Abstract

Maintenance of traditional cultural landscapes largely depends on traditional agricultural practices, which are nowadays in decline as a result of increasingly intensive and mechanised land use. Losing traditional practices may result in impoverishing of picturesque mosaic landscape and biodiversity. This research focuses on land-use changes in two time periods (2002–2008; 2013–2016) and effects of changes reflecting on populations of critically endangered butterfly. False Ringlet, Coenonympha oedippus (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae), is a habitat specialist, which in Slovenia inhabits two geographically distinct contrasting habitats – dry meadows in south-western and wetlands in central Slovenia. We compared nine environmental parameters to assess environmental differences, which shape species habitat; seven parameters significantly differ among the four geographical regions and five among the two habitat types. Four parameters significantly differ (i.e. at least in two regions) when tested for homogeneity, while in dry habitat type all (except slope) were significant and none in wet habitat. Changes in land use in two studied periods lit up two processes: transformation of meadows into agricultural land and overgrowing of the meadows, both processes affecting species severely. We believe that maintaining of traditional landscapes in future could serve as a good conservation practice for this endangered species.

1 Introduction

Landscape diversity consisted of heterogeneous landscape structure largely depends on traditional practices and knowledge related to land use which could be recognised as a contribution to cultural diversity. Losing traditional practices may result in impoverishing of picturesque mosaic landscape and biodiversity. The decline of cultural ecosystem services coincides with the decline in landscape diversity as a result of increasingly intensive and mechanised land use [1]. Furthermore, urbanisation and its associated transportation infrastructure and other activities define the relationship between city and countryside and influence local landscape change. Changes occur even in unique small-scaled landscapes with increasing speed and therefore an important cultural heritage is becoming lost [2,3]. In general, landscapes are less diverse and less coherent than the traditional ones and main changes occurring can be divided in four groups [4]: (i) increased intensification for the agricultural production, (ii) urban sprawl, (iii) specific tourist and recreational forms of land use and (iv) extensification of land use and land abandonment. All these changes result in sharp gradients in land use, which negatively influence biodiversity [4,5].

Traditional cultural landscapes have diverse and distinct identity usually linked to the character of the region [3,6]. Landscapes in Slovenia were primarily influenced by their geographical position, where four major natural units (the Alps, the Dinaric Alps, the Pannonian Basin and the Mediterranean area) join [7] and interweave in a small geographical scale (20,272 km2); all four major units were gradually cultivated by generations of people originated from four cultures (Slavic, Germanic, Roman and Hungarian) [8,9]. Slovenian landscapes are therefore extremely diverse [3,5,10,11]. The important part of areas with high natural value lies within agricultural landscapes, which altogether cover around 35% of the country territory [12]. Former agricultural practices created a heterogeneous landscape with a mosaic patches of various land uses, many transitional elements and various succession stages, which contributed to the overall biodiversity [5,13]. However, polarisation in agricultural production, intensifying cultivated land in one hand and the abandonment of less-promising land on the other, causes intense biodiversity loss [1,12,14]. This recent agricultural polarisation became a key reason for loss of habitats causing populations declines of many species and deterioration of their conservation status [5,15,16,17]. Importance of maintaining diversity in traditional landscapes together with its biodiversity was stressed out globally in Convention on Biological Diversity [18], where it was also agreed to promote sustainable development at local level [3,19,20].

Nonetheless, changes in landscapes listed above seem to be straightforward in their occurrence; they are often difficult to study as most land-use statistics is not reliable since it is often outdated [21,22]. A common practice in historical geography is use of time series of historical maps and aerial photographs and it has been proven to be very useful, especially in well-documented regions [1,22,23,24,25,26,27] that were studied in detail with an interdisciplinary approach [4,28,29]. Nevertheless, land use is only one aspect which determines landscape character; for butterflies, microhabitat is also important (e.g. [30,31,32,33,34]).

Areas with relatively well-preserved grassland habitats resulting from extensive traditional use are strongly connected with highly endangered specialist butterfly species, False Ringlet, Coenonympha oedippus (Fabricius). Complexity of several ecological factors (from oviposition and larval preferences, microhabitat movements of adults to possible caterpillar rearing in situ) was already determined to affect species [32]. Also morphological differentiation of ecotypes [31], genetic structuring of Slovenian populations [33,34] and regular period monitoring [35,36] reviewed abundance and presence of this endangered species throughout its Slovenian range. However, despite all done research, the state of the art for C. oedippus shows that species abundance is steadily decreasing and in some known localities, populations are already extinct [16,36,37]. Therefore, the present study was focused on differentiation of landscape parameters among and within geographical regions of two contrasting habitat types [31,37] occupied by C. oedippus in Slovenia (wet versus dry) to reveal an array of environmental features at habitat patches occupied by this endangered species.

Among environmental parameters, altitude is believed to be one of the most important modifiers of temperature conditions. Further, bedrock defines texture, physical and chemical properties of the soil. Slope influences on soil depth and water capacity of the soil. Understanding the link between species and landscape diversity is hence crucial for its future conservation. At the microhabitat level, however, Čelik et al. [32] highlighted several features that are prerequisites for the presence of C. oedippus, despite the contrasting habitats it inhabits across the Europe: (i) appropriate vegetation structure and high cover litter as the main factor influencing the oviposition electivity and development of juvenile stages, (ii) high host-plant coverage at the oviposition sites and (iii) necessity of availability of winter-green host plants in the vicinity of hibernated larvae that are crucial for their survival. On the contrary, (iv) females were shown to be unselective towards the oviposition substratum and (v) to some extent, oviposition height can be adjusted to positions with warmer microclimatic conditions. Finally, (vi) most important host plants differ between the two contrasting habitats (i.e. Molinia caerulea at wet and Festuca rupicola at dry habitats; however, some other species can be frequently used as well). Nevertheless, these factors need to be placed into a broader picture that can be achieved through a study of possible links between C. oedippus presence and other environmental parameters at differently large geographical levels. To address this topic, we tested nine environmental parameters for possible links between geographical regions/habitat types, and seek for changes in vegetation cover within 15-year time frame in connection to changes which affected the loss of habitat patches appropriate for C. oedippus.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Study species

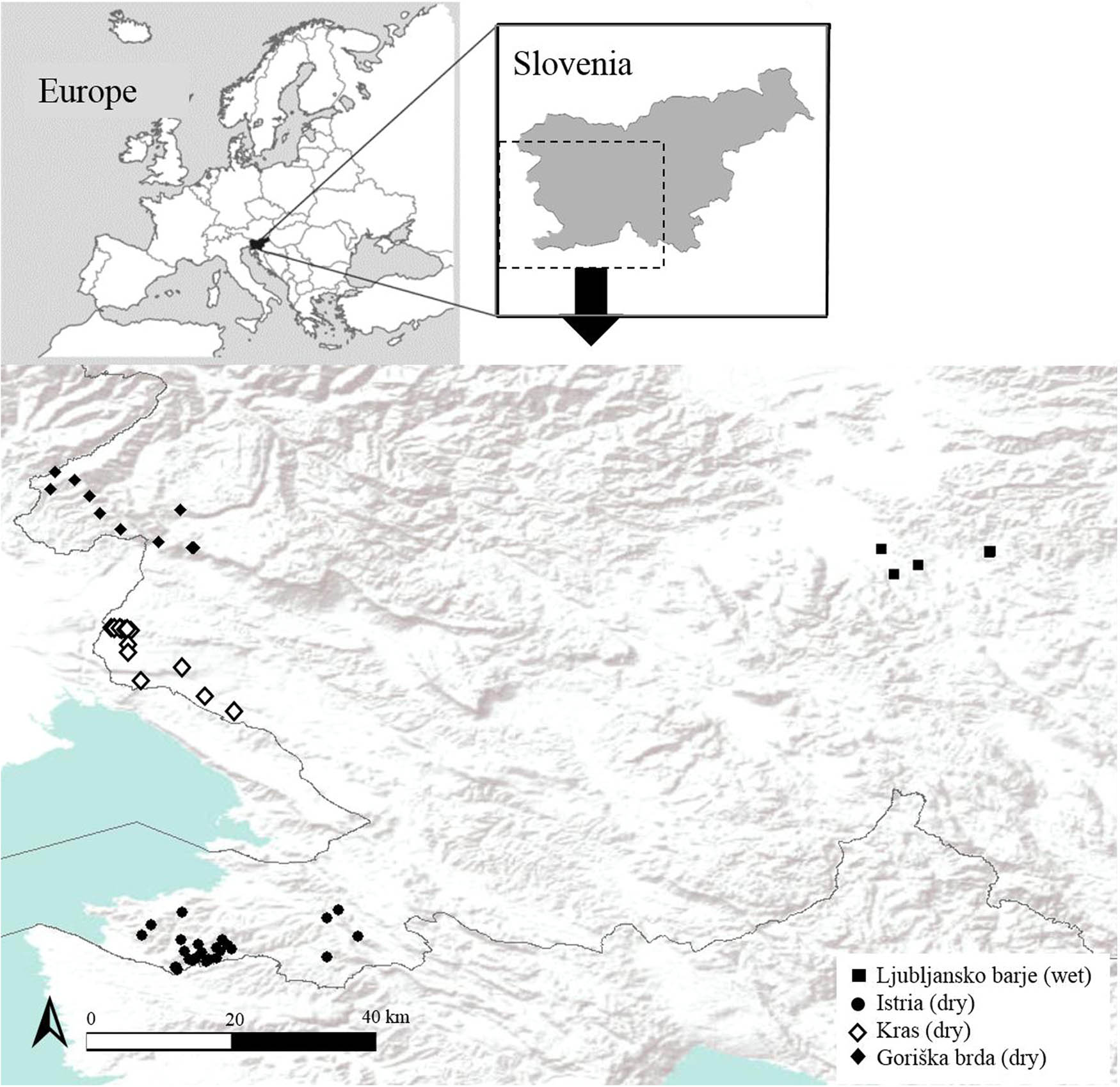

Coenonympha oedippus is one of the few European butterfly species inhabiting semi-open wet grasslands (most populations) and dry habitats in the southern range populations (exclusively in Italy, Slovenia and Croatia) [38,39,40]. Slovenia is unique, as here C. oedippus occupies both habitat types. Interestingly, studied habitat types are also geographically distinctive; wet habitats are present only in central Slovenia (in south-eastern part of Ljubljansko barje), whereas dry habitats occur in Istria and western Slovenia (Kras, Goriška brda, Banjšice, Trnovski gozd; Figure 1).

Map of localities for which environmental data was collected and where presence of C. oedippus was confirmed at least once in a period from 2002 to 2016 (see also Appendix A). Wet – wet habitat type; dry – dry habitat type; geographical regions are indicated by different symbols. As part of Goriška brda, two most eastern diamonds markings (from left to right) are Banjšice (one habitat patch) and Trnovski gozd (three habitat patches). Small map shows the geographical position of localities in Slovenia.

