Abstract

Background and aims

Despite the recognition of pain as a global health problem and advancements achieved in what is known about effective pain management, pain education for undergraduate health care professionals remains insufficient. This study investigated the content of pain curricula and the time allocated to pain education on physiotherapy programs at bachelor’s level at Universities of Applied Sciences (UASs) in Finland.

Methods

A web-based survey questionnaire was sent to the directors of the physiotherapy programs at all the Finnish UASs (n=15) where physiotherapy is taught at bachelor’s level. The questionnaire consisted of 14 questions covering basic concepts and the science of pain, pain assessment, pain management, and the adequacy of pain curricula. Each UAS completed one questionnaire i.e. returned one official opinion.

Results

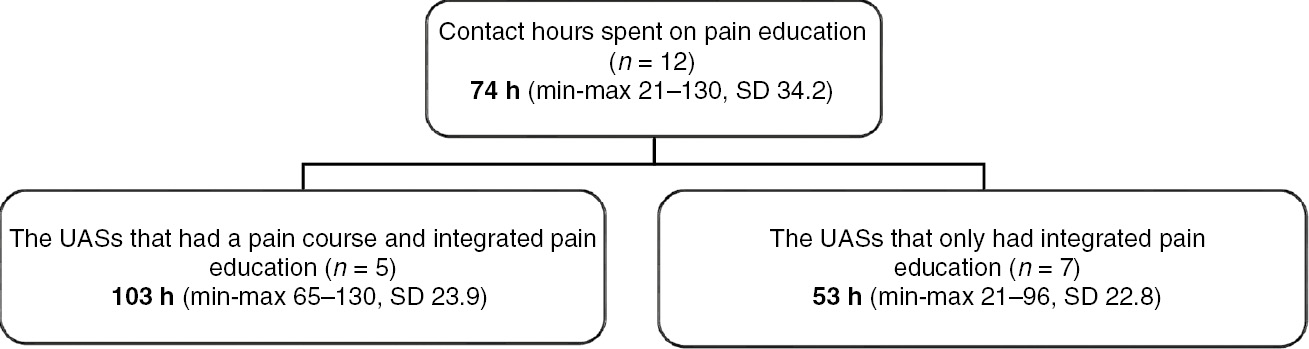

The response rate was 80% (n=12). The mean for the total number of contact hours of pain education was 74 (standard deviation 34.2). All UASs had integrated pain education. In addition to this 42% (n=5) of the UASs had a separate pain course. The UASs offering such a course over and above the integrated pain education had twice the amount of pain content education compared to those UASs that only had integrated pain education (mean 103 h vs. 53 h, p=0.0043). Most of the education was devoted to conditions where pain is commonly a feature, manual therapy, and electrical agents for pain control. The biopsychosocial model of pain, cognitive behavioral methods of pain management, physician management, and multidisciplinary management were the least covered topics. Five UASs (42%) payed attention to the International Association for the Study of Pain curriculum outline and only 33% (n=4) considered their pain education to be sufficient.

Conclusions

Our results indicate that more contact hours are devoted to pain education on the Finnish UASs’ physiotherapy programs at bachelor’s level, than has previously been reported in faculty surveys. A separate pain course is one way to ensure a sufficient amount of pain education. Overall, despite a sufficient time devoted to pain education, some essential pain contents were inadequately covered.

Implications

The study contributes information on how pain education can be organized on physiotherapy programs at undergraduate level. Besides a sufficient amount of pain education, which can be ensured by a separate pain course, attention should be paid to pain education content being up-to-date. This could help in estimating the different proportions of pain content needed in educational settings. Efforts should also be made at keeping integrated pain education well-coordinated and purposeful. There is a need for further research estimating the effectiveness of pain education according to the different ways in which it is organized. There is also a need to investigate whether more hours allocated to pain education results in better understanding and professional skills.

1 Introduction

In 2010 the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) declared that “there are major deficits in knowledge of health care professionals regarding the mechanisms and management of pain” [1]. In the meantime pain science research, e.g. on chronic pain, has increased considerably with significant advances in the understanding of its etiology, assessment, and treatment [2], [3], [4]. Information about pain mechanisms and clinical guidance for health care professionals caring for people with pain is constantly being updated due to large amounts of published laboratory-based and clinically-based research [5]. To meet the needs of educators seeking to develop their pain curricula the IASP has since 1994 published pain curriculum outlines to support the education of physiotherapist [5] and of other health care professionals at the undergraduate and graduate levels [6]. These curriculum outlines are built around the domains of the multidimensional nature of pain, pain assessment and measurement, the management of pain, and clinical conditions [6]. The curricula outlines were last updated at the end of 2017 for the IASP 2018 Global Year for Excellence in Pain Education [6], [7].

In recent years the content of pain curricula and the time allocated to pain education on various healthcare undergraduate programs, including physiotherapy, has been studied at least in Canada [8], the UK [9], and Norway [10]. These studies show a clear difficulty in ascertaining the amount of time allocated to mandatory pain content [8], [10], great differences in how the institutions organize their pain curricula [9], [10], minimal amount of interprofessional learning, and the fact that the hours of pain education are woefully inadequate given the prevalence and burden of pain [9]. Research that specifically evaluates pain curricula on undergraduate physiotherapy programs has been conducted in North America with an average of 4 h [11] and in the US with a mean of 31 h [12] spent on pain education. The majority [11] and, respectively 61% [12] of respondents estimated that pain was adequately covered. It has been suggested that most physiotherapy education programs still do not directly address pain science, but rather teach management of problems from a biomechanical approach to a specific body region [13].

