Prolonged, widespread, disabling musculoskeletal pain of adolescents among referrals to the Pediatric Rheumatology Outpatient Clinic from the Päijät-Häme Hospital District in southern Finland

-

Heini Pohjankoski

, Maiju Hietanen

Abstract

Background and aims

Musculoskeletal pain among adolescents is a problem for the patients and their families and has economic consequences for society. The aim of this study is to determine the incidence of prolonged disabling musculoskeletal pain of adolescents among referrals to a pediatric rheumatology outpatient clinic and describe the patient material. The second aim is to find proper screening tools which identifies patients with a risk of pain chronification and to test whether our patients fit the Pediatric Pain Screening Tool (PPST) stratification according to Simons et al.

Methods

We selected adolescent patients with disabling, prolonged, musculoskeletal pain and calculated the incidence. Furthermore, after the patient collection, we adjusted our pain patients to PPST.

Results

The incidence of prolonged musculoskeletal pain patients at our clinic was 42/100,000 patient years (pyrs) (age 13–18; 95% CI: 29–60) during years 2010–2015. A nine-item screening tool by Simons et al. proves to be valid for our patient group and helps to identify those patients who need early, prompt treatment. The functional risk stratification by Simons et al. correlates with our patients’ functional disability.

Conclusions and implications

In order to prevent disability and to target intervention, it is necessary to have proper and rapid screening tools to find the appropriate patients in time.

1 Introduction

The epidemiology of prolonged non-inflammatory widespread pain varies by age, determination and country among adolescent populations [1], [2], [3], [4], [5], [6], [7]. In southern Finland the prevalence of widespread pain varies from 3% to 7.5% [7], [8], whereas in Norway, musculoskeletal pain in three or more locations was reported by 8.5% of adolescents aged 13–18 years [4]. Although among 18-year-olds in European countries and Israel, young people report that chronic pain affect their social and working lives, very few were managed by pain specialists [1].

All in all, the prevalence of musculoskeletal pain among adolescents varies according to different studies from 4% to 40%, multiple pains ranging from 4% to 49%. The pain prevalence rates for patients were higher among girls and usually increased with age [6].

Pediatric rheumatologists review a large number of patients with a wide variety of causes of musculoskeletal pain [9]. In USA, musculoskeletal pain was the most common reason for 226 out of 414 children (55%) referred to pediatric rheumatologist for over 3 years [10].

The economic impact of prolonged pain is considerably high. The financial burden of adolescent chronic pain on the UK economy for 1 year, 2005, was calculated to be £3,840 million. The mean cost is approximately £8,000 per year per adolescent and their family, including direct and indirect costs, the variation being large from £200 to over £40,000 per year. The costs were higher for patients with non-inflammatory pain than for those with inflammatory pain [11].

It is important to identify those patients who need treatment. A nine-item screening tool, the Pediatric Pain Screening Tool (PPST), identifying prognostic factors associated with disabling prolonged pain, was introduced by Simons et al. [12]. This screening tool includes nine items divided into two subscales: physical and psychosocial subscale. These items measure functional disability, pain catastrophizing, fear of pain, anxiety, and depressive symptoms. Patients were classified into low-, medium-, or high-risk groups. According to Simons et al. patients with total score 0–2 are low risk patients and patients with a total score of ≥3 are at medium- or high-risk. Of these, patients that scored 0–2 in the psychosocial subscale were medium-risk-patients and ≥3 in the psychosocial subscale were classified as high-risk patients.

At the 4-month follow-up, the PPST was valid and facilitated risk stratification to identify patients who need effective pain treatment [12].

Chronic idiopathic musculoskeletal adolescent pain, especially in three or more sites, has been reported to have a major impact on several areas of daily living [4]. Hoftun et al. defined the subjective disability index by: difficulties in sitting during a school lesson, attending daily activities during leisure time, sleeping difficulties, problems walking more than 1 km, and problems during a physical exercise class. These were assessed to count the subjective disability index. This index was higher in girls and increased with the frequency of pain and the number of pain locations [4].

The aim of the present study was to determine the incidence of prolonged, disabling, non-inflammatory, musculoskeletal pain from the referrals from the Päijät-Häme Hospital District to the Pediatric Rheumatology Outpatient Clinic of the Päijät-Häme Central Hospital, Lahti, and to describe the patient material. Patients with generalized, prolonged, musculoskeletal pain who had daily problems regarding various areas of life were the target of our search for rehabilitation of patients.

Additionally, our purpose was to find factors that indicate the need of targeted and specialized pain treatment. We aimed to test whether our patients fit the PPST risk group stratification by Simons et al. and whether our patients’ functional disability correlates with Simon’s risk stratification.

2 Patients and methods

This study took place in the Päijät-Häme Hospital District in southern Finland. The district consists of both rural and urban areas, with approximately 220,000 inhabitants. All patients were recruited from referrals to the Pediatric Rheumatology Outpatient Clinic at Päijät-Häme Central Hospital.

