Abstract

Background and aims

The clinical management of neuropathic pain remains a challenge. We examined the interaction between gabapentin and NMDA receptor antagonists dextromethrophan and MK-801 in alleviating neuropathic pain-like behaviors in rats after spinal cord or sciatic nerve injury.

Methods

Female and male rats were produced with Ischemic spinal cord injury and sciatic nerve injury. Gabapentin, dextromethorphan, MK-801 or drug combinations were injected with increasing doses. Mechanical response thresholds were tested with von Frey hairs to graded mechanical touch/pressure, and ethyl chloride spray was applied to assess the cold sensitivity before and after injuries.

Results

In spinally injured rats, gabapentin and dextromethorphan did not affect allodynia-like behaviors at doses of 30 and 20 mg/kg, respectively. In contrast, combination of 15 or 30 mg/kg gabapentin with dextromethorphan at 10 mg/kg produced total alleviation of allodynia to mechanical or cold stimulation. Further reducing the dose of gapapentin to 7.5 mg/kg and dextromethorphan to 5 mg/kg still produced significant effect. MK-801, another NMDA receptor antagonist, also enhanced the effect of gabapentin in spinally injured rats. Similar synergistic anti-allodynic effect between dextromethorphan and gabapentin was also observed in a rat model of partial sciatic nerve injury. No increased side effect was seen following the combination between gabapentin and dextromethorphan.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the present study suggested that combining NMDA receptor antagonists with gabapentin could provide synergistic effect to alleviate neuropathic pain and reduced side effects.

Implications

Combining NMDA receptor antagonists with gabapentin may provide a new approach in alleviating neuropathic pain with increased efficacy and reduced side effects.

1 Introduction

Anticonvulsants, such as carbamazepine or phenytoin, have been traditionally used for the management of neuropathic pain. Their efficacy has, however, not been unequivocally established for many types of neuropathic pain and they are often associated with side effects [1], [2]. More recently, the antiepileptics gabapentin has been increasingly used as an analgesic in neuropathic pain [1], [2], [3]. Although it was found to exert analgesic effect superior to placo in a large number of randomized, placebo controlled, double-blind clinical trials in conditions such as postherpetic neuralgia, painful diabetic neuropathy and central neuropathic pain, gabapentin only provide some degree of pain relief in a minority of neuropathic pain patients [4], [5], [6], [7].

Another class of compounds believed to be useful in neuropathic pain is antagonists of NMDA receptors for glutamate [1], [8], [9]. Such promise was derived from the well established involvement of NMDA receptors in plasticity after injury to the nervous system as well as its pivotal role in central sensitization and hyperalgesia [8]. However, NMDA antagonists in general produced many side effects and clinical trials with several clinically available compounds with NMDA receptor blocking property in neuropathic pain have produced at best conflicting results [1], [8], [9], [10].

It is also well established in rodent models that the antinociceptive effect of morphine is potentiated by NMDA receptor antagonists that is mediated by an interaction between the activation of the μ-opioid and NMDA receptors at cellular level [11], [12]. NMDA antagonists also reversed morphine tolerance [11]. The interaction between NMDA receptor antagonists and other analgesics is however less known. In the present study, we evaluated the analgesic interaction between NMDA receptor antagonists, MK-801 and dextromethorphan, and gabapentin using two rat models of neuropathic pain after spinal cord or sciatic nerve injury.

2 Materials and methods

Male and female Sprague-Dawley rats (Mollegård, Denmark) weighing 200–250 g at the start of the experiments were used. All experimental procedures were approved by the local research Ethics Committee.

2.1 Photochemically-induced ischemic spinal cord injury

Ischemic spinal cord injury was produced in female SD rat weighing 200 g according to methods described previously [13]. In brief, rats were anesthetized with chloral hydrate (300 mg/kg, i.p.) and a midline incision was made on the skin overlying vertebral segments T 12-L 1. The animals were positioned beneath an argon laser beam and irradiated for 10 min with the beam directed towards vertebral segment T 12 or T 13 (spinal segments L 3–5). Immediately prior to and 5 min after the start of the irradiation, erythrosin B (Red N°3, Aldrich-Chemie, Steinheim, Germany) dissolved in 0.9% saline was injected intravenously through the tail vein at a dose of 32.5 mg/kg. A tunable argon ion laser (Innova model 70, Coherent Laser Product Division, Palo Alto, CA, USA) operating at 514 nm was used. The average beam output power was 160 mW. The beam covers the entire width of the vertebra and the length is approximately 1–2 mm. After irradiation, the wound was closed in layers and the rats were allowed to recover. Bladder was empted manually for 1 week.