The prevalence of employees’ working days lost due to pain is high in Finland [14]. The incapacity to work due to chronic pain causes considerable costs to society; in Finland in 2013 the costs of sick pay and disability pensions due to back illnesses alone amounted to 469 million Euros. The related loss in terms of production input was manifold [15]. Consequently, it is important for pain management methods to follow the best available evidence. However, our knowledge of the current state of pain education among health care students in Finland is limited. We therefore conducted a study to describe the content of pain curricula and the time allocated to pain education on physiotherapy programs at bachelor’s level at the Finnish Universities of Applied Sciences (UASs).

2 Methods

2.1 Subjects

The subjects comprised all the UASs in Finland where physiotherapy is taught at bachelor’s level (n=15). The bachelor’s degree in physiotherapy, carrying 210 ECTS (European Credit Transfer and Accumulation System) consists of 3.5–4 years of full-time study. A list of the UASs was obtained from the website of the Finnish Association of Physiotherapists (FAP) in April 2017.

The first author (JE) informed the directors of the physiotherapy programs about the study by telephone. Thereafter an information letter about the survey and a PDF (Portable Document Format) version of the questionnaire was sent to these directors in October 2017, along with an electronic link to answer the questionnaire. While each UAS completed only one questionnaire, thereby returning an official opinion, we advised the respondents to consult physiotherapy teachers if needed before answering the questionnaire. The initial electronic link to the questionnaire had a 3-week deadline. One e-mail reminder was sent 3 days before the deadline. Finally the first author (JE) contacted non-respondents by telephone.

2.2 Questionnaire

Our questionnaire was an adapted and modified version of the questionnaire developed by Hoeger Bement and Sluka [12]. The original questionnaire has its origins in methods, topics, and questions of surveys developed by Mezei et al. [16] and Murinson et al. [17] addressing the pain curriculum of medical students. Hoeger Bement and Sluka’s [12] criteria for the development of their survey was based on consultation with pain experts, completion of preliminary testing, and incorporation of the IASP pain curriculum guidelines. Hoeger Bement and Sluka [12] designed their survey around IASP guidelines and divided their questions according to general principles of pain and pain science, assessment of pain, and management of pain. Permission to use an adapted version of the original questionnaire was obtained from the corresponding author of the instrument, Professor Sluka, in May 2017. The questionnaire was piloted at one UAS by two physiotherapy teachers not involved in bachelor’s level physiotherapy education.

Our version of the questionnaire consisted of 14 questions: 12 structured and two semi-structured. The questionnaire included questions on the basic concepts and science of pain, pain assessment, pain management, and the adequacy of the pain curriculum. With respect to these topics four main changes were made to our version of the questionnaire compared to the original one. The first change was that when considering the amount of pain education according to its organization, the combination of integrated pain education and a pain course was taken into account. A “Pain course” (pain mechanisms/management course) referred to an independent compulsory pain course during which the focus was on pain and its mechanisms and management. “Integrated pain education” (integrated pain mechanisms/management education) referred to pain mechanisms/management education that was integrated into the traditional courses on the curriculum, such as anatomy, musculoskeletal physiotherapy or manual therapy. Secondly, minor changes were made to a few sub-questions eliciting the number of contact hours according to pain education content. When a UAS reported over 10 contact hours of some specific pain education content the time was estimated to being 11 h, and this estimate was used in the statistical calculations. Thirdly, two regional questions specific to the US were adapted to match conditions in Finland. Fourthly, two new semi-structured questions were introduced. These questions concerned teaching methods and the average numbers of students in teaching classes, and challenges and suggestions for improvement to the faculty’s pain curriculum.

2.3 Ethical approval

This study was granted ethical approval by The Research Ethics Board of Åbo Akademi University, Vaasa, Finland, in August 2017. Research permission was received from the UASs in October 2017.

2.4 Data analysis

The statistical analysis was done with Statistical Package for the Social Sciences 24.0 (Norusis/SPSS, Inc., Chicago IL, USA). Descriptive statistics were used to determine the proportion of hours dedicated to pain education, the number of teaching hours dedicated to various pain-related content areas, as well as to determine the structure and content of pain education. Comparisons in terms of contact hours between the UASs having a pain course and integrated pain education vs. the UASs only having integrated pain education were performed with t-test. Results are given as differences in means and their 95% confidence Intervals (CI). p<0.05 (two-tailed) was accepted as a statistically significant threshold. The two semi-structured questions were analyzed inductively using thematic analysis.

3 Results

The response rate was 80% (n=12). The first author (JE) contacted three UASs to clarify some contradictory answers to two of the questions: a pain course and integrated pain education. Thirty-three percent (n=4) of the questionnaires were answered in consensus by two persons, 25% by one person (n=3), 25% by three persons, and 17% (n=2) by five persons. The respondents varied from physiotherapy teachers to physiotherapy program directors.

3.1 Amount of pain education

All the UASs had integrated pain education, mainly in the second and third years of study. In addition to the integrated pain education 42% (n=5) of the UASs reported having a pain course. The average number of contact hours on such a course was 50 (min-max 40–60) and the course was held in the second year of studies. Two UASs reported intending to add a separate pain course in the academic year 2018–2019. The mean for the total number of contact hours of pain education was 74 [min-max 21–130, standard deviation (SD) 34.2]. The UASs that had a pain course over and above the integrated pain education had twice the amount of pain education compared those UASs that only had integrated pain education (mean 103 h, SD 23.9 vs. mean 53 h, SD 22.8; p=0.0043), see Fig. 1.

Mean numbers of contact hours spent on pain education.

3.2 Content of pain education

According to the contact hours allocated to the various categories of pain education most of the time was spent on pain interventions and management, followed by pain science, and least hours was spent on pain assessment (Table 1). Within these categories most of the time was spent on the following topics: conditions where pain is commonly a feature, manual therapy, and electrical agents for pain control. The biopsychosocial model of pain, cognitive behavioral methods of pain management, physician management, and multidisciplinary (interdisciplinary) management were the least covered topics (Table 1).

