Studying the effect of shear stud distribution on the behavior of steel–reactive powder concrete composite beams using ABAQUS software

-

Yasar Ameer Ali

, Mayadah W. Falah

Abstract

Using the ABAQUS software, this article presents a numerical investigation on the effects of various stud distributions on the behavior of composite beams. A total of 24 continuous 2-span composite beam samples with a span length of 1 m were examined (concrete slab at the top and steel I-section at the bottom). The concrete slab used is made of a reactive powder concrete with a compressive strength of 100.29 MPa. The total depth of each sample was 0.220 m. The samples were separated into four groups. The first group involved 6 specimens with shear connectors distributed into 2 rows with different distances (65, 85, 105, 150, 200, and 250 mm). The second group had the same spacing of shear connectors as the first group except that the shear connectors were distributed with one row along the longitudinal axis. The third group consisted of six specimens with single and double shear connectors distributed along the longitudinal axis. The fourth group included six specimens with one row of shear connectors arranged in a staggered distribution along the longitudinal axis. Results show that the optimum spacing was 105 mm in all groups and the deflection in group four fluctuated up and down due to the non-symmetrical distribution of the shear connectors.

1 Introduction

Composite construction is a common theme in buildings and bridges. Composite members can be formed by connecting different materials together to create a single member benefiting from the good properties of these materials [1,2,3,4]. There are two methods in creating a composite section. The first is by mixing different materials having suitable properties. The second is the arrangement of different sections with different materials to obtain the best properties. Shear connectors are widely used between steel and concrete to produce composite steel–concrete beams to reduce or prevent the relative displacement between concrete and steel [5,6].

Figure 1(a) shows the obvious slip between concrete and steel due to the lack of interaction between concrete and steel, while (b) shows the composite action due to the bond created by the shear connector which causes a reduction in both deflection and strain between the sections (concrete and steel). Shear connectors cannot achieve a perfect rigid connection between materials, but it widely eliminates the interface slip. Using a proper connection leads the two components to work as one unit, and this connection is known as full or complete interaction [8,9,10,11,12,13,14].

![Figure 1

(a) Non-composite and (b) composite beam [7].](/document/doi/10.1515/jmbm-2022-0046/asset/graphic/j_jmbm-2022-0046_fig_001.jpg)

(a) Non-composite and (b) composite beam [7].

However, all shear connectors are flexible to a certain degree and allow a certain amount of slip in the interface. As a result, this problem may occur when less connectors than the required number is used.

The key to composite work is the force transfer in the interface. This mechanism occurs by using shear connectors with different sections. Shear connectors should resist the horizontal forces developed between the composite materials [15,16].

To investigate the behavior of the composite concrete–steel beam joined by headed stud shear connectors, a finite element model is created [17,18]. The software program ABAQUS was utilized. The model’s results were compared with experimental data and Practice Codes. The differences in concrete strength and the diameter of the shear connectors were investigated in parametric tests. The results reveal that the shear capacity of the headed studs could be overestimated when using finite element analysis.

To determine the shear and flexural strengths of composite simply supported beams, the finite element method is used [19,20,21,22]. These composite beams are made of steel and concrete and are subjected to a combination of shear and bending loads. A finite element model was built to compensate for the geometric nonlinearity of the beams, and the results were compared with the experimental results. The concrete slab’s contributions to the composite beam’s shear and moment capacity are calculated using a finite element model. For composite beams that are simply supported, the proposed design models offer a dependable and cost-effective method of design. The finite element results showed that the shear strength increase with the increase in the shear connection contribution.

Using multiple push-out tests, Rambo-Roddenberry et al. [22] studied the influence of steel plate thickness and shear connector location. According to their research, the thickness of the steel plate has an effect on the strength of shear studs in unfavorable locations. The strength difference between favorable and unfavorable positions is approximately 30%. Furthermore, the shear connector’s tensile strength has a larger effect on the shear stud strength than the concrete’s compressive strength.

Qureshi et al. [23] used 3D finite element models to investigate the spacing and layout of shear connectors in composite beams. The results showed that when the transverse spacing between the studs is 200 mm or more, shear resistance of shear connector pairs positioned in favorable positions is 94% of the strength of a single shear stud on average. A staggered pair of studs only has 86% of the strength of a single stud with the same spacing. Staggered pairs of shear connections have less strength than double shear studs in a favorable position.

Hosseini et al. [24] investigated the behavior of composite beams with trapezoidal profiled sheeting laid transverse to the beam axis. Four parameters were investigated using experimental findings from 24 full-scaled push test specimens, one of which was the shear stud arrangement. When compared to a layout with studs in the first four ribs, using studs just in the middle three ribs improved strength by 23%. Eurocode 4 and Johnson and Yuan [25] equations accurately predicted the stud strength for single stud/rib tests without normal load, with estimations within 10% of the characteristic test load. These equations underestimated the stud capacity by 40–50% when tested under normal load. AISC 360-16 generally overestimated the stud capacity, with the exception of single stud/rib push tests under normal load [26].