From 2010 to 2015, we received 508 patients to our pediatric rheumatology clinic. Out of all referrals between 2010 and 2015, patients who were diagnosed with juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA), connective systemic rheumatic diseases, transient synovitis of the hip, growing pains or another disease explaining the prolonged pain were excluded from the study, thus leaving the 508 patients. The patients, among the 508 referrals, were aged from 1 year to 17 years.

First, the patients and their accompanying parent/parents were interviewed by a nurse specialized in pediatric rheumatology.

The patients were then examined by a pediatric rheumatologist together with a specialized physical therapist. In addition, all patients had a personal physical therapist’s consultation.

Chronic illnesses were excluded by means of laboratory tests, with the following assays analyzed from all patients: erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, complete blood count, creatinine, alanine aminotransferase (ALT), antinuclear antibodies, rheumatoid factor, citrullinated peptide antibodies, anti-tissue transglutaminase IgA antibodies, IgA to exclude its deficiency, HLA-B27, Saccharomyces cerevisiae antibodies (ASCA) to exclude Crohn’s disease, and borrelia burgdorferi antibodies.

Between September 2010 and October 2015, 34 out of the 508 patients were selected by a multiprofessional team to participate in a prolonged pain rehabilitation program in Lahti. The team included two pediatric rheumatologists, a clinical psychologist, a physical therapist, and a nurse. The inclusion criteria for the intensive outpatient pain program for adolescent prolonged multisite musculoskeletal pain were: prolonged musculoskeletal pain lasting over 3 months, school absence, sleep or mood disturbances, problems with physical exercise, or difficulties with daily activities during leisure time. All other 474 patients had minor problems of pain and did not have daily problems because of pain.

One patient was excluded because he was only 10 years old and was too young for rehabilitation. His treatment continued normally at the outpatient pediatric rheumatology clinic. One patient, a boy of 16 years with CRPS, refused to attend the rehabilitation thus the study group being 32 patients.

In this group of 32 patients, with pediatric rheumatologist’s examination duration of pain, laboratory tests and by contrast enhancement magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), other chronic illnesses were excluded. Twenty-seven out of 32 patients (84%) were examined by MRI to exclude chronic arthritis or other illnesses and to confirm idiopathic musculoskeletal pain with no other cause. All MRI examinations of one most painful joint were normal. We did not use whole body MRI scan.

Our target was to indentify patients with prolonged, non-inflammatory, musculoskeletal pain with disabling various problems regarding daily life.

The patient and accompanying parent received both written and oral information about the study. The participants gave their written informed consent.

This study was approved by the Ethical Commitee of Päijät-Häme Central Hospital.

2.1 Measures

2.1.1 Functional disability

The Childhood Health Assessment Questionnaire (CHAQ) was used to measure the children’s functional status. The scale assesses performance in eight areas, but in this study only the total score was used. The scores range from zero to three, the higher scores indicating greater functional impairment. The CHAQ has been reported to be reliable and sensitive, and it has been validated in a Finnish sample and includes general and pain visual analog scale (VAS) ratings [13].

2.1.2 The structured pain questionnaire (SPQ)

A structured pain questionnaire with a five-level frequency classification of pain over the previous 3 months was used (seldom or never, once a month, once a week, more than once a week, almost daily). Each of the six pain areas (neck, upper and lower extremities, chest, upper back, and lower back) was scored from 0 to 4 with the total (frequency and area combined) score ranging from 0 to 24. The body area concerned was marked in a picture beside the question to help the child recognize the named area. The internal consistency of the scale was good. The questionnaire properly describes the frequency of pain and multisite pain [7], [14].

2.1.3 Daily functional ability

Patients filled out a questionnaire to express their views about their daily functionality. They were asked about the physical and psychosocial aspects typically related to prolonged pain and days of school absence because of pain. The physical items were difficulties walking over 1 km, problems sitting still during a school lesson, difficulties during a physical exercise class, and problems performing daily activities during leisure time. The psychosocial items were: “Moving makes my pain worse”, “I am nervous and I have anxiety”, and “Nervousness makes my pain worse” [7], [14].

2.1.4 Sleeping questionnaire

The patients filled out a sleeping questionnaire consisting of six items concerning sleep: (1) tiredness in the morning after a good night’s sleep, (2) difficulties falling asleep, (3) sleeping during the day, (4) nightmares, (5) tiredness because of not being able to sleep during the night, and (6) difficulties staying asleep through the night. The items were scored from zero to six [14].

2.1.5 Depression/mood

The Finnish version of the Child Depression Inventory (CDI) was used to measure the depression/mood disturbances of the patients. This version consists of 26 items assessing a variety of depression symptoms. The score for each item varies from zero to two, and the total score thus varies from 0 to 52. Higher values indicate increasingly severe depression [15].

In a personal physical therapist’s consultation patient’s physical condition was evaluated with detailed muscle strength tests and a six-minute walking test.

2.1.6 Six-minute walking test

A six-minute Timed Walk (6MTW) test was used, which recorded the adolescents’ walking distance in meters over a 6-min interval to establish the sub-maximal performance. The test protocol was developed by Guyatt et al. [16], [17]. The 6MTW measures the distance the patient is able to walk quickly on a flat, hard surface. A pilot study showed that a 15- or 30-m walking track of the 6-min walk test was a repeatable and reliable maximal aerobic power evaluation method in healthy adults of working age. A walking test has been proven to have a moderate correlation with maximal oxygen consumption [18], [19].