Average contact hours allocated to pain categories (pain science, pain assessment and pain intervention and management).

| Content | Mean | Min-max |

|---|---|---|

| Pain science (SD 12.6) | 26 | 8–48 |

| The science of underlying pain and analgesia | 5.6 | 2–11 |

| Differences between acute and chronic pain | 4.8 | 1–11 |

| The multidimensional nature of the pain experience | 4.7 | 1–11 |

| The biopsychosocial model of pain | 2.8 | 0–6 |

| Conditions where pain is commonly a feature | 8.1 | 1–11 |

| Pain assessment (SD 3.5) | 6.1 | 1–11 |

| Pain intervention and management (SD 21.3) | 41.7 | 9–71 |

| Education and self-management strategies | 5.3 | 1–11 |

| Cognitive behavioral methods of pain management | 2.7 | 0–11 |

| Exercise therapy for pain control | 6.5 | 2–11 |

| Manual therapy for pain control (massage and mobilization) | 8.8 | 1–11 |

| Electrical agents for pain control (TENS and IFC) | 8.7 | 2–11 |

| Thermal agents for pain control | 4.6 | 1–10 |

| Physician management | 2.8 | 0–11 |

| Multidisciplinary (interdisciplinary) management | 2.4 | 0–6 |

-

SD=standard deviation; TENS=transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation; IFC=interferential current.

3.3 Amount and content of pain education according to its organization

The five UASs that reported having a pain course in combination with integrated pain education allocated more contact hours to almost all types of content compared to the seven UASs that only had integrated pain education (Table 2). The difference in the numbers of contact hours was especially high for the science of underlying pain and analgesia, differences between acute and chronic pain, the multidimensional nature of the pain experience, conditions where pain is commonly a feature, education and self-management strategies for the pain patient, exercise therapy for pain control, and physician management of the pain patient (Table 2).

Numbers of contact hours spent on different pain content in accordance with the organization of the pain education.

| Content of pain education | Pain course and integrated pain education (n=5) mean (SD) | Integrated pain education (n=7) mean (SD) | Difference (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pain science | |||

| The science of underlying pain and analgesia | 8.8 (2.2) | 3.3 (1.3) | 5.5 (3.3–7.7)a |

| Differences between acute and chronic pain | 8.4 (3.2) | 2.3 (1.0) | 6.1 (3.3–8.9)a |

| The multidimensional nature of the pain experience | 7.0 (3.1) | 3.0 (1.3) | 4.0 (1.1–6.9)a |

| The biopsychosocial model of pain | 3.6 (1.8) | 2.3 (2.4) | 1.3 (−1.5–4.1) |

| Conditions where pain is commonly a feature | 10.6 (0.9) | 6.3 (3.9) | 4.3 (0.3–8.3)a |

| Pain assessement | 8.2 (2.7) | 4.6 (3.3) | 3.6 (−0.4–7.6) |

| Pain intervention and management | |||

| Education and self-management strategies for the pain patient | 8.4 (3.7) | 3.1 (3.6) | 5.3 (0.6–10.0)a |

| Cognitive behavioral methods of pain management | 2.2 (1.8) | 3.0 (4.1) | −0.8 (−3.6–5.2) |

| Exercise therapy for pain control | 9.4 (3.6) | 4.4 (3.3) | 5.0 (0.5–9.5)a |

| Manual therapy (massage, mobilization) for pain control | 11 (0.0) | 7.1 (4.8) | 3.9 (−1.0–8.8) |

| Electrical agents for pain control (TENS, IFC) | 10.4 (1.3) | 7.4 (3.2) | 3.9 (−0.4–6.4) |

| Thermal agents for pain control | 6.6 (2.6) | 3.1 (2.2) | 3.5 (0.4–6.6)a |

| Physician management of the pain patient | 5.4 (5.1) | 0.9 (1.6) | 4.5 (−0.0–9.0) |

| Multidisciplinary (interdisciplinary) management of the pain patient | 3.2 (2.2) | 1.9 (1.6) | 1.3 (−1.1–3.7) |

-

SD=standard deviation; CI=confidence interval; TENS=transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation; IFC=interferential current. ap<0.05.

3.4 Specific content of pain education

Concerning the anatomy and physiology of pain all the UASs addressed the gate control theory of pain, pain pathways, nociceptive pain, peripheral neurogenic and neuropathic pain, and central sensitization. Neurotransmitters and receptors specific to pain was covered in 11 (92%) UASs and central inhibition in 10 (83%) UASs. When it comes to pain assessment all the UASs addressed subjective pain intensity (the numerical rating scale or visual analog scales [18]), disease-specific questionnaires (the Oswestry disability index [19] or the fibromyalgia impact questionnaire [20]), and functional measures (the 6-min walk test [21] or the functional reach test [22]). Psychosocial questionnaires (e.g. fear avoidance [23]) were covered in 11 (92%) UASs, assessment across the life span (pediatrics to geriatrics) in nine (75%) UASs, whereas pain-specific questionnaires (the Brief Pain Inventory [24] or the Örebro Musculoskeletal Pain Questionnaire, the ÖMPSQ [25]) in eight (67%) UASs.

Ten (83%) UASs stated that their pain teaching was evidence-based using best up-to-date information. Five (42%) UASs applied the report “National Action Plan for Treatment of Chronic Pain and Cancer Pain for 2017–2020” published by the Ministry of Social Affairs and Health in Finland [15] and five (42%) UASs applied the IASP Curriculum Outline on Pain for Physical Therapy [26], [27]. Only one UAS applied both the national report and the IASP’s pain curriculum, whereas three UASs reported not paying attention to either one. Of the respondents, three UASs (25%) had a teacher who was a member of the Finnish Association for the Study of Pain and in one UAS (8%) a teacher had completed the Finnish pain education “Pain education for physiotherapists” (15 ECTS) organized by the Finnish Association of Physiotherapists. Other pain related education that the UASs teachers had completed were neurodynamic courses, “explain pain” courses, multidisciplinary pain education, international pain courses, and some had written doctoral theses on pain. Even though the majority of the UASs used a variety of resources for pain education, the most commonly used literature was a Finnish book about pain entitled “Kipu” (n=11, 92%) and Butler’s and Moseley’s “Explain Pain” books (n=10, 83%). As teaching methods the majority of UASs reported using a combination of lecture, patient case studies, problem-based learning, and e-learning. Other teaching methods were blended learning, flipped classroom, group work, and independent study. The number of students in the UASs’ teaching classes varied from 20 to 50, with a mean of 31 students.

