2011.180.Search in Google Scholar

[10] D. B. Sohn, S. Kim, and G. Bahl, “Time-reversal symmetry breaking with acoustic pumping of nanophotonic circuits,” Nat. Photonics, vol. 12, pp. 91–97, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41566-017-0075-2.Search in Google Scholar

[11] E. Verhagen and A. Alù, “Optomechanical nonreciprocity,” Nat. Phys., vol. 13, pp. 922–924, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1038/nphys4283.Search in Google Scholar

[12] M. Ali Miri, F. Ruesink, E. Verhagen, and A. Alù, “Optical nonreciprocity based on optomechanical coupling,” Phys. Rev. Appl., vol. 7, pp. 1–20, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevapplied.7.064014.Search in Google Scholar

[13] S. Manipatruni, J. T. Robinson, and M. Lipson, “Optical nonreciprocity in optomechanical structures,” Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 102, p. 213903, 2009. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevlett.102.213903.Search in Google Scholar

[14] M. Hafezi and P. Rabl, “Optomechanically induced non-reciprocity in microring resonators,” Optic Express, vol. 20, p. 7672, 2012. https://doi.org/10.1364/oe.20.007672.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[15] X. W. Xu and Y. Li, “Optical nonreciprocity and optomechanical circulator in three-mode optomechanical systems,” Phys. Rev. A Atom. Mol. Opt. Phys., vol. 91, pp. 1–8, 2015. https://doi.org/10.1103/physreva.91.053854.Search in Google Scholar

[16] F. Ruesink, M.-A. Miri, A. Alù, and E. Verhagen, “Nonreciprocity and magnetic-free isolation based on optomechanical interactions,” Nat. Commun., vol. 7, p. 13662, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms13662.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[17] Z. Shen, Y.-L. Zhang, Y. Chen, et al., “Experimental realization of optomechanically induced non-reciprocity,” Nat. Photonics, vol. 10, pp. 657–661, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1038/nphoton.2016.161.Search in Google Scholar

[18] K. Fang, J. Luo, A. Metelmann, et al., “Generalized non-reciprocity in an optomechanical circuit via synthetic magnetism and reservoir engineering,” Nat. Phys., vol. 13, pp. 465–471, 2017, https://doi.org/10.1038/nphys4009.Search in Google Scholar

[19] Z. Shen, Y.-L. Zhang, Y. Chen, et al., “Reconfigurable optomechanical circulator and directional amplifier,” Nat. Commun., vol. 9, p. 1797, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-04187-8.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[20] N. A. Estep, D. L. Sounas, and A. Alù, “Magnetless microwave circulators based on spatiotemporally modulated rings of coupled resonators,” IEEE Trans. Microw. Theor. Tech., vol. 64, pp. 502–518, 2016, https://doi.org/10.1109/TMTT.2015.2511737.Search in Google Scholar

[21] G. A. Peterson, F. Lecocq, K. Cicak, R. W. Simmonds, J. Aumentado, and J. D. Teufel, “Demonstration of efficient nonreciprocity in a microwave optomechanical circuit,” Phys. Rev. X, vol. 7, p. 031001, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevx.7.031001.Search in Google Scholar

[22] S. Barzanjeh, M. Wulf, M. Peruzzo, et al., “Mechanical on-chip microwave circulator,” Nat. Commun., vol. 8, p. 953, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-017-01304-x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[23] N. R. Bernier, L. D. Tóth, A. Koottandavida, et al., “Nonreciprocal reconfigurable microwave optomechanical circuit,” Nat. Commun., vol. 8, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-017-00447-1.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[24] X. Huang and S. Fan, “Complete all-optical silica fiber isolator via stimulated Brillouin scattering,” J. Lightwave Technol., vol. 29, pp. 2267–2275, 2011. https://doi.org/10.1109/jlt.2011.2158886.Search in Google Scholar

