An experimental approach for the determination of the physical and mechanical properties of a sustainable geopolymer mortar made with Algerian ground-granulated blast furnace slag

-

Zineb Abeoub

, Ramdane Sidali Amrouche

Abstract

Geopolymer technology is widely recognized and extensively tested as a sustainable alternative to conventional cement, with considerable environmental and economic benefits through waste management; however, it remains largely unstudied and underutilized in Algeria. Despite the abundant availability of aluminosilicate materials, there is only limited and incomplete research on pozzolans and metakaolins in the region. This article aims to address this gap by investigating the use of Algerian ground-granulated blast furnace slag (GGBFS) to develop an optimal formulation for producing high-performance geopolymers. To determine the optimal combination of alkaline activators compatible with GGBFS and sand content, a series of experiments were conducted on fresh and hardened GGBFS-based geopolymer mortars (GPMs) to verify properties such as workability, setting time, water absorption, efflorescence stability, and mechanical strength. Techniques used to characterize the microstructure of a subset of geopolymer samples included attenuated total reflectance – Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy, X-ray diffraction, and scanning electron microscopy – energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy. This research not only emphasizes the environmental benefits of repurposing waste materials but also advances the development of more sustainable and durable GPMs, presenting a promising approach to improving environmental stewardship in material science practices.

1 Introduction

1.1 Research motivation

In Algeria, the annual production of granulated blast furnace slag (GBFS), crystalline slag, and steel slag is estimated at about 2 and 1.5 million tons per year. The iron and steel complex of El Hadjar in eastern Algeria produces large quantities of a GBFS, which is mainly used as a mineral additive (up to 30%) in the production of ordinary cement. GBFS brings many environment and economic benefits when used as a cement replacement, leading to sustainable solutions in construction [1]. Because its production cost is estimated to be zero except for the embodied energy of the grinding process, estimated to be 0.3 MJ/kg, which represents 7% of the embodied energy of cement [2]. Furthermore, Portland cement concrete (PCC) has a lower economic index (0.320) compared to all geopolymer concretes (GPCs) produced from industrial waste [3].

The economic index for GPC made from ground-granulated blast furnace slag (GGBFS) is estimated to be 0.545 [3]. Experimental data indicate that the total production cost for M30 grade PPC is $109.59, with cement comprising the largest portion of the cost at 53.38% [3]. On the other hand, the production cost for M30-grade GPC, activated with sodium hydroxide (NaOH) and sodium silicate (Na2SiO3) solutions in a 2.5:1 ratio of Na2SiO3 to NaOH at a 12 molar NaOH concentration, is approximately $79.22 [3]. In this case, sodium hydroxide solution accounts for 37.26% of the total production cost [3]. In summary, the production cost per cubic meter of M30 grade of GGBFS-GPC is 27.71% lower than that of PCC of the same grade [3].

In this context, the current research aims to exploit the locally produced GBFS to develop a sustainable eco-friendly geopolymer mortar (GPM).

1.2 Research background

Sustainability and green development are central topics of global discussions across various sectors. Notably, the construction industry is a principal contributor to CO2 emissions, exacerbating climate emergencies and increasing global temperatures [1,4,5]. The cement industry is a substantial contributor to global warming, releasing approximately 0.9 ton of CO2 for every 1 ton of cement produced, making it the second largest contributor to this issue [1]. Moreover, the manufacture of ordinary Portland cement (OPC) ranks third in terms of the most energy-intensive building material after the manufacture of steel and aluminium, requiring ∼120 kW h per ton [6]. Despite this, the need for OPC to manufacture concrete, the world’s main binder in the construction sector, remains increasing. The increasing need for cement worldwide requires large production of clinker (CaO), which requires substantial amounts of natural materials such as shale, lime, silica, and calcium. This process leads to significant CO2 emissions into the atmosphere and the overexploitation of natural resources [6]. Moreover, 2.75 tons of precursor materials is required to produce one ton of OPC [6]. Research forecasts predict that OPC concrete production will increase by 200% by 2025 due to the development of global infrastructure [1]. Furthermore, the production of OPC accounts for about 8% of global greenhouse gas emissions [1]. The adverse environmental impact and high-energy requirements of cement manufacturing require an environmentally friendly and sustainable alternative, such as GPC [6], a versatile class of materials with numerous potential applications [7,8]. GPM and concrete are revolutionizing modern construction and sustainability efforts by offering durable, environmentally friendly alternatives to traditional cement-based materials [4,5,6,7,8,12]. Their applications span diverse industries, including construction, infrastructure, and environmental management, driven by their exceptional resistance to environmental degradation and fire, as well as their lower carbon footprint [9,10,11,12,13]. Global projects highlight the potential of these materials on a large scale. India’s GPC Project demonstrates their use in general construction, Australia’s Sustainable Construction Project integrates them into eco-friendly building practices, the UK is exploring their utility in infrastructure repair, and the Netherlands is advancing 3D printing with GPM [10,11,12,13].

Despite their promise, challenges such as securing high-quality raw materials, maintaining production consistency, and optimizing curing conditions must be addressed to unlock their full potential and pave the way for widespread adoption in the future of green building [10,11,12,13,14].

GP materials are synthesized from aluminosilicate sources, such as fly ash (FA) and slag, which, when combined with an alkaline solution under high pH conditions, form Si–O–Al–O polymer bonds [1,2,4,6,9]. The chemical reaction (geopolymerization) and rheological and mechanical properties of GPC depend on several factors, the most important of which are the alkaline solution, the amount of activator used, the fineness of the raw materials, and the curing time [1,9,11,12,15]. GPs were observed to exhibit higher apparent activation energies (Ea) compared to portland cement I (37.5 kJ/mol for α = 0.2) and GGBFS (75.8 kJ/mol for α = 0.2) [16]. This increased Ea slows the reaction at lower temperatures, resulting in extended setting times [16]. However, it also enhances the durability and chemical resistance of GPs by promoting the formation of a denser and more stable structure [16]. The Ea is influenced by several factors, including the chemical composition of the material (such as slag), the type and concentration of activators, curing conditions (such as temperature), and the water-to-binder ratio [16].

Due to their exceptional heat resistance, GPs have been extensively utilized in the production of thermal insulation materials and energy storage concretes [17]. Moreover, GP coatings on steel have proven effective in preserving structural integrity under high-temperature conditions [17]. Duan et al. [18] reported that the heat resistance of GPC, synthesized through the alkaline activation of a combination of fluidized bed FA and metakaolin (MK) with a mass ratio of 1.0 in alkali silicate solutions, is evident in its ability to resist both instability and shrinkage. Notably, the mass loss of GPC is significantly lower compared to that of OPC concrete after exposure to 600°C, primarily due to the decomposition of Ca(OH)2 in OPC concrete [18]. Ye et al. [19] reported that tailing/slag-based GP experiences a significant strength reduction when exposed to a fire at 1,000°C, losing more than 40 MPa, which corresponds to a 66.67% reduction. However, it demonstrates a strength gain after heating at 1,200°C, attributed to sintering and densification processes. In another study, Sarker et al. [20] observed that OPC concrete suffered severe spalling after exposure to 800 and 1,000°C fires, whereas GPC exhibited superior fire resistance, showing only minor surface crackling. This is because the high-density and low-porosity nature of GPM further contributes to its resistance to cracking, as it reduces the movement of water and air that can lead to volume changes [21]. The authors of previous studies [10,12,20,21] also emphasized that GPMs and GPC exhibited better performance at elevated temperatures in comparison with control cement mortar mixture. For instance, Nkwaju et al. [22] found that lateritic soil-based geopolymer showed a significant reduction in thermal conductivity, decreasing from 0.77 to 0.55 W/mK, with the incorporation of 7.5 wt% sugarcane bagasse fibres, highlighting its potential as a sustainable insulation material. GPM typically exhibits less shrinkage compared to conventional cement mortar, primarily due to its distinct chemical structure and low hydration-based shrinkage [23]. Similarly, Kong and Sanjayan [24] reported that FA-based geopolymer exhibited a shrinkage of approximately 1% between 200 and 300°C, with an additional shrinkage of 0.6% occurring between 700 and 800°C. Furthermore, Yang et al. [25] found that alkali-activated slag and FA-blended recycled aggregate concrete achieve a freeze–thaw resistance grade of F300, with minimal internal damage and accurate damage models based on mass loss and elasticity. In comparison with traditional mortar, the workability and setting time of GPM can be easily modified by altering the components of the GP mixture [4,5,6,7,8,14]. GPC also offers chemical stability compared to ordinary and high-performance OPC-based concrete, which cures and chemically decomposes upon increasing temperatures [7,12,18,20,23]. The slag-based GPC, with a strength of 40 MPa, demonstrated a 33% reduction in strength after 1 year of exposure to an acetic acid solution (pH = 4), which was notably lower than the 47% reduction observed in ordinary OPC concrete [21]. In a 2% H2SO4 solution, the GPC experienced an 11% loss in strength, whereas OPC concrete exhibited a significantly greater reduction of 36.2% [21]. In addition, fly ash – ground granulated blast furnace slag-based GPs with high Ca content in their precursors exhibit excellent resistance to both acid and sulphate attacks [26,27]. Moreover, GPC (such as fly ash-based geopolymer concrete) can create a protective ferric oxide layer on the steel reinforcement, which prevents corrosion by maintaining an alkaline environment [12]. This leads to a lower corrosion rate compared to OPC concrete [12]. GPMs also demonstrate significantly greater resistance to alkali–silica reaction (ASR) compared to mortars based on OPC [10,28]. This superior performance is largely attributed to their unique chemical composition and the limited presence of calcium hydroxide, which is a critical contributor to the ASR process [28]. A study by Mahanama et al. [28] examined the influence of GGBFS content on ASR in GPs through accelerated mortar bar tests. The findings revealed that while ASR expansion in GPs increased with higher GGBFS content, it consistently remained lower than that in OPC mixtures. These results highlight the need to carefully consider key factors, particularly the type and molarity of the alkali solution, when incorporating GGBFS into GP systems. The availability of GGBFS worldwide due to the growth and expansion of iron and steel production encourages the use of GGBFS as an alternative to conventional OPC [29]. In addition, global stainless-steel consumption will increase by 3.6% by 2023, with a consequent growth in the amount of slag [29]. Therefore, the use of GGBFS in GPM significantly contributes to sustainability through multiple mechanisms, leveraging its role as an industrial by-product and its chemical properties [29]. By incorporating GGBFS, waste destined for landfills is effectively reduced, promoting waste management practices that align with circular economy principles [26,27,29]. This repurposing minimizes environmental pollution and supports resource efficiency by replacing natural raw materials such as limestone and clay, which are traditionally extracted for cement production [9,12]. Furthermore, GPM made with GGBFS is a low-carbon alternative to PC, producing 60–80% fewer CO2 emissions due to its reduced reliance on energy-intensive clinker production [4,10,26]. Turner and Collins [30] proved that PC was by far the most significant contributor to emissions, contributing to 76.4% of CO2-e for OPC concrete. However, the alkali activators expend significant energy during manufacture and the contribution of the geopolymer binder (FA + sodium silicate + sodium hydroxide) is 201 kg CO2-e/m3 compared with OPC 269 kg CO2-e/m3 (25.2%) [30]. The total emissions from the OPC and GPC comparison mixes used in this report were estimated as 354 and 320 kg CO2-e/m3, respectively, showing 9% difference [30]. Moreover Al-Fakih et al. [31] found that the maximum CO2 footprint of GGBFS-based GPC was estimated at 276.1 kg CO2-e/m3. A further consideration would be to compare GPC with CO2-e arising from blended FA or slag cements that comprise the partial replacement of OPC [31]. Although calculations have not been made on specific mixes of mixed cement concrete, CO2 emission reductions of 19–29% are quite possible [30] and would provide lower CO2 emissions than GP binders [30].

In addition to its environmental benefits, GGBFS enhances the performance of GPMs by providing improved resistance to chemical attacks, reducing permeability, and increasing durability [4,10,14,15,16]. These properties extend the lifespan of structures, lowering the frequency of repairs and replacements and reducing overall material consumption and associated environmental impacts. Through these combined benefits, GGBFS serves as a pivotal material in advancing sustainable construction practices. Moreover, research indicates that GPMs produced from industrial by-products such as FA and rice husk ash offer sustainable and cost-effective alternatives, contingent on local availability and specific application needs [23]. However, GGBFS-based-GPMs demonstrate superior performance in terms of strength, durability, and fire resistance [10,12,16,27,31]. In the study conducted by Tran et al. [14] for the development of sustainable ultra-high-performance concrete containing GGBFS and glass powder, they found that all mixes had lower manufacture costs than the PCC mix; differences among them were trivial. Experimental results demonstrated that the ecological enhancement of normal-strength mortars is both viable and feasible. By replacing 70–90% of the cement with GGBS, energy consumption for producing 1 tons of binder can be reduced by 67–86%, while the performance energy decreases significantly from 25.4 (kW h/t)/MPa to a range of 6–8 (kW h/t)/MPa [32]. The energy research conducted by Verma et al. [10] revealed that GPC based on FA and GGBFS embodied energy less compared to the OPC concrete. The GPC production generally uses FA, GGBFS, NaOH, sodium silicate, aggregate (fine and coarse), and water [14]. The FA and GGBFS are solid industrial wastes produced by the thermal power plant and steel plant [1,6,11,20]. The FA is directly used in the mix, but the GGBFS requires grinding before use in the mix [10]. The embodied energy for the grinding process is calculated as 0.3 MJ/kg [2]. NaOH production’s embodied energy is 20.5 MJ/kg, and sodium silicate production is 5.37 MJ/kg [2]. There is zero embodied energy in FA and water [2]. The coarse aggregate and fine aggregates’ embodied energies are 0.22 and 0.02 MJ/kg, respectively [10]. The embodied energy of sulfonated naphthalene formaldehyde (SNF) superplasticizers is reported to be 12.6 MJ/kg [10]. The total embodied energy of the OPC concrete is 1897.86 MJ/m3, whereas the embodied energy of the GPC is 1749.21 MJ/m3 [10]. The GPC’s embodied energy is less compared to the OPC concrete [10]. Studies have proven that the performance of POC is lower compared to alkali-activated slag concrete [6,11,12,13]. The geopolymerization of GPC was expedited under ambient curing conditions with the incorporation of GGBFS, leading to a shorter setting time, better workability, and increased mechanical strength (MS) at an early age [10,14,15,27,28,29]. This phenomenon is attributed to the rapid hydraulic reaction of GGBFS, which results from its large surface area [33]. Furthermore, the particle size significantly influences the reactions occurring in GGBFS [33]. For instance, other researchers have observed that a finer particle size (4,170 cm²/g) led to better workability and compressive strength [27].

