Abstract

The shape of the projectile seems to determine the effect of a ballistic impact and failure mechanism. In this study, the numerical analysis of ballistic impact with different projectile shapes, i.e., ogive, blunt, conical, and hemispherical is performed. The target is a circular sandwich plate with an outer diameter of 315 mm, which is composed of three layers with a thickness of 1 mm for each layer. These layers will be filled with different materials such as 1100-H12 aluminum alloy, ZK61m magnesium alloy, and 6061-T651 aluminum alloy. The target plate in the numerical analysis consists of two parts: the inner and outer zones. In the inner zone, the selected element size is set to fine, while in the outer zone, it is set to be coarser, and the size will increase along with the direction and the diameter of the circle. This numerical simulation uses the Johnson–Cook material model and is applied to ABAQUS/Explicit software. The simulation configurations are validated based on previous experiments by comparing the residual velocity values after the projectile has penetrated the target plate. The simulation results will obtain energy absorption values for each variation of the target plate. The energy absorption values are affected by stress and strain in radial, circumferential, axial, and shear deformation. The energy absorption value determines the strength of each variation of the target plate. Then the target plate will compare which arrangement is the strongest when receiving ballistic loads.

Graphical abstract

1 Introduction

Metal plates are broadly utilized as a defensive layer in construction like aluminum and magnesium. The defensive plate is put on the outer side to forestall loads, e.g., sway from projectiles or blasts. The degree of obstruction of the boat divider relies upon the state of the constituent construction.

The lightweight sandwich boards can supplant the traditional hardened plate structures in the boat building, decreasing weight by eliminating the requirement for a long time [1]. Sandwich constructions can be set upshifting the material or shape. Yet, most are recognized on the center design, isolated into four sorts: froth or strong, honeycomb, web, and corrugated [2]. The penetration mechanism depends on the properties of the projectile and the target material, the speed of impact, the shape of the nose of the projectile, the boundary conditions of the target, the relative dimensions of the projectile and target, etc. [3]. Hence, it is unreasonable and ideal for the principal arrangement of effect-related issues on test tests alone [4]. Subsequently, it is essential to do a mathematical test to ensure that the state of the shot and the objective limit conditions are no longer deterrents in this review. Sandwich boards are typically applied to high-speed impacts. Consequently, it is critical to concentrate on their way of behaving under sway stacking. The rapid effect reaction relies upon the thickness of the material, where the construction cannot answer stacks rapidly, causing nearby harm.

A few examinations on ballistic effect have been completed in tests due to the complexity of the constraints in the review. Experimental, numerical, and analytical methods were carried out to study the ballistic impact, for which an experimental approach was more reliable than other methods. Thus, most announced examinations depend on practical strategies. Trailblazer studies explored by Thomson [5], Calder and Goldsmith [6], Shadbolt et al. [7], Neilson [8], Landkof and Goldsmith [9], Wen and Jones [10], Liu and Stronge [11], Gupta et al. [12], and Khan et al. [13] introduced different insightful, exact, test and mathematical examinations on the effective conduct of focuses with regard to energy retention scattering in the created distortion mode. Iqbal et al. [14], Tiwari et al. [15], and Mohammad et al. [16] introduced different mathematical tests and investigation strategies for the complete energy retention in various nearby and worldwide disfigurement modes and utilizing different shot shapes. Previous research on ballistic impact was also conducted by Mohammad et al. [16] to determine the effect when hitting a 2 mm monolithic target plate and in-contact double-layered target plate with equivalent thickness using 1100-H12 aluminum material. The projectile shapes used are ogive, blunt, conical, and hemispherical. Another study on ballistic impact has been carried out by Deng et al. [17] to reveal the strength of 6061-T651 aluminum alloy thick plates against blunt-nosed projectile. The numerical simulation is based on the new fracture criterion, namely, the WMJC criterion. The WMJC is a combination of the W–M fracture criterion [18] and the J–C fracture criterion [19]. Regardless of this, the study analysis on the projectile shapes used by Mohammad et al. [16] has not studied the effect on three layered sandwich plates with materials such as aluminum alloy 1100-H12, magnesium alloy ZK61m and aluminum alloy 6061-T651 has not been carried out. The effect of the implementation of the Johnson–Cook material model with these parameter configurations on the ballistic impact failure mechanism has not yet known.

In this study, the numerical analysis of ballistic impact with different projectile shapes i.e., ogive, blunt, conical, and hemispherical, is performed. The target is a circular sandwich plate composed of three layers of different materials such as 1100-H12 aluminum alloy, ZK61m magnesium alloy, and 6061-T651 aluminum alloy. This numerical simulation uses the Johnson–Cook material model and is applied to ABAQUS/Explicit software. The simulation configurations are validated based on previous experiments by comparing the residual velocity values after the projectile has penetrated the target plate. The simulation results will obtain energy absorption values for each variation of the target plate. The strongest target plate arrangement will be indicated by the ability to absorb energy from projectiles.

2 Literature review

This impact ballistic phenomenon is important to analyze because there are many cases of ship hijacking, such as the Maersk case in Alabama that has happened before. Cargo ship in its design does not prioritize the value of security because it is more important to be able to accommodate many containers in shipping to reduce transportation costs. The pirates will be more profitable to carry out piracy on cargo ships because the goods carried can certainly be valuable to the pirates. In the case of piracy, of course, the ship’s crew will take preventive steps to prevent a shootout with the pirates. Therefore, using a strong ship wall structure can protect the crew and prevent the ship from leaking.

2.1 Explicit dynamic simulation

Explicit dynamic simulation analysis refers to the application of explicit integration rules along with the use of the mass matrix of diagonal (“lumped”) elements. The equations of motion for the body are integrated using the explicit integration rules [20] shown in Eq. (1).

where

The explicit integration rule is fairly simple, but the explicit dynamics procedure does not provide good computational efficiency. The use of mass matrix of the diagonal elements can be used as a computational efficiency solution of the explicit procedure because the acceleration at the start of the increment is calculated by

where M NJ is the mass matrix, P J is the applied load vector, and I J is the internal force vector; the combined mass matrix is used because the inverse is simple to calculate and because the vector product of the reciprocal of mass by the inertial force requires only n operations, where n is the number of degrees of freedom in the model.

2.2 Impact ballistic limit

The ballistic impact is a study that analyzes material damage caused by the impact of projectiles/bullets. It is applied as a form of protection in military applications. The impact behavior of the sandwich depends on the size, shape, mass, speed of impact, and material of the projectile.

The speed of the bullet after hitting the plate will decrease. So, the value of residual velocity (V r ) becomes important to evaluate and analyze the ballistic impact. In conducting ballistic impact experiments, the velocity after the projectile penetrates the target plate will be known. Some studies also use the value of the residual velocity. When analyzing the effect of the target plate on the ballistic impact, the classic Lambert–Jonas ballistic limit equation [21] is used to deal with the relationship between the initial velocity and the residual velocity of the projectile object. The Lambert–Jonas equation is given as follows:

where

Plastic deformation of the projectile can be neglected because the strength of the projectile is greater than that of the target plate, and the projectile can be considered as a rigid body. Therefore, the form of deformation, damage, and destruction of the target plate is the result of the kinetic energy absorbed by the target plate

where

where

2.3 Failure mechanism

Failure of the target plate during the collision process will result in deformation that affects the ability to absorb energy. To determine the impact of the target and the cause of the failure mechanism upon impact, the determination of energy dissipation in various failure modes is very prominent. And then, the target plate will absorb the projectile’s kinetic energy; there will be stress, strain, and deformation of the projectile. In this simulation, energy absorption in the projectile was neglected due to minor deformation. At the same time, the value of the plastic strain energy on the target plate is obtained from the calculation of the stress and plastic strain during the perforation process. The value and direction of the stress–strain for each element in the normal and tangential directions (Figure 1) and the energy absorption value are obtained by adding all components of stress and strain.

Element deformation: (a) stress and (b) plastic strain.

