Abstract

The use of bacterial concrete has become popular as a way to fix fractures in a variety of constructions, including pavements, pipelines, canal linings, bridges, and reinforced concrete buildings. Concrete constructions frequently have cracks that let water and other chemicals in, weakening the structure and compromising reinforcement. Henk Jonkers came up with the idea of bacterial concrete to solve this issue. Concrete cracks were sealed experimentally using calcium lactate and Bacillus subtilis. The bacteria that were chosen were those that could thrive in alkaline conditions. M20 and M40-grade concrete mixes substituted river sand and crushed stone sand for fine aggregate with varying proportions of B. subtilis and calcium lactate. At various curing ages, the study looked at how bacteria affected abrasion resistance. For various mixtures, empirical relationships were proposed between various concrete properties and bacterial content.

1 Introduction

Substantial stands as the second most used substance internationally outperformed simply by water. Notwithstanding, it is powerless to the development of miniature breaks and contains pores, making it inclined to unfortunate outcomes. The presence of miniature breaks and pores makes pathways for the entrance of water and other destructive substances, prompting support erosion and the crumbling of cement. This brings about a decrease in substantial strength and solidness. Subsequently, significant expenses are brought about internationally for the maintenance and support of substantial designs [1]. Different procedures exist for fixing breaks, yet most customary fix frameworks depend on synthetic compounds, including broad work, accompany high costs, and posture ecological and wellbeing dangers. Currently, microbiologically prompted calcite precipitation has arisen as a compelling elective fix technique for fixing miniature breaks and pores in concrete. This bacterial remediation approach beats different techniques because of its profile-based nature, harmless to the ecosystem, cost viability, and supportability [2].

Urease-positive microscopic organisms have been distinguished as persuasive in the precipitation of calcium carbonate (calcite) by creating the protein urease. This protein works with the hydrolysis of urea into CO2 and smelling salts, bringing about elevated pH and precipitation of calcite inside the bacterial climate. This Inventive, eco-friendly technique was initially used for breaks fixing to prevent filtering in channels. The actuated calcite precipitation by Bacillus pasteurii and Bacillus sphaericus was viewed as compelling in remediating substantial breaks and further developing compressive strength [3]. In contrast with untreated regular substantial examples, the solidness of substantial examples treated with B. pasteurii displayed upgrades when presented with soluble, sulfate, and freeze–defrost conditions [4]. Substantial stands as the most broadly used building material, yet it has different restrictions regardless of its flexibility in development. It shows low rigidity, restricted flexibility, and insignificant protection from breaking. Over the long haul, continuous worldwide examination has provoked various changes to address the weaknesses of concrete cement. The ceaseless investigation of substantial innovation has brought about the improvement of specific substantial assortments that calculate building speed, substantial strength, sturdiness, and natural supportability. This progress includes consolidating modern materials like fly debris, impact heater slag, silica rage, metakaolin, and so forth [5,6].

Substantial strength stands apart as one of its vital characteristics, indicating its capacity to oppose applied loads. The assessment of substantial’s solidarity properties fills in as a basis for tolerating or dismissing its utilization in structures. Particularly, for applications like extensions, tall structures, and enormous designs, a high strength of cement is exceptionally alluring. Accomplishing high strength in concrete includes the joining of admixtures, a cycle that should not think twice about intrinsic strength. Notwithstanding strength, solidness also should be considered for substantial designs, characterized by the construction’s ability to persevere over a lengthy period without critical decay. A strong design adds to asset preservation by lessening the requirement for new structure materials and controlling the age of development squander, thus relieving ecological contamination. Monetarily, strong designs lead to bringing down costs related to fix and support. Prominently, high strength alone does not ensure substantial solidness, as the presence of miniature breaks and pores in concrete adds to expanded penetrability. This uplifted porousness works with the entry of water and different substances, starting erosion of support – an essential driver of substantial decay and compromised strength [7,8].

The presentation of self-mending specialists and the use of strengthening cementitious materials, for example, silica seethe and metakaolin, can altogether decrease the porousness of cement. Microscopic organisms encourage the mending of pores and miniature breaks in concrete through calcite precipitation and offer a feasible choice for bioremediation in substantial designs. These microscopic organisms have the capacity to draw in calcium particles from their environmental elements and produce a urease catalyst. The urease breaks down urea, bringing about the age of carbon dioxide and alkali. This interaction increases the pH, prompting the blend of calcium particles with carbon dioxide and ensuing calcite precipitation (CaCO3). Fundamental qualities for microorganisms appropriate for substantial use are capacity to frame endospores, which can endure the unforgiving substantial climate, remaining lethargic for long duration, even as long as 200 years. At the point when structure breaks, water and air invade the substantial, making great circumstances for endospore germination. When developed, the microorganisms precipitate calcite to seal the pores and breaks in the substantial. There are several benefits of using adverse effects as beneficial cementitious materials in substantial construction, including increased strength and durability as well as environmental and energy conservation [9,10]. The cost related to bacterial cement is supposed to be higher than that of regular cement. The essential expense-driving variable in bacterial treatment is the substrate expected for bacterial development. The use of additional practical substrates can really lessen the general expense of bacterial cement. Bacterial has long-term financial benefits by reducing break repair and maintenance expenses, regardless of the initial cost. In ongoing turns of events, microbial mineral precipitation, because of the metabolic exercises of useful microorganisms in concrete, has altogether worked on the general execution of cement. This interaction can happen both inside and outside microbial cells or inside the substantial, even at some distance. Bacterial tasks normally prompt changes in arrangement science, prompting overimmersion and the resulting precipitation of minerals. Executing these standards of bio-mineralogy in substantial opens up opportunities for the production of an original material known as bacterial cement [11,12].

The bacteria selected for integration into concrete as a self-healing mechanism must possess attributes conducive to long-term crack protection, ideally sustaining efficacy throughout the lifespan of the buildings. The fundamental process involves these bacteria acting as catalysts, converting precursor components into suitable filler materials, such as mineral precipitates based on calcium carbonate, functioning akin to bio-cement to effectively seal newly formed fissures. To ensure a successful self-healing process, both bacteria and a precursor compound for bio-cement need introduction into the material matrix. However, the presence of these embedded bacteria and precursor compounds must not compromise other essential concrete characteristics. Certain alkali-resistant bacteria, particularly a distinct group capable of forming spores, exhibit a mechanism to resist assimilation into the concrete matrix. These spores, akin to plant seeds, remain viable for extended periods, enduring environmental stresses for over 50 years in dry conditions. Yet, when directly incorporated into concrete, their lifespan diminishes significantly to 1–2 months due to the continuous cement connection, resulting in pore diameters smaller than the microorganism spores. In addition, concerns arise regarding the potential unintended impact on other concrete properties when immediately adding organic bio-mineral precursor molecules to the concrete mix. Previous studies have shown that components like yeast extract, peptone, and calcium acetate led to a notable decrease in compressive strength, except for calcium lactate, which resulted in a 10% increase in compressive strength compared to reference samples.