Alternatively, Hasnaoui et al. [8] observed that the optimal mechanical and rheological properties were achieved with a mixture having a GGBFS/MK ratio of 1, a GGBFS + MK/activator ratio of 3, and a SiO2/Na2O ratio ranging between 1.6 and 1.8. On the other hand for the SiO2/Na2O molar ratio of 1.16, GP consisting of 95% GGBFS and 5% MK recorded compressive strengths of 47.84 MPa at 24 h [15]. Moreover, Hasnaoui et al. [8] found that for GPs with 50% GGBFS and 50% MK, all mixes with a GGBFS + MK/activator ratio lower than 3 are characterized by higher mechanical resistances than that of PCM (48.4 and 6.4 MPa for compressive and flexural strengths, respectively), whatever the SiO2/Na2O ratio. On the other hand, the tensile strength results clearly demonstrated the potential of GPM as a new alternative repair material [20,29]. In a previous study, after 24 h, the GPM exhibited a split tensile strength of 2.95 MPa, which was almost 10 times greater than that of OPC mortar (0.32 MPa) [15]. Scanning electron microscopy/energy dispersive analysis of X-rays, X-ray diffraction (XRD), and FTIR analyses conducted by Prusty [4] on GGBFS-activated gels revealed that the enhanced mechanical properties of GPC mixtures are primarily due to the reaction products formed in alkaline-activated slag and FA mixtures. These products are predominantly governed by the C–(A)–S–H series of gels, with the presence of C–S–H and N–A–S–H gels. Furthermore, XRD spectra indicate that increasing GGBFS substitution promotes the formation of N–(C)–A–S–H gel, which significantly contributes to the higher compressive strength of GPC [4]. Similarly, Dai et al. [5] reported that the coexistence of both N–A–S–H and C–S–H phases in GGBFS and FA mixtures treated at room temperature leads to superior mechanical properties compared to alkali-activated FA systems, which predominantly produce N–A–S–H gels. However, despite the good properties of GGBFS-based GP cement and its availability in large quantities in most parts of the world, GGBFS-based GP has not been widely used due to a lack of adequate studies. The main aim of most of the available studies has been to examine the effects of GGBFS addition on the chemical, mechanical, and microstructural properties of GP concrete. For this reason, conducting further investigation on the chemical, mechanical, and microstructural properties of GGBFS GPs to better understand the behaviour of this type of cement is imperative to popularize and promote the use of Algerian GGBFS as a cement material. The present work is devoted to the physico-chemical properties and durability of geopolymeric binders synthesized by the alkaline activation of GGBFS through an optimized formulation approach. This study looks at how the sand-to-GGBFS mass ratio affects the mechanical and rheological properties of the mortars, as well as how the SiO2/Na2O molar ratio in alkaline solution influenced these properties. Additionally, microstructural investigations, including ATR, XRD, and scanning electron microscopy – energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (SEM-EDS) analyses, were carried out. Water porosity and efflorescence tests were also performed to enhance the durability of the concrete, as these are key factors in concrete deterioration over time [34].

1.3 Research contribution

The novelty of the research consists of the adoption of an experimental approach to determine the physical and mechanical properties of a sustainable GPM made with Algerian GGBFS. The study is devoted to the physico-chemical properties and durability of geopolymeric binders synthesized by the alkaline activation of GGBFS through an optimized formulation approach.

2 Materials and modalities

2.1 Characterization of the materials used

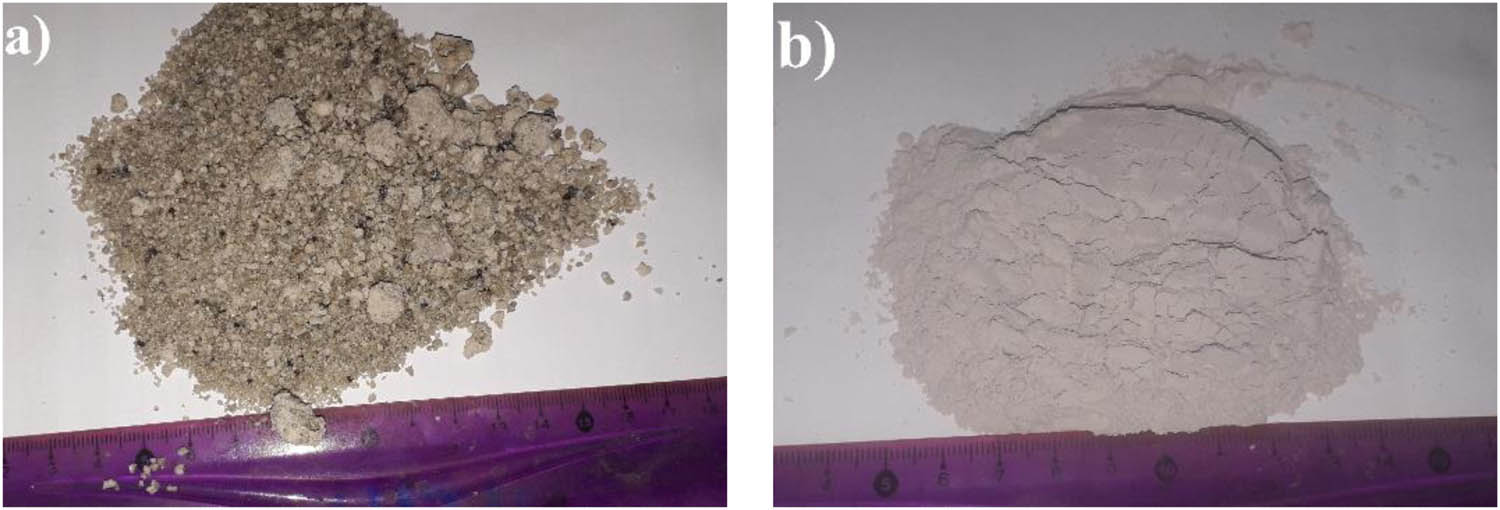

Fine aggregates, GGBFS as a binder, and water and alkaline solution as catalysts used in this study were detailed in the following. The GBFS was purchased from the Siderurgica Steel Industry Complex (El-Hadjar, Algeria) (Figure 1a) and consisted of 10 mm maximal size of spherical grains of a light grey colour. It has therefore been previously ground before its use in cement systems. The GBFS characteristics obtained after grinding are as follows: 4,100 ± 100 cm2/g Blaine for specific surface area and (D10 = 1.807 µm, D50 = 15.489 µm, D90 = 54.939 µm) for the diameters (Figure 1b). A density of 2.9 g/cm3 was obtained according to the American society for testing and materials (ASTM) C204 standard [35]. Microstructural investigations (XRD, SEM, X-ray fluorescence [XRF]) revealed that the slag is amorphous with the slight presence of calcite (CaCO3) (Figure 11). The amorphous nature of Algerian (GGBS) offers several advantages in geopolymerization compared to its crystalline counterparts. Its disordered atomic structure enhances reactivity, facilitating the release of essential ions such as silica, alumina, and calcium during alkali activation, which leads to a denser and stronger GP network [6,7,34]. Additionally, it ensures better chemical homogeneity, resulting in consistent performance and improved mechanical properties, including faster setting times and greater durability [7,12]. Unlike crystalline forms, amorphous GGBS does not require extra energy-intensive treatments to enhance its reactivity, making it a sustainable and efficient choice for geopolymer applications [7]. The chemical composition of GGBFS (Table 1) was analysed by XRF using a model S2 PUMA (XY) machine, BRUKER brand. The GGBFS of El Hadjar is essentially composed of lime (CaO = 42.11%), silica (SiO2 = 36.85%), alumina (Al2O3 = 8.29%), and magnesia (MgO = 3.8%), which are crucial oxides during the hydration process to produce C–(A)–S–H gels, enhancing strength and durability [4]. Based on chemical analysis, Algerian GGBFS is highly suitable for GPM due to its high calcium oxide content (up to 42.11%), which supports the formation of both C–S–H and C–A–S–H gels, enhancing early strength and material densification [4,7,14,23]. This high calcium content enables hybrid-binding phases of C–A–S–H and N–A–S–H gels, which improve GP performance [4,10,25].

Experiment materials: (a) GBFS of the steel complex of El-Hadjar (Algeria) and (b) GGBFS.

