Mechanical properties of laminated bamboo composite as a sustainable green material for fishing vessel: Correlation of layer configuration in various mechanical tests

Abstract

With the increased emphasis on the need to use recyclable bio-based materials and a better understanding of the mechanical properties of laminated bamboo, there is currently a great deal of interest in developing a new generation of low-cost bamboo-based composites for use in fishing vessels. Laminated bamboo composites (LBCs) comprised of Apus bamboo (Gigantochloa apus) and fibreglass mats were investigated to obtain the mechanical characteristics. The LBC with 45°/−45° cross-fibre directions combined with chopped strand mat fibreglass was developed under different layers and mass fractions with the same composite thickness. The influence of different numbers of laminated bamboo layers (3–7 layers) on several mechanical testings, including impact tests using ASTM D256, bending tests using ASTM D7264, tensile tests using ASTM D3039, V-notched beam test using ASTM D7078, and lap shear tests using ASTM D5868 standard, were carried out. The result showed that the strategy in improving the strength properties of LBCs could be achieved by using a thinner bamboo lamina with a higher number of bamboo layers. It was found that bamboo composites with 7 layers with a higher epoxy mass matrix had superior mechanical properties than those with 3 and 5 layers at the same thickness. Another finding revealed that adding fibreglass mat to current LBCs improved mechanical properties compared to previous research, explicitly bending strength increased by about 4.02–7.56% and tensile strength in the range of 12.44–17.73%. It can be found that only specimen with 7 layers fulfils the Indonesian Bureau Classification’s bending and tensile strength threshold.

1 Introduction

Indonesia is a tropical country with several bamboo plant species. More than 1,250 bamboo species are found throughout the world, with approximately 11% of those species being cultivated in Indonesia. Bamboo is commonly used for flooring, roofing, crafts/furniture, and textiles. Over time, Apus bamboo (Gigantochloa apus) has spread across Indonesia, becoming the dominating plant, particularly in rural locations. Apus bamboo grows in clusters of 10–25 trees. Apus bamboo is a variety of bamboo that is simple to divide and cut up to a thickness of 1 mm, and it is extensively utilised in manufacturing handicraft items [1]. Bamboo belongs to the grass family and has a growth rate that is significantly higher than wood, with many bamboo species reaching full height in less than 6 months and maturity in 3–5 years. The mechanical properties of bamboo depend on the species and can also be influenced by local climatic conditions [2].

The benefits of bamboo’s mechanical characteristics and the availability of numerous resources have encouraged many researchers to employ bamboo as reinforcement in composite materials. There are several advantages to using bamboo fibres as a reinforcing material. Compared to manufactured fibres such as glass or carbon fibres, natural fibres with high availability and renewability can be a valuable lightweight engineering material with attractive physicomechanical properties [3,4]. The tensile strength of bamboo is roughly twice that of timber, with the compressive strength being around 1.5 times that of timber. Bamboo has a more excellent strength-to-weight ratio than timber and plain steel [5]. Although bamboo has been known to have superior mechanical properties compared to wood, further development of bamboo-based ship structures did not progress because of concerns over the availability of bamboo and a push to utilise polymeric-based fibreglass composites.

The prototype of a ship made of bamboo as a core material is presented as an alternative to wooden boats, which are becoming increasingly scarce nowadays. One of the promising techniques in bamboo engineering is the development of laminated bamboo composites (LBCs) [6,7]. Laminated bamboo is a bamboo-based composite that is produced by bonding bamboo strips/laminas under regulated temperature or pressure. Using bamboo fibres as polymer reinforcing materials offer several advantages, including lower material prices, greater strength and durability, and environmental friendliness [8]. Therefore, the development of composites using a combination of the bamboo lamina and fibreglass mat as a ship material will be developed in this study. The laminated bamboo and fibreglass mat layers under different number of layer and lamina directions are studied to compare the material characteristics. The influence of the bamboo lamina configurations under different mechanical tests, including tensile, bending, impact, V-notched beam, and lap shear tests, is investigated.

2 Development of LBCs

The demand for wood components in the traditional shipbuilding sector in Indonesia is growing, even as the supply of wood is depleting due to widespread illegal logging. Wooden material regeneration takes a long time, and the price of wood may be high. Thus, wood alternatives are required. Specifically, the need for wood for fishing vessel accounts for 10–15% of overall wood demand in Indonesia, which is more than 2.5 million m3/year. However, it is impossible to determine the precise amount of timber used [9]. Indonesia lost 8.4% (15 million hectares) of its forest, ranking the highest globally [10]. Based on this situation, Indonesia has been experiencing a scarcity of wood as a building material for ship since 2010 [11]. Some traditional shipyards have switched to employing fibreglass materials to continue producing fishing boats. Nonetheless, most Indonesian fishermen have not entirely embraced using fibreglass materials.

In a recent development, using LBCs has encouraged experts and researchers to exploit these materials in invariant applications such as aerospace, defence [12], and marine hull [13,14]. Notably, an early study on laminated bamboo slats as a substitute for wood in the building of wooden boat frames, beams, and keels was investigated. According to the research findings, bamboo vessels have more strength, greater security, and costs up to 50% lower than wooden vessels [15]. Compared to teak wood, using laminated bamboo in vessel construction can lower vessel skin thickness by 27% on 30 GT fishing boats. It demonstrates that laminated bamboo has a high level of strength and elasticity. The production process is also simpler and more adaptable because there is no set size, but it adapts to shipbuilding demands. The bamboo used in construction has the benefit of being exposed to water, particularly salt water because bamboo fibres are considered stronger when exposed to salt water [16].

Several investigations have been conducted to determine the physical and mechanical characteristics. Rassiah et al. created hand lay-up composites with 2–6 bamboo layers utilizing unsaturated polyester (UP) as the matrix. According to the findings, increasing the thickness of the bamboo strips improves the tensile strength and modulus of the laminated bamboo/polyester. This is due to the enhanced physical contact of the bamboo with an UP matrix [17]. Moreover, the combination of Apus bamboo and Meranti wood as an alternative material for the traditional ship was investigated in both technical and economic aspects [18]. The result shows that the combination materials can be used as a construction material on wooden ships. The influence of the arrangement and size of Betung bamboo split fibres on the matrix interface bond of laminated bamboo split fibres is examined in [19]. The glue interface influences the interface bond strength of laminated bamboo because the larger the split, the more glue is required and the greater the bond interface strength. Comprehensive development in the recent decades in the experimental testing of LBCs is presented in Table 1.

Research landmark on the experimental testing development of LBCs

| Milestone | Author(s) | Material selection | Notable remarks |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2012 | Verma and Chariar [5] | Green bamboo – epoxy resin adhesive material |

|

| 2014 | Rassiah et al. [17] | Buluh semantan bamboo – UP |

|

|

|||

|

|||

| 2015 | Supomo et al. [11] | Ori bamboo – polyamide epoxy adhesive material |

|

|

|||

| 2018 | Supomo et al. [15] | Betung laminated bamboo – four adhesive layer types |

|

|

|||

|

|||

| 2018 | Manik et al. [18] | Apus bamboo-Meranti wood – epoxy resin adhesive material |

|

| 2019 | Manik et al. [7] | Apus and Betung bamboo – epoxy resin adhesive material |

|

| 2019 | Amatosa et al. [16] | Dragon bamboo – epoxy resin adhesive material |

|

|

|||

| 2020 | Rindo et al. [19] | Betung bamboo – polyvinyl acetate adhesive material |

|

| 2021 | Manik et al. [8] | Apus bamboo – epoxy resin adhesive material |

|

| 2021 | Manik et al. [1] | Apus bamboo – epoxy resin adhesive material |

|

|

Regarding the investigation of Apus bamboo, the influence of water salinity on changes in the physical and mechanical characteristics of laminated Apus bamboo composites was explored, assuming that ships are operated at sea. The test findings show that as the immersion length in seawater rises, the material strength decreases [8]. In a further study, the parameters of lamina thickness, number of laminas, orientations, and compacting pressures of LBCs were then investigated by Manik et al. [1]. The results show that a bamboo composite with a lower lamina thickness and a higher number of lamina layers has the highest tensile and bending strength. However, only specimens with 0 and 0°/90° layer orientations fulfil the Indonesian Bureau Classification (BKI) standard. The specimen with 45°/−45° layer orientation has mechanical strength below the acceptance criterion. As a result, it is critical to investigate further the development of LBCs for ship structures based on BKI standards.