The research endeavors to delve deeper into the realm of bacterial concrete by investigating its resistance to abrasion, a crucial factor in assessing its durability and long-term performance. Abrasion resistance is vital for structures subjected to heavy foot traffic or vehicular loads, as it determines the material’s ability to withstand wear and maintain structural integrity over time. Through comprehensive testing and analysis, the study aims to provide valuable insights into how bacterial concrete fares under abrasive conditions compared to conventional concrete. Furthermore, the utilization of ultrasonic pulse velocity (UPV) measurement techniques offers a nondestructive means of evaluating the dynamic modulus of elasticity of bacterial concrete. This parameter is fundamental in understanding the material’s ability to withstand dynamic loads and vibrations, thus influencing its suitability for various construction applications. By combining these analytical approaches, the research seeks to contribute to the advancement of knowledge in the field of bacterial concrete technology, paving the way for its wider adoption in sustainable construction practices. Krishna Rao et al. explored the effect of M-sand on fly debris roller compacted concrete (FRCC) strength and scraped area opposition. The concrete was somewhat supplanted by fly debris at four substance levels, for example, 0, 20, and 60%. The design of the FRCC blends consolidates a flexural obstruction of 5 MPa. Fine totals of three blends (Series A, Series B, and Series C) were started in FRCC blends, explicitly stream sand (100%), M-sand (100%), and waterway sand and M-sand mixes (50% each). All blends persevere through strength checking (pressure and flexure) and two scraped spot opposition testing procedures (Cantabro test and surface scraped area obstruction test) at 3, 7, 28, and 90 days. Trial discoveries demonstrate that in each of the three series of blends, the deficiency of Cantabro and weight reduction of surface scraped spot have been upgraded with an ascent in fly debris content at all ages. As opposed to waterway sand blends, notwithstanding, the pace of rise is decreased with the expansion of M-sand in FRCC. Connections have been made among strength and scraped area obstruction for every one of the three arrangements of blends. A model was recommended between the deficiency of Cantabro and the deficiency of FRCC surface scraped spot weight independent of substantial age, sort of good total, and extent of fly debris substitute [13]. Siddique et al. explored because of bacterium on the properties of cement comprised of rice husk debris (RHA). Regular cement has been intended to possess a 28-day strength of 32.8 MPa. Concrete was part of the way supplanted by RHA inside the ordinary cement (0, 5, 10, 15, and 20% by weight). Then, at that point, while making concrete, microorganism genuine microscopic organisms aerius (105 cells/mL) were blended in water. For all substantial blends with and keeping in mind that not bacterium, tests were led for compressive strength, water retention, porosity, chloride permeability, and scraped area opposition up to the age of 56 days. Results showed that microscopic organisms’ consideration in RHA-concrete even a tiny bit ages gathered their compressive strength. With 100% RHA, in any case, the least complex presentation was accomplished, with 28-day compressive strength being 36.1 and 40.0 MPa with bacterium. The consideration of microorganism in RHA concrete, because of fight precipitation, decreased its water retention and permeability, which progressively works on these properties. Examination of SEM and XRD showed the arrangement of ettringite in pores, calcium silicate hydrate, and fight that densified the substantial. Also, this study demonstrated the shower of RHA and microorganism improves substantial’s toughness properties [7]. Krishna Rao et al. explored the ultrasonic heartbeat speed (UPV) tests on roller compacted substantial asphalt (RCCP) material containing as mineral admixture classification fly debris F. During this exploratory work, waterway sand, M-sand, and mix of M sand and stream sand are utilized as a fine mix. Three types of compacted substantial fly debris roller blends are prepared, which are higher than three types of fine totals and are chosen as Series A (waterway sand), Series B (fabricated sand), and Series C (stream sand and M-sand mix). The debris content in each series fluctuates from 0 to 60% rather than concrete. Forty-two block examples are casted and tried for compressive strength and UPV in each series and for different recuperating ages (e.g., 3, 7, 28, and 90 days). Fly debris containing roller compacted substantial asphalt (FRCCP) UPV results show lower esteems generally told consolidates even the slightest bit ages from 3 to 90 days contrasted with oversee blend concrete (0% fly debris). Nonetheless, in contrast with Series A blends with fly debris, Series B and C blends with fly debris show higher winds up in UPV values, compressive strength, and dynamic versatile module. Connections are produced for all series blends between the compressive strength of FRCCP and UPV and dynamic modulus. To work out the FRCCP dynamic modulus, a fresh out of the box new experimental condition is arranged. The RCC ultrasonic rate increases with fly debris, as a partial replacement of concrete will rise with even minimal increments in cementing levels across three distinct mixture series. Sequential A, B, and C blends supplemented with fly debris, compressive strength, UPV, and dynamic actual property modules are decreased by expanding the fly debris content. This can take even 90 years to lower the strength commitment of fly debris to solidify. The Series B blends have better UPV, strength, and dynamic stiffness when the fine mix is 100% sand. These benefits have nothing to do with the Series A blends. It is because M-sand produces brutal blends and needs extra water/concrete quantitative connection than conventional cement containing fine mix conduit sand. Sequential C blends where the fine mix is equal parts M-sand (50%) and stream sand (50%) produced better results, including higher UPV and dynamic property module levels with just the smallest amount of debris replacement. This can be a result of right mix that gathered the pressing thickness. For Series A blends at 40, 50, and 60% substitution levels, for series B blends at 30, 40, 50, and 60% substitution levels, and for series C blends at 50 and 60% substitution levels, the norm of roller compacted concrete with fly debris at 3 days is questionable. Series A and B made RCC of questionable quality at 50 and 60% substitution level at 7 days. However, all blends made mid-range quality to brilliant quality blends sequential C blends at 7 days age, and in this way, M-sand is much of the time considered a halfway substitute for waterway sand. Exclusively series and Series B blends at 28 days age made dubious quality at the fly debris substitution level of 60% [14]. Jonkers examined the development of breaks in many substantial developments on a commonplace solidness-related peculiarity. In this review, microorganisms immobilized in permeable extended dirt particles before the expansion of a substantial combination can considerably increase bacterially interceded self-mending contrast with the direct unprotected expansion of microscopic organisms to the substantial blend according to a past report. The consequences of this review appear to be encouraging as 100% fix (6 out of 6 examples tried) of breaks actuated in 2 months relieved bacterial examples happened rather than 33% fix (two of six examples tried) of customary substantial examples. Tests showed that bacterial spore suitability expanded by adding immobilized (secured) particles inside permeable extended mud contrasted with the direct (unprotected) option to the substantial blend from 2 months to over a half year. Constant investigations connect with additional evaluation of break recuperating, for example, laying out the connection between added recuperating specialist amount and successful mending of break profundity and width. Hence, dynamic bacterially interceded mineral precipitation can prompt effective break connecting and accompanying decreased material porousness. Joined with porousness tests, minuscule strategies uncovered that total break recuperating happened in bacterial concrete and just somewhat in ordinary cement. In bacterial concrete, a break-mending component presumably occurs through the metabolic change of calcium lactate to calcium carbonate bringing about break arrangement. The result of this biochemically intervened technique was a successful fixing of submillimeter-sized breaks (0.15 mm wide). This work shows that the projected two-part biochemical mending specialist, comprising microorganism spores related to a relevant natural bioconcrete forerunner compound, abuse permeable extended dirt particles as a supply, might be a promising bio-based compound, thus showing a property different to a stringent substance or concrete-based recuperating specialists, and this shows that substantial parts of a development are not open for manual examination or fix [15]. Chidara et al. researched on accomplishing early compressive strength in concrete not set in stone as a test. To achieve the objective, analysts have attempted different admixtures. This business locales the issue of early utilization of microbes alluded to as Sporosarcina pasteurii to achieve compressive strength in concrete. Inside the presence of any carbonate supply, the microscopic organisms are described by the compressive solidarity to hasten carbonate and are thought for their resistive abilities in warmth. Around 192 substantial 3D shapes were tried at 3, 7, 14, and 28 days; furthermore, the outcomes contrasted with regular cement to find out the objective of acquiring early strength. The microbes were used in synthetic compounds blend, and furthermore, the endless amount extents were adjusted to accomplish the predefined compressive strength of M20 at 28 days. It very well reasoned that the application of S. pasteurii results in an increase in strength and furthermore prompts an expansion in concrete compressive strength. The outcomes obtained from every urea and sodium carbonate are viewed as almost comparable and sodium carbonate will consequently try and be utilized as a substitute for improving substantial strength. The absolute best compressive strength gain was accomplished by adding to the substantial combination admixture comprising sodium carbonate and salt. The expansion of S. pasteurii admixture did not affect either the downturn or the underlying substantial setting time [16]. Palin et al. explored a self-mending building material composite upheld microorganism to be utilized in marine conditions at low temperatures. Through break water porosity estimations and strength advancement through pressure testing, the composite was tried for its break recuperating capacity. The composite showed awesome break mending capacity, diminishing break porosity by 95% 0.4 mm wide, and breaks 0.6 metric direct unit wide by 92% when 56 days of submersion in fake H2O at 8°C. Self-delivered precipitation, independent dab expanding, magnesium-based mineral precipitation, and calcium-put together mineral precipitation in and with respect to were ascribed to the recuperating of breaks. Also, mortar examples consolidated with globules showed lower compressive qualities than plain mortar examples. This study is the underlying to gift a microbe-based self-recuperating established composite for application in marine conditions at low temperatures, while the development of a microorganism-impelled natural inorganic composite mending material is partner energizing road for substantial self-recuperating examination [17]. Schlangen and Sangadji explored oneself recuperating procedures in three entirely unexpected materials. Bacteria are utilized for the essential application to accelerate fight into substantial breaks. This technique does not fill nearly gigantic breaks in ferroconcrete. The system does not prompt construction strength improvements, but the path to support is hindered by filling the break. This stops the passage of fluids and particles starting to support consumption and thus improves the construction’s durability. Moreover, this system is helpful for structures that hold water. This empowers breaks to be full and the getaway is halted. It is problematic or unrealistic to fix microorganism concrete, especially in underground designs. During this case, strain solidifying composite (SHCC) materials are examined, which as a result of their small break widths have previously had a high potential for self-recuperating. New increases, similar to microfibers and very retentive polymers (SAP), are even advancing this capacity for self-stopping. For asphalt cement, using standardized oil and micro steel filaments can increase recovery capacity. The last option approach has very much attempted to work inside the lab and is being applied inside the Netherlands in 2010 on a genuine street [18]. Abo-El-Enein et al. researched on improving concrete sand mortar strength and water assimilation by the precipitation of carbonate microbiologically evoked. The mixing water integrated a tolerably alkalophilic oxygen-consuming S. pasteurii at changed cell focuses. The review showed that by adding in regards to one optical thickness (1 OD) of microorganism cells with joining water, a 33% expansion in compressive strength of concrete mortar was accomplished in 28 days. Improvement in strength and water retention is a direct result of the extension of fight precious stones among the pores of the concrete sand network as shown by the microstructure obtained from filtering microscopy (SEM) assessment. Concrete mortar water retention decreases with microorganism cell fixation, while compressive strength increases based on 1 OD. A decrease in strength improvement was fixed when 1.5 OD of microorganism cell. Subsequently, the ideal convergence of microorganism cells that winds up in the best mortar improving offers higher compressive strength and lower assimilation of water is 1 OD [19]. Gupta et al. led a survey on the most recent self-recuperating strategies and owed to very surprising burden and nonload factors, and break development in substantial designs is unavoidable due to decay all through its administration life. To prevent breaks from spreading and diminishing the assistance lifetime of the designs, fix and upkeep tasks square measure so required. Openness to broken zone will be troublesome; moreover, such tasks need capital and work and add to contamination on account of phylogenesis exercises and furthermore the utilization of extra fix materials. Self-mending will be the approach to decreasing manual mediation. Independent break waterproofing because of carbonate precipitation evoked by microorganism is harmless to the ecosystem instrument that few specialists round the world square measure seriously finding out. This survey centers around evaluating break mending by microorganism once it is straightforwardly valuable or strengthening to the substantial when exemplification into a safeguarding shell. Four key angles that confirm the adequacy of microorganism self-mending are featured and talked about: case material and bio-specialist epitome, container endurance all through substantial intermixture, the effect on substantial properties of adding bio-specialists or cases, and furthermore the capacity to seal and recuperate mechanical and solidness properties [20]. Tziviloglou et al. examined the creative self-mending substantial innovation that allows the texture to fix the open miniature breaks that, because of the entrance of gasses and fluids, will make peril the construction’s durability. Totally various thoughts of substantial self-recuperating are created with the point of debilitated once breaking water snugness. Among these, self-mending concrete upheld microorganism has shown promising prompts for the exhibition of break waterproofing. The mending specialist upheld that microorganism is consolidated in lightweight totals during this review and blended in with late mortar. This upgrades self-created substantial mending and is fit for wiped out water snugness once the texture is broken. The review centers around the effect of the recuperating specialist once integrated into the mortar network and assessing the recuperation of fluid snugness once breaking and openness through water porousness tests to two totally unique mending systems (water submersion and wet-dry cycles). It had been found that the presence of the mending specialist does not affect the compressive strength of the mortar containing lightweight totals. The review uncovers that once submerged in water, the recuperation of water snugness does not take issue impressively either with or without a mending specialist. When compared to examples without the mending professional, the recovery of water snugness will significantly increase for examples with the specialist after being exposed to wet-dry cycles. Estimations of oxygen focus and microorganism follow on fight developments affirmed the microorganism action of the mending specialist on examples [21–23,25]. Furthermore, the utilization of UPV measurement techniques offers a nondestructive means of evaluating the dynamic modulus of elasticity of bacterial concrete. This parameter is fundamental in understanding the material’s ability to withstand dynamic loads and vibrations, thus influencing its suitability for various construction applications. By combining these analytical approaches, the research seeks to contribute to the advancement of knowledge in the field of bacterial concrete technology, paving the way for its wider adoption in sustainable construction practices.

2 Materials and testing methods

This section delves into the detailed materials and testing procedures employed in the research. The study focuses on the utilization of calcite lactate and Bacillus subtilis in varying proportions of 5, 10, and 15% relative to the weight of the cement. This innovative approach involves blending crushed stone and river sand mixtures to formulate concrete of grades M20 and M40.

2.1 Cement

This study employed Grade 53 Ordinary Portland cement for its experiments, and an exhaustive analysis of its diverse characteristics was conducted in accordance with the specifications outlined in IS: 4031-1996 [82]. The assessment procedure adhered strictly to the guidelines, ensuring a comprehensive examination of the cement’s properties.

2.2 Fine aggregates

The fine aggregates employed in the research consisted of river sand and crushed stone sand sourced locally for their regional availability. These materials underwent detailed scrutiny of their gradation characteristics, a critical process for comprehending the composition and quality of the fine aggregates. Such analysis plays a pivotal role in shaping the performance of the concrete mix overall.