Difference between dry and wet habitats was ecologically confirmed in the plant species used as larval host plants [17,32] and in the preferred larval/egg-laying microlocations [32]. C. oedippus is a habitat specialist and its microhabitat selection is believed to be an adaptation to local environmental conditions. Study of morphological traits, conducted by Jugovic et al. [31], showed that in distinctive habitat types statistically significant differences in wing size and the relative area of eyespots on the hindwings of the species occur, which confirmed presence of ecotype dimorphism. Moreover, differences found in ecotypes were best explained by mean annual air temperature and abundance of host plants [31].

2.2 Data collection

Altogether, data on nine environmental parameters (Table 1) for description of landscape variability within and between the analysed geographical regions and two habitat types occupied by C. oedippus in Slovenia were collected. On online database E-prostor, data for digital elevation model (DEM 1) [41] were obtained and used to determine altitude, aspect and slope (in arbitrary used categories with a range of 5°, see Table 1) in ArcMap 10.4.1 [42]. An online environmental portal (E-tla) was used to acquire data for soil type, with classification based on World Reference Base for Soil Resources – WRB [43] and information for soil depth, soil texture class, pH in upper 30 cm of the soil and water accessibility in ground for plants. Data for these parameters are based on Ground Map Units – TKE (talne kartografske enote) of national soil maps, displayed at the scale 1:25,000 resolution [44]. The last parameter obtained from E-tla was land use where digital orthophoto maps recorded state-level land use on date 30 June 2015 [45].

A list of environmental parameters recorded at habitat patches of C. oedippus in Slovenia

| Parameter | Type | Categories/unita | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental parameters | |||

| Altitude | Numerical | Meters above sea level | DEM 1b [41] |

| Soil type | Categorical | 9 (mollic leptosol; rendzic leptosol; eutric cambisol; calcaric cambisol; chromic cambisol; eutric fluvisol; eutric gleysol; mollic gleysol; x-unknown) | WRBc, 1:25,000 [43] |

| Soil depth | Categorical | 3 (shallow soil – less than 15 cm; medium deep soil; deep soil – more than 100 cm) | TKEd, 1:25,000 [44] |

| Soil texture class | Categorical | 5 (clay loam; loam; silt loam; clay; silty clay) | TKEd, 1:25,000 [44] |

| pH in upper 30 cm of the soil | Categorical | 4 (acidic; medium acidic; highly acidic; neutral) | TKEd, 1:25,000 [44] |

| Water accessibility in ground for plants | Categorical | 4 (very low; low; moderate; medium) | TKEd, 1:25,000 [44] |

| Aspect | Categorical | 5 (flat; N |305° < azimuth < 45°|; E |45° < azimuth < 135°|; S |135° < azimuth < 225°|; W |225° < azimuth < 305°|) | DEM 1b [41] |

| Slope | Categorical | 5 (0°–5°; 5°–10°; 10°–15°; 15°–20°; >20°) | DEM 1b [41] |

| Land use | Categorical | 13 (marsh meadow; trees and shrubs; forest; intensive orchard; agricultural lands in process of overgrowing; agricultural lands overgrown with forest trees; abandoned agricultural lands; field; olive grove; built-up land; natural grassland; vineyard; water) | DOFe [45] |

| Timescale (before 2008 vs after 2013) | |||

| Vegetation cover | Categorical | 4 (agricultural areas; herb layer; shrubs; trees) | DOFf [45] |

| Habitat occupancy | Categorical | 4 (occupied by species; unoccupied; negative change – from occupied to unoccupied; positive change – from unoccupied to occupied) | [35,36]; field data |

- a

We followed categories from original source data, except in “slope” parameter, where data was divided in five categories statistical purposes.

- b

DEM 1 – digital elevation model.

- c

WRB – World Reference Base for Soil Resources. Classification on soil types is based on WRB, 1:25,000.

- d

TKE – ground map units; based on national soil maps, 1:25,000.

- e

DOF – digital orthophoto maps; state level land use record on date 6/30/2015.

- f

DOF – digital orthophoto maps with resolution DOF050 and DOF025 from time series; DOF 2006; DOF 2009–2011; DOF 2012–2014; DOF 2014–2015; DOF 2016.

Data were collected for all known Slovenian localities of the species since 2002; however, few localities outside the analysed geographical regions where species gone extinct in the past [16] were excluded. In total, 56 habitat patches were included in the analysis. It should be noted that in cases where habitat patches were heterogeneous for a particular studied parameter, two categories were assigned to a single habitat patch; however, for land use ([45]; see Table 1), up to five categories were assigned to single locality because of mosaic character of landscapes.

Habitat suitability was determined with the presence of the species at each given habitat patch. Patches were checked before 2008 (between 2002 and 2008) and were visited again between 2013 and 2016. Undergoing changes in occupancy were determined between the two time intervals. Species presence was compared with period reports (ordered by the Ministry of the Environment and Spatial Planning) in 2009 and 2015 [35,36,39], and if species in specific habitat patch was not detected in any of combined data patch it was marked as “unoccupied”. Although it is impossible to assign any species absence without a doubt, several unsuccessful field trips joined with above-mentioned reported data and in some case inappropriate habitat/vegetation structure (see also [32]) allowed us to conclude the species’ absence with reasonably low risk, especially as in many cases species had not been found at a certain habitat patch for more years in a row. Digital orthophoto maps with ground sampling distance 0.50 m (DOF050) and 0.25 m (DOF025) from time series 2006, 2009–2011, 2012–2014, 2014–2015, 2016 [45] and field trips were applied to determine changes in vegetation cover between both periods and these changes were then linked to possible changes in habitat occupancy during the second monitoring period (between 2013 and 2016) at the peak of species flight season.

2.3 Data analysis

2.3.1 Variation of environmental parameters at habitat and geographical scale

First, we identified two levels of analysis based on occurrence of two ecotypes of C. oedippus (wet ecotype occurring exclusively in Ljubljansko barje, in text also named “wet habitat”, and dry ecotype occurring elsewhere) and geographical regions. Study species occurs in six mesoregions [8]: (i) Ljubljansko barje, (ii) Koprska brda (named as Istria in the following text), (iii) Kras, (iv) Goriška brda, (v) Kambreško with Banjšice and (vi) Trnovski gozd, Nanos and Hrušica. The latter two mesoregions (v and vi) were combined due to low sample size and are named as “Banjšice and Trnovski gozd” further on. Banjšice and Trnovski gozd are both high karst plateaus made predominantly of limestone; they lay in geographical vicinity and are split by the deeply cut Čepovanski dol valley [8]. Note that habitat patches from Banjšice and Trnovski gozd were included in “dry” habitat type in all analyses, whereas at a scale of geographical groups these data were excluded from statistical analysis due to small sample size (statistical analysis at a geographical scale was therefore performed on mesoregions i–iv alone).

Our final set of geographical regions with respective number of habitat patches (in brackets) included in the present study where C. oedippus occur therefore consisted of: Ljubljansko barje (7), Istria (25), Kras (13), Goriška brda (7), Banjšice (1) and Trnovski gozd (3).

Except for a single numerically measured parameter (altitude), for which a statistical description was made (median, minimum, maximum), for each of the defined geographical regions, also a Mann–Whitney test (for wet-dry) or Kruskal–Wallis test (for geographical regions) of median parameters’ values was performed to investigate for possible significant differences among them. Significance of differences was accepted at p < 0.05. Each of the remaining eight environmental parameters was categorised (Table 1) for the purpose of chi-square testing. The likelihood statistics with standardised residuals (SR > |2|) was used to determine particular cells that contribute significantly to the overall chi-square testing (p < 0.05) of regional and habitat differences. The likelihood ratio (LR) statistic was applied due to small sample sizes, which resulted, in some cases, in expected frequencies lower than 1. Moreover, the chi-square test of homogeneity was applied to test for (non-)uniform distribution of each environmental parameter categories, which were present with frequencies higher than 0, within each region and habitat type.

2.4 Changes in vegetation cover and occupancy in time

Differences in vegetation cover between the two time periods (before 2008 and after 2013) were calculated for each region and habitat type. Occupancy (as occupied/unoccupied) by C. oedippus was determined for each habitat type and time period. Three possible outcomes between the two periods (no change [occupied/unoccupied in both periods], positive change [unoccupied to occupied] and negative change [occupied to unoccupied]) were discussed according to changes in vegetation cover and land use.

3 Results

3.1 Variation of environmental parameters at habitat and geographical scale

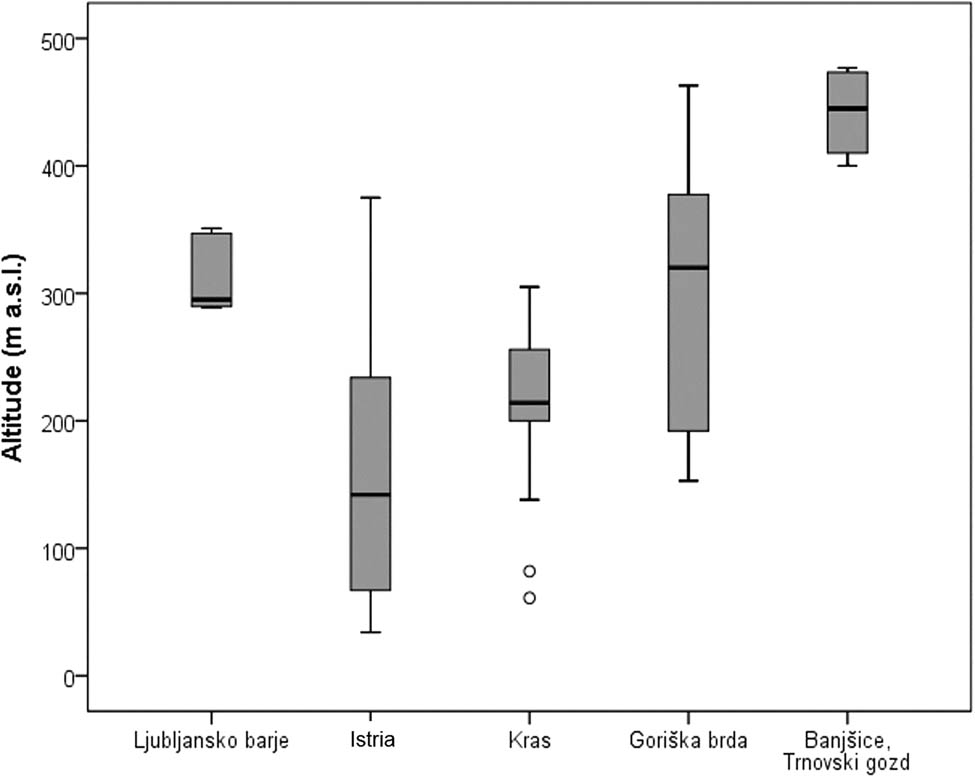

There are statistically significant differences in altitude between wet and dry habitats (Mann–Whitney test, U = 72; p = 0.01) as well as among four geographical regions (Kruskal–Wallis test, χ2 = 17.4, df = 3; p < 0.001). In wet habitat, C. oedippus occurs between 289 and 351 m a.s.l. (median = 295 m) and in dry habitats, a species inhabits patches between 34 and 477 m a.s.l. (median = 207 m) (Figure 2). While the variability of altitude was the lowest in wet habitat, it was more diverse in other three geographical regions. Within the complex of Trnovski gozd – Banjšice (median = 445 m), all known habitat patches lay above 400 m a.s.l., followed by Goriška brda where majority of (except one locality at 463 m a.s.l.) habitat patches are lower than 400 m a.s.l. In Kras (median = 214 m), altitude of habitat patches extends from 61 to 305 m a.s.l. and Istria has the lowest median value (142 m).

