Abstract

Background and aims

The evidence for interventional treatment of thoracic facet joint pain remains limited. This is partly due to inconsistency of the path of thoracic medial branches and a lower incidence of thoracic facet pain among spine pain patients. The purpose of this study is to evaluate the efficacy of bipolar radiofrequency (RF) neurotomy of medial branches for treating chronic thoracic facet joint pain.

Methods

This is a retrospective record review of all patients diagnosed to have thoracic facet pain with diagnostic block and subsequently treated with bipolar RF neurotomy of medial branch between January 2012 and December 2015. The outcome measures were mean changes in Numeral Rating Scale (NRS) and Pain Disability Index (PDI).

Results

There were 71 patients with complete data available for analysis. The mean age of the patients was 57.9±11.2 years. The mean duration of pain was 23±10.5 months. The majority of patients (82%) had pain reduction of more than 50% at 12 months after bipolar RF neurotomy. The NRS decreased significantly from baseline of 7.75±1.25 to 2.86±1.53 at 3 months and 2.82±1.29 at 12 months post-procedure (p<0.001. p<0.001, respectively). The PDI improved significantly from 40.92±12.22 to 24.15±9.79, p<0.05). There were no serious adverse effects or complications of the procedure reported in this study.

Conclusions

Bipolar RF neurotomy of thoracic medial branch is associated with a significant reduction in thoracic facet joint pain. The promising findings from this case series merit further assessment with prospective, randomized controlled trial which will produce a more reliable and accurate finding for its clinical applications.

1 Introduction

There are relatively few studies on thoracic facet joint denervation in the management of chronic thoracic spine pain as the thoracic spine in general is the least common site for back pain complaints, with a reported prevalence being only 13% in contrast to 43% for low back pain and 32% for neck pain [1]. However, when back pain is narrowed into regional pain disorders, as high as 48% of thoracic spine pain (upper and middle back) was due to thoracic facet joint pain [2].

The diagnostic criteria for thoracic facet joint pain remain inconclusive. The usual presentations include the following symptoms and signs: (1) history of thoracic paravertebral pain that worsens with prolonged standing, or rotation of the thoracic spinal column [3]; (2) back pain with a typical radiation pattern of thoracic facet joints [4, 5]; (3) reproduction of paravertebral tenderness upon pressure on the respective facet joint; (4) no significant neurological deficit; (5) normal or minimal changes in radiological images which exclude other sources of pain; (6) elimination of pain with intra-articular or medial branch injection of local anesthetic [3].

Radiofrequency (RF) neurotomy of the medial branch of dorsal rami has been used for the treatment of spinal pain of facet joint origin, at all spinal levels since 1970s [6, 7]. Despite being the treatment of choice for facet joint pain, there is still a paucity of literature on RF neurotomy of thoracic medial branch [8]. This could be due to inconsistency in the path of the thoracic medial branch across the transverse process before innervating the facet joint [4, 5], and a lower incidence of thoracic back pain compared to the cervical and lumbar regions [1].

Bipolar RF is an improvement of conventional RF neurotomy, as it creates a larger but more precise lesion during denervation [9, 10]. Bipolar RF neurotomy has been used in different pain disorders with variable efficacy, e.g. sacroiliac joint pain [11, 12], lumbar discogenic pain [13, 14] and ischemic pain syndrome [15, 16].

As there is no study on bipolar RF neurotomy of thoracic medial branch, the aims of this retrospective study are to describe the technique of bipolar RF neurotomy of thoracic medial branch and to evaluate the outcome of this technique in the treatment of chronic thoracic facet joint pain.

2 Methods

This is a retrospective, observational study of chronic pain patients undergoing bipolar RF neurotomy of thoracic medial branch at Orbis Medical Center (Zuyderland), Hospital Sittard Geleen (Heerlen), The Netherlands between January 2012 and December 2015. The study was approved by institutional research review board. Patients with treatment of facet joint pain involving two regions, e.g. cervico-thoracic and thoraco-lumbar regions were also included in this study. After identification of eligible cases using computerized clinic registry, medical records, procedure charts and follow-up questionnaires of all patients were reviewed. Confidential and de-identified data collected included patient demographics such as age, gender, body mass index and occupation; and clinical data such as diagnosis, duration of pain, previous treatment, adverse effects and complications from the procedure.

During patient evaluation, pain pattern and distribution suggestive of thoracic facet joint pain and local tenderness over facet joint area (spinal paramedian area) were identified and other pathologies of the thoracic region, such as vertebral fracture, stenosis, malignancy, infection and radiculitis were excluded, both by clinical or radiological examinations. Once thoracic facet joint pain was suspected, patients received a diagnostic thoracic medial branch block using 0.5 mL of 0.5% levobupivacaine to confirm the diagnosis, according to the standard of the SIS Guidelines [17]. The patients with more than 50% pain reduction lasting longer than 3 h after the diagnostic block were offered bipolar RF neurotomy of thoracic medial branch subsequently. Informed consent of the treatment was obtained after discussing the benefits and the possible adverse effects of bipolar RF neurotomy of thoracic medial branch including infection, allergic reaction, transient radicular pain and pneumothorax.

