Abstract

Cervical collars are orthotic devices that are recommended for those patients who suffer from neck discomfort, ailments, and trauma. These braces provide stability and support to the neck as well as keep the head in an upright position. Commercially available collars are found to be uncomfortable, restrictive, and inadequately tolerated. The conventional making of a customized collar is a laborious process that involves casting, sculpting, and molding of thermoplastic materials, which may lead to extreme discomfort. Persistent use of these collars may result in deterioration, which could result in frequent visits to the hospital and increased costs. In order to mitigate these issues, this study delved into the design, analysis, and 3D printing of a customized cervical collar prototype. 3D printing helps in the creation of lightweight, customizable, and cost-effective devices, ensuring a comfortable fit and enhancing remedial efficacy. A computed tomography scan of the neck region of a male patient was utilized. This process consisted of transforming the CT scan data of the neck region to STL file format for achieving a 3D CAD model. In order to ascertain the designed model’s strength, the model was subjected to static linear assessment by applying external loads ranging from 50 to 200 N. The stress pattern in the model was dispersed equally. The analytical results conformed to the material strength criteria, i.e., to a maximum stress of 25.448 MPa with a factor of safety of 3. A customized prototype of the cervical collar weighing 60.58 g was 3D printed utilizing polylactic acid, a biodegradable and sustainable material, on a fused deposition modeling-based 3D printer. The substantiated cervical collar prototype is expected to demonstrate better comfort, adjustability, and overall effectiveness compared to conventional off-the-shelf collars, thereby offering promising prospects for enhanced case care and rehabilitation.

1 Introduction

Neck discomfort is one of the most prevalent musculoskeletal disorders that affects humans. In many countries, neck discomfort is a major cause of illness and poor general health. In a study, neck discomfort was shown to be common in people 20 years of age and older. According to the study, neck pain was present in 17.3–23.7% of people [1]. Spinal trauma is caused by falls, sports injuries, and serious traffic accidents; its annual incidence rate is estimated to be between 0.20 and 0.64% [2,3]. Orthoses are devices that help injured people with internal functioning. The main intent of a cervical orthosis is to aid or relieve the neck. An orthosis device is commonly used for body protection, immobilization, mobility restriction, weight-bearing support, movement aid, deformity prevention, and injury prevention. Thus, orthoses are commonly utilized to treat patients with neurological issues affecting the brain, spinal cord, and peripheral nerves in addition to addressing physical dysfunction and handicap caused by muscular disorders such as sprains, fractures, arthropathies, and tendinopathies [4]. Neck immobilization is advised for patients experiencing chronic neck pain. The patient’s neck is immobilized using cervical braces, sometimes referred to as cervical collars or cervical orthosis [5]. Using a cervical orthosis to immobilize the neck is a common therapeutic approach for neck surgeries and injuries [6]. The anatomy of the cervical spine is as complicated as any human body part, and it requires utmost care and planning while designing remedies for any disabilities.

1.1 Cervical spine anatomy

The upper area of the spine, known as the cervical spine (also abbreviated as the C-spine), extends from the base of the head to the thorax at the level of the first vertebra to which a rib is connected. It typically comprises the seven vertebrae, or C1–C7, as shown in Figure 1. Its primary duties include maintaining the relative locations of the brain and spinal cord and supporting the skull. Additionally, it promotes mobility of the neck and head. It creates a passageway via the transverse foramina for the vertebral arteries and veins to transport blood to and from the brain [7].

![Figure 1

7 Unique vertebrae in the cervical spine that support the neck (C1–C7) [8].](/document/doi/10.1515/jmbm-2025-0077/asset/graphic/j_jmbm-2025-0077_fig_001.jpg)

7 Unique vertebrae in the cervical spine that support the neck (C1–C7) [8].

1.1.1 Gross anatomy

While C7, also known as vertebra prominens, deviates from the basic pattern and C1 (atlas) and C2 (axis) have distinct traits, the typical traits of the cervical vertebrae include [7]

small, oval-shaped vertebral bodies,

relatively wide vertebral arch with a large vertebral foramen,

small, triangular vertebral canal,

relatively long, bifid (except for C7) inferiorly pointing spinous processes,

transverse foramina protecting the veins and vertebral arteries.

1.2 Cervical spine movements

The cervical spine is the most flexible region of the spine. The cervical spine can move in one or more of the following ways when the head or neck is moved, as shown in Figure 2 [9]:

Flexion: The chin bends downward as the cervical spine bends straight forward. Neck flexion typically occurs when one is gazing downhill or with the head held straight forward, like when one is seated incorrectly at a computer desk.

Extension: The chin tilts upward and the cervical spine levels or goes straight rearward. It is common to extend the neck when working overhead.

Rotation: The head and cervical spine rotate to one side. In contrast, attempting to look to the side (left and right) or over the shoulder, as while backing up a vehicle, neck rotation is particularly helpful.

Lateral bending: The head moves in the direction of the shoulder as the cervical spine bends to one side.

![Figure 2

Cervical motions shown schematically. The anterior–posterior, proximal–distal, and medial–lateral directions are indicated by the x, y, and z axes in the reference frame, respectively [10].](/document/doi/10.1515/jmbm-2025-0077/asset/graphic/j_jmbm-2025-0077_fig_002.jpg)

Cervical motions shown schematically. The anterior–posterior, proximal–distal, and medial–lateral directions are indicated by the x, y, and z axes in the reference frame, respectively [10].

1.3 Role of the cervical spine

In the head–neck region, the cervical spine performs several functions, including:

Assistance of the spinal cord: The spinal cord is a collection of nerve cells that extends from the brain. The spinal cord passes via a channel in the vertebral column called the spinal canal. It is shielded from the outside pressure by the cervical spine.

Support the head: The cervical spine supports and retains the head in place.

Promotes blood flow to the brain: A vertebral artery located in the transverse foramen of the cervical spine contributes to the blood supply to the brain.

Enables head-neck movements: A variety of neck and head mobilizations are facilitated by the cervical spine and neck muscles [11].

Research indicated that orthoses that provide head support and movement control were beneficial for individuals with motor neuron disease [4]. Patients with weak neck muscles benefited from the orthotics used in the study by Xu et al. [4]. Neck orthoses are used to aid people with persistent neck discomfort, strengthen failing neck muscles, and stabilize and mend the neck following an injury or treatment, all of which can enhance a person’s quality of life and self-sufficiency. The cervical fixation orthosis, developed and introduced by George Cottrell in 1964, has been the standard equipment for postoperative cervical fixation therapy thereafter [12]. Soft and stiff cervical collars are the two main kinds of neck collars. Although the latter offers greater cervical stabilization, soft collars are the more bendable and give the greatest range of motion. On the other hand, it was suggested that the range of motion offered by both kinds of collars in the frontal plane is roughly equivalent [5]. There are three types of traditional neck orthotics: soft neck orthotics are the most basic kind of orthotics, which are made of rubber foam with a coat of cotton wool, the latter comprises of applied bionics and biomechanics shoulder supports, padded mandibular supports, two or four inflexible metal vertical supports, and two occipital supports; the third type is cervical thoracic orthosis, which consists of a support beginning to resemble column orthotics and a hard metal connection connecting the anterior and posterior sections [13]. Orthoses are made using a traditional process that requires quite a lot of time. Additionally, the orthosis’s proportions and shape must be manually adjusted to fit the patient’s physique. Furthermore, it can be difficult to manufacture several bespoke orthoses of the same quality; however, intricate designs can occasionally be carried out. However, orthoses can now be constructed with precise measurements utilizing 3D printing technology. This is made possible by the excellent accuracy of the 3D printers, which substantially makes up for the drawbacks of the traditional method. Therefore, the use of 3D printing technology permits the creation of structures that are difficult to make by hand, and a computer-aided design (CAD) program is used to construct an orthosis with exact numerical values for the measurements [14,15]. It is essential to create new orthotics that consider the body type of the patient and potential therapeutic outcomes. The concept of the new design should simultaneously enhance relief, aesthetics, lightweight manufacture, and more consistent contact pressure to guarantee appropriate neck fixation. Traditional orthotics are made with plaster molds. Low-temperature thermoplastic plates are required when the finished goods are large, costly, and require a lot of labor to produce. Even with the quick manufacturing time, the orthoses lack customized comfort and function and are thick with significant geometric flaws [16,17]. Therapeutic factors need to be evaluated against other factors, including comfort and aesthetic appeal. Cervical orthoses that are currently available in the market have hostile, limited, and poorly accepted long-term use. Orthoses manufactured with 3D printers can be produced in as little as one day, compared to a week or so for traditional orthoses [4]. Additive manufacturing (AM) techniques are becoming more and more popular as a feasible production approach for a range of applications. AM makes it feasible to produce intricate geometries that were either impractical or impossible to fabricate in the past [6]. In this case, AM technology is an effective method for producing and enhancing these patient-specific components [18]. It may be advantageous to build a personalized device rather than a prefabricated orthosis in terms of comfort for the patient as well as clinical outcomes. Upper limb casts were the center of recent research on individualized orthoses, demonstrating the viability of AM in this domain. However, only a few studies have considered this manufacturing technique as a practical choice for the cervical area. This may be related to the intricate ways in which a cervical orthosis must support, avoid immobilizing, or adjust the spine. The therapeutic qualities must also be combined with other components, such as comfort level and visual appeal. Comparable assessments were made on a 3D printed cervical orthosis using fused deposition modeling (FDM) [6]. The diagnosis and intended course of therapy determine the kind of brace that will be recommended. The recommended sort of cervical orthosis must be evaluated, and the finite element analysis (FEA) approach was used to accomplish so. It aided in the designer’s search for the ideal balance between the stability and anticipated life of medical equipment. An FEA of the cervical traction therapy’s biomechanics was done to examine the therapy both with and without neck support. It was demonstrated that to avoid any soft tissue injuries, utilizing neck support is recommended in clinical practice [1]. Customizability is one of the brace’s advantages over a traditional one. Another is that CAD designs can be easily shared across a variety of platforms and then customized by the end-user. Consequently, the design may be modified in accordance with the user's requirements prior to 3D printing, which would significantly increase compliance. This is the main difference from cervical orthoses that are traditionally made using a “one-size-fits-all” method, which is also inefficient financially [19]. In order to provide patients with individualized care, the combination of 3D scanning and 3D printing technology is recommended to make cervical orthoses. Researchers have realized that further research and development of cervical orthoses is required, given the rapid advancement of personalized medicine based on 3D printing technology. On the other hand, there are currently limited study designs and scant clinical data available for cervical orthoses. Orthoses need to be customized to meet each person’s needs to achieve the highest performance results. The role of a cervical orthosis is to assist the head and neck while avoiding unnecessary cervical spine movement. The primary goal of cervical spine support is to maintain the cervical spine in a safe neuroanatomical posture. To prevent the vertebra from impaling vital nerve structures and causing irreversible nerve damage, the cervical spine fixation orthosis was established. It should have the most attractive appearance possible, enhance airflow, and reduce discomfort when worn in the heat. To make sure that the patient’s body is free from the compressive stress caused by the head and neck bone bulge, it also depends on the characteristics of that surface [4].

Ambu et al. [6], however, outlined several problems associated with market orthoses. Furthermore, in the review study, Karimi et al. [20] thoroughly examined the effectiveness of several types of neck orthoses. Additionally, drawbacks such as skin rash, atrophy of the muscles, infections that loosen pins, and difficulty swallowing were observed. Pain, discomfort, and odor were also some of the issues recorded [21,22]. Patients with burn wounds were given neck slit models by Visscher et al. [23]. One advantage of this type of 3D printed orthosis was how easy it was to modify certain parameters as the patient healed. An innovative Hemp-Bio Plastic composite with antibacterial properties was employed by Ambu et al. [6]. Using computer tomography, the patient’s neck could be precisely scanned, and following picture manipulation, a 3D model was obtained. After that, the authors used FEA to print a light cervical orthosis with an elliptical hole pattern, which proved to be superior to a honeycomb design. Even with the sanitary surface, its design was still inflexible. Ankle discomfort will result from inflexibility. There is a similar limitation to both approaches [1], and the models do not take dressing activity into account. There is no designated area on the orthosis where the patient can remove it. However, it was noted that 3D-printed orthoses are more comfortable than ones that are available in the market since they fit the patient’s unique anatomy and have a design that solves the odor issue. The second benefit has to do with being smaller and lighter. Time and money spent on production are crucial factors. FDM printed orthoses can be fabricated in a few days, and the creation of new filaments improves their mechanical properties. In the stationary mode, the FLEX printed model is sufficiently sturdy to immobilize the neck during the early stages of therapy, but it may also slightly bend if the patient applies a certain force during the latter stages of the procedure. As a result, it helps to lessen muscular spasms and begin bending the neck and using the neck muscles gradually. The design is suitable for daily use by people who often use computers and have poor neck posture; they may use it during working hours [24]. The cervical orthotics design, development, material qualities, and mechanical strengths have all been assessed and analyzed in the suggested study. The bespoke cervical orthosis was made to work as best it could by choosing the right configuration for the job and improving airflow for more comfort. PLA filament was used for printing the cervical orthosis. The primary factors that led to this decision were the filament’s sustainability, light weight, enhanced mechanical performance, superficial finish, and, most importantly, its antibacterial qualities [6,25].