Altitude of C. oedippus habitat patches in five geographical regions in Slovenia. Note that data for Banjšice and Trnovski gozd were merged as they are geographically close and geologically indistinctive. Specific data for three habitat patches from Trnovski gozd are 400, 420 and 477 m a.sl. and from Banjšice, a known habitat patch, is at 470 m a.s.l.

Significant differences (p < 0.05) between the four geographical regions (Ljubljansko barje, Istria, Kras, Goriška brda) are in seven, and for two ecotypes (wet and dry) in five environmental parameters. All parameters, with the exceptions for pH and water accessibility for plants at ecotype level and land use in both levels, were different among geographical regions and habitat types (Table 2).

Differences among environmental parameters in geographical regions and habitat types estimated with chi-square testing. LR – likelihood statistics; df – degrees of freedom; p – statistical significance

| Parameters | Geographical regions | Habitat types | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LR | df | p | LR | df | p | |

| Soil type | 106.197 | 24 | *** | 43.223 | 8 | *** |

| Soil depth | 40.110 | 6 | *** | 6.739 | 2 | * |

| Soil texture class | 39.576 | 12 | *** | 17.711 | 4 | *** |

| pH in upper 30 cm of the soil | 23.793 | 9 | ** | 5.411 | 3 | NS |

| Water accessibility in ground for plants | 29.798 | 9 | *** | 0.580 | 3 | NS |

| Aspect | 24.218 | 12 | * | 11.196 | 4 | * |

| Slope | 40.287 | 12 | *** | 11.108 | 4 | * |

| Land use | 42.516 | 36 | NS | 20.671 | 12 | NS |

***p < 0.001; **p < 0.01; *p < 0.05; NS, not significant.

All environmental parameters were further on tested for homogeneity, where in dry habitat type (corresponding to summarisation of data for Istria, Kras, Goriška brda, Trnovski gozd and Banjšice), all parameters with an exception of slope (which was insignificant also in all four geographical regions) deviated significantly from uniform distribution (Table 3). Exceptionally, in Ljubljansko barje (wet habitat), none of eight environmental parameters were significant for homogeneity. Among other geographical regions, six parameters were found in Istria, four in Kras and only one in Goriška brda (Table 3), which significantly deviated from homogenous distribution (p < 0.05). Parameters exhibiting significance the most (i.e. at least in two regions) are soil type, depth, texture class and pH in upper 30 cm of the soil. For each of eight parameters at regional and habitat scales, predominant categories were defined (Table 3). Standard residuals showed which categories contributed significantly to the overall chi-square testing (p < 0.05) in each tested parameter (Appendix A).

Chi-square test for homogeneity within geographical regions and habitat types with predominant categories for each parameter. Abbreviation: p – statistical significance

| Parameters | Istria | Kras | Goriška brda | Ljubljansko barje/WET | DRY | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p | Predominantly | p | Predominantly | p | Predominantly | p | Predominantly | p | Predominantly | |

| Soil type | *** | Eutric (38.7%) and calcaric (38.7%) cambisol | ** | Rendzic leptosol (92.9%) | NS | Rendzic leptosol (57.1%) | NS | Eutric (50%) gleysol | *** | Rendzic leptosol (33.9%) and eutric cambisol (28.6%) |

| Soil depth | *** | Medium deep soil (75.9%) | ** | Shallow soil (92.9%) | NS | Medium deep soil (57.1%) | NS | Medium deep soil (71.4%)/deep soil (28.6%) | ** | Medium deep (50%) to shallow soil (38.9%) |

| Soil texture class | ** | Clay loam (48.8%) and silt loam (44.2%) | ** | Silt loam (92.9%) | NS | Silt loam (70%) | NS | Silt loam (50%)/clay (25%)/silt clay (25%) | *** | Silt loam (60.6%) and Clay loam (33.8%) |

| pH in upper 30 cm of the soil | *** | Neutral (76.7%) | NS | Neutral (57.1%) | ** | Medium acidic (57.1%) | NS | Acidic (50%), medium acidic (25%) and neutral (25%) | *** | Neutral (58.2%) |

| Water accessibility in ground for plants | NS | Moderate (51.6%) | ** | Medium (92.3%) | NS | Medium (42.9%) | NS | Medium (50%) | *** | Medium (47.3%) to moderate (32.7%) |

| Aspect | *** | South (56%) and west (24%) | NS | North (38.5%) and west (30.8%) | NS | South (57.1%) | NS | South (71%) and flat (28.6%) | *** | South (42.9%) and west (26.5%) |

| Slope | NS | Highly diverse; more than 20° (36%) | NS | Up to 10° (77%) | NS | More than 20° (85.7%) | NS | Under 5° (57.1%) | NS | Highly diverse; more than 20° (32.7%) |

| Land use | *** | Mosaic landscape (none more than 24%) | NS | Agricultural lands in process of overgrowing (24.2%) | NS | Mosaic landscape (none more than 24%) | NS | Natural grassland (50%) and marsh meadows (25%) | *** | Mosaic landscape (none more than 24%) |

***p < 0.001; **p < 0.01; *p < 0.05; NS, not significant.

Predominant soil type categories were eutric (38.7%) and calcaric cambisol (38.7%, SR = 2.3) in Istria (p < 0.001) and rendzic leptosol in Kras (p < 0.01) and Goriška brda (92.9% and 57.1%, respectively). All three soil types represent most common soil types (83.9%, p < 0.001) at dry habitat type, with highest percentage of rendzic leptosol (33.9%) among them. In Istria, rendzic leptosol is not present, which significantly deviates from other dry regions (SR = −3.0). In Goriška brda, however, rendzic leptosol appears more frequently than it is expected (SR = 4.5). In wet habitat eutric gleysol is most common soil type (SR = 4.1), which together with mollic gleysol (SR = 3.4) characterise wetlands soils best (75%). Furthermore, no leptosol, cambisol or fluvisol was detected in wet habitat, whereas there was a complete lack of gleysol in Kras and Goriška brda.

Deepest soils among geographical regions were recorded in Ljubljansko barje, where medium deep (71.4%) and deep (28.6%) soils prevail and a complete lack of shallow soils was detected. In dry habitat type, medium deep (50%) to shallow soils (38.9%) were significantly most common (p < 0.001). All three soil depth categories were recorded in Istria (p < 0.01) and Goriška brda. In Kras, shallow soil was significantly predominant (92.9%, SR = 4.3) and medium deep soil was less frequently present as expected (SR = −2.4). Istria in the other hand also significantly deviates from expected (SR = −2.3) with lack of shallow soils in comparison to other dry regions (Kras in Goriška brda).

Altogether five soil texture classes were observed; silt loam was predominant in both dry (60.6%, p < 0.001) and in wet (50%) habitats, and also in all four geographical regions, where only in Istria, also clay loam (48.8%, SR = 2.0) was represented in significantly high percentage. Furthermore, only in wet habitat high percentage of loam (25%, SR = 2.0) and silty clay (25%, SR = 3.9) was recorded.

In dry habitats, pH in upper 30 cm of the soil was significantly neutral (58.2%, p < 0.001) and in wet habitats predominantly acidic (50%). Among geographical regions, however, Istria (p < 0.001) and Kras had highest percentage of neutral pH (75.9% and 57.1%, respectively) and Goriška brda had highest medium acidic pH (57.1%, SR = 2.2, p < 0.01). Istria significantly deviates from expected (SR = −2.1) with lack of medium acidic pH in comparison to other dry regions (Kras and Goriška brda).

Water accessibility in ground for plants is medium (47.3%) to moderate (32.7%) and significant (p < 0.001) for dry habitat type. Wet habitat, Goriška brda and Kras have medium water accessibility, with 50%, 42.9% and 92.3% (SR = 2.6), respectively. In Istria, however, water accessibility was predominantly moderate (51.6%).

Differences in aspect of dry habitat type are significant with predominantly south (42.9%) and west (26.5%) orientation, where orientation in wet habitat type is mostly south (71%) or flat (28.6%, SR = 2.0). Within geographical regions, southern aspect is predominant in Istria and Goriška brda (56% and 57.1%). In Kras, however, west (30.8%) and north (38.5%) orientations prevail. There the representation of north orientation is significantly higher than expected among geographic regions (SR = 2.9).

Among studied parameters, slope is insignificant within each geographical region and both habitat types. Values for slope in wet habitat are predominantly under 5° (57.1%), in Kras up to 10° (77%) and in Istria and Goriška brda more than 20° (with 36% and 85.7%, respectively). Note that in Istria and dry habitat type all categories are represented, which indicates highly diverse terrain.

Land use in wet habitat divided most localities as natural grasslands (50%) and marsh meadows (25%, SR = 5.1), whereas land use in most of dry habitats (Istria and Goriška brda) has mosaic character (as none of the categories has more than 24%). Similar land use was found in Kras, where only one category of land use (agricultural lands in process of overgrowing) exhibits slightly higher percentage than 24%.

3.2 Changes in vegetation cover and occupancy in time

Dynamics of change in vegetation cover and occupancy through time differentiated among geographical regions and habitat types (Table 4). In Istria, an increase of 2.56 ha was detected as newly transformed land for agricultural use. High increase in trees (for factor of 6) was also present and consequently a decrease in herbs and shrubs appeared. In Kras, no change in agricultural use was detected in studied habitat patches in two time periods. Decrease in herbs was present and connected with increase of shrubs and trees. In Goriška brda, the main factor of change is agricultural use as 4.77 ha of meadows was newly transformed into agricultural lands on account of herbs and shrubs (trees in lower proportions).