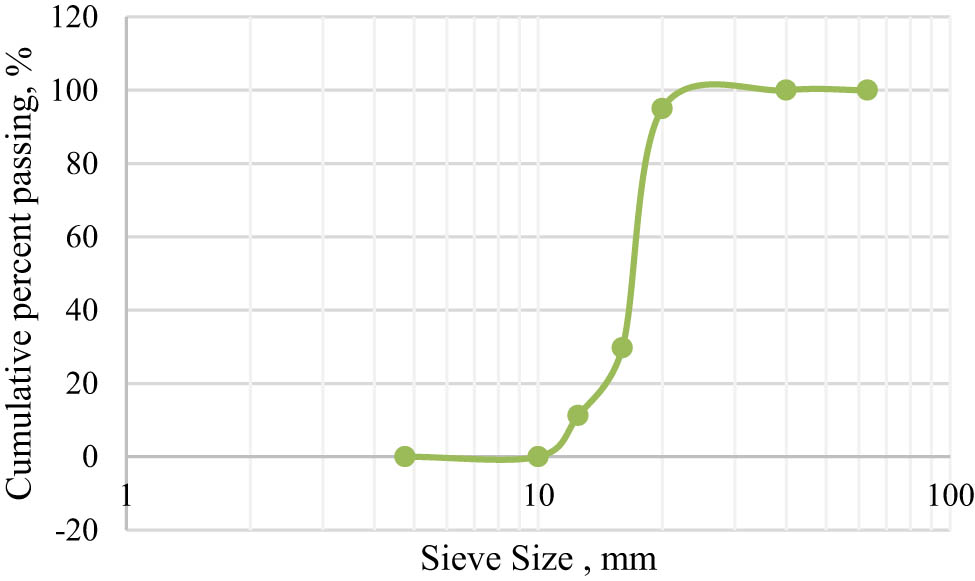

2.3 Coarse aggregates

For this investigation, the coarse aggregate element comprised crushed granite broken stone with a nominal size of 20 mm. This meticulously chosen material was selected due to its durability and appropriateness for use in concrete applications. The grading properties of the coarse aggregate underwent systematic analysis, and the findings are illustrated in Figure 1, depicting the dispersion of particle sizes within the designated range.

Grading curve of coarse aggregate.

2.4 Water

The main mixing media used in the production of the concrete for this investigation is freshwater. The integrity of the concrete mixture is guaranteed by the use of freshwater that satisfies accepted quality standards.

2.5 Calcium lactate

In this research, calcium lactate (C6H10CaO6) played a crucial role, shown in Figure 2, functioning as a fundamental ingredient alongside B. subtilis within the nutrient broth. Presenting as a powdered substance with a recognizable white hue, calcium lactate contributed to the nutritional composition required for the experimental concrete formulations. Its incorporation into the mixture aimed to augment specific properties or functionalities, leveraging its attributes as a calcium salt derived from lactic acid. The powdered form facilitated seamless integration into the concrete blend, ensuring a homogeneous dispersion of the compound. The collaborative interplay between calcium lactate and B. subtilis exemplifies the innovative methodology employed in this study, highlighting the adaptability of such additives in influencing concrete characteristics.

Calcium lactate and Bacillus subtilis.

2.6 Cantabro loss abrasion resistance test

The Los Angeles abrasion testing apparatus is employed to assess the weight loss of cylindrical specimens measuring 150 mm in diameter and 100 mm in length, adhering to the specifications outlined in ASTM C1747-201188. Enclosed within a hollow drum rotating at a speed of 30–33 revolutions per minute until reaching 300 revolutions, three specimens are allowed to interact, rubbing and striking against each other. Subsequently, the specimens are removed and weighed. The percentage of weight loss is calculated using the following equation:

M 2 represents the average mass of the three test specimens in grams after 300 rotations, while M 1 denotes the average mass of the three test specimens in grams before being introduced into the Los Angeles abrasion machine. Conversely, test specimens comprising bacterial concrete with crushed stone sand and river sand are exposed to abrasion forces in an LA abrasion machine, undergoing speeds of 50, 100, 150, 200, 250, and 300 rpm in the course of experimental investigations.

2.7 UPV test

The UPV method stands out as the most practical and nondestructive means of assessing concrete quality and detecting any internal flaws like cracks or voids. Operating within a frequency range of 20–150 kHz, beyond the range of human hearing (20 kHz), ultrasonic waves are chosen for their travel distances, ranging from 1,500 to 500 mm. This method employs one ultrasonic pulse generator, two transducers, a cathode ray oscilloscope (CRO), and a digital time display device. Transducers, which can convert physical quantities like temperature, pressure, or sound into electrical signals and vice versa, are essential components. Among various types of transducers, ultrasonic transducers are employed here. One transducer is connected to the ultrasonic pulse generator and placed at one end of the concrete specimen, while another transducer is affixed to the opposite end. These transducers are affixed to the concrete using grease or jelly. The transmitting transducer sends the ultrasonic pulse into the concrete, where three types of waves propagate, such as longitudinal waves, transverse (shear) waves, and surface (Rayleigh) waves. The time taken for the ultrasonic pulse to travel through the concrete is recorded by the digital time display unit and can also be observed on the CRO screen. By measuring the time interval between the leading edges of the transmitted and received pulses, the transit time of the ultrasonic pulse through the concrete can be determined.

A shorter transit time indicates higher pulse velocity, which correlates with better concrete quality. However, it is important to note that while UPV is effective in detecting flaws and assessing certain properties of concrete, such as dynamic Young’s modulus velocity, it is not sufficient for determining compressive strength, as this depends on various factors including concrete composition, mixing methods, environmental conditions, and others.

where g is the acceleration due to gravity (m/s2).

The time the pulses take to travel through the concrete specimen recorded. Then the velocity is equal to

Once the velocity is established, the concrete’s quality, homogeneity, strength, density, and conditions are attained. Table 1 from IS 13311(Part1): 1992 illustrates the concrete’s quality in terms of pulse velocity (km/s).

Quality of concrete as a function of UPV

| S. no. | Pulse velocity cross probing (km/s) | Concrete quality grading |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | >4.5 | Excellent |

| 2 | 3.5–4.5 | Good |

| 3 | 3.0–3.5 | Medium |

| 4 | <3.0 | Doubtful |

All cubic samples undergo UPV testing following the guidelines outlined in IS: 13311(Part 1): 1992. The UPV testing apparatus, commonly known as the PUNDIT device, comprises two transducers: a transmitting unit and a 54 kHz receiver head, alongside an ultrasonic tester.

Each cubic specimen is subjected to testing on three distinct facets: Facet 1 (F1), which corresponds to the direction of casting, Facet 2 (F2), and Facet 3 (F3), at various stages of bacterial concrete maturity. The dynamic modulus of elasticity for bacterial concrete can be determined using the following formula:

where

For the purpose of calculations in this experimental work,

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Effect of bacteria on abrasion resistance of bacterial concrete

This section examines the Cantabro loss, expressed as a percentage weight loss, across different concrete mixes containing varying proportions of bacterial solution – specifically, 5, 10, and 15% of the cement weight for both M20 and M40-grade concrete.

