Colored body images reveal the perceived intensity and distribution of pain in women with breast cancer treated with adjuvant taxanes: a prospective multi-method study of pain experiences

-

Susanne Hellerstedt-Börjesson

, Karin Nordin

Abstract

Background and aims

Breast cancer is the most prevalent adult cancer worldwide. A broader use of screening for early detection and adjuvant systemic therapy with chemotherapy has resulted in improved survival rates. Taxane-containing chemotherapy is one of the cornerstones of the treatment. However, taxane-containing chemotherapy may result in acute chemotherapy-induced nociceptive and neuropathic pain. Since this pain may be an additional burden for the patient both during and after taxane chemotherapy, it is important to rapidly discover and treat it. There is yet no gold standard for assessing taxane-induced pain. In the clinic, applying multiple methods for collecting information on pain may better describe the patients’ pain experiences. The aim was to document the pain during and after taxane through the contribution of different methods for collecting information on taxane-induced pain. Fifty-three women scheduled for adjuvant sequential chemotherapy at doses of ≥75 mg/m2 of docetaxel and epirubicin were enrolled in the study.

Methods

Prospective pain assessments were done on a visual analog scale (VAS) before and during each cycle of treatment for about 5 months, and using the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire’s (EORTC-QLQ-C30) two pain questions at baseline, 3 months, and 12 months. Participants scoring pain on the VAS >30 and undergoing an interview also colored their pain on a body image during treatment and at 12 months.

Results

Surprisingly widespread, intense pain was detected using a multi-method approach. The colored body image showed pain being perceived on 51% of the body surface area during treatment, and on 18% 12 months after inclusion. In general, the pain started and peaked in intensity after the first cycle of taxane. After Cycle 3, most women reported an increase in pain on the VAS. Some women continued to report some pain even during the epirubicin cycles. The VAS scores dropped after the last chemotherapy cycle, but not to the baseline level. At baseline, 3 months and 12 months after inclusion, the women who estimated VAS >30 reported higher levels of pain on the pain questions of the EORTC-QLQ-C30.

Conclusions

This study contributes information on how different pain assessment tools offer different information in the assessment of pain. The colored body image brings another dimension to pain diagnostics, providing additional information on the involved body areas and the pain intensities as experienced by the women. A multi-method approach to assessing pain offers many advantages. The timing of the assessment is important to properly assess pain.

Implications

Pain relief needs to be included in the chemotherapy treatment, with individual assessment and treatment of pain, in the same way as is done in chemotherapy-triggered nausea. There is a time window whereby the risk of pain development is at its highest within 24–48 h after receiving taxane chemotherapy. Proper attention to pain evaluation and treatment should be in focus during this time window.

1 Introduction

Breast cancer is currently the most prevalent adult cancer worldwide [1]. A broader use of screening for earlier detection, multi-disciplinary care, and adjuvant systemic therapy for patients with early breast cancer have resulted in improved survival rates [2]. Taxane-containing chemotherapy is one of the cornerstones of adjuvant breast cancer treatment. However, it may result in acute chemotherapy-induced nociceptive and neuropathic pain, experienced as muscle and joint pain, painful paresthesias, tingling, numbness, dysesthesia and distal muscle weakness [3], [4], [5]. The pathophysiology of chemotherapy-induced pain is not completely understood [6], [7] and no convincing explanations for the pain syndrome arising from joints and muscles are available [8]. Furthermore, to date no validated treatment options have been identified for dealing with taxane-induced pain [9]. Chemotherapy-induced neuropathic pain persisting for several years has been described in 30–43% of patients. Additionally, older patients have been reported to be even more sensitive and thus at higher risk of developing chemotherapy-induced pain [5], [10]. Taxane toxicity such as neuropathy and pain should be valuated all the more since the toxicity are not correlated to the treatment outcome [3]. Nevertheless pain is known to interact with other symptoms and influence the health-related quality of life (HRQoL) [11], both during and after completed treatment. The effects of pain on daily life are considerable, both short and long term [12], [13]. Women with breast cancer treated with adjuvant taxanes could be served well by receiving better information about possible side effects such as polyneuropathy and long-term pain during and after taxane treatment. Improved symptomatic treatment of pain as well as information on and prescription of pre-emptive analgesia treatment, could be highly effective in avoiding unnecessary pain and anxiety.

The visual analog scale (VAS) is a commonly used method for reporting pain and has been found helpful in monitoring chemotherapy-induced pain [14]. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire (EORTC-QLQ-C30) [15] is a common tool for evaluating HRQoL in patients with cancer, and includes two questions assessing pain. Unfortunately, the reporting of pain in clinical trials is often incomplete, with many studies lacking descriptions of how the assessments were performed [6], [16]. Pain is a symptom that may be difficult to assess reliably in the clinical practice [17]. Even though the VAS is a method that can reasonably communicate the intensity of the subjective pain experience [18], it neither communicates the localization nor the distribution of the perceived pain. One way to overcome these shortages could be to use a supplemental pain chart, such as a colored body image [19]. This is a method for semi-quantitatively assessing the perceived distribution and intensity of the pain. Combining different methods for collecting information about pain may add important information in order to further describe the individual pain experience [20].

The aim of the present study was to document the pain reported by women during and after adjuvant chemotherapy (taxanes/anthracyclins) following breast cancer using three different methods: (1) the VAS, (2) a colored body image and (3) the two pain questions included in the EORTC-QLQ-C30. The following questions were addressed:

How do women with breast cancer express pain (as reported on the VAS) (1) at baseline, (2) immediately before each cycle of chemotherapy and (3) on Day 10 after each cycle of the six cycles of chemotherapy?

How do the participants experiencing pain >30 on the VAS, report the pain distribution measured on a colored body image, during chemotherapy, and at 12 months after inclusion into the study?

How do the participants experiencing pain >30 on the VAS, report the intensity of pain measured semi-quantitatively on a four-level coloring scale of the colored body image, during chemotherapy and 12 months after inclusion into the study?

How do the participants estimate pain on the EORTC-QLQ-C30 at baseline, after 3 and 12 months after inclusion into the study?