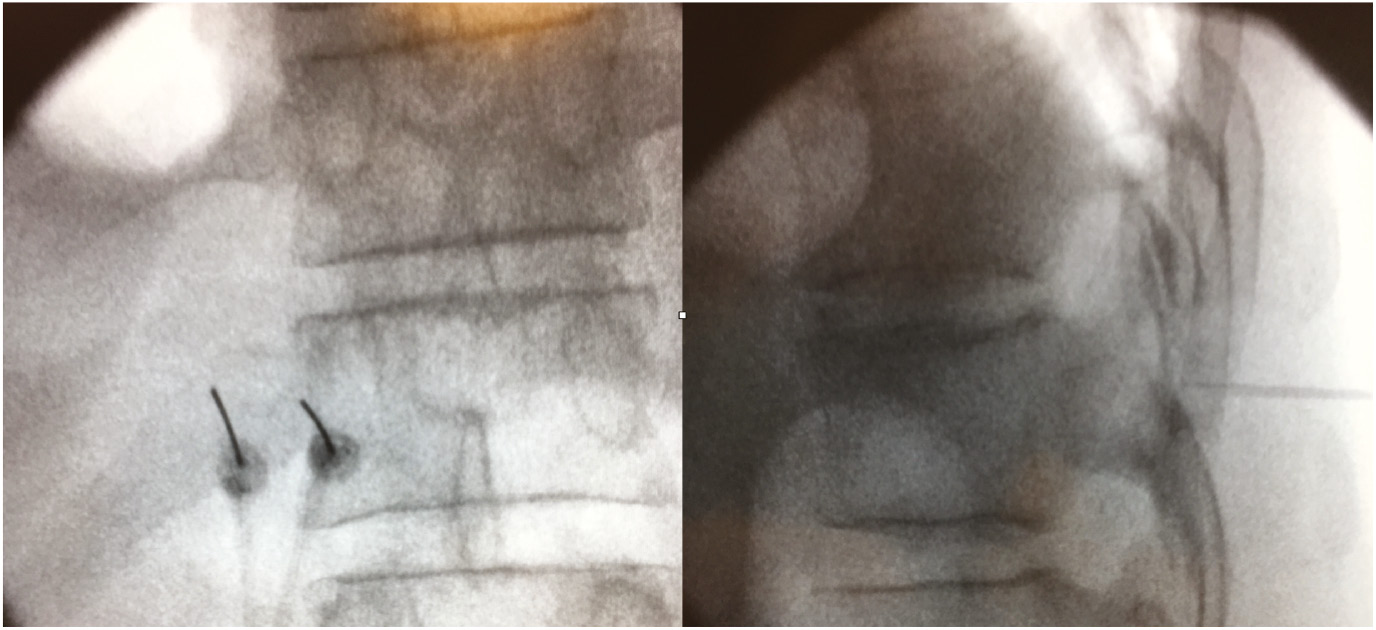

For bipolar RF neurotomy of thoracic medial branch, two 22 gauge 10 cm, sharp and straight RF insulated cannulas with an active tip of 10 mm, two 10 cm CSK-TC10 electrodes and a Cosman G4 RF generator (Cosman Medical, Inc., Burlington, MA, USA) were used. The procedure was performed with the patient in prone position on a radiolucent table. The C-arm of the fluoroscope was positioned in the axial plane and the proper level was identified by a radiopaque marker. The C-arm was turned cephalocaudal in order to square the end plates of the vertebrae. After identifying the transverse process, the skin was anesthetized with 0.5–1.0 mL of 1% lidocaine superficially and a RF cannula was inserted at the superior and lateral most portion of the transverse process. It was advanced in a tunnel view method until bone contact with the transverse process was made. A second similar RF cannula was inserted 5–10 mm medial and inferior to the first RF cannula in a similar manner as the first cannula until bone contact was made at the angle of the transverse and superior articular processes. A lateral fluoroscopic view was done to ensure that the tips of both cannulas were posterior to the line that connected the posterior aspects of the intervertebral foramina. Satisfactory final placement for both cannulas was confirmed with anteroposterior and lateral fluoroscopic views (Fig. 1). Neurostimulation was carried out first with 50 Hz which reproduced the pain, then followed with 2 Hz. The 2 Hz motor stimulation elicited contraction of the multifidus muscles at intensities below 0.5 V [3]. Subsequently, 0.5 mL levobupivacaine 0.5% was injected through both RF cannulas. Two RF electrodes were then inserted through the two cannulas, and the electrode tip temperatures were raised to 80°C for 90 s. One bipolar RF lesion was made for the medial branch of each thoracic ramus. As for treatment of facet joint pain involving two regions, e.g. cervico-thoracic and thoraco-lumbar regions, RF neurotomy of cervical and lumbar medial branches were carried out based on the conventional monopolar technique previously described [18, 19]. Patients were discharged home with oral celecoxib 400 mg daily, pantoprazole 40 mg daily and paracetamol 1 g 3 times daily for 5 days to relieve post-procedural needle soreness.

Anteroposterior and lateral fluoroscopic images of bipolar RF cannulas at target points (transverse process of thoracic vertebra). Note the cannulas are parallel and 10 mm apart to each other within the area of the transverse process in anteroposterior view. In lateral view, the tips of both the cannulas are located posterior to the line that connects the posterior aspects of the intervertebral foramina.