[25] B. J. Eggleton, C. G. Poulton, P. T. Rakich, M. J. Steel, and G. Bahl, “Brillouin integrated photonics,” Nat. Photonics, vol. 13, pp. 664–677, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41566-019-0498-z.Search in Google Scholar

[26] C. G. Poulton, R. Pant, A. Byrnes, S. Fan, M. J. Steel, and B. J. Eggleton, “Design for broadband on-chip isolator using stimulated Brillouin scattering in dispersion-engineered chalcogenide waveguides,” Opt. Express, vol. 20, p. 21235, 2012. https://doi.org/10.1364/oe.20.021235.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[27] E. A. Kittlaus, N. T. Otterstrom, P. Kharel, S. Gertler, and P. T. Rakich, “Non-reciprocal interband Brillouin modulation,” Nat. Photonics, vol. 12, pp. 613–620, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41566-018-0254-9.Search in Google Scholar

[28] J. H. Kim, M. C. Kuzyk, K. Han, H. Wang, and G. Bahl, “Non-reciprocal Brillouin scattering induced transparency,” Nat. Phys., vol. 11, pp. 275–280, 2015. https://doi.org/10.1038/nphys3236.Search in Google Scholar

[29] C.-H. Dong, Z. Shen, C.-L. Zou, Y.-L. Zhang, W. Fu, and G.-C. Guo, “Brillouin-scattering-induced transparency and non-reciprocal light storage,” Nat. Commun., vol. 6, p. 6193, 2015. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms7193.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[30] J. H. Kim, S. Kim, and G. Bahl, “Complete linear optical isolation at the microscale with ultralow loss,” Sci. Rep., vol. 7, pp. 1–9, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-01494-w.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[31] R. W. Boyd, Nonlinear Optics, Acad. Press, 2003.Search in Google Scholar

[32] M. Merklein, B. Stiller, K. Vu, S. J. Madden, and B. J. Eggleton, “A chip-integrated coherent photonic–phononic memory,” Nat. Commun., vol. 8, p. 574, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-017-00717-y.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[33] B. Stiller, M. Merklein, K. Vu, et al., “Cross talk-free coherent multi-wavelength Brillouin interaction,” APL Photonics, vol. 4, p. 040802, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.5087180.Search in Google Scholar

[34] Z. Zhu, D. J. Gauthier, and R. W. Boyd, “Stored light in an optical fiber via stimulated Brillouin scattering,” Science, vol. 318, pp. 1748–50, 2007. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1149066.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[35] M. Merklein, B. Stiller, and B. J. Eggleton, “Brillouin-based light storage and delay techniques,” J. Opt., vol. 20, p. 083003, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1088/2040-8986/aad081.Search in Google Scholar

[36] C. G. Poulton, R. Pant, and B. J. Eggleton, “Acoustic confinement and stimulated Brillouin scattering in integrated optical waveguides,” J. Opt. Soc. Am. B, vol. 30, pp. 2657–2664, 2013. https://doi.org/10.1364/josab.30.002657.Search in Google Scholar

[37] R. Pant, C. G. Poulton, D.-Y. Choi, et al., “On-chip stimulated Brillouin scattering,” Opt. Express, vol. 19, pp. 8285–8290, 2011. https://doi.org/10.1364/oe.19.008285.Search in Google Scholar

[38] V. Fiore, Y. Yang, M. C. Kuzyk, R. Barbour, L. Tian, and H. Wang, “Storing optical information as a mechanical excitation in a silica optomechanical resonator,” Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 107, pp. 1–5, 2011. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevlett.107.133601.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[39] V. Fiore, C. Dong, M. C. Kuzyk, and H. Wang, “Optomechanical light storage in a silica microresonator,” Phys. Rev., vol. 87, p. 023812, 2013. https://doi.org/10.1103/physreva.87.023812.Search in Google Scholar