Only four UASs (33%) believed that their students received an adequate amount of pain education. The remaining eight UASs considered their pain education to be insufficient concerning: amount of education, not fitting the curriculum, not linked well enough throughout the different courses, different approaches to pain management, the psychological dimension of pain, the diversity of pain, and students understanding of what pain is.

3.5 Challenges and suggestions for improvement of pain education

Challenges in providing pain education reported by the UASs included reduction or lack of resources, the limits of ECTS credits, insufficiency of contact hours, inflexibility of the curriculum, fragmentary pain education, maintaining coherence throughout integrated pain education, further education of teachers, and being up-to-date on pain as a subject. Suggestions for improvements in pain education included making pain education a conscious theme throughout the curriculum, reflecting on the meaning of pain in all the different sectors of physiotherapy and expanding the multiprofessional nature of pain as a theme to other sectors of social and health care. One UAS proposed the establishment of national guidelines/recommendations for pain education to be based on the vision of the European Network of Physiotherapy in Higher Education (ENPHE).

4 Discussion

4.1 Main findings

Our study reports a higher mean value for time spent on pain education on the Finnish UASs’ physiotherapy programs at bachelor’s level than has previously been reported elsewhere. All the UASs had integrated pain education and in addition, close to half of them offered a separate pain course resulting in twice the amount of pain content education compared to those UASs that only had integrated pain education. Most time in the UAS’s education was spent on conditions where pain is commonly a feature, manual therapy, and electrical agents for pain control. By contrast the biopsychosocial model of pain, cognitive behavioral methods of pain management, physician management, and multidisciplinary management were the least covered topics. Close to half of the UASs payed attention to the IASP Curriculum Outline on Pain for Physical Therapy and only one third of the UASs considered their pain education to be sufficient.

4.2 Amount of pain education and its organization

In physiotherapy faculty surveys average time spent on pain education vary between a modal of 4 h and a median of 45 h [8], [9], [10], [11], [12], compared to the mean of 74 h in our study. The number of Finnish UASs having a separate pain course was also higher than previously reported in North America [11] and in the US [12]. This may indicate an awareness of the importance of pain as an educational topic. However, it may be difficult to accurately estimate the amount of pain education integrated across the curriculum [8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [28]. To the best of our knowledge the only suggestion on the quantity of undergraduate pain education is Pöyhiä and Kalso’s [29] estimate of a minimum of 74 h for the IASP medical curriculum. Even though the UASs mean value covers this amount, there is still wide variation in numbers of contact hours between the different UASs. This concurs with earlier research [8], [9], [10], [12]. It is not currently known whether more education results in better understanding and professional skills [30]. The clearly positive outcomes of a specific additional pain education session/course for physiotherapy students have though been increasingly reported [31], [32], [33], [34]. The IASP Curriculum Outline on Pain for Physical Therapy [26] states that the specific pain content can be integrated into programs, but the recommendation is that “the curriculum should be taught as a discrete unit, with content and competencies horizontally and vertically aligned to other units of study”. Our study confirms that an independent pain course over and above integrated pain education enables a considerable increase in the amount of pain education. In meantime the importance of well-coordinated and purposeful integrated pain education is acknowledged, and this has also previously been described as a factor of successful pain education [28].

4.3 The content of pain education

The fewest contact hours were devoted to the biopsychosocial model of pain, cognitive behavioral methods of pain management, physician management, and multidisciplinary (interdisciplinary) management. No earlier pain curriculum surveys [8], [9], [10], [11], [12] have estimated contact hours for the biopsychosocial model of pain. As for cognitive behavioral methods Scudds et al. [11] concluded that 33% of the respondents thought that cognitive behavioral approaches were adequately covered. Concerning multidisciplinary management Hoeger Bement and Sluka [12] reported a mean of 2.3 h, which equals the mean in our study (2.4 h). Watt-Watson et al. [8] and Leegaard et al. [10] reported clearly higher numbers, an average of 11 h and a median of 10 h. As for the biopsychosocial model of pain, cognitive behavioral methods of pain management, and multidisciplinary pain management these are all concepts which take into account the fact that pain is a multidimensional phenomenon. Seen as multidimensional, pain is clearly also an emergent phenomenon [35], [36] rather than a linear phenomenon. In the scientific literature there is evidence of students having difficulties in understanding the unpredictable and unexpected patterns of an emergent phenomenon (e.g. diffusion or natural selection), in contrast to patterns of linear or sequential phenomena [35], [37]. In addition, biopsychosocial model, cognitive behavioral methods, and multidisciplinary management are considered essential approaches to the current care of the chronic pain patient [38], [39], [40], [41]. When combining this information with the IASP pain curricula, in which the biopsychosocial model has high priority [26], [27] there is a clear discrepancy in the content of the UASs’ pain education. It is noteworthy that two thirds of the UASs considered their pain education to be insufficient concerning different approaches to pain management, the psychological dimension of pain, and the diversity of pain. These challenges are recognized in earlier research [28].