2.2 Assessment of mechanical and cold sensitivity after spinal cord injury

The behavioral assessments were conducted blindly as the groups of drugs administered. Vocalization thresholds to graded mechanical touch/pressure were tested with calibrated von Frey hairs (ranging from 0.04 to 0.2155 mN, Stoelting, Chicago, IL, USA). During testing the rats were gently restrained in a standing position and the von Frey hair was pushed onto the skin until the filament became bent. The frequency of stimulation was about 1/s and at each intensity, the stimuli were applied 5–10 times. The intensity of stimulation which induced consistent vocalization (>75% response rate) was considered as pain threshold.

The response of rats to brushing stimulation was tested with the blunt point of a pencil gently stroking the skin on the trunk in a rostro-caudal direction. The frequency of the stimulation was about 1 Hz and responses were graded with a score of 0=no observable response; 1=transient vocalization and moderate effort to avoid probe; 2=consistent vocalization and aversive reactions and 3=sustained and prolonged vocalization and aggressive behaviors. Normal rats exhibited no reactions to such brush stimuli (score 0).

Responses to cold was tested with ethyl chloride spray applied to the shaved allodynic skin area. The response was graded with a score of 0=no observable response; 1=localized response (skin twitch and contraction), no vocalization; 2=transient vocalization, moderate struggle and 3=sustained vocalization and aggression. Normal rats usually had response score of 0 or 1.

2.3 Photochemically-induced sciatic nerve injury

Male SD rats were anesthetized by chloral hydrate (300 mg/kg, i.p.) and the left sciatic nerve was exposed. The nerve trunk was gently dissected free from the surrounding tissue over a distance of about 1 cm proximal to trifurcation. The exposed nerve was irradiated with an argon ion laser for 2 min. The irradiation was performed with a knife-edged beam across the nerve. Aluminum foil was placed under the nerve to isolate the surrounding tissue and to reflect light. Just before the irradiation, erythrosin B (Aldrich, USA 32.5 mg/kg dissolved in 0.9% saline) was injected i.v. via the tail vein. After the surgery the wounds were closed in layers and the rats were returned to the cages for subsequent behavioral tests.

2.4 Assessment of mechanical sensitivity after sciatic nerve injury

The behavioral assessments were conducted blindly as the groups of drugs administered. To test of sensitivity to mechanical stimulation, the rats were placed in plastic cages with a metal mesh floor. The plantar surface of the hind paws was stimulated with a set of calibrated von Frey hairs (ranging from 0.04 to 0.2155 mN, Stoelting, Chicago, IL, USA) with increasing force until the animal withdrew the limb. Each monofilament was applied 5 times. The withdrawal threshold was taken as the force at which the animal withdrew the paw from at least three out of five consecutive stimuli.

2.5 Drugs and statistics

Gabapentin, dextromethorphan and MK-801 were obtained from Research Biochem Inc. (Natick, MA, USA) and dissolved in physiological saline. All drugs were injected i.p. in a volume of 0.1 mL/kg. The behavioral assessments were conducted blindly. Data are expressed as median±median absolute deviation (MAD) and analyzed with Friedman one way analysis of variance for repeated measurements and Wilcoxon signed-ranks test.

3 Results

3.1 Spinally injured rats

As previously described, some spinally injured rats developed allodynia-like behavior manifested as reduction in vocalization threshold to mechanical touch stimulation applied by the von-Frey hairs or by brush and as increased response to cold stimulation applied by ethyl chloride spray. And saline treatment has no effect on either mechanical or cold sensitivity on our neuropathic pain models [13], [14], [15].