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Participants

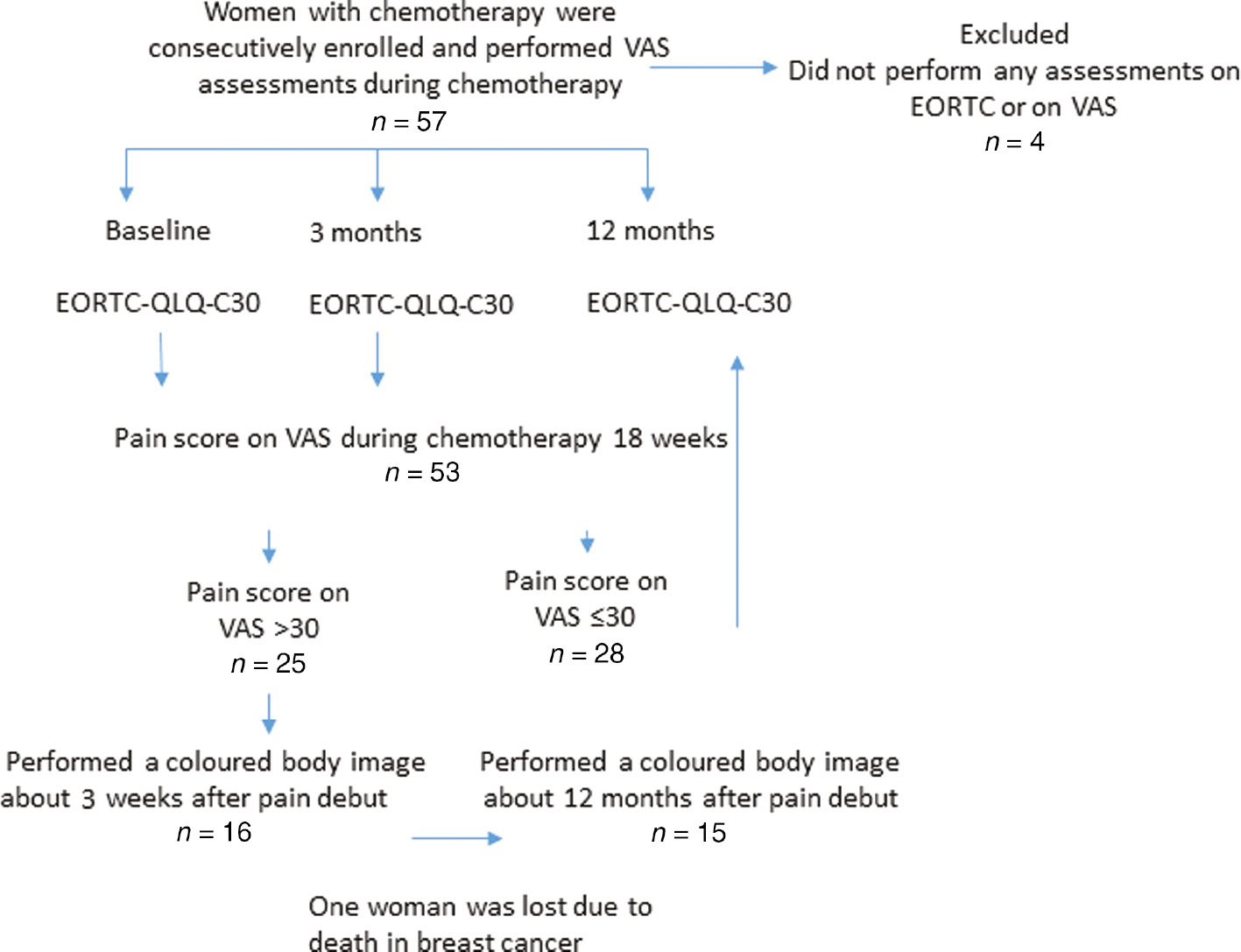

The women were consecutively recruited from “The Breast Cancer and Stress Study”, described elsewhere [21]. The patients were eligible for participation if age 18 years or older and scheduled for adjuvant sequential chemotherapy with doses of ≥75 mg/m2 of docetaxel and epirubicin. Fifty-seven women were consecutively asked to participate in the study from August 2010 to September 2012. Four of them did not complete the VAS or EORTC-C30-QLQ assessments and were therefore excluded, resulting in a total of 53 enrolled women. Only the participants with VAS >30, who had been interviewed in an earlier study (n=16), described in detail elsewhere [21], filled out the colored body image; see Fig. 1. Clinical and demographic information was gathered from the women’s health records and inclusion forms.

Assessment flow chart.

2.2 Assessments

In the present study, pain was assessed using three different methods:

The VAS is an acknowledged and widely used instrument for assessing pain [18] in which the patient is asked to make a mark reflecting the intensity of the perceived pain along a straight line. The response levels vary from no pain (=0) to the worst possible experienced pain (=100) measured in mm and the VAS is considered to have 101 response levels [22]. Pain intensity on the VAS is defined from 10/100 to 30/100 as mild pain and from 40/100 to 60/100 as moderate pain, finally 70/100 to 100/100 as severe pain [20]. Studies show that the VAS correlates well with other self-reported measures of pain intensity [23], [24].

The colored body image is a technique where the patient first marks the localization and distribution of pain and thereafter colors its intensity [19]. The distribution is reported as percentages of the total body image area [25] and the pain intensity is reported semi-quantitatively on a four-level scale using the colors of a traffic light, with an additional high-end intensity shown in black. The perceived pain intensity was indicated by green for no pain, yellow for tolerable pain (i.e. daily life was not impaired and the woman could continue going about her daily routines), red for interruptive pain (i.e. daily life and ordinary routines were substantially affected or stopped due to experienced pain) and, additionally, black for unbearable and excruciating pain [12]. The colored surface areas can overlap, and in such cases the most dominant color was used in the analysis. The proportion of the total surface area of the body is estimated to be: head and neck 9%, arms 9% each, back and front sides of the upper body 18% each, legs 18% each, and genitals 1%. The colored body image is presented as an average of the percentage of the total body image area of the women’s worst experienced pain. The colored body image is analyzed using a model of the Rule of Nines burn area charts [26], [27]. However, in this study the “colored body image” is used to depict the distribution and intensity of the perceived pain.