4.4 The IASP pain curriculum

The IASP Curriculum Outline on Pain for Physical Therapy [26] is an internationally recognized recommendation for undergraduate physiotherapy pain curricula that is updated on a regular basis. In 2017 the IASP reoriented the curricula towards competency-based education [13], [26], [42]. Research evidence of the successful implementation of the IASP pain curriculum is increasing, with significant changes demonstrated in physiotherapy students’ knowledge, beliefs and clinical competencies regarding pain [31], [43], [44], [45], [46]. The longest experience is that of Canada, where a 20-h IASP-based interfaculty pain curriculum has been implemented since 2002 [43], [44], [46]. The Canadian experiences have led to the development of The Pain Interprofessional Curriculum Design (PICD) Model [46]. In our study, 42% of the UASs applied the IASP curriculum. These findings can be compared to those of Briggs et al. [9] according to whom the IASP curricula had been fully implemented by one (1/9) physiotherapy program (40 h content) and Hoeger Bement and Sluka [12], who concluded that 46% of the respondents were aware of the IASP curricula. Hush et al. who recently implemented the IASP curriculum in Australia state that it provides a comprehensive framework to expand and redesign education programs [45]. As a consequence, it seems reasonable to suggest that when developing and up-dating the content of a faculty’s pain curriculum the aim should be the full implementation of the IASP pain curriculum.

4.5 Challenges of the pain curriculum

In our study only one third of the UASs believed that their students received an adequate amount of pain education. Challenges reported were reduction or lack of resources, the limitations of ECTS credits, insufficiency of contact hours, inflexibility of the curriculum, further education of teachers, and being up-to-date on the pain subject. These challenges are similar to those described in earlier research [13], [28]. Additional barriers that may inhibit change are the lack of pain competency standards in the licensing of health care professionals and minimal interprofessional learning [47]. Watt-Watson et al. conclude that influencing professional bodies to include entry-to-practice pain competencies may ultimately have the greatest impact on education and practice [48]. Integrating pain content into an already full curriculum is recognized as demanding but necessary, and resources are needed to facilitate the process [46]. Initiating a shift in beliefs and practice behaviors in any area is challenging and can only be sustained when supported by parallel changes in systems and policy [49].

4.6 Limitations

This study has limitations. Firstly, when the UASs were asked about the amount of pain education as a separate question 11 UASs (92%) reported an amount of pain education in some form; a pain course and/or integrated pain education. The contradictory answers that were clarified through contacting three UASs concerned these questions. Only seven UASs (58%) recognized all proposed forms of pain education. However, all UASs could answer the same question when it was put in the context of content of education (respondents had to choose between numbers of hours given). Secondly, even though our study evaluated time spent on multidisciplinary (interdisciplinary) management, it did not include a specific question concerning interprofessional education (IPE). Interprofessional pain education, for which the IASP has also established a curriculum [50], is one way of organizing pain education that has received increasing recognition [42], [46], [51]. The World Health Organization (WHO) emphasizes that IPE is “a necessary step in preparing a collaborative practice-ready health workforce that is better prepared to respond to local health needs” [52].

5 Conclusions

Our results indicate that more contact hours are devoted to pain education on the Finnish UASs’ physiotherapy programs at bachelor’s level, than has previously been reported in faculty surveys. A separate pain course is one way to ensure a sufficient amount of pain education. Overall, despite a sufficient time devoted to pain education, some essential pain contents were inadequately covered.

6 Implications

The study contributes information on how pain education can be organized on physiotherapy programs at undergraduate level. Besides a sufficient amount of pain education, which can be ensured by a separate pain course, attention should be paid to pain education content being up-to-date. This could help in estimating the different proportions of pain content needed in educational settings. Efforts should also be made at keeping integrated pain education well-coordinated and purposeful. There is a need for further research estimating the effectiveness of pain education according to the different ways in which it is organized. There is also a need to investigate whether more hours allocated to pain education results in better understanding and professional skills.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Professor Sluka for permission to use and adapt the questionnaire developed by Hoeger Bement and Sluka [12] for research purposes in Finland.

-

Authors’ statements

-

Research funding: None.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest.

-

Informed consent: Research permission was received from the Universities of Applied Sciences in Finland in October 2017.

-

Ethical approval: This study was granted ethical approval by The Research Ethics Board of Åbo Akademi University, Vaasa, Finland, in August 2017.

-

Author contributions

-

JE contributed to the design of the study, data collection, data analysis, discussed the results, and drafted the manuscript. JK contributed to the design of the study, data analysis, discussed the results, and commented on the manuscript. PS discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

References

[1] International Association for the Study of Pain. Declaration of Montreal. 2010. Available at: https://s3.amazonaws.com/rdcms-iasp/files/production/public/Content/NavigationMenu/Advocacy/DeclarationOfMontreal.pdf. Accessed: 28 Apr 2018.Suche in Google Scholar

[2] Gatchel RJ, Peng YB, Peters ML, Fuchs PN, Turk DC. The biopsychosocial approach to chronic pain: scientific advances and future directions. Psychol Bull 2007;133:581–624.10.1037/0033-2909.133.4.581Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[3] Sessle BJ. Unrelieved pain: a crisis. Pain Res Manag 2011;16:416–20.10.1155/2011/513423Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[4] Linton SJ, Flink IK, Vlaeyen JWS. Understanding the etiology of chronic pain from a psychological perspective. Phys Ther 2018;98:315–24.10.1093/ptj/pzy027Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[5] Jones L. Implications of IASP core curriculum for pre-registration physiotherapy education. Rev Pain 2009;3:11–5.10.1177/204946370900300104Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[6] International Association for the Study of Pain. IASP Curricula. 2018. Available at: https://www.iasp-pain.org/Education/CurriculaList.aspx?navItemNumber=647. Accessed: 18 Apr 2018.Suche in Google Scholar

[7] International Association for the Study of Pain. 2018 Global Year for Excellence in Pain Education. 2018. Available at: http://s3.amazonaws.com/rdcms-iasp/files/production/public/globalyear/2018%20Global%20Year%20for%20Excellence%20in%20Pain%20Education%20Brand%20Prospectus%201.17.18.pdf. Accessed: 30 Apr 2018.Suche in Google Scholar