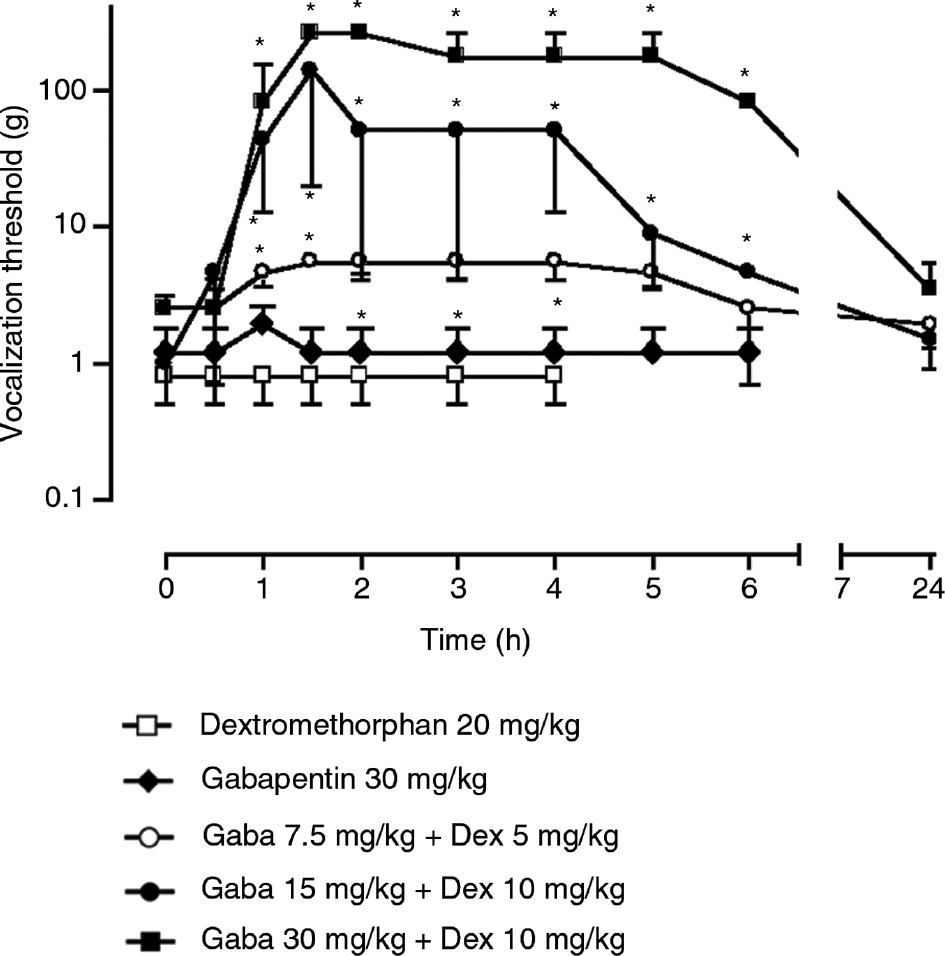

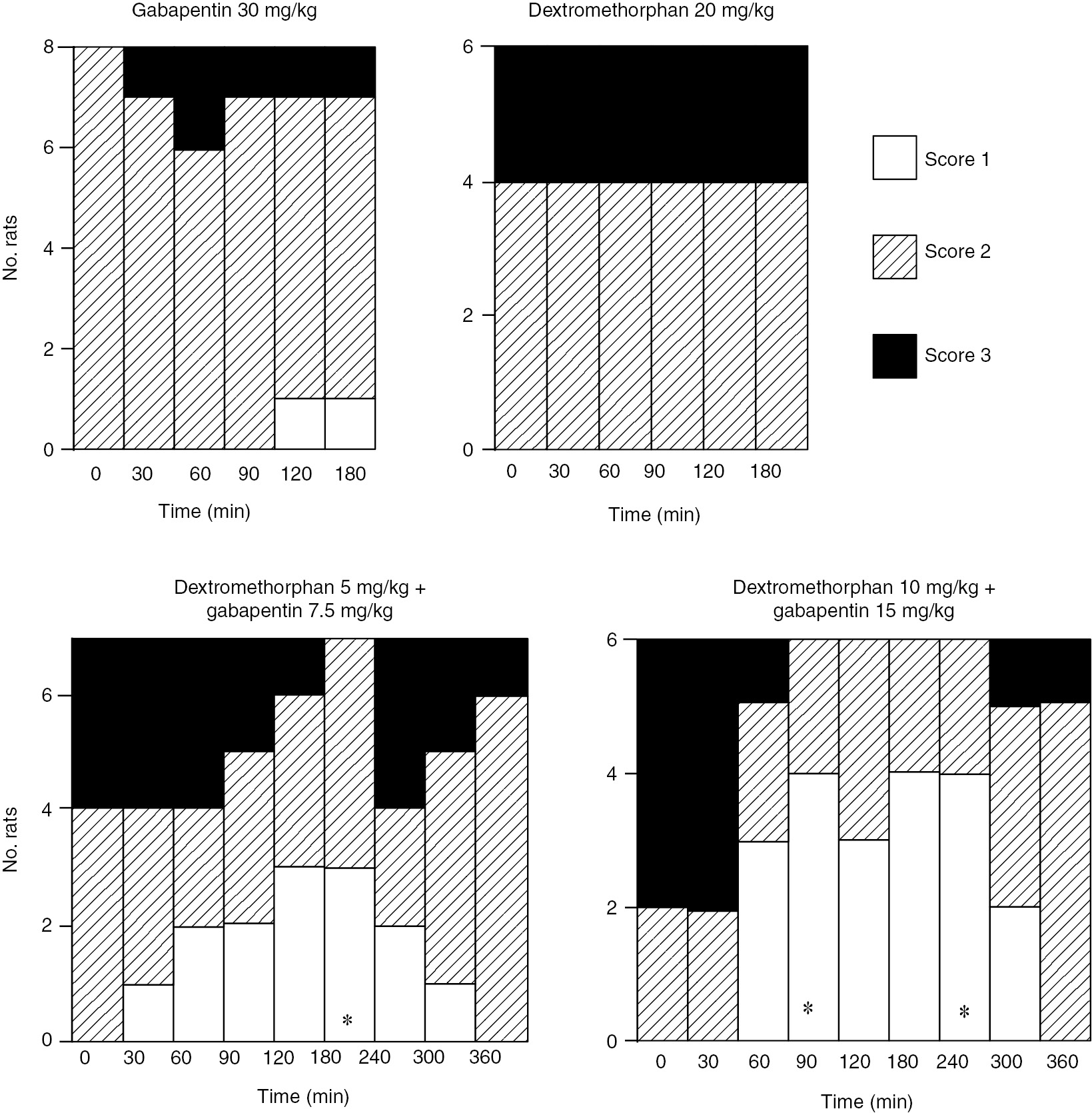

I.p. dextromethorphan or gabapentin did not alleviate allodynia-like behaviors at the doses up to 20 or 30 mg/kg, respectively (Figs. 1–3). Further increasing the dose of dextromethorphan or gabapentin produced numerous side effects, including sedation and motor impairment for gabapentin and hyperactivity for dextromethorphan. Combining gabapentin (7.5, 15 or 30 mg/kg) with low doses of dextromethorphan (5 or 10 mg/kg) significantly increased vocalization threshold to von-Frey hair stimulation (Fig. 1), reduced and normalized increased response to brush (Fig. 2) or cold (Fig. 3) stimulation. The anti-allodynic effect of dextromethorphan and gabapentin is long-lasting, but reversible. At doses used, gabapentin, dextromethorphan or combination did not produce observable side effects, such as sedation, motor impairments or hyperactivity.

Effects of gabapentin at 30 mg/kg, dextromethorphan at 20 mg/kg or combination of the two compounds on vocalization threshold to von-Frey hair stimulation in spinally injured rats. The data is expressed as median±MAD (median absolute deviation) and 6–8 rats were included in each