The EORTC-QLQ-C30 version 3.0 is a cancer-specific self-reported multidimensional instrument, translated into and validated in different languages, and applied across a range of cultural settings [28]. The questionnaire comprises 30 items assessing function and various symptoms, with higher scores representing a higher symptom burden. Two of these items assessing pain were used in this study: Have you been in pain? Have your daily activities been affected by pain? Response choices range from 1 (not at all) to 4 (very much), after which a linear transformation of the raw scores is applied to obtain scores of 0–100 [29].

2.3 Points of assessment

After inclusion, the women were asked to assess their pain on the VAS at baseline, at rest immediately before each cycle of chemotherapy and at Day 10 between the six cycles throughout the treatment. At both the first VAS estimate and before the first cycle, the patient received verbal and written information from a research nurse or assistant on how to use the VAS: how the estimates are performed, how the VAS works, and the timing of measurements for each cycle of treatment. The following VAS estimates were then filled out at home and mailed to the researcher after each cycle of treatment, and mailed after each cycle of treatment.

The participants reporting VAS >30 colored the body image approximately 3 weeks after the pain appeared at any time during chemotherapy (Cycles 1-5), and then again at 12 months after inclusion.

The EORTC-QLQ-C30 along with a prepaid return envelope, was mailed to the women, after inclusion; i.e., at baseline, at the beginning of the adjuvant chemotherapy treatment, 3 months after inclusion (i.e. between Cycles 3 and 4 of their chemotherapy treatment), and finally 12 months after inclusion. A maximum of three reminders were sent out if applicable.

2.4 Statistical analysis

The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences 20.0 for Windows was used for data analysis (SPSS, Inc., an IBM Company, Chicago, IL, USA). The data on background characteristics and disease characteristics were analyzed using descriptive statistics such as means, standard deviations (SD) and frequencies. Mean and SD values are presented for the VAS and the EORTC-QLQ-C30’s two pain questions’ estimates. The colored body image charts were analyzed according to the following procedure: estimated pain distribution using the Rule of Nines burn area charts as the as the percentages of the total body image area colored [25]. Pain distribution and intensity were analyzed based on the colors used [26]. For example, areas colored red on the left arm were summed and then divided by the number of participants. Thereby, the average area with pain intensity colored red on the arm was calculated.

3 Results

3.1 Pain measured using the VAS

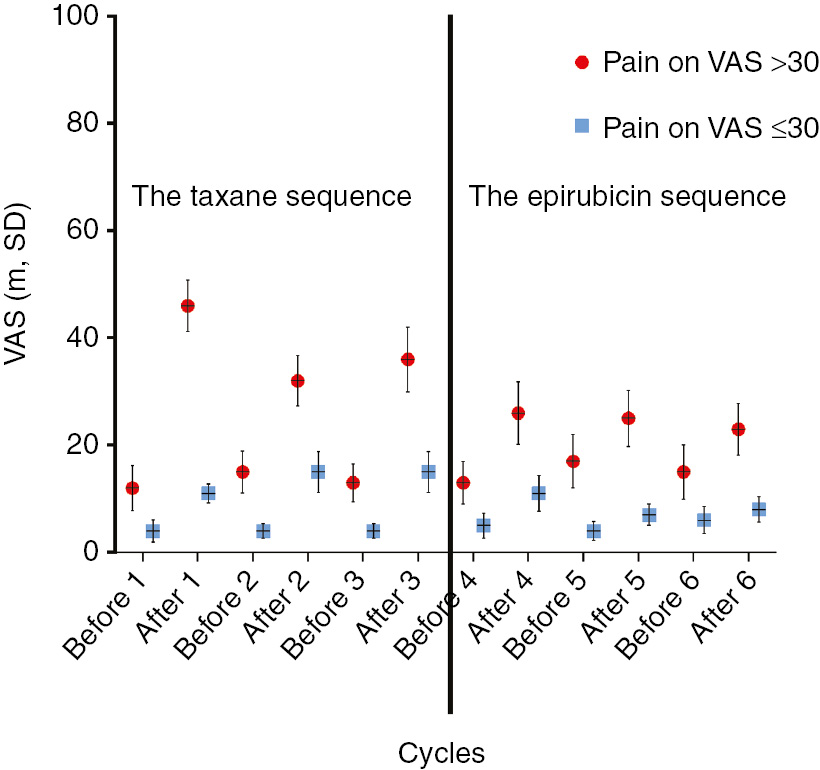

Forty-seven percent (n=25) of the 53 women assessed VAS pain scores >30 at one or several occasions during the treatment (six cycles). The participants with VAS >30 were slightly older and had a lower annual household income than those reporting VAS values less than >30; see Table 1. The mean VAS scores are presented in Fig. 2. The participants with VAS >30 reached in average the highest VAS value in pain after Cycle 1. The most intense pain for all women was noted after Cycle 3. For Cycle 4, the treatment changed from docetaxel to epirubicin for all women except one. During the epirubicin sequence, the participants with VAS >30 continued reporting some pain on the VAS after each cycle of chemotherapy. Although the VAS estimates dropped towards the end of the chemotherapy treatment, they were still higher than before the start of the first cycle.

Participant characteristics.

| Demographics | VAS >30 (n=25) | VAS ≤30 (n=28)a |

|---|---|---|

| Age, median, range | 57 (37–76) | 49 (29–73) |

| Mean VAS at baseline (SD) | 1.16 (2.14) | 0.357 (0.55) |

| Annual household income (EUR), mean | 359,000 | 477,000 |

| Working | 17 | 14 |

| Retired | 7 | 4 |

| On sick leave | 15 | 26 |

| Residential area | ||

| Dalarna | 5 | 8 |

| Gävleborg | 14 | 6 |

| Uppsala | 6 | 14 |

| Type of surgery | ||

| Breast-conserving surgery | 11 | 12 |

| Mastectomy | 14 | 14 |

| Hormone receptor status | ||

| ER+/PR+ | 14 | 13 |

| ER+/PR− | 6 | 2 |

| ER−/PR+ | – | 1 |

| ER−/PR− | 4 | 10 |

| Her2 amplified | 7 | 7 |

| Triple negative | 3 | 6 |

| Not evaluable | 1 | 2 |

| Tumor grade | ||

| I | 2 | 2 |

| II | 13 | 9 |

| III | 9 | 13 |

| Not evaluable | 1 | 2 |

| Sequential taxanes/epirubicin | 25 | 28 |

| Radiation | 15 (missing 0)b | 17 (missing 3)b |

| Endocrine therapy | 20 (missing 3)b | 18 (missing 4)b |

-

ER=estrogen receptor; PR=progesterone receptor. aNo personal bas data ejected (n=2). bData missing.