[40] Y. Okawachi, M. Bigelow, J. Sharping, et al., “Tunable all-optical delays via Brillouin slow light in an optical fiber,” Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 94, p. 153902, 2005. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevlett.94.153902.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[41] K. Y. Song, M. Herráez, and L. Thévenaz, “Observation of pulse delaying and advancement in optical fibers using stimulated Brillouin scattering,” Opt. Express, vol. 13, pp. 82–88, 2005. https://doi.org/10.1364/opex.13.000082.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[42] K. Y. Song, K. Lee, and S. B. Lee, “Tunable optical delays based on Brillouin dynamic grating in optical fibers,” Opt Express, vol. 17, pp. 10344–9, 2009. https://doi.org/10.1364/oe.17.010344.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[43] S. Preussler, K. Jamshidi, A. Wiatrek, R. Henker, C.-A. Bunge, and T. Schneider, “Quasi-light-storage based on time-frequency coherence,” Opt Express, vol. 17, pp. 15790–15798, 2009. https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.17.015790.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[44] S. Chin and L. Thévenaz, “Tunable photonic delay lines in optical fibers,” Laser Photonics Rev., vol. 6, pp. 724–738, 2012. https://doi.org/10.1002/lpor.201100038.Search in Google Scholar

[45] B. Stiller, M. Merklein, C. Wolff, et al., “Coherently refreshing hypersonic phonons for light storage,” Optica, vol. 7, p. 492, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1364/optica.386535.Search in Google Scholar

[46] S. J. Madden, D.-Y. Choi, D. A. Bulla, et al., “Long, low loss etched As(2)S(3) chalcogenide waveguides for all-optical signal regeneration,” Opt. Express, vol. 15, pp. 14414–14421, 2007. https://doi.org/10.1364/oe.15.014414.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[47] A. Zarifi, B. Stiller, M. Merklein, et al., “Highly localized distributed Brillouin scattering response in a photonic integrated circuit,” APL Photonics, vol. 3, p. 036101, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.5000108.Search in Google Scholar

© 2020 Moritz Merklein et al., published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Editorial

- Editorial

- Optoelectronics and Integrated Photonics

- Disorder effects in nitride semiconductors: impact on fundamental and device properties

- Ultralow threshold blue quantum dot lasers: what’s the true recipe for success?

- Waiting for Act 2: what lies beyond organic light-emitting diode (OLED) displays for organic electronics?

- Waveguide combiners for mixed reality headsets: a nanophotonics design perspective

- On-chip broadband nonreciprocal light storage

- High-Q nanophotonics: sculpting wavefronts with slow light

- Thermoelectric graphene photodetectors with sub-nanosecond response times at terahertz frequencies

- High-performance integrated graphene electro-optic modulator at cryogenic temperature

- Asymmetric photoelectric effect: Auger-assisted hot hole photocurrents in transition metal dichalcogenides

- Seeing the light in energy use

- Lasers, Active optical devices and Spectroscopy

- A high-repetition rate attosecond light source for time-resolved coincidence spectroscopy

- Fast laser speckle suppression with an intracavity diffuser

- Active optics with silk

- Nanolaser arrays: toward application-driven dense integration

- Two-dimensional spectroscopy on a THz quantum cascade structure

- Homogeneous quantum cascade lasers operating as terahertz frequency combs over their entire operational regime

- Toward new frontiers for terahertz quantum cascade laser frequency combs

- Soliton dynamics of ring quantum cascade lasers with injected signal

- Fiber Optics and Optical Communications

- Propagation stability in optical fibers: role of path memory and angular momentum

- Perspective on using multiple orbital-angular-momentum beams for enhanced capacity in free-space optical communication links

- Biomedical Photonics

- A fiber optic–nanophotonic approach to the detection of antibodies and viral particles of COVID-19

- Plasmonic control of drug release efficiency in agarose gel loaded with gold nanoparticle assemblies

- Metasurfaces for biomedical applications: imaging and sensing from a nanophotonics perspective