group. *=p<0.05 compared to time 0 with Wilcoxon signed-rank test. Friedman ANOVA with repeated measures indicated a significant general difference for the three drug combination groups (p<0.01).

Effect of gabapentin at 30 mg/kg, dextromethorphan at 20 mg/kg or combination of the two compounds on responses of spinally injured rats to brushing stimulation. The responses were graded and number of rats exhibiting different level of responses were shown. *=p<0.05 compared to time 0 with Wilcoxon signed-ranks test.

Effect of gabapentin at 30 mg/kg, dextromethorphan at 20 mg/kg or combination of the two compounds on responses of spinally injured rats to cold stimulation. The responses were graded and number of rats exhibiting different level of responses were shown. *=p<0.05 compared to time 0 with Wilcoxon signed-ranks test.

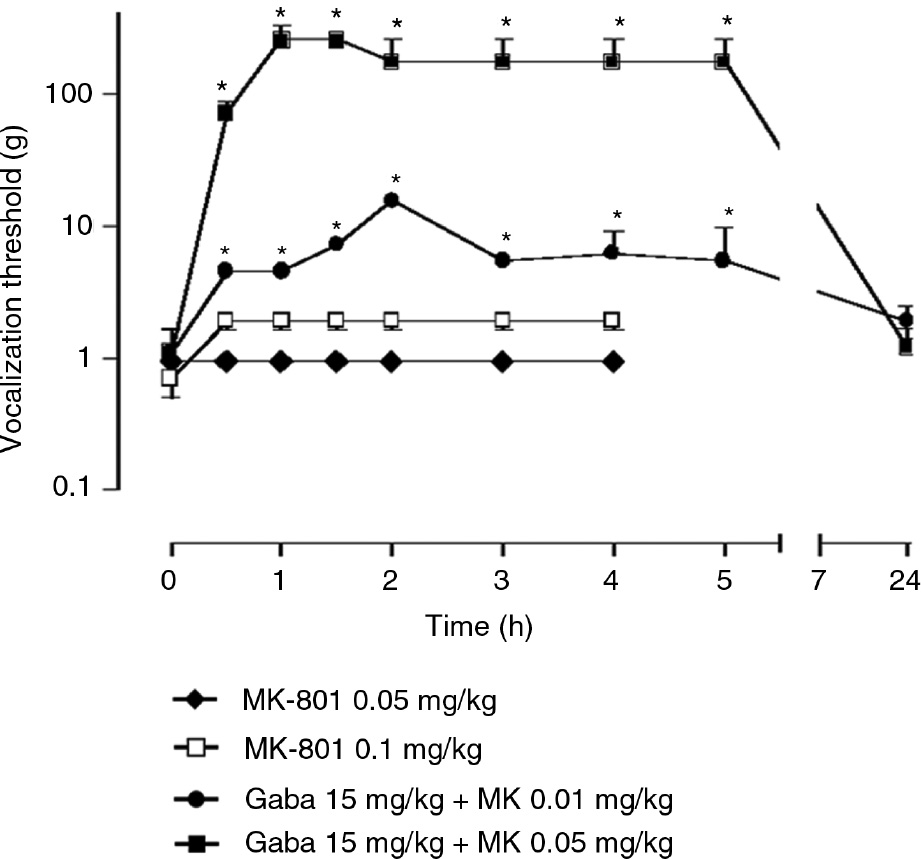

I.p. MK-801 at 0.05 or 0.1 mg/kg also did not affect mechanical allodynia-like behavior in spinally injured rats whereas combination of small doses (0.01 or 0.05 mg/kg) of MK-801 with 15 mg/kg gabapentin again significantly increased vocalization threshold to von-Frey stimulation (Fig. 4). The cold allodynia was also similarly reduced (not shown).

