Abstract

We implement a paraxial azimuthally-radially polarized beam (ARPB), a novel class of structured light beams that can be optimal chiral (OC), leading to maximum chirality density at a given energy density. By using vectorial light shaping techniques, we successfully generated a paraxial ARPB with precise control over its features, validating theoretical predictions. Our findings demonstrate the ability to finely adjust the chirality density of the ARPB across its entire range by manipulating a single beam parameter. Although our experimental investigations are primarily focused on the transverse plane, we show that fields whose transverse components satisfy the optimal chirality condition are optimally chiral in all directions, and our results highlight the promising potential of OC structured light for applications in the sensing and manipulation of chiral particles. We show that helicity density is more general than the concept of handedness. This work represents a significant advancement toward practical optical enantioseparation and enantiomer detection at the nanoscale.

1 Introduction

Part of this study was inspired by the work of Prof. Federico Capasso, to whom this special issue is dedicated. The many topics Prof. Capasso worked on include helicity, chirality of light and the interaction with chiral matter, most notably in Refs. [1], [2], [3]. Some of the material of this paper was presented and discussed during the 2024 NanoPlasm Conference in Cetraro (IT) where Prof. Capasso’s 75th birthday was celebrated. The study of structured light is important for various applications, including the detection of chiral nanoparticles [1], [2], [3]. Chirality is a property of objects that are not superimposable with their mirror image [4]. Importantly, many biologically relevant molecules exist in chiral pairs, known as enantiomers [5]. The chiral nature of electromagnetic fields can be described using helicity density [6], [7], [8]. Traditionally, the “handedness” of circularly polarized light has been associated with the chirality of light, but here we show that the chirality density of light is much more general than the simple concept of handedness. For monochromatic beams with the implicit time dependence e−iωt , where ω is the angular frequency of light, the time-average helicity density h is [9], [10], [11].

where E and H represent the electric and magnetic field phasors of light, respectively. The term

In Ref. [10], it was shown that the magnitude of the helicity density of a monochromatic field, at a given time-average energy density u = ɛ 0|E|2/4 + μ 0|H|2/4 [12], has an upper bound, i.e., |h| ≤ u/ω always. Light fields that reach the upper bound |h| = u/ω are known as optimal chiral light (OCL). Circularly polarized light (CPL) is the most intuitive example of OCL [5], and the sign of h is related to the handedness of the CPL. The same upper bound for the magnitude of the helicity density was stated in Ref. [13] involving fields whose Fourier spectrum representation contains only plane waves with one circular polarization. However, the concepts of helicity density and optimal chirality hold true for any kind of monochromatic structured light, including cases where the magnetic and electric fields are polarized along a single (e.g., the beam’s longitudinal) direction, and the concept of handedness cannot be applied. The necessary and sufficient condition for fields to be locally optimally chiral is

where

The concepts of optimal chirality and self-duality are equivalent for monochromatic beams. Self-duality refers to fields that are unchanged by the duality transformation E → B and B → −E [13], [14]. These fields are eigenvectors of the curl [15], i.e., ∇ × E = k E. As shown in Ref. [16] without connecting the concepts of optimal chirality and self-duality, monochromatic fields satisfying the optimal chirality condition from Eq. (2) are eigenvectors of the curl operator, and therefore self-dual fields. Here we use the concept of optimal chirality instead of self-duality because we focus on the chirality features of the beam, rather than on the broader electromagnetic symmetries displayed by self-dual beams. Additionally, few self-dual fields seem to have been studied experimentally [17].

Optimally chiral structured beams are important because they combine two powerful effects: vectorially shaped light and maximized chirality density at a given energy density. This combination is advantageous because it allows for the control of enhanced interaction of the beam with chiral matter. As a result, optimally chiral structured beams open new possibilities for controlled sensing and manipulation of chiral particles. Moreover, the topology of tailored beams enables creative designs for chirality-discriminating optical traps [18], which aim at trapping an enantiomer while repelling its mirror image [1], [11], [19], [20], [21], [22].

The unprecedented control over the amplitude and phase of structured light [12], [23] also results in an exceptional ability to finely tune the helicity density h of a probing beam. This precise control allows one to tune the interaction between a chiral particle and an illuminating field by adjusting h [5] and it leads to a more detailed characterization of the interactions between the chiral sample and the fields, even beyond the commonly used dipolar approximation (the dipolar photoinduced chiral forces are described in Ref. [24]). The importance of higher-order multipoles on chiral interactions is investigated in Ref. [25]. Additionally, the control over the helicity density enables rapid changes in its sign (similar to reversing the “handedness” of circularly polarized light), facilitating the creation of dynamic optical potentials [26], [27] for enantioseparation and the experimental investigation of the chiral effects of higher-order multipoles.

However, the ability to generate optimally chiral structured beams is constrained. One must design an optical beam that satisfies the optimal chirality condition from Eq. (2) and effectively generate it. Here we implement a previously proposed example of a structured beam that displays optimal chirality: the azimuthally-radially polarized beam (ARPB) [10], [28], [29]. The ARPB consists of a phase-shifted combination of an azimuthally polarized beam and a radially polarized beam. It has been theoretically studied in the past, see Refs. [10], [28], [30], [31], and most comprehensively in Ref. [16]. The optimally chiral ARPB (OC-ARPB) combines the extraordinary properties of OCL with the spatial separation between its transverse fields, which vanish on the beam axis, and the longitudinal fields. OCL is present along the beam axis, solely due to E z and H z . Consequently, the ARPB has the potential to be used for controlled, on-axis separation of enantiomers or for enantiomer detection. The ARPB has also been recently studied in Refs. [32] and [33], without focusing on the chiral features of the ARPB.

Our work presents an experimental implementation of the ARPB, with a focus on characterizing its chirality and demonstrating its ability to achieve optimal chirality [10], [16]. By employing advanced vectorial shaping techniques, we have overcome limitations to the field’s stability and local polarization control to successfully generate a paraxial APRB with precise manipulation over its features, validating theoretical predictions. Importantly, we show that the helicity density of the ARPB can be tuned across its full range of possible values by varying a single beam parameter. While our findings are confined to studying the chirality density in the transverse plane, they demonstrate the potential of optimally chiral structured light for designing enantioseparating optical traps and advancing practical schemes for the sensing and manipulation of chiral particles. Additionally, we show in Section 4 that if the transverse fields of a beam satisfy the optimal chirality condition from Eq. (2), the longitudinal fields satisfy it as well.

2 Methods

2.1 Helicity density

The field phasors of the ARPB are [16]

where V is a complex amplitude with units of Volts. The parameters

where w is the beam radius, defined as

Adjusting the phase-shift ψ (referred to as the phase parameter of the ARPB) and the relative amplitude

Most notably, the ARPB has transverse fields that vanish on the beam axis (ρ = 0), where the longitudinal fields persist [10], [28], [30], [31]. This spatial separation between the transverse and longitudinal components of the beam results in vanishing linear and angular momentum densities on the beam axis [16], where only the energy and helicity densities (u and h respectively) associated with the longitudinal fields persist. For the ARPB, the time-average energy and helicity densities across the entire beam are [16]

where

and

2.2 Vectorial beam shaping

The paraxial ARPB is produced experimentally using spatial light modulators (SLMs), which introduce a digitally controlled spatially variable phase shift ϕ(x, y) to an incident optical field. The pixelated liquid crystal cells in an SLM differentially delay the phase of incident fields according to the voltage applied over each pixel. The SLM is controlled via a desktop computer (Dell XPS). For a calculated scalar field E, the hologram is produced by mapping the required phase values to voltages applied over the SLM screen. Since these are typically input into the SLM as 8-bit grayscale values, a pre-calibrated a lookup table is used to ensure a linear phase shift.