The primary outcome measurements were analgesic efficacy of bipolar RF neurotomy using Numerical Rating Scale (NRS) which measures pain from no pain to worst possible pain on a 0–10 scale and Pain Disability Index (PDI) with scores ranging from 0 to 70, with the higher index reflecting the person’s greater disability from pain [20]. Both NRS and PDI were done during clinic visit prior to treatment (baseline) and at 3rd month after treatment. For the study purpose, telephone calls were made during data collection to enquire NRS at 12th month after treatment. Reduction in medication use after treatment, as well as the number of complications such as pneumothorax, flare-up pain, intercostal neuritis, hematoma formation, infection and spinal cord trauma were recorded.

Data were analyzed using SPSS software version 12.0. Descriptive statistics of the data were presented as a mean and standard deviation. Frequency and descriptive statistics were calculated to check all relevant characteristics of the data. Differences in NRS and PDI during subsequent follow-up visits with baseline measurements were measured with Wilcoxin Signed Ranks test.

3 Results

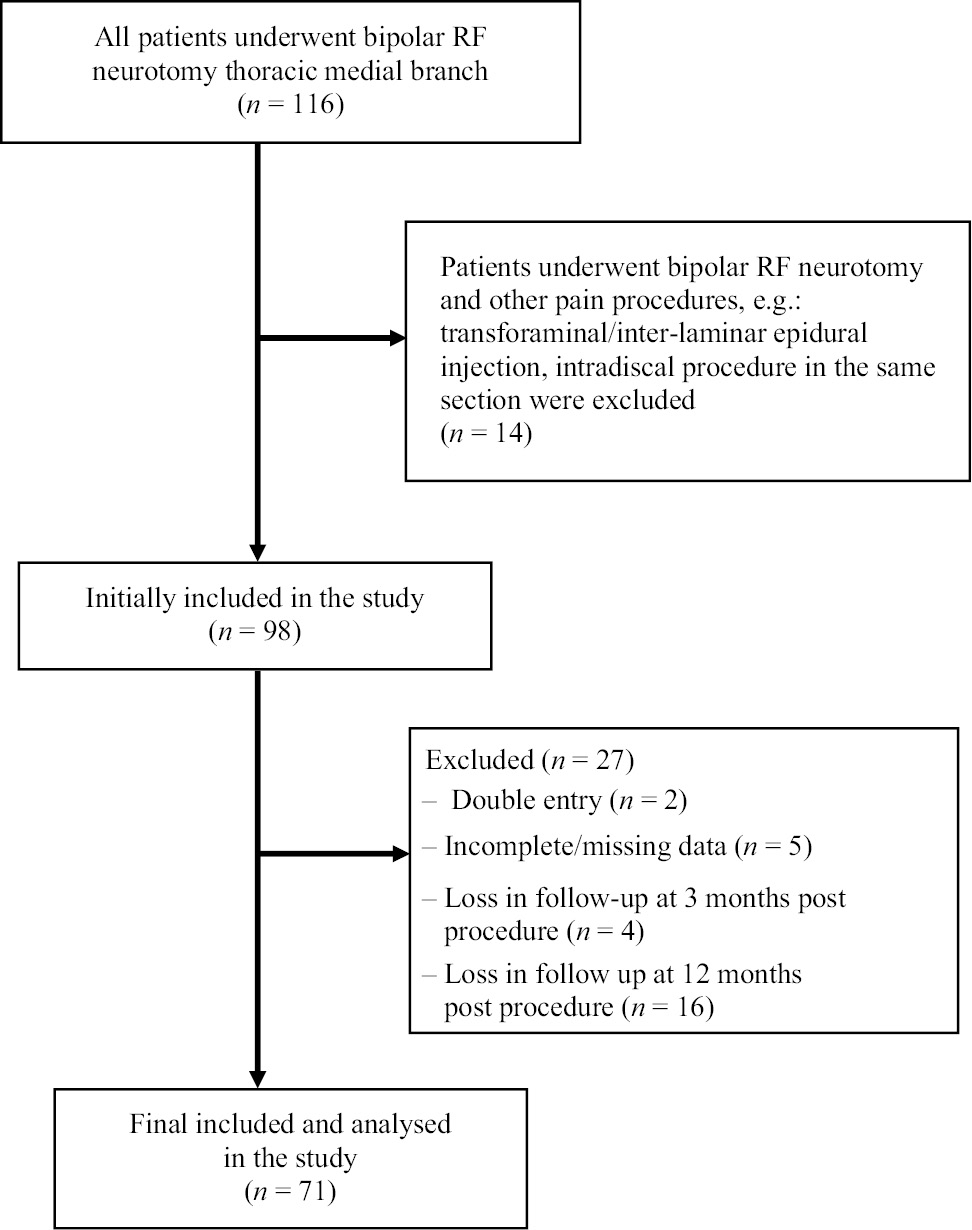

Between January 2012 and December 2015, 116 patients were treated with bipolar RF neurotomy of thoracic medial branch. As a tertiary referral pain center, with many of our patients coming from great distances, we had a number of patients lost to follow-up. Consequently, the findings presented in this study were derived from complete data of 71 patients (Fig. 2). Those who lost to follow ups or with missing data were excluded from the study.

Flow diagram of the study.

The patient population consisted of 45 male and 26 female patients with a mean age of 57.9±11.2 years. The mean BMI of patients was 27.14±2.72 kg/m2. The mean duration of pain was 23±10.5 months. According to our patient data, 56 (79%) procedures were carried out on the cervicothoracic region, three (4%) procedures on the thoracolumbar region and 16 (17%) on the thoracic region alone. Thirty-eight patients (54%) had the procedure performed on the right side, 29 patients (41%) on the left side, and four patients (6%) bilaterally. During the period of observation, none of the patients required repeat bipolar RF neurotomy. Demographic data and clinical presentation of patients are summarized in Table 1.

