Microstructural and mechanical characterization of Al6061-ZrB2 nanocomposites fabricated by powder metallurgy

-

Priyadarsini Morampudi

, Vuppala Sesha Narasimha Venkata Ramana

Abstract

Al6061-ZrB2-reinforced metal matrix nanocomposites were synthesized through the hot pressed process (PM) with varying the nano ZrB2 content in wt% (0, 0.5, 1, 1.5, and 2) and studied their microstructural and mechanical properties. Mechanical properties such as hardness, compression strength, tensile strength, and yield strength were investigated for the fabricated composites. Field emission scanning electron microscope (FESEM) microstructural characterization of the PM samples revealed a uniform distribution of ZrB2 nanoparticles in the matrix. X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis confirmed the presence of aluminum and ZrB2 particulates in the Al-metal-matrix composites. The incorporation of ZrB2 particles into the Al matrix was shown to significantly enhance the microhardness of the fabricated nanocomposites by 11%. In addition, the incorporation of ZrB₂ reinforcements in the aluminum alloy significantly enhanced the compressive, yield, and tensile strengths of the AMCs. The density of composites was significantly influenced by the presence of ZrB2 particulates. The best composite among the fabricated composites was identified as Al6061-2wt% ZrB2.

1 Introduction

Metal matrix composites provide a distinct set of characteristics that make them highly suitable for an extensive variety of engineering purposes, including aerospace, automotive, marine, construction, and sports industries. These composites continue to be an area of active research and development, aiming to further enhance their properties and explore new applications due to their high strength-to-weight ratio and superior stiffness [1]. AMMCs are developed by mainly two methods such as stir casting and powder metallurgy (PM). PM is one of the most widely used methods for improving the mechanical properties of composites, along with good interaction between the matrix and reinforcement. PM is the best method for synthesizing composites with homogeneous, fine structures, and unique properties [2,3]. The PM approach fabricates metal-matrix composite (MMC) made of aluminum alloys when compared to other conventional fabrication techniques [4]. Various industries, including automobiles and aviation, have used AMMCs for their high specific strength and low density [5]. When compared to Fe alloys, aluminum alloy has many advantages including lower density and greater conductivity [6].

Ravichandran et al. [7] fabricated aluminum as a matrix and graphene and TiO2 as reinforcement in different wt% by using the powder metallurgy route and evaluated the stresses in fabricated composites. Dasari et al. [8] examined the properties of graphene oxide (GO)-reinforced aluminum composites made via powder metallurgy. Aluminum powders (35 μm) mixed with varying GO contents (0.05, 0.1, and 0.2 wt%) were cold compacted, sintered, and analyzed for uniform GO dispersion using scanning electron microscope (SEM)/energy dispersive X-ray (EDX). X-ray diffraction (XRD) and Raman spectroscopy identified the phases within the composite matrix postsintering. The results showed that when GO is evenly distributed, GO-reinforced aluminum composites can achieve hardness values comparable to those of rGO-reinforced aluminum composites. Zamani et al. [9] examined the mechanical and tribological properties of powder-metallurgically manufactured aluminum–graphite (Al-Gr) composites with different graphite contents (3, 5, and 7 wt%). A pin-on-disc tribometer was used to assess wear performance and mechanical attributes such as hardness, tensile, and flexural strength under dry sliding settings. According to the study, 3 wt% Gr provided the optimum combination of tribological and mechanical qualities, including a low wear rate and a smooth, self-lubricating graphite coating. Bodukuri et al. [10] studied the mechanical behavior of B₄C/SiC/Al composites produced via powder metallurgy. Their study showed a significant increase in microhardness with higher B₄C content, and the microstructure revealed a uniform distribution of particles within the metal matrix. Abdizadehet et al. [11] investigated the mechanical, microstructural, and corrosion properties of aluminum reinforced with zircon composites. The highest compression strength was achieved with the specimen containing 5% zircon, at 650°C sintering temperature. Sudhakar Srinivas and Balakrishna [12] developed four-layer functionally graded composites (FGMs) using aluminum, silicon carbide, and magnesium peroxide, fabricated through a sintering process with varying time, temperature, and pressure. FGMs were evaluated for their mechanical, tribological, and microstructural properties, demonstrating impressive compressive strength (315 MPa) and hardness (1.26 GPa micro and 1.87 GPa macro), outperforming standard composites. Taguchi optimization revealed that sintering temperature plays the most significant role in determining mechanical performance.

In this study, Al6061 reinforced with nano ZrB2 with different wt% was fabricated by using the PM route. The microstructural behavior, density, and mechanical properties were investigated from the Al6061/n-ZrB2 fabricated composites.

2 Experimental details

2.1 Materials

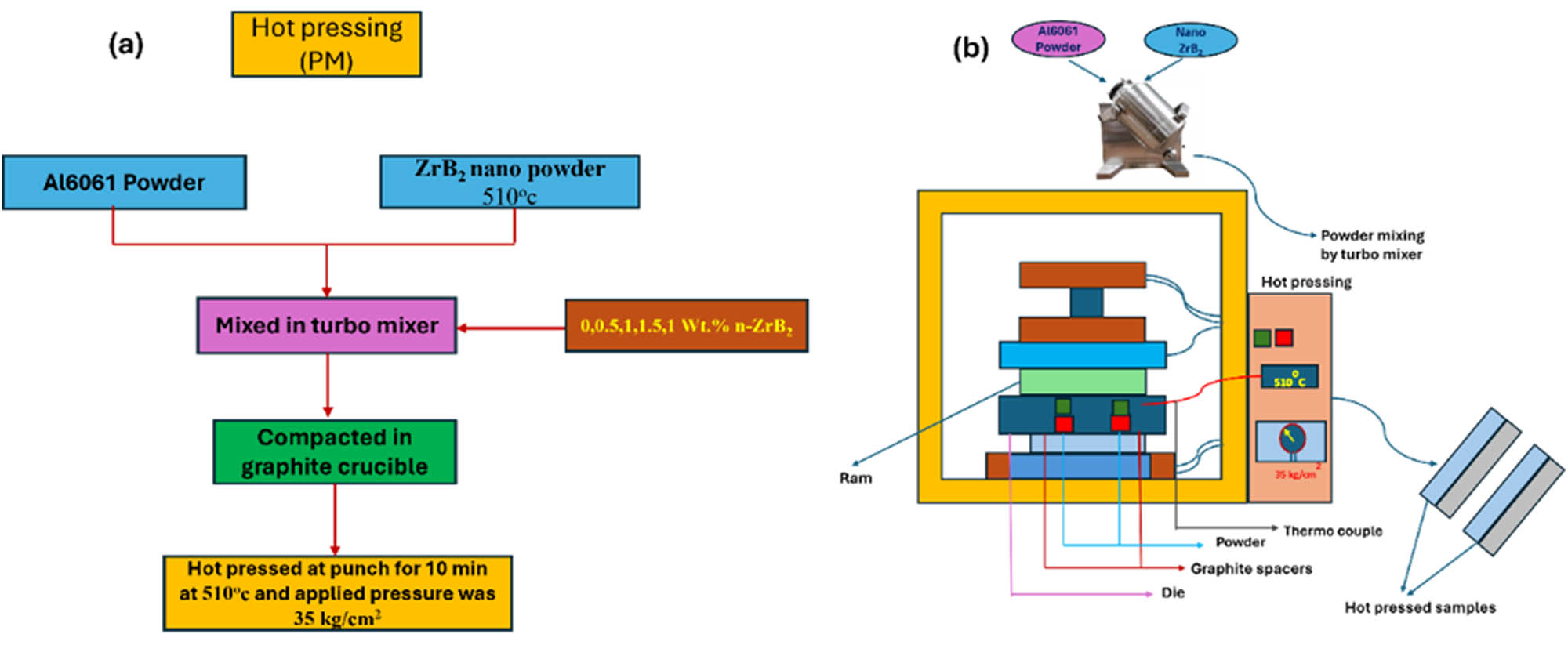

Al6061 is used as the matrix material, and the chemical composition of Al6061 is presented in Table 1. Al6061 powder was obtained from Venuka Engineering Pvt. Ltd., Hyderabad. ZrB2 used as a reinforcement having 50–100 nm particle size was procured from NANOSHEL, Punjab. Al6061 ingots purchased from Vision castings, Hyderabad. Initially, Al6061 and ZrB2 (0, 0.5, 1, 1.5, and 2 wt%) powders are mixed in a turbo mixer, and then the mixed compositions were hot pressed at 35 kg/cm2 and 550°C for 10 min. The final fabricated composites are shown in Figure 1, and the detailed step-by-step fabrication procedure and setup for the hot pressing fabrication method are presented in Figure 2.

Chemical composition of Al6061

| Element | Mg | Fe | Cu | Mn | Si | Al |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Composition (%) | 0.69 | 0.23 | 0.31 | 0.33 | 0.52 | Balance |

Final fabricated composites.

(a) Flowchart of hot pressed processes for Al 6061-ZrB2 nanocomposites fabrication. (b) Hot-pressed unit setup.