Effect of MK-801 at 0.05 or 0.1 mg/kg or combination with MK with gabapentin 15 mg/kg on vocalization threshold of spinally injured rats to von Frey stimulation. The data is shown as median±MAD (median absolute deviation) and *=p<0.05 compared to time 0 with Wilcoxon signed-ranks test. Friedman ANOVA with repeated measures indicated a significant general difference for the two drug combination groups (p<0.01).

3.2 Sciatic nerve injury

Rats subjected to ischemically-induced sciatic nerve injury developed mechanical hypersensitivity seen as bilaterally decreased paw withdrawal threshold to von-Frey hair stimulation which peaked at 1–2 weeks when the experiments were conducted. The mechanical hypersensitivity is more severe on the ipsilatera side to the irradiation than the contralateral side and the data from the ipsilateral were presented. I.p. dextormethorphan or gabapentin did not affect mechanical allodynia in sciatic nerve injured rats in the present experiments as doses up to 40 or 100 mg/kg despite the presence of side effects (Fig. 5). In contrast, combining gabapentin 30 mg/kg with 20 mg/kg dextromethorphan significantly increased paw withdrawal threshold to von-Frey stimulation in nerve injured rats (Fig. 5).

Effects of gabapentin at 100 mg/kg, dextromethorphan at 40 mg/kg or combination of dextromethorphan 20 mg/kg and gabapentin 30 mg/kg on paw withdrawal threshold after partial sciatic nerve injury. The data is expressed as median±MAD (median absolute deviation) and 6–8 rats were included in each group. *=p<0.05 compared to time 0 with Wilcoxon signed-rank test. Friedman ANOVA with repeated measures indicated a significant general difference for the drug combination groups (p<0.01).

4 Discussion

The present results showed that combining NMDA receptor antagonists and gabapentin produced synergistic antiallodynic effect in two rat models of neuropathic pain after spinal cord or sciatic nerve injury. The effect of the combination is clearly synergistic rather than additive since either drug along did not produce any effects at doses equal or even larger than that of the combination [16], [17]. At effective doses, the combination did not produce increased side effects in comparison to either drug alone. Thus, the present results support a potential clinical application of this combination strategy, particularly with NMDA antagonists that are clinically available, in treating patients with neuropathic pain of central and/or peripheral origins.

The mechanisms by which synergism between dextromethorphan and gabapentin occurs are unclear. The analgesic effect of gabapentin may be related to its binding to the α2δ subunit of the voltage-dependent calcium channels (VDCCs) [18], [19]. Thus, such synergism may be derived from a simultaneous reduction in calcium entry through blockade of VDCCs and NMDA receptor/channels. In this context, it is noteworthy that gabapentin per se often produced limited effect on various types of Ca2+ currents [20], [21], [22], [23]. In addition, such interaction may also occur directly at the NMDA receptor complex. Previous work has shown that the anti-hyperalgesic effect of gabapentin was blocked by D-serine, an agonist at the glycine site of the NMDA receptor [24], [25]. The direct effect of gabapentin on NMDA receptor is, however, an enhancement of NMDA-evoked current in isolated neurons that may be difficult to reconcile with its analgesic effect [26], [27]. Gabapentin is also able to reduce glutamate release in some systems that may also contribute to its interaction with an additional blockade of the NMDA receptors [28], [29]. Finally, although dextormethorphan can also act on VDCCs [30], the fact that MK-801 also enhances the effect of gabapentin made it unlikely that such interaction take place solely at the VDCCs.

It is interesting to note that the synergism between dextromethorphan and gabapentin produces larger effect in spinally injured rats than in rats with sciatic nerve injury. This is possibly due to the fact that both drugs are less potent in the periphery vs. central model [17], [31] and may reflect different mechanisms for these two neuropathic pain models. Nonetheless, it is tempting to suggest that this combination may be particularly useful in treating spinal cord injury pain, a difficult clinical problem [32]. Our results also support the clinical observation [9] in which they showed that combination of dextromethorphan and gabapentin alleviated neuropathic pain in patients with spinal cord injury.

5 Conclusion

In conclusion, the present study suggested that combining NMDA receptor antagonists with gabapentin could provide a new approach in alleviating neuropathic pain with increased efficacy and reduced side effects.