Baseline demographic characteristics and clinical presentation of patients.

| n=71 | |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 45 |

| Female | 26 |

| Age (year) | 57.9±11.2 |

| Height (m) | 1.77±3.37 |

| Weight (kg) | 84.73±2.90 |

| BMI | 27.14±2.72 |

| Duration of pain (month) | 23.0±10.5 |

| Treated spine level | |

| C6–T2 | 41 |

| C7–T2 | 15 |

| T1–T3 | 2 |

| T3–T5 | 1 |

| T3–T6 | 1 |

| T4–T6 | 4 |

| T4–T7 | 3 |

| T5–T7 | 3 |

| T9–T12 | 2 |

| T10–L1 | 2 |

| T11–L1 | 1 |

Eighty-two percent of patients (58 out of 71) reported more than 50% decrease in NRS both at 3 and 12 months after bipolar RF neurotomy of thoracic medial branch. Pain relief was statistically significant when comparing baseline NRS of 7.75±1.25 with NRS at 3 months (2.86±1.53) and 12 months (2.82±1.29) post procedure, p<0.001 (Table 2). A similar finding was shown in the difference between baseline PDI of 40.9±12.2 with PDI at 3 months post procedure (24.2±9.8), p<0.001 (Table 2). Serious adverse effects of the procedure such as pneumothorax, infection, hematoma formation, nerve root trauma or spinal cord injury were not reported in this study.

Mean pain and disability outcomes of patients at different time points.

| Baseline (SD) | 3 months later (SD) | 12 months later (SD) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NRS | 7.75 (1.25) | 2.86 (1.53) | 2.82 (1.29) | <0.001 |

| PDI | 40.92 (12.22) | 24.15 (9.79) | – | <0.001 |

-

NRS=numerical rating scale; PDI=Pain Disability Index; SD=standard deviation; p-value from Wilcoxon Signed Ranks test.

4 Discussion

In recent years, interventional pain management has seen many new areas of advancement, with the aim of increasing the efficacy in alleviating symptoms, at the same time improving the safety of patients during procedure. The current evidence for conventional monopolar RF neurotomy of the cervical and lumbar medial branches in the treatment of respective facet joint pain is relatively strong. However, such evidence has not been demonstrated in the treatment of thoracic facet joint pain [3, 21, 22]. Current available treatment of thoracic facet joint pain includes thoracic facet joint injection, medial branch of dorsal rami block and RF neurotomy [8]. Studies by Manchikanti et al. showed that thoracic medial branch block with local anesthetics with or without steroid significantly reduced pain and improved functional status but the effect did not last long as most patients required repeated medial branch block with an average of 3.5 blocks per year [23, 24]. Stolker et al. reported a case series of 40 patients who underwent conventional RF neurotomy of medial branch of thoracic dorsal rami. In this study, 80% of the participants showed more than 50% pain relief at 12 month follow-up [25]. In another series which reported 17 monopolar RF neurotomy on thoracic medial branch, only 40% of patients had more than 50% pain relief [26]. Subset data of a more recent study by Speldewinde showed that 68% of 28 monopolar RF neurotomies of thoracic medial branch had a 50% pain reduction lasting longer than 2 months [27]. In contrast, the current study with bipolar RF neurotomy showed the highest success rate with 82% of 71 patients having more than 50% pain reduction even at 12 months after treatment. Cooled RF, another variant of conventional RF was recently shown to be able to produce neurotomy lesions larger than conventional monopolar RF on thoracic medial branches in human cadavers [28]. However, human studies with long term clinical outcome and safety profile utilizing this technique are still limited. One recent reported case of third degree skin burn in the treatment of thoracic facet joint pain with cooled RF raised the question of the safety profile of this technique [29].

The inconsistent association between the medial branch and a bony landmark (transverse process) makes the thoracic medial branch a challenging target for percutaneous interventions [4, 5]. It has also been demonstrated that the thoracic medial branch at some vertebral levels does not have bone contact with the transverse process [30]. Furthermore, the morphology of the thoracic transverse process changes quite significantly from T1 till T12 level. Based on the most recent human cadaveric studies, the width of unilateral transverse process increases from T1 till T5, subsequently decreases to T12 [31, 32].

Accurate placement of the electrode adjacent to the targeted neural structure is the most important factor in ensuring the successful outcome of RF neurotomy. This could be difficult to achieve in the case of thoracic facet joint denervation due to inconsistency of the neural pathway of medial branch of dorsal rami and changes in transverse process morphology of the thoracic spine. These shortcomings could be overcome by increasing the area of RF neurotomy lesion with bipolar RF, as the coverage are of two bipolar RF needles is larger compared to the single needle conventional monopolar RF technique [33].