The digital 3D model of the item that needs to be created must exist for any AM process to function. Regarding AM-based medical applications, the process of patient-tailored device or product creation involves “reverse engineering” the patient to recreate his or her anatomy and then developing orthoses, prostheses, or surgical guides. After obtaining the digital model, the appropriate material and additive manufacturing procedure are chosen [26]. This study reported on the creation of a customized lightweight neck orthosis. The FDM method was used to print the model. FEA was used to evaluate and adjust the form of the orthosis. For the construction of the orthosis, the soft polylactic acid (PLA) filament was selected. This filament has the ability to bend in a flexible manner. This type of feature, in contrast to other materials, enables the model to stretch it while wearing it. The patient can easily put on and take off the device because of a special section behind the orthosis that holds the Velcro used mostly for bracing. Beginning with computer tomography (CT) images of the neck anatomic region provided by a willing participant, the study’s goal was to rebuild the relevant portion. The following stage involved modeling the personalized cervical orthosis using CAD, using the repaired neck as a model. To examine the suggested geometrical configurations worldwide, FEA was used to numerically evaluate the resulting models. Eventually, FDM was employed to create the prototype of the intended cervical orthosis using the advanced composite. FDM technology presents several kinds of opportunities in the design of a cervical collar prototype for 3D printing [27]. Cervical collars are an essential medical equipment that immobilize and support the cervical spine; however, the current production methods usually lead to limitations in terms of comfort, cost-effectiveness, and personalization. An uncomfortable fit might arise from the incapacity of conventional techniques to tailor collars to each patient’s unique needs. Customized orthosis devices are designed to fit each patient’s specific anatomy, beyond the constraints of prefabricated prostheses. The development of 3D printing and 3D imaging software has made it feasible to produce and utilize medical devices that are tailored to specific individuals [28]. Moreover, the high tooling costs associated with conventional manufacturing techniques hinder design innovation and small-scale production. FDM technology offers a viable answer to these issues by enabling the fabrication of customized cervical collars with improved fit, comfort, and utility. However, several technological and design challenges must be fixed before 3D printing’s full potential can be realized. Enhancing material selection and printing settings is necessary to ensure the production of strong, biocompatible, and light collars. Additionally, the design of the collar must balance the immobilization requirements, patient comfort, and aesthetics, considering aspects like ventilation, adjustability, and cleaning simplicity. The goal of this research is to design, analyze and print a cervical collar prototype that utilizes FDM technology and gets beyond the limitations of traditional production methods The suggested prototype seeks to overcome these obstacles like discomfort, weightiness, and not being waterproof, to show how additive manufacturing may advance the development of cervical spine immobilization medical devices, opening the door to more individualized and affordable healthcare solutions.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Additive manufacturing

With AM, digital files were used to create three-dimensional solid items through 3D printing [14]. In the healthcare sector, 3D printing discovers new applications every year that improve and save lives in ways that were unthinkable just a few years ago. One of the primary direct applications of 3D printing in the fields of surgery and medicine is the ability to precisely determine or modify the size of orthosis or prosthetic component parts prior to fabrication. AM aims to customize orthoses, braces, and prostheses, and allows for the quick prototyping of new designs or equipment improvements [29]. According to Negru et al. [30], AM has several benefits and seeks to reduce costs, streamline challenging processes, and quicken implementation. An AM technique called FDM is utilized in the medical industry to make molds for implantable devices and other medical equipment. In this procedure, plastic filament is melted and then directed via an extrusion nozzle. It has been shown that FDM is appropriate for producing cervical orthosis, which needs to be both aesthetically pleasing and functionally exact. However, there are still issues in obtaining precise dimensions and surface qualities [1].

2.2 Materials

The selection of materials for 3D-printed orthoses depends on several critical factors, including biocompatibility, mechanical strength, and durability. Potential alternatives to PLA include polyethylene terephthalate glycol, thermoplastic polyurethane, thermoplastic elastomers, and medical-grade resins. In recent studies, researchers have explored various materials for the fabrication of neck orthoses. One study employed a PLA/hemp composite in 3D-printed neck orthoses, demonstrating enhanced stiffness and improved thermal comfort around the neck. Another study utilized acrylic styrene acrylonitrile (ASA) via a Stratasys FDM printer to produce orthoses, highlighting mechanical robustness and satisfactory surface finish. PLA is a biodegradable material and a sustainable alternative with several benefits. It comes from the fermentation process of polymerizing lactic acid as a monomer, which is normally sourced from renewable sources high in starch (such as sugarcane and sugar beets) [31]. Because of its simplicity of use, wide temperature range for extrusion (180–210°C), and sandable finish, this filament is popular for domestic 3D printing [32]. Since thermoplastics like PLA liquefy rather than burn, recycling and molding them are made easy [1]. As PLA is bioplastic and non-toxic, it is widely used in the field of biomedicine [33]. Moreover, PLA is recyclable in the same way as other thermoplastic polymers [34]. Nonetheless, regardless of its widespread utilization, PLA does possess certain drawbacks, consisting of weak impact resistance, limited elongation at the breakpoint, and a greater price compared to easily accessible commodity plastics. However, by mixing PLA with other polymeric materials or fillers, these limits can be overcome. PLA may be made to become a ductile polymer to overcome its brittleness. It has been demonstrated that natural rubber works well to increase the durability of PLA-based printing filament, making it appropriate for use in 3D printing [1].

2.3 Design of a cervical collar

Three steps make up the design process. First, the design process involves gathering data and digitally reconstructing the human neck using CT scan data. Next, the modeling and design were performed using Autodesk Fusion 360. The final phase was the evaluation of the neck model. The final model was then created.

2.3.1 Acquisition of data and human neck digital reconstruction

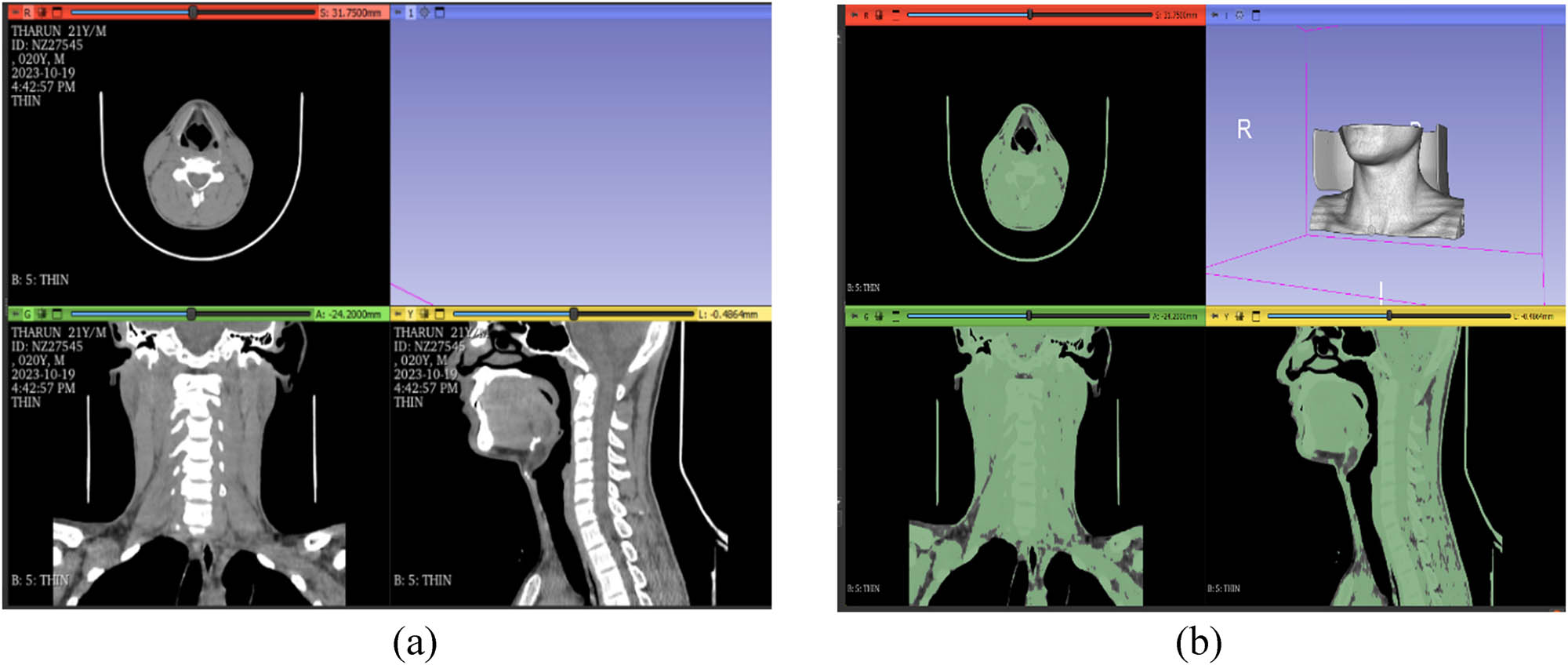

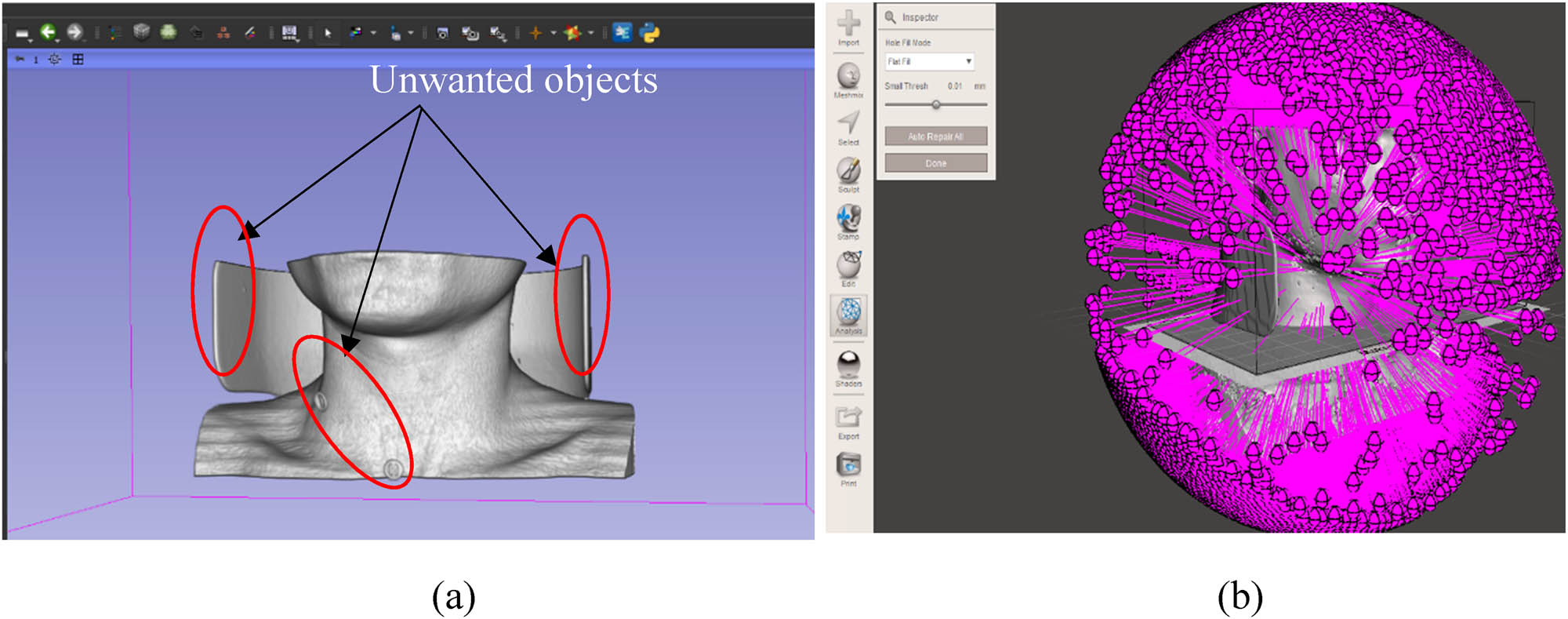

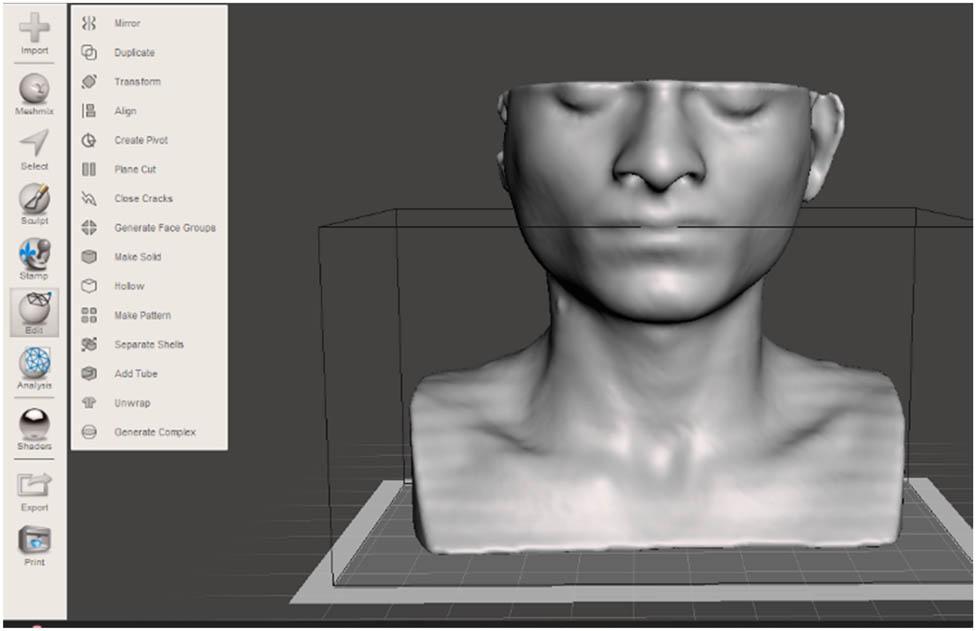

Using laser or 3D photogrammetric scanners, a digital depiction of an external human body component can be obtained. The neck region of a human body is scanned using 3D scanning technology to collect point clouds of data that serve as an input for modeling. Here, the acquisitions of a CT scan may also be used to create a 3D reconstruction [6,35]. This study involved a 22-year-old male patient with chronic neck pain persisting for over five years. CT scans of the cervical region were obtained using a Siemens SOMATOM Emotion 16-slice CT scanner at a certified imaging center to ensure precise anatomical accuracy, as shown in Figure 3(a). CT scanners save scanned data as images in the Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine (DICOM) format. 3D Slicer is an open-source software that shows image volumes as three-dimensional objects using a volume rendering visualization tool [36]. The collection of neck photos was divided by threshold values that vary. Specifically, the first segmentation definition made use of the “thresholding” filter. The lower and upper criteria were used to define the object. The threshold function is chosen to turn the masked region into a 3D model by setting it to a changeable intensity range for the mask, as shown in Figure 3(b). The threshold values in this case were set between 5.21 and 2796.62. As shown in Figure 4(a), the model was modified to eliminate extra geometries and noisy components like bones, internal organs, or clothing using Segment Editor tools. This module of the 3D Slicer software finds segments, or structures of interest, in 2D, 3D, and 4D images. It is possible to display in two or three dimensions, create segmentation by interpolating or extrapolating segmentation on a small number of slices, make fine-grained visualization decisions, and edit on slices in any orientation [37]. The anatomical features of the cervical spine were studied. The procedure for transforming the segmented DICOM data into a standard triangulation language (STL) file is shown in Figure 5. Open loops and minuscule holes in the STL file were detected using the software Autodesk Meshmixer, as shown in Figure 4(b).