Changes in vegetation cover (in hectares) among two studied time intervals; difference is given in hectares and as factor of change (1: no change; 0–1: decrease; > 1: increase). LB – Ljubljansko Barje

| N | Agricultural use | Herbs | Shrubs | Trees | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2008 | 2013 | Diff. | Factor | 2008 | 2013 | Diff. | Factor | 2008 | 2013 | Diff. | Factor | 2008 | 2013 | Diff. | Factor | ||

| Istria | 25 | 3.15 | 5.71 | 2.56 | 1.81 | 31.95 | 30.87 | −1.08 | 0.97 | 10.36 | 6.69 | −3.67 | 0.65 | 0.44 | 2.62 | 2.19 | 6.02 |

| Kras | 13 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 4.13 | 3.38 | −0.75 | 0.00 | 2.39 | 2.63 | 0.24 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.51 | 0.51 | 0.00 |

| Goriška brda | 7 | 0.89 | 5.66 | 4.77 | 6.34 | 5.65 | 1.44 | −4.21 | 0.25 | 1.68 | 2.11 | 0.44 | 1.26 | 5.71 | 4.72 | −0.99 | 0.83 |

| Dry (d) | 49 | 4.04 | 11.38 | 7.34 | 2.82 | 43.76 | 37.90 | −5.86 | 0.87 | 15.80 | 12.68 | −3.12 | 0.80 | 6.25 | 7.89 | 1.64 | 1.26 |

| LB/Wet (w) | 7 | 0.77 | 0.77 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 13.04 | 12.01 | −1.03 | 0.92 | 1.17 | 2.11 | 0.94 | 1.80 | 0.18 | 0.27 | 0.09 | 1.50 |

| SUM (w + d) (ha) | 56 | 4.82 | 12.15 | 7.34 | 2.52 | 56.80 | 49.91 | −6.88 | 0.88 | 16.97 | 14.79 | −2.18 | 0.87 | 6.44 | 8.17 | 1.73 | 1.27 |

A high percentage of dry habitats suitable for C. oedippus was lost mostly due to agricultural use on one hand and increase of trees on suitable patches on other. In wet habitat, changes in vegetation cover mostly appeared due to increase of shrubs and trees (and decrease in herb layer on the other hand). Agricultural use of habitat patches did not change in studied time periods.

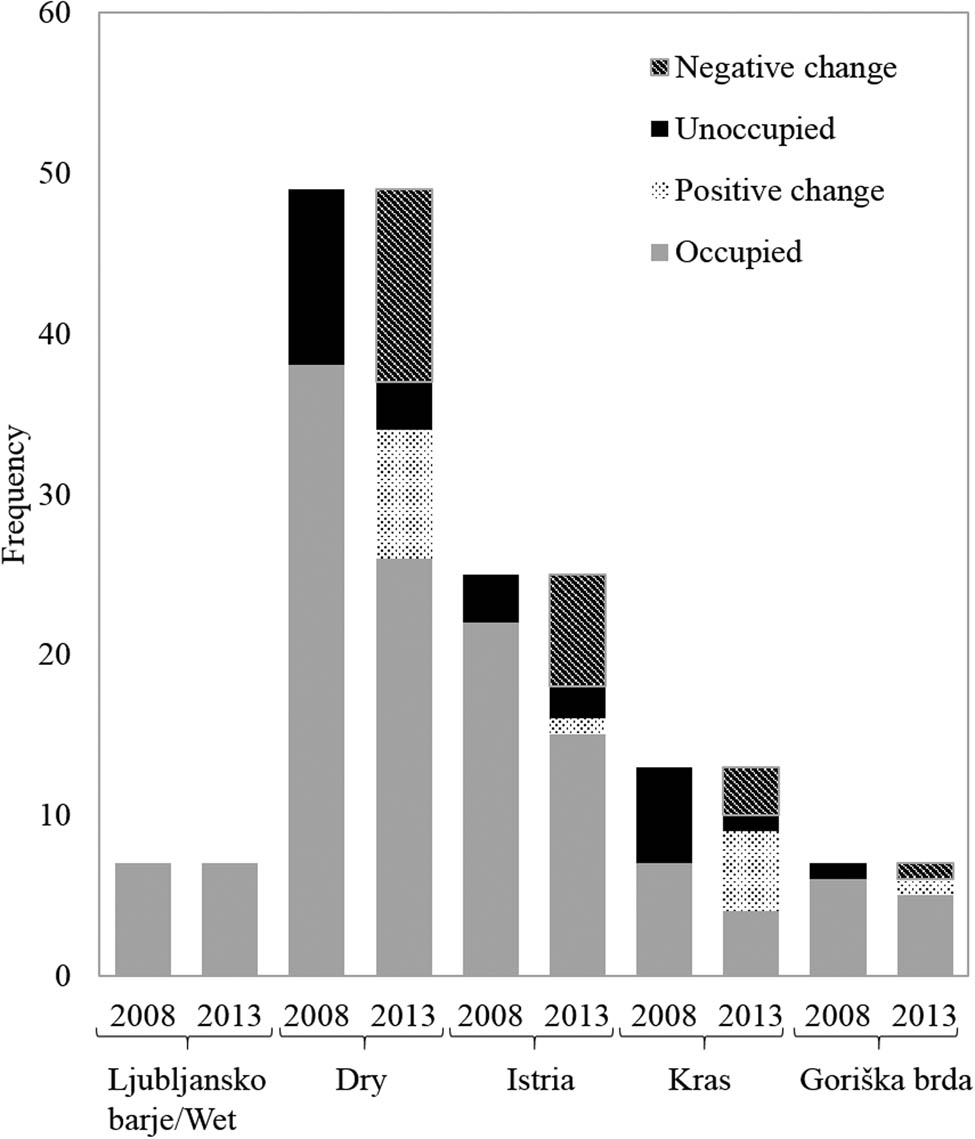

In total, a decrease in occupied habitat patches was detected in a period between the two time intervals (before 2008 versus after 2013). Whereas no changes in presence of C. oedippus were detected within wet habitat (Figure 3), this habitat type remains most sparsely populated area for the species in Slovenia. In more diverse dry habitat type, loss of suitable habitat patches over the time has been noted. Moreover, this loss seems greater than the emergence of newly detected suitable (and thus occupied) habitat patches (Figure 3). All that resulted in a sharp decline in populated habitat patches in the studied time frame, which equals to 31.6% of decrease in number of populated habitat patches during the second inventory period. In particular, Istria showed highest decrease due to negative changes between the two time inventories, whereas in Kras, some newly created/found suitable habitat patches with C. oedippus at least seemingly lowered the overall decrease in C. oedippus presence in the area (Figure 3).

Changes in habitat occupancy in two time periods (before 2008 and after 2013).

4 Discussion

4.1 Variation of environmental parameters at habitat and geographical scales

The variety of habitats in Slovenia suitable for Coenonympha oedippus is unique, same as the diversity of landscapes where the species can be found. Highest altitude for historical and present distribution for most localities of C. oedippus in Europe is 700 m a.s.l., with majority of altitude records defining species thermophilic and colline [10,37,40,46,47,48]. In Europe, altitude functions as a barrier for species dispersal as mountain ranges restrict gene flow [46]. Its presence in Slovenia was confirmed exclusively in altitudes below 400 m [10,16,49,50], with only one data in higher altitudes from Čaven at 1,100–1,250 m a.s.l. [31,51]. Altitudes in our data set ranges from 34 to 477 m a.s.l., with most diverse altitudes (by data range and median) in Istria and Goriška brda. Most Istrian habitat patches lay nearby Adriatic coast in the valley of Dragonja River and in nearby slopes explaining the lowest median altitude among all herein investigated geographical regions. The highest median altitude for C. oedippus from Slovenia is in hilly terrain of Goriška brda (and Banjšice and Trnovski gozd plateaus). Altitude is an important element when studying species distribution; however, this alone is not enough to define thermophilic profile of a given habitat patch. Mean annual air temperature and abundance of host plants were shown to explain best differences found in ecotypes [31]. However, we think the persistence of species in high altitude may be possible due to overall warmer conditions (i.e. orientation of the two plateaus towards the warmer Vipavska dolina and never orientated towards north) which could compensate for higher altitudes. Istria and Goriška brda both have rugged and diverse terrain [52], which is confirmed also by slope parameters mainly above 20°. Habitat patches in this two regions are predominantly south orientated, especially in habitat patches where slope is above 20° this acts as a rule, which enables higher similarity of microclimatic aspects among different localities/regions. Furthermore, in Goriška brda and Istria temperature inversions in winter time are not uncommon phenomena, which could also contribute to the survival of overwintering larvae at higher altitudes in both regions as well as in Trnovski gozd and Banjšice plateaus. In contrast, most C. oedippus habitat patches in Kras are in levelled terrain (<10°) and predominantly orientated towards north (in 38.5%). Despite northern aspects, the orientation here plays a minor role in species persistence as more important factors are lower altitude and lack of temperature inversion during the winter. For wet habitat temperature, inversions are common; however, species here is probably better adapted to more severe winters (wet ecotype) hence this effect may play only a minor role in species persistence.

Soil formation and development is influenced by many factors and processes including bedrock, relief, climate, water, wildlife and time, which in combination is often difficult to generalise [53]. From a butterfly perspective, water accessibility (associated with precipitation and water retention) is crucial not only for ground plants but also for vegetation cover in general. A flysch is a quickly mechanically weathering bedrock, hence thicker (medium deep) soils evolve in Istria and Goriška brda (both dry habitats) where this type of bedrock is most common. The soil there (e.g. eutric cambisol present in both regions) is due to fine porosity (clay loam and silt loam, however with varying proportions) and weak water permeability more humid [54]. Kras lays on limestone bedrock that is predominantly weathering chemically, and the insoluble residue forms the basis of the shallow rendzic leptosol soil under which the permeable substrate lies. This is mirrored in lower availability of water; nevertheless, the finer texture could reflect positively on water retention. On the other hand, in wet habitat, soils are common for wetlands as they develop on impermeable alluvial clay sediments. Pores in soil are filled with water and therefore the reduction processes, rather than the oxidation ones, predominate. Hence, deeper soils (i.e. eutric and mollic gleysol) with silt loam, silty clay and loam texture classes dominate. Wet ecotype seemingly prefers habitats with this type of soils, however this cannot be extrapolated outside the study area as for species microhabitat (e.g. feeding plants) is of crucial importance [32].

Freshness and nutrient content of larval host plants (for both being hypothesised to be higher in connection to high water accessibility) [55,56] are in tight connection with soil parameters, including pH. Soil pH predicts soil water repellence based on water content and soil temperature, which defines wettability of soil and further also stability of soil organic matter (controlled also by nutrient availability and oxygen) [57,58,59,60]. As a result, C. oedippus has been shown to maturate at lower size in dry habitats than in wet habitats from Slovenia [31]. According to our results water accessibility in Istria is the lowest (i.e. class moderate), whereas in three other regions is in medium scale. It would be expected that at least in wet habitat water accessibility would be higher than in other regions according to mostly acidic pH, moderate continental climate (yearly precipitation quantities approx. 1,500 mm) and higher clay content in soil. We presume that parameters would differ if area would not be heavily affected with agricultural activities with effective drainage system. While lowest water accessibility in Istria is in line with results considering lower precipitation (950 mm/year), the distribution of precipitation throughout the year could hold main difference as it is more pronounced among dry and wet months (moderate Mediterranean climate). Although Kras and Goriška brda exhibit similar (medium) water accessibility, there are further indices for a bit higher water accessibility in Kras relatively to Goriška brda. Both areas have precipitation quantities of Mediterranean climate type (approx. 1,500 mm/year). However, difference in pH depends on the carbonate properties of the soil. Kras exhibits neutral pH (limestone bedrock), whereas Goriška brda exhibits medium acidic pH (binder material of flysch bedrock have more acidic properties) [54]. Comparison of given combinations insinuate higher water accessibility for Goriška brda, which is not in concordance with gained results of higher water accessibility in Kras. Slope, which accelerates water run-off [53], also affects water accessibility. Kras is relatively levelled in comparison with highly diverse slopes of Goriška brda (predominantly more than 20°) and for that reason in the latter retention/accessibility of water may be smaller than in Kras. Further possible factor could be vegetation cover that in studied habitat patches is more complex in Kras than in Goriška brda (pers. obs.).