As the transverse processes of thoracic vertebrae are relatively flat and superficial [29, 30], the insertion of the first RF needle at the superolateral aspect of the transverse process in tunnel view under antero-posterior fluoroscopic guidance is relatively straight forward and safe but similar to other interventional procedures done in the thoracic region, bipolar RF neurotomy of thoracic medial branches carries the risk of pleural puncture [3]. To prevent this complication, fluoroscopic visualization of the transverse process before needle insertion is crucial. The first needle should be inserted within 1–2 mm of the superolateral border of the transverse process in a tunnel vision. It is not necessary to place a needle at the superior and lateral most border of the transverse process, as the needle may slip pass the transverse process and puncture the pleura inadvertently. The second needle should be inserted strictly parallel to the first and the depth of insertion for the second needle should be the same as the first, in order to prevent diversion of the second needle. Anatomical studies of the average size of the transverse processes across the whole spine indicated that the transverse processes in the thoracic vertebrae can safely accommodate two RF cannulas 5–10 mm apart depending on the level of thoracic spine, when carrying out the bipolar RF neurotomy [31, 32].

Bipolar RF neurotomy is essentially an extension of conventional monopolar RF neurotomy. Although monopolar and bipolar RF neurotomies differ in their mechanisms of grounding (grounding pad vs. passive electrode, respectively), the complications and adverse effects are similar. Conventional monopolar RF neurotomy has been utilized in pain management for the past five decades and is proven to have a good safety profile [29, 34, 35, 36]. Bipolar RF neurotomy is utilized in the treatment of other pain conditions, especially those with inconsistent or complex neural anatomy, such as in sacroiliac joint denervation and lumbar sympathectomy [11, 12, 15, 16]. Based on the study by Cosman and Gonzalez bipolar RF with two RF needles with 10 mm active tips 10 mm apart will produce an elongated lesion, measuring approximately 15 mm by 8 mm, a lesion area which almost covers the whole surface of a thoracic transverse process [9]. With such a large area of electrical field coverage over the transverse process, it is not surprising to observe sensory stimulation of 0.4 V reproducing concomitant pain and motor stimulation of 0.9 V eliciting contraction of multifidus muscle during the first attempt of needle placement in most patients without further adjustment of needles positions. However, this finding should be investigated further to compare the efficiency of bipolar versus monopolar RF neurotomy in terms of the need for electrostimulation. The amount of radiation exposure prior to achieving satisfactory needle placement and the duration of the whole procedure should be the subject of further investigation. Pertaining to bipolar RF technique, Kim reported a series of nine patients who underwent bipolar RF thermocoagulation of thoracic facet joint by inserting two RF cannulas 5 mm apart directly into the inferior aspect of the facet joint. Assessment was carried out only at 1 month post-procedure and six patients had significant pain reduction [37].

Most of the bipolar RF neurotomies in this study took place at the cervico-thoracic junction. This is an area of transition from a mobile cervical to a rigid thoracic spine, and from cervical lordosis to thoracic kyphosis, and is an injury-prone area of the spine [38, 39]. The incidence of thoracic facet joint pain may be under reported, as patients who present with lower neck or upper back pain might be only receiving cervical facet joint treatment with thoracic facet joint pain being neglected, due to lower success rate with conventional RF neurotomy of thoracic medial branches.

In the present study, we hypothesized that post-procedural pain after bipolar RF neurotomy would be much greater than that of conventional monopolar RF neurotomy, as the larger lesion size would have caused a larger area of acute soft tissue injury. It is our routine practice to prescribe all patients oral analgesics, e.g. celecoxib and paracetamol, if not otherwise contraindicated in order to decrease post-procedural needle soreness and discomfort. We observed that all the participants in this study tolerated the procedure well and none of them came back complaining of localized flare up pain. However, the finding of post-procedural pain tolerance should be validated comparing bipolar with monopolar RF neurotomy.

The limitation of the current study is that it is retrospective in design, and therefore it has all the flaws and problems associated with such studies. Only data of 71 out of 116 patients were complete and available for analysis, which includes a risk of selection bias. A very high portion of patients (83%) received a combined treatment including monopolar neurotomy either at cervical (n = 56) or lumbar (n = 3) levels would have affected the outcome of the treatment in current study. Selection of patients with only thoracic facet pain, rather than patients with pain from two regions, such as cervicothoracic and thoracolumbar facet joint, might have been a more accurate reflection of the efficacy of bipolar RF neurotomy in the treatment of thoracic facet pain. This is because the monopolar RF neurotomy of both cervical and lumbar medial branch is well studied and the successful outcome is very high. Hence, combined treatment for facet pain of two regions as in most of the patients in this study, might have benefited from a more established technique, such as monopolar RF neurotomy of cervical and lumbar medial branch. We included all patients with facet pain of two regions as this is a common presentation among chronic pain patients in clinical practice. Other relevant information such as changes in post-procedural oral analgesic intake and a more detailed assessment on the long-term outcome and functional status of patients should be included in future studies. Even though this is a retrospective study, the importance of reporting such series in the pain medicine literature cannot be overlooked, as it is the only one reporting bipolar RF denervation of thoracic facet joint.

In conclusion, this case series suggests that bipolar RF neurotomy of thoracic medial branch is associated with a significant reduction in thoracic facet joint pain probably due to its ability to create a larger lesion to overcome the inconsistency of the neural path of thoracic medial branch. The promising findings from this case series merit further assessment with prospective, randomized controlled trial which will produce a more reliable and accurate finding for its clinical applications.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Goh Kiang Hua, MBBS, FRCS and Dr. Nicole Van den Hecke, MD, for critical review and editing support of this manuscript.

-

Authors’ statements

-

Research funding: This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in public, commercial or not- for- profit sectors.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable as this is a retrospective study, all data was de-identified and analyzed anonymously.

-

Ethical approval: This study was approved by institutional research review board with trial number 13-N-130 and was registered to the national trial registry with identifier number NTR 4294.