2.2 Characterization

The phases present in Al6061 alloy and composite were identified using an X-ray diffractometry at an interference angle of 10°–80° at 15 kV. The average nanocrystallite size was estimated using the well-known Debye–Scherrer formula

3 Result and discussion

3.1 XRD analysis

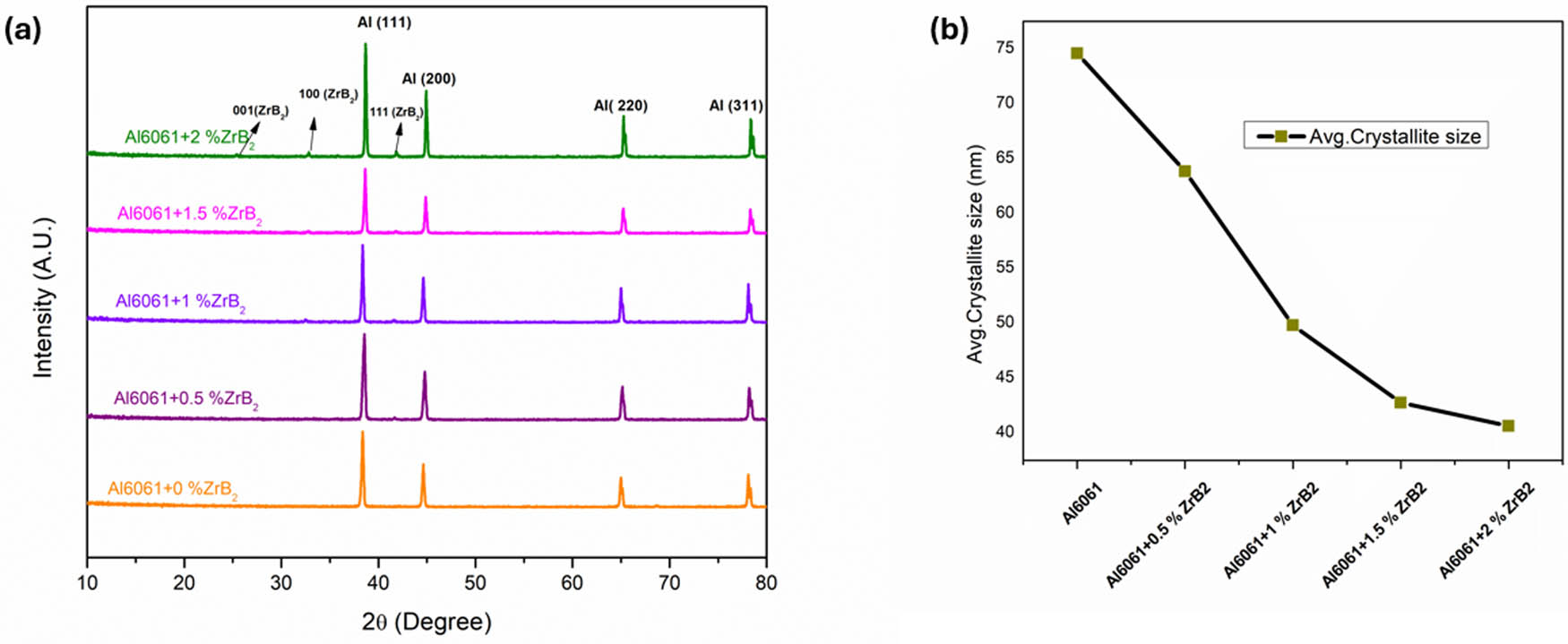

Figure 3(a) illustrates the XRD patterns of nanocomposites with 0, 0.5, 1, 1.5, and 2 wt% ZrB2 fabricated through PM. Al and ZrB2 peaks were identified in the composites, and there are no peaks from the other phases, which indicates the absence of adverse chemical responses between phases. Figure 3(b) shows the increasing weight percentage of ZrB₂ in the Al6061 matrix results in a noticeable reduction in the average crystallite size of the composite. This reduction is attributed to the ZrB₂ nanoparticles acting as nucleation sites, promoting grain refinement during solidification. As the ZrB₂ concentration rises, these particles effectively inhibit the grain growth by pinning the grain boundaries, leading to a finer microstructure. This refined grain structure enhances the mechanical properties, including strength and hardness, as smaller grains provide more grain boundaries that obstruct the dislocation movement, thus strengthening the material.

(a) XRD. (b) Average crystallite size of Al6061-ZrB2 nanocomposites.

3.2 Porosity

Porosity: The pores in the composites are expressed in % of the total volume of the part. It affects the mechanical properties. The porosity was calculated by the following formula and presented in Table 2.

where DR is the relative density.

Values indicating the porosity of composites

| Composition | Porosity (%) |

|---|---|

| Al6061 | 3.73 |

| Al6061 + 0.5% ZrB2 | 3.57 |

| Al6061 + 1 % ZrB2 | 1.7 |

| Al6061 + 1.5% ZrB2 | 3.9 |

| Al6061 + 2% ZrB2 | 2.17 |

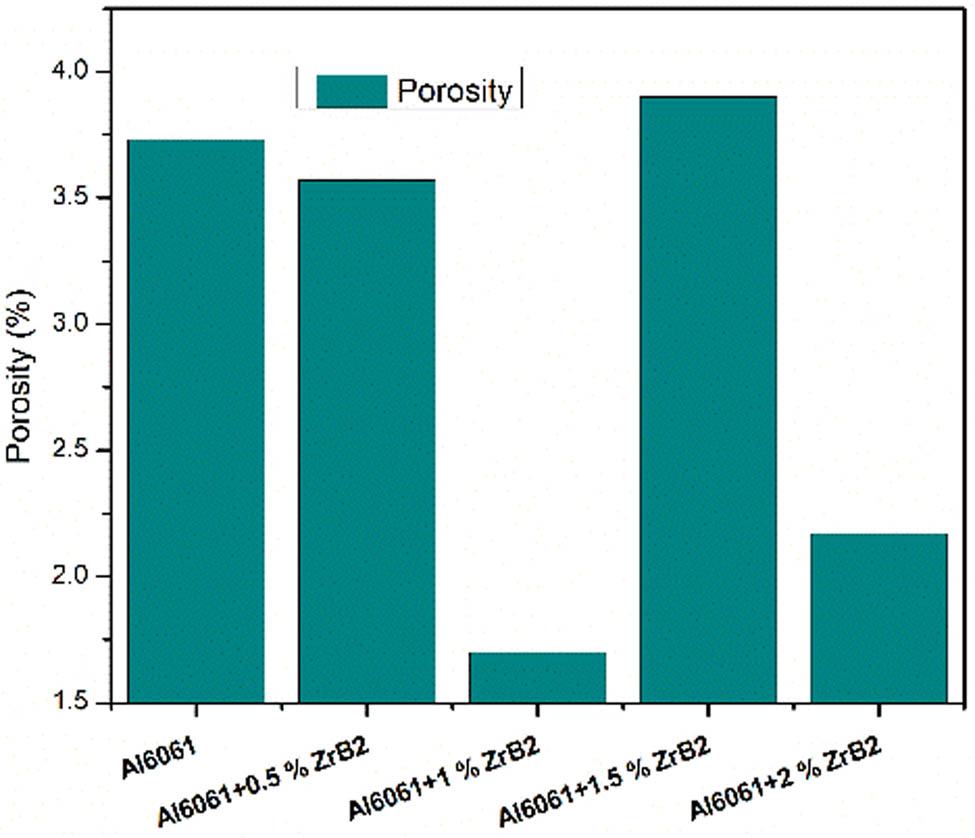

From the previous study, it was observed that the increasing ZrB2 wt% from 0 to 2 in hot pressing increases the density [11]. Figure 4 shows that 1.5 wt% of ZrB2-Al composites exhibits more porosity, which is due to clusters.

Porosity of Al 6061-ZrB2 nanocomposites.