Estimated pain before each cycle and Day 10 after cycle.

3.2 Pain described by the participants with VAS >30 by coloring a body image

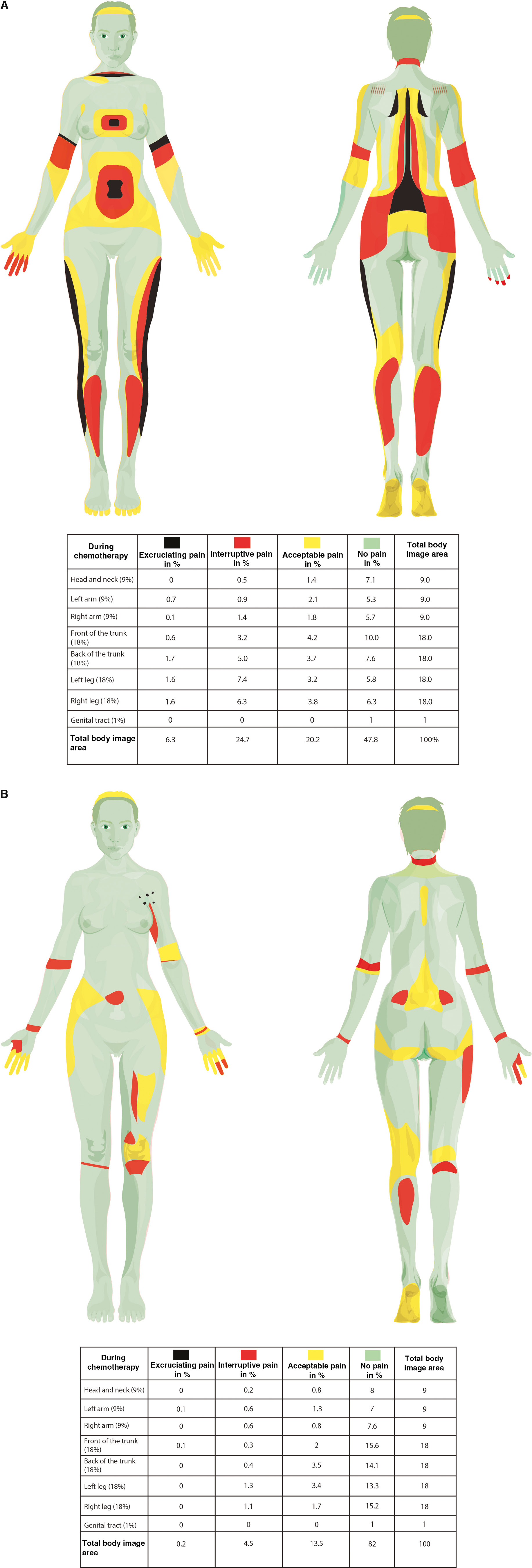

During chemotherapy, an average of 51% of the area of the body images was colored. Perceived pain intensity colored red (interruptive pain) was the most common, covering 25% of the total body surface area, followed by the perceived pain intensity yellow (acceptable pain) covering 20%, and finally, perceived pain intensity as painted black (excruciating pain), which covered 6% of the total body image area. Pain was most commonly indicated in the lower back, knees, thighs and footpads; see Fig. 3A.

(A) A colored body image reveals pain distribution and intensity described during chemotherapy by participants with VAS >30. (B) A colored body image reveals pain distribution and intensity described 12 months after inclusion by participants with VAS >30.

At 12 months after inclusion, the colored pain distribution of the total body area was 18%. At this point the pain intensity colored yellow (acceptable pain) was the most common on over 13% of the total body area, distributed as 5.5% on the trunk, 5% on the legs, 2% on the arms and 0.8% on the head. For the pain intensity colored red (interruptive pain), the total colored area was distributed to 4.5%, with 0.7% on the trunk, 2.4% on the legs, 1.2% on the arms and 0.2% on the head. Traces of black (excruciating pain) (0.2%) were noted on the upper front of the trunk, while the largest part of the body image area, 82%, was colored green and was thus painless (see Fig. 3B). Two of the 15 women colored a completely green body image.

3.3 Pain measured with the EORTC-QLQ-C30

At baseline, the women with VAS >30 estimated an average pain of 41.3 (SD 30.4) on the EORTC-QLQ-C30s two pain questions, compared to 25.0 (SD 25.4) for those reporting VAS less than >30. After 3 months, the average values on the two pain questions were 40.2 (SD 25.0) for the women with VAS >30 and 20.4 (SD 20.5) for those reporting VAS less than >30. One year after baseline, the women with VAS >30 estimated an average pain of 38.6 (SD 27.8), and for those reporting pain on VAS less than >30 the estimated average pain was 21.9 (SD 20.0).

4 Discussion

The current study evaluates the pain experiences of 53 women with breast cancer being treated with sequential adjuvant chemotherapy. The women were assessed regarding the possible development of chemotherapy-induced pain using three different methods: the VAS; a colored body image; and using the two pain items of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire.

Surprisingly widespread and intense pain was detected using this multi-method approach. Different types of pain were found. Given that pain is augmented by anxiety, good communication about treatment effects and side effects is vital for better symptom control.

Twenty-five women (47%) reported pain scores >30 on the VAS one or more occasions after chemotherapy. Most immediately after Cycle 1, VAS increased the most for the women with VAS >30 and for the whole group it increased the most after Cycle 3 (the last docetaxel treatment); thereafter, there was a decline in pain as reported on the VAS. This might be explained by a systemic accumulation of taxane at Cycle 3, which may increase the risk of pain development [30]. However, the women with VAS >30 seem to have had some pain during the epirubicin sequences as well. Although epirubicin is known to result in fatigue, nausea and alopecia it is rarely associated with development of pain [31].