Furthermore, based on the past research, it can be inferred that producing LBCs under the BKI standard is crucial in improving the use of bamboo as a green material for the traditional fishing vessel in Indonesia. Based on the review, bamboo types, the number of laminas, material configurations, and adhesive types are critical parameters for achieving a high strength of LBCs. Besides, combining LBCs with other material combinations to achieve better mechanical strength is interesting to be studied. For further investigation, incorporating fibreglass mat layer into LBCs established earlier by Manik et al. [1] needs to be analysed using a similar specimen arrangement and testing approach. This study is crucial for increasing the mechanical properties of LBCs to achieve the minimum threshold given by the BKI standard. In this case, adding a fibreglass mat layer to the mechanical behaviour and characteristics of LBCs with 45°/−45° layer orientation will be examined by employing a variety of layer numbers and mass fractions. Several mechanical tests will be employed to conduct a comparative analysis of mechanical behaviour due to the addition of fibreglass mat layer under three layer configurations with different mass fractions.

3 Material and methods

3.1 Material selections and characteristics

3.1.1 Apus bamboo (Gigantochloa apus)

Bamboo is a grass-root plant that grows significantly in Indonesia. Most of the bamboo plants are in rural areas. As a tropical natural resource, there are many variations in bamboo, easy to obtain, fast-growing, and used in people’s daily lives as a sustainable source [20,21]. In Southeast Asia, bamboo is used as a building material and for making various vegetable baskets. Other usages include papermaking, musical instruments, handicrafts, and boat/shipbuilding. [20]. Apus bamboo is used as a structural material to replace wood on the fishing vessel in this case. This type of bamboo is very abundant in terms of availability [22]. Apus bamboo has a sympodial clump, tight and upright, and has a diameter of 4–15 cm according to soil fertility, and can grow up to 22 m. It usually thrives on river banks and hilly slopes from lowlands to highlands (±1,300 m asl).

Bamboo lamina of Gigantochloa apus was used as the primary reinforcement material. Bamboo was collected and harvested from natural forests in the Getasan area, Salatiga Regency, Central Java, Indonesia. The bamboo used was 3 years old with an average diameter of 150 mm. The selected part of the bamboo stem, 1 m from the base to 4 m, was used to make the lamina. Previous research stated the mechanical properties of Apus bamboo: air content 12–15%, a specific gravity value of 0.59 g/cm3, a bending strength of 502.3–1240.3 kgf/cm2, a modulus of elasticity (MOE) of 57.515–121.334 kgf/cm2, and a tensile strength of 1,231–2,859 kgf/cm2 [18]. Apus bamboo lamina-making process is illustrated in detail in Figure 1.

Bamboo lamina-making process.

3.1.2 Fibreglass chopped strand mat (CSM)

CSM, also known as fibreglass mat, comprises short fibre strands held together by a resin binder. It is inexpensive and frequently used in moulding construction and parts requiring thickness. CSM easily conforms to tight curves and corners. The random orientation of the fibres provides equal stiffness in all directions. This material is relatively lighter than wood (72% compared to wood), more straightforward, non-corrosive, and easy to maintain. In this case, the selection of this material is intended to increase the mechanical strength of laminated bamboo without increasing the density excessively. CSM is a non-woven mat composed of glass filaments that consist of chopped fibres that are randomly and equally oriented. The randomly distributed fibres have an average diameter of approximately 13–15 μm, around 5 cm in length, and an area density of 450 g/m2. The specification of CSM fibre is presented in Table 2. The CSM fibres were covered with a silane coupling agent and kept together with an emulsion binder. The type used was a fibreglass CSM collected from Justus Kimiaraya, Semarang, Indonesia. CSM fibres are especially well-suited for hand lay-up processes employing Thermoset resin systems to produce a wide range of ship materials.

CSM fibre specifications [23]

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Fibre diameter (μm) | 10–20 |

| Fibre length (mm) | 25–50 |

| Tensile modulus (GPa) | 71 |

| Aspect ratio | 2,500 |

3.1.3 Epoxy adhesive material

Epoxy Resin glue, which is extensively used in repairing wooden ships and constructing fibreglass boats, is the adhesive ingredient used in the bamboo lamination process. Epoxy Resin Adhesives are composed of two components: epoxy resin and hardener. Thermosetting epoxy resin is a form of glue. This epoxy comprises two parts: epoxy resin and hardener, which are combined in a 50/50 ratio, as suggested in [18]. The epoxy Bakelite® EPR 174 and resin hardener V-140 from Justus Kimiaraya, Semarang, Indonesia, were used as a matrix and hardener. Tables 3 and 4 show the composition and mechanical properties of epoxy resin, respectively.

The chemical composition of epoxy resin [18]

| No. | Compositions | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bisphenol A | 80–90 |

| 2 | Modified epoxy resin | 5–15 |

| 3 | Alkyl glycidyl ether | 5–15 |

| 4 | Mercapton polymer | 50–60 |

| 5 | Tertiary amine | 5–10 |

| 6 | Polyamide resin | 30–35 |

| 7 | Triethylene tetramine | <3 |

| 9 | Aliphatic amine | 1–10 |

The mechanical properties of epoxy resin [24]

| Mechanical characteristics | Value |

|---|---|

| Ultimate tensile strength | 22.13 MPa |

| Density | 1065.0 kg/m3 |

| Tensile modulus | 656.7 MPa |

| Elongation at break | 0.0337 |

3.2 Material manufacture and testing

3.2.1 Steps of manufacturing laminated bamboo boards

The initial step in manufacturing laminated boards was to make bamboo strips of Apus bamboo, with various blade widths and thicknesses, namely, 1, 1.5, and 2 mm. Bamboo stalks were chopped at the height of 1 m above the ground. The portion of the stem used for the study was located 1–4.5 m above the ground. The bamboo was cut crosswise (cross-cutting) according to the length of the section (40 cm). After splitting the bamboo stalks into blades, the outer shell was removed to create bamboo slats. The splitting method was then carried out to generate a 40 cm × 20 mm bamboo blade. The 4-sided planning tool was used to produce the bamboo lamina blades to achieve thicknesses of 1, 1.5, and 2 mm. The bamboo laminas were then maintained by soaking them with a preservative solution containing 2.5% sodium tetraborate. The bamboo laminas were dried after preservation in an oven until the water content reached 10%. The percentage of water content in the bamboo laminas was determined using a moisture meter. Depending on the weather, drying in an oven takes 4–6 h until the moisture content of the material becomes less than 13%. Dry bamboo slats were grouped by thickness and sanded to smooth the surface with a sandpaper machine. The dried bamboo laminas were then utilised to manufacture LBCs as reinforcing composites.

As a matrix/adhesive substance, an epoxy resin polymer was employed. Hand lay-up techniques were made with 3 different numbers of bamboo laminas: 3, 5, and 7, with the fibres running parallel to each other (45°/−45°). For the initial layer, epoxy glue was used to smooth the whole surface of the bamboo uniformly. For the second layer, the entire fibreglass mat was covered with epoxy resin. The bamboo slats and fibreglass mats that have been cut and formed into boards were aligned based on the size and arrangement of the laminated bamboo slats’ fibres. A cold press machine was used for pressing at a pressure of 2 MPa, or the equivalent of 30 bar. When the press pressure had reached the desired level, the bolts on the mould’s iron clamp were tightened. Laminated bamboo planks that had been crushed were placed in the clamp for 24 h before being removed to enhance the adhesion between the layers. Figure 2 shows the comparison of 40 cm × 20 cm sized LBC for different numbers of layers, and the formation of the bamboo lamina is presented in Figure 3.

Laminated bamboo – fibreglass boards: (a) 3 layers, (b) 5 layers, and (c) 7 layers.

![Figure 3

(a) Laminae shape of the Apus bamboo and (b) LBC making process [1].](/document/doi/10.1515/jmbm-2022-0075/asset/graphic/j_jmbm-2022-0075_fig_003.jpg)

(a) Laminae shape of the Apus bamboo and (b) LBC making process [1].

The layer configuration and mass fraction of LBCs are presented in Table 5. The composites had the same thickness with different numbers of bamboo and fibreglass layers. LBCs with 7 layers had a larger mass fraction of epoxy resin matrix than 5 layers and 3 layers bamboo composites. Mass fraction of specimen with 3 layers comprised of 25 wt% epoxy resin and 75% bamboo lamina. Specimen with 5 layers had 30 wt% epoxy resin and 70 wt% bamboo lamina, and specimens with 7 layers had 35 wt% epoxy resin and 65 wt% bamboo lamina. The mass fraction of a substance (percentage by weight/wt%) within a mixture is the ratio of the mass of that substance (m i ) to the total mass of the mixture (m tot). It was found that the number of layers will increase the mass fraction of the epoxy resin matrix. Apus bamboo fibre had a density of 0.60 g/cm3 in dry conditions, while the epoxy resin had a density of 1.27 g/cm3. LBCs with the highest layers were formed from bamboo fibres with a thinner thickness (1 mm).