3.3 Microstructural studies

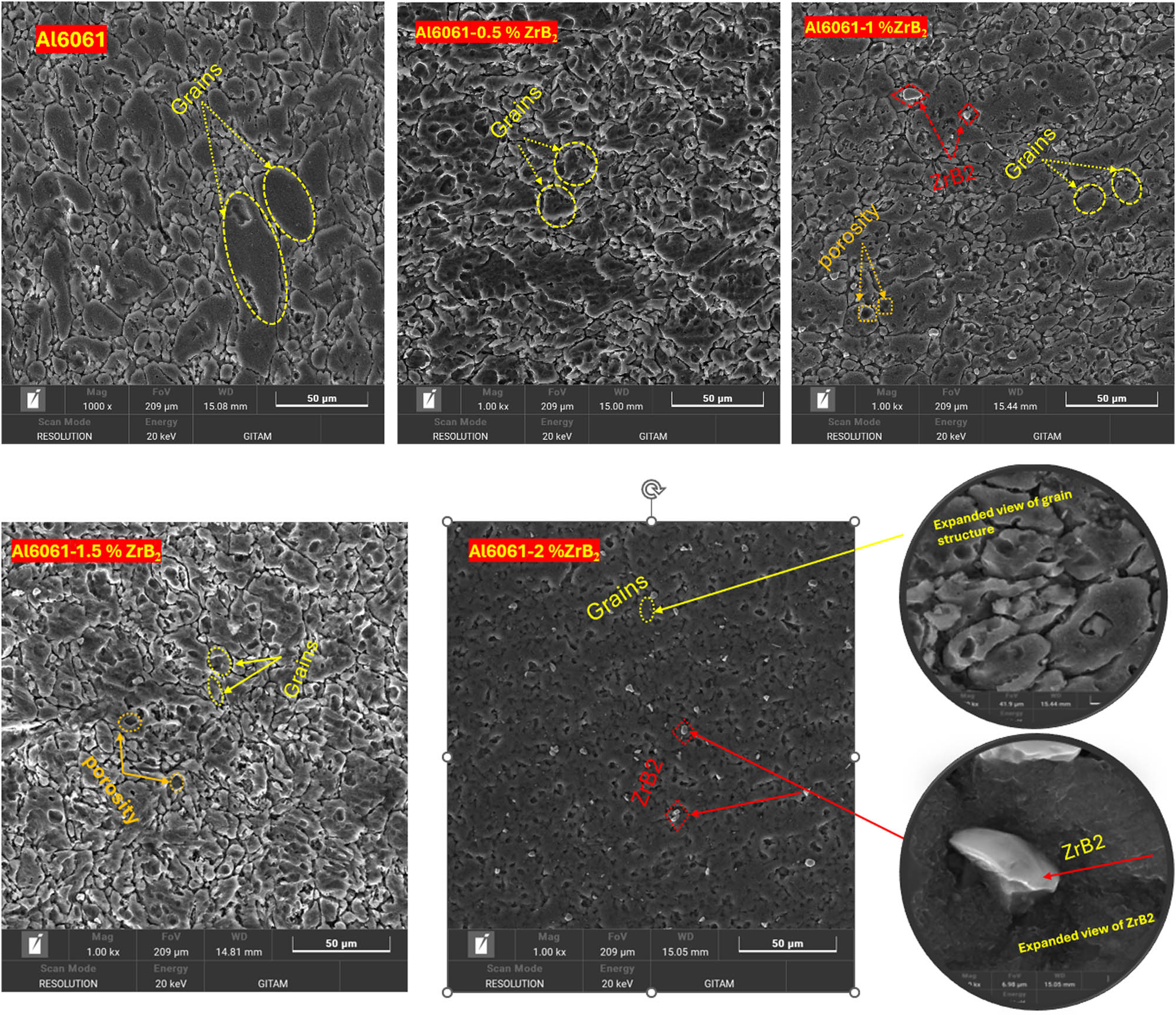

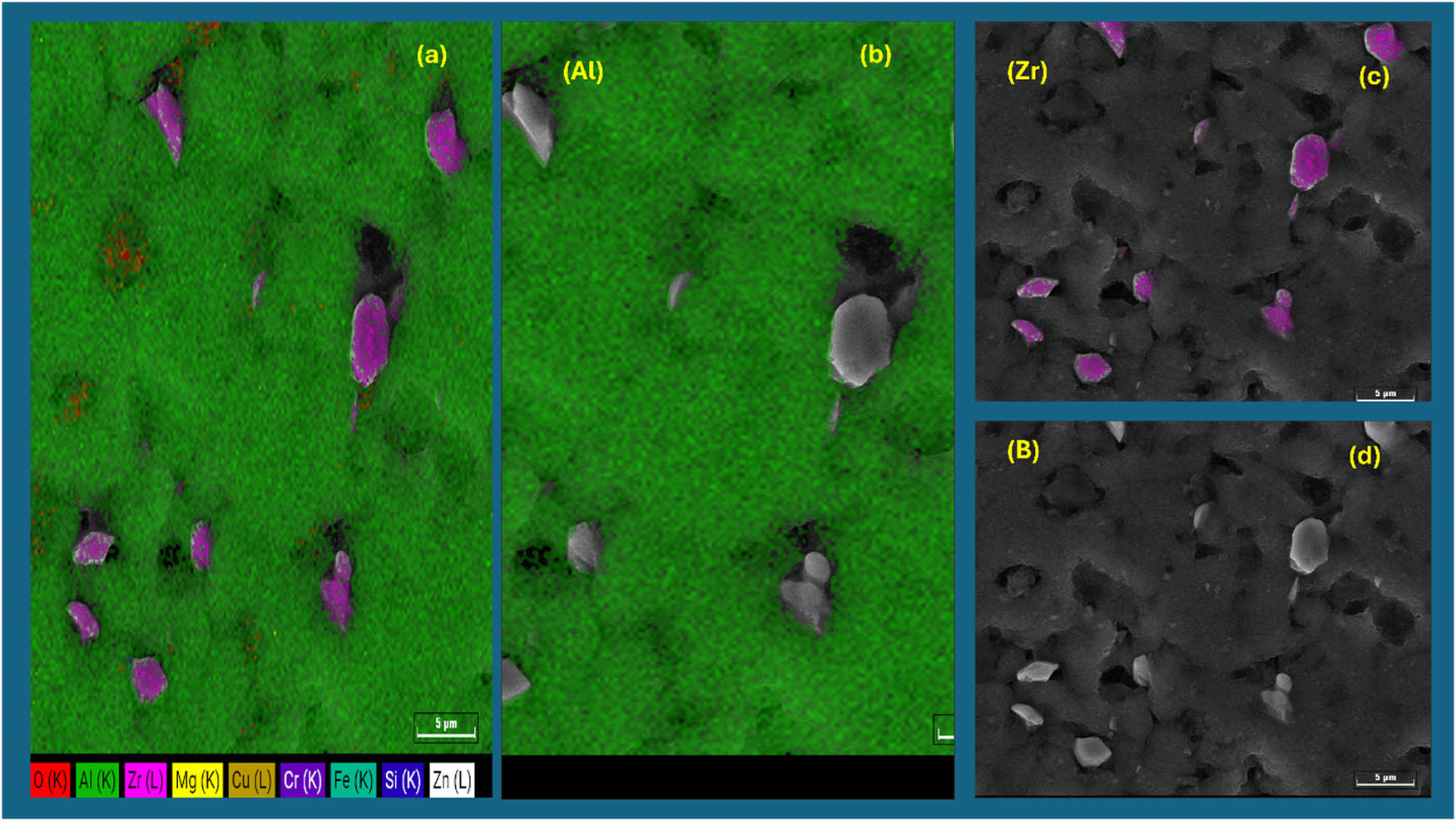

The distribution of the reinforced particles, the existence of pores, and agglomeration in the composites are determined by microstructural analysis, and these factors have a significant impact on the mechanical and physical characteristics of the composites. Figure 5 illustrates the FESEM micrographs of Al6061 and Al/ZrB2 nanocomposites. The SEM images clearly illustrate the even distribution of the matrix and ZrB2 reinforcements within the aluminum matrix. The light gray areas represent the aluminum matrix, while the white spots and clusters indicate the presence of ZrB2 particles. As nano ZrB2 is added to Al6061 alloy in amounts ranging from 0.5 to 2 wt%, grain size decreases as shown in Figure 5, resulting in improved mechanical properties.

FESEM images of Al6061-ZrB2 nanocomposites.

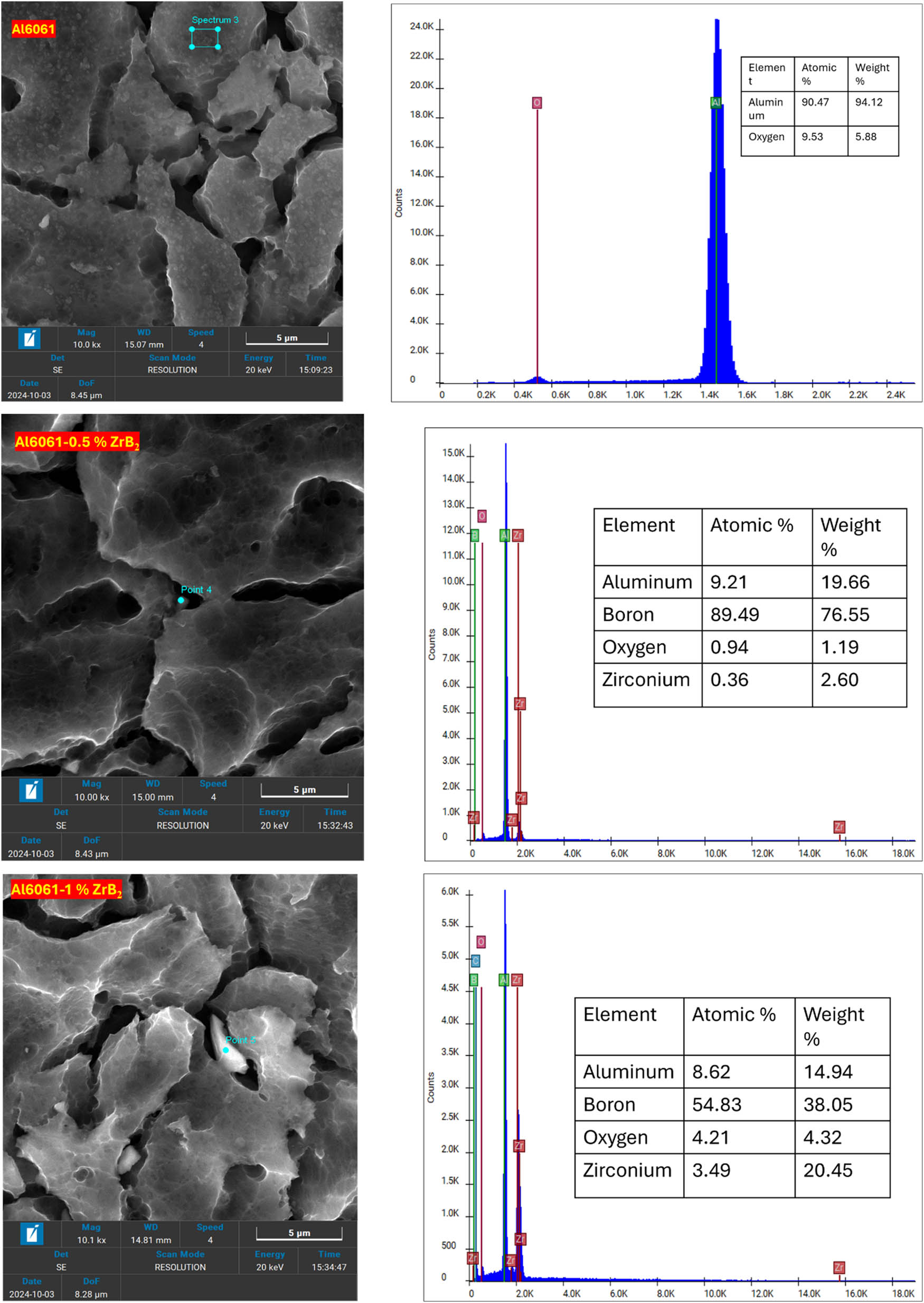

In Figure 6, energy-dispersive X-ray analysis revealed that the composite did not contain any reactive products. Furthermore, EDS analysis showed that ZrB₂ nanoparticles were well dispersed throughout the Al6061 alloy matrix. In contrast, sintered composites exhibited agglomeration of nano ZrB2 and the presence of oxide layers, indicating surface and interface contamination. These oxide layers weaken the bond between the reinforcement and the matrix at contact areas, leading to poorer mechanical properties [14].