Cervical spine (a) DICOM format of CT scan images, and (b) cervical region in thresholding range.

Editing of the cervical region of the model: (a) unwanted objects around the neck region, and (b) open loops identified in.stl file of the neck model.

Exported STL file of the neck model after error rectification.

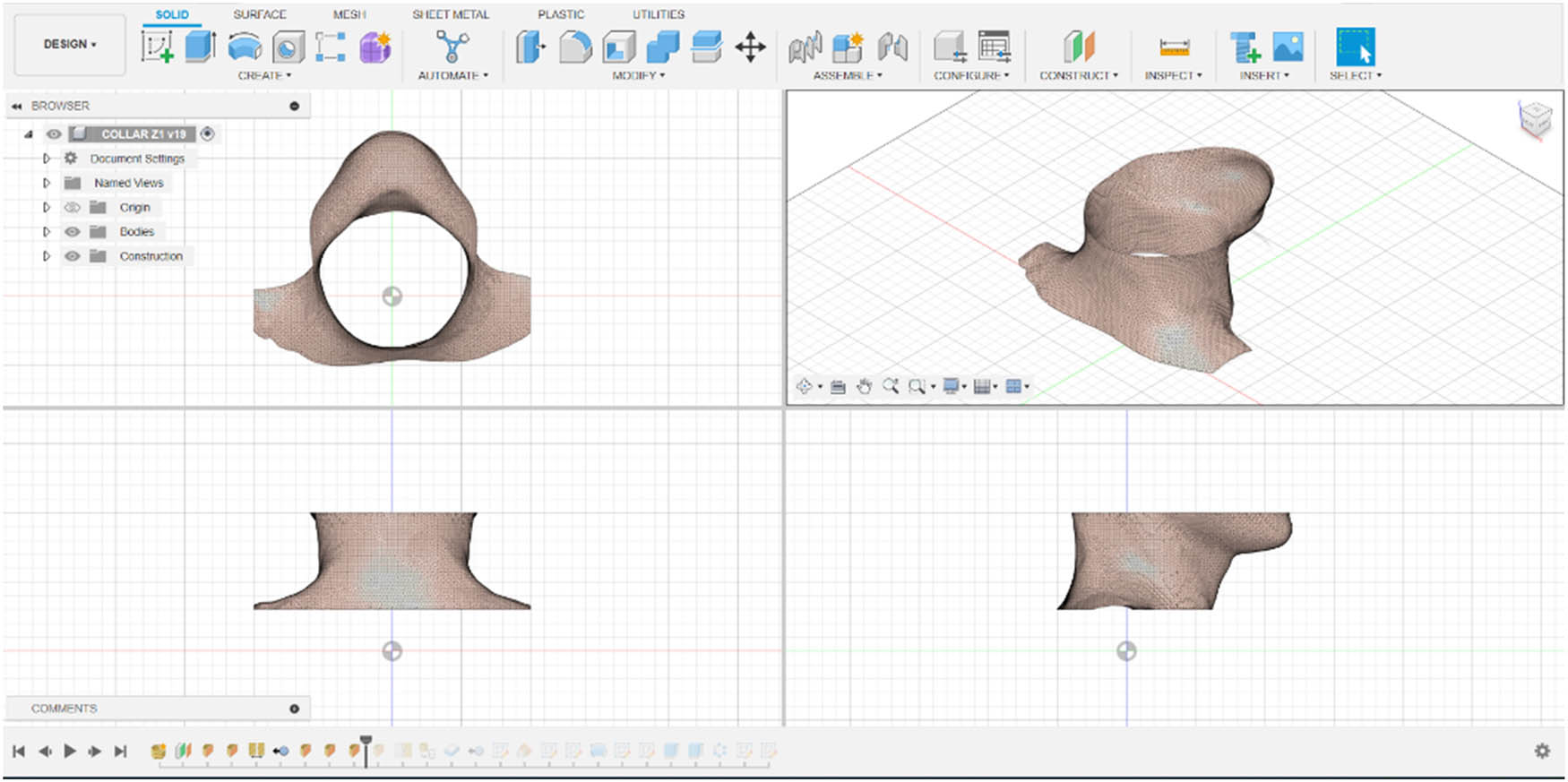

2.3.2 3D modeling of cervical collar

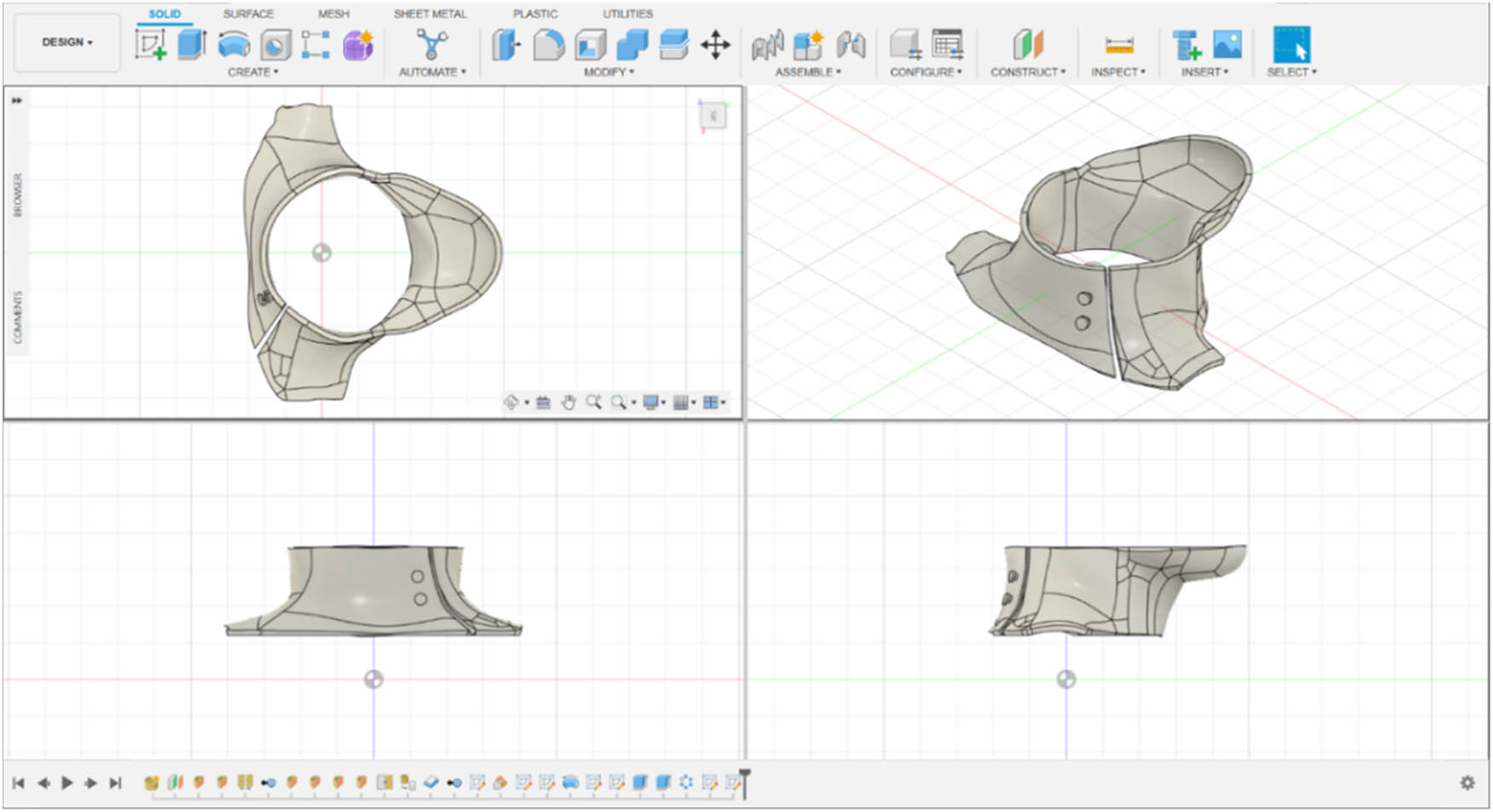

Autodesk Fusion 360 software was utilized for the construction of the model. The patient’s digital model served as the foundation for the creation of a neck orthosis. Furthermore, the imported neck model and the upper trapezius muscle, which is located between the neck and shoulders, are depicted in Figure 6.

Imported neck model in Autodesk Fusion 360.

The model structure was similar to that of the market’s standard stiff orthoses, which support the neck from the chest to the neck. The trapezius muscle provides additional support on both the left and right sides of the design. The right and left regions that rest on the trapezius muscles were constructed correctly [38]. Compared to a traditional neck orthosis, the chin support piece has a larger contact area with the chin and serves as a platform for the chin to rest on. As a result, less pressure was placed on the chin. Its goal is to improve the stability and comfort of orthoses. Our design’s primary characteristic was the model’s adaptability. The bending geometry reduces discomfort from chills and helps cure minor issues while partially immobilizing the neck [24]. The model’s thickness was optimized to balance lightweight characteristics with structural strength, resulting in a value of approximately 3.5 mm. This is thinner than standard commercial orthoses but adequate for maintaining performance due to the design enhancements and material selection. The CAD model, as shown in Figure 7, was designed with the goal of creating a device that functions similar to the commercially available cervical semi-rigid collars. Such a cervical collar is typically thought of as an orthosis device that fits the neck, from the jaw to the chest. To promote recovery, it is employed to restrict mobility and aid the neck during surgical operations, fracture therapies, and cervical injury treatments. Conversely, soft cervical orthoses provide support for the neck, help ease minor pressures on the neck, and lessen pain after accidents (such as whiplash). They also have a softer geometric pattern. The thickness value selected was the standard average thickness used in prefabricated orthoses.

CAD model of cervical collar.

2.3.3 Analysis of cervical collar

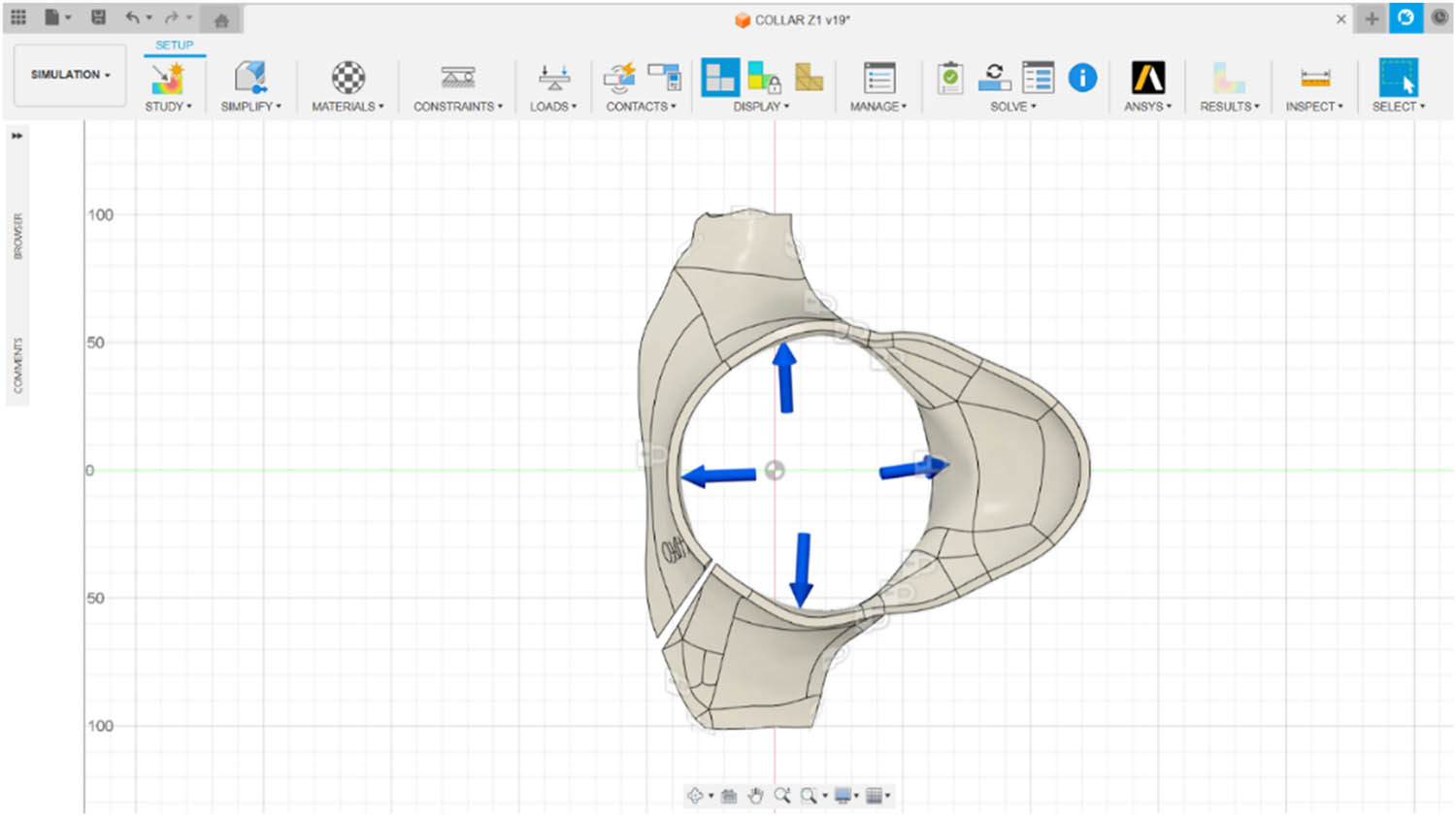

Autodesk Fusion 360 software was utilized to analyze the model, as displayed in Figure 8. Static linear assessment was carried out to ascertain the model’s strength. The neck collar was made of the PLA material. Table 1 lists the material’s mechanical characteristics.