In this research, due to the importance of the shear connectors in reducing or preventing the relative displacement between concrete and steel, non-linear finite element analysis until failure is conducted on 24 continuous 2-span composite beams to investigate the effect of the arrangement and the number of shear connectors on the overall behavior of composite beams.

2 Description of samples

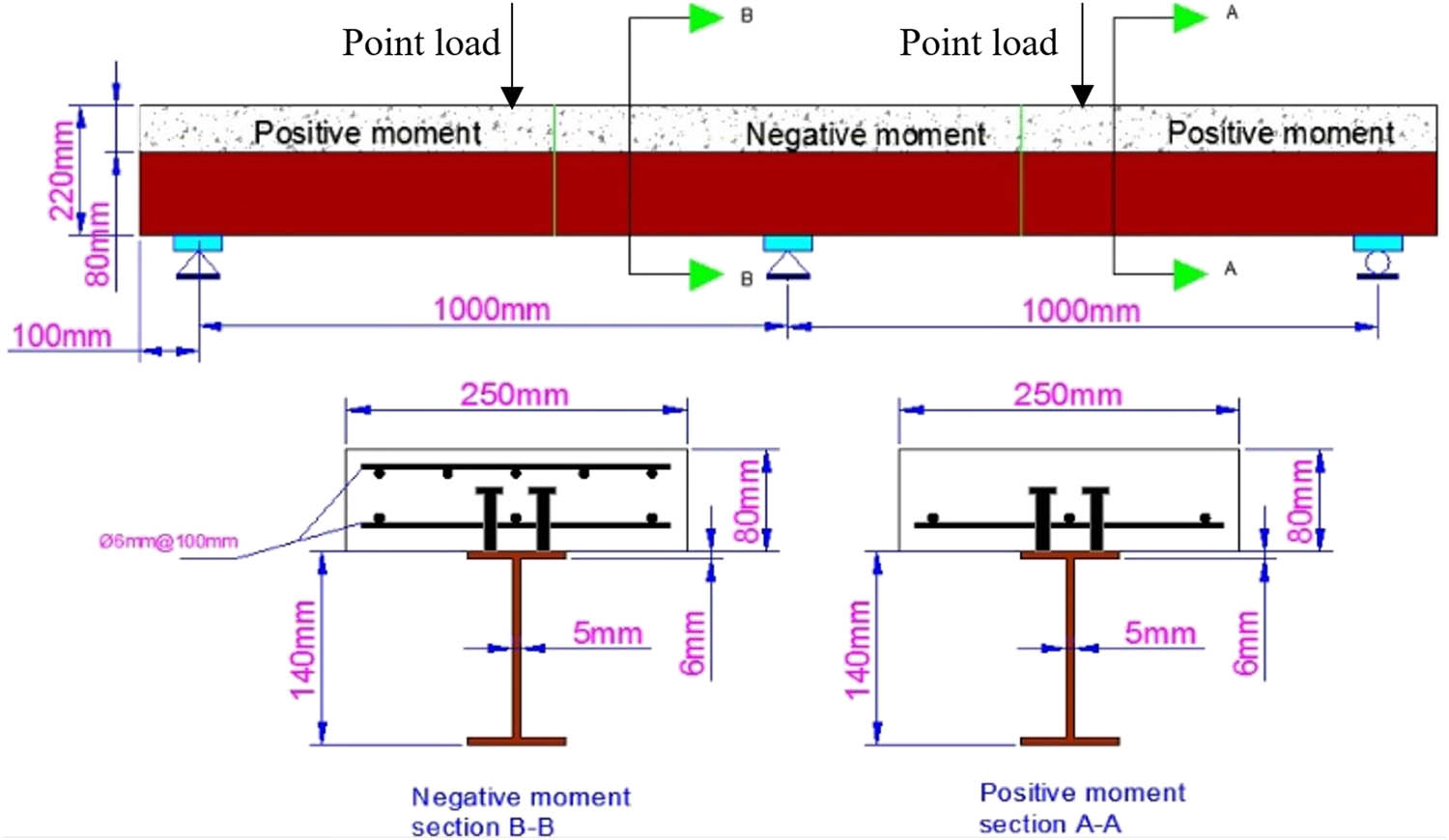

In this research, to study the effect of shear connectors, 3D nonlinear finite element analysis is conducted on 24 continuous 2-span composite beams with 2-point loads (one point load in each span). All beams have the same span details, length of 1 m for each span and the concrete slab was of width 250 mm and depth 8 mm. The steel I-section (IPE-140) had a depth of 140 mm, flange width of 72 mm, and thickness of 6 mm, while the web depth was 128 mm, thickness was 5 mm, and the total depth of the test samples was 220 mm as demonstrated in Figure 2.

Details of section specimens.

The strengthening of the concrete slab followed the criteria of the ACI construction code. Steel reinforcement in the longitudinal and transverse directions were based on shrinkage and temperature requirements [27,28]. Figure 2 demonstrates the negative and positive cross section of the beam.