Chemical composition of Algerian GGBFS Algerian

| Components | Content (%) |

|---|---|

| SiO2 | 36.85 |

| Al2O3 | 8.29 |

| Fe2O3 | 1.69 |

| CaO | 42.11 |

| MgO | 3.80 |

| SO3 | 1.39 |

| K2O | 0.86 |

| TiO2 | 0.34 |

| MnO | 2.80 |

| BaO | 3.37 |

| PAF | 0 |

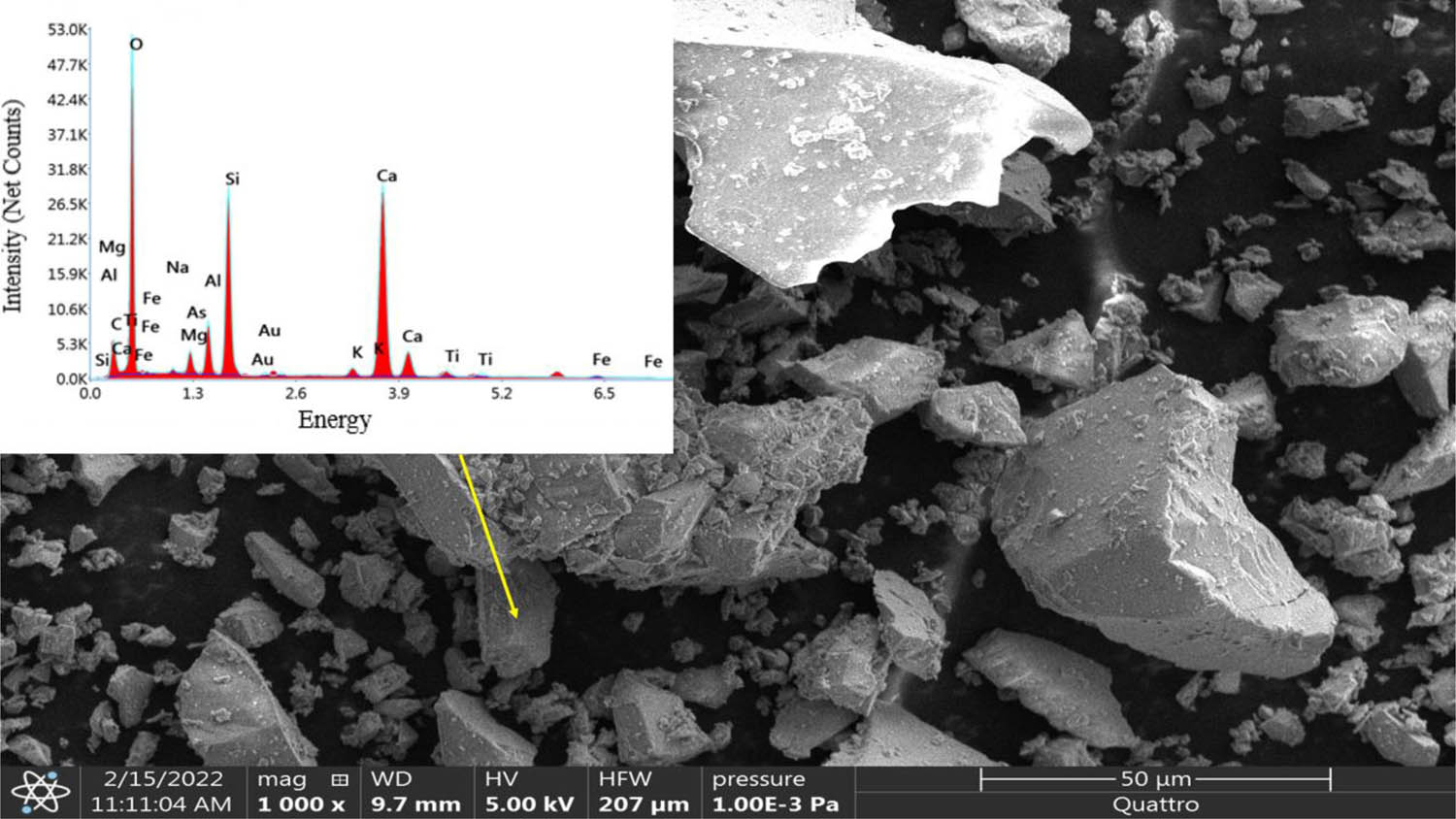

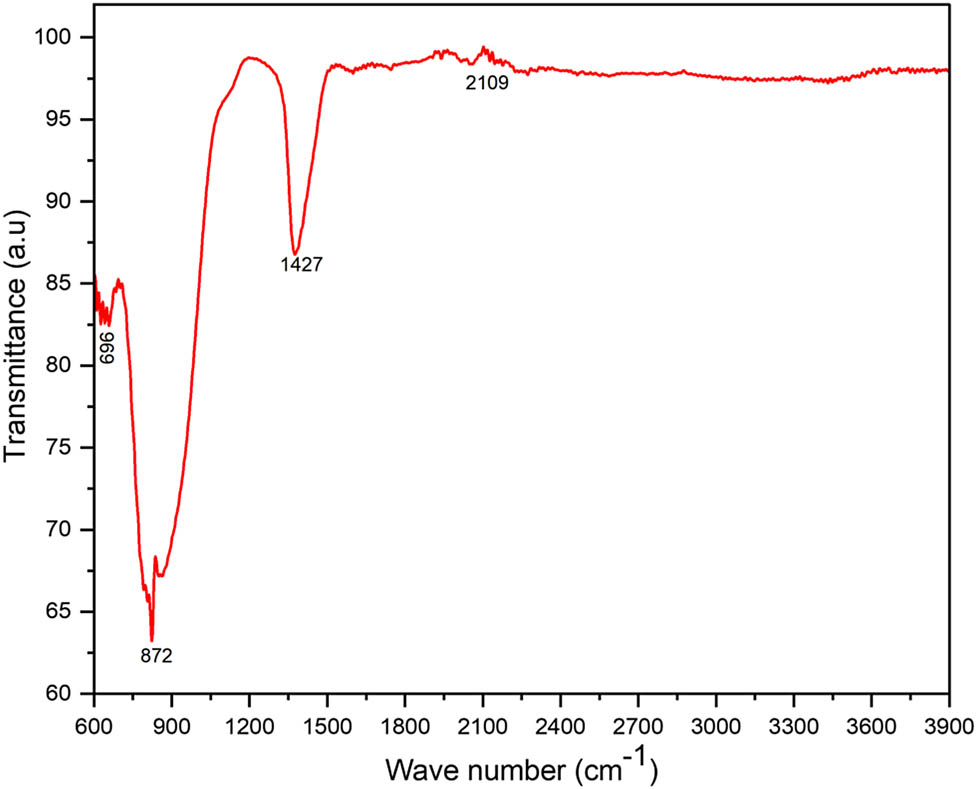

The GGBFS from Algeria has adequate levels of silicon dioxide (36.85%) and aluminium oxide (8.29%), facilitating the formation of N–A–S–H, the primary binding phase in GPMs [4,25]. Additionally, low sulphur trioxide (SO₃) and magnesium oxide (MgO) contents reduce the risk of deleterious reactions, such as expansion or cracking due to delayed ettringite formation (DEF) or magnesia hydration [36]. The loss on ignition indicates high purity, ensuring better reactivity for alkali activation [37]. The amorphous structure of the slag (Figure 11), formed through rapid cooling, is highly reactive under alkaline conditions, aiding efficient geopolymerization [7,8,12,27,33,37]. Finally, a suitable alkali content facilitates the dissolution of the silica and alumina in the slag during the activation process [7,8,10,17,31,37]. If the slag contains trace alkali elements such as Na2O and K2O, these can enhance reactivity under alkaline conditions [12]. This is what is available in this slag, as it contains trace K2O, estimated at 0.86%. The chemical composition of Algerian GGBFS is notable for its lack of sulphates, which, when reacting with excessive alkalis, typically produce salts that migrate to the surface and result in significant efflorescence [34]. The XRF results are consistent with those of EDX analysis (Figure 2). The strong absorption bond of the GGBFS at 872 cm−1 is attributed to an elongation of the C–O bond (Figure 3), corresponding to the presence of calcite CaCO3 phases [6], while the weak band of 1,428 cm−1 is attributed to the elongation of the inorganic C–O bond [4]. The presence of amorphous AlO6 octahedra is detected at 696 cm−1, which is assigned to Si–O and Si–O–Al vibrations [4]. To characterize the composition of the slag, a quality coefficient (Mq) and basicity coefficient (Mb) are defined separately in Eqs. (1) and (2):

Morphology of Algerian GGBFS performed with SEM-EDS.

Attenuated total reflectance – Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (ATIR-FTIR) spectra of Algerian GGBFS.

The Mq and Mb coefficients, equal to 1.46 and 1.11, respectively, indicate that GGBFS is classified as neutral and basic. The hydraulic activity index using the Keil method is given by

where S b is the Blaine specific area (S b = 4,100 cm2/g) and F the percentage of slag fines (friability < 80 µm in our case, F = 100%). The hydraulic activity index of the GGBFS of El-Hadjar (= 410) makes it a very active slag. An activator solution comprising commercially available sodium silicate (SS) and sodium hydroxide (SH) was utilized in the formulation of geopolymers. SH and SS are critical components in the geopolymerization process, each playing distinct yet complementary roles. SH ensures effective dissolution of aluminosilicate precursors and acts as a catalyst to accelerate chemical reactions [38]. Meanwhile, SS promotes gelation and enhances the structural integrity of the geopolymer matrix [38]. Their interaction is crucial for achieving a well-balanced geopolymerization process, resulting in strong and durable GPC [38]. This selection was made considering that the most used activators for GGBFS-based GPM are alkaline solutions such as sodium silicate, sodium hydroxide, potassium hydroxide, or their combinations [38]. Additionally, calcium hydroxide and sodium carbonate are frequently employed [38]. These activators enhance the mortar’s performance by improving compressive strength, adjusting setting time, and enhancing durability [38]. The combination of sodium silicate and sodium hydroxide, in particular, provides high strength and reduces porosity, while sodium carbonate enables controlled setting [38]. However, excessive alkalinity may compromise workability or durability [4,38]. The selection of an optimal activator ensures a balance of strength, workability, and longevity for specific applications. Therefore, in this study, the chosen solution (SS) had a density of 1,357 g/l, a molar ratio SiO2/Na2O of 3.35, and a composition by weight of 8% for Na2O, 26.4% for SiO2, and 61.6% for H2O to generate varied molar ratios, and 99% pure (SH) pellets were added to the Na2SiO3 solution. To make GPMs, the mixture was allowed to cool to ambient temperature and then stored. In this investigation, the aggregates used for preparing mortar specimens were standardized CEN EN 196-1 sand, with a granular size of 0–2 and a siliceous composition. Table 2 presents the physical characteristics. To ensure purity and prevent contamination from mineral salts, distilled water was used to prepare and adapt the fluidity of the mortars.

Physical characteristics of the sand used

| Parameter | Values |

|---|---|

| Modulus of fineness | 2.65 g/cm3 |

| Absorption coefficient | 0.2 |

| Absolute density | 2.64 g/cm3 |

2.2 Synthesis of GPMs

Ten mixtures were prepared by varying the sand/GGBFS mass ratio and the SiO2/Na2O molar ratio of the alkaline solution. In both steps, the water/solid geopolymer binder (W/C) ratio and that of GGBFS to the activator were set to 0.36 and 3, respectively. The effect of the sand/GGBFS mass ratios of 1.5, 2, 2.5, and 3 was also studied. All properties of the mixtures are gathered in Table 3. The selection of the optimum (sand/GGBFS) mass ratio was based on the results of flow ability, setting time, MSs, and water absorption. The optimal sand/GGBFS mass ratio determined in the first step was used to examine the impact of varying the following SiO2/Na2O molar ratios: 1.11, 1.14, 1.17, 1, 20, 1.23, 1.26, and 1.29, on the rheological and mechanical properties, water absorption, and efflorescence. The GP mortar was prepared in three steps after preliminary experiments to determine the most effective mixing method for Algerian GGBFS. It was found that mixing the alkaline solution first for 1 min ensures complete geopolymerization of the aluminosilicate. Adding sand to the paste followed by water for 2 min produces a new slurry. The mixture is then poured into metal moulds to create prismatic samples measuring 40 mm × 40 mm × 160 mm and 40 mm × 40 × 40 mm (Figure 4). Before assembly, the inside of the moulds was lightly oiled to aid easy demoulding of the mortars. The moulds were then securely assembled and placed on an impact table, where they were filled evenly with the slurry up to the halfway point. The first layer of slurry was compressed for 60 s (1 impact per second) to ensure proper compaction. The second layer of slurry was added and again compressed with 60 impacts to eliminate any air bubbles trapped during pouring. Once prepared, the specimens were sealed in special plastic oven bags to prevent water loss during the curing process. After 24 h in a humid environment at 20 ± 2°C, all specimens were demoulded and stored under the same conditions until testing. Because ambient curing is slower, it contributes to improved long-term strength and durability [7,38]. The choice of curing time and method should align with the specific application needs, ensuring a balance between early strength and long-term performance [1,7,38]. On the other hand, heat treatment and steam curing accelerate the process, promoting faster strength development and higher early strength, although they require careful monitoring to avoid the risk of thermal cracking [1,7,10,36,37,38].

Various formulations of GPMs considered in this study

| Mix ID | SiO2/Na2O | Weight ratio | Na2O content (%) | SiO2 content (%) | pH of activator | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sand/GGBFS | SS/SH | |||||

| G-1 | 1.17 | 1.50 | 1.24 | 6.92 | 31.58 | 13.42 |

| G-2 | 1.17 | 2.00 | 1.24 | 6.92 | 31.58 | 13.42 |

| G-3 | 1.17 | 2.50 | 1.24 | 6.92 | 31.58 | 13.42 |

| G-4 | 1.17 | 3.00 | 1.24 | 6.92 | 31.58 | 13.42 |

| G-5 | 1.20 | 3.00 | 1.28 | 6.79 | 31.63 | 13.30 |

| G-6 | 1.11 | 3.00 | 1.13 | 7.32 | 31.41 | 13.56 |

| G-7 | 1.14 | 3.00 | 1.18 | 7.15 | 31.48 | 13.48 |

| G-8 | 1.23 | 3.00 | 1.30 | 6.66 | 31.70 | 13.36 |

| G-9 | 1.26 | 3.00 | 1.38 | 6.50 | 31.77 | 12.42 |

| G-10 | 1.29 | 3.00 | 1.44 | 6.34 | 31.83 | 12.14 |

Water/GGBFS = 0.36, Water = water contained in SS + added Water, (Na2O, SiO2) = Content % in Alkaline solution.

Casting of GP mortar samples 40 mm × 40 mm × 160 mm.

2.3 Testing methods

2.3.1 Workability

The workability of GP mortars was measured using the modified flow table method of ASTM C1437-07[39], which is an effective method for determining the workability of cement paste and hydraulic cement mortars (Figure 5). This method relies on the determination of the average diameter from four diameters of flow measured symmetrically on two axes if the cone is lifted vertically immediately after pressing each layer of two layers 20 times with a pestle and dropping the flow table 25 times in 15 s. The setting time was determined by a standardized needle with VICAT apparatus according to the ASTM C191 [40].

Measuring the flow of the fresh GP mortar.

2.3.2 Compressive and flexural strength

Prismatic specimen (40 × 40 × 160) mm in the previously reported cure conditions were used to perform compression and bending tests. Using the hydraulic press (Model CME250) at a loading rate of 2,400 ± 200 N/s, the compressive and flexural strengths of the samples were determined according to ASTM C349 and ASTM C348 standards [41,42]. Resistance to compression was assessed at the age of 3, 7, 28, and 90 days and 28 and 90 days of age for bending. The values were obtained by the average of three tests each.