Loads and boundary conditions on cervical collar.

PLA material properties

| Density | 1.3 × 10−6 kg/mm3 |

| Young’s modulus | 3,500 MPa |

| Poisson’s ratio | 0.35 |

| Yield strength | 49.5 MPa |

| Ultimate tensile strength | 50 MPa |

| Thermal conductivity | 1.3 × 10−4 W/mm °C |

| Thermal coefficient of expansion | 8.57 × 10−5/°C |

| Specific heat | 1,800 J/kg °C |

A cervical orthosis typically experiences a combination of stresses due to the complex relationship between the cervical spine and neck muscles. Several investigations were carried out utilizing a range of experimental methodologies to examine commercially available cervical collars and evaluate their capacity to restrict cervical spine motion during flexion, extension, and lateral bending [6]. Vasavada et al. [39] conducted an investigation involving male and female participants from different age groups to analyze and characterize the moment of the neck. It was possible to calculate the flexion, extension, and lateral bending moments due to the spontaneous development of muscles. The experiment yielded the applied forces and their directions for the average male value.

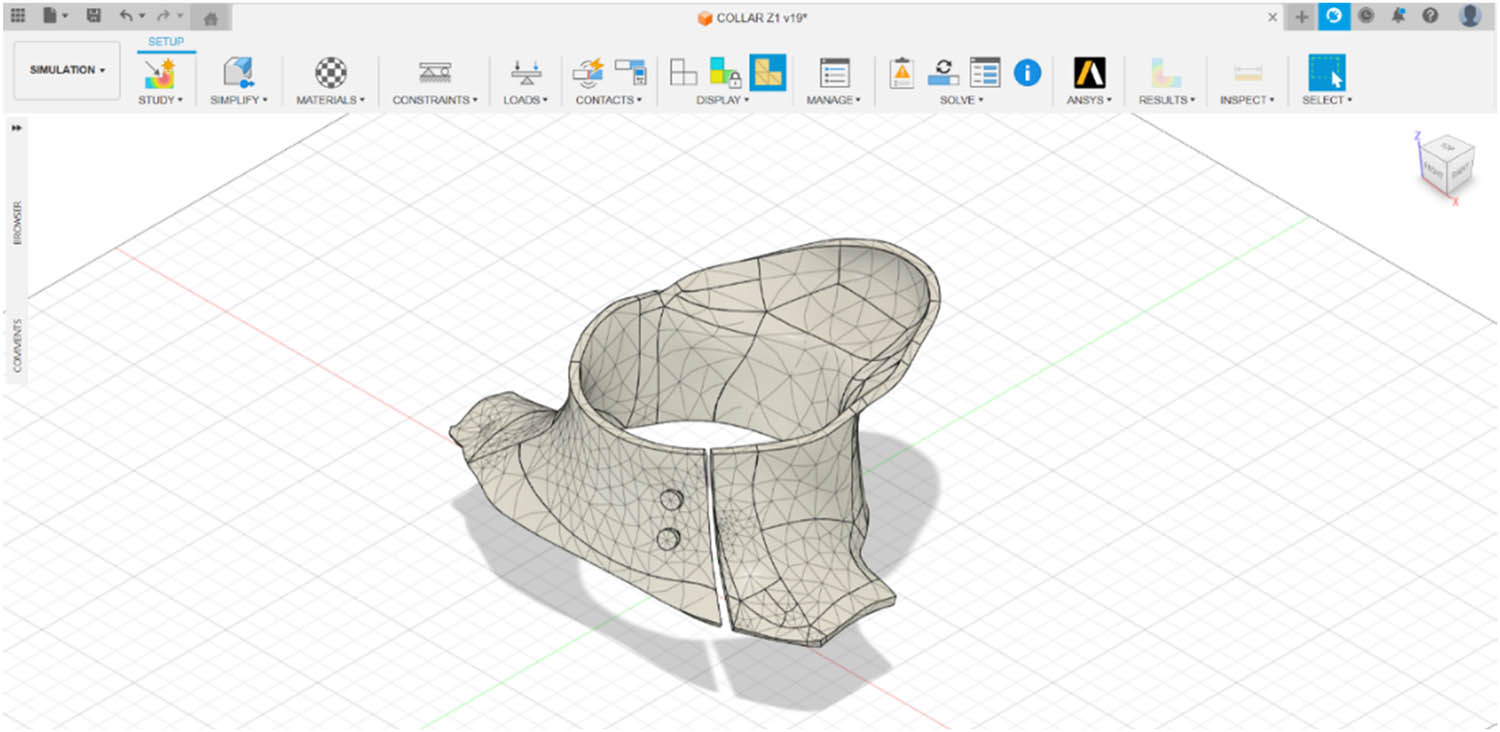

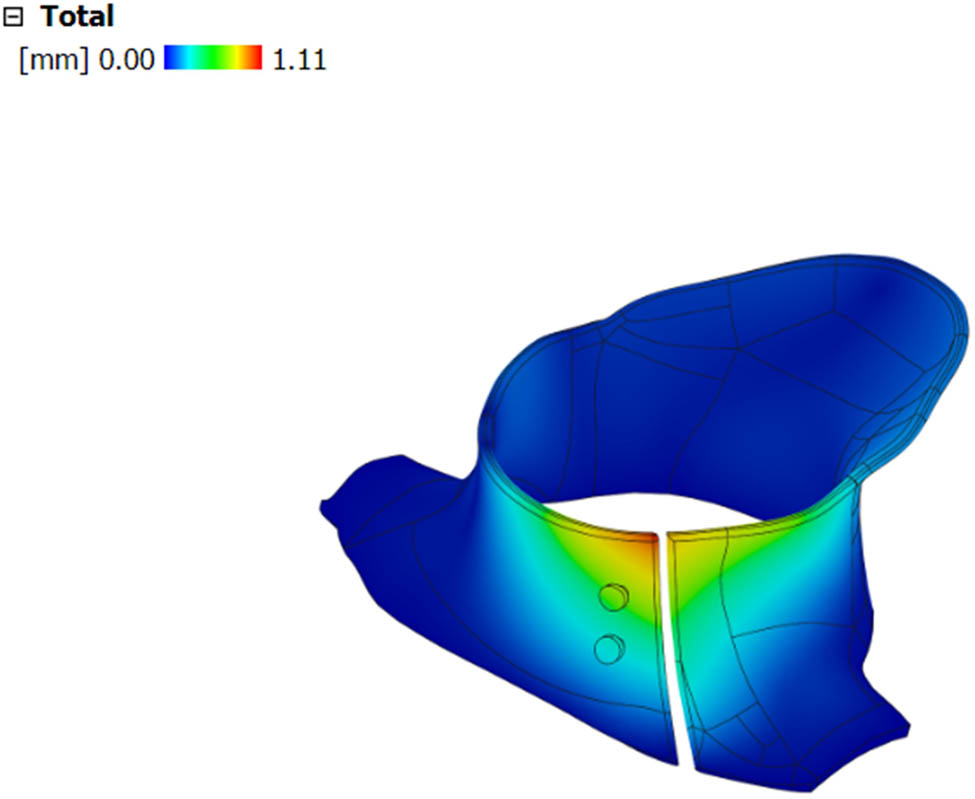

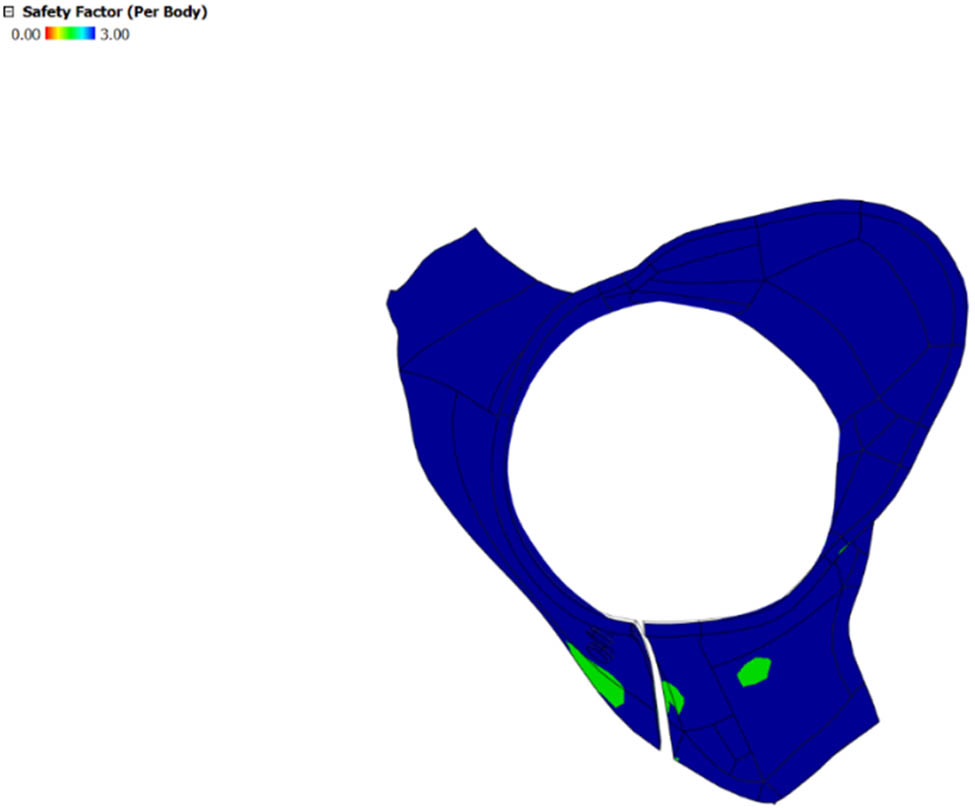

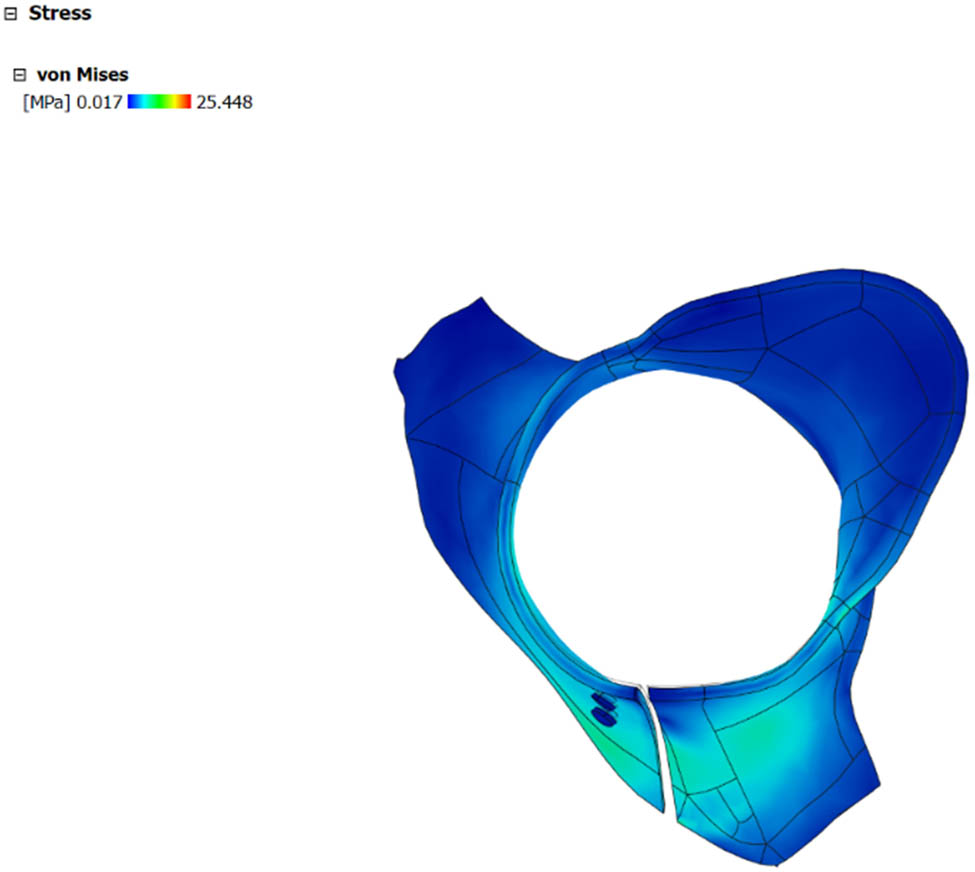

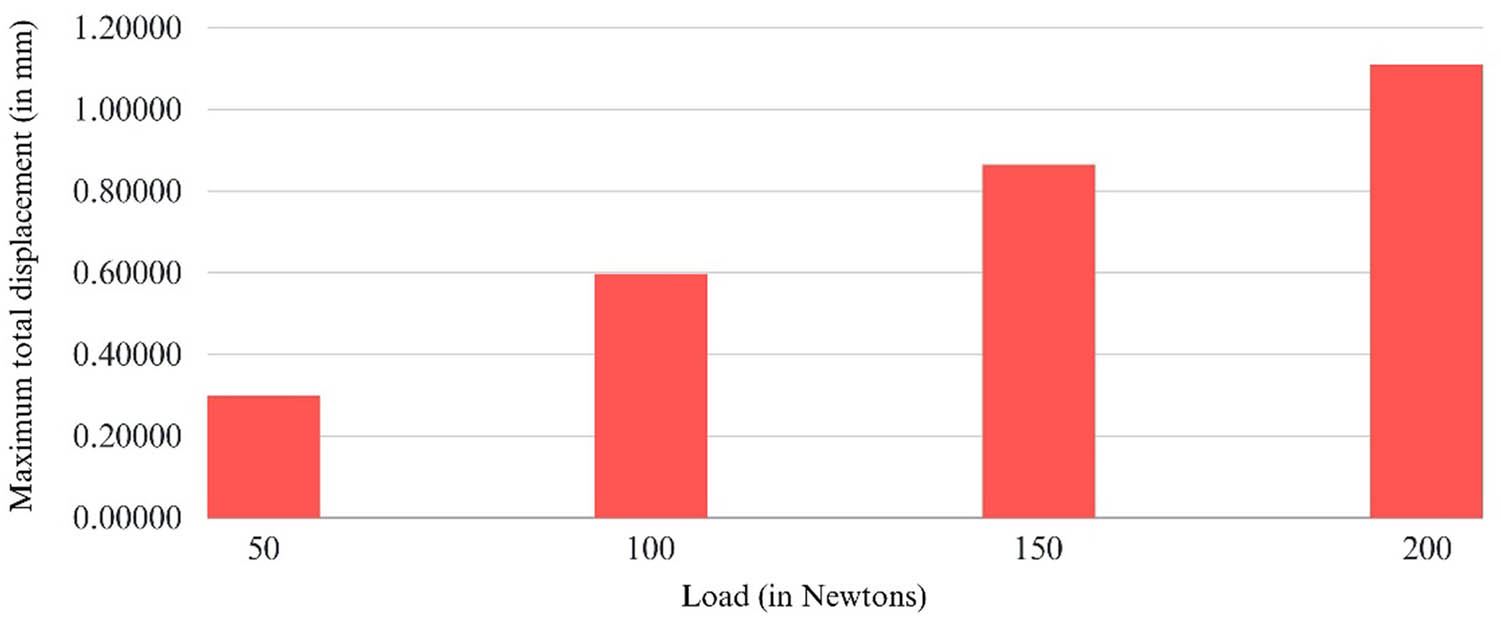

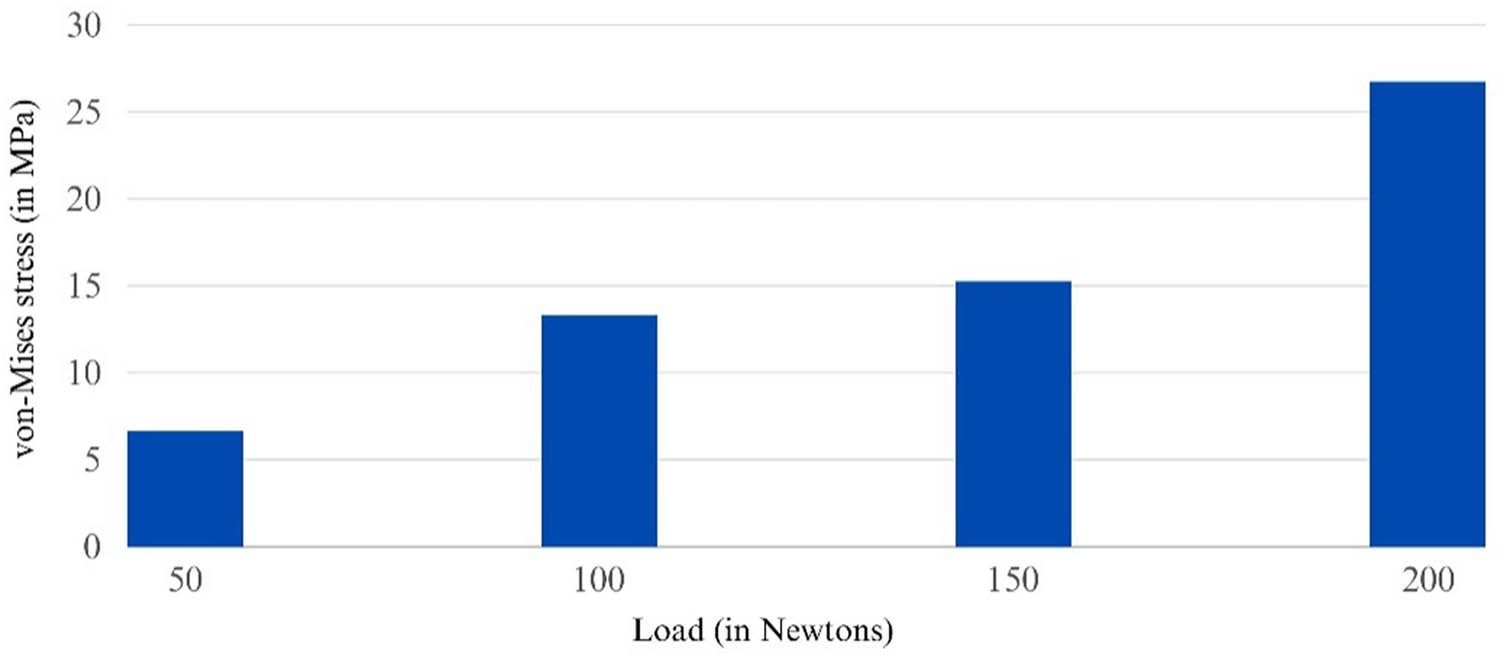

The model was subjected to external loads ranging from 50 to 200 N and boundary conditions, as shown in Figure 8. The applied loads reflect biomechanical forces acting on the cervical spine during typical activities such as sitting, standing, and mild neck movements. Biomechanical studies indicate that the human head exerts 45–55 N of force on the cervical spine in a static posture, increasing to 150–200 N during movement. To ensure safety and performance, the cervical collar design was tested up to 200 N. Simulations across this range validated the structural integrity and optimized the lattice for both support and comfort. The maximum load force of 200 N was chosen to enable the model to withstand more force than the 100 N