The concrete slab was connected to a steel beam using the stud method. The shear connectors were assumed to be fully bonded to the I-steel beam’s top flange and embedded in the concrete slab. The length and diameter of all studs were the same, but the number of studs varied depending on the study parameters from one sample to another. The variable parameters of the current study were divided into four categories:

2.1 Group A

The first group consisted of 6 steel–concrete beams (BC1, BC2, BC3, BC4, BC5, and BC6) with shear connectors divided into 2 rows with different distances 65, 85, 105, 150, 200, and 250 mm, respectively, as shown in Figure 3.

Shear connectors distribution for Group A.

2.2 Group B

The second group consisted of 6 steel–concrete beams (BC7, BC8, BC9, BC10, BC11 and BC12) with 1 of row shear connectors distributed along the longitudinal axis with distances of 65, 85, 105, 150, 200, and 250 mm, respectively, as shown in Figure 4.

Shear connectors distribution for Group B.

2.3 Group C

The third group included 6 steel–concrete beams (BC13, BC14, BC15, BC16, BC17 and BC18) single- and double-shear connectors distributed along the longitudinal axis with different distances 65, 85, 105, 150, 200, and 250 mm, respectively, as shown in Figure 5.

Shear connectors distribution for Group C.

2.4 Group D

The fourth group included 6 steel–concrete beams (BC19, BC20, BC21, BC22, BC23 and BC24) with one row shear connectors arranged staggered along the longitudinal axis with different distances 65, 85, 105, 150, 200, and 250 mm, respectively, as shown in Figure 6. The properties of materials used is shown in Table 1.

Shear connectors distribution for Group D.

Properties of materials

| Steel reinforcement | Reactive powder concrete | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Modulus of elasticity (MPa) | 2 × 105 | Compressive strength (MPa) | 100.29 |

| Yield strength (MPa) | 520 | Modulus of elasticity (MPa) | 44.5 × 103 |

| Element type | T3D2 | Dilation angle | 40 |

| Element size (mm) | 20 | Eccentricity | 0.1 |

| I-section steel | fbo/fco | 1.16 | |

| Modulus of elasticity (MPa) | 2 × 105 | K | 0.667 |

| Yield strength (MPa) | 300 | Viscosity | 0 |

| Element type | C3D8R | Element type | C3D8R |

| Element size (mm) | 20 | Element size (mm) | 20 |

3 Numerical model validation

To ensure that the current model in the ABAQUS software is appropriate, two samples are chosen and compared to Aggar’s experimental results [29]. As demonstrated in Figure 7, the results of the experimental and the numerical model are in good agreement. Figure 8 shows the stress distribution in the experimental and numerical models of the sample (BC2).

Load–deflection curve of the experimental and numerical sample (BC2).

![Figure 8

Comparison between the experimental and numerical stress distribution at failure for the sample (BC2) [31].](/document/doi/10.1515/jmbm-2022-0046/asset/graphic/j_jmbm-2022-0046_fig_008.jpg)

Comparison between the experimental and numerical stress distribution at failure for the sample (BC2) [31].

4 Discussion and results

The results of analyzing the specimens with ABAQUS software demonstrate that the number of shear connections and their arrangement have an effect on the ultimate load failure for composite beams.

4.1 Group A

The results of the analysis indicate that changing the shear connection spacing from 65 to 85 mm and 105 mm increased the ultimate load capacity; however, increasing the spacing from 105 to 150, 200, and 250 mm decreased the ultimate load capacity, as shown in Table 2. Figure 9 shows the load and deflection for the specimens of group A.

Ultimate strength and deflection of midspan of group A

| Group no. | Specimen | Ultimate strength (kN) | Deflection (mm) | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | BC65 | 505.52 | 3.96 | — |

| BC85 | 582.33 | 4.77 | 15.19 | |

| BC105 | 609.37 | 6.41 | 20.54 | |

| BC150 | 508.78 | 5.18 | 0.64 | |

| BC200 | 501.47 | 5.85 | −0.80 | |

| BC250 | 483.95 | 6.42 | −4.27 |

Load–deflection for the specimens of Group A.

Figure 10 shows stress distribution for specimens of Group A.

Stress distribution for specimens of Group A.

4.2 Group B

The results of analysis of the second group also showed that the change in the spacing of shear connection from 65 to 85 and 105 mm led to an increase in the ultimate load capacity, while increasing the spacing from 105 to 150, 200, and 250 mm led to a decrease in the ultimate load capacity as shown in Table 3. Figure 11 shows the load and deflection for the specimens of Group B.

Ultimate strength and deflection of midspan of Group B

| Group no. | Specimen | Ultimate strength (kN) | Deflection (mm) | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | BC65 | 464.67 | 3.82 | — |

| BC85 | 505.21 | 4.99 | 8.85 | |

| BC105 | 520.75 | 5 | 12.20 | |

| BC150 | 473.13 | 5.3 | 1.94 | |

| BC200 | 455.16 | 6.54 | −1.93 | |

| BC250 | 435.22 | 8.24 | −6.23 |

Load–deflection for the specimens of Group B.

Figure 12 shows stress distribution for specimens of Group B.