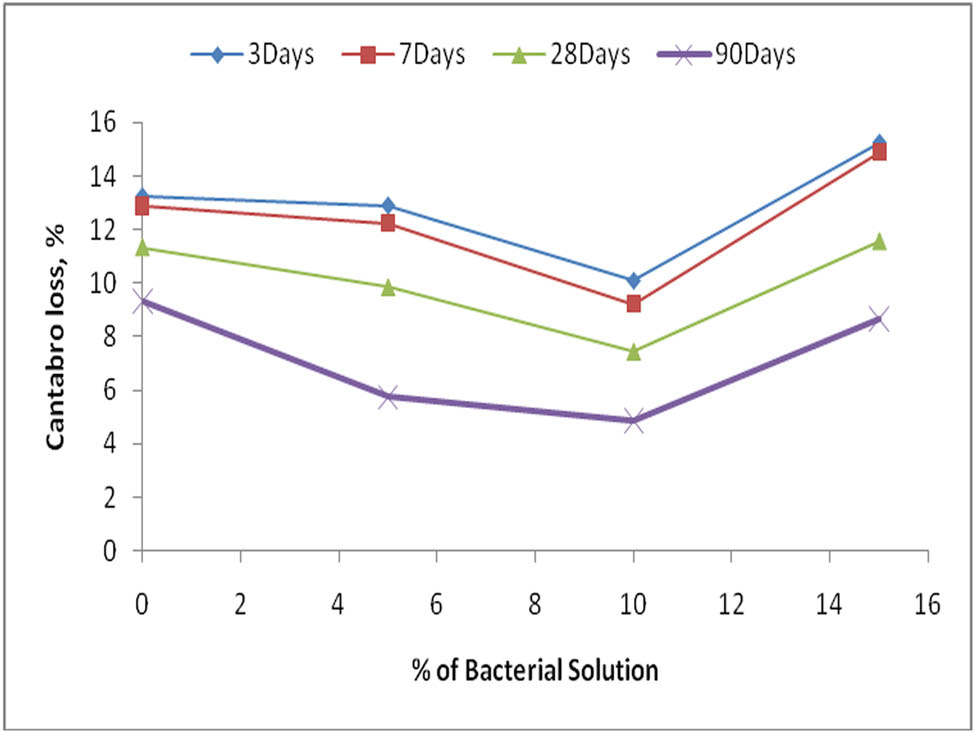

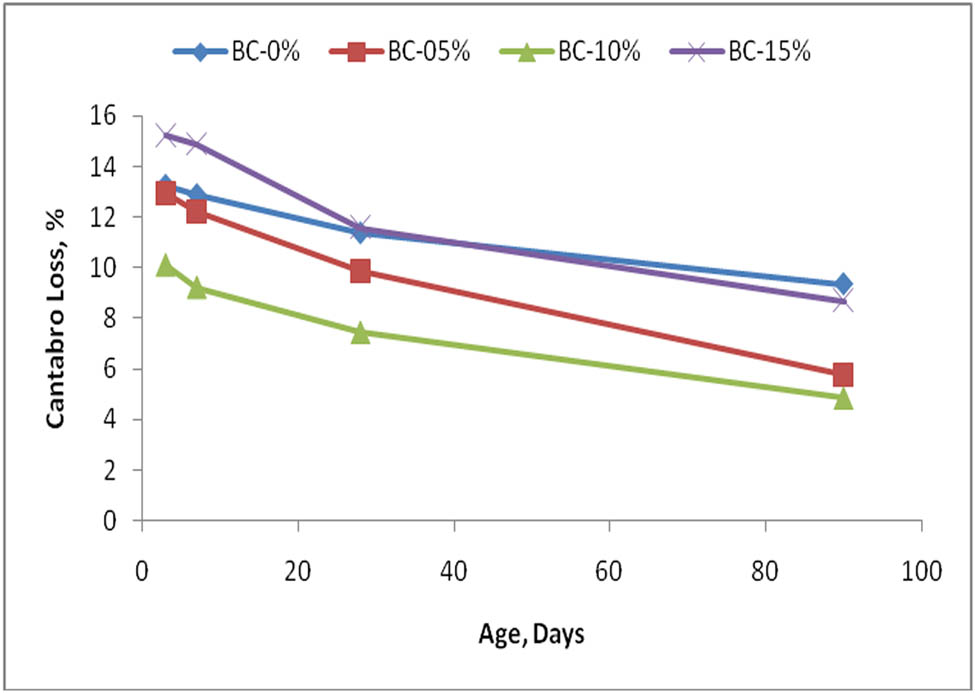

3.1.1 Cantabro loss (% weight loss) of M20-grade concrete

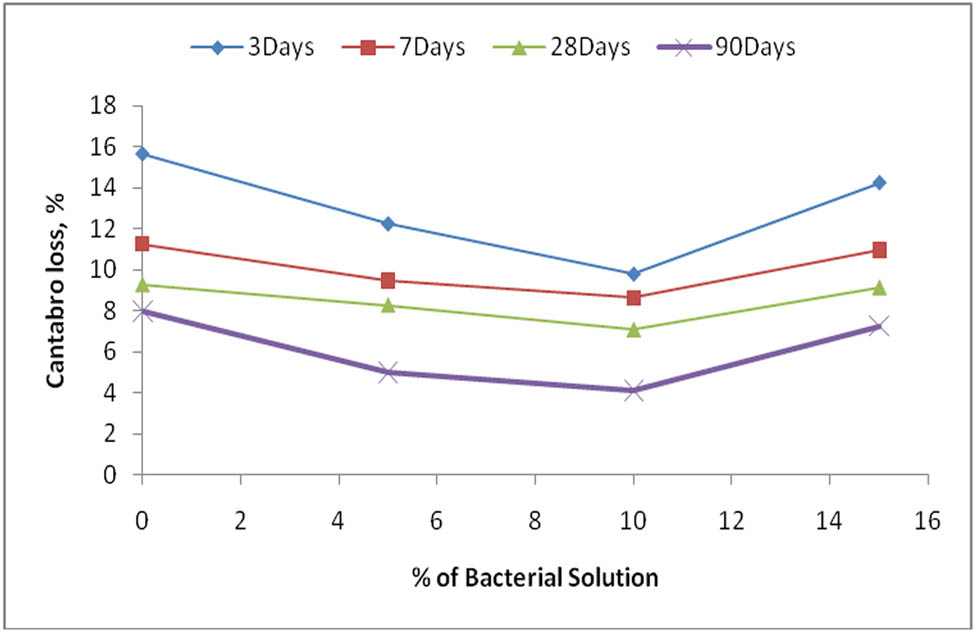

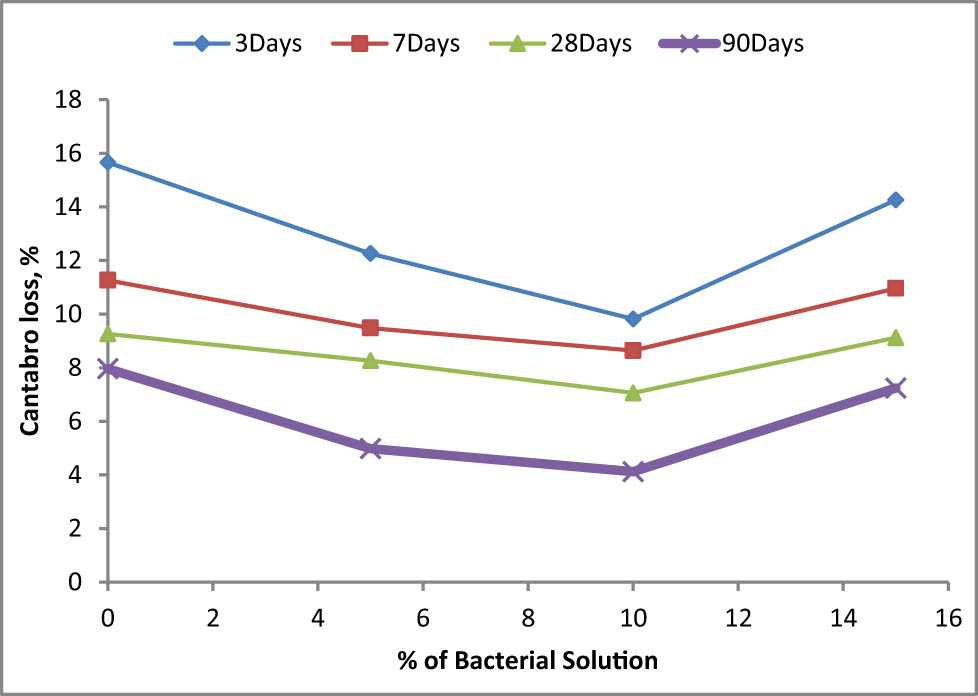

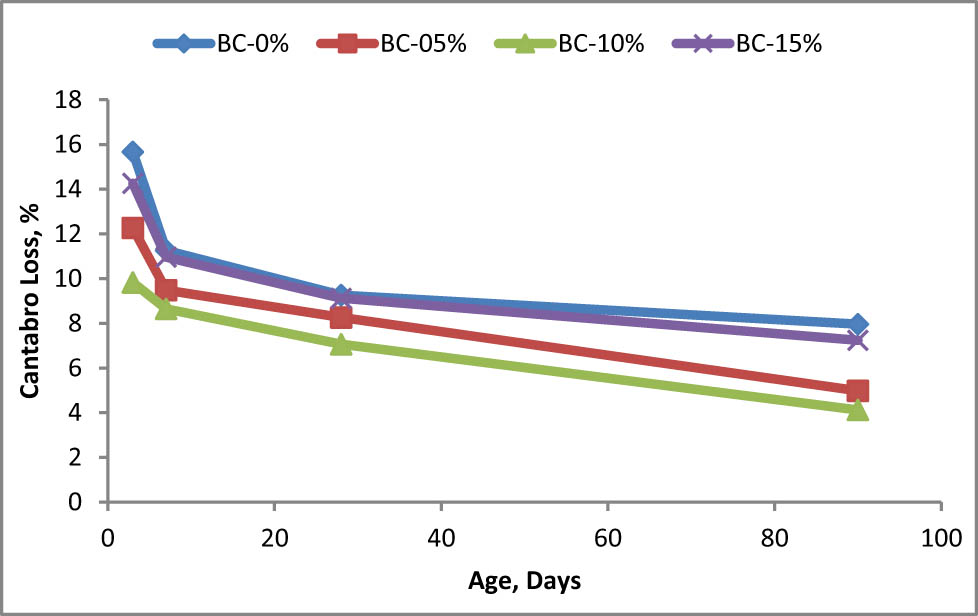

Testing was done on the abrasion resistance of bacterial concrete mixtures after 3, 7, 28, and 90 days. The percentage weight loss is used to calculate the Cantabro loss. The experimental values for river sand mixes and crushed stone sand mixes for M20-grade concrete at 3, 7, 28, and 90 days. Based on the findings, it can be shown that for all bacterial concrete mixes at 3, 7, 28, and 90 days, the percentage of weight loss, or Cantabro loss, increased as the number of rotations increased (from 50 to 300). The variance in Cantabro loss, or weight loss, at 300 revolutions for various mixtures of bacterial concrete is displayed in Figures 3 and 4.

Cantabro loss at different bacteria solutions for river sand mixes.

Cantabro loss at different curing age for river sand mixes.

The proportion of cement substitution increased by weight in place of bacterial solution. The abrasion resistance of bacterial concrete mixes reduced as the bacterial solution increased by up to 10% due to a reduction in Cantabro loss. For traditional concrete made with river sand, the Cantabro loss at 28 days is 13.76%. For M20 grade concrete, the Cantabro loss increased to 10% with a 15% increase in bacterial solution. This is because there is a noticeable amount of calcium lactate present.

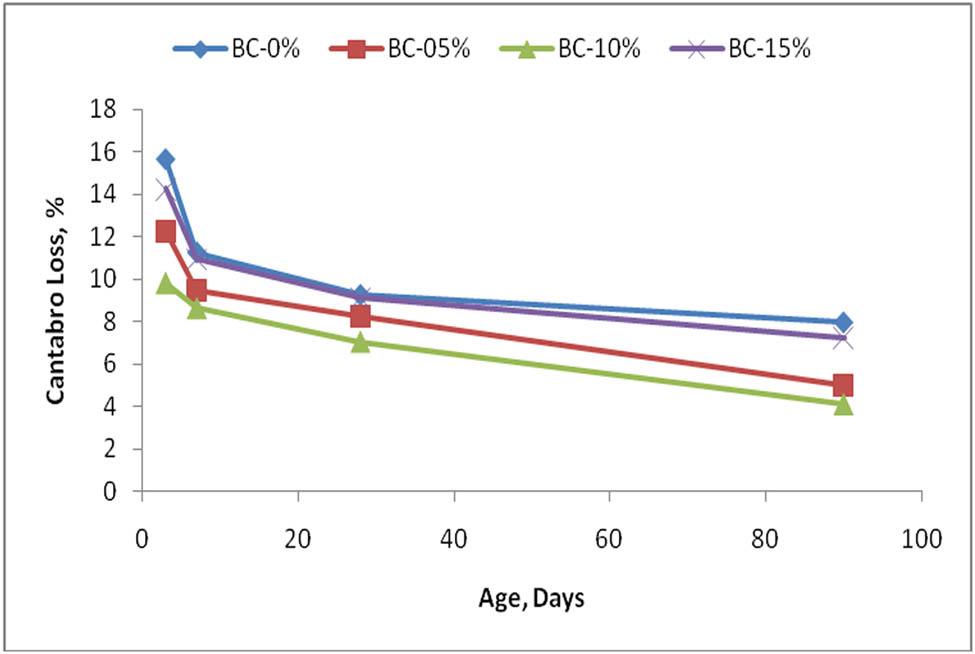

3.1.2 Effect of crushed stone sand on Cantabro loss for bacterial concrete mixes (M20 grade concrete)

Specimens were examined for all mixes of bacterial concrete at 50, 100, 150, 200, 250, and 300 revolutions per minute in the Los Angeles machine using the Cantabro test, which simulates abrasion with impact effect. The test findings at ages of 3, 7, 28, and 90 days are displayed in Figures 5 and 6, and the Cantabro loss rose as the Los Angeles machine’s rotations grew. It is evident from the discussion earlier that river sand mixes have higher Cantabro loss values than crushed stone sand mixes. This suggests that crushed stone sand significantly enhances the abrasion resistance of bacterial concrete mixtures at all ages, measured in terms of Cantabro loss.

Cantabro loss at different bacteria solutions for crushed stone sand mixes.

Cantabro loss at different curing age for crushed stone sand mixes.