2.3.3 Durability

The evaluation of the GGBFS durability consisted essentially of the efflorescence tests and water absorption; the latter was determined at a curing age of 28 days, according to ASTM C642 [43]; and three identical cubes were used for each mixture. The cubes were placed in a ventilated oven for 24 h at 105 ± 5°C until a static dry mass (W d) was reached. They were then immersed in water (24 h) until completely saturated and weighed again (W s). The water absorption value was calculated from the following relation:

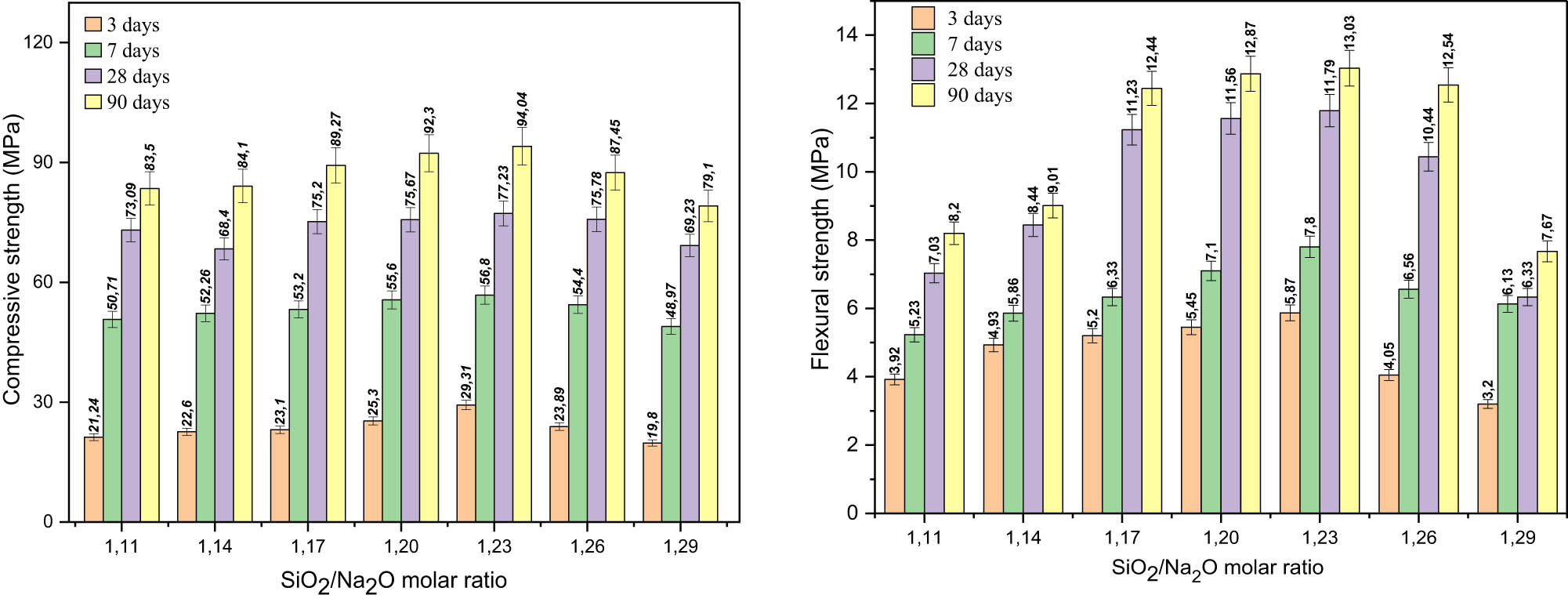

2.3.4 Efflorescence

Seven samples (P1, P5, P9, P10, P11, P12, and P13) were selected to investigate the influence of the SiO2/Na2O molar ratio on the degree of efflorescence. Cylindrical samples (35×70 mm), made in the laboratory, were protected with a plastic film to prevent any interaction with the external environment for 28 days. The samples were then partially immersed in Petri dishes containing distilled water for 73 h to induce efflorescence, as shown in Figure 10.

The degree of efflorescence was evaluated in our research by visual comparison and the use of a digital camera due to the absence of international standards or approved methods for calculating the degree of efflorescence [8].

2.3.5 Microstructural investigation

To examine the effects of several factors on the microstructural properties of GGBFS-based GP, and to identify the different types of geopolymer gels (such as C–(A)–S–H and N–A–S–H), four specimens (G-6, G-4, G-8, and G-10) from the ten compositions listed in Table 3 were selected. The samples underwent microstructural and morphological characterizations using SEM coupled with X-ray (EDX) analysis to perform morphological and microstructural analyses after 90 days of curing. The SEM-EDX analysis was conducted on pieces from the compression test with dimensions of 0.5 cm × 0.5 cm × 0.5 cm, using the Phenom ParticleX AM by Thermo Scientific. This versatile benchtop SEM, designed for additive manufacturing, ensures high purity at the microscale. XRD and ATR-FTIR analyses were performed on both the powdered GGBFS and selected samples (G-6, G-7, G-4, G-5, G-8, G-9, and G-10) after 90 days. Analyses (ATR) were conducted on a BRUKER brand FTIR (ALPHA) Fourier transform infrared spectrometer between 500 and 4,000 cm−1, with a resolution of 4 cm−1 and 64 spectrum acquisitions. The main advantage of ATR sampling comes from the very short sampling path length and the depth of penetration of the infrared spectroscopy (IR) beam into the sample. However, simply placing the thick sample on the ATR crystal and applying pressure generate an almost perfect result. The total analysis time of the thick polymer by ATR technique is less than 1 min. The mineral phases were identified by powder XRD (Philips diffractometer, model X’PER PRO [Panalytical] using Cu-Ka radiation by scanning from 5 to 90 [2 h] in steps of 0.1). The sample, in powder form, was placed on a sample holder and subjected to an X-ray beam, which will be diffracted in different directions depending on the crystalline structure of the material.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Fresh properties

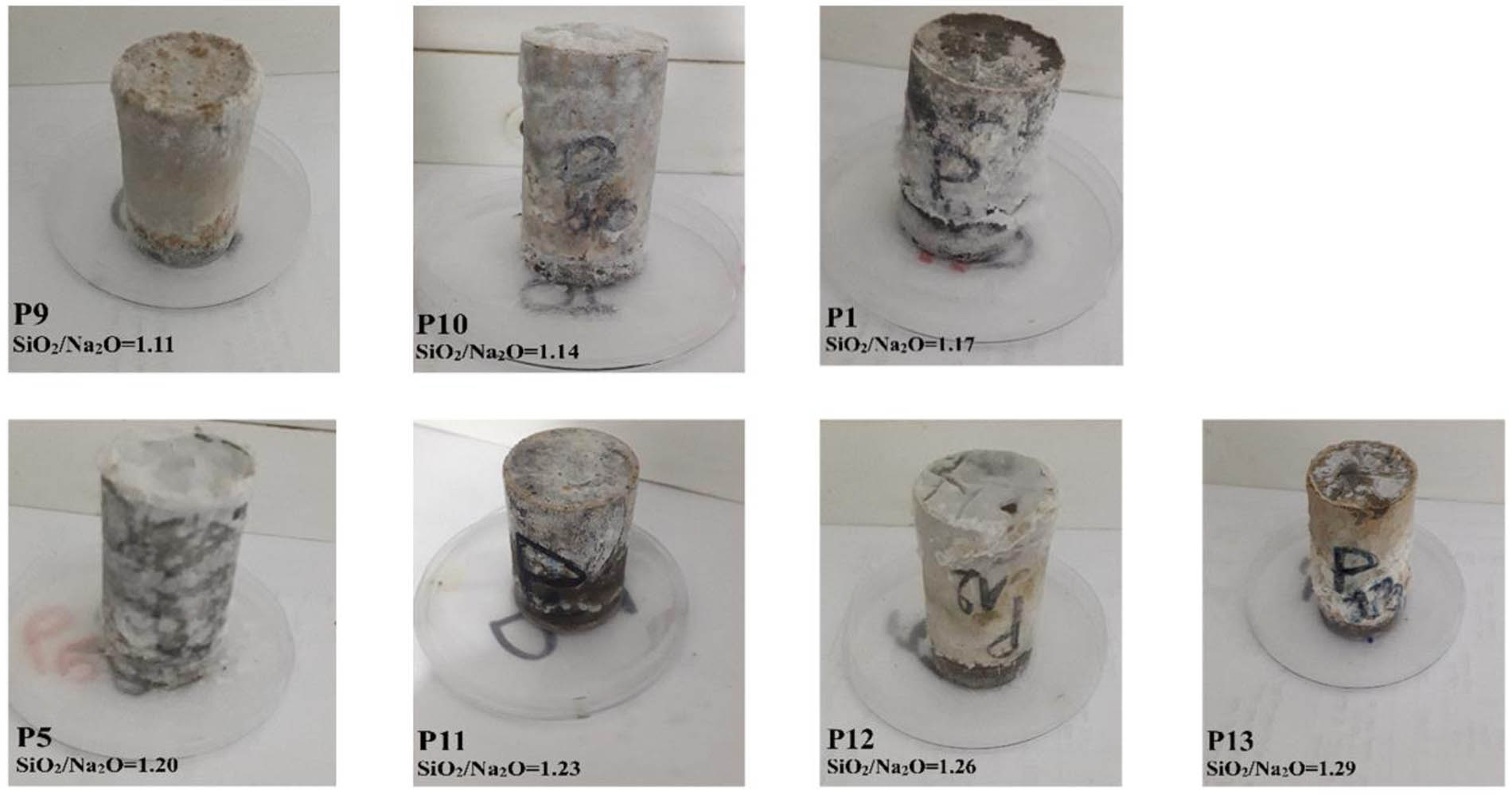

3.1.1 Workability

3.1.1.1 Effect of sand/GGBFS mass ratio

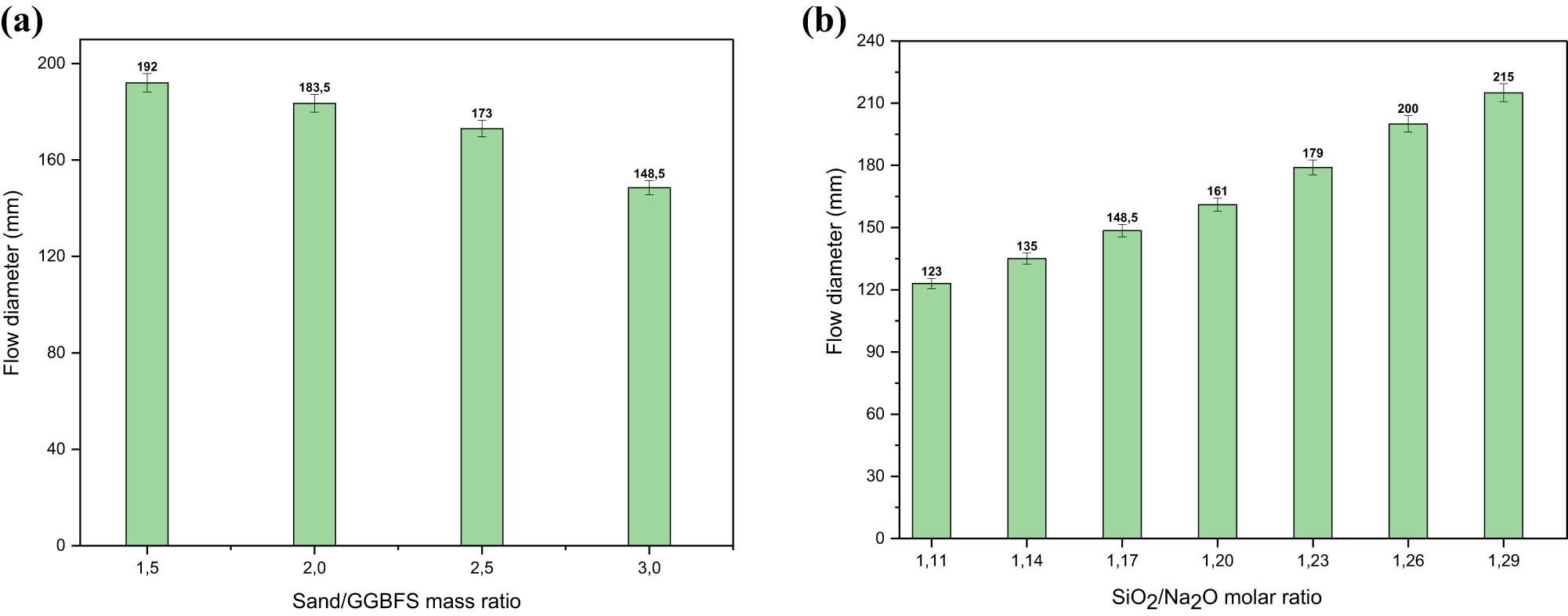

Figure 6a illustrates the effect of the sand-to-GGBFS mass ratio on the workability of GP mortar.

(a) Flow diameter of GGBFS GP mortars for different sand/GGBFS mass ratio and (b) effect of SiO2/Na2O molar ratio on flow diameter of GGBFS mortars.

The overall results exemplified that increasing the sand-to-mass ratio reduced the flow diameter of the mortars because formulations with a low sand-to-GGBFS mass ratio contain more fine particles favourable to mortar workability. The reduction in the flow diameter was approximately 4.42, 5.72, and 14.16% when the sand-to-GGBFS mass ratio was raised from 1.5 to 2, 2 to 2.5, and 2.5 to 3, respectively. The observed trend can be explained by the fact that a higher sand-to-GGBFS ratio increased the water demand, as the sand in the mixture absorbed more water, including capillary water. Consequently, with a higher sand-to-GGBFS ratio, the aggregates absorbed more water, which impeded the flow of the GP mortar and decreased its workability [44].

The workability of GP-based GGBFS mortars can be described as very stiff, stiff, moderate, or high [45]. On the other hand, the flow diameter of all the GGBFS mortars ranged between 148.5 and 216 mm. The value of the flow diameter varying between 140 and 160 mm is considered appropriate for the workability of geopolymer materials for easy placement in moulds [45].

These optimal values of workability correspond to sand/GGBFS mass ratios of 2.5 and 3 (Figure 6a). As a general conclusion, the development trend of GP-based GGBFS mortars was comparable to that of PC mortars.

3.1.1.2 Effect of SiO2/Na2O molar ratio

The rheological behaviour of geopolymers is strongly influenced by the SiO2/Na2O molar ratio [5,8,15,44]. Figure 6b presents the test results on how the SiO2/Na2O molar ratio affects the workability of the evaluated mortars. The data show that the flow diameter increased from 123 to 161 mm and from 161 to 215 mm as the SiO2/Na2O molar ratio rose from 1.11 to 1.20 and from 1.20 to 1.29, respectively. The main causes of this increase are the reduction in SH concentration and the increased presence of free water, which cause the alkaline solution’s viscosity to drop when the SiO2/Na2O molar ratio rises. In other words, the high amount of silica in the activated solution (31.83%) caused a decrease in pH (12.14) and an increase in the viscosity of the solution [7]. These results are consistent with those reported by others [5].