2.1.7 Muscle tests

The test measures muscular strength, motion control, elasticity tests, pulse, oxygen saturation and peak expiratory flow (PEF) values. Patient’s body mass index (BMI) was also calculated. An interview form is used to seek information from the various aspects of life. The interview forms are further used in monitoring the effectiveness of rehabilitation and enhancing motivation in rehabilitation. Dynamic and static muscle function and motion control tests are quick to make, their results are clear to evaluate and delicate measurements to show changes in muscle activity and control. Based on the results of testing, the adolescent can find the right means to influence their health and physical condition [20], [21]. Personal training plans are made based on the results.

2.1.8 PPST stratification according to Simons et al.

The PPST items according to Simons are as follows:

Physical subscale (four items): “My pain is in more than one body part”; “I can only walk a short distance because of my pain”; “It is difficult for me to be at school all day”; and “It is difficult for me to fall asleep and stay asleep”.

Psychosocial subscale (five items): “It is really not safe for me to be physically active”; “I worry about my pain a lot”; “I feel that my pain is terrible and it’s never going to get any better”; “In general, I don’t have as much fun as I used to”; and “Overall, how much has pain been a problem in the last 2 weeks?”.

All items counts for 0 or 1 point, thus maximum score being 9 points. Patients with total score: 0–2 low risk, patients with total score over 3 were divided into two groups according to psychosocial points: psychosocial score 0–2: medium risk, psychosocial score over 3: high risk.

After we have collected the patient material, we fit our patients into Simons et al. PPST stratification subscale by using mainly our questionnaire: daily functional ability.

2.2 Statistical methods

Descriptive statistics include means and SDs for continuous variables and numbers and percentages for categorical variables. Statistical comparison between the groups was performed by t-test, permutation test, Mann-Whitney with exact statistics, χ2-test, or Fisher-Freeman-Halton test when appropriate. Widespread musculoskeletal pain incidence rates (per 100,000 person years) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated assuming a Poisson distribution. Mean population sizes for the calculation of incidence rates were obtained from Statistics Finland.

3 Results

3.1 Incidence

Out of the overall 508 referrals, 32 consecutive patients were included to participate in an intensive outpatient pain program for adolescent prolonged, multisite musculoskeletal pain. The inclusion criteria were prolonged musculoskeletal pain lasting over 3 months, school absence, sleep or mood disturbances, problems with physical exercise, or difficulties with daily activities during leisure time.

One of our patients had Marfan syndrome, and four had Ehler-Danlos hypermobility-type-syndrome, and all of these diagnoses were confirmed by a physician specialist in genetics.

During years 2010–2015 the incidence of prolonged, multisite musculoskeletal pain was 42/100,000 patient years (pyrs) (age 13–18; 95% CI 29–60), approximately seven patients in a year. The median duration of pain was 24 months (Interquartile range 38.5).

The incidence of boys was 16 (6–35) and girls 69 (45–101), age at baseline 14.4 (13–17).

According to Simons et al. 19 patients were classified as high-risk (total PPST score ≥3; psychosocial subscale score ≥3), and 13 were classified as medium-risk (total PPST score ≥3; psychosocial subscale score 0–2). None were in the low-risk group (Table 1).

According to Simons et al. we divided our 32 patients into two groups: the medium-risk group (n=13) fulfilling the Simons criteria 3–6 and the high-risk group (n=19) fulfilling Simons criteria 7–9.

| All | PPST | p-Valuea | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n=32 | 3–6 n=13 |

7–9 n=19 |

||

| Girls, n(%) | 26 (81) | 10 (77) | 16 (84) | 0.67 |

| Age, mean (SD) | 14.4 (1.3) | 14.2 (1.1) | 14.6 (1.3) | 0.30 |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 23.3 (5.9) | 22.3 (6.6) | 24.1 (5.4) | 0.41 |

| Duration of pain, mo., median (IQR) | 24 (15, 72) | 24 (18, 36) | 24 (15, 72) | 0.32 |

| CHAQ, mean (SD) | 0.25 (0.33) | 0.09 (0.21) | 0.37 (0.36) | 0.017 |

| Pain, VAS, mean (SD) | 42 (25) | 31 (23) | 50 (23) | 0.031 |

| General, VAS, mean (SD) | 28 (19) | 20 (18) | 33 (19) | 0.047 |

| Structured pain questionnaire (SPQ) score | 12.5 (6.1) | 7.5 (4.0) | 15.9 (4.9) | <0.001 |