SEM EDS of Al6061-ZrB2 nanocomposites.

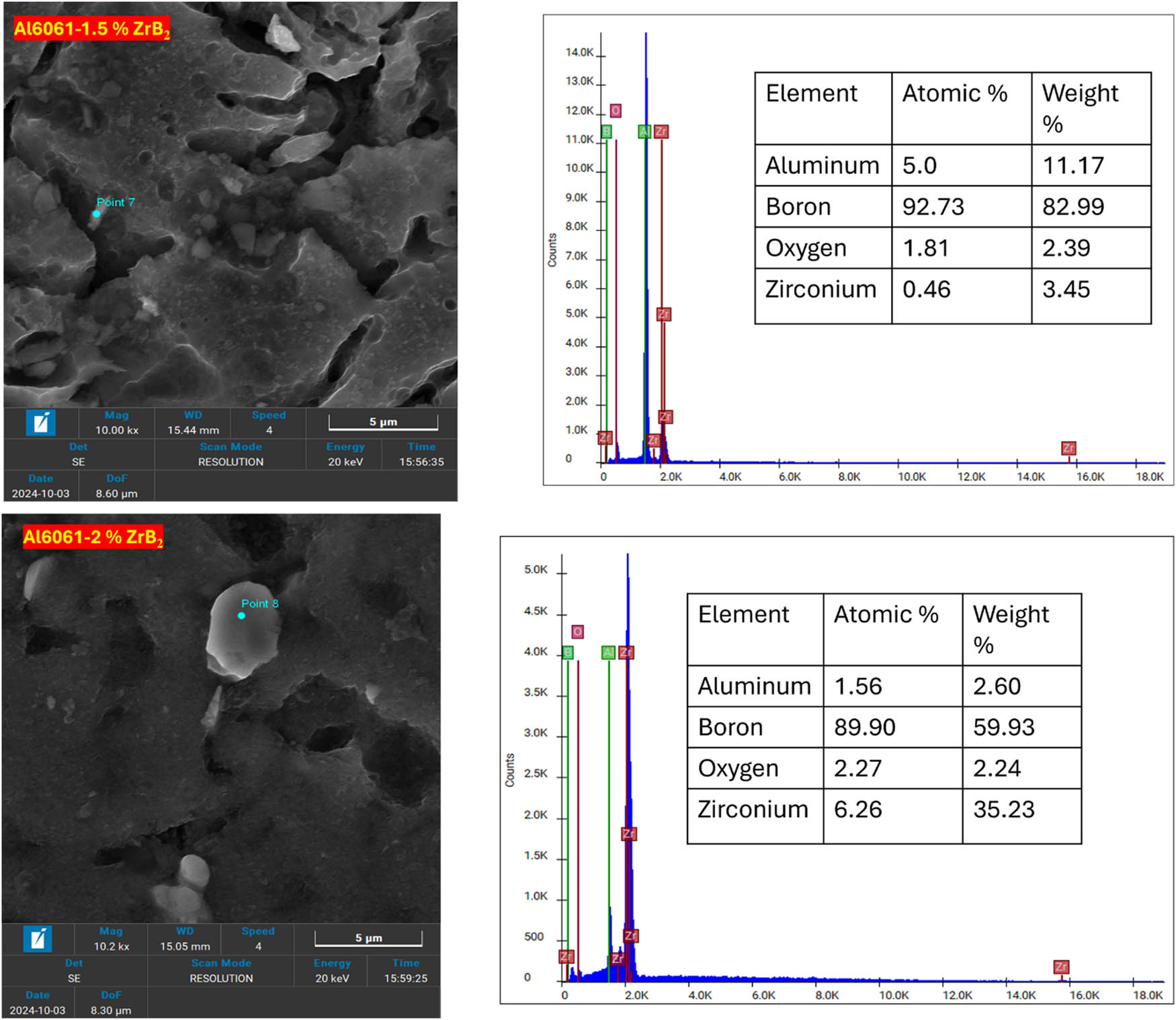

In Figure 7(a), elemental mapping with green and pink colors indicates the distribution of Al and zirconium in the composite, likely showing that the ZrB₂ reinforcement has been well dispersed within the Al6061 matrix. The fact that both boron (from ZrB₂) and zirconium are clearly visible suggests that the ZrB₂ has not decomposed or reacted undesirably during processing, supporting the suitability of the hot pressing.

Elemental mapping of Al6061-2 wt% ZrB2.

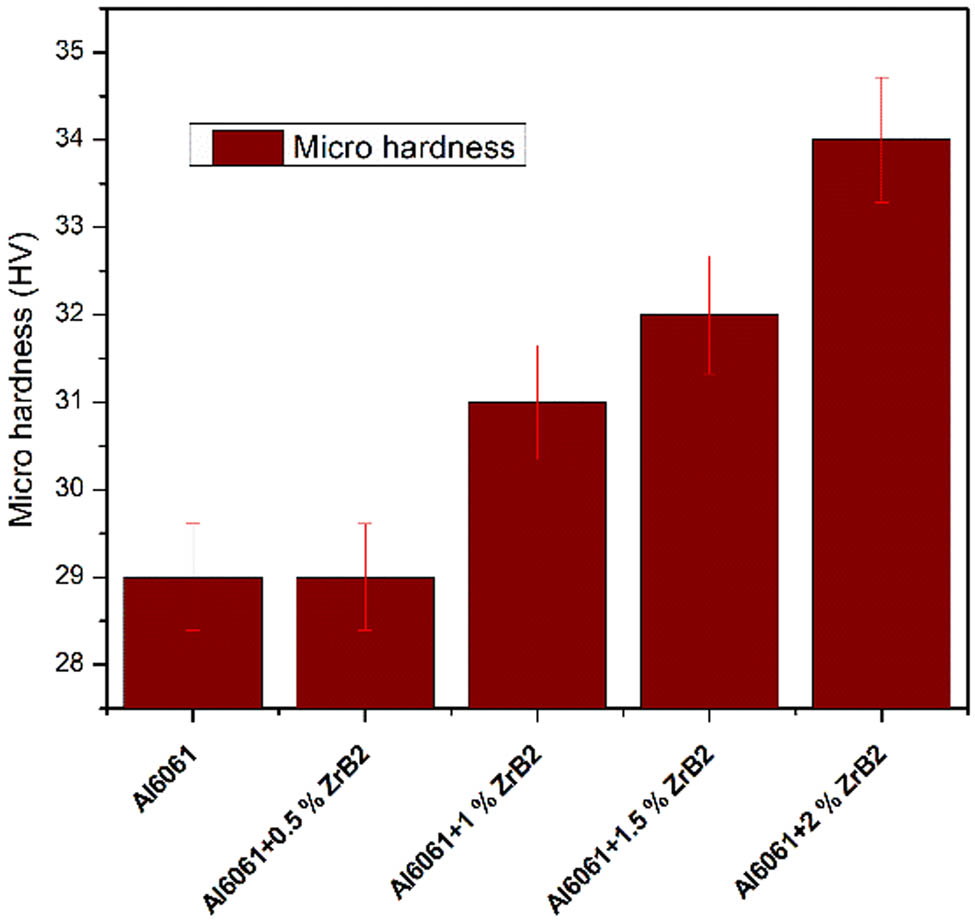

3.4 Micro-hardness

Figure 8 illustrates the micro-Vickers hardness results of the Al6061-ZrB2 composites. Compared to the base alloy, the Al6061-ZrB2 composites have a substantially greater microhardness. During solidification, these ZrB2 particles serve as nucleation regions for new grains and will support grain boundaries. With the inclusion of ZrB2 particles from 0 to 2 wt%, there is an increase in microhardness by restricting the dislocation movement [15]. In this work, ZrB2 serves as a load-bearing element, absorbing the greatest amount of load for plastic deformation by increasing its hardness [16]. When the ZrB2 reinforcement content in the Al6061 alloy was increased from 0 to 2 wt%, there is a significant increase in microhardness (Table 3). The maximum hardness achieved was 34 ± 1 HV at 2 wt% of ZrB2 [17]. The findings show that Al6061 alloy with 2 wt% ZrB2 reinforcement had better surface hardness [18]. It might be because the Al alloy matrix’s pores and spaces were filled with ZrB2 particles [19].

Microhardness of Al 6061-ZrB2 nanocomposites.