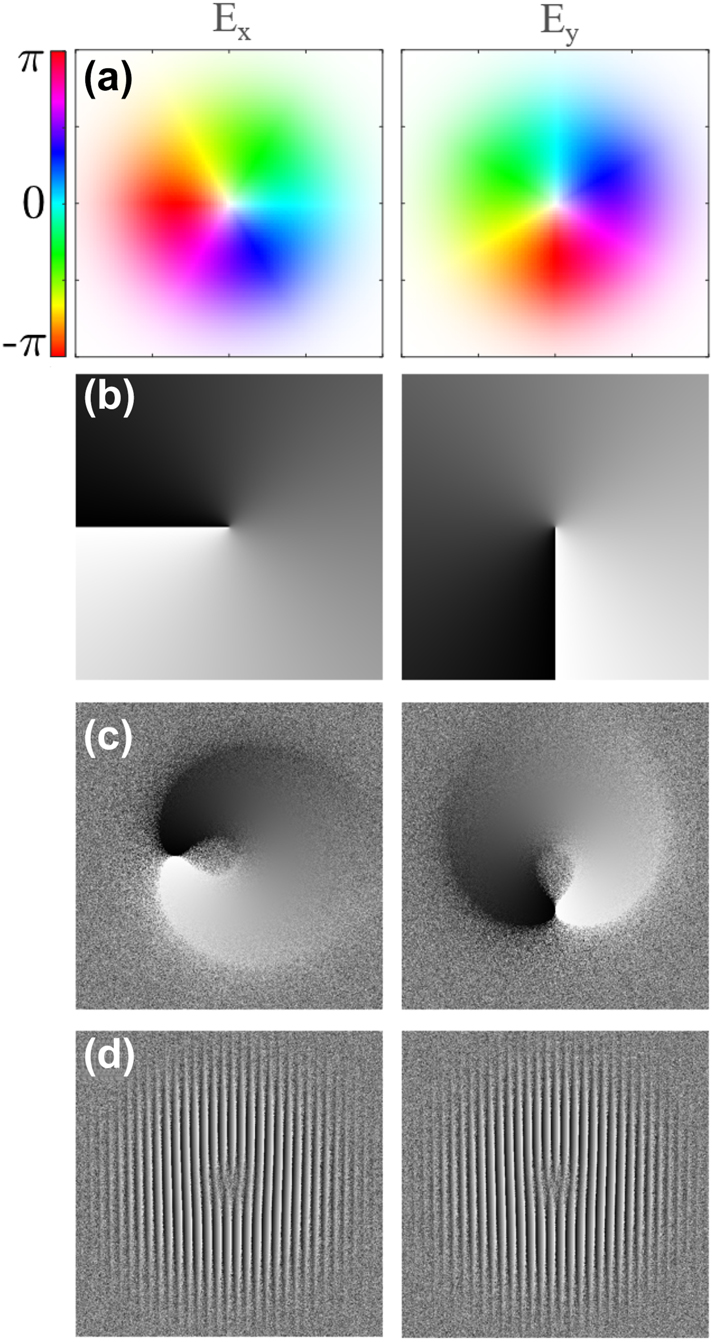

To ensure the desired wave function is accurately reproduced by the SLM, each phase we wish to imprint on a beam must be processed such that the desired phase and amplitude information are imparted to the beam while filtering unwanted intensity and diffraction orders. Although amplitude modulation is not directly available with a phase-only SLM, pseudo-amplitude modulation is possible. Amplitude modulation can be created using a scattering mask; the inverse amplitude, given by 1 − |E|2/max |E|2, is multiplied by a matrix of random integers and then applied to the grayscale phase hologram (see Figure 2(c)). This modulation redistributes unwanted power into higher spatial frequency components in k-space (see Ref. [34] for details). It is pertinent to understand that the radially symmetric intensity profile appears asymmetric in Figure 2(c); however, this is only a visual artifact arising from the use of a noncyclical grayscale map that must be used when displaying holograms on an SLM. The perceived asymmetry is a result of phase differences at the edge of the range which roll over into the adjacent wavefront appearing high contrast, where the same difference away from the bounds appears relatively low contrast. Lastly, a blazed grating is applied (see Figure 2(d)) to tilt the shaped beam and preferentially directs power into the first-order diffraction spot [35]. The first order is then Fourier-filtered (FF), as shown in Figure 1, to eliminate non-diffracted light (in the zero order) and unwanted higher harmonics. Once set up, this holography process may remain static across all datasets and has a negligible impact on processing time.

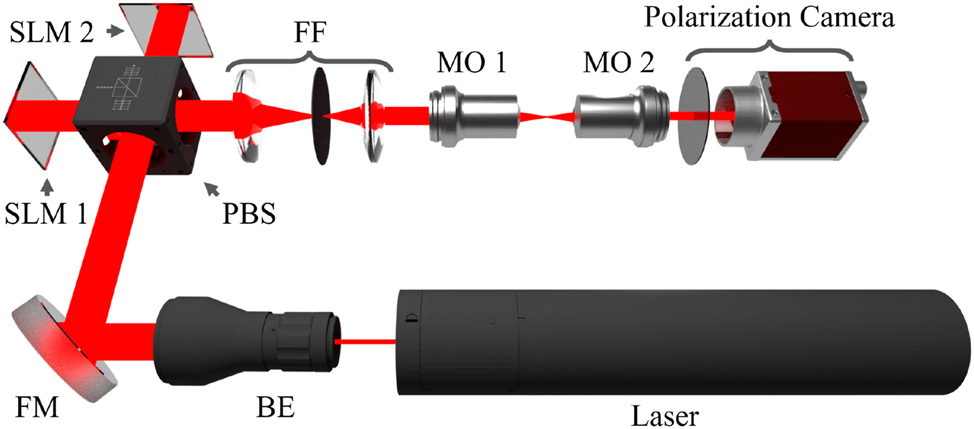

Diagram illustrating the experimental setup used to generate the ARPBs with variable ψ. A diagonally polarized He–Ne laser is first collimated and expanded by a beam expander (BE), then aligned by folding mirrors (FM) before vertical and horizontal polarizations are separated by a polarized beam splitter (PBS) onto two twin spatial light modulators (SLM1 and SLM2). Each SLM dynamically modulates the power and phase of the beam returning through the PBS. Separate calculated phases are applied to the orthogonally polarized beams before recombination at the PBS. The beam is then Fourier filtered (FF), and focused using a 0.25NA objective (MO 1). Polarization imaging is performed with a 0.85NA objective (MO 2) in the focal plane of the ARPB, which is captured using a Kiralux polarization camera. Updating the ARPB with a new value of ψ simply involves displaying holograms generated with the modified transverse electric field components on the SLMs.

Hologram generation process at each step for the separate orthogonal polarization components of an ARPB with ψ = π/2: E x (left), and E y (right); (a) calculated phase and amplitude of ARPB components; (b) conversion of phase to grayscale; (c) addition of amplitude modulation; (d) addition of a blazed grating. The final holograms (d) are displayed on the orthogonal SLMs to shape the beams immediately followed by recombination using a polarized beam splitter to create the final complex wave.

Most commonly, SLMs are used to produce scalar waves with a constant polarization direction. Here, however, we use two SLMs to produce a vectorially shaped beam. The paraxial ARPB is generated using a twin SLM setup illustrated in Figure 1, initially introduced in Ref. [23] to generate obscured bottle beams. This method uses the twin SLMs to holographically control the beam’s transverse field components, E x and E y , separately.