created by the weight of the head. To enhance the understanding of the appearance, Figure 8 shows the positions of the applied forces on the model’s inner surface. To simulate realistic use, the posterior side of the cervical collar model was fixed to simulate its contact with the upper thoracic region. A load of 200 N was applied perpendicular to the inner surface in various directions to replicate lateral bending, flexion, and extension movements. Bonded contacts were defined between all connected components. Load forces were applied uniformly and perpendicularly at multiple locations to represent the mechanical impact of head movement [4]. As shown in Figure 9, 6,852 nodes and 3,321 elements make up the 3D mesh. As shown in Figure 10, the maximum displacement due to applied force was recorded as 1.110 mm, which was comparable to 1.4685 mm by Sabyrov et al. [38]. The largest displacement was noted on the backside of the model with a factor of safety of 3, as depicted in Figure 11. Von Mises stress of 25.448 MPa was observed in the model, as depicted in Figure 12.

3D mesh file of the cervical collar.

Displacement of the cervical collar.

Factor of safety of the cervical collar.

Stress (von Mises) distribution in the cervical collar.

2.4 3D printing of the cervical collar

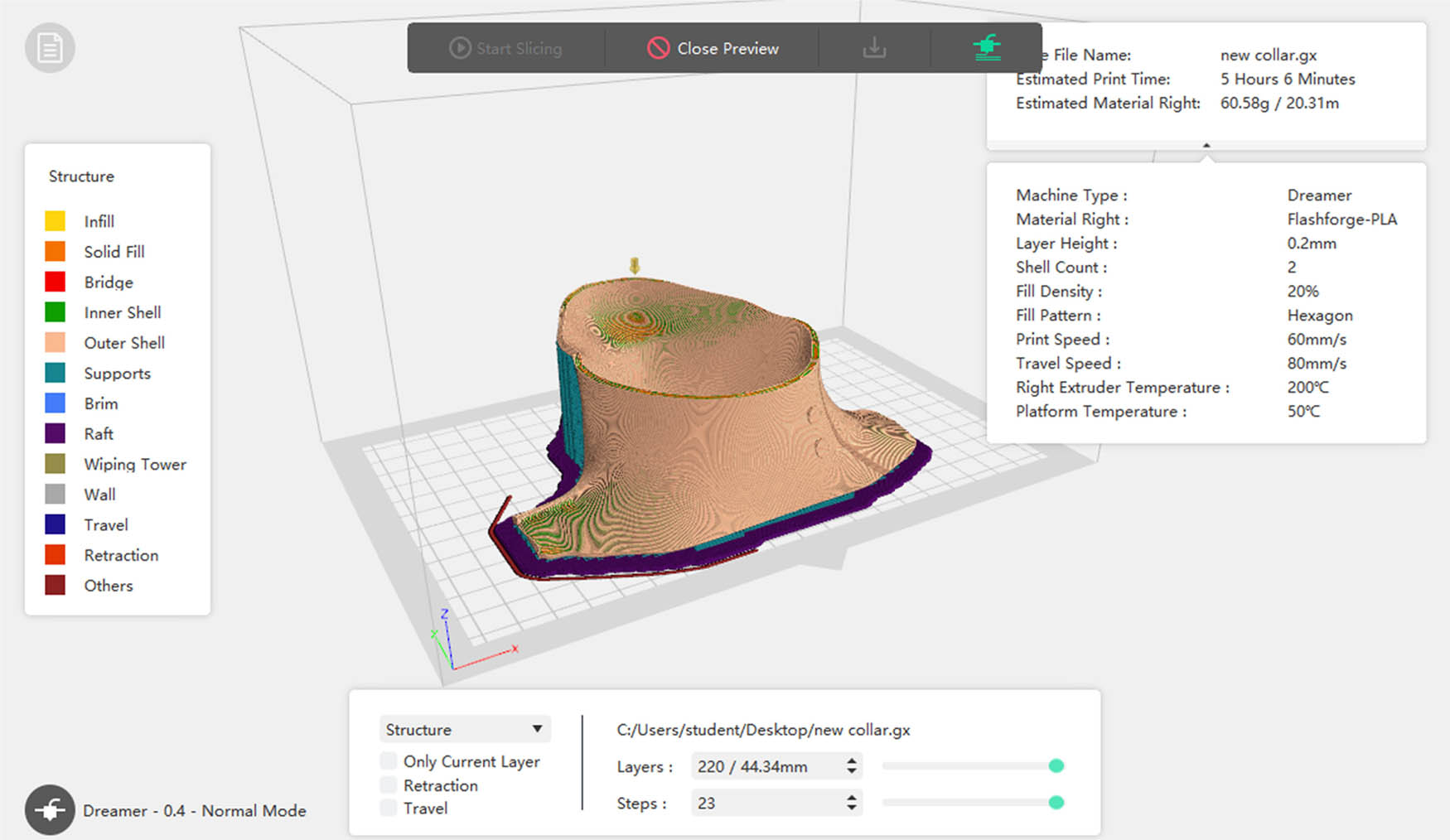

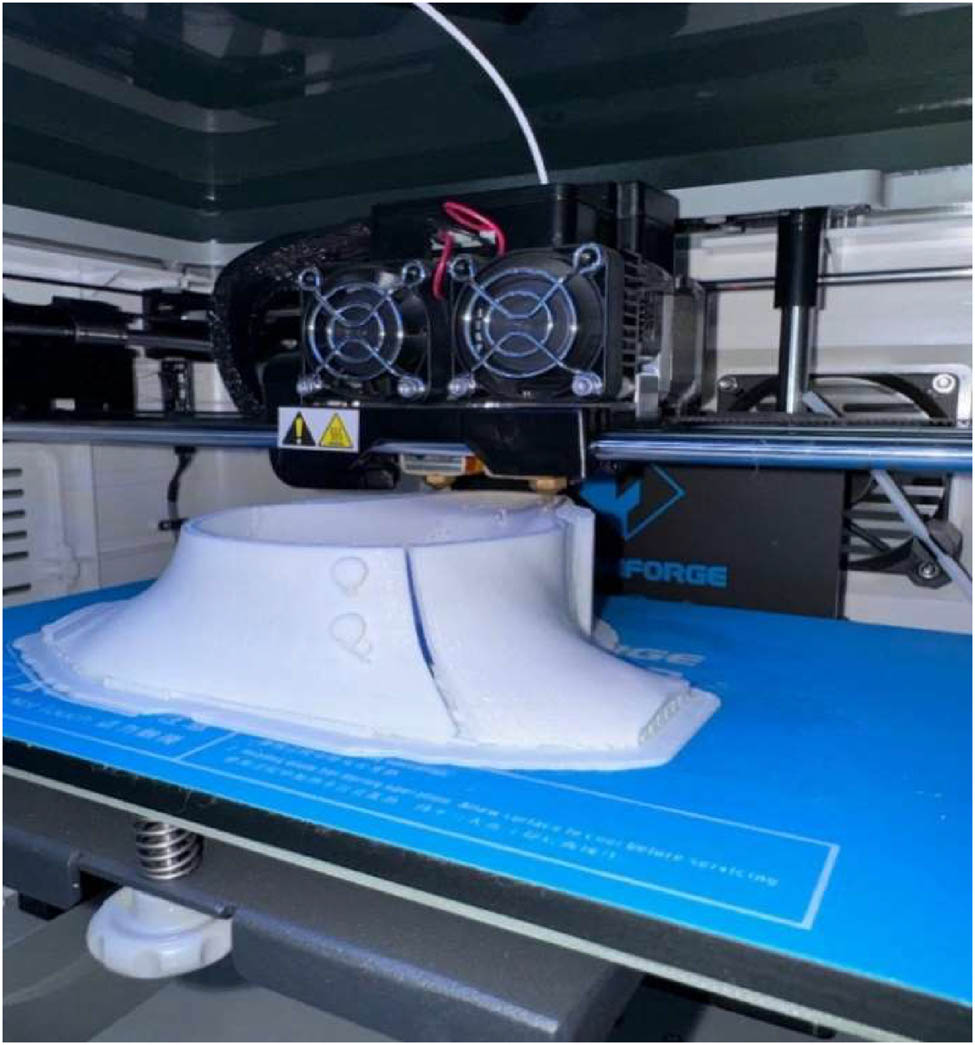

3D printing of the cervical collar was effectively conducted on the cutting-edge FDM Flashforge Guider II printer. Figure 13, which shows the parameters of the prototype after slicing was done, offers a thorough grasp of the FDM process and the Flashforge Guider II printer. The Flashforge Flashprint software is a vital tool for efficiently controlling and regulating the parameters of the 3D printing process [40]. This tool makes it possible to precisely specify the print settings and slice the STL file, which is necessary in order to import the three-dimensional model into the printing environment. The crucial 3D printing variables and their respective values are presented in Table 2. The printing of the cervical collar prototype is depicted in Figure 14.