Layer configuration of LBC

| Layer configurations | Composite lamina thickness (mm) | Bamboo layer and orientation | CSM layer and orientation | Mass fraction (wt%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

10 | 3 layers (45°/−45°/45°) orientation | 2 (random) | 25% epoxy resin |

| 2 mm thickness | 75% bamboo lamina | |||

|

10 | 5 layers (45°/−45°/45°/−45°/45°) orientation | 4 (random) | 30% epoxy resin |

| 1.5 mm thickness | 70% bamboo lamina | |||

|

10 | 7 layers 45°/−45°/45°/−45°/45°/−45°/45° orientation | 6 (random) | 35% epoxy resin |

| 1 mm thickness | 65% bamboo lamina |

3.2.2 The testing procedure of LBC

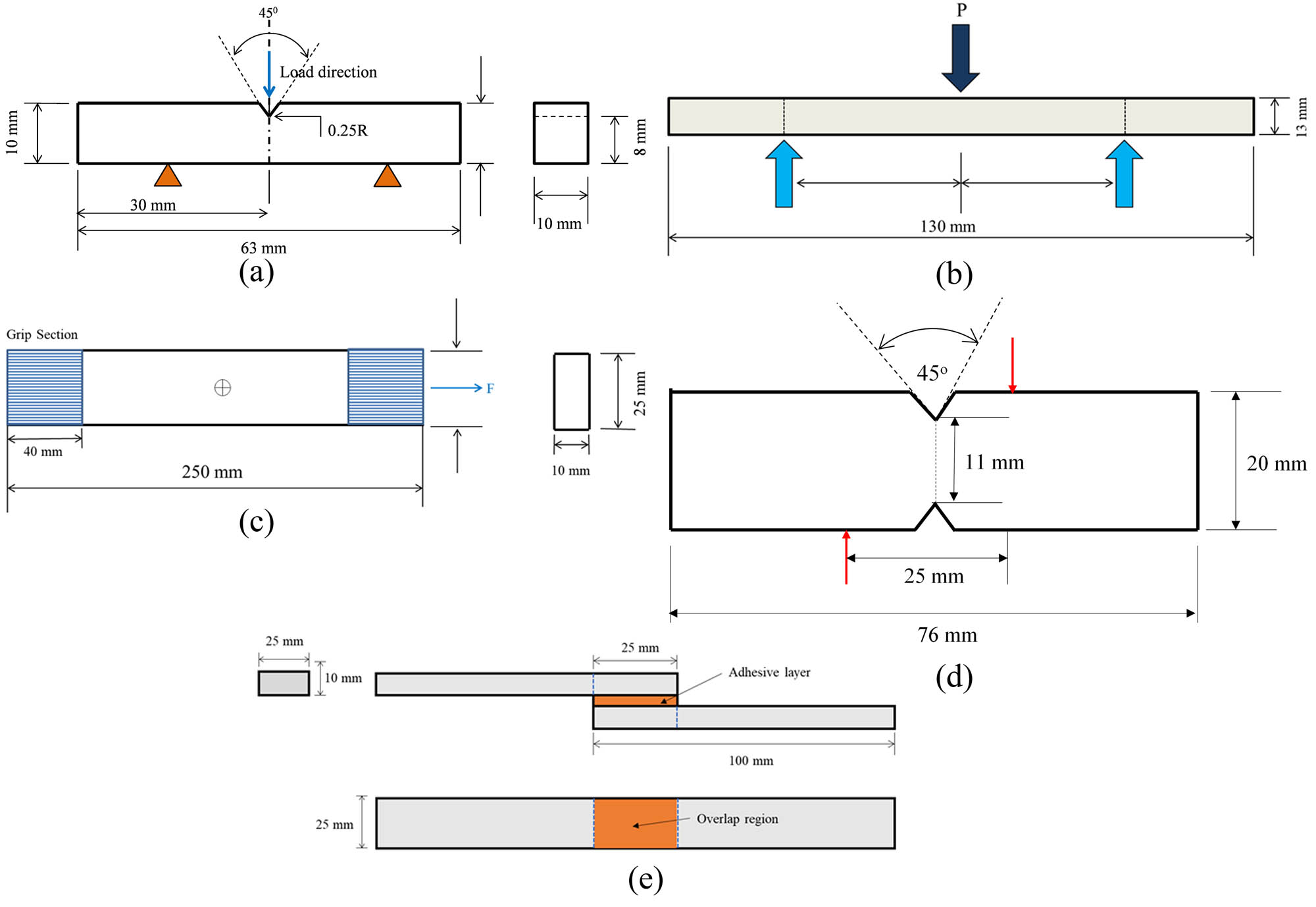

Several mechanical tests, including tensile, bending, impact, V-notched beam, and lap shear tests, were conducted to investigate the mechanical behaviour of LBCs under different layers, as seen in Figure 4. The Charpy impact test aimed to assess the brittle performances of the laminated bamboo material when subjected to an impact load. The Charpy impact machine model DB-300A, DongGuan HongTuo Instrument Co., Ltd, Dongguan, China, determined the amount of energy absorbed by a standard notched specimen when it breaks under an impact load. In the impact test, the dimension size of the rectangular test specimen was 63 mm × 10 mm × 10 mm rectangular test object with a notch angle of 45°/−45°, as presented in Figure 5a. The impact test based on ASTM D256 [25] was conducted at the Materials and Construction Laboratory, Department of Naval Architecture, Diponegoro University, Indonesia. The impact energy of 150 J (little hammer), the impact speed of 5.2 m/s, and the pendulum angle of 150° were used. The impact strength for each variation was an average of five test specimens.

The different testing schemes of LBCs: (a) impact test, (b) flexural test, (c) tensile test, (d) V-notched beam test, and (e) shear test.

Specimen dimensions: (a) impact test, (b) tensile test, (c) bending test, (d) V-notched beam test, and (e) lap shear test.

Besides the impact test, bending test was carried out to obtain information on the strength of the material using the three-point bending method. Tests were carried out with universal testing machine (UTM) type WE-1000B, Yufeng, Zhejiang, China, with a maximum capacity of 1,000 kN. The specimen size was 130 mm × 13 mm × 10 mm, as seen in Figure 5b. The specimen dimensions and testing procedure used ASTM D7264 [26]. Bending strength on each specimen was the average of five samples tested.

A tensile test was carried out to determine the tensile strength of LBC with a testing procedure using ASTM standard D3039 [27]. The specimen size of 150 mm × 50 mm × 10 mm was prepared using water jet cutting, as seen in Figure 5c. UTM type WE-1000B, Zhejiang, China, with a maximum capacity of 1,000 kN, is used. The bottom side of the test specimen was clamped on a testing machine, with the loading slowly increasing to a particular load until the test object broke. The tensile test results provided tensile strength and modulus elasticity of specimens with different layers.

Moreover, the V-notched beam test was conducted to obtain shear strength that causes the component to be damaged/fractured due to shear loads. The test was utilised to ascertain the composite materials’ in-plane shear properties. In this test method, a sample with V notches was subjected to an asymmetrical four-point compression load, allowing for the delivery of just shear stress to the evaluation area. The specimen dimensions were 76 mm × 10 mm × 20 mm, as presented in Figure 5d. The tests were carried out on tensile testing machines using special auxiliary equipment. The V-notched shear apparatus, which included a test machine adaptor, fixture halves, and grasping blots, was developed to carry out the shear tests. The V-notched shear specimen was positioned by the gripping bolts after being inserted into the two fixture sections. Each half of the constructed fixture was connected to the testing machine heads using the test machine adaptor. The relative displacement between the two fixture parts causes shear stresses to develop in the notched specimen when the testing apparatus extends the two halves of the constructed fixture. Displacement control was applied at a 2 mm/min speed during the shear tests. The specimen dimension and testing procedure used ASTM D7078 [28].

At last, a lap shear test was conducted to determine the shear strength of adhesives for bonding materials on a single-lap-joint specimen. It is typically used to measure the strength of epoxy resin glues and measures their strength when a load is applied. The lap shear test is one of the approaches for simulating real-world loading situations. Two samples, or specimens, are bonded together before tensile force is applied to pull until shear occurs. In this case, the specimen dimensions were 100 mm × 25 mm × 10 mm, as presented in Figure 5e. Lap shear tests were performed on tensile testing machines using special auxiliary equipment. The specimen dimension and testing procedure used ASTM D5868 [29].

4 Results and discussion

4.1 Flexural test result under different numbers of bamboo layers

Flexural testing was carried out to determine the ability of the test sample to withstand the maximum bending load until the test specimen fractures. Figure 6 shows the comparative result of the three-point flexural test between the present study and previous investigation by Manik et al. [1] under different configurations of laminated bamboo layers. The material selections, the manufacturing process of LBCs, and testing specimens and procedures were similar to the previous study. The present result will be compared with the previous study under the same compaction pressure of 2 MPa. From a previous study [1], based on the previous result, LBCs with a pressure of 2 MPa produce the highest mechanical properties compared to LBCs with a pressure of 1.5 and 2.5 MPa. Figures 6 and 7 show a similar result: increasing the number of laminas increases the bending strength and modulus of LBCs. LBCs with a thinner and higher number of laminas provide a higher adhesive contact surface area than the thicker lamina. The highest tensile strength is achieved by LBCs with the laminates’ direction 0° (on-axis laminates), 7 lamina layers with 1 mm lamina thickness.