To create such vectorially shaped beams, we first extract the complex field components of the corresponding Jones vector

and then independently convert each component into a hologram. The phases of the E

x

and E

y

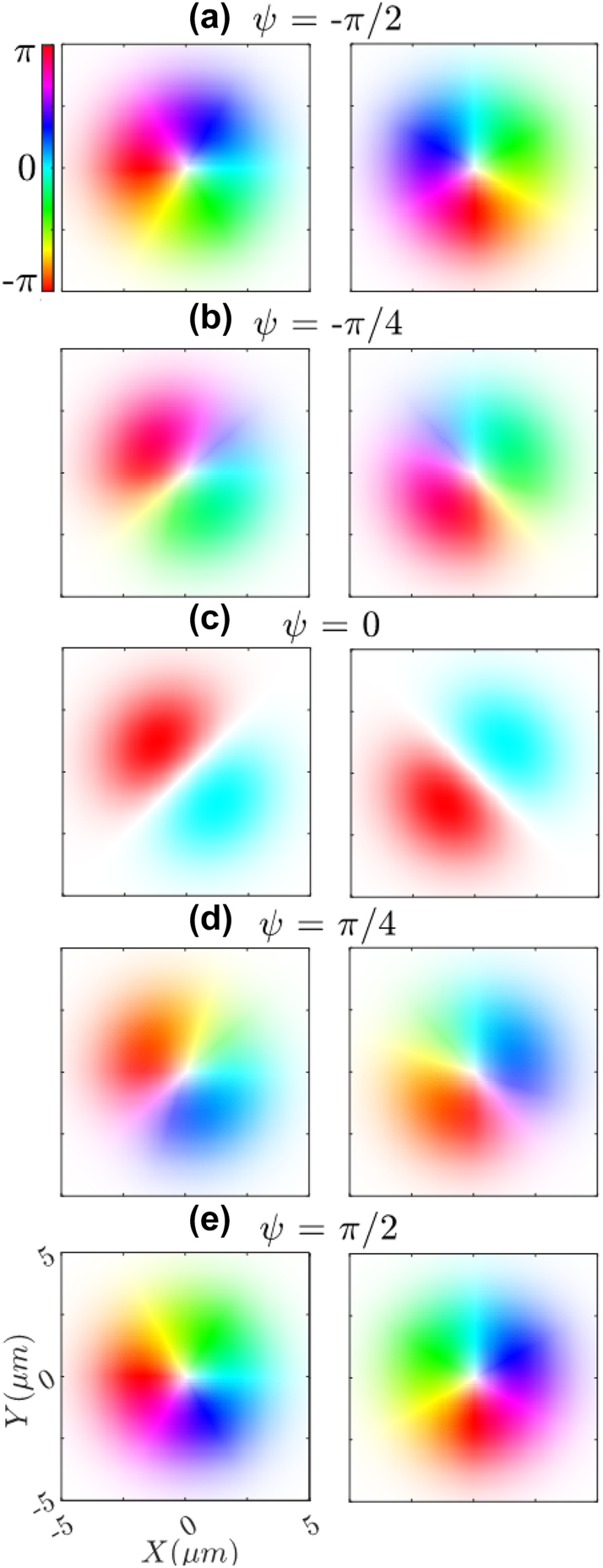

components of an ARPB with ψ ranging from −π/2 to π/2 are shown in the plots of Figure 3. Phases are processed into a hologram and displayed on two corresponding orthogonally aligned SLMs, which are aligned to match the polarization of the field component they display. The SLMs in this configuration provide control of phase and intensity of E

x

and E

y

individually, resulting in control of the local polarization state of the structured beam. The difference in amplitude modulation on each SLM rotates the orientation angle of the polarization according to

Calculated phase for the separate orthogonal polarization components of the ARPB for varying ψ values from −π/2 to π/2: E x (left), and E y (right). The color represents phase and saturation represents the intensity. Comparisons between phase values at a given point on an orthogonal pair reveal the resulting ellipticity upon combination.

In this paper, we produce five different paraxial ARPBs (which are assumed to have (E

z

= 0) under the zeroth-order approximation [37]), with unity relative amplitude

2.3 Helicity and Stokes parameters

For each beam we simultaneously record the intensities I for the horizontal x, vertical y, diagonal d, and anti-diagonal a polarizations by using a polarization-sensitive camera (Thorlabs, Kiralux). These polarizations are at 0°, 90°, 45°, − 45° with respect to the horizontal x axis, respectively. From the polarized intensity measurements we calculate the Stokes parameters S 0, S 1, and S 2 [38], [39], i.e.,

The intensity is defined herein as the squared of the field amplitudes [40], [41], i.e., I = |E|2. Here we define the normalized Stokes parameters as s i = S i /S 0 for i = 1, 2, 3. For monochromatic beams, they are related as [42]

where S

3 = I

LCP

− I

RCP

is the difference between the intensity of left-handed and right-handed CPL, and s

3 = S

3/S

0. Therefore, we can extract the magnitude of the third normalized Stokes parameter

The concept of optimal chirality states that the magnitude of the helicity density h for any kind of monochromatic structured light has the upper bound of u/ω, as demonstrated in Ref. [30]. Therefore, we find it convenient to use the concept of the normalized helicity density

For the ARPB, the normalized helicity density is

and when we use unity relative amplitude,

3 Experimental results

The main result presented herein is the characterization of the magnitude of the third normalized Stokes parameter |s

3| of a paraxial ARPB with unity relative amplitude,

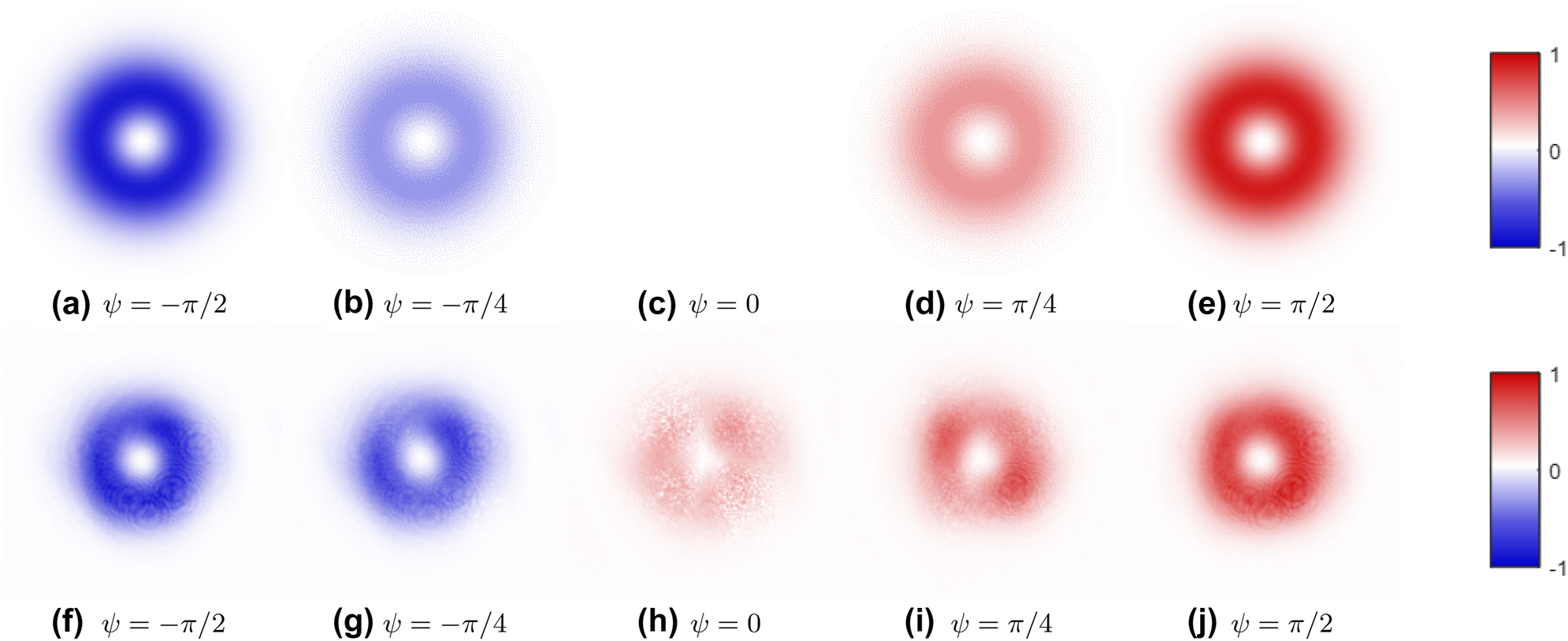

Predicted (above) and experimental (below) third normalized Stokes parameter s

3 on the transverse plane for ARPBs with ψ = −π/2, − π/4, 0, π/4, π/2 (and unity relative amplitude