Prototype after slicing in Flashprint software.

Process parameters used for printing the prototype

| Type of material | PLA |

|---|---|

| Layer height | 0.2 mm |

| Shell count | 2 |

| Fill density | 20% |

| Fill pattern | Hexagonal |

| Estimated time | 5 h 6 min |

3D printing of a prototype in Flashforge Guider II printer.

3 Results and discussion

Figure 3(a) and (b) shows the DICOM data file in 3D Slicer software along with the threshold values that were assigned. To improve the visualization of the neck region, the thresholds have been set at 5.21 and 2796.62 for the lowest and top values, respectively. Figures 4a and 5 show the presence of additional geometries and their removal, respectively. Sharp edges and apparent geometries were removed using scissors, and invisible geometries were removed with smoothing. Using Autodesk Meshmixer software, the open loops in the neck area were addressed during the DICOM to STL file conversion [41]. The recognition and correction of these open loops (small holes) are shown in Figures 4(b) and 5, respectively.

3.1 Design of the model

This cervical orthosis was designed with the cervical lordotic spine in mind, as it exclusively fits the cervical region of the spine. When neck discomfort, misalignment, or fracture in any cervical vertebrae occurs, the need for custom fitting becomes crucial. Because custom fitting stabilizes the wounded area, it becomes essential and speeds up the healing process overall. The technology is more practical and cost-effective since 3D printing is an inexpensive procedure with no chance of expensive mistakes. Easy alterations and modifications to CAD designs increase the structure’s overall compliance. The cervical orthosis has been subjected to FEA, and the outcomes have shown that the model can endure significant force, as demonstrated by the reduced levels of stress and displacement. This study explored the utility of 3D printing technology in the development of customized cervical collar orthotic devices for individual patients. 3D Slicer software was employed to process the scanned CT data of the patient, which was acquired in DICOM format. It is necessary to modify the thresholding value in the software to yield the exact region of interest while segmenting. The scissoring tool was used to eliminate additional geometries. The exterior part of the neck was smoothed with a smoothing tool. As depicted in Figure 5, smoothing helps to remove the invisible geometry, while scissors help to remove much of the apparent geometry. Autodesk Meshmixer was used to identify and rectify open loops that arise when converting a DICOM file to an STL file, as exhibited in Figure 5.

3.2 Analysis on the model

A linear static analysis was done on the model in order to evaluate it and see its equivalent stress, displacement, and safety factors. The posterior area, indicated by a red patch in Figure 10, exhibited the most displacement when the model was subjected to an external force ranging from 50 N to a maximum of 200 N. The displacement was measured at 1.110 mm. The bottom portion of the model’s posterior and anterior sections had the least displacement, while the top posterior chunk of the model displayed the most displacement. It was discovered that the maximum stress (von Mises) at 200 N was 25.448 MPa. In the model, the distribution of stress was seen and noted. Upon careful inspection, no localized or concentrated strains were found; instead, the stress was found to be consistent across the model. The findings of the element stress analysis are displayed in Figure 12. Overall, the stress pattern in the model was dispersed equally. Finally, the analytical results fully fulfilled the standard and material strength criteria, as evidenced by the factor of safety being determined to be 3, as shown in Figure 11. The results attained at various loading conditions can be contrasted in terms of maximum total displacement, as exhibited in Figure 15.

Maximum total displacements in the model at different loading conditions.

As exhibited in Figure 15, it can be deduced that, for each of the loading conditions, the maximum total displacement increases. The maximum stress (von Mises) was considered a significant parameter in this investigation for assessing the model under varying loading conditions. Figure 16 displays the von Mises stress for each of the loading configurations. It can be noted that higher von Mises stress values were obtained with an increase in the external force applied to the model.

von Mises stress in the model at different loading conditions.

3.3 3D printing of the cervical collar prototype

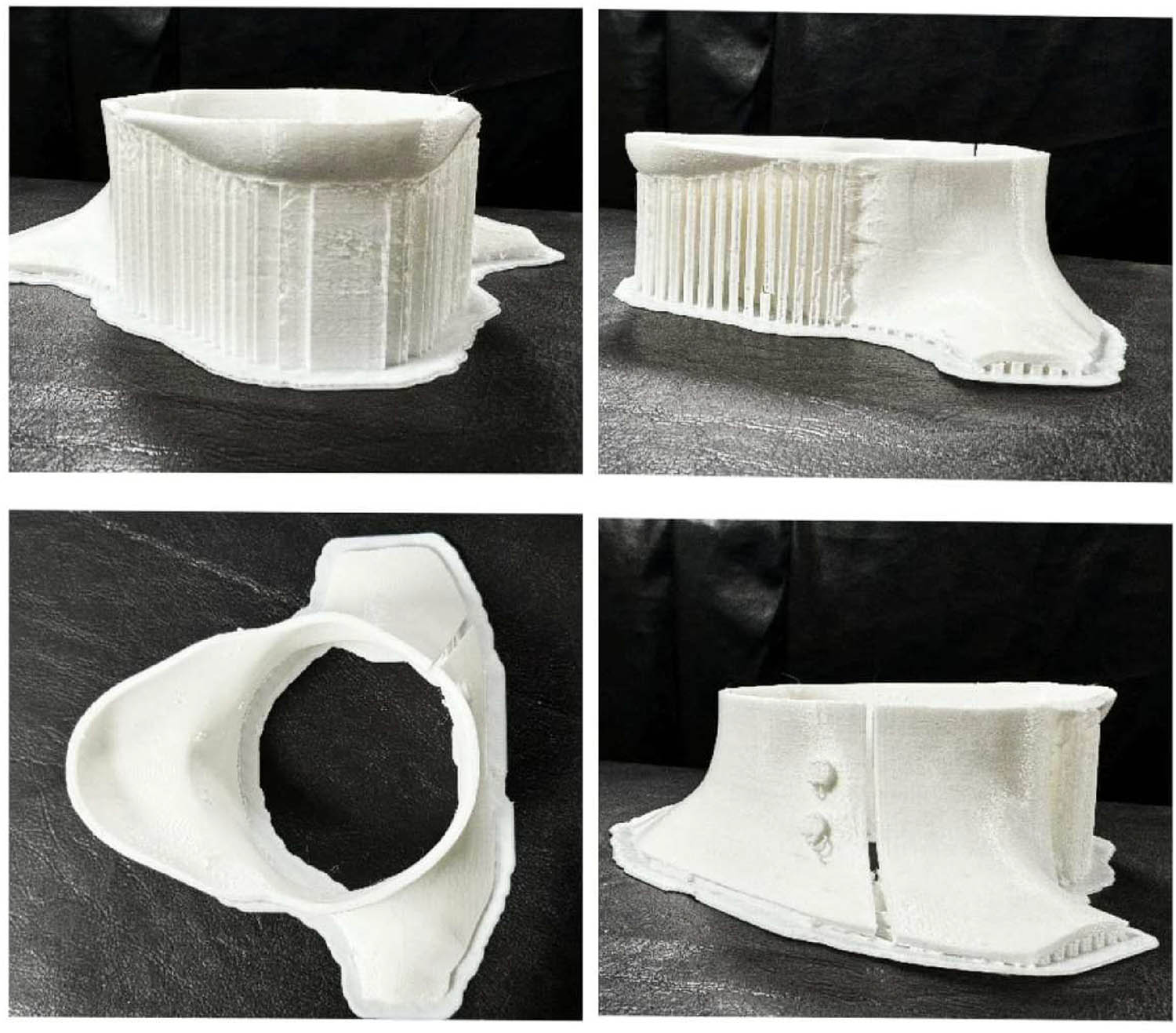

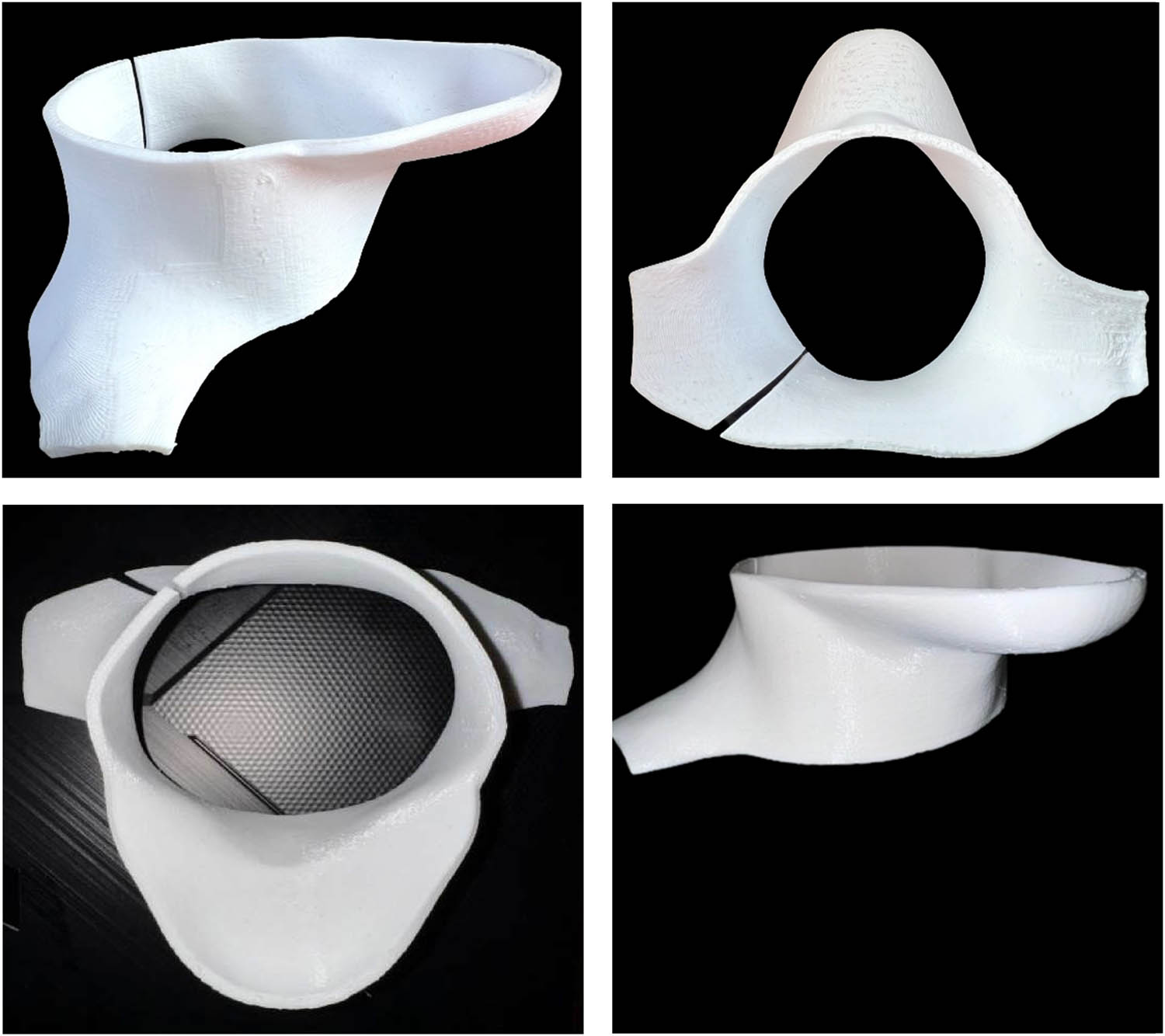

The cervical collar’s STL file was imported using Flashprint software. To minimize support, increase accuracy, and provide a smooth surface finish, several orientations were evaluated. The cervical orthosis prototype was printed using two shells, 20% hexagon-patterned infill, and a layer height of 0.20 mm. The prototype was printed on an FDM-based 3D printer, using PLA, a biodegradable material. Combined with the supports, it weighed 60.58 g and took 6 h and 5 min to finish the printing process. The approach has effectively addressed several challenges, including the need to model the neck, capture extra geometries during the scan, and correct STL mistakes.

