Abstract

The concept of obtaining uniform and high-precision 3D models of large and complex engineering structures based on terrestrial laser scanning surveys highly depends on the accuracy of registering a series of adjacent scans. If it is not possible to place the required number of reference points in the observation scene, and there are no identifiable structural elements that could serve as such reference points, the issue can be solved by using the virtual reference points. The virtual reference points are not marked, but their position can be re-created in the post-processing of the scans on the basis of the geometrical features of the object. In the case of an industrial chimney, these can be the structural axis points determined at arbitrarily selected altitudes. In the solution presented herein, the coordinates of the reference points were independently determined twice: in the geodetic coordinate system using traditional method, in the local system of the scanner using the bisector of the chord of the circle, and by approximation of the circular arc shape of the chimney shell. Both procedures are preceded by the filtration of outliers. The concept of virtual reference points was verified by the measurement of the verticality of the axis and the structural geometry of a steel industrial chimney, which was accessible only on the foundation level.

1 Introduction

The evolution of scanning technology (TLS), we have seen in recent years, has made this method not only more and more eagerly used in broad-based engineering, but in many applications has given it a leading role [1]. Among its advantages, one should definitely point out the ease and speed of use (up to 1 million points per second); precision (up to mm level accuracy) with a high point density, non-invasive, and remote character of the measurement (also in very low light conditions); and the possibility of remote operation (especially important in life-threatening or health-endangering conditions). All these contribute to the fact that the TLS technique is now applied in as built surveys of buildings and structures for the purpose of documentation of their existing condition and checking compliance with the project [1,2,3,4]; creating the precise 3D models of structures of various types for design purposes [5]; documenting historical objects [6,7]; or destruction, deformation, and monitoring of engineering constructions and excavations [3,6,8,9,10,11,12]; surveying of tunnels and rail tracks [13]; calculating volumes; applying building information modeling (BIM) [1,2]; monitoring the stability of the earth’s structures [14]; and geotechnical and geological mapping in mining.

From the engineering surveying perspective, one of the most interesting features of this technology is the possibility of obtaining a full model of the surveyed structure [3,9,10]. This contributes to the ability to perform advanced analyses (determination of cross-sections, geometry, volume or displacements and deformations over time) [3,12] as well as to obtain the desired information on the properties or state of an object at any point, not just at selected spots [2,3,9].

Making uniform and precise 3D models for large and complex building structures always involves the necessity of acquiring adjacent scans from multiple locations. As a consequence, we face the problem of proper registration of individual scanning images, which has been widely discussed in many publications [2,8,15,16,17].

Tall structures are a special case of constructions in the aspect of registering scans and determining their spatial location [12,18]. Most often available only from the ground level, without the possibility of implementing targets at the top as well as identification of structural elements that can replace them. As a result, it makes it impossible to create a proper 3D model with the assumed internal accuracy. This publication presents the analysis and solution of this problem through the use of virtual reference points. The method is discussed on a practical example of scanning of an industrial chimney in order to examine its condition and geometry.

The verticality of the industrial chimney axis is usually analysed by measuring the directions of the tangents to the circular sections of the structure. This method is accurate and, depending on the number of stations, makes it possible to assess the deformation of the structure [19]. However, it is only efficient for small portions of the chimney shell. The laser scanning technology is free of such limitations. The advantages of the scanning technology are less obvious in view of the conditions and properties of prismless distance measurements and in particular the issue of precise orientation of the point clouds [16,20].

The use of laser scanning technology for chimney geometry analysis has been widely discussed in the literature of the subject [18,21,22,23,24,25]. The analyses of the shape and verticality are usually conducted on processed data, i.e. on combined point clouds. The analysis consists of visual [22] or analytical alignment of the equation of the circle [18,24] or ellipse for point bands isolated from point clouds. The cloud registration stage is usually omitted.

In the analyses of tall structures, the issue of cloud registration requires particular attention. In each case, the reference points should be distributed throughout the measurement space and projected on individual scans [18,21,25]. With the “cloud-to-cloud” method, the quality of the final effect is determined by the size of the overlapping areas. Curvatures of the chimney sections limit both the choice of reference points and the common areas.

As a device similar in structure and mode of operation to total station, the terrestrial laser scanner is susceptible to similar errors. Instrument errors, levelling errors, unfavourable angles of reflection of the laser beam, and the type of the reflective surface disrupt the uniformity of data accuracy. This impact grows with the height of the scanned structure. In the case of an industrial chimney, this becomes a significant issue due to additional conditions of the structure, namely:

the reference points cannot be placed evenly across the structure; as a result, the scans are correctly aligned only on the foundation level,

scanning is performed from a number of adjacent stations usually located in highly developed areas,

the chimney shell lacks details which could be used as reference points and

In the currently used solutions, the axes are determined by aligning the circles with the point clouds which represent the entire or a substantial section of the chimney’s circumference [18,21,27]. For structures with small diameters, correct registration is conditional upon the large number of scanner stations.

In consideration of the above, the authors propose that the reference points can be replaced or supported with virtual reference points. These are not installed on the structure surface and are not physically present in the measurement space. Their coordinates can be determined on the basis of the geometrical properties of the structure or a segment thereof. In the case of the industrial chimney, the natural choice is the axis points located on specific levels. Solving the task requires determining the coordinates of the chimney axis in the local point cloud system and in the geodetic coordinate system. The former is performed using the scan point approximation method and the latter by geodetic method used for analysing slender structures. The same point is determined in the scanner’s local system on the basis of the curvature of the chimney shell captured on the scan. The resulting pairs of points serve as the basis for the spatial transformation which adjusts less accurate results of interpretation of scanned images to much more precise traditional measurements. The elements of the structure’s surroundings are ignored when the scanned images are registered.

In the event of an analysis of single scans covering only small sections of the arch, filtration of outliers and the approximation method are crucial. In the processing of scanned images, the curvature is determined with the assumption that the analysed sections of the chimney shell are circular sectors. In this context, the outcome of alignment of conventional observations of the control network points is an important input. The determined mean errors and the error ellipse of the circle centre coordinates indicate the importance of the irregularity of the circular shape on specific levels.

2 Characteristics of the structure and the measurement works

The proposed method of using virtual reference points was verified by the measurement of an industrial chimney located in Kielce Power Station. The steel chimney is 80 m high and has the diameter of 0.90–1.40 m. It was commissioned in 2016. The chimney is operated year-round and discharges the flue gas from the biomass boiler. Chimney renovations are performed outside the heating season. The structure has a uniform steel colour and is composed of eight segments joined with bolts. Access to the chimney is difficult due to the extensive infrastructure of the power station, such as belt conveyors, internal traffic routes and biomass storage yards (Figure 1).

Object of measurement.

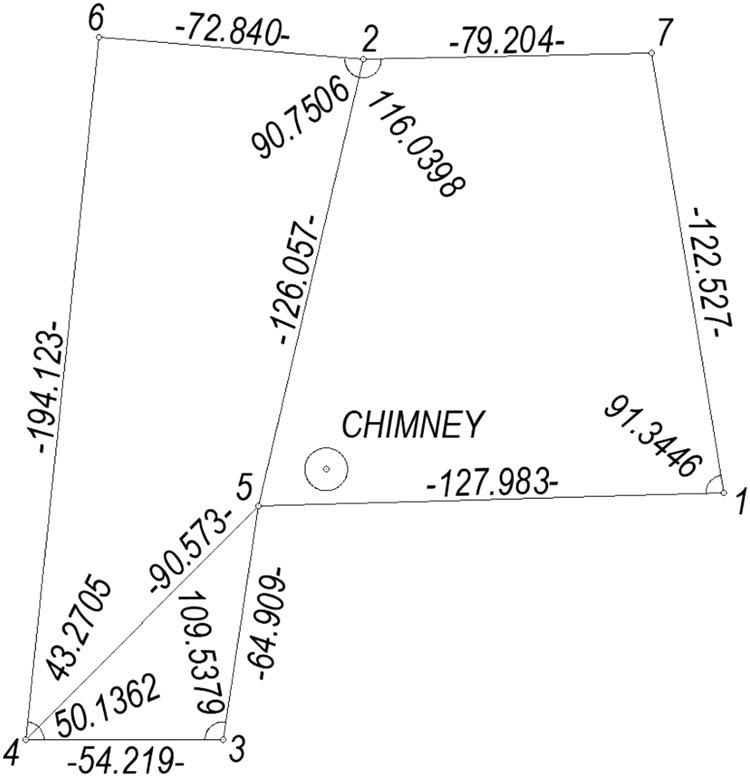

The measurement was performed on seven levels of the chimney using the method of tangent directions from four measurement control stations (Figure 2). The measurement was performed using a Topcon GPT-3007N total station (mk = 7″, md = 2 + 2 mm). The angular and linear observations were adjusted using the least square method in the local coordinate system. The coordinates of the control points and their mean errors are summarized in Table 1. Scanning was performed with a TLS Stonex X300 scanner, with the range of 300 m, scan rate of 40,000 points/sec, and the distance measurement error md = 0.02–0.04 m. The origins of the individual scans were determined using a GNSS SOKKIA GRX1 receiver and Real Time Kinematic (RTK) method, with the accuracy of 0.02 m horizontally and 0.05 m vertically which was comparable to the conventional measurement results (ca. 0.02 m). Direct measurement of the above-mentioned coordinates was made possible with a dedicated Stonex mount adapter.

Angular–linear control network on which the measurement with ambient tangents was based.