Interpreting the two pain questions on the EORTC-QLQ-C30 at baseline, possibly indicates that there is higher initial pain on EORTC for the group of women with VAS >30. Elevated pain scores at baseline is a warning sign for perceiving more acute clinical pain [32]. However, the VAS measurements before the first cycle of chemotherapy, in which the whole group recorded approximately the same levels of pain, contradict such a conclusion. However, The EORTC-QLQ-C30 questions report perceived pain the past week whereas the VAS reports present pain.

In order to more appropriately detect pain during and after treatment with taxane, the timing of the assessment is important [14]. Cavaletti et al. discussed and evaluated different assessment tools for peripheral neuropathy. They found in their tailored study high levels of pain not previously described in clinical study’s of chemotherapy induced neuropatic pain [33]. One potential explanation for this could be the systematic collection of pain data during the evaluation period, the assessment tools used, the timing of the assessments and, whereby a systematic underreporting of pain is omitted. This also calls attention to the fact that different pain assessment tools capture pain differently. In several previous studies of acute taxane-induced pain, it is not possible to identify either the pain assessment tools nor the time point(s) at which the pain was assessed [34].

The colored body image showed a perceived pain distribution of 51% of the total body surface area during treatment. During chemotherapy, the hands and footpads were colored, which may indicate what is described in the literature as neuropathic pain [35]. Other colored areas possibly indicate myofascial and nociceptive pain in the major muscle groups; the lower back, thighs and calves, and joints. The pain intensity in these areas of the colored body image was mainly ranked as interruptive high pain. This is an alarmingly high percentage of women experiencing a widespread intense pain during chemotherapy. A colored body image can reveal blind spots that are undetectable in conventional pain assessments, and thereby provide important information on pain. Twelve months after inclusion 18% of the body area was involved in pain following the same patterns as during chemotherapy; but its distribution and intensity were lower. These aspects of pain are very important, but are not apparent when conventional pain assessment tools are used. A strength of the colored body image is its communicability, being easily shared and discussed between patients and health professionals. High pain intensities and/or pain perceived over large proportions of the body may also be better indicators that a health professional should offer assistance to the patient.

All measurement tools have limitations, and Dworkin et al. claim that there is a risk of false negative results if one only uses simple estimates of pain in clinical research [17]. This is especially important as cancer patients have been shown to underreport symptoms because they fear this will lead to a change in treatment and a subsequent loss of effectiveness [36]. What patients consider important may depend on a number of individual factors such as symptom burden as well as social and physical conditions [37], and we must communicate these factors and bring them to light during the patient’s care as they are important for the treatment outcome for this individual. The literature highlights certain groups of patients with a higher risk of developing more complex symptoms and receiving less satisfactory relief from these symptoms, such as those in active cancer treatment, and cancer survivors [38]. These two groups are likely undertreated for pain and other symptoms [39].

The merits of a proposed treatment must be considered in relation to its toxicity. What we know today about the likelihood of clinical benefits versus toxicities allows clinicians to adjust the dose of chemotherapy for breast cancer treatment without risking treatment results [7], [8]. Attention must be paid to benefit versus harm, keeping one eye on the dose and the other on the toxicity and the reactions of the nervous system. Preventive pain relief possibly needs to be included in the chemotherapy treatment, with individual escalation of the pain treatment in a way parallel to that in cases of chemotherapy-triggered nausea. This is also indicated by a newly conducted study by Fries et al. in which pain was the most frequently reported symptom [40].

We know that the risk of pain development is at its highest 24–48 h after receiving taxane chemotherapy [14], [34]. Attention should be given to pain evaluation and treatment during this time window. Outpatient chemotherapy treatment may be a further clinical challenge that requires a sensitive, person-centered communication between the patient and the health care personnel. Evaluating important side effects like pain should not be left to the women themselves. Such evaluations should also be done routinely by the health care personnel.

4.1 Strengths and limitations

Firstly, the strength of this study is its use of different methods for assessing pain. Secondly, the colored body image was for the 1st time used in this setting was a simple yet effective way to record and evaluate not only the distribution but also the intensity of pain both during and after chemotherapy. Thirdly, another strength is the longitudinal follow-up of the pain in women undergoing chemotherapy for breast cancer whereby pain was assessed both at baseline, during chemotherapy and 12 months after inclusion. There are also some limitations to the study that should be considered when interpreting its results. Firstly, the VAS assessments between cycles were made by the patient at home. Thus, we cannot be certain of the exact time point of completion. Secondly, we now know that the chosen time point (Day 10) for the VAS assessment is not the appropriate time point to evaluate the highest intensity of taxane-induce pain. Thirdly, the ways of calculating the pain distribution were developed based on burn patients [41]. Today there are several different established ways to calculate the pain distribution using a body image [36]. In this study, we calculated pain distribution and pain intensity using the Rule of Nines burn area charts. There may be other ways to evaluate and calculate the distribution and intensity of pain. Fourthly, we do not know whether the baseline assessment on the EORTC QLQ-C30 questionnaires two pain questions was performed by the patients just before the start of chemotherapy or shortly after. That is, after providing informed consent, the participants received a standardized questionnaire including the EORTC QLQ-C30 questionnaire and patient demographics. The questionnaire was to be completed within seven days of its being received. During this time, it is possible that the treatment had already begun. This may have affected the baseline rated pain on the EORTC QLQ-C30; on the other hand, the EORTC QLQ-C30 questionnaire reflects the previous week. The EORTC QLQ-C30 is known to have large standard deviations in the individual patient score, and thus the confidence intervals are wide [42]. In studies with few participants, the statistical results should be interpreted with caution. With a low number of participants as in this study, the findings could benefit from be replication in a larger study to confirm the results.

5 Conclusion

This study provides information on how different pain assessment tools offer different information. The VAS provides a clear picture of the development of pain during chemotherapy whereas the two pain questions of the EORTC QLQ-C30 give a rough estimate of the pain, most suitable for comparisons between groups. Additionally, the colored body image brings another dimension to the pain assessment, offering additional information on body areas where the pain is perceived, and on pain intensities as experienced by the patient. The colored body image offers unique information on pain that is not available with the two other assessment tools. A multi-method approach to pain assessment, offers many advantages. Prophylactic analgesia during taxane chemotherapy could reduce pain during taxane chemotherapy. Nevertheless, if pain occurs, it is important to quickly identify and treat it. The colored body image is a simple tool for visualizing and sharing the patient’s pain experience. It may be a useful tool for helping the patient and the health care personnel to understand, interpret and treat pain during and after chemotherapy.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all the women who graciously participated in this study.