Stress distribution for specimens of Group B.

4.3 Group C

The results of analysis of the third group showed that the shear connections with a spacing of 105 mm gave the highest ultimate load capacity than all the other spacings of the same group but with less difference percent than Group A and Group B, as shown in Table 4. Figure 13 shows the load and deflection curves of group C.

Ultimate strength and deflection of midspan of Group C

| Group no. | Specimen | Ultimate strength (kN) | Deflection (mm) | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | BC65 | 440.53 | 4.25 | — |

| BC85 | 450.23 | 4.57 | 2.20 | |

| BC105 | 460.67 | 4.38 | 4.57 | |

| BC150 | 442.09 | 5.01 | 0.35 | |

| BC200 | 440.4 | 6.4 | −0.03 | |

| BC250 | 420.19 | 6.81 | −4.62 |

Load–deflection for the specimens of Group C.

Figure 14 shows stress distribution for specimens of Group C.

Stress distribution for specimens of Group C.

4.4 Group D

The results of analysis of the fourth group showed that the shear connections with a spacing of 150 mm gave the highest ultimate load capacity than all the other spacings of the same group and the arrangement of shear connection led to the buckling in the flange of the steel I-section, Table 5 shows deflection and ultimate load for Group D. Figure 15 shows the load and deflection curves of Group D.

Ultimate strength and deflection of midspan of Group D

| Group no. | Specimen | Ultimate strength (kN) | Deflection (mm) | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| D | BC65 | 386.64 | 3.71 | — |

| BC85 | 392.97 | 4.74 | 1.64 | |

| BC105 | 410.53 | 3.12 | 6.18 | |

| BC150 | 415.2 | 16.65 | 7.39 | |

| BC200 | 410.06 | 11.19 | 6.06 | |

| BC250 | 365.2 | 13.75 | −5.55 |

Load–deflection for the specimens of Group D.

Figure 16 shows stress distribution for Group D.

Stress distribution for Group D.

As shown in Figure 17, it can be noticed that the effect of changing the spacing of shear connectors for Group A is more effective than the other groups.

The curve of ultimate load–deflection for all groups.

5 Conclusion

This study presented a numerical investigation of composite steel–concrete members using ABAQUS software, and the outcomes of this study were as follows:

The composite steel concrete beam with 2 symmetrical shear stud rows has higher bending strength capacity by 17, 32, and 48% compared with the groups B, C, and D, respectively.

For the fourth group (D), the deflection was fluctuating up and down, which resulted from nonsymmetrical distribution of the shear connectors. And this case was considered the worst condition compared with the symmetrical distribution.

The optimum spacing was 105 mm in all groups (A, B, C, and D) compared with all other spacings of 65, 85, 200, and 250 mm.

When comparing the optimum spacing of shear connector (105 mm) with other spacings such as 150, 200, and 250 mm, the bending strength capacity of the composite beam was reduced by 20, 20, and 26%, respectively.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to Al-Mustaqbal University college, Babylon, Iraq for their contribution in completing this work.

-

Funding information: The authors state no funding involved.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

References

[1] Shubbar A, Nasr M, Falah M, Al-Khafaji Z. Towards net zero carbon economy: Improving the sustainability of existing industrial infrastructures in the UK. Energies. 2021;14(18):5896.10.3390/en14185896Search in Google Scholar

[2] Falah MW, Hafedh AA, Hussein SA, Al-Khafaji ZS, Shubbar AA, Nasr MS. The combined effect of CKD and silica fume on the mechanical and durability performance of cement mortar. Key Eng Mater. 2021;895:59–67.10.4028/www.scientific.net/KEM.895.59Search in Google Scholar

[3] Shubbar A, Al-khafaji Z, Nasr M, Falah M. Using non-destructive tests for evaluating flyover footbridge: case study. Knowl Eng Sci. 2020;1(1):23–39.10.51526/kbes.2020.1.01.23-39Search in Google Scholar

[4] Al-Khafaji ZS, Falah MW. Applications of high density concrete in preventing the impact of radiation on human health. J Adv Res Dyn Control Syst. 2020;12(1):105961.10.5373/JARDCS/V12SP1/20201115Search in Google Scholar

[5] Ellobody E. Finite element analysis and design of steel and steel–concrete composite bridges. Oxford, UK: Butterworth-Heinemann; 2014.10.1016/B978-0-12-417247-0.00005-3Search in Google Scholar

[6] Mazoz A, Benanane A, Titoum M. Push-out tests on a new shear connector of I-shape. Int J Steel Struct. 2013;13(3):519–28.10.1007/s13296-013-3011-4Search in Google Scholar

[7] Zeng X, Jiang SF, Zhou D. Effect of shear connector layout on the behavior of steel-concrete composite beams with interface slip. Appl Sci. 2019;9(1):207.10.3390/app9010207Search in Google Scholar

[8] Zona A, Ranzi G. Finite element models for nonlinear analysis of steel–concrete composite beams with partial interaction in combined bending and shear. Finite Elem Anal Des. 2011;47(2):98–118.10.1016/j.finel.2010.09.006Search in Google Scholar