| Musculoskeletal pain1, n(%) | ||||

| Neck or shoulder | 25 (78) | 8 (62) | 17 (89) | 0.091 |

| Upper ext. | 20 (62) | 5 (38) | 15 (79) | 0.030 |

| Chest | 10 (31) | 2 (15) | 8 (42) | 0.14 |

| Upper back | 18 (56) | 4 (31) | 14 (74) | 0.029 |

| Lower back | 22 (69) | 7 (54) | 15 (79) | 0.24 |

| Lower ext. | 28 (87) | 9 (69) | 19 (100) | 0.020 |

| Three or more locations | 25 (78) | 8 (62) | 17 (89) | 0.091 |

| Headache/migraine, n(%) | 22 (69) | 7 (54) | 15 (79) | 0.24 |

| Abdominal pain, n(%) | 10 (31) | 2 (15) | 8 (42) | 0.14 |

| Walking test, m/6 min, mean (SD) | 577 (58) | 575 (58) | 578 (59) | 0.93 |

| CDI, mean (SD) | 10.2 (8.5) | 6.9 (7.3) | 12.5 (8.8) | 0.039 |

| CDI 13-, n(%) | 9 (28) | 1 (8) | 8 (42) | 0.033 |

| Smoking | 7 (22) | 3 (23) | 4 (21) | 0.89 |

The differences between the medium-risk and high-risk group, were found in Child Health Assessment Questionnaire (CHAQ), pain visual analogue scale (pain VAS), general visual analogue scale (VAS), and CDI, meaning that the high-risk group had more functional disability, worse general wellbeing, higher pain and depressive scores. The Simons criteria were strongly associated with the frequency of pain, multisite pain (SPQS), and functional disability (CHAQ). Seven patients (22%) were smokers, and 26 (81%) were girls (Table 1).

Two out of the 32 patients did not attend school at all because of pain, 17 had school absences, and 13 attended school regularly.

All patients had pain in more than one body part. Twenty-five (78%) patients had difficulties sitting still during a school lesson, and 16 (50%) had sleep disturbances.

Twenty-five (78%) patients’ pain was increased if they were physically active, 24 (75%) patients worried about pain a lot, 21 (66%) thought that their pain was horrible, 29 (90%) did not enjoy life, and all patients said that pain was a problem for them (Fig. 1).

![Fig. 1:

Patient classification according to Simons et al. [12]](/document/doi/10.1515/sjpain-2018-0057/asset/graphic/j_sjpain-2018-0057_fig_003.jpg)

Patient classification according to Simons et al. [12]

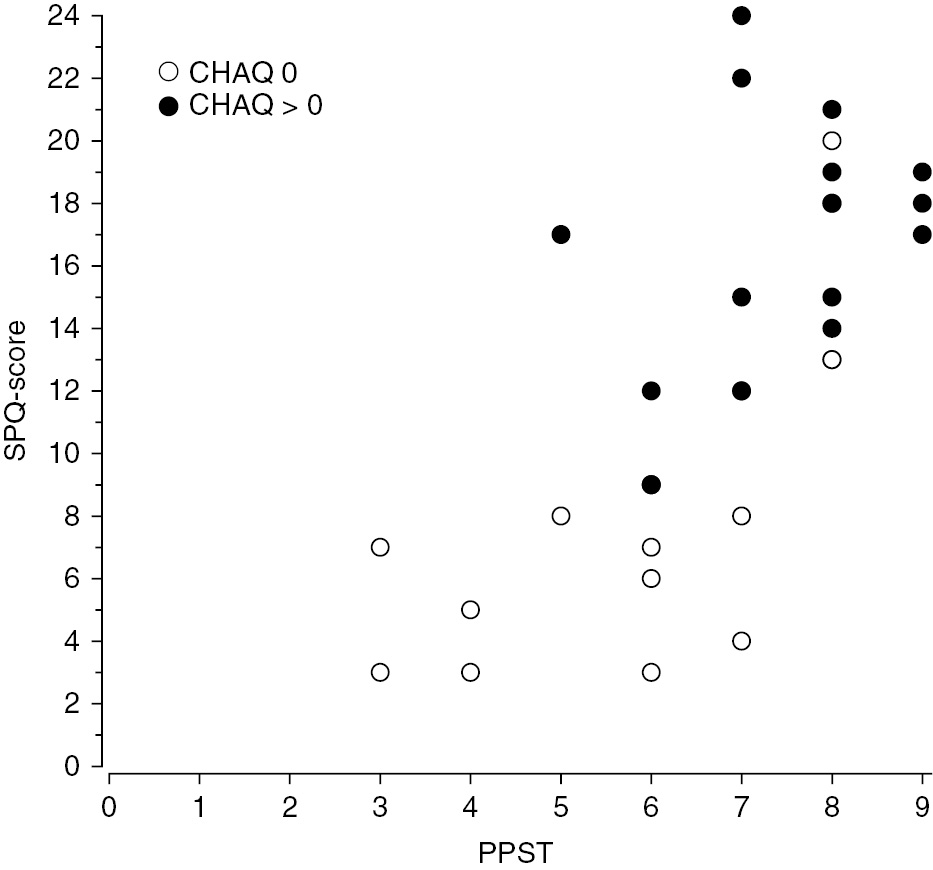

Figure 2 shows that the Simons criteria and the structured pain questionnaire score describe functional disability well according to CHAQ (correlation 0.72 (0.50–0.86).

PPST and SPQ functional ability according to CHAQ. Correlation 0.72 (0.50–0.86). Blank circles CHAQ 0, black circles CHAQ>0.