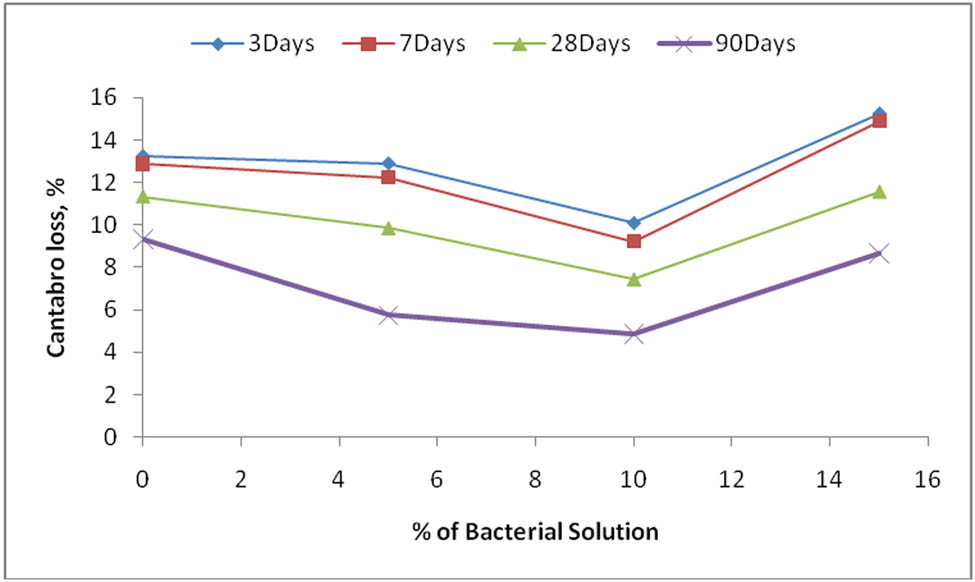

3.1.3 Cantabro loss (% weight loss) of M40-grade concrete

Testing was done on the abrasion resistance of bacterial concrete mixtures after 3, 7, 28, and 90 days. The percentage weight loss is used to calculate the Cantabro Loss. For M40-grade concrete, the experimental results were shown at 3, 7, 28, and 90 days for river sand mixes and crushed stone sand mixes. From the data, it can be shown that for all bacterial concrete mixes at 3, 7, 28, and 90 days, the percentage of weight loss, or Cantabro loss, rose as the number of rotations increased (from 50 to 300).

The variance in Cantabro loss, or weight loss, during 300 revolutions for various mixtures of bacterial concrete is displayed in Figures 7 and 8. An increase in the proportion of cement substitution by weight in place of bacterial solution. The abrasion resistance of bacterial concrete mixes reduced as the bacterial solution increased by up to 10% due to a reduction in Cantabro loss. For traditional concrete made with river sand, the Cantabro loss at 28 days is 11.36%. For M40-grade concrete, the Cantabro loss rose to 10% solution with a 15% rise in bacterial solution. This is because there is a noticeable amount of calcium lactate present.

Cantabro loss at different bacteria solutions for river sand mixes.

Cantabro loss at different curing age for river sand mixes.

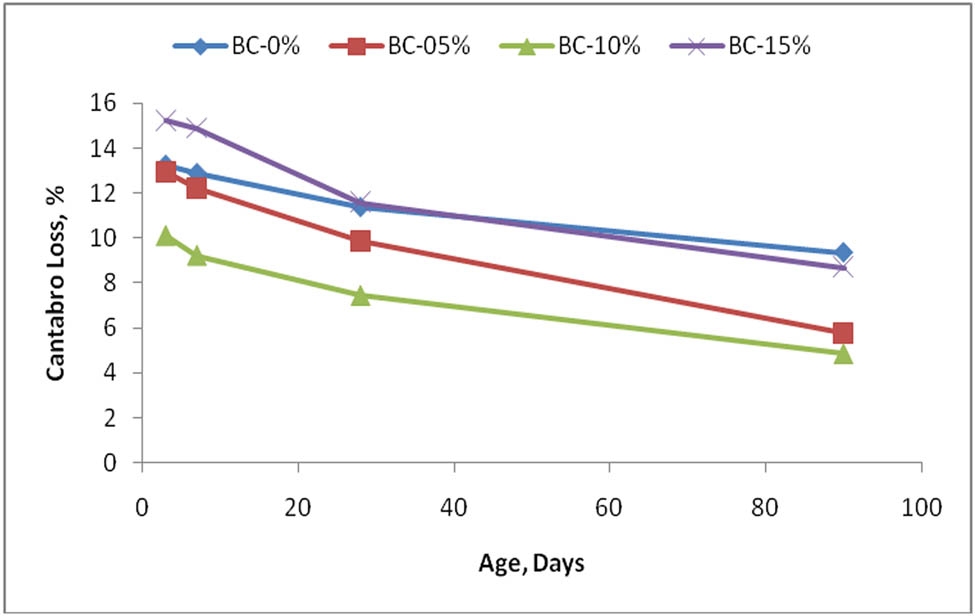

3.1.4 Effect of crushed stone sand on Cantabro loss for bacterial concrete mixes (M40-grade concrete)

Specimens were examined at 50, 100, 150, 200, 250, and 300 revolutions in the LA machine for all mixtures of bacterial concrete, based on the Cantabro test, which simulates the abrasion with impact effect. At the ages of 3, 7, 28, and 90 days, the test results are displayed in Figures 9 and 10, and the Cantabro loss rose as the Los Angeles machine’s rotations grew. It is evident from the aforementioned discussion that river sand mixes have higher Cantabro loss values than crushed stone sand mixes. This suggests that crushed stone sand significantly enhances the abrasion resistance of bacterial concrete mixtures at all ages, measured in terms of Cantabro loss.

Cantabro loss at different bacteria solutions for crushed stone sand mixes.

Cantabro loss at different curing age for crushed stone sand mixes.

3.2 Studies on ultrasonic pulse velocity of bacterial concrete

3.2.1 Effect of bacterial solution on UPV of bacterial concrete with days

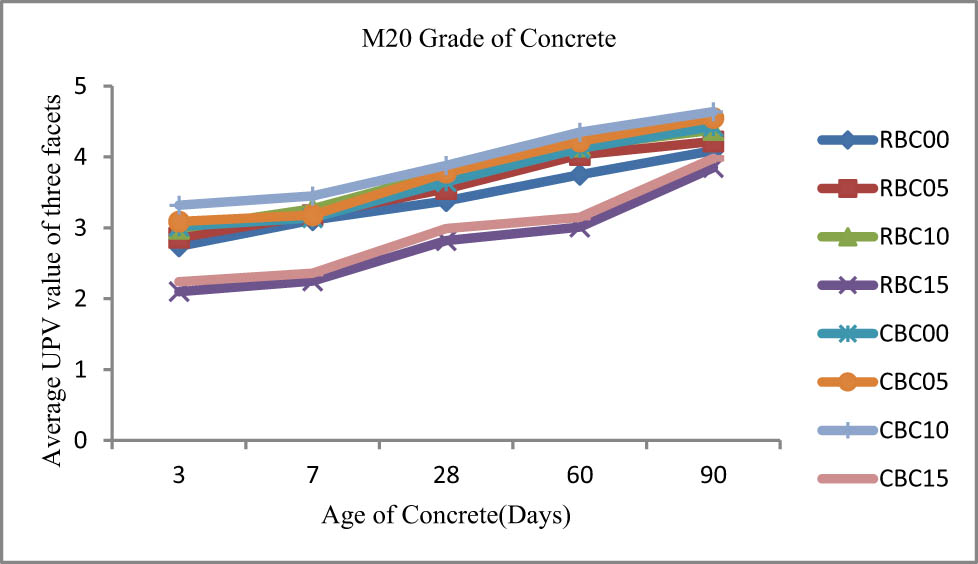

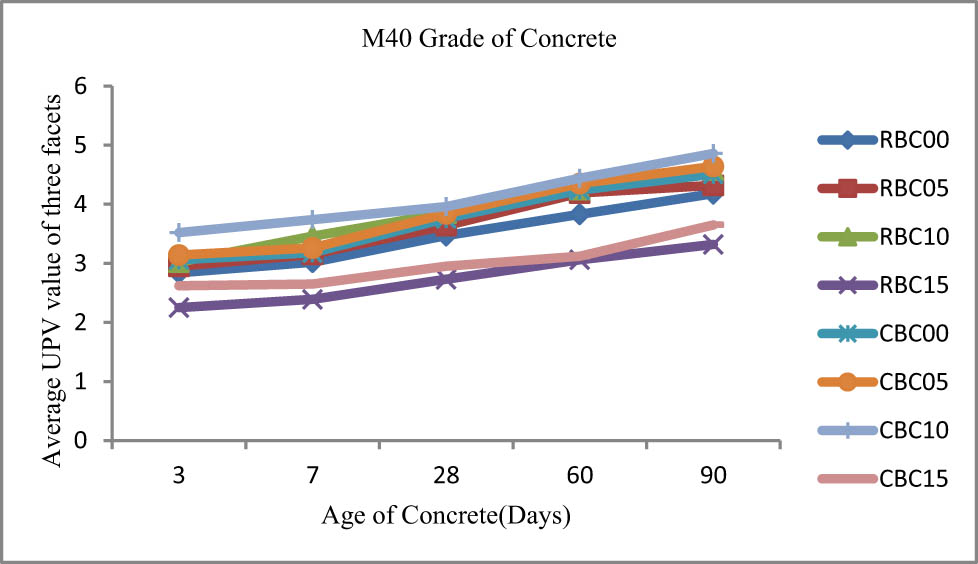

This subject covers the UPV test of many mixes with varying proportions of bacterial solution, such as 5, 10, and 15% of cement weight for concrete of M20 and M40 grade.

For river sand and crushed stone sand mixes, the experimental evolution of UPV of conventional concrete and bacterial concrete mixes with age. For all mixtures, the UPV rises as the bacterial concrete’s curing age increases. For M40 and M20-grade concrete, it was discovered that the UPV of bacterial concrete mixes was greater at 10% bacterial solution mixes.

The UPV values of typical concrete (RBC00) in river sand mixes ranged from 2.74 to 4.09 km/s with curing ages ranging from 3 to 90 days. Concrete treated with 5% bacterial solution (RBC05) showed a range of UPV values between 2.86 and 4.22 km/s. Comparably, for M20 grade concrete, the UPV values for RBC10 and RBC15 mixes ranged from 2.99 to 4.38 km/s and 2.1 to 2.85 km/s, respectively, throughout ages of 3–90 days shown in Figures 11 and 12.

Average UPV values of three facets for river sand crushed stone sand mixes.

Average UPV values of three facets for river sand crushed stone sand mixes.