To confirm that the measured residue for the ψ = 0 ARPB does not indicate a real chirality density in the transverse plane, we add a quarter-wave plate (QWP) with the fast axis on the horizontal (x) axis before the polarization camera in the setup from Figure 1. The QWP transforms left/right-handed circularly polarized light into anti/diagonally polarized light. Therefore, in the new analysis, the normalized helicity density of the paraxial ARPB is proportional to the second normalized Stokes parameter s 2 in the imaging plane. This behavior is depicted in Figure 5, which displays the measured s 2 after a quarter-wave plate (QWP) with the fast axis at 0° for an ARPB with ψ = 0. Indeed, it is shown in Figure 5 that s 2 ≈ 0 on average, and that the residue shown in Figure 4(h) is not indicative of a non-zero helicity density but rather of small anisotropic effects within the optical setup that distort the local polarization of the field. This notion is supported by the fact that the sign of the helicity density of the ARPB is independent of the position (ρ, φ, z) where it is evaluated, as shown in Eq. (7). The measured s 2 after the QWP (equivalent to s 3 without it), however, changes with the position where the field is measured. The ideal ARPB has azimuthal symmetry and the faint residual |s 3|, shown as s 2 after-QWP in Figure 5, does not display. This suggests the residual helicity is due to sub-wavelength curvature imbalance between the two SLMs.