Coordinates of the control points and the chimney centres

| Station no. | Survey control network | Chimney axis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X [m] | Y [m] | mp [m] | Level | X [m] | Y [m] | mp [m] | |

| 1 | 67.774 | 191.840 | 0.012 | A | 74.351 | 82.507 | 0.007 |

| 2 | 186.919 | 92.647 | 0.007 | B | 74.336 | 82.511 | 0.007 |

| 3 | 0.000 | 54.219 | 0.008 | C | 74.322 | 82.529 | 0.007 |

| 4 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | D | 74.314 | 82.537 | 0.007 |

| 5 | 64.182 | 63.908 | 0.010 | E | 74.302 | 82.545 | 0.007 |

| 6 | 193.083 | 20.069 | 0.010 | F | 74.307 | 82.543 | 0.007 |

| 7 | 188.657 | 171.832 | 0.011 | G | 74.352 | 82.531 | 0.007 |

Scanning was performed on five stations: stations 1–5 (of which four were eventually used to build the final model) were located in the immediate vicinity of the structure. The reference points were marked by 10 scanning targets distributed on the ground around the structure.

3 The outcome of registering scanned images using reference points located on the foundation level of the structure

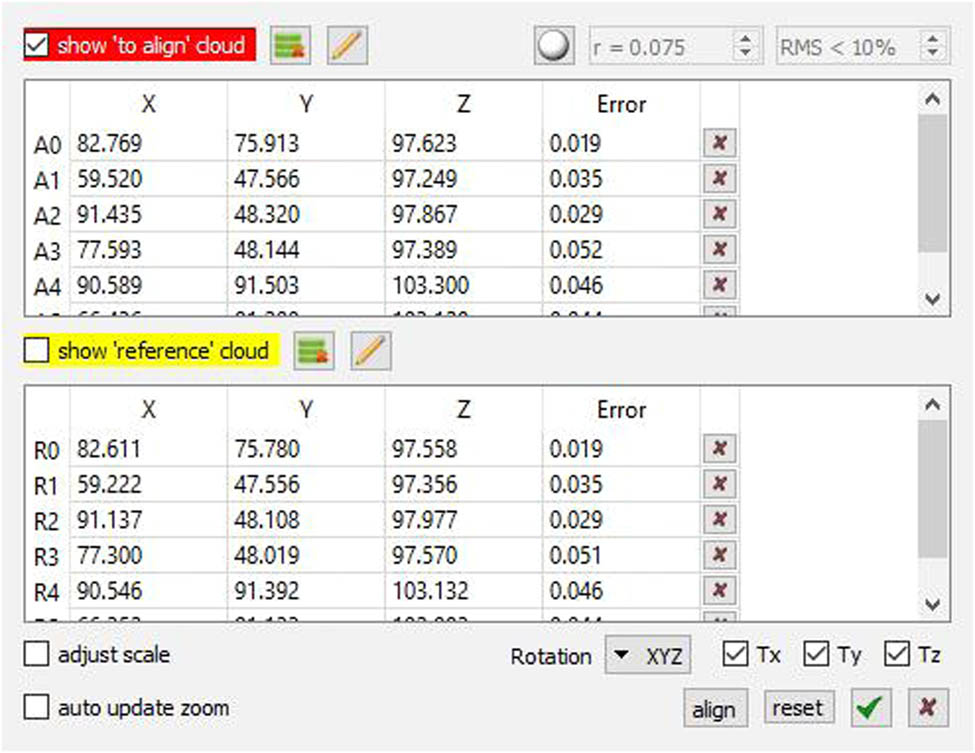

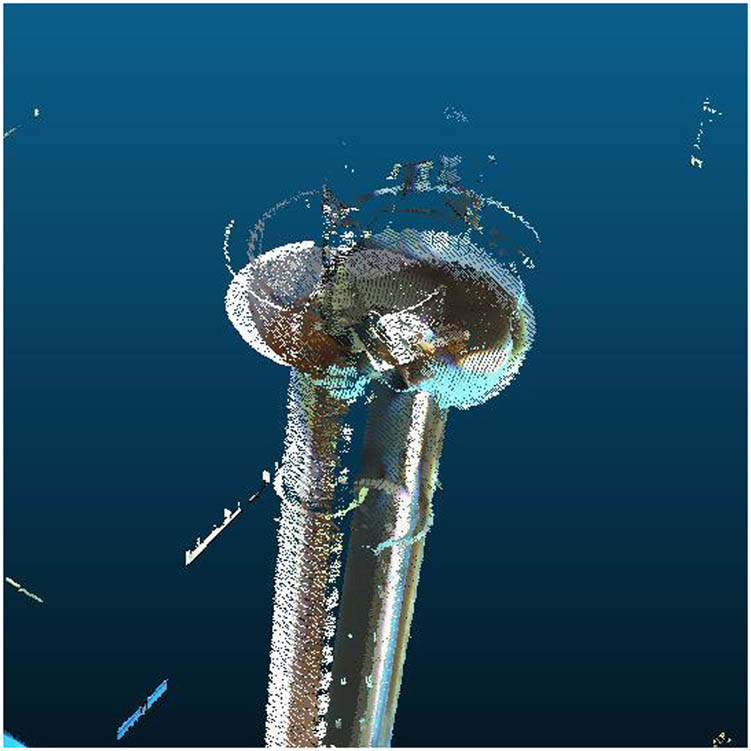

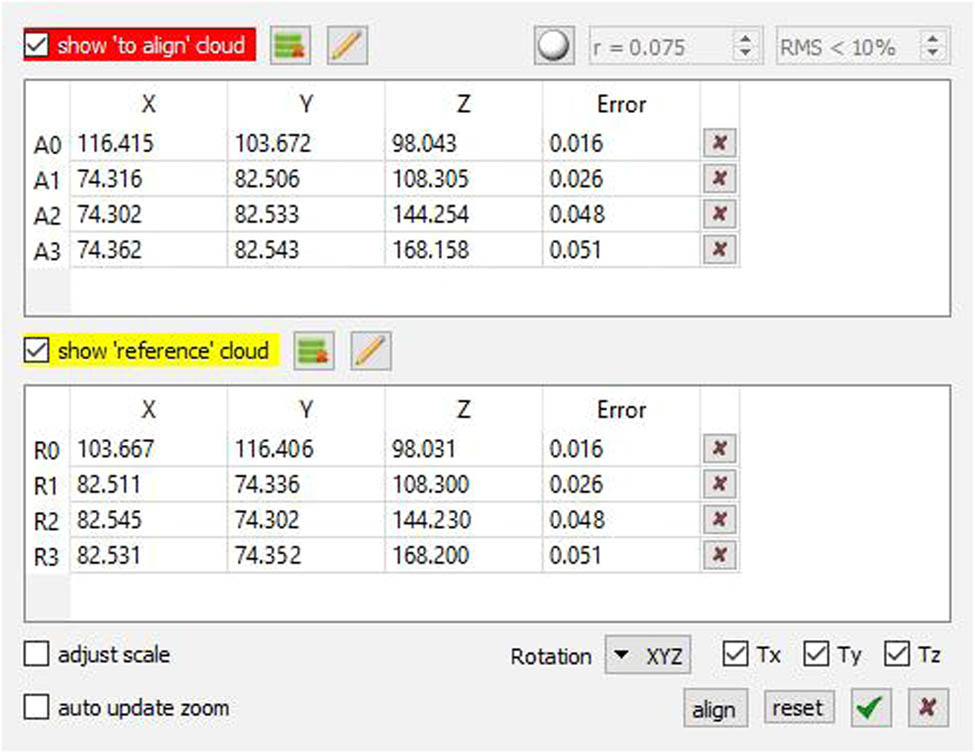

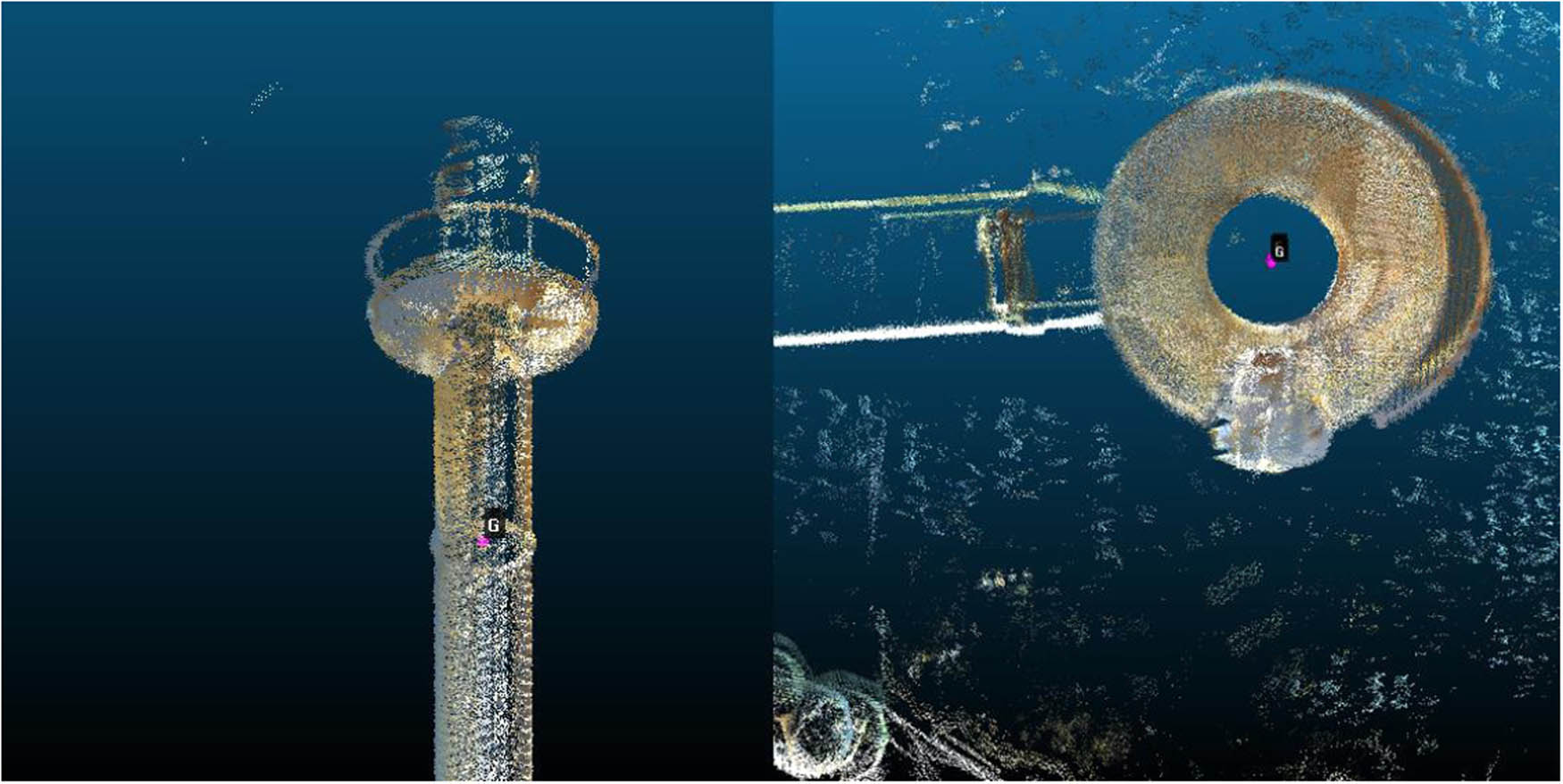

The point clouds were processed in CloudCompare software using the reference points. The resulting structure model is correct but only at the foundation level of the structure. This is confirmed by minor errors of coordinates of the tie points which were determined on the basis of the spatial transformation outcomes (Figure 3). The outcome of registration on top of the chimney is unacceptable even by visual assessment (Figure 4).

Example of registration of scanned images.

The outcome of registration of scanned images on the top of the chimney.

As expected, installing the reference targets on the foundation level of the structure in its nearest vicinity failed to produce the desired results. According to the conclusions of the study [12], the system of reference targets should form an irregular spatial solid with the span comparable to the size of the structure which, in the case presented, was impossible to meet due to the highly developed surroundings. The error of the showcased outcome model, which increases with height can, however, be eliminated by using virtual reference points.

4 Virtual reference points

In the task discussed herein, it was assumed that the scanned images would be registered using virtual reference points determined on B, E, and G levels and the scanned image origins, as determined by RTK-GPS (scanner stations). The calculations were performed in the local coordinate system. According to the proposed virtual reference point method, the following steps should be taken when processing the point clouds:

filter out the reference points which do not represent a circular section and

determine the coordinates of circle centres separately for each section.