-

Authors’ contributions

-

RO was responsible for the development of study protocol and the design of the study. RO also involved in data collection and contributed to the manuscript writing. CKC performed the data analysis, contributed to the development of study protocol, the study design and manuscript writing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

[1] Leboeuf-Yde C, Nielsen J, Kyvik KO, Fejer R, Hartvigsen J. Pain in the lumbar, thoracic or cervical regions: do age and gender matter? A population-based study of 34,902 Danish twins 20–71 years of age. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2009;10:39.10.1186/1471-2474-10-39Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[2] Manchikanti L, Boswell MV, Singh V, Pampati V, Damron KS, Beyer CD. Prevalence of facet joint pain in chronic spinal pain of cervical, thoracic, and lumbar regions. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2004;5:15.10.1186/1471-2474-5-15Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[3] van Kleef M, Stolker RJ, Lataster A, Geurts J, Benzon HT, Mekhail N. Thoracic pain. Pain Pract 2010;10:327–38.10.1111/j.1533-2500.2010.00376.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[4] Dreyfuss P, Tibiletti C, Dreyer SJ. Thoracic zygapophyseal joint pain patterns. A study in normal volunteers. Spine 1994;19:807–11.10.1097/00007632-199404000-00014Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[5] Fukui S, Ohseto K, Shiotani M. Patterns of pain induced by distending the thoracic zygapophy seal joints. Reg Anesth 1997;22:332–6.10.1016/S1098-7339(97)80007-7Search in Google Scholar

[6] Boswell MV, Colson JD, Sehgal N, Dunbar EE, Epter R. A systematic review of therapeutic facet joint interventions in chronic spinal pain. Pain Physician 2007;10:229–53.Search in Google Scholar

[7] Van Zundert J, Vanelderen P, Kessels A, Van Kleef M. Radiofrequency treatment of facet-related pain: evidence and controversies. Curr Pain Headache Rep 2012;16:19–25.10.1007/s11916-011-0237-8Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[8] Manchikanti KN, Atluri S, Singh V, Geffert S, Sehgal N, Falco FJ. An update of evaluation of therapeutic thoracic facet joint interventions. Pain Physician 2012;15:E463–81.10.36076/ppj.2012/15/E463Search in Google Scholar

[9] Cosman ER Jr, Gonzalez CD. Bipolar 120 radiofrequency lesion geometry: implications for palisade treatment of sacroiliac joint pain. Pain Pract 2011;11:3–22.10.1111/j.1533-2500.2010.00400.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[10] Bruners P, Lipka J, Günther RW, Schmitz-Rode T, Mahnken AH. Bipolar radiofrequency ablation: is the shape of the coagulation volume different in comparison to monopolar RF ablation using variable active tip lengths? Minim Invasive Ther Allied Technol 2008;17:267–74.10.1080/13645700802384122Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] Ferrante FM, King LF, Roche EA, Kim PS, Aranda M, DeLaney LR, Mardini IA, Mannes AJ. Radiofrequency sacroiliac joint denervation for sacroiliac syndrome. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2001;26:137–42.10.1097/00115550-200103000-00008Search in Google Scholar

[12] Pino CA, Hoeft MA, Hofsess C, Rathmell JP. Morphologic analysis of bipolar radiofrequency lesions: implications for treatment of the sacroiliac joint. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2005;30:335–8.10.1016/j.rapm.2005.03.014Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[13] Kapural L, Vrooman B, Sarwar S, Krizanac-Bengez L, Rauck R, Gilmore C, North J, Girgis G, Mekhail N. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of transdiscal radiofrequency, biacuplasty for treatment of discogenic lower back pain. Pain Med 2013;14:362–73.10.1111/pme.12023Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[14] Zeng ZH, Yan M, Dai Y, Qiu WD, Deng S, Gu XZ. Percutaneous bipolar radiofrequency thermocoagulation for the treatment of lumbar disc herniation. J Clin Neurosci 2016;30:39–43.10.1016/j.jocn.2015.10.050Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[15] Kang SS, Shin KM, Jung SM, Park JH, Hong SJ. Sequential bipolar radiofrequency lumbar sympathectomy in Raynaud’s disease: a case report. Korean J Anesthesiol 2010;59:286–9.10.4097/kjae.2010.59.4.286Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[16] Destegul D, Isik G, Özbek H, Ünlugenc H, Ilginel M. Radiofrequency thermocoagulation forthe treatment of lower extremity ischemic pain: comparison of monopolar and bipolar modes. Agri 2017;29:64–70.10.5505/agri.2017.03789Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[17] Bogduk N, editor. Practice Guidelines for Spinal Diagnostic and Treatment Procedures. Chapters Lumbar medial branch blocks and Cervical medial branch blocks, 2nd ed. San Francisco, CA: International Spine Intervention Society, 2013: 137 and 597.Search in Google Scholar