Second normalized Stokes parameters s

2 of an ARPB with

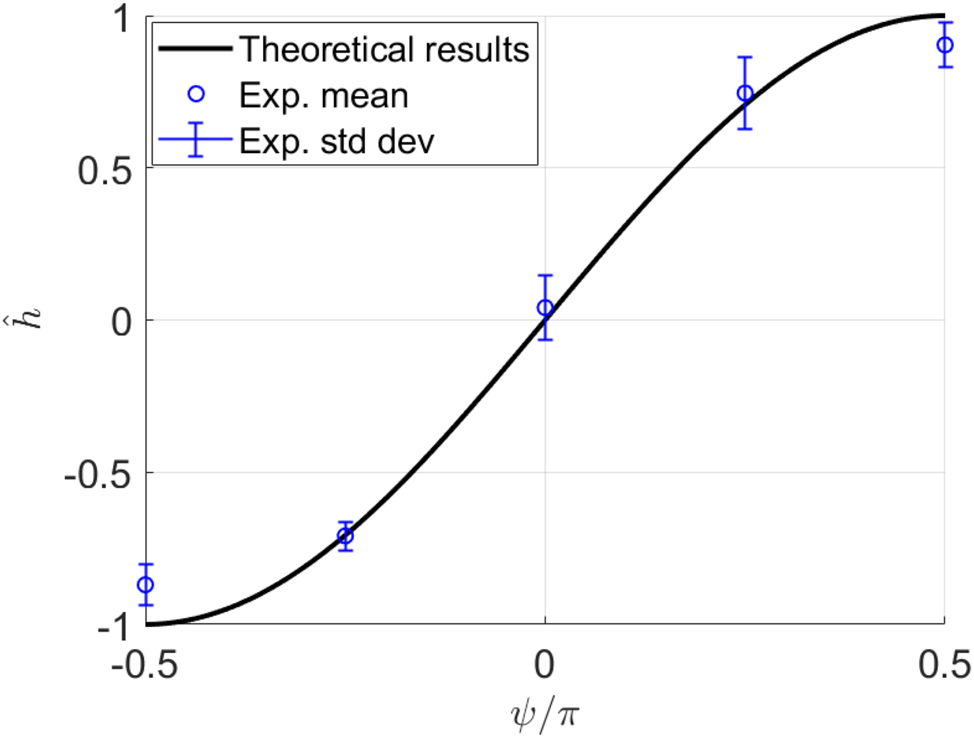

Figure 6 illustrates the relationship between the normalized helicity density

Normalized helicity density

The average of the resulting values of

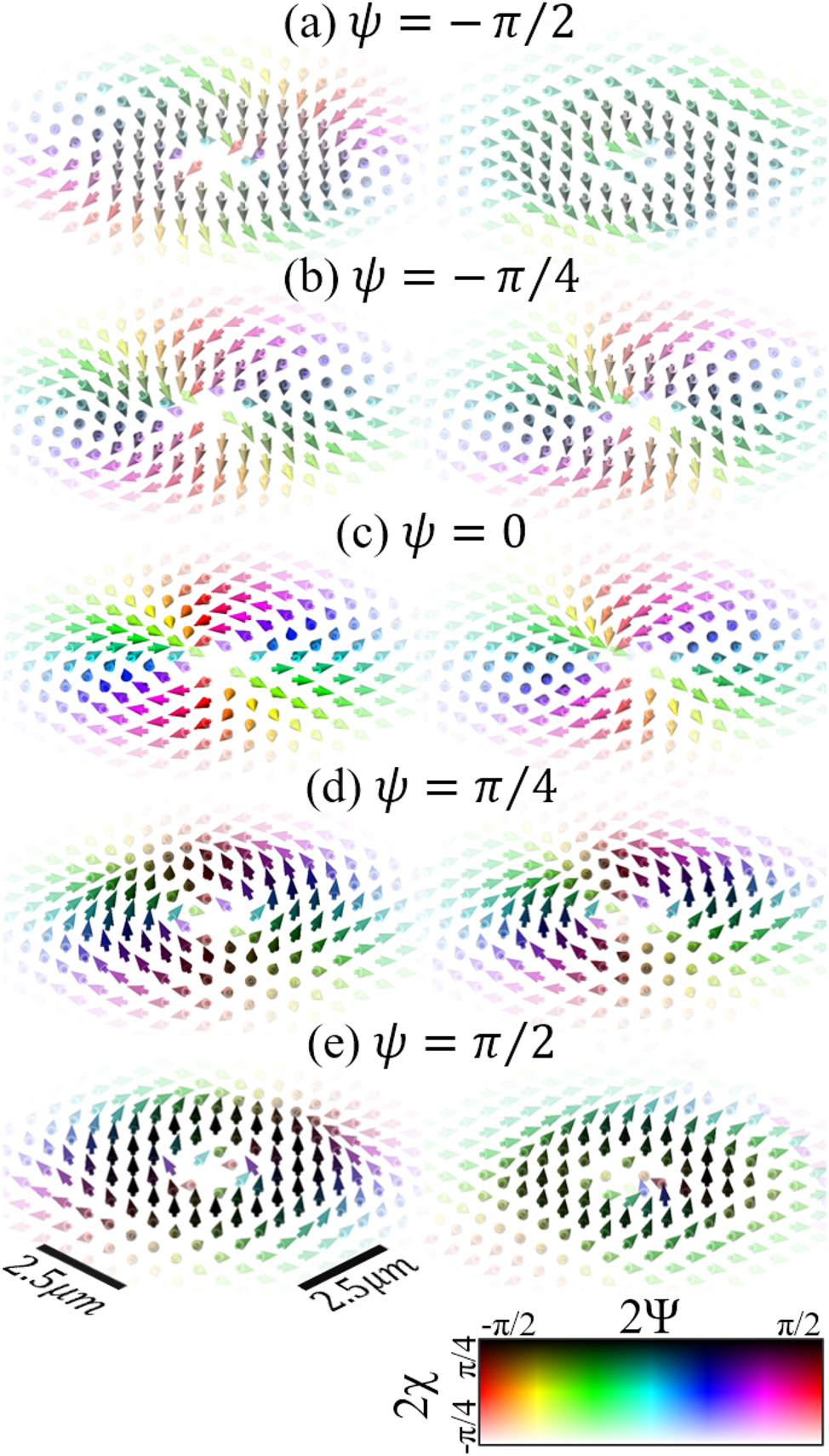

The local polarization of structured light can be visualized using polarization textures where the angle and ellipticity of the electric field at a point are represented by projecting the arrows (normalized) pointing from the center of the Poincaré sphere to the direction of the respective polarization state on the Poincaré sphere. Linear polarization is represented as arrows fully in the x, y plane, circular polarization as arrows on the z axis (so only a dot is visible), and elliptical polarization is represented as arrows outside of the x, y plane (projected arrows are shorter than those representing linear polarization that have full length). These arrows are then plotted at various points in the transverse x, y plane of the beam, revealing the texture. The polarization textures of the implemented ARPBs are shown in Figure 7, with theoretical predictions on the left and experimental results on the right. The figures are organized in pairs with the same value of ψ enclosed in bordered boxes, and arranged vertically in increasing order of ψ, ranging from −π/2 to π/2. We observe that the theoretical OC-ARPBs with ψ = ±π/2, (shown in the left of Figure 7(a) and (e)), exhibit local (left and right, respectively) circular polarization away from the beam edges. As the phase parameter ψ approaches zero, these chiral polarizations transition to linear polarizations. The lack of circularly polarized components for an ARPB with ψ = 0 is proof of its lack of chirality. Indeed, we see that the degree of circular polarization away from the center and edges of the beam reaches a maximum for ARPBs with ψ = ±π/2, and a minimum for ψ = 0. These results reinforce the demonstration of optimally chiral structured light discussed in relation to Figures 4 and 6. By comparing the right and left columns in Figure 7, we can appreciate that the experimental results largely agree with the theoretical predictions, particularly away from the beam edges, where the experimental polarization textures show some variability.

Theoretical (left) and experimental (right) polarization textures of the transverse electric fields at the focus of an ARPB varying the phase parameter ψ. The figures are arranged in order of increasing ψ from −π/2 to π/2. Arrow color represents local position on the Poincaré sphere according to polarization angle 2Ψ (not to be confused with phase parameter ψ seen throughout this paper) and ellipticity 2χ. By varying ψ is possible to change the handedness of the ARPB’s chirality, seen as the circularly polarized regions gradually flip from 2χ = −π/4 in (a), to 2χ = π/4 in (e).

4 Relevant properties of OCL

The results presented in the previous sections are important because they have demonstrated precise control over the helicity density of the ARPB by only tuning the phase parameter ψ. These investigations were conducted under the paraxial approximation [37]. Since the ratio w 0/λ is significantly larger than unity, the longitudinal fields are effectively smaller than the transverse ones in most of the transverse focal plane (see Ref. [43] for details). Furthermore, the measurement setup shown in Figure 1 only distinguishes fields polarized in the transverse plane. Consequently, the excellent agreement between the theoretical and experimental normalized helicity densities shown in Section 3 further validates the use of the paraxial approximation and the neglecting of the longitudinal fields of an ARPB with a large beam waist parameter compared to the wavelength. Here, we expand on this aspect by showing that any field (it does not need to be a beam) that satisfies the optimal chirality condition from Eq. (2) in the transverse plane, i.e., E ⊥ = ±iη 0 H ⊥, is a total OC field. To establish this, we use Maxwell’s equations to derive the expressions for the longitudinal fields in terms of the transverse fields:

Assuming the field exhibits optimal chirality in the transverse plane, i.e., E ⊥ = ±iη 0 H ⊥, and substituting this relationship into Eq. (12), it follows that E z = ±iη 0 H z . The longitudinal fields display the same magnitude ratio and phase shift between the electric and magnetic fields as the transverse fields. This calculation shows that optimal chirality in the transverse plane necessarily extends to the longitudinal direction as well.

For an ARPB, all field components display the same phase shift between the electric and magnetic fields regardless of whether it is optimally chiral. This is observed by following Ref. [16], where the helicity density was decomposed into its component contributions as h = h

ρ

+ h

φ

+ h

z

, where each component is

The parameters A

ρ

, A

z

, B

ρ

, B

z

from Eq. (4) and

Additionally, optimally chiral structured light can be obtained without circular polarization, as it happens for a focused OC-ARPB [16]. Therefore, circular polarization is not a necessary condition for three-dimensional light to be optimally chiral.

Here, we further demonstrate that an optimally chiral beam under the paraxial approximation is necessarily circularly polarized. This latter statement is demonstrated by combining the optimal chirality condition, E = ±iη 0 H, with the Faraday equation, leading to

which is a necessary and sufficient condition to having optimal chiral light [16]. Eq. (14) shows that optimally chiral light has fields that are eigenvectors of the curl operator [17]. Therefore, monochromatic optimally chiral beams are self-dual [15].

For a three-dimensional field, using cartesian coordinates, i.e.,

Under the paraxial approximation,

implying that the field is circularly polarized, i.e., E y = ±iE x , wherein the two transverse components have equal magnitudes and a π/2 phase delay between them. Analogous proof holds for the transverse magnetic field that is also circularly polarized. For paraxial fields whose longitudinal fields are negligible compared to the transverse field components (for intermediate radial distance from the beam axis), the concept of optimally chiral light is equivalent to that of circular polarization on the focal plane, and only for intermediate radial distance as discussed for the ARPB in the next section. However, upon the introduction of structured light with considerable longitudinal fields, optimal chirality can be obtained without circular polarization.

5 Discussion

The presented results not only provide the first experimental analysis and confirmation of the realizability of an optimally chiral structured beam, the OC-ARPB, but also contribute to the limited experimental investigations of self-dual fields. While the primary focus of this paper is not on self-duality, our work aligns with observations in Ref. [17], where monochromatic self-dual electromagnetic fields are identified as eigenvectors of the curl operator.

The experiments described in this work demonstrate precise control over the helicity density of the ARPB via the tuning of the phase parameter ψ, following the relation

Additionally, we have been able to verify the local polarization of the paraxial ARPBs on the transverse plane with the polarization textures shown in Figure 7. The paraxial OC-ARPBs (i.e., when ψ = ±π/2 and

Here, we further observe from Eq. (4) that for OC-ARPBs with a large waist relative to the wavelength (w 0 ≫ λ) on the focal plane z = 0, one has A ρ ≈ 1 and B ρ = 0, resulting in circular polarization in the transverse plane. Note that however when ρ ≫ w 0, then A ρ is not close to unity anymore. Therefore we do not have circular polarization at the edges of the beam, as shown in Figure 7 in both theory and experiment.

Additionally, the transverse circular polarization of paraxial OC-ARPB is also lost near the beam axis. This result is appreciated in Figure 7(a), where the local polarization of the theoretical OC-ARPB becomes elliptical near the beam axis. When ρ ≪ w

0, the longitudinal fields cannot be neglected. This occurs when the term A

z

is no longer much less than kρA

ρ

at z = 0. Consequently, near the beam axis

In summary, while circular polarization is a sufficient condition to attain optimal chirality, it is not a necessary one since a focused OC-ARPB displays optimal chirality without circular polarization. Even when the OC-ARPB has a large beam waist (w 0 ≫ λ), it still displays optimal chirality without circular polarization near the axis and far away from it.