-

Authors’ statements

-

Research Funding: This study was supported by the Swedish Science Council (Proj. 12168) and research funds of the Karolinska Institutet and China Scholarship Council.

-

Conflict of interest: We declare no conflicts of interests.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable.

-

Ethical approval: All experiments were approved by the local research ethics committee and were conducted in accordance with research guidelines of the International Association for the Study of Pain. We have used the minimal number of animals that is required to obtain results for statistical analysis.

References

[1] Sindrup SH, Jensen TS. Efficacy of pharmacological treatments of neuropathic pain: an update and effect related to mechanism of drug action. Pain 1999;83:389–400.10.1016/S0304-3959(99)00154-2Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[2] Jensen TS. Anticonvulsants in neuropathic pain: rationale and clinical evidence. Eur J Pain 2002;6(Suppl A):61–8.10.1053/eujp.2001.0324Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[3] Nicholson B. Gabapentin use in neuropathic pain syndromes. Acta Neurol Scand 2000;101:359–71.10.1034/j.1600-0404.2000.0006a.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[4] Backonja M, Beydoun A, Edwards KR, Schwartz SL, Fonseca V, Hes M, LaMoreaux L, Garofalo E. Gabapentin for the symptomatic treatment of painful neuropathy in patients with diabetes mellitus: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Assoc 1998;280:1831–6.10.1001/jama.280.21.1831Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[5] Rice AS, Maton S. Postherpetic Neuralgia Study Group. Gabapentin in postherpetic neuralgia: a randomised, double blind, placebo controlled study. Pain 2001;94:215–24.10.1016/S0304-3959(01)00407-9Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] Rowbotham M, Harden N, Stacey B, Bernstein P, Magnus-Miller L. Gabapentin for the treatment of postherpetic neuralgia: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Assoc 1998;280:1837–42.10.1001/jama.280.21.1837Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[7] Serpell MG. Neuropathic pain study g. Gabapentin in neuropathic pain syndromes: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Pain 2002;99:557–66.10.1016/S0304-3959(02)00255-5Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[8] Parsons CG. NMDA receptors as targets for drug action in neuropathic pain. Eur J Pharmacol 2001;429:71–8.10.1016/S0014-2999(01)01307-3Search in Google Scholar

[9] Sang CN. Glutamate receptor antagonists in central neuropathic pain following spinal cord injury. In: Yezierski RP, Burchiel KJ, editors. Spinal cord injury pain: assessment, mechanisms, managements. 23. Seattle: IASP Press, 2002:365–77.Search in Google Scholar

[10] Collins S, Sigtermans MJ, Dahan A, Zuurmond WW, Perez RS. NMDA receptor antagonists for the treatment of neuropathic pain. Pain Med 2010;11:1726–42.10.1111/j.1526-4637.2010.00981.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] Inturrisi CE. Preclinical evidence for a role of glutamatergic systems in opioid tolerance and dependence. Semin Neurosci 1997;9:110–9.10.1006/smns.1997.0111Search in Google Scholar

[12] Wiesenfeld-Hallin Z. Combined opioid-NMDA antagonist therapies. What advantages do they offer for the control of pain syndromes? Drugs 1998;55:1–4.10.2165/00003495-199855010-00001Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[13] Xu XJ, Hao JX, Aldskogius H, Seiger A, Wiesenfeld-Hallin Z. Chronic pain-related syndrome in rats after ischemic spinal cord lesion: a possible animal model for pain in patients with spinal cord injury. Pain 1992;48:279–90.10.1016/0304-3959(92)90070-RSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[14] Gao T, Hao JX, Wiesenfeld-Hallin Z, Xu XJ. Quantitative test of responses to thermal stimulation in spinally injured rats using a Peltier thermode: a new approach to study cold allodynia. J Neurosci Methods 2013;212:317–21.10.1016/j.jneumeth.2012.11.008Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[15] Gao T, Hao J, Wiesenfeld-Hallin Z, Wang DQ, Xu XJ. Analgesic effect of sinomenine in rodents after inflammation and nerve injury. Eur J Pharmacol 2013;721:5–11.10.1016/j.ejphar.2013.09.062Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[16] Xu XJ, Alster P, Wu WP, Hao JX, Wiesenfeld-Hallin Z. Increased level of cholecystokinin in cerebrospinal fluid is associated with chronic pain-like behavior in spinally injured rats. Peptides 2001;22:1305–8.10.1016/S0196-9781(01)00456-9Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[17] Hao JX, Xu XJ. Treatment of a chronic allodynia-like response in spinally injured rats: effects of systemically administered excitatory amino acid receptor antagonists. Pain 1996;66:279–85.10.1016/0304-3959(96)03019-9Search in Google Scholar