The need to filter out outliers arises from the fact that some of the points do not actually represent the analysed structure [6]. Those points appear as a result of the laser beam’s reflection from other objects, of approaching the angular threshold of measurement, of the changes in the chimney surface albedo, or the local imperfections of the structure. In the example presented herein, filtering out was performed using robust statistics. Outlier points, which were not located on the chimney surface, were identified and rejected if the radius value calculated on their basis exceeded 5 cm.

The circle centres were determined separately for each section following the selection of the set. It should be noted that each of the analysed sets applies to a single scanned image, i.e. covers a small section of the arch. The size of the arch decreases with the chimney diameter, i.e. with the increasing altitude of the analysed section and also the angular threshold of measurement. In the presented example, the impact of the latter made it necessary to discard points located on the edges of the scanned image. The task was solved using the method of approximation of the circle equation.

The centre of the circular arch was determined using two methods. The first one was based on the least squares approximation of data. However, when applying the least squares method, it should be borne in mind that this method is susceptible to gross errors. Significant outliers distort the result of the analysis, with high outlier values eliminating the correct results from the set. It should also be noted in this context that the emergence of outliers in the point clouds is a specific feature of the scanning technology.

The chimney axis points were determined by aligning the circle with the cloud points for 10 cm wide bands. The result of the approximation was the determination of the coordinates of the circle centre x0, y0, and the radius R in the equation:

In the observation equations,

the approximate values of vector

The results of the circle centres approximation are provided in Table 2. The demonstrated differences in radiuses, as determined in independent approximation processes, are minor. Their order of magnitude coincides with the measurement accuracy characteristic for the scanner used (Stonex X300).

The results of the approximations of circle centres on the scanned images acquired from four scanning sites

| Scanned image | Top (level G) | Middle (level E) | Bottom (level B) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Station 1 | R | 0.881 | 0.867 | 1.424 |

| X | 4.717 | 5.010 | 5.381 | |

| Y | 44.995 | 45.640 | 46.530 | |

| Z | 71.303 | 47.409 | 11.474 | |

| Station 2 | R | 0.887 | 0.880 | — |

| X | 36.023 | 35.434 | — | |

| Y | –25.894 | –26.207 | — | |

| Z | 70.473 | 46.552 | — | |

| Station 3 | R | 0.910 | 0.911 | 1.418 |

| X | –32.747 | –32.263 | –31.647 | |

| Y | 20.464 | 20.909 | 21.370 | |

| Z | 69.918 | 45.915 | 9.982 | |

| Station 4 | R | 0.893 | 0.886 | 1.420 |

| X | –29.172 | –28.704 | –28.061 | |

| Y | 40.299 | 40.540 | 40.884 | |

| Z | 66.286 | 42.319 | 6.403 |

The differences in radii determined in the independent approximation processes are small, which proves the correctness of the method. High conformity also indicates that the structure sections are regular.