Slope is one of the main determinants for land use and it is defining favourable conditions for agriculture [52,61]. This may be important in levelled and flat terrain such as wet habitat (mainly southerly oriented slope <5°), where intensification of agriculture owing the favourable conditions severely limits the abundance of suitable habitat patches for C. oedippus. Similar phenomena are noticeable in more levelled parts of Istria and Goriška brda, thus not in Kras, where predominantly forested area occurs.

Finally, we need to stress out that we can usefully apply extrapolated data from larger topographic maps; however, we need to consider that each habitat patch can have its specific microclimatic conditions. For endangered species, which is also limited by larval host availability is crucial to understand microclimatic conditions and its microhabitat. However, from practical point of view to survey each habitat patch thoroughly is highly time-consuming and for species with such fast decline practically impossible.

4.2 Impact of changes of vegetation cover and occupancy in time

Dynamics of change in vegetation cover in studied time periods (2002–2008 versus 2013–2016) exhibits different outcomes for four regions. Once open grasslands were abandoned during the last decades and due to lack of grazing and maintenance (e.g. occasional mowing), many have already transformed to forests. On the contrary, most of landscapes appropriate for agricultural use were transformed into agricultural lands (mostly olive groves and vineyards). With loss of open grasslands in Istria, mainly due to overgrowing processes (shrubs were replaced with thicker vegetation cover – trees, increased for the factor of 6.02, until second studied period) and in smaller proportion transformation of meadows (herbs and partly shrubs increased for the factor of 1.81) into agricultural land, also decrease of occupancy with C. oedippus was detected. In Istria there is as much as 54% (corresponding to 45.89 ha) of all herein included Slovenian known habitat patches of C. oedippus. In Goriška brda main factor of change was agricultural use for factor 6.34 and secondly increase in proportion of shrub and trees was detected in smaller part, which is effect in contrast with one detected in Istria. Mainly meadows were not changed due to overgrowing processes (smaller portion) rather to intensification of agriculture, as Goriška brda represents one of important vineyard areas in Slovenia. Altogether occupancy change was not severe as some of former (in 2008) unoccupied habitat patches were occupied in 2013 and some (up to same degree) were facing negative change. In Kras, another dry geographical region, only processes of overgrowing of the meadows were detected; this influences species negatively as it needs open habitats up to light wood habitat (e.g. caterpillars like to sunbathe [32]). The area where species appears is the smallest among dry habitats (only 6.52 ha); however, broader view of this area exhibit mosaic character of formerly used agricultural land that is slowly overgrowing, which in first steps also creates patches suitable for C. oedippus, and enables stepping stone environment for butterfly which enhances survival probabilities. All dry habitats together were therefore mainly changed due to intensified agricultural practices and somewhat less due to meadows overgrowing. In wet habitat major change in vegetation cover was due to intensification of agriculture land and due to higher abundance of trees. In this area, agriculture practise is severe and therefore hardly any uncultivated land is left. In meadows which C. oedippus occupies special attention is given to processes of overgrowing (a lot of shrubs are being cut regularly) to ensure species persistence. According to Čelik [39], in the period 2001–2014, area of wet habitat patches decreased for 86% (from 48 to 7 ha) and population of C. oedippus is under minimal viable population threshold.

5 Conclusions

Species past distribution was much larger and nowadays C. oedippus could still be frequently found at mountain foothills as its wider distribution was severely affected from intensive agriculture development, land draining and urbanisation since the early twentieth century throughout Europe, especially in western Europe [46,62]. Wetlands in Slovenia were deteriorated from intensification of agriculture (destruction, fragmentation and/or degradation of habitat quality, premature mowing, grassland burning and urbanisation), whereas oligotrophic grasslands (western part of Slovenia) suffered mostly from abandonment of traditional practices (extensive agriculture) and consequent overgrowing of meadows. Further on, C. oedippus is geographically isolated and persists in small populations size, exhibits low dispersal potential of adult butterflies and have specific ecological needs, which have synergic influence on increase of vulnerability of populations. Finally, in case that positive change was to some extent erroneously detected (i.e. in terms that the occupancy of habitat patches was detected in 2013 for the first time but was neglected before), the decline is even more severe than pointed out by the data. In any case, an overall extremely small number of remaining suitable (and occupied) habitat patches in wet habitat and fast disappearance of suitable and occupied habitat patches in dry habitat type for this highly endangered butterfly species confront the decision makers with highly responsible and quick and proper acting.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by (i) the STARBIOS2 European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Program (No. 709517); (ii) the RESBIOS European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Program (No. 872146) and (iii) the Slovenian Research Agency (P1-0386). Authors of the paper would like to thank Tatjana Čelik (ZRC SAZU) for providing valuable information regarding the studied endangered species.

Appendix A:

The likelihood statistics with standardised residuals (SR > |2|) to determine significant contributors to the overall chi-square testing (p < 0.05) of regional and habitat differences

| Geographical regions/parameters | Istria | Kras | Goriška brda | Ljubljansko barje/Wet | Dry | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % within region | SR | N | % within region | SR | N | % within region | SR | N | % within region | SR | N | Within region | SR | |

| Soil type | |||||||||||||||

| Calcaric Cambisol | 12 | 38.7% | 2.3 | 0 | 0.0% | −1.7 | 0 | 0.0% | −1.2 | 0 | 0.0% | −1.3 | 12 | 21.4% | 0.5 |

| Chromic Cambisol | 0 | 0.0% | −1.0 | 1 | 7.1% | 0.8 | 1 | 14.3% | 1.6 | 0 | 0.0% | −0.5 | 1 | 1.8% | 0.1 |

| Eutric Cambisol | 12 | 38.7% | 1.8 | 0 | 0.0% | −1.8 | 2 | 28.6% | 0.3 | 0 | 0.0% | −1.4 | 16 | 28.6% | 0.5 |

| Eutric Fluvisol | 4 | 12.9% | 1.3 | 0 | 0.0% | −1.0 | 0 | 0.0% | −0.7 | 0 | 0.0% | −0.7 | 5 | 8.9% | 0.3 |

| Eutric Gleysol | 1 | 3.2% | −1.0 | 0 | 0.0% | −1.1 | 0 | 0.0% | −0.8 | 4 | 50.0% | 4.1 | 1 | 1.8% | −1.6 |

| Mollic Gleysol | 0 | 0.0% | −1.0 | 0 | 0.0% | −0.7 | 0 | 0.0% | −0.5 | 2 | 25.0% | 3.4 | 0 | 0.0% | −1.3 |

| Mollic Leptosol | 2 | 6.5% | 1.0 | 0 | 0.0% | −0.7 | 0 | 0.0% | −0.5 | 0 | 0.0% | −0.5 | 2 | 3.6% | 0.2 |

| Rendzic Leptosol | 0 | 0.0% | −3.0 | 13 | 92.9% | 4.5 | 4 | 57.1% | 1.4 | 0 | 0.0% | −1.5 | 19 | 33.9% | 0.6 |

| X | 0 | 0.0% | −1.0 | 0 | 0.0% | −0.7 | 0 | 0.0% | −0.5 | 2 | 25.0% | 3.4 | 0 | 0.0% | −1.3 |

| Soil depth | |||||||||||||||

| Shallow soil | 2 | 6.9% | −2.3 | 13 | 92.9% | 4.3 | 2 | 28.6% | −0.1 | 0 | 0.0% | −1.4 | 21 | 38.9% | 0.6 |

| Medium deep soil | 22 | 75.9% | 1.4 | 1 | 7.1% | −2.4 | 4 | 57.1% | 0.0 | 5 | 71.4% | 0.5 | 27 | 50.0% | −0.2 |

| Deep soil | 5 | 17.2% | 0.5 | 0 | 0.0% | −1.4 | 1 | 14.3% | 0.0 | 2 | 28.6% | 1.0 | 6 | 11.1% | −0.4 |

| Soil texture class | |||||||||||||||

| Clay | 0 | 0.0% | −0.8 | 1 | 7.1% | 1.9 | 0 | 0.0% | −0.4 | 0 | 0.0% | −0.3 | 1 | 1.4% | 0.1 |

| Clay loam | 21 | 48.8% | 2.0 | 0 | 0.0% | −2.1 | 3 | 30.0% | −0.1 | 0 | 0.0% | −1.6 | 24 | 33.8% | 0.5 |

| Loam | 3 | 7.0% | 0.1 | 0 | 0.0% | −1.0 | 0 | 0.0% | −0.8 | 2 | 25.0% | 2.0 | 3 | 4.2% | −0.7 |

| Silty clay | 0 | 0.0% | −1.1 | 0 | 0.0% | −0.6 | 0 | 0.0% | −0.5 | 2 | 25.0% | 3.9 | 0 | 0.0% | −1.3 |

| Silt loam | 19 | 44.2% | −1.1 | 13 | 92.9% | 1.8 | 7 | 70.0% | 0.5 | 4 | 50.0% | −0.3 | 43 | 60.6% | 0.1 |

| pH in upper 30 cm of the soil | |||||||||||||||

| Neutral | 23 | 76.7% | 1.4 | 8 | 57.1% | 0.0 | 1 | 14.3% | −1.5 | 2 | 25.0% | −1.2 | 32 | 58.2% | 0.4 |

| Acidic | 5 | 16.7% | −0.4 | 1 | 7.1% | −1.1 | 2 | 28.6% | 0.5 | 4 | 50.0% | 1.9 | 8 | 14.5% | −0.8 |

| Medium acidic | 1 | 3.3% | −2.1 | 5 | 35.7% | 1.3 | 4 | 57.1% | 2.2 | 2 | 25.0% | 0.3 | 14 | 25.5% | 0.0 |

| Highly acidic | 1 | 3.3% | 0.7 | 0 | 0.0% | −0.5 | 0 | 0.0% | −0.3 | 0 | 0.0% | −0.4 | 1 | 1.8% | 0.1 |

| Water accessibility in ground for plants | |||||||||||||||

| Very low | 0 | 0.0% | −0.7 | 1 | 7.7% | 1.7 | 0 | 0.0% | −0.3 | 0 | 0.0% | −0.4 | 1 | 1.82% | 0.1 |

| Low | 8 | 25.8% | 0.7 | 0 | 0.0% | −1.6 | 2 | 28.6% | 0.5 | 2 | 25.0% | 0.3 | 10 | 18.2% | −0.1 |