Stress values are separated by direction. The resulting value of stress can use von Mises stress to compare the various models. von Mises stress is obtained from the analysis process using ABAQUS/CAE software. The plastic deformation behavior is described by a Johnson–Cook model [19]

where

In order to reduce the dependence of the mesh in the evolution of the damage, the deformation after failure initiation is defined as the equivalent plastic displacement,

where

2.4 Energy absorption

The energy absorption value is obtained by adding the stress and plastic strain values for all directions during the collision process. The calculation only focuses on the target plate because the projectile is considered a rigid body so that it does not deform; the projectile in the experiment experienced a deformation that was not too significant. The calculation of energy absorption value using Eqs. (9)–(13) obtained from [16]:

where

2.5 State of the art

Research on ballistic impact has been done before. The research in Table 1 shows that many research subjects were carried out on different targets. Goda and Girardot [22] conducted research on ceramics and Kevlar-29 composites with a honeycomb core shape using a cylindrical blunt shape projectile. The numerical results reveal that the ballistic impact performance is highly dependent on the properties of the cohesive material, the stacking order, and the woven fabric material. In contrast, the smaller contribution of the supporting conditions to the characteristics of the ballistic perforation is taken into account. Rahimijonoush and Bayat [2] have researched the marine field by analyzing the performance of titanium sandwich panels against impact loads from hemispherical projectiles. The results show the impact energy is mainly absorbed by the rear face sheet in the symmetrical sandwich panels. The ballistic limit increases almost linearly with increasing thickness of the rear or front face sheet on a specimen of the same weight. Research in the field of aeronautics conducted by Chatterjee et al. [23] analyzed the performance of a composite sandwich panel against a projectile load of 9 mm bullets with an average velocity of 400 m/s. It is observed that due to the incorporation of dilatant liquid within SCP, it can absorb 20.24% of the energy incident on it. The amount of energy absorbed is 43.96% greater than that absorbed by the hollow composite, and the percentage increase in energy absorbed per unit mass increase is 22.43%. This enables the constructed SCP to be used in applications requiring enhanced energy dissipation. Yu et al. [24] conducted research in the marine field with a target Y-shaped core sandwich using a blunt shape projectile. The conclusion of this study is that the impact resistance of a composite sandwich structure with a Y-shaped core is superior to that of laminate.

previous numerical research on ballistic impact

| Type | Author | Subject | Target | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-metal | Chatterjee et al. [23] | Aeronautic | Sandwich composite panels | A new type of sandwich composite panel is made consisting of a fused-double-3D-mat composite which can offer an increased rate of energy dissipation against ballistic impacts at an average speed of 400 m/s |

| Vescovini et al. [28] | Composite structures | Interply hybridcomposites of woven Kevlar and S2-glass | The deviation at the ballistic limit is always lower than 5.33% and has a maximum of 3.87% at 430 m/s impact velocity, close to the ballistic limit. Also, although the numerical ballistic curves show a generally smoother transition to the linear part, it closely matches the experimental ones | |

| Goda and Girardot [22] | Armor | Ceramic and Kevlar-29 composite | Impact velocities of 300 and 400 m/s, it was found that while perforating the target at short times of about t = 31 μs and 20 μs, the projectile velocities become stable, i.e., 173 and 273 m/s, respectively | |

| Yang et al. [27] | Shipbuilding | Composite double-arrow auxetic structure | The METC of the auxetic structures with the relative density of 16.66 and 23.06% is greater than that of the auxetic structure with the relative density of 9.08%. The ballistic limit velocity increases by 35.56 and 54.89% as the relative density increases from 9.08 to 16.66 and 23.06% | |

| Wu et al. [26] | Composite armor system | Aramid–carbon hybrid FRP laminate composite structures | The main failure modes of the FRP laminate are the fiber compression failure and the matrix tensile failure, both of which can also be influenced by the change of the stacking sequence of the FRP laminate. When the carbon fiber is stacked at the top of the FRP laminate, both of the fiber compression failure area andthe matrix tensile failure area is the lowest | |

| Metal | Rahimijonoush and Bayat [2] | Marine | Titanium sandwich panels | The numerical results show that increasing cell per wall thickness is more effective at ballistic and energy absorption limits than increasing core thickness |

| Mohammad et al. [16] | Military equipment | Monolithic and double-layered thin-metallic hemispherical shells | In case of targets impacted with conical nosed projectiles, the ballistic performance of monolithic shell targets decreased by 6.49%, whereas layered targets showed 3.88% reduction in impact resisting capacity at oblique impacts | |

| Yu et al. [24] | Marine | Y-shaped cores sandwich | A composite sandwich structure with a Y-shaped core has better impact resistance and energy absorption capacity than a laminated structure of the same area | |

| Khaire et al. [25] | Naval industries | Honeycomb core cylindrical sandwich | The transverse deflection of the hind forewings is highest, followed by the forelimbs and the same core. In addition, the geometric parameters have a great influence on the transverse deflection. The transverse deflection of the rear surface decreases with increasing cell per wall thickness and facial skin thickness | |

| Han et al. [29] | Aerospace | 2024-T351 aluminum alloy plates | The simulations using the Lode independent slightly modified Johnson–Cook fracture criterion overpredicted the ballistic resistance of the target with increasing thickness. The deviation of the predicted ballistic limit velocity of 2, 4, 4.82, 8, and 9.94 mm thick targets from the corresponding experimental values was, respectively, 12.3, 0.1, 0.0, 4.2, and 4.9% for simulations, while it is 9.0, 17.5, 21.5, 24.2, and 26.3%, respectively |

Research by Khaire et al. [25] in the naval industries aims to know the performance of the honeycomb core cylindrical sandwich against the ballistic load of the conical nosed projectile. The conclusion of this study is that when the skin thickness and cell per wall thickness changed from 0.7 to 2.0 mm and 0.03 to 0.09 mm, the ballistic limit increased by 72.2 m/s and 10.9 m/s, respectively. However, when the side length changes from 3.2 to 9.2 mm, the ballistic limit decreases by 9.9 m/s. Wu et al. [26] investigated a composite armor system using aramid–carbon hybrid FRP laminated composite structures when exposed to ballistic loads from a 7.62 M61 AP projectile. The conclusion is the main failure modes of FRP laminates are fiber compression failure and tensile matrix failure, both of which can also be affected by changes in the stacking order of the FRP laminate. When the carbon fiber is stacked on the top of the FRP laminate, both the fiber compression failure area and the matrix tensile failure area are the lowest. Research on shipbuilding structure was conducted by Yang et al. [27], namely, regarding the performance of a composite double-arrow auxetic structure against ballistic loads from hemispherical shaped projectiles. The conclusion of this research is METC auxetic structure with a relative density of 16.66, which is 23.06% greater than that of the auxetic structure with a relative density of 9.08%. The ballistic limit speed increased by 35.56 and 54.89%, along with the increase in relative density from 9.08 to 16.66 and 23.06%, which has been validated by the experiment. Vescovini et al. [28] studied on composite structures using interply hybrid composites of woven Kevlar and S2-glass when ground with 0.357 Magnum FMJ. The conclusion of this study is that the deviation at the ballistic limit is always lower than 5.33% and has a maximum of 3.87% at an impact speed of 430 m/s, close to the ballistic limit. Also, although the numerical ballistic curve shows a generally smoother transition to the linear part, it fits very well with the experimental one. Mohammad et al. [16] conducted that the ballistic performance of monolithic shell targets decreased by 6.49%, whereas layered targets showed 3.88% reduction in impact resisting capacity at oblique impacts. Han et al. [29] analyzed that the deviation of the predicted ballistic limit velocities of 2-, 4-, 4.82-, 8-, and 9.94-mm-thick targets from the corresponding experimental values were, respectively, 12.3, 0.1, 0.0, 4.2, and 4.9% for simulations, while these are 9.0, 17.5, 21.5, 24.2, and 26.3%, respectively.

Research on ballistic impact has been carried out in various fields. Table 1 shows each research conducted using one type of projectile to determine the impact of damage and the amount of energy absorbed. In this case, a comparison of the engineering structures subjected to ballistic type is still scant. Therefore, in this study, four types of projectile shapes were used to determine the damage caused when struck by different projectiles. In the case of ship hijacking, it is indeed impossible to predict which form of the projectile will be used to hijack the ship.