-

Authors’ statements

-

Research funding: This study was supported by grants from the Swedish Cancer Society (no. 100001), and by the Center for Clinical research in Falun (CKFUU-557501).

-

Conflict of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

-

Informed consent: Both oral and written informed consent was obtained.

-

Ethical approval: The study was carried out in accordance with the code of ethics of the World Medical Association, the Declaration of Helsinki. The BAS study was reviewed and approved by the ethics committee (Dnr 2008/382), with an amendment approved in May 2010.

References

[1] Bray F, Ren JS, Masuyer E, Ferlay J. Global estimates of cancer prevalence for 27 sites in the adult population in 2008. Int J Cancer 2013;132:1133–45.10.1002/ijc.27711Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[2] Fisher B, Jeong JH, Dignam J, Anderson S, Mamounas E, Wickerham DL,Wolmark N. Findings from recent National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project adjuvant studies in stage I breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr 2001;30:62–6.10.1093/oxfordjournals.jncimonographs.a003463Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[3] Tao JJ, Visvanathan K, Wolff AC. Long term side effects of adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with early breast cancer. Breast 2015;24 Suppl 2:S149–53.10.1016/j.breast.2015.07.035Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[4] Mayer LE. Early and late long-term effects of adjuvant chemotherapy. In: asco.org/edbook, editor. ASCO Educational Book 2013:9–14.10.1200/EdBook_AM.2013.33.9Suche in Google Scholar

[5] Eckhoff L, Knoop AS, Jensen MB, Ewertz M. Persistence of docetaxel-induced neuropathy and impact on quality of life among breast cancer survivors. Eur J Cancer 2015;51:292–300.10.1016/j.ejca.2014.11.024Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] Seretny M, Currie GL, Sena ES, Ramnarine S, Grant R, MacLeod MR, Fallon M. Incidence, prevalence, and predictors of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PAIN® 2014;155:2461–70.10.1016/j.pain.2014.09.020Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[7] Schneider BP, Zhao F, Wang M, Stearns V, Martino S, Jones V, Perez EA, Saphner T, Wolff AC, Sledge GW, Wood WC, Davidson NE, Sparano JA. Neuropathy is not associated with clinical outcomes in patients receiving adjuvant taxane-containing therapy for operable breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:3051–7.10.1200/JCO.2011.39.8446Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[8] Hershman DL, Lacchetti C, Dworkin RH, Lavoie Smith EM, Bleeker J, Cavaletti G, Chauhan C, Gavin P, Lavino A, Lustberg MB, Paice J, Schneider B, Smith ML, Smith T, Terstriep S, Wagner-Johnston N, Bak K, Loprinzi CL. Prevention and management of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy in survivors of adult cancers: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline. J Clin Oncol 2014;32:1941–67.10.1200/JCO.2013.54.0914Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] De Iuliis F, Taglieri L, Salerno G, Lanza R, Scarpa S. Taxane induced neuropathy in patients affected by breast cancer: literature review. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2015;96:34–45.10.1016/j.critrevonc.2015.04.011Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[10] Ewertz M, Qvortrup C, Eckhoff L. Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy in patients treated with taxanes and platinum derivatives. Acta Oncol 2015;54:587–91.10.3109/0284186X.2014.995775Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] Browall M, Ahlberg K, Karlsson P, Danielson E, Persson LO, Gaston-Johansson F. Health-related quality of life during adjuvant treatment for breast cancer among postmenopausal women. Eur J Oncol Nurs 2008;12:180–9.10.1016/j.ejon.2008.01.005Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[12] Hellerstedt-Borjesson S, Nordin K, Fjallskog ML, Holmstrom IK, Arving C. Women with breast cancer: experience of chemotherapy-induced pain: triangulation of methods. Cancer Nurs 2015;38:31–9.10.1097/NCC.0000000000000124Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[13] Hellerstedt-Borjesson S, Nordin K, Fjallskog ML, Holmstrom IK, Arving C. Women treated for breast cancer experiences of chemotherapy-induced pain: memories, any present pain, and future reflections. Cancer Nurs 2016;39:464–72.10.1097/NCC.0000000000000322Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[14] Takemoto S, Ushijima K, Honda K, Wada H, Terada A, IMaishi, Kamura T. Precise evaluation of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neurophaty using the visual analogue scale: a quantitaive and comparative analysis of neurophaty occuring with paclitaxel-carboplatin and docetaxel-carboplatin. Int J Clin Oncol 2012;17:367–72.10.1007/s10147-011-0303-6Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[15] Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, Bullinger M, Cull A, Duez NJ, Filiberti A, Flechtner H, Fleishman SB, de Haes JCJM, Kaasa S, Klee M, Osoba D, Razavi D, Rofe PB, Schraub S, Sneeuw K, Sullivan M, Takeda F. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: A Quality-of-Life Instrument for Use in International Clinical Trials in Oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst 1993;85:365–76.10.1093/jnci/85.5.365Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[16] Smith SM, Hunsinger M, McKeown A, Parkhurst M, Allen R, Kopko S, Wilson HD, Burke LB, Desjardins P, McDermott MP, Rappaport BA, Turk DC, Dworkin RH. Quality of pain intensity assessment reporting: ACTTION systematic review and recommendations. J Pain 2015;16:299–305.10.1016/j.jpain.2015.01.004Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[17] Dworkin RH, Burke LB, Gewandter JS, Smith SM. Reliability is necessary but far from sufficient: how might the validity of pain ratings be improved? Clin J Pain 2015;31:599–602.10.1097/AJP.0000000000000175Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[18] Jensen MP, Karoly P. Self-report scales and procedurs for assessing pain in adults. In: Turk DC, Melzack R, editors. Handbook of pain assessment. 3rd ed. New York, London: The Guilford Press, 2011.Suche in Google Scholar

[19] Palmer H. Pain charts; a description of a technique whereby functional pain may be diagnosed from organic pain. N Z Med J 1949;48:187–213.Suche in Google Scholar