The UPV values of conventional concrete (CBC00) in crushed stone sand mixes ranged from 3.02 to 4.43 km/s with curing ages ranging from 3 to 90 days. The uplift percentage (UPV) of concrete treated with 5% bacterial solution (CBC05) ranged from 3.09 to 4.55 km/s. Similarly, for ages ranging from 3 to 90 days for M20-grade concrete, the UPV values for the CBC10 and CBC15 mixes varied from 3.32 to 4.64 km/s and 2.24 to 3.98 km/s, respectively.

The UPV values of typical concrete (RBC00) in river sand mixes ranged from 2.84 to 4.18 km/s, with curing ages ranging from 3 to 90 days. Concrete treated with 5% bacterial solution (RBC05) showed a range of UPV values between 2.95 and 4.32 km/s. Similarly, for ages ranging from 3 to 90 days for M40-grade concrete, the UPV values for RBC10 and RBC15 mixes varied from 3.02 to 4.58 km/s and 2.25 to 3.32 km/s, respectively.

The UPV values of standard concrete (CBC00) in crushed stone sand mixes ranged from 3.06 to 4.51 km/s, with curing ages ranging from 3 to 90 days. The UPV values ranged from 3.14 to 4.64 km/s when concrete was treated with a 5% bacterial solution (CBC05). Similarly, for ages ranging from 3 to 90 days for M40-grade concrete, the UPV values for the CBC10 and CBC15 mixes varied from 3.52 to 4.86 km/s and 2.62 to 3.65 km/s, respectively.

The following describes the pattern of UPV fluctuation with the age of bacterial concrete, ranging from 3 to 90 days:

It has been discovered that for river sand and crushed stone sand mixtures, the UPV of bacterial concrete increases with an increase in curing age.

For all replacement levels of bacterial solution at all ages, it was discovered that the UPV of crushed stone sand mixtures was higher than that of standard concrete. From 3 to 90 days, the UPV grows more slowly; but, from 7 to 90 days, the UPV increases quickly. This is because, with bacterial solution and calcium lactate, the hydration rate is modest at first and quickens with age.

For RBC00, RBC05, RBC10, and RBC15 with river sand mixes for M20-grade concrete, the percentage increase in UPV after 90 days compared to 3 days is 49.27, 47.55, 46.48, and 83.33%.

For M20-grade concrete, the proportion of bacterial concrete in the UPV at 90 days compared to 3 days is 46.68, 47.24, 39.75, and 77.67% for CBC00, CBC05, CBC10, and CBC15, respectively, with crushed stone sand mixes.

For RBC00, RBC05, RBC10, and RBC15 with river sand mixes for M40-grade concrete, the percentage increase in UPV at 90 days compared to 3 days is 47.18, 46.44, 51.65, and 47.55%.

For bacterial concrete with crushed stone sand mixes for M40-grade concrete, the percentage increase in UPV at 90 days compared to 3 days is 47.38, 47.77, 38.06, and 39.31% for CBC00, CBC05, CBC10, and CBC15, respectively.

3.2.2 Effect of bacterial solution on quality of bacterial concrete and UPV with age

The range of UPV qualitative rating according to IS: 13311(Part 1): 1992. A speed of more than 4.5 km/s indicates high-quality concrete. The UPV value of medium-quality concrete ranges from 3.0 to 3.5 km/s, whereas that of excellent concrete is between 3.5 and 4.5 km/s. Tables 4.40 and 4.41 display the impact of bacterial solution on the caliber of bacterial concrete mixes with a curing age for all mixes.

After 3 days of curing, the quality evaluation of conventional concrete and bacterial concrete with age for river sand mixes reveals that the concrete with questionable quality. River sand mixes concrete that is medium grade after 7 days. Good-quality concrete was created after 28 days using both traditional concrete and bacterial concrete for river sand mixtures. Concrete mixtures yielded high quality after 60 days of cure. However, concrete mixes made with a 10% bacterial solution yielded exceptional quality concrete for M40-grade concrete after 90 days of curing. Concrete with medium quality was found at 3–7 days of curing, according to the quality evaluation of conventional concrete and bacterial concrete with age for crushed stone sand mixtures. Good-quality concrete mixes were generated after 28 and 60 days of curing with a 10% bacterial solution.

Nonetheless, concrete mixes made with a 10% bacterial solution after 90 days of curing yielded excellent-quality M20-grade concrete. After 3 days of curing, concrete of medium quality was determined by comparing the quality evaluation of conventional concrete and bacterial concrete with age for crushed stone sand mixtures. When 10% bacterial solution of crushed stone sand mixes is cured for 7, 28, and 60 days, high-quality concrete is produced. Nonetheless, concrete mixes made with a 10% bacterial solution after 90 days of curing yielded outstanding quality concrete suitable for M40 grade.

Nonetheless, concrete mixes made with a 10% bacterial solution after 90 days of curing yielded excellent-quality M20-grade concrete. After 3 days of curing, concrete of medium quality was determined by comparing the quality evaluation of conventional concrete and bacterial concrete with age for crushed stone sand mixtures. When 10% bacterial solution of crushed stone sand mixes is cured for 7, 28, and 60 days, high-quality concrete is produced. Nonetheless, concrete mixes made with a 10% bacterial solution after 90 days of curing yielded outstanding quality concrete suitable for M40 grade.