The GP-based GGBFS mortars had flow diameters that were high, moderate, and stiff. The average diameters were 148.5, 161, and 179 mm, which were limited to SiO2/Na2O molar ratios of 1.17, 1.20, and 1.23, respectively.

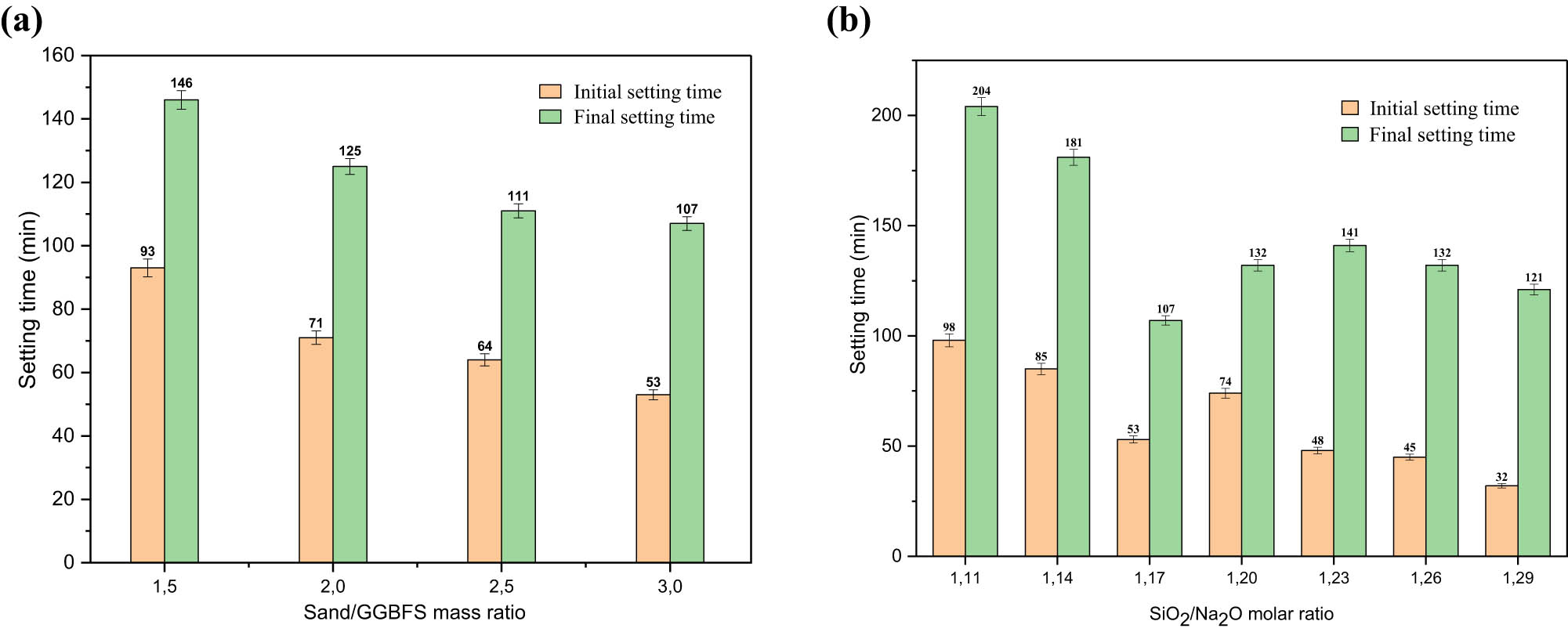

3.1.2 Setting time

3.1.2.1 Effect of sand/GGBFS mass ratio

Figure 7a illustrates the impact of the raw materials’ composition on the initial and final setting times of GP-based GGBFS. The data indicate that both the initial and final setting times are extended when the slag content is decreased. The samples with a sand/GGBFS mass ratio of 1.5 show an initial setting time of 93 min, which is reduced to 71, 64, and 53 min as the sand/GGBFS mass ratio increases to 2, 2.5, and 3, respectively. However, the final setting time decreases from 146 min to 125, 111, and 107 min. The large amount of sand present in the mixture absorbs a lot of water and consequently leads to reduced setting times. Previous studies have shown that a high slag content in GP-based GGBS mixtures leads to reduced setting times [5,8], due to the high reactivity of the slag under alkaline conditions, where the rate of formation of reaction products and the setting processes are accelerated. This is because the slag’s Ca, Si, and Al units dissolve relatively quickly and are present in large quantities in the solution, particularly calcium.

(a) Effect of sand/GGBFS mass ratio on setting times and (b) effect of SiO2/Na2O molar ratio on setting times.

3.1.2.2 Effect of SiO2/Na2O molar ratio

Figure 7b shows the effect of the SiO2/Na2O ratio on the initial and final setting times of GP mortar-based GGBFS, which shows a faster time in comparison with PC. Their initial setting time is between 98 and 32 min, while the final setting time varies between 204 and 121 min.

Furthermore, the time difference between the initial and final setting times was not long in all cases due to the fast reactivity of GGBFS, which made all final times short, where the longest final time recorded was 204 min. Figure 7b shows that the increase in the SiO2/Na2O molar ratio in the mixture has a remarkable impact on the acceleration of the setting time. Integration of a low amount of sodium silicate into the activator solution (i.e., SiO2/Na2O molar ratio = 1.11) extended both the initial and final setting times to 121 and 204 min, respectively. A decrease in sodium silicate content in the activator solution resulted in a lower pH (as shown in Table 3) and a reduction in the amount of soluble silica available in the medium. Extended setting times observed with low amounts of soluble silicates are linked to the slow release of Ca²⁺ from GGBFS and its subsequent reactions with silicates [5]. Longer setting times for the intermediate SiO2/Na2O molar ratio value (1.17, 1.20) were also recorded in GGBFS mixtures. On the other hand, further increases in the amount of sodium silicate to reach the SiO2/Na2O molar ratio value of 1.23 caused a significant decrease in the initial and final setting times to 107 and 53 min, respectively. This was due to the lower pH of the activator solution, which contributes to the increase of soluble silica in the mixtures, resulting in an acceleration of Ca2+ release from the silica-reacting GGBFS [8]. The initial setting time of GGBFS-based GPM with a SiO2/Na2O molar ratio of 1.29 was very fast (32 min), according to ASTM C1157 [46]. This was due to the availability of additional silica (31.83%), causing a less alkaline medium, which accelerates the solidification process through rapid polycondensation to form the C–S–H core [5]. Figure 7b and Table 3 show the direct effect of the Na2O content of the activator solution on the setting times of GGBFS mortars: while shorter setting times were obtained for Na2O contents of 6.5 and 6.34%, longer times were recorded for Na2O contents of 7.32 and 7.15%. A general assessment indicates that the setting times of alkali-activated GGBFS mixtures are more influenced by the composition of the GGBFS and the SiO2/Na2O ratio of the activating solution.

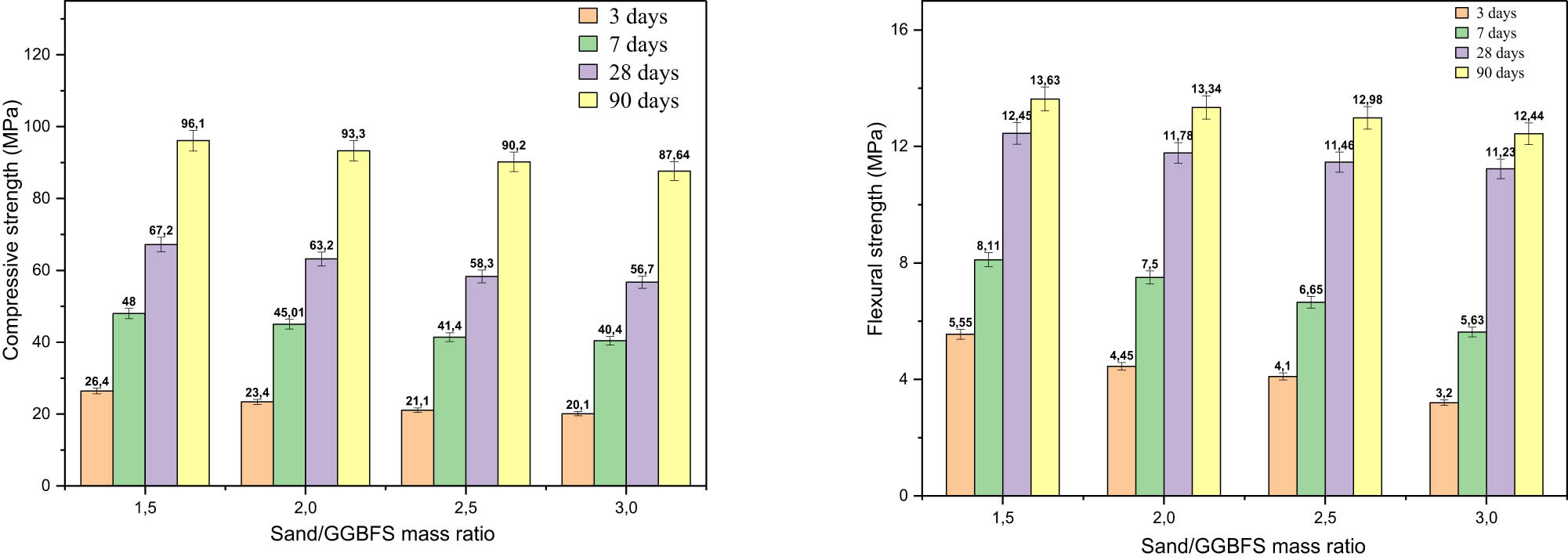

3.2 MS

3.2.1 Effect of sand/GGBFS mass ratio

Figure 8 illustrates the evolution of the MS of GPM by studying the effect of raw material (GGBFS) content on MS at different ages (3, 7, 28, and 90 days).

Effect of the sand/GGBFS mass ratio on compressive strength (left) and flexural strength (right).

Overall, the results showed that CS increased by 48, 28, and 33% after 3–7, 7–28, and 28–90 days of treatment, respectively. In fact, the significant and dramatic improvement in strength after 90 days of curing was primarily due to the ongoing polymerization process, the completion of chemical reactions, and the reduction of porosity, which develops at a low rate during the first few days and gradually increases up to 90 days. In addition, the high calcium oxide content in the GGBFS composition, which reacts slowly with the alkaline solution, produces more gels (C–A–S–H and/or C–S–H). This reaction contributes to the improved CS of the GP-matrix, as reported in several studies [4,5,7,14,25,27]. From Figure 8, it can be concluded that the minimum curing time required to achieve optimal performance for all GGBFS mixtures cured at room temperature is at least 7 days to attain the desired properties. This result is consistent across all types of geopolymer cements [45]. However, curing for 24–48 h may be adequate under elevated temperatures [45]. In general, it is crucial to balance curing time and temperature to ensure optimal performance [1,7,38,45]. In addition, there is an inverse correlation between the MS and the sand/GGBFS ratio where both CS and FS decrease with increasing the sand/GGBFS ratio. The CS reduction is on average 4.74, 2.42, 2.74, and 2.84%, while the FS reduction is 21.95, 15.34, 2.01, and 4.16% when the sand/GGBFS ratio increases by 2, 2.5, and 3, respectively. The findings suggest that a low sand/GGBFS ratio implies a greater presence of reactive species provided by the dissolution of GGBFS, which favours the development of more bonds, thus improving MS. On the other hand, MS of the samples increases by the addition of fine GGBFS particles that provide a large contact surface for hydraulic interactions. They also create a strong geopolymer bond by filling the space between the structures, which results in a transition zone with a denser interface encircling all the sand grains [5,29,33]. The ideal sand/GGBFS mass ratio for enhanced mechanical performance is typically 1.5; however, a ratio of 3 was chosen for two main reasons: (i) for rheological properties and (ii) for economic considerations aimed at reducing the use of raw materials. This choice also facilitates the comparison of strength results found in GP-based GGBFS mortars with OPC according to the recommendations described in the European Standard EN196-1.