Values indicating the microhardness of fabricated composites

| Composition | Vickers microhardness (HV) |

|---|---|

| Al6061 | 29 ± 2 |

| Al6061 + 0.5% ZrB2 | 29 ± 3 |

| Al6061 + 1 % ZrB2 | 31 ± 4 |

| Al6061 + 1.5% ZrB2 | 32 ± 3 |

| Al6061 + 2% ZrB2 | 34 ± 1 |

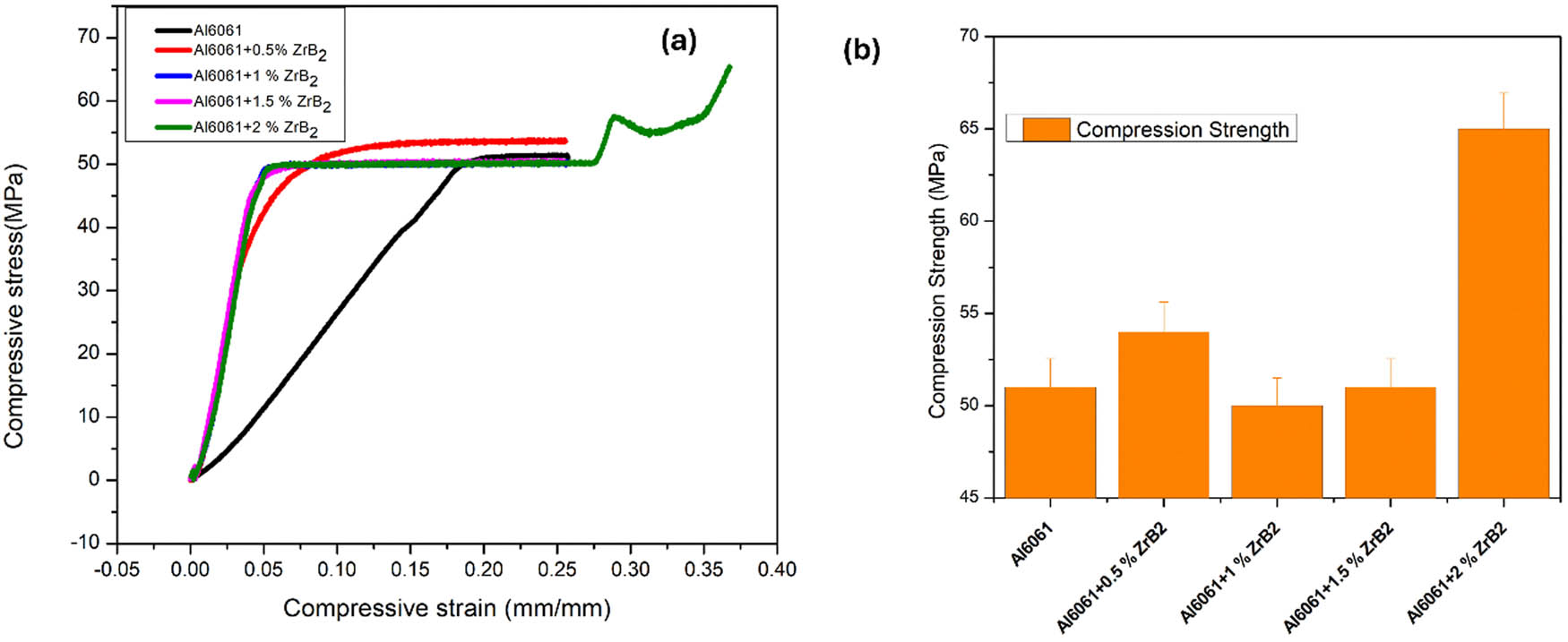

3.5 Compression test

The compressive strength of Al-ZrB2 nanocomposites is greater than the base alloy represented in Figure 9(b), demonstrating the importance of ZrB2 nanoparticles in the prevention of grain growth, which improve the mechanical properties of composites when compared to unreinforced Al6061 alloy samples [20]. In addition, the compressive strength of the Al6061-ZrB2 nanocomposites increased as more ZrB2 content was added. The Al6061 nanocomposite with 2 wt% ZrB2 nanoparticles demonstrated a significant improvement in compressive strength (65 ± 2 MPa). The elastic characteristics are significant in a material’s deformation behavior. ZrB2 has a higher elastic constant than Al, which prevents plastic deformation of the Al matrix and thus boosts the compressive strength of the composite [3]. The enhancement in the strength and hardness of the composites can be attributed to several strengthening mechanisms such as the orowan strengthening mechanism, the dispersion hardening effect, and the load transfer mechanism [21].

(a) Compressive strain and compressive stress. (b) Compressive Strength of Al 6061-ZrB2 nanocomposites.

Figure 9(a) displays the compressive stress–strain curves, which rise as the nanoparticle content increases the material’s strength. The curves show that the compressive strength of the nanocomposites increases with higher nanoparticle content. Specifically, adding 2 wt% of nanoparticles boosts the nanocomposites’ strength by 21.5% compared to the base alloy. The effective interfacial interaction between nanoparticles and the matrix, promoted by ultrasonication, leads to grain refinement. This grain refinement increases the grain boundary area through the pinning effect of nanoparticles, where these boundaries impede dislocation motion during deformation, thereby enhancing the strength of the nanocomposites [22]. Another reason for enhancement in composite’s tensile strength is well-distributed nanoceramic particles and reduced porosity. The use of the powder metallurgy technique results in a homogeneous distribution of ZrB2 particles, reduces air gaps between grains, and causes the low degree of porosity. In addition, thermal stress and high multidirectional grain refinement at the aluminum/ZrB2 interface are significant elements that enhance the strength of the composites [23].

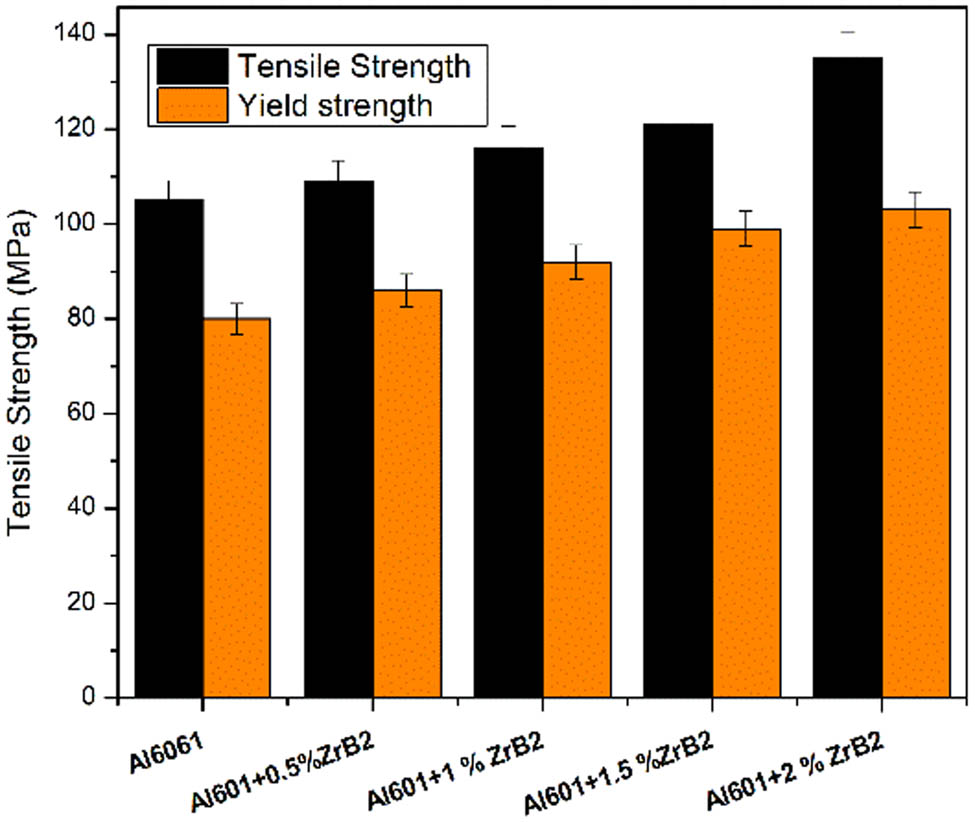

3.6 Tensile strength and Yield strength (YS)

Figure 10 shows how the YS and UTS of Al6061 alloy and Al6061-ZrB2 composites vary. Increasing the ZrB2 wt% in base alloy increased the UTS while decreasing the ductility percentage [16]. Increasing ZrB2 wt% resulted in the ascending trend of yield strength and ultimate tensile strength from 0 to 2 wt% of ZrB2. The higher ZrB2 particle concentration will improve the particles’ interaction with the matrix, which will boost UTS [24]. ZrB2 and Al6061 have different thermal expansion coefficients, which causes dislocations to develop around the ZrB2 particles during solidification. Results in higher stress are required to initiate cracks [25,26,27].

Tensile strength and yield strength of Al 6061-ZrB2 nanocomposites.