[8] Watt-Watson J, McGillion M, Hunter J, Choiniere M, Clark AJ, Dewar A, Johnston C, Lynch M, Morley-Forster P, Moulin D, Thie N, von Baeyer CL, Webber K. A survey of prelicensure pain curricula in health science faculties in Canadian universities. Pain Res Manag 2009;14:439–44.10.1155/2009/307932Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[9] Briggs EV, Carr ECJ, Whittaker MS. Survey of undergraduate pain curricula for healthcare professionals in the United Kingdom. Eur J Pain 2011;15:789–95.10.1016/j.ejpain.2011.01.006Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[10] Leegaard M, Valeberg BT, Haugstad GK, Utne I. Survey of pain curricula for healthcare professionals in Norway. Vård i Norden 2014;34:42–5.10.1177/010740831403400110Suche in Google Scholar

[11] Scudds RJ, Scudds RA, Simmonds MJ. Pain in the physical therapy (pt) curriculum: a faculty survey. Physiother Theory Pract 2001;1:239–56.10.1080/095939801753385744Suche in Google Scholar

[12] Hoeger Bement MK, Sluka KA. The current state of physical therapy pain curricula in the United States: a faculty survey. J Pain 2015;16:144–52.10.1016/j.jpain.2014.11.001Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[13] Hoeger Bement MK, St Marie BJ, Nordstrom TM, Christensen N, Mongoven JM, Koebner IJ, Fishman SM, Sluka KA. An Interprofessional consensus of core competencies for prelicensure education in pain management: curriculum application for physical therapy. Phys Ther 2014;94:451–65.10.2522/ptj.20130346Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[14] Breivik H, Collett B, Ventafridda V, Cohen R, Gallacher D. Survey of chronic pain in Europe: prevalence, impact on daily life, and treatment. Eur J Pain 2006;10:287–333.10.1016/j.ejpain.2005.06.009Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[15] Ministry of Social Affairs and Health in Finland: expert group on management of chronic pain and cancer pain. National action plan for treatment of chronic pain and cancer pain for 2017–2020. Reports and memorandums of the Ministry of Social Affairs and Health. 2017;4. Available at: http://julkaisut.valtioneuvosto.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/79292/Rap_2017_4.pdf. Accessed: 3 Aug 2017.Suche in Google Scholar

[16] Mezei L, Murinson BB; Johns Hopkins Pain Curriculum Development Team. Pain education in North American medical schools. J Pain 2011;12:1199–208.10.1016/j.jpain.2011.06.006Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[17] Murinson BB, Gordin V, Flynn S, Driver LC, Gallagher RM, Grabois M; Medical Student Education Sub-Committee of the American Academy of Pain Medicine. Recommendations for a new curriculum in pain medicine for medical students: toward a career distinguished by competence and compassion. Pain Med 2013;14:345–50.10.1111/pme.12051Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[18] Thong ISK, Jensen MP, Miró J, Tan G. The validity of pain intensity measures: what do the NRS, VAS, VRS, and FPS-R measure? Scand J Pain 2018;18:99–107.10.1515/sjpain-2018-0012Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[19] Fairbank JC, Pynsent PB. The Oswestry disability index. Spine 2000;25:2940–52.10.1097/00007632-200011150-00017Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[20] Burckhardt CS, Clark SR, Bennett RM. The fibromyalgia impact questionnaire: development and validation. J Rheumatol 1991;18:728–33.Suche in Google Scholar

[21] Enright PL. The six-minute walk test. Respir Care 2003;48: 783–5.Suche in Google Scholar

[22] Weiner DK, Duncan PW, Chandler J, Studenski SA. Functional reach: a marker of physical frailty. J Am Geriatr Soc 1992;40:203–7.10.1111/j.1532-5415.1992.tb02068.xSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[23] Waddell G, Newton M, Henderson I, Somerville D, Main CJ. A Fear-avoidance beliefs questionnaire (FABQ) and the role of fear-avoidance beliefs in chronic low back pain and disability. Pain 1993;52:157–68.10.1016/0304-3959(93)90127-BSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[24] Poquet N, Lin C. The brief pain inventory (BPI). J Physiother 2015;62:52.10.1016/j.jphys.2015.07.001Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[25] Linton SJ, Boersma K. Early identification of patients at risk of developing a persistent back problem: the predictive validity of the Orebro Musculoskeletal Pain Questionnaire. Clin J Pain 2003;19:80–6.10.1097/00002508-200303000-00002Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[26] International Association for the Study of Pain. IASP Curriculum Outline on Pain for Physical Therapy. 2018. Available at: https://www.iasp-pain.org/Education/CurriculumDetail.aspx?ItemNumber=2055. Accessed: 18 Apr 2018.Suche in Google Scholar

[27] International Association for the Study of Pain. IASP Curriculum Outline on Pain for Physical Therapy. 2012. Available at: https://www.iasp-pain.org/Education/CurriculumDetail.aspx?ItemNumber=2055. Accessed: 12 Apr 2017.Suche in Google Scholar