Our investigation has directly verified the optimal chirality of the paraxial OC-ARPB with

6 Conclusions

We have successfully generated an ARPB using a versatile optical setup with two SLMs employing orthogonal polarizations (x and y). By adjusting the phase parameter ψ, we demonstrated the ability to manipulate the chirality density of the ARPB across its full range of possible values. Notably, we found that the paraxial ARPB can achieve optimal chirality for ψ = ±π/2, showcasing the existence of optimally chiral structured light.

While the experiments realized herein are restricted to the transverse plane, we have also theoretically shown that three-dimensional fields whose transverse components satisfy the optimal chirality condition are optimally chiral in all directions. Additionally, we have demonstrated that circular polarization is a sufficient but not necessary condition for structured fields to be optimally chiral, and that it is equivalent to the concept of optimal chirality only under the paraxial approximation and when the longitudinal fields are negligible compared to the transverse field components. We found that the local polarization of the OC-ARPB is circular away from the center or edges of the beam. In those regions, the local circular polarization is lost even though optimal chirality is maintained.

Additionally, we have shown that monochromatic optimally chiral fields are self-dual since their electric and magnetic fields are the eigenvectors of the curl operator, leading to maximal chirality density among other self-dual electromagnetic features. The OC-ARPB generated in this work represents an example of a structured self-dual monochromatic beam, of which few have been studied experimentally.

Importantly, the results of this study verify the first practical implementation of an OC structured beam, of which the OC-ARPB is only a specific example. This new tool provides unprecedented control over fundamental chiral light–matter interactions, with future applications of enhanced sensing and manipulation of chiral particles. Given the ubiquity and importance of chirality in biology, the development of precise tools to characterize and control chiral molecules is of supreme importance in the field of biophotonics and single-isomer drug discovery. The ability to dynamically control the helicity density of the ARPB allows for the innovative design of dynamic, enantioselective optical traps. Considering the importance of the polarization of the chiral field components on light–matter interactions, future research might explore chirality of non-paraxial ARPBs on the beam axis, which is solely attributed to the chiral longitudinal fields.

Funding source: Congressionally Directed Medical Research Programs

Award Identifier / Grant number: 225135

Acknowledgments

We would acknowledge fruitful discussions with professor Federico Capasso, and we are grateful for his contributions that inspired our work on optimal chirality as a means to maximize chirality-discriminating forces.

-

Research funding: We would like to thank the Beckman Laser Institute Foundation and the Department of Defense (DOD Grant No. 225135) for funding this research.

-

Author contributions: AHP: conceptualization, methodology, software, formal analysis, investigation, writing original draft preparation. NP: methodology, software, validation, investigation, resources, writing original draft preparation. FC: conceptualization, formal analysis, writing review and editing, supervision. DP: conceptualization, methodology, resources, writing review and editing, supervision, and project administration. All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and consented to its submission to the journal, reviewed all the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflicts of interest.

-

Data availability: The data underlying the results presented in this paper are not publicly available at this time but may be obtained from the authors upon reasonable request.

Section A: Proof of equivalency between the normalized helicity density and the degree of circular polarization for paraxial beams

Under the paraxial approximation, we neglect the small longitudinal z components of the electric and magnetic fields [37], [46], i.e., E ≈ E ⊥ and H ≈ H ⊥. The transverse electromagnetic fields of a generic paraxial beam are of the form

where m = E

y

/E

x

and

and the time-average helicity density is [10]

Substituting the fields from Eq. (A.1) into Eqs. (A.2) and (A.3), we obtain

Note that this last expression is not a good approximation for tightly focused beams where the longitudinal components are not negligible. In terms of the fields from Eq. (A.1), the normalized Stokes parameters are [24], [47]

For monochromatic beams,

References

[1] K. A. Forbes and D. Green, “Enantioselective optical gradient forces using 3D structured vortex light,” Opt. Commun., vol. 515, p. 128197, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optcom.2022.128197.Search in Google Scholar

[2] C. Rosales-Guzman, K. Volke-Sepulveda, and J. P. Torres, “Light with enhanced optical chirality,” Opt. Lett., vol. 37, pp. 3486–3488, 2012, https://doi.org/10.1364/ol.37.003486.Search in Google Scholar

[3] K. A. Forbes and D. Green, “Customized optical chirality of vortex structured light through state and degree-of-polarization control,” Phys. Rev. A, vol. 107, p. 063504, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1103/physreva.107.063504.Search in Google Scholar

[4] L. D. Barron, “True and false chirality and absolute enantioselection,” Rend. Lincei.-Sci. Fis. Nat., vol. 24, pp. 179–189, 2013, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12210-013-0224-6.Search in Google Scholar

[5] A. Lininger, et al.., “Chirality in light–matter interaction,” Adv. Mater., vol. 35, p. 2107325, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.202107325.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] F. Alpeggiani, K. Y. Bliokh, F. Nori, and L. Kuipers, “Electromagnetic helicity in complex media,” Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 120, p. 243605, 2018, https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevlett.120.243605.Search in Google Scholar

[7] L. V. Poulikakos, J. A. Dionne, and A. García-Etxarri, “Optical helicity and optical chirality in free space and in the presence of matter,” Symmetry, vol. 11, no. 9, 2019, https://doi.org/10.3390/sym11091113.Search in Google Scholar

[8] K. A. Forbes, “Optical helicity of unpolarized light,” Phys. Rev. A, vol. 105, p. 023524, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1103/physreva.105.023524.Search in Google Scholar

[9] R. P. Cameron, S. M. Barnett, and A. M. Yao, “Optical helicity, optical spin and related quantities in electromagnetic theory,” New J. Phys., vol. 14, p. 053050, 2012, https://doi.org/10.1088/1367-2630/14/5/053050.Search in Google Scholar

[10] M. Hanifeh, M. Albooyeh, and F. Capolino, “Optimally chiral light: upper bound of helicity density of structured light for chirality detection of matter at nanoscale,” ACS Photonics, vol. 7, pp. 2682–2691, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1021/acsphotonics.0c00304.Search in Google Scholar

[11] L. Fang and J. Wang, “Optical trapping separation of chiral nanoparticles by subwavelength slot waveguides,” Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 127, p. 233902, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevlett.127.233902.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[12] O. V. Angelsky, A. Y. Bekshaev, S. G. Hanson, C. Y. Zenkova, I. I. Mokhun, and Z. Jun, “Structured light: ideas and concepts,” Front. Phys., vol. 8, pp. 1–26, 2020, https://doi.org/10.3389/fphy.2020.00114.Search in Google Scholar

[13] K. Y. Bliokh, A. Y. Bekshaev, and F. Nori, “Dual electromagnetism: helicity, spin, momentum and angular momentum,” New J. Phys., vol. 15, p. 033026, 2013, https://doi.org/10.1088/1367-2630/15/3/033026.Search in Google Scholar

[14] I. Fernandez-Corbaton and G. Molina-Terriza, Introduction to Helicity and Electromagnetic Duality Transformations in Optics, ch. 11, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2015, pp. 341–362.10.1002/9781119009719.ch11Search in Google Scholar

[15] J. Lekner, “Chirality of self-dual electromagnetic beams,” J. Opt., vol. 21, p. 035402, 2019, https://doi.org/10.1088/2040-8986/ab026f.Search in Google Scholar

[16] A. Herrero-Parareda and F. Capolino, “The combination of the azimuthally and radially polarized beams: helicity and momentum densities, generation, and optimal chiral light,” Adv. Photonics Res., vol. 5, p. 2300265, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1002/adpr.202300265.Search in Google Scholar