3.2.3 Empirical relationship between compressive strength and UPV of bacterial concrete

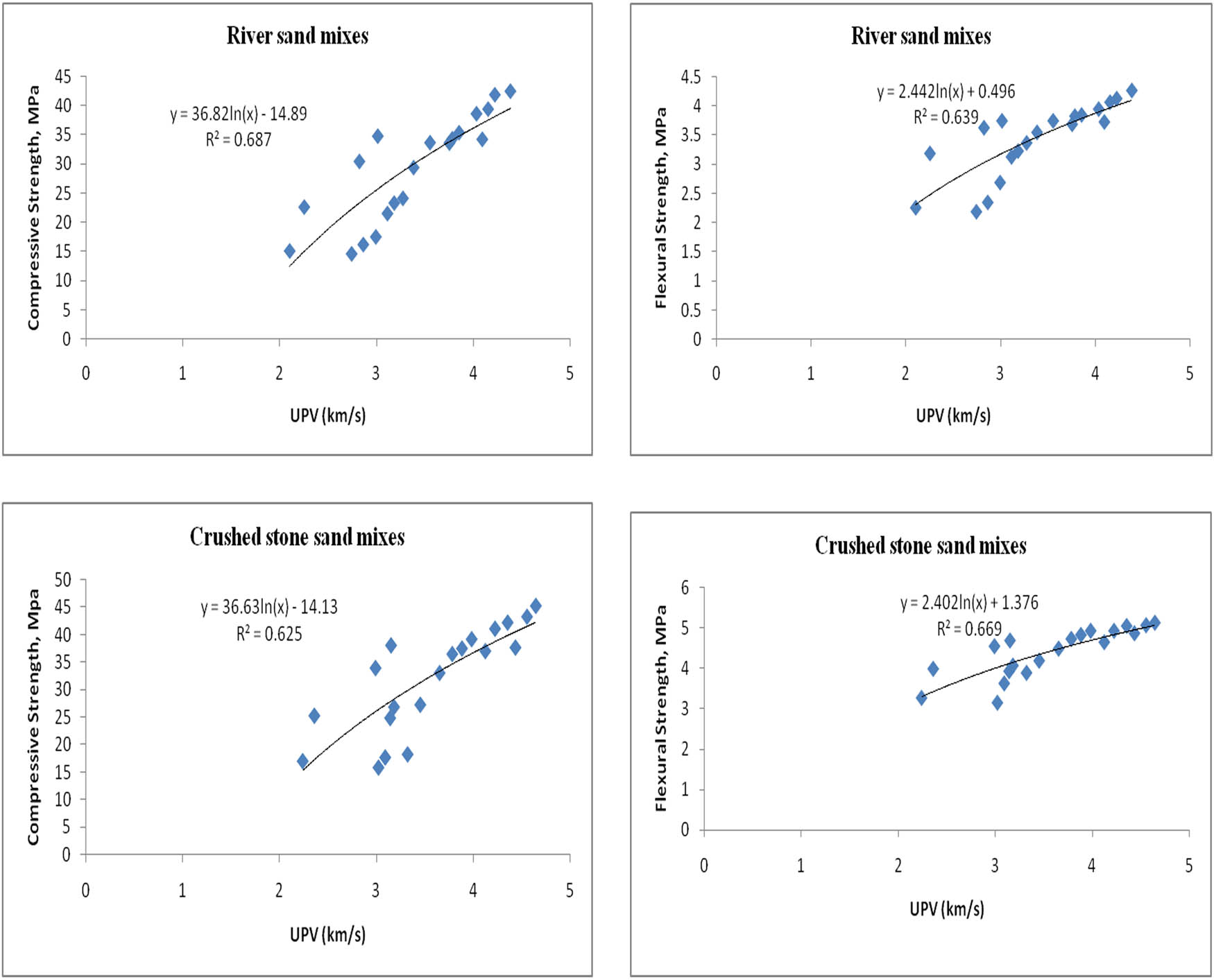

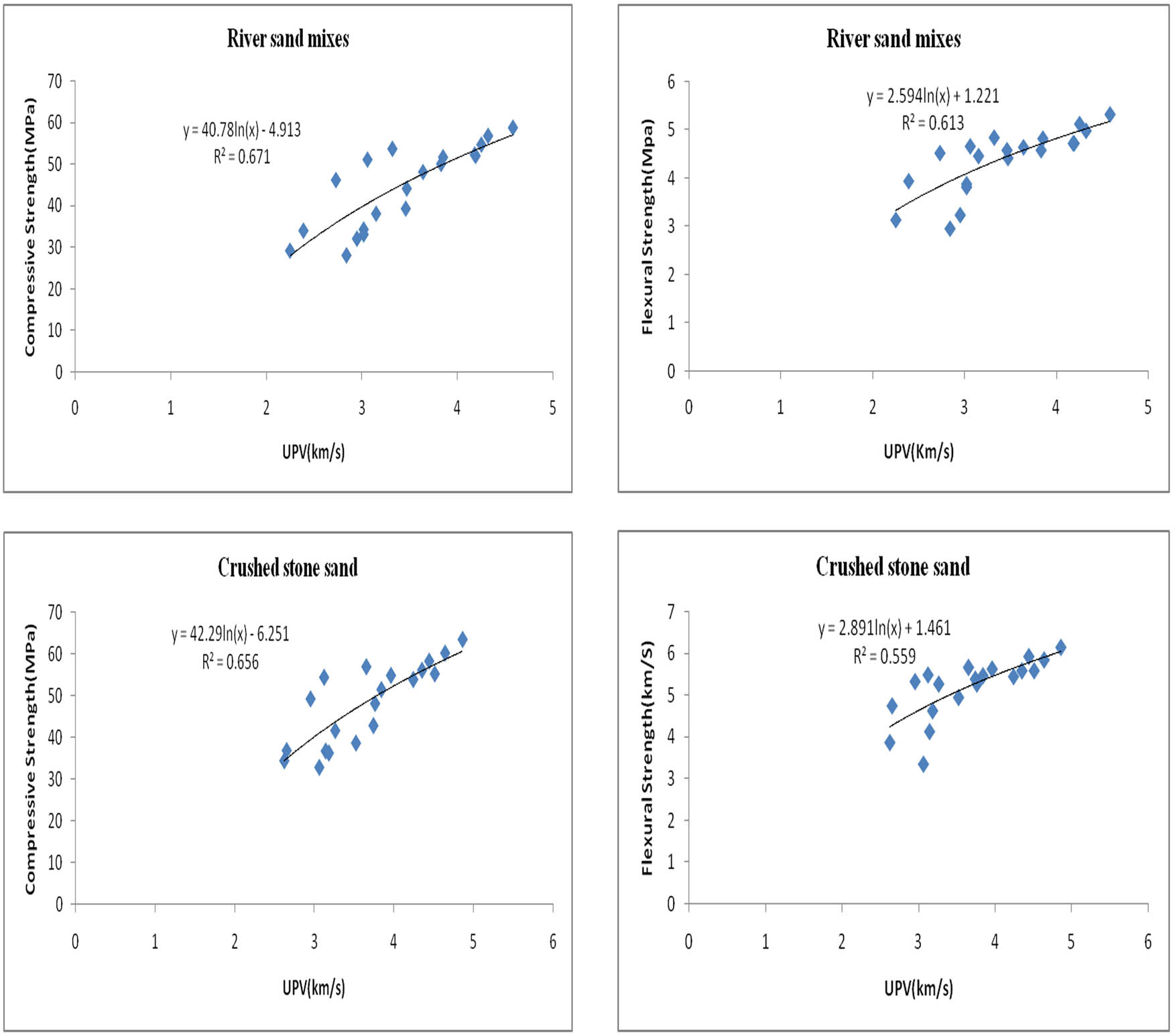

The empirical relationship between UPV and the compressive and flexural strengths of M20 and M40 bacterial concrete with crushed stone and river sand was established in this area.

From Figure 13, the following empirical relations were developed between UPV and compressive strength, flexural strength of M20 bacterial concrete with river sand and crushed stone sand.

Empirical relations between UPV and compressive strength, flexural strength for M20 grade concrete.

f c = 36.821 ln(UPV) – 14.89, R 2 = 0.687; river sand mixes.

f t = 2.43 ln(UPV) + 0.496, R 2 = 0.639; river sand mixes.

f c = 36.63 ln(UPV) – 14.13, R 2 = 0.625; crushed stone sand mixes.

f t = 2.41 ln(UPV) + 1.376, R 2 = 0.669; crushed stone sand mixes.

Figure 14 shows that the following empirical relations are developed between UPV and compressive strength, flexural strength of M40 bacterial concrete with river sand, and crushed stone sand.

Empirical relations between UPV and compressive strength, flexural strength for M40 grade concrete.

f c = 40.78 ln(UPV) – 4.913, R 2 = 0.671; river sand mixes,

f t = 2.59 ln(UPV) + 1.221, R 2 = 0.613; river sand mixes,

f c = 42.29 ln(UPV) – 6.259, R 2 = 0.656; crushed stone sand mixes,

F t = 2.891 ln(UPV) + 1.461, R 2 = 0.559; crushed stone sand mixes,where UPV is the ultrasonic pulse velocity, km/s; f c is the compressive strength of bacterial concrete with river sand mixes, MPa; f t is the flexural strength of bacterial concrete with river sand mixes, MPa.

4 Conclusion

This study focused on comparing the performance of concrete mixes containing varying percentages of bacterial solution, specifically 5, 10, and 15% of the cement weight, across M20 and M40-grade concrete. The analysis centered on Cantabro loss, a measure of abrasion resistance, revealing notable findings. Both M20 and M40-grade concrete exhibited superior abrasion resistance in comparison to river sand mixes, particularly evident when incorporating bacterial solutions of up to 10% in crushed stone sand mixes. Moreover, the dynamic modulus of elasticity was evaluated, demonstrating that crushed stone sand mixes outperformed river sand mixes, especially up to a 10% bacterial solution concentration, across both M20 and M40 grades. Notably, an empirical relationship between Cantabro loss and flexural strength was established for bacterial concrete, represented by the equation CL = −17.7 ln(f t) + 38.06, offering valuable insights into the interplay between abrasion resistance and flexural strength in concrete compositions.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank GITAM Deemed to be university for providing the necessary resources for carrying out the research work.

-

Funding information: The authors state no funding involved.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and consented to its submission to the journal, reviewed all the results and approved the final version of the manuscript. RS: problem definition, investigation, data collection, properties analysis, and interpretation of results. HP: methodology, original draft writing – review and editing.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

[1] Zhang Y, Guo HX, Cheng XH. Role of calcium sources in the strength and microstructure of microbial mortar. Constr Build Mater. 2015;77:160–7.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2014.12.040Search in Google Scholar

[2] Reddy SV, Satya AK, Rao SM, Azmatunnisa M. A biological approach to enhance strength and durability in concrete structures. Int J Adv Eng Technol. 2012;4(2):392–9.Search in Google Scholar

[3] Ramakrishnan V, Ramesh KP, Bang SS. Bacterial concrete. In Smart materials. Proceedings of the SPIE, Vol. 4234. International Society for Optics and Photonics; 2001 April. p. 168–76.Search in Google Scholar

[4] Kong L, Zhang B, Fang J. Study on the applicability of bactericides to prevent concrete microbial corrosion. Constr Build Mater. 2017;149:1–8.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2017.05.108Search in Google Scholar

[5] Gardner D, Lark R, Jefferson T, Davies R. A survey on problems encountered in current concrete construction and the potential benefits of self-healing cementitious materials. Case Stud Constr Mater. 2018;8:238–47.10.1016/j.cscm.2018.02.002Search in Google Scholar

[6] Vijay K, Murmu M, Deo SV. Bacteria based self-healing concrete–A review. Constr Build Mater. 2017;152:1008–14.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2017.07.040Search in Google Scholar

[7] Siddique R, Jameel A, Singh M, Barnat-Hunek D, Aït-Mokhtar A, Belarbi R, et al. Effect of bacteria on strength, permeation characteristics and micro-structure of silica fume concrete. Constr Build Mater. 2017;142:92–100.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2017.03.057Search in Google Scholar

[8] Wang J, Van Tittelboom K, De Belie N, Verstraete W. Use of silica gel or polyurethane immobilized bacteria for self-healing concrete. Constr Build Mater. 2012;26(1):532–40.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2011.06.054Search in Google Scholar

[9] Li VC, Herbert E. Robust self-healing concrete for sustainable infrastructure. J Adv Concr Technol 10(6):207–18.10.3151/jact.10.207Search in Google Scholar

[10] Zwaag S. Self-healing materials: an alternative approach to 20 centuries of materials science. Vol. 30. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer Science + Business Media BV; 2008. p. 15–25.10.1515/ci.2008.30.6.20Search in Google Scholar

[11] Jonkers HM, Schlangen E. Crack repair by concrete-immobilized bacteria. In Proceedings of the first international conference on self-healing materials. 2007 April. p. 18–20.Search in Google Scholar

[12] Joseph C, Jefferson AD, Cantoni MB. Issues relating to the autonomic healing of cementitious materials. In First international conference on self-healing materials. 2007. p. 1–8.Search in Google Scholar

[13] Rao SK, Sravana P, Rao TC. Investigating the effect of M-sand on abrasion resistance of fly ash roller compacted concrete (FRCC). Constr Build Mater. 2016;118:352–63.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2016.05.017Search in Google Scholar

[14] Rao SK, Sravana P, Rao TC. Experimental studies in ultrasonic pulse velocity of roller compacted concrete pavement containing fly ash and M-sand. Int J Pavement Res Technol. 2016;9(4):289–301.10.1016/j.ijprt.2016.08.003Search in Google Scholar

[15] Jonkers HM. Bacteria-based self-healing concrete. Heron. 2011;56(2):1–12.Search in Google Scholar

[16] Chidara R, Nagulagama R, Yadav S. Achievement of early compressive strength in concrete using Sporosarcina pasteurii bacteria as an admixture. Adv Civ Eng. 2014;6:110–25.10.1155/2014/435948Search in Google Scholar

[17] Palin D, Wiktor V, Jonkers H. A bacteria-based self-healing cementitious composite for application in low-temperature marine environments. Biomimetics. 2017;2(3):1–15.10.3390/biomimetics2030013Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[18] Schlangen E, Sangadji S. Addressing infrastructure durability and sustainability by self healing mechanisms-Recent advances in self healing concrete and asphalt. Procedia Eng. 2013;54:39–57.10.1016/j.proeng.2013.03.005Search in Google Scholar

[19] Abo-El-Enein SA, Ali AH, Talkhan FN, Abdel-Gawwad HA. Application of microbial biocementation to improve the physico-mechanical properties of cement mortar. HBRC J. 2013;9(1):36–40.10.1016/j.hbrcj.2012.10.004Search in Google Scholar

[20] Gupta S, Dai Pang S, Kua HW. Autonomous healing in concrete by bio-based healing agents–A review. Constr Build Mater. 2017;146:419–28.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2017.04.111Search in Google Scholar

[21] Tziviloglou E, Wiktor V, Jonkers HM, Schlangen E. Bacteria-based self-healing concrete to increase liquid tightness of cracks. Constr Build Mater. 2016;122:118–25.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2016.06.080Search in Google Scholar

[22] Nou MRG, Moghaddam MA, Bajestan MS, Azamathulla HM. Control of bed scour downstream of ski-jump spillway by combination of six-legged concrete elements and riprap. Ain Shams Eng J. 2020;11(4):1047–59.10.1016/j.asej.2020.01.009Search in Google Scholar

[23] Leon LP, Roopnarine K, Azamathulla HM, Chadee AA, Rathnayake U. A perrformance-based design framework for enhanced asphalt concrete in the caribbean region. Buildings. 2023;13(7);1661.10.3390/buildings13071661Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Probing microstructural evolution and surface hardening of AISI D3 steel after multistage heat treatment: An experimental and numerical analysis

- Activation energy of lime cement containing pozzolanic materials

- Optimizing surface quality in PMEDM using SiC powder material by combined solution response surface methodology – Adaptive neuro fuzzy inference system

- Experimental study of the mechanical shear behaviour of steel rebar connectors in timber–concrete structure with leafy wood species

- Development of structural grade lightweight geopolymer concrete using eco-friendly materials

- An experimental approach for the determination of the physical and mechanical properties of a sustainable geopolymer mortar made with Algerian ground-granulated blast furnace slag

- Effect of using different backing plate materials in autogenous TIG welding on bead geometry, microhardness, tensile strength, and fracture of 1020 low carbon steel

- Uncertainty analysis of bending response of flexoelectric nanocomposite plate

- Leveraging normal distribution and fuzzy S-function approaches for solar cell electrical characteristic optimization