[18] van Eerd M, Patijn J, Lataster A, Rosenquist RW, van Kleef M, Mekhail N, Van Zundert J. Cervical facet pain. Pain Pract 2010;10:113–23.10.1111/j.1533-2500.2009.00346.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[19] Van Kleef M, Vanelderen P, Cohen SP, Lataster A, Van Zundert J, Mekhail N. Pain originating from the lumbar facet joints. Pain Pract 2010;10:459–69.10.1111/j.1533-2500.2010.00393.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[20] Gronblad M, Hupli M, Wennerstrand P, Jarvinen E, Lukinmaa A, Kouri JP, Karaharju EO. Intercorrelation and test-retest reliability of the Pain Disability Index (PDI) and the Oswestry Disability Questionnaire (IDQ) and their correlation with pain intensity in low back pain patients. Clin J Pain 1993;9:189–95.10.1097/00002508-199309000-00006Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[21] Boswell MV, Colson JD, Sehgal N, Dunbar EE, Epter R. A systematic review oftherapeutic facet joint interventions in chronic spinal pain. Pain Physician 2007;10:229–53.10.36076/ppj.2007/10/229Search in Google Scholar

[22] Manchikanti L, Kaye AD, Boswell MV, Bakshi S, Gharibo CG, Gramm V, Grider JS, Gupta S, Jha SS, Mann DP, Nampiaparampil DE, Sharma ML, Shroyer LN, Singh V, Soin A, Vellejo R, Wargo BW, Hirsch JA. A systematic review of efficacy and best evidencesynthesis of therapeutic facet joint interventions in managing chronic spinal pain. Pain Physician 2015; 18:E535–82.10.36076/ppj.2015/18/E535Search in Google Scholar

[23] Manchikanti L, Singh V, Falco FJE, Cash KA, Pampati V, Fellow B. The role of thoracic medial branch blocks in managing chronic mid and upper back pain: a randomized, double-blind, active-control trial with a 2-year followup. Anesthesiol Res Pract 2012;2012:585806.10.1155/2012/585806Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[24] Manchikanti L, Singh V, Falco FJE, Cash KA, Pampati V, Fellows B. Comparative effectiveness of a one-year follow-up of thoracic medial branch blocks in management of chronic thoracic pain: a randomized, double-blind active controlled trial. Pain Physician 2010;13:535–48.10.36076/ppj.2010/13/535Search in Google Scholar

[25] Stolker RJ, Vervest ACM, Groen GJ. Percutaneous facet denervation in chronic thoracic spinal pain. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1993;122:82–90.10.1007/BF01446991Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[26] Tzaan WC, Tasker RR. Percutaneous radiofrequency facet rhozotomy – experience with 118 procedures and reappraisal of its value. Can J Neurol Sci 2000;27:125–30.10.1017/S0317167100052227Search in Google Scholar

[27] Speldewinde GC. Outcomes of percutaneous zygapophysial and sacroiliac joint neurotomy in a community setting. Pain Med 2011;12:209–18.10.1111/j.1526-4637.2010.01022.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[28] Mekhail N, Cheng J. Temperature mapping of cooled radio-frequency lesion of human cadaver thoracic facet medial branches. Clin J Pain 2011;27:56–61.10.1097/AJP.0b013e3181ef4e2dSearch in Google Scholar

[29] Walega D, Roussis C. Third-degree burn from cooled radiofrequency ablation of medial branch nerves for treatment of thoracic facet syndrome. Pain Pract 2014;14:154–8.10.1111/papr.12222Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[30] Chua WH, Bogduk N. The surgical anatomy of thoracic facet denervation. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1995;136:140–4.10.1007/BF01410616Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[31] Panjabi MM, Takata K, Goel V, Federico D, Oxland T, Duranceau J, Krag M. Thoracic humanvertebrae–quantitative three-dimensional anatomy. Spine 1991;16:888–901.10.1097/00007632-199108000-00006Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[32] Tan SH, Teo EC, Chua HC. Quantitative three-dimensional anatomy of cervical, thoracic and lumbar vertebrae of Chinese Singaporens. Eur Spine J 2004;13:134–46.10.1007/s00586-003-0586-zSearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[33] Cosman ER Jr, Dolensky JR, Hoffman RA. Factors that affect radiofrequency heat lesion size. Pain Med 2014;15:2020–36.10.1111/pme.12566Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[34] Chou R, Atlas SJ, Stanos SP, Rosenquist RW. Nonsurgical interventional therapies for low back pain. Spine 2009;34:1078–93.10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181a103b1Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[35] Soloman M, Mekhail MN, Mekhail N. Radiofrequency treatment in chronic pain. Expert Rev Neurother 2010;10:469–74.10.1586/ern.09.153Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[36] Roca G, de Andres Ares J, Gay M, Nieto C, Bovaira MT. Radiofrequency complications and troubleshooting. Tech Reg Anesth Pain Manag 2014;18:25–34.10.1053/j.trap.2015.01.005Search in Google Scholar

[37] Kim D. Bipolar intra-articular radiofrequency thermocoagulation of the thoracic facet joints: a case series of a new technique. Korean J Pain 2014;27:43–8.10.3344/kjp.2014.27.1.43Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[38] Boyle JJ, Singer KP, Milne N. Morphological survey of the cervicothoracic junctional region. Spine 1996;21:544–8.10.1097/00007632-199603010-00003Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[39] An H, Wise J, Xu R. Anatomy of the cervicothoracic junction: a study of cadaveric dissection, cryomicrotomy and magnetic resonance imaging. J Spinal Dis 1999;12:519–25.10.1097/00002517-199912000-00012Search in Google Scholar

©2018 Scandinavian Association for the Study of Pain. Published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston. All rights reserved.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial comment

- Support for mirror therapy for phantom and stump pain in landmine-injured patients

- Lifting with straight legs and bent spine is not bad for your back

- Bipolar radiofrequency neurotomy for spinal pain – a promising technique but still some steps to go