[17] J. Lekner, “Self-dual electromagnetic fields,” Proc. R. Soc. A: Math., Phys. Eng. Sci., vol. 480, p. 20230657, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1098/rspa.2023.0657.Search in Google Scholar

[18] A. Herrero-Parareda and F. Capolino, “Optimally chiral optical trapping,” in Optical Trapping and Optical Micromanipulation XX, K. Dholakia and G. C. Spalding, eds., San Diego, International Society for Optics and Photonics, SPIE, 2023, vol. 12649, p. 126490G.10.1117/12.2678180Search in Google Scholar

[19] G. Tkachenko and E. Brasselet, “Helicity-dependent three-dimensional optical trapping of chiral microparticles,” Nat. Commun., vol. 5, p. 4491, 2014, https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms5491.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[20] D. S. Bradshaw, K. A. Forbes, J. M. Leeder, and D. L. Andrews, “Chirality in optical trapping and optical binding,” Photonics, vol. 2, pp. 483–497, 2015, https://doi.org/10.3390/photonics2020483.Search in Google Scholar

[21] T. Zhang, et al.., “All-optical chirality-sensitive sorting via reversible lateral forces in interference fields,” Acs Nano, vol. 11, pp. 4292–4300, 2017, https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.7b01428.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[22] M. Li, S. Yan, Y. Zhang, P. Zhang, and B. Yao, “Enantioselective optical trapping of chiral nanoparticles by tightly focused vector beams,” J. Opt. Soc. Am. B-Opt. Phys., vol. 36, pp. 2099–2105, 2019, https://doi.org/10.1364/josab.36.002099.Search in Google Scholar

[23] N. Perez and D. Preece, “Enhanced optical vector bottle beams with obscured nodal surfaces,” Opt. Express, vol. 32, pp. 14010–14017, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1364/oe.516742.Search in Google Scholar

[24] A. Hayat, J. P. B. Mueller, and F. Capasso, “Lateral chirality-sorting optical forces,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A., vol. 112, pp. 13190–13194, 2015, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1516704112.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[25] J. Mun and J. Rho, “Importance of higher-order multipole transitions on chiral nearfield interactions,” Nanophotonics, vol. 8, no. 5, pp. 941–948, 2019, https://doi.org/10.1515/nanoph-2019-0046.Search in Google Scholar

[26] D. Cojoc, S. Cabrini, E. Ferrari, R. Malureanu, M. Danailov, and E. Di Fabrizio, “Dynamic multiple optical trapping by means of diffractive optical elements,” Microelectron. Eng., vols. 73–74, pp. 927–932, 2004, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0167-9317(04)00246-1.Search in Google Scholar

[27] J. S. Bennett, et al.., “Spatially-resolved rotational microrheology with an optically-trapped sphere,” Sci. Rep., vol. 3, p. 1759, 2013, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep01759.Search in Google Scholar

[28] M. Kamandi, et al.., “Unscrambling structured chirality with structured light at the nanoscale using photoinduced force,” ACS Photonics, vol. 5, pp. 4360–4370, 2018, https://doi.org/10.1021/acsphotonics.8b00765.Search in Google Scholar

[29] M. Hanifeh and F. Capolino, “Helicity maximization in a planar array of achiral high-density dielectric nanoparticles,” J. Appl. Phys., vol. 127, p. 093104, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.5138600.Search in Google Scholar

[30] M. Hanifeh, M. Albooyeh, and F. Capolino, “Helicity maximization below the diffraction limit,” Phys. Rev. B, vol. 102, p. 165419, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.102.165419.Search in Google Scholar

[31] M. Hanifeh and F. Capolino, “Theory of vector beams for chirality and magnetism detection of subwavelength particles,” in Electromagnetic Vortices, ch. 13, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2021, pp. 401–421.10.1002/9781119662945.ch13Search in Google Scholar

[32] J. S. Eismann, M. Neugebauer, and P. Banzer, “Exciting a chiral dipole moment in an achiral nanostructure,” Optica, vol. 5, pp. 954–959, 2018, https://doi.org/10.1364/optica.5.000954.Search in Google Scholar

[33] R. N. Kumar, J. K. Nayak, S. D. Gupta, N. Ghosh, and A. Banerjee, “Probing dual asymmetric transverse spin angular momentum in tightly focused vector beams in optical tweezers,” Laser Photonics Rev., vol. 18, p. 2300189, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1002/lpor.202300189.Search in Google Scholar

[34] A. B. Stilgoe, A. V. Kashchuk, D. Preece, and H. Rubinsztein-Dunlop, “An interpretation and guide to single-pass beam shaping methods using slms and dmds,” J. Opt., vol. 18, p. 065609, 2016, https://doi.org/10.1088/2040-8978/18/6/065609.Search in Google Scholar

[35] J. Liesener, M. Reicherter, T. Haist, and H. Tiziani, “Multi-functional optical tweezers using computer-generated holograms,” Opt. Commun., vol. 185, pp. 77–82, 2000, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0030-4018(00)00990-1.Search in Google Scholar

[36] D. Preece, S. Keen, E. Botvinick, R. Bowman, M. Padgett, and J. Leach, “Independent polarisation control of multiple optical traps,” Opt. Express, vol. 16, pp. 15897–15902, 2008, https://doi.org/10.1364/oe.16.015897.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[37] M. Lax, W. H. Louisell, and W. B. McKnight, “From Maxwell to paraxial wave optics,” Phys. Rev. A, vol. 11, pp. 1365–1370, 1975, https://doi.org/10.1103/physreva.11.1365.Search in Google Scholar

[38] W. H. McMaster, “Polarization and the Stokes parameters,” Am. J. Phys., vol. 22, pp. 351–362, 1954, https://doi.org/10.1119/1.1933744.Search in Google Scholar

[39] H. G. Berry, G. Gabrielse, and A. E. Livingston, “Measurement of the Stokes parameters of light,” Appl. Opt., vol. 16, pp. 3200–3205, 1977, https://doi.org/10.1364/ao.16.003200.Search in Google Scholar

[40] I. Fatadin, D. Ives, and M. Wicks, “Accurate magnified near-field measurement of optical waveguides using a calibrated ccd camera,” J. Lightwave Technol., vol. 24, pp. 5067–5074, 2006, https://doi.org/10.1109/jlt.2006.885748.Search in Google Scholar

[41] R. Hui and M. O’Sullivan, “Basic instrumentation for optical measurement,” in Fiber Optic Measurement Techniques,ch. 2, R. Hui, and M. O’Sullivan, Eds., Boston, Academic Press, 2009, pp. 129–258.10.1016/B978-0-12-373865-3.00002-1Search in Google Scholar

[42] M. Born and E. Wolf, “Basic properties of the electromagnetic field,” in Principles of Optics: Electromagnetic Theory of Propagation, Interference and Diffraction of Light, ch. 1, Cambridge University Press, 1999, pp. 1–6.10.1017/CBO9781139644181.010Search in Google Scholar

[43] M. Veysi, C. Guclu, and F. Capolino, “Focused azimuthally polarized vector beam and spatial magnetic resolution below the diffraction limit,” J. Opt. Soc. Am. B-Opt. Phys., vol. 33, pp. 2265–2277, 2016, https://doi.org/10.1364/josab.33.002265.Search in Google Scholar

[44] C. P. Jisha and A. Alberucci, “Paraxial light beams in structured anisotropic media,” J. Opt. Soc. Am. A: Opt., Image Sci., Vision, vol. 34, pp. 2019–2024, 2017, https://doi.org/10.1364/josaa.34.002019.Search in Google Scholar