Comparison of bending strength under different numbers of layers.

Comparison of bending modulus under different numbers of layers.

The result of the present study using 45°/−45° layer orientation shows similar characteristics to the previous tensile test result with 3 different layer orientations. The specimen with 7 layers had the highest bending strength with a value of 282 MPa compared with other specimens. The specimen with 5 layers and 3 layers experienced a decreased trend, about 1.26 and 6.25%, respectively. The increase in tensile strength value with the number of layers was due to the differences in the mass fraction of the epoxy resin matrix. The higher the number of layers, the more the mass fraction/volume fraction of epoxy resin. LBCs with 7 layers had higher composition of epoxy resin than 5 layers and 3 layers of composite bamboo composites.

Compared to the previous bending strength result by Manik et al. [1], adding a fibreglass mat layer into the LBCs with 45°/−45° layer orientation caused an increasing trend in bending strength in all bamboo laminated layer variations. The result showed that the addition of fibreglass mat in 3 layers caused an increase of about 7.56%. A similar trend was also found in adding fibreglass mat in 5 layers and 7 layers. It was analysed that both materials experienced an increase of about 4.64 and 4.02%, respectively. It had been discovered that adding a fibreglass mat significantly impacted the LBC with thinner and thicker bamboo lamina. As the number of laminated bamboo layers increased, the effect of fibreglass addition gradually decreased. Further, the addition of CSM fibres into laminated bamboo at 45°/−45° direction still had lower bending strength than 0 and 0°/90°. In addition, the comparison of bending strength and acceptance strength criterion based on the BKI showed that all LBC configurations fulfilled the minimum bending strength of 150 MPa.

Figure 7 compares the bending MOE between the present study and previous study results [1] under different numbers of laminated bamboo layers. The current bending modulus results showed that adding a fibreglass mat layer into a bamboo composite specimen with 45°/−45° layer orientation could increase the bending MOE. A similar result was also found that bamboo composite with 7 layers had the highest bending modulus compared to 3- and 5-layer configurations. The bending modulus of bamboo composite with 3- and 5-layer configurations decreased by about 7.09 and 1.29%, respectively, compared with 7-layer configurations. Moreover, compared with the previous result [1], adding a fibreglass mat layer to the composite specimen caused an increase of about 7.46% in 3 layers, 5.52% in 5 layers, and 4.73% in 7 layers. However, the addition of CSM fibres to laminated bamboo in the 45°/−45° direction still had a lower bending modulus than 0 and 0°/90° directions. Compared to the acceptance criterion by the BKI standard [30], the bending modulus value of all LBCs was above the minimum bending modulus of 6.86 GPa, as seen in Figure 7.

4.2 Tensile test result under different numbers of bamboo layers

Tensile strength/ultimate tensile strength is the maximum stress a composite can withstand when stretched before the material fractures. The tensile strength could generally be found by performing a tensile test and the measured strain and stress value changes. The highest point of the stress–strain curve is called the ultimate tensile strength. The strength value does not depend on the size of the material but on the type of the material. Figure 8 shows the comparative tensile strength result under different layers. In the present result, at 45°/−45° layer orientation, it was analysed that the highest tensile strength was found in the laminated bamboo specimen with 7 layers at a value of 98.1 MPa. Moreover, specimens with 3 and 5 layers had a tensile strength of about 84.92 and 91.08 MPa, respectively. Those values decreased approximately by 13.20% for 3 layers and 6.92% for 5 layers compared with specimens with 7 layers. This result has the same phenomenon as mechanical testing conducted by Manik et al. [1] at the same compaction pressure of 2 MPa. The previous study showed that the LBCs with thinner bamboo lamina reinforcement and more layers had the maximum tensile strength, even though it had a lower mass fraction than bamboo. A previous study [1] also noted that the tensile strength of the LBCs did not considerably increase when the compaction pressure was increased from 2 to 2.5 MPa. Tensile strength variations are less than the test’s standard deviation. Therefore, it can be said that the tensile properties of LBCs are not significantly affected by the pressure increase from 2 to 2.5 MPa.

Comparison of tensile strength results under different numbers of layers.

In further investigation, Figure 8 shows that adding a fibreglass mat to an LBC improved the tensile strength. Compared to the earlier discovery of the formation of LBCs with a comparable number of layers without employing fibreglass mat [1], the tensile strength of 3-layer, 5-layer, and 7-layer specimens increased by about 17.73, 12.44, and 11.19%, respectively. It was found that the addition of fibreglass mat significantly influenced the LBC with lower and thicker bamboo lamina. The influence of fibreglass addition gradually decreased as the number of bamboo laminated layers increased. However, adding fibreglass mat into specimen with 45°/−45° layer orientation still had lower tensile strength compared to specimens with 0 and 0°/90°.

The relationship between the tensile strength of LBCs and the mass fraction of LBCs shows that the highest tensile strength was found in composites with thinner bamboo reinforcement and a higher number of layers even with a lower bamboo fibre mass fraction. Previous research [31] reported using the red semantan (Gigantochloa scortechinii) bamboo species, woven bamboo fibre (woven bamboo) with a mass fraction (wt%) of bamboo lamina of 33% and a mass fraction (wt%) of epoxy matrix of 67%, was able to produce a maximum tensile strength of 89 MPa. Rassiah et al. [17] used LBCs with different types of bamboo and matrices (Gigantochloa scortechinii and UP). They reported that the thicker the bamboo slats, the lower the tensile strength and bending strength.

In addition, tensile strength of all specimens in the previous study [1] had a lower value than the tensile strength threshold given by BKI. Figure 8 shows that with the addition of a fibreglass mat layer to LBCs in the present study, only a sample with 7 layers fulfilled the BKI tensile strength standard (98 MPa). It can be inferred that adding fibreglass mat layers into a bamboo composite with 7 layers successfully improves tensile strength and achieves the tensile strength threshold.

The tensile MOE is a number used to measure a material’s resistance to elastic deformation when a force is applied to the specimen. The elastic modulus of a specimen is defined as the slope of the stress–strain curve in the elastic deformation region. It is shown in Figure 9 that increasing the number of layers caused an increase in the modulus elasticity. Being analysed at 45°/−45° layer orientation, the highest modulus elasticity was found in a specimen with 7 layers with 940.83 MPa. The modulus elasticity of a specimen with 3 layers was 26.47% lower than that of a specimen with 7 layers. Moreover, the samples with 5 layers experienced a lower trend nearly 14.19% lesser than those with 7 layers. Furthermore, a comparison of modulus of elasticity between the current result and the previous study [1] at the same compaction pressure of 2 MPa revealed that adding a fibreglass mat increased the modulus elasticity value. The increased percentages on 3 layers, 5 layers, and 7 layers were 11.95, 4.65, and 4.77%, respectively. Moreover, compared to the BKI standard for tensile MOE, the only specimen with 5 and 7 layers at layer orientation of 45°/−45° had a tensile modulus above the given threshold. The addition of a fibreglass mat layer caused improvement in tensile modulus in specimens with 5 layers. In contrast, in the previous study, the tensile modulus had a lower value than the given BKI threshold (6.86 GPa). In general recommendation, the LBC using other layer orientations (0° and 0°/90°) with superior tensile properties is recommended to be applied as a ship structure.

Comparison of MOE results under different numbers of layers.

4.3 Result of impact test under different numbers of bamboo layers

In this case, the impact strength was used to measure the material’s capability to withstand a suddenly applied load and was expressed in terms of energy. Impact test is used when ship structure experiences impact load due to ship collision, ship-jetty collision, ship-bridge collision, slamming phenomenon, etc. Impact testing aimed to determine the brittle nature of the test specimen against impact load. Impact testing required energy to break the specimen with one hit using a hammer with a specific weight that is dropped by releasing it from a certain angle. The number of layers strongly influenced the impact strength value in the LBC. Figure 10 compares the impact strength of the bamboo laminate composite to the variation in the number of layers. The impact strength increased as the number of layers increased. LBCs with the highest number of layers (7 layers) were formed from bamboo fibres with a thinner thickness (1 mm). Similar findings can be found compared with previous mechanical testing (bending and tensile tests). The optimum mass fraction can be achieved by a composition of 35% epoxy resin and 65% bamboo lamina.

Comparison of impact test results under different numbers laminated layers.

The impact strength of the specimen with 7 layers was higher than the specimen with 3 and 5 layers, where the highest impact strength can be found in a sample with 7 layers with 0° layer orientation. Adding fibreglass mat on 45°/−45° specimen increased the impact strength value from 3 layers to 5 layers by 5.68%. Then, there was an increase in the impact strength value from 3 layers to 7 layers by 15.27%. Compared to the specimen without a fibreglass mat layer, the addition of fibreglass mat causes an increase of about 18.1% in 3 layers, 22.3% in 5 layers, and 22.8% in 7 layers, respectively. However, even after adding fibreglass layer, the impact strength was still below the impact threshold given by BKI acceptance criteria. It can be found that only specimens with 0° layer orientation could fulfil the BKI standard at 150 MPa.