3 Benchmark and mesh convergence study

3.1 Experiment profile

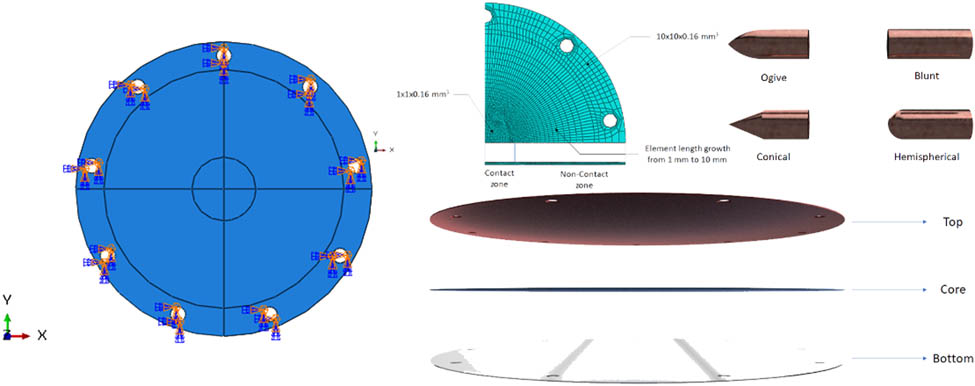

The ballistic impact experiment on a monolayered plate with a thickness of 2 mm used four projectile shapes, namely, blunt, conical, hemispherical, and ogive adapted from [16] to observe the impact on the target plate. The material of the projectile is an EN-24 steel bar. The length and diameter of the projectiles were 50.8 and 19 mm, respectively, in each uniform variation for equalizing conditions. All projectiles have the same mass, which had 52.5 g, equivalent to the projectile’s thickness, and the projectile’s density was 7,650 kg/m3 (Figure 2).

Dimension for (a) ogive, (b) blunt, (c) conical, and (d) hemispherical projectile shape (in mm).

All target plates were made of 1100-H12 aluminum with a plate thickness of 1 and 2 mm. The target plate was cut into circles with a total diameter of 315 mm and had nine holes with a diameter of 8 mm as plate holders during the experiment. This experiment was based on a study by Iqbal et al.; the experiment found that for ogive and blunt projectiles, the effective ratio of span diameter to projectile diameter (D/d) is between 3.6 and 10; increasing the ratio, will not increase the energy absorption. To get the maximum results by using four kinds of projectile shapes, the size of the most effective span diameter was 255 mm.

A representation of the experimental method and all components that were used is shown in Figure 3, which also has prepared by Mohammad et al. [16]. The projectile was driven using a compressed-air pneumatic gun with a maximum speed of 200 m/s. A camera was used to observe the value of the residual velocity. In the end, the projectile stops at the projectile catcher after penetrating the target plate.

Schematic experiment.

3.2 Mesh strategy

The target plate was divided into two zones, namely, contact and non-contact zone; all zones were meshed with three-dimensional eight-node brick elements (C3D8R) in a unit aspect ratio. In the non-contact zone ratio, the meshing size varied based on the distance from the center of the target plate. Meshing size growth from 1 mm to 10 mm was in line with the distance from the center of the target plate. In the contact zone, the mesh size was 1 mm3 × 1 mm3 × 0.16 mm3.

The contact zone was part of the target plate that was in direct contact with the bullet, so numerical analysis was focused on this part. Furthermore, the non-contact zone was part of the target plate that was not in direct contact with the projectile so that the mesh size could be larger to reduce analysis computational time (Figure 4).

Meshing Strategy.

Using partitions on components aims to maintain accuracy but can reduce computation time to make the simulation more efficient. If one does not use partitions, the computation time will be longer. This method is carried out on each layer of the target plate.

3.3 Benchmarking result

Experiments conducted by Mohammad et al. [16] are used as a reference in performing numerical simulations. This experiment is a ballistic impact on a monolayered plate with a thickness of 2 mm using an ogive projectile shape. Initial velocity is the velocity of the projectile just before hitting the target plate obtained from experiments with high-speed cameras.

Table 2 shows the comparison of the results between the experimental and numerical simulations. The difference between the experimental and numerical simulation results slightly indicates that the numerical simulation is appropriate.

Residual velocity result

| Initial velocity (m/s) | Residual velocity (m/s) | Variation (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental result | Numerical result | ||

| 107.7 | 83.4 | 77 | 8 |

| 102.7 | 76.8 | 70.4 | 9 |

| 95.4 | 54.7 | 51.2 | 7 |

The results of the qualitative validation are also shown in Figure 5. The failure model is obtained when an ogive projectile is hit with a speed of 107.7 m/s. Both results have an almost identical shape and radial cracks in the direction of the velocity projectile. Both target configurations show the radial cracks formation leading to the petalling of the target in the same direction as the projectile.

![Figure 5

Validation results: (a) stress distribution numerical analysis (b) experimental result of monolithic target for 0° obliquity and 107.7 m/s velocity conducted by [16].](/document/doi/10.1515/jmbm-2022-0064/asset/graphic/j_jmbm-2022-0064_fig_005.jpg)

Validation results: (a) stress distribution numerical analysis (b) experimental result of monolithic target for 0° obliquity and 107.7 m/s velocity conducted by [16].

4 FE configuration

4.1 Geometrical model

The FE model consists of two parts, namely, the projectile and the target plate. There are four variations of the projectiles used, namely, blunt, conical, hemispherical, and ogive. Various projectiles are used to analyze failure mechanisms and determine the penetration phenomena caused for each projectile. The layer arrangement of the target plate is illustrated in Figure 6a. The bullet is defined as a rigid body with the discrete fixed element (R3D4) so that it will not deform. On the other side, the target plates are modeled as multilayered plates, with the thickness of each plate being 1 mm, and the diameter being 255 mm. Each plate layer has the same shape and size but with different materials, as shown in Figure 6b. The constituent materials for each layer are ZK61m magnesium alloy, 6061-T651 aluminum alloy, and 1100-H12 aluminum.

Numerical modeling: (a) plate target layers and (b) bullet shapes variation.

4.2 Material and failure definition

The materials used to vary the target plate are ZK61m magnesium alloy, 6061-T651 aluminum alloy, and 1100-H12 aluminum. Table 3 shows the strength comparison for each material. In this numerical analysis, the Johnson–Cook material model was applied to define the force and damage progression of the target plate when struck by a projectile.

| Properties | Aluminum 1100-H12 | Aluminum 6061-T651 | Magnesium ZK61m |

|---|---|---|---|

| Young’s modulus of elasticity, E (GPa) | 65.76 | 64 | 38.7 |

| Poisson’s ratio

|

0.30 | 0.33 | 0.34 |

| Proof/yield stress, A (MPa) | 102.75 | 278.20 | 280.20 |

| Strain hardening coefficient, B (MPa) | 168.11 | 245.20 | 333.14 |

| Strain hardening exponent, n | 0.1012 | 0.817 | 0.57 |

| Strain sensitivity coefficient, C | 0.001 | 0.0273 | 0.026 |

| Thermal softening constant, m | 0.859 | 2.387 | 0.885 |

| Reference strain rate | 1 | 0.00133 | 0.000208 |

| Melting temperature,

|

893 | 925 | 923 |

| Transition temperature,

|

293 | 294 | 278 |

| Fracture strain constants: | |||

| D 1 | 0.071 | −0.086 | −0.0796 |

| D 2 | 1.248 | 1.539 | 1.328 |

| D 3 | −1.142 | −1.681 | −1.55 |

| D 4 | 0.0097 | 0.01 | −0.03 |

| D 5 | 0 | 7.77 | 119.40 |

The Johnson–Cook damage model, which integrates the effect of stress triaxiality, strain rate, and temperature on the failure strain formed in the material, was used to simulate damage initiation in the target material [31]. Johnson–Cook strength and damage model are represented by Eqs. (14)–(16)

Johnson–Cook parameters use yield stress

where

where

4.3 Boundary conditions

The circular target plate model in this numerical simulation is made of two parts: the inner and outer zones. In the inner zone, the selected element size is set to fine, while in the outer zone, it is set to be coarser, and the size will increase along with the direction and the diameter of the circle. The purpose of making these parts is to shorten the computation time in the simulation. There are nine holes in the surrounding circular plate with the same distance between them. These holes serve as a holder for the target plate to stop them from moving when the collision process occurs. The translation constraints are made in these holes in the x, y, and z directions. Between layers of the target, the plate is defined to stick completely and there are no gaps. The interaction between in-contact layered targets is developed using a tangential friction coefficient that is assigned to be 0.5 as determined by [30]. Figure 7 shows the boundary condition modeling scheme for ABAQUS/CAE.