Table 2: A patient according only to psychosocial criteria was in the high-risk group if more than three psychosocial criteria were met. Of our patients, 28 (88%) were in the high-risk group, three patients were in the medium-risk group, and none were in the low-risk group.

Psychosocial criteria among our patients according to PPST.

| Psychosocial criteria | Frequency | Percent | Cumulative |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 3.13 | 3.13 |

| 2 | 3 | 9.38 | 12.50 |

| 3 | 5 | 15.63 | 28.13 |

| 4 | 6 | 18.76 | 46.88 |

| 5 | 17 | 53.13 | 100.00 |

| Total | 32 | 100.00 |

-

High risk patients: 28 88% (95% CI: 71–96).

One patient fulfilled only one psychosocial criteria, while two patients met three, three patients fulfilled five, four patients met six, and 17 patients fulfilled all five psychosocial criteria.

There were only four patients whose psychosocial score was only 0–2 (Table 2).

4 Discussion

The incidence of prolonged pain among patients referred to a pediatric rheumatology clinic was 42/100,000 pyrs. As a comparison in USA, pediatric rheumatologists reviewed 414 children and 111 (27%) had musculoskeletal pain as an isolated complaint. Only one of them (0.2%) had chronic inflammatory disease [10]. In Canada the proportion of pain syndromes was 15% among diagnoses made in pediatric rheumatology clinic [22]. On the other hand, our patients had severe pain associated disability, meaning that our incidence, which was low compared to those figures from USA and CANADA, is not wholly comparable with studies mentioned above. We did not use the diagnosis fibromyalgia, although it is probable that most of our patients would have fulfilled the criteria for fibromyalgia.

Most of our patients, 26 (81%), were girls as usually in previous studies [6]. Our patients suffered from prolonged pain, and the median duration of symptoms ranged from 15 to 72 months, with a median of 24 months. In the studies by both Sleed et al. [11] and Logan et al. [23], the duration of pain was also approximately 2 years [11], [23]. Our patients had problems with school attendance (78%), which, according to Logan et al. [23], may have a longstanding effect on their lives, and this issue needs to be addressed.

In the current study we did not measure parental factors, which is a limitation in the study. However, according to Hoftun et al. [24] parental chronic pain has been found to be associated with nonspecific pain and especially with multisite pain, in adolescents and young adults, which implies that pain is also a family matter [24]. The burden on the lives of families in attempting to cope with a child with prolonged pain is significant. Adolescents suffering from prolonged pain have various symptoms – sleeping disturbances, problems with school attendance, mood problems/depression, and difficulties in their social life. Pain has a negative impact on the physical and psychosocial well-being of the patients and their families [25].

In a Finnish study, chronic pain showed a strong association with disability retirement [26]. In order to fully understand the pain syndromes in childhood, as well as the risk factors that predict pain in adulthood, we need more longitudinal studies. It is vitally important to target the treatment and rehabilitation as early as possible with preventive measures [27].

The economic burden due to prolonged pain among adolescents is a problem for the patients, their families, and for the economy as a whole. In the US, pain is a considerable problem, with an economically estimated 1.7 million children costing $19.5 billion dollars annually [12]. The costs on the UK economy for 1 year, 2005, were calculated to be £3,840 million. An economic burden of that magnitude is alarming. If these patients are not provided with a treatment that is well-targeted and timed correctly, their personal suffering and economic impact is going to escalate in adulthood [11].

Among our patients, 25 (78%) had pain in three or more locations. Pain-VAS was used as a measure of pain intensity. In the whole sample the pain intensity was 42, but as the patients were stratified into the medium (VAS 31) – and high risk (VAS 50) – groups by PPST there were a significant difference between the groups with the high-risk group having a higher level of pain intensity.

SPQ describes pain frequency and pain location combined. Ståhl et al. studied neck pain and found that the frequency of pain reflects well the intensity of pain [28]. Moreover, multisite pain and the frequency of pain have been shown to associate with a higher disability index and predict pain persistence [4]. In the current study, PPST and SPQ showed positive correlation with functional disability reported by CHAQ.

Simons et al. published a nine-item screening tool to identify factors associated with poor outcome in adolescents with prolonged pain. The screening tool helps to identify at an early stage those patients who need prompt rehabilitation. That tool was proven to be valid in our patient group. It is important to treat patients early because brain imaging shows that brain alterations occur in patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain [29]. In child patients with CRPS these brain changes may be reversible when treated adequately. This emphasizes the possibility of recovery [30].

In a Finnish School Health Promotion Study (SHP) 2015 about 5% of adolescent aged 14–17 attending comprehensive and secondary school smoked. However, the proportion of smokers was higher (10–27%) among those who attended vocational school [31]. In our study, all smokers attended vocational school, and the proportion (22%) was rather similar. Smoking is a risk factor for musculoskeletal pain persistence among girls aged 16 and 18 [32].

The number of our patients was rather small, with only 32 included in the study, and hence the results are preliminary, and must be interpreted cautiously.