3.2.2 Effect of SiO2/Na2O molar ratio

Previous research has indicated that the SiO2/Na2O molar ratio significantly influences the MS of GP products [8,15,44]. As depicted in Figure 9, MS increases proportionally with curing time. Specifically, the results indicate that MS continues to rise from 3 to 90 days of curing when using low SiO2/Na2O molar ratios (1.17–1.23). However, after 90 days of curing, the MS slightly decreases with higher molar ratios (1.29). This can be explained by the fact that lower SiO2/Na2O molar ratios result in higher SH concentrations, which enhance the dissolution of GGBFS aluminosilicates and promote the formation of long-chain GPs over time [7,38,44]. A significant increase in compressive strength at 28 days (approximately 22.28%) was found when the SiO2/Na2O molar ratio was raised from 1.11 to 1.23, and a similar trend was noted for FS. This enhancement in both CS and FS is associated with the increased development of the sodium aluminosilicate hydrate (N–A–S–H) gel phase with each increment in the SiO2/Na2O molar ratio [38]. The N–A–S–H gel serves as the primary binding phase in GP systems [4,5,38]. In addition, a higher molar ratio promotes optimal chemical reactions between silica and alkali activators, reducing the presence of unreacted particles and preventing the formation of excess silica that could negatively affect the strength of the material [44]. Additionally, this ratio leads to reduced porosity and a more refined pore size distribution, resulting in improved mechanical performance [8]. Samples prepared with SiO2/Na2O molar ratios of 1.11 and 1.14 showed high early strength compared with samples with other molar ratios. At the same time, these samples showed a lower ultimate strength than those prepared with SiO2/Na2O molar ratios of 1.17, 1.20, 1.23, and 1.26. This explains why the presence of a high concentration of SH accelerated the dissolution of SiO2 and Al2O3 thus hindered polycondensation by suppressing [4,44]. Sample G-8 (94.04 MPa) exhibits higher compressive strength compared to G-9, G-4, and G-5 and have more N–A–S–H in their structures (Figure 12), but compared to sample G-13, they have less calcium carbonate. The high MS of GGBFS-based GPs is mainly due to the high-quality calcium oxide of GGBFS, which is the basis for the strength improvement due to the formation of C–(A)–S–H gel [4,5,26,27,45]. Moreover, significant amounts of dissolved SiO2 increase when the sodium silicate content in the medley increases. The latter effectively supports the development of long-chain gel phases (N–A–S–H), which enhance MS [15,44]. These results are consistent with the microstructural analysis using SEM-EDX (Figure 13c), which shows that SiO2/Na2O molar ratios of 1.17 and 1.23 result in a denser and more cohesive structure. The decrease in compressive strength when the molar ratio is increased to 1.29 is due to the increase in the SiO2 content by 31.83%, which leads to a decrease in the pH of the solution to a value of 12.41, which negatively affects the reaction kinetics. Figure 9 shows that the flexural strength of GGBFS GPMs for different SiO2/Na2O molar ratios varied between 7.67 and 13.03 MPa. The results show that no noticeable changes in the overall trend of the flexural strength compared to the compressive strength were observed. For GBFS-GPMs, the optimal SiO2/Na2O molar ratio typically ranges between 1.17 and 1.23. Within this range, the balance between silica content and alkali activators supports robust gel formation and minimizes negative effects such as efflorescence or structural weakening due to excess alkalis. The maximum flexural strengths after 28 and 90 days are, respectively, 11.79 and 13.03 MPa for the G-8 mortar. It is observed that the flexural strength results did not much improve at 90 days of cure time, meaning that they reached their highest values at day 28. The flexural strength of GGBFS mortars in the present study is higher than that reported in previous studies [4,16,29], due to the high fineness of GGBFS resulting from the grinding operation undertaken during preparation. In summary, the flexural strength of GGBFS-based GPM, when tested under the same standard (ASTM C348) and identical conditions, is 73.73% higher than that of Portland cement mortar, which reaches a maximum value of 7.5 Map at 90 days [47]

Effect of the SiO2/Na2O molar ratio on compressive strength (left) and flexural strength (right).

3.3 Durability

3.3.1 Water absorption (W abs)

3.3.1.1 Effect of sand/GGBFS mass ratio

Table 4 shows that after 28 days of curing, the water absorption values of GGBFS mortars are less than or equal to 6.18%, regardless of the sand/GGBFS mass ratio, making them acceptable for most applications in the construction sector. A higher GGBS ratio typically leads to a mortar with a more compact and denser structure, resulting in lower porosity and greater durability [38]. Table 4 indicates that the water absorption increases with an increasing sand/GGBFS mass ratio. The overall sand/GGBFS mass ratio does not significantly affect the absorption of the mortar, which is consistent with the findings of several other studies [48]. It can be observed that water absorption decreases by a small and negligible percentage with increasing sand/GGBFS ratio. Mortars prepared with a ratio of 1.5, G-1, showed the lowest water absorption values (W abs) of 5.98%. As the amount of GGBFS increases, the pores become smaller, thus creating a denser geopolymer structure that can contain up to 2,470 kg/m3 of sand and GGBFS. This dense structure necessarily leads to less water absorption. The high amount of GGBFS accelerates the geopolymerization, creating more aluminium silicate gel that makes the geopolymer matrix thicker. In addition, the development of C–S–H gel due to water reactions reduces the porosity of GGBFS. Water absorption is also related to compressive strength. As expected, high water absorption has lower compressive strength.

Water absorption after 28 days of curing of GGBFS mortars

| Mix ID | SiO2/Na2O | Weight ratio | W abs (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sand/GGBFS | SS/SH | |||

| G-1 | 1.17 | 1.50 | 1.24 | 5.98 |

| G-2 | 1.17 | 2.00 | 1.24 | 6.05 |

| G-3 | 1.17 | 2.50 | 1.24 | 6.12 |

| G-4 | 1.17 | 3.00 | 1.24 | 6.18 |

| G-5 | 1.20 | 3.00 | 1.28 | 6.02 |

| G-6 | 1.11 | 3.00 | 1.13 | 4.22 |

| G-7 | 1.14 | 3.00 | 1.18 | 4.90 |

| G-8 | 1.23 | 3.00 | 1.30 | 6.20 |

| G-9 | 1.26 | 3.00 | 1.38 | 5.93 |

| G-10 | 1.29 | 3.00 | 1.44 | 7.03 |

3.3.1.2 Effect of the SiO2/Na2O molar ratio

Table 4 shows the direct impact of the SiO2/Na2O molar ratio on water absorption. The lowest absorption rates were 4.22 and 4.90% for SiO2/Na2O molar ratios of 1.11 and 1.14, which are attributed to the high amounts of SH. This is consistent with previous studies that have demonstrated that samples prepared with high SH concentrations are less susceptible to external attack [48]. In Table 4, it is observed that the average water absorption (6.18, 6.2, 6.02, and 5.93%) was limited to Si/Na molar ratios of 1.17 and 1.26. Furthermore, it was noted that water absorption is directly related to the Na2O and SiO2 contents. In contrast to conventional mortars, GGBFS-based GPMs offer better resistance to water ingress, improving their overall durability [23,27]. This is because of their dense microstructure, which results from the alkali-activated geopolymerization process [4,26,38]. The reaction forms compact aluminosilicate and calcium silicate hydrate (C–S–H) gels, filling pores and reducing permeability [7,10]. Water absorption increased significantly to 7.03% with the increase of the mass ratio (SS/SH) to 1.44, i.e., the SiO2/Na2O molar ratio of 1.29. This was related to the increase in SS content, which caused poor dispersion of Na2O and SiO2 and the formation of a reaction ring on the surface of the slag grains. Consequently, it is essential to carefully evaluate the appropriate molar ratio of the binder composition, processing conditions, water-to-binder ratio, and mortar age when preparing GGBFS mortar [4,10,14,28].

3.3.2 Efflorescence

In the case of alkaline activation of GGBFS, cations are physically absorbed onto the surface structure rather than being structurally incorporated, leading to a high extent of efflorescence [34]. Efflorescence in GGBFS-based GPs occurs when soluble salts, such as alkali hydroxides, migrate to the material’s surface and crystallize, forming visible white deposits [8,34]. One of the main causes of this phenomenon is the excessive use of alkali activators, such as sodium hydroxide or potassium hydroxide, in the mix [8,34]. Moreover, the alkali cations that reach the surface can react with atmospheric CO2, forming alkali carbonates, which further contribute to efflorescence deposits [22,34]. Figure 10 shows the impact of SiO2/Na2O ratios on the amount of efflorescence observed in GGBFS-based geopolymers. The sample P13, with a 1.44 SS/SH mass ratio, exhibits the most surface deterioration due to the addition of large amounts of soluble silicates (SiO2/Na2O molar ratio = 1.29), leading to severe efflorescence as a result of the lowering of the solution’s pH (pH 12.14). Hasnaoui et al. [8] also explained that when an excessive alkali activator is used, the concentration of alkali cations in the pore solution increases. This makes it easier for the cations to migrate to the surface during drying or curing [34]. As moisture evaporates, the cations crystallize at the surface, resulting in efflorescence [8,34]. Furthermore, the retention of excess moisture within the geopolymer matrix facilitates the movement of soluble salts to the surface [34,37]. The geopolymer produced with a high SS/SH ratio has a lower reaction volume during the early reaction steps, with a shorter initial setting time of 32 min (Figure 7b), and a higher reaction volume during the later reaction steps. According to Liu et al. [34], this occurs when the Na+ content is lower (6.34%, Table 3). The efflorescence of samples P11 and P12, which exhibit higher MSs, is greater compared to that of samples P4 and P8. Therefore, an increased amount of alkali activator in the mix raises the concentration of soluble salts, exacerbating efflorescence and affecting both the aesthetic appearance and durability of GGBFS-based GPs [8,34,37].

Effect of SiO2/Na2O molar ratio on the amount of efflorescence of GGBFS mortar.

3.4 Microstructural study

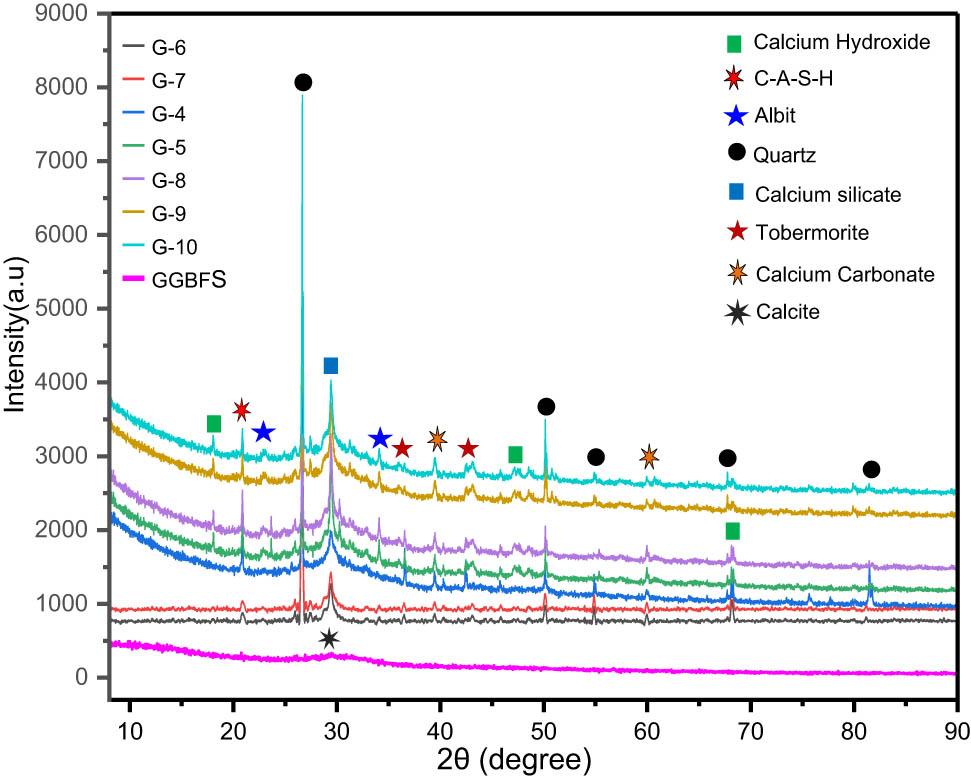

3.4.1 XRD

Figure 11 presents the XRD analysis of the GPs (G-4, G-5, G-6, G-7, G-8, G-9, and G-10 of Table 3), cured for 90 days at 20°C. These analyses show the presence of a large bump at 2Ѳ between 20° and 40°; the latter represents the geopolymer phase where the Si–O–Ca and Si–O–Si(Al) bonds are formed and the tobermorite phase (Ca5Si6O16(OH)2-4H2O) during alkaline activation by dissipating Ca, Si, and Al. From these models, we note that all the samples show strong quartz (SiO2) peaks, with CaCO3, Ca(OH)2 tobermorite, (CaSiO3), and C–A–S–H observed, which means that Ca2+ present in GGBFS reacted to form a C–A–S–H gel.

XRD models of precursor material (GGBFS) and GGBFS mortars for different SiO2/Na2O molar ratios.

In the samples G-5, G-8, G-9, and G-10, new peaks of alite are observed, indicating the presence of a high content of N–A–S–H gel in these mixtures, which resulted in a significant improved in the MS of these samples due to the inorganic network structure of the N–A–S–H gel. Note that this gel gives the alkali-activated materials’ excellent MS and durability, such as thermal stability and high resistance to chloride and sulphate attacks, far exceeding OPC [4,18,21,23,34,44]. It forms due to the reaction between aluminosilicate materials (such as FA or slag) and alkali activators [34,48]. The predominant chemical elements involved are silicon (Si), sodium (Na), and aluminium (Al). These elements participate in the geopolymerization process, forming strong Si–O–Al and Si–O–Si bonds, which are fundamental to the development of (N–A–S–H) gel. In this structure, Na⁺ ions help balance the negative charge of Al [44]. The gel creates a highly interconnected network of strong chemical bonds between silicon and aluminium atoms, providing high bonding strength between the material particles [34,44,48]. This dense and durable structure fills voids and reduces porosity, which enhances the material’s resistance to compressive forces [38]. Additionally, N–A–S–H gel is chemically stable and resistant to aggressive environments, such as acidic or alkaline conditions, making it more durable and less susceptible to chemical attacks such as sulphate corrosion or chloride-induced degradation [48]. There is also the formation of (CaOH)2 in samples G-5, G-8, G-9, and G-10. Due to the dissolution of Ca2+ from GGBFS and its interaction with large amounts of OH in the alkaline solution of these mixtures, Ca(OH)2 subsequently reacts with CO2 in free atmosphere to form CaCO3 [49]. The existence of Ca (OH)2 and CaCO3 together completely dissipates CaO and generates calcium silicates [49]. Additionally, CaCO₃, whether formed through carbonation or added directly as a filler such as limestone, helps improve performance by contributing to the final material’s strength, workability, and thermal stability, as well as by filling voids and reducing crack formation [4,6,49]. However, for the characterization of amorphous phases, other characterization techniques were used, such as ATR-FTIR, SEM, and EDS, which can provide invaluable information about the nanostructure and composition of the gel.