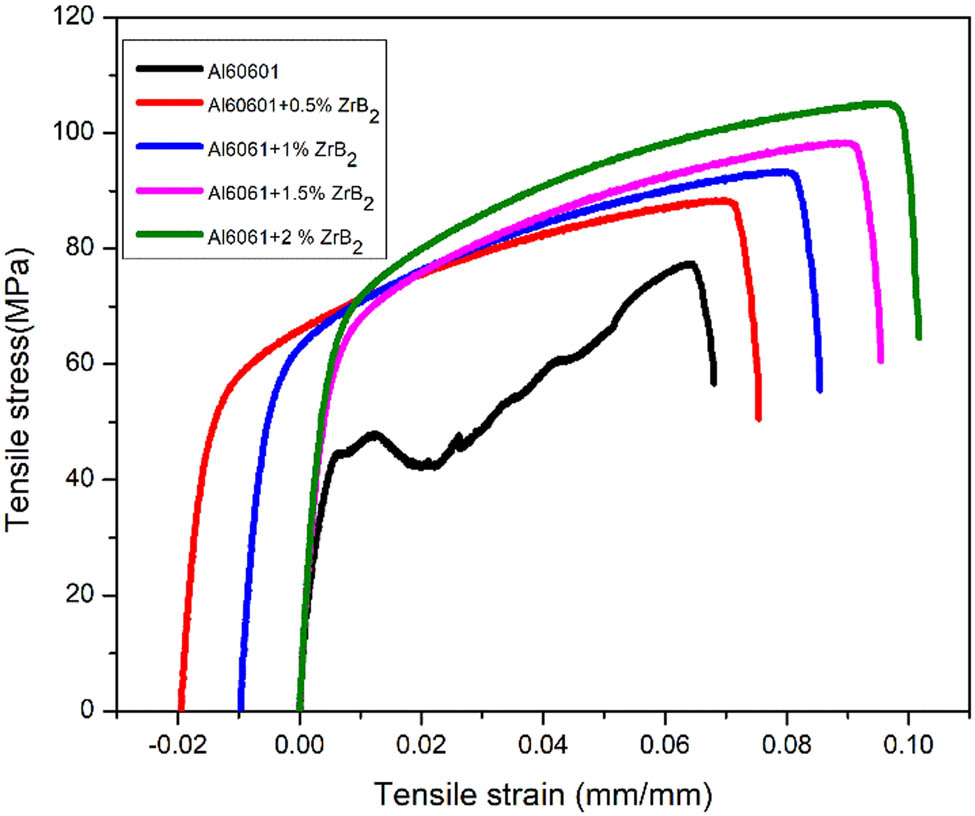

Figure 11 represents the stress and strain curve for Al 6061-ZrB2 nanocomposite. The AA6061-2% ZrB2 nanoparticles composite have ultimate strength and higher yield than pure AA6061. As the ZrB2 content increases, there is a notable rise in tensile strength. The highest increase in strength is observed with 2 wt% ZrB2, and this enhancement can be attributed to the effective load transfer, dispersion hardening, and grain refinement mechanisms facilitated by the nanoparticles. Although tensile strength increases with higher nanoparticle content, the ductility or strain-to-failure decreases slightly, indicating a trade-off between strength and ductility.

Stress and strain curve of Al 6061-ZrB2 nanocomposites.

The consistent improvement in tensile stress with the increased ZrB2 content suggests effective bonding and dispersion of nanoparticles within the Al6061 matrix, enhancing the composite’s ability to withstand higher stresses before failure.

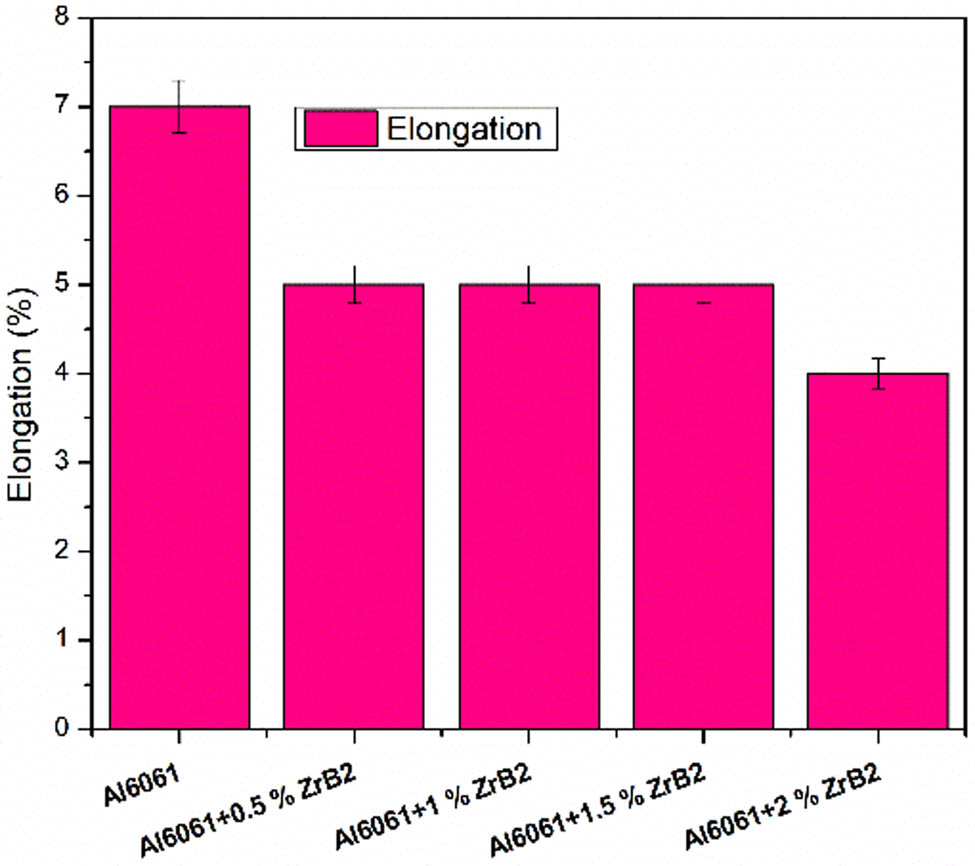

3.7 Ductility

Ductility decreases as reinforcement wt% increases. Figure 12 shows that when the ZrB2 level in the matrix alloy increased, the ductility of the composite decreased. Increased reinforcing may reduce ductility due to the existence of hard ZrB2 particles and grain refinement. The elongation declined due to the addition of ZrB2 reinforcement increases and caused the crack initiation [28,29]. Ductility declined due to the existence of hard ZrB2 particles present in the composites and grain refinement [23].

Ductility of Al 6061-ZrB2 nanocomposites.

4 Conclusions

In the present study, the hot pressing route was used to fabricate the aluminum metal matrix composites. The powder metallurgy method has enhanced the Al 6061 alloy properties with the incorporation of the ZrB2 reinforcement.

The following points were concluded from composites fabricated through the PM route:

The powder metallurgy technique significantly refines the grain structure, ensuring uniform distribution of nanoparticles and effective interfacial bonding between the nanoparticles and the matrix powder.

SEM analysis confirms that the aluminum matrix and ZrB2 reinforcements are uniformly distributed throughout the composite and confirm that the grain size decreases with the addition of ZrB2 ranging from 0 to 2 wt%.

Increasing the ZrB₂ content in the Al6061 matrix reduces the average crystallite size, as ZrB₂ particles act as nucleation sites and inhibit the grain growth. This refined microstructure enhances the composite’s strength and hardness by introducing more grain boundaries that limit the dislocation movement.

The microhardness of the nanocomposites increased significantly from 29 ± 2 HV in the Al6061 alloy to 34 ± 1 HV in the Al6061-2 wt% ZrB₂ nanocomposite. This represents a 17% improvement in microhardness for the Al6061-2 wt% ZrB₂ composite compared to the unreinforced Al6061 alloy.

The Al/ZrB₂ nanocomposite with 2 wt% ZrB₂ exhibited a tensile strength of 135 ± 3 MPa, a yield strength of 103 ± 4 MPa, and a compressive strength of 65 ± 2 MPa, marking respective improvements of 22.2, 22.3, and 21.5% over the unreinforced Al6061 alloy.

Among all fabricated composites, the Al6061-2 wt% ZrB₂ composite demonstrates superior mechanical properties compared to the base alloy.

-

Funding information: The authors state no funding involved.

-

Author contributions: Priyadarsini Morampudi: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, writing – original draft; Vuppala Sesha Narasimha Venkata Ramana: supervision, project administration, and conceptualization; Venkata Satya Prasad Somayajula: writing – review and editing; Sunkara Swetha: writing – review and editing; Kolluri Aruna Prabha: review and editing. All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

[1] Guleryuz LF, Ozan S, Uzunsoy D, Ipek R. An investigation of the microstructure and mechanical properties of B4C reinforced PM magnesium matrix composites. Powder Metall Met Ceram. 2012;51(7–8):456–62.10.1007/s11106-012-9455-9Search in Google Scholar

[2] Pokorska I. Deformation of powder metallurgy materials in cold and hot forming. J Mater Process Technol. 2008;196(1–3):15–32.10.1016/j.jmatprotec.2007.08.017Search in Google Scholar

[3] Baghchesara MA, Abdizadeh H. Microstructural and mechanical properties of nanometric magnesium oxide particulate-reinforced aluminum matrix composites produced by powder metallurgy method. J Mech Sci Technol. 2012;26(2):367–72.10.1007/s12206-011-1101-9Search in Google Scholar

[4] Ashwath P, Xavior MA. Processing methods and property evaluation of Al2O3 and SiC reinforced metal matrix composites based on aluminium 2xxx alloys. J Mater Res. 2016;31(9):1201–19.10.1557/jmr.2016.131Search in Google Scholar

[5] Prabhu B, Suryanarayana C, An L, Vaidyanathan R. Synthesis and characterization of high volume fraction Al-Al2O3 nanocomposite powders by high-energy milling. Mater Sci Eng A. 2006;425(1–2):192–200.10.1016/j.msea.2006.03.066Search in Google Scholar