Boundary conditions model in ABAQUS/CAE.

5 Parametric study

5.1 Matrix for parametric study

All simulation variations are determined from each layer’s target plate constituent material, namely aluminum 1100-H12, aluminum 6061-T651, and magnesium ZK61m. Table 4 shows the parametric study design matrix for each simulation variation. This is done to determine the largest energy absorption capacity and compare the strengths of each model. This simulation uses 12 different target plate models to be pounded with four different types of projectiles with notations V1, V2, V3, and V4.

Numerical simulation variation

| Model (M) | Ogive (V1)/blunt (V2)/conical (V3)/hemispherical (V4) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Top | Core | Bottom | |

| 1 | Aluminum 1100-H12 | Magnesium ZK61m | Aluminum 1100-H12 |

| 2 | Aluminum 6061-T651 | Magnesium ZK61m | Aluminum 6061-T651 |

| 3 | Aluminum 1100-H12 | Magnesium ZK61m | Aluminum 6061-T651 |

| 4 | Aluminum 6061-T651 | Magnesium ZK61m | Aluminum 1100-H12 |

| 5 | Magnesium ZK61m | Aluminum 1100-H12 | Aluminum 1100-H12 |

| 6 | Magnesium ZK61m | Aluminum 1100-H12 | Aluminum 6061-T651 |

| 7 | Magnesium ZK61m | Aluminum 6061-T651 | Aluminum 6061-T651 |

| 8 | Magnesium ZK61m | Aluminum 6061-T651 | Aluminum 1100-H12 |

| 9 | Aluminum 1100-H12 | Aluminum 1100-H12 | Magnesium ZK61m |

| 10 | Aluminum 1100-H12 | Aluminum 6061-T651 | Magnesium ZK61m |

| 11 | Aluminum 6061-T651 | Aluminum 6061-T651 | Magnesium ZK61m |

| 12 | Aluminum 6061-T651 | Aluminum 1100-H12 | Magnesium ZK61m |

5.2 Numerical results

5.2.1 Stress behavior

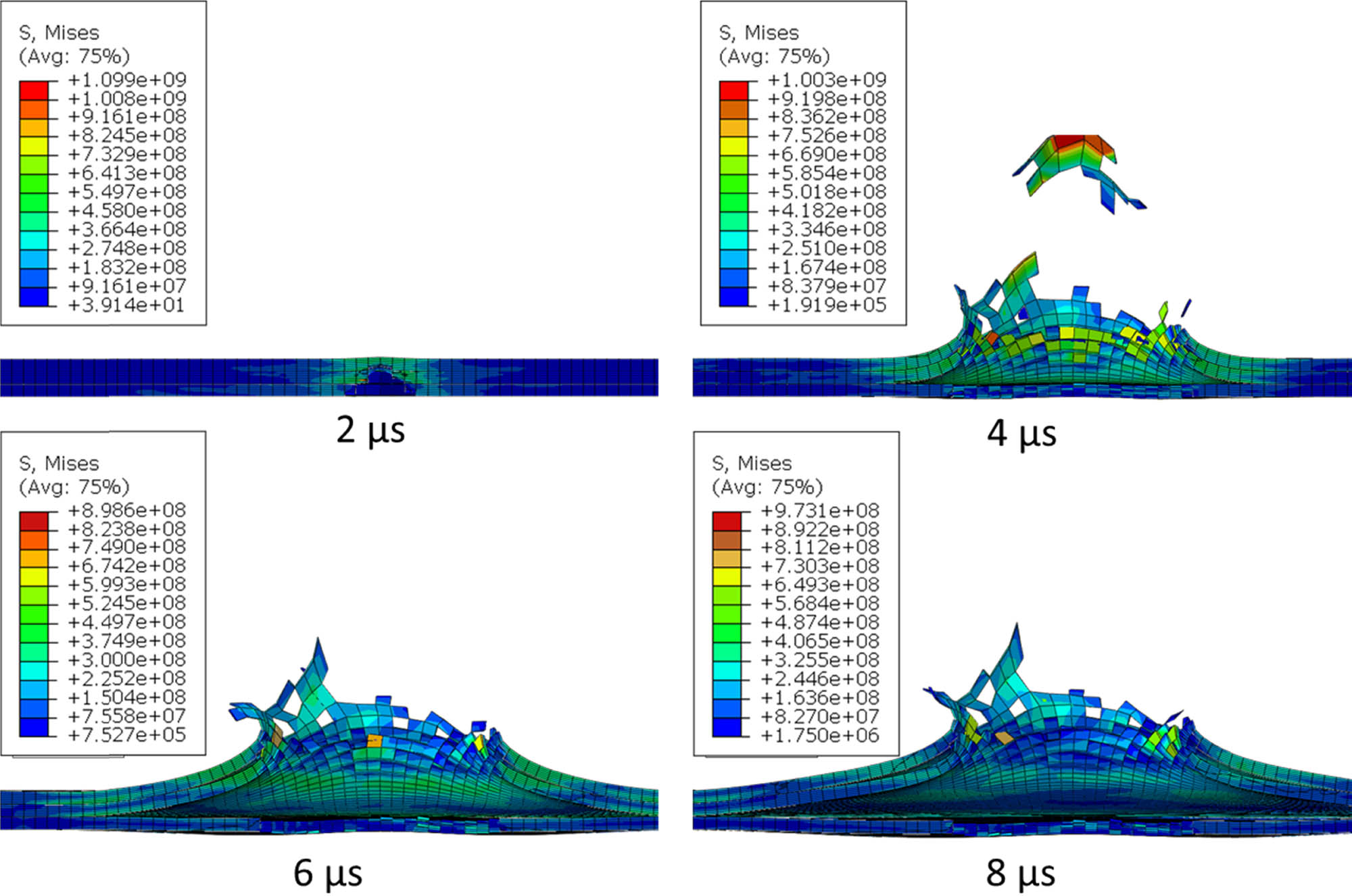

The stress value is a reaction from the collision process on the target plate. Each variation has a different energy absorption value. Figure 8 shows a comparison of the average stress values for each direction. It can be seen that model 3 has the highest average value of the other variations.

Average stress value every models.

The stress value used refers to the normal and tangential axes on the target plate so that there are six stress values. The graph of stress values for model 3 is relatively high, with plate layers of aluminum 1100-H12, magnesium ZK61m, and aluminum 6061-T651. Model 3 excels in the S33 value with a value of 1.085 × 109 Pa. This shows that the target plate arrangement in model 3 has high stress when it gets a ballistic load. Figures 9–12 show the progressive stress distribution when the plate is struck with ogive, blunt, conical, and hemispherical projectiles, respectively. The target plate is displayed in half to show the stress distribution on the target plate that is in direct contact with the projectile and the surrounding area.

Stress distribution and deformation for model 3 against ogive projectile.

Stress distribution and deformation for model 3 against blunt projectile.

Stress distribution and deformation for model 3 against conical projectile.

Stress distribution and deformation for model 3 against hemispherical projectile.

The shape of the projectile seems to affect the ballistic impact mechanisms. As shown in Figure 10 for model 3, the initial impact for the blunt projectile at

5.2.2 Strain behavior

The collision phenomenon, apart from generating stress, will also experience strain. The value of plastic strain is different for each variation. Figure 13 shows the plastic strain graph for each variation. It can be seen that model 2 has the highest average value of the other models, with a value of 9,633. In models 10–12, the plastic strain values are almost the same because the bottom layer uses magnesium ZK61m and only vary in the top and core layers.

Average plastic strain value for every models.

The phenomenon in variations for models 10–12 shows that magnesium ZK61m is not optimal when placed on the bottom layer because energy absorption cannot be maximized so that projectiles easily penetrate it. It will be more optimal if the magnesium ZK61m is placed on the top layer or core. The kinetic energy of the projectile can be well absorbed, thereby reducing the chance that the projectile can penetrate the target plate.

The plastic strain is the distorted body generated by force on the structure in which it does not return to its original size and shape. In this study, the effect of the projectile shape also seems to affect the plastic strain distribution of model 12. As shown in Figures 14–17, the final impact

Plastic strain distribution and deformation for model 12 against ogive projectile.