[9] Esfandiari J, Latifi MK. Numerical study of progressive collapse in reinforced concrete frames with FRP under column removal. Adv Concr Constr. 2019;8(3):165–72.Search in Google Scholar

[10] Esfandiari J, Soleimani E. Laboratory investigation on the buckling restrained braces with an optimal percentage of microstructure, polypropylene and hybrid fibers under cyclic loads. Composite Struct. 2018;203:585–98.10.1016/j.compstruct.2018.07.035Search in Google Scholar

[11] Esfandiari S, Esfandiari J. Simulation of the behaviour of RC columns strengthen with CFRP under rapid loading. Adv Concr Constr. 2016;4(4):319–32.10.12989/acc.2016.4.4.319Search in Google Scholar

[12] Ali YA, Hashim TM, Ali AH. Finite element analysis for the behavior of reinforced concrete T-section deep beams strengthened with CFRP sheets. Key Eng Mater. 2020;857:153–61. 10.4028/www.scientific.net/KEM.857.153Search in Google Scholar

[13] Agioutantis Z, Kourkoulis SK, Maurigiannakis S, Papatheodorou E. Notched marble specimens under bending: experimental study and numerical analysis using an elastoplastic model with contact elements. J Mech Behav Mater. 2005;16(1–2):1–8.10.1515/JMBM.2005.16.1-2.1Search in Google Scholar

[14] Yang J, Zhou J, Wang Z, Zhou Y, Zhang H. Structural behavior of ultrahigh-performance fiber-reinforced concrete thin-walled arch subjected to asymmetric load. Adv Civ Eng. 2019;2019:2019-12.10.1155/2019/9276839Search in Google Scholar

[15] Zona A, Leoni G, Dall’Asta A. Influence of shear connection distributions on the behaviour of continuous steel-concrete composite beams. Open Civ Eng J. 2017;11(1):384–95.10.2174/1874149501711010384Search in Google Scholar

[16] Zhai C, Lu B, Wen W, Ji D, Xie L. Experimental study on shear behavior of studs under monotonic and cyclic loadings. J Constr Steel Res. 2018;151:1–11.10.1016/j.jcsr.2018.07.029Search in Google Scholar

[17] Lam D, El-Lobody E. Finite element modelling of headed stud shear connectors in steel-concrete composite beam. Structural engineering, mechanics and computation. Cape Town, South Africa: Elsevier Science; 2001. p. 401–8.10.1016/B978-008043948-8/50041-2Search in Google Scholar

[18] Pathirana SW, Uy B, Mirza O, Zhu X. Flexural behaviour of composite steel–concrete beams utilising blind bolt shear connectors. Eng Struct. 2016;114:181–94.10.1016/j.engstruct.2016.01.057Search in Google Scholar

[19] Liang QQ, Uy B, Bradford MA, Ronagh HR. Strength analysis of steel–concrete composite beams in combined bending and shear. J Struct Eng. 2005;131(10):1593–600.10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9445(2005)131:10(1593)Search in Google Scholar

[20] Reginato LH, Tamayo JL, Morsch IB. Finite element study of effective width in steel-concrete composite beams under long-term service loads. Lat Am J Solids Struct. 2018;15:15.10.1590/1679-78254599Search in Google Scholar

[21] Al-Khafaji ZS, Majdi A, Shubbar AA, Nasr MS, Al-Mamoori SF, Alkhulaifi A, et al. Impact of high volume GGBS replacement and steel bar length on flexural behaviour of reinforced concrete beams. IOP Conf Ser: Mater Sci Eng. 2021;1090:012015.10.1088/1757-899X/1090/1/012015Search in Google Scholar

[22] Rambo-Roddenberry M, Lyons JC, Easterling WS, Murray TM. Performance and strength of welded shear studs. Composite Constr Steel Concr IV. 2002;458–69.10.1061/40616(281)40Search in Google Scholar

[23] Qureshi J, Lam D, Ye J. Effect of shear connector spacing and layout on the shear connector capacity in composite beams. J Constr Steel Res. 2011;67(4):706–19.10.1016/j.jcsr.2010.11.009Search in Google Scholar

[24] Hosseini SM, Mamun MS, Mirza O, Mashiri F. Behaviour of blind bolt shear connectors subjected to static and fatigue loading. Eng Struct. 2020;214:110584.10.1016/j.engstruct.2020.110584Search in Google Scholar

[25] Johnson RP, Yuan H. Models and design rules for stud shear connectors in troughs of profiled sheeting. Proc Inst Civ Eng-Struct Build. 1998;128(3):252–63.10.1680/istbu.1998.30459Search in Google Scholar

[26] Marshdi QSR, Hussien SA, Mareai BM, Al-Khafaji ZS, Shubbar AA. Applying of No-fines concretes as a porous concrete in different construction application. Periodicals Eng Nat Sci. 2021;9(4):999–1012.10.21533/pen.v9i4.2476Search in Google Scholar