[6] Min KH, Kang SP, Kim DG, Do Kim Y. Sintering characteristic of Al2O3-reinforced 2xxx series Al composite powders. J Alloy Compd. 2005;400(1–2):150–3.10.1016/j.jallcom.2005.03.070Search in Google Scholar

[7] Ravichandran M, Naveen Sait A, Anandakrishnan V. Al–TiO2–Gr powder metallurgy hybrid composites with cold upset forging. Rare Met. 2014;33(6):686–96.10.1007/s12598-014-0239-xSearch in Google Scholar

[8] Dasari BL, Morshed M, Nouri JM, Brabazon D, Naher S. Mechanical properties of graphene oxide reinforced aluminium matrix composites. Compos Part B: Eng. 2018 Jul;145:136–44.10.1016/j.compositesb.2018.03.022Search in Google Scholar

[9] Zamani NABN, Asif Iqbal AKM, Nuruzzaman DM. Mechanical and tribological behavior of powder metallurgy processed aluminum–graphite composite. Russ J Non-Ferrous Met. 2019 May;60(3):274–81.10.3103/S1067821219030179Search in Google Scholar

[10] Bodukuri AK, Eswaraiah K, Rajendar K, Sampath V. Fabrication of Al–SiC–B4C metal matrix composite by powder metallurgy technique and evaluating mechanical properties. Perspect Sci. 2016 Sep;8:428–31.10.1016/j.pisc.2016.04.096Search in Google Scholar

[11] Abdizadeh H, Ashuri M, Moghadam PT, Nouribahadory A, Baharvandi HR. Improvement in physical and mechanical properties of aluminum/zircon composites fabricated by powder metallurgy method. Mater Des. 2011 Sep;32(8–9):4417–23.10.1016/j.matdes.2011.03.071Search in Google Scholar

[12] Srinivas PN, Balakrishna B. Microstructural, mechanical and tribological characterization on the Al based functionally graded material fabricated powder metallurgy. Mater Res Express. 2020 Feb;7(2):026513.10.1088/2053-1591/ab6f41Search in Google Scholar

[13] Sivamaran V, Balasubramanian V, Gopalakrishnan M, Viswabaskaran V, Rao AG, Sivakumar G. Mechanical and tribological properties of Self-Lubricating Al 6061 hybrid nano metal matrix composites reinforced by nSiC and MWCNTs. Surf Interfaces. 2020 Dec;21:100781.10.1016/j.surfin.2020.100781Search in Google Scholar

[14] Manohar G, Pandey KM, Maity SR. Effect of microwave sintering on the microstructure and mechanical properties of AA7075/B4C/ZrC hybrid nano composite fabricated by powder metallurgy techniques. Ceram Int. 2021;47(23):32610–8.10.1016/j.ceramint.2021.08.156Search in Google Scholar

[15] Boppana SB, Dayanand S, Kumar MA, Kumar V, Aravinda T. Synthesis and characterization of nano graphene and ZrO2 reinforced Al 6061 metal matrix composites. J Mater Res Technol. 2020 Jul;9(4):7354–62.10.1016/j.jmrt.2020.05.013Search in Google Scholar

[16] Dinaharan I, Murugan N, Parameswaran S. Influence of in situ formed ZrB2 particles on microstructure and mechanical properties of AA6061 metal matrix composites. Mater Sci Eng: A. 2011 Jul;528(18):5733–40.10.1016/j.msea.2011.04.033Search in Google Scholar

[17] Mattli MR, Matli PR, Khan A, Abdelatty RH, Yusuf M, Ashraf AA, et al. Study of microstructural and mechanical properties of Al/SiC/TiO2 hybrid nanocomposites developed by microwave sintering. Crystals. 2021;11(9):1078.10.3390/cryst11091078Search in Google Scholar

[18] Kumar CA, Rajadurai JS. Influence of rutile (TiO2) content on wear and microhardness characteristics of aluminium-based hybrid composites synthesized by powder metallurgy. Trans Nonferrous Met Soc China. 2016 Jan;26(1):63–73.10.1016/S1003-6326(16)64089-XSearch in Google Scholar

[19] Meignanamoorthy M, Ravichandran M, Mohanavel V, Afzal A, Sathish T, Alamri S, et al. Microstructure, mechanical properties, and corrosion behavior of boron carbide reinforced aluminum alloy (Al-Fe-Si-Zn-Cu) matrix composites produced via powder metallurgy route. Materials. 2021 Aug;14(15):4315.10.3390/ma14154315Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[20] Abdizadeh H, Baghchesara MA. Investigation on mechanical properties and fracture behavior of A356 aluminum alloy based ZrO2 particle reinforced metal-matrix composites. Ceram Int. 2013 Mar;39(2):2045–50.10.1016/j.ceramint.2012.08.057Search in Google Scholar

[21] Zhang Z, Chen DL. Contribution of Orowan strengthening effect in particulate-reinforced metal matrix nanocomposites. Mater Sci Eng A. 2008;483–484(1–2 C):148–52.10.1016/j.msea.2006.10.184Search in Google Scholar

[22] Callister Jr WD, Rethwisch DG. Materials science and engineering: an introduction. John wiley & sons; 2020.Search in Google Scholar

[23] Mazahery A, Shabani MO. Plasticity and microstructure of A356 matrix nano composites. J King Saud Univ-Eng Sci. 2013 Jan;25(1):41–8.10.1016/j.jksues.2011.11.001Search in Google Scholar

[24] Raja R, Jannet S, Varughese A, George L, Ratna S. Tensile behaviour of aluminium oxide and zirconium dibromide reinforced aluminum alloy 6063 surface composites. Int J Eng Adv Technol. 2020;9(3):2222–4.10.35940/ijeat.C5231.029320Search in Google Scholar

[25] Bhoi NK, Singh H, Pratap S, Gupta M, Jain PK. Investigation on the combined effect of ZnO nanorods and Y2O3 nanoparticles on the microstructural and mechanical response of aluminium. Adv Compos Mater. 2022 May;31(3):289–310.10.1080/09243046.2021.1993555Search in Google Scholar

[26] Morampudi P, Ramana VS, Bhavani K, Srinivas V. The investigation of machinability and surface properties of aluminium alloy matrix composites. J Eng & Technol Sci. 2021 Jul;53(4):210412.10.5614/j.eng.technol.sci.2021.53.4.12Search in Google Scholar

[27] Prakash KS, Gopal PM, Anburose D, Kavimani V. Mechanical, corrosion and wear characteristics of powder metallurgy processed Ti-6Al-4V/B4C metal matrix composites. Ain Shams Eng J. 2018 Dec;9(4):1489–96.10.1016/j.asej.2016.11.003Search in Google Scholar

[28] Kim CS, Cho K, Manjili MH, Nezafati M. Mechanical performance of particulate-reinforced Al metal-matrix composites (MMCs) and Al metal-matrix nano-composites (MMNCs). J Mater Sci. 2017;52(23):13319–49.10.1007/s10853-017-1378-xSearch in Google Scholar

[29] Ravichandran M, Sait AN, Anandakrishnan V. Workability studies on Al+ 2.5%TiO2+ Gr powder metallurgy composites during cold upsetting. Mater Res. 2014;17(6):1489–96.10.1590/1516-1439.258713Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Probing microstructural evolution and surface hardening of AISI D3 steel after multistage heat treatment: An experimental and numerical analysis

- Activation energy of lime cement containing pozzolanic materials

- Optimizing surface quality in PMEDM using SiC powder material by combined solution response surface methodology – Adaptive neuro fuzzy inference system

- Experimental study of the mechanical shear behaviour of steel rebar connectors in timber–concrete structure with leafy wood species

- Development of structural grade lightweight geopolymer concrete using eco-friendly materials

- An experimental approach for the determination of the physical and mechanical properties of a sustainable geopolymer mortar made with Algerian ground-granulated blast furnace slag

- Effect of using different backing plate materials in autogenous TIG welding on bead geometry, microhardness, tensile strength, and fracture of 1020 low carbon steel

- Uncertainty analysis of bending response of flexoelectric nanocomposite plate

- Leveraging normal distribution and fuzzy S-function approaches for solar cell electrical characteristic optimization

- Effect of medium-density fiberboard sawdust content on the dynamic and mechanical properties of epoxy-based composite

- Mechanical properties of high-strength cement mortar including silica fume and reinforced with single and hybrid fibers

- Study the effective factors on the industrial hardfacing for low carbon steel based on Taguchi method

- Analysis of the combined effects of preheating and welding wire feed rates on the FCAW bead geometric characteristics of 1020 steel using fuzzy logic-based prediction models

- Effect of partially replacing crushed oyster shell as fine aggregate on the shear behavior of short RC beams using GFRP rebar strengthened with TRC: Experimental and numerical studies

- Micromechanic models for manufacturing quality prediction of cantula fiber-reinforced nHA/magnesium/shellac as biomaterial composites

- Numerical simulations of the influence of thermal cycling parameters on the mechanical response of SAC305 interconnects

- Impact of nanoparticles on the performance of metakaolin-based geopolymer composites

- Enhancing mechanical and thermal properties of epoxy-based polymer matrix composites through hybrid reinforcement with carbon, glass and steel

- Prevention of crack kinetic development in a damaged rod exposed to an aggressive environment

- Ideal strain gauge location for evaluating stress intensity factor in edge-cracked aluminum plates

- Experimental and multiscale numerical analysis of elastic mechanical properties and failure in woven fabric E-glass/polyester composites

- Optimizing piezoelectric patch placement for active repair of center-cracked plates

- Experimental investigation on the transverse crushing performance of 3D printed polymer composite filled aluminium tubes