| Moderate | 16 | 51.6% | 1.7 | 0 | 0.0% | −2.1 | 2 | 28.6% | −0.2 | 2 | 25.0% | −0.4 | 18 | 32.7% | 0.1 |

| Medium | 7 | 22.6% | −1.8 | 12 | 92.3% | 2.6 | 3 | 42.9% | 0.0 | 4 | 50.0% | 0.3 | 26 | 47.3% | 0.0 |

| Aspect | |||||||||||||||

| E | 3 | 12.0% | 0.4 | 1 | 7.7% | −0.2 | 1 | 14.3% | 0.4 | 0 | 0.0% | −0.8 | 8 | 16.3% | 0.4 |

| FLAT | 1 | 4.0% | −0.7 | 1 | 7.7% | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0% | −0.7 | 2 | 28.6% | 2.0 | 2 | 4.1% | −0.8 |

| N | 1 | 4.0% | −1.1 | 5 | 38.5% | 2.9 | 0 | 0.0% | −0.9 | 0 | 0.0% | −0.9 | 5 | 10.2% | 0.3 |

| S | 14 | 56.0% | 0.6 | 2 | 15.4% | −1.7 | 4 | 57.1% | 0.3 | 5 | 71.4% | 0.9 | 21 | 42.9% | −0.4 |

| W | 6 | 24.0% | 0.1 | 4 | 30.8% | 0.6 | 2 | 28.6% | 0.3 | 0 | 0.0% | −1.3 | 13 | 26.5% | 0.5 |

| Slope | |||||||||||||||

| 0⁰–5⁰ | 5 | 20.0% | −0.5 | 4 | 30.8% | 0.4 | 0 | 0.0% | −1.3 | 4 | 57.1% | 1.7 | 8 | 16.3% | −0.8 |

| 5⁰–10⁰ | 3 | 12.0% | −0.6 | 6 | 46.2% | 2.5 | 0 | 0.0% | −1.1 | 0 | 0.0% | −1.1 | 10 | 20.4% | −0.3 |

| 10⁰–15⁰ | 3 | 12.0% | −0.4 | 3 | 23.1% | 0.7 | 0 | 0.0% | −1.0 | 2 | 28.6% | 0.9 | 7 | 14.3% | 0.0 |

| 15⁰–20⁰ | 5 | 20.0% | 0.9 | 0 | 0.0% | −1.3 | 1 | 14.3% | 0.1 | 1 | 14.3% | 0.1 | 8 | 16.3% | 0.4 |

| > 20⁰ | 9 | 36.0% | 0.7 | 0 | 0.0% | −1.9 | 6 | 85.7% | 2.8 | 0 | 0.0% | −1.4 | 16 | 32.7% | 0.5 |

| Land use | |||||||||||||||

| Marsh meadow | 0 | 0.0% | −1.0 | 0 | 0.0% | −0.7 | 0 | 0.0% | −0.6 | 2 | 25.0% | 5.1 | 0 | 0.0% | −1.4 |

| Trees and shrubs | 7 | 12.3% | 0.1 | 4 | 12.1% | 0.1 | 2 | 9.5% | −0.3 | 1 | 12.5% | 0.1 | 16 | 13.4% | 0.0 |

| Forest | 13 | 22.8% | 0.4 | 5 | 15.2% | −0.6 | 5 | 23.8% | 0.4 | 1 | 12.5% | −0.5 | 25 | 21.0% | 0.1 |

| Intensive orchard | 1 | 1.8% | 0.8 | 0 | 0.0% | −0.5 | 0 | 0.0% | −0.4 | 0 | 0.0% | −0.3 | 1 | 0.8% | 0.1 |

| Agricultural lands in process of overgrowing | 13 | 22.8% | 0.4 | 8 | 24.2% | 0.5 | 3 | 14.3% | −0.6 | 0 | 0.0% | −1.3 | 25 | 21.0% | 0.3 |

| Agricultural lands overgrown with forest trees | 0 | 0.0% | −1.0 | 2 | 6.1% | 1.9 | 0 | 0.0% | −0.6 | 0 | 0.0% | −0.4 | 2 | 1.7% | 0.1 |

| Abandoned agricultural lands | 4 | 7.0% | −0.4 | 5 | 15.2% | 1.3 | 1 | 4.8% | −0.6 | 0 | 0.0% | −0.8 | 10 | 8.4% | 0.2 |

| Field | 1 | 1.8% | 0.8 | 0 | 0.0% | −0.5 | 0 | 0.0% | −0.4 | 0 | 0.0% | −0.3 | 1 | 0.8% | 0.1 |

| Olive grove | 2 | 3.5% | 1.1 | 0 | 0.0% | −0.7 | 0 | 0.0% | −0.6 | 0 | 0.0% | −0.4 | 2 | 1.7% | 0.1 |

| Built up land | 5 | 8.8% | −0.1 | 2 | 6.1% | −0.6 | 4 | 19.0% | 1.5 | 0 | 0.0% | −0.9 | 11 | 9.2% | 0.2 |

| Natural grassland | 11 | 19.3% | −0.4 | 6 | 18.2% | −0.5 | 5 | 23.8% | 0.2 | 4 | 50.0% | 1.7 | 24 | 20.2% | −0.4 |

| Vineyard | 0 | 0.0% | −0.7 | 1 | 3.0% | 1.4 | 0 | 0.0% | −0.4 | 0 | 0.0% | −0.3 | 1 | 0.8% | 0.1 |

| Water | 0 | 0.0% | −0.7 | 0 | 0.0% | −0.5 | 1 | 4.8% | 2.0 | 0 | 0.0% | −0.3 | 1 | 0.8% | 0.1 |

References

[1] Ribeiro D, Šmid Hribar M. Assessment of land-use changes and their impacts on ecosystem services in two Slovenian rural landscapes. Acta Geogr Slov. 2019;2:144–59. 10.3986/AGS.6636.Search in Google Scholar

[2] Vos W, Klijn JA. Trends in European landscape development: prospects for a sustainable future. In: Klijn JA, Vos W, editors. From landscape ecology to landscape science. Proceedings of the European congress “Landscape ecology: things to do – proactive thoughts for the 21st century”, organised in 1997 by the Dutch Association for Landscape Ecology (WLO) on the occasion of the 25th anniversary. Dordrecht: Kluwer. 2000. p. 13–29.Search in Google Scholar

[3] Golobič M, Lestan KA. Potential impacts of EU policies on cultural landscape diversity: example of Slovenian coastal landscapes. Ann Istrian Mediterr Stud Ser Hist Sociol. 2016;26(2):193–210. 10.1111/1753-0407.12317.Search in Google Scholar

[4] Van Eetvelde V, Antrop M. Analyzing structural and functional changes of traditional landscapes – two examples from Southern France. Landsc Urban Plan. 2004;67(1–4):79–95. 10.1016/S0169-2046(03)00030-6.Search in Google Scholar

[5] Šilc U, Vreš B, Čelik T, Gregorič M. Biodiversity of Slovenia. In: Perko D, Ciglič R, Zorn M, editors. The Geography of Slovenia World Regional Geography Book Series. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2020.10.1007/978-3-030-14066-3_7Search in Google Scholar

[6] Antrop M. Landscapes of the urban fringe. Acta Geogr Lovan. 1994;34:501–14.Search in Google Scholar

[7] Melik A. Slovenija: geografski opis (Slovenia: geographical description). Ljubljana: Slovenska matica; 1963.Search in Google Scholar

[8] Perko D. The regionalization of Slovenia [Regionalizacija Slovenije]. Acta Geogr Slov. 1998;38:12–57.Search in Google Scholar

[9] Perko D. Slovenia at the Junction of Major European Geographical Units. Založba ZRC: Association of the Geographical Societies of Slovenia; 2004. p. 11–20.Search in Google Scholar

[10] Verovnik R, Rebeušek F, Jež M. Atlas dnevnih metuljev (Lepidoptera: Rhopalocera) Slovenije [Atlas of Butterflies (Lepidoptera: Rhopalocera) of Slovenia]. Miklavž na Dravskem polju: Center za kartografijo favne in flore; 2012.Search in Google Scholar

[11] Perko D, Ciglič R. Slovenia’s landscapes. In: Perko D, Ciglič R, Zorn M, editors. The Geography of Slovenia World Regional Geography Book Series. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2020. 10.1007/978-3-030-14066-3_14.Search in Google Scholar

[12] Lestan KA, Penko Seidl N, Golobič M. Landscape heterogeneity as a tool for enhancing biodiversity. In: Halada Ľ, Bača A, Boltižiar M, editors. Institute of Landscape Ecology, Slovak Academy of Sciences. Slovakia: Nitra; 2016. p. 365. ISBN 978-80-89325-28-3.Search in Google Scholar

[13] Gabrovec M, Kumer P, Ribeiro D, Šmid Hribar M. Land use in Slovenia. In: Perko D, Ciglič R, Zorn M, editors. The Geography of Slovenia World Regional Geography Book Series. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2020. 10.1007/978-3-030-14066-3_18.Search in Google Scholar

[14] Čelik T. Stanje vlagoljubnih populacij barjanskega okarčka (Coenonympha oedippus) v Sloveniji. Vabljeno predavanje na 10. strokovnem posvetu z naslovom Ogrožene vrste Nature 2000 – stanje in izzivi. Ljubljana (invited lecture). Ljubljana, 2015.Search in Google Scholar

[15] Hlad B, Skoberne P. Pregled stanja biotske raznovrstnosti in krajinske pestrost v Sloveniji. In: Hlad B, Skoberne P, editor. Ministrstvo za okolje in prostro. Ljubljana: Agencija Republike Slovenije za okolje; 2001.Search in Google Scholar

[16] Čelik T. Population structure, migration and conservation of Coenonympha oedippus Fabricius, 1787 (Lepidoptera: Satyridae) in a fragmented landscape [PhD thesis]. Ljubljana: University of Ljubljana; 2003. (in Slovene).Search in Google Scholar

[17] Čelik T, Vreš B, Seliškar A. Determinants of within-patch microdistribution and movements of endangered butterfly Coenonympha oedippus (Fabricius, 1787) (Nymphalidae: Satyrinae). Hacquetia. 2009;8(2):115–28. 10.2478/v10028-009-0007-x.Search in Google Scholar

[18] Council Decision concerning the conclusion of the Convention on Biological Diversity. 93/626/EEC. Rio De Janeiro, Brazil, 1993.Search in Google Scholar

[19] Agenda 21: Programme of Action for Sustainable Development; Rio Declaration on Environment and Development; Statement of Forest Principles: The Final Text of Agreements Negotiated by Governments at the United Nations Conference On Environment and Devel. United Nations Dept. of Public Information, Rio De Janeiro, Brazil, 1993.Search in Google Scholar

[20] Uradni list RS št. 96/2004. Zakon o ohranjanju narave (uradno prečiščeno besedilo) (ZON-UPB2).Search in Google Scholar