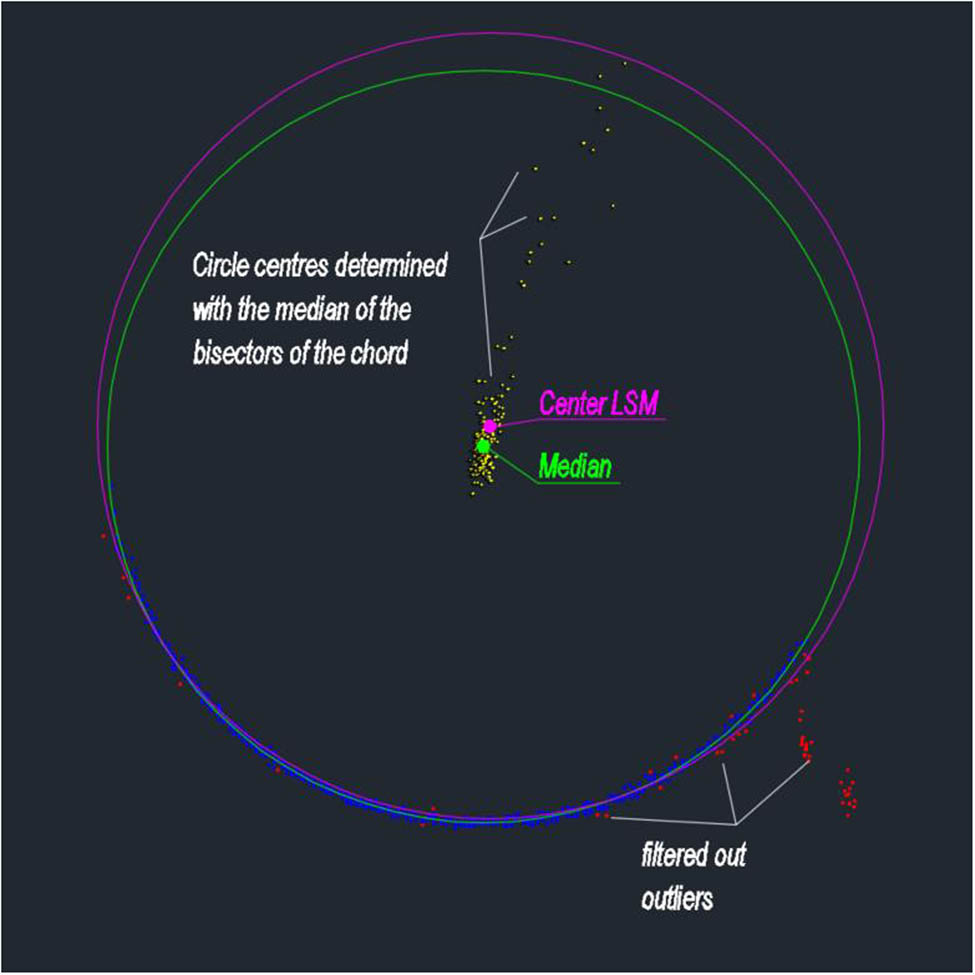

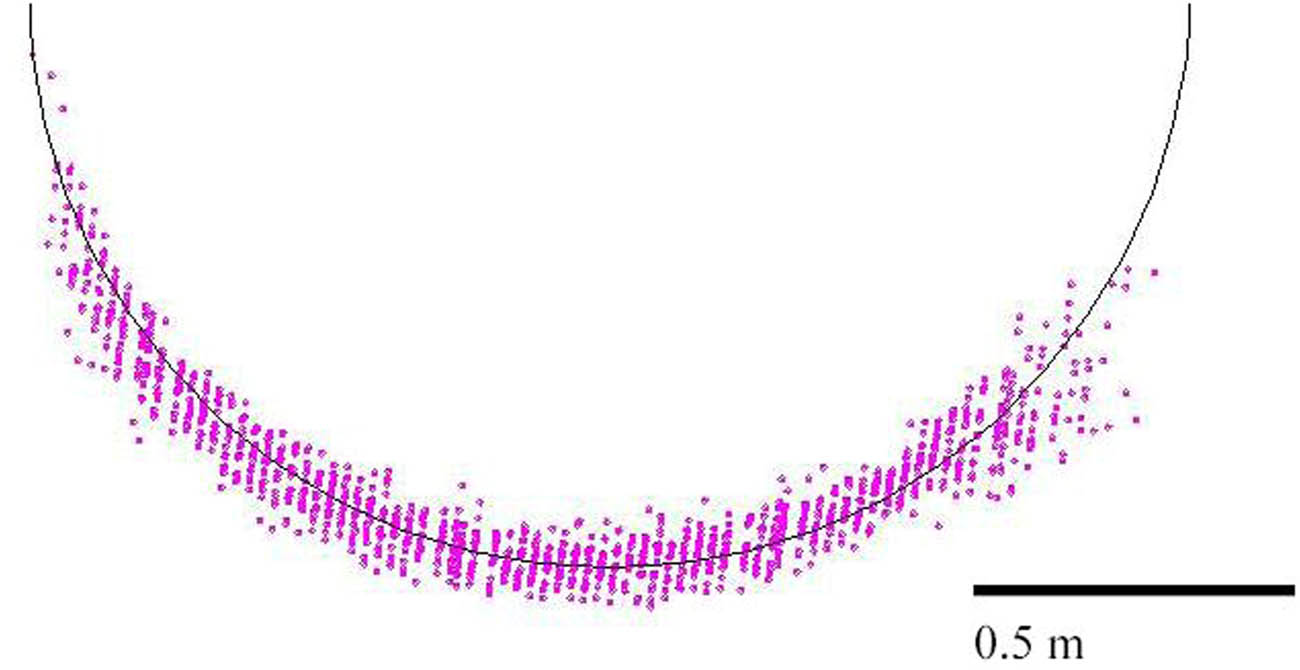

The second method of processing the scanning results was based on determining the population of circle centres using the method of intersection of bisectors of the chords based on three points. The points were selected to ensure that the distance between them is approximately one third of the length of the arc of the circle projected on a single scanned image, as shown in Figure 5. This assumption reduced the analysed set of circle centres to one third of all points. The coordinates of the central point were determined as the median of the population of coordinates of circle centres. One of the advantages of this method is the property of the median which is more resistant to outliers. The circle radius was determined in a similar way, i.e. as the median of the distance of individual cloud points from the central point. The set was filtered by eliminating the points for which the determined radius differed from the median by more than 5 cm.

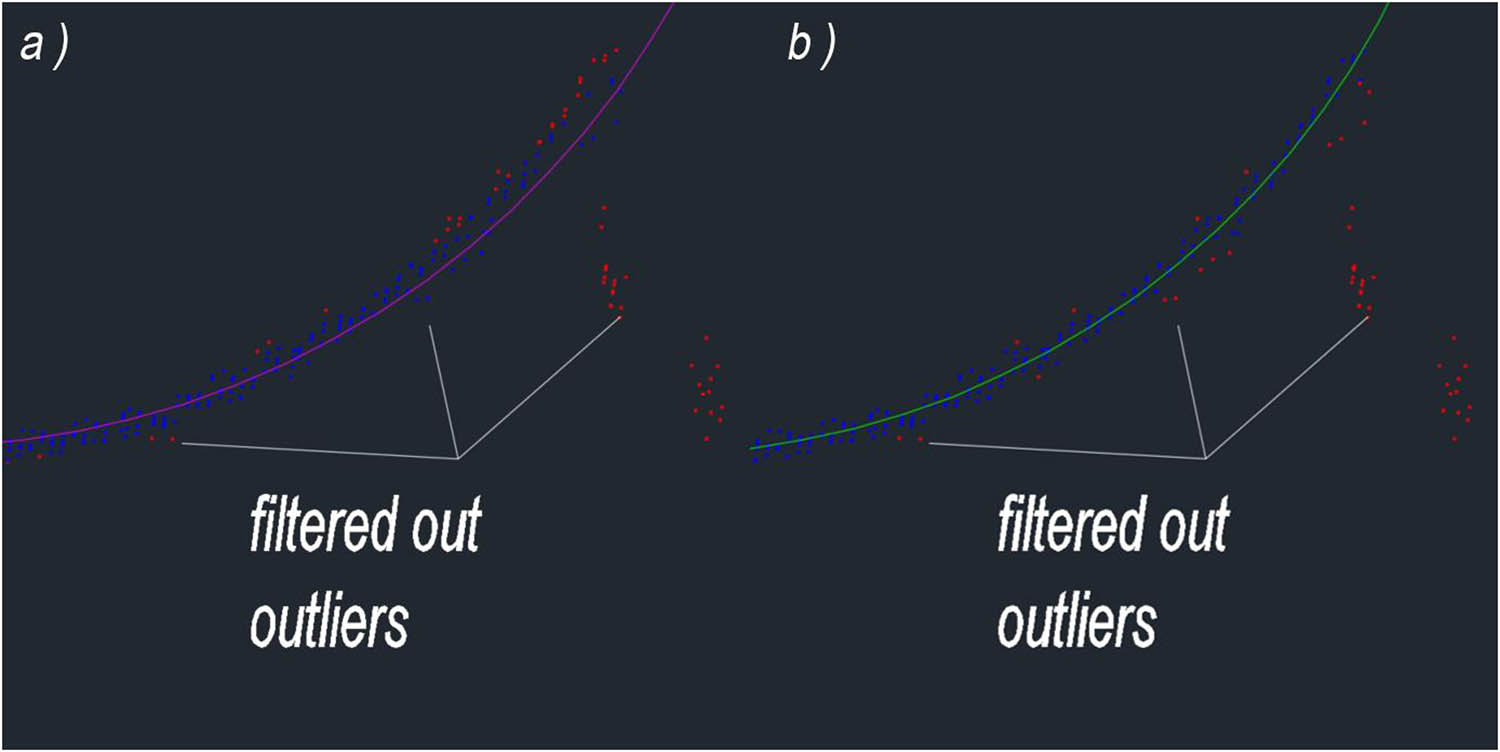

Circle centres determined with two methods.

The outcome of filtration of outliers, as shown in Figures 5 and 6, indicates that the method based on the median of bisectors of the chord yields slightly better results than least squares approximation of the circle. On the basis of the results presented in Table 3, it is not possible to unequivocally determine which of the applied chimney centre approximation methods is more beneficial, although the least squares method shows a lower value of errors. The largest difference in coordinates of the circle centre (5 cm) was observed in the highest level of the structure (level G). The cause of the increased RMSE error value was most likely the unfavourable scanning angle, which was close to the threshold limit, and the lower cloud resolution. The solution to this problem is extending the width of the band, however, this is not ideal too due to the potential impact of [20]:

deviation in the verticality of the chimney axis,

the setting up of the scanner or the operation of the compensator; the measurement is affected by collimation and inclination errors and

conical geometry of the chimney shell.

The results of point filtration (a) with the median of the bisectors of the chord and (b) by the least squares method.

Results of approximation of the chimney centre using approximation method and intersection of bisectors method

| Scanned image no. | Approximation method | Intersection of bisectors method | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R | X | Y | RMSE | R | X | Y | RMSE | |

| Station 1 level B | 1.424 | 5.381 | 46.530 | 0.004 | 1.414 | 5.379 | 46.503 | 0.006 |

| Station 3 level B | 1.418 | –31.647 | 21.370 | 0.004 | 1.411 | –31.640 | 21.364 | 0.008 |

| Station 4 level B | 1.420 | –28.061 | 40.884 | 0.003 | 1.405 | –28.058 | 40.872 | 0.007 |

| Station 5 level B | 1.409 | 25.856 | –0.147 | 0.003 | 1.396 | 25.837 | –0.145 | 0.005 |

| Station 1 level E | 0.867 | 5.010 | 45.640 | 0.007 | 0.883 | 5.000 | 45.662 | 0.016 |

| Station 3 level E | 0.911 | –32.263 | 20.909 | 0.007 | 0.932 | –32.280 | 20.923 | 0.017 |

| Station 4 level E | 0.886 | –28.704 | 40.540 | 0.012 | 0.867 | –28.687 | 40.527 | 0.021 |

| Station 5 level E | 0.882 | 26.395 | 0.250 | 0.011 | 0.892 | 26.406 | 0.246 | 0.020 |

| Station 1 level G | 0.881 | 4.717 | 44.995 | 0.017 | 0.886 | 4.716 | 44.991 | 0.031 |

| Station 3 level G | 0.910 | –32.747 | 20.464 | 0.010 | 0.867 | –32.701 | 20.433 | 0.032 |

| Station 4 level G | 0.893 | –29.172 | 40.299 | 0.150 | 0.863 | –29.132 | 40.273 | 0.310 |

The impact of the first two factors can be seen in Figure 7, which shows the point cloud of a 1 m wide band projected on a horizontal plane.

Plan view of the cloud points – the inclination of the chimney shell image is visible.

In general, point clouds should be approximated by the lateral surface of the cylinder. For chimneys with a simpler structure, as in the case at hand, the surface of a cylinder with axis conforming to Oz axis is described by the equation:

Since the results of the measurement are saved in the local coordinate system of the scanner, aligning the cylinder side wall requires transforming the coordinates of the cloud points. The transformation involves the following:

moving the starting point of the local coordinates system (scanner) to the central point of the axis of the approximated cylinder at the base level and

making two turns around Ox and Oy axes.

The transformation was performed using the following formulas:

where x, y, and z – coordinates in the local system of the scanner; X, Y, and Z – transformed coordinates.

α – angle of rotation around axis Ox, β – angle of rotation around axis Oy, and x0 and y0 – coordinates of the vector of the coordinates system translation.

Cylinder surface area equation:

after linearization

was used to approximate the cylinder surface area using the least squares method. The results of the analysis of the 1 m wide bands are summarized in Table 4.