[20] Breivik H, Borchgrevink PC, Allen SM, Rosseland LA, Romundstad L, Hals EK, Kvarstein G, Stubhaug A. Assessment of pain. Br J Anaesth 2008;101:17–24.10.1093/bja/aen103Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[21] Nordin K, Rissanen R, Ahlgren J, Burell G, Fjallskog ML, Borjesson S, Arving C. Design of the study: how can health care help female breast cancer patients reduce their stress symptoms? A randomized intervention study with stepped-care. BMC Cancer 2012;12:167.10.1186/1471-2407-12-167Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[22] Myles PS, Urquhart N. The linearity of the visual analogue scale in patients with severe acute pain. Anaesth Intensive Care 2005;33:54–8.10.1177/0310057X0503300108Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[23] Jensen MP, Karoly P, Braver S. The measurement of clinical pain intensity: a comparison of six methods. Pain 1986;27:117–26.10.1016/0304-3959(86)90228-9Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[24] Breivik EK, Björnsson GA, Skovlund E. A comparison of pain rating scales by sampling from clinical trial data. Clin J Pain 2000;16:22–8.10.1097/00002508-200003000-00005Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[25] Barbero M, Fernandez-de-Las-Penas C, Palacios-Cena M, Cescon C, Falla D. Pain extent is associated with pain intensity but not with widespread pressure or thermal pain sensitivity in women with fibromyalgia syndrome. Clin Rheumatol 2017;36:1427–32.10.1007/s10067-017-3557-1Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[26] Wachtel TL, Berry CC, Wachtel EE, Frank HA. The inter-rater reliability of estimating the size of burns from various burn area chart drawings. Burns 2000;26:156–70.10.1016/S0305-4179(99)00047-9Suche in Google Scholar

[27] Visser EJ, Ramachenderan J, Davies SJ, Parsons R. Chronic widespread pain drawn on a body diagram is a screening tool for increased pain sensitization, psycho-social load, and utilization of pain management strategies. Pain Pract 2016;16:31–7.10.1111/papr.12263Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[28] Bjordal K, de Graeff A, Fayers P, Hammerlid E, van Pottelsberghe C, Curran D, Ahlner-Elmqvist M, Maher EJ, Meyza JW, Bredart A, Soderholm AL, Arraras JJ, Feine JS, Abendstein H, Morton RP, Pignon T, Huguenin P, Bottomly A, Kaasa S. A 12 country field study of the EORTC QLQ-C30 (version 3.0) and the head and neck cancer specific module (EORTC QLQ-H&N35) in head and neck patients. Eur J Cancer 2000;36:1796–807.10.1016/S0959-8049(00)00186-6Suche in Google Scholar

[29] Fayers PM, Aaronson NK, Bjordal K, Grønvold M, Curran D, Bottomley A. EORTC QLQ-C30 scoring manual. Brussels: European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer, 2001.Suche in Google Scholar

[30] Jung BF, Herrmann D, Griggs J, Oaklander AL, Dworkin RH. Neuropathic pain associated with non-surgical treatment of breast cancer. Pain 2005;118:10–4.10.1016/j.pain.2005.09.014Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[31] Cameron D, David C, James PM, Peter C, Galina V. Accelerated versus standard epirubicin followed by cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and fluorouracil or capecitabine as adjuvant therapy for breast cancer in the randomised UK TACT2 trial (CRUK/05/19): a multicentre, phase 3, open-label, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 2017;18:929–45.10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30404-7Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[32] Corrêa JB, Costa LOP, de Oliveira NTB, Sluka KA, Liebano RE. Central sensitization and changes in conditioned pain modulation in people with chronic nonspecific low back pain: a case–control study. Exp Brain Res 2015;233:2391–9.10.1007/s00221-015-4309-6Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[33] Cavaletti G, Cornblath DR, Merkies ISJ, Postma TJ, Rossi E, Frigeni B, Alberti P, Bruna J, Velasco R, Argyriou AA, Kalofonos HP, Psimaras D, Ricard D, Pace A, Galiè E, Briani C, Dalla Torre C, Faber CG, Lalisang RI, Boogerd W, et al. The chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy outcome measures standardization study: from consensus to the first validity and reliability findings. Ann Oncol 2012;24:454–62.10.1093/annonc/mds329Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[34] Fernandes R, Mazzarello S, Hutton B, Shorr R, Majeed H, Ibrahim MF, Jacobs C, Ong M, Clemons M. Taxane acute pain syndrome (TAPS) in patients receiving taxane-based chemotherapy for breast cancer-a systematic review. Support Care Cancer 2016;24:3633–50.10.1007/s00520-016-3256-5Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[35] Ventzel L, Jensen AB, Jensen AR, Jensen TS, Finnerup NB. Chemotherapy-induced pain and neuropathy: a prospective study in patients treated with adjuvant oxaliplatin or docetaxel. Pain 2016;157:560–8.10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000404Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[36] Cavaletti G, Marmiroli P. Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neurotoxicity. Curr Opin Neurol 2015;28:500–7.10.1097/WCO.0000000000000234Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[37] Osoba D, Rodrigues G, Myles J, Zee B, Pater J. Interpreting the significance of changes in health-related quality-of-life scores. J Clin Oncol 1998;16:139–44.10.1200/JCO.1998.16.1.139Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[38] Fisch MJ, Lee J-W, Weiss M, Wagner LI, Chang VT, Cella D, Manola JB, Minasian LM, McCaskill-Stevens W, Mendoza TR, Cleeland CS. Prospective, observational study of pain and analgesic prescribing in medical oncology outpatients with breast, colorectal, lung, or prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:1980–8.10.1200/JCO.2011.39.2381Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[39] Burton AW, Fanciullo GJ, Beasley RD, Fisch MJ. Chronic pain in the cancer survivor: a new frontier. Pain Med 2007;8:189–98.10.1111/j.1526-4637.2006.00220.xSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[40] Friese CR, Harrison JM, Janz NK, Jagsi R, Morrow M, Li Y, Hamilton AS, Ward KC, Kurian AW, Katz SJ, Hofer TP. Treatment-associated toxicities reported by patients with early-stage invasive breast cancer. Cancer 2017;123:1925–34.10.1002/cncr.30547Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[41] Margolis RB, Tait RC, Krause SJ. A rating system for use with patient pain drawings. Pain 1986;24:57–65.10.1016/0304-3959(86)90026-6Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[42] Scott NV, Fayers P, Aaronson NK, Bottomley A, de Graeff A, Groenvold M, Gundy C, Koller M, Petersen MA, Ag M. EORTC QLQ-C30. Reference values. Brussels: EORTC, 2008.Suche in Google Scholar