[21] Stanners D, Bourdeau P. Europe’s environment: the Dobris assessment. CEC. European environment agency; 1995.Search in Google Scholar

[22] Lisec A, Pišek J, Drobne S. Suitability analysis of land use records of agricultural and forest land for detecting land use change on the case of the Pomurska Statistical Region. Acta Geogr Slov. 2013;53(1):71–90. 10.3986/AGS53104.Search in Google Scholar

[23] Gabrovec M, Kumer P. Land-use changes in Slovenia from the Franciscean Cadaster until today. Acta Geogr Slov. 2019;59(1):63–81. 10.3986/AGS.4892.Search in Google Scholar

[24] Ribeiro D, Burnet JE, Torkar G. Four windows on Borderlands: dimensions of place defined by land cover change data from historical maps. Acta Geogr Slov. 2013;53(2):317–42. 10.3986/AGS53204.Search in Google Scholar

[25] Gabrovec M, Kladnik D. Some new aspects of land use in Slovenia. Geogr Zb. 1997;37:8–64.Search in Google Scholar

[26] Perko D, Urbanc M. Landscape research in Slovenia. Belgeo. 2004;2–3:347–60. 10.4000/belgeo.13618.Search in Google Scholar

[27] Šmid Hribar M. In: Pogačnik A, editor. Varovanje in trajnostni razvoj kulturne pokrajine na primeru Ljubljanskega barja. Georitem 27. Ljubljana: Založba ZRC; 2016.10.3986/9789612549121Search in Google Scholar

[28] Vuorela N. Can data combination help to explain the existence of diverse landscapes? Fennia. 2000;178(1):55–80.Search in Google Scholar

[29] Ihse M. Swedish agricultural landscapes – patterns and changes during the last 50 years, studied by aerial photos. Landsc Urban Plan. 1995;31:21–37. 10.1016/0169-2046(94)01033-5.Search in Google Scholar

[30] Landsman AP, Ladin ZS, Gardner D, Bowman JL, Shriver G, D’Amico V, et al. Local landscapes and microhabitat characteristics are important determinants of urban–suburban forest bee communities. Ecosphere. 2019;10(10):1–15. 10.1002/ecs2.2908.Search in Google Scholar

[31] Jugovic J, Zupan S, Bužan E, Čelik T. Variation in the morphology of the wings of the endangered grass-feeding butterfly Coenonympha oedippus (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae) in response to contrasting habitats. Eur J Entomol. 2018;115:339–53. 10.14411/eje.2018.034.Search in Google Scholar

[32] Čelik T, Bräu M, Bonelli S, Cerrato C, Vreš B, Balletto E, et al. Winter-green host-plants, litter quantity and vegetation structure are key determinants of habitat quality for Coenonympha oedippus in Europe. J Insect Conserv. 2015;19(2):359–75. 10.1007/s10841-014-9736-3.Search in Google Scholar

[33] Zupan S, Jugovic J, Čelik T, Bužan E. An insight into genetic population structure of butterfly False Ringlet, Coenonympha oedippus (Nymphalidae, Satyrinae) from Slovenia. In: Future 4 butterflies Europe. Wageningen: Dutch Butterfly Conservation; 2016, p. 131.Search in Google Scholar

[34] Zupan S, Jugovic J, Čelik T, Bužan E. Possible links between molecular and morphological data in two ecotypes of False Ringlet, Coenonympha oedippus (Nymphalidae: Satyrinae) at the southern distribution limit. In: Fišer Pečnikar Ž, Lužnik M, Urzi F, editors. Book of abstracts. Koper: International Workshop Conservation Biology; 2015. p. 14.Search in Google Scholar

[35] Verovnik R, Čelik T, Grobelnik V, Šalamun A, Sečen T, Govedič M. Vzpostavitev monitoringa izbranih ciljnih vrst metuljev (Lepidoptera). Zaključno poročilo – III. mejnik. Ljubljana: Univerza v Ljubljani, Biotehniška fakulteta; 2009.Search in Google Scholar

[36] Verovnik R, Zakšek V, Govedič M, Zakšek B, Kogovšek N, Grobelnik V, et al. Vzpostavitev in izvajanje monitoringa izbranih ciljnih vrst metuljev v letih 2014 in 2015. Ljubljana: Univerza v ljubljani, Biotehniška fakulteta; 2015.Search in Google Scholar

[37] Čelik T, Verovnik R. Distribution, habitat preferences and population ecology of the False Ringlet Coenonympha oedippus (Fabricius, 1787) (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae) in Slovenia. Oedippus. 2010;7–15:26.Search in Google Scholar

[38] Habeler H. Study of the living space of Coenonympha oedippus F. (Lepidoptera, Satyridae). Nachrichtenblatt der Bayer Entomol. 1972;21:51–4.Search in Google Scholar

[39] Čelik T. Monitoring tarčnih vrst: Barjanski okarček (Coenonympha oedippus). Ljudje za Barje – ohranjanje biotske pestrosti na Ljubljanskem barju. Final report. Ljubljana: Biološki inštitut Jovana Hadžija ZRC SAZU; 2015.Search in Google Scholar

[40] Šašić M. False Ringlet Coenonympha oedippus (Fabricius, 1787) (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae) in Croatia: current status, population dynamics and conservation management. Oedippus. 2010;26:16–9.Search in Google Scholar

[41] GURS: Geodetska uprava Republike Slovenije [Surveying and Mapping Authority of the Republic of Slovenia], 2017.Search in Google Scholar

[42] ESRI, Redlands, CA. ArcGIS 10.4.1.Search in Google Scholar

[43] MKGP Javni pregledovalnik grafičnih podatkov: Ministrstvo za kmetijstvo, gozdarstvo in prehrano [Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Food], 1999.Search in Google Scholar

[44] KIS: Kmetijski inštitut Slovenije [The Agricultural Institute of Slovenia], 2014.Search in Google Scholar

[45] MKGP Javni pregledovalnik grafičnih podatkov: Ministrstvo za kmetijstvo, gozdarstvo in prehrano [Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Food], 2015.Search in Google Scholar

[46] Després L, Henniaux C, Rioux D, Capblancq T, Zupan S, Čelik T, et al. Inferring the biogeography and demographic history of an endangered butterfly in Europe from multilocus markers. Biol J Linn Soc. 2019;126(1):95–113. 10.1093/biolinnean/bly160.Search in Google Scholar

[47] Casacci LP, Cerrato C, Barbero F, Bosso L, Ghidotti S, Paveto M, et al. Dispersal and connectivity effects at different altitudes in the Euphydryas aurinia complex. J Insect Conserv. 2015;19(2):265–77. 10.1007/s10841-014-9715-8.Search in Google Scholar

[48] Bonato L, Uliana M, Beretta S. Farfalle del Veneto: Atlante Distributivo [Butterflies of Veneto: Distributional Atlas]. Fondazione Musei civici di Venezia, Venezia, Regione Veneto, 2014.Search in Google Scholar

[49] Čelik T, Verovnik R, Rebeušek F, Gomboc S, Lasan M. Strokovna izhodišča za vzpostavljanje omrežja Natura 2000: metulji (Lepidoptera): končno poročilo – 2. mejnik. Ljubljana, 2004.10.3986/9789612545116Search in Google Scholar

[50] Čelik T, Verovnik R, Gomboc S, Lasan M. Natura 2000 v Sloveniji, Metulji, = Lepidoptera. Ljubljana: ZRC SAZU; 2005.10.3986/9789612545116Search in Google Scholar

[51] Čelik T, Rebeušek F. Atlas ogroženih vrst dnevnih metuljev Slovenije. Ljubljana: Slovensko entomološko društvo Štefana Michielija; 1996.Search in Google Scholar

[52] Ogrin D. Geografija stika Slovenske Istre in Tržaškega zaliva. Ljubljana: Znanstvena založba Filozofske fakultete; 2012.Search in Google Scholar

[53] Repe B. Voda v prsti in ugotavljanje njenega razporejanja v odvisnosti od reliefa. Dela. 2007;28:91–106.10.4312/dela.28.91-106Search in Google Scholar

[54] Repe B. Soils of Slovenia. In: Orožen Adamič M, editor. Slovenia: a geographical overview. Ljubljana: ZRC Publishing; 2004.Search in Google Scholar

[55] Stillwell RC, Blanckenhorn WU, Teder T, Davidowitz G, Fox CW. Sex differences in phenotypic plasticity affect variation in sexual size dimorphism in insects: from physiology to evolution. Annu Rev Entomol. 2010;55(1):227–45. 10.1016/j.physbeh.2017.03.040.Search in Google Scholar

[56] Hirst AG, Horne CR, Atkinson D. Equal temperature – size responses of the sexes are widespread within arthropod species. Proc R Soc B1–9. 1820;2015:282.10.1098/rspb.2015.2475Search in Google Scholar

[57] Goebel MO, Bachmann J, Reichstein M, Janssens IA, Guggenberger G. Soil water repellency and its implications for organic matter decomposition – is there a link to extreme climatic events? Glob Chang Biol. 2011;17(8):2640–56. 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2011.02414.x.Search in Google Scholar

[58] Doerr SH, Shakesby RA, Walsh RPD. Soil water repellency: its causes, characteristics and hydro-geomorphological significance. Earth Sci Rev. 2000;51(1–4):33–65. 10.1016/S0012-8252(00)00011-8.Search in Google Scholar

[59] Dekker L, Ritsema C. How water moves in a water repellent sandy soil.1. Potential and actual water repellency. Water Resour Res. 1994;30(9):2507–17. 10.1029/94WR00749.Search in Google Scholar

[60] Franco C, Clarke P, Tate M, Oades J. Hydrophobic properties and chemical characterisation of natural water repellent materials in Australian sands. J Hydrol. 2000;231:47–58. 10.1016/S0022-1694(00)00182-7.Search in Google Scholar

[61] Petek F. Land use in Slovenia. In: Orožen Adamic M, editor. Slovenia: a geographical overview. Ljubljana: ZRC Publishing; 2004.Search in Google Scholar

[62] Levers C, Butsic V, Verburg P, Müller D, Kuemmerle T. Drivers of changes in agricultural intensity in Europe. Land Use Policy. 2016;58:380–93. 10.1016/j.landusepol.2016.08.013.Search in Google Scholar

© 2020 Sara Zupan et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- The simulation approach to the interpretation of archival aerial photographs

- The application of137Cs and210Pbexmethods in soil erosion research of Titel loess plateau, Vojvodina, Northern Serbia

- Provenance and tectonic significance of the Zhongwunongshan Group from the Zhongwunongshan Structural Belt in China: insights from zircon geochronology

- Analysis, Assessment and Early Warning of Mudflow Disasters along the Shigatse Section of the China–Nepal Highway

- Sedimentary succession and recognition marks of lacustrine gravel beach-bars, a case study from the Qinghai Lake, China

- Predicting small water courses’ physico-chemical status from watershed characteristics with two multivariate statistical methods

- An Overview of the Carbonatites from the Indian Subcontinent

- A new statistical approach to the geochemical systematics of Italian alkaline igneous rocks