Plastic strain distribution and deformation for model 12 against blunt projectile.

Plastic strain distribution and deformation for model 12 against conical projectile.

Plastic strain distribution and deformation for model 12 against hemispherical projectile.

5.2.3 Deformation modes

The efficiency of a metal plate can be estimated from its plastic deformation after impact. This is an important mechanism of kinetic energy absorption from the projectile during penetration. Figure 18 shows the displacement that occurs in each variation. Models 9–12 have the highest deformation value with a not too significant difference.

Average displacement value for every models.

The deformation that occurs in models 9–12 shows an impact after ballistic loading. This certainly needs to be reconsidered; in addition to the projectile that penetrates the target plate, it will be deformed so that part of the target plate may inflict additional damage to the protected component.

As shown in Figure 21, the shape of the projectile seems to affect the model deformation of ballistic impact model 7; in this case, it is the conical projectile. It also shows that the deformation seems to follow the shape of the conical projectile at time

Displacement for model 7 against ogive projectile.

Displacement for model 7 against blunt projectile.

Displacement for model 7 against conical projectile.

Displacement for model 7 against hemispherical projectile.

5.2.4 Performance of the sandwich plate target

The ability of the target plate to receive ballistic loads refers to the energy absorption results. The energy absorption value is obtained by calculating the stress and plastic strain on the normal and transverse axes. In addition, it is also necessary to pay attention to the shape of the plate deformation after the collision process because, of course, it will also affect the structure made. Figure 23 shows the energy absorption values for each variation.

Energy absorption for projectile shapes: (a) ogive, (b) blunt, (c) conical, and (d) hemispherical.

The highest energy absorption value obtained by model 2 when pounded using a conical projectile was 275.75 J. However, the highest average energy absorption value was obtained by model 3 because it produced 58.82 J when struck with an ogive projectile, 182.47 J with a blunt projectile, and 14.73 J with a hemispherical projectile.

5.2.5 Discussion

The numerical analysis of ballistic impact with different projectile shapes i.e., ogive, blunt, conical, and hemispherical appears to consider the effect on the energy absorption and the failure mechanism. In this study, the target that has been assessed is the circular sandwich plate which is composed of three layers with different materials such as 1100-H12 aluminum alloy, ZK61m magnesium alloy, and 6061-T651 aluminum alloy. This numerical simulation also uses the Johnson–Cook material model and is applied to ABAQUS/Explicit software. This Johnson–Cook material model has also assessed the ballistic impact performance in the previous study conducted in [34]. However, the model in this literature evaluates a strain rate sensitivity parameter for plastic deformation that involves ballistic impact with a hard spherical projectile.

Numerical results indicate that the ballistic impact of the sandwich plate, which is composed of three layers with different materials such as 1100-H12 aluminum alloy, ZK61m magnesium alloy, and 6061-T651 aluminum alloy has an important role in the ability of energy absorption. Sorting the material on the sandwich layer appears to be effective in enhancing the ability of energy absorption. The capability to absorb energy seems to varied along with the material composed of the sandwich plate and the projectile parameter. Model 3, in which the target plate consists of 1100-H12 aluminum, ZK61m magnesium, and 6061-T651 aluminum, has the highest average energy absorption with an ogive projectile, see Figure 23. The projectile shape parameter penetrating the sandwich plate also appears to affect energy absorption and model deformation. The previous study conducted by Abtew et al. [35] found that the ballistic impact mechanism was a very complex mechanical since the process mainly depends on the thickness, strength, ductility, toughness, and density of the target material and projectile parameters. Moreover, Mohammad et al. [16] also showed the similar deformation model on the affected area by the ballistic impact. The penetration profile is highly influenced by the projectile parameter. In this study, a comparison of the performance of sandwich plate targets and the penetrating projectile shapes, i.e., model 3 is presented in Section 5.2.1. It shows that the blunt projectile gives a uniform stress effect in the contact zone compared to the other projectile which is ogive, conical, and hemispherical which gives stress distribution concentrated in the center of the contact zone when time

6 Conclusions

This study shows that if magnesium ZK61m is placed in the core and bottom layers, the energy absorption of the projectile will be optimal compared to when placed in the top layer. The other constituent materials are aluminum 1100-H12 and aluminum 6061-T651. Twelve variations of target plates are obtained from these three types of material, which can be applied as a shipboard component. Simulations are carried out with four projectiles, namely, ogive, blunt, conical, and hemispherical. The velocity of the projectile is equal to 107.7 m/s.

The simulation results show the ability of each variation to withstand ballistic loads. The highest average stress value during the collision is in model 3, with variations in the top, core, and bottom plate layers: aluminum 1100-H12, magnesium ZK61m, and aluminum 6061-T651. The stress value obtained is used to calculate energy absorption. The energy absorption value of each variation is different when it is pounded with projectiles with other models. When using magnesium in the bottom layer, the energy absorption value tends to have the same value. This indicates optimal energy absorption when using magnesium ZK61m. However, the energy absorption value tends to be higher in model 3 when pounded with ogive and blunt projectiles. Of course, the application of this method needs to consider the manufacturing cost. Ballistic impact studies are not limited to just four types of projectiles, and there are many other methods of research to create structures with more optimal energy absorption.

Research on ballistic impact can still be developed further in the future. In this simulation, the target plate is a multilayered thin plate. In future research, it is possible to use a curvature target plate. The shape of the projectile can undoubtedly be varied so that the results obtained are accurate and can withstand the ballistic load of various projectiles. In its application to ship structures and paying attention to strength, one must also consider the cost and weight. The target used for further research may be applied to the ship structure so that it can determine the impact of damage caused by ballistic loads.

-

Funding information: The authors state no funding involved.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

References

[1] Crupi V, Epasto G, Guglielmino E. Comparison of aluminium sandwiches for lightweight ship structures: honeycomb vs foam. Mar Struct. 2013;30:74–96.10.1016/j.marstruc.2012.11.002Search in Google Scholar

[2] Rahimijonoush A, Bayat M. Experimental and numerical studies on the ballistic impact response of titanium sandwich panels with different facesheets thickness ratios. Thin-Walled Struct. 2020;157:107079.10.1016/j.tws.2020.107079Search in Google Scholar

[3] Cao B, Bae D-M, Sohn J-M, Prabowo AR, Chen TH, Li H. Numerical analysis for damage characteristics caused by ice. Proceedings of the ASME 2016 35th International Conference on Ocean, Offshore and Arctic Engineering. Volume 8: Polar and Arctic Sciences and Technology; Petroleum Technology; 2016 Jun 19-24; Busan, South Korea. ASME; 2016.Search in Google Scholar

[4] Børvik T, Langseth M, Hopperstad OS, Malo KA. Ballistic penetration of steel plates. Int J Impact Eng. 1999;22:855–86.10.1016/S0734-743X(99)00011-1Search in Google Scholar

[5] Thomson WT. An approximate theory of armor penetration. J Appl Phys. 1955;26:80–2.10.1063/1.1721868Search in Google Scholar

[6] Calder CA, Goldsmith W. Plastic deformation and perforation of thin plates resulting from projectile impact. Int J Solids Struct. 1971;7:863–81.10.1016/0020-7683(71)90096-5Search in Google Scholar

[7] Shadbolt PJ, Corran RSJ, Ruiz C. A comparison of plate perforation models in the sub-ordnance impact velocity range. Int J Impact Eng. 1983;1:23–49.10.1016/0734-743X(83)90011-8Search in Google Scholar

[8] Neilson AJ. Empirical equations for the perforation of mild steel plates. Int J Impact Eng. 1985;3:137–42.10.1016/0734-743X(85)90031-4Search in Google Scholar

[9] Landkof B, Goldsmith W. Petalling of thin, metallic plates during penetration by cylindro-conical projectiles. Int J Solids Struct. 1985;21:245–66.10.1016/0020-7683(85)90021-6Search in Google Scholar

[10] Wen HM, Jones N. Low-velocity perforation of punch-lmpact-loaded metal plates. J Press Vessel Technol Trans ASME. 1996;118:181–7.10.1115/1.2842178Search in Google Scholar

[11] Liu D, Stronge WJ. Perforation of rigid-plastic plate by blunt missile. Int J Impact Eng. 1995;16:739–58.10.1016/0734-743X(95)00010-8Search in Google Scholar