[27] ACI Committee. Building code requirements for structural concrete (ACI 318-08) and commentary. American Concrete Institute; 2008.Search in Google Scholar

[28] Standardization EC for Eurocode 4. Design of composite steel and concrete structures – Part 1-1: General rules and rules for buildings – EN 1994-1-1; 2004.Search in Google Scholar

[29] Aggar R. Structural behaviour of continuous steel-reactive powder concrete composite beams under repeated loads [dissertation]. Al-Hilla: Babylon University; 2018. p. 174.Search in Google Scholar

© 2022 Yasar Ameer Ali et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Calcium carbonate nanoparticles of quail’s egg shells: Synthesis and characterizations

- Effect of welding consumables on shielded metal arc welded ultra high hard armour steel joints

- Stress-strain characteristics and service life of conventional and asphaltic underlayment track under heavy load Babaranjang trains traffic

- Corrigendum to: Statistical mechanics of cell decision-making: the cell migration force distribution

- Prediction of bearing capacity of driven piles for Basrah governatore using SPT and MATLAB

- Investigation on microstructural features and tensile shear fracture properties of resistance spot welded advanced high strength dual phase steel sheets in lap joint configuration for automotive frame applications

- Experimental and numerical investigation of drop weight impact of aramid and UHMWPE reinforced epoxy

- An experimental study and finite element analysis of the parametric of circular honeycomb core

- The study of the particle size effect on the physical properties of TiO2/cellulose acetate composite films

- Hybrid material performance assessment for rocket propulsion

- Design of ER damper for recoil length minimization: A case study on gun recoil system

- Forecasting technical performance and cost estimation of designed rim wheels based on variations of geometrical parameters

- Enhancing the machinability of SKD61 die steel in power-mixed EDM process with TGRA-based multi criteria decision making

- Effect of boron carbide reinforcement on properties of stainless-steel metal matrix composite for nuclear applications

- Energy absorption behaviors of designed metallic square tubes under axial loading: Experiment-based benchmarking and finite element calculation

- Synthesis and study of magnesium complexes derived from polyacrylate and polyvinyl alcohol and their applications as superabsorbent polymers

- Artificial neural network for predicting the mechanical performance of additive manufacturing thermoset carbon fiber composite materials

- Shock and impact reliability of electronic assemblies with perimeter vs full array layouts: A numerical comparative study

- Influences of pre-bending load and corrosion degree of reinforcement on the loading capacity of concrete beams

- Assessment of ballistic impact damage on aluminum and magnesium alloys against high velocity bullets by dynamic FE simulations

- On the applicability of Cu–17Zn–7Al–0.3Ni shape memory alloy particles as reinforcement in aluminium-based composites: Structural and mechanical behaviour considerations

- Mechanical properties of laminated bamboo composite as a sustainable green material for fishing vessel: Correlation of layer configuration in various mechanical tests

- Singularities at interface corners of piezoelectric-brass unimorphs

- Evaluation of the wettability of prepared anti-wetting nanocoating on different construction surfaces

- Review Article

- An overview of cold spray coating in additive manufacturing, component repairing and other engineering applications

- Special Issue: Sustainability and Development in Civil Engineering - Part I

- Risk assessment process for the Iraqi petroleum sector

- Evaluation of a fire safety risk prediction model for an existing building

- The slenderness ratio effect on the response of closed-end pipe piles in liquefied and non-liquefied soil layers under coupled static-seismic loading

- Experimental and numerical study of the bulb's location effect on the behavior of under-reamed pile in expansive soil

- Procurement challenges analysis of Iraqi construction projects

- Deformability of non-prismatic prestressed concrete beams with multiple openings of different configurations

- Response of composite steel-concrete cellular beams of different concrete deck types under harmonic loads

- The effect of using different fibres on the impact-resistance of slurry infiltrated fibrous concrete (SIFCON)

- Effect of microbial-induced calcite precipitation (MICP) on the strength of soil contaminated with lead nitrate

- The effect of using polyolefin fiber on some properties of slurry-infiltrated fibrous concrete

- Typical strength of asphalt mixtures compacted by gyratory compactor

- Modeling and simulation sedimentation process using finite difference method

- Residual strength and strengthening capacity of reinforced concrete columns subjected to fire exposure by numerical analysis

- Effect of magnetization of saline irrigation water of Almasab Alam on some physical properties of soil

- Behavior of reactive powder concrete containing recycled glass powder reinforced by steel fiber

- Reducing settlement of soft clay using different grouting materials

- Sustainability in the design of liquefied petroleum gas systems used in buildings

- Utilization of serial tendering to reduce the value project

- Time and finance optimization model for multiple construction projects using genetic algorithm

- Identification of the main causes of risks in engineering procurement construction projects

- Identifying the selection criteria of design consultant for Iraqi construction projects

- Calibration and analysis of the potable water network in the Al-Yarmouk region employing WaterGEMS and GIS

- Enhancing gypseous soil behavior using casein from milk wastes

- Structural behavior of tree-like steel columns subjected to combined axial and lateral loads

- Prospect of using geotextile reinforcement within flexible pavement layers to reduce the effects of rutting in the middle and southern parts of Iraq