- The significance of karst areas in European national parks and geoparks

- Geochronology, trace elements and Hf isotopic geochemistry of zircons from Swat orthogneisses, Northern Pakistan

- Regional-scale drought monitor using synthesized index based on remote sensing in northeast China

- Application of combined electrical resistivity tomography and seismic reflection method to explore hidden active faults in Pingwu, Sichuan, China

- Impact of interpolation techniques on the accuracy of large-scale digital elevation model

- Natural and human-induced factors controlling the phreatic groundwater geochemistry of the Longgang River basin, South China

- Land use/land cover assessment as related to soil and irrigation water salinity over an oasis in arid environment

- Effect of tillage, slope, and rainfall on soil surface microtopography quantified by geostatistical and fractal indices during sheet erosion

- Validation of the number of tie vectors in post-processing using the method of frequency in a centric cube

- An integrated petrophysical-based wedge modeling and thin bed AVO analysis for improved reservoir characterization of Zhujiang Formation, Huizhou sub-basin, China: A case study

- A grain size auto-classification of Baikouquan Formation, Mahu Depression, Junggar Basin, China

- Dynamics of mid-channel bars in the Middle Vistula River in response to ferry crossing abutment construction

- Estimation of permeability and saturation based on imaginary component of complex resistivity spectra: A laboratory study

- Distribution characteristics of typical geological relics in the Western Sichuan Plateau

- Inconsistency distribution patterns of different remote sensing land-cover data from the perspective of ecological zoning

- A new methodological approach (QEMSCAN®) in the mineralogical study of Polish loess: Guidelines for further research

- Displacement and deformation study of engineering structures with the use of modern laser technologies

- Virtual resolution enhancement: A new enhancement tool for seismic data

- Aeromagnetic mapping of fault architecture along Lagos–Ore axis, southwestern Nigeria

- Deformation and failure mechanism of full seam chamber with extra-large section and its control technology

- Plastic failure zone characteristics and stability control technology of roadway in the fault area under non-uniformly high geostress: A case study from Yuandian Coal Mine in Northern Anhui Province, China

- Comparison of swarm intelligence algorithms for optimized band selection of hyperspectral remote sensing image

- Soil carbon stock and nutrient characteristics of Senna siamea grove in the semi-deciduous forest zone of Ghana

- Carbonatites from the Southern Brazilian platform: I

- Seismicity, focal mechanism, and stress tensor analysis of the Simav region, western Turkey

- Application of simulated annealing algorithm for 3D coordinate transformation problem solution

- Application of the terrestrial laser scanner in the monitoring of earth structures

- The Cretaceous igneous rocks in southeastern Guangxi and their implication for tectonic environment in southwestern South China Block

- Pore-scale gas–water flow in rock: Visualization experiment and simulation

- Assessment of surface parameters of VDW foundation piles using geodetic measurement techniques

- Spatial distribution and risk assessment of toxic metals in agricultural soils from endemic nasopharyngeal carcinoma region in South China

- An ABC-optimized fuzzy ELECTRE approach for assessing petroleum potential at the petroleum system level

- Microscopic mechanism of sandstone hydration in Yungang Grottoes, China

- Importance of traditional landscapes in Slovenia for conservation of endangered butterfly

- Landscape pattern and economic factors’ effect on prediction accuracy of cellular automata-Markov chain model on county scale

- The influence of river training on the location of erosion and accumulation zones (Kłodzko County, South West Poland)

- Multi-temporal survey of diaphragm wall with terrestrial laser scanning method

- Functionality and reliability of horizontal control net (Poland)

- Strata behavior and control strategy of backfilling collaborate with caving fully-mechanized mining

- The use of classical methods and neural networks in deformation studies of hydrotechnical objects

- Ice-crevasse sedimentation in the eastern part of the Głubczyce Plateau (S Poland) during the final stage of the Drenthian Glaciation

- Structure of end moraines and dynamics of the recession phase of the Warta Stadial ice sheet, Kłodawa Upland, Central Poland

- Mineralogy, mineral chemistry and thermobarometry of post-mineralization dykes of the Sungun Cu–Mo porphyry deposit (Northwest Iran)

- Main problems of the research on the Palaeolithic of Halych-Dnister region (Ukraine)

- Application of isometric transformation and robust estimation to compare the measurement results of steel pipe spools

- Hybrid machine learning hydrological model for flood forecast purpose

- Rainfall thresholds of shallow landslides in Wuyuan County of Jiangxi Province, China

- Dynamic simulation for the process of mining subsidence based on cellular automata model

- Developing large-scale international ecological networks based on least-cost path analysis – a case study of Altai mountains

- Seismic characteristics of polygonal fault systems in the Great South Basin, New Zealand

- New approach of clustering of late Pleni-Weichselian loess deposits (L1LL1) in Poland

- Implementation of virtual reference points in registering scanning images of tall structures

- Constraints of nonseismic geophysical data on the deep geological structure of the Benxi iron-ore district, Liaoning, China

- Mechanical analysis of basic roof fracture mechanism and feature in coal mining with partial gangue backfilling

- The violent ground motion before the Jiuzhaigou earthquake Ms7.0

- Landslide site delineation from geometric signatures derived with the Hilbert–Huang transform for cases in Southern Taiwan

- Hydrological process simulation in Manas River Basin using CMADS

- LA-ICP-MS U–Pb ages of detrital zircons from Middle Jurassic sedimentary rocks in southwestern Fujian: Sedimentary provenance and its geological significance

- Analysis of pore throat characteristics of tight sandstone reservoirs

- Effects of igneous intrusions on source rock in the early diagenetic stage: A case study on Beipiao Formation in Jinyang Basin, Northeast China

- Applying floodplain geomorphology to flood management (The Lower Vistula River upstream from Plock, Poland)

- Effect of photogrammetric RPAS flight parameters on plani-altimetric accuracy of DTM

- Morphodynamic conditions of heavy metal concentration in deposits of the Vistula River valley near Kępa Gostecka (central Poland)

- Accuracy and functional assessment of an original low-cost fibre-based inclinometer designed for structural monitoring

- The impacts of diagenetic facies on reservoir quality in tight sandstones

- Application of electrical resistivity imaging to detection of hidden geological structures in a single roadway

- Comparison between electrical resistivity tomography and tunnel seismic prediction 303 methods for detecting the water zone ahead of the tunnel face: A case study

- The genesis model of carbonate cementation in the tight oil reservoir: A case of Chang 6 oil layers of the Upper Triassic Yanchang Formation in the western Jiyuan area, Ordos Basin, China

- Disintegration characteristics in granite residual soil and their relationship with the collapsing gully in South China

- Analysis of surface deformation and driving forces in Lanzhou

- Geochemical characteristics of produced water from coalbed methane wells and its influence on productivity in Laochang Coalfield, China

- A combination of genetic inversion and seismic frequency attributes to delineate reservoir targets in offshore northern Orange Basin, South Africa

- Explore the application of high-resolution nighttime light remote sensing images in nighttime marine ship detection: A case study of LJ1-01 data

- DTM-based analysis of the spatial distribution of topolineaments

- Spatiotemporal variation and climatic response of water level of major lakes in China, Mongolia, and Russia

- The Cretaceous stratigraphy, Songliao Basin, Northeast China: Constrains from drillings and geophysics

- Canal of St. Bartholomew in Seča/Sezza: Social construction of the seascape

- A modelling resin material and its application in rock-failure study: Samples with two 3D internal fracture surfaces

- Utilization of marble piece wastes as base materials

- Slope stability evaluation using backpropagation neural networks and multivariate adaptive regression splines

- Rigidity of “Warsaw clay” from the Poznań Formation determined by in situ tests

- Numerical simulation for the effects of waves and grain size on deltaic processes and morphologies

- Impact of tourism activities on water pollution in the West Lake Basin (Hangzhou, China)

- Fracture characteristics from outcrops and its meaning to gas accumulation in the Jiyuan Basin, Henan Province, China

- Impact evaluation and driving type identification of human factors on rural human settlement environment: Taking Gansu Province, China as an example

- Identification of the spatial distributions, pollution levels, sources, and health risk of heavy metals in surface dusts from Korla, NW China

- Petrography and geochemistry of clastic sedimentary rocks as evidence for the provenance of the Jurassic stratum in the Daqingshan area

- Super-resolution reconstruction of a digital elevation model based on a deep residual network

- Seismic prediction of lithofacies heterogeneity in paleogene hetaoyuan shale play, Biyang depression, China

- Cultural landscape of the Gorica Hills in the nineteenth century: Franciscean land cadastre reports as the source for clarification of the classification of cultivable land types

- Analysis and prediction of LUCC change in Huang-Huai-Hai river basin

- Hydrochemical differences between river water and groundwater in Suzhou, Northern Anhui Province, China

- The relationship between heat flow and seismicity in global tectonically active zones

- Modeling of Landslide susceptibility in a part of Abay Basin, northwestern Ethiopia

- M-GAM method in function of tourism potential assessment: Case study of the Sokobanja basin in eastern Serbia

- Dehydration and stabilization of unconsolidated laminated lake sediments using gypsum for the preparation of thin sections

- Agriculture and land use in the North of Russia: Case study of Karelia and Yakutia

- Textural characteristics, mode of transportation and depositional environment of the Cretaceous sandstone in the Bredasdorp Basin, off the south coast of South Africa: Evidence from grain size analysis

- One-dimensional constrained inversion study of TEM and application in coal goafs’ detection

- The spatial distribution of retail outlets in Urumqi: The application of points of interest

- Aptian–Albian deposits of the Ait Ourir basin (High Atlas, Morocco): New additional data on their paleoenvironment, sedimentology, and palaeogeography

- Traditional agricultural landscapes in Uskopaljska valley (Bosnia and Herzegovina)

- A detection method for reservoir waterbodies vector data based on EGADS

- Modelling and mapping of the COVID-19 trajectory and pandemic paths at global scale: A geographer’s perspective

- Effect of organic maturity on shale gas genesis and pores development: A case study on marine shale in the upper Yangtze region, South China

- Gravel roundness quantitative analysis for sedimentary microfacies of fan delta deposition, Baikouquan Formation, Mahu Depression, Northwestern China

- Features of terraces and the incision rate along the lower reaches of the Yarlung Zangbo River east of Namche Barwa: Constraints on tectonic uplift

- Application of laser scanning technology for structure gauge measurement

- Calibration of the depth invariant algorithm to monitor the tidal action of Rabigh City at the Red Sea Coast, Saudi Arabia

- Evolution of the Bystrzyca River valley during Middle Pleistocene Interglacial (Sudetic Foreland, south-western Poland)

- A 3D numerical analysis of the compaction effects on the behavior of panel-type MSE walls

- Landscape dynamics at borderlands: analysing land use changes from Southern Slovenia

- Effects of oil viscosity on waterflooding: A case study of high water-cut sandstone oilfield in Kazakhstan

- Special Issue: Alkaline-Carbonatitic magmatism