An important recommendation in this study is to improve the strength properties of LBCs by using a thinner bamboo lamina with a higher number of bamboo layers. It is assumed that the ability of the epoxy resin to penetrate the thinner pores of the Apus bamboo fibre increases, thereby increasing the interfacial strength of the bamboo layer. In general, the impact strength of composite materials increased with increase in in the fibre content, but the lower impact strength values at higher fibre compositions may be due to improper adhesion between matrix and fibre [32].

4.4 Result of V-notched beam test under different numbers of bamboo layers

The V-notched beam testing method was used to determine the in-plane shear properties of the LBC under different numbers of layers. This test method applied an asymmetrical four-point compression load to a sample with V notches, which enabled the application of only shear stress on the evaluation area. This method is ideal for testing various CFRP laminate materials, including unidirectional, orthogonally laminated, and discontinuous fibre materials. Figure 11 compares the shear strength between the present study (45°/45° bamboo + CSM) under different layers and previous results reported by Yang et al. [33] with a similar method using ASTM D7078. It can be observed from the present result that the highest shear strength was found in the specimen with 7 layers at 98.91 MPa. Specimen with 3 and 5 layers showed lower shear strength, about 22.75, and a 9.48% decrease compared to 7-layer specimens. Similar to the previous explanation, the recommendation for improving the strength properties of LBCs can be achieved by using thinner bamboo laminated with a higher number of bamboo layers, as recommended by other mechanical testings.

V-notched beam test results under different numbers of layers.

Compared to the shear strength result reported by Yang et al. [33], the present material combination of laminated bamboo – CSM – epoxy adhesive achieved higher shear strength. Yang et al. [33] investigated a comparison of shear strength under four different bamboo material combinations. They created a basalt fibre reinforced polymer (BFRP) bamboo sandwich structure using two methods: laminated bamboo lumber (LBL) and parallel bamboo strand lumber (PBSL) [34]. Bamboo tubes were disassembled into thin flat laminae for LBL, then laminated with an adhesive to form various structural members [35]. The PBSL, on the other hand, was constructed by disassembling bamboo tubes into filament bundles and then gluing them together with an adhesive to form certifiable structural members [36]. The raw bamboo material of PBSL and LBL was the Moso bamboo from Jiangxi Province, China. Based on data in Figure 11, the BFRP-bamboo sandwich structure using PBSL had superior shear properties to BFRP-LBL. Moreover, the shear strength of the BFRP-LBL and BFRP-PBSL increased by 44 and 22% compared to LBL and PBSL specimens. Therefore, the novel BFRP-bamboo sandwich structure can effectively improve the shear capacity of bamboo lumber. The findings are similar to the present study: adding a fibreglass mat layer to laminated bamboo increased the mechanical properties.

4.5 Result of a lap shear test under different numbers of bamboo layers

Adhesive bond strength is one of the most critical measures when comparing different formulations of LBCs. In this case, a lap shear test was conducted to measure the bonding strength of the epoxy adhesive layer. Based on data in Figure 12, the bonding strength of the epoxy adhesive joint between two engineered bamboo was 18.96 MPa. In the previous investigation by Liu et al. [37], the bonding properties between engineered bamboo and steel substrates had a lower value of about 13.51 MPa. They used Commercial Selleys Araldite Super Strength bicomponent epoxy (New South Wales, Australia) as adhesive material. Shah et al. [38] compared five commercial adhesive materials for adhesion testing of laminated bamboos, such as polyurethane (Purbond, Henkel, Switzerland), polyvinyl acetate (Lumberjack wood adhesive, Everbuild, UK), soy-flour based adhesive (Soyad, Solenis, USA), resorcinol phenol formaldehyde (Polyproof, Polyvine, UK), and urea phenol formaldehyde (Cascamite, Polyvine, UK). The investigation showed that the resorcinol phenol formaldehyde adhesive type had the highest bonding strength compared to other adhesive types. Moreover, Guan et al. [39] explored another type of resin and analysed the bonding strength of laminated bamboo using phenol formaldehyde resin with a maximum bonding strength of about 14.08 MPa. Based on this investigation, it can be summarised that each adhesive/glue type for bamboo joint has different bonding strengths.

Lap shear test results under different types of adhesive material.

4.6 Future studies suggestion on the manufacturing strategy for fishing vessel structure

Following a series of mechanical tests to develop the basic mechanical properties of the LBC, the implementation for manufacturing a ship structure must be investigated. The compaction pressure method is used to manufacture the laminated bamboo. This method employs thin laminated bamboo that is arranged and glued together to create a bamboo board of a specific dimension and thickness. To improve the adhesive strength between the layers, a cold press machine was used to press the bamboo board. Based on the findings of this study, it is possible to conclude that laminated bamboo has greater strength.

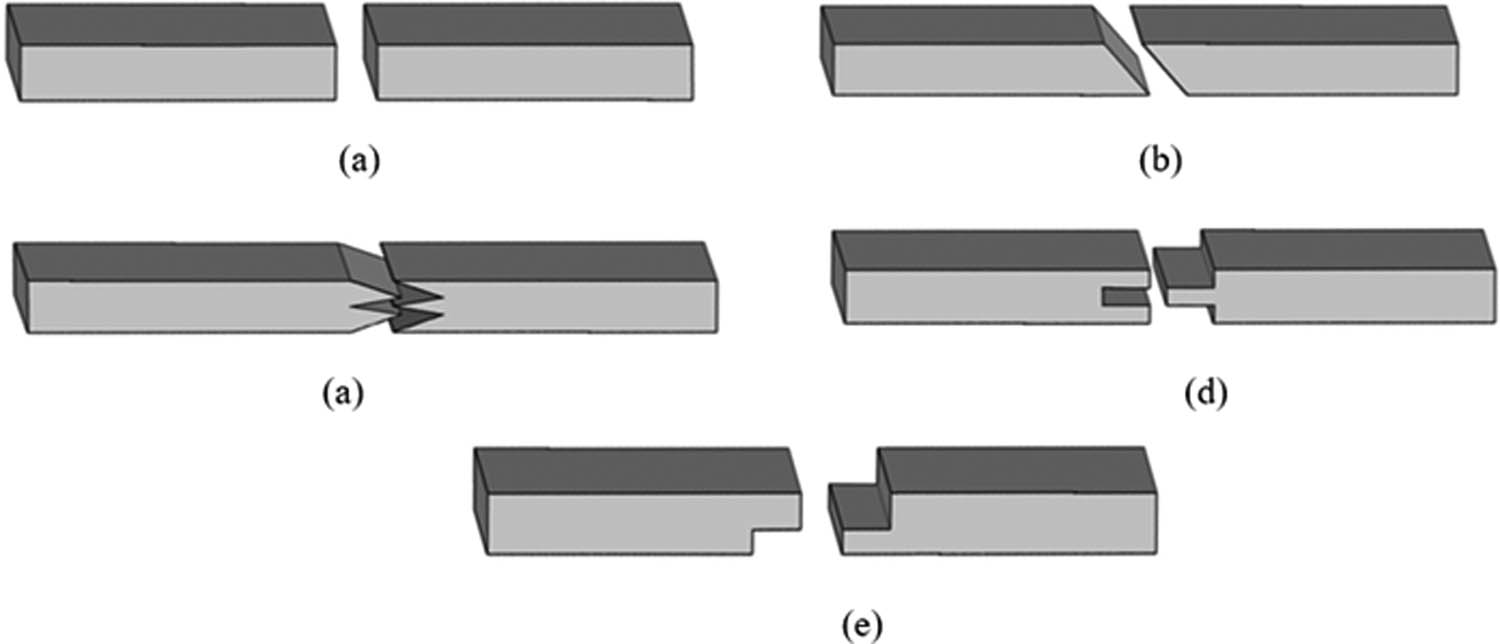

Several bamboo boards can be combined using mechanical joints to produce a large panel in the ship structure manufacturing technique. Laminate joints are divided into solid jointed boards and connecting boards made of intact sawn wood. A non-solid jointed board is a connecting board made up of joined connecting slats or short sawn wood. There are five types of connecting blades and boards: butt joints, finger joints, scarf joints, tongue and groove joints, and desk joints. Figure 13 depicts five different types of joints. Future investigation on the joint strength of the LBC is crucial.

Joint types of laminated composite: (a) butt joint, (b) scarf joint, (c) finger joint, (d) tongue and groove joint, and (e) desk joint.

In the early stages of development, flat-based typical structures such as decks, walls, and superstructure members, among others are better suited for this manufacturing technique. Further, developing curved-based bamboo boards can be a more complicated process with complex manufacturing techniques. For example, flat bamboo boards can be arranged and then joined together to create a deck with specific scantling calculations. The values of tensile strength, flexure, and MOE collected from mechanical testing determine the size of the fishing vessel construction components in the scantling calculation. The size of the ship construction components such as the shell, deck, wall, stiffener, etc. is determined using the BKI standard small vessel up to 24 m [40].