Conclusions: The incidence of disabling pain patients in our study was low. Screening tools proved to be valid in our patient material.

Implications: Patients with prolonged musculoskeletal pain are often treated in pediatric rheumatology outpatient clinic. They have pain associated disability covering various areas of life. Methods which provides us sensitive methods to recognize patients with a risk for pain chronification are essential. That should be done already earlier than in our patients, median duration of symptoms 24 months. SPQ score, Hoftun disability index and PPST stratification have been proved to be good tools to identify right patients. Patients need prompt, well-guided and effective treatment, and recognizing the right patients early on is vitally important for a better outcome.

-

Authors’ statements

-

Research funding: This study was supported by the Medical Research Fund of Päijät-Häme Central District Hospital.

-

Conflict of interest: Heini Pohjankoski has received travel and congress fees from Pfizer, AbbVie, MSD and Roche. Maiju Hietanen has received travel and congress fees from Pfizer, Abbvie, Roche and Celgene. Marja Mikkelsson has received lecture fees from Orionpharma, Medtronic, Pfizer and MSD. The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare regarding this study.

-

Informed consent: The patient and accompanying parent received both written and oral information about the study. The participants gave their written informed consent.

-

Ethical Approval: This study was approved by the Ethical Commitee of Päijät-Häme Central Hospital.

-

Author contributions

-

All authors contributed to the study design. Heini Pohjankoski, Maiju Hietanen, Leena Leppänen, Heli Vilen and Hanna Vuorimaa collected the patient material. Heini Pohjankoski, Maiju Hietanen, Hanna Vuorimaa, Leena Leppänen and Hannu Kautiainen analysed and interpreted the data. Heini Pohjankoski drafted the article and Hanna Vuorimaa and Marja Mikkelsson contributed to the revision of the manuscript. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript and made the final approval of the version to be published.

References

[1] Breivik H, Collett B, Ventafridda V, Cohen R, Gallagher D. Survey of chronic pain in Europe: prevalence, impact on daily life, and treatment. Eur J Pain 2006;10:287–333.10.1016/j.ejpain.2005.06.009Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[2] Buskila D, Ablin J. Pediatric fibromyalgia. Rheumatismo 2012;64:230–7.10.4081/reumatismo.2012.230Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[3] Buskila D. Pediatric fibromyalgia. Rheum Dis Clin North Am 2009;35:253–61.10.1016/j.rdc.2009.06.001Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[4] Hoftun GB, Romundstad PR, Zwart J, Rygg M. Chronic idiopathic pain in adolescence-high prevalence and disability: the young Hunt-study 2008. Pain 2011;152:2259–66.10.1016/j.pain.2011.05.007Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[5] King A, Wold B, Tudor-Smith C, Harel Y. The health of youth. A cross-national survey. WHO Reg Publ Eur Ser 1996;69:1–222.Suche in Google Scholar

[6] King S, Chambers CT, Huguet A, MacNevin RC, McGrath PJ, Parker L, McDonald AJ. The epidemiology of chronic pain in children and adolescents revisited: a systematic review. Pain 2011;152:2729–38.10.1016/j.pain.2011.07.016Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[7] Mikkelsson M, Salminen J, Kautiainen H. Non-specific muskuloskeletal pain in preadolescents. Prevalence and 1-year persistence. Pain 1997;73:29–35.10.1016/S0304-3959(97)00073-0Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[8] Mikkelsson M, El-Metwally A, Kautiainen H, Auvinen A, Macfarlane GJ, Salminen JJ. Onset, prognosis and risk factors of widespread pain in school children: a prospective 4-year follow-up study. Pain 2008;138:681–7.10.1016/j.pain.2008.06.005Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] Sherry DD. Pain syndromes in children. Curr Rheumatol Rep 2000;2:337–42.10.1007/s11926-000-0072-0Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[10] McGhee JL, Burks FN, Sheckels JL, Jarvis JN. Identifying children with chronic arthritis based of chief complaints: absence of predictive value for musculoskeletal pain as an indicator of rheumatic diseases in children. Pediatrics 2002;110:354–9.10.1542/peds.110.2.354Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] Sleed M, Eccleston C, Beecham J, Knapp M, Jordan A. The economic impact of chronic pain in adolescence: methodological considerations and preliminary costs-of-illness study. Pain 2005;119:183–90.10.1016/j.pain.2005.09.028Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[12] Simons LE, Smith A, Ibagon C, Coakley R, Logan DE, Schechter N, Borsook D, Hill JC. Pediatric Pain Screening Tool: rapid identification of risk in youth with pain complaints. Pain 2015;156:1511–18.10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000199Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[13] Pelkonen P, Ruperto N, Honkanen V, Hannula S, Savolainen A, Lahdenne P. The Finnish version of the Childhood Health Assessment Questionnaire (CHAQ) and the Child Health Questionnaire (CHQ). Clin Exp Rheumatol 2001;19(4 Suppl 23):55–9.Suche in Google Scholar