[45] H. Moosmüller and W. P. Arnott, “Particle optics in the Rayleigh regime,” J. Air Waste Manage. Assoc., vol. 59, no. 9, pp. 1028–1031, 2009, https://doi.org/10.3155/1047-3289.59.9.1028.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[46] K. Y. Bliokh and F. Nori, “Transverse and longitudinal angular momenta of light,” Phys. Rep., vol. 592, pp. 1–38, 2015, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physrep.2015.06.003.Search in Google Scholar

[47] K. Y. Bliokh, A. Y. Bekshaev, and F. Nori, “Extraordinary momentum and spin in evanescent waves,” Nat. Commun., vol. 5, p. 3300, 2014, https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms4300.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- In honor of Federico Capasso, a visionary in nanophotonics, on the occasion of his 75th birthday

- Reviews

- Flat nonlinear optics with intersubband polaritonic metasurfaces

- Polaritonic quantum matter

- Machine-learning-assisted photonic device development: a multiscale approach from theory to characterization

- Perspectives

- Towards field-resolved visible microscopy of 2D materials

- Perspective on tailoring longitudinal structured beam and its applications

- Tunable holographic metasurfaces for augmented and virtual reality

- Polarization-sensitive diffractive optics and metasurfaces: “Past is Prologue”

- Compound meta-optics: there is plenty of room at the top

- Nonlocal metasurfaces: universal modal maps governed by a nonlocal generalized Snell’s law

- Resonant metasurface-enabled quantum light sources for single-photon emission and entangled photon-pair generation

- Active metasurface designs for lensless and detector-limited imaging

- Letter

- Real-time tuning of plasmonic nanogap cavity resonances through solvent environments

- Research Articles

- On the generalized Snell–Descartes laws, shock waves, water wakes, and Cherenkov radiation

- Silicon rich nitride: a platform for controllable structural colors

- Overcoming stress limitations in SiN nonlinear photonics via a bilayer waveguide

- High-harmonic generation from subwavelength silicon films

- Space-time wedges

- XUV yield optimization of two-color high-order harmonic generation in gases

- Skyrmion bag robustness in plasmonic bilayer and trilayer moiré superlattices

- Quantum-enhanced detection of viral cDNA via luminescence resonance energy transfer using upconversion and gold nanoparticles

- Deep neural networks for inverse design of multimode integrated gratings with simultaneous amplitude and phase control

- Topological chiral-gain in a Berry dipole material

- Diagnostic oriented discrimination of different Shiga toxins via PCA-assisted SERS-based plasmonic metasurface

- Quantum emitter interacting with a dispersive dielectric object: a model based on the modified Langevin noise formalism

- 3D-printed mirror-less helicity preserving metasurface “mirror” for THz applications

- Supershift properties for nonanalytic signals

- Enhancing radiative heat transfer with meta-atomic displacement

- Quasi-bound states in the continuum in finite waveguide grating couplers

- Long lived surface plasmons on the interface of a metal and a photonic time-crystal

- Tailoring propagation-invariant topology of optical skyrmions with dielectric metasurfaces

- Experimental generation of optimally chiral azimuthally-radially polarized beams

- Tailoring optical response of MXene thin films

- Nonlinear analog processing with anisotropic nonlinear films

- Optical levitation of Janus particles within focused cylindrical vector beams

- Large tuning of the optical properties of nanoscale NdNiO3 via electron doping

- Combining quantum cascade lasers and plasmonic metasurfaces to monitor de novo lipogenesis with vibrational contrast microscopy

- Monoclinic nonlinear metasurfaces for resonant engineering of polarization states

- Non-linear bistability in pulsed optical traps

- Tutorial: Hong–Ou–Mandel interference with structured photons

- Inhomogeneous broadening in the time domain

- MoS2 based 2D material photodetector array with high pixel density

- Temporal interface in dispersive hyperbolic media

- Measurement of the cavity dispersion in quantum cascade lasers using subthreshold luminescence

- Designing the response-spectra of microwave metasurfaces: theory and experiments

- Exciton–polariton condensation in MAPbI3 films from bound states in the continuum metasurfaces

- Experimental analysis of the thermal management and internal quantum efficiency of terahertz quantum cascade laser harmonic frequency combs

- Energy-efficient thermally smart windows with tunable properties across the near- and mid-infrared ranges

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- In honor of Federico Capasso, a visionary in nanophotonics, on the occasion of his 75th birthday

- Reviews

- Flat nonlinear optics with intersubband polaritonic metasurfaces

- Polaritonic quantum matter

- Machine-learning-assisted photonic device development: a multiscale approach from theory to characterization

- Perspectives

- Towards field-resolved visible microscopy of 2D materials

- Perspective on tailoring longitudinal structured beam and its applications

- Tunable holographic metasurfaces for augmented and virtual reality

- Polarization-sensitive diffractive optics and metasurfaces: “Past is Prologue”

- Compound meta-optics: there is plenty of room at the top

- Nonlocal metasurfaces: universal modal maps governed by a nonlocal generalized Snell’s law

- Resonant metasurface-enabled quantum light sources for single-photon emission and entangled photon-pair generation

- Active metasurface designs for lensless and detector-limited imaging

- Letter

- Real-time tuning of plasmonic nanogap cavity resonances through solvent environments

- Research Articles

- On the generalized Snell–Descartes laws, shock waves, water wakes, and Cherenkov radiation

- Silicon rich nitride: a platform for controllable structural colors

- Overcoming stress limitations in SiN nonlinear photonics via a bilayer waveguide

- High-harmonic generation from subwavelength silicon films

- Space-time wedges

- XUV yield optimization of two-color high-order harmonic generation in gases

- Skyrmion bag robustness in plasmonic bilayer and trilayer moiré superlattices

- Quantum-enhanced detection of viral cDNA via luminescence resonance energy transfer using upconversion and gold nanoparticles

- Deep neural networks for inverse design of multimode integrated gratings with simultaneous amplitude and phase control

- Topological chiral-gain in a Berry dipole material

- Diagnostic oriented discrimination of different Shiga toxins via PCA-assisted SERS-based plasmonic metasurface

- Quantum emitter interacting with a dispersive dielectric object: a model based on the modified Langevin noise formalism

- 3D-printed mirror-less helicity preserving metasurface “mirror” for THz applications

- Supershift properties for nonanalytic signals

- Enhancing radiative heat transfer with meta-atomic displacement

- Quasi-bound states in the continuum in finite waveguide grating couplers

- Long lived surface plasmons on the interface of a metal and a photonic time-crystal

- Tailoring propagation-invariant topology of optical skyrmions with dielectric metasurfaces

- Experimental generation of optimally chiral azimuthally-radially polarized beams

- Tailoring optical response of MXene thin films

- Nonlinear analog processing with anisotropic nonlinear films

- Optical levitation of Janus particles within focused cylindrical vector beams

- Large tuning of the optical properties of nanoscale NdNiO3 via electron doping

- Combining quantum cascade lasers and plasmonic metasurfaces to monitor de novo lipogenesis with vibrational contrast microscopy

- Monoclinic nonlinear metasurfaces for resonant engineering of polarization states

- Non-linear bistability in pulsed optical traps

- Tutorial: Hong–Ou–Mandel interference with structured photons

- Inhomogeneous broadening in the time domain

- MoS2 based 2D material photodetector array with high pixel density

- Temporal interface in dispersive hyperbolic media

- Measurement of the cavity dispersion in quantum cascade lasers using subthreshold luminescence

- Designing the response-spectra of microwave metasurfaces: theory and experiments

- Exciton–polariton condensation in MAPbI3 films from bound states in the continuum metasurfaces

- Experimental analysis of the thermal management and internal quantum efficiency of terahertz quantum cascade laser harmonic frequency combs

- Energy-efficient thermally smart windows with tunable properties across the near- and mid-infrared ranges