[18] Rose MA, Kam PC. Gabapentin: pharmacology and its use in pain management. Anaesthesia 2002;57:451–62.10.1046/j.0003-2409.2001.02399.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[19] Gee NS, Brown JP, Dissanayake VU, Offord J, Thurlow R, Woodruff GN. The novel anticonvulsant drug, gabapentin (Neurontin), binds to the alpha2delta subunit of a calcium channel. J Biol Chem 1996;271:5768–76.10.1074/jbc.271.10.5768Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[20] Rock DM, Kelly KM, Macdonald RL. Gabapentin actions on ligand- and voltage-gated responses in cultured rodent neurons. Epilepsy Res 1993;16:89–98.10.1016/0920-1211(93)90023-ZSearch in Google Scholar

[21] Stefani A, Spadoni F, Bernardi G. Gabapentin inhibits calcium currents in isolated rat brain neurons. Neuropharmacology 1998;37:83–91.10.1016/S0028-3908(97)00189-5Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[22] Fink K, Meder W, Dooley DJ, Gothert M. Inhibition of neuronal Ca(2+) influx by gabapentin and subsequent reduction of neurotransmitter release from rat neocortical slices. Br J Pharmacol 2000;130:900–6.10.1038/sj.bjp.0703380Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[23] Martin DJ, McClelland D, Herd MB, Sutton KG, Hall MD, Lee K, Pinnock RD, Scott RH. Gabapentin-mediated inhibition of voltage-activated Ca2+ channel currents in cultured sensory neurones is dependent on culture conditions and channel subunit expression. Neuropharmacology 2002;42:353–66.10.1016/S0028-3908(01)00181-2Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[24] Singh L, Field MJ, Ferris P, Hunter JC, Oles RJ, Williams RG, Woodruff GN. The antiepileptic agent gabapentin (Neurontin) possesses anxiolytic-like and antinociceptive actions that are reversed by D-serine. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1996;127:1–9.10.1007/BF02805968Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[25] Jun JH, Yaksh TL. The effect of intrathecal gabapentin and 3-isobutyl gamma-aminobutyric acid on the hyperalgesia observed after thermal injury in the rat. Anesth Analg 1998;86:348–54.10.1213/00000539-199802000-00025Search in Google Scholar

[26] Shimoyama M, Shimoyama N, Hori Y. Gabapentin affects glutamatergic excitatory neurotransmission in the rat dorsal horn. Pain 2000;85:405–14.10.1016/S0304-3959(99)00283-3Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[27] Gu Y, Huang LY. Gabapentin actions on N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor channels are protein kinase C-dependent. Pain 2001;93:85–92.10.1016/S0304-3959(01)00297-4Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[28] Dooley DJ, Mieske CA, Borosky SA. Inhibition of K(+)-evoked glutamate release from rat neocortical and hippocampal slices by gabapentin. Neurosci Lett 2000;280:107–10.10.1016/S0304-3940(00)00769-2Search in Google Scholar

[29] Maneuf YP, Hughes J, McKnight AT. Gabapentin inhibits the substance P-facilitated K(+)-evoked release of [(3)H]glutamate from rat caudial trigeminal nucleus slices. Pain 2001;93:191–6.10.1016/S0304-3959(01)00316-5Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[30] Lipton SA. Prospects for clinically tolerated NMDA antagonists: open-channel blockers and alternative redox states of nitric oxide. Trends Neurosci 1993;16:527–32.10.1016/0166-2236(93)90198-USearch in Google Scholar

[31] Hao JX, Xu XJ, Urban L, Wiesenfeld-Hallin Z. Repeated administration of systemic gabapentin alleviates allodynia-like behaviors in spinally injured rats. Neurosci Lett 2000;280: 211–4.10.1016/S0304-3940(00)00787-4Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[32] Yezierski RP, Burchiel KJ. Spinal injury pain: assessment, mechanism, management. Progress in pain research and management. Seattle: IASP Press, 2002:9–23.Search in Google Scholar

©2018 Scandinavian Association for the Study of Pain. Published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston. All rights reserved.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial comment

- Support for mirror therapy for phantom and stump pain in landmine-injured patients

- Lifting with straight legs and bent spine is not bad for your back

- Bipolar radiofrequency neurotomy for spinal pain – a promising technique but still some steps to go

- Topical review

- Prevalence, localization, perception and management of pain in dance: an overview

- Clinical pain research

- Pain assessment in native and non-native language: difficulties in reporting the affective dimensions of pain

- Colored body images reveal the perceived intensity and distribution of pain in women with breast cancer treated with adjuvant taxanes: a prospective multi-method study of pain experiences

- Physiotherapy pain curricula in Finland: a faculty survey

- Mirror therapy for phantom limb and stump pain: a randomized controlled clinical trial in landmine amputees in Cambodia

- Pain and alcohol: a comparison of two cohorts of 60 year old women and men: findings from the Good Aging in Skåne study

- Prolonged, widespread, disabling musculoskeletal pain of adolescents among referrals to the Pediatric Rheumatology Outpatient Clinic from the Päijät-Häme Hospital District in southern Finland

- Impact of the economic crisis on pain research: a bibliometric analysis of pain research publications from Ireland, Greece, and Portugal between 1997 and 2017

- Measurement of skin conductance responses to evaluate procedural pain in the perioperative setting

- Original experimental

- An observational study of pain self-management strategies and outcomes: does type of pain, age, or gender, matter?