[12] Gupta NK, Ansari R, Gupta SK. Normal impact of ogive nosed projectiles on thin plates. Int J Impact Eng. 2001;25:641–60.10.1016/S0734-743X(01)00003-3Search in Google Scholar

[13] Khan WU, Ansari R, Gupta NK. Oblique impact of projectile on thin aluminium plates. Def Sci J. 2003;53:139–46.10.14429/dsj.53.2138Search in Google Scholar

[14] Iqbal MA, Tiwari G, Gupta PK, Bhargava P. Ballistic performance and energy absorption characteristics of thin aluminium plates. Int J Impact Eng. 2015;77:1–15.10.1016/j.ijimpeng.2014.10.011Search in Google Scholar

[15] Tiwari G, Iqbal MA, Gupta PK. Energy absorption characteristics of thin aluminium plate against hemispherical nosed projectile impact. Thin-Walled Struct. 2018;126:246–57.10.1016/j.tws.2017.04.014Search in Google Scholar

[16] Mohammad Z, Gupta PK, Baqi A. Experimental and numerical investigations on the behavior of thin metallic plate targets subjected to ballistic impact. Int J Impact Eng. 2020;146:103717.10.1016/j.ijimpeng.2020.103717Search in Google Scholar

[17] Deng Y, Zhang Y, Xiao X, Hu A, Wu H, Xiong J. Experimental and numerical study on the ballistic impact behavior of 6061-T651 aluminum alloy thick plates against blunt-nosed projectiles. Int J Impact Eng. 2020;144:103659.10.1016/j.ijimpeng.2020.103659Search in Google Scholar

[18] Wen H, Mahmoud H. New model for ductile fracture of metal alloys. i: monotonic loading. J Eng Mech. 2016;142:04015088.10.1061/(ASCE)EM.1943-7889.0001009Search in Google Scholar

[19] Johnson GR, Cook WH. A computational constitutive model and data for metals subjected to large strain, high strain rates and high pressures. Proceedings Seventh Inf Symp Ballist. 1983;541–7.Search in Google Scholar

[20] Documentation A. Abaqus analysis user’s guide. Johnston, United States: Simulia; 2014.Search in Google Scholar

[21] Wielewski E, Birkbeck A, Thomson R. Ballistic resistance of spaced multi-layer plate structures: experiments on fibre reinforced plastic targets and an analytical framework for calculating the ballistic limit. Mater Des. 2013;50:737–41.10.1016/j.matdes.2013.03.006Search in Google Scholar

[22] Goda I, Girardot J. A computational framework for energy absorption and damage assessment of laminated composites under ballistic impact and new insights into target parameters. Aerosp Sci Technol. 2021;115:106835.10.1016/j.ast.2021.106835Search in Google Scholar

[23] Chatterjee VA, Saraswat R, Verma SK, Bhattacharjee D, Biswas I, Neogi S. Embodiment of dilatant fluids in fused-double-3D-mat sandwich composite panels and its effect on energy-absorption when subjected to high-velocity ballistic impact. Compos Struct. 2020;249:112588.10.1016/j.compstruct.2020.112588Search in Google Scholar

[24] Yu S, Yu X, Ao Y, Mei J, Jiang W, Liu J, et al. The impact resistance of composite Y-shaped cores sandwich structure. Thin-Walled Struct. 2021;169:108389.10.1016/j.tws.2021.108389Search in Google Scholar

[25] Khaire N, Tiwari G, Rathod S, Iqbal MA, Topa A. Perforation and energy dissipation behaviour of honeycomb core cylindrical sandwich shell subjected to conical shape projectile at high velocity impact. Thin-Walled Struct. 2022;171:108724.10.1016/j.tws.2021.108724Search in Google Scholar

[26] Wu S, Xu Z, Hu C, Zou X, He X. Numerical simulation study of ballistic performance of Al2O3/aramid–carbon hybrid FRP laminate composite structures subject to impact loading. Ceram Int. 2022;48:6423–35.10.1016/j.ceramint.2021.11.186Search in Google Scholar

[27] Yang W, Huang R, Liu J, Liu J, Huang W. Ballistic impact responses and failure mechanism of composite double-arrow auxetic structure. Thin-Walled Struct. 2022;174:109087.10.1016/j.tws.2022.109087Search in Google Scholar

[28] Vescovini A, Balen L, Scazzosi R, da Silva AAX, Amico SC, Giglio M, et al. Numerical investigation on the hybridization effect in inter-ply S2-glass and aramid woven composites subjected to ballistic impacts. Compos Struct. 2021;276:114506.10.1016/j.compstruct.2021.114506Search in Google Scholar

[29] Han J, Shi Y, Ma Q, Vershinin VV, Chen X, Xiao X, et al. Experimental and numerical investigation on the ballistic resistance of 2024-T351 aluminum alloy plates with various thicknesses struck by blunt projectiles. Int J Impact Eng. 2022;163:104182.10.1016/j.ijimpeng.2022.104182Search in Google Scholar

[30] Deng Y, Hu A, Xiao X, Jia B. Experimental and numerical investigation on the ballistic resistance of ZK61m magnesium alloy plates struck by blunt and ogival projectiles. Int J Impact Eng. 2021;158:104021.10.1016/j.ijimpeng.2021.104021Search in Google Scholar

[31] Johnson GR, Cook WH. Fracture characteristics of three metals subjected to various strains, strain rates, temperatures and pressures. Eng Fract Mech. 1985;21:31–48.10.1016/0013-7944(85)90052-9Search in Google Scholar

[32] Clausen AH, Børvik T, Hopperstad OS, Benallal A. Flow and fracture characteristics of aluminium alloy AA5083–H116 as function of strain rate, temperature and triaxiality. Mater Sci Eng A. 2004;364:260–72.10.1016/j.msea.2003.08.027Search in Google Scholar

[33] Gupta NK, Iqbal MA, Sekhon GS. Effect of projectile nose shape, impact velocity and target thickness on deformation behavior of aluminum plates. Int J Solids Struct. 2007;44:3411–39.10.1016/j.ijsolstr.2006.09.034Search in Google Scholar

[34] Burley M, Campbell JE, Dean J, Clyne TW. Johnson-Cook parameter evaluation from ballistic impact data via iterative FEM modelling. Int J Impact Eng. 2018;112:180–92.10.1016/j.ijimpeng.2017.10.012Search in Google Scholar

[35] Abtew MA, Boussu F, Bruniaux P, Loghin C, Cristian I. Ballistic impact mechanisms – A review on textiles and fibre-reinforced composites impact responses. Compos Struct. 2019;223:110966.10.1016/j.compstruct.2019.110966Search in Google Scholar

[36] Prabowo AR, Ridwan R, Tuswan T, Sohn JM, Surojo E, Imaduddin F. Effect of the selected parameters in idealizing material failures under tensile loads: benchmarks for damage analysis on thin-walled structures. Curved Layer Struct. 2022;9:258–85.10.1515/cls-2022-0021Search in Google Scholar

[37] Sanjaya Y, Prabowo AR, Imaduddin F, Nordin NAB. Design and analysis of mesh size subjected to wheel rim convergence using finite element method. Proc Struc Integ. 2021;33(C):51–8.10.1016/j.prostr.2021.10.008Search in Google Scholar

[38] Majid IA, Laksono FB, Suryanto H, Prabowo AR. Structural assessment of ladder frame chassis using FE analysis: a designed construction referring to ford AC cobra. Proc Struc Integ. 2021;33:35–42.10.1016/j.prostr.2021.10.006Search in Google Scholar

[39] Akbar MS, Prabowo AR, Tjahjana DDDP, Tuswan T. Analysis of plated-hull structure strength against hydrostatic and hydrodynamic loads: a case study of 600 TEU container ships. J Mech Behav Mat. 2021;30:237–48.10.1515/jmbm-2021-0025Search in Google Scholar

[40] Prabowo AR, Tuswan T, Nurcholis A, Pratama AA. Structural resistance of simplified side hull models accounting for stiffener design and loading type. Math Prob Eng. 2021;2021:6229498–519.10.1155/2021/6229498Search in Google Scholar