3.3.1 Post-processing

The 3D-printed cervical collar made of PLA material requires close attention to detail in the post-processing. First, the primary structure was preserved by carefully removing the supports, as shown in Figure 17. The next step involved smoothing the surface with sandpaper or a sanding sponge, progressively going from coarse to finer grits to get rid of layer lines and uneven surfaces. Then, to fix any residual flaws and promote a consistent surface texture, a filler/primer specifically made for PLA material was carefully applied. To obtain the best smoothness, each layer was softly sanded in between applications. All these procedures work together to improve the cervical collar’s texture and look, making it ready for more personalization and practical upgrades. 3D-printed cervical collar prototype post-eviction of support elements is shown in Figure 18.

Prototype before post-processing.

3D-printed cervical collar prototype after post-processing.

3.3.2 Benefits of a 3D-printed cervical collar

The 3D-printed cervical collar is designed for leveraging patient comfort by utilizing smart design, appropriate material, and structural optimization. The comfort features include the following.

Breathable and soft support: A custom-designed flexible lattice structure, created in nTopology, cushions the neck, minimizes pressure, and enhances airflow. The density varies by region for targeted support and comfort.

Lightweight design: Efficient design and 3D printing resulted in a lighter collar, as compared to traditional ones, thereby preventing strain on the neck.

Personalized fit: Using 3D scanning, the 3D-printed collar is custom-made to patient anatomy, ensuring both fit and compliance.

Skin-friendly material: Use of biocompatible and skin-friendly materials such as medical-grade PLA minimizes irritation risk and protects sensitive skin.

Shock absorption: The lattice structure spreads pressure evenly and acts like tiny springs, absorbing small movements for extra comfort.

FEA Validation: Simulation confirmed the effective load distribution and structural performance of the collar, that is, it can handle normal neck pressures (50–200 N) without breaking or causing discomfort.

A discussion on the difficulties encountered while executing this study is as follows:

Complex structures or designs of the human neck make direct modeling using CAD tools impossible. Reverse engineering allows for the modeling of such profiles using CT images. A sequence of processing processes is applied to the retrieved CT scan data in order to obtain the final Neck model STL file. In CAD software, the Neck model may be added to and modified using the STL file. Because these scans were so sensitive, extra geometries and noise captured must be eliminated afterwards. Additional geometries and noise, which were not required, were eliminated utilizing a variety of 3D Slicer software capabilities, as was previously mentioned, as shown in Figure 4a.

Errors were also produced during the conversion of a CAD model to an STL file. Figure 4b shows how Autodesk Meshmixer was used to fix open loops and overlapping triangle STL problems.

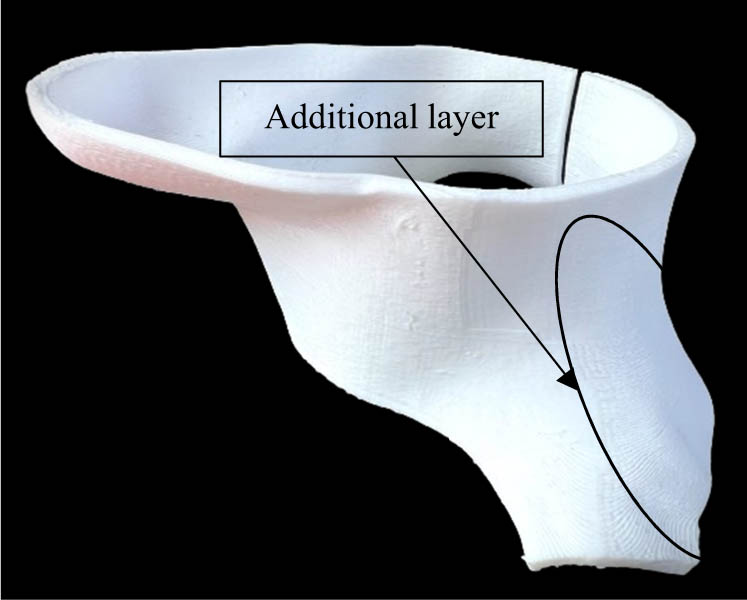

There were further difficulties with the 3D-printed collar prototype. As shown in Figure 19, the prototype in this study still shows extra layer or line markings even after model adjustments and the determination of the ideal printing parameters. These were eliminated by polishing and sanding the surfaces.

Additional layers in the 3D-printed cervical collar.

4 Conclusions

A 3D-printed cervical orthosis prototype was designed and developed after thoroughly evaluating it for structural analysis. To ensure the model’s assessment, the created model was structurally evaluated under a 200 N force, yielding varying stress, displacement, and factor of safety values. FE simulations were used to confirm that the model developed had an appropriate stiffness. Additionally, it was discovered that employing a biocompatible, biodegradable, and sustainable PLA material for the cervical orthosis’s fabrication improved the model’s overall strength due to its enhanced mechanical properties. Using 3D printing technology to conduct personalized orthotic design has been demonstrated to be a feasible and successful approach that may benefit patients. To demonstrate the construction of cervical orthoses, further research will focus on improving weight reduction, ventilation, and flexibility through topology optimization on the current model and additive manufacturing.

Acknowledgments

This study was not supported by any grants from funding bodies in the public, private, or not-for-profit sectors. The authors acknowledge the necessary resources and support provided by the Center of Excellence for Additive Manufacturing at VNRVJIET.

-

Funding information: Authors state no funding involved.

-

Author contributions: Y.S.N.: problem definition and conceptual idea. K.J.P.: methodology, original draft writing – review, and editing. M.T.S.: data collection and interpretation of results. B.S.B.: literature review, final review, and editing. S.R.D.: investigation, validation of results, and manuscript review. All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript, given consent to its submission to the journal, reviewed all the results, and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

[1] Babu RD, Veezhinathan M, Adithya SS, Jagadeesan N. Design and development of a 3D printable neck brace- a finite element approach. J Clin Diagn Res. 2022;16:10–5. 10.7860/JCDR/2022/57066.16975.Search in Google Scholar

[2] Liu B, Zhu Y, Liu S, Chen W, Zhang F, Zhang Y. National incidence of traumatic spinal fractures in China: Data from China National Fracture Study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97(35):e12190. 10.1097/MD.0000000000012190.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[3] Niemi-Nikkola V, Saijets N, Ylipoussu H, Kinnunen P, Pesälä J, Mäkelä P, et al. Traumatic spinal injuries in northern Finland. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2018;43(1):E45–51. 10.1097/BRS.0000000000002214.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[4] Xu Y, Li X, Chang Y, Wang Y, Che L, Shi G, et al. Design of personalized cervical fixation orthosis based on 3D printing technology. Appl Bionics Biomech. 2022;2022:8243128. 10.1155/2022/8243128.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[5] Barati K, Arazpour M, Vameghi R, Abdoli A, Farmani F. The effect of soft and rigid cervical collars on head and neck immobilization in healthy subjects. Asian Spine J. 2017;11(3):390–5. 10.4184/asj.2017.11.3.390.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[6] Ambu R, Motta A, Calì M. Design of a customized neck orthosis for FDM manufacturing with a new sustainable bio-composite. In Lecture notes in mechanical engineering. Modena, Italy: Springer; 2020. p. 707–18. 10.1007/978-3-030-31154-4_60.Search in Google Scholar

[7] Hacking C, Luijkx T. Cervical spine. Radiopaedia.org.; 2014. 10.53347/RID-30849.Search in Google Scholar

[8] Berlin C, Adams C. Production ergonomics: Designing work systems to support optimal human performance. London, UK: Ubiquity Press; 2017. 10.5334/BBE.Search in Google Scholar

[9] Vialle LR, Oner FC, Vaccaro AR, editors. Anatomy of the cervical spine. In Cervical spine trauma. Stuttgart, Germany: Thieme; 2015. 10.1055/B-0035-122262.Search in Google Scholar

[10] Palmieri M, Donno L, Cimolin V, Galli M. Cervical range of motion assessment through inertial technology: A validity and reliability study. Sensors (Basel). 2023;23(13):6013. 10.3390/s23136013.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[11] Bogduk N. Functional anatomy of the spine. Handb Clin Neurol. 2016;136:675–88. 10.1016/B978-0-444-53486-6.00032-6.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[12] Demetriades AK, Tessitore E. External cervical orthosis (hard collar) after ACDF: Have we moved forward? Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2020;162(2):327–8. 10.1007/s00701-019-04167-x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[13] Zhang S, Wortley M, Clowers K, Krusenklaus JH. Evaluation of efficacy and 3D kinematic characteristics of cervical orthoses. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon). 2005;20(3):264–9. 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2004.09.015.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[14] Jin H, Xu R, Wang S, Wang J. Use of 3D-printed heel support insoles based on arch lift improves foot pressure distribution in healthy people. Med Sci Monit. 2019;25:7175–81. 10.12659/MSM.918763.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[15] Cha YH, Lee KH, Ryu HJ, Joo IW, Seo A, Kim DH, et al. Ankle-foot orthosis made by 3D printing technique and automated design software. Appl Bionics Biomech. 2017;2017:9610468. 10.1155/2017/9610468.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[16] Shahar FSS, Sultan MTH, Shah AUM, Safri SNA. A comparative analysis between conventional manufacturing and additive manufacturing of ankle-foot orthosis. Appl Sci Eng Prog. 2020;13(2):96–103. 10.1080/17483107.2019.1629114.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[17] Jin YA, Plott J, Chen R, Wensman J, Shih A. Additive manufacturing of custom orthoses and prostheses - A review. Procedia CIRP. 2015;36:199–204. 10.1016/j.procir.2015.02.125.Search in Google Scholar

[18] Kumar JA, Prakash KJ, Narayan YS, Satyanarayana B. Finite element analysis of a patient specific maxillofacial implant. Int J Eng Trends Technol. 2022;70:354–61. 10.14445/22315381/IJETT-V70I9P235.Search in Google Scholar

[19] Hale L, Linley E, Kalaskar DM. A digital workflow for design and fabrication of bespoke orthoses using 3D scanning and 3D printing, A patient-based case study. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):7028. 10.1038/s41598-020-63937-1.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[20] Hosseini P, Karimi M, Abnavi F, Golabbakhsh M. Evaluation of the efficiency of Minerva collar on cervical spine motions. J Rehabil Sci Res. 2018;4(2):47–52. 10.30476/JRSR.2017.41118.Search in Google Scholar

[21] Worsley PR, Stanger ND, Horrell AK, Bader DL. Investigating the effects of cervical collar design and fit on the biomechanical and biomarker reaction at the skin. Med Devices (Auckl). 2018;11:87–97. 10.2147/MDER.S149419.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[22] Cerillo JL, Becsey AN, Sanghadia CP, Root KT, Lucke-Wold B. Spine bracing: When to utilize-a narrative review. Biomechanics (Basel). 2023;3(1):136–54. 10.3390/biomechanics3010013.Search in Google Scholar

[23] Visscher DO, Slaa S, Jaspers ME, Hulsbeek M, Borst J, Wolff J, et al. 3D printing of patient-specific neck splints for the treatment of post-burn neck contractures. Burn Trauma. 2018;6:26. 10.1186/s41038-018-0116-1.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[24] Schroderus J, Lasrado LA, Menon K, Kärkkäinen H. Towards a Pay-Per-X maturity model for equipment manufacturing companies. Procedia Comput Sci. 2021;192:226–34. 10.1016/j.procs.2021.12.009.Search in Google Scholar

[25] Cao M, Cui T, Yue Y, Li C, Guo X, Jia X, et al. Preparation and characterization for the thermal stability and mechanical property of PLA and PLA/CF samples built by FFF approach. Materials (Basel). 2023;16(14):5023. 10.3390/ma16145023.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[26] Popescu D, Baciu F, Vlăsceanu D, Marinescu R, Lăptoiu D. Investigations on the fatigue behavior of 3D-printed and thermoformed polylactic acid wrist–hand orthoses. Polymers (Basel). 2023;15(12):2737. 10.3390/polym15122737.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[27] Barbosa WS, Gioia MM, Temporão GP, Meggiolaro MA, Gouvea FC. Impact of multi-lattice inner structures on FDM PLA 3D printed orthosis using Industry 4.0 concepts. Int J Interact Des Manuf. 2023;17(1):371–83. 10.1007/s12008-022-00962-6.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[28] Dasharath R, Narayana YS, Prakash KJ, Pothula N. Trends in characterization and analysis of TKA implants for 3D printing. E3S Web Conf. 2023;430:01275. 10.1051/e3sconf/202343001275.Search in Google Scholar

[29] Mobarak MH, Islam MA, Hossain N, Mahmud MZ, Rayhan MT, Nishi NJ, et al. Recent advances of additive manufacturing in implant fabrication – A review. Appl Surf Sci Adv. 2023;18:100462. 10.1016/j.apsadv.2023.100462.Search in Google Scholar

[30] Negru N, Leba M, Rosca S, Marica L, Ionica A. A new approach on 3D scanning-printing technologies with medical applications. IOP Conf Ser Mater Sci Eng. 2019;572:012049. 10.1088/1757-899X/572/1/012049.Search in Google Scholar

[31] Liao J, Brosse N, Hoppe S, Du G, Zhou X, Pizzi A. One-step compatibilization of poly(lactic acid) and tannin via reactive extrusion. Mater Des. 2020;191:108603. 10.1016/j.matdes.2020.108603.Search in Google Scholar

[32] Mwema FM, Akinlabi ET, Fatoba OS. Visual assessment of 3D printed elements: A practical quality assessment for home-made FDM products. Mater Today Proc. 2020;26:1520–5. 10.1016/j.matpr.2020.02.313.Search in Google Scholar

[33] Folino A, Karageorgiou A, Calabrò PS, Komilis D. Biodegradation of wasted bioplastics in natural and industrial environments: A review. Sustainability. 2020;12(15):6030. 10.3390/su12156030.Search in Google Scholar

[34] Fekete I, Ronkay F, Lendvai L. Highly toughened blends of poly(lactic acid) (PLA) and natural rubber (NR) for FDM-based 3D printing applications: The effect of composition and infill pattern. Polym Test. 2021;99:107205. 10.1016/j.polymertesting.2021.107205.Search in Google Scholar