- Fibromyalgia patients and healthy volunteers express difficulties and variability in rating experimental pain: a qualitative study

- Effect of the market withdrawal of dextropropoxyphene on use of other prescribed analgesics

- Observational study

- Winning or not losing? The impact of non-pain goal focus on attentional bias to learned pain signals

- Gabapentin and NMDA receptor antagonists interacts synergistically to alleviate allodynia in two rat models of neuropathic pain

- Offset analgesia is not affected by cold pressor induced analgesia

- Central and peripheral pain sensitization during an ultra-marathon competition

- Reduced endogenous pain inhibition in adolescent girls with chronic pain

- Evaluation of implicit associations between back posture and safety of bending and lifting in people without pain

- Assessment of CPM reliability: quantification of the within-subject reliability of 10 different protocols

- Cerebrospinal fluid cutaneous fistula after neuraxial anesthesia: an effective treatment approach

- Pain in the hand caused by a previously undescribed mechanism with possible relevance for understanding regional pain

- The response to radiofrequency neurotomy of medial branches including a bipolar system for thoracic facet joints

- Letter to the Editor

- Diagnosis of carpal tunnel syndrome – implications for therapy

- Reply to the Letter to the Editor by Ly-Pen and Andréu

- Letter to the Editor regarding “CT guided neurolytic blockade of the coeliac plexus in patients with advanced and intractably painful pancreatic cancer”

- Reply to comments from Ulf Kongsgaard to our study

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial comment

- Support for mirror therapy for phantom and stump pain in landmine-injured patients

- Lifting with straight legs and bent spine is not bad for your back

- Bipolar radiofrequency neurotomy for spinal pain – a promising technique but still some steps to go

- Topical review

- Prevalence, localization, perception and management of pain in dance: an overview

- Clinical pain research

- Pain assessment in native and non-native language: difficulties in reporting the affective dimensions of pain

- Colored body images reveal the perceived intensity and distribution of pain in women with breast cancer treated with adjuvant taxanes: a prospective multi-method study of pain experiences

- Physiotherapy pain curricula in Finland: a faculty survey

- Mirror therapy for phantom limb and stump pain: a randomized controlled clinical trial in landmine amputees in Cambodia

- Pain and alcohol: a comparison of two cohorts of 60 year old women and men: findings from the Good Aging in Skåne study

- Prolonged, widespread, disabling musculoskeletal pain of adolescents among referrals to the Pediatric Rheumatology Outpatient Clinic from the Päijät-Häme Hospital District in southern Finland

- Impact of the economic crisis on pain research: a bibliometric analysis of pain research publications from Ireland, Greece, and Portugal between 1997 and 2017

- Measurement of skin conductance responses to evaluate procedural pain in the perioperative setting

- Original experimental

- An observational study of pain self-management strategies and outcomes: does type of pain, age, or gender, matter?

- Fibromyalgia patients and healthy volunteers express difficulties and variability in rating experimental pain: a qualitative study

- Effect of the market withdrawal of dextropropoxyphene on use of other prescribed analgesics

- Observational study

- Winning or not losing? The impact of non-pain goal focus on attentional bias to learned pain signals

- Gabapentin and NMDA receptor antagonists interacts synergistically to alleviate allodynia in two rat models of neuropathic pain

- Offset analgesia is not affected by cold pressor induced analgesia

- Central and peripheral pain sensitization during an ultra-marathon competition

- Reduced endogenous pain inhibition in adolescent girls with chronic pain

- Evaluation of implicit associations between back posture and safety of bending and lifting in people without pain

- Assessment of CPM reliability: quantification of the within-subject reliability of 10 different protocols

- Cerebrospinal fluid cutaneous fistula after neuraxial anesthesia: an effective treatment approach

- Pain in the hand caused by a previously undescribed mechanism with possible relevance for understanding regional pain

- The response to radiofrequency neurotomy of medial branches including a bipolar system for thoracic facet joints

- Letter to the Editor

- Diagnosis of carpal tunnel syndrome – implications for therapy

- Reply to the Letter to the Editor by Ly-Pen and Andréu

- Letter to the Editor regarding “CT guided neurolytic blockade of the coeliac plexus in patients with advanced and intractably painful pancreatic cancer”

- Reply to comments from Ulf Kongsgaard to our study