5 Concluding remarks

Several mechanical testings to investigate the material behaviour under different Apus bamboo laminated layers have been reviewed with the following conclusions:

Several mechanical tests, including tensile, bending, impact, and lap shear tests, showed that laminated bamboo with 7 layers had superior mechanical properties, followed by laminated bamboo with 5 and 3 layers. Increasing mechanical properties can be achieved by using bamboo composites with thinner bamboo lamina thickness and higher bamboo layers with a higher epoxy resin mass matrix. The mass matrix of 35 wt% epoxy resin and 65 wt% bamboo lamina was an optimal mass fraction composition.

Due to tensile and bending loads, the mechanical characteristics of the LBC were improved by adding a fibreglass mat. Increases in bending strength were roughly 7.56, 4.64, and 4.02%, respectively, due to the addition of fibreglass mat in 3 layers, 5 layers, and 7 layers. In addition, tensile strength improved by 17.73, 12.44, and 11.19% on the 3 layers, 5 layers, and 7 layers, respectively. The influence of fibreglass addition on increasing mechanical properties significantly decreased as the number of bamboo laminated layers increased.

Adding a fibreglass layer to a bamboo composite was only successful in specimens with 7 layers that satisfied the bending and tensile strength parameters, according to the BKI strength requirements. The presence of fibreglass mat in bamboo composites with 3 or 5 layers did not meet the standard criterion.

Based on this study, it is presumed that this work could become a topic for future research. One possibility is to conduct an experimental study to determine the effect of various adhesive or glue types/specifications and joint types on adhesive strength. A scantling calculation and economic aspect for building fishing vessels is also an option that should be considered in future work.

Acknowledgment

The research has received financial support from the “Riset Pengembangan dan Penerapan, Diponegoro University 2021” research scheme under contract number 233-133/UN7.6.1/PP/2021. The authors gratefully acknowledge the support.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

[1] Manik P, Suprihanto A, Nugroho S, Sulardjaka S. The effect of lamina configuration and compaction pressure on mechanical properties of laminated Gigantochloa apus composites. East-Eur J Enterp Technol. 2021;6/12(114):62–73.10.15587/1729-4061.2021.243993Search in Google Scholar

[2] Holmes JW, Brøndsted P, Sørensen BF, Jiang Z, Sun Z, Chen X. Development of a bamboo-based composite as a sustainable green material for wind turbine blades. Wind Eng. 2009;33(2):197–210.10.1260/030952409789141053Search in Google Scholar

[3] Girisha C, Sanjeevamurthy GR. Tensile properties of natural fiber-reinforced epoxy-hybrid composites. Int J Mod Eng Res. 2012;2(2):471–4.Search in Google Scholar

[4] Akinyemi BA, Omoniyi TE. Effect of experimental wet and dry cycles on bamboo fibre reinforced acrylic polymer modified cement composite. J Mech Behav Mater. 2020;29(1):86–93.10.1515/jmbm-2020-0009Search in Google Scholar

[5] Verma CS, Chariar VM. Development of layered laminate bamboo composite and their mechanical properties. Compos B Eng. 2012;43(3):1063–9.10.1016/j.compositesb.2011.11.065Search in Google Scholar

[6] Sharma B, Gatóo A, Bock M, Ramage M. Engineered bamboo for structural applications. Constr Build Mater. 2015;81:66–73.10.1016/B978-0-08-102704-2.00021-4Search in Google Scholar

[7] Manik P, Sisworo SJ, Rindo G. Technical and economic analysis of the usages glued laminated of apus and petung bamboo as an alternative material component of timber shipbuilding. Mater Today Proc. 2019;13:115–20.10.1016/j.matpr.2019.03.199Search in Google Scholar

[8] Manik P, Suprihanto A, Sulardjaka, Nugroho S. Analysis of salinity from seawater on physical and mechanical properties of laminated bamboo fiber composites with an epoxy resin matrix for ship skin materials. Int Rev Mech Eng. 2021;15(7):365–77.10.15866/ireme.v15i7.20824Search in Google Scholar

[9] Forestry Economics and Policy Division. Global Forest Resources Assessment 2010 – Main Report. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of United Nations; 2010.Search in Google Scholar

[10] Hansen MC, Potapov PV, Moore R, Hancher M, Turubanova SA, Tyukavina A, et al. High resolution of global maps 21st-century forest cover change. Science. 2013;342(6160):850–3.10.1126/science.1244693Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] Supomo H, Manfaat D, Zubaydi A. Flexure strength analysis of laminated bamboo slats (Bambusa Arundinacea) for constructing small boat fishing shell. IJST. 2015;157:1–9.10.3940/rina.ijsct.2015.b1.167Search in Google Scholar

[12] Hassoon O, Abed M, Oleiwi J, Tarfaoui M. Experimental and numerical investigation of drop weight impact of aramid and UHMWPE reinforced epoxy. J Mech Behav Mater. 2022;31(1):71–82.10.1515/jmbm-2022-0008Search in Google Scholar

[13] Prabowo AR, Tuswan T, Adiputra R, Do Q, Sohn J, Surojo E, et al. Mechanical behavior of thin-walled steel under hard contact with rigid seabed rock: Theoretical contact approach and nonlinear FE calculation. J Mech Behav Mater. 2021;30(1):156–70.10.1515/jmbm-2021-0016Search in Google Scholar

[14] Kathavate V, Amudha K, Adithya L, Pandurangan A, Ramesh N, Gopakumar K. Mechanical behavior of composite materials for marine applications – an experimental and computational approach. J Mech Behav Mater. 2018;27(1–2):20180003.10.1515/jmbm-2018-0003Search in Google Scholar

[15] Supomo H, Djatmiko EB, Zubaydi A, Baihaqi I. Analysis of the adhesiveness and glue type selection manufacturing of bamboo laminate composite for fishing boat building material. Appl Mech Mater. 2018;874:155–64.10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMM.874.155Search in Google Scholar

[16] Amatosa T, Jr, Loretero M, Santos RB, Giduquio MB. Analysis of seawater treated laminated bamboo composite for structural application. Nat Environt Pollut Technol. 2019;18:307–12.Search in Google Scholar

[17] Rassiah K, Megat Ahmad MMH, Ali A. Mechanical properties of laminated bamboo strips from Gigantochloa Scortechinii/polyester composites. Mater Des. 2014;57:551–9.10.1016/j.matdes.2013.12.070Search in Google Scholar

[18] Manik P, Yudo H, Arswendo B. Technical and economical analysis of the use of glued laminated from combination of apus bamboo and meranti wood as an alternative material component in timber shipbuilding. Int J Civ Eng. 2018;9(7):1800–11.Search in Google Scholar

[19] Rindo G, Manik P, Jokosisworo S, Putri C, Wilhelmina P. Effect analysis of the direction of fiber arrangement on interfaces of laminated bamboo fiber as a construction material for wood vessel hulls. AIP Conf Proc. 2020;2262(1):030002.10.1063/5.0016147Search in Google Scholar

[20] Dransfield S, Widjaja EA. Plant resources of South-East Asia. Vol. 7. Pudoc: 1995.Search in Google Scholar

[21] Rassiah K, Megat Ahmad MMH. A review on mechanical properties of bamboo fiber reinforced polymer composite. Aust Basic Appl Sci. 2013;7(8):247–53.Search in Google Scholar

[22] Manik P, Suprihanto A, Sulardjaka, Nugroho S. Technical analysis of increasing the quality of apus bamboo fiber (Gigantochloa Apus) with alkali and silane treatments as alternative composites material for ship skin manufacturing. AIP Conf Proc. 2020;2262(1):050014.10.1063/5.0015696Search in Google Scholar

[23] Shokrieh MM, Danesh M, Esmkhani M. A combined micromechanical-energy method to predict the fatigue life of nanoparticles/chopped strand mat/polymer hybrid nanocomposites. Compos Struct. 2015;133:886–91.10.1016/j.compstruct.2015.08.003Search in Google Scholar

[24] Diniardi E, Nelfiyanti N, Mahmud KH, Basri H, Ramadhan AI. Analysis of the tensile strength of composite material from fiber bags. J Appl Sci Adv Technol. 2019;2(2):39–48.Search in Google Scholar

[25] ASTM D256. American society for testing and materials. Standard test methods for determining the izod pendulum impact resistance of plastics. West Conshohocken (PA), USA; 2015.Search in Google Scholar

[26] ASTM D7264. American society for testing and material. Flexural properties testing of polymer matrix composite materials. West Conshohocken (PA), USA; 2003.Search in Google Scholar

[27] ASTM D3039. American society for testing and materials. Standard test method for tensile properties of polymer matrix composite materials. West Conshohocken (PA), USA; 2002.Search in Google Scholar