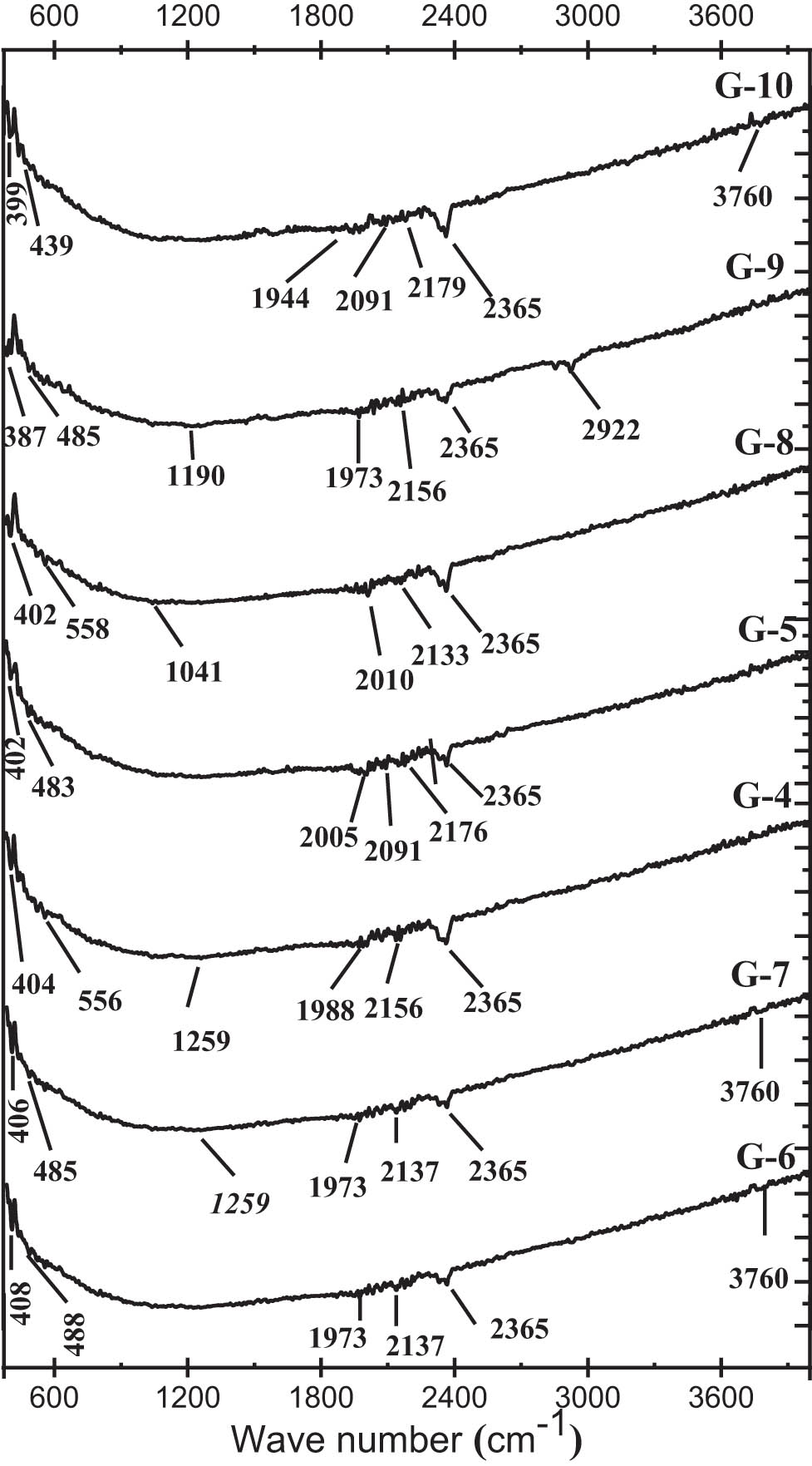

3.4.2 ATR-FT-IR Spectra

Figure 12 displays the ATR-FT-IR spectra for GGBFS and GP with compositions G-4, G-5, G-6, G-7, G-8, G-9, and G-10 from Table 3. Notable observations include prominent peaks at 2,361 and 3,376 cm⁻¹ in the geopolymer spectra, and a peak at 1,650 cm⁻¹ in the GGBFS spectra. These peaks correspond to the stretching and bending vibrations of O–H bands from adsorbed water, which results from the absorption of atmospheric moisture by the GGBFS or geopolymer samples [38]. It is also possible to observe that the strong band at 696 cm−1 present in the ATR spectra of GGBFS, which is assigned to the asymmetric stretching vibration of bending Al–O–Si bonds, moved slightly to lower wave numbers, ranging from 389 to 461 cm−1 of Si–O–Si(Al) bond in the spectra of GP mixtures [50,4]. It describes the generation of N–A–S–H geopolymer gel because of the geopolymerization of raw materials containing calcium carbonate, specifically in the form of calcite. This result agrees with those of Liu et al. [34]. They showed that the displacement of the N–A–S–H gel band results from the substitution of the Si atom by Al in the Si–O–Si(Al) bond, thus decreasing its angle and shifting the main band of the geopolymer system to a lower wavenumbers because the bond strength constant of the Si–O–Si bond is greater than that of the Al-O-Si bond. The principal bond localized at 872 cm−1 and those at 2,109 and 1,428 cm−1 in the IR spectrum of GGBFS correspond to the vibration of CO3 groups exhibited in carbonate minerals [4,6,50]. This is attributed to carbonization, either from the absorption of atmospheric CO2 by diopside during the grinding of GGBFS or from the natural dissolution of CO2 as the magma cools [44]. Additionally, the XRD pattern of GGBS also revealed the presence of CaCO3. A peak around 483 cm⁻¹ is also observed in the IR spectra of the G-6, G-7, G-4, G-5, G-8, and G-9 samples. This band is assigned to the flexing vibrations of O–Si–O groups, indicating the formation of C–S–H gel, which will transform into C–A–S–H gel over time [50]. While samples G-7 does not reveal the presence of such vibration groups that confirm the formation of C–S–H gel; therefore, this shows that the reaction was stopped, due to a decrease in pH. According to Liu et al. [34], C (N) A S H gels forms as a stable product when pH is high in synthetic blends. This observation of microstructure correlates well with the compressive and tensile flexural strengths found and may explain the low values relative to the G-10 mixture. The GP samples G-8 and G-9 showed additional asymmetric Si–O–Si(Al) bond extension vibration groups at 1,041 and 1,190 cm−1, indicating the dense formation of N–A–S–H type gels [50], which increases its density (reducing porosity) and improving its mechanical properties. Moreover, the bands 1,944–1,988 cm−1 and 1,971–1,973 cm−1 are observed for the samples G-4, G-10, G-6, G-7, and G-9, which are the result of asymmetric C–O stretching due to the presence of CaCO3 [50]. Produced as a result of the atmospheric carbonation of leftover sodium ions during the geopolymerization process [44]. All GGBFS samples show peaks in the 2,000–2,200 cm−1 range corresponding to the C–O bond vibration due to carbonate phases (CaCO3, Na2CO3) [50]. This large amount of CaCO3 indicates the prevalence of carbonation in all GGBFS mortars previously observed in the efflorescence (Figure 10). On the other hand, the samples G-4, G-5, and G-8 exhibited the presence of groups of Si–O–Al bending vibrations between 540 and 577 cm−1, which reveals the development of N–(C)–A–S–H gel [50]. This large amount of amorphous and nanocrystalline phases (C–(N, A)–S–H and N–A–S–H) forms high-density microstructures that contribute to improved mechanical properties [34,48].

ATR-FTIR spectra of GGBFS mortars for different SiO2/Na2O molar ratios.

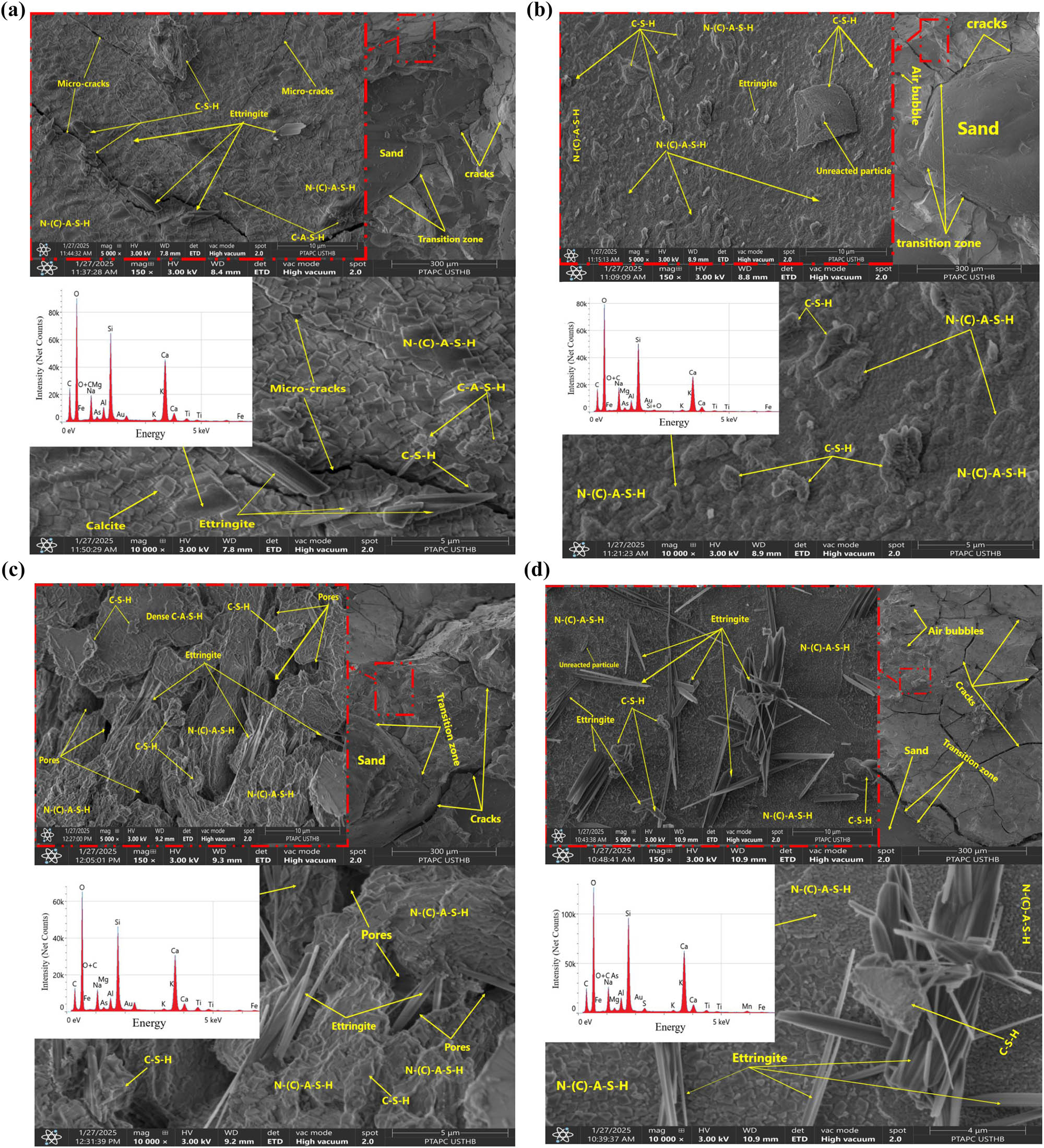

3.4.3 SEM-EDS

SEM combined with EDX analysis was used to investigate the microstructure of the selected GP samples after 90 days of curing. Figure 13(a–d) presents the morphology, with three different magnifications, and the chemical composition of the GP matrix for samples G-6, G-4, G-8, and G-10, all cured at 20°C. Specimens studied by SEM-EDS show that all final products of GGBFS GP are in the form of a dense continuous bulk geopolymer matrix, indicating a homogeneous and compact microstructure with small pores and cracks. Obtaining a dense and consistent microstructure after a long curing period indicates that the geopolymer bond coated all the samples with less pronounced pore spaces [5]. Figure 13b–d shows that even after the mortar breaks, there is strong adhesion between the aggregate and the geopolymer matrix, and the difference in the transition zone between the geopolymer matrix and the aggregate is small, which can be explained by the effect of mechanical loading during compression testing or shrinkage during solidification due to water evaporation. The presence of pores is due to residual air bubbles, polymerization reactions, or water retention in the geopolymer during moulding [26]. Small quantities of ettringite, a key hydration product in cement, contribute significantly to the early strength development of concrete. However, excessive formation can result in DEF, potentially causing expansion and cracking [36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50]. The main elements detected according to the EDS results (Figure 13b–d) are O, Ca, and Si. GP gels are primarily composed of silicon (Si) and oxygen (O), forming the silicate networks that define their structure [1,25,48]. These elements create a silica-rich gel phase, essential to the material’s properties. Additionally, sodium (Na) and calcium (Ca) play crucial roles; sodium, often introduced through activators such as sodium hydroxide, facilitates the geopolymerization process, while calcium, typically sourced from materials such as blast-furnace slag, enhances setting, material’s MS, and workability [7,12,15,34,48]. It can influence the formation of calcium-silicate-hydrate (C–S–H) phases, which are associated with improved compressive strength and resistance to cracking [4,14,49]. The presence of these elements, identifiable through EDS, serves as a hallmark of GP formation [7,25,38,48]. The presence of chemical compounds such as Si, O, Al, and Na (Figure 13–d) is vital for the geopolymerization reaction, resulting in the formation of strong Si–O–Al and Si–O–Si bonds. These components are crucial for producing sodium aluminosilicate hydrate gel (N–A–S–H), with Na+ added to balance the negative charge from Al− [48]. This gel gives the matrix a dense and continuous microstructure after condensation, which can explain the enhancement in MS and durability of the G-10, G-8, and G-4 mixtures [25,48]. Moreover, the presence of adequate Ca in all samples promotes the transformation of N–A–S–H into C–A–S–H. At low pH, this phase behaves like a zeolite, engaging in ion exchange where Ca displaces Na until the available Ca is depleted [34]. The presence of Ca strengthens the bonds between particles, contributing to a more cohesive and durable matrix [48]. The formation of C–A–S–H gel in GGBFS cement plays a crucial role in enhancing the material’s properties [25,48]. Its ability to increase density, reduce porosity, and improve strength and toughness is due to the stable, dense nature of the gel that fills voids [25,48]. The variation in mechanical and physical properties of geopolymer composites with different SiO2/Na2O molar ratios can potentially be explained by these results, which show the difference in the microstructure of GP.