[28] Carr ECJ, Briggs EV, Briggs M, Allcock N, Black P, Jones D. Understanding factors that facilitate the inclusion of pain education in undergraduate curricula: perspectives from a UK survey. Br J Pain 2016;10:100–7.10.1177/2049463716634377Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[29] Pöyhiä R, Kalso E. Pain related undergraduate teaching in medical faculties in Finland. Pain 1999;79:121–5.10.1016/S0304-3959(98)00160-2Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[30] Jones LE, Hush JM. Pain education for physiotherapists: is it time for curriculum reform? J Physiother 2011;57:207–8.10.1016/S1836-9553(11)70049-2Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[31] Strong J, Meredith P, Darnell R, Chong M, Roche P. Does participation in a pain course based on the International Association for the Study of Pain’s curricula guidelines change student knowledge about pain? Pain Res Manag 2003;8:137–42.10.1155/2003/263802Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[32] Colleary G, O’Sullivan K, Giffin D, Ryan CG, Martin DJ. Effect of pain neurophysiology education on physiotherapy student’s understanding of chronic pain, clinical recommendations and attitudes towards people with chronic pain: a randomised controlled trial. Physiotherapy 2017;103:423–9.10.1016/j.physio.2017.01.006Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[33] Mine K, Gilbert S, Tsuchiya J, Nakayama T. The short-term effects of a single lecture on undergraduate physiotherapy students’ understanding regarding pain neurophysiology: a prospective case series. J Musculoskeletal Disord Treat 2017;3:1–6.10.23937/2572-3243.1510041Suche in Google Scholar

[34] Cox T, Louw A, Puentedura EJ. An abbreviated therapeutic neuroscience education session improves pain knowledge in first-year physical therapy students but does not change attitudes or beliefs. J Man Manip Ther 2017;25:11–21.10.1080/10669817.2015.1122308Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[35] Moseley GL, Butler DS. Fifteen years of explaining pain: the past, present, and future. J Pain 2015;16:807–13.10.1016/j.jpain.2015.05.005Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[36] Thacker MA, Moseley GL. First-person neuroscience and the understanding of pain. Med J Aust 2012;196:410–1.10.5694/mja12.10468Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[37] Chi MT, Roscoe RD, Slotta JD, Roy M, Chase CC. Misconceived causal explanations for emergent processes. Cogn Sci 2012;36:1–61.10.1111/j.1551-6709.2011.01207.xSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[38] Foster NE, Anema JR, Cherkin D, Chou R, Cohen SP, Gross DP, Ferreira PH, Fritz JM, Koes BW, Peul W, Turner JA, Maher CG; On Behalf of the Lancet Low Back Pain Series Working Group. Prevention and treatment of low back pain: evidence, challenges, and promising directions. Lancet 2018;391: 2368–2383.10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30489-6Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[39] Richmond H, Hall AM, Copsey B, Hansen Z, Williamson E, Hoxey-Thomas N, Cooper Z, Lamb SE. The effectiveness of cognitive behavioural treatment for non-specific low back pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2015;10:e0134192.10.1371/journal.pone.0134192Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[40] O’Sullivan PB, Caneiro JP, O’Keeffe M, Smith A, Dankaerts W, Fersum K, O’Sullivan K. Cognitive functional therapy: an integrated behavioral approach for the targeted management of disabling low back pain. Phys Ther 2018;98:408–23.10.1093/ptj/pzy022Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[41] Gatchel RJ, McGreary DD, McGreary CA, Lippe B. Interdisciplinary chronic pain management: past, present, and future. Am Psychol 2014;69:119–30.10.1037/a0035514Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[42] Fishman SM, Young HM, Arwood EL, Chou R, Herr K, Murinson BB, Watt-Watson J, Carr DB, Gordon DB, Stevens BJ, Bakerjian D, Ballantyne JC, Courtenay M, Djukic M, Koebner IJ, Mongoven JM, Paice JA, Prasad R, Singh N, Sluka KA, et al. Core competencies for pain management: results of an interprofessional consensus summit. Pain Med 2013;14:971–81.10.1111/pme.12107Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[43] Watt-Watson J, Hunter J, Pennefather P, Librach L, Raman-Wilms L, Schreiber M, Lax L, Stinson J, Dao T, Gordon A, Mock D, Salter M. An integrated undergraduate pain curriculum, based on IASP curricula, for six health science faculties. Pain 2004;110:140–8.10.1016/j.pain.2004.03.019Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[44] Hunter J, Watt-Watson J, McGillion M, Raman-Wilms L, Cockburn L, Lax L, Stinson J, Cameron A, Dao T, Pennefather P, Schreiber M, Librach L, Kavanagh T, Gordon A, Cullen N, Mock D, Salter M. An interfaculty pain curriculum: lessons learned from six years experience. Pain 2008;140:74–86.10.1016/j.pain.2008.07.010Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[45] Hush JM, Nicholas M, Dean CM. Embedding the IASP pain curriculum into a 3-year pre-licensure physical therapy program: redesigning pain education for future clinicians. Pain Reports 2018;3:e645.10.1097/PR9.0000000000000645Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[46] Watt-Watson J, Lax L, Davies R, Langlois S, Oskarsson J, Raman-Wilms L. The pain interprofessional curriculum design model. Pain Med 2017;18:1040–8.10.1093/pm/pnw337Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[47] Watt-Watson J, Murinson BB. Current challenges in pain education. Pain Manag 2013;3:351–7.10.2217/pmt.13.39Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[48] Watt-Watson J, Peter E, Clark AJ, Dewar A, Hadjistavropoulos T, Morley-Forster P, O’Leary C, Raman-Wilms L, Unruh A, Webber K, Campbell-Yeo M. The ethics of Canadian entry-to-practice pain competencies: how are we doing? Pain Res Manag 2013;18:25–32.10.1155/2013/179320Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[49] Slater H, Briggs A. Physiotherapists must collaborate with other stakeholders to reform pain management. J Physiother 2012;58:65.10.1016/S1836-9553(12)70082-6Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[50] International Association for the Study of Pain. IASP Interprofessional Pain Curricula Outline. 2018. Available at: https://www.iasp-pain.org/Education/CurriculumDetail.aspx?ItemNumber=2057. Accessed: 21 Apr 2018.Suche in Google Scholar

[51] Dow A, Thibault G. Interprofessional education – a foundation for a new approach to health care. N Engl J Med 2017;377: 803–5.10.1056/NEJMp1705665Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[52] World Health Organization. Framework for action on interprofessional education and collaborative practice. 2010. Available at: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/70185/1/WHO_HRH_HPN_10.3_eng.pdf?ua=1. Accessed: 8 Jan 2018.Suche in Google Scholar