- Ultimate bearing capacity of eccentrically loaded square footing over geogrid-reinforced cohesive soil

- Influence of water-absorbent polymer balls on the structural performance of reinforced concrete beam: An experimental investigation

- A spherical fuzzy AHP model for contractor assessment during project life cycle

- Performance of reinforced concrete non-prismatic beams having multiple openings configurations

- Finite element analysis of the soil and foundations of the Al-Kufa Mosque

- Flexural behavior of concrete beams with horizontal and vertical openings reinforced by glass-fiber-reinforced polymer (GFRP) bars

- Studying the effect of shear stud distribution on the behavior of steel–reactive powder concrete composite beams using ABAQUS software

- The behavior of piled rafts in soft clay: Numerical investigation

- The impact of evaluation and qualification criteria on Iraqi electromechanical power plants in construction contracts

- Performance of concrete thrust block at several burial conditions under the influence of thrust forces generated in the water distribution networks

- Geotechnical characterization of sustainable geopolymer improved soil

- Effect of the covariance matrix type on the CPT based soil stratification utilizing the Gaussian mixture model

- Impact of eccentricity and depth-to-breadth ratio on the behavior of skirt foundation rested on dry gypseous soil

- Concrete strength development by using magnetized water in normal and self-compacted concrete

- The effect of dosage nanosilica and the particle size of porcelanite aggregate concrete on mechanical and microstructure properties

- Comparison of time extension provisions between the Joint Contracts Tribunal and Iraqi Standard Bidding Document

- Numerical modeling of single closed and open-ended pipe pile embedded in dry soil layers under coupled static and dynamic loadings

- Mechanical properties of sustainable reactive powder concrete made with low cement content and high amount of fly ash and silica fume

- Deformation of unsaturated collapsible soils under suction control

- Mitigation of collapse characteristics of gypseous soils by activated carbon, sodium metasilicate, and cement dust: An experimental study

- Behavior of group piles under combined loadings after improvement of liquefiable soil with nanomaterials

- Using papyrus fiber ash as a sustainable filler modifier in preparing low moisture sensitivity HMA mixtures

- Study of some properties of colored geopolymer concrete consisting of slag

- GIS implementation and statistical analysis for significant characteristics of Kirkuk soil

- Improving the flexural behavior of RC beams strengthening by near-surface mounting

- The effect of materials and curing system on the behavior of self-compacting geopolymer concrete

- The temporal rhythm of scenes and the safety in educational space

- Numerical simulation to the effect of applying rationing system on the stability of the Earth canal: Birmana canal in Iraq as a case study

- Assessing the vibration response of foundation embedment in gypseous soil

- Analysis of concrete beams reinforced by GFRP bars with varying parameters

- One dimensional normal consolidation line equation

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Calcium carbonate nanoparticles of quail’s egg shells: Synthesis and characterizations

- Effect of welding consumables on shielded metal arc welded ultra high hard armour steel joints

- Stress-strain characteristics and service life of conventional and asphaltic underlayment track under heavy load Babaranjang trains traffic

- Corrigendum to: Statistical mechanics of cell decision-making: the cell migration force distribution

- Prediction of bearing capacity of driven piles for Basrah governatore using SPT and MATLAB

- Investigation on microstructural features and tensile shear fracture properties of resistance spot welded advanced high strength dual phase steel sheets in lap joint configuration for automotive frame applications

- Experimental and numerical investigation of drop weight impact of aramid and UHMWPE reinforced epoxy

- An experimental study and finite element analysis of the parametric of circular honeycomb core

- The study of the particle size effect on the physical properties of TiO2/cellulose acetate composite films

- Hybrid material performance assessment for rocket propulsion

- Design of ER damper for recoil length minimization: A case study on gun recoil system

- Forecasting technical performance and cost estimation of designed rim wheels based on variations of geometrical parameters

- Enhancing the machinability of SKD61 die steel in power-mixed EDM process with TGRA-based multi criteria decision making

- Effect of boron carbide reinforcement on properties of stainless-steel metal matrix composite for nuclear applications

- Energy absorption behaviors of designed metallic square tubes under axial loading: Experiment-based benchmarking and finite element calculation

- Synthesis and study of magnesium complexes derived from polyacrylate and polyvinyl alcohol and their applications as superabsorbent polymers

- Artificial neural network for predicting the mechanical performance of additive manufacturing thermoset carbon fiber composite materials

- Shock and impact reliability of electronic assemblies with perimeter vs full array layouts: A numerical comparative study

- Influences of pre-bending load and corrosion degree of reinforcement on the loading capacity of concrete beams

- Assessment of ballistic impact damage on aluminum and magnesium alloys against high velocity bullets by dynamic FE simulations

- On the applicability of Cu–17Zn–7Al–0.3Ni shape memory alloy particles as reinforcement in aluminium-based composites: Structural and mechanical behaviour considerations

- Mechanical properties of laminated bamboo composite as a sustainable green material for fishing vessel: Correlation of layer configuration in various mechanical tests