[28] ASTM D7078. American society for testing and materials. Standard test method for shear properties of composite materials by the V-notched beam method. West Conshohocken (PA), USA; 2006.Search in Google Scholar

[29] ASTM D5868. American society for testing and materials. Standard test method for lap shear adhesion for fiber reinforced plastic (FRP) bonding. West Conshohocken (PA), USA; 2016.Search in Google Scholar

[30] Biro Klasifikasi Indonesia. Rules for The Classification and Construction Part 3. Special Ships, Volume V Rules for Fibreglass Reinforced Plastic Ships; 2016.Search in Google Scholar

[31] Rassiah K, Megat Ahmad MMH, Ali A, Abdullah AH, Nagapan S. Mechanical properties of layered laminated woven bamboo Gigantochloa scortechinii/epoxy composites. J Polym Env. 2017;26(4):1328–42.10.1007/s10924-017-1040-3Search in Google Scholar

[32] Lokesh P, Surya Kumari TSA, Gopi R, Loganathan GB. A study on mechanical properties of bamboo fiber reinforced polymer composite. Mater Today Proc. 2020;22:897–903.10.1016/j.matpr.2019.11.100Search in Google Scholar

[33] Yang Y, Fahmy MF, Pan Z, Zhan Y, Wang R, Wang B, et al. Experimental study on basic mechanical properties of new BFRP-bamboo sandwich structure. Constr Build Mater. 2020;264:120642.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.120642Search in Google Scholar

[34] Li H, Wu G, Zhang Q, Su J. Mechanical evaluation for laminated bamboo lumber along two eccentric compression directions. J Wood Sci. 2016;62(6):503–17.10.1007/s10086-016-1584-1Search in Google Scholar

[35] Reynolds T, Sharma B, Serrano E, Gustafsson PJ, Ramage MH. Fracture of laminated bamboo and the influence of preservative treatments. Compos Part B-Eng. 2019;174:107017.10.1016/j.compositesb.2019.107017Search in Google Scholar

[36] Tan C, Li H, Wei D, Lorenzo R, Yuan C. Mechanical performance of parallel bamboo strand lumber columns under axial compression: Experimental and numerical investigation. Constr Build Mater. 2020;231:117168.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2019.117168Search in Google Scholar

[37] Liu W, Zheng Y, Hu X, Han X, Chen Y. Interfacial bonding enhancement on the epoxy adhesive joint between engineered bamboo and steel substrates with resin pre-coating surface treatment. Wood Sci Technol. 2019;53(4):785–99.10.1007/s00226-019-01109-9Search in Google Scholar

[38] Shah DU, Sharma B, Ramage MH. Processing bamboo for structural composites: Influence of preservative treatments on surface and interface properties. Int J Adhes Adhes. 2018;85:15–22.10.1016/j.ijadhadh.2018.05.009Search in Google Scholar

[39] Guan M, Yong C, Wang L. Microscopic characterization of modified phenol-formaldehyde resin penetration of bamboo surfaces and its effect on some properties of two-ply bamboo bonding interface. BioResources. 2014;9(2):1953–63.10.15376/biores.9.2.1953-1963Search in Google Scholar

[40] Biro Klasifikasi Indonesia. Rules for small vessel up to 24 m. 2013 ed. Vol. VII. Jakarta: BKI; 2013.Search in Google Scholar

© 2022 Parlindungan Manik et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Calcium carbonate nanoparticles of quail’s egg shells: Synthesis and characterizations

- Effect of welding consumables on shielded metal arc welded ultra high hard armour steel joints

- Stress-strain characteristics and service life of conventional and asphaltic underlayment track under heavy load Babaranjang trains traffic

- Corrigendum to: Statistical mechanics of cell decision-making: the cell migration force distribution

- Prediction of bearing capacity of driven piles for Basrah governatore using SPT and MATLAB

- Investigation on microstructural features and tensile shear fracture properties of resistance spot welded advanced high strength dual phase steel sheets in lap joint configuration for automotive frame applications

- Experimental and numerical investigation of drop weight impact of aramid and UHMWPE reinforced epoxy

- An experimental study and finite element analysis of the parametric of circular honeycomb core

- The study of the particle size effect on the physical properties of TiO2/cellulose acetate composite films

- Hybrid material performance assessment for rocket propulsion

- Design of ER damper for recoil length minimization: A case study on gun recoil system

- Forecasting technical performance and cost estimation of designed rim wheels based on variations of geometrical parameters

- Enhancing the machinability of SKD61 die steel in power-mixed EDM process with TGRA-based multi criteria decision making

- Effect of boron carbide reinforcement on properties of stainless-steel metal matrix composite for nuclear applications

- Energy absorption behaviors of designed metallic square tubes under axial loading: Experiment-based benchmarking and finite element calculation

- Synthesis and study of magnesium complexes derived from polyacrylate and polyvinyl alcohol and their applications as superabsorbent polymers

- Artificial neural network for predicting the mechanical performance of additive manufacturing thermoset carbon fiber composite materials

- Shock and impact reliability of electronic assemblies with perimeter vs full array layouts: A numerical comparative study

- Influences of pre-bending load and corrosion degree of reinforcement on the loading capacity of concrete beams

- Assessment of ballistic impact damage on aluminum and magnesium alloys against high velocity bullets by dynamic FE simulations

- On the applicability of Cu–17Zn–7Al–0.3Ni shape memory alloy particles as reinforcement in aluminium-based composites: Structural and mechanical behaviour considerations

- Mechanical properties of laminated bamboo composite as a sustainable green material for fishing vessel: Correlation of layer configuration in various mechanical tests

- Singularities at interface corners of piezoelectric-brass unimorphs

- Evaluation of the wettability of prepared anti-wetting nanocoating on different construction surfaces

- Review Article

- An overview of cold spray coating in additive manufacturing, component repairing and other engineering applications

- Special Issue: Sustainability and Development in Civil Engineering - Part I

- Risk assessment process for the Iraqi petroleum sector

- Evaluation of a fire safety risk prediction model for an existing building

- The slenderness ratio effect on the response of closed-end pipe piles in liquefied and non-liquefied soil layers under coupled static-seismic loading

- Experimental and numerical study of the bulb's location effect on the behavior of under-reamed pile in expansive soil

- Procurement challenges analysis of Iraqi construction projects

- Deformability of non-prismatic prestressed concrete beams with multiple openings of different configurations

- Response of composite steel-concrete cellular beams of different concrete deck types under harmonic loads

- The effect of using different fibres on the impact-resistance of slurry infiltrated fibrous concrete (SIFCON)

- Effect of microbial-induced calcite precipitation (MICP) on the strength of soil contaminated with lead nitrate

- The effect of using polyolefin fiber on some properties of slurry-infiltrated fibrous concrete

- Typical strength of asphalt mixtures compacted by gyratory compactor

- Modeling and simulation sedimentation process using finite difference method

- Residual strength and strengthening capacity of reinforced concrete columns subjected to fire exposure by numerical analysis

- Effect of magnetization of saline irrigation water of Almasab Alam on some physical properties of soil

- Behavior of reactive powder concrete containing recycled glass powder reinforced by steel fiber

- Reducing settlement of soft clay using different grouting materials

- Sustainability in the design of liquefied petroleum gas systems used in buildings

- Utilization of serial tendering to reduce the value project

- Time and finance optimization model for multiple construction projects using genetic algorithm

- Identification of the main causes of risks in engineering procurement construction projects

- Identifying the selection criteria of design consultant for Iraqi construction projects

- Calibration and analysis of the potable water network in the Al-Yarmouk region employing WaterGEMS and GIS

- Enhancing gypseous soil behavior using casein from milk wastes

- Structural behavior of tree-like steel columns subjected to combined axial and lateral loads

- Prospect of using geotextile reinforcement within flexible pavement layers to reduce the effects of rutting in the middle and southern parts of Iraq

- Ultimate bearing capacity of eccentrically loaded square footing over geogrid-reinforced cohesive soil

- Influence of water-absorbent polymer balls on the structural performance of reinforced concrete beam: An experimental investigation

- A spherical fuzzy AHP model for contractor assessment during project life cycle

- Performance of reinforced concrete non-prismatic beams having multiple openings configurations

- Finite element analysis of the soil and foundations of the Al-Kufa Mosque

- Flexural behavior of concrete beams with horizontal and vertical openings reinforced by glass-fiber-reinforced polymer (GFRP) bars

- Studying the effect of shear stud distribution on the behavior of steel–reactive powder concrete composite beams using ABAQUS software

- The behavior of piled rafts in soft clay: Numerical investigation

- The impact of evaluation and qualification criteria on Iraqi electromechanical power plants in construction contracts

- Performance of concrete thrust block at several burial conditions under the influence of thrust forces generated in the water distribution networks

- Geotechnical characterization of sustainable geopolymer improved soil

- Effect of the covariance matrix type on the CPT based soil stratification utilizing the Gaussian mixture model