[14] Mikkelsson M, Salminen JJ, Sourander A, Kautiainen H. Contributing factors to the persistence of musculoskeletal pain in preadolescents: a prospective 1-year follow-up study. Pain 1998;77:67–72.10.1016/S0304-3959(98)00083-9Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[15] Kovacs M, Beck AT. An empirical – clinical approach toward a definition of childhood depression. In: Schulterbrandt JG, Raskin A, editors. Depression in childhood: diagnosis, treatment, and conceptual models. N.Y: Raven Press, 1977:1–25.Suche in Google Scholar

[16] Guyatt GH, Sullivan MJ, Thompson PJ, Fallen EL, Pugsley SO, Taylor DW, Berman LB. The 6-minute walk test: a new measure of exercise capacity in patients with chronic heart failure. Can Med Assoc J 1985;132:919–23.Suche in Google Scholar

[17] Enright PL. The six-minute walk test. Respir Care 2003;48: 783–5.Suche in Google Scholar

[18] ATS Committee on Proficiency Standards for Clinical Pulmonary Function Laboratories. ATS statement: guidelines for the six-minute walk test. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002;166:111–7.10.1164/ajrccm.166.1.at1102Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[19] Faggiano P, D’Aloia A, Gualeni A, Lavatelli A, Giordano A. Assessment of oxygen uptake during 6-minute walking test on patients with heart failure: preliminary experience with a portable device. American Heart 1997;134:203–6.10.1016/S0002-8703(97)70125-XSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[20] EUROFIT. European test of physical fitness. Council of Europe. Committee for the development of sport. Rome 1988.Suche in Google Scholar

[21] Suni JH, Miilunpalo SI, Asikainen TM, Laukkanen RT, Oja P, Pasanen ME, Bös K, Vuori IM. Safety and feasibility of a health-related fitness test battery for adults. Phys Ther 1998;78:134–48.10.1093/ptj/78.2.134Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[22] Malleson PN, Fung MY, Rosenberg AM. The incidence of pediatric rheumatic diseases: results from the Canadian Pediatric Rheumatology Association Disease Registry. J Rheumatol 1996;23:1981–7.Suche in Google Scholar

[23] Logan DE, Simons LE, Stein MJ, Chastain L. School impairment in adolescents with chronic pain. J Pain 2008;9:407–16.10.1016/j.jpain.2007.12.003Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[24] Hoftun GB, Romundstad PR, Rygg M. Association of parental chronic pain in the adolescent and young adult: a family linkage data from the HUNT Study. JAMA Pediatr 2013;167:61–9.10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.422Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[25] Eccleston C, Fisher E, Law E, Bartlett J, Palermo T. Centre psychological interventions for parents of children and adolescents with chronic illness. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015;CD009660.10.1002/14651858.CD009660.pub3Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[26] Saastamoinen P, Laaksonen M, Kääriä S-K, Lallukka T, Leino-Arjas P, Rahkonen O, Lahelma E. Pain and disability retirement: a prospective cohort study. Pain 2012;153:526–31.10.1016/j.pain.2011.11.005Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[27] Mäntyselkä P. Pain today – disability tomorrow. Pain 2012;153:507–8.10.1016/j.pain.2011.12.002Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[28] Ståhl M, Mikkelsson M, Kautiainen H, Häkkinen A, Ylinen J, Salminen JJ. Neck pain in adolescence. A 4-year follow-up of pain-free preadolescents. Pain 2004;110:427–31.10.1016/j.pain.2004.04.025Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[29] Kregel J, Coppieters I, DePauw R, Malfliet A, Danneels L, Nijs J, Cagnie B, Meeus M. Does conservative treatment change the brain in patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain? A systematic review. Pain Phys 2017;20:139–54.10.36076/ppj.2017.154Suche in Google Scholar

[30] Erpelding N, Simons L, Lebel A, Serrano P, Pielech M, Prabhu S, Becerra L, Borsook D. Rapid treatment-induced brain changes in pediatric CRPS. Brain Struct Funct 2016;221:1095–111.10.1007/s00429-014-0957-8Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[31] School Health Promotion Study 2015 by National Institute of Health and Welfare: https://www.thl.fi/fi/web/thlfi-en/research-and-expertwork/population-studies/school-health-promotion-study. Accessed: October 2015.Suche in Google Scholar

[32] Paananen MV, Taimela SP, Auvinen JP, Tammelin TH, Kantomaa MT, Ebeling HE, Taanila AM, Zitting PJ, Karppinen JI. Risk factors for persistence of multiple musculoskeletal pain in adolescence: a two-year follow-up study. Eur J Pain 2010;14:1026–32.10.1016/j.ejpain.2010.03.011Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

©2018 Scandinavian Association for the Study of Pain. Published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston. All rights reserved.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Editorial comment

- Support for mirror therapy for phantom and stump pain in landmine-injured patients

- Lifting with straight legs and bent spine is not bad for your back

- Bipolar radiofrequency neurotomy for spinal pain – a promising technique but still some steps to go

- Topical review

- Prevalence, localization, perception and management of pain in dance: an overview

- Clinical pain research

- Pain assessment in native and non-native language: difficulties in reporting the affective dimensions of pain

- Colored body images reveal the perceived intensity and distribution of pain in women with breast cancer treated with adjuvant taxanes: a prospective multi-method study of pain experiences