- Hyperbolic dispersion metasurfaces for molecular biosensing

- Fundamentals of Optics

- A Tutorial on the Classical Theories of Electromagnetic Scattering and Diffraction

- Reflectionless excitation of arbitrary photonic structures: a general theory

- Optimization Methods

- Multiobjective and categorical global optimization of photonic structures based on ResNet generative neural networks

- Machine learning–assisted global optimization of photonic devices

- Artificial neural networks for inverse design of resonant nanophotonic components with oscillatory loss landscapes

- Adjoint-optimized nanoscale light extractor for nitrogen-vacancy centers in diamond

- Topological Photonics

- Non-Hermitian and topological photonics: optics at an exceptional point

- Topological photonics: Where do we go from here?

- Topological nanophotonics for photoluminescence control

- Anomalous Anderson localization behavior in gain-loss balanced non-Hermitian systems

- Quantum computing, Quantum Optics, and QED

- Quantum computing and simulation

- NIST-certified secure key generation via deep learning of physical unclonable functions in silica aerogels

- Thomas–Reiche–Kuhn (TRK) sum rule for interacting photons

- Macroscopic QED for quantum nanophotonics: emitter-centered modes as a minimal basis for multiemitter problems

- Generation and dynamics of entangled fermion–photon–phonon states in nanocavities

- Polaritonic Tamm states induced by cavity photons

- Recent progress in engineering the Casimir effect – applications to nanophotonics, nanomechanics, and chemistry

- Enhancement of rotational vacuum friction by surface photon tunneling

- Plasmonics and Polaritonics

- Shrinking the surface plasmon

- Polariton panorama

- Scattering of a single plasmon polariton by multiple atoms for in-plane control of light

- A metasurface-based diamond frequency converter using plasmonic nanogap resonators

- Selective excitation of individual nanoantennas by pure spectral phase control in the ultrafast coherent regime

- Semiconductor quantum plasmons for high frequency thermal emission

- Origin of dispersive line shapes in plasmon-enhanced stimulated Raman scattering microscopy

- Epitaxial aluminum plasmonics covering full visible spectrum

- Metaoptics

- Metamaterials with high degrees of freedom: space, time, and more

- The road to atomically thin metasurface optics

- Active nonlocal metasurfaces

- Giant midinfrared nonlinearity based on multiple quantum well polaritonic metasurfaces

- Near-field plates and the near zone of metasurfaces

- High-efficiency metadevices for bifunctional generations of vectorial optical fields

- Printing polarization and phase at the optical diffraction limit: near- and far-field optical encryption

- Optical response of jammed rectangular nanostructures

- Dynamic phase-change metafilm absorber for strong designer modulation of visible light

- Arbitrary polarization conversion for pure vortex generation with a single metasurface

- Enhanced harmonic generation in gases using an all-dielectric metasurface

- Monolithic metasurface spatial differentiator enabled by asymmetric photonic spin-orbit interactions

Articles in the same Issue

- Editorial

- Editorial

- Optoelectronics and Integrated Photonics

- Disorder effects in nitride semiconductors: impact on fundamental and device properties

- Ultralow threshold blue quantum dot lasers: what’s the true recipe for success?

- Waiting for Act 2: what lies beyond organic light-emitting diode (OLED) displays for organic electronics?

- Waveguide combiners for mixed reality headsets: a nanophotonics design perspective

- On-chip broadband nonreciprocal light storage

- High-Q nanophotonics: sculpting wavefronts with slow light

- Thermoelectric graphene photodetectors with sub-nanosecond response times at terahertz frequencies

- High-performance integrated graphene electro-optic modulator at cryogenic temperature

- Asymmetric photoelectric effect: Auger-assisted hot hole photocurrents in transition metal dichalcogenides

- Seeing the light in energy use

- Lasers, Active optical devices and Spectroscopy

- A high-repetition rate attosecond light source for time-resolved coincidence spectroscopy