- Topical review

- Prevalence, localization, perception and management of pain in dance: an overview

- Clinical pain research

- Pain assessment in native and non-native language: difficulties in reporting the affective dimensions of pain

- Colored body images reveal the perceived intensity and distribution of pain in women with breast cancer treated with adjuvant taxanes: a prospective multi-method study of pain experiences

- Physiotherapy pain curricula in Finland: a faculty survey

- Mirror therapy for phantom limb and stump pain: a randomized controlled clinical trial in landmine amputees in Cambodia

- Pain and alcohol: a comparison of two cohorts of 60 year old women and men: findings from the Good Aging in Skåne study

- Prolonged, widespread, disabling musculoskeletal pain of adolescents among referrals to the Pediatric Rheumatology Outpatient Clinic from the Päijät-Häme Hospital District in southern Finland

- Impact of the economic crisis on pain research: a bibliometric analysis of pain research publications from Ireland, Greece, and Portugal between 1997 and 2017

- Measurement of skin conductance responses to evaluate procedural pain in the perioperative setting

- Original experimental

- An observational study of pain self-management strategies and outcomes: does type of pain, age, or gender, matter?

- Fibromyalgia patients and healthy volunteers express difficulties and variability in rating experimental pain: a qualitative study

- Effect of the market withdrawal of dextropropoxyphene on use of other prescribed analgesics

- Observational study

- Winning or not losing? The impact of non-pain goal focus on attentional bias to learned pain signals

- Gabapentin and NMDA receptor antagonists interacts synergistically to alleviate allodynia in two rat models of neuropathic pain

- Offset analgesia is not affected by cold pressor induced analgesia

- Central and peripheral pain sensitization during an ultra-marathon competition

- Reduced endogenous pain inhibition in adolescent girls with chronic pain

- Evaluation of implicit associations between back posture and safety of bending and lifting in people without pain

- Assessment of CPM reliability: quantification of the within-subject reliability of 10 different protocols

- Cerebrospinal fluid cutaneous fistula after neuraxial anesthesia: an effective treatment approach

- Pain in the hand caused by a previously undescribed mechanism with possible relevance for understanding regional pain

- The response to radiofrequency neurotomy of medial branches including a bipolar system for thoracic facet joints

- Letter to the Editor

- Diagnosis of carpal tunnel syndrome – implications for therapy

- Reply to the Letter to the Editor by Ly-Pen and Andréu

- Letter to the Editor regarding “CT guided neurolytic blockade of the coeliac plexus in patients with advanced and intractably painful pancreatic cancer”

- Reply to comments from Ulf Kongsgaard to our study

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial comment

- Support for mirror therapy for phantom and stump pain in landmine-injured patients

- Lifting with straight legs and bent spine is not bad for your back

- Bipolar radiofrequency neurotomy for spinal pain – a promising technique but still some steps to go

- Topical review

- Prevalence, localization, perception and management of pain in dance: an overview

- Clinical pain research

- Pain assessment in native and non-native language: difficulties in reporting the affective dimensions of pain

- Colored body images reveal the perceived intensity and distribution of pain in women with breast cancer treated with adjuvant taxanes: a prospective multi-method study of pain experiences

- Physiotherapy pain curricula in Finland: a faculty survey

- Mirror therapy for phantom limb and stump pain: a randomized controlled clinical trial in landmine amputees in Cambodia

- Pain and alcohol: a comparison of two cohorts of 60 year old women and men: findings from the Good Aging in Skåne study

- Prolonged, widespread, disabling musculoskeletal pain of adolescents among referrals to the Pediatric Rheumatology Outpatient Clinic from the Päijät-Häme Hospital District in southern Finland

- Impact of the economic crisis on pain research: a bibliometric analysis of pain research publications from Ireland, Greece, and Portugal between 1997 and 2017

- Measurement of skin conductance responses to evaluate procedural pain in the perioperative setting

- Original experimental

- An observational study of pain self-management strategies and outcomes: does type of pain, age, or gender, matter?

- Fibromyalgia patients and healthy volunteers express difficulties and variability in rating experimental pain: a qualitative study

- Effect of the market withdrawal of dextropropoxyphene on use of other prescribed analgesics

- Observational study

- Winning or not losing? The impact of non-pain goal focus on attentional bias to learned pain signals

- Gabapentin and NMDA receptor antagonists interacts synergistically to alleviate allodynia in two rat models of neuropathic pain

- Offset analgesia is not affected by cold pressor induced analgesia

- Central and peripheral pain sensitization during an ultra-marathon competition

- Reduced endogenous pain inhibition in adolescent girls with chronic pain

- Evaluation of implicit associations between back posture and safety of bending and lifting in people without pain

- Assessment of CPM reliability: quantification of the within-subject reliability of 10 different protocols

- Cerebrospinal fluid cutaneous fistula after neuraxial anesthesia: an effective treatment approach

- Pain in the hand caused by a previously undescribed mechanism with possible relevance for understanding regional pain

- The response to radiofrequency neurotomy of medial branches including a bipolar system for thoracic facet joints

- Letter to the Editor

- Diagnosis of carpal tunnel syndrome – implications for therapy

- Reply to the Letter to the Editor by Ly-Pen and Andréu

- Letter to the Editor regarding “CT guided neurolytic blockade of the coeliac plexus in patients with advanced and intractably painful pancreatic cancer”

- Reply to comments from Ulf Kongsgaard to our study