Results of approximation of point cloud bands with cylinder surface area

| No. | Radius | X [m] | Y [m] | Z [m] | α [g] | β [g] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Station 1 level G | Value | 0.889 | 4.733 | 44.971 | 71.200 | –1.7988 | –0.6751 |

| RMSE | 0.004 | 0.001 | 0.005 | 0.0984 | 0.1729 | ||

| Station 2 level G | Value | 0.861 | 35.954 | –25.863 | 70.420 | 0.6713 | 0.8043 |

| RMSE | 0.005 | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.1108 | 0.1148 | ||

| Station 3 level G | Value | 0.853 | –32.673 | 20.416 | 69.912 | –1.3736 | –1.4356 |

| RMSE | 0.005 | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.1136 | 0.0931 | ||

| Station 4 level G | Value | 0.898 | –29.158 | 40.264 | 66.286 | –0.5982 | –1.4208 |

| RMSE | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.0534 | 0.0622 | ||

5 Verification of the applied methods

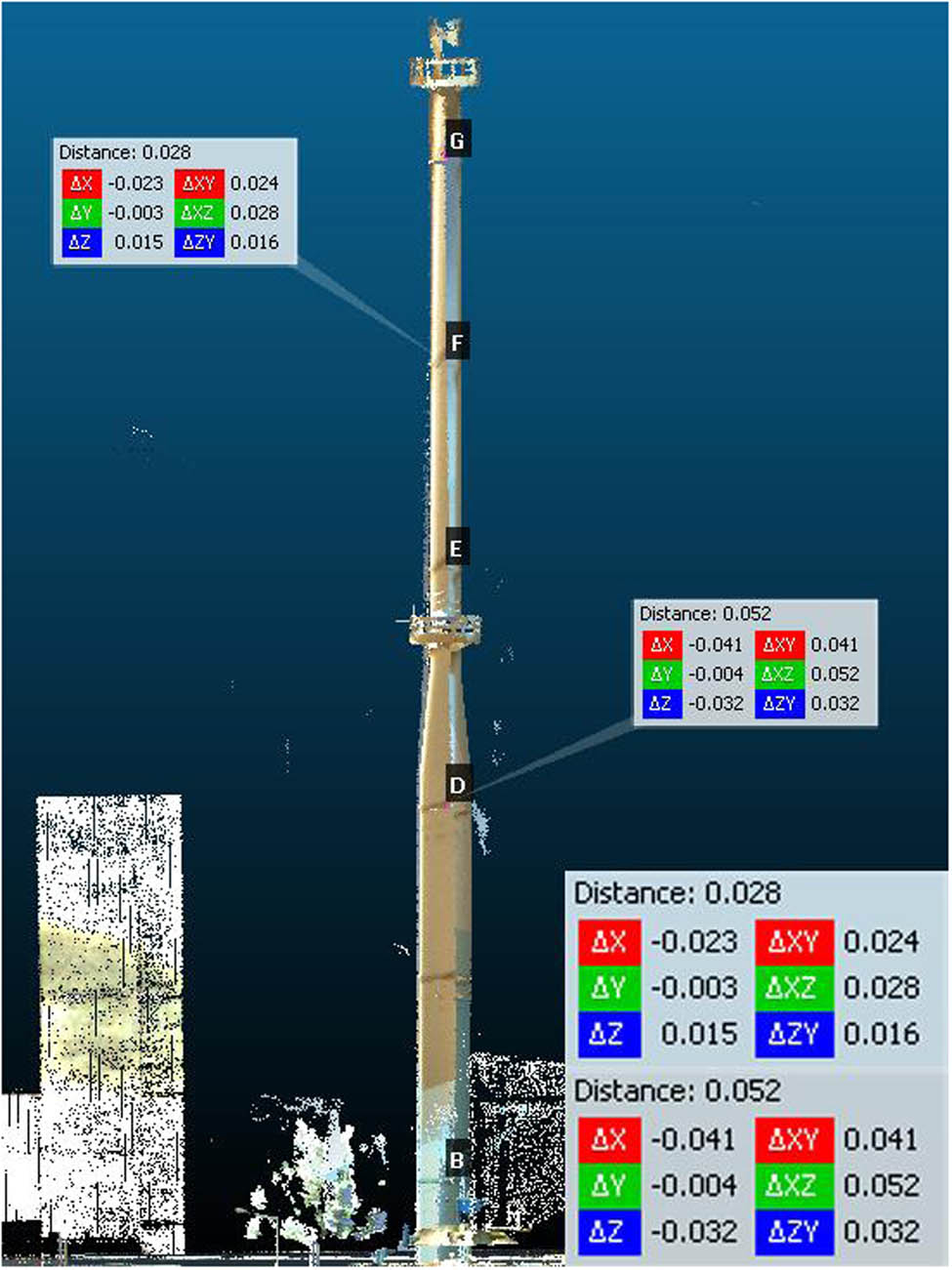

The applied method was verified by cloud orientation and demonstrated transformation errors – in this particular case, distributed across the vertical profile of the model (Figure 8).

Example of registration of point clouds using the virtual reference points.

An objective measure of efficiency is also provided by comparing the measurements of the chimney axis with the results of conventional measurements.

The applied measurement method was verified on levels D and F which had not been included in the transformation task. The differences between the values of the virtual coordinates acquired by conventional method and scanning method fall within the range of 0.03–0.06 m. The deviations correspond to the accuracies obtained for the reference points used for proper registration of point clouds (Figure 10).

Examples of check point errors.

The individual scans, once registered using the virtual reference points, correctly project the shape of the structure. The axis of generated model differs from the axis determined by the conventional method within the error margins typical of the equipment used. Scanning provides additional information on the condition and shape of the chimney shell.

6 Discussion

The dynamic development of measuring instruments and methods in the TLS area has contributed to the fact that we are using this method in newer and newer applications and also in the field of high-precision engineering surveying. However, very advanced accuracy parameters of the devices themselves do not guarantee uniform and correct 3D models of large and complex structures. They usually require multisite observations carried out in very unfavourable spatial and environmental conditions. It is necessary to merge the acquired data sets supplemented with accuracy analysis. The issue of registration of scan sets and their spatial orientation is widely discussed in literature [2,12,16]. It may seem that nowadays this problem has been solved or significantly minimized. There are, however, objects for which the standard, developed methods do not succeed. A good example is the tall objects, especially those located in a highly urbanized environment, which prevents proper spatial distribution of reference points necessary to perform a registration of high precision.

The proposed method of virtual reference points, in the case of an industrial chimney, proves to solve this problem. In the authors’ opinion, it can be used for all structures with circular and elliptical cross-sections for cylindrical, spherical, or conical surfaces. Not only for tall constructions, but in an industrial environment saturated with pipe installations as well (i.e. mining oil and gas industry).

The possibilities of developing the method of virtual reference points are to be found in several areas. The most significant is the creation of algorithms that give the possibility of implementation in specialized software (i.e. CloudCompare freeware software), which could significantly speed up and simplify the workflow process, introduce additional methods of data filtration or provide the ability to optimize the calculation task. The next is to explore the possibility of increasing the accuracy of registering adjacent scanning images by using a scanner with higher precision parameters and lower image noise as well as by creating a, respectively, superior reference system of higher accuracy (used targets and measurement with redundant observations and least squares method network alignment).

Research studies on these issues are currently being conducted at the Faculty of Environmental, Geomatic and Energy Engineering of Kielce University of Technology.

7 Final remarks and conclusions

The determined pairs of virtual reference points increase the accuracy of the generated model, since all individual clouds undergo spatial transformation using the same group of reference points. In the task discussed herein, these were points B, E, and G and scanner centres on individual scanning stations (Figures 5 and 6). The errors on the alignment points after the transformation discussed herein fall within the range of 0.02–0.04 m (Figure 7).

The example presented in this article is relatively complicated. With a very small diameter, the structure has no discernible details on the shell as well. The steel shell, especially in the upper levels of the structure, contributed to the intensification of the reflections, which distorted the shape of the object in these scanned areas. Those factors reduce the accuracy of determination of the chimney centre points on the scanned image (Figure 9).

Final image after registering scanned images using the virtual reference points.

8 Conclusions

The method of aligning scanned images with conventional measurement in the case of an industrial chimney eliminates the disadvantages of the prismless measurement as well as the instrument errors of the scanner.

On the stage of filtering out outlier points, the method of the median of bisectors of the chord is more effective than the approximation method.

For determining the centre of the section, the circle approximation method is preferable to the method of the median of bisectors of the chord.

For the topmost section of the chimney, isolating wider bands is necessary. For the analysed structure, good results were obtained for 1 m wide bands.

The more regular the circular cross-section, the better the effect of the applied method. The impact of circular section deformations can be mitigated by using a higher number of scanner stations. In each case, regardless of their number, the stations should be arranged symmetrically around the structure.

The impact of the inclination and the non-vertical axis of the could be reduced by approximation with cylinder side wall or cone. This solution requires much wider bands in order to ensure the convergence of the subsequent iterations.

The method presented herein is a practical implementation of the concept of reliability measurements, which is based on independent measurement and mutual control. On the other hand, due to the need to perform additional measurements and data processing, it is relatively labour consuming.

Acknowledgements

The project is supported by the program of the Minister of Science and Higher Education under the name: “Regional Initiative of Excellence” in 2019 – 2022 project number 025/RID/2018/19 financing PLN 12,000,000.