- Effect of medium-density fiberboard sawdust content on the dynamic and mechanical properties of epoxy-based composite

- Mechanical properties of high-strength cement mortar including silica fume and reinforced with single and hybrid fibers

- Study the effective factors on the industrial hardfacing for low carbon steel based on Taguchi method

- Analysis of the combined effects of preheating and welding wire feed rates on the FCAW bead geometric characteristics of 1020 steel using fuzzy logic-based prediction models

- Effect of partially replacing crushed oyster shell as fine aggregate on the shear behavior of short RC beams using GFRP rebar strengthened with TRC: Experimental and numerical studies

- Micromechanic models for manufacturing quality prediction of cantula fiber-reinforced nHA/magnesium/shellac as biomaterial composites

- Numerical simulations of the influence of thermal cycling parameters on the mechanical response of SAC305 interconnects

- Impact of nanoparticles on the performance of metakaolin-based geopolymer composites

- Enhancing mechanical and thermal properties of epoxy-based polymer matrix composites through hybrid reinforcement with carbon, glass and steel

- Prevention of crack kinetic development in a damaged rod exposed to an aggressive environment

- Ideal strain gauge location for evaluating stress intensity factor in edge-cracked aluminum plates

- Experimental and multiscale numerical analysis of elastic mechanical properties and failure in woven fabric E-glass/polyester composites

- Optimizing piezoelectric patch placement for active repair of center-cracked plates

- Experimental investigation on the transverse crushing performance of 3D printed polymer composite filled aluminium tubes

- Review Articles

- Advancing asphaltic rail tracks: Bridging knowledge gaps and challenges for sustainable railway infrastructure

- Chemical stabilization techniques for clay soil: A comprehensive review

- Development and current milestone of train braking system based on failure phenomenon and accident case

- Rapid Communication

- The role of turbulence in bottom-up nanoparticle synthesis using ultrafast laser filamentation in ethanol

- Special Issue on Deformation and Fracture of Advanced High Temperature Materials - Part II

- Effect of parameters on thermal stress in transpiration cooling of leading-edge with layered gradient

- Development of a piezo actuator-based fatigue testing machine for miniature specimens and validation of size effects on fatigue properties

- Development of a 1,000°C class creep testing machine for ultraminiature specimens and feasibility verification

- Special Issue on Advances in Processing, Characterization and Sustainability of Modern Materials - Part II

- Surface integrity studies in microhole drilling of Titanium Beta-C alloy using microEDM

- Experimental investigation on bacterial concrete by using Cantabro loss and UPV

- Influence of gas nitriding on the surface layer of M50 NiL steel for aerospace-bearing applications

- Experimental investigation on the spectral, mechanical, and thermal behaviors of thermoplastic starch and de-laminated talc-filled sustainable bio-nanocomposite of polypropylene

- Synthesis and characterization of sustainable hybrid bio-nanocomposite of starch and polypropylene for electrical engineering applications

- Microstructural and mechanical characterization of Al6061-ZrB2 nanocomposites fabricated by powder metallurgy

- Effect of edge preparation on hardness and corrosion behaviour of AA6061-T651 friction stir welds

- Mechanical improvement in acetal composites reinforced with graphene nanotubes and Teflon fibers using loss functions

- Experimental investigation on the mechanical properties of aluminum-based metal matrix composites by the squeeze casting method

- Investigation on punch force–displacement and thickness changes in the shallow drawing of AA2014 aluminium alloy sheets using finite element simulations

- Influence of liquid nitriding on the surface layer of M50 NiL steel for bearing applications

- Mechanical and tribological analyses of Al6061-GO/CNT hybrid nanocomposites by combined vacuum-assisted and ultrasonicated stir casting method

- Strengthening of structures with bacterial concrete for effective crack repair and durability enhancement

- Unique approaches in developing novel nano-composites: Evaluating their mechanical and tribological characteristics

- Load-carrying capacity of highly compact rigid deployable booms

- Investigating the influence of SiC and B4C reinforcements on the mechanical and microstructural properties of stir-casted magnesium hybrid composites

- Evaluation of mechanical and performance characteristics of bitumen mixture using waste septage ash as partial substitute

- Mechanical characterization of carbon/Kevlar hybrid woven 3D composites

- Development of a 3D-printed cervical collar using biocompatible and sustainable polylactic acid

- Mechanical characterization of walnut shell powder-reinforced neem shell liquid composite

- Special Issue on Structure-energy Collaboration towards Sustainability Societies

- Effect of tunneling conductivity of CNTs on the EMI shielding effectiveness of nanocomposite in the C-band

- Evaluation of the effect of material selection and core geometry in thin-walled sandwich structures due to compressive strength using a finite element method

- Special Issue on Sustainability and Development in Civil Engineering - Part III

- The optimum reinforcement length for ring footing resting on sandy soils resisting inclined load

- Special Issue on Advanced Materials in Industry 4.0

- Cross-dataset evaluation of deep learning models for crack classification in structural surfaces

- Mechanical and antibacterial characteristics of a 3D-printed nano-titanium dioxide–hydroxyapatite dental resin-based composite

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Probing microstructural evolution and surface hardening of AISI D3 steel after multistage heat treatment: An experimental and numerical analysis

- Activation energy of lime cement containing pozzolanic materials

- Optimizing surface quality in PMEDM using SiC powder material by combined solution response surface methodology – Adaptive neuro fuzzy inference system

- Experimental study of the mechanical shear behaviour of steel rebar connectors in timber–concrete structure with leafy wood species

- Development of structural grade lightweight geopolymer concrete using eco-friendly materials

- An experimental approach for the determination of the physical and mechanical properties of a sustainable geopolymer mortar made with Algerian ground-granulated blast furnace slag

- Effect of using different backing plate materials in autogenous TIG welding on bead geometry, microhardness, tensile strength, and fracture of 1020 low carbon steel

- Uncertainty analysis of bending response of flexoelectric nanocomposite plate

- Leveraging normal distribution and fuzzy S-function approaches for solar cell electrical characteristic optimization

- Effect of medium-density fiberboard sawdust content on the dynamic and mechanical properties of epoxy-based composite

- Mechanical properties of high-strength cement mortar including silica fume and reinforced with single and hybrid fibers

- Study the effective factors on the industrial hardfacing for low carbon steel based on Taguchi method

- Analysis of the combined effects of preheating and welding wire feed rates on the FCAW bead geometric characteristics of 1020 steel using fuzzy logic-based prediction models

- Effect of partially replacing crushed oyster shell as fine aggregate on the shear behavior of short RC beams using GFRP rebar strengthened with TRC: Experimental and numerical studies

- Micromechanic models for manufacturing quality prediction of cantula fiber-reinforced nHA/magnesium/shellac as biomaterial composites

- Numerical simulations of the influence of thermal cycling parameters on the mechanical response of SAC305 interconnects

- Impact of nanoparticles on the performance of metakaolin-based geopolymer composites

- Enhancing mechanical and thermal properties of epoxy-based polymer matrix composites through hybrid reinforcement with carbon, glass and steel

- Prevention of crack kinetic development in a damaged rod exposed to an aggressive environment

- Ideal strain gauge location for evaluating stress intensity factor in edge-cracked aluminum plates

- Experimental and multiscale numerical analysis of elastic mechanical properties and failure in woven fabric E-glass/polyester composites

- Optimizing piezoelectric patch placement for active repair of center-cracked plates

- Experimental investigation on the transverse crushing performance of 3D printed polymer composite filled aluminium tubes

- Review Articles

- Advancing asphaltic rail tracks: Bridging knowledge gaps and challenges for sustainable railway infrastructure

- Chemical stabilization techniques for clay soil: A comprehensive review

- Development and current milestone of train braking system based on failure phenomenon and accident case

- Rapid Communication

- The role of turbulence in bottom-up nanoparticle synthesis using ultrafast laser filamentation in ethanol

- Special Issue on Deformation and Fracture of Advanced High Temperature Materials - Part II

- Effect of parameters on thermal stress in transpiration cooling of leading-edge with layered gradient

- Development of a piezo actuator-based fatigue testing machine for miniature specimens and validation of size effects on fatigue properties

- Development of a 1,000°C class creep testing machine for ultraminiature specimens and feasibility verification

- Special Issue on Advances in Processing, Characterization and Sustainability of Modern Materials - Part II

- Surface integrity studies in microhole drilling of Titanium Beta-C alloy using microEDM

- Experimental investigation on bacterial concrete by using Cantabro loss and UPV

- Influence of gas nitriding on the surface layer of M50 NiL steel for aerospace-bearing applications

- Experimental investigation on the spectral, mechanical, and thermal behaviors of thermoplastic starch and de-laminated talc-filled sustainable bio-nanocomposite of polypropylene

- Synthesis and characterization of sustainable hybrid bio-nanocomposite of starch and polypropylene for electrical engineering applications

- Microstructural and mechanical characterization of Al6061-ZrB2 nanocomposites fabricated by powder metallurgy

- Effect of edge preparation on hardness and corrosion behaviour of AA6061-T651 friction stir welds

- Mechanical improvement in acetal composites reinforced with graphene nanotubes and Teflon fibers using loss functions

- Experimental investigation on the mechanical properties of aluminum-based metal matrix composites by the squeeze casting method

- Investigation on punch force–displacement and thickness changes in the shallow drawing of AA2014 aluminium alloy sheets using finite element simulations

- Influence of liquid nitriding on the surface layer of M50 NiL steel for bearing applications

- Mechanical and tribological analyses of Al6061-GO/CNT hybrid nanocomposites by combined vacuum-assisted and ultrasonicated stir casting method

- Strengthening of structures with bacterial concrete for effective crack repair and durability enhancement

- Unique approaches in developing novel nano-composites: Evaluating their mechanical and tribological characteristics

- Load-carrying capacity of highly compact rigid deployable booms

- Investigating the influence of SiC and B4C reinforcements on the mechanical and microstructural properties of stir-casted magnesium hybrid composites

- Evaluation of mechanical and performance characteristics of bitumen mixture using waste septage ash as partial substitute

- Mechanical characterization of carbon/Kevlar hybrid woven 3D composites

- Development of a 3D-printed cervical collar using biocompatible and sustainable polylactic acid

- Mechanical characterization of walnut shell powder-reinforced neem shell liquid composite

- Special Issue on Structure-energy Collaboration towards Sustainability Societies

- Effect of tunneling conductivity of CNTs on the EMI shielding effectiveness of nanocomposite in the C-band

- Evaluation of the effect of material selection and core geometry in thin-walled sandwich structures due to compressive strength using a finite element method

- Special Issue on Sustainability and Development in Civil Engineering - Part III

- The optimum reinforcement length for ring footing resting on sandy soils resisting inclined load

- Special Issue on Advanced Materials in Industry 4.0

- Cross-dataset evaluation of deep learning models for crack classification in structural surfaces

- Mechanical and antibacterial characteristics of a 3D-printed nano-titanium dioxide–hydroxyapatite dental resin-based composite