[41] Widiyanto I, Alwan FHA, Mubarok MAH, Prabowo AR, Laksono FB, Bahatmaka A, et al. Effect of geometrical variations on the structural performance of shipping container panels: a parametric study towards a new alternative design. Curved Layer Struct. 2021;8:271–306.10.1515/cls-2021-0024Search in Google Scholar

[42] Prabowo AR, Cao B, Sohn JM, Bae DM. Crashworthiness assessment of thin-walled double bottom tanker: influences of seabed to structural damage and damage-energy formulae for grounding damage calculations. J Ocean Eng Sci. 2020;5:387–400.10.1016/j.joes.2020.03.002Search in Google Scholar

[43] Zhang W, Li J, Liang L, Yang Q. A systematic literature survey of the yield or failure criteria used for ice material. Ocean Eng. 2022;254:111360.10.1016/j.oceaneng.2022.111360Search in Google Scholar

[44] Gledić I, Parunov J, Prebeg P, Ćorak M. Low-cycle fatigue of ship hull damaged in collision. Eng Failure Anal. 2019;96:436–54.10.1016/j.engfailanal.2018.11.005Search in Google Scholar

[45] Prabowo AR, Do QT, Cao B, Bae DM. Land and marine-based structures subjected to explosion loading: a review on critical transportation and infrastructure. Proc Struc Integ. 2020;27:77–84.10.1016/j.prostr.2020.07.011Search in Google Scholar

[46] Dabit AS, Lianto AE, Branta SA, Laksono FB, Prabowo AR, Muhayat N. Perancangan Kapal Tanpa Awak Penebar Pakan Lkan di Wilayah Pesisir Pantai Berbasis Microcontroller Arduino. Mekanika. 2020;19:74–82 (in Indonesian).10.20961/mekanika.v19i2.43671Search in Google Scholar

[47] Febrianto RA, Prabowo AR, Baek SJ, Adiputra R. Analysis of monohull design characteristics as supporting vessel for the COVID-19 medical treatment and logistic. Trans Res Proc. 2021;55:699–706.10.1016/j.trpro.2021.07.038Search in Google Scholar

© 2022 Faiz Haidar Ahmad Alwan et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Calcium carbonate nanoparticles of quail’s egg shells: Synthesis and characterizations

- Effect of welding consumables on shielded metal arc welded ultra high hard armour steel joints

- Stress-strain characteristics and service life of conventional and asphaltic underlayment track under heavy load Babaranjang trains traffic

- Corrigendum to: Statistical mechanics of cell decision-making: the cell migration force distribution

- Prediction of bearing capacity of driven piles for Basrah governatore using SPT and MATLAB

- Investigation on microstructural features and tensile shear fracture properties of resistance spot welded advanced high strength dual phase steel sheets in lap joint configuration for automotive frame applications

- Experimental and numerical investigation of drop weight impact of aramid and UHMWPE reinforced epoxy

- An experimental study and finite element analysis of the parametric of circular honeycomb core

- The study of the particle size effect on the physical properties of TiO2/cellulose acetate composite films

- Hybrid material performance assessment for rocket propulsion

- Design of ER damper for recoil length minimization: A case study on gun recoil system

- Forecasting technical performance and cost estimation of designed rim wheels based on variations of geometrical parameters

- Enhancing the machinability of SKD61 die steel in power-mixed EDM process with TGRA-based multi criteria decision making

- Effect of boron carbide reinforcement on properties of stainless-steel metal matrix composite for nuclear applications

- Energy absorption behaviors of designed metallic square tubes under axial loading: Experiment-based benchmarking and finite element calculation

- Synthesis and study of magnesium complexes derived from polyacrylate and polyvinyl alcohol and their applications as superabsorbent polymers

- Artificial neural network for predicting the mechanical performance of additive manufacturing thermoset carbon fiber composite materials

- Shock and impact reliability of electronic assemblies with perimeter vs full array layouts: A numerical comparative study

- Influences of pre-bending load and corrosion degree of reinforcement on the loading capacity of concrete beams

- Assessment of ballistic impact damage on aluminum and magnesium alloys against high velocity bullets by dynamic FE simulations

- On the applicability of Cu–17Zn–7Al–0.3Ni shape memory alloy particles as reinforcement in aluminium-based composites: Structural and mechanical behaviour considerations

- Mechanical properties of laminated bamboo composite as a sustainable green material for fishing vessel: Correlation of layer configuration in various mechanical tests

- Singularities at interface corners of piezoelectric-brass unimorphs

- Evaluation of the wettability of prepared anti-wetting nanocoating on different construction surfaces

- Review Article

- An overview of cold spray coating in additive manufacturing, component repairing and other engineering applications

- Special Issue: Sustainability and Development in Civil Engineering - Part I

- Risk assessment process for the Iraqi petroleum sector

- Evaluation of a fire safety risk prediction model for an existing building

- The slenderness ratio effect on the response of closed-end pipe piles in liquefied and non-liquefied soil layers under coupled static-seismic loading

- Experimental and numerical study of the bulb's location effect on the behavior of under-reamed pile in expansive soil

- Procurement challenges analysis of Iraqi construction projects

- Deformability of non-prismatic prestressed concrete beams with multiple openings of different configurations

- Response of composite steel-concrete cellular beams of different concrete deck types under harmonic loads

- The effect of using different fibres on the impact-resistance of slurry infiltrated fibrous concrete (SIFCON)

- Effect of microbial-induced calcite precipitation (MICP) on the strength of soil contaminated with lead nitrate

- The effect of using polyolefin fiber on some properties of slurry-infiltrated fibrous concrete

- Typical strength of asphalt mixtures compacted by gyratory compactor

- Modeling and simulation sedimentation process using finite difference method

- Residual strength and strengthening capacity of reinforced concrete columns subjected to fire exposure by numerical analysis

- Effect of magnetization of saline irrigation water of Almasab Alam on some physical properties of soil

- Behavior of reactive powder concrete containing recycled glass powder reinforced by steel fiber

- Reducing settlement of soft clay using different grouting materials

- Sustainability in the design of liquefied petroleum gas systems used in buildings

- Utilization of serial tendering to reduce the value project

- Time and finance optimization model for multiple construction projects using genetic algorithm

- Identification of the main causes of risks in engineering procurement construction projects

- Identifying the selection criteria of design consultant for Iraqi construction projects

- Calibration and analysis of the potable water network in the Al-Yarmouk region employing WaterGEMS and GIS

- Enhancing gypseous soil behavior using casein from milk wastes

- Structural behavior of tree-like steel columns subjected to combined axial and lateral loads

- Prospect of using geotextile reinforcement within flexible pavement layers to reduce the effects of rutting in the middle and southern parts of Iraq

- Ultimate bearing capacity of eccentrically loaded square footing over geogrid-reinforced cohesive soil

- Influence of water-absorbent polymer balls on the structural performance of reinforced concrete beam: An experimental investigation

- A spherical fuzzy AHP model for contractor assessment during project life cycle

- Performance of reinforced concrete non-prismatic beams having multiple openings configurations

- Finite element analysis of the soil and foundations of the Al-Kufa Mosque

- Flexural behavior of concrete beams with horizontal and vertical openings reinforced by glass-fiber-reinforced polymer (GFRP) bars

- Studying the effect of shear stud distribution on the behavior of steel–reactive powder concrete composite beams using ABAQUS software

- The behavior of piled rafts in soft clay: Numerical investigation

- The impact of evaluation and qualification criteria on Iraqi electromechanical power plants in construction contracts

- Performance of concrete thrust block at several burial conditions under the influence of thrust forces generated in the water distribution networks

- Geotechnical characterization of sustainable geopolymer improved soil

- Effect of the covariance matrix type on the CPT based soil stratification utilizing the Gaussian mixture model

- Impact of eccentricity and depth-to-breadth ratio on the behavior of skirt foundation rested on dry gypseous soil

- Concrete strength development by using magnetized water in normal and self-compacted concrete

- The effect of dosage nanosilica and the particle size of porcelanite aggregate concrete on mechanical and microstructure properties

- Comparison of time extension provisions between the Joint Contracts Tribunal and Iraqi Standard Bidding Document

- Numerical modeling of single closed and open-ended pipe pile embedded in dry soil layers under coupled static and dynamic loadings

- Mechanical properties of sustainable reactive powder concrete made with low cement content and high amount of fly ash and silica fume