References

[1] Edgar A, East B, Hammond D, Shelden D, Szigeti F, Onuma K, et al. United States National Building Information Modeling Standard: Version 1 – Part 1: Overview, Principles and Methodologies. USA: National Institute of Building Sciences; 2007.10.1061/40937(261)8Search in Google Scholar

[2] Kołakowska M, Świerczyńska E. Selected aspects of using terrestrial laser scanning technology as the source of additional data for building information modelling. Chall Mod Technol. 2013;4:26–32.Search in Google Scholar

[3] Zaczek-Peplinska J, Pasik M, Adamek A, Kołakowska M, Łapiński S. Monitoring technical conditions of engineering structure using the terrestrial laser scanning technology. Rep Geodesy Geoinformatics. 2013;1:1–10.10.2478/rgg-2013-0008Search in Google Scholar

[4] Skoczylas A, Kamoda J, Żaczek-Peplińska J. Geodetic monitoring (TLS) of a steel transport trestle bridge located in an active mining exploitation site. Ann Wars Univ Life Sci – SGGW Land Reclam. 2016;3:255–66.10.1515/sggw-2016-0020Search in Google Scholar

[5] Lindskog E, Berglund J, Vallhagen J, Johansson B. Layout planning and geometry analysis using 3D laser scanning in production system redesign. 6th CIRP Conference on Assembly Technologies and Systems (CATS). Procedia CIRP. 2016;44:126–31.10.1016/j.procir.2016.02.118Search in Google Scholar

[6] Selbesoglu M, Bakirman T, Gokbayrak O. Deformation measurement using terrestrial laser scanner for cultural heritage. Int Arch Photogramm Remote Sens Spat Inf Sci. 2016;XLII-2(W1):89–93. 10.5194/isprs-archives-XLII-2-W1-89-2016.Search in Google Scholar

[7] Rüther H, Chazan M, Schroeder R, Neeser R, Held Ch., Walker S, et al. Laser scanning for conservation and research of African cultural heritage sites: the case study of Wonderwerk Cave, South Africa. J Archaeol Sci. 2009;9:1847–56. 10.1016/j.jas.2009.04.012.Search in Google Scholar

[8] Zaczek-Peplinska J, Kowalska M. Terrestrial laser scanning in monitoring hydrotechnical objects. J Ecol Eng. 2016;4:120–8. 10.12911/22998993/63887.Search in Google Scholar

[9] Schneider D. Terrestrial laser scanning for area based deformation analysis of towers and water dams. From: Proc. of 12th FIG Symposium. Baden; 2006.Search in Google Scholar

[10] Yang H, Omidalizarandi M, Xu X, Neumann I. Terrestrial laser scanning technology for deformation monitoring and surface modeling of arch structures. Compos Struct. 2017;169:173–9. 10.1016/j.compstruct.2016.10.095.Search in Google Scholar

[11] Ziolkowski P, Szulwic J, Miskiewicz M. Deformation analysis of a composite bridge during proof loading using point cloud processing. Sensors. 2018;18(12):4332–50. 10.3390/s18124332.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[12] Lenda G, Uznański A, Strach M, Lewińska P. Laser scanning in engineering surveying: methods of measurement and modeling of structures. Rep Geodesy Geoinformatics. 2016;100/2016:109–30. 10.1515/rgg-2016-0010.Search in Google Scholar

[13] Wang W, Zhao W, Huang L, Vimarlund V, Wang Z. Applications of terrestrial laser scanning for tunnels: a review. J Traffic Transport Eng (Engl Ed). 2014;5:325–37. 10.1016/S2095-7564(15)30279-8.Search in Google Scholar

[14] Skrzypczak I, Kogut J, Kokoszka W, Zientek D. Monitoring of landslide areas with the use of contemporary methods of measuring and mapping. Civ Environ Eng Rep. 2017;24(1):69–82. 10.1515/ceer-2017-0005.Search in Google Scholar

[15] Puniach E. Methodology of geodetic deformation survey in diagnostics of multi-flue industrial chimneys. Krakow: AGH Publishing House; 2016.Search in Google Scholar

[16] Reshetyuk Y. Terrestrial laser scanning: Error sources, self-calibration direct georeferencing. Stockholm, Sweden; Universitetsservice US AB: VDM Verlag; 2009.Search in Google Scholar

[17] Kowalska M, Zaczek-Peplinska J. Examples of measuring marks used in geo-reference and the connection between classic geodetic measurements and terrestrial laser scanning. Technic Trans. 2018;1:151–62. 10.4467/2353737XCT.18.012.7963.Search in Google Scholar

[18] Gawałkiewicz R. The example of appliance of laser scanning in high industrial objects inventory and monitoring. Geomat Environ Eng. 2007;4:111–26.Search in Google Scholar

[19] Gocał J. Geodezja Inżynieryjno-Przemysłowa cz. III. Kraków: Wydawnictwa AGH; 2010.Search in Google Scholar

[20] Wujanz D. Terrestrial laser scanning for geodetic deformation monitoring. Germany, PhD Thesis: Technische Universität Berlin; 2016. 10.14279/depositonce-5136.Search in Google Scholar

[21] Kaszowska O, Gruchlik P, Mika W. Industrial chimney monitoring – contemporary methods. E3S Web Conf. 2018;36:01005. 10.1051/e3sconf/20183601005.Search in Google Scholar

[22] Piech I, Kwoczyńska B, Łukaszewicz S. Determination of the verticality of the chimney on the basis of photogrammetric measurements. Acta Sci Polonorum Admin Locorum. 2017;4:285–93. 10.31648/aspal.452Search in Google Scholar

[23] Gawałkiewicz R. The inventory of high objects applying laser scanning, focus on the cataloguing a reinforced concrete industrial chimney. Geoinformat Pol. 2015;14:95–107.Search in Google Scholar

[24] Lipecki T, Jaśkowski W, Matwij W, Skobliński W. Zastosowanie skanera Faro Focus X330 w ocenie pionowości komina o wysokości 220 m [Use of the laser scanner Faro Focus X330 in the assessment of the verticality of the chimney with a height of 220 m]. Przegląd Górniczy. 2017;6:44–53.Search in Google Scholar

[25] Muszynski Z, Milczarek W. Application of ter-restial laser scanning to study the geometry of slender objects. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science. 2017. 042069–86. 10.1088/1755-1315/95/4/042069.Search in Google Scholar

[26] Cox RP. Real-world comparisons between target-based and targetless point-cloud registration in FARO Scene, Trimble RealWorks and Autodesk Recap. Australia: University of Southern Queensland Faculty of Health, Engineering and Sciences; 2015.Search in Google Scholar

[27] Marjetič A. TPS And TLS laser scanning for measuring the inclination of tall chimneys. Geodetski Glas. 2018;49:29–43.10.58817/2233-1786.2018.52.49.29Search in Google Scholar

© 2020 Granek Grzegorz et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- The simulation approach to the interpretation of archival aerial photographs

- The application of137Cs and210Pbexmethods in soil erosion research of Titel loess plateau, Vojvodina, Northern Serbia

- Provenance and tectonic significance of the Zhongwunongshan Group from the Zhongwunongshan Structural Belt in China: insights from zircon geochronology

- Analysis, Assessment and Early Warning of Mudflow Disasters along the Shigatse Section of the China–Nepal Highway

- Sedimentary succession and recognition marks of lacustrine gravel beach-bars, a case study from the Qinghai Lake, China

- Predicting small water courses’ physico-chemical status from watershed characteristics with two multivariate statistical methods

- An Overview of the Carbonatites from the Indian Subcontinent

- A new statistical approach to the geochemical systematics of Italian alkaline igneous rocks

- The significance of karst areas in European national parks and geoparks

- Geochronology, trace elements and Hf isotopic geochemistry of zircons from Swat orthogneisses, Northern Pakistan

- Regional-scale drought monitor using synthesized index based on remote sensing in northeast China

- Application of combined electrical resistivity tomography and seismic reflection method to explore hidden active faults in Pingwu, Sichuan, China

- Impact of interpolation techniques on the accuracy of large-scale digital elevation model

- Natural and human-induced factors controlling the phreatic groundwater geochemistry of the Longgang River basin, South China

- Land use/land cover assessment as related to soil and irrigation water salinity over an oasis in arid environment

- Effect of tillage, slope, and rainfall on soil surface microtopography quantified by geostatistical and fractal indices during sheet erosion

- Validation of the number of tie vectors in post-processing using the method of frequency in a centric cube

- An integrated petrophysical-based wedge modeling and thin bed AVO analysis for improved reservoir characterization of Zhujiang Formation, Huizhou sub-basin, China: A case study

- A grain size auto-classification of Baikouquan Formation, Mahu Depression, Junggar Basin, China

- Dynamics of mid-channel bars in the Middle Vistula River in response to ferry crossing abutment construction

- Estimation of permeability and saturation based on imaginary component of complex resistivity spectra: A laboratory study

- Distribution characteristics of typical geological relics in the Western Sichuan Plateau

- Inconsistency distribution patterns of different remote sensing land-cover data from the perspective of ecological zoning

- A new methodological approach (QEMSCAN®) in the mineralogical study of Polish loess: Guidelines for further research

- Displacement and deformation study of engineering structures with the use of modern laser technologies

- Virtual resolution enhancement: A new enhancement tool for seismic data

- Aeromagnetic mapping of fault architecture along Lagos–Ore axis, southwestern Nigeria

- Deformation and failure mechanism of full seam chamber with extra-large section and its control technology

- Plastic failure zone characteristics and stability control technology of roadway in the fault area under non-uniformly high geostress: A case study from Yuandian Coal Mine in Northern Anhui Province, China

- Comparison of swarm intelligence algorithms for optimized band selection of hyperspectral remote sensing image

- Soil carbon stock and nutrient characteristics of Senna siamea grove in the semi-deciduous forest zone of Ghana

- Carbonatites from the Southern Brazilian platform: I

- Seismicity, focal mechanism, and stress tensor analysis of the Simav region, western Turkey

- Application of simulated annealing algorithm for 3D coordinate transformation problem solution

- Application of the terrestrial laser scanner in the monitoring of earth structures

- The Cretaceous igneous rocks in southeastern Guangxi and their implication for tectonic environment in southwestern South China Block

- Pore-scale gas–water flow in rock: Visualization experiment and simulation

- Assessment of surface parameters of VDW foundation piles using geodetic measurement techniques

- Spatial distribution and risk assessment of toxic metals in agricultural soils from endemic nasopharyngeal carcinoma region in South China

- An ABC-optimized fuzzy ELECTRE approach for assessing petroleum potential at the petroleum system level

- Microscopic mechanism of sandstone hydration in Yungang Grottoes, China

- Importance of traditional landscapes in Slovenia for conservation of endangered butterfly

- Landscape pattern and economic factors’ effect on prediction accuracy of cellular automata-Markov chain model on county scale