- Physiotherapy pain curricula in Finland: a faculty survey

- Mirror therapy for phantom limb and stump pain: a randomized controlled clinical trial in landmine amputees in Cambodia

- Pain and alcohol: a comparison of two cohorts of 60 year old women and men: findings from the Good Aging in Skåne study

- Prolonged, widespread, disabling musculoskeletal pain of adolescents among referrals to the Pediatric Rheumatology Outpatient Clinic from the Päijät-Häme Hospital District in southern Finland

- Impact of the economic crisis on pain research: a bibliometric analysis of pain research publications from Ireland, Greece, and Portugal between 1997 and 2017

- Measurement of skin conductance responses to evaluate procedural pain in the perioperative setting

- Original experimental

- An observational study of pain self-management strategies and outcomes: does type of pain, age, or gender, matter?

- Fibromyalgia patients and healthy volunteers express difficulties and variability in rating experimental pain: a qualitative study

- Effect of the market withdrawal of dextropropoxyphene on use of other prescribed analgesics

- Observational study

- Winning or not losing? The impact of non-pain goal focus on attentional bias to learned pain signals

- Gabapentin and NMDA receptor antagonists interacts synergistically to alleviate allodynia in two rat models of neuropathic pain

- Offset analgesia is not affected by cold pressor induced analgesia

- Central and peripheral pain sensitization during an ultra-marathon competition

- Reduced endogenous pain inhibition in adolescent girls with chronic pain

- Evaluation of implicit associations between back posture and safety of bending and lifting in people without pain

- Assessment of CPM reliability: quantification of the within-subject reliability of 10 different protocols

- Cerebrospinal fluid cutaneous fistula after neuraxial anesthesia: an effective treatment approach

- Pain in the hand caused by a previously undescribed mechanism with possible relevance for understanding regional pain

- The response to radiofrequency neurotomy of medial branches including a bipolar system for thoracic facet joints

- Letter to the Editor

- Diagnosis of carpal tunnel syndrome – implications for therapy

- Reply to the Letter to the Editor by Ly-Pen and Andréu

- Letter to the Editor regarding “CT guided neurolytic blockade of the coeliac plexus in patients with advanced and intractably painful pancreatic cancer”

- Reply to comments from Ulf Kongsgaard to our study

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Editorial comment

- Support for mirror therapy for phantom and stump pain in landmine-injured patients

- Lifting with straight legs and bent spine is not bad for your back

- Bipolar radiofrequency neurotomy for spinal pain – a promising technique but still some steps to go

- Topical review

- Prevalence, localization, perception and management of pain in dance: an overview

- Clinical pain research

- Pain assessment in native and non-native language: difficulties in reporting the affective dimensions of pain

- Colored body images reveal the perceived intensity and distribution of pain in women with breast cancer treated with adjuvant taxanes: a prospective multi-method study of pain experiences

- Physiotherapy pain curricula in Finland: a faculty survey

- Mirror therapy for phantom limb and stump pain: a randomized controlled clinical trial in landmine amputees in Cambodia

- Pain and alcohol: a comparison of two cohorts of 60 year old women and men: findings from the Good Aging in Skåne study

- Prolonged, widespread, disabling musculoskeletal pain of adolescents among referrals to the Pediatric Rheumatology Outpatient Clinic from the Päijät-Häme Hospital District in southern Finland

- Impact of the economic crisis on pain research: a bibliometric analysis of pain research publications from Ireland, Greece, and Portugal between 1997 and 2017

- Measurement of skin conductance responses to evaluate procedural pain in the perioperative setting

- Original experimental

- An observational study of pain self-management strategies and outcomes: does type of pain, age, or gender, matter?

- Fibromyalgia patients and healthy volunteers express difficulties and variability in rating experimental pain: a qualitative study

- Effect of the market withdrawal of dextropropoxyphene on use of other prescribed analgesics

- Observational study

- Winning or not losing? The impact of non-pain goal focus on attentional bias to learned pain signals

- Gabapentin and NMDA receptor antagonists interacts synergistically to alleviate allodynia in two rat models of neuropathic pain

- Offset analgesia is not affected by cold pressor induced analgesia

- Central and peripheral pain sensitization during an ultra-marathon competition

- Reduced endogenous pain inhibition in adolescent girls with chronic pain

- Evaluation of implicit associations between back posture and safety of bending and lifting in people without pain

- Assessment of CPM reliability: quantification of the within-subject reliability of 10 different protocols

- Cerebrospinal fluid cutaneous fistula after neuraxial anesthesia: an effective treatment approach

- Pain in the hand caused by a previously undescribed mechanism with possible relevance for understanding regional pain

- The response to radiofrequency neurotomy of medial branches including a bipolar system for thoracic facet joints

- Letter to the Editor

- Diagnosis of carpal tunnel syndrome – implications for therapy

- Reply to the Letter to the Editor by Ly-Pen and Andréu

- Letter to the Editor regarding “CT guided neurolytic blockade of the coeliac plexus in patients with advanced and intractably painful pancreatic cancer”

- Reply to comments from Ulf Kongsgaard to our study