- Fast laser speckle suppression with an intracavity diffuser

- Active optics with silk

- Nanolaser arrays: toward application-driven dense integration

- Two-dimensional spectroscopy on a THz quantum cascade structure

- Homogeneous quantum cascade lasers operating as terahertz frequency combs over their entire operational regime

- Toward new frontiers for terahertz quantum cascade laser frequency combs

- Soliton dynamics of ring quantum cascade lasers with injected signal

- Fiber Optics and Optical Communications

- Propagation stability in optical fibers: role of path memory and angular momentum

- Perspective on using multiple orbital-angular-momentum beams for enhanced capacity in free-space optical communication links

- Biomedical Photonics

- A fiber optic–nanophotonic approach to the detection of antibodies and viral particles of COVID-19

- Plasmonic control of drug release efficiency in agarose gel loaded with gold nanoparticle assemblies

- Metasurfaces for biomedical applications: imaging and sensing from a nanophotonics perspective

- Hyperbolic dispersion metasurfaces for molecular biosensing

- Fundamentals of Optics

- A Tutorial on the Classical Theories of Electromagnetic Scattering and Diffraction

- Reflectionless excitation of arbitrary photonic structures: a general theory

- Optimization Methods

- Multiobjective and categorical global optimization of photonic structures based on ResNet generative neural networks

- Machine learning–assisted global optimization of photonic devices

- Artificial neural networks for inverse design of resonant nanophotonic components with oscillatory loss landscapes

- Adjoint-optimized nanoscale light extractor for nitrogen-vacancy centers in diamond

- Topological Photonics

- Non-Hermitian and topological photonics: optics at an exceptional point

- Topological photonics: Where do we go from here?

- Topological nanophotonics for photoluminescence control

- Anomalous Anderson localization behavior in gain-loss balanced non-Hermitian systems

- Quantum computing, Quantum Optics, and QED

- Quantum computing and simulation

- NIST-certified secure key generation via deep learning of physical unclonable functions in silica aerogels

- Thomas–Reiche–Kuhn (TRK) sum rule for interacting photons

- Macroscopic QED for quantum nanophotonics: emitter-centered modes as a minimal basis for multiemitter problems

- Generation and dynamics of entangled fermion–photon–phonon states in nanocavities

- Polaritonic Tamm states induced by cavity photons

- Recent progress in engineering the Casimir effect – applications to nanophotonics, nanomechanics, and chemistry

- Enhancement of rotational vacuum friction by surface photon tunneling

- Plasmonics and Polaritonics

- Shrinking the surface plasmon

- Polariton panorama

- Scattering of a single plasmon polariton by multiple atoms for in-plane control of light

- A metasurface-based diamond frequency converter using plasmonic nanogap resonators

- Selective excitation of individual nanoantennas by pure spectral phase control in the ultrafast coherent regime

- Semiconductor quantum plasmons for high frequency thermal emission

- Origin of dispersive line shapes in plasmon-enhanced stimulated Raman scattering microscopy

- Epitaxial aluminum plasmonics covering full visible spectrum

- Metaoptics

- Metamaterials with high degrees of freedom: space, time, and more

- The road to atomically thin metasurface optics

- Active nonlocal metasurfaces

- Giant midinfrared nonlinearity based on multiple quantum well polaritonic metasurfaces

- Near-field plates and the near zone of metasurfaces

- High-efficiency metadevices for bifunctional generations of vectorial optical fields

- Printing polarization and phase at the optical diffraction limit: near- and far-field optical encryption

- Optical response of jammed rectangular nanostructures

- Dynamic phase-change metafilm absorber for strong designer modulation of visible light

- Arbitrary polarization conversion for pure vortex generation with a single metasurface

- Enhanced harmonic generation in gases using an all-dielectric metasurface

- Monolithic metasurface spatial differentiator enabled by asymmetric photonic spin-orbit interactions