©2018 Scandinavian Association for the Study of Pain. Published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston. All rights reserved.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Editorial comment

- Support for mirror therapy for phantom and stump pain in landmine-injured patients

- Lifting with straight legs and bent spine is not bad for your back

- Bipolar radiofrequency neurotomy for spinal pain – a promising technique but still some steps to go

- Topical review

- Prevalence, localization, perception and management of pain in dance: an overview

- Clinical pain research

- Pain assessment in native and non-native language: difficulties in reporting the affective dimensions of pain

- Colored body images reveal the perceived intensity and distribution of pain in women with breast cancer treated with adjuvant taxanes: a prospective multi-method study of pain experiences

- Physiotherapy pain curricula in Finland: a faculty survey

- Mirror therapy for phantom limb and stump pain: a randomized controlled clinical trial in landmine amputees in Cambodia

- Pain and alcohol: a comparison of two cohorts of 60 year old women and men: findings from the Good Aging in Skåne study

- Prolonged, widespread, disabling musculoskeletal pain of adolescents among referrals to the Pediatric Rheumatology Outpatient Clinic from the Päijät-Häme Hospital District in southern Finland

- Impact of the economic crisis on pain research: a bibliometric analysis of pain research publications from Ireland, Greece, and Portugal between 1997 and 2017

- Measurement of skin conductance responses to evaluate procedural pain in the perioperative setting

- Original experimental

- An observational study of pain self-management strategies and outcomes: does type of pain, age, or gender, matter?

- Fibromyalgia patients and healthy volunteers express difficulties and variability in rating experimental pain: a qualitative study

- Effect of the market withdrawal of dextropropoxyphene on use of other prescribed analgesics

- Observational study

- Winning or not losing? The impact of non-pain goal focus on attentional bias to learned pain signals

- Gabapentin and NMDA receptor antagonists interacts synergistically to alleviate allodynia in two rat models of neuropathic pain

- Offset analgesia is not affected by cold pressor induced analgesia

- Central and peripheral pain sensitization during an ultra-marathon competition

- Reduced endogenous pain inhibition in adolescent girls with chronic pain

- Evaluation of implicit associations between back posture and safety of bending and lifting in people without pain

- Assessment of CPM reliability: quantification of the within-subject reliability of 10 different protocols

- Cerebrospinal fluid cutaneous fistula after neuraxial anesthesia: an effective treatment approach

- Pain in the hand caused by a previously undescribed mechanism with possible relevance for understanding regional pain

- The response to radiofrequency neurotomy of medial branches including a bipolar system for thoracic facet joints

- Letter to the Editor

- Diagnosis of carpal tunnel syndrome – implications for therapy

- Reply to the Letter to the Editor by Ly-Pen and Andréu

- Letter to the Editor regarding “CT guided neurolytic blockade of the coeliac plexus in patients with advanced and intractably painful pancreatic cancer”

- Reply to comments from Ulf Kongsgaard to our study

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Editorial comment

- Support for mirror therapy for phantom and stump pain in landmine-injured patients

- Lifting with straight legs and bent spine is not bad for your back

- Bipolar radiofrequency neurotomy for spinal pain – a promising technique but still some steps to go

- Topical review

- Prevalence, localization, perception and management of pain in dance: an overview

- Clinical pain research

- Pain assessment in native and non-native language: difficulties in reporting the affective dimensions of pain

- Colored body images reveal the perceived intensity and distribution of pain in women with breast cancer treated with adjuvant taxanes: a prospective multi-method study of pain experiences

- Physiotherapy pain curricula in Finland: a faculty survey

- Mirror therapy for phantom limb and stump pain: a randomized controlled clinical trial in landmine amputees in Cambodia

- Pain and alcohol: a comparison of two cohorts of 60 year old women and men: findings from the Good Aging in Skåne study

- Prolonged, widespread, disabling musculoskeletal pain of adolescents among referrals to the Pediatric Rheumatology Outpatient Clinic from the Päijät-Häme Hospital District in southern Finland

- Impact of the economic crisis on pain research: a bibliometric analysis of pain research publications from Ireland, Greece, and Portugal between 1997 and 2017

- Measurement of skin conductance responses to evaluate procedural pain in the perioperative setting

- Original experimental

- An observational study of pain self-management strategies and outcomes: does type of pain, age, or gender, matter?

- Fibromyalgia patients and healthy volunteers express difficulties and variability in rating experimental pain: a qualitative study

- Effect of the market withdrawal of dextropropoxyphene on use of other prescribed analgesics

- Observational study

- Winning or not losing? The impact of non-pain goal focus on attentional bias to learned pain signals

- Gabapentin and NMDA receptor antagonists interacts synergistically to alleviate allodynia in two rat models of neuropathic pain

- Offset analgesia is not affected by cold pressor induced analgesia

- Central and peripheral pain sensitization during an ultra-marathon competition

- Reduced endogenous pain inhibition in adolescent girls with chronic pain

- Evaluation of implicit associations between back posture and safety of bending and lifting in people without pain

- Assessment of CPM reliability: quantification of the within-subject reliability of 10 different protocols

- Cerebrospinal fluid cutaneous fistula after neuraxial anesthesia: an effective treatment approach

- Pain in the hand caused by a previously undescribed mechanism with possible relevance for understanding regional pain

- The response to radiofrequency neurotomy of medial branches including a bipolar system for thoracic facet joints

- Letter to the Editor

- Diagnosis of carpal tunnel syndrome – implications for therapy

- Reply to the Letter to the Editor by Ly-Pen and Andréu

- Letter to the Editor regarding “CT guided neurolytic blockade of the coeliac plexus in patients with advanced and intractably painful pancreatic cancer”

- Reply to comments from Ulf Kongsgaard to our study