- Singularities at interface corners of piezoelectric-brass unimorphs

- Evaluation of the wettability of prepared anti-wetting nanocoating on different construction surfaces

- Review Article

- An overview of cold spray coating in additive manufacturing, component repairing and other engineering applications

- Special Issue: Sustainability and Development in Civil Engineering - Part I

- Risk assessment process for the Iraqi petroleum sector

- Evaluation of a fire safety risk prediction model for an existing building

- The slenderness ratio effect on the response of closed-end pipe piles in liquefied and non-liquefied soil layers under coupled static-seismic loading

- Experimental and numerical study of the bulb's location effect on the behavior of under-reamed pile in expansive soil

- Procurement challenges analysis of Iraqi construction projects

- Deformability of non-prismatic prestressed concrete beams with multiple openings of different configurations

- Response of composite steel-concrete cellular beams of different concrete deck types under harmonic loads

- The effect of using different fibres on the impact-resistance of slurry infiltrated fibrous concrete (SIFCON)

- Effect of microbial-induced calcite precipitation (MICP) on the strength of soil contaminated with lead nitrate

- The effect of using polyolefin fiber on some properties of slurry-infiltrated fibrous concrete

- Typical strength of asphalt mixtures compacted by gyratory compactor

- Modeling and simulation sedimentation process using finite difference method

- Residual strength and strengthening capacity of reinforced concrete columns subjected to fire exposure by numerical analysis

- Effect of magnetization of saline irrigation water of Almasab Alam on some physical properties of soil

- Behavior of reactive powder concrete containing recycled glass powder reinforced by steel fiber

- Reducing settlement of soft clay using different grouting materials

- Sustainability in the design of liquefied petroleum gas systems used in buildings

- Utilization of serial tendering to reduce the value project

- Time and finance optimization model for multiple construction projects using genetic algorithm

- Identification of the main causes of risks in engineering procurement construction projects

- Identifying the selection criteria of design consultant for Iraqi construction projects

- Calibration and analysis of the potable water network in the Al-Yarmouk region employing WaterGEMS and GIS

- Enhancing gypseous soil behavior using casein from milk wastes

- Structural behavior of tree-like steel columns subjected to combined axial and lateral loads

- Prospect of using geotextile reinforcement within flexible pavement layers to reduce the effects of rutting in the middle and southern parts of Iraq

- Ultimate bearing capacity of eccentrically loaded square footing over geogrid-reinforced cohesive soil

- Influence of water-absorbent polymer balls on the structural performance of reinforced concrete beam: An experimental investigation

- A spherical fuzzy AHP model for contractor assessment during project life cycle

- Performance of reinforced concrete non-prismatic beams having multiple openings configurations

- Finite element analysis of the soil and foundations of the Al-Kufa Mosque

- Flexural behavior of concrete beams with horizontal and vertical openings reinforced by glass-fiber-reinforced polymer (GFRP) bars

- Studying the effect of shear stud distribution on the behavior of steel–reactive powder concrete composite beams using ABAQUS software

- The behavior of piled rafts in soft clay: Numerical investigation

- The impact of evaluation and qualification criteria on Iraqi electromechanical power plants in construction contracts

- Performance of concrete thrust block at several burial conditions under the influence of thrust forces generated in the water distribution networks

- Geotechnical characterization of sustainable geopolymer improved soil

- Effect of the covariance matrix type on the CPT based soil stratification utilizing the Gaussian mixture model

- Impact of eccentricity and depth-to-breadth ratio on the behavior of skirt foundation rested on dry gypseous soil

- Concrete strength development by using magnetized water in normal and self-compacted concrete

- The effect of dosage nanosilica and the particle size of porcelanite aggregate concrete on mechanical and microstructure properties

- Comparison of time extension provisions between the Joint Contracts Tribunal and Iraqi Standard Bidding Document

- Numerical modeling of single closed and open-ended pipe pile embedded in dry soil layers under coupled static and dynamic loadings

- Mechanical properties of sustainable reactive powder concrete made with low cement content and high amount of fly ash and silica fume

- Deformation of unsaturated collapsible soils under suction control

- Mitigation of collapse characteristics of gypseous soils by activated carbon, sodium metasilicate, and cement dust: An experimental study

- Behavior of group piles under combined loadings after improvement of liquefiable soil with nanomaterials

- Using papyrus fiber ash as a sustainable filler modifier in preparing low moisture sensitivity HMA mixtures

- Study of some properties of colored geopolymer concrete consisting of slag

- GIS implementation and statistical analysis for significant characteristics of Kirkuk soil

- Improving the flexural behavior of RC beams strengthening by near-surface mounting

- The effect of materials and curing system on the behavior of self-compacting geopolymer concrete

- The temporal rhythm of scenes and the safety in educational space

- Numerical simulation to the effect of applying rationing system on the stability of the Earth canal: Birmana canal in Iraq as a case study

- Assessing the vibration response of foundation embedment in gypseous soil

- Analysis of concrete beams reinforced by GFRP bars with varying parameters

- One dimensional normal consolidation line equation