- The influence of river training on the location of erosion and accumulation zones (Kłodzko County, South West Poland)

- Multi-temporal survey of diaphragm wall with terrestrial laser scanning method

- Functionality and reliability of horizontal control net (Poland)

- Strata behavior and control strategy of backfilling collaborate with caving fully-mechanized mining

- The use of classical methods and neural networks in deformation studies of hydrotechnical objects

- Ice-crevasse sedimentation in the eastern part of the Głubczyce Plateau (S Poland) during the final stage of the Drenthian Glaciation

- Structure of end moraines and dynamics of the recession phase of the Warta Stadial ice sheet, Kłodawa Upland, Central Poland

- Mineralogy, mineral chemistry and thermobarometry of post-mineralization dykes of the Sungun Cu–Mo porphyry deposit (Northwest Iran)

- Main problems of the research on the Palaeolithic of Halych-Dnister region (Ukraine)

- Application of isometric transformation and robust estimation to compare the measurement results of steel pipe spools

- Hybrid machine learning hydrological model for flood forecast purpose

- Rainfall thresholds of shallow landslides in Wuyuan County of Jiangxi Province, China

- Dynamic simulation for the process of mining subsidence based on cellular automata model

- Developing large-scale international ecological networks based on least-cost path analysis – a case study of Altai mountains

- Seismic characteristics of polygonal fault systems in the Great South Basin, New Zealand

- New approach of clustering of late Pleni-Weichselian loess deposits (L1LL1) in Poland

- Implementation of virtual reference points in registering scanning images of tall structures

- Constraints of nonseismic geophysical data on the deep geological structure of the Benxi iron-ore district, Liaoning, China

- Mechanical analysis of basic roof fracture mechanism and feature in coal mining with partial gangue backfilling

- The violent ground motion before the Jiuzhaigou earthquake Ms7.0

- Landslide site delineation from geometric signatures derived with the Hilbert–Huang transform for cases in Southern Taiwan

- Hydrological process simulation in Manas River Basin using CMADS

- LA-ICP-MS U–Pb ages of detrital zircons from Middle Jurassic sedimentary rocks in southwestern Fujian: Sedimentary provenance and its geological significance

- Analysis of pore throat characteristics of tight sandstone reservoirs

- Effects of igneous intrusions on source rock in the early diagenetic stage: A case study on Beipiao Formation in Jinyang Basin, Northeast China

- Applying floodplain geomorphology to flood management (The Lower Vistula River upstream from Plock, Poland)

- Effect of photogrammetric RPAS flight parameters on plani-altimetric accuracy of DTM

- Morphodynamic conditions of heavy metal concentration in deposits of the Vistula River valley near Kępa Gostecka (central Poland)

- Accuracy and functional assessment of an original low-cost fibre-based inclinometer designed for structural monitoring

- The impacts of diagenetic facies on reservoir quality in tight sandstones

- Application of electrical resistivity imaging to detection of hidden geological structures in a single roadway

- Comparison between electrical resistivity tomography and tunnel seismic prediction 303 methods for detecting the water zone ahead of the tunnel face: A case study

- The genesis model of carbonate cementation in the tight oil reservoir: A case of Chang 6 oil layers of the Upper Triassic Yanchang Formation in the western Jiyuan area, Ordos Basin, China

- Disintegration characteristics in granite residual soil and their relationship with the collapsing gully in South China

- Analysis of surface deformation and driving forces in Lanzhou

- Geochemical characteristics of produced water from coalbed methane wells and its influence on productivity in Laochang Coalfield, China

- A combination of genetic inversion and seismic frequency attributes to delineate reservoir targets in offshore northern Orange Basin, South Africa

- Explore the application of high-resolution nighttime light remote sensing images in nighttime marine ship detection: A case study of LJ1-01 data

- DTM-based analysis of the spatial distribution of topolineaments

- Spatiotemporal variation and climatic response of water level of major lakes in China, Mongolia, and Russia

- The Cretaceous stratigraphy, Songliao Basin, Northeast China: Constrains from drillings and geophysics

- Canal of St. Bartholomew in Seča/Sezza: Social construction of the seascape

- A modelling resin material and its application in rock-failure study: Samples with two 3D internal fracture surfaces

- Utilization of marble piece wastes as base materials

- Slope stability evaluation using backpropagation neural networks and multivariate adaptive regression splines

- Rigidity of “Warsaw clay” from the Poznań Formation determined by in situ tests

- Numerical simulation for the effects of waves and grain size on deltaic processes and morphologies

- Impact of tourism activities on water pollution in the West Lake Basin (Hangzhou, China)

- Fracture characteristics from outcrops and its meaning to gas accumulation in the Jiyuan Basin, Henan Province, China

- Impact evaluation and driving type identification of human factors on rural human settlement environment: Taking Gansu Province, China as an example

- Identification of the spatial distributions, pollution levels, sources, and health risk of heavy metals in surface dusts from Korla, NW China

- Petrography and geochemistry of clastic sedimentary rocks as evidence for the provenance of the Jurassic stratum in the Daqingshan area

- Super-resolution reconstruction of a digital elevation model based on a deep residual network

- Seismic prediction of lithofacies heterogeneity in paleogene hetaoyuan shale play, Biyang depression, China

- Cultural landscape of the Gorica Hills in the nineteenth century: Franciscean land cadastre reports as the source for clarification of the classification of cultivable land types

- Analysis and prediction of LUCC change in Huang-Huai-Hai river basin

- Hydrochemical differences between river water and groundwater in Suzhou, Northern Anhui Province, China

- The relationship between heat flow and seismicity in global tectonically active zones

- Modeling of Landslide susceptibility in a part of Abay Basin, northwestern Ethiopia

- M-GAM method in function of tourism potential assessment: Case study of the Sokobanja basin in eastern Serbia

- Dehydration and stabilization of unconsolidated laminated lake sediments using gypsum for the preparation of thin sections

- Agriculture and land use in the North of Russia: Case study of Karelia and Yakutia

- Textural characteristics, mode of transportation and depositional environment of the Cretaceous sandstone in the Bredasdorp Basin, off the south coast of South Africa: Evidence from grain size analysis

- One-dimensional constrained inversion study of TEM and application in coal goafs’ detection

- The spatial distribution of retail outlets in Urumqi: The application of points of interest

- Aptian–Albian deposits of the Ait Ourir basin (High Atlas, Morocco): New additional data on their paleoenvironment, sedimentology, and palaeogeography

- Traditional agricultural landscapes in Uskopaljska valley (Bosnia and Herzegovina)

- A detection method for reservoir waterbodies vector data based on EGADS

- Modelling and mapping of the COVID-19 trajectory and pandemic paths at global scale: A geographer’s perspective

- Effect of organic maturity on shale gas genesis and pores development: A case study on marine shale in the upper Yangtze region, South China

- Gravel roundness quantitative analysis for sedimentary microfacies of fan delta deposition, Baikouquan Formation, Mahu Depression, Northwestern China

- Features of terraces and the incision rate along the lower reaches of the Yarlung Zangbo River east of Namche Barwa: Constraints on tectonic uplift

- Application of laser scanning technology for structure gauge measurement

- Calibration of the depth invariant algorithm to monitor the tidal action of Rabigh City at the Red Sea Coast, Saudi Arabia

- Evolution of the Bystrzyca River valley during Middle Pleistocene Interglacial (Sudetic Foreland, south-western Poland)

- A 3D numerical analysis of the compaction effects on the behavior of panel-type MSE walls

- Landscape dynamics at borderlands: analysing land use changes from Southern Slovenia

- Effects of oil viscosity on waterflooding: A case study of high water-cut sandstone oilfield in Kazakhstan

- Special Issue: Alkaline-Carbonatitic magmatism

- Carbonatites from the southern Brazilian Platform: A review. II: Isotopic evidences

- Review Article

- Technology and innovation: Changing concept of rural tourism – A systematic review

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- The simulation approach to the interpretation of archival aerial photographs

- The application of137Cs and210Pbexmethods in soil erosion research of Titel loess plateau, Vojvodina, Northern Serbia

- Provenance and tectonic significance of the Zhongwunongshan Group from the Zhongwunongshan Structural Belt in China: insights from zircon geochronology

- Analysis, Assessment and Early Warning of Mudflow Disasters along the Shigatse Section of the China–Nepal Highway

- Sedimentary succession and recognition marks of lacustrine gravel beach-bars, a case study from the Qinghai Lake, China

- Predicting small water courses’ physico-chemical status from watershed characteristics with two multivariate statistical methods

- An Overview of the Carbonatites from the Indian Subcontinent

- A new statistical approach to the geochemical systematics of Italian alkaline igneous rocks

- The significance of karst areas in European national parks and geoparks

- Geochronology, trace elements and Hf isotopic geochemistry of zircons from Swat orthogneisses, Northern Pakistan

- Regional-scale drought monitor using synthesized index based on remote sensing in northeast China

- Application of combined electrical resistivity tomography and seismic reflection method to explore hidden active faults in Pingwu, Sichuan, China

- Impact of interpolation techniques on the accuracy of large-scale digital elevation model

- Natural and human-induced factors controlling the phreatic groundwater geochemistry of the Longgang River basin, South China

- Land use/land cover assessment as related to soil and irrigation water salinity over an oasis in arid environment

- Effect of tillage, slope, and rainfall on soil surface microtopography quantified by geostatistical and fractal indices during sheet erosion

- Validation of the number of tie vectors in post-processing using the method of frequency in a centric cube

- An integrated petrophysical-based wedge modeling and thin bed AVO analysis for improved reservoir characterization of Zhujiang Formation, Huizhou sub-basin, China: A case study

- A grain size auto-classification of Baikouquan Formation, Mahu Depression, Junggar Basin, China

- Dynamics of mid-channel bars in the Middle Vistula River in response to ferry crossing abutment construction

- Estimation of permeability and saturation based on imaginary component of complex resistivity spectra: A laboratory study