- Impact of eccentricity and depth-to-breadth ratio on the behavior of skirt foundation rested on dry gypseous soil

- Concrete strength development by using magnetized water in normal and self-compacted concrete

- The effect of dosage nanosilica and the particle size of porcelanite aggregate concrete on mechanical and microstructure properties

- Comparison of time extension provisions between the Joint Contracts Tribunal and Iraqi Standard Bidding Document

- Numerical modeling of single closed and open-ended pipe pile embedded in dry soil layers under coupled static and dynamic loadings

- Mechanical properties of sustainable reactive powder concrete made with low cement content and high amount of fly ash and silica fume

- Deformation of unsaturated collapsible soils under suction control

- Mitigation of collapse characteristics of gypseous soils by activated carbon, sodium metasilicate, and cement dust: An experimental study

- Behavior of group piles under combined loadings after improvement of liquefiable soil with nanomaterials

- Using papyrus fiber ash as a sustainable filler modifier in preparing low moisture sensitivity HMA mixtures

- Study of some properties of colored geopolymer concrete consisting of slag

- GIS implementation and statistical analysis for significant characteristics of Kirkuk soil

- Improving the flexural behavior of RC beams strengthening by near-surface mounting

- The effect of materials and curing system on the behavior of self-compacting geopolymer concrete

- The temporal rhythm of scenes and the safety in educational space

- Numerical simulation to the effect of applying rationing system on the stability of the Earth canal: Birmana canal in Iraq as a case study

- Assessing the vibration response of foundation embedment in gypseous soil

- Analysis of concrete beams reinforced by GFRP bars with varying parameters

- One dimensional normal consolidation line equation

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Calcium carbonate nanoparticles of quail’s egg shells: Synthesis and characterizations

- Effect of welding consumables on shielded metal arc welded ultra high hard armour steel joints

- Stress-strain characteristics and service life of conventional and asphaltic underlayment track under heavy load Babaranjang trains traffic

- Corrigendum to: Statistical mechanics of cell decision-making: the cell migration force distribution

- Prediction of bearing capacity of driven piles for Basrah governatore using SPT and MATLAB

- Investigation on microstructural features and tensile shear fracture properties of resistance spot welded advanced high strength dual phase steel sheets in lap joint configuration for automotive frame applications

- Experimental and numerical investigation of drop weight impact of aramid and UHMWPE reinforced epoxy

- An experimental study and finite element analysis of the parametric of circular honeycomb core

- The study of the particle size effect on the physical properties of TiO2/cellulose acetate composite films

- Hybrid material performance assessment for rocket propulsion

- Design of ER damper for recoil length minimization: A case study on gun recoil system

- Forecasting technical performance and cost estimation of designed rim wheels based on variations of geometrical parameters

- Enhancing the machinability of SKD61 die steel in power-mixed EDM process with TGRA-based multi criteria decision making

- Effect of boron carbide reinforcement on properties of stainless-steel metal matrix composite for nuclear applications

- Energy absorption behaviors of designed metallic square tubes under axial loading: Experiment-based benchmarking and finite element calculation

- Synthesis and study of magnesium complexes derived from polyacrylate and polyvinyl alcohol and their applications as superabsorbent polymers

- Artificial neural network for predicting the mechanical performance of additive manufacturing thermoset carbon fiber composite materials

- Shock and impact reliability of electronic assemblies with perimeter vs full array layouts: A numerical comparative study

- Influences of pre-bending load and corrosion degree of reinforcement on the loading capacity of concrete beams

- Assessment of ballistic impact damage on aluminum and magnesium alloys against high velocity bullets by dynamic FE simulations

- On the applicability of Cu–17Zn–7Al–0.3Ni shape memory alloy particles as reinforcement in aluminium-based composites: Structural and mechanical behaviour considerations

- Mechanical properties of laminated bamboo composite as a sustainable green material for fishing vessel: Correlation of layer configuration in various mechanical tests

- Singularities at interface corners of piezoelectric-brass unimorphs

- Evaluation of the wettability of prepared anti-wetting nanocoating on different construction surfaces

- Review Article

- An overview of cold spray coating in additive manufacturing, component repairing and other engineering applications

- Special Issue: Sustainability and Development in Civil Engineering - Part I

- Risk assessment process for the Iraqi petroleum sector

- Evaluation of a fire safety risk prediction model for an existing building

- The slenderness ratio effect on the response of closed-end pipe piles in liquefied and non-liquefied soil layers under coupled static-seismic loading

- Experimental and numerical study of the bulb's location effect on the behavior of under-reamed pile in expansive soil

- Procurement challenges analysis of Iraqi construction projects

- Deformability of non-prismatic prestressed concrete beams with multiple openings of different configurations

- Response of composite steel-concrete cellular beams of different concrete deck types under harmonic loads

- The effect of using different fibres on the impact-resistance of slurry infiltrated fibrous concrete (SIFCON)

- Effect of microbial-induced calcite precipitation (MICP) on the strength of soil contaminated with lead nitrate

- The effect of using polyolefin fiber on some properties of slurry-infiltrated fibrous concrete

- Typical strength of asphalt mixtures compacted by gyratory compactor

- Modeling and simulation sedimentation process using finite difference method

- Residual strength and strengthening capacity of reinforced concrete columns subjected to fire exposure by numerical analysis

- Effect of magnetization of saline irrigation water of Almasab Alam on some physical properties of soil

- Behavior of reactive powder concrete containing recycled glass powder reinforced by steel fiber

- Reducing settlement of soft clay using different grouting materials

- Sustainability in the design of liquefied petroleum gas systems used in buildings

- Utilization of serial tendering to reduce the value project

- Time and finance optimization model for multiple construction projects using genetic algorithm

- Identification of the main causes of risks in engineering procurement construction projects

- Identifying the selection criteria of design consultant for Iraqi construction projects

- Calibration and analysis of the potable water network in the Al-Yarmouk region employing WaterGEMS and GIS

- Enhancing gypseous soil behavior using casein from milk wastes

- Structural behavior of tree-like steel columns subjected to combined axial and lateral loads

- Prospect of using geotextile reinforcement within flexible pavement layers to reduce the effects of rutting in the middle and southern parts of Iraq

- Ultimate bearing capacity of eccentrically loaded square footing over geogrid-reinforced cohesive soil

- Influence of water-absorbent polymer balls on the structural performance of reinforced concrete beam: An experimental investigation

- A spherical fuzzy AHP model for contractor assessment during project life cycle

- Performance of reinforced concrete non-prismatic beams having multiple openings configurations

- Finite element analysis of the soil and foundations of the Al-Kufa Mosque

- Flexural behavior of concrete beams with horizontal and vertical openings reinforced by glass-fiber-reinforced polymer (GFRP) bars

- Studying the effect of shear stud distribution on the behavior of steel–reactive powder concrete composite beams using ABAQUS software

- The behavior of piled rafts in soft clay: Numerical investigation

- The impact of evaluation and qualification criteria on Iraqi electromechanical power plants in construction contracts

- Performance of concrete thrust block at several burial conditions under the influence of thrust forces generated in the water distribution networks

- Geotechnical characterization of sustainable geopolymer improved soil

- Effect of the covariance matrix type on the CPT based soil stratification utilizing the Gaussian mixture model

- Impact of eccentricity and depth-to-breadth ratio on the behavior of skirt foundation rested on dry gypseous soil

- Concrete strength development by using magnetized water in normal and self-compacted concrete

- The effect of dosage nanosilica and the particle size of porcelanite aggregate concrete on mechanical and microstructure properties

- Comparison of time extension provisions between the Joint Contracts Tribunal and Iraqi Standard Bidding Document

- Numerical modeling of single closed and open-ended pipe pile embedded in dry soil layers under coupled static and dynamic loadings

- Mechanical properties of sustainable reactive powder concrete made with low cement content and high amount of fly ash and silica fume

- Deformation of unsaturated collapsible soils under suction control

- Mitigation of collapse characteristics of gypseous soils by activated carbon, sodium metasilicate, and cement dust: An experimental study

- Behavior of group piles under combined loadings after improvement of liquefiable soil with nanomaterials

- Using papyrus fiber ash as a sustainable filler modifier in preparing low moisture sensitivity HMA mixtures

- Study of some properties of colored geopolymer concrete consisting of slag

- GIS implementation and statistical analysis for significant characteristics of Kirkuk soil

- Improving the flexural behavior of RC beams strengthening by near-surface mounting

- The effect of materials and curing system on the behavior of self-compacting geopolymer concrete

- The temporal rhythm of scenes and the safety in educational space

- Numerical simulation to the effect of applying rationing system on the stability of the Earth canal: Birmana canal in Iraq as a case study

- Assessing the vibration response of foundation embedment in gypseous soil

- Analysis of concrete beams reinforced by GFRP bars with varying parameters

- One dimensional normal consolidation line equation