- Review Articles

- Advancing asphaltic rail tracks: Bridging knowledge gaps and challenges for sustainable railway infrastructure

- Chemical stabilization techniques for clay soil: A comprehensive review

- Development and current milestone of train braking system based on failure phenomenon and accident case

- Rapid Communication

- The role of turbulence in bottom-up nanoparticle synthesis using ultrafast laser filamentation in ethanol

- Special Issue on Deformation and Fracture of Advanced High Temperature Materials - Part II

- Effect of parameters on thermal stress in transpiration cooling of leading-edge with layered gradient

- Development of a piezo actuator-based fatigue testing machine for miniature specimens and validation of size effects on fatigue properties

- Development of a 1,000°C class creep testing machine for ultraminiature specimens and feasibility verification

- Special Issue on Advances in Processing, Characterization and Sustainability of Modern Materials - Part II

- Surface integrity studies in microhole drilling of Titanium Beta-C alloy using microEDM

- Experimental investigation on bacterial concrete by using Cantabro loss and UPV

- Influence of gas nitriding on the surface layer of M50 NiL steel for aerospace-bearing applications

- Experimental investigation on the spectral, mechanical, and thermal behaviors of thermoplastic starch and de-laminated talc-filled sustainable bio-nanocomposite of polypropylene

- Synthesis and characterization of sustainable hybrid bio-nanocomposite of starch and polypropylene for electrical engineering applications

- Microstructural and mechanical characterization of Al6061-ZrB2 nanocomposites fabricated by powder metallurgy

- Effect of edge preparation on hardness and corrosion behaviour of AA6061-T651 friction stir welds

- Mechanical improvement in acetal composites reinforced with graphene nanotubes and Teflon fibers using loss functions

- Experimental investigation on the mechanical properties of aluminum-based metal matrix composites by the squeeze casting method

- Investigation on punch force–displacement and thickness changes in the shallow drawing of AA2014 aluminium alloy sheets using finite element simulations

- Influence of liquid nitriding on the surface layer of M50 NiL steel for bearing applications

- Mechanical and tribological analyses of Al6061-GO/CNT hybrid nanocomposites by combined vacuum-assisted and ultrasonicated stir casting method

- Strengthening of structures with bacterial concrete for effective crack repair and durability enhancement

- Unique approaches in developing novel nano-composites: Evaluating their mechanical and tribological characteristics

- Load-carrying capacity of highly compact rigid deployable booms

- Investigating the influence of SiC and B4C reinforcements on the mechanical and microstructural properties of stir-casted magnesium hybrid composites

- Evaluation of mechanical and performance characteristics of bitumen mixture using waste septage ash as partial substitute

- Mechanical characterization of carbon/Kevlar hybrid woven 3D composites

- Development of a 3D-printed cervical collar using biocompatible and sustainable polylactic acid

- Mechanical characterization of walnut shell powder-reinforced neem shell liquid composite

- Special Issue on Structure-energy Collaboration towards Sustainability Societies

- Effect of tunneling conductivity of CNTs on the EMI shielding effectiveness of nanocomposite in the C-band

- Evaluation of the effect of material selection and core geometry in thin-walled sandwich structures due to compressive strength using a finite element method

- Special Issue on Sustainability and Development in Civil Engineering - Part III

- The optimum reinforcement length for ring footing resting on sandy soils resisting inclined load

- Special Issue on Advanced Materials in Industry 4.0

- Cross-dataset evaluation of deep learning models for crack classification in structural surfaces

- Mechanical and antibacterial characteristics of a 3D-printed nano-titanium dioxide–hydroxyapatite dental resin-based composite

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Probing microstructural evolution and surface hardening of AISI D3 steel after multistage heat treatment: An experimental and numerical analysis

- Activation energy of lime cement containing pozzolanic materials

- Optimizing surface quality in PMEDM using SiC powder material by combined solution response surface methodology – Adaptive neuro fuzzy inference system

- Experimental study of the mechanical shear behaviour of steel rebar connectors in timber–concrete structure with leafy wood species

- Development of structural grade lightweight geopolymer concrete using eco-friendly materials

- An experimental approach for the determination of the physical and mechanical properties of a sustainable geopolymer mortar made with Algerian ground-granulated blast furnace slag

- Effect of using different backing plate materials in autogenous TIG welding on bead geometry, microhardness, tensile strength, and fracture of 1020 low carbon steel

- Uncertainty analysis of bending response of flexoelectric nanocomposite plate

- Leveraging normal distribution and fuzzy S-function approaches for solar cell electrical characteristic optimization

- Effect of medium-density fiberboard sawdust content on the dynamic and mechanical properties of epoxy-based composite

- Mechanical properties of high-strength cement mortar including silica fume and reinforced with single and hybrid fibers

- Study the effective factors on the industrial hardfacing for low carbon steel based on Taguchi method

- Analysis of the combined effects of preheating and welding wire feed rates on the FCAW bead geometric characteristics of 1020 steel using fuzzy logic-based prediction models

- Effect of partially replacing crushed oyster shell as fine aggregate on the shear behavior of short RC beams using GFRP rebar strengthened with TRC: Experimental and numerical studies

- Micromechanic models for manufacturing quality prediction of cantula fiber-reinforced nHA/magnesium/shellac as biomaterial composites

- Numerical simulations of the influence of thermal cycling parameters on the mechanical response of SAC305 interconnects

- Impact of nanoparticles on the performance of metakaolin-based geopolymer composites

- Enhancing mechanical and thermal properties of epoxy-based polymer matrix composites through hybrid reinforcement with carbon, glass and steel

- Prevention of crack kinetic development in a damaged rod exposed to an aggressive environment

- Ideal strain gauge location for evaluating stress intensity factor in edge-cracked aluminum plates

- Experimental and multiscale numerical analysis of elastic mechanical properties and failure in woven fabric E-glass/polyester composites

- Optimizing piezoelectric patch placement for active repair of center-cracked plates

- Experimental investigation on the transverse crushing performance of 3D printed polymer composite filled aluminium tubes

- Review Articles

- Advancing asphaltic rail tracks: Bridging knowledge gaps and challenges for sustainable railway infrastructure

- Chemical stabilization techniques for clay soil: A comprehensive review

- Development and current milestone of train braking system based on failure phenomenon and accident case

- Rapid Communication

- The role of turbulence in bottom-up nanoparticle synthesis using ultrafast laser filamentation in ethanol

- Special Issue on Deformation and Fracture of Advanced High Temperature Materials - Part II

- Effect of parameters on thermal stress in transpiration cooling of leading-edge with layered gradient

- Development of a piezo actuator-based fatigue testing machine for miniature specimens and validation of size effects on fatigue properties

- Development of a 1,000°C class creep testing machine for ultraminiature specimens and feasibility verification

- Special Issue on Advances in Processing, Characterization and Sustainability of Modern Materials - Part II

- Surface integrity studies in microhole drilling of Titanium Beta-C alloy using microEDM

- Experimental investigation on bacterial concrete by using Cantabro loss and UPV

- Influence of gas nitriding on the surface layer of M50 NiL steel for aerospace-bearing applications

- Experimental investigation on the spectral, mechanical, and thermal behaviors of thermoplastic starch and de-laminated talc-filled sustainable bio-nanocomposite of polypropylene

- Synthesis and characterization of sustainable hybrid bio-nanocomposite of starch and polypropylene for electrical engineering applications

- Microstructural and mechanical characterization of Al6061-ZrB2 nanocomposites fabricated by powder metallurgy

- Effect of edge preparation on hardness and corrosion behaviour of AA6061-T651 friction stir welds

- Mechanical improvement in acetal composites reinforced with graphene nanotubes and Teflon fibers using loss functions

- Experimental investigation on the mechanical properties of aluminum-based metal matrix composites by the squeeze casting method

- Investigation on punch force–displacement and thickness changes in the shallow drawing of AA2014 aluminium alloy sheets using finite element simulations

- Influence of liquid nitriding on the surface layer of M50 NiL steel for bearing applications

- Mechanical and tribological analyses of Al6061-GO/CNT hybrid nanocomposites by combined vacuum-assisted and ultrasonicated stir casting method

- Strengthening of structures with bacterial concrete for effective crack repair and durability enhancement

- Unique approaches in developing novel nano-composites: Evaluating their mechanical and tribological characteristics

- Load-carrying capacity of highly compact rigid deployable booms

- Investigating the influence of SiC and B4C reinforcements on the mechanical and microstructural properties of stir-casted magnesium hybrid composites

- Evaluation of mechanical and performance characteristics of bitumen mixture using waste septage ash as partial substitute

- Mechanical characterization of carbon/Kevlar hybrid woven 3D composites

- Development of a 3D-printed cervical collar using biocompatible and sustainable polylactic acid

- Mechanical characterization of walnut shell powder-reinforced neem shell liquid composite

- Special Issue on Structure-energy Collaboration towards Sustainability Societies

- Effect of tunneling conductivity of CNTs on the EMI shielding effectiveness of nanocomposite in the C-band

- Evaluation of the effect of material selection and core geometry in thin-walled sandwich structures due to compressive strength using a finite element method

- Special Issue on Sustainability and Development in Civil Engineering - Part III

- The optimum reinforcement length for ring footing resting on sandy soils resisting inclined load

- Special Issue on Advanced Materials in Industry 4.0

- Cross-dataset evaluation of deep learning models for crack classification in structural surfaces

- Mechanical and antibacterial characteristics of a 3D-printed nano-titanium dioxide–hydroxyapatite dental resin-based composite