- Distribution characteristics of typical geological relics in the Western Sichuan Plateau

- Inconsistency distribution patterns of different remote sensing land-cover data from the perspective of ecological zoning

- A new methodological approach (QEMSCAN®) in the mineralogical study of Polish loess: Guidelines for further research

- Displacement and deformation study of engineering structures with the use of modern laser technologies

- Virtual resolution enhancement: A new enhancement tool for seismic data

- Aeromagnetic mapping of fault architecture along Lagos–Ore axis, southwestern Nigeria

- Deformation and failure mechanism of full seam chamber with extra-large section and its control technology

- Plastic failure zone characteristics and stability control technology of roadway in the fault area under non-uniformly high geostress: A case study from Yuandian Coal Mine in Northern Anhui Province, China

- Comparison of swarm intelligence algorithms for optimized band selection of hyperspectral remote sensing image

- Soil carbon stock and nutrient characteristics of Senna siamea grove in the semi-deciduous forest zone of Ghana

- Carbonatites from the Southern Brazilian platform: I

- Seismicity, focal mechanism, and stress tensor analysis of the Simav region, western Turkey

- Application of simulated annealing algorithm for 3D coordinate transformation problem solution

- Application of the terrestrial laser scanner in the monitoring of earth structures

- The Cretaceous igneous rocks in southeastern Guangxi and their implication for tectonic environment in southwestern South China Block

- Pore-scale gas–water flow in rock: Visualization experiment and simulation

- Assessment of surface parameters of VDW foundation piles using geodetic measurement techniques

- Spatial distribution and risk assessment of toxic metals in agricultural soils from endemic nasopharyngeal carcinoma region in South China

- An ABC-optimized fuzzy ELECTRE approach for assessing petroleum potential at the petroleum system level

- Microscopic mechanism of sandstone hydration in Yungang Grottoes, China

- Importance of traditional landscapes in Slovenia for conservation of endangered butterfly

- Landscape pattern and economic factors’ effect on prediction accuracy of cellular automata-Markov chain model on county scale

- The influence of river training on the location of erosion and accumulation zones (Kłodzko County, South West Poland)

- Multi-temporal survey of diaphragm wall with terrestrial laser scanning method

- Functionality and reliability of horizontal control net (Poland)

- Strata behavior and control strategy of backfilling collaborate with caving fully-mechanized mining

- The use of classical methods and neural networks in deformation studies of hydrotechnical objects

- Ice-crevasse sedimentation in the eastern part of the Głubczyce Plateau (S Poland) during the final stage of the Drenthian Glaciation

- Structure of end moraines and dynamics of the recession phase of the Warta Stadial ice sheet, Kłodawa Upland, Central Poland

- Mineralogy, mineral chemistry and thermobarometry of post-mineralization dykes of the Sungun Cu–Mo porphyry deposit (Northwest Iran)

- Main problems of the research on the Palaeolithic of Halych-Dnister region (Ukraine)

- Application of isometric transformation and robust estimation to compare the measurement results of steel pipe spools

- Hybrid machine learning hydrological model for flood forecast purpose

- Rainfall thresholds of shallow landslides in Wuyuan County of Jiangxi Province, China

- Dynamic simulation for the process of mining subsidence based on cellular automata model

- Developing large-scale international ecological networks based on least-cost path analysis – a case study of Altai mountains

- Seismic characteristics of polygonal fault systems in the Great South Basin, New Zealand

- New approach of clustering of late Pleni-Weichselian loess deposits (L1LL1) in Poland

- Implementation of virtual reference points in registering scanning images of tall structures

- Constraints of nonseismic geophysical data on the deep geological structure of the Benxi iron-ore district, Liaoning, China

- Mechanical analysis of basic roof fracture mechanism and feature in coal mining with partial gangue backfilling

- The violent ground motion before the Jiuzhaigou earthquake Ms7.0

- Landslide site delineation from geometric signatures derived with the Hilbert–Huang transform for cases in Southern Taiwan

- Hydrological process simulation in Manas River Basin using CMADS

- LA-ICP-MS U–Pb ages of detrital zircons from Middle Jurassic sedimentary rocks in southwestern Fujian: Sedimentary provenance and its geological significance

- Analysis of pore throat characteristics of tight sandstone reservoirs

- Effects of igneous intrusions on source rock in the early diagenetic stage: A case study on Beipiao Formation in Jinyang Basin, Northeast China

- Applying floodplain geomorphology to flood management (The Lower Vistula River upstream from Plock, Poland)

- Effect of photogrammetric RPAS flight parameters on plani-altimetric accuracy of DTM

- Morphodynamic conditions of heavy metal concentration in deposits of the Vistula River valley near Kępa Gostecka (central Poland)

- Accuracy and functional assessment of an original low-cost fibre-based inclinometer designed for structural monitoring

- The impacts of diagenetic facies on reservoir quality in tight sandstones

- Application of electrical resistivity imaging to detection of hidden geological structures in a single roadway

- Comparison between electrical resistivity tomography and tunnel seismic prediction 303 methods for detecting the water zone ahead of the tunnel face: A case study

- The genesis model of carbonate cementation in the tight oil reservoir: A case of Chang 6 oil layers of the Upper Triassic Yanchang Formation in the western Jiyuan area, Ordos Basin, China

- Disintegration characteristics in granite residual soil and their relationship with the collapsing gully in South China

- Analysis of surface deformation and driving forces in Lanzhou

- Geochemical characteristics of produced water from coalbed methane wells and its influence on productivity in Laochang Coalfield, China

- A combination of genetic inversion and seismic frequency attributes to delineate reservoir targets in offshore northern Orange Basin, South Africa

- Explore the application of high-resolution nighttime light remote sensing images in nighttime marine ship detection: A case study of LJ1-01 data

- DTM-based analysis of the spatial distribution of topolineaments

- Spatiotemporal variation and climatic response of water level of major lakes in China, Mongolia, and Russia

- The Cretaceous stratigraphy, Songliao Basin, Northeast China: Constrains from drillings and geophysics

- Canal of St. Bartholomew in Seča/Sezza: Social construction of the seascape

- A modelling resin material and its application in rock-failure study: Samples with two 3D internal fracture surfaces

- Utilization of marble piece wastes as base materials

- Slope stability evaluation using backpropagation neural networks and multivariate adaptive regression splines

- Rigidity of “Warsaw clay” from the Poznań Formation determined by in situ tests

- Numerical simulation for the effects of waves and grain size on deltaic processes and morphologies

- Impact of tourism activities on water pollution in the West Lake Basin (Hangzhou, China)

- Fracture characteristics from outcrops and its meaning to gas accumulation in the Jiyuan Basin, Henan Province, China

- Impact evaluation and driving type identification of human factors on rural human settlement environment: Taking Gansu Province, China as an example

- Identification of the spatial distributions, pollution levels, sources, and health risk of heavy metals in surface dusts from Korla, NW China

- Petrography and geochemistry of clastic sedimentary rocks as evidence for the provenance of the Jurassic stratum in the Daqingshan area

- Super-resolution reconstruction of a digital elevation model based on a deep residual network

- Seismic prediction of lithofacies heterogeneity in paleogene hetaoyuan shale play, Biyang depression, China

- Cultural landscape of the Gorica Hills in the nineteenth century: Franciscean land cadastre reports as the source for clarification of the classification of cultivable land types

- Analysis and prediction of LUCC change in Huang-Huai-Hai river basin

- Hydrochemical differences between river water and groundwater in Suzhou, Northern Anhui Province, China

- The relationship between heat flow and seismicity in global tectonically active zones

- Modeling of Landslide susceptibility in a part of Abay Basin, northwestern Ethiopia

- M-GAM method in function of tourism potential assessment: Case study of the Sokobanja basin in eastern Serbia

- Dehydration and stabilization of unconsolidated laminated lake sediments using gypsum for the preparation of thin sections

- Agriculture and land use in the North of Russia: Case study of Karelia and Yakutia

- Textural characteristics, mode of transportation and depositional environment of the Cretaceous sandstone in the Bredasdorp Basin, off the south coast of South Africa: Evidence from grain size analysis

- One-dimensional constrained inversion study of TEM and application in coal goafs’ detection

- The spatial distribution of retail outlets in Urumqi: The application of points of interest

- Aptian–Albian deposits of the Ait Ourir basin (High Atlas, Morocco): New additional data on their paleoenvironment, sedimentology, and palaeogeography

- Traditional agricultural landscapes in Uskopaljska valley (Bosnia and Herzegovina)

- A detection method for reservoir waterbodies vector data based on EGADS

- Modelling and mapping of the COVID-19 trajectory and pandemic paths at global scale: A geographer’s perspective

- Effect of organic maturity on shale gas genesis and pores development: A case study on marine shale in the upper Yangtze region, South China

- Gravel roundness quantitative analysis for sedimentary microfacies of fan delta deposition, Baikouquan Formation, Mahu Depression, Northwestern China

- Features of terraces and the incision rate along the lower reaches of the Yarlung Zangbo River east of Namche Barwa: Constraints on tectonic uplift

- Application of laser scanning technology for structure gauge measurement

- Calibration of the depth invariant algorithm to monitor the tidal action of Rabigh City at the Red Sea Coast, Saudi Arabia

- Evolution of the Bystrzyca River valley during Middle Pleistocene Interglacial (Sudetic Foreland, south-western Poland)

- A 3D numerical analysis of the compaction effects on the behavior of panel-type MSE walls

- Landscape dynamics at borderlands: analysing land use changes from Southern Slovenia

- Effects of oil viscosity on waterflooding: A case study of high water-cut sandstone oilfield in Kazakhstan

- Special Issue: Alkaline-Carbonatitic magmatism

- Carbonatites from the southern Brazilian Platform: A review. II: Isotopic evidences

- Review Article

- Technology and innovation: Changing concept of rural tourism – A systematic review