©2018 Scandinavian Association for the Study of Pain. Published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston. All rights reserved.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Editorial comment

- Support for mirror therapy for phantom and stump pain in landmine-injured patients

- Lifting with straight legs and bent spine is not bad for your back

- Bipolar radiofrequency neurotomy for spinal pain – a promising technique but still some steps to go

- Topical review

- Prevalence, localization, perception and management of pain in dance: an overview

- Clinical pain research

- Pain assessment in native and non-native language: difficulties in reporting the affective dimensions of pain

- Colored body images reveal the perceived intensity and distribution of pain in women with breast cancer treated with adjuvant taxanes: a prospective multi-method study of pain experiences

- Physiotherapy pain curricula in Finland: a faculty survey

- Mirror therapy for phantom limb and stump pain: a randomized controlled clinical trial in landmine amputees in Cambodia

- Pain and alcohol: a comparison of two cohorts of 60 year old women and men: findings from the Good Aging in Skåne study

- Prolonged, widespread, disabling musculoskeletal pain of adolescents among referrals to the Pediatric Rheumatology Outpatient Clinic from the Päijät-Häme Hospital District in southern Finland

- Impact of the economic crisis on pain research: a bibliometric analysis of pain research publications from Ireland, Greece, and Portugal between 1997 and 2017

- Measurement of skin conductance responses to evaluate procedural pain in the perioperative setting

- Original experimental

- An observational study of pain self-management strategies and outcomes: does type of pain, age, or gender, matter?

- Fibromyalgia patients and healthy volunteers express difficulties and variability in rating experimental pain: a qualitative study

- Effect of the market withdrawal of dextropropoxyphene on use of other prescribed analgesics

- Observational study

- Winning or not losing? The impact of non-pain goal focus on attentional bias to learned pain signals

- Gabapentin and NMDA receptor antagonists interacts synergistically to alleviate allodynia in two rat models of neuropathic pain

- Offset analgesia is not affected by cold pressor induced analgesia

- Central and peripheral pain sensitization during an ultra-marathon competition

- Reduced endogenous pain inhibition in adolescent girls with chronic pain

- Evaluation of implicit associations between back posture and safety of bending and lifting in people without pain

- Assessment of CPM reliability: quantification of the within-subject reliability of 10 different protocols

- Cerebrospinal fluid cutaneous fistula after neuraxial anesthesia: an effective treatment approach

- Pain in the hand caused by a previously undescribed mechanism with possible relevance for understanding regional pain

- The response to radiofrequency neurotomy of medial branches including a bipolar system for thoracic facet joints

- Letter to the Editor

- Diagnosis of carpal tunnel syndrome – implications for therapy

- Reply to the Letter to the Editor by Ly-Pen and Andréu

- Letter to the Editor regarding “CT guided neurolytic blockade of the coeliac plexus in patients with advanced and intractably painful pancreatic cancer”

- Reply to comments from Ulf Kongsgaard to our study

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Editorial comment

- Support for mirror therapy for phantom and stump pain in landmine-injured patients

- Lifting with straight legs and bent spine is not bad for your back

- Bipolar radiofrequency neurotomy for spinal pain – a promising technique but still some steps to go

- Topical review

- Prevalence, localization, perception and management of pain in dance: an overview

- Clinical pain research

- Pain assessment in native and non-native language: difficulties in reporting the affective dimensions of pain

- Colored body images reveal the perceived intensity and distribution of pain in women with breast cancer treated with adjuvant taxanes: a prospective multi-method study of pain experiences

- Physiotherapy pain curricula in Finland: a faculty survey

- Mirror therapy for phantom limb and stump pain: a randomized controlled clinical trial in landmine amputees in Cambodia

- Pain and alcohol: a comparison of two cohorts of 60 year old women and men: findings from the Good Aging in Skåne study

- Prolonged, widespread, disabling musculoskeletal pain of adolescents among referrals to the Pediatric Rheumatology Outpatient Clinic from the Päijät-Häme Hospital District in southern Finland

- Impact of the economic crisis on pain research: a bibliometric analysis of pain research publications from Ireland, Greece, and Portugal between 1997 and 2017

- Measurement of skin conductance responses to evaluate procedural pain in the perioperative setting

- Original experimental

- An observational study of pain self-management strategies and outcomes: does type of pain, age, or gender, matter?

- Fibromyalgia patients and healthy volunteers express difficulties and variability in rating experimental pain: a qualitative study

- Effect of the market withdrawal of dextropropoxyphene on use of other prescribed analgesics

- Observational study

- Winning or not losing? The impact of non-pain goal focus on attentional bias to learned pain signals

- Gabapentin and NMDA receptor antagonists interacts synergistically to alleviate allodynia in two rat models of neuropathic pain

- Offset analgesia is not affected by cold pressor induced analgesia

- Central and peripheral pain sensitization during an ultra-marathon competition

- Reduced endogenous pain inhibition in adolescent girls with chronic pain

- Evaluation of implicit associations between back posture and safety of bending and lifting in people without pain

- Assessment of CPM reliability: quantification of the within-subject reliability of 10 different protocols

- Cerebrospinal fluid cutaneous fistula after neuraxial anesthesia: an effective treatment approach

- Pain in the hand caused by a previously undescribed mechanism with possible relevance for understanding regional pain

- The response to radiofrequency neurotomy of medial branches including a bipolar system for thoracic facet joints

- Letter to the Editor

- Diagnosis of carpal tunnel syndrome – implications for therapy

- Reply to the Letter to the Editor by Ly-Pen and Andréu

- Letter to the Editor regarding “CT guided neurolytic blockade of the coeliac plexus in patients with advanced and intractably painful pancreatic cancer”

- Reply to comments from Ulf Kongsgaard to our study