- Deformation of unsaturated collapsible soils under suction control

- Mitigation of collapse characteristics of gypseous soils by activated carbon, sodium metasilicate, and cement dust: An experimental study

- Behavior of group piles under combined loadings after improvement of liquefiable soil with nanomaterials

- Using papyrus fiber ash as a sustainable filler modifier in preparing low moisture sensitivity HMA mixtures

- Study of some properties of colored geopolymer concrete consisting of slag

- GIS implementation and statistical analysis for significant characteristics of Kirkuk soil

- Improving the flexural behavior of RC beams strengthening by near-surface mounting

- The effect of materials and curing system on the behavior of self-compacting geopolymer concrete

- The temporal rhythm of scenes and the safety in educational space

- Numerical simulation to the effect of applying rationing system on the stability of the Earth canal: Birmana canal in Iraq as a case study

- Assessing the vibration response of foundation embedment in gypseous soil

- Analysis of concrete beams reinforced by GFRP bars with varying parameters

- One dimensional normal consolidation line equation

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Calcium carbonate nanoparticles of quail’s egg shells: Synthesis and characterizations

- Effect of welding consumables on shielded metal arc welded ultra high hard armour steel joints

- Stress-strain characteristics and service life of conventional and asphaltic underlayment track under heavy load Babaranjang trains traffic

- Corrigendum to: Statistical mechanics of cell decision-making: the cell migration force distribution

- Prediction of bearing capacity of driven piles for Basrah governatore using SPT and MATLAB

- Investigation on microstructural features and tensile shear fracture properties of resistance spot welded advanced high strength dual phase steel sheets in lap joint configuration for automotive frame applications

- Experimental and numerical investigation of drop weight impact of aramid and UHMWPE reinforced epoxy

- An experimental study and finite element analysis of the parametric of circular honeycomb core

- The study of the particle size effect on the physical properties of TiO2/cellulose acetate composite films

- Hybrid material performance assessment for rocket propulsion

- Design of ER damper for recoil length minimization: A case study on gun recoil system

- Forecasting technical performance and cost estimation of designed rim wheels based on variations of geometrical parameters

- Enhancing the machinability of SKD61 die steel in power-mixed EDM process with TGRA-based multi criteria decision making

- Effect of boron carbide reinforcement on properties of stainless-steel metal matrix composite for nuclear applications

- Energy absorption behaviors of designed metallic square tubes under axial loading: Experiment-based benchmarking and finite element calculation

- Synthesis and study of magnesium complexes derived from polyacrylate and polyvinyl alcohol and their applications as superabsorbent polymers

- Artificial neural network for predicting the mechanical performance of additive manufacturing thermoset carbon fiber composite materials

- Shock and impact reliability of electronic assemblies with perimeter vs full array layouts: A numerical comparative study

- Influences of pre-bending load and corrosion degree of reinforcement on the loading capacity of concrete beams

- Assessment of ballistic impact damage on aluminum and magnesium alloys against high velocity bullets by dynamic FE simulations

- On the applicability of Cu–17Zn–7Al–0.3Ni shape memory alloy particles as reinforcement in aluminium-based composites: Structural and mechanical behaviour considerations

- Mechanical properties of laminated bamboo composite as a sustainable green material for fishing vessel: Correlation of layer configuration in various mechanical tests

- Singularities at interface corners of piezoelectric-brass unimorphs

- Evaluation of the wettability of prepared anti-wetting nanocoating on different construction surfaces

- Review Article

- An overview of cold spray coating in additive manufacturing, component repairing and other engineering applications

- Special Issue: Sustainability and Development in Civil Engineering - Part I

- Risk assessment process for the Iraqi petroleum sector

- Evaluation of a fire safety risk prediction model for an existing building

- The slenderness ratio effect on the response of closed-end pipe piles in liquefied and non-liquefied soil layers under coupled static-seismic loading

- Experimental and numerical study of the bulb's location effect on the behavior of under-reamed pile in expansive soil

- Procurement challenges analysis of Iraqi construction projects

- Deformability of non-prismatic prestressed concrete beams with multiple openings of different configurations

- Response of composite steel-concrete cellular beams of different concrete deck types under harmonic loads

- The effect of using different fibres on the impact-resistance of slurry infiltrated fibrous concrete (SIFCON)

- Effect of microbial-induced calcite precipitation (MICP) on the strength of soil contaminated with lead nitrate

- The effect of using polyolefin fiber on some properties of slurry-infiltrated fibrous concrete

- Typical strength of asphalt mixtures compacted by gyratory compactor

- Modeling and simulation sedimentation process using finite difference method

- Residual strength and strengthening capacity of reinforced concrete columns subjected to fire exposure by numerical analysis

- Effect of magnetization of saline irrigation water of Almasab Alam on some physical properties of soil

- Behavior of reactive powder concrete containing recycled glass powder reinforced by steel fiber

- Reducing settlement of soft clay using different grouting materials

- Sustainability in the design of liquefied petroleum gas systems used in buildings

- Utilization of serial tendering to reduce the value project

- Time and finance optimization model for multiple construction projects using genetic algorithm

- Identification of the main causes of risks in engineering procurement construction projects

- Identifying the selection criteria of design consultant for Iraqi construction projects

- Calibration and analysis of the potable water network in the Al-Yarmouk region employing WaterGEMS and GIS

- Enhancing gypseous soil behavior using casein from milk wastes

- Structural behavior of tree-like steel columns subjected to combined axial and lateral loads

- Prospect of using geotextile reinforcement within flexible pavement layers to reduce the effects of rutting in the middle and southern parts of Iraq

- Ultimate bearing capacity of eccentrically loaded square footing over geogrid-reinforced cohesive soil

- Influence of water-absorbent polymer balls on the structural performance of reinforced concrete beam: An experimental investigation

- A spherical fuzzy AHP model for contractor assessment during project life cycle

- Performance of reinforced concrete non-prismatic beams having multiple openings configurations

- Finite element analysis of the soil and foundations of the Al-Kufa Mosque

- Flexural behavior of concrete beams with horizontal and vertical openings reinforced by glass-fiber-reinforced polymer (GFRP) bars

- Studying the effect of shear stud distribution on the behavior of steel–reactive powder concrete composite beams using ABAQUS software

- The behavior of piled rafts in soft clay: Numerical investigation

- The impact of evaluation and qualification criteria on Iraqi electromechanical power plants in construction contracts

- Performance of concrete thrust block at several burial conditions under the influence of thrust forces generated in the water distribution networks

- Geotechnical characterization of sustainable geopolymer improved soil

- Effect of the covariance matrix type on the CPT based soil stratification utilizing the Gaussian mixture model

- Impact of eccentricity and depth-to-breadth ratio on the behavior of skirt foundation rested on dry gypseous soil

- Concrete strength development by using magnetized water in normal and self-compacted concrete

- The effect of dosage nanosilica and the particle size of porcelanite aggregate concrete on mechanical and microstructure properties

- Comparison of time extension provisions between the Joint Contracts Tribunal and Iraqi Standard Bidding Document

- Numerical modeling of single closed and open-ended pipe pile embedded in dry soil layers under coupled static and dynamic loadings

- Mechanical properties of sustainable reactive powder concrete made with low cement content and high amount of fly ash and silica fume

- Deformation of unsaturated collapsible soils under suction control

- Mitigation of collapse characteristics of gypseous soils by activated carbon, sodium metasilicate, and cement dust: An experimental study

- Behavior of group piles under combined loadings after improvement of liquefiable soil with nanomaterials

- Using papyrus fiber ash as a sustainable filler modifier in preparing low moisture sensitivity HMA mixtures

- Study of some properties of colored geopolymer concrete consisting of slag

- GIS implementation and statistical analysis for significant characteristics of Kirkuk soil

- Improving the flexural behavior of RC beams strengthening by near-surface mounting

- The effect of materials and curing system on the behavior of self-compacting geopolymer concrete

- The temporal rhythm of scenes and the safety in educational space

- Numerical simulation to the effect of applying rationing system on the stability of the Earth canal: Birmana canal in Iraq as a case study

- Assessing the vibration response of foundation embedment in gypseous soil

- Analysis of concrete beams reinforced by GFRP bars with varying parameters

- One dimensional normal consolidation line equation