[35] Narayan YS, Prakash KJ, Rajashekhar S, Narendra P. 3D printed human humerus bone with proximal implant prototype for arthroplasty. Int J Health Sci. 2022;6(S4):10953–67. 10.53730/ijhs.v6nS4.11291.Search in Google Scholar

[36] Ramavath D, Yeole SN, Kode JP, Pothula N, Devana SR. Development of patient-specific 3D printed implants for total knee arthroplasty. Explor Med. 2023;4:1033–47. 10.37349/emed.2023.00193.Search in Google Scholar

[37] Zhang X, Zhang K, Pan Q, Chang J. Three-dimensional reconstruction of medical images based on 3D slicer. J Complex Health Sci. 2019;2(1):1–12. 10.21595/chs.2019.20724.Search in Google Scholar

[38] Sabyrov N, Sotsial Z, Abilgaziyev A, Adair D, Ali MH. Design of a flexible neck orthosis on fused deposition modeling printer for rehabilitation on regular usage. Procedia Comput Sci. 2021;179:63–71. 10.1016/j.procs.2020.12.009.Search in Google Scholar

[39] Vasavada AN, Li S, Delp SL. Three-dimensional isometric strength of neck muscles in humans. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2001;26(17):1904–9. 10.1097/00007632-200109010-00018.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[40] Przekop RE, Gabriel E, Pakuła D, Sztorch B. Liquid for fused deposition modeling technique (l-fdm)-a revolution in application chemicals to 3D printing technology: color and elements. Appl Sci (Switz). 2023;13(13):7393. 10.3390/app13137393.Search in Google Scholar

[41] Filho CWLS, Pontes MDS, Ramos CH, Da Cunha LAM. Methodology for preoperative planning of bone deformities using three-dimensional modeling software. Rev Bras Ortop (Sao Paulo). 2023;59(1):e130–5. 10.1055/s-0044-1779700.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Probing microstructural evolution and surface hardening of AISI D3 steel after multistage heat treatment: An experimental and numerical analysis

- Activation energy of lime cement containing pozzolanic materials

- Optimizing surface quality in PMEDM using SiC powder material by combined solution response surface methodology – Adaptive neuro fuzzy inference system

- Experimental study of the mechanical shear behaviour of steel rebar connectors in timber–concrete structure with leafy wood species

- Development of structural grade lightweight geopolymer concrete using eco-friendly materials

- An experimental approach for the determination of the physical and mechanical properties of a sustainable geopolymer mortar made with Algerian ground-granulated blast furnace slag

- Effect of using different backing plate materials in autogenous TIG welding on bead geometry, microhardness, tensile strength, and fracture of 1020 low carbon steel

- Uncertainty analysis of bending response of flexoelectric nanocomposite plate

- Leveraging normal distribution and fuzzy S-function approaches for solar cell electrical characteristic optimization

- Effect of medium-density fiberboard sawdust content on the dynamic and mechanical properties of epoxy-based composite

- Mechanical properties of high-strength cement mortar including silica fume and reinforced with single and hybrid fibers

- Study the effective factors on the industrial hardfacing for low carbon steel based on Taguchi method

- Analysis of the combined effects of preheating and welding wire feed rates on the FCAW bead geometric characteristics of 1020 steel using fuzzy logic-based prediction models

- Effect of partially replacing crushed oyster shell as fine aggregate on the shear behavior of short RC beams using GFRP rebar strengthened with TRC: Experimental and numerical studies

- Micromechanic models for manufacturing quality prediction of cantula fiber-reinforced nHA/magnesium/shellac as biomaterial composites

- Numerical simulations of the influence of thermal cycling parameters on the mechanical response of SAC305 interconnects

- Impact of nanoparticles on the performance of metakaolin-based geopolymer composites

- Enhancing mechanical and thermal properties of epoxy-based polymer matrix composites through hybrid reinforcement with carbon, glass and steel

- Prevention of crack kinetic development in a damaged rod exposed to an aggressive environment

- Ideal strain gauge location for evaluating stress intensity factor in edge-cracked aluminum plates

- Experimental and multiscale numerical analysis of elastic mechanical properties and failure in woven fabric E-glass/polyester composites

- Optimizing piezoelectric patch placement for active repair of center-cracked plates

- Experimental investigation on the transverse crushing performance of 3D printed polymer composite filled aluminium tubes

- Review Articles

- Advancing asphaltic rail tracks: Bridging knowledge gaps and challenges for sustainable railway infrastructure

- Chemical stabilization techniques for clay soil: A comprehensive review

- Development and current milestone of train braking system based on failure phenomenon and accident case

- Rapid Communication

- The role of turbulence in bottom-up nanoparticle synthesis using ultrafast laser filamentation in ethanol

- Special Issue on Deformation and Fracture of Advanced High Temperature Materials - Part II

- Effect of parameters on thermal stress in transpiration cooling of leading-edge with layered gradient

- Development of a piezo actuator-based fatigue testing machine for miniature specimens and validation of size effects on fatigue properties

- Development of a 1,000°C class creep testing machine for ultraminiature specimens and feasibility verification

- Special Issue on Advances in Processing, Characterization and Sustainability of Modern Materials - Part II

- Surface integrity studies in microhole drilling of Titanium Beta-C alloy using microEDM

- Experimental investigation on bacterial concrete by using Cantabro loss and UPV

- Influence of gas nitriding on the surface layer of M50 NiL steel for aerospace-bearing applications

- Experimental investigation on the spectral, mechanical, and thermal behaviors of thermoplastic starch and de-laminated talc-filled sustainable bio-nanocomposite of polypropylene

- Synthesis and characterization of sustainable hybrid bio-nanocomposite of starch and polypropylene for electrical engineering applications

- Microstructural and mechanical characterization of Al6061-ZrB2 nanocomposites fabricated by powder metallurgy

- Effect of edge preparation on hardness and corrosion behaviour of AA6061-T651 friction stir welds

- Mechanical improvement in acetal composites reinforced with graphene nanotubes and Teflon fibers using loss functions

- Experimental investigation on the mechanical properties of aluminum-based metal matrix composites by the squeeze casting method

- Investigation on punch force–displacement and thickness changes in the shallow drawing of AA2014 aluminium alloy sheets using finite element simulations

- Influence of liquid nitriding on the surface layer of M50 NiL steel for bearing applications

- Mechanical and tribological analyses of Al6061-GO/CNT hybrid nanocomposites by combined vacuum-assisted and ultrasonicated stir casting method

- Strengthening of structures with bacterial concrete for effective crack repair and durability enhancement

- Unique approaches in developing novel nano-composites: Evaluating their mechanical and tribological characteristics

- Load-carrying capacity of highly compact rigid deployable booms

- Investigating the influence of SiC and B4C reinforcements on the mechanical and microstructural properties of stir-casted magnesium hybrid composites

- Evaluation of mechanical and performance characteristics of bitumen mixture using waste septage ash as partial substitute

- Mechanical characterization of carbon/Kevlar hybrid woven 3D composites

- Development of a 3D-printed cervical collar using biocompatible and sustainable polylactic acid

- Mechanical characterization of walnut shell powder-reinforced neem shell liquid composite

- Special Issue on Structure-energy Collaboration towards Sustainability Societies

- Effect of tunneling conductivity of CNTs on the EMI shielding effectiveness of nanocomposite in the C-band

- Evaluation of the effect of material selection and core geometry in thin-walled sandwich structures due to compressive strength using a finite element method

- Special Issue on Sustainability and Development in Civil Engineering - Part III

- The optimum reinforcement length for ring footing resting on sandy soils resisting inclined load

- Special Issue on Advanced Materials in Industry 4.0

- Cross-dataset evaluation of deep learning models for crack classification in structural surfaces

- Mechanical and antibacterial characteristics of a 3D-printed nano-titanium dioxide–hydroxyapatite dental resin-based composite

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Probing microstructural evolution and surface hardening of AISI D3 steel after multistage heat treatment: An experimental and numerical analysis

- Activation energy of lime cement containing pozzolanic materials

- Optimizing surface quality in PMEDM using SiC powder material by combined solution response surface methodology – Adaptive neuro fuzzy inference system

- Experimental study of the mechanical shear behaviour of steel rebar connectors in timber–concrete structure with leafy wood species

- Development of structural grade lightweight geopolymer concrete using eco-friendly materials

- An experimental approach for the determination of the physical and mechanical properties of a sustainable geopolymer mortar made with Algerian ground-granulated blast furnace slag

- Effect of using different backing plate materials in autogenous TIG welding on bead geometry, microhardness, tensile strength, and fracture of 1020 low carbon steel

- Uncertainty analysis of bending response of flexoelectric nanocomposite plate

- Leveraging normal distribution and fuzzy S-function approaches for solar cell electrical characteristic optimization

- Effect of medium-density fiberboard sawdust content on the dynamic and mechanical properties of epoxy-based composite

- Mechanical properties of high-strength cement mortar including silica fume and reinforced with single and hybrid fibers

- Study the effective factors on the industrial hardfacing for low carbon steel based on Taguchi method

- Analysis of the combined effects of preheating and welding wire feed rates on the FCAW bead geometric characteristics of 1020 steel using fuzzy logic-based prediction models

- Effect of partially replacing crushed oyster shell as fine aggregate on the shear behavior of short RC beams using GFRP rebar strengthened with TRC: Experimental and numerical studies

- Micromechanic models for manufacturing quality prediction of cantula fiber-reinforced nHA/magnesium/shellac as biomaterial composites

- Numerical simulations of the influence of thermal cycling parameters on the mechanical response of SAC305 interconnects

- Impact of nanoparticles on the performance of metakaolin-based geopolymer composites

- Enhancing mechanical and thermal properties of epoxy-based polymer matrix composites through hybrid reinforcement with carbon, glass and steel

- Prevention of crack kinetic development in a damaged rod exposed to an aggressive environment

- Ideal strain gauge location for evaluating stress intensity factor in edge-cracked aluminum plates

- Experimental and multiscale numerical analysis of elastic mechanical properties and failure in woven fabric E-glass/polyester composites

- Optimizing piezoelectric patch placement for active repair of center-cracked plates

- Experimental investigation on the transverse crushing performance of 3D printed polymer composite filled aluminium tubes

- Review Articles

- Advancing asphaltic rail tracks: Bridging knowledge gaps and challenges for sustainable railway infrastructure

- Chemical stabilization techniques for clay soil: A comprehensive review

- Development and current milestone of train braking system based on failure phenomenon and accident case

- Rapid Communication

- The role of turbulence in bottom-up nanoparticle synthesis using ultrafast laser filamentation in ethanol

- Special Issue on Deformation and Fracture of Advanced High Temperature Materials - Part II

- Effect of parameters on thermal stress in transpiration cooling of leading-edge with layered gradient

- Development of a piezo actuator-based fatigue testing machine for miniature specimens and validation of size effects on fatigue properties

- Development of a 1,000°C class creep testing machine for ultraminiature specimens and feasibility verification

- Special Issue on Advances in Processing, Characterization and Sustainability of Modern Materials - Part II

- Surface integrity studies in microhole drilling of Titanium Beta-C alloy using microEDM

- Experimental investigation on bacterial concrete by using Cantabro loss and UPV

- Influence of gas nitriding on the surface layer of M50 NiL steel for aerospace-bearing applications

- Experimental investigation on the spectral, mechanical, and thermal behaviors of thermoplastic starch and de-laminated talc-filled sustainable bio-nanocomposite of polypropylene

- Synthesis and characterization of sustainable hybrid bio-nanocomposite of starch and polypropylene for electrical engineering applications

- Microstructural and mechanical characterization of Al6061-ZrB2 nanocomposites fabricated by powder metallurgy

- Effect of edge preparation on hardness and corrosion behaviour of AA6061-T651 friction stir welds

- Mechanical improvement in acetal composites reinforced with graphene nanotubes and Teflon fibers using loss functions

- Experimental investigation on the mechanical properties of aluminum-based metal matrix composites by the squeeze casting method

- Investigation on punch force–displacement and thickness changes in the shallow drawing of AA2014 aluminium alloy sheets using finite element simulations

- Influence of liquid nitriding on the surface layer of M50 NiL steel for bearing applications

- Mechanical and tribological analyses of Al6061-GO/CNT hybrid nanocomposites by combined vacuum-assisted and ultrasonicated stir casting method

- Strengthening of structures with bacterial concrete for effective crack repair and durability enhancement

- Unique approaches in developing novel nano-composites: Evaluating their mechanical and tribological characteristics

- Load-carrying capacity of highly compact rigid deployable booms

- Investigating the influence of SiC and B4C reinforcements on the mechanical and microstructural properties of stir-casted magnesium hybrid composites

- Evaluation of mechanical and performance characteristics of bitumen mixture using waste septage ash as partial substitute

- Mechanical characterization of carbon/Kevlar hybrid woven 3D composites

- Development of a 3D-printed cervical collar using biocompatible and sustainable polylactic acid

- Mechanical characterization of walnut shell powder-reinforced neem shell liquid composite

- Special Issue on Structure-energy Collaboration towards Sustainability Societies

- Effect of tunneling conductivity of CNTs on the EMI shielding effectiveness of nanocomposite in the C-band

- Evaluation of the effect of material selection and core geometry in thin-walled sandwich structures due to compressive strength using a finite element method

- Special Issue on Sustainability and Development in Civil Engineering - Part III

- The optimum reinforcement length for ring footing resting on sandy soils resisting inclined load

- Special Issue on Advanced Materials in Industry 4.0

- Cross-dataset evaluation of deep learning models for crack classification in structural surfaces

- Mechanical and antibacterial characteristics of a 3D-printed nano-titanium dioxide–hydroxyapatite dental resin-based composite