(a) SEM micrographs with EDS analysis of GP mortar corresponding to G-6 mix after 90 days of curing at 20°C, (b) SEM micrographs with EDS analysis of GP mortar corresponding to G-4 mix after 90 days of curing at 20°C, (c) SEM micrographs with EDS analysis of GP mortar corresponding to G-8 mix after 90 days of curing at 20°C, and (d) SEM micrographs with EDS analysis of GP mortar corresponding to G-10 mix after 90 days of curing at 20°C.

4 Conclusion

This study investigated the use of Algerian GGBFS in the form of source material, combined with a NaOH and Na2SiO3 mixture as an alkaline activator, to produce GP mortar. It explored how principal factors, such as sand content and SiO2/Na2O molar ratios in the alkaline solution, affect the fundamental properties of GGBS-based geopolymers. These properties include compressive strength, flexural strength, workability, water absorption, efflorescence, and microstructural configuration. The following conclusions can be drawn from the result of this research:

XRF analysis indicates that the GGBFS powder contains a significant amount of SiO2, CaO, and Al2O3 (over 87%), required for GP synthesis. Additionally, XRD analysis shows that Algerian GGBFS is amorphous and suitable for the geopolymerization reaction.

The GGBFS-based GP geopolymerization under ambient cure conditions is rapid, resulting in reduced setting time and higher compressive strength at an early age. The advance in the age of curing of GGBS mortars increases the strength in compression and tensile bending.

The sand/GGBFS mass ratio was the main factor controlling the workability and setting times of the new GGBFS geopolymer materials. GPMs with high slump and high setting time are assigned to sand/GGBFS ratios of 1.5, while increasing the ratio from 1.5 to 3 significantly improved workability, and setting time, but it slightly decreased the mechanical properties.

The mechanical performance of the GGBFS geopolymer is improved with increasing SiO2/Na2O molar ratio. On the other hand, an excess of activator aggravates the efflorescence phenomenon and degrades the mechanical performance.

The optimum composition was observed with a sand/GGBFS mass ratio of 3.0 and a SiO2/Na2O molar ratio of 1.23, which showed a higher strength of 94.04 MPa.

The attendance of CaCO3 (C–S–H and N(C)–A–S–H) gels contributed significantly to the elevation of mechanical performance.

Microstructural investigations revealed different results: XRD spectra of GGBFS geopolymers indicated the formation of a C–A–S–H gel with CaCO3, which contributed to the rise in high compressive and tensile bending stresses. Then, EDS analysis of GGBFS materials revealed a higher ratio of O, Na, Si, and Ca elements, which means it contains geopolymer gel (C–N–S–H). ATR spectra of GGBFS mixtures indicate the formation of CaCO3 and geopolymer gels (C–A–(N)–S–H, and N–A–S–H). Finally, the morphologies of GPMs based on GGBFS, as observed in the SEM, showed a homogeneous and compact microstructure.

This experimental study confirmed that GPMs based on GGBFS can challenge favourably mortars based on PC from mechanical properties and durability point of view, and moreover, with the advantage of being cleaner because GGBFS is a by-product of metallurgy industry, whereas the production of PC is costly in energy and environment nuisance.

5 Future challenges and opportunities

In the production of geopolymer materials, a significant challenge lies in the variation of mortar formulations, particularly in the activator content, such as alkali hydroxides or silicates. This variability can lead to inconsistent product quality, especially when scaling up production. To address this challenge, it is essential to establish clear standards for GPM formulations. This includes determining optimal ratios of primary components such as GGBFS and activators, along with water content and curing conditions. Implementing strict quality control measures during production is crucial to ensure that each batch meets the required specifications for strength and durability. Additionally, replacing traditional activators with by-products such as waste glass, rice husk ash, and desulfurization dust has been shown to significantly reduce emissions, achieving a reduction range of 50–90%, along with notable cost savings [7,12]. Successfully addressing these challenges will enable GPMs to become a viable, environmentally friendly alternative to traditional cement-based materials in large-scale applications.

Acknowledgments

I would like to extend my heartfelt thanks to the Technical Platform for Physico-Chemical Analysis of USTHB and INZAMAC Algeria – a company specializing in Geotechnical, Topographical Studies, and Laboratory Testing, located in Lotissement Ouled Belhadj, Saoula – Algiers, for their invaluable technical support and the resources provided throughout this work.

-

Funding information: The authors state no funding involved.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

[1] Ashfaq MH, Sharif MB, Irfan-ul-Hassan M, Sahar U, Akmal U, Mohamed A. Up-scaling of fly ash-based geopolymer concrete to investigate the binary effect of locally available metakaolin with fly ash. Heliyon. 2024;10(4):e26331. 10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e26331.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[2] Mathew BJ, Sudhakar M, Natarajan C. Strength, economic and sustainability characteristics of coal ash – GGBS based geopolymer concrete. Int J Comput Eng Res. 2013;3:207–12.Search in Google Scholar

[3] Oyebisi S, Ede A, Olutoge F, Ofuyatan O, Alayande T. Building a sustainable world: Economy index of geopolymer concrete. ISEC 2019 – 10th Int Struct Eng Constr Conf. 2019. p. 1–6.10.14455/ISEC.2019.6(1).SUS-20Search in Google Scholar

[4] Prusty JK, Pradhan B. Multi-response optimization using Taguchi-Grey relational analysis for composition of fly ash-ground granulated blast furnace slag based geopolymer concrete. Constr Build Mater. 2020;241:118049. 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.118049.Search in Google Scholar

[5] Dai X, Aydın S, Yardımcı MY, Lesage K, De Schutter G. Effects of activator properties and GGBFS/FA ratio on the structural build-up and rheology of AAC. Cem Concr Res. 2020;138:106253. 10.1016/j.cemconres.2020.106253.Search in Google Scholar

[6] Zaid O, Abdulwahid Hamah Sor N, Martínez-García R, de Prado-Gil J, Mohamed Elhadi K, Yosri AM. Sustainability evaluation, engineering properties and challenges relevant to geopolymer concrete modified with different nanomaterials: A systematic review. Ain Shams Eng J. 2024;15(2):102373. 10.1016/j.asej.2023.102373.Search in Google Scholar

[7] Madirisha MM, Dada OR, Ikotun BD. Chemical fundamentals of geopolymers in sustainable construction. Mater Today Sustain. 2024;27:100842. 10.1016/j.mtsust.2024.100842.Search in Google Scholar

[8] Hasnaoui A, Ghorbel E, Wardeh G. Optimization approach of granulated blast furnace slag and metakaolin based geopolymer mortars. Constr Build Mater. 2019;198:10–26. 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2018.11.251.Search in Google Scholar

[9] Barbhuiya S, Das BB, Adak D. A comprehensive review on integrating sustainable practices and circular economy principles in concrete industry. J Environ Manage. 2024;370:122702. 10.1016/j.jenvman.2024.122702.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[10] Verma M, Dev N, Rahman I, Nigam M, Ahmed M, Mallick J. Geopolymer concrete: A material for sustainable development in Indian construction industries. Crystals. 2022;12(4):1–24.10.3390/cryst12040514Search in Google Scholar

[11] Chen L, Yang M, Chen Z, Xie Z, Huang L, Osman AI, et al. Conversion of waste into sustainable construction materials: A review of recent developments and prospects. Mater Today Sustain. 2024;27:100930. 10.1016/j.mtsust.2024.100930.Search in Google Scholar

[12] Ikotun JO, Aderinto GE, Madirisha MM, Katte VY. Geopolymer cement in pavement applications: bridging sustainability and performance. Sustain. 2024;16(13):5417.10.3390/su16135417Search in Google Scholar

[13] Yao Y, Hu M, Di Maio F, Cucurachi S. Life cycle assessment of 3D printing geo-polymer concrete: An ex-ante study. J Ind Ecol. 2020;24(1):116–27.10.1111/jiec.12930Search in Google Scholar

[14] Tran TM, Trinh HTMK, Nguyen D, Tao Q, Mali S, Pham TM. Development of sustainable ultra-high-performance concrete containing ground granulated blast furnace slag and glass powder: Mix design investigation. Constr Build Mater. 2023;397:132358. 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.132358.Search in Google Scholar

[15] Huseien GF, Mirza J, Ismail M, Ghoshal SK, Ariffin MAM. Effect of metakaolin replaced granulated blast furnace slag on fresh and early strength properties of geopolymer mortar. Ain Shams Eng J. 2018;9(4):1557–66. 10.1016/j.asej.2016.11.011.Search in Google Scholar

[16] Yang HM, Kwon SJ, Myung NV, Singh JK, Lee HS, Mandal S. Evaluation of strength development in concrete with ground granulated blast furnace slag using apparent activation energy. Materials (Basel). 2020;13(2):442.10.3390/ma13020442Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[17] Le VS, Setlak K. Revolutionizing construction safety with geopolymer composites: unveiling advanced techniques in manufacturing sandwich steel structures using formwork-free spray technology. Coatings. 2024;14(1):146.10.3390/coatings14010146Search in Google Scholar

[18] Duan P, Yan C, Zhou W, Luo W, Shen C. An investigation of the microstructure and durability of a fluidized bed fly ash-metakaolin geopolymer after heat and acid exposure. Mater Des. 2015;74:125–37. 10.1016/j.matdes.2015.03.009.Search in Google Scholar

[19] Ye J, Lazar NA, Li Y. Nonparametric variogram modeling with hole effect structure in analyzing the spatial characteristics of fMRI data. J Neurosci Methods. 2015;240:101–15. 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2014.11.008.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[20] Sarker PK, Kelly S, Yao Z. Effect of fire exposure on cracking, spalling and residual strength of fly ash geopolymer concrete. Mater Des. 2014;63:584–92. 10.1016/j.matdes.2014.06.059.Search in Google Scholar

[21] Lingyu T, Dongpo H, Jianing Z, Hongguang W. Durability of geopolymers and geopolymer concretes: A review. Rev Adv Mater Sci. 2021;60(1):1–14.10.1515/rams-2021-0002Search in Google Scholar

[22] Nkwaju RY, Djobo JNY, Nouping JNF, Huisken PWM, Deutou JGN, Courard L. Iron-rich laterite-bagasse fibers based geopolymer composite: Mechanical, durability and insulating properties. Appl Clay Sci. 2019;183:105333. 10.1016/j.clay.2019.105333.Search in Google Scholar

[23] Chen K, Wu D, Xia L, Cai Q, Zhang Z. Geopolymer concrete durability subjected to aggressive environments – A review of influence factors and comparison with ordinary Portland cement. Constr Build Mater. 2021;279:122496. 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2021.122496.Search in Google Scholar

[24] Kong DLY, Sanjayan JG. Damage behavior of geopolymer composites exposed to elevated temperatures. Cem Concr Compos. 2008;30(10):986–91. 10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2008.08.001.Search in Google Scholar

[25] Yang T, Yang S, Sun Z, Wang S, Pang R. Deterioration mechanism of alkali-activated slag and fly ash blended recycled aggregate concrete under freeze-thaw cycles. J Build Eng. 2025;99:111555. 10.1016/j.jobe.2024.111555.Search in Google Scholar

[26] Ahmad MR, Chen B, Shah SFA. Influence of different admixtures on the mechanical and durability properties of one-part alkali-activated mortars. Constr Build Mater. 2020;265:120320. 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.120320.Search in Google Scholar

[27] Huseien GF, Sam ARM, Shah KW, Mirza J, Tahir MM. Evaluation of alkali-activated mortars containing high volume waste ceramic powder and fly ash replacing GBFS. Constr Build Mater. 2019;210:78–92. 